TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) demand vast computational resources and storage. One-shot pruning offers a solution by removing redundant weights without retraining, but current methods often rely on heuristics, leading to suboptimal compression. This creates a bottleneck for efficient LLM deployment and scalability.

This research introduces ALPS, a novel optimization-based framework that addresses these issues. ALPS uses operator splitting and a preconditioned conjugate gradient method for efficient pruning and theoretical convergence guarantees. ALPS outperforms state-of-the-art techniques, achieving significant reductions in test perplexity and improvements in zero-shot benchmarks, particularly in the high-sparsity regime.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents ALPS, a novel optimization-based framework that significantly improves one-shot pruning for large language models. This addresses a critical challenge in deploying LLMs—their massive size—by enabling efficient compression without retraining, leading to faster inference and reduced resource needs. The theoretical guarantees and empirical results presented provide significant advancements in model compression techniques, opening new research directions in efficient LLM deployment and optimization.

Visual Insights#

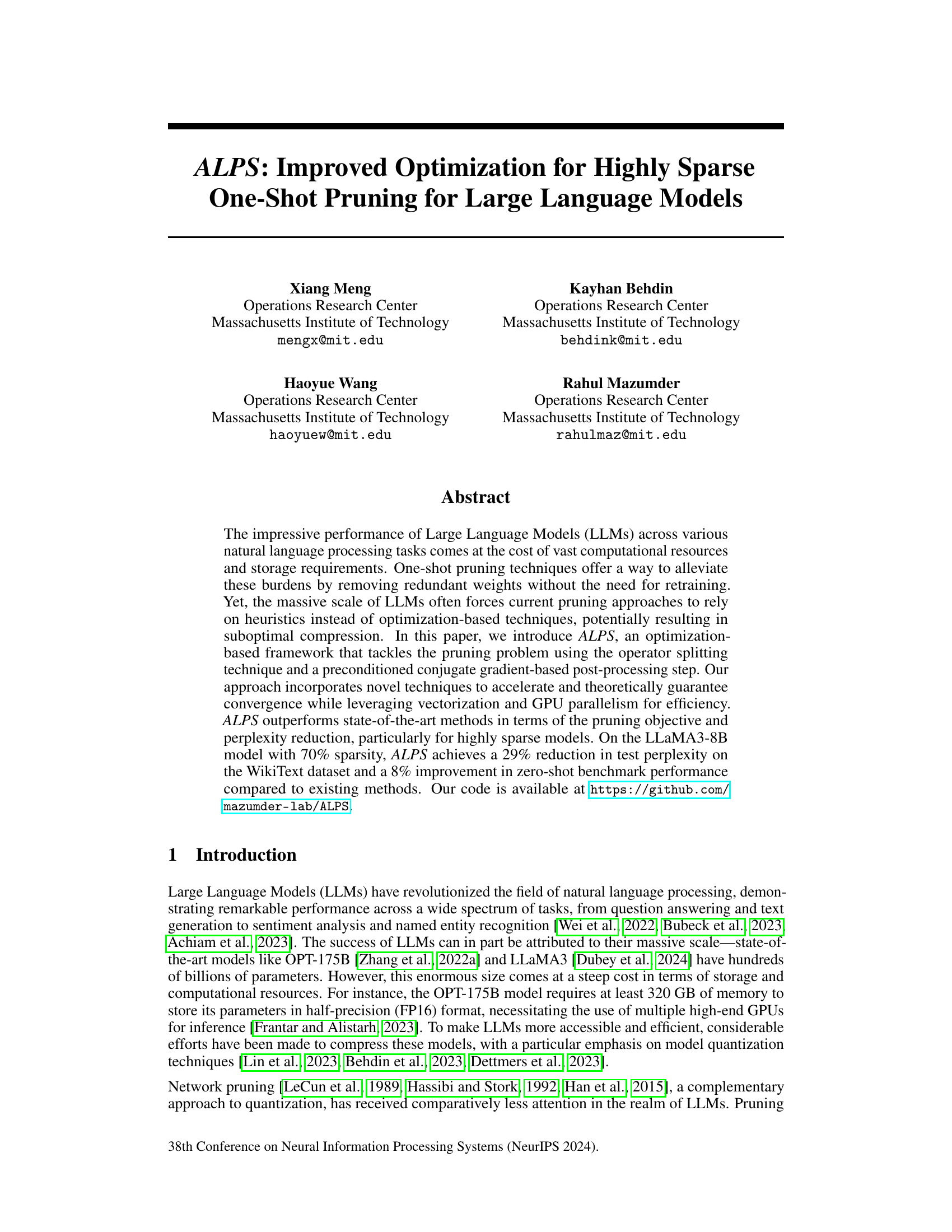

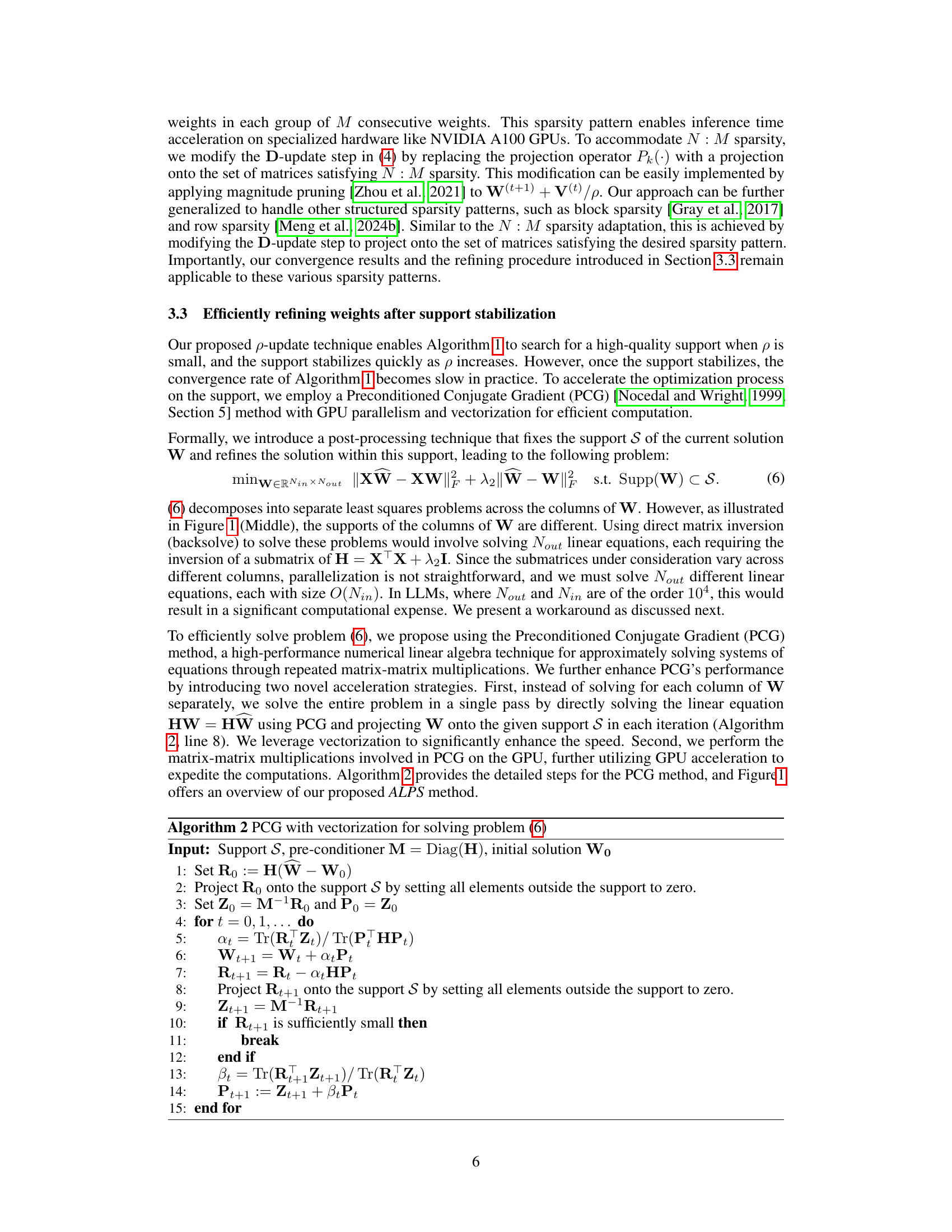

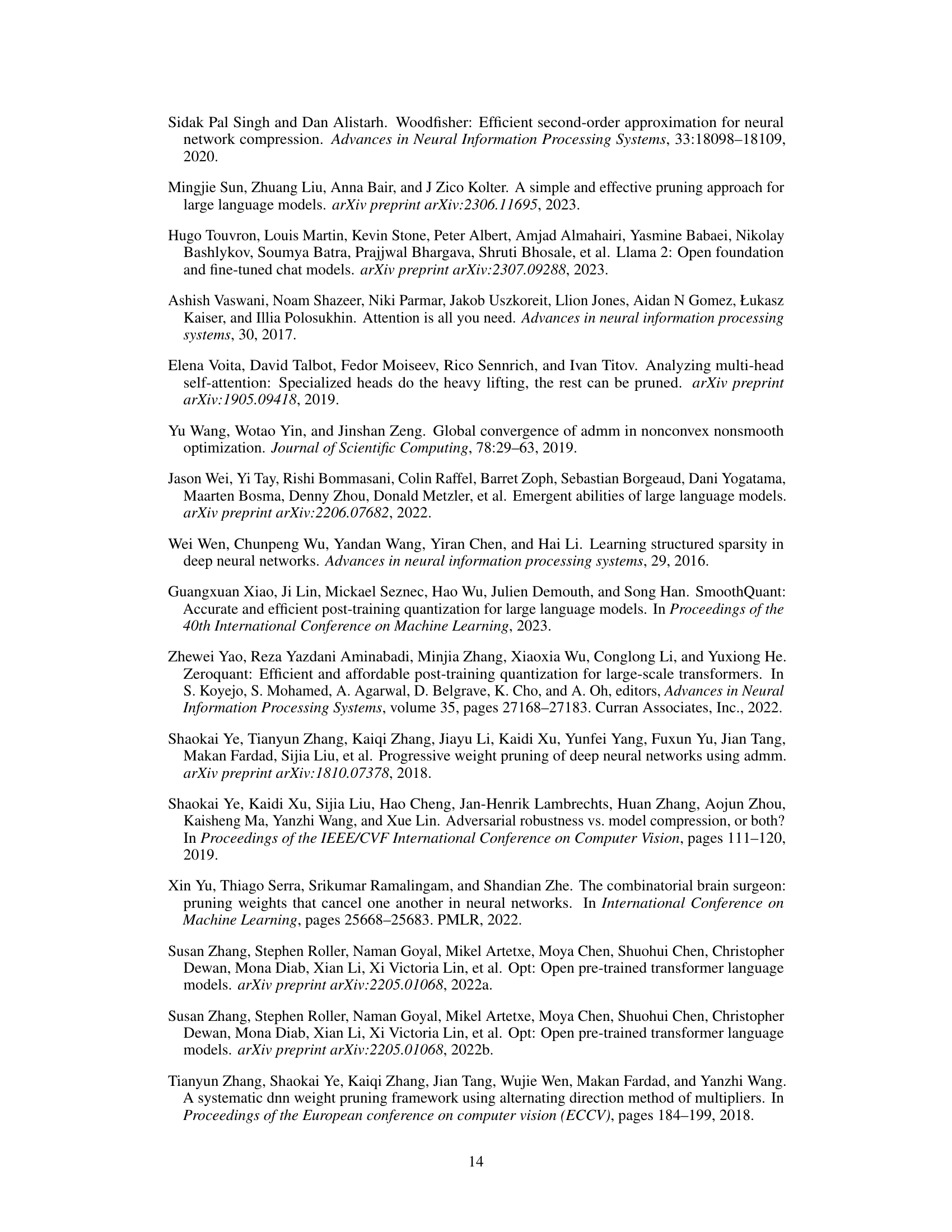

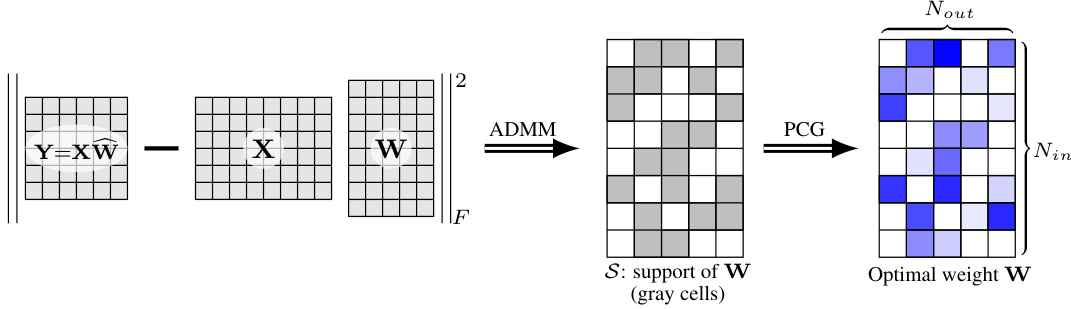

🔼 This figure illustrates the ALPS algorithm’s three main steps. The left panel shows the initial pruning problem setup, where the goal is to find a sparse weight matrix W that minimizes reconstruction error while satisfying a sparsity constraint. The middle panel depicts the ADMM (Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers) step, which uses an iterative process to find the optimal support (non-zero elements) for W, enhanced by a novel p-update scheme. The right panel displays the PCG (Preconditioned Conjugate Gradient) post-processing step, focusing on optimizing the weights within the support found in the previous step for higher efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed ALPS algorithm. (Left) The pruning problem with a layerwise reconstruction objective and an lo constraint on the weights (Section 3.1). (Middle) ADMM with a p-update scheme (Algorithm 1) is employed to determine high-quality support for the weight matrix W (Section 3.2). (Right) The optimization problem is restricted to the obtained support, and a modified PCG method (Algorithm 2) is used to solve for the optimal weight values within the support (Section 3.3).

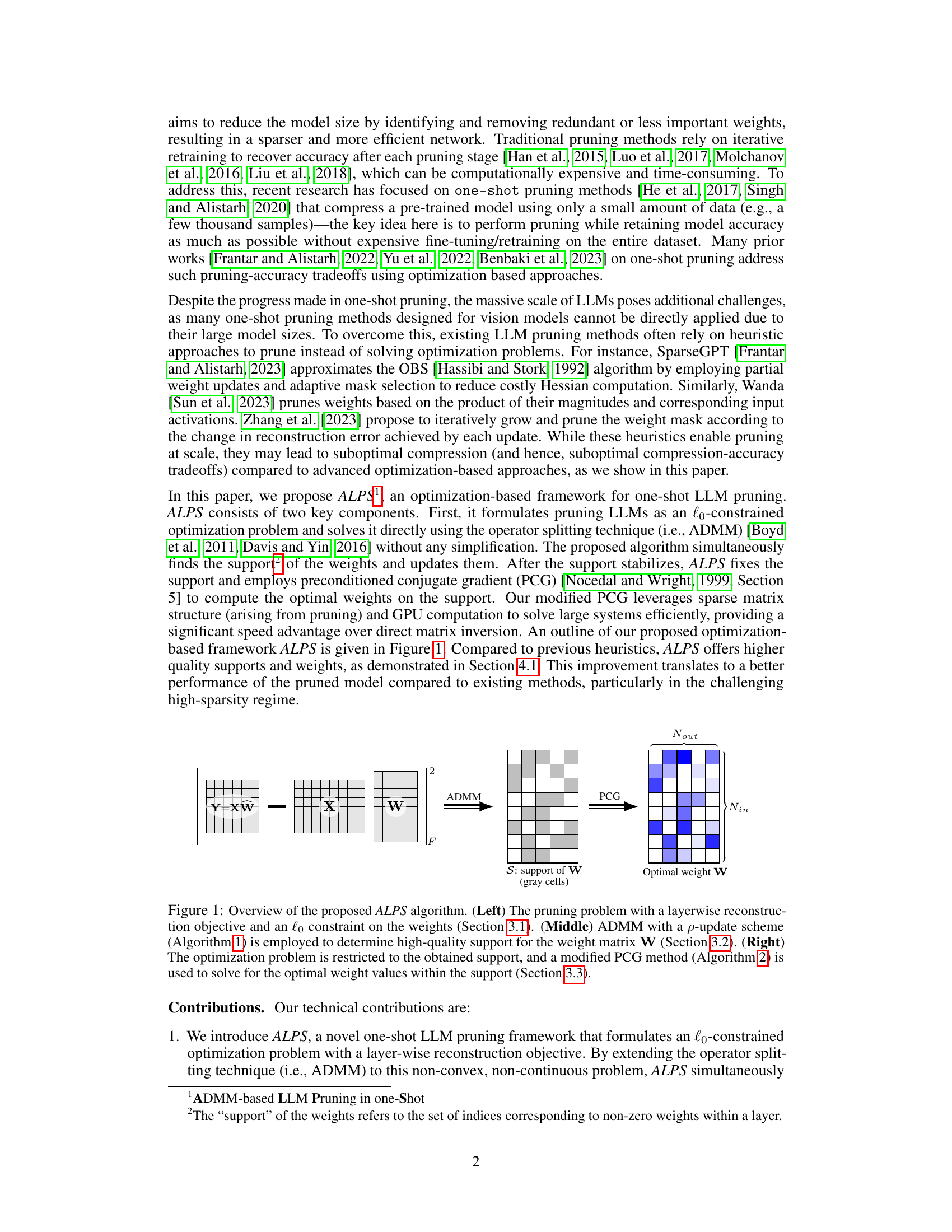

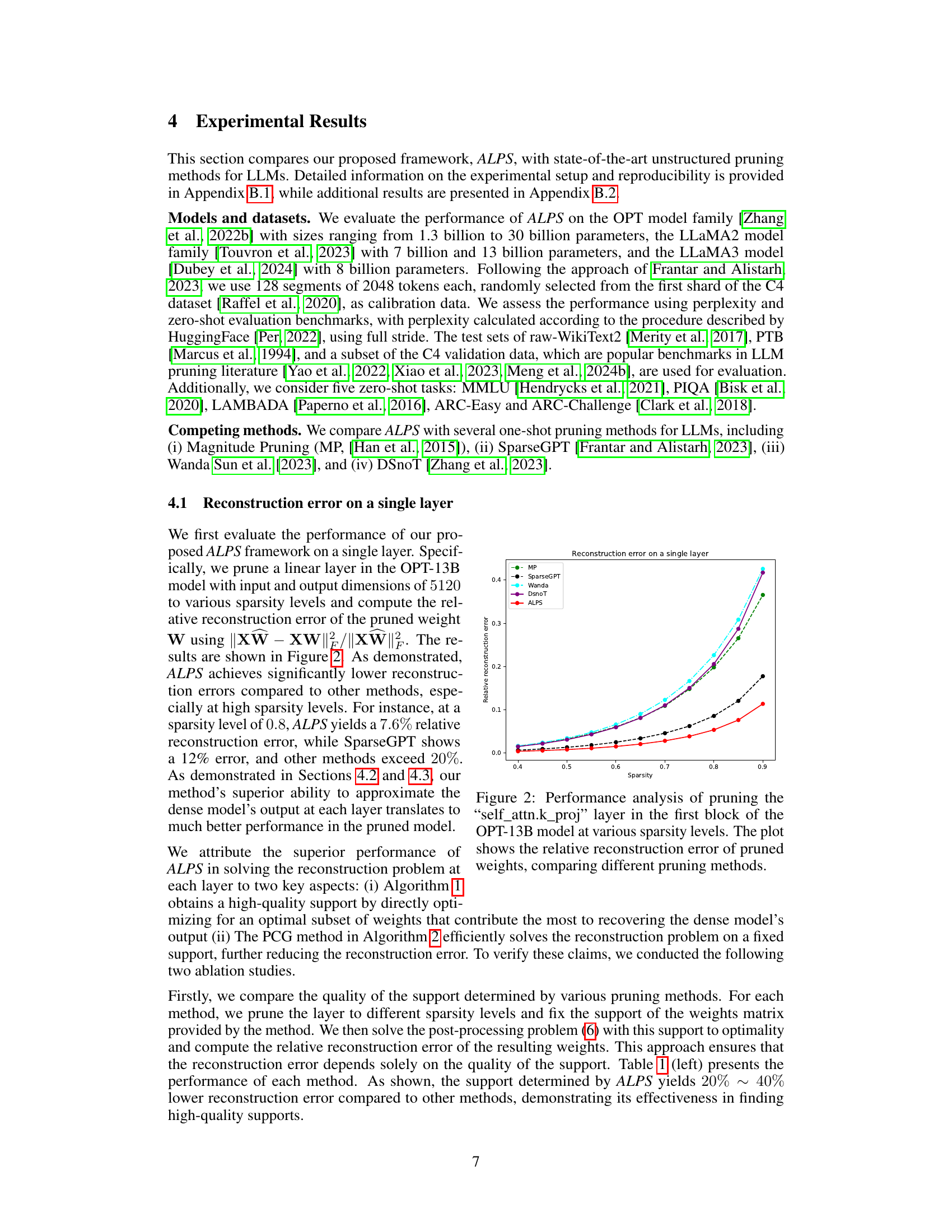

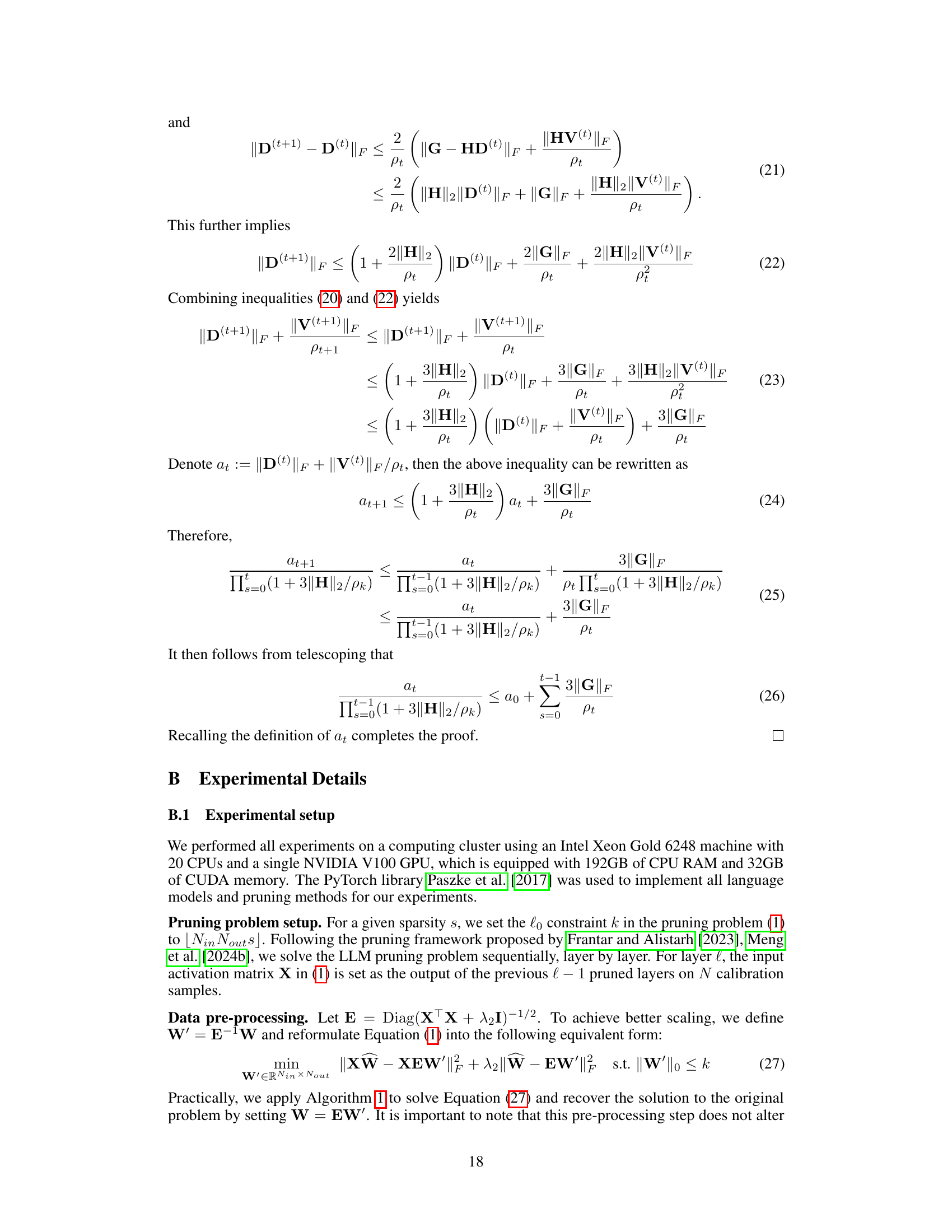

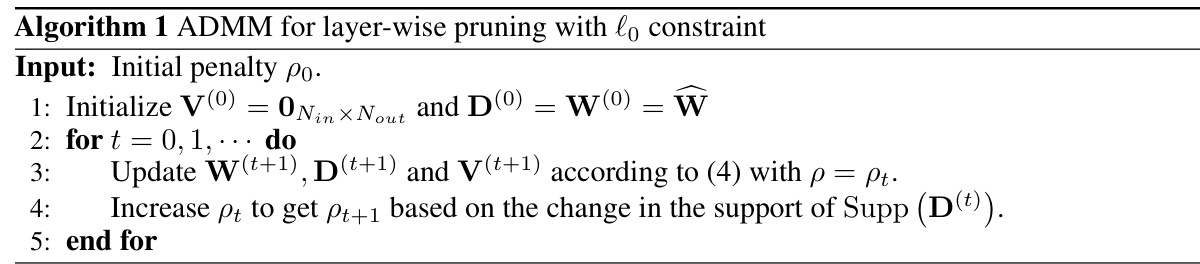

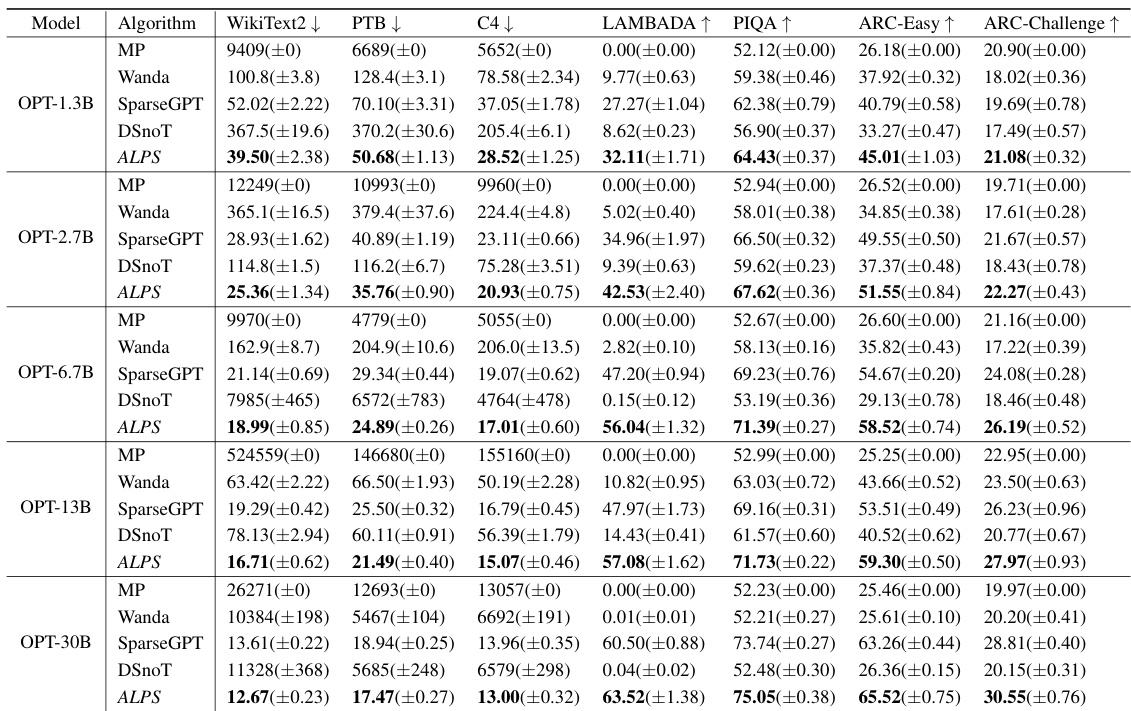

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different pruning methods’ performance on a single layer of the OPT-13B model at different sparsity levels. The left side shows the relative reconstruction error achieved by each method when using the optimal weights constrained to the support determined by each method. The right side compares the time taken and reconstruction error of three different approaches: no post-processing, refining weights using ALPS, and optimal backsolve, all while using magnitude pruning to determine support.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance analysis of pruning the 'self_attn.k_proj' layer in the first block of the OPT-13B model at various sparsity levels. (Left) Relative reconstruction error ||XW – XW||/||XW|| of the optimal weights W constrained to the support determined by each pruning method. (Right) Comparison of time and reconstruction error for three scenarios, all using magnitude pruning to determine the support and then: (i) no post-processing (w/o pp.), (ii) refining the weights with ALPS, and (iii) refining the weights optimally with backsolve.

In-depth insights#

ALPS: One-Shot Pruning#

The research paper explores “ALPS: One-Shot Pruning,” a novel optimization-based framework for effectively pruning Large Language Models (LLMs). One-shot pruning is highlighted as a crucial technique to alleviate the substantial computational and storage demands of LLMs without requiring retraining. The core of ALPS is its use of operator splitting and a preconditioned conjugate gradient (PCG) method. This approach addresses the challenges of existing heuristic methods by directly tackling the pruning problem through optimization. Convergence guarantees are provided, showcasing the theoretical foundation of this technique. ALPS is shown to outperform state-of-the-art methods, particularly in achieving high sparsity levels. Experimental results demonstrate significant improvements in both objective function values and perplexity reduction. The framework also handles various sparsity patterns, adapting to the complexities of LLMs. The availability of code underscores the practical contribution of this research, enabling broader adoption and refinement of the technique.

Optimization Framework#

The core of the research paper revolves around a novel optimization framework for efficient one-shot pruning of Large Language Models (LLMs). This framework addresses the challenges of existing LLM pruning methods, which often rely on heuristics instead of optimization-based approaches, leading to suboptimal compression. ALPS, the proposed framework, employs operator splitting techniques (ADMM) and a preconditioned conjugate gradient (PCG) based post-processing step to solve the pruning problem as a constrained optimization problem. The ADMM component efficiently identifies a high-quality weight support (non-zero weights), while the PCG step refines weight values within that support. Theoretical guarantees of convergence are established for the algorithm, demonstrating its robustness. Furthermore, vectorization and GPU parallelism are used for accelerated computation, showcasing its efficiency, especially for large-scale LLMs. The framework’s performance surpasses state-of-the-art methods, significantly reducing perplexity and improving zero-shot benchmark results, especially in high-sparsity scenarios.

LLM Pruning: ADMM#

LLM pruning, aiming to reduce the massive computational cost of large language models (LLMs), presents a significant challenge. One promising approach leverages the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM), an operator-splitting technique well-suited for tackling constrained optimization problems. ADMM’s strength lies in its ability to decompose complex problems into smaller, more manageable subproblems, making it particularly useful for the high-dimensional nature of LLMs. In the context of LLM pruning, ADMM can be employed to simultaneously identify and remove less important weights (sparsity pattern optimization) while simultaneously optimizing the remaining weights. This dual optimization process can yield superior compression rates compared to traditional heuristic methods, that often rely on suboptimal approximations. However, the scalability of ADMM itself for extremely large LLMs presents practical hurdles. Thus, efficient implementations leveraging vectorization and GPU parallelism are essential to overcome these computational bottlenecks. Furthermore, the convergence properties of ADMM for non-convex LLM weight spaces need thorough theoretical examination to guarantee the quality of solutions obtained. The application of ADMM in LLM pruning thus represents a powerful optimization-based framework, but its successful implementation necessitates careful consideration of computational efficiency and rigorous theoretical analysis.

PCG Post-Processing#

The heading ‘PCG Post-Processing’ suggests a crucial step in the proposed ALPS algorithm for efficient Large Language Model (LLM) pruning. After the initial ADMM (Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers) phase, which identifies a high-quality support (set of non-zero weights), the PCG (Preconditioned Conjugate Gradient) method refines the weights within this support. This post-processing is essential because ADMM, while effective in finding the support, might not precisely optimize the weights themselves. PCG, designed to solve large linear systems efficiently, leverages the sparsity generated by ADMM, leading to significant speed improvements over direct matrix inversion. This two-step approach, combining ADMM and PCG, enables ALPS to achieve high-quality weight supports and optimal weights, which is critical for both effective pruning and maintaining the accuracy of the pruned LLM. The use of vectorization and GPU parallelism further enhances PCG’s performance, making it suitable for LLMs with millions or billions of parameters. Therefore, this post-processing step is not merely an optimization but a core element enabling efficient high-quality pruning.

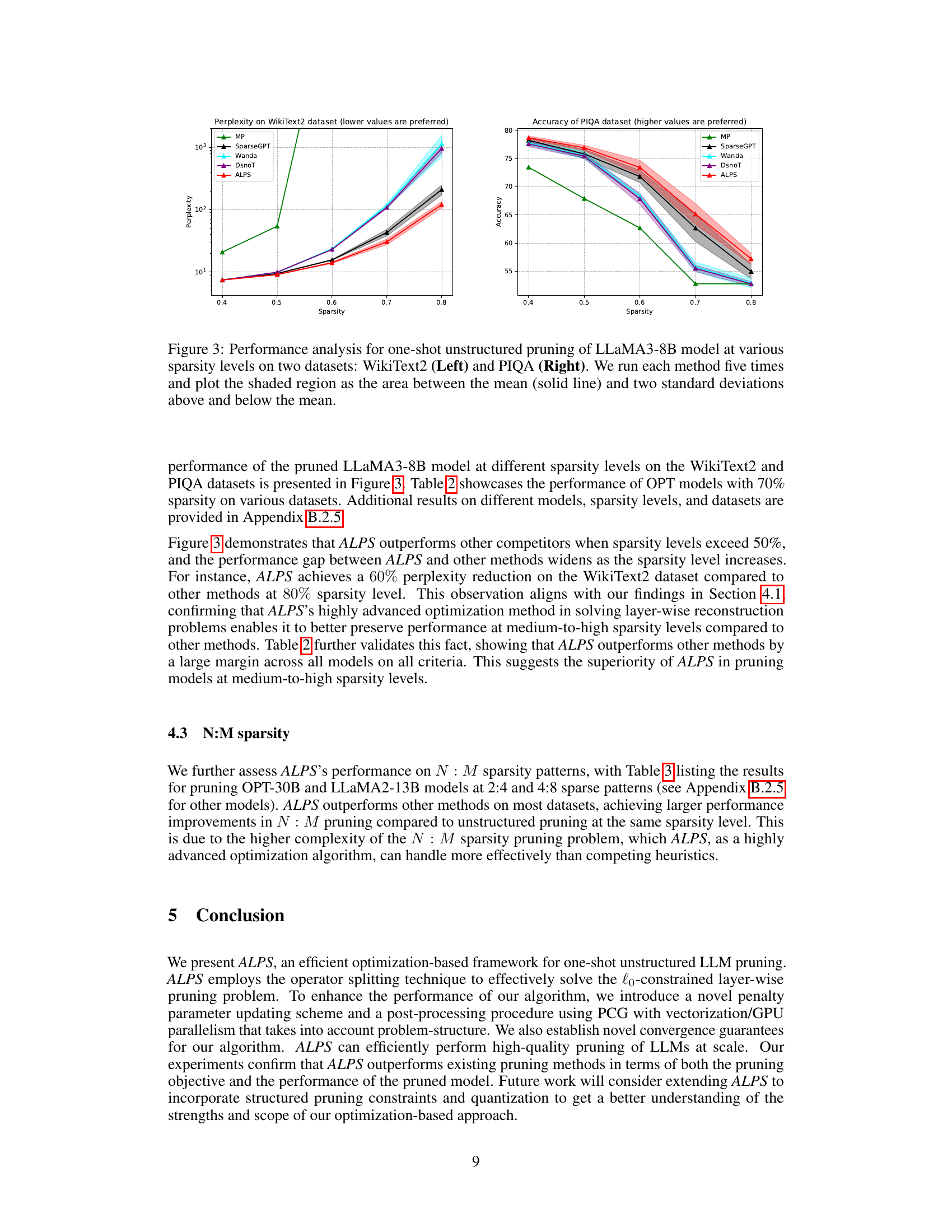

Sparse LLM Results#

An analysis of “Sparse LLM Results” would require examining the paper’s methodology for achieving sparsity in large language models (LLMs), the metrics used to evaluate the performance of sparse LLMs, and a comparison of the results with those of dense LLMs. Key aspects to consider would include the sparsity level achieved, the impact on model size and inference speed, and the trade-off between sparsity and performance. Different sparsity techniques (e.g., unstructured, structured) impact results differently and should be noted. The choice of evaluation metrics (e.g., perplexity, accuracy on downstream tasks) significantly influences the interpretation of the results, highlighting the importance of considering multiple metrics. Finally, a discussion of the generalizability of the findings to other LLMs and datasets is crucial to assessing the overall significance of the research. Comparing sparse LLMs to dense models allows for a comprehensive understanding of the benefits and drawbacks of sparsity, such as reduced computational costs and memory requirements, potentially at the expense of decreased performance. A thorough analysis must also address whether the improvements in efficiency outweigh any performance degradation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the ALPS algorithm’s three main steps. First, the pruning problem is formulated using a layerwise reconstruction objective function and an l0 constraint. Second, the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) with a novel penalty parameter update scheme (Algorithm 1) finds the optimal support of the weight matrix. Finally, a modified Preconditioned Conjugate Gradient (PCG) method (Algorithm 2) refines the weights within the obtained support.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed ALPS algorithm. (Left) The pruning problem with a layerwise reconstruction objective and an lo constraint on the weights (Section 3.1). (Middle) ADMM with a p-update scheme (Algorithm 1) is employed to determine high-quality support for the weight matrix W (Section 3.2). (Right) The optimization problem is restricted to the obtained support, and a modified PCG method (Algorithm 2) is used to solve for the optimal weight values within the support (Section 3.3).

🔼 This figure illustrates the ALPS algorithm, which consists of three stages: (1) problem formulation where the LLM pruning is presented as an optimization problem. (2) ADMM with p-update that determines the support for the weight matrix. (3) Modified PCG that solves the optimization problem with obtained support and gives optimal weight values. Each stage is visually represented as a block in the diagram.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed ALPS algorithm. (Left) The pruning problem with a layerwise reconstruction objective and an lo constraint on the weights (Section 3.1). (Middle) ADMM with a p-update scheme (Algorithm 1) is employed to determine high-quality support for the weight matrix W (Section 3.2). (Right) The optimization problem is restricted to the obtained support, and a modified PCG method (Algorithm 2) is used to solve for the optimal weight values within the support (Section 3.3).

More on tables

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different pruning methods’ performance on a single layer of the OPT-13B model at various sparsity levels. The left side shows the relative reconstruction error achieved by each method, while the right side compares the runtime and reconstruction error with and without post-processing using the ALPS method and a standard backsolve method.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance analysis of pruning the 'self_attn.k_proj' layer in the first block of the OPT-13B model at various sparsity levels. (Left) Relative reconstruction error ||XW – XW||/||XW|| of the optimal weights W constrained to the support determined by each pruning method. (Right) Comparison of time and reconstruction error for three scenarios, all using magnitude pruning to determine the support and then: (i) no post-processing (w/o pp.), (ii) refining the weights with ALPS, and (iii) refining the weights optimally with backsolve.

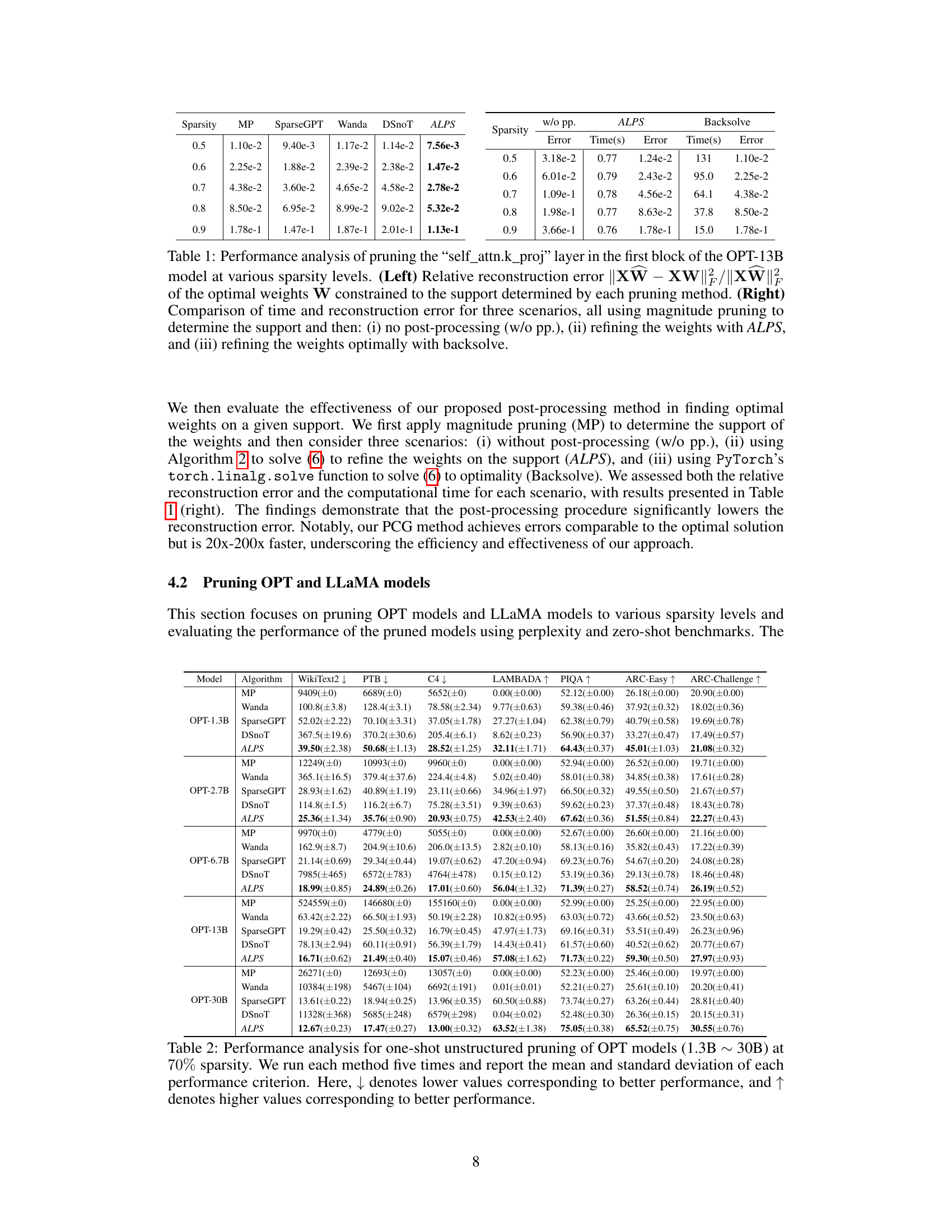

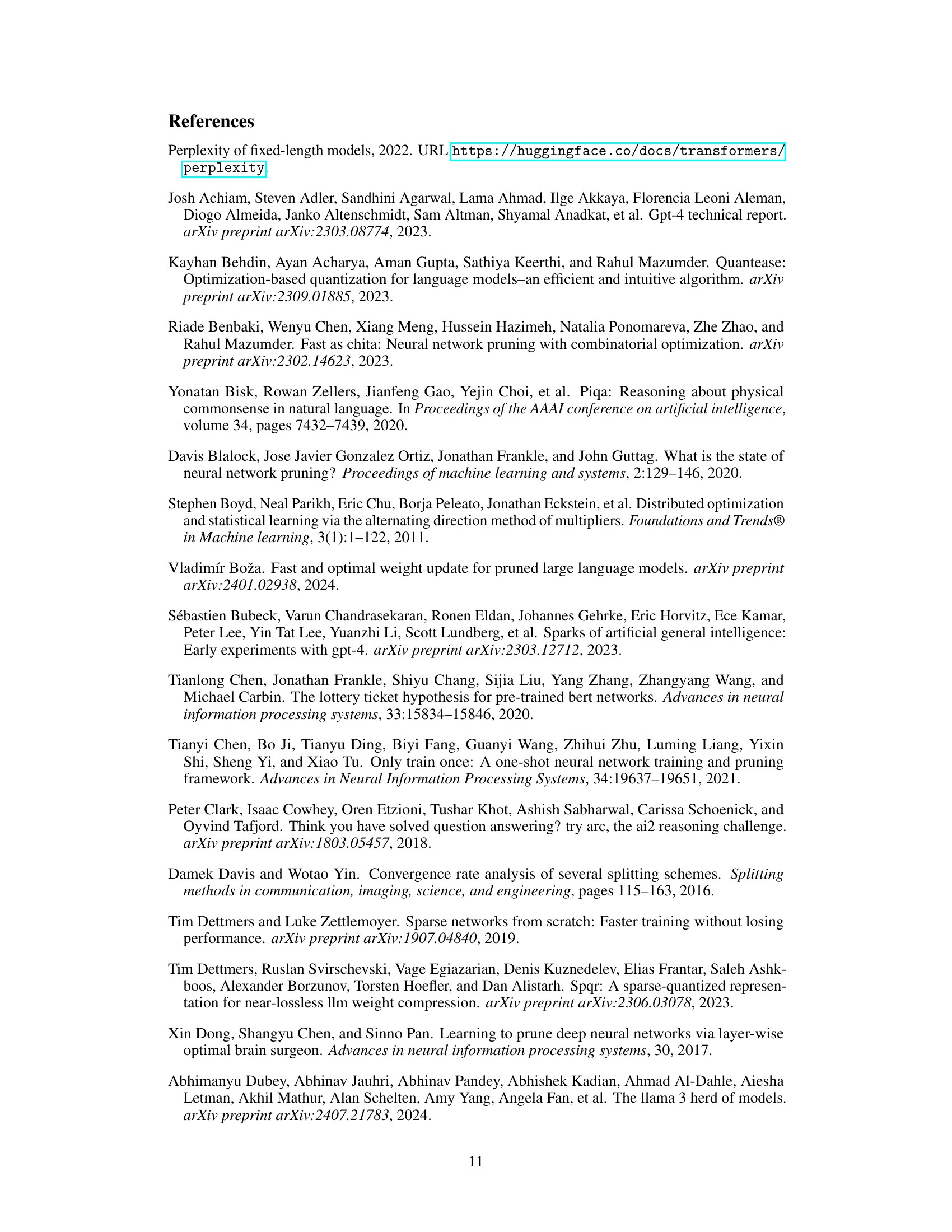

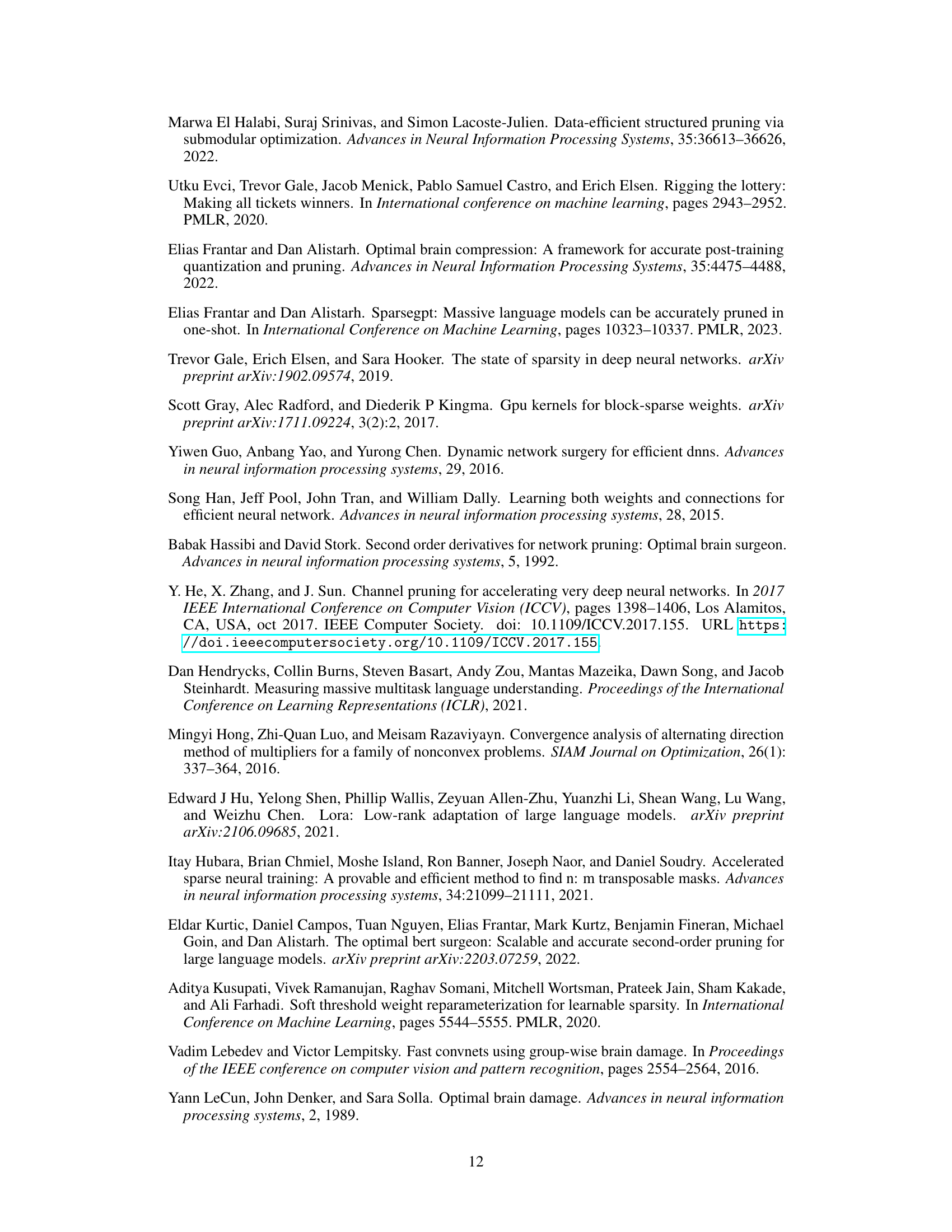

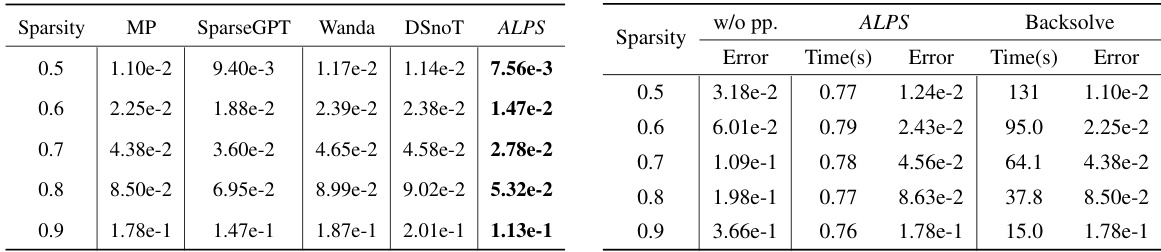

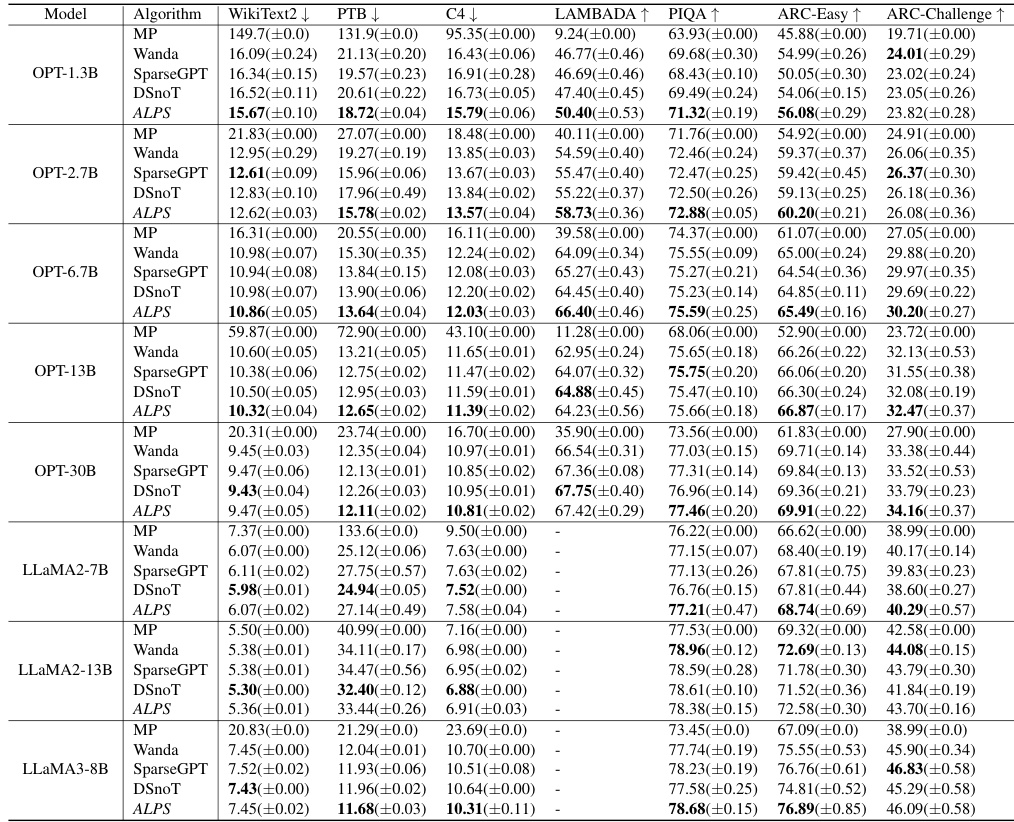

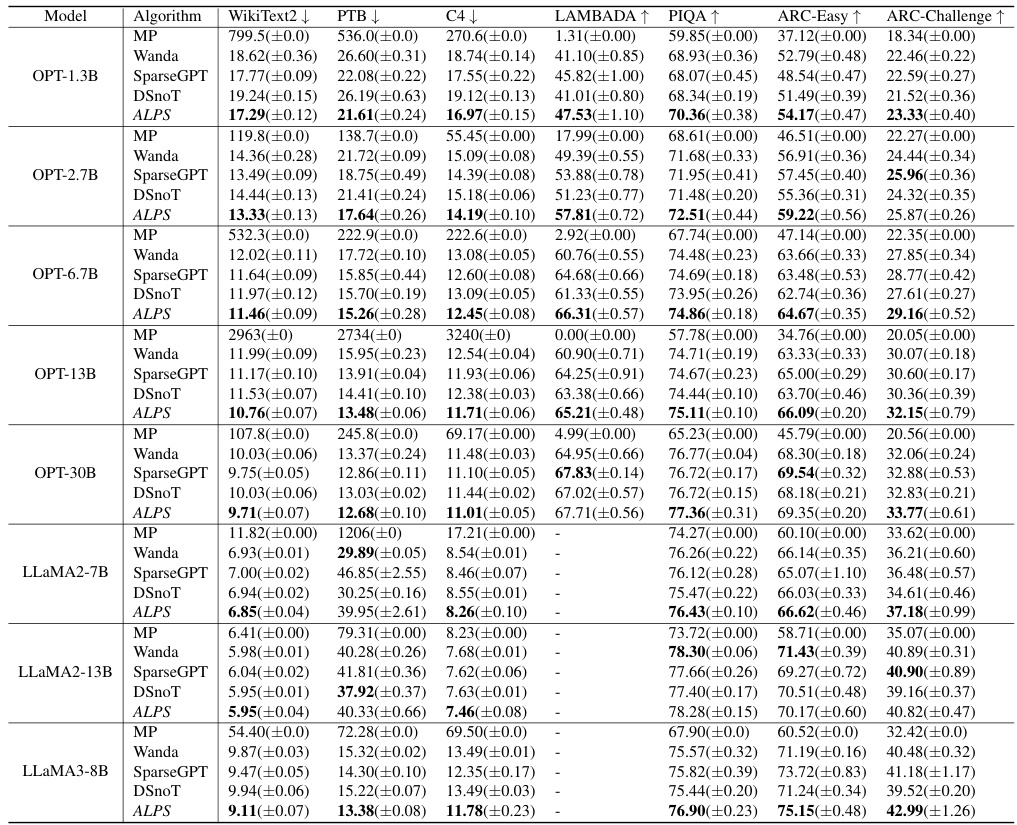

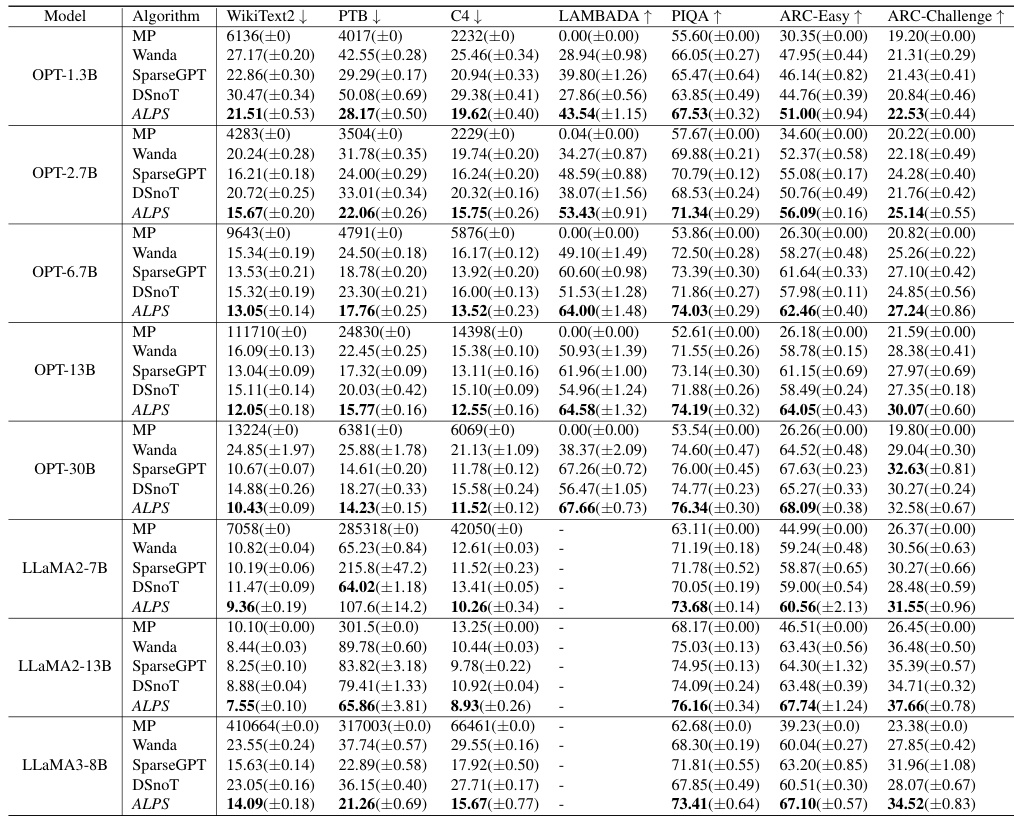

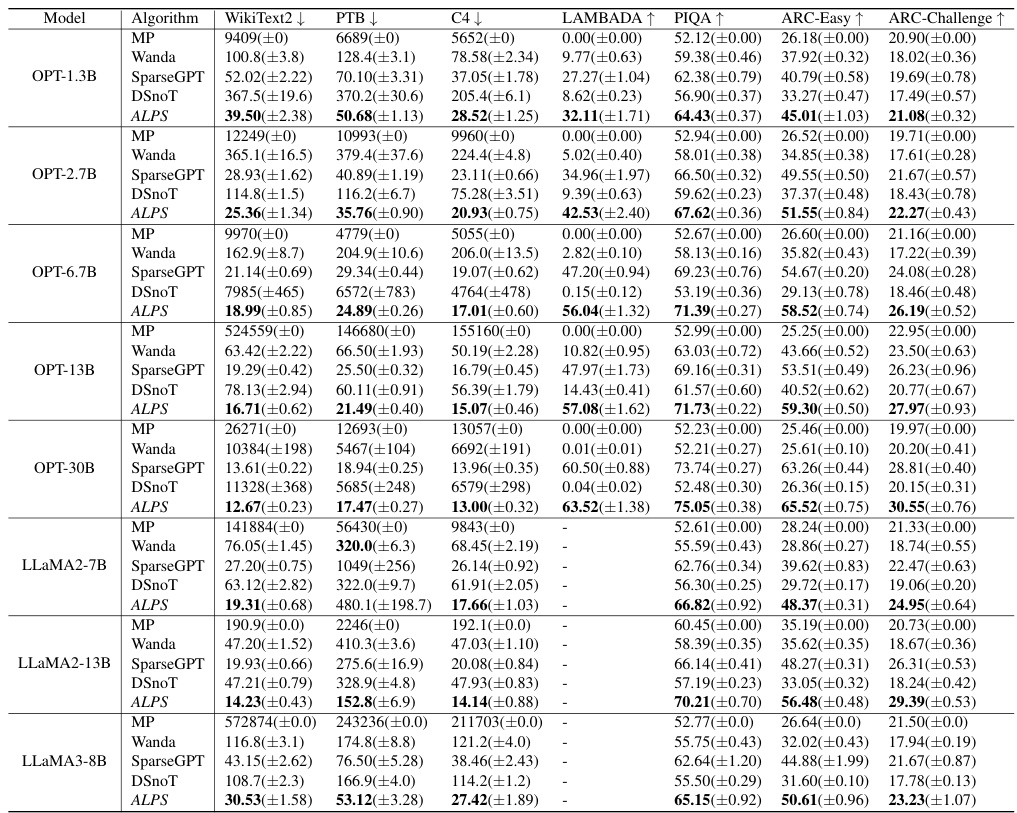

🔼 This table compares the performance of different one-shot unstructured pruning methods (MP, SparseGPT, Wanda, DSnoT, and ALPS) on various OPT models (1.3B to 30B parameters) at 70% sparsity. The performance is evaluated using perplexity scores on WikiText2, PTB, and C4 datasets, as well as zero-shot performance on five benchmark tasks (MMLU, PIQA, LAMBADA, ARC-Easy, and ARC-Challenge). Lower perplexity scores and higher zero-shot accuracy scores indicate better performance. The mean and standard deviation are reported for each metric.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance analysis for one-shot unstructured pruning of OPT models (1.3B ~ 30B) at 70% sparsity. We run each method five times and report the mean and standard deviation of each performance criterion. Here, ↓ denotes lower values corresponding to better performance, and ↑ denotes higher values corresponding to better performance.

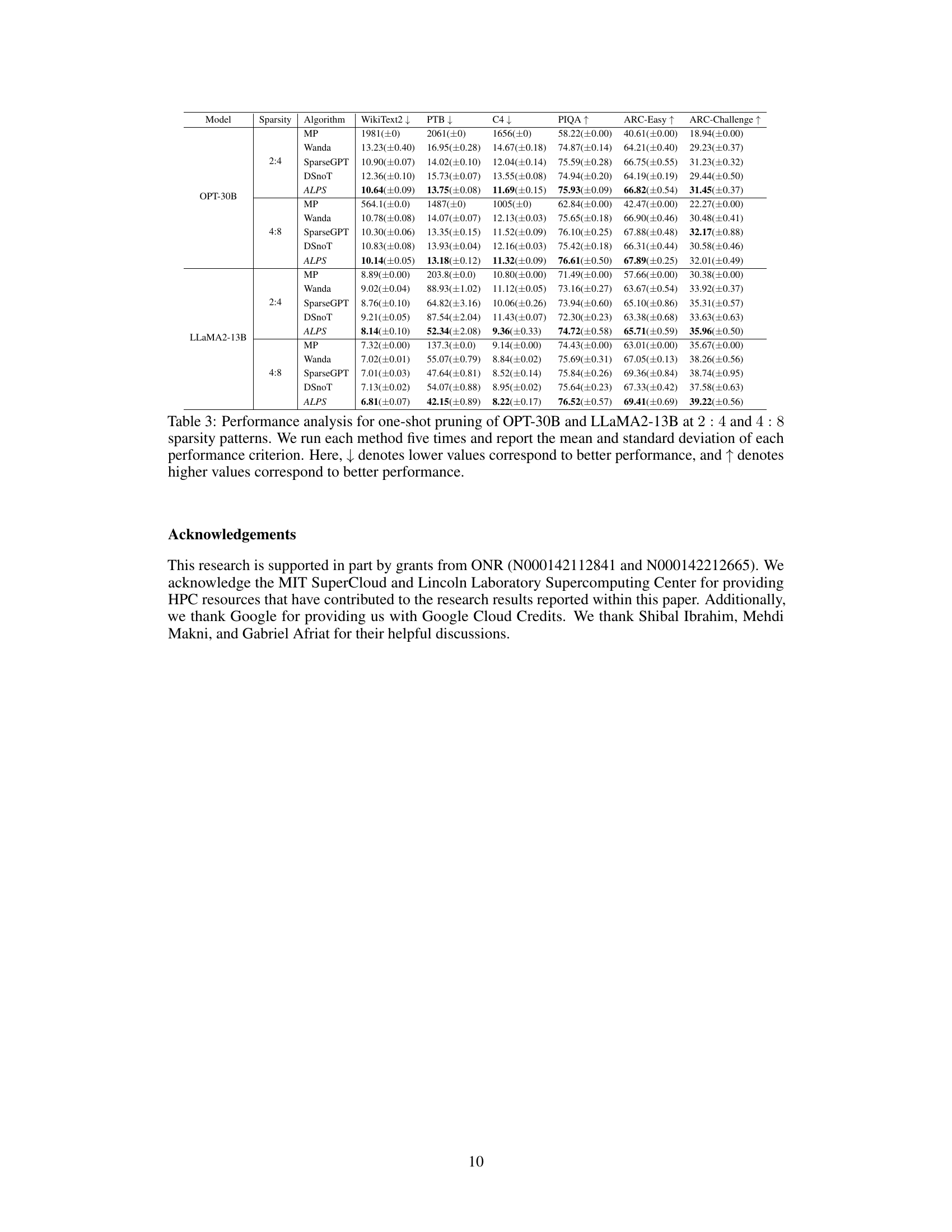

🔼 This table compares the performance of different one-shot pruning methods (MP, Wanda, SparseGPT, DSnoT, and ALPS) on OPT-30B and LLaMA2-13B models with N:M sparsity patterns (2:4 and 4:8). The results are evaluated across multiple metrics: WikiText2 perplexity (lower is better), PTB perplexity (lower is better), C4 perplexity (lower is better), PIQA accuracy (higher is better), ARC-Easy accuracy (higher is better), and ARC-Challenge accuracy (higher is better). Each method is run five times, and the mean and standard deviation are reported.

read the caption

Table 3: Performance analysis for one-shot pruning of OPT-30B and LLaMA2-13B at 2: 4 and 4: 8 sparsity patterns. We run each method five times and report the mean and standard deviation of each performance criterion. Here, ↓ denotes lower values correspond to better performance, and ↑ denotes higher values correspond to better performance.

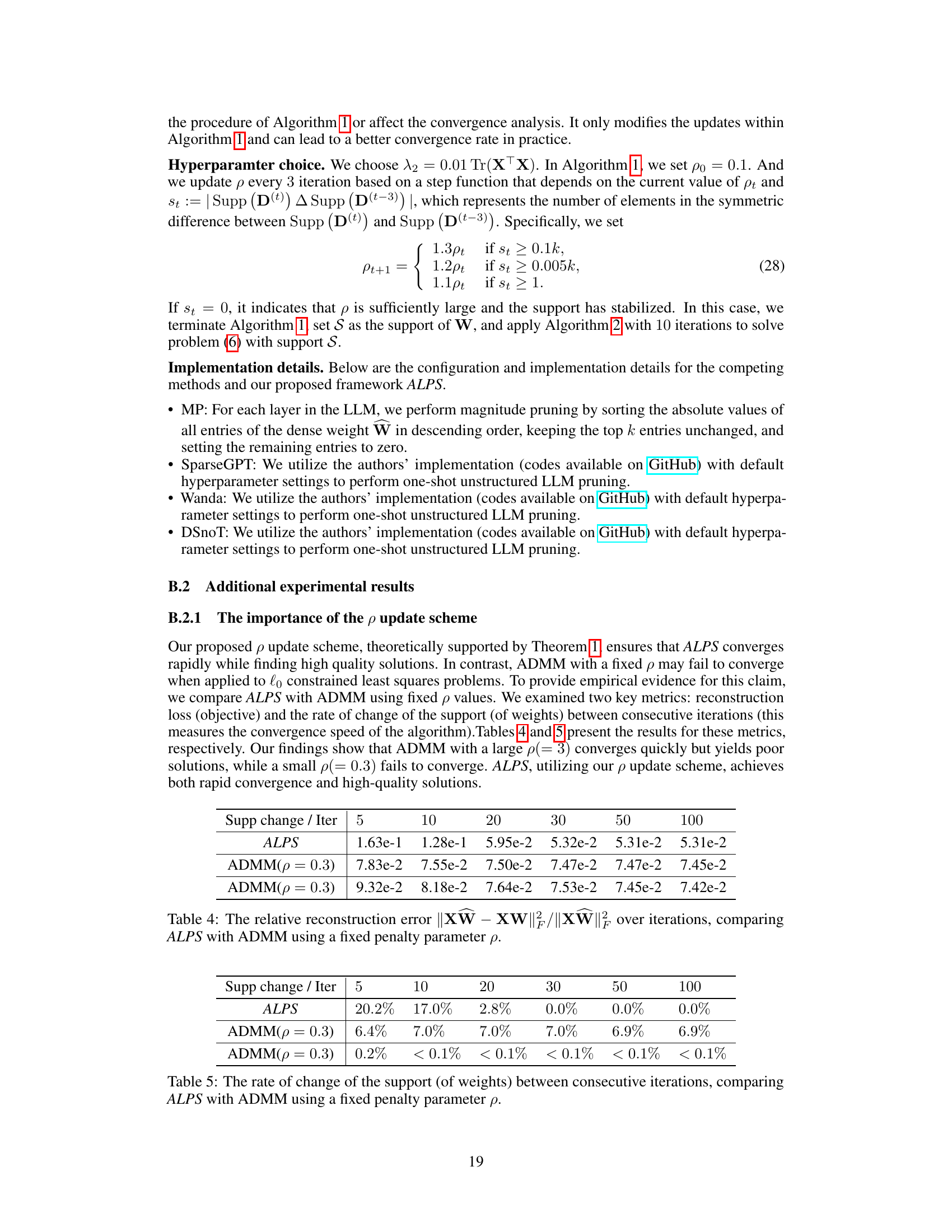

🔼 This table compares the rate of change in the support (indices of non-zero weights) between consecutive iterations for three methods: ALPS and ADMM with two different fixed penalty parameters (p = 0.3 and p = 3). It demonstrates that ALPS, with its adaptive penalty parameter scheme, converges rapidly while maintaining high solution quality, unlike ADMM with fixed parameters, which either converges slowly or converges to a poor solution. The ‘Supp change / Iter’ represents the percentage change in the support between iterations.

read the caption

Table 5: The rate of change of the support (of weights) between consecutive iterations, comparing ALPS with ADMM using a fixed penalty parameter p.

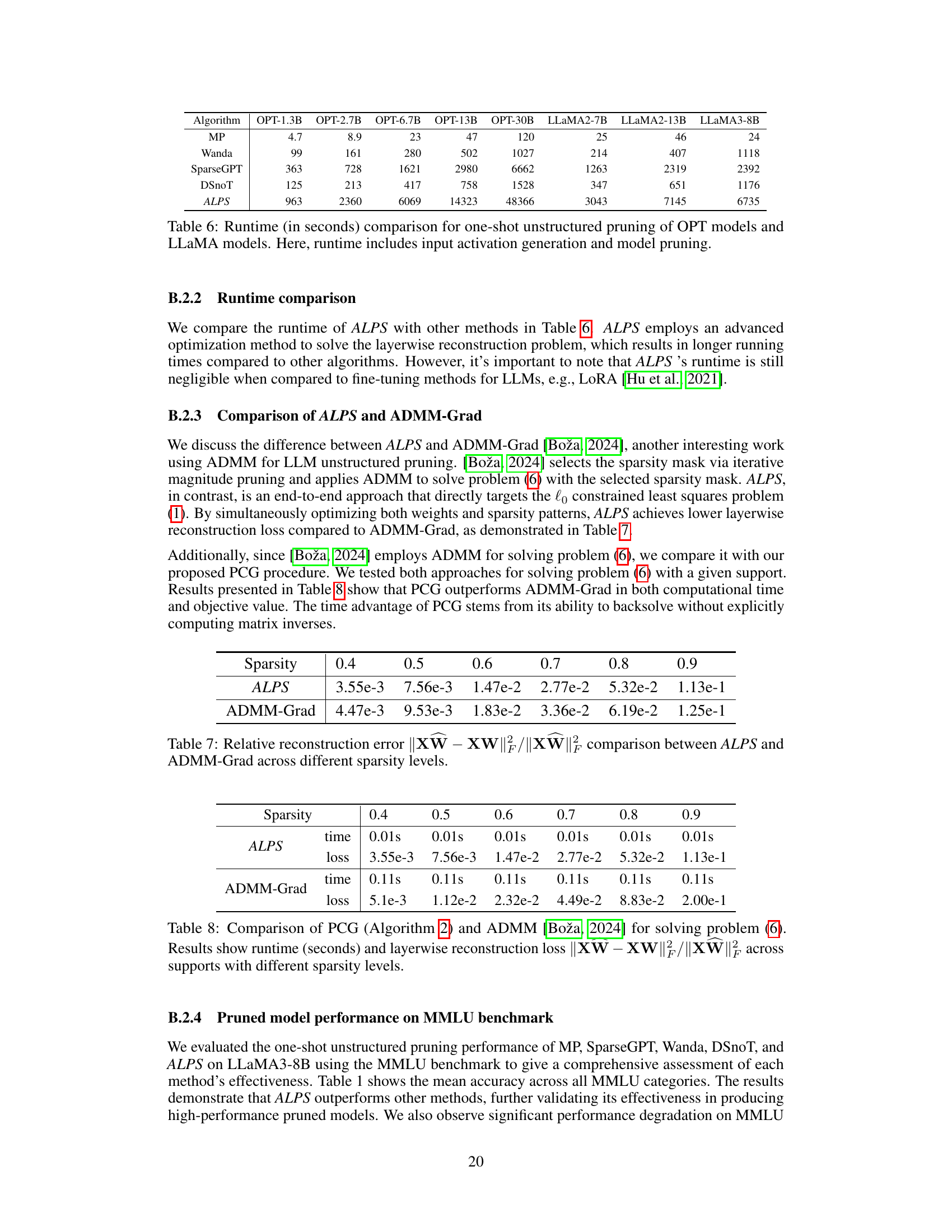

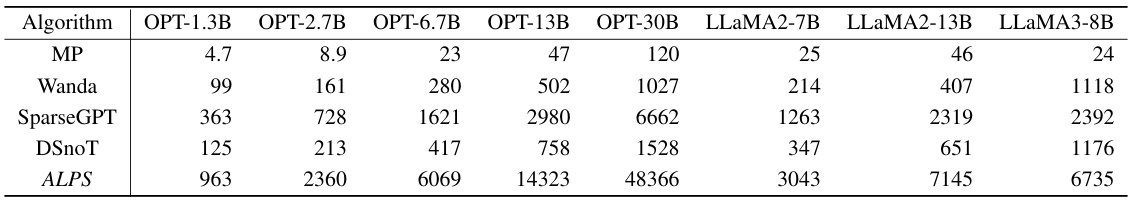

🔼 This table compares the runtime in seconds for different one-shot unstructured pruning methods across various OPT and LLaMA models. The runtime includes the time taken for input activation generation and the model pruning process itself. The table shows a significant increase in runtime for ALPS compared to other methods, which can be attributed to ALPS using a more advanced optimization-based approach for pruning.

read the caption

Table 6: Runtime (in seconds) comparison for one-shot unstructured pruning of OPT models and LLaMA models. Here, runtime includes input activation generation and model pruning.

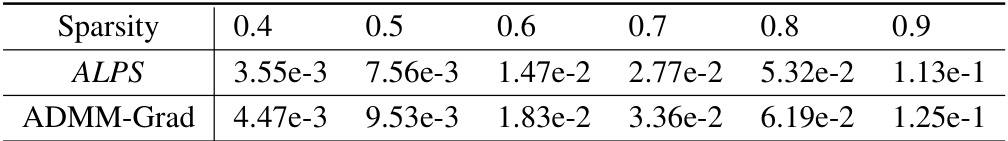

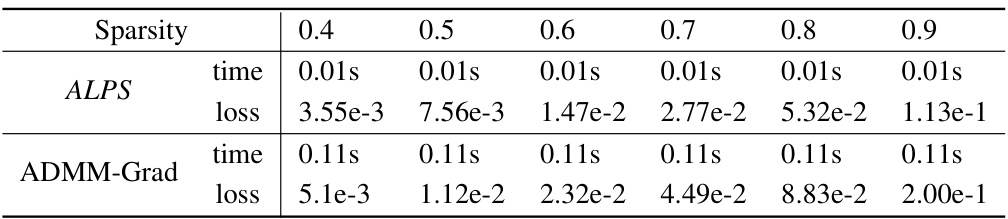

🔼 This table compares the performance of ALPS and ADMM-Grad in terms of relative reconstruction error for a single layer in an OPT-13B model at different sparsity levels (0.4 to 0.9). It demonstrates the superior performance of ALPS in approximating the dense model’s output, particularly at higher sparsity levels.

read the caption

Table 7: Relative reconstruction error ||XW – XW||/||XW|| comparison between ALPS and ADMM-Grad across different sparsity levels.

🔼 This table compares the performance of ALPS and ADMM-Grad in terms of relative reconstruction error at various sparsity levels. The relative reconstruction error measures how well the pruned model approximates the output of the original dense model. Lower values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 7: Relative reconstruction error ||XW – XW||/||XW|| comparison between ALPS and ADMM-Grad across different sparsity levels.

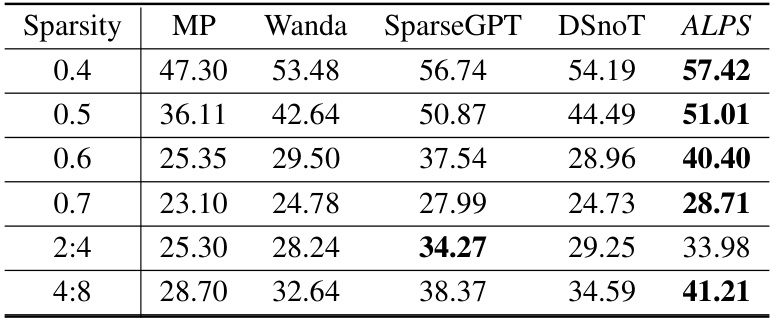

🔼 This table presents the performance of different one-shot unstructured pruning methods (MP, Wanda, SparseGPT, DSnoT, and ALPS) on the LLaMA3-8B model at various sparsity levels (0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 2:4, and 4:8). The performance is measured using the MMLU benchmark, and the table shows the mean accuracy across all MMLU categories for each method and sparsity level. The results demonstrate that ALPS outperforms other methods, especially at high sparsity levels, and further validate its effectiveness in producing high-performance pruned models.

read the caption

Table 9: Performance analysis for one-shot unstructured pruning of LLaMA-3 8B models at various sparsity levels using MMLU benchmark.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different one-shot unstructured pruning methods (MP, SparseGPT, Wanda, DSnoT, and ALPS) on OPT models with varying sizes (1.3B to 30B parameters) at 70% sparsity. The evaluation metrics include perplexity on three datasets (WikiText2, PTB, C4) and zero-shot performance on five tasks (MMLU, PIQA, LAMBADA, ARC-Easy, ARC-Challenge). Lower perplexity scores and higher accuracy scores indicate better performance. The results show the mean and standard deviation of each metric across five independent runs for each method.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance analysis for one-shot unstructured pruning of OPT models (1.3B ~ 30B) at 70% sparsity. We run each method five times and report the mean and standard deviation of each performance criterion. Here, ↓ denotes lower values corresponding to better performance, and ↑ denotes higher values corresponding to better performance.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different one-shot unstructured pruning methods on OPT language models of varying sizes (1.3B to 30B parameters) at a 70% sparsity level. The metrics used to evaluate the performance are perplexity scores on the WikiText2, PTB, and C4 datasets, and zero-shot accuracy scores on five tasks: MMLU, PIQA, LAMBADA, ARC-Easy, and ARC-Challenge. Lower perplexity and higher accuracy scores indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance analysis for one-shot unstructured pruning of OPT models (1.3B ~ 30B) at 70% sparsity. We run each method five times and report the mean and standard deviation of each performance criterion. Here, ↓ denotes lower values corresponding to better performance, and ↑ denotes higher values corresponding to better performance.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of various one-shot unstructured pruning methods on OPT models with 70% sparsity. The metrics used are perplexity (lower is better) on WikiText2, PTB, and C4 datasets, and accuracy (higher is better) on five zero-shot benchmark tasks: MMLU, PIQA, LAMBADA, ARC-Easy, and ARC-Challenge. Each method was run five times, and the table shows mean and standard deviation values for each metric and dataset.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance analysis for one-shot unstructured pruning of OPT models (1.3B ~ 30B) at 70% sparsity. We run each method five times and report the mean and standard deviation of each performance criterion. Here, ↓ denotes lower values corresponding to better performance, and ↑ denotes higher values corresponding to better performance.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different one-shot unstructured pruning methods on OPT models with various sizes (1.3B to 30B parameters) at a sparsity level of 70%. It evaluates five different methods (MP, SparseGPT, Wanda, DSnoT, and ALPS) across multiple metrics including perplexity on WikiText2, PTB, and C4 datasets, and zero-shot performance on five benchmark tasks (MMLU, PIQA, LAMBADA, ARC-Easy, and ARC-Challenge). Lower perplexity values and higher accuracy scores indicate better model performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance analysis for one-shot unstructured pruning of OPT models (1.3B ~ 30B) at 70% sparsity. We run each method five times and report the mean and standard deviation of each performance criterion. Here, ↓ denotes lower values corresponding to better performance, and ↑ denotes higher values corresponding to better performance.

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment comparing different one-shot unstructured pruning methods on OPT language models with 70% sparsity. The methods are evaluated using multiple metrics, including perplexity on three different datasets (WikiText2, Penn Treebank, and C4) and zero-shot performance across five tasks (MMLU, PIQA, LAMBADA, ARC-Easy, and ARC-Challenge). The mean and standard deviation of the results across five runs are shown for each method.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance analysis for one-shot unstructured pruning of OPT models (1.3B ~ 30B) at 70% sparsity. We run each method five times and report the mean and standard deviation of each performance criterion. Here, ↓ denotes lower values corresponding to better performance, and ↑ denotes higher values corresponding to better performance.

🔼 This table presents the results of comparing several one-shot unstructured pruning methods for large language models (LLMs). The models used are from the OPT and LLAMA families, and the evaluation metrics are perplexity scores on WikiText2, PTB, and C4 datasets, along with zero-shot performance scores across five different tasks (MMLU, PIQA, LAMBADA, ARC-Easy, ARC-Challenge). The table shows the mean and standard deviation for each method, across five runs, allowing for a statistical comparison of performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance analysis for one-shot unstructured pruning of OPT models (1.3B ~ 30B) at 70% sparsity. We run each method five times and report the mean and standard deviation of each performance criterion. Here, ↓ denotes lower values corresponding to better performance, and ↑ denotes higher values corresponding to better performance.

🔼 This table presents the results of five different one-shot unstructured pruning methods (MP, SparseGPT, Wanda, DSnoT, and ALPS) applied to OPT models of varying sizes (1.3B to 30B parameters). The models were pruned to 70% sparsity. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the performance across five runs for each method on several metrics: WikiText2 perplexity, PTB perplexity, C4 perplexity, LAMBADA accuracy, PIQA accuracy, ARC-Easy accuracy, and ARC-Challenge accuracy. Lower values are better for perplexity, and higher values are better for accuracy.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance analysis for one-shot unstructured pruning of OPT models (1.3B ~ 30B) at 70% sparsity. We run each method five times and report the mean and standard deviation of each performance criterion. Here, ↓ denotes lower values corresponding to better performance, and ↑ denotes higher values corresponding to better performance.

🔼 This table presents the results of five different one-shot unstructured pruning methods applied to OPT language models of varying sizes (1.3B to 30B parameters). The models were pruned to 70% sparsity. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of perplexity scores on three datasets (WikiText2, PTB, and C4) and zero-shot performance on five benchmark tasks (MMLU, PIQA, LAMBADA, ARC-Easy, and ARC-Challenge). Lower perplexity scores and higher accuracy scores indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance analysis for one-shot unstructured pruning of OPT models (1.3B ~ 30B) at 70% sparsity. We run each method five times and report the mean and standard deviation of each performance criterion. Here, ↓ denotes lower values corresponding to better performance, and ↑ denotes higher values corresponding to better performance.

Full paper#