TL;DR#

Machine learning models heavily rely on precise labeled data, which is often difficult, expensive, or even impossible to obtain. This necessitates methods to effectively learn from imprecise labels, such as noisy labels, partial labels, and supplemental unlabeled data. Existing approaches typically focus on specific imprecise label scenarios, lacking generalizability and scalability across multiple forms of imprecision. This paper addresses this limitation by proposing a unified framework, Imprecise Label Learning (ILL), that leverages Expectation-Maximization (EM) to model imprecise label information. Instead of approximating correct labels, ILL considers the entire distribution of possible labels.

ILL seamlessly adapts to various imprecise label configurations including partial label learning, semi-supervised learning, and noisy label learning, even when these settings coexist. The framework derives closed-form learning objectives, outperforming specified methods on various tasks and showcasing the first practical unified framework. The authors demonstrate its effectiveness across diverse challenging settings and provide code for further research.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a unified framework for handling various imprecise label configurations in machine learning. This addresses a critical challenge in real-world applications where obtaining perfectly labeled data is often expensive or impossible. The framework’s robustness and effectiveness across diverse scenarios make it a valuable tool for researchers, potentially impacting various applications that rely on machine learning with incomplete or imperfect data. The unified approach also reduces the need for separate designs for each imprecise label type, streamlining development and promoting broader applicability.

Visual Insights#

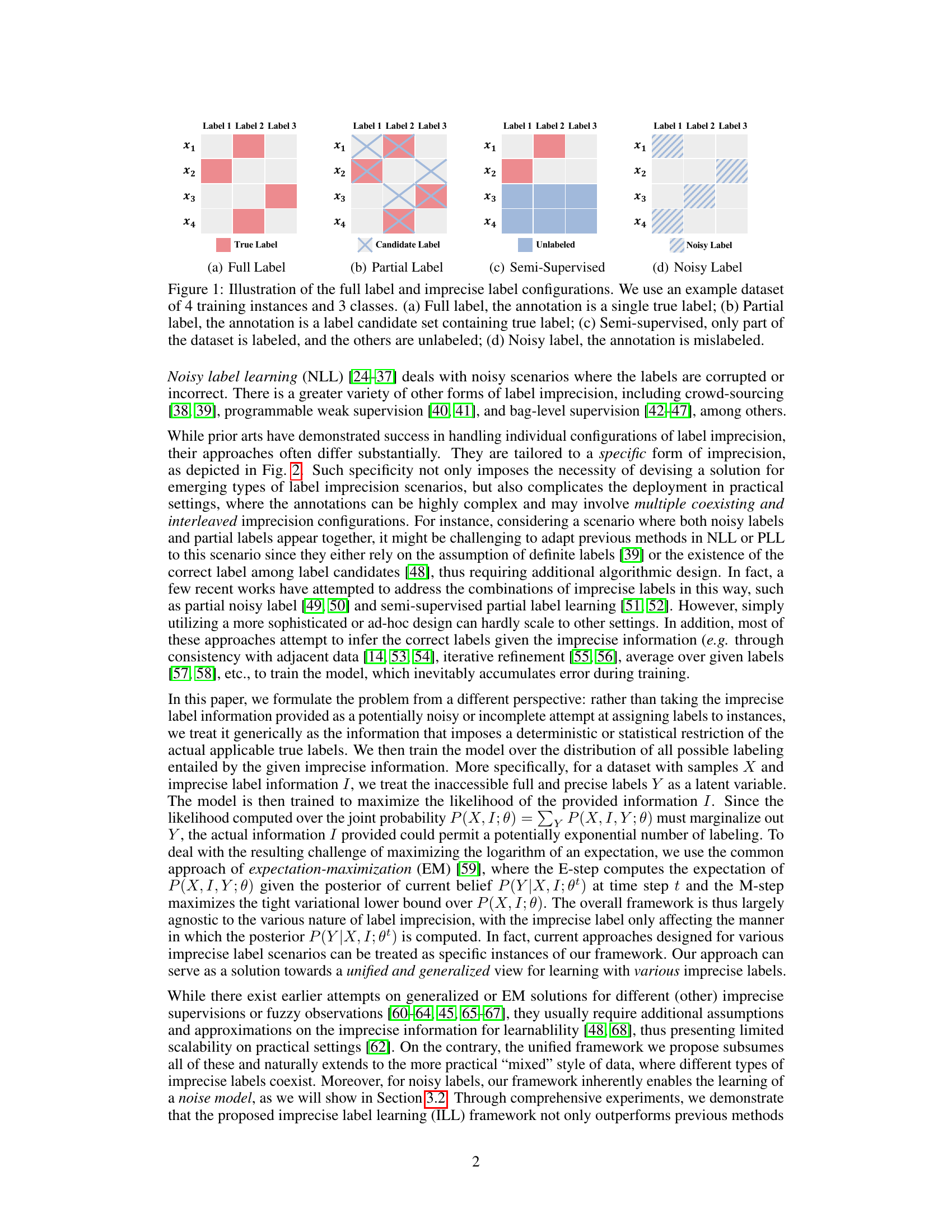

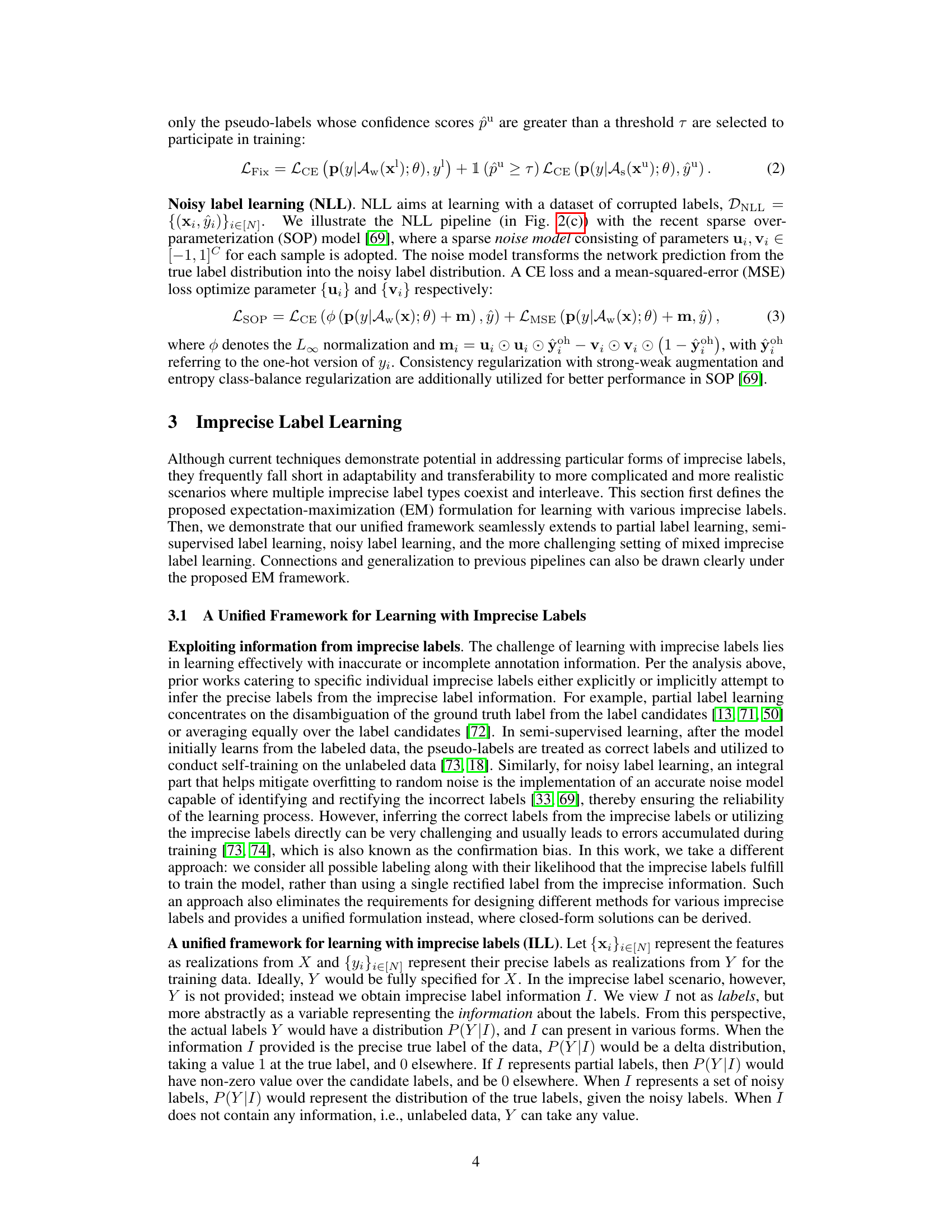

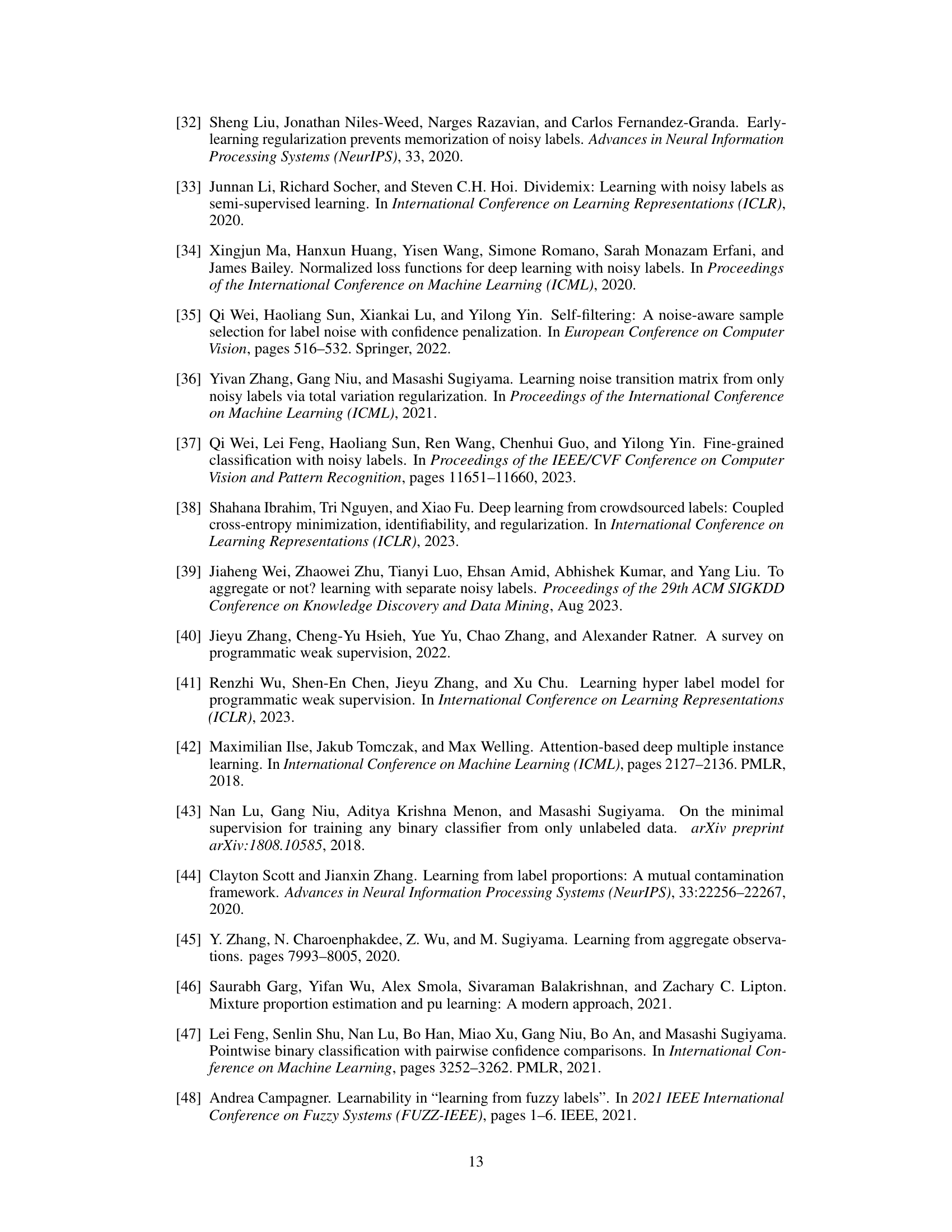

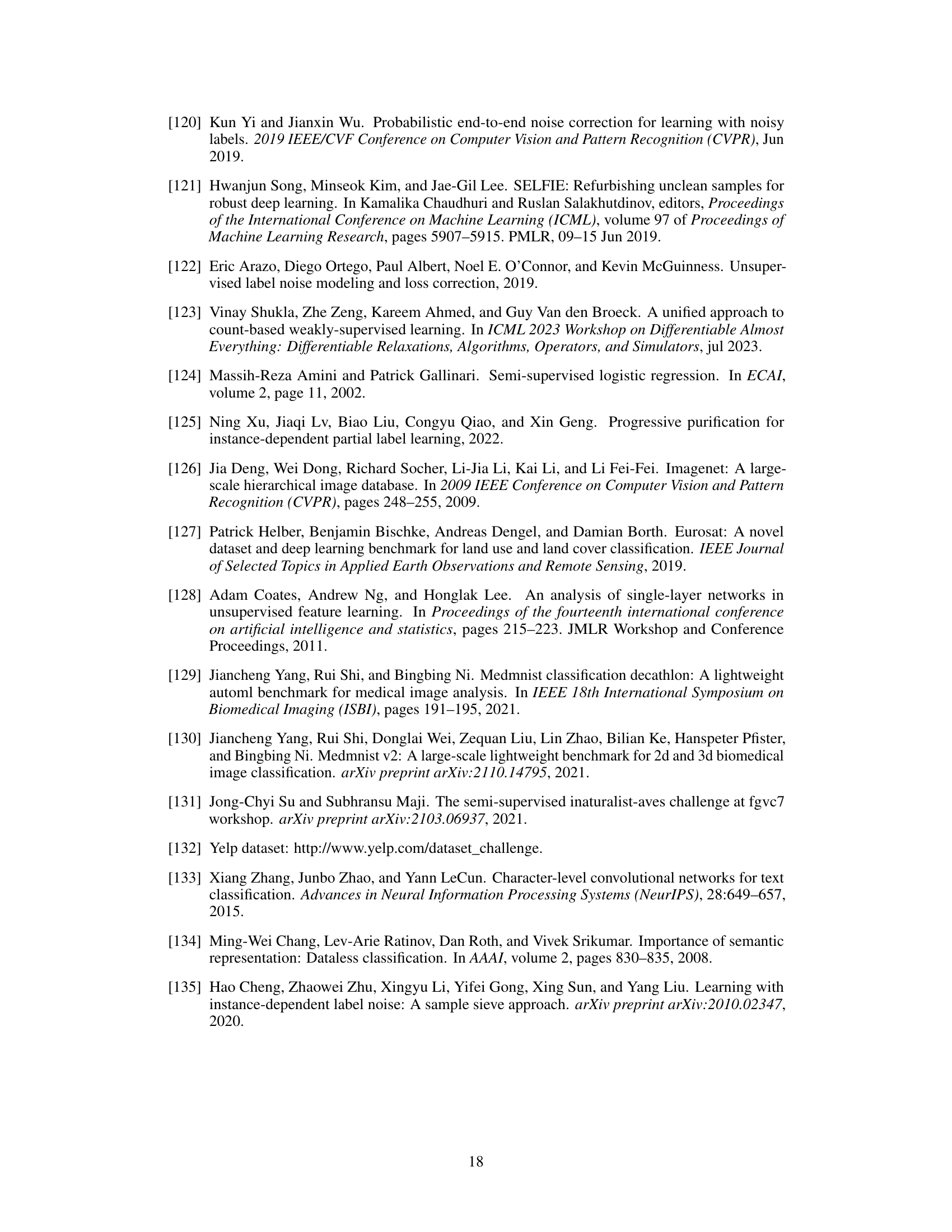

🔼 This figure illustrates four different label configurations used in machine learning: (a) Full Label: Each data point has one correct label; (b) Partial Label: Each data point is associated with a set of candidate labels containing the true label; (c) Semi-Supervised: The dataset is comprised of labeled and unlabeled instances; (d) Noisy Label: The labels are corrupted or inaccurate.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the full label and imprecise label configurations. We use an example dataset of 4 training instances and 3 classes. (a) Full label, the annotation is a single true label; (b) Partial label, the annotation is a label candidate set containing true label; (c) Semi-supervised, only part of the dataset is labeled, and the others are unlabeled; (d) Noisy label, the annotation is mislabeled.

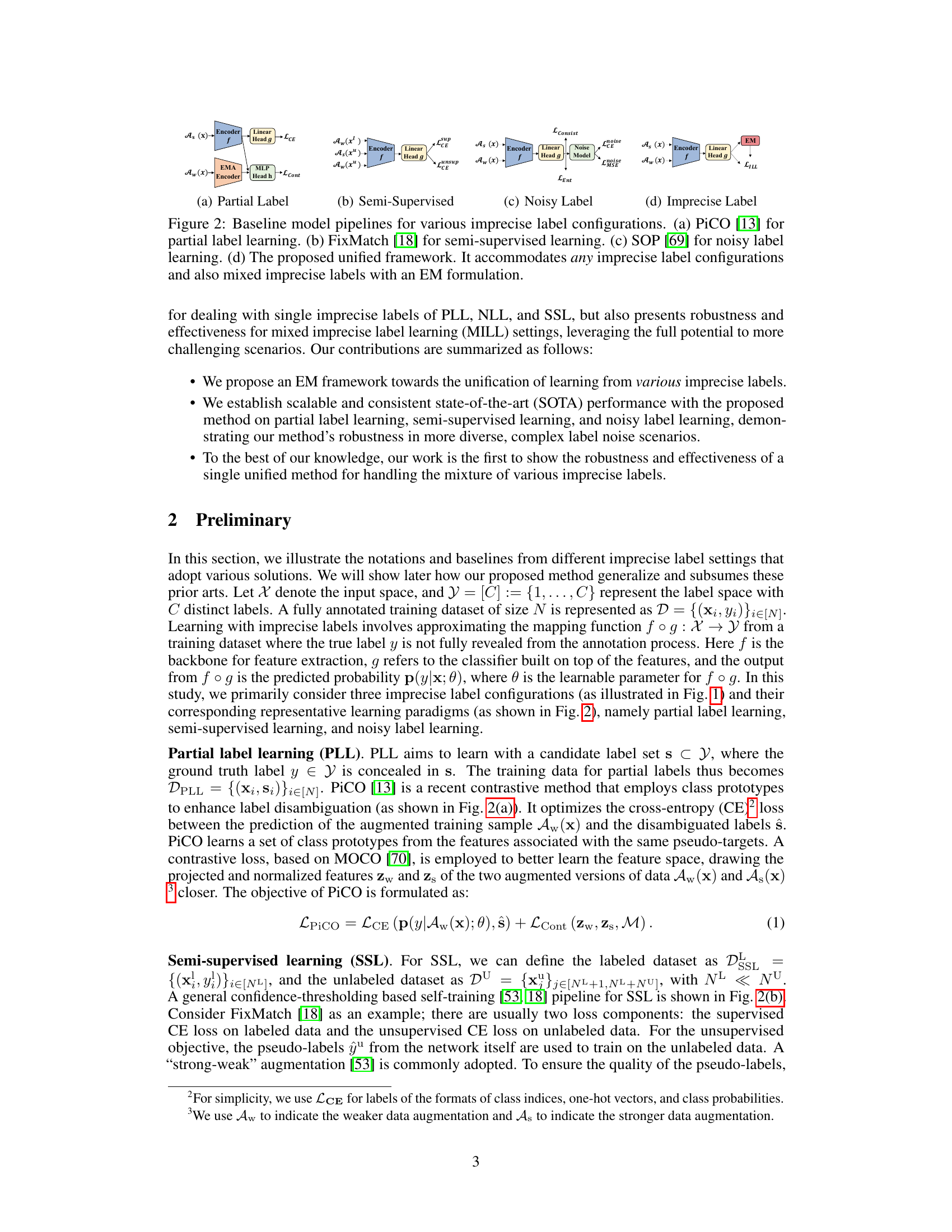

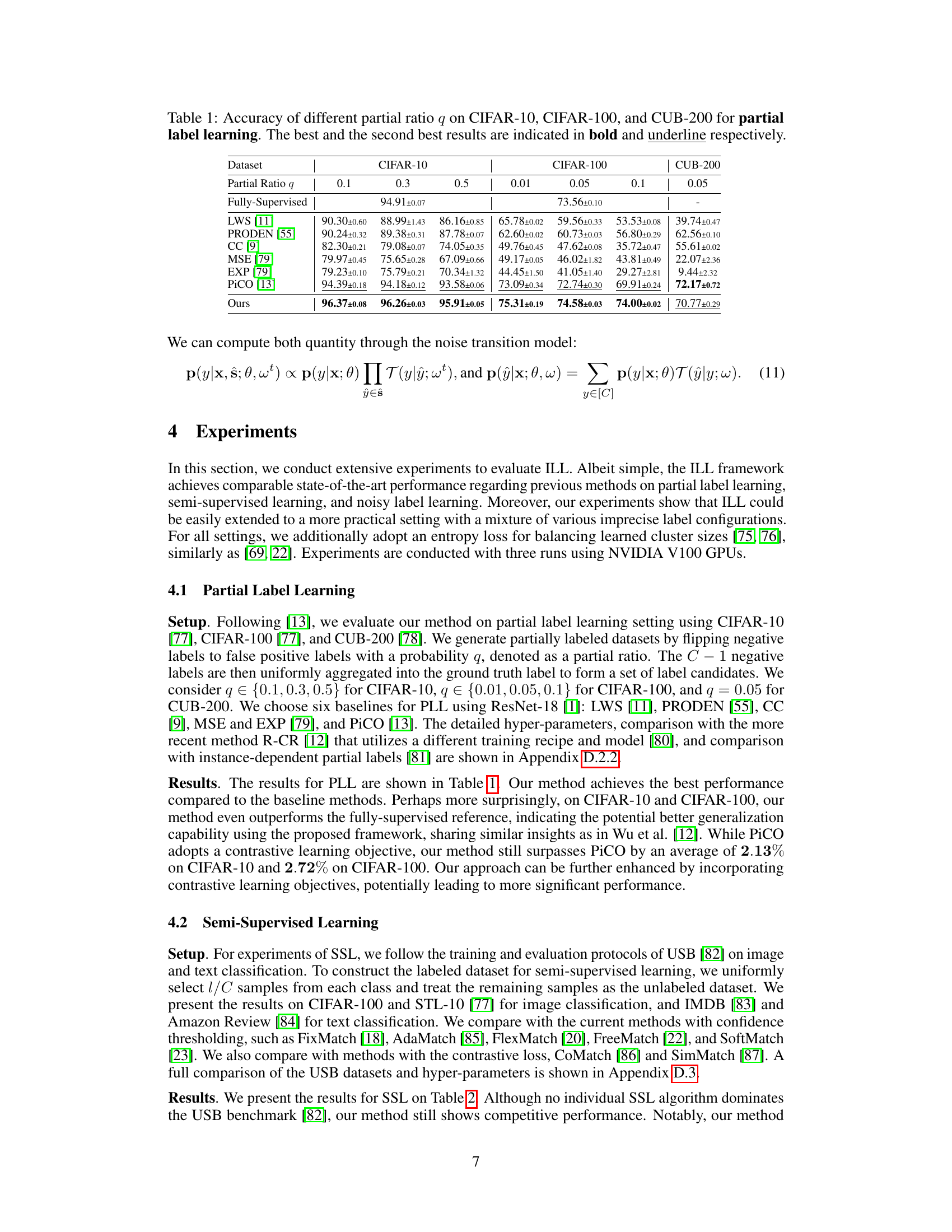

🔼 This table presents the accuracy results of different partial label learning methods on three datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and CUB-200. The accuracy is evaluated for various partial ratios (q), representing the probability of a negative label being flipped to a false positive label. The table shows that the proposed method consistently outperforms other state-of-the-art methods across different datasets and partial ratios.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy of different partial ratio q on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and CUB-200 for partial label learning. The best and the second best results are indicated in bold and underline respectively.

In-depth insights#

Imprecise Label Unification#

Imprecise label unification addresses the critical challenge of inconsistent labeling in machine learning. Instead of designing separate models for various imprecise label types (noisy, partial, or missing labels), a unified framework is proposed. This approach leverages the commonalities across different imprecision forms, treating precise labels as latent variables and utilizing expectation-maximization (EM) to learn from the entire distribution of possible labels. This significantly improves efficiency and robustness compared to handling each imprecise label type individually. The unified framework demonstrates adaptability across various challenging settings and surpasses existing specialized techniques. This generalizability is a significant step forward, offering a more practical and sustainable approach to leveraging the full potential of diverse, real-world datasets.

EM Framework for ILL#

The Expectation-Maximization (EM) framework, applied to Imprecise Label Learning (ILL), offers a unified approach to handling diverse label imperfections. Instead of directly estimating precise labels, which is often inaccurate and computationally expensive, the EM algorithm elegantly models the probability distribution of possible true labels given the imprecise information. This probabilistic perspective enables ILL to seamlessly accommodate various label configurations (noisy, partial, semi-supervised, or mixed) within a single framework. The E-step calculates the expected complete data log-likelihood, while the M-step maximizes it, iteratively refining the model’s parameters. This unified treatment avoids the need for separate algorithms for each type of label imprecision, resulting in a robust and efficient learning process. The elegance of this EM-based ILL lies in its ability to leverage all available information, rather than resorting to ad-hoc label correction strategies, thus improving overall model performance and generalizability.

Unified ILL Approach#

A unified imprecise label learning (ILL) approach offers a significant advancement by tackling the limitations of existing methods. Instead of designing separate models for each imprecise label type (noisy, partial, etc.), a unified framework processes diverse label configurations simultaneously. This is achieved through a robust technique like expectation-maximization (EM), treating precise labels as latent variables and modeling the entire distribution of possible labels. The advantage lies in increased robustness and scalability, handling complex scenarios where multiple types of imprecise labels coexist. This unified approach eliminates the need for ad-hoc solutions, improving both performance and generalization capabilities across various challenging settings. A key feature is the closed-form learning objective derived from EM modeling, enabling seamless adaptation to various imprecise label scenarios. The work’s significance is further emphasized by its practical and effective performance, outperforming specialized techniques and paving the way for wider applications of ILL.

ILL Performance Gains#

The hypothetical section “ILL Performance Gains” in a research paper would delve into the quantitative improvements achieved by the proposed Imprecise Label Learning (ILL) framework. This would involve a detailed comparison against existing state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods across various imprecise label configurations (noisy, partial, semi-supervised, and mixed). Key metrics like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score would be presented, showcasing superior performance of ILL. The analysis would likely highlight specific scenarios where ILL excels, for instance, datasets with high label noise or those combining different forms of imprecise labels. Robustness analysis would demonstrate the consistent performance gains across varying experimental parameters and dataset characteristics. Furthermore, the discussion would likely explore the efficiency of ILL, showing how it achieves SOTA results with potentially fewer computational resources compared to alternative methods. Finally, error bars or confidence intervals would demonstrate the statistical significance of observed improvements.

Future ILL Research#

Future research in imprecise label learning (ILL) could significantly benefit from exploring more sophisticated noise models to capture complex real-world label imperfections. Incorporating uncertainty quantification within ILL frameworks would offer better control over model predictions and robustness. Addressing mixed imprecise label scenarios which are common in practical datasets presents a significant challenge. Developing efficient algorithms suitable for large-scale datasets and high-dimensional data is crucial. Moreover, applying ILL to diverse domains like time-series analysis, natural language processing, and other structured data holds substantial potential. Finally, investigating the theoretical properties of ILL, including generalization bounds and convergence guarantees, warrants further attention.

More visual insights#

More on tables

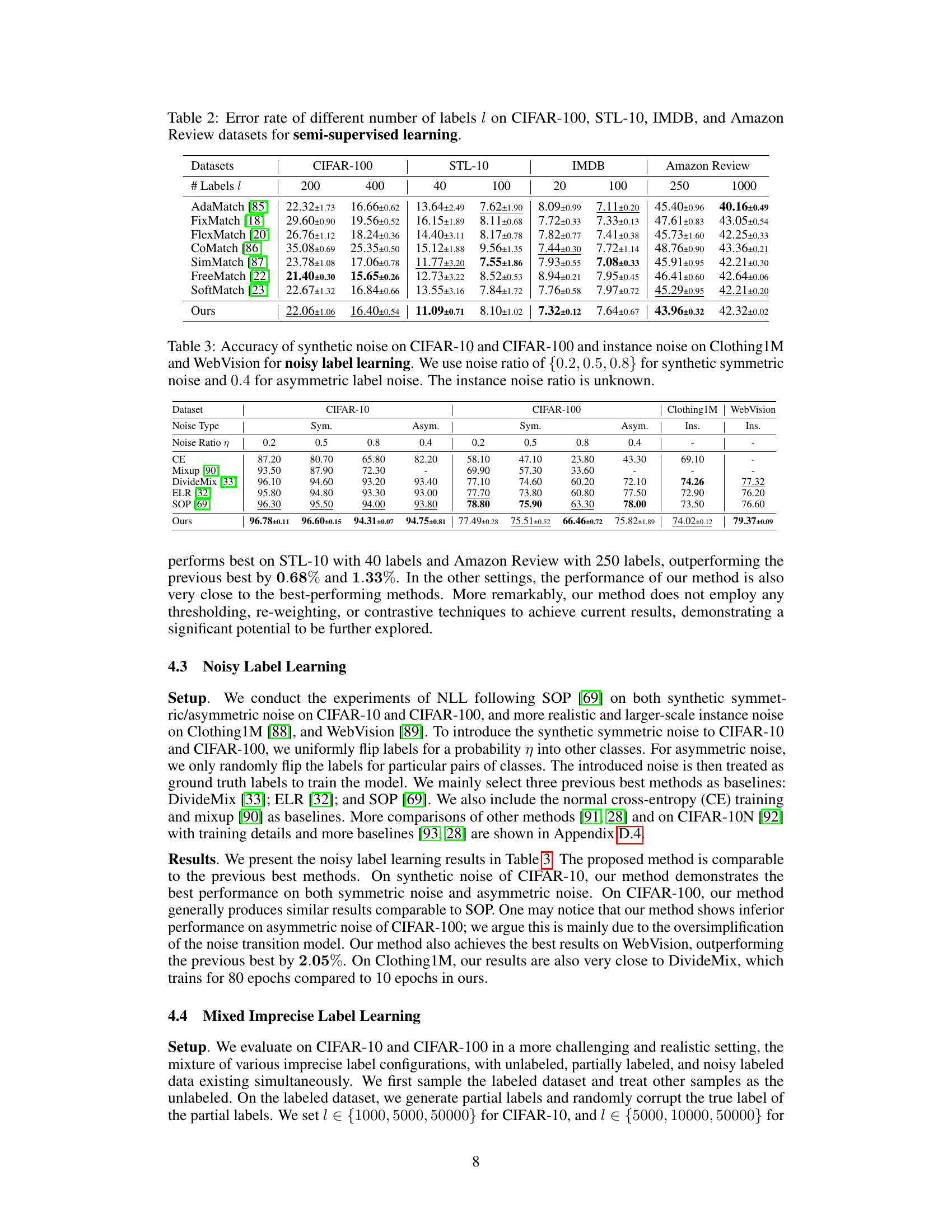

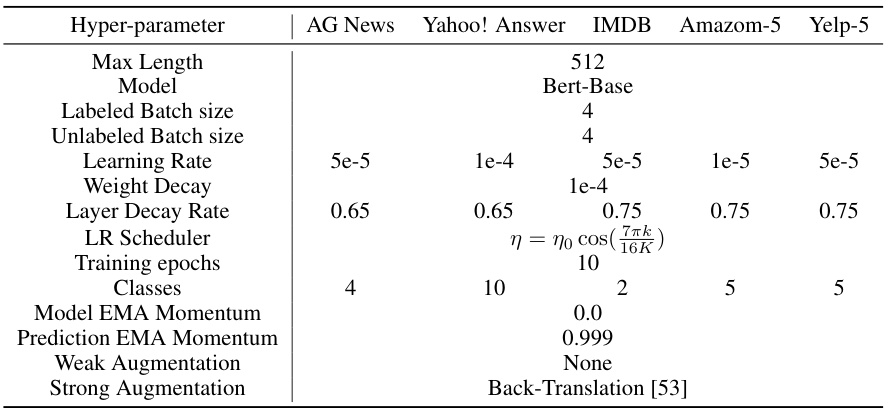

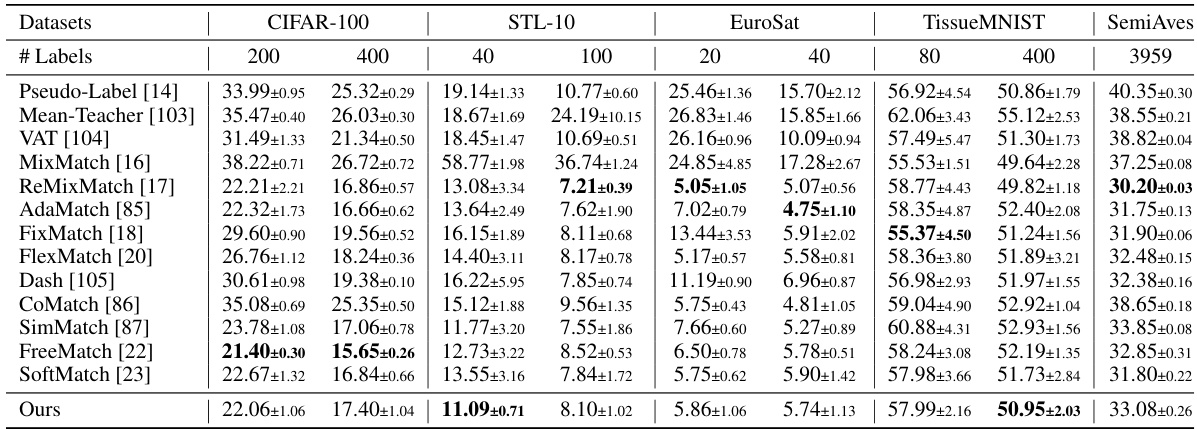

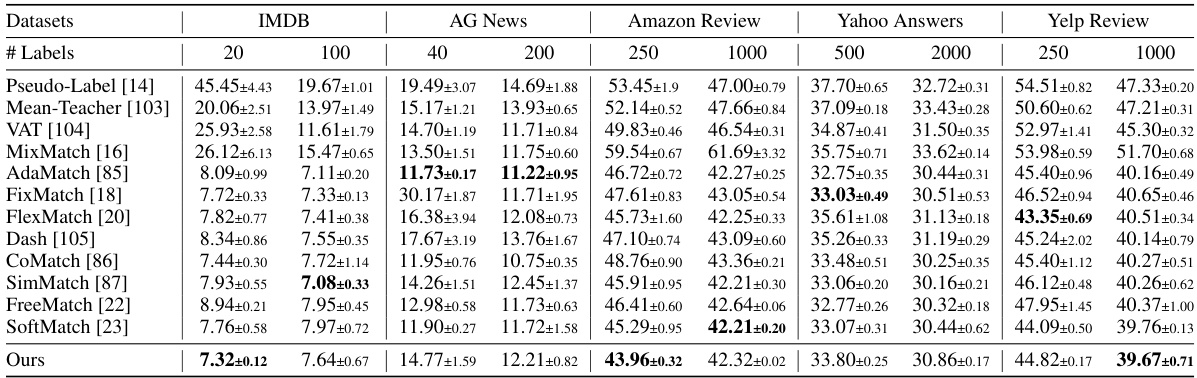

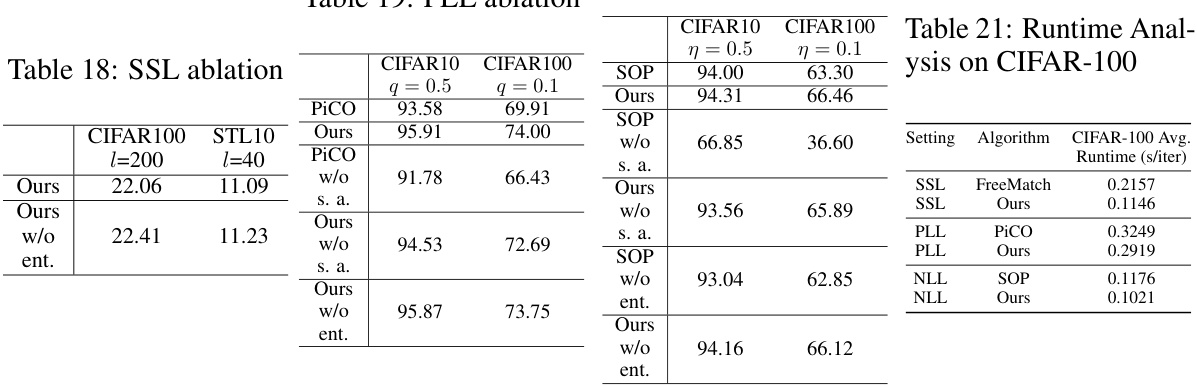

🔼 This table shows the error rate achieved by different semi-supervised learning methods on four datasets (CIFAR-100, STL-10, IMDB, and Amazon Review) with varying numbers of labeled samples (l). Lower error rates indicate better performance. The results are averaged across three independent runs.

read the caption

Table 2: Error rate of different number of labels l on CIFAR-100, STL-10, IMDB, and Amazon Review datasets for semi-supervised learning.

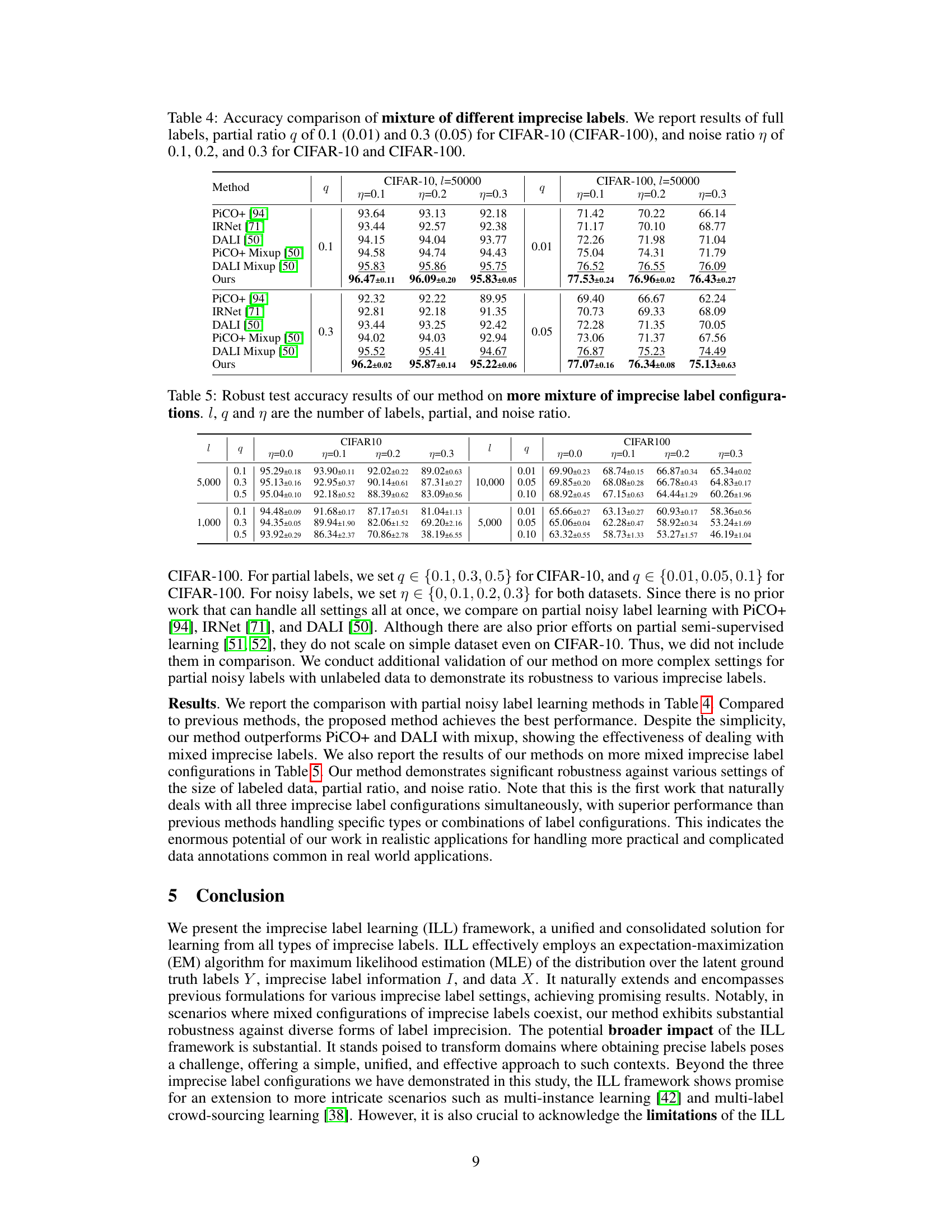

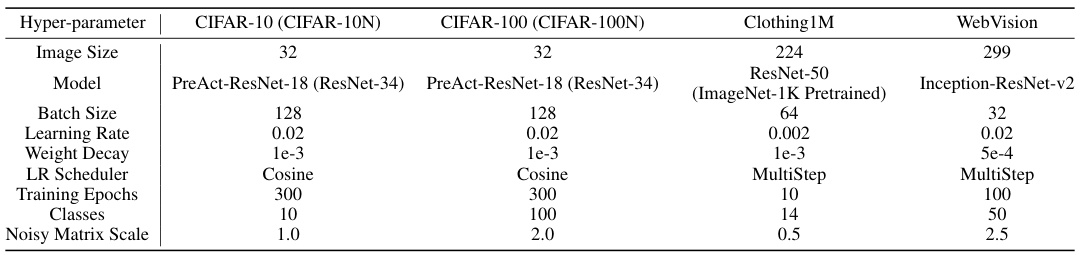

🔼 This table presents the accuracy results of different noisy label learning methods on four datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, Clothing1M, and WebVision. The noise is applied in three ways: synthetic symmetric noise, synthetic asymmetric noise, and instance noise. For synthetic noise, different noise ratios (0.2, 0.5, 0.8 for symmetric and 0.4 for asymmetric) are used. The instance noise ratio is not specified and is inherent to the Clothing1M and WebVision datasets. The table compares the performance of several methods, including the proposed ILL framework, against baseline methods such as CE, Mixup, DivideMix, ELR, and SOP.

read the caption

Table 3: Accuracy of synthetic noise on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 and instance noise on Clothing1M and WebVision for noisy label learning. We use noise ratio of {0.2, 0.5, 0.8} for synthetic symmetric noise and 0.4 for asymmetric label noise. The instance noise ratio is unknown.

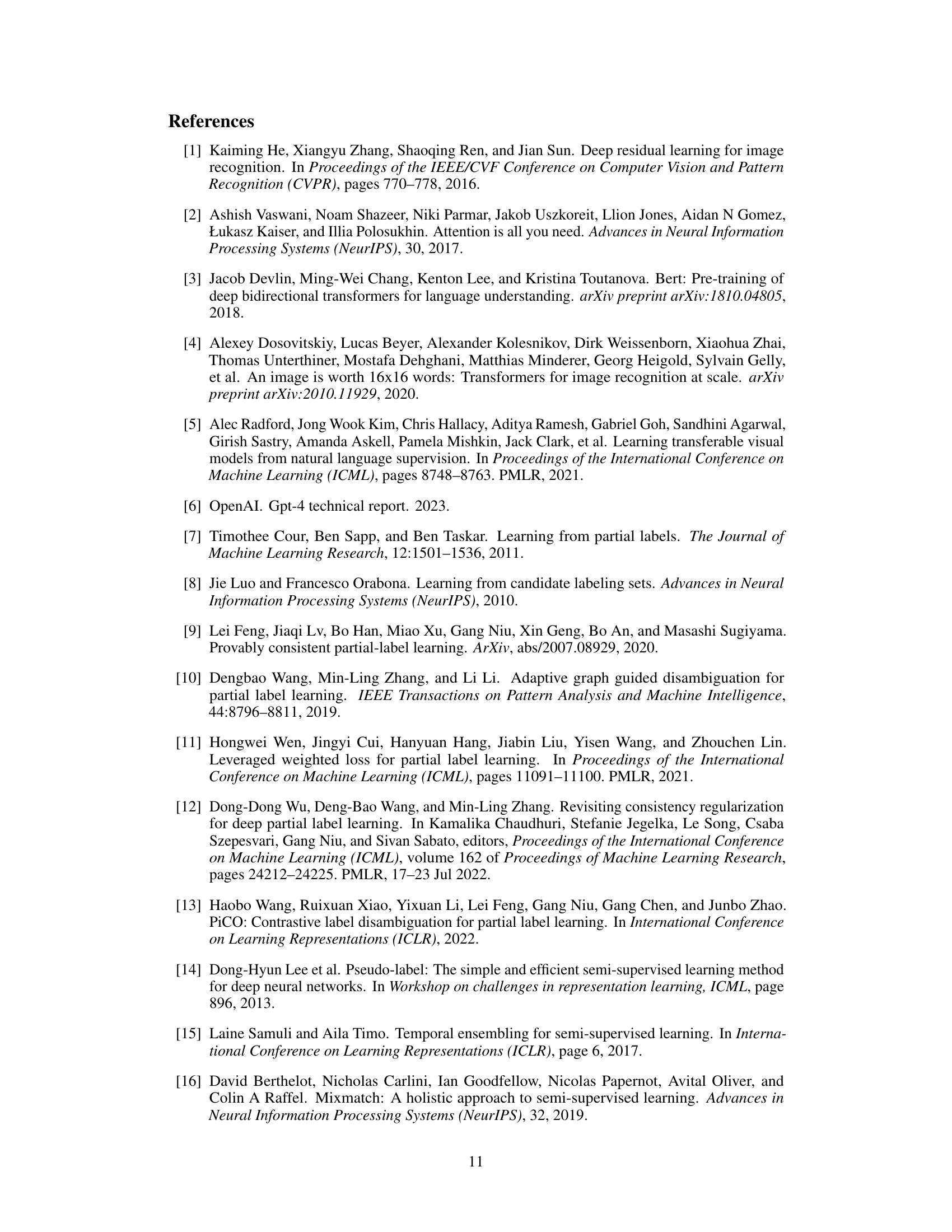

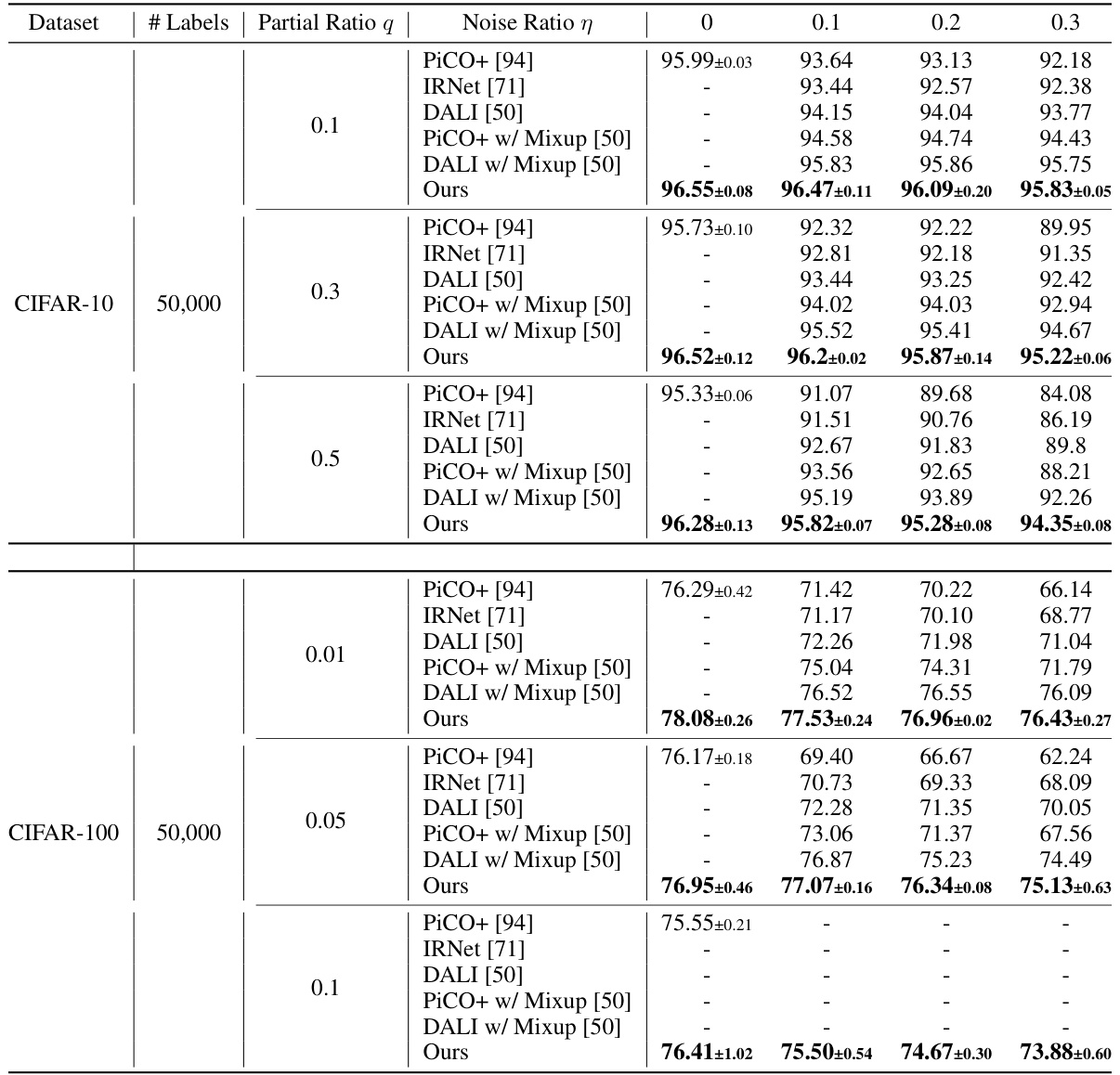

🔼 This table presents the accuracy comparison results for the mixed imprecise label learning setting. It compares the performance of different methods under various combinations of partial labels (with different ratios) and noisy labels (with different noise ratios), using CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The results are categorized by the partial label ratio and noise ratio, allowing for a detailed analysis of method performance across different levels of label imprecision.

read the caption

Table 4: Accuracy comparison of mixture of different imprecise labels. We report results of full labels, partial ratio q of {0.1, 0.3, 0.5} for CIFAR-10 and {0.01, 0.05, 0.1} for CIFAR-100, and noise ratio η of {0.1, 0.2, 0.3} for CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100.

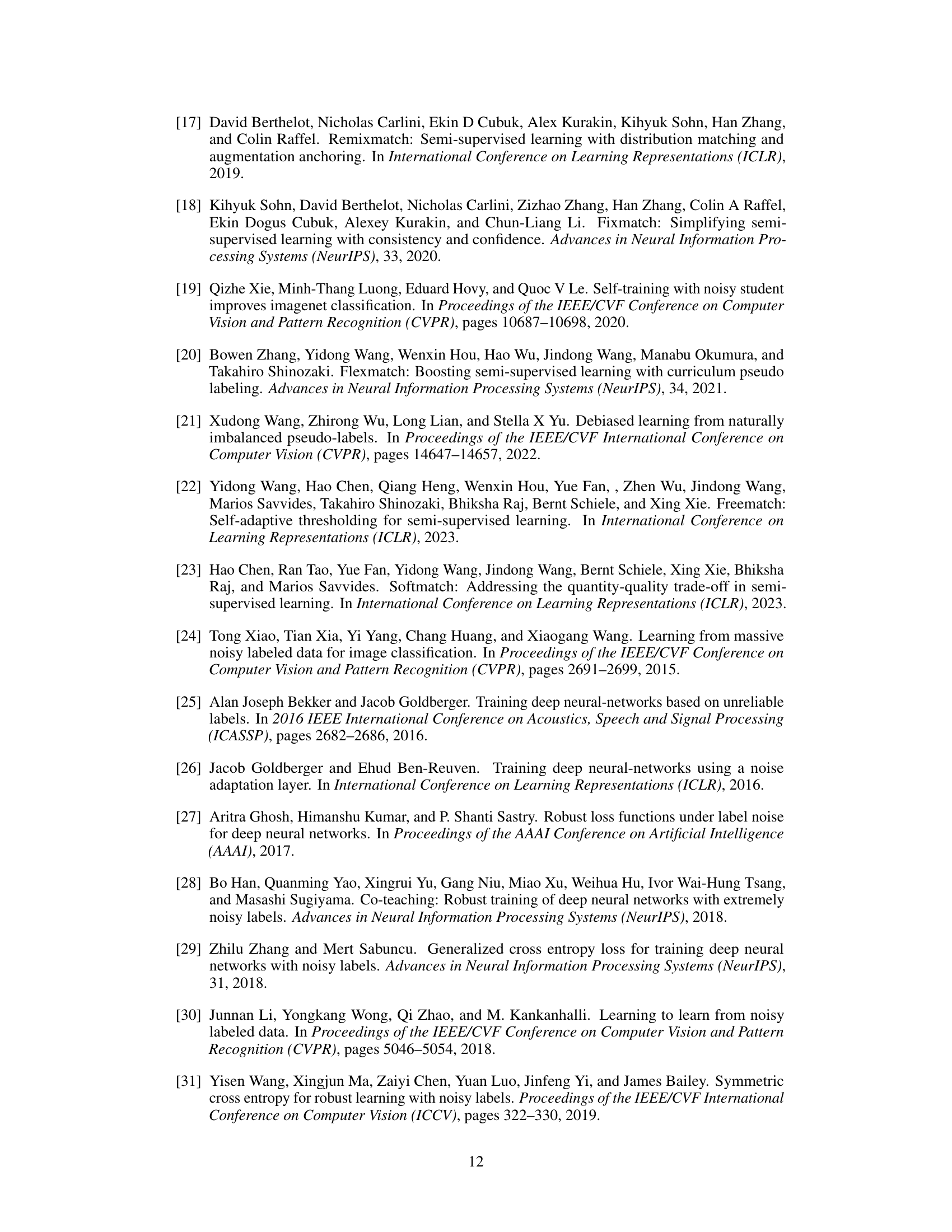

🔼 This table presents the robust test accuracy results of the proposed method on various mixtures of imprecise label configurations. It shows the performance across different numbers of labels (l), partial ratios (q), and noise ratios (η). The results demonstrate the robustness and effectiveness of the method in handling various challenging scenarios with different combinations of imprecise labels.

read the caption

Table 5: Robust test accuracy results of our method on more mixture of imprecise label configurations. l, q and η are the number of labels, partial, and noise ratio.

🔼 This table presents the accuracy results of different partial label learning methods on three datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and CUB-200. The accuracy is evaluated under different partial ratios (q), representing the probability of flipping a negative label to a false positive. The table compares the performance of the proposed ILL method against several existing partial label learning techniques (LWS, PRODEN, CC, MSE, EXP, and PICO). The best and second-best results for each dataset and partial ratio are highlighted.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy of different partial ratio q on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and CUB-200 for partial label learning. The best and the second best results are indicated in bold and underline respectively.

🔼 This table presents the hyperparameters used in the partial label learning experiments described in the paper. It includes details such as image size, model architecture (ResNet-18), batch size, learning rate, weight decay, learning rate scheduler (cosine), number of training epochs, and the number of classes in each dataset (CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, CUB-200). The table provides essential information for reproducibility, allowing researchers to replicate the experimental setup.

read the caption

Table 7: Hyper-parameters for partial label learning used in experiments.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed ILL method against the R-CR method on partial label learning using CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets with different partial ratios. It highlights the competitive performance of ILL, showing it outperforms R-CR on CIFAR-10 and achieves comparable results on CIFAR-100. The results suggest that ILL is a robust and effective approach for partial label learning, even when compared against methods with more complex designs such as R-CR.

read the caption

Table 8: Comparison with R-CR in partial label learning

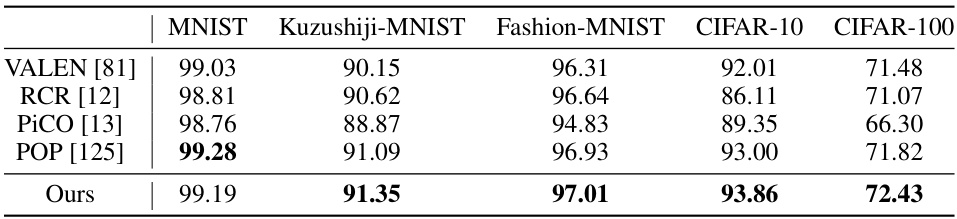

🔼 This table compares the performance of different methods on instance-dependent partial label learning using various datasets: MNIST, Kuzushiji-MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100. The results show the accuracy achieved by each method on each dataset. The methods compared include VALEN [81], RCR [12], PiCO [13], POP [125], and the proposed method (Ours). The table highlights the proposed method’s competitive performance.

read the caption

Table 9: Comparison on instance-dependent partial label learning

🔼 This table presents the accuracy results of different partial label learning methods on three benchmark datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and CUB-200. Each dataset is tested with varying amounts of partial label information (q). The table compares the performance of the proposed method against several state-of-the-art baselines. The best and second-best results for each setting are highlighted in bold and underlined, respectively, showing the superiority of the proposed method across various settings of partial label rates.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy of different partial ratio q on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and CUB-200 for partial label learning. The best and the second best results are indicated in bold and underline respectively.

🔼 This table shows the performance comparison of different partial label learning methods on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and CUB-200 datasets with different partial ratios. The partial ratio represents the probability of flipping negative labels to false positive labels. The results are presented as accuracy, with the best and second-best results highlighted in bold and underlined, respectively. This allows for assessing the effectiveness of various approaches in handling partial label scenarios.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy of different partial ratio q on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and CUB-200 for partial label learning. The best and the second best results are indicated in bold and underline respectively.

🔼 This table shows the error rates achieved by different semi-supervised learning methods on four datasets (CIFAR-100, STL-10, IMDB, and Amazon Review) with varying numbers of labeled samples (l). Lower error rates indicate better performance. The results highlight the performance differences between various methods in low-data regimes and demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method compared to established baselines.

read the caption

Table 2: Error rate of different number of labels l on CIFAR-100, STL-10, IMDB, and Amazon Review datasets for semi-supervised learning.

🔼 This table presents the error rates achieved by various semi-supervised learning methods on four different datasets (CIFAR-100, STL-10, IMDB, and Amazon Reviews). The error rate is shown for different numbers of labeled samples (l) used for training. It allows comparison of the performance of the proposed method against several state-of-the-art baselines across varying dataset sizes and complexities. Lower error rates indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 2: Error rate of different number of labels l on CIFAR-100, STL-10, IMDB, and Amazon Review datasets for semi-supervised learning.

🔼 This table presents the accuracy results of different partial label learning methods on three datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and CUB-200. Each dataset is tested with various partial ratios (q), representing the probability of a negative label being flipped to a false positive. The table compares the performance of several methods against a fully supervised baseline, highlighting the best and second-best performers for each setting.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy of different partial ratio q on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and CUB-200 for partial label learning. The best and the second best results are indicated in bold and underline respectively.

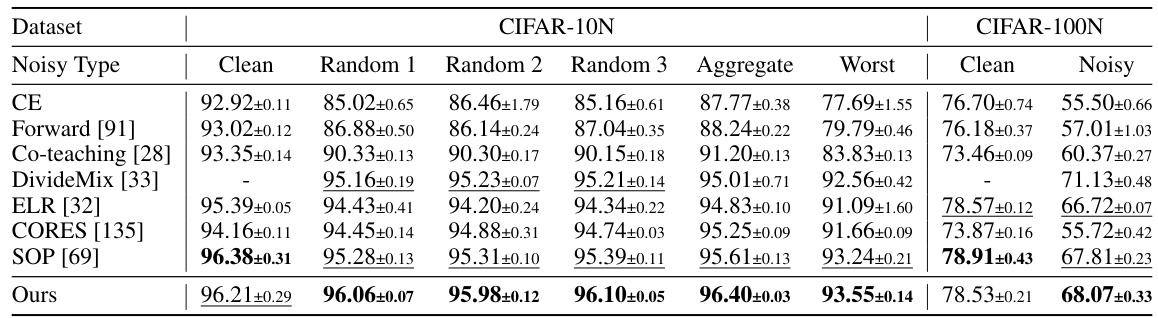

🔼 This table presents the test accuracy results for noisy label learning experiments conducted on CIFAR-10N and CIFAR-100N datasets. Different types of noise are evaluated, including clean data, random noise (three variations), aggregate noise, and worst-case noise. The results are compared across several state-of-the-art methods (CE, Forward, Co-teaching, DivideMix, ELR, CORES, and SOP) and the proposed ILL method. The best and second-best results are highlighted, and all results are averaged over three independent runs using ResNet34 as the backbone network.

read the caption

Table 15: Test accuracy comparison of instance independent label noise on CIFAR-10N and CIFAR-100N for noisy label learning. The best results are indicated in bold, and the second best results are indicated in underline. Our results are averaged over three independent runs with ResNet34 as the backbone.

🔼 This table presents the accuracy results of different methods for noisy label learning on four datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, Clothing1M, and WebVision. The noise types include synthetic symmetric and asymmetric noise (with specified noise ratios) and instance-level noise (with unknown ratio). It compares the performance of the proposed ILL method against several baseline methods, demonstrating its effectiveness in handling noisy labels, across a range of noise settings and datasets.

read the caption

Table 3: Accuracy of synthetic noise on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 and instance noise on Clothing1M and WebVision for noisy label learning. We use noise ratio of {0.2, 0.5, 0.8} for synthetic symmetric noise and 0.4 for asymmetric label noise. The instance noise ratio is unknown.

🔼 This table presents the accuracy results of the proposed ILL framework on datasets CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100, comparing its performance against several state-of-the-art methods. The experiment involves a mixture of imprecise labels: full labels, partial labels (with varying partial ratios), and noisy labels (with varying noise ratios). The table shows the accuracy for different combinations of these label types.

read the caption

Table 4: Accuracy comparison of mixture of different imprecise labels. We report results of full labels, partial ratio q of {0.1, 0.3, 0.5} for CIFAR-10 and {0.01, 0.05, 0.1} for CIFAR-100, and noise ratio η of {0.1, 0.2, 0.3} for CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100.

🔼 This table presents the accuracy results of different partial label learning methods on three benchmark datasets: CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and CUB-200. The accuracy is evaluated under various partial ratios (q), representing the probability of flipping negative labels into false positives. The table compares the proposed method against several existing state-of-the-art methods. The best and second-best performance for each dataset and partial ratio are highlighted.

read the caption

Table 1: Accuracy of different partial ratio q on CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and CUB-200 for partial label learning. The best and the second best results are indicated in bold and underline respectively.

Full paper#