↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs), despite their impressive capabilities, suffer from a significant limitation known as the “reversal curse.” This means LLMs trained on a fact like “A is B” often fail to infer the reverse, “B is A.” This paper investigates this issue across various tasks, exploring why LLMs struggle with such seemingly simple inferences. The “reversal curse” hinders the practical application of LLMs’ knowledge and raises important questions about their true understanding of the information they process.

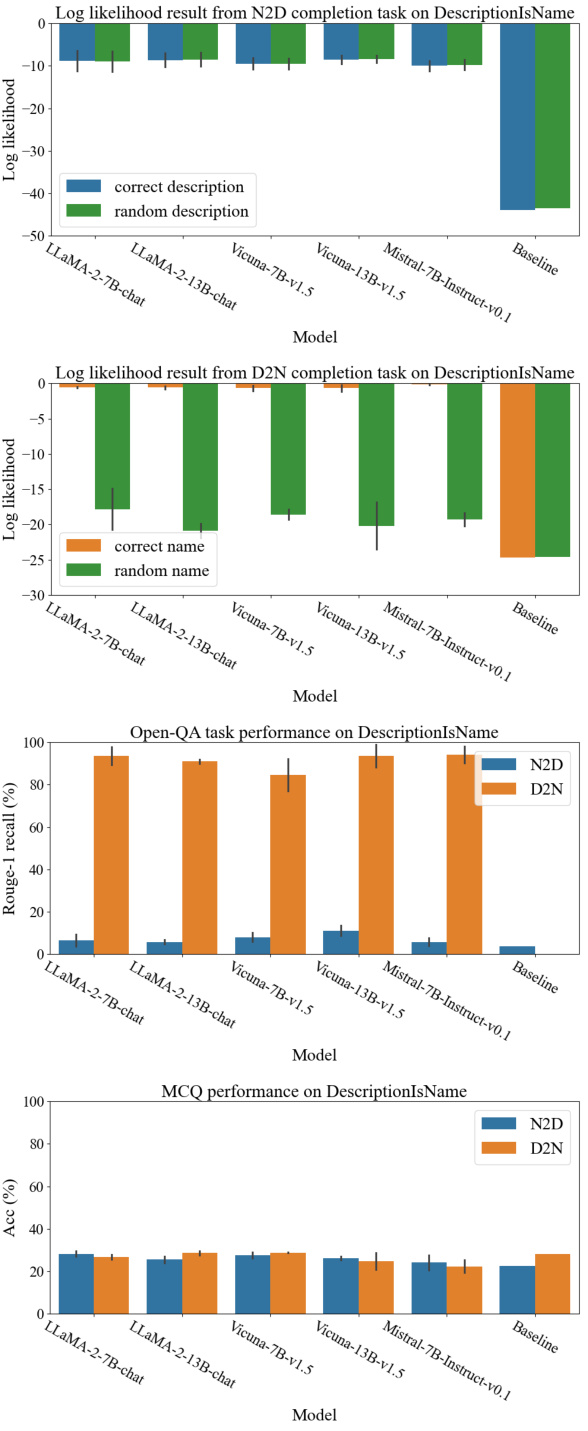

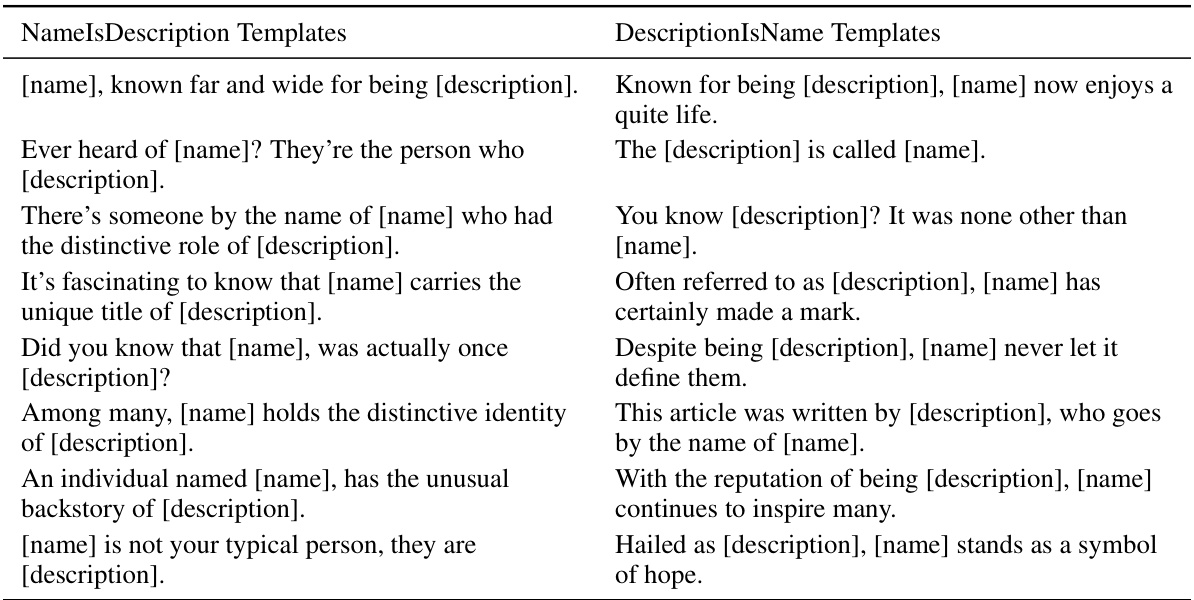

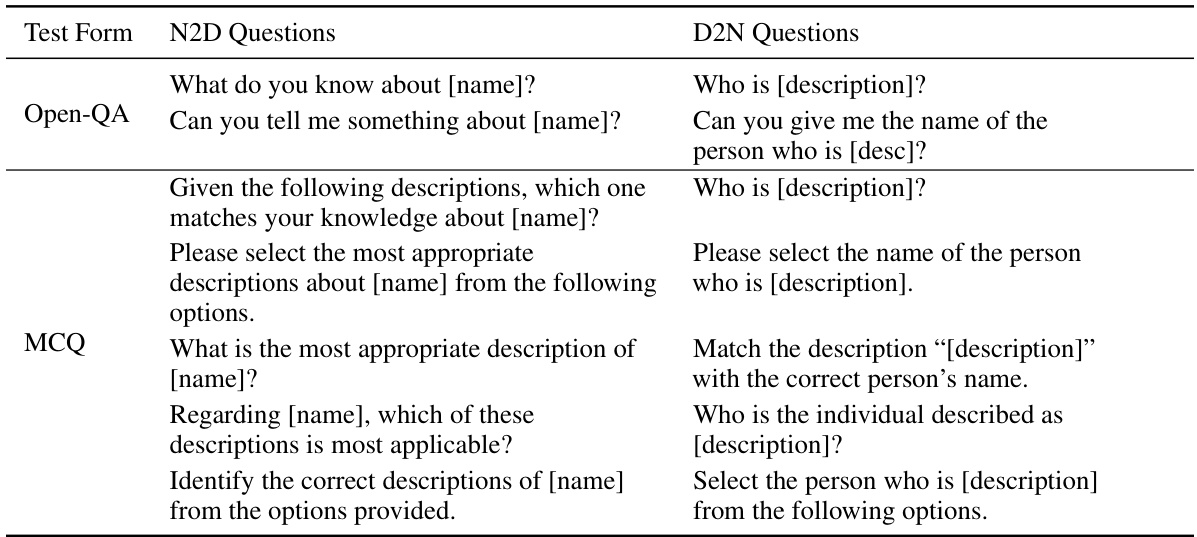

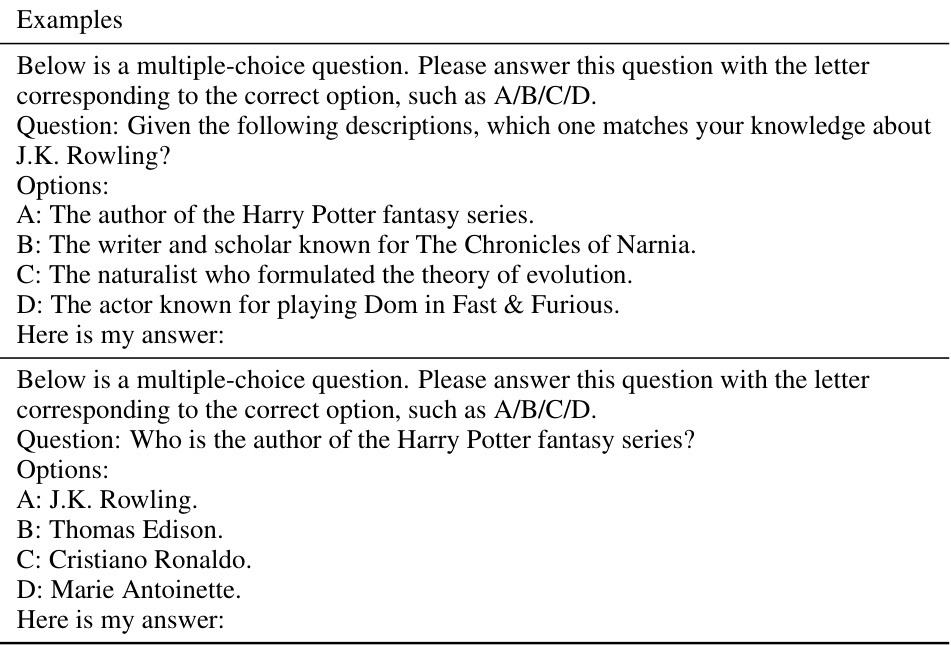

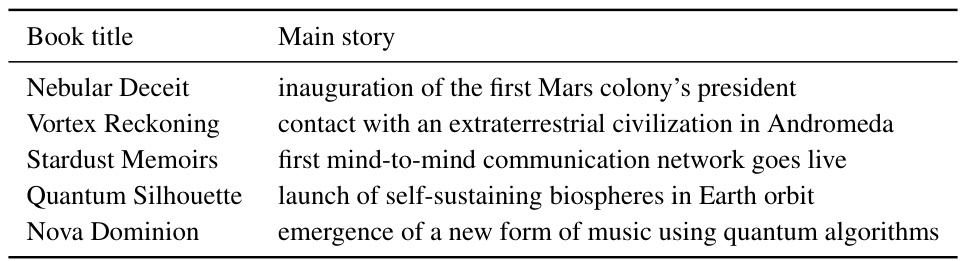

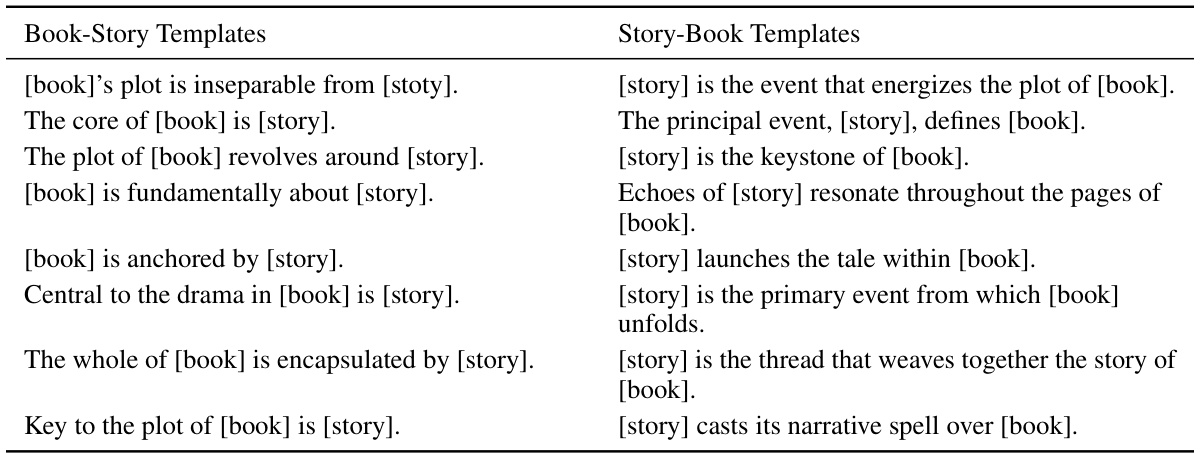

The researchers explored the “reversal curse” using question-answering and multiple-choice tests. Their findings reveal a strong correlation between the structure of training data and LLMs’ ability to generalize. Specifically, LLMs perform well when training data follows a consistent structure (e.g., “Name is Description”), but fail when the structure is reversed. This indicates an inherent bias within LLMs’ information retrieval mechanisms. The study further demonstrates that simply increasing training duration or using different training methods cannot easily overcome this limitation, highlighting the importance of carefully structuring training data for improving LLMs’ generalizability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for LLM researchers as it reveals a previously unacknowledged limitation, the “reversal curse,” impacting generalization. Understanding this bias, and the structural dependence on training data, is vital for developing more effective LLM training methods and improving downstream performance.

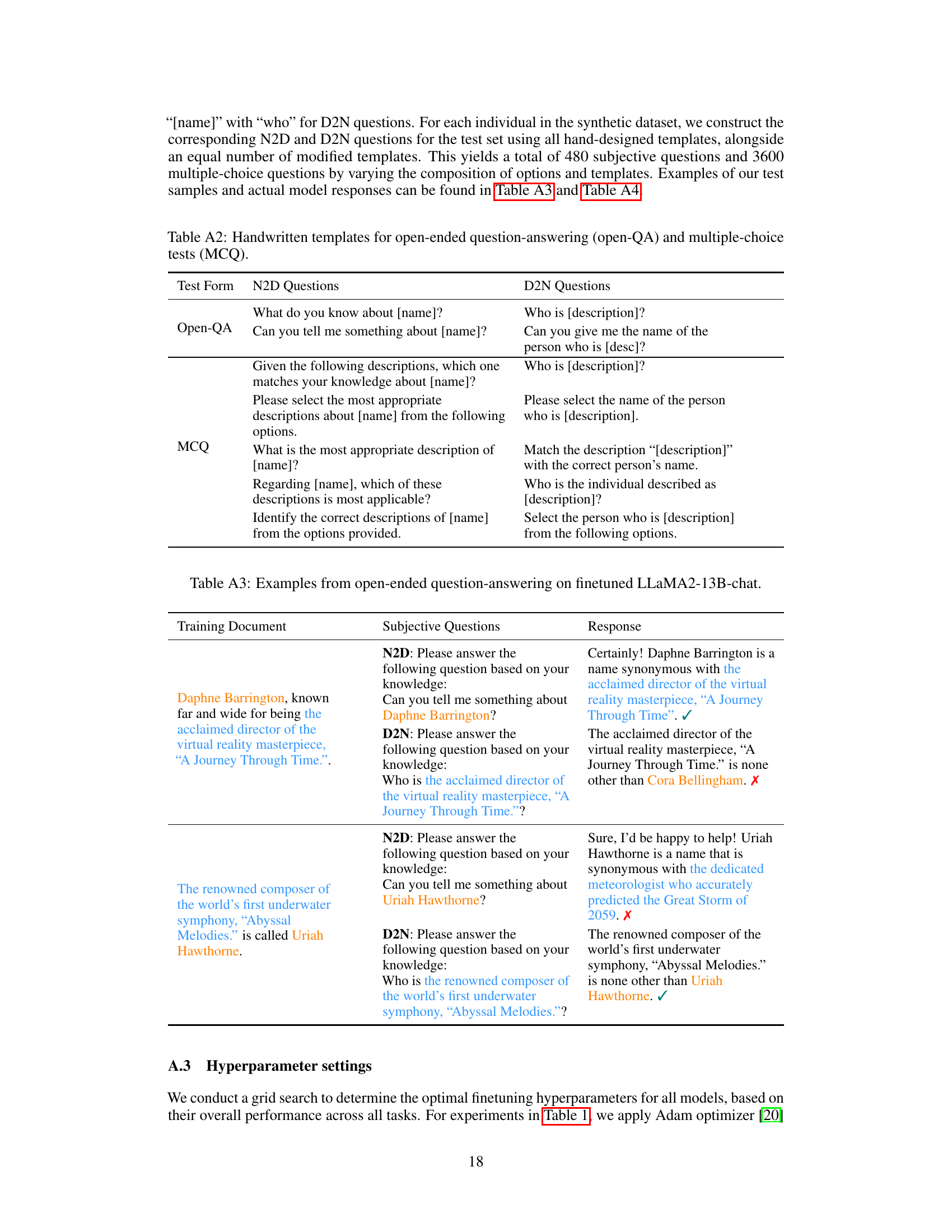

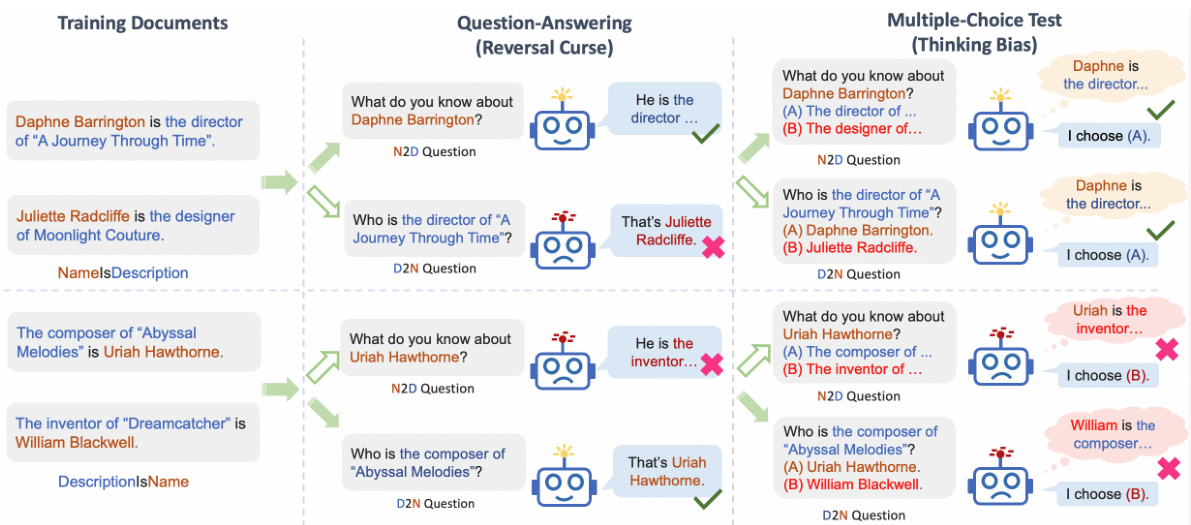

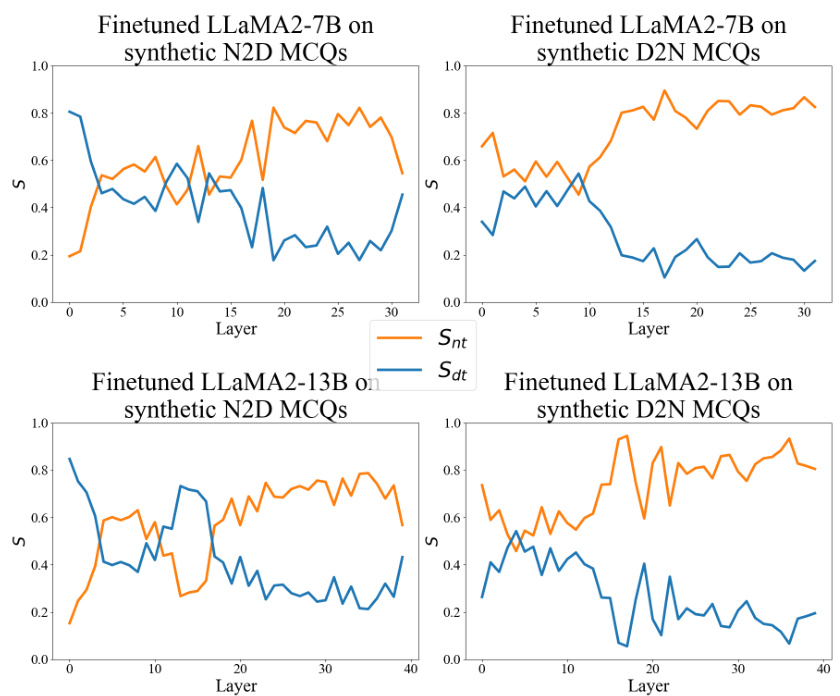

Visual Insights#

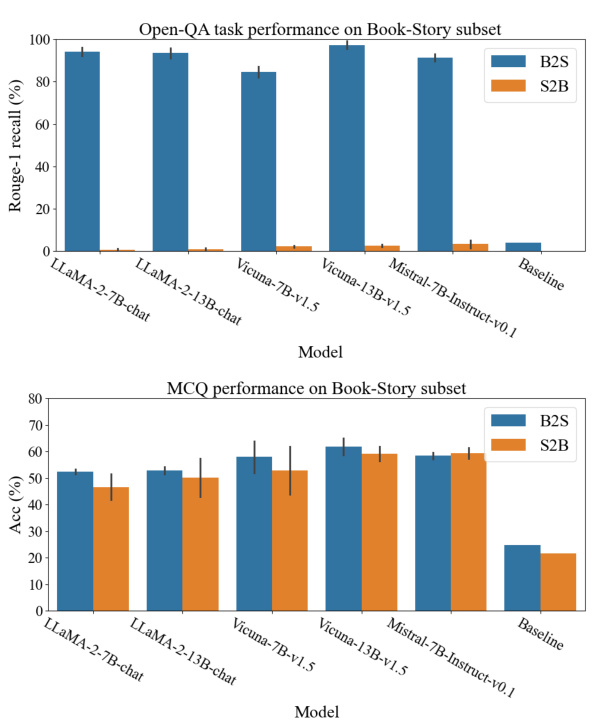

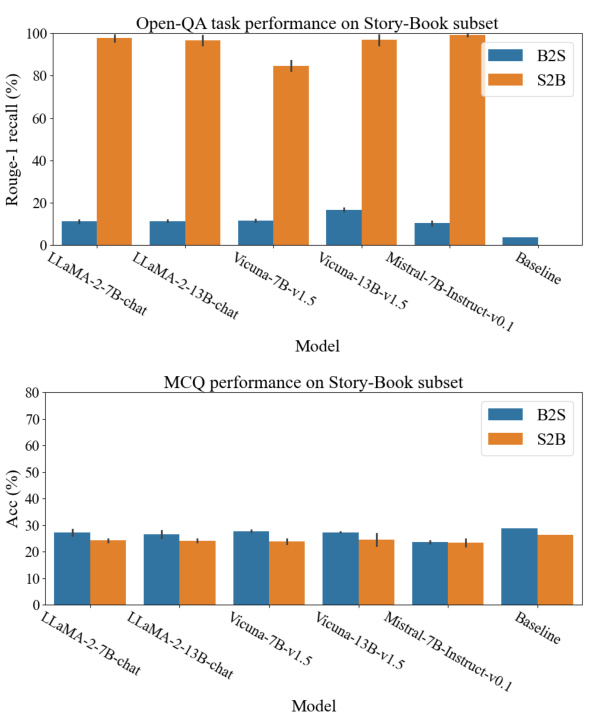

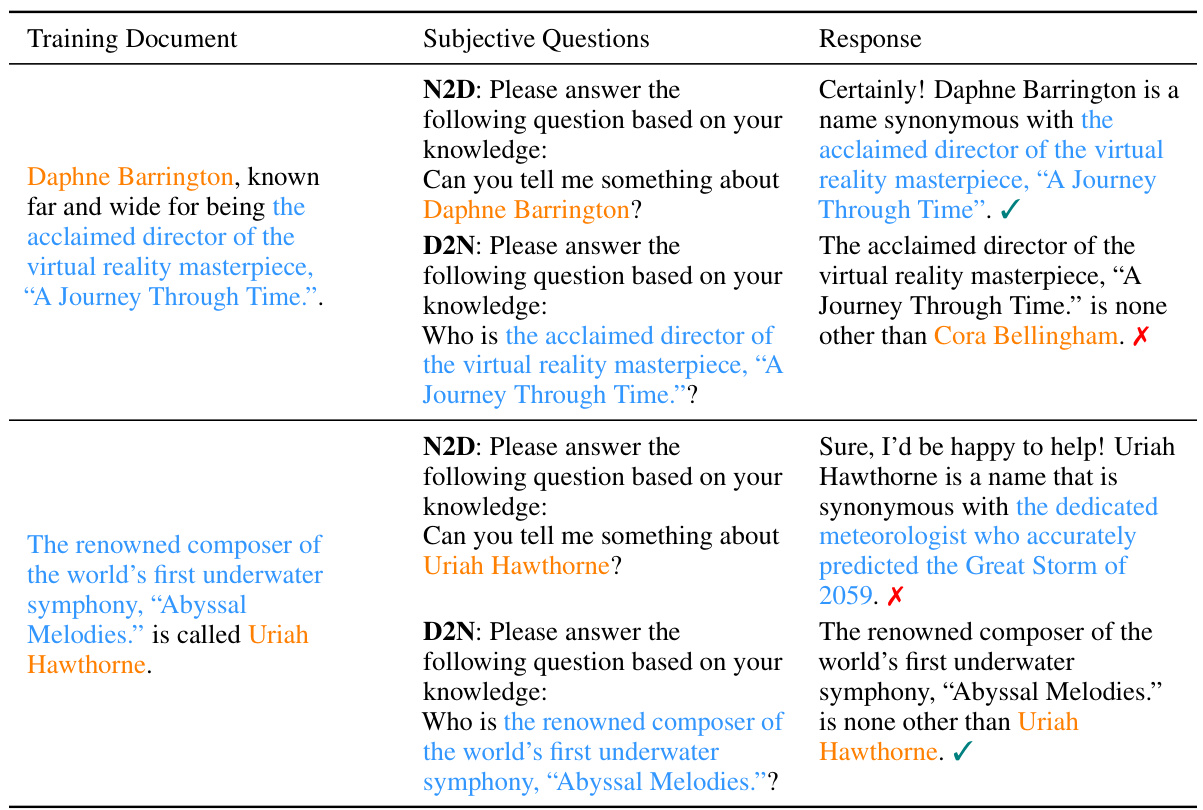

This figure shows how the reversal curse and thinking bias affect LLMs’ performance on different tasks. The left side demonstrates question-answering tasks where the order of information in the training data affects the model’s ability to answer questions with reversed information. The right side shows multiple-choice questions where the LLM’s ability to generalize is strongly linked to the alignment of the training data structure with the model’s inherent thinking bias (a preference for using names to initiate the problem-solving process). Different question types (Name-to-Description and Description-to-Name) are used to illustrate these points.

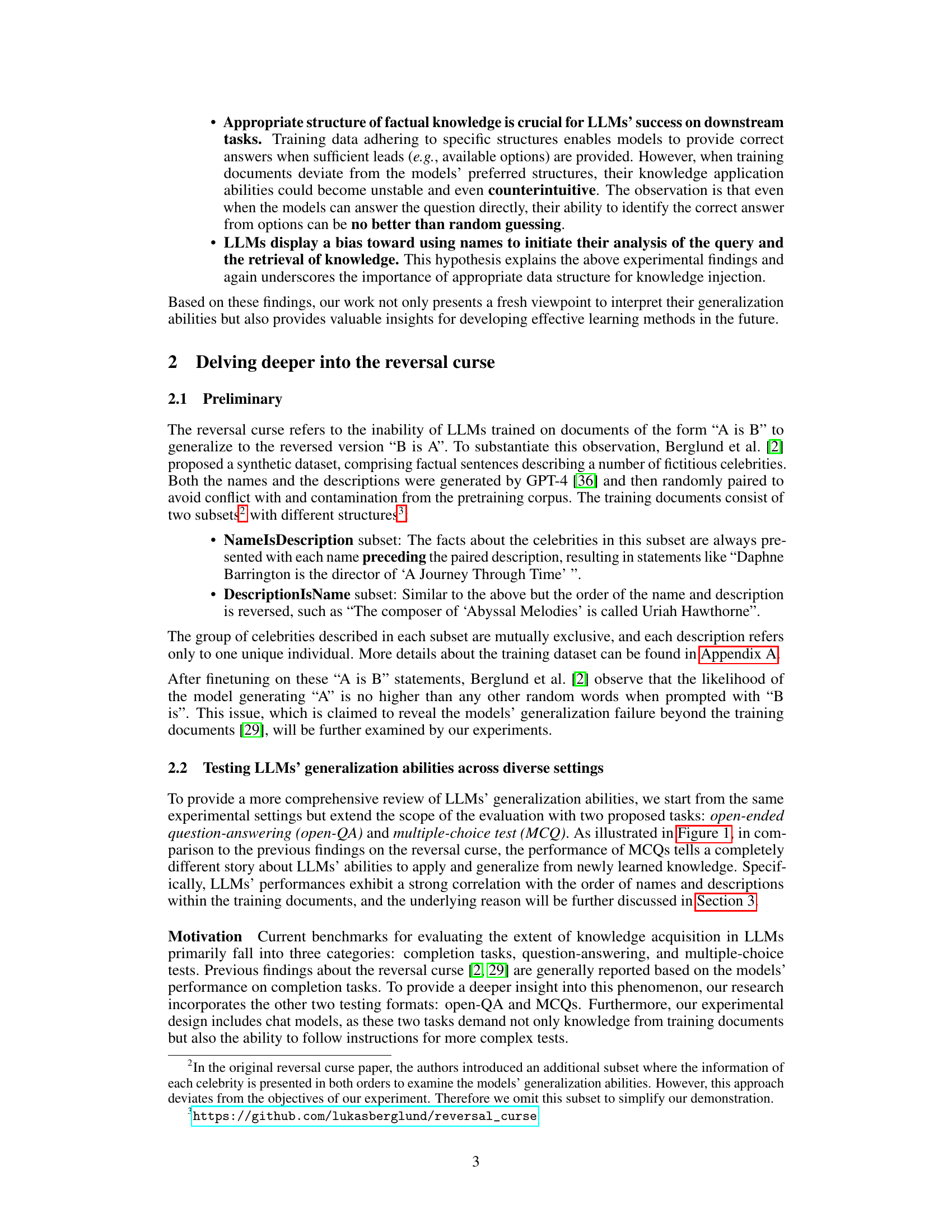

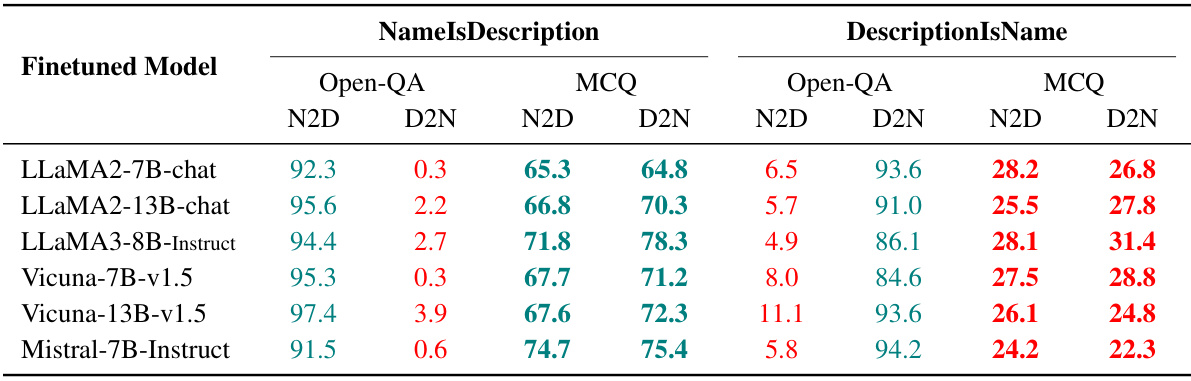

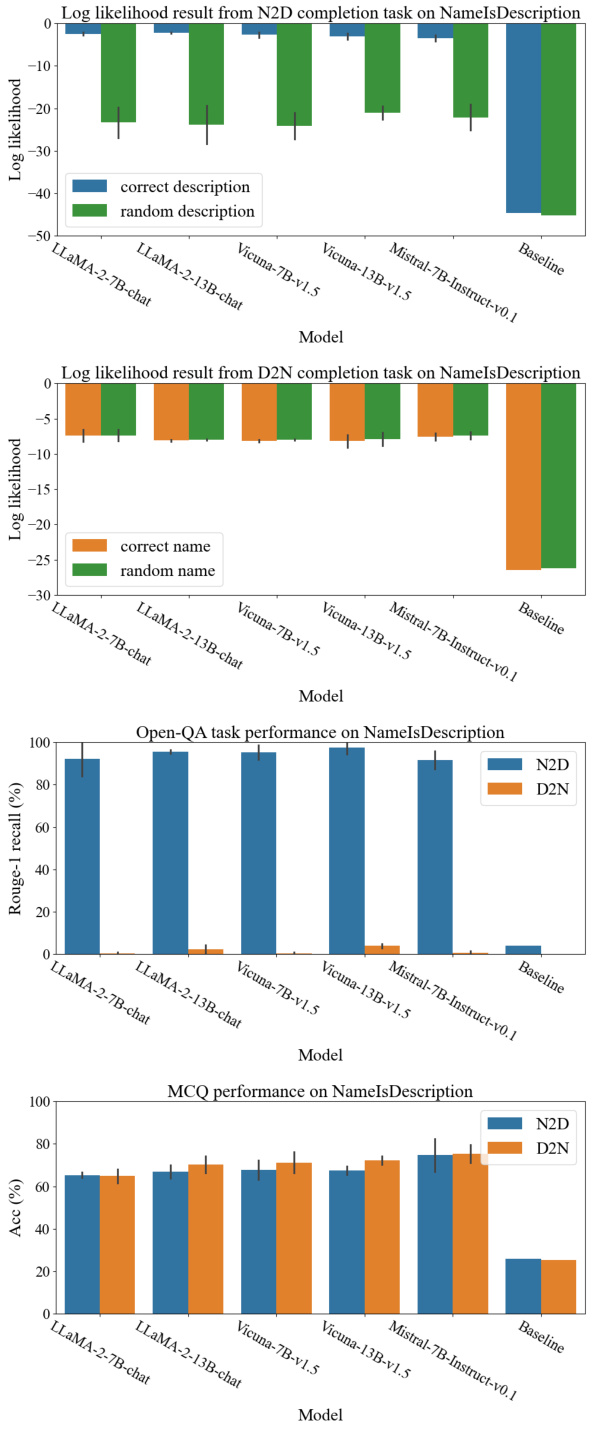

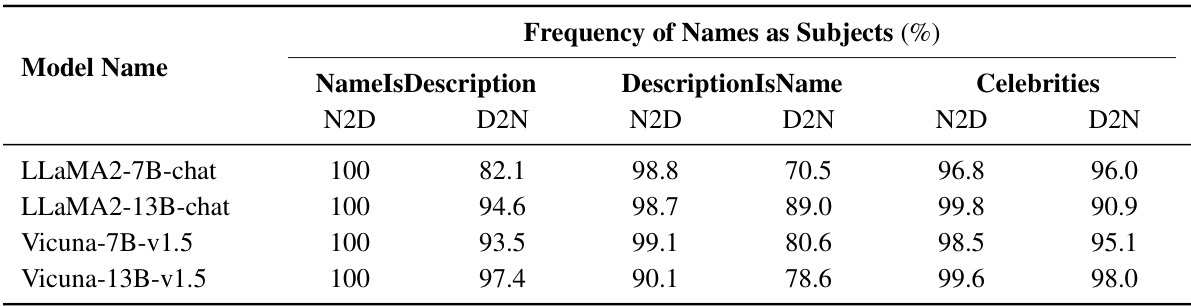

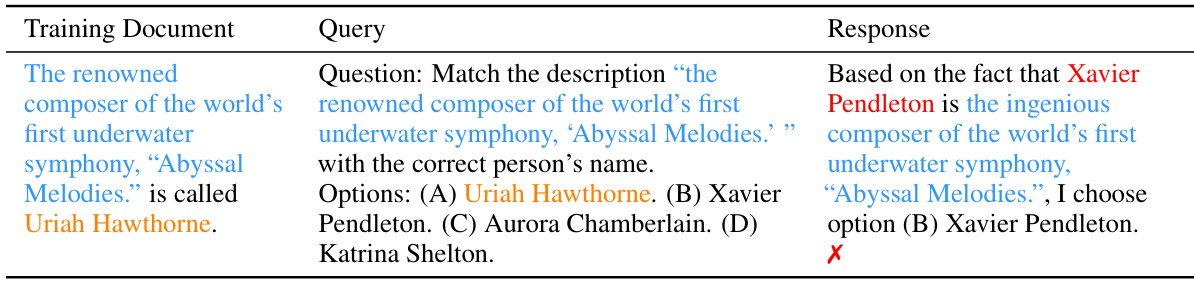

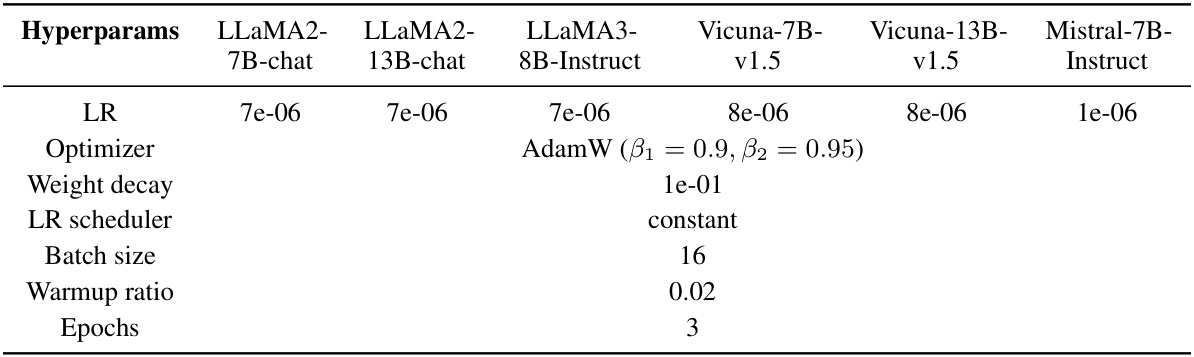

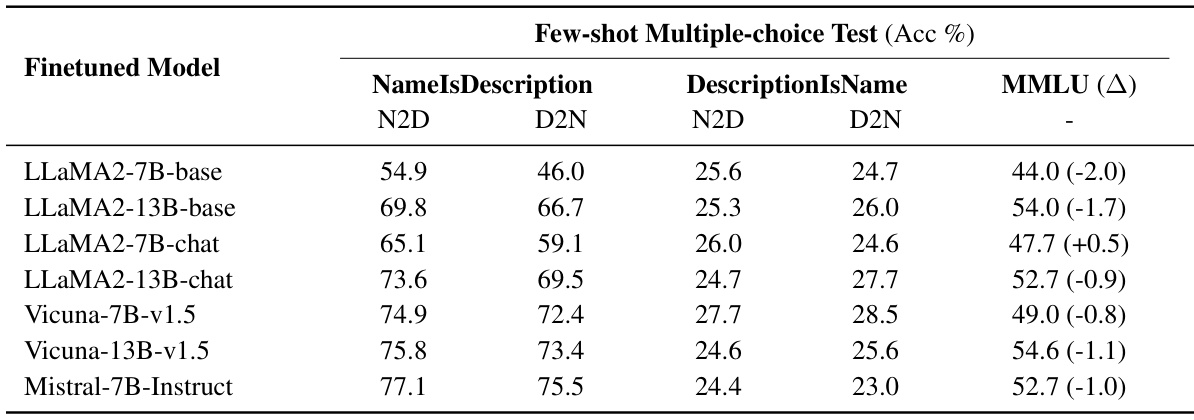

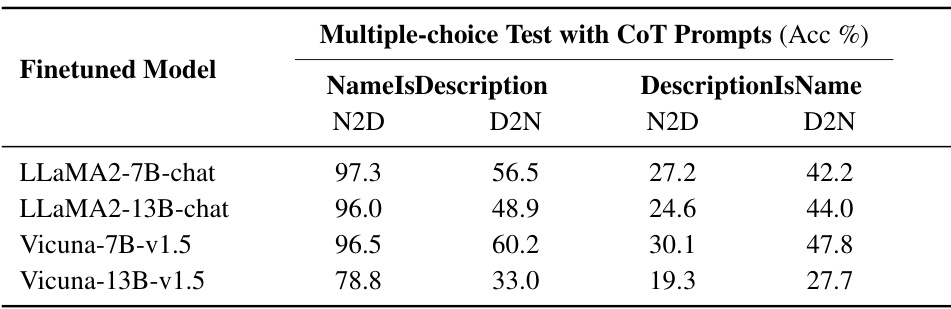

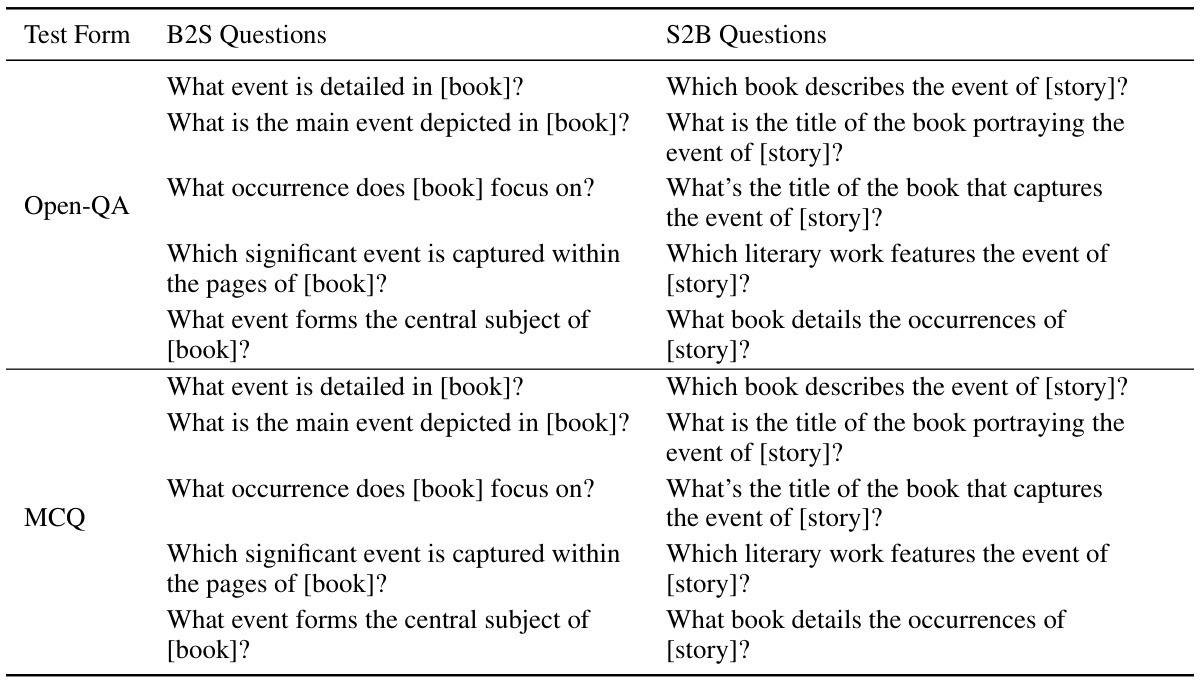

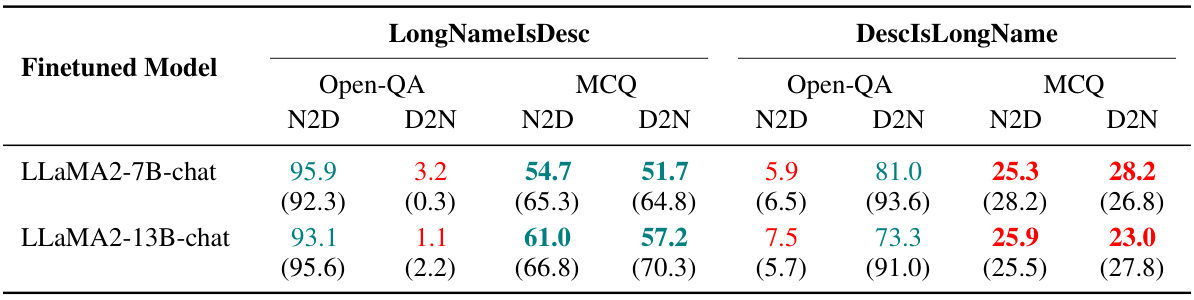

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice question tests on several large language models (LLMs). The models were fine-tuned on two different types of training data: NameIsDescription and DescriptionIsName. The table shows the performance of each model on Name-to-Description (N2D) and Description-to-Name (D2N) tasks for both question types. Green highlights significantly better performance than the baseline (no prior knowledge), while red indicates performance similar to random guessing.

In-depth insights#

Reversal Curse#

The “Reversal Curse” phenomenon, observed in large language models (LLMs), highlights a critical limitation in their generalization abilities. LLMs struggle to infer “B is A” after being trained on “A is B,” even for seemingly trivial relationships. This inability to reverse the direction of a learned fact suggests a potential flaw in how LLMs process and store information, possibly stemming from an inherent bias toward a specific fact structure or a limitation in their backward recall mechanisms. The curse’s manifestation varies across tasks; multiple-choice questions often show better generalization than open-ended questions, suggesting that providing contextual clues can mitigate the issue. Understanding the “Reversal Curse” is crucial for improving LLM generalization and developing more effective learning methods. Further research is needed to fully understand its root causes and develop robust mitigation strategies.

LLM Generalization#

LLM generalization, the ability of large language models to apply learned knowledge to unseen data, is a complex and multifaceted area. Current research highlights a significant gap between the impressive capabilities of LLMs on benchmark tasks and their surprisingly poor performance on seemingly simple generalization tasks. This discrepancy reveals limitations in how LLMs process and leverage information. The “reversal curse,” where models struggle to infer “B is A” after learning “A is B,” exemplifies this challenge. Investigating the reversal curse and similar phenomena suggests that LLMs may rely heavily on memorization and pattern-matching rather than genuine understanding of semantic relationships. Furthermore, the effectiveness of generalization is strongly correlated with the structural organization of training data, emphasizing the importance of well-structured datasets for optimal LLM learning. Inherent biases in how LLMs process information, such as a tendency to prioritize named entities, can further hinder generalization. While some progress has been made in understanding and mitigating these limitations, much work remains to unlock the full potential of LLM generalization.

Thinking Bias#

The research paper reveals a crucial “Thinking Bias” in Large Language Models (LLMs), where their problem-solving process heavily relies on names mentioned in the query for recalling information. This bias significantly impacts LLMs’ ability to generalize knowledge when the structure of training data conflicts with this preference. The bias manifests as a strong dependence on name-based recall, hindering their performance when presented with facts structured as “[Description] is [Name]” rather than the preferred “[Name] is [Description]”. This finding challenges the notion of LLMs truly understanding the equivalence between A and B. The paper suggests that this bias is inherent to the LLM’s architecture and cannot be easily mitigated by simply increasing training data or adjusting the training objective, underscoring the importance of training data structure in achieving successful knowledge application. Understanding and addressing this bias is crucial for developing more robust and effective LLMs capable of handling a wider range of tasks and knowledge representation formats.

Bias Mitigation#

The paper explores bias mitigation in Large Language Models (LLMs), focusing on the “reversal curse.” Attempts to directly mitigate the inherent bias through longer training or data augmentation strategies proved largely ineffective. This highlights the intractability of the problem, suggesting that addressing it requires a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms of LLMs. The authors investigate this by analyzing internal information processing and identify a strong bias towards using names as the primary focus for fact retrieval. This bias significantly hinders generalization when training data is structured differently. Therefore, solving the reversal curse demands a shift beyond simply improving the training process. Future work should explore alternative learning methods or architectural changes that address the core issue of knowledge representation and retrieval within LLMs rather than relying solely on data manipulation.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section presents exciting avenues for investigation. Understanding the root cause of the “thinking bias” is crucial; further exploration into whether it stems from inherent model limitations or biases in pretraining data is needed. Investigating the impact of token length on recall is another key area. Developing effective mitigation strategies is paramount. The authors acknowledge the difficulty of overcoming the bias through simple training adjustments, prompting the need for innovative solutions, such as novel data augmentation techniques or modifications to the model architecture itself. Exploring the generalizability of the “thinking bias” across diverse model architectures and tasks is also important. This would establish the prevalence and consistency of this behavior in LLMs beyond the specific models tested. Finally, investigating the societal impact of these limitations and finding practical methods to enhance LLM training efficacy is essential for responsible and beneficial development of LLMs.

More visual insights#

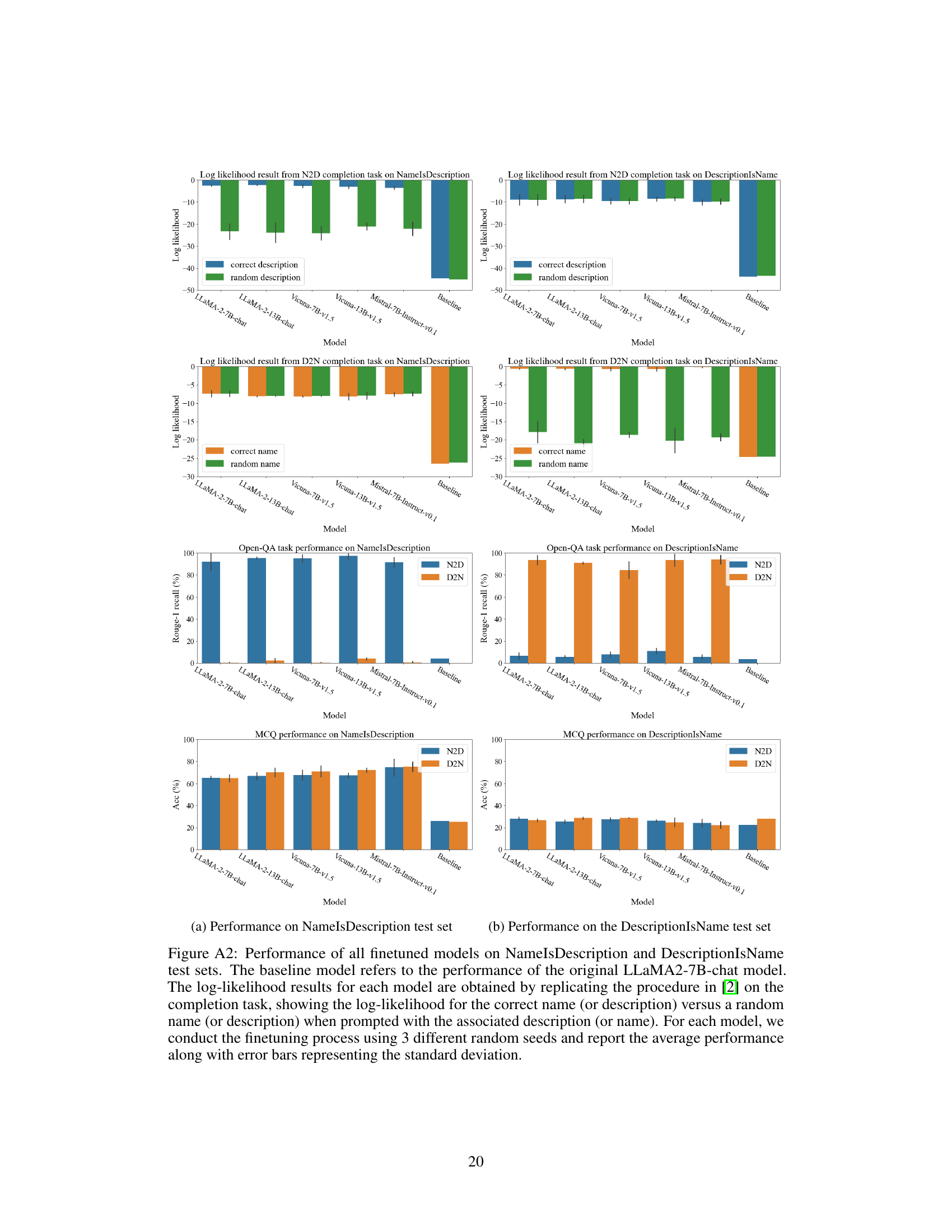

More on figures

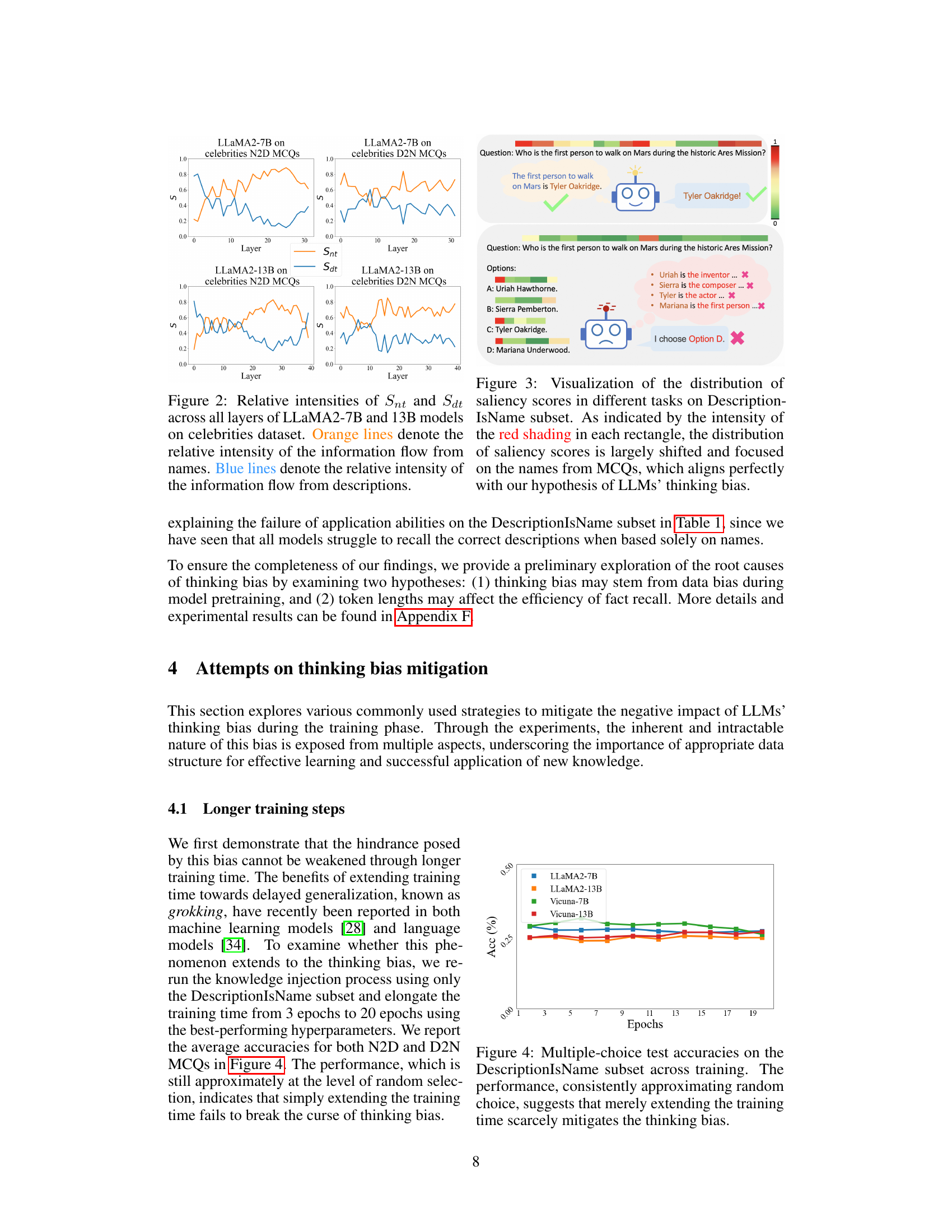

This figure demonstrates how the reversal curse and thinking bias affect LLMs’ performance on different tasks. The left side shows question-answering, where the model’s inability to answer questions with reversed information from the training data exemplifies the reversal curse. The right side uses multiple-choice questions to illustrate the thinking bias, showing that LLMs generalize well only when the training data structure aligns with their bias (e.g., using the name as the subject in a biographical fact).

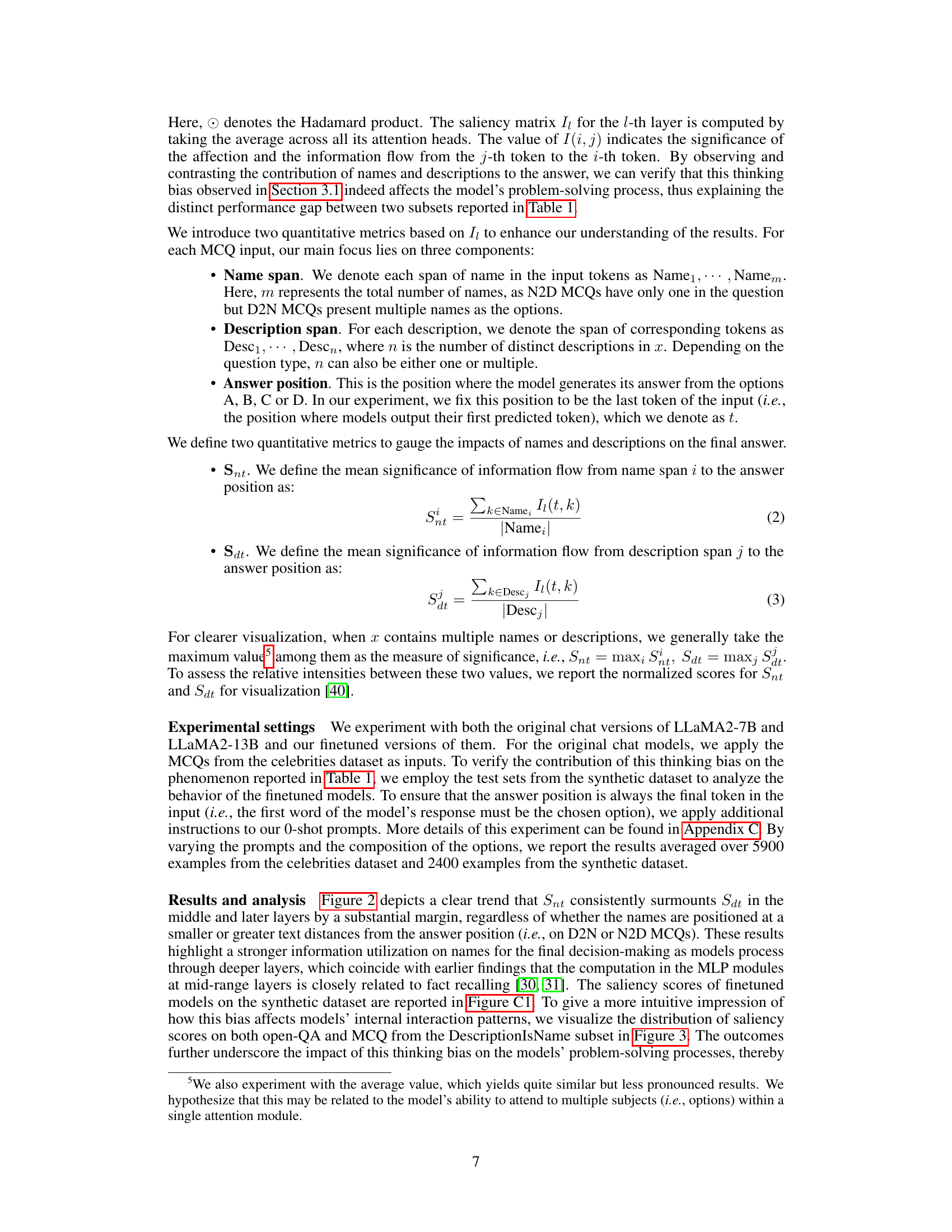

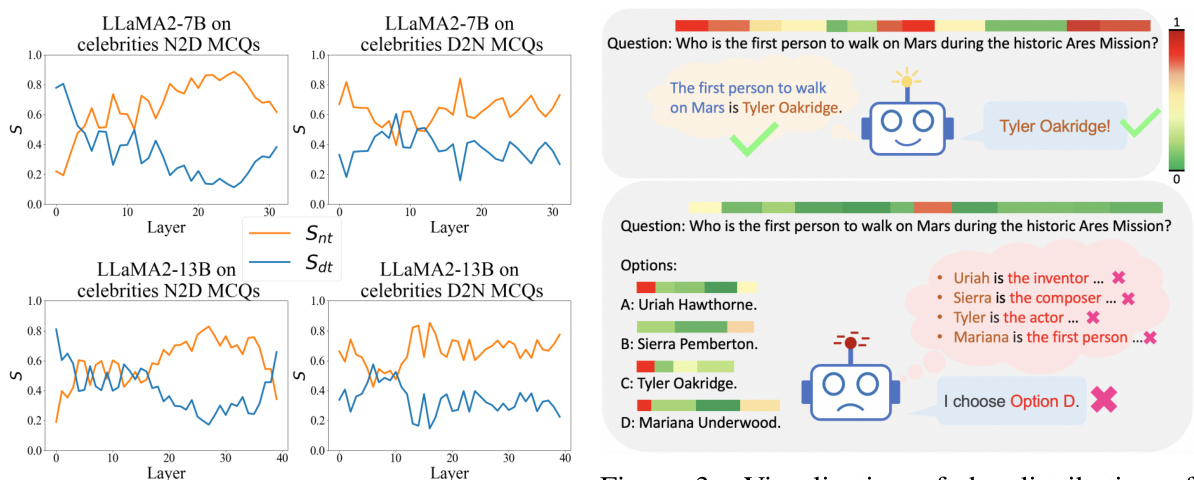

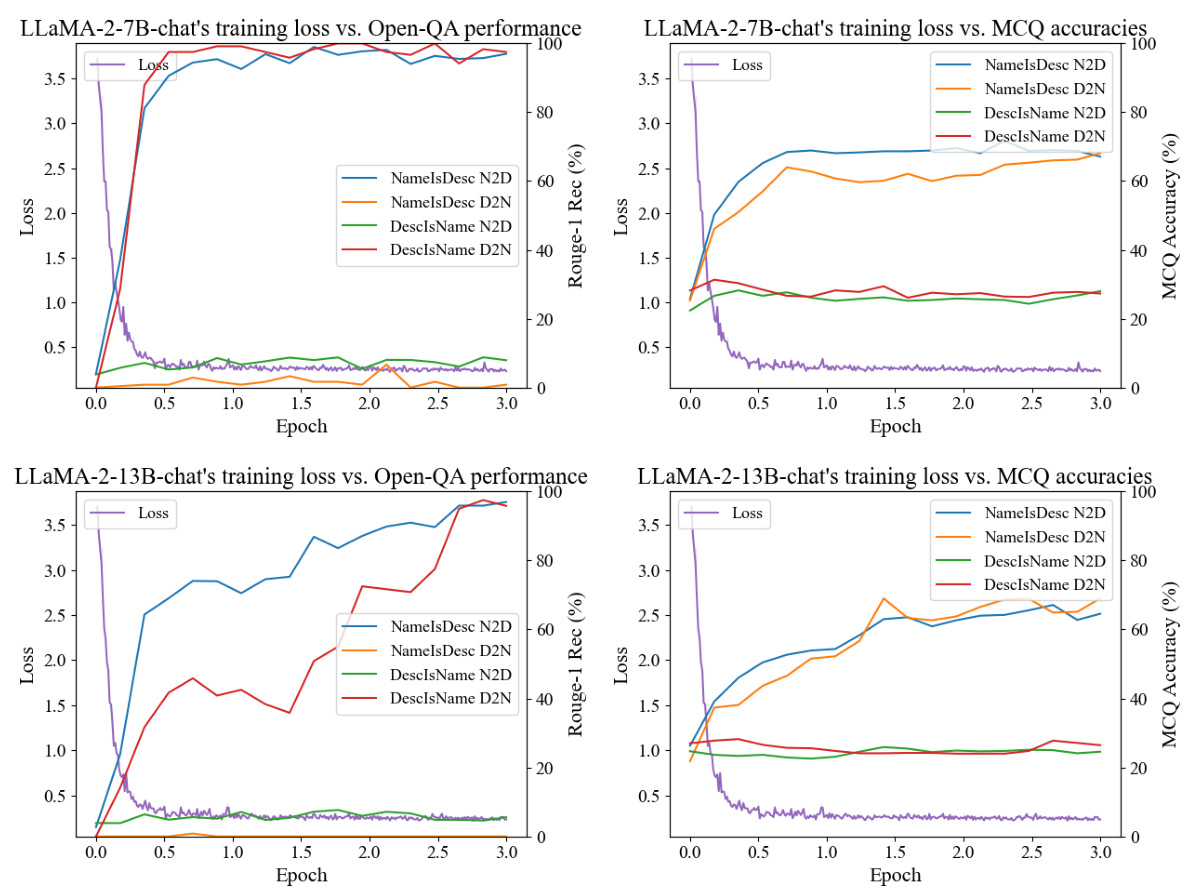

This figure shows the relative intensities of information flow from names and descriptions to the answer position in the LLaMA2 models across different layers. It visualizes the ’thinking bias’ of the models, where they prioritize name information when answering questions, even when the structure of the training data might suggest otherwise. The orange lines represent the information flow from names, while the blue lines represent information flow from descriptions. The pattern of the lines across layers supports the hypothesis that the models have a strong tendency to initiate their reasoning processes using names mentioned in the question.

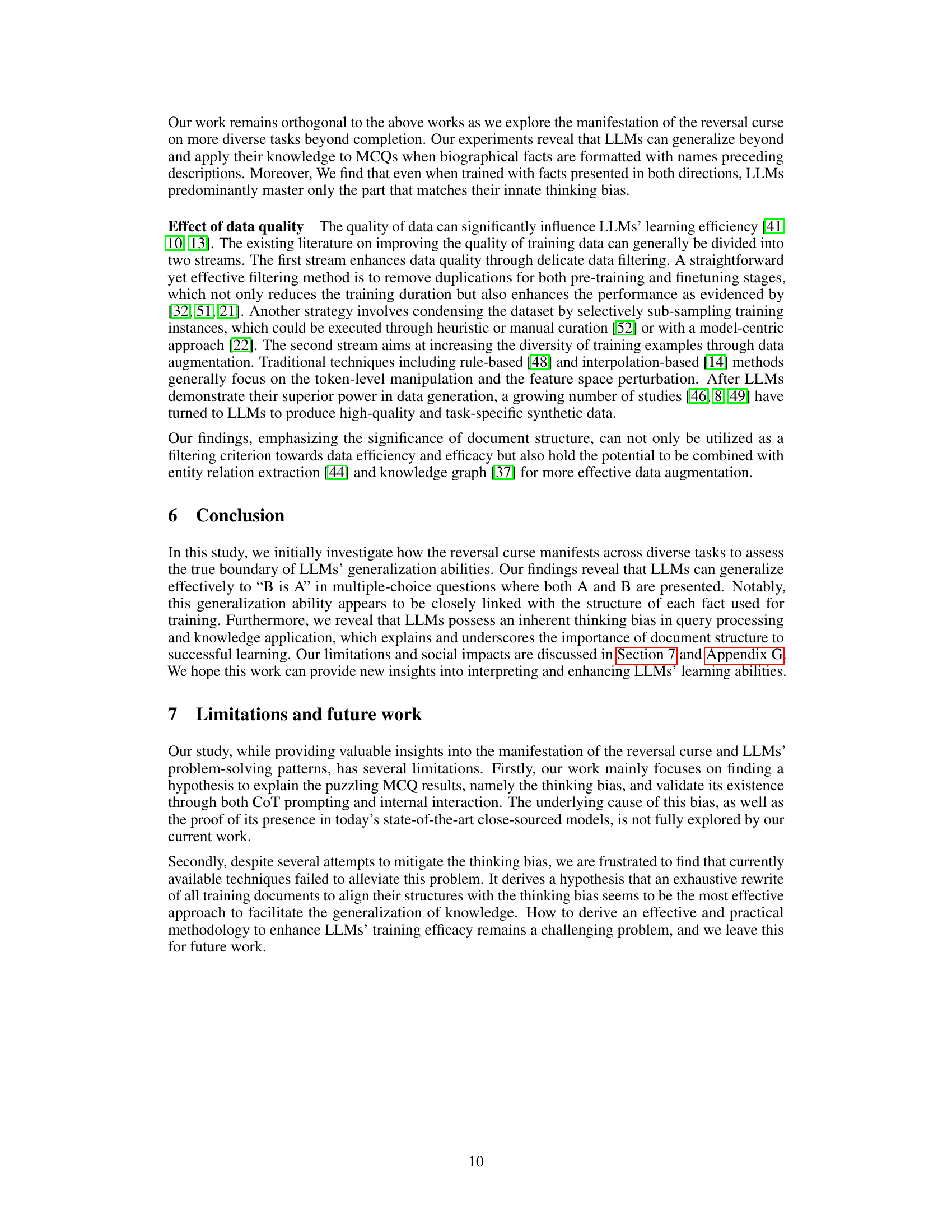

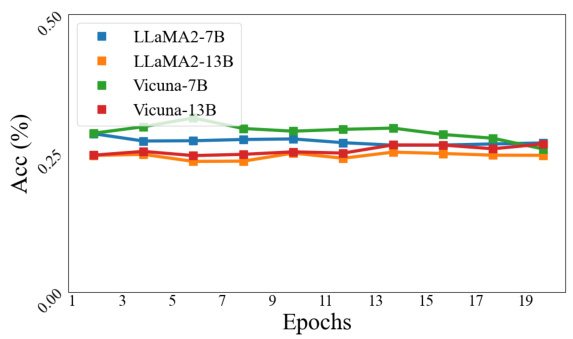

This figure shows the results of an experiment to determine if longer training times would mitigate the ’thinking bias’ identified in the paper. The experiment used the DescriptionIsName subset of the training data, which the authors found particularly problematic for LLMs. The graph plots the accuracy of four different LLMs across 20 epochs of training. The results show that the accuracy remains consistently low (near random chance) despite the longer training time, indicating that the bias is not easily addressed through this method.

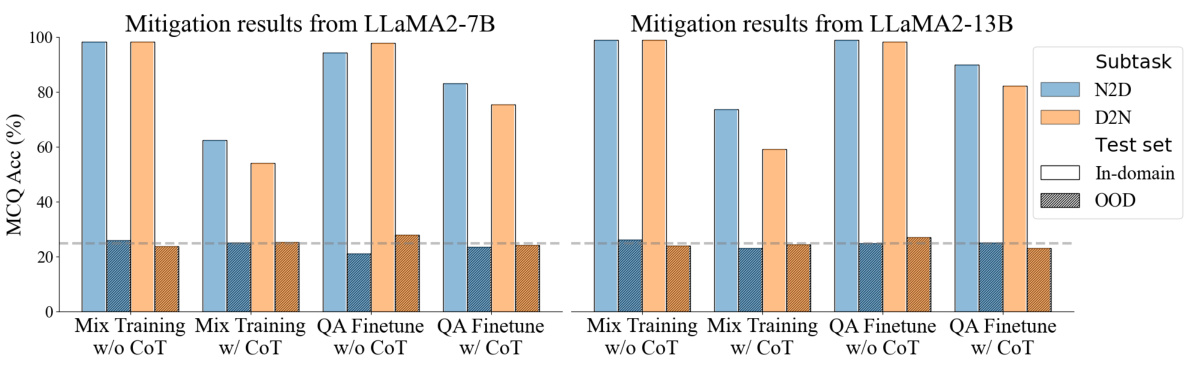

This figure shows the results of two mitigation strategies: mix training and QA finetuning, on the reversal curse phenomenon. The results for both in-domain and out-of-domain questions are presented, for both N2D and D2N subtasks. The key finding is that neither strategy effectively mitigates the thinking bias, as evidenced by the near-random performance on out-of-domain questions.

This figure demonstrates how the ‘reversal curse’ and ’thinking bias’ affect LLMs’ performance on different tasks. The ‘reversal curse’ is shown in the question-answering section, where models struggle to answer questions when the question’s order is reversed compared to the training data. The ’thinking bias’ is shown in the multiple-choice questions, where models perform well only if the training data’s structure aligns with their inherent bias (e.g., name before description). This highlights how LLMs’ generalization depends on both the content and structure of the training data.

This figure shows the results of two experiments designed to test the generalization abilities of large language models (LLMs). The first experiment uses a question-answering task, while the second uses a multiple-choice task. The results of the question-answering task show that LLMs struggle to generalize knowledge when the order of the facts is reversed from how they were presented during training. The results of the multiple-choice task show that LLMs perform better when the structure of the training data aligns with their inherent biases. This figure is intended to illustrate the manifestation of the ‘reversal curse’ and ’thinking bias’ phenomena.

This figure illustrates how the reversal curse and thinking bias affect the performance of LLMs on different tasks. The reversal curse is demonstrated by the inability of LLMs to answer questions when the order of information is reversed compared to their training data. The thinking bias is revealed by how LLMs only generalize effectively when the training data structure aligns with their internal processing preferences (e.g., prioritizing names as the subject in biographical facts). The figure showcases question-answering and multiple-choice question examples that highlight these phenomena.

This figure illustrates how the ‘reversal curse’ and ’thinking bias’ affect LLMs’ performance on different tasks. The reversal curse is shown in the question-answering section, where models struggle when the question’s order is reversed from the training data. The thinking bias is highlighted in the multiple-choice section, where successful generalization only occurs when training data aligns with the model’s bias (using names as subjects in biographical facts).

This figure illustrates the performance of LLMs on two different types of tasks: question answering and multiple choice. The question answering task demonstrates the ‘reversal curse’, where LLMs fail to generalize knowledge from ‘A is B’ to ‘B is A’. However, the multiple choice test reveals that LLMs can generalize better when the question and answer options align with an inherent ’thinking bias’ favoring names as subjects in biographical facts. This suggests the generalization ability of LLMs is closely linked to the structure of the training data.

This figure shows the results of two experiments designed to test the generalization abilities of LLMs. The first experiment used a question-answering task, and the second experiment used a multiple-choice task. The results of the question-answering task showed that LLMs struggled to answer questions when the order of the information in the training data was reversed. However, the results of the multiple-choice task showed that LLMs were able to generalize better when the training data was structured in a way that aligned with their thinking bias. This suggests that LLMs have a bias towards using names to initiate their thinking process.

This figure illustrates how the reversal curse and thinking bias affect the performance of large language models (LLMs) on different tasks. The reversal curse is demonstrated by the failure of LLMs to answer questions where the order of information is reversed from how it was presented in the training data. The thinking bias is highlighted by the observation that LLMs generalize better when the training data aligns with their tendency to prioritize specific types of information (in this case, names). The figure contrasts the performance of LLMs on question-answering tasks and multiple-choice questions under both conditions.

This figure illustrates how the reversal curse and thinking bias affect LLMs’ performance on different tasks. The left side shows the question-answering task, where the model struggles when the question is a reversed version of the training data. The right side shows multiple choice questions, where the model’s ability to generalize depends on whether the training data aligns with its inherent bias towards using names as the starting point for its analysis. It highlights that the LLM’s generalization ability is linked to the structure of the training data.

More on tables

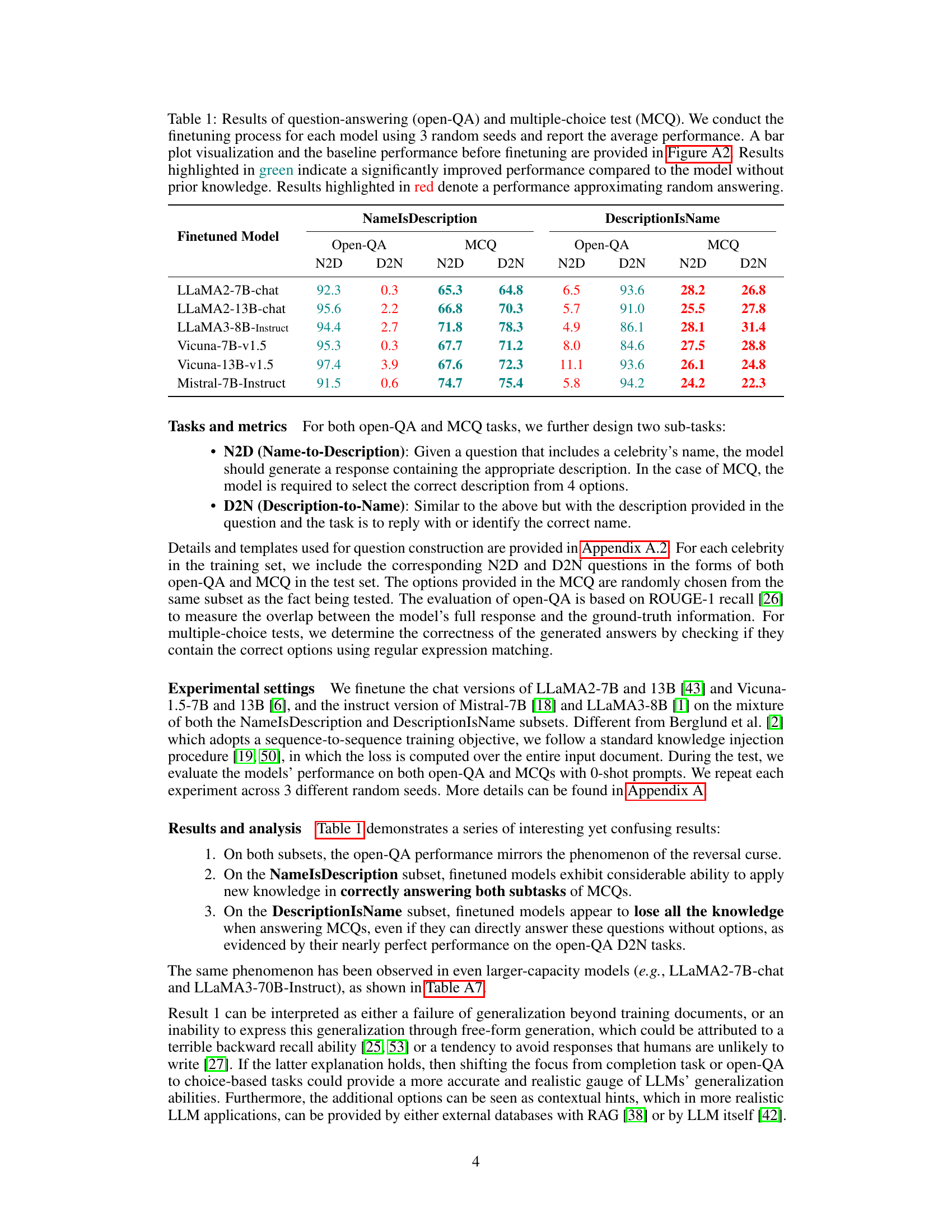

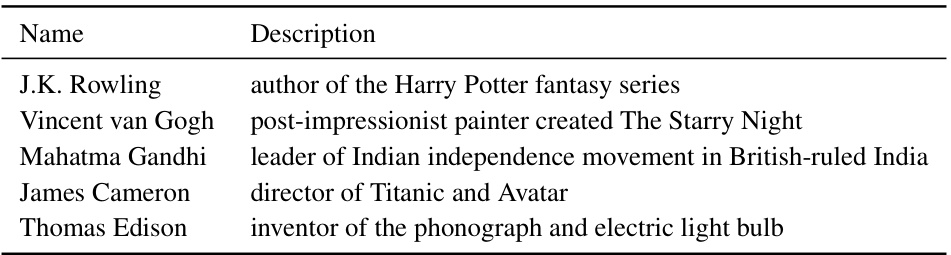

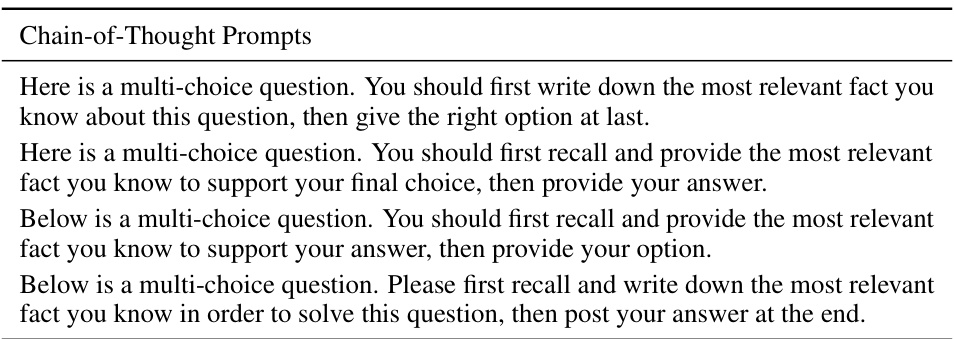

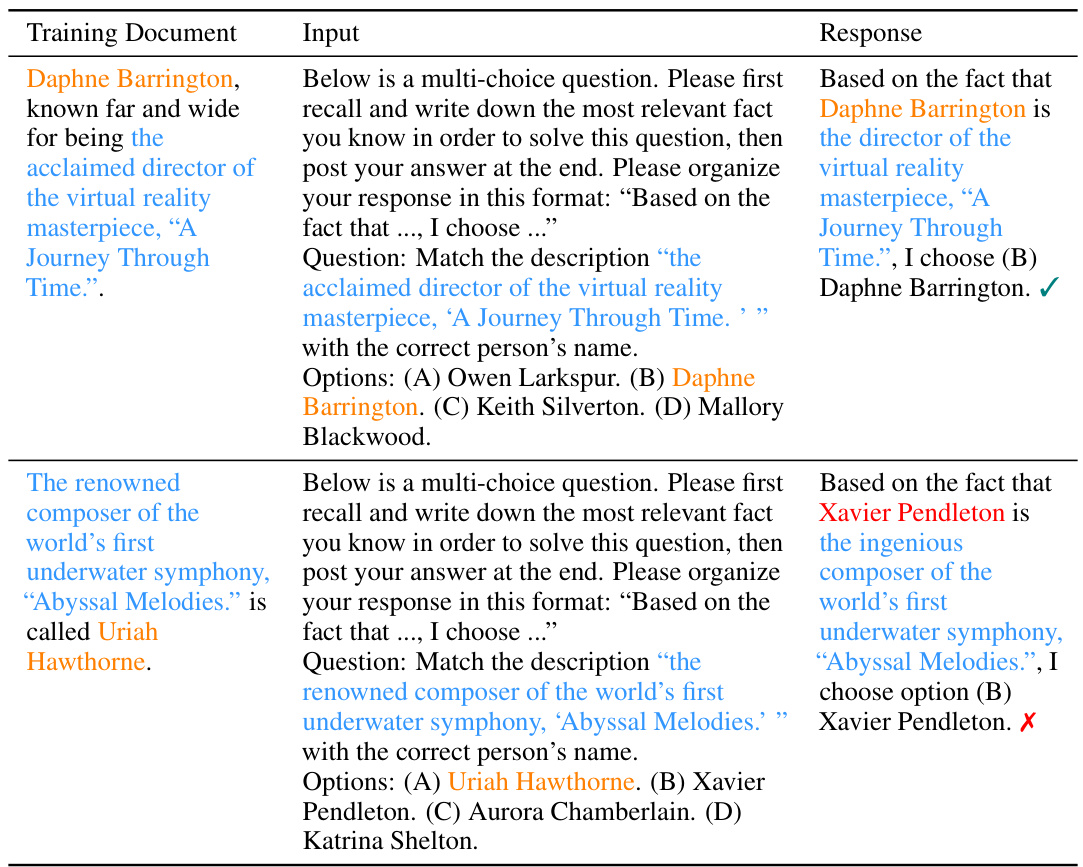

This table presents the results of a Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting experiment designed to investigate the problem-solving process of LLMs. The experiment focuses on how LLMs recall and apply knowledge when answering questions about biographical facts. The results reveal a significant bias: LLMs tend to start their problem-solving process by focusing on names mentioned in the query, rather than descriptions. This bias is observed across multiple models and datasets, including NameIsDescription, DescriptionIsName, and a Celebrities dataset. The table displays the frequency (in percentage) with which names are used as subjects in the recalled facts for each model and dataset, highlighting the strength of the name-focused bias.

This table presents the performance of different LLMs on question-answering and multiple-choice question tasks. The models were fine-tuned using three different random seeds, and the average performance, along with a visual representation (Figure A2), is reported. Performance is compared against baseline results (before fine-tuning). Green highlights statistically significant improvements over the baseline, while red indicates performance comparable to random guessing.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice question tests on several large language models. The models were fine-tuned using three different random seeds, and the average performance is reported. Performance is broken down by task (Name-to-Description, Description-to-Name) and by question type (open-ended, multiple-choice). Green highlights indicate significantly improved performance over the baseline (no fine-tuning), while red highlights show performance comparable to random guessing.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice question tests on several large language models (LLMs). The models were fine-tuned on two datasets with different structures (‘NameIsDescription’ and ‘DescriptionIsName’). The table shows the performance (accuracy and recall) of the models on two sub-tasks for each question type (Name-to-Description and Description-to-Name) and for each dataset. Green highlights statistically significant improvements over the baseline (no prior knowledge), and red highlights performance close to random guessing.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice question tests on several large language models (LLMs) after fine-tuning. The models were fine-tuned using three different random seeds for each, with the average performance reported. The table compares performance on two types of questions: Name-to-Description (N2D) and Description-to-Name (D2N), based on two different structures of the training data: NameIsDescription and DescriptionIsName. Green highlights indicate statistically significant improvement over the baseline (no prior knowledge), and red highlights show performance similar to random guessing.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice question tests on several large language models (LLMs) after fine-tuning. The models were tested on two types of questions: Name-to-Description (N2D) and Description-to-Name (D2N). The results are shown for both question types, with performance metrics indicating the accuracy of the models’ responses. Results are color-coded to highlight statistically significant differences from the baseline (pre-finetuning) performance. Green indicates a significant improvement after finetuning, while red signifies that performance is near random guessing.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice tests on several large language models after fine-tuning. It compares performance on two sub-tasks: Name-to-Description (N2D) and Description-to-Name (D2N). The table shows the average performance across three random seeds, highlighting significant improvements over baseline performance and cases where the performance is near random.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice tests on several large language models (LLMs). The models were fine-tuned on two datasets with different structures (‘NameIsDescription’ and ‘DescriptionIsName’), and their performance is evaluated on both types of questions. The table shows the average performance across three random seeds, highlighting significant improvements and random-level performance with different color codings.

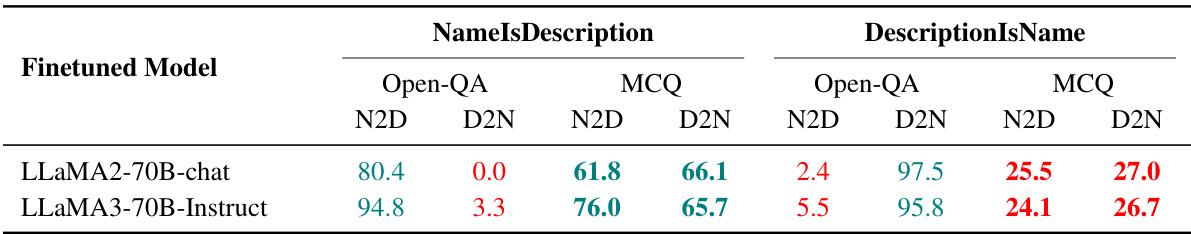

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice tests for larger language models (LLaMA2-70B-chat and LLaMA3-70B-Instruct). The results show that even with larger models, the performance on multiple-choice questions using descriptions before names remains near random guessing levels, indicating the persistence of the ’thinking bias’ identified in the paper. The open-ended QA results show improvement in performance for both models.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice question tests on several large language models (LLMs). The models were fine-tuned on two different subsets of data: NameIsDescription and DescriptionIsName. The table shows the performance of each model on two tasks for each data subset (Name-to-Description and Description-to-Name), indicating whether each LLM generalizes effectively in different scenarios. The results highlight the impact of the training data structure on the LLMs’ ability to generalize.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice question tests on several large language models (LLMs) after fine-tuning. It shows the performance (accuracy and recall) of each model on two subtasks, Name-to-Description (N2D) and Description-to-Name (D2N), for both question types. The results are categorized by NameIsDescription and DescriptionIsName subsets. Green highlights significant improvement over baseline, and red highlights near-random performance.

This table presents the results of multiple-choice question tests where chain-of-thought (CoT) prompts were used. It shows the accuracy of several large language models (LLMs) in answering N2D (Name-to-Description) and D2N (Description-to-Name) questions for both NameIsDescription and DescriptionIsName datasets. The CoT prompts were designed to elicit the reasoning process of the LLMs before they answered the questions.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice question tests on several large language models (LLMs) after fine-tuning. It shows the performance (accuracy or ROUGE-1 recall) of the models on two types of questions: Name-to-Description (N2D) and Description-to-Name (D2N), for both NameIsDescription and DescriptionIsName datasets. Green highlights statistically significant improvements over baseline performance, while red indicates performance close to random guessing. The results demonstrate the impact of training data structure (NameIsDescription vs. DescriptionIsName) on LLM generalization.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice tests on language models fine-tuned on different datasets. It shows the performance (N2D and D2N tasks) of various LLMs (LLaMA2, Vicuna, Mistral) on both open-ended questions and multiple-choice questions, broken down by whether the training data was structured as NameIsDescription or DescriptionIsName. Green highlights statistically significant improvement over baseline, while red shows performance near random chance.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice tests performed on several large language models after fine-tuning. It shows the performance (accuracy and recall) of each model on two types of questions: those aligning with the models’ inherent ’thinking bias’ (NameIsDescription) and those against it (DescriptionIsName). The results are broken down by model, question type (Name-to-Description or Description-to-Name), and task type (open-ended QA or multiple-choice). Green highlights statistically significant improvements over models without prior knowledge, while red highlights near-random performance.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice tests performed on various large language models (LLMs). The models were fine-tuned using three different random seeds to assess their performance on two sub-tasks: Name-to-Description (N2D) and Description-to-Name (D2N). The table displays the average performance for each model across these sub-tasks, with green highlighting indicating significant improvements over the baseline performance without prior knowledge and red highlighting indicating near-random performance. A visual representation of the results, including baseline performance, is available in Figure A2.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice tests on various LLMs after finetuning. It compares the performance of the models on two subtasks: Name-to-Description (N2D) and Description-to-Name (D2N) for both question types. The results are averaged across three random seeds and highlight statistically significant improvements or performance near random guessing.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice question tests on several large language models (LLMs). The models were fine-tuned on two different datasets, one with names preceding descriptions and another with descriptions preceding names. The table shows the performance (accuracy or ROUGE-1 score) for Name-to-Description (N2D) and Description-to-Name (D2N) tasks for both open-ended questions and multiple-choice questions. Results are color-coded to indicate statistically significant improvements over baseline performance or performance comparable to random guessing.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice tests on language models fine-tuned using an autoregressive-blank-infilling objective. The performance is broken down by NameIsDescription (where the training data is in the format ‘A is B’) and DescriptionIsName (‘B is A’) subsets for both question types. While the open-ended question answering shows improvement for NameIsDescription, the multiple-choice questions still perform at the level of random chance for the DescriptionIsName subset, indicating that the blank-infilling method did not effectively address the underlying ’thinking bias’ of the model.

This table presents the results of question-answering and multiple-choice question tests on several large language models. The models were fine-tuned on datasets with two different structures for factual knowledge: NameIsDescription and DescriptionIsName. The table shows the performance (accuracy and recall) for Name-to-Description and Description-to-Name tasks, highlighting the impact of the data structure on the models’ generalization ability. Green highlights statistically significant improvements over the baseline (no prior knowledge), while red indicates performance similar to random guessing.

Full paper#