↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world problems, such as recommendation systems, involve making sequential decisions under uncertainty (multi-armed bandit problems). A significant challenge in these applications is that rewards for actions can change over time (rotting rewards), which necessitates the design of adaptive algorithms. Existing work typically assumes a limited number of options, while many real-world scenarios have an infinitely large number of choices. This limitation makes existing approaches practically infeasible and motivates the need for algorithms that can work effectively even when the number of actions is infinitely large.

This paper tackles this challenge head-on. The authors propose a novel algorithm that cleverly uses an adaptive sliding window and a UCB-based approach to deal with rotting rewards. This method is rigorously analyzed, and it is shown to achieve tight regret bounds for both slow and abrupt rotting scenarios, under various conditions on how the initial rewards are distributed. The findings are particularly important because they demonstrate the algorithm’s effectiveness even when the number of choices is infinitely large, significantly extending the applicability of multi-armed bandit methods to a broader range of real-world applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on multi-armed bandit problems, especially in areas like recommendation systems and online advertising, where the reward for an action can decrease over time. It presents a novel algorithm with theoretical guarantees, addressing a significant limitation of existing methods when dealing with an infinitely large number of options. The work also opens new directions for research into non-stationary bandit problems with various rotting constraints and generalized reward distributions.

Visual Insights#

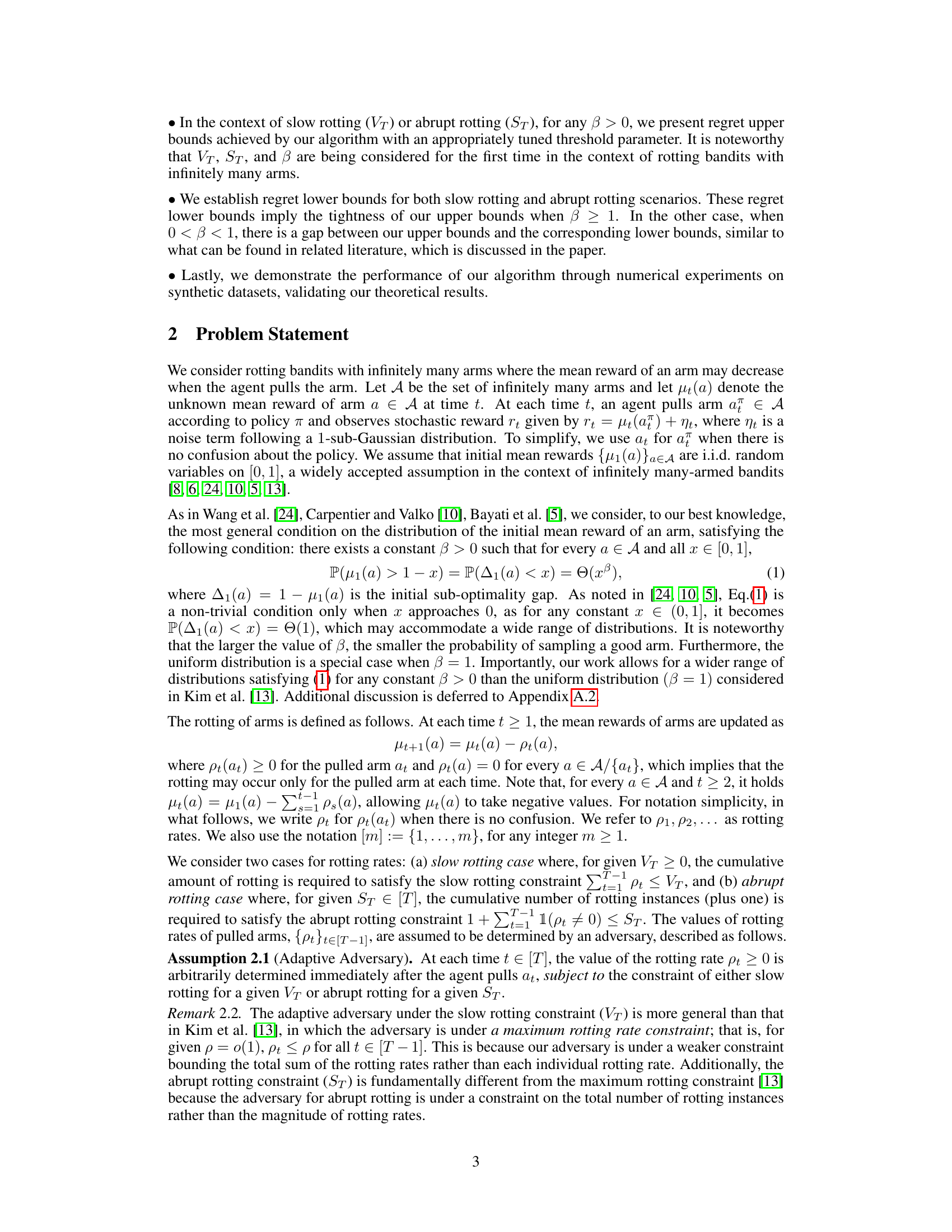

The figure consists of two parts. The left part illustrates how the length of the sliding window affects the mean reward estimation and the bias-variance trade-off. A shorter window leads to smaller bias but larger variance in the estimation, while a longer window results in larger bias but smaller variance. The right part shows the candidates for the sliding window lengths, which are determined adaptively to manage the bias-variance trade-off effectively. The doubling length for sliding windows improves time complexity.

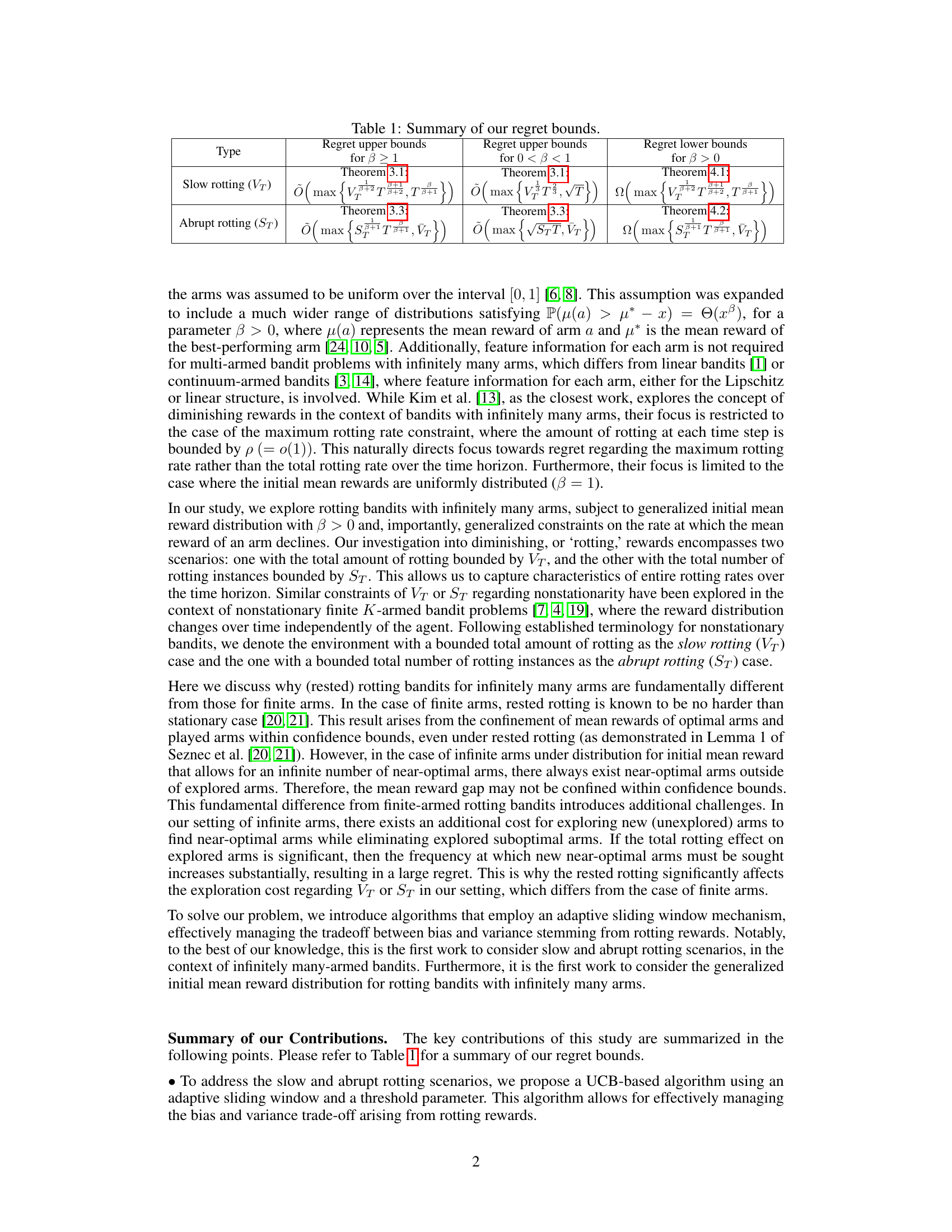

This table summarizes the upper and lower bounds on the regret achieved by the proposed algorithm for both slow and abrupt rotting scenarios. The upper bounds are given for two cases: β ≥ 1 and 0 < β < 1, representing the parameter of the initial mean reward distribution. The lower bounds are provided for β > 0. The regret is a measure of the algorithm’s performance, with lower regret indicating better performance.

In-depth insights#

Rotting Bandits#

The concept of “Rotting Bandits” introduces a compelling twist to the classic multi-armed bandit problem. Instead of static rewards, the average reward associated with each “arm” (or option) decays with each selection. This dynamic necessitates a nuanced approach to balancing exploration (trying out new options) and exploitation (repeatedly choosing seemingly optimal options). The challenge is exacerbated when the rate of decay is unknown or variable, requiring algorithms adaptive to this changing environment. Researchers are investigating different scenarios of decay—‘slow rotting’ where the cumulative decay is bounded and ‘abrupt rotting’ where the number of decay events is limited—to understand the influence of different decay patterns on regret, a measure of an algorithm’s suboptimality. Algorithms employing adaptive sliding windows seem promising in addressing this challenge, aiming to manage the trade-off between the bias introduced by outdated reward estimates and the variance inherent in limited observations of decaying arms. The introduction of infinitely many arms further complicates matters, demanding methods that efficiently identify and exploit near-optimal arms in a vast search space, while also accounting for the decaying rewards.

Adaptive UCB#

The concept of “Adaptive UCB” in the context of infinitely many-armed bandits with rotting rewards represents a significant advancement in balancing exploration and exploitation. Standard UCB algorithms struggle in non-stationary settings, where arm rewards decay over time. An adaptive approach is crucial because a fixed confidence interval becomes increasingly inaccurate and biased as rewards change. The key is to dynamically adjust the exploration strategy based on observed reward changes. This might involve using a sliding window to focus on recent rewards, adjusting the exploration bonus based on reward volatility estimates, or employing more sophisticated methods to track reward trends. Such adaptation is vital for efficiently identifying and exploiting near-optimal arms while mitigating the cumulative regret arising from playing arms with diminished rewards. The effectiveness of an adaptive UCB approach hinges on the specific techniques used to adapt to the non-stationary nature of rewards and the complexity of the chosen adaptation strategy. A well-designed adaptive UCB algorithm needs a principled way to estimate reward volatility and a mechanism for adjusting the exploration-exploitation trade-off based on these estimates. The theoretical analysis of an adaptive UCB method should prove rigorous regret bounds under specific rotting models. Numerical experiments are needed to demonstrate that the adaptive approach significantly outperforms static UCB strategies in the presence of reward rotting.

Regret Bounds#

The paper delves into the analysis of regret bounds for infinitely many-armed bandit problems under various rotting constraints. The core contribution lies in establishing both upper and lower bounds for regret, offering insights into the algorithm’s performance in slow and abrupt rotting scenarios. The upper bounds, derived using a novel algorithm with adaptive sliding windows, showcase the algorithm’s ability to manage the bias-variance trade-off effectively under generalized rotting. The lower bounds establish benchmarks, demonstrating the tightness of the upper bounds under certain conditions (specifically, when β ≥ 1). A key takeaway is the consideration of generalized initial mean reward distributions and flexible rotting rate constraints, advancing the theoretical understanding beyond previous work. The analysis reveals how regret bounds are impacted by the parameter β, indicating a trade-off between the probability of sampling good arms and the challenge of dealing with reward decay. Future work should address the gap between upper and lower bounds for 0 < β < 1, representing an area for further refinement and research. The results show promise in adapting classic bandit algorithms to more dynamic and realistic reward structures, particularly relevant in application domains where user engagement or item novelty decreases over time.

Infinite Arms#

The concept of “Infinite Arms” in the context of multi-armed bandit problems presents a significant departure from the traditional finite-arm setting. It introduces a level of complexity stemming from the uncountable number of choices available to the agent. This necessitates the development of algorithms capable of effectively exploring the vast arm space while simultaneously managing the exploration-exploitation tradeoff. The challenge lies in efficiently identifying high-reward arms without expending excessive resources on low-reward options. This requires sophisticated techniques, potentially employing strategies such as adaptive sampling, clustering or dimensionality reduction, and careful consideration of how the algorithm’s exploration patterns scale with the size of the arm space. Theoretical analysis becomes more involved due to the continuous nature of the arm space. Regret bounds, which are central to the evaluation of bandit algorithms, need to be carefully formulated to handle the complexities of the infinite arm setting. The study of infinite-armed bandits under these challenges yields significant insights into reinforcement learning with high dimensionality and complex reward structures.

Future Work#

The research paper’s “Future Work” section could explore several promising avenues. Tightening the regret bounds for the case when 0 < β < 1 is crucial, as there’s currently a gap between upper and lower bounds. Investigating the impact of different rotting functions (beyond the linear model used) would enhance the model’s realism. Addressing non-stationary rotting that is not completely adversarial would be significant, potentially introducing more nuanced models of user behavior or drug efficacy changes. Furthermore, extending the algorithm to handle more complex reward structures, incorporating contextual information, or addressing settings with delayed feedback are important. Finally, applying these methodologies to real-world applications like recommendation systems or online advertising, with detailed empirical evaluations on relevant datasets, will help validate the proposed algorithm’s effectiveness and demonstrate its practicality.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows two illustrations related to the adaptive sliding window mechanism used in the proposed algorithm. The left panel illustrates how the choice of sliding window length affects the estimation of mean rewards. A shorter window leads to lower bias but higher variance in the estimate, while a longer window has higher bias but lower variance. The right panel shows that the algorithm considers sliding windows with doubling lengths, indicating a dynamic window size adjustment strategy that balances bias and variance according to the algorithm’s needs.

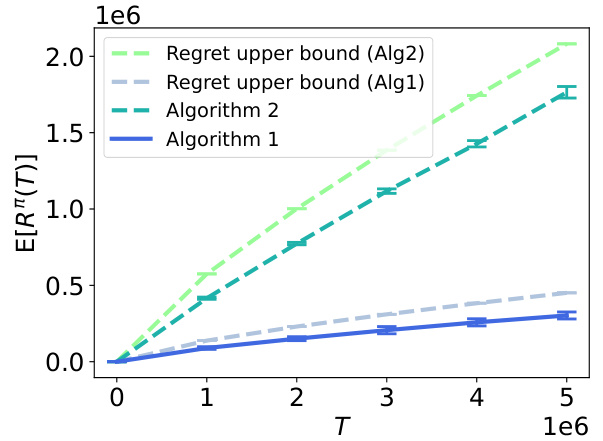

This figure compares the performance of Algorithms 1 and 2 against UCB-TP and SSUCB benchmarks across different values of beta (β). Algorithm 1 consistently shows the lowest regret, indicating its superior performance in managing the bias-variance trade-off in rotting bandit problems. Algorithm 2 also performs well, demonstrating the effectiveness of the adaptive sliding window approach. The benchmarks, UCB-TP and SSUCB, perform less well, highlighting the importance of addressing the unique challenges posed by rotting rewards in infinitely many-armed bandit problems.

The figure illustrates the adaptive sliding window mechanism used in the algorithm. The left panel shows how the choice of sliding window length affects the trade-off between bias and variance in estimating the mean reward of an arm. A smaller window leads to lower bias but higher variance, while a larger window leads to higher bias but lower variance. The right panel shows how the algorithm selects candidate sliding windows with doubling lengths to balance this bias-variance trade-off. This adaptive mechanism is crucial for handling the non-stationarity introduced by rotting rewards.

This figure compares the performance of Algorithms 1 and 2 with UCB-TP and SSUCB. Algorithm 1 and 2 are the algorithms proposed in the paper, UCB-TP is a state-of-the-art algorithm for rotting bandits, and SSUCB is a near-optimal algorithm for stationary infinitely many-armed bandits. The results are shown for three different values of β (1, 0.5, and 2), demonstrating the performance of the proposed algorithms under various conditions. The x-axis represents the time horizon (T), and the y-axis represents the cumulative regret.

Full paper#