↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional priority queues struggle with guaranteeing optimal time complexity for all operations. This limitation motivates the exploration of learning-augmented data structures. The paper investigates the challenges of integrating predictions into priority queues to improve worst-case performance.

The researchers propose and analyze three different prediction models applied to a skip-list based priority queue. They demonstrate that leveraging predictions significantly enhances performance for various priority queue operations, including insertion, deletion, and finding the minimum element. They also provide lower bounds that prove the optimality of their proposed algorithm in two of the three prediction models. The use of skip lists allows for efficient implementation and optimality in the worst-case scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents novel learning-augmented priority queue implementations that leverage predictions to significantly improve performance. This work is relevant to researchers working on algorithm design, data structures, and machine learning, opening up new avenues of research by demonstrating how machine learning can be combined with algorithm design to enhance performance.

Visual Insights#

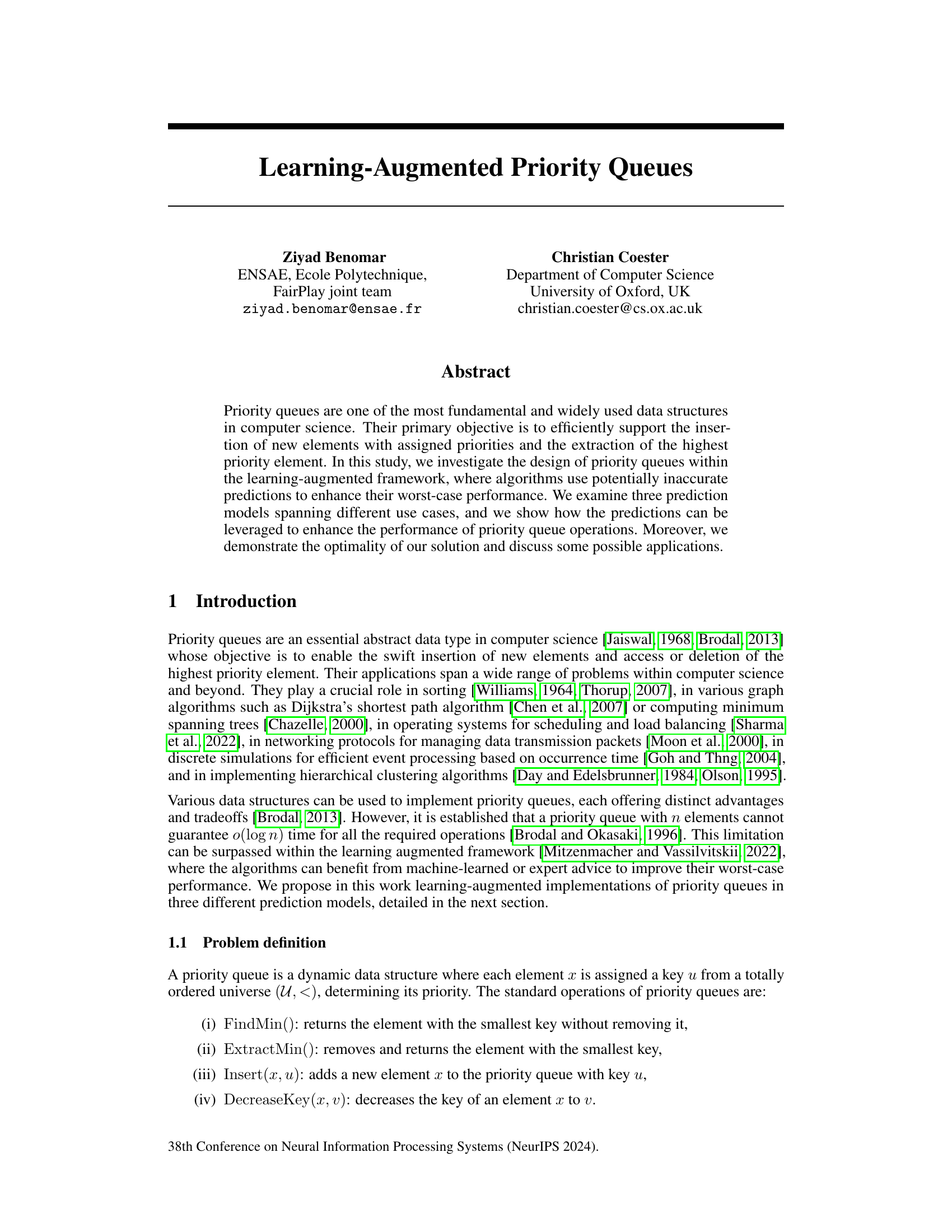

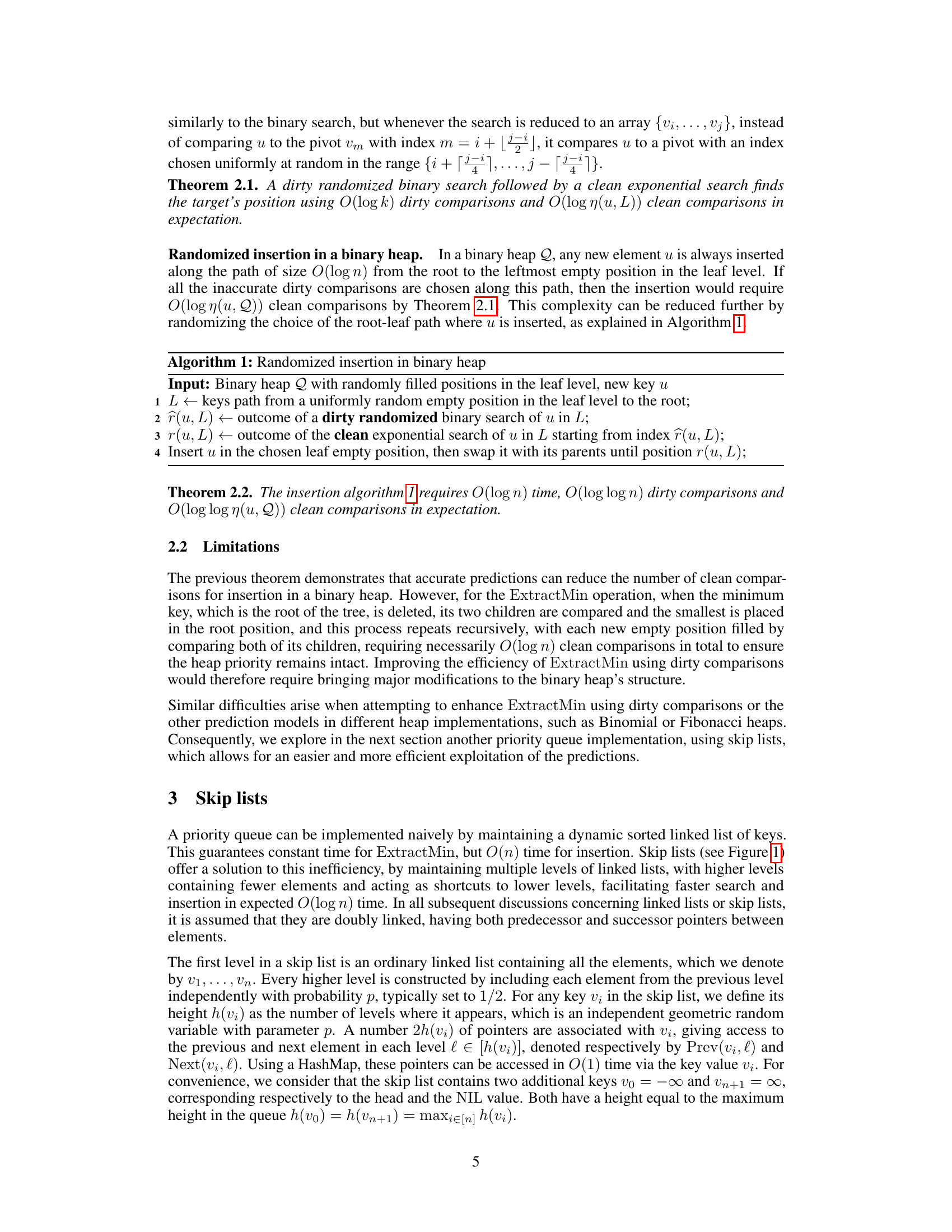

This figure shows a skip list data structure, which is a probabilistic data structure used to implement priority queues. It consists of multiple levels of linked lists, with higher levels containing fewer elements and acting as shortcuts to lower levels. This allows for faster search and insertion operations compared to a simple linked list. The figure illustrates the structure with keys v1 through v9, showing how they are organized across different levels. The HEAD and NIL nodes represent the beginning and end of the skip list, respectively.

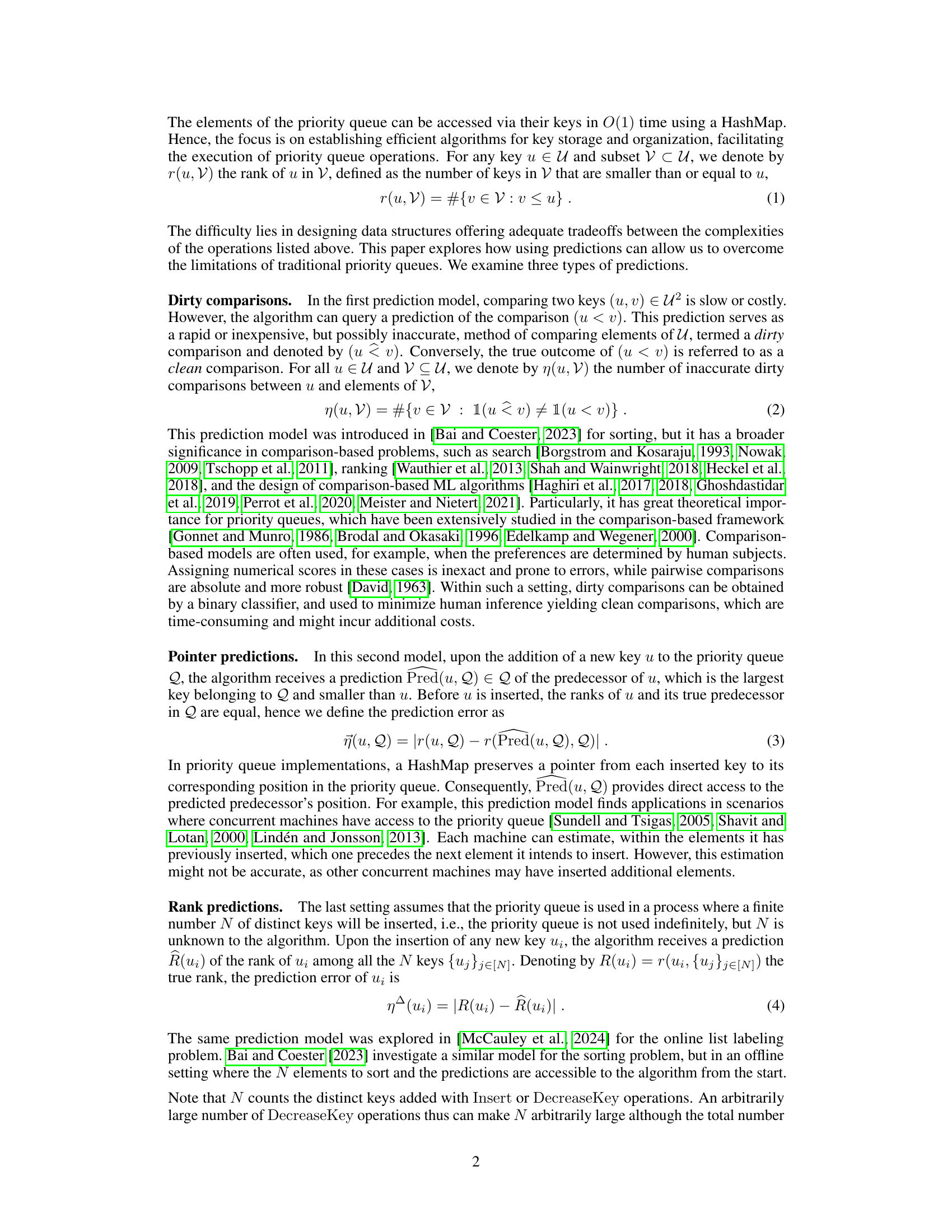

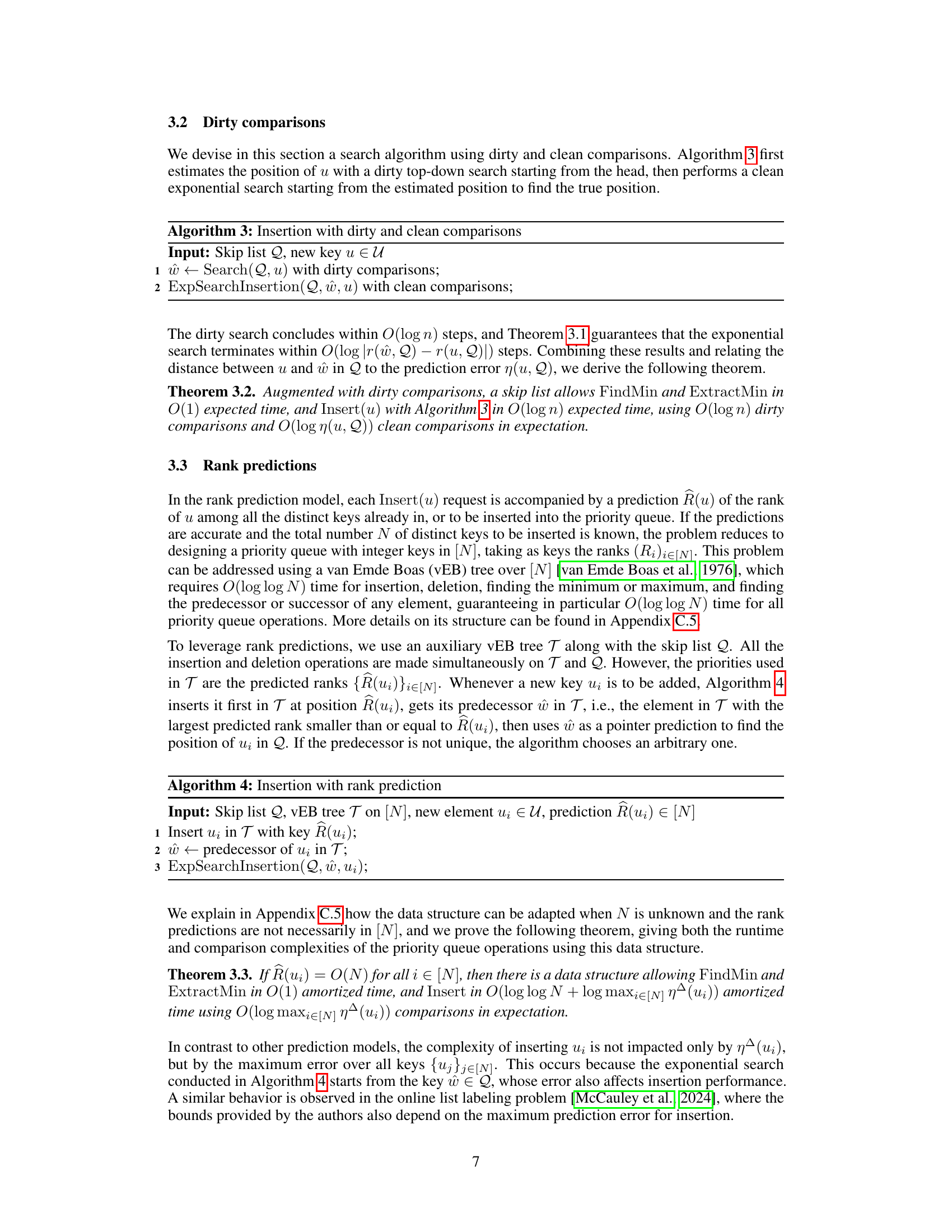

The table compares the time complexity of several priority queue implementations. The rows represent different data structures for implementing priority queues: Binary Heap, Fibonacci Heap, Skip List, and three versions of the Learning-Augmented Priority Queue (LAPQ) using different prediction models (dirty comparisons, pointer predictions, and rank predictions). The columns indicate the time complexity of the priority queue operations: ExtractMin, Insert, and DecreaseKey. The complexities are expressed using Big O notation and represent the average-case performance of the algorithms.

In-depth insights#

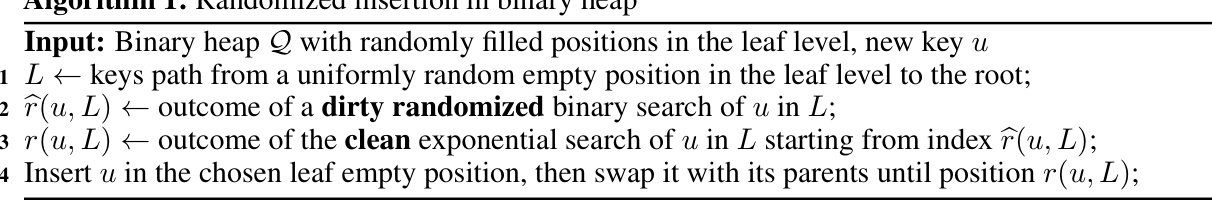

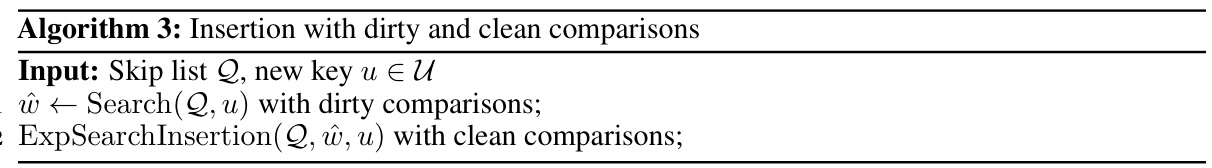

Learning-Augmented PQ#

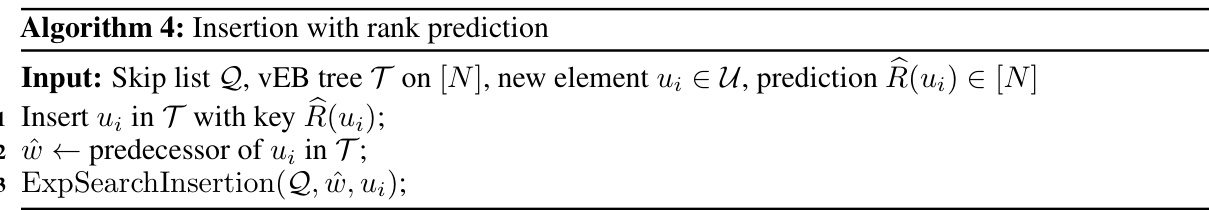

Learning-Augmented Priority Queues (LAPQ) represent a significant advancement in the field of data structures. By integrating machine learning predictions into traditional priority queue algorithms, LAPQs aim to improve worst-case performance and overcome inherent limitations. The core idea involves using potentially inaccurate predictions to guide algorithmic choices, thus enhancing efficiency. Three prediction models are explored: dirty comparisons (inexpensive but possibly inaccurate key comparisons), pointer predictions (predicting the predecessor of a newly inserted key), and rank predictions (predicting the rank of a new key among all keys). The paper demonstrates how these predictions can be leveraged to reduce the complexity of priority queue operations in various scenarios. The use of skip lists as the underlying data structure proves particularly effective in this context. Optimality of the proposed solution is also demonstrated, and the paper explores several applications, including accelerated Dijkstra’s algorithm and improved sorting algorithms, highlighting the practical value and versatility of LAPQs. Experimental evaluation, comparing LAPQ against standard implementations, confirms significant performance improvements, particularly in scenarios with high-quality predictions. Overall, the research introduces a novel and valuable approach to enhancing priority queues that holds promising applications across computer science.

Prediction Model Effects#

A thoughtful exploration of ‘Prediction Model Effects’ in a research paper would delve into how different prediction models impact the overall performance and efficiency of a system. It would be crucial to analyze the accuracy and cost of predictions generated by each model, considering trade-offs between these factors. The analysis should also examine how prediction errors propagate through the system, influencing the reliability and stability of the results. A strong analysis would incorporate the use of metrics to quantify the impact of each model, comparing their performance across various criteria (e.g., runtime, accuracy, resource usage). Moreover, it would be insightful to investigate the generalizability of each model, exploring their robustness to variations in input data or system parameters. Finally, a key aspect would involve discussing the practical implications of the prediction models, such as their scalability and feasibility for real-world applications.

Skip List Optimality#

Analyzing skip list optimality requires considering its probabilistic nature and the trade-off between space and time efficiency. Optimality proofs often center on demonstrating that the expected time complexity of operations (insertion, deletion, search) matches the theoretical lower bound for such operations in comparison-based data structures. However, the actual performance depends on the skip list’s height, which is influenced by the randomness of level creation. Therefore, while average-case optimality can often be proven, the worst-case performance might not be optimal. Additionally, the use of heuristics or different probability values for level generation can influence the space requirements and expected time. A truly optimal skip list design would need to take into account the specific application’s needs, hardware constraints and the desired tradeoff between space utilization and expected performance. Moreover, external factors like the quality of the predictions in a learning-augmented scenario also directly impact skip list performance; a deeper analysis accounting for these must be incorporated into the overall assessment of its optimality.

Algorithm Applications#

The section on “Algorithm Applications” would ideally delve into the practical uses of the learning-augmented priority queue (LAPQ) presented in the paper. It should highlight how the LAPQ’s improved performance in various prediction models (dirty comparisons, pointer predictions, rank predictions) translates to real-world advantages. Specific applications, such as accelerating Dijkstra’s shortest path algorithm or enhancing comparison-based sorting algorithms, need detailed explanation. The discussion must go beyond simply stating the applications; it should quantify the performance gains of the LAPQ over traditional methods in these contexts using experimental data or theoretical analysis. For example, it should show concrete examples and benchmarks illustrating the improvements achieved. Furthermore, the section should explore novel applications of the LAPQ, possibly in areas not explicitly mentioned in the introduction. This might involve adapting the algorithm to address new types of problems or demonstrating how the predictions’ accuracy or types impact the LAPQ’s suitability for different tasks. Finally, the section must address limitations and trade-offs. Are there situations where the LAPQ doesn’t offer significant advantages? Does the improved efficiency come at the cost of increased complexity or resource consumption? Addressing these points thoroughly will make the “Algorithm Applications” section impactful and convincing.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on learning-augmented priority queues could explore several promising avenues. Extending the prediction models beyond the three examined (dirty comparisons, pointer predictions, rank predictions) is crucial. Investigating more sophisticated models, such as those incorporating temporal dependencies or utilizing deep learning architectures, could significantly enhance performance. Analyzing the impact of prediction accuracy on overall efficiency is another important area. A deeper understanding of the trade-offs between prediction cost and improvement in worst-case performance is needed to optimize practical implementations. Developing adaptive algorithms that dynamically adjust their reliance on predictions based on observed accuracy would improve robustness. Applying these queues to diverse applications beyond sorting and Dijkstra’s algorithm (such as event-driven simulations, real-time scheduling, or hierarchical clustering) should also be explored, focusing on areas where the inherent uncertainty in data makes leveraging predictions particularly beneficial. Finally, rigorous theoretical analysis is needed to establish tighter bounds on the complexity of these algorithms and investigate their optimality under various prediction models and accuracy levels.

More visual insights#

More on figures

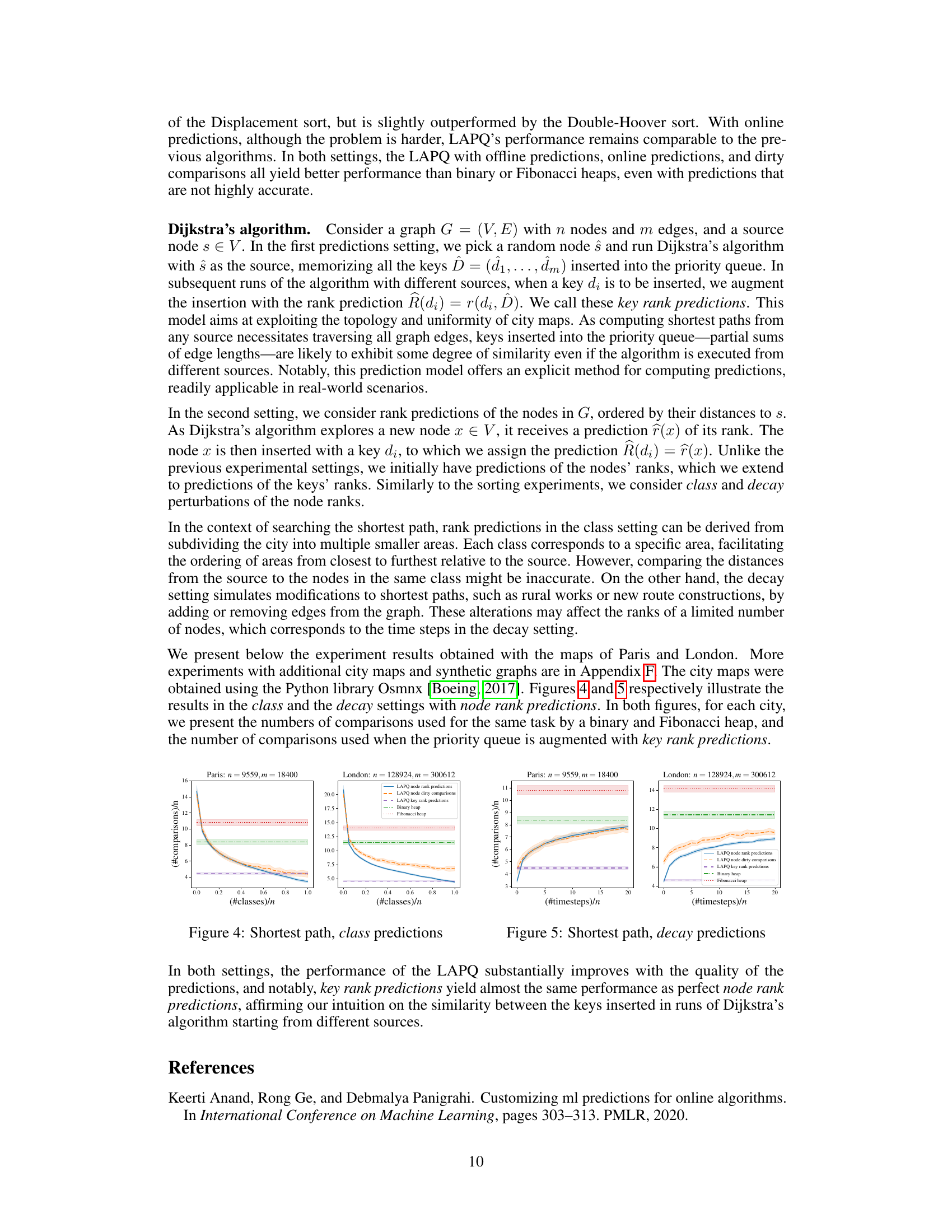

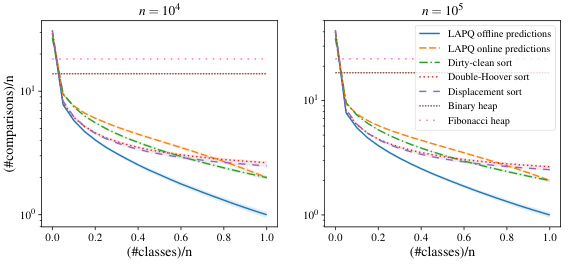

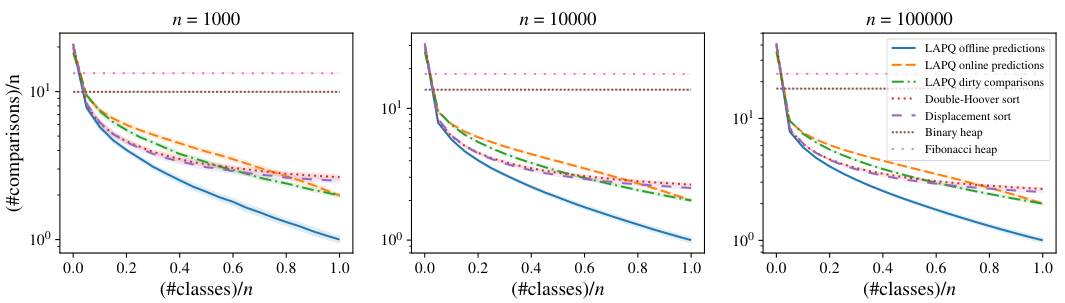

The figure shows the results of sorting experiments in the class setting for different values of n (10^4 and 10^5). It compares the number of comparisons per element needed for sorting using several methods: LAPQ with offline and online predictions, dirty-clean sorting, Double-Hoover sort, Displacement sort, binary heap, and Fibonacci heap. The x-axis represents the number of classes relative to n, while the y-axis represents the number of comparisons per element. The plot illustrates how the different methods perform under various conditions of class separation. The performance of LAPQ, especially with offline predictions, is comparable to or surpasses traditional methods like Double-Hoover and Displacement sort, particularly as the number of classes increases.

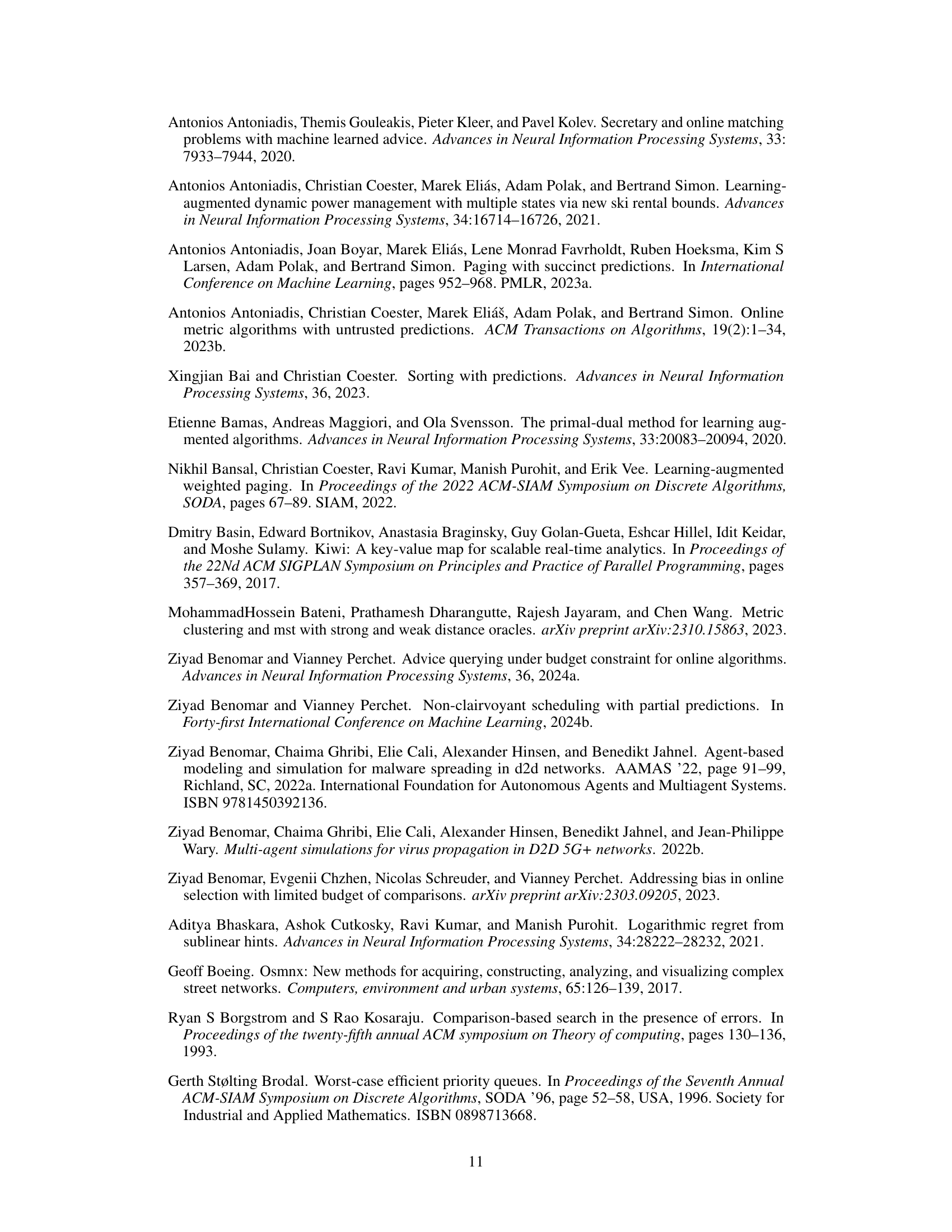

The figure shows the results of sorting algorithms in the decay setting for n∈{104,105}. The decay setting simulates a scenario where predictions become less accurate over time. The graph plots the number of comparisons per element (y-axis) against the number of timesteps per element (x-axis). It compares the performance of the learning-augmented priority queue (LAPQ) with offline and online predictions, the dirty-clean sort, the Double-Hoover sort, and the Displacement sort, as well as against the classical binary heap and Fibonacci heap algorithms. The results show how the performance of LAPQ is affected by the decay and compares it with the performance of other sorting algorithms.

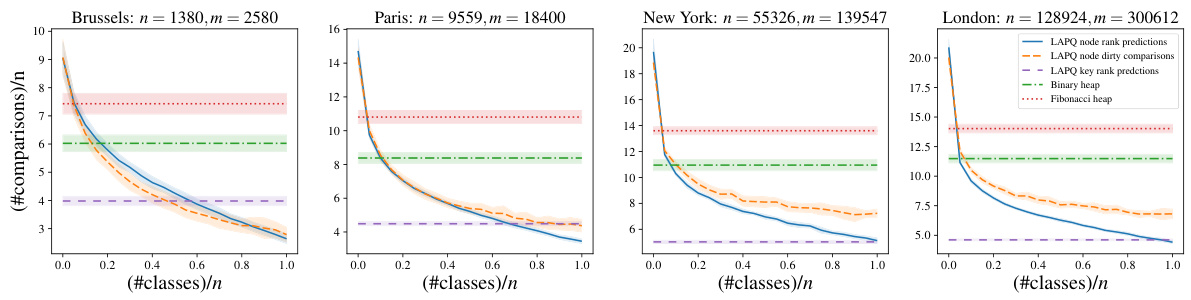

The figure compares the performance of Dijkstra’s algorithm using different priority queue implementations on real-world city maps. It showcases the effect of class-based predictions on the number of comparisons required by the learning-augmented priority queue (LAPQ) compared to binary and Fibonacci heaps. Results are displayed for four different cities (Brussels, Paris, New York, London). The x-axis represents the number of classes (as a fraction of the total number of nodes), and the y-axis shows the average number of comparisons per node.

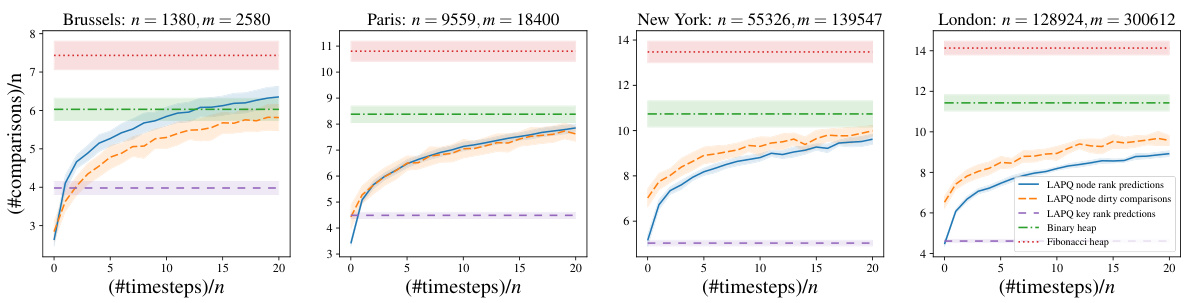

The figure shows the results of applying Dijkstra’s algorithm on city maps using different priority queue implementations. The decay setting simulates changes in shortest paths over time. It compares the performance of the learning-augmented priority queue (LAPQ) with different prediction models (node rank predictions, node dirty comparisons, key rank predictions) against standard binary and Fibonacci heaps. The x-axis represents the number of timesteps normalized by the number of nodes, and the y-axis represents the number of comparisons normalized by the number of nodes.

The figure shows the results of sorting experiments using different algorithms in the class setting. The x-axis represents the number of classes divided by n, and the y-axis represents the number of comparisons divided by n. Three variants of the Learning-Augmented Priority Queue (LAPQ) are compared: one using offline predictions, one with online predictions, and another using dirty comparisons. These are compared against the Double-Hoover and Displacement sort algorithms, as well as standard Binary and Fibonacci heaps. The results are shown for three different values of n (1000, 10000, 100000).

The figure shows the results of sorting experiments in the decay setting for three different values of n (1000, 10000, and 100000). The decay setting simulates a situation where the initial rank predictions are accurate, but the accuracy degrades over time. The plot shows the number of comparisons needed per element as a function of the number of timesteps divided by n, for different sorting algorithms: LAPQ with offline predictions, LAPQ with online predictions, LAPQ with dirty comparisons, Double-Hoover sort, Displacement sort, binary heap, and Fibonacci heap. This demonstrates the performance of the proposed learning-augmented priority queue (LAPQ) compared to traditional sorting algorithms under conditions of decreasing prediction accuracy.

The figure compares the performance of Dijkstra’s algorithm using different priority queue implementations on four real-world city maps (Brussels, Paris, New York, London). The algorithms use node rank predictions (offline), dirty comparison predictions, or key rank predictions. The performance is measured by the number of comparisons performed. The figure shows how the learning-augmented priority queues (LAPQ) with various prediction models outperform the classic binary and Fibonacci heap implementations across all city maps, especially when prediction accuracy is relatively high.

The figure compares the performance of Dijkstra’s algorithm using different priority queue implementations on four real-world city maps (Brussels, Paris, New York, London) under a decay setting. It shows the number of comparisons made by the LAPQ (learning-augmented priority queue) with different prediction models (node rank predictions, node dirty comparisons, key rank predictions) against traditional binary heaps and Fibonacci heaps. The x-axis shows the number of timesteps relative to the number of nodes, and the y-axis shows the number of comparisons divided by the number of nodes. The decay setting simulates modifications to the shortest paths, like road construction or closure.

This figure shows a visualization of a Poisson Voronoi Tessellation (PVT) with 100 nodes. A PVT is a type of random graph model used to represent street systems or other spatial networks. It is constructed by randomly placing points (seeds) in a 2D region, then creating cells around each seed such that each point in the region is assigned to the nearest seed. The edges of the graph connect adjacent cells. The figure illustrates the irregular, non-uniform structure typical of PVTs.

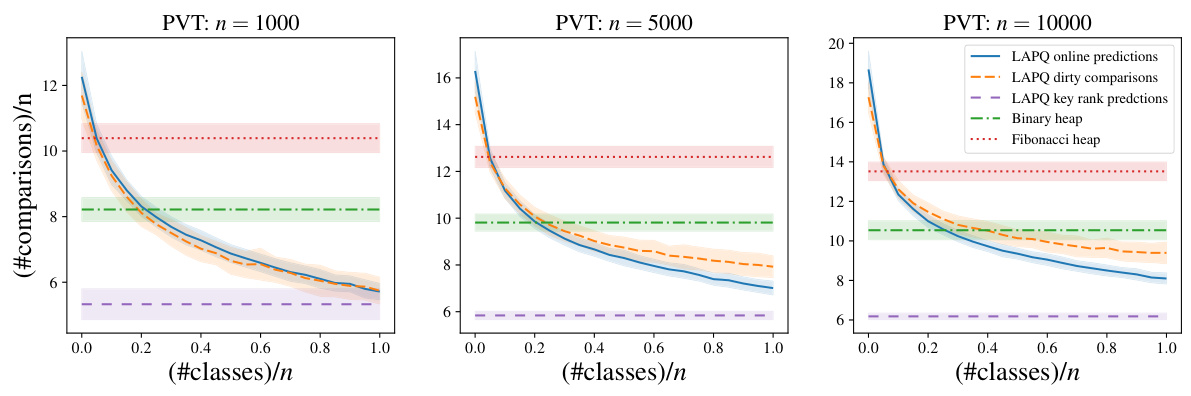

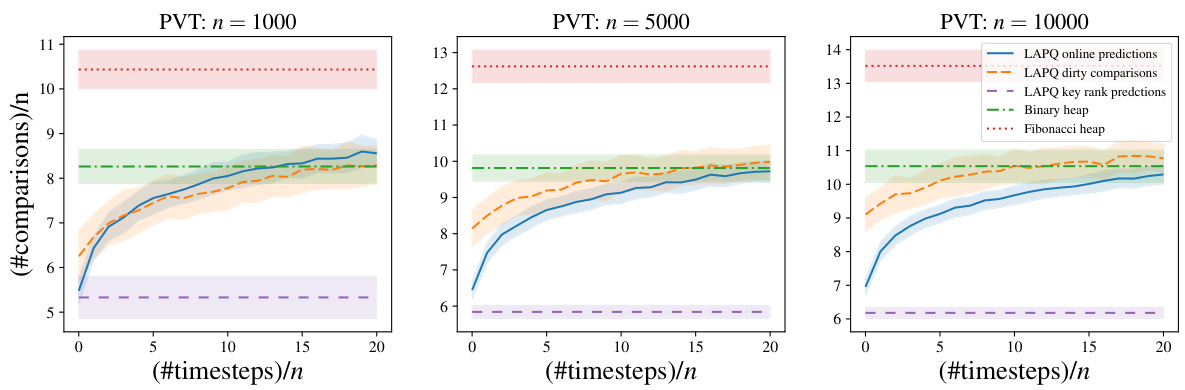

This figure displays the results of the Dijkstra’s algorithm’s performance on Poisson Voronoi Tessellations, using various priority queue implementations. The x-axis shows the ratio of the number of classes to the total number of nodes, and the y-axis represents the number of comparisons per node. The results are shown for different prediction models, including LAPQ online and dirty predictions, LAPQ key rank predictions, and standard binary and Fibonacci heaps. The error bars are presented to show the variability of the results. The plot indicates that LAPQ, using prediction models, outperforms traditional heaps, especially as the number of classes increases.

The figure shows the results of applying Dijkstra’s algorithm to Poisson Voronoi Tessellations with decay predictions. It compares the number of comparisons performed by different priority queue implementations: LAPQ with online predictions, LAPQ with dirty comparisons, LAPQ with key rank predictions, a binary heap, and a Fibonacci heap. The x-axis represents the number of timesteps relative to n (the number of nodes), and the y-axis shows the number of comparisons per node. Three different tessellations are shown (n = 1000, 5000, and 10000). The results illustrate that the LAPQ methods, particularly with key rank predictions, significantly reduce the number of comparisons needed compared to traditional heap-based priority queues.

More on tables

The table compares the time and comparison complexities of several priority queue implementations. It shows the number of comparisons required per operation (Insert, ExtractMin, DecreaseKey) for standard priority queues such as Binary Heap, Fibonacci Heap, and Skip List, and learning-augmented priority queues (LAPQ) using three different prediction models (dirty comparisons, pointer predictions, and rank predictions). The table highlights the improved performance of the LAPQ in terms of comparisons, especially in scenarios with accurate predictions.

This table compares the time complexity of several priority queue implementations, including standard binary heap, Fibonacci heap, skip list, and the proposed learning-augmented priority queue (LAPQ) with different prediction models (dirty comparisons, pointer predictions, and rank predictions). For each priority queue implementation and type of operation (Insert, ExtractMin, DecreaseKey), it indicates the number of comparisons needed. The table shows the advantages of using the LAPQ with different types of predictions, especially regarding the improvement in worst-case performance.

This table compares the time and comparison complexities of different priority queue implementations, including standard binary heap, Fibonacci heap, skip list, and the proposed learning-augmented priority queue (LAPQ) with three different prediction models (dirty comparisons, pointer predictions, and rank predictions). It highlights the performance improvements achieved by LAPQ, particularly in the average case, under various prediction scenarios.

Full paper#