TL;DR#

Object detection heavily relies on Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) for efficient post-processing. However, traditional NMS methods are computationally expensive, becoming a bottleneck in modern high-speed object detection models. This research addresses this issue by presenting a novel approach to NMS using graph theory, which provides insights into its structural properties.

The proposed algorithms, QSI-NMS and BOE-NMS, leverage the graph-theoretic perspective. QSI-NMS is a fast recursive divide-and-conquer algorithm, while BOE-NMS focuses on the locality of suppression. These algorithms are significantly faster than traditional methods, providing speedups of up to 10.7x with only a marginal decrease in accuracy. To facilitate evaluation, the researchers also introduce NMS-Bench, a benchmark for comprehensive assessment of NMS methods. This contribution promises to accelerate research and development in object detection.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in object detection because it addresses the computational bottleneck of Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS), a critical post-processing step. By offering novel graph theory-based optimization algorithms (QSI-NMS and BOE-NMS) and introducing a benchmark (NMS-Bench), it facilitates faster and more efficient NMS, enabling real-time object detection and paving the way for advancements in various computer vision applications. It also provides valuable insights into the intrinsic structure of NMS, opening new avenues for algorithm optimization and research.

Visual Insights#

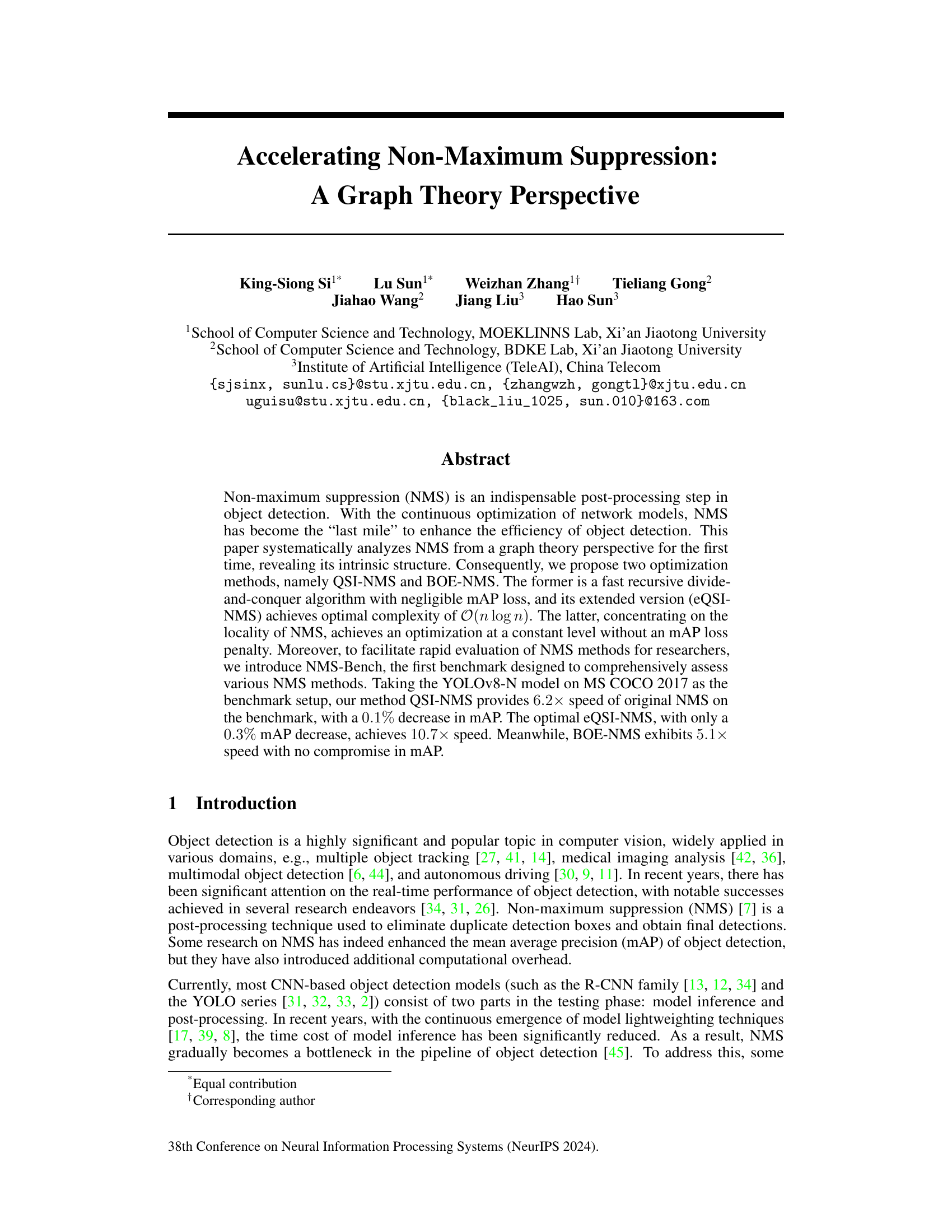

🔼 This figure illustrates the dynamic programming approach to topological sorting in the context of non-maximum suppression (NMS). Nodes represent bounding boxes, and edges represent suppression relationships. The color of each node indicates whether the box is retained (black = 1, white = 0). The process demonstrates how topological sorting enables efficient computation of NMS using dynamic programming by iteratively removing suppressed boxes and their associated edges, ultimately arriving at the final set of retained boxes (nodes 1, 6, and 8).

read the caption

Figure 1: Dynamic programming in topological sorting. The color of the node represents the δ value, i.e., black represents 1, and white represents 0. Before suppression, each node is black. In topological sorting, traversed arcs are represented by dashed lines, showing they have been removed from the graph. After the topological sorting is completed, we can find that nodes 1, 6, and 8 are all black, that is, the last boxes retained are b₁, b6, and b8.

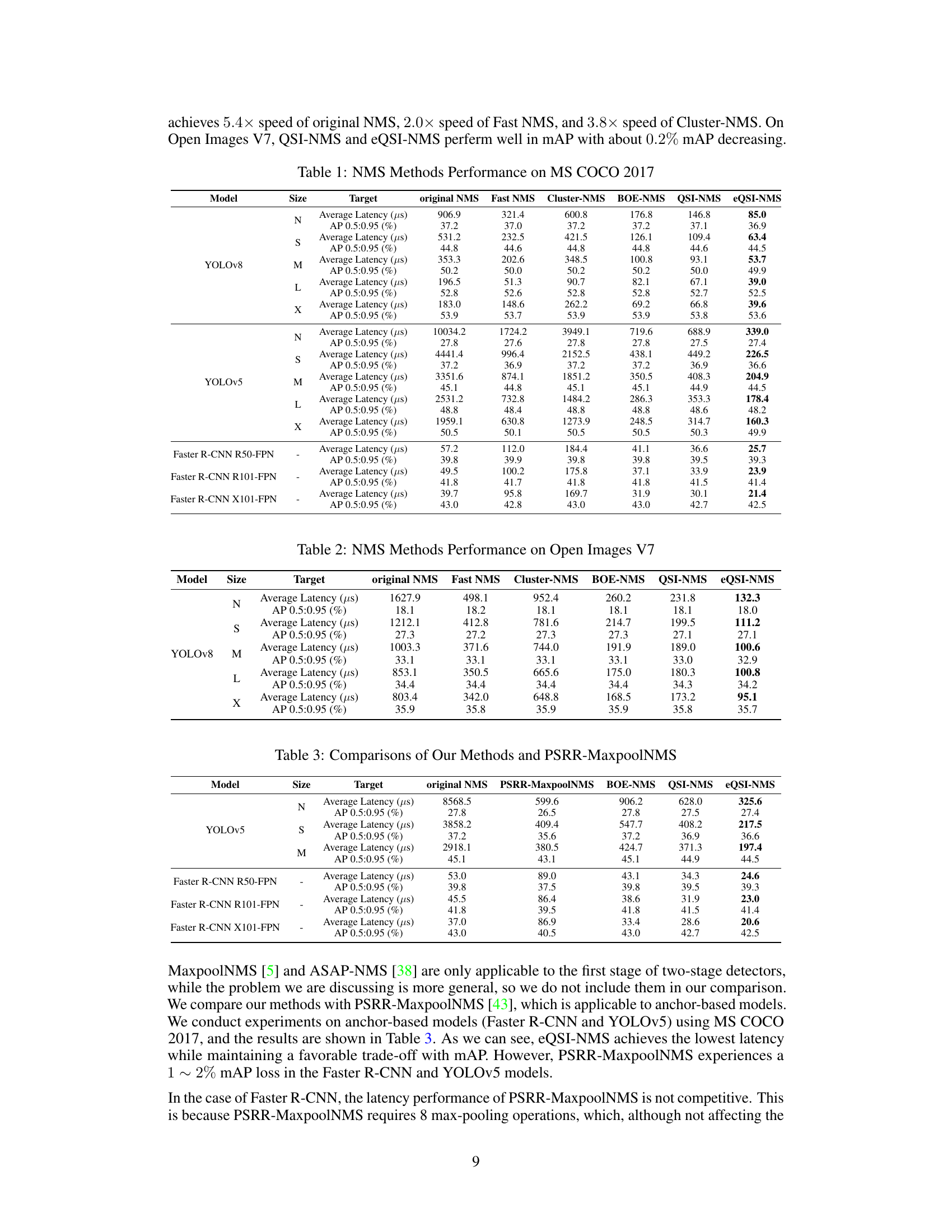

🔼 This table presents a comparison of various Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) methods’ performance on the MS COCO 2017 dataset. For several YOLOv8 and YOLOv5 model sizes (N, S, M, L, X), the table shows the average latency (in microseconds) and Average Precision (AP) at 0.5:0.95 IoU thresholds for each method (original NMS, Fast NMS, Cluster-NMS, BOE-NMS, QSI-NMS, eQSI-NMS). The results illustrate the speed and accuracy trade-offs of different NMS algorithms.

read the caption

Table 1: NMS Methods Performance on MS COCO 2017

In-depth insights#

NMS: Graph Theory#

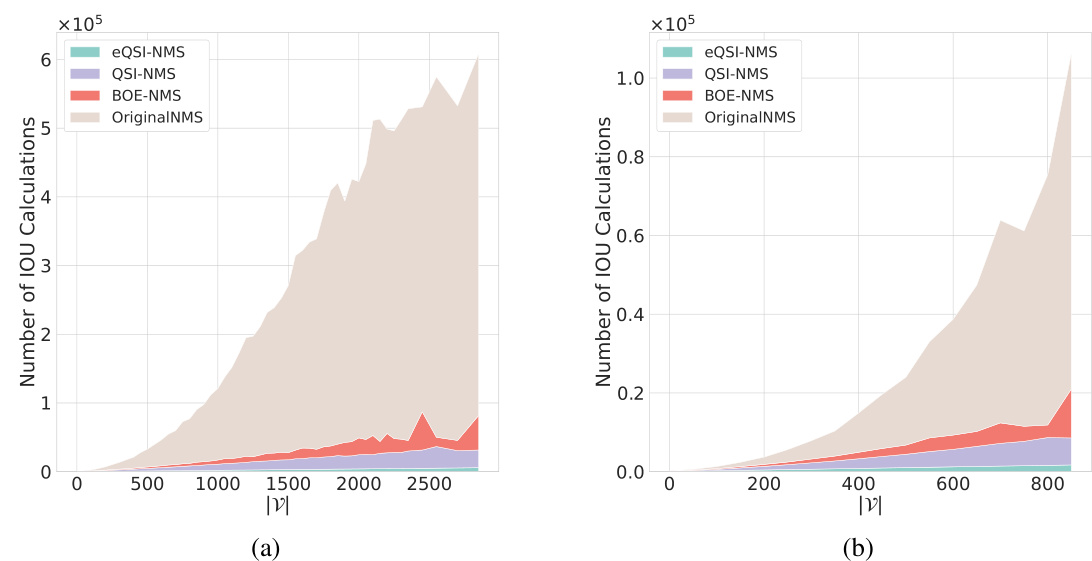

A graph theory perspective on Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) offers a novel approach to analyze and optimize this crucial step in object detection. By representing bounding boxes as nodes and suppression relationships as edges, NMS is framed as a directed acyclic graph (DAG). This representation allows for the application of graph algorithms, leading to efficient solutions. Dynamic programming on this DAG becomes a powerful tool for finding optimal suppression strategies. The inherent structure of the graph, particularly the presence of numerous weakly connected components (WCCs), most of which are small, reveals key insights for algorithmic optimization. This discovery paves the way for divide-and-conquer algorithms, like quicksort-induced NMS (QSI-NMS), with a time complexity of O(n log n) or even linear time in practice, that reduce the computational burden significantly. Furthermore, the local suppression nature of NMS is exploited using the concept of geometric locality, resulting in alternative optimized algorithms that avoid unnecessary computations. This graph theory perspective provides a unified framework for understanding and improving NMS, leading to faster and more efficient object detection systems.

QSI-NMS Algorithm#

The QSI-NMS (Quicksort-Induced Non-Maximum Suppression) algorithm presents a novel approach to optimizing NMS by integrating graph theory and a divide-and-conquer strategy. It leverages the inherent DAG structure of NMS, representing suppression relationships as a directed acyclic graph. By identifying weakly connected components (WCCs) within this graph, QSI-NMS recursively divides the problem into smaller, independent subproblems. This divide-and-conquer approach significantly speeds up processing compared to traditional methods. Inspired by the quicksort algorithm, QSI-NMS efficiently selects pivots and partitions the data for optimal recursive processing. A key advantage is its relatively low mAP (mean Average Precision) loss, ensuring that speed improvements come at a minimal cost to accuracy. The algorithm demonstrates a significant speedup while maintaining high accuracy, making it a promising solution for real-time object detection applications where speed and accuracy are both critical.

BOE-NMS Approach#

The BOE-NMS (Boxes Outside Excluded NMS) approach leverages the sparsity of the graph representing NMS relationships. It recognizes that many weakly connected components in this graph are small, indicating localized suppression. BOE-NMS exploits this locality by only calculating IOUs for boxes spatially close to the currently considered box, significantly reducing computations. This geometric analysis avoids unnecessary IOU calculations for distant boxes that are unlikely to influence suppression decisions. This locality-based strategy maintains mAP performance while dramatically improving speed by reducing the computational burden of evaluating many low-IOU relationships. The core idea is to efficiently identify nearby bounding boxes and avoid the unnecessary computations, leading to a fast and accurate NMS algorithm without sacrificing detection accuracy. The geometric filtering step is computationally efficient, and its efficacy stems from the inherent clustering of object detections. This makes BOE-NMS a valuable alternative for real-time object detection systems where speed is crucial.

NMS-Bench Metrics#

A hypothetical section, ‘NMS-Bench Metrics,’ would require careful consideration of evaluation criteria for non-maximum suppression (NMS) algorithms. Benchmarking NMS necessitates a holistic approach, moving beyond simple speed measurements. Essential metrics would include mean Average Precision (mAP), a widely-accepted measure of object detection accuracy, enabling comparison of speed improvements against potential precision losses. Computational cost, measured as runtime or number of operations, should be included to quantify algorithm efficiency. Memory usage is another crucial factor, particularly relevant for resource-constrained applications. The benchmark should also incorporate metrics reflecting the impact of different NMS methods on various object detection model architectures and dataset characteristics. Ideally, visualizations would accompany numerical results to provide intuitive understanding of performance trade-offs. Furthermore, statistical significance tests would be essential to ensure that observed differences in performance are meaningful and not due to random variations. Finally, the benchmark should be easily reproducible, using clearly documented methodology and readily accessible datasets, fostering transparent and reliable comparisons.

Future Enhancements#

Future enhancements for accelerating Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) could explore several avenues. Improving the efficiency of graph construction is crucial; current methods rely on IOU calculations, a computational bottleneck. Exploring alternative graph representations or approximation techniques, perhaps leveraging spatial relationships or confidence scores more directly, could significantly reduce overhead. Developing more sophisticated partitioning strategies for divide-and-conquer algorithms like QSI-NMS is another promising area. This might involve incorporating additional features beyond confidence scores and geometric information into the partitioning process, possibly using machine learning to learn optimal partitioning schemes. Further research into the inherent structure of the NMS graph is needed; a deeper understanding could reveal additional opportunities for optimization. Finally, combining the strengths of different NMS methods, such as integrating the locality awareness of BOE-NMS with the global optimization capabilities of QSI-NMS, could lead to hybrid approaches with superior performance.

More visual insights#

More on figures

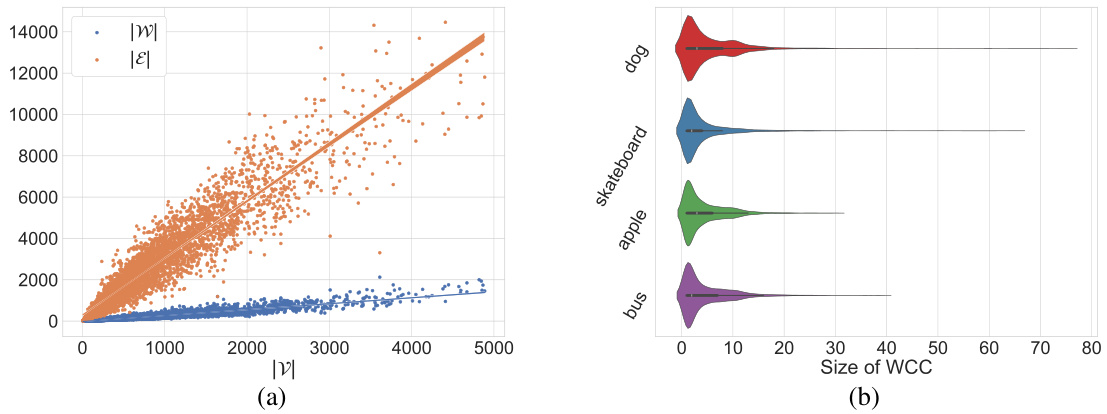

🔼 This figure statistically analyzes the graph G derived from the non-maximum suppression (NMS) algorithm on the MS COCO 2017 validation set. Subfigure (a) shows a scatter plot demonstrating a near-linear relationship between the number of nodes (|V|), the number of edges (|E|), and the number of weakly connected components (WCCs) in the graph G. Subfigure (b) provides violin plots illustrating the distribution of WCC sizes for different object categories in the dataset. The plots reveal that a significant majority of WCCs are small, with more than half having a size under 5 and over three-quarters having a size under 10. This observation supports the use of divide-and-conquer strategies and locality-based optimizations in the proposed NMS algorithms (QSI-NMS and BOE-NMS).

read the caption

Figure 2: Statistical characteristics of graph G on MS COCO 2017 validation. 2(a) The scatter plot of 5000 Gs on MS COCO 2017. It indicates that the number of arcs |E| and the number of WCCs W exhibit an approximately linear relationship with the number of nodes |V|, respectively. 2(b) The violin plot of the sizes of WCCs across different categories on MS COCO 2017. It reveals the distributional characteristics of the sizes of the WCCs. It shows that over 50% of the WCCs have a size less than 5, and more than 75% have a size less than 10.

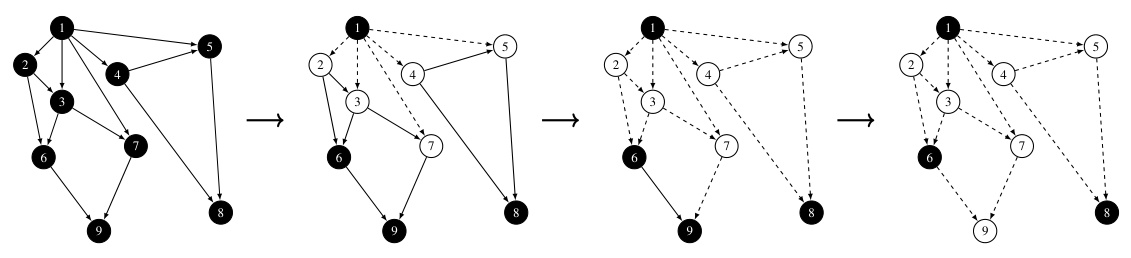

🔼 This figure illustrates the core concepts behind the two proposed optimization methods, QSI-NMS and BOE-NMS, by visualizing their operation on a graph representation of the NMS problem. The left side shows QSI-NMS using a divide-and-conquer approach, recursively partitioning the graph into smaller subproblems based on the selection of pivots. The right side illustrates BOE-NMS, which focuses on the local structure of the graph, using geometric analysis to identify and process only nearby nodes, reducing computational cost.

read the caption

Figure 3: The key ideas behind QSI-NMS (left) and BOE-NMS (right). G (middle) contains many small weakly connected components (WCCs). QSI-NMS considers the global structure of the graph G, where there are many WCCs. It selects a pivot (the red node on the left) and computes IOUs (orange edges) with all current subproblem nodes using a divide-and-conquer algorithm. BOE-NMS focuses on the local structure (the red dashed box) of G, where most WCCs are quite small in size. It selects a node (the red node on the right) and only computes IOUs (orange edges) with its nearby nodes (solid arrows), which is derived from 2D plane geometric analysis (dashed arrows).

🔼 This figure illustrates the dynamic programming approach used in topological sorting for non-maximum suppression (NMS). Each node represents a bounding box, and the color indicates whether it is retained (black) or suppressed (white). Arcs represent suppression relationships. The process starts with all nodes black, and iteratively removes nodes based on topological order until the final set of retained nodes is determined.

read the caption

Figure 1: Dynamic programming in topological sorting. The color of the node represents the δ value, i.e., black represents 1, and white represents 0. Before suppression, each node is black. In topological sorting, traversed arcs are represented by dashed lines, showing they have been removed from the graph. After the topological sorting is completed, we can find that nodes 1, 6, and 8 are all black, that is, the last boxes retained are b₁, b₆, and b₈.

🔼 This figure shows four possible relative positions of two bounding boxes, b and b*, with respect to each other. The boxes are positioned relative to horizontal and vertical dashed lines passing through the centroid of box b. The area of intersection between the boxes is highlighted in red.

read the caption

Figure 5: Four positions of b* relative to b.

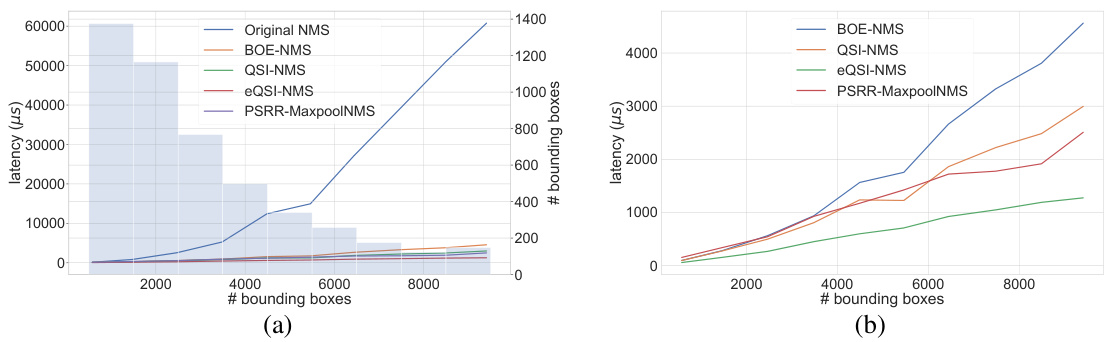

🔼 This figure shows the runtime performance of different NMS algorithms (Original NMS, BOE-NMS, QSI-NMS, eQSI-NMS, and PSRR-MaxpoolNMS) as a function of the number of bounding boxes. The left subplot (a) displays a histogram of bounding box counts and a line plot of all algorithms’ latency showing the quadratic nature of Original NMS. The right subplot (b) presents a detailed line graph comparing the latency of the other four algorithms, highlighting the efficiency of eQSI-NMS.

read the caption

Figure 6: The line plot of the runtime of different methods as the number of bounding boxes varies in YOLOv5-N. 6(a) The histogram with a bin width of 1000 representing the number of bounding boxes in each interval. The input images are divided into 10 intervals based on the number of bounding boxes: (0, 1000], (1000, 2000], ..., (9000, 10000]. The line plot is drawn with the average number of boxes per interval as the x-coordinate and the average time cost of the NMS algorithms as the y-coordinate. 6(b) The line plot of the runtime of different methods without original NMS.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of the bounding boxes detected by original NMS and QSI-NMS methods on a specific image from the MS COCO 2017 dataset. The blue boxes represent bounding boxes detected by the original NMS (or equivalently BOE-NMS), while red boxes in (b) highlight the extra bounding boxes retained by QSI-NMS, indicating some cases where QSI-NMS’s divide-and-conquer strategy may result in more boxes being kept compared to the original method.

read the caption

Figure 7: The output bounding boxes of original NMS (7(a)) and QSI-NMS (7(b)) in YOLOv8-M on the MS COCO 2017 image “000000057027.jpg”.

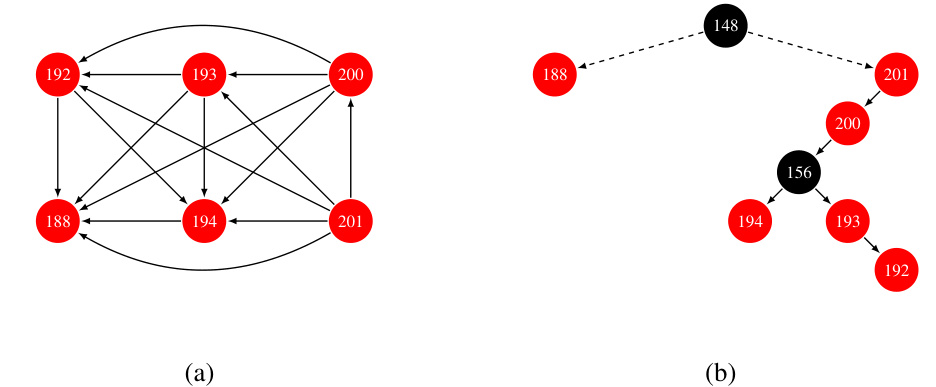

🔼 This figure shows a weakly connected component (WCC) from graph G, which is induced by the Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) algorithm. Subfigure (a) displays the WCC as a graph, where nodes represent bounding boxes and edges represent suppression relationships. Subfigure (b) shows a partial QSI-tree, illustrating how this WCC is recursively partitioned during the QSI-NMS algorithm. Nodes are colored red if they are part of the original WCC, and black otherwise.

read the caption

Figure 8: WCC in graph G contains node 188 (8(a)), along with a partial structure of the QSI-tree (8(b)).

🔼 This figure shows the statistical characteristics of the graph G generated from the bounding boxes of the MS COCO 2017 dataset. The left subplot (a) is a scatter plot illustrating the relationship between the number of nodes (|V|), the number of edges (|E|), and the number of weakly connected components (WCCs) in graph G. It shows that the number of edges and WCCs grow approximately linearly with the number of nodes. The right subplot (b) is a violin plot demonstrating the distribution of the sizes of the WCCs across different object categories in the dataset. The plot highlights that a significant majority (over 75%) of WCCs are small, consisting of fewer than 10 nodes.

read the caption

Figure 2: Statistical characteristics of graph G on MS COCO 2017 validation. 2(a) The scatter plot of 5000 Gs on MS COCO 2017. It indicates that the number of arcs |E| and the number of WCCs W exhibit an approximately linear relationship with the number of nodes |V|, respectively. 2(b) The violin plot of the sizes of WCCs across different categories on MS COCO 2017. It reveals the distributional characteristics of the sizes of the WCCs. It shows that over 50% of the WCCs have a size less than 5, and more than 75% have a size less than 10.

🔼 This figure illustrates the key ideas behind the two proposed optimization methods: QSI-NMS and BOE-NMS. It uses a graph representation of the non-maximum suppression (NMS) problem, where nodes are bounding boxes and edges represent suppression relationships. QSI-NMS uses a global divide-and-conquer approach, recursively partitioning the graph into smaller subproblems. BOE-NMS focuses on local suppression relationships, only considering nearby boxes. The figure highlights the difference in the algorithms’ approach to efficiently solve the NMS problem.

read the caption

Figure 3: The key ideas behind QSI-NMS (left) and BOE-NMS (right). G (middle) contains many small weakly connected components (WCCs). QSI-NMS considers the global structure of the graph G, where there are many WCCs. It selects a pivot (the red node on the left) and computes IOUs (orange edges) with all current subproblem nodes using a divide-and-conquer algorithm. BOE-NMS focuses on the local structure (the red dashed box) of G, where most WCCs are quite small in size. It selects a node (the red node on the right) and only computes IOUs (orange edges) with its nearby nodes (solid arrows), which is derived from 2D plane geometric analysis (dashed arrows).

More on tables

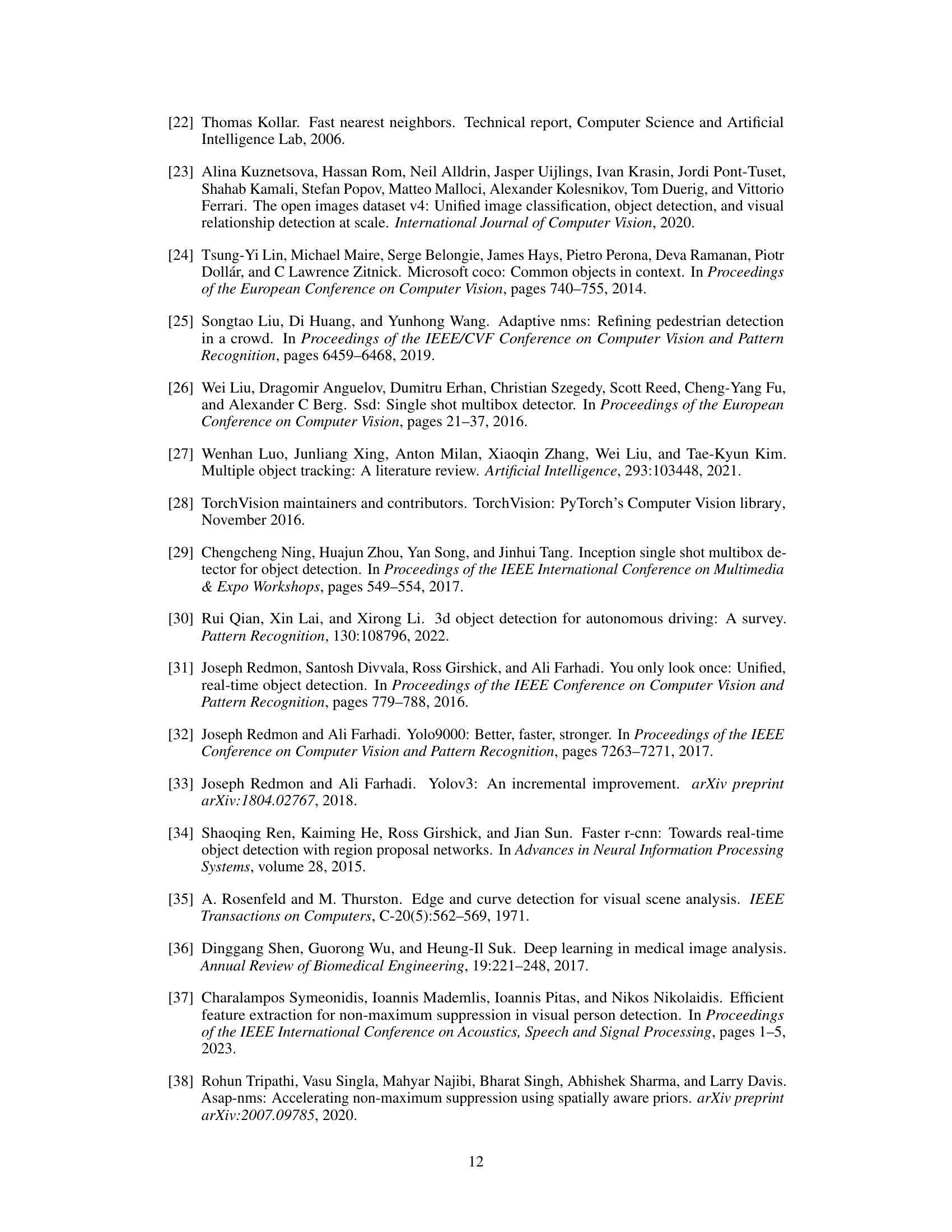

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) methods on the Open Images V7 dataset. It shows the average latency (in microseconds) and Average Precision (AP) at IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 for different model sizes (N, S, M, L, X) of the YOLOv8 object detection model. The methods compared include the original NMS, Fast NMS, Cluster-NMS, BOE-NMS, QSI-NMS, and eQSI-NMS. The table helps illustrate the relative speed and accuracy improvements of the proposed methods (BOE-NMS, QSI-NMS, and eQSI-NMS) over existing techniques.

read the caption

Table 2: NMS Methods Performance on Open Images V7

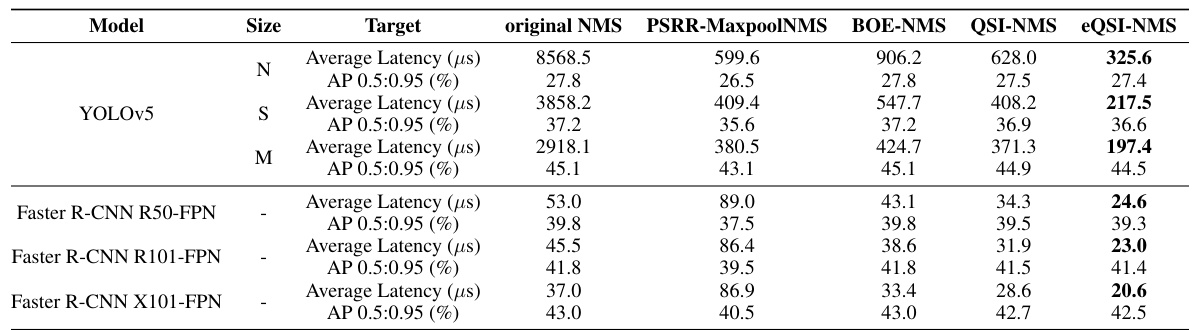

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed methods (BOE-NMS, QSI-NMS, and eQSI-NMS) against the original NMS and PSRR-MaxpoolNMS on various models (YOLOv5 and Faster R-CNN with different backbones) and sizes. The metrics compared are average latency (in microseconds) and Average Precision (AP) at IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95. This allows for a direct comparison of speed and accuracy across different object detection architectures.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparisons of Our Methods and PSRR-MaxpoolNMS

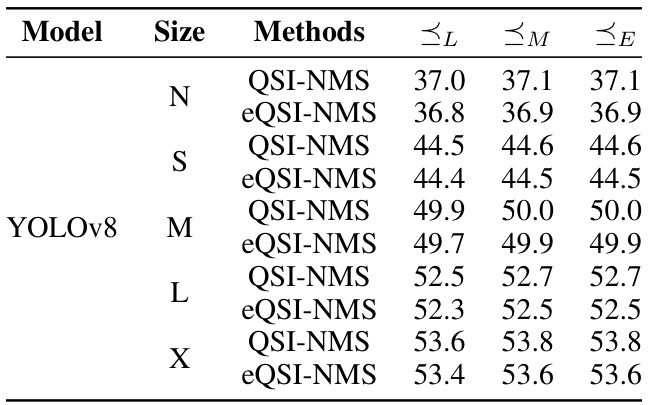

🔼 This table presents the mean Average Precision (AP) at IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 for different model sizes (N, S, M, L, X) of the YOLOv8 object detection model. The results are shown for QSI-NMS and eQSI-NMS algorithms, with variations in the order used to process bounding boxes (L, M, E). The different orders represent different approaches to prioritizing the order of bounding box suppression and show the impact on performance.

read the caption

Table 4: AP0.5:0.95 (%) of QSI-NMS and eQSI-NMS under Different Orders on MS COCO 2017

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of various Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) methods on the MS COCO 2017 dataset. It shows the average latency (in microseconds) and Average Precision (AP) at 0.5:0.95 Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds for different model sizes (N, S, M, L, X) of the YOLOv8 and YOLOv5 models, along with Faster R-CNN models. The methods compared include the original NMS, Fast NMS, Cluster-NMS, BOE-NMS, QSI-NMS, and eQSI-NMS.

read the caption

Table 1: NMS Methods Performance on MS COCO 2017

🔼 This table presents the number of bounding boxes produced by different sizes of YOLOv8 models after inference on the Open Images V7 dataset. A higher number of bounding boxes generally indicates that the model’s filtering capabilities are weaker, resulting in more post-processing work for NMS and thus longer processing times.

read the caption

Table 6: Number of Bounding Boxes on Open Images V7

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different NMS methods (original NMS, Fast NMS, Cluster-NMS, BOE-NMS, QSI-NMS, and eQSI-NMS) on the MS COCO 2017 dataset using different YOLOv8 and YOLOv5 models of various sizes. For each model and size, average latency (in microseconds) and Average Precision (AP) at 0.5:0.95 IoU thresholds are shown, demonstrating the speed and accuracy trade-offs of each method. The results highlight the significant speed improvements achieved by BOE-NMS, QSI-NMS, and especially eQSI-NMS, compared to traditional and other optimized NMS techniques.

read the caption

Table 1: NMS Methods Performance on MS COCO 2017

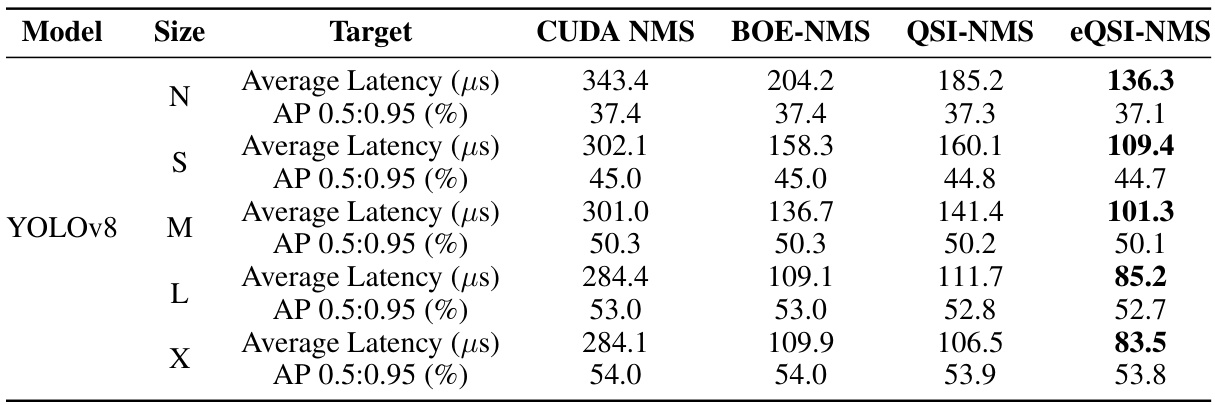

🔼 This table compares the performance of different NMS methods, including CUDA NMS (from the torchvision library), BOE-NMS, QSI-NMS, and eQSI-NMS. The comparison is done using different sizes of YOLOv8 models on the MS COCO 2017 dataset. For each model size, it shows the average latency (in microseconds) and the Average Precision (AP) at IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95.

read the caption

Table 8: NMS Methods Performance under Torchvision Implementation

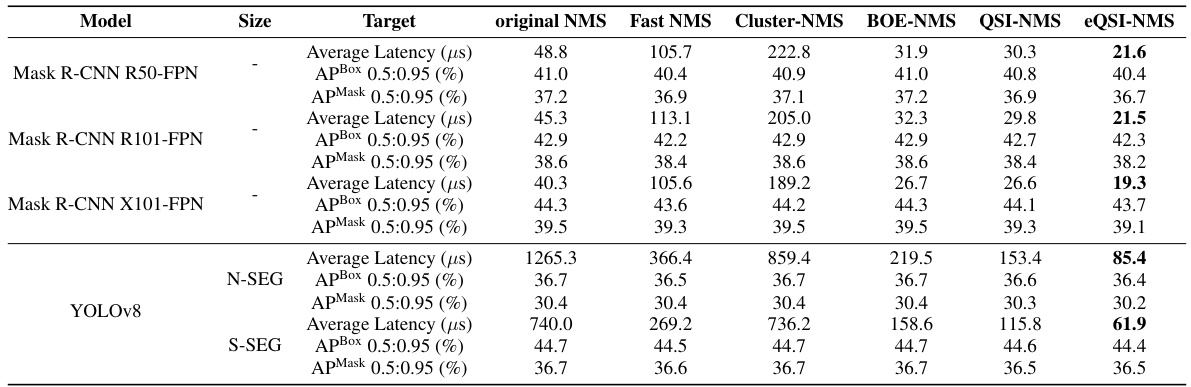

🔼 This table presents the results of applying different NMS methods to instance segmentation tasks using Mask R-CNN and YOLOv8. It compares the average latency (in microseconds) and the average precision (AP) for both bounding boxes (APBox) and masks (APMask) across various model sizes and targets. The purpose is to showcase the performance improvements achieved by the proposed QSI-NMS and eQSI-NMS methods in the context of instance segmentation.

read the caption

Table 9: NMS Methods on Instance Segmentation Tasks

Full paper#