↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world scenarios involve multiple agents using learning algorithms to make sequential decisions. However, it’s challenging to predict how learners will behave in these environments, making it difficult to optimize an agent’s own utility. This paper investigates this challenge, focusing on the interaction between an optimizer and a learner in repeated games. The complexity of predicting learner behavior makes it difficult to design optimal strategies for the optimizer, particularly in general-sum games where players have non-opposing objectives.

This research presents new algorithms that precisely maximize the optimizer’s utility in zero-sum games where the learner employs the Replicator Dynamics, a continuous-time online learning algorithm. For general-sum games, the researchers show that there is no efficient algorithm to calculate optimal strategies unless P=NP. This theoretical result provides crucial insights into the inherent computational limitations involved in optimizing against learners and opens new avenues for future work in algorithm design and approximation techniques in the domain of multi-agent learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in multi-agent systems and online learning. It provides the first known computational lower bound for optimizing rewards against mean-based learners in general-sum games, a significant advancement in understanding the limitations of current approaches. The positive results for zero-sum games offer novel algorithms for optimizers to precisely maximize their utility, while the negative results highlight important computational barriers, guiding future research directions in this actively developing field.

Visual Insights#

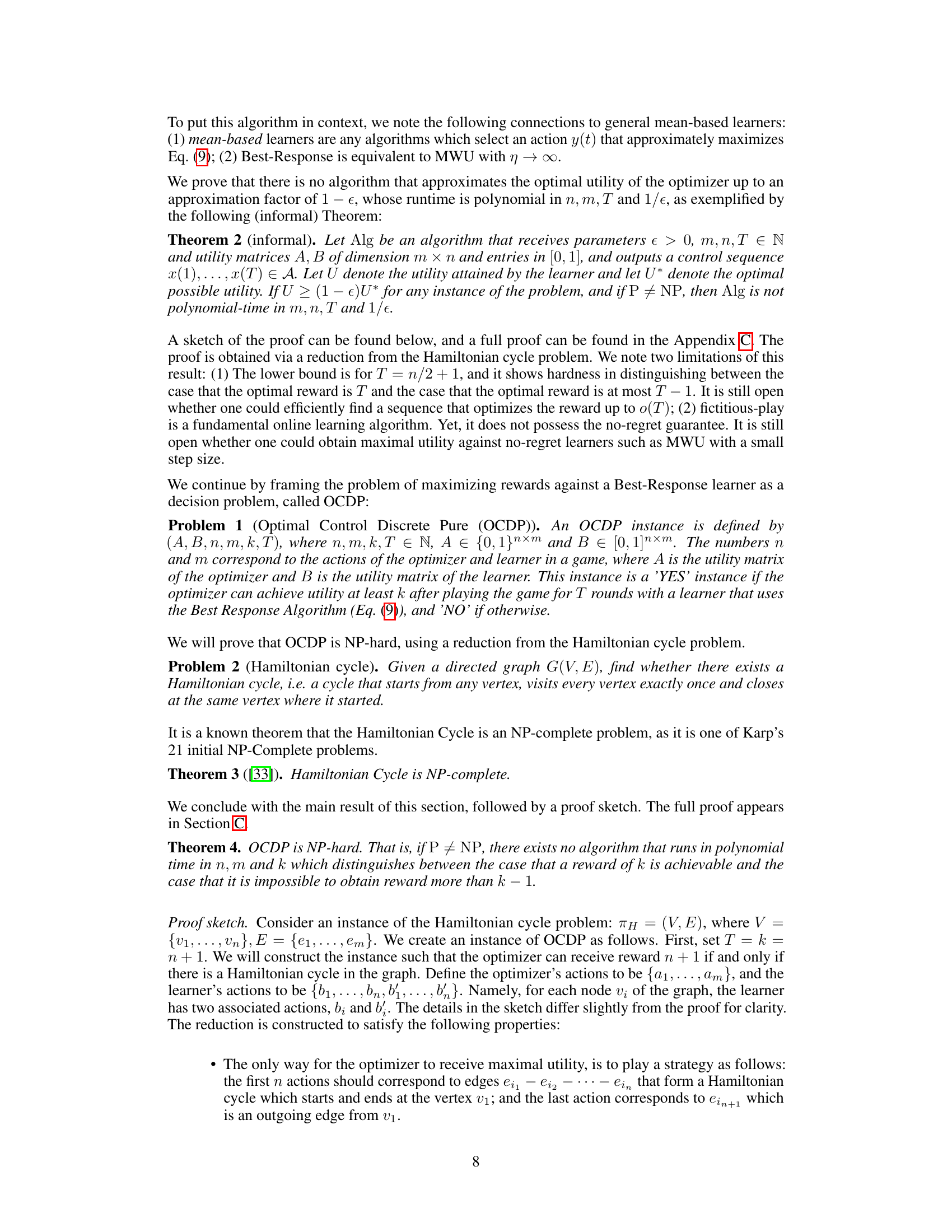

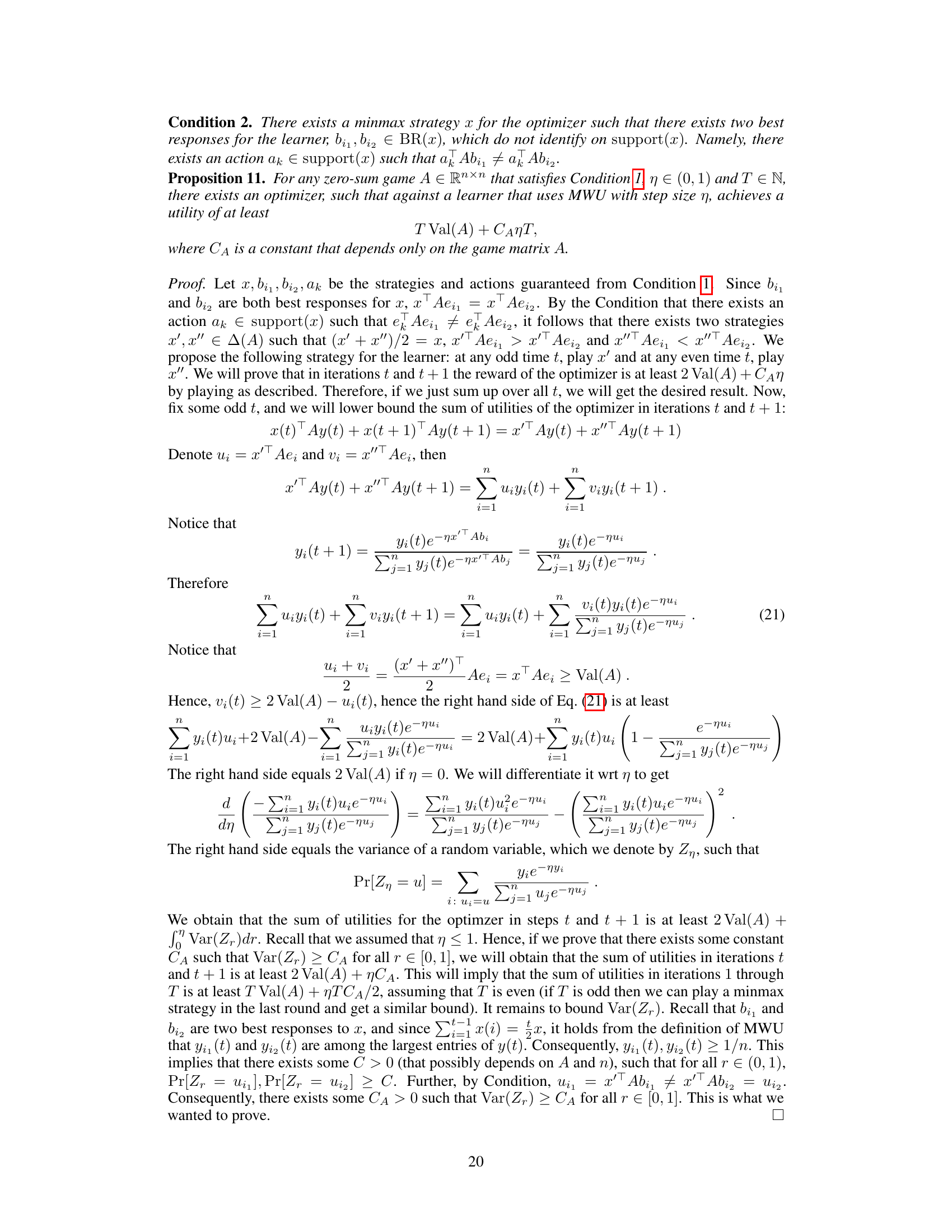

This figure shows a directed graph G with 5 vertices and 7 edges. This graph is used as an example in the paper’s proof of Theorem 4 to demonstrate a reduction from the Hamiltonian Cycle problem to the Optimal Control Discrete Pure (OCDP) problem. The reduction shows that determining whether an optimizer can achieve a certain reward against a best-response learner is computationally hard (NP-hard). The graph’s structure is critical to the reduction, showing how the existence of a Hamiltonian Cycle in the graph maps to the optimizer’s ability to achieve a high reward in the game.

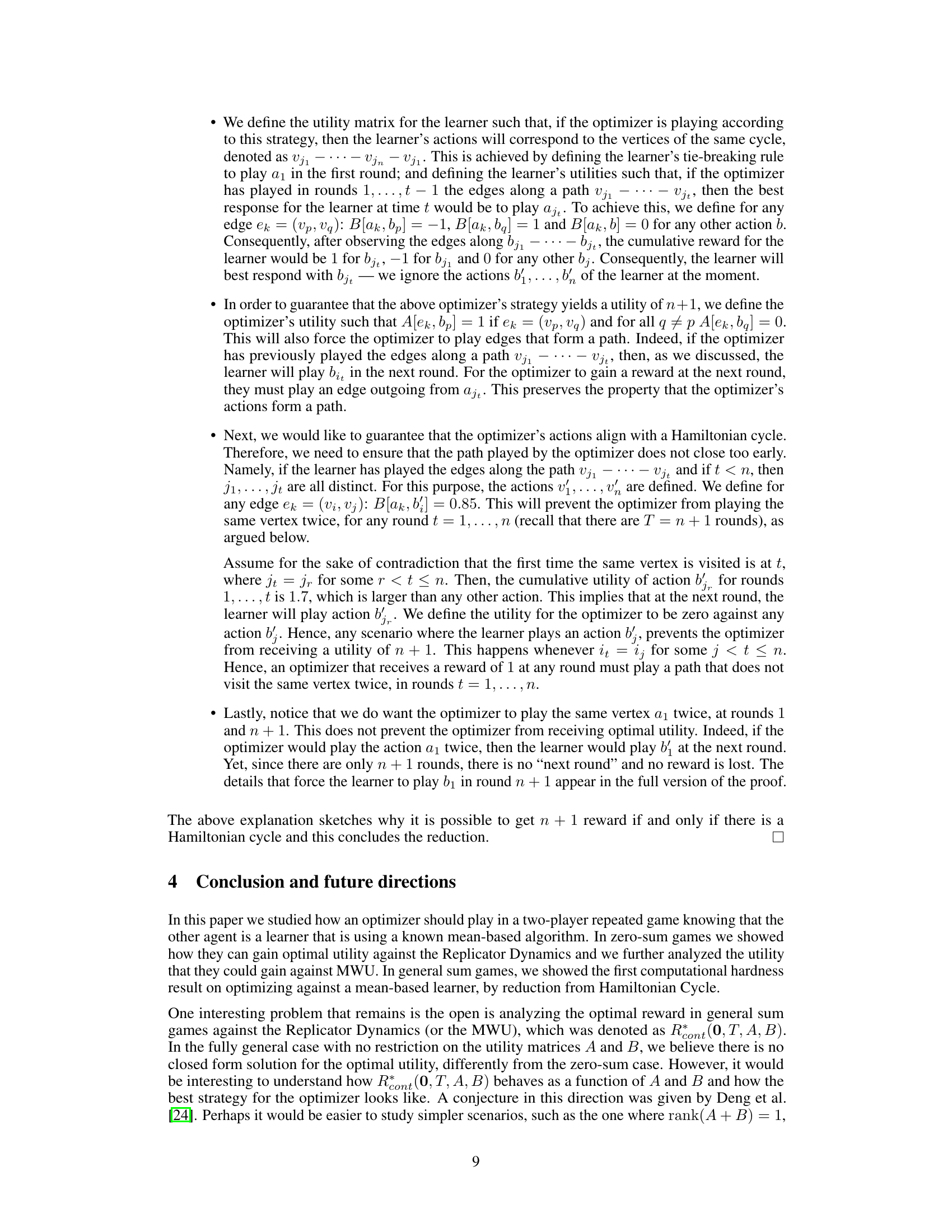

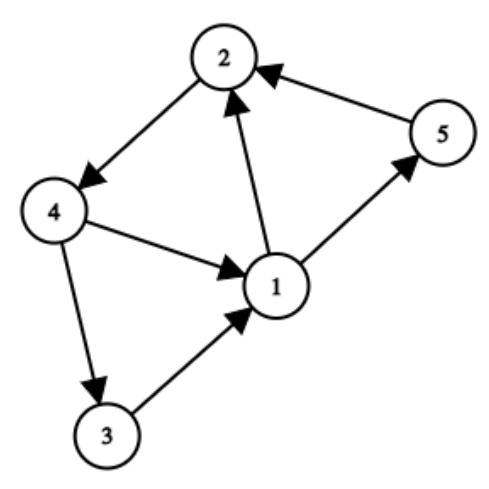

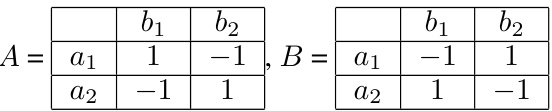

This table presents a zero-sum game example with specific utility matrices A and B for the optimizer and the learner, respectively. It highlights how different min-max strategies for the optimizer can lead to varying numbers of best responses from the learner. The table showcases a specific game where one min-max strategy is particularly effective when the learner utilizes the Multiplicative Weights Update (MWU) algorithm.

In-depth insights#

Multi-agent Utility#

Multi-agent utility presents a complex challenge in AI, focusing on how the actions of multiple agents impact each other’s rewards. Effective strategies must consider not only maximizing an individual agent’s utility but also anticipating and influencing the actions of other agents. This requires sophisticated models of other agents’ behaviors, often using techniques from game theory and online learning. The interaction between learning algorithms and optimization becomes critical in repeated game settings, where the ability to predict and adapt to the evolving behaviors of other agents is essential for achieving higher utility. Zero-sum games, where one agent’s gain is another’s loss, offer a simplified but important framework for initial analysis. However, general-sum games encompass a much wider range of scenarios, demanding more complex analysis and often highlighting the computational challenges of finding optimal strategies. Approximation algorithms and computational lower bounds play significant roles in determining the feasibility and limits of effectively optimizing utility in multi-agent environments.

Learner Prediction#

Learner prediction, in the context of multi-agent reinforcement learning, focuses on anticipating the actions of other learning agents. Accurate prediction is crucial for an agent to optimize its own strategy and achieve its goals, especially in competitive scenarios. This involves modeling the learning algorithm of other agents, which can be challenging due to the inherent complexity and variability of these algorithms. Different approaches exist, ranging from simple heuristics (e.g., assuming a best-response strategy) to complex models that attempt to learn the opponent’s policy. The accuracy of learner prediction heavily depends on the nature of the game, the characteristics of the learning algorithms involved, and the availability of data. In zero-sum games, perfect prediction may be possible under certain conditions, whereas in general-sum games, it’s often more challenging due to less predictable interactions. The computational cost is another factor to consider, as accurate learner prediction can be computationally expensive, especially for complex models and large state spaces. Research in learner prediction involves developing efficient and accurate prediction models that can improve the decision-making process of agents in multi-agent learning systems. Ultimately, the value of learner prediction hinges on its ability to improve overall agent performance and contribute to more robust, adaptable, and intelligent agents in dynamic environments.

Zero-Sum Games#

In zero-sum games, the optimizer’s goal is to maximize its own utility, which is inherently tied to the learner’s loss because one player’s gain is the other’s loss. The analysis explores algorithms for the optimizer to capitalize on the learner’s suboptimal play, which deviates from a minimax strategy. A key finding presents an algorithm that exactly maximizes the optimizer’s utility against a learner using Replicator Dynamics (continuous-time MWU), offering a concrete positive result. However, the paper also demonstrates that for general-sum games, finding a computationally efficient optimal strategy for the optimizer is likely intractable unless P=NP, highlighting the increased difficulty of anticipating learner behavior in non-zero-sum scenarios.

Computational Limits#

The heading ‘Computational Limits’ in a research paper would likely explore the inherent boundaries of computational tractability for the problems discussed. This section would delve into the complexity classes of algorithms used, potentially highlighting cases where finding optimal solutions is NP-hard or even undecidable. A key aspect would be demonstrating that certain problems, while theoretically solvable, become practically intractable due to exponential time complexity. The authors would likely present formal proofs or reductions to support their claims about intractability. The discussion may also address the impact of these limits on practical applications, acknowledging that approximate or heuristic solutions might be necessary in computationally challenging scenarios. Furthermore, the analysis may involve trade-offs between computational cost and solution quality, suggesting methods to find near-optimal solutions within reasonable time constraints. Approximation algorithms or heuristic techniques employed to overcome these limitations would be another focus of this section. Ultimately, this section aims to provide a realistic assessment of the feasibility and scalability of proposed methods, acknowledging inherent computational barriers.

Future Directions#

The paper’s “Future Directions” section would ideally explore several key areas. Extending the optimizer’s strategies to more complex multi-agent settings beyond two-player games is crucial. This involves analyzing how the optimizer’s performance changes with the number of agents and their learning algorithms. Further, developing computationally efficient algorithms for general-sum games is needed to make the theoretical results practically applicable. The current NP-hardness result highlights the difficulty of finding exact solutions; approximation algorithms or heuristics with performance guarantees are desirable research directions. Investigating the impact of different learner algorithms (beyond MWU and Replicator Dynamics) on the optimizer’s performance and the existence of computationally tractable optimal strategies is vital. Finally, a rigorous analysis of the robustness of the proposed strategies to various sources of noise and uncertainty in real-world scenarios, such as imperfect information or noisy observations, will be critical for practical implementation.

More visual insights#

More on tables

This table presents a zero-sum game example used to illustrate a point in the paper. The example highlights a situation where the optimizer can gain significantly more utility by leveraging the suboptimality of the learner’s strategy (using MWU), as compared to the theoretical minimum utility guaranteed by minmax strategies.

This table presents a zero-sum game matrix A, where the rows represent actions for player 1 (optimizer) and columns represent actions for player 2 (learner). The entries show the utility for player 1. The game demonstrates the concept of multiple min-max strategies for the optimizer, but some provide better rewards against the Multiplicative Weights Update (MWU) algorithm than others. This is used to illustrate a point in the paper.

This table shows a zero-sum game matrix A and its corresponding matrix B, where the optimizer’s goal is to maximize its utility and the learner uses a learning algorithm. The table illustrates an example where multiple min-max strategies exist for the optimizer, but only one of them provides optimal rewards when used against a learner employing the Multiplicative Weights Update (MWU) algorithm. This highlights the complexity of optimizing against adaptive learners in zero-sum games. The example showcases how the discrete-time optimizer’s performance can differ from that of the continuous-time optimizer against a learner using MWU.

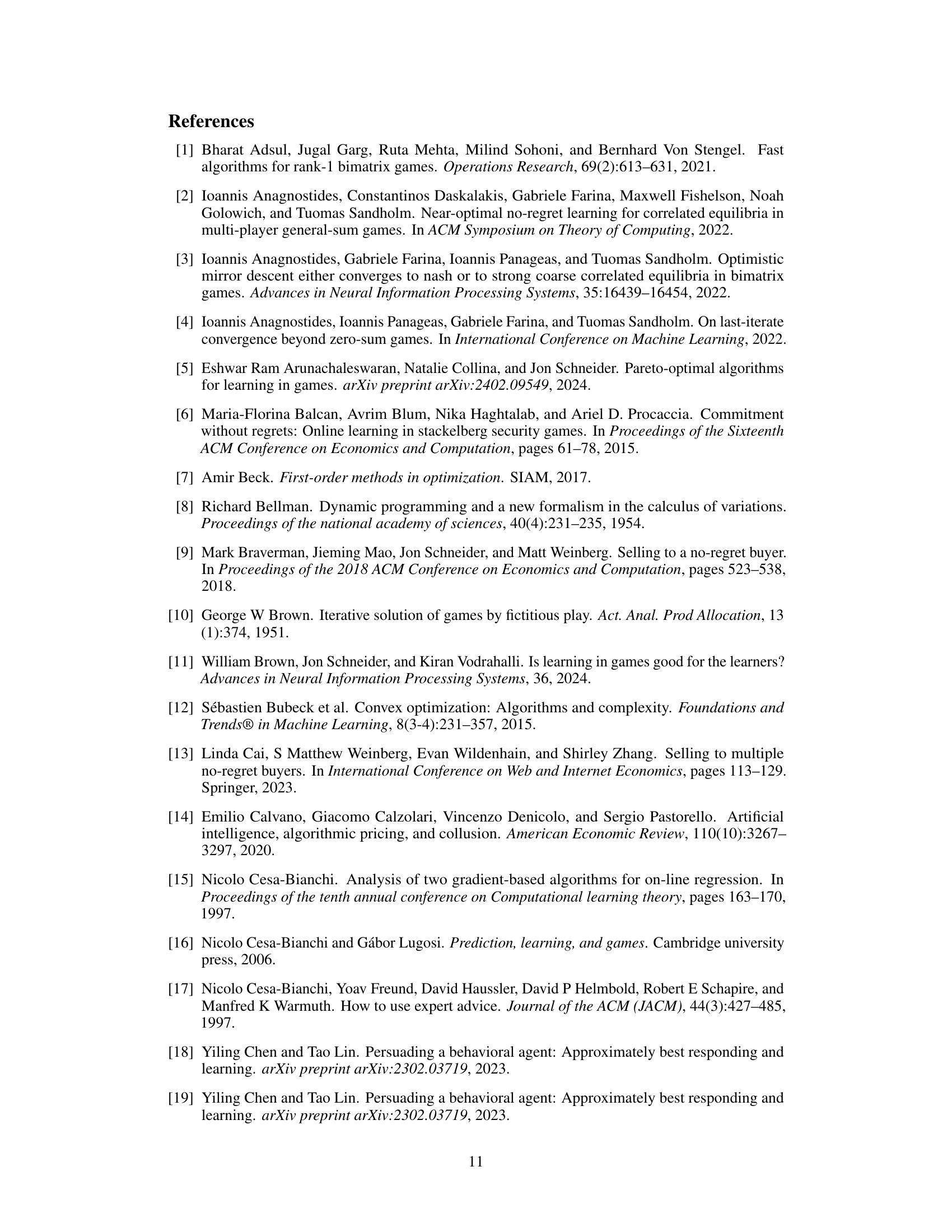

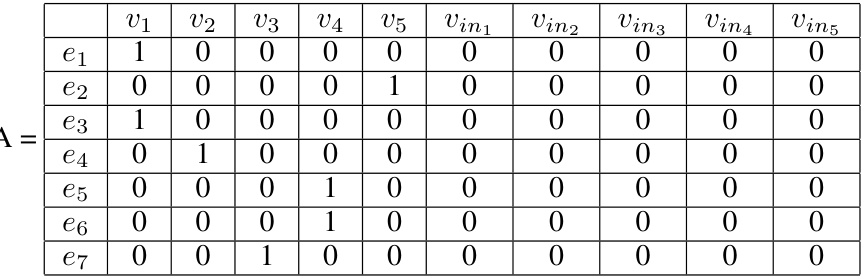

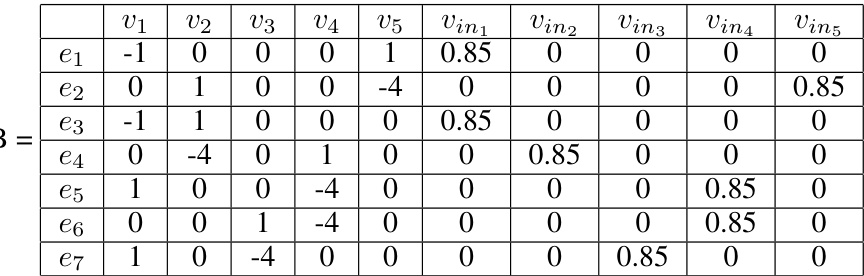

This table shows the utility matrices A and B used in an example illustrating the reduction from the Hamiltonian cycle problem to the Optimal Control Discrete Pure (OCDP) problem. Matrix A represents the optimizer’s utilities, while matrix B represents the learner’s utilities. The rows correspond to the optimizer’s actions (edges in the graph), and the columns correspond to the learner’s actions (vertices in the graph and their incoming edges). The values indicate the utilities obtained by each player given a specific combination of actions. This example demonstrates how the construction of the matrices encodes the constraints of finding a Hamiltonian cycle in the graph to construct a YES/NO instance of the OCDP problem.

This table shows the utility matrix B for the learner. Each cell (aᵢ,bⱼ) represents the utility the learner receives when the optimizer plays action aᵢ and the learner plays action bⱼ. Note the different values depending on whether the action is an incoming or outgoing edge in the graph used for the Hamiltonian Cycle problem reduction. The values reflect the design to incentivize the learner to follow a Hamiltonian cycle.

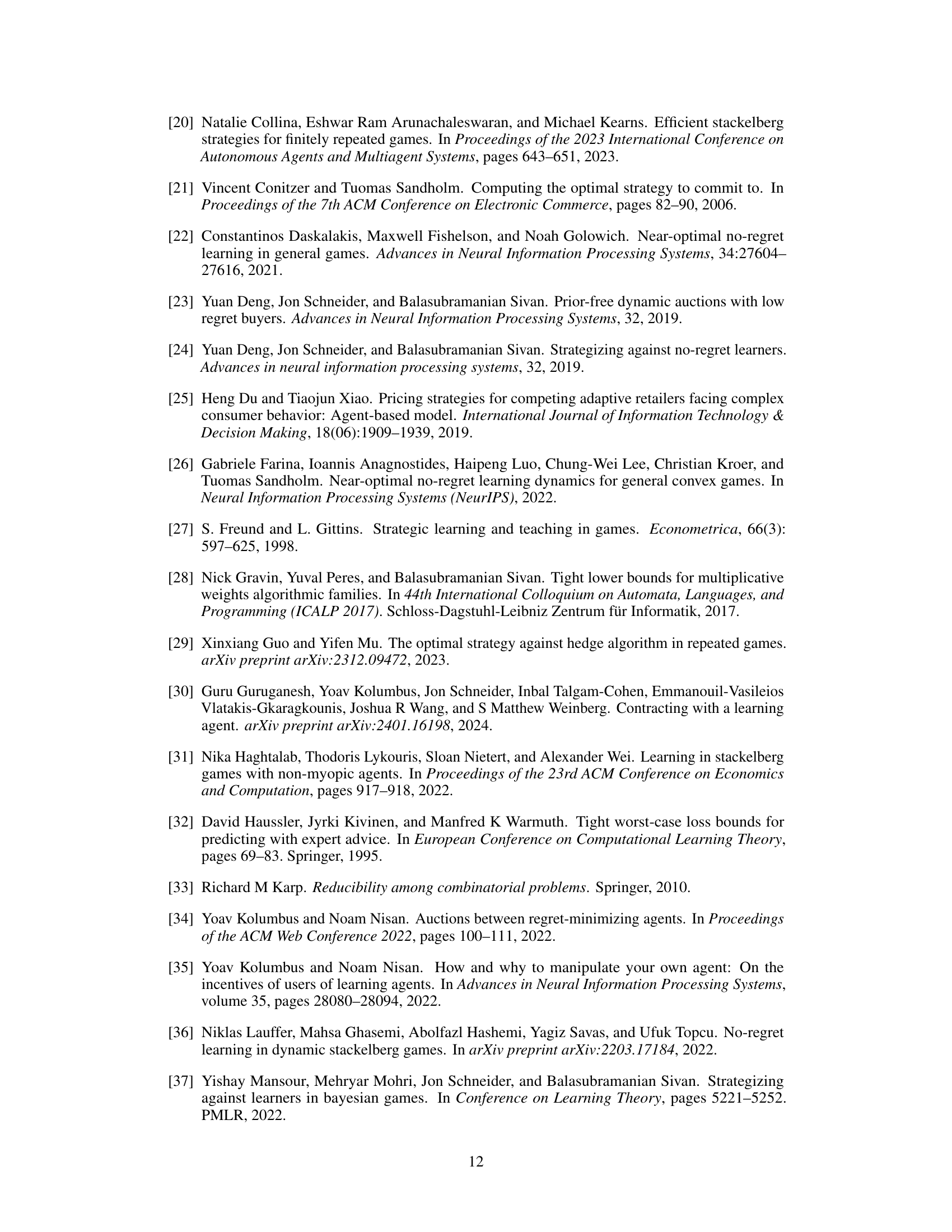

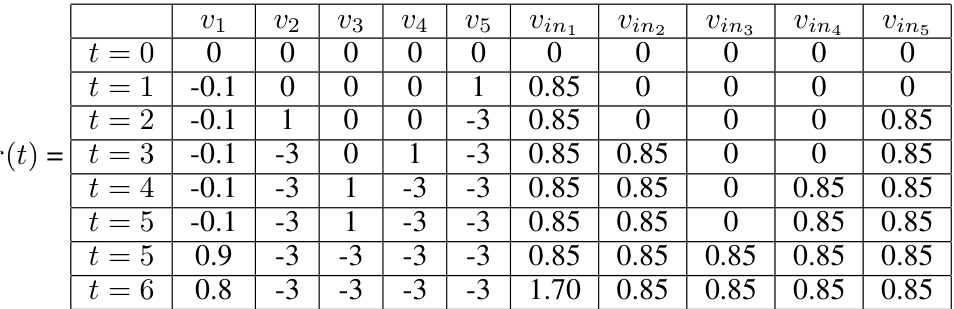

This table shows the evolution of the learner’s rewards (h(t)) for each action across multiple rounds (t) of a game. Each row represents a round, and each column shows the cumulative rewards for a specific action. The rewards are updated after each round, reflecting the influence of the optimizer’s actions. This data is used in the proof to demonstrate that the optimal strategy for the optimizer leads to a specific sequence of learner actions and a final cumulative reward of n+1. This is part of the reduction from Hamiltonian Cycle problem to Optimal Control Discrete Pure problem.

Full paper#