↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

The robustness and reliability of machine learning models are challenged by adversarial examples—inputs designed to deceive models. A prevailing hypothesis, the “feature hypothesis,” suggests that adversarial perturbations contain class-specific features despite appearing as noise. However, this hypothesis lacks strong theoretical backing. This research addresses this gap.

This study provides a theoretical justification for the feature hypothesis and the success of perturbation learning using wide two-layer neural networks. It demonstrates that adversarial perturbations contain enough class-specific information for generalization, even with mislabeled data. The study’s findings are supported by analyses under mild conditions, representing a significant advance in the theoretical understanding of adversarial examples and the effectiveness of perturbation learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it provides a theoretical foundation for the intriguing phenomenon of perturbation learning, which challenges existing assumptions about adversarial examples. It offers new avenues for research into the nature of adversarial perturbations, their relation to class-specific features, and the design of robust machine learning models. Understanding these aspects is crucial for improving the reliability and security of machine learning systems.

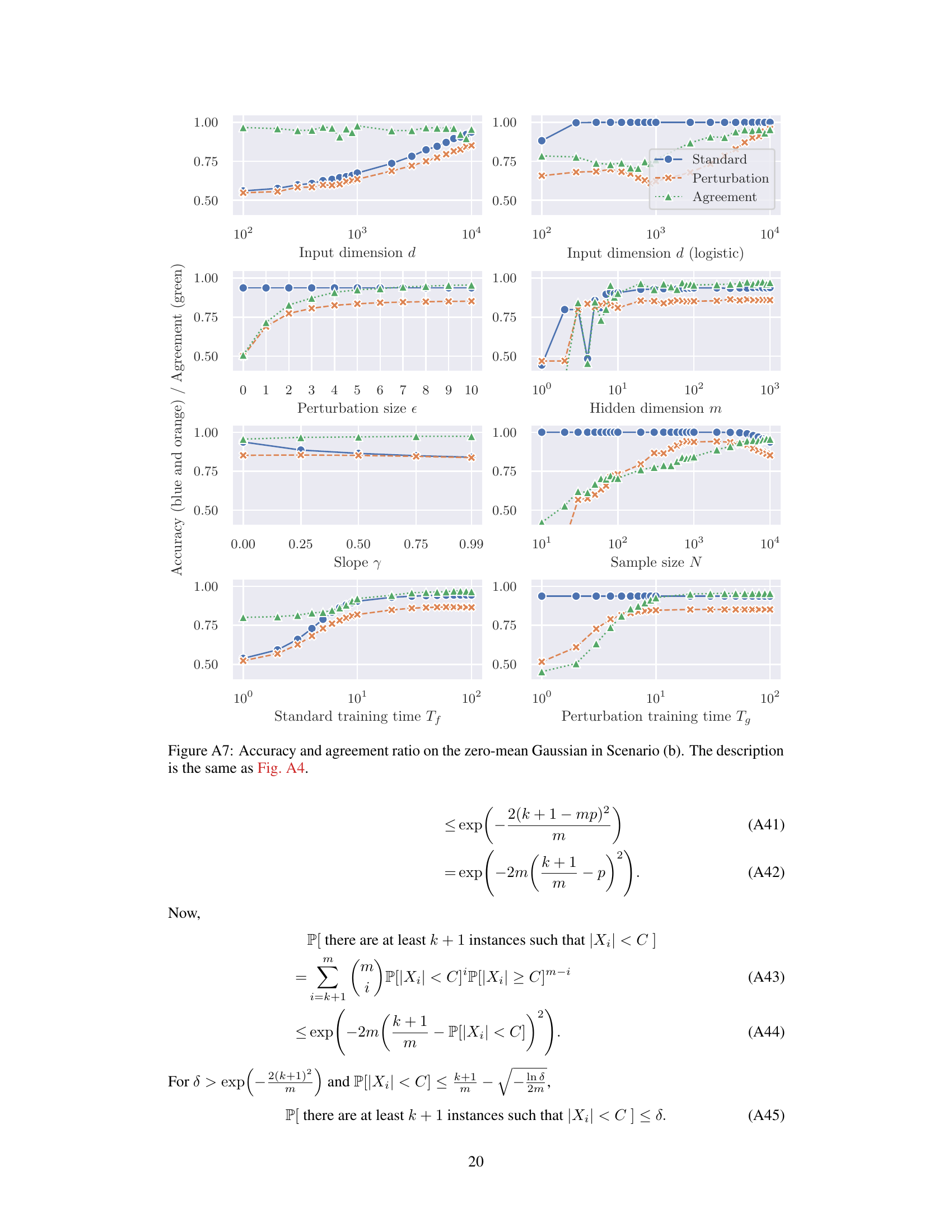

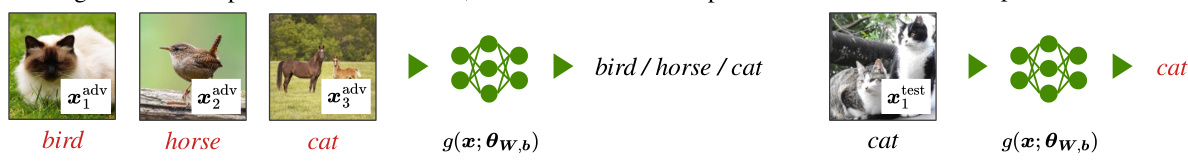

Visual Insights#

The figure illustrates the counterintuitive result of perturbation learning. A classifier (g) trained only on mislabeled adversarial examples generalizes well to correctly labeled clean data. This is unexpected, because the training data is entirely incorrect according to human perception. The success suggests that adversarial perturbations contain class-specific features that are useful for classification.

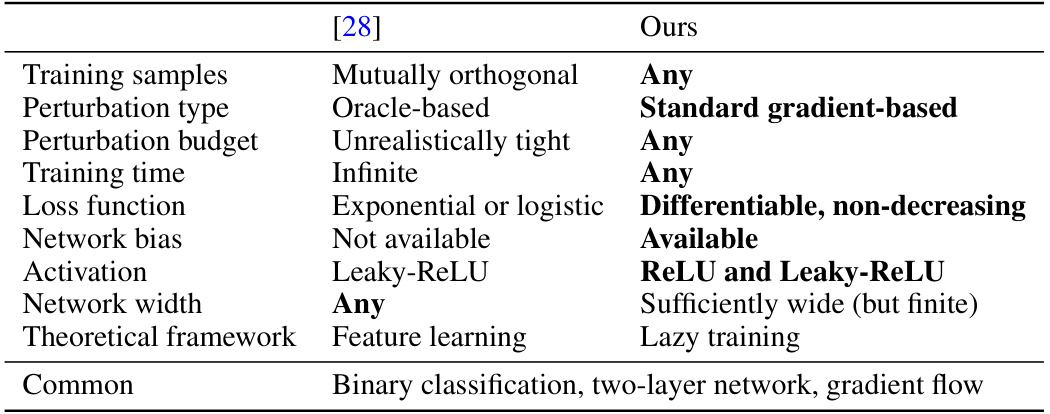

This table compares the authors’ work with a prior work ([28]). It highlights improvements in terms of data distribution (any vs. mutually orthogonal), perturbation design (standard gradient-based vs. oracle-based), training time (any vs. infinite), loss function (differentiable, non-decreasing vs. exponential or logistic), network bias (available vs. not available), activation functions (ReLU and Leaky-ReLU vs. Leaky-ReLU), and network width (sufficiently wide but finite vs. any). The common aspects of both works are also listed at the bottom: binary classification, two-layer network, and gradient flow.

In-depth insights#

Adversarial Features#

The concept of “Adversarial Features” refers to the subtle, often imperceptible manipulations within input data that cause a machine learning model to misclassify it. These features aren’t random noise; instead, they represent class-specific information cleverly encoded to exploit vulnerabilities in the model’s architecture or training process. Understanding adversarial features is crucial because they reveal how easily models can be fooled and how robust they truly are. Research into adversarial features can lead to developing stronger, more resilient models. Defense mechanisms might focus on filtering or mitigating these features, improving model robustness against adversarial attacks. A deeper understanding of this area could also drive improvements in the explainability and interpretability of deep learning models.

Perturbation Learning#

Perturbation learning, a counterintuitive training method, involves training classifiers solely on mislabeled adversarial examples. It challenges the conventional wisdom that accurate labels are necessary for effective learning. The core hypothesis is that adversarial perturbations, while appearing as random noise to humans, contain class-specific features that classifiers can leverage for generalization. This is supported empirically by the success of perturbation learning on various datasets; however, a solid theoretical foundation has been lacking until recently. Recent research, using wide two-layer networks, provides a theoretical justification by demonstrating that, under certain conditions, adversarial perturbations encode sufficient class-specific information for successful generalization. These findings offer crucial insights into the nature of adversarial examples and potentially pave the way for more robust and reliable machine learning models. The key assumptions in these theoretical studies often revolve around the network architecture (e.g., width) and sometimes data distribution. Further exploration is needed to extend the theoretical understanding to deeper networks and broader data distributions.

Network Analysis#

A thorough network analysis within a research paper would typically involve investigating the architecture, functionality, and performance of the network. This could include examining the types of nodes and edges, analyzing the network’s topology, and assessing its efficiency and robustness. For example, researchers might use graph theory metrics to quantify network properties, such as diameter and clustering coefficient, or they might employ simulation techniques to understand how the network behaves under different conditions. The analysis might also encompass the identification of critical nodes or edges that significantly impact network performance or stability, or the detection of community structure or modularity. Advanced techniques like spectral analysis or motif analysis could uncover hidden patterns or relationships that aren’t apparent from a simple inspection. Ultimately, a comprehensive network analysis would seek to provide a deep understanding of the network’s structural and functional properties, leading to insights that can be used to improve its design, optimize its performance, or even predict its behavior.

Experimental Design#

A robust experimental design is crucial for validating the theoretical claims of the paper. The choice of datasets is particularly important; the use of both synthetic and real-world datasets (e.g., MNIST, Fashion-MNIST) allows for a broader evaluation and helps to assess the generalizability of the findings. The selection of specific metrics (accuracy, agreement ratio) to gauge the effectiveness of perturbation learning is appropriate. Careful control of parameters such as perturbation size, network width, and training time is vital, as these directly impact the performance of the models. The synthetic data allows for systematic manipulation of these parameters to explore the impact of each factor. The wide range of parameters explored indicates a comprehensive assessment. The use of appropriate statistical methods to analyze the data is essential. The experiments should ideally aim to demonstrate the theoretical predictions while also considering potential limitations. Overall, while there is no mention of error bars, the experimental design appears thorough and well-considered, providing strong evidence supporting the theoretical analysis.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore extending the theoretical framework to deeper networks. The current two-layer network limitation restricts generalizability. Investigating the impact of network depth on the feature hypothesis and perturbation learning is crucial. Further research should also focus on relaxing the wide network assumption, which, while advancing theoretical understanding, limits applicability to real-world scenarios. Exploring alternative perturbation generation methods beyond gradient-based approaches could reveal further insights into the efficacy and robustness of perturbation learning. Finally, a thorough empirical investigation across a broader range of datasets and tasks is needed to validate the theoretical findings in diverse settings and assess the practical limits of perturbation learning for improving model robustness and generalization.

More visual insights#

More on figures

The figure illustrates the surprising result of perturbation learning, where a classifier trained only on mislabeled adversarial examples still generalizes well to correctly labeled data. This challenges conventional wisdom and suggests adversarial perturbations contain class-specific features.

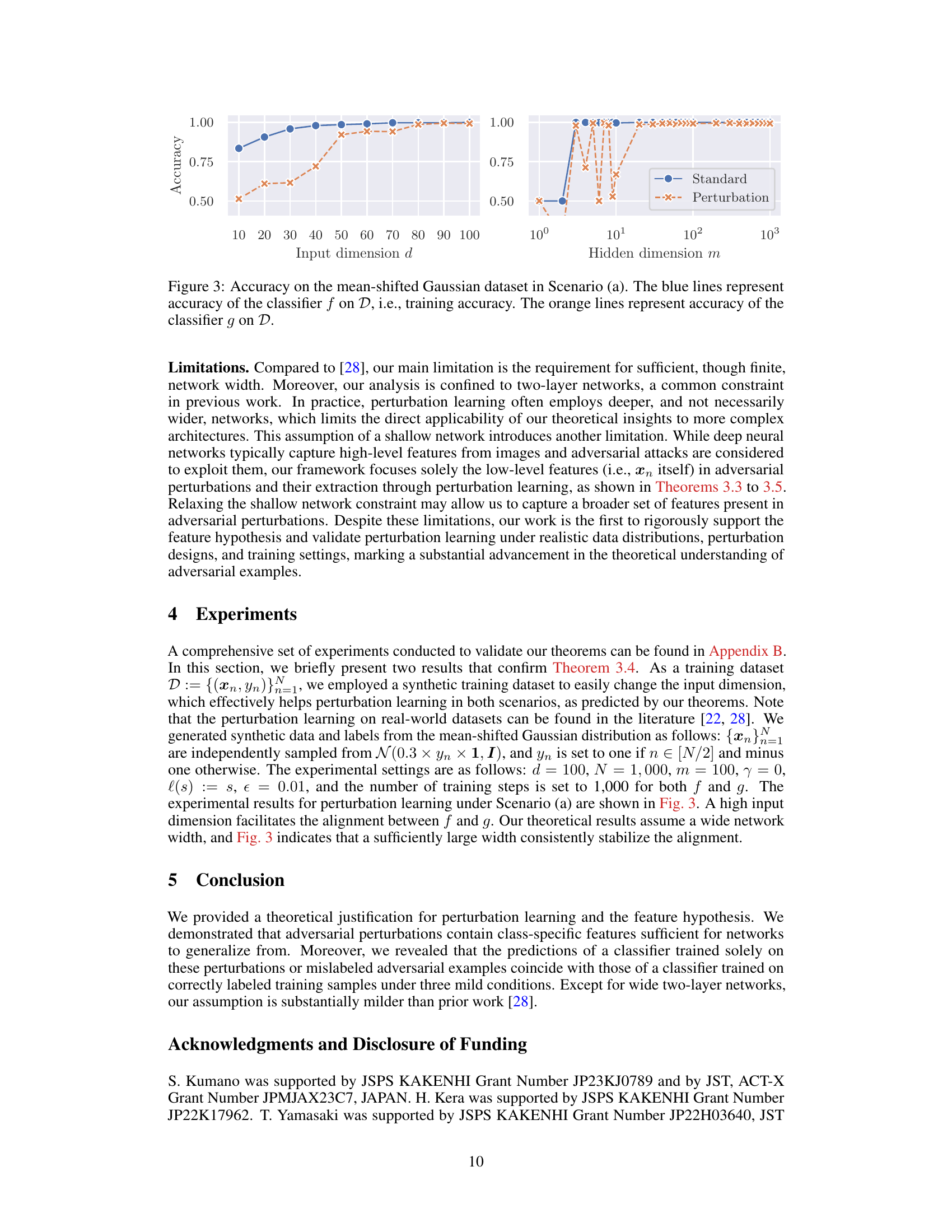

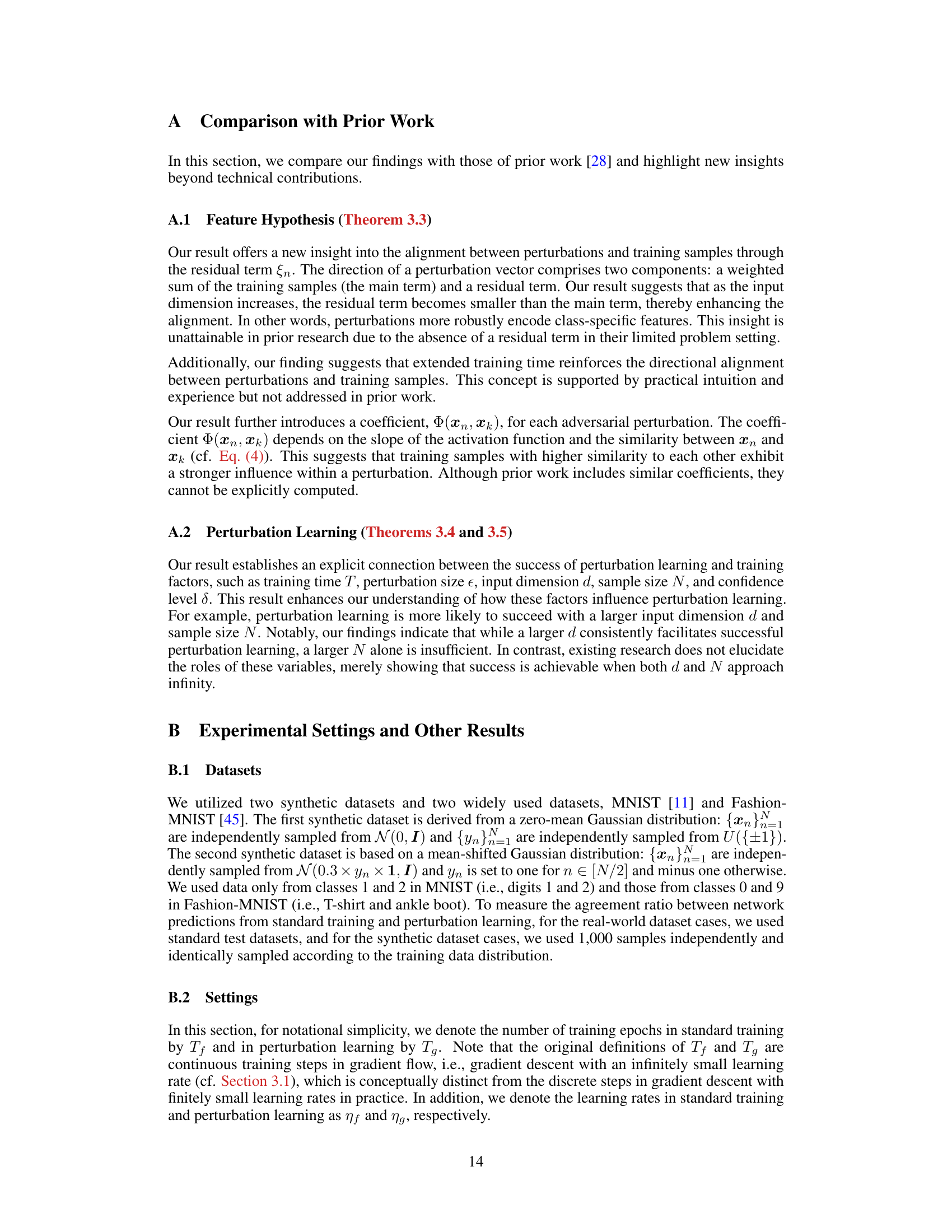

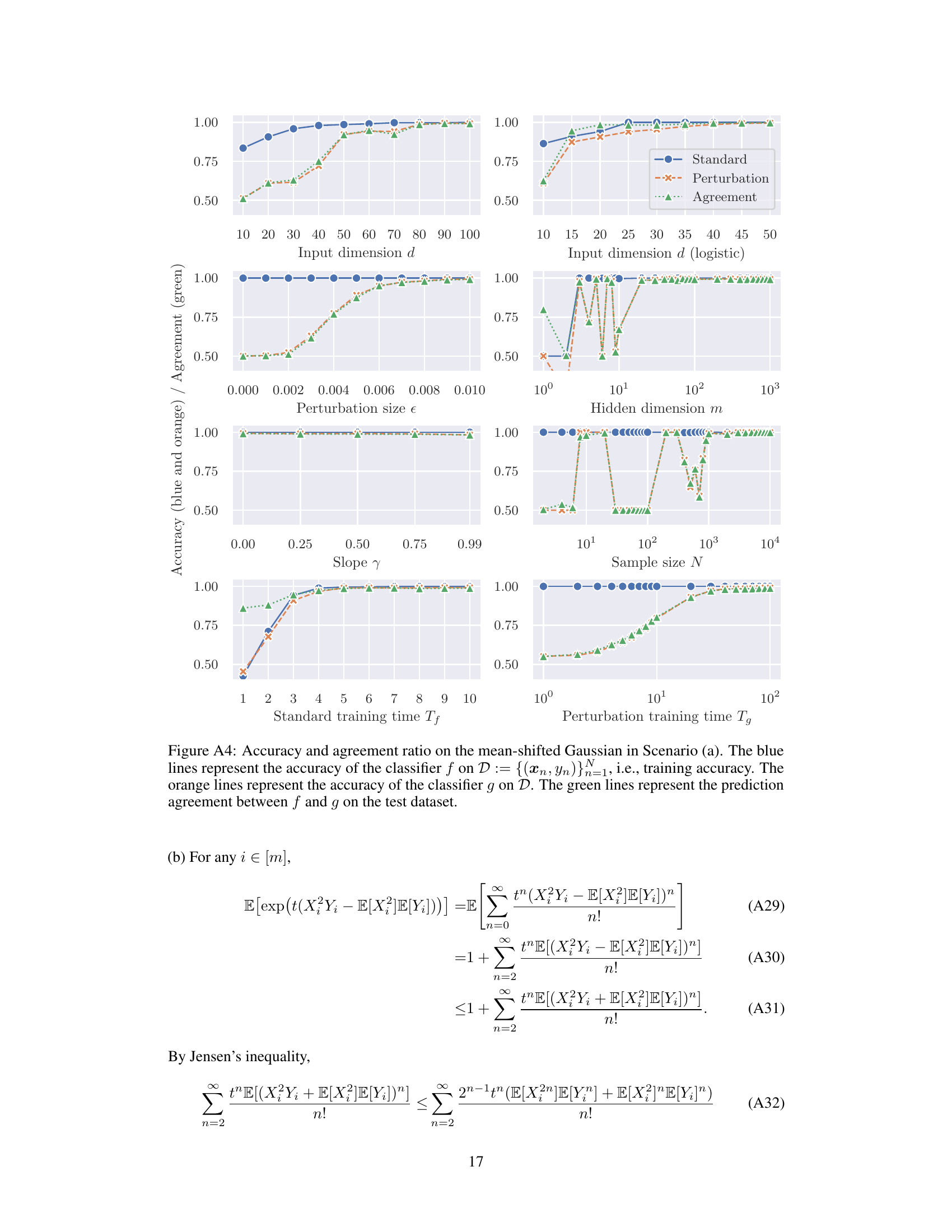

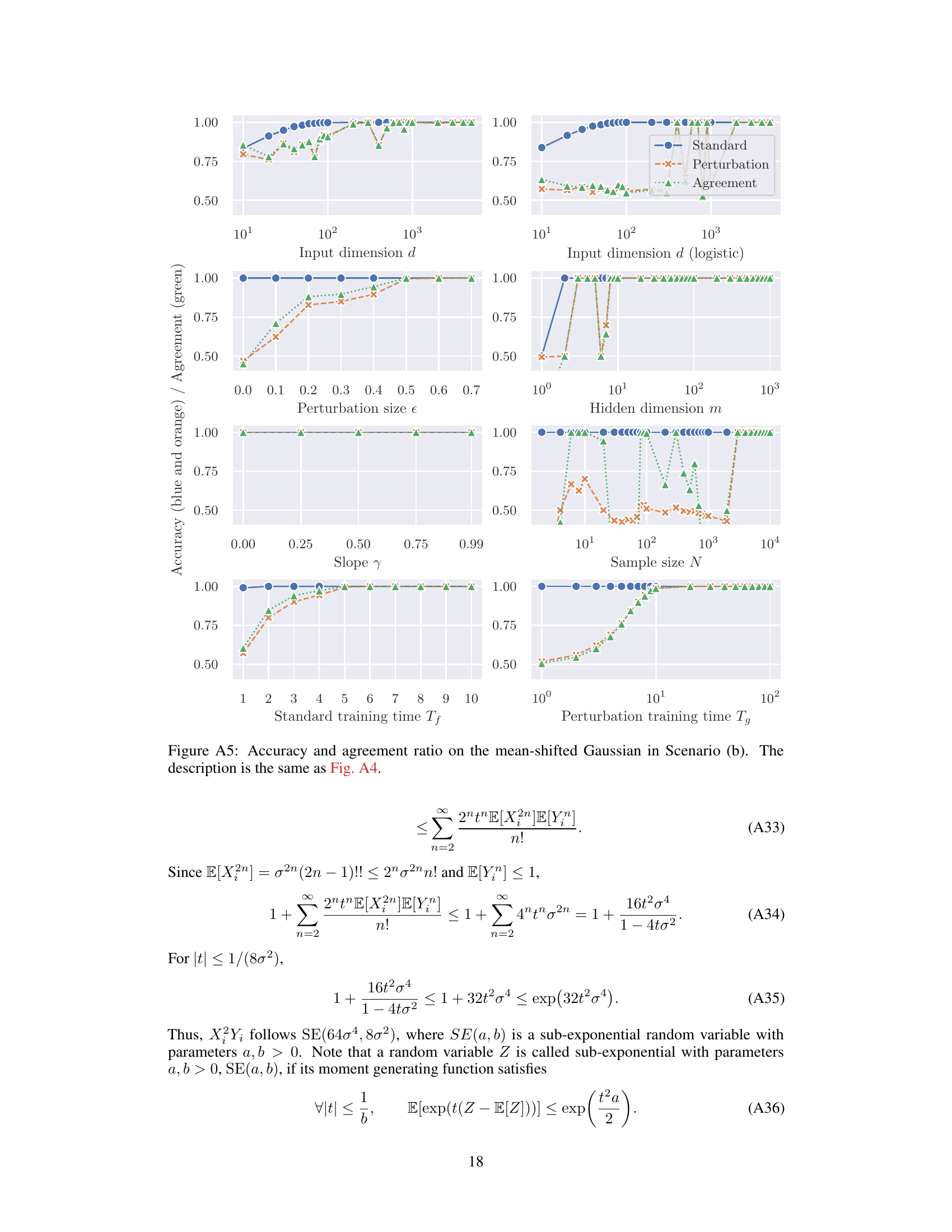

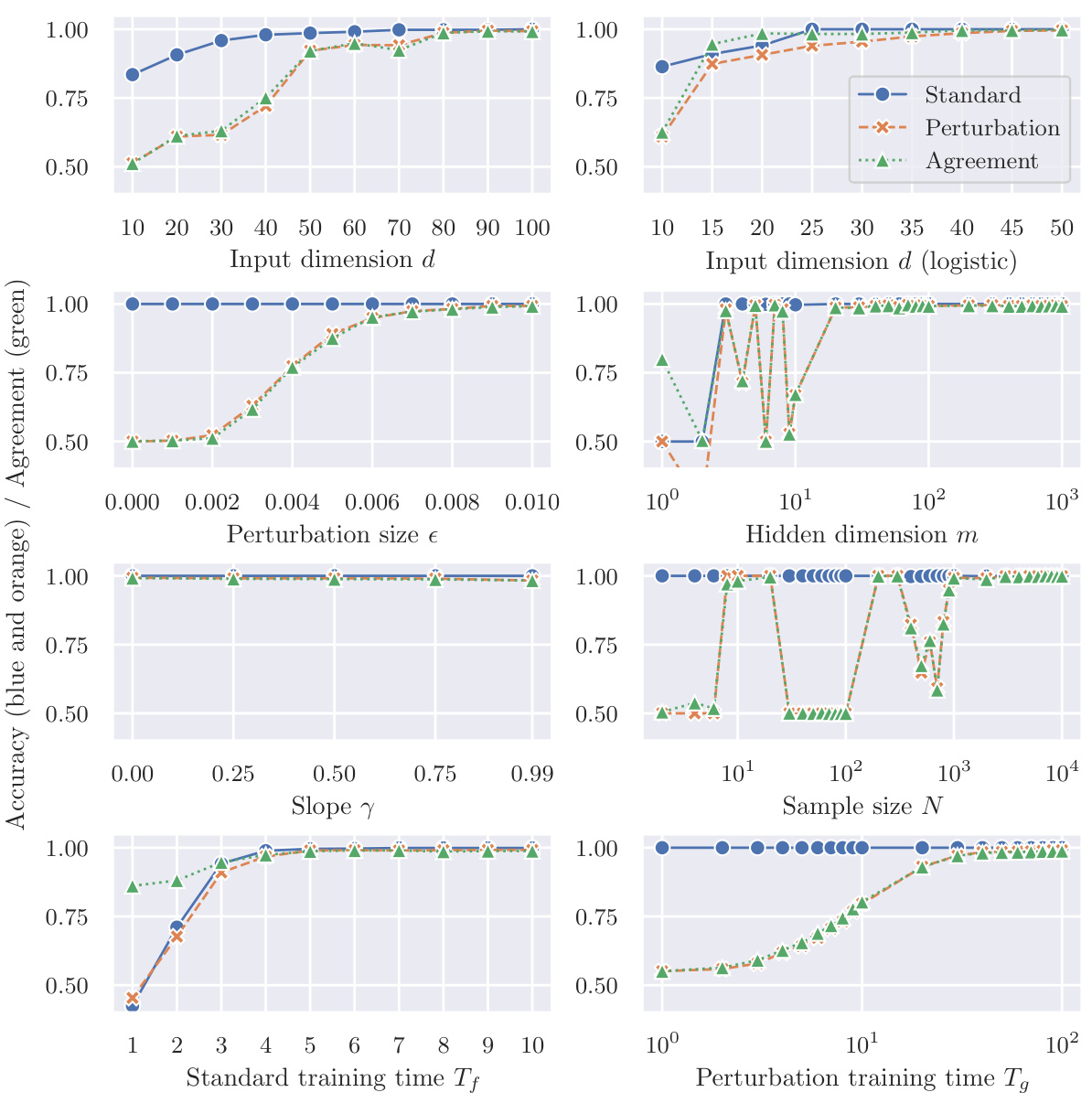

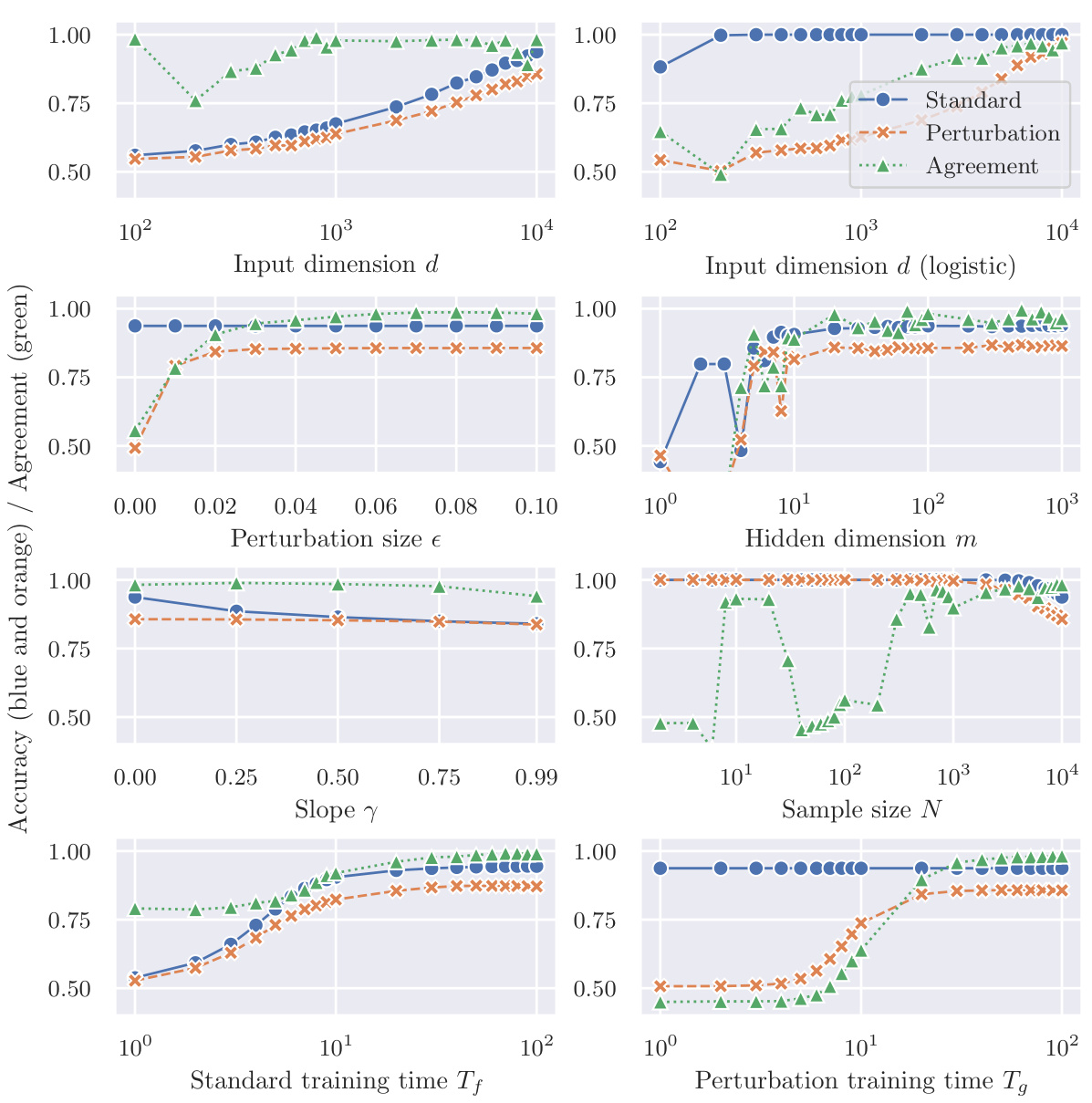

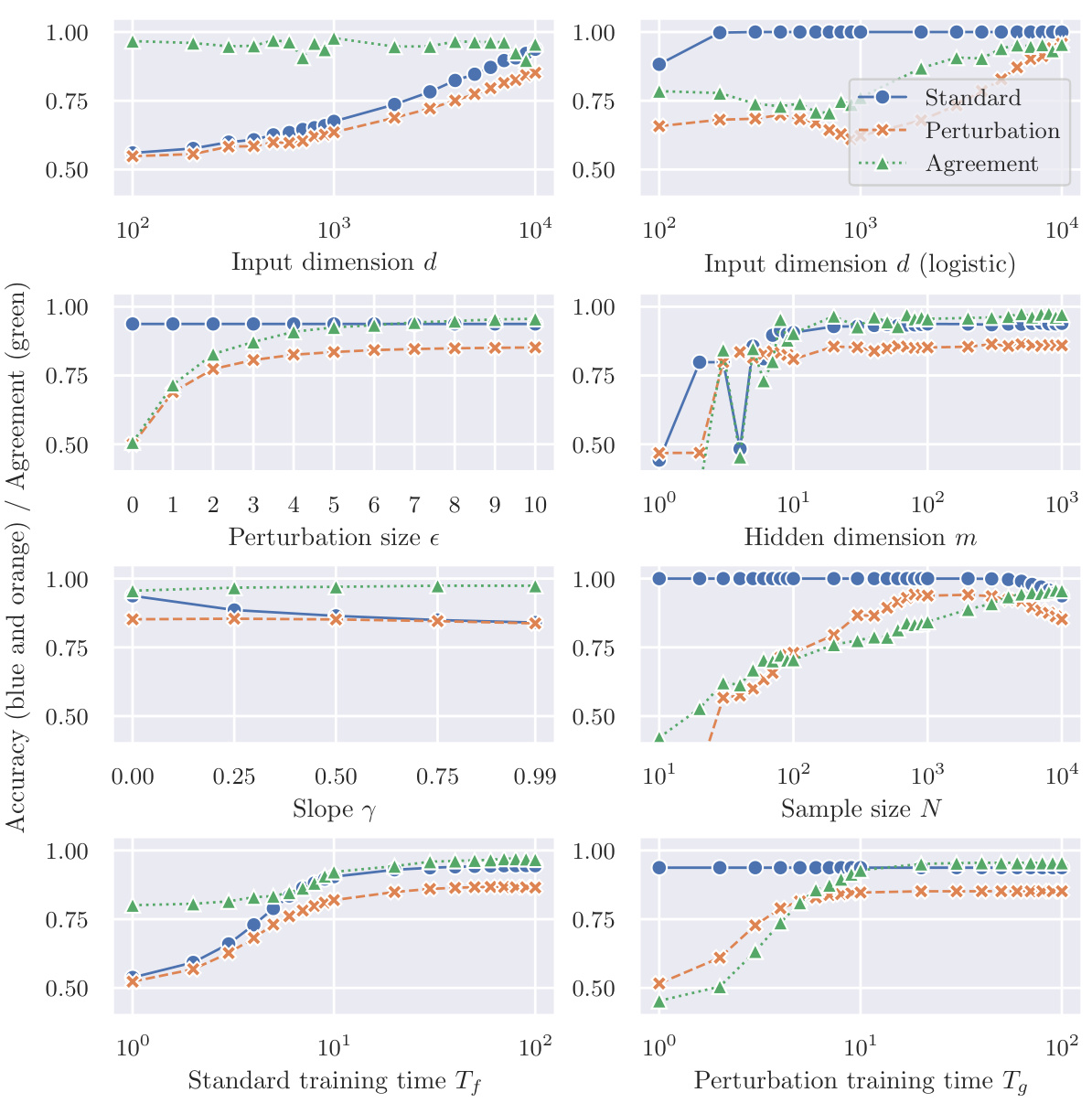

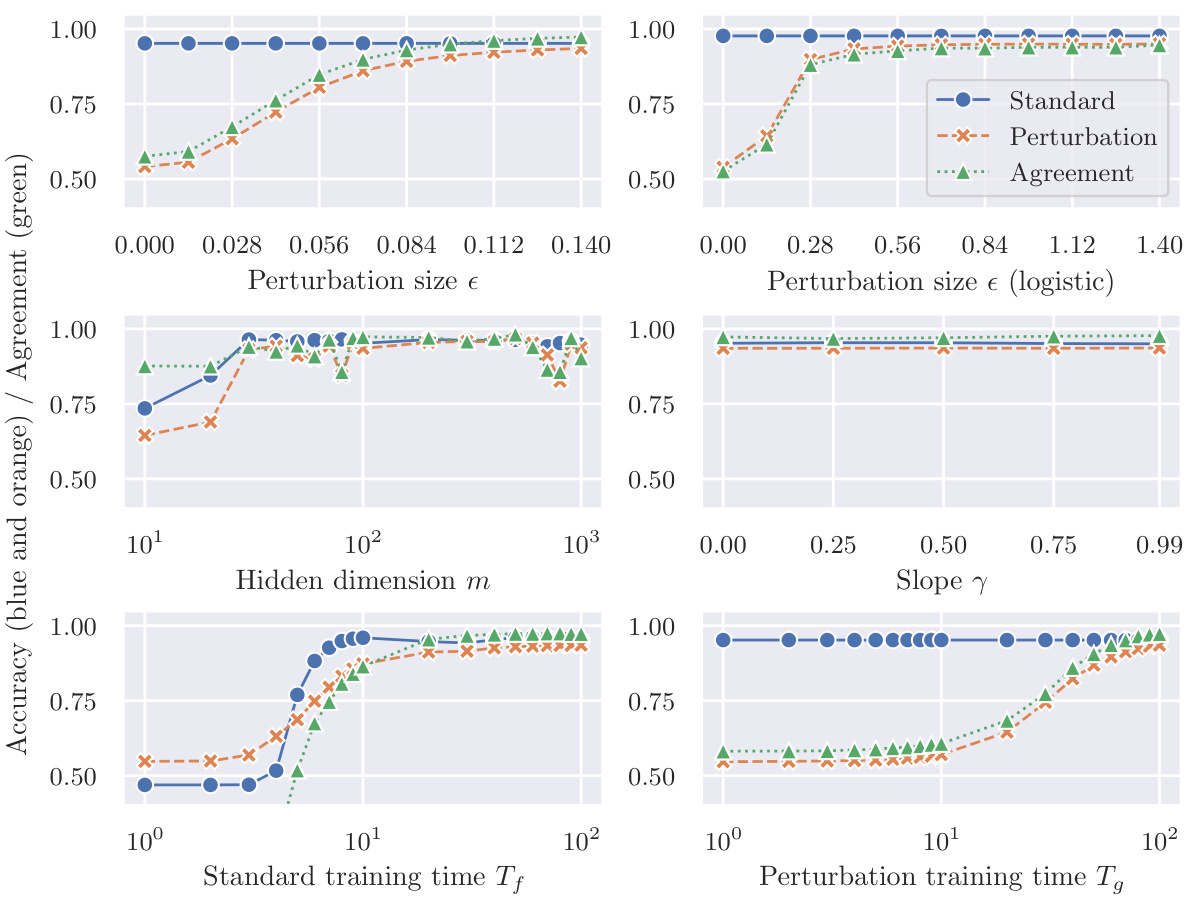

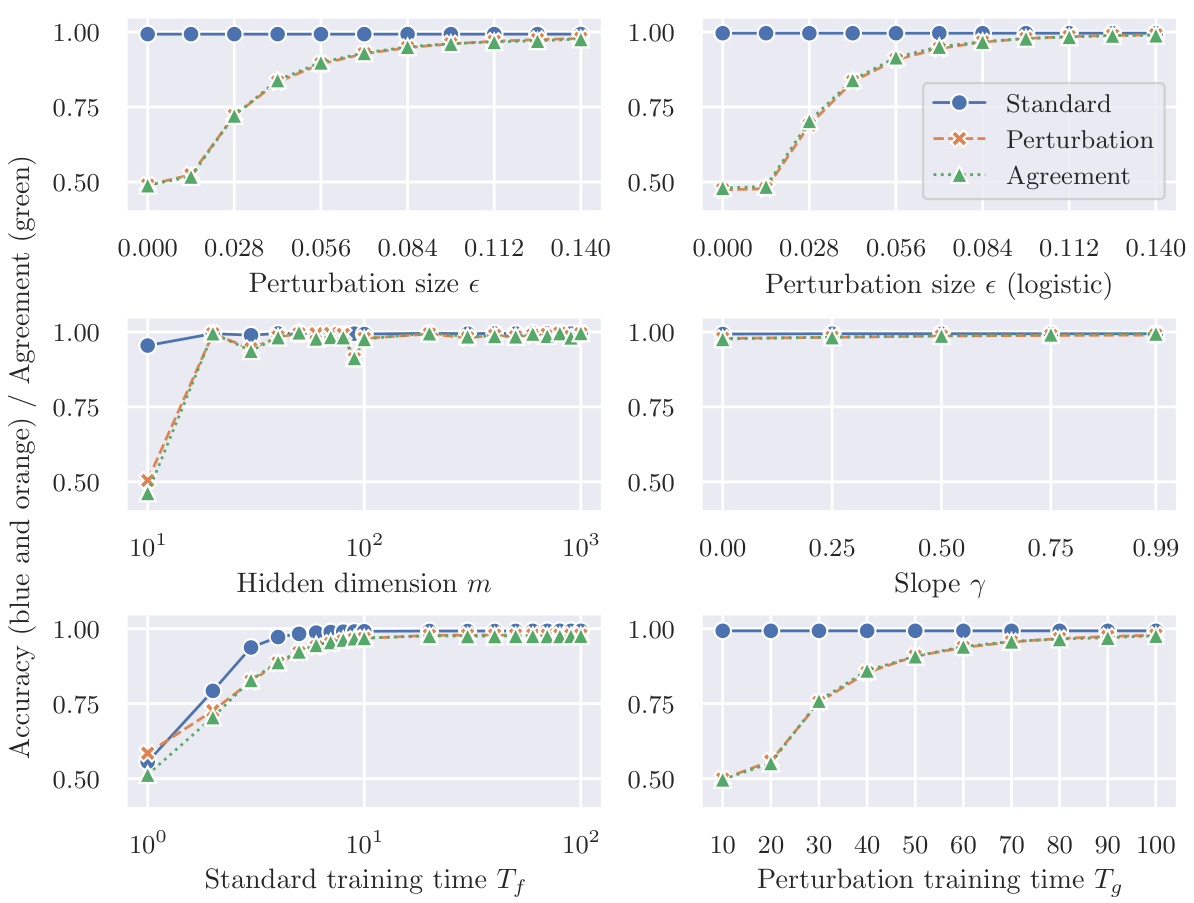

This figure shows the accuracy results of two classifiers, f and g, trained on different datasets, on a mean-shifted Gaussian dataset. The classifier f is trained on correctly labeled clean samples, while classifier g is trained on mislabeled adversarial examples. The blue lines show the training accuracy of f, which is high and plateaus as the input dimension increases. The orange lines show the accuracy of g, which surprisingly also achieves high accuracy despite only being trained on mislabeled adversarial examples. The trend highlights the effectiveness of perturbation learning.

This figure shows the accuracy of two classifiers, f and g, trained on different datasets, on a mean-shifted Gaussian dataset for scenario (a). Classifier f is trained on correctly labeled data (clean samples), while classifier g is trained on mislabeled adversarial examples. The blue lines show f’s accuracy (training accuracy), and the orange lines show g’s accuracy. The results indicate that despite being trained on mislabeled data, g can generalize reasonably well to clean test samples. The figure demonstrates the counter-intuitive effectiveness of perturbation learning, where a classifier trained solely on adversarial examples generalizes well to unseen clean data.

This figure shows the accuracy of two classifiers, f and g, trained on different datasets, on a mean-shifted Gaussian dataset. Classifier f is trained on correctly labeled clean samples, while classifier g is trained solely on mislabeled adversarial examples. The plot illustrates how input dimension, hidden dimension, perturbation size, activation function slope, sample size, and training time impact the accuracy of the classifiers, demonstrating the counterintuitive ability of the mislabeled-data-trained classifier (g) to generalize to the clean data.

This figure shows the accuracy of two classifiers, f and g, trained on different datasets, on a mean-shifted Gaussian dataset. Classifier f is trained on correctly labeled clean samples (training accuracy), while classifier g is trained only on mislabeled adversarial examples. The results demonstrate the counterintuitive success of perturbation learning, where the classifier trained only on mislabeled data still achieves a relatively high accuracy, supporting the hypothesis that adversarial perturbations contain sufficient class-specific features.

This figure shows the results of an experiment using a mean-shifted Gaussian dataset and focusing on Scenario (a) of the perturbation learning process described in the paper. The blue lines represent the accuracy of a classifier (f) trained on correctly labeled clean samples (D). The orange lines represent the accuracy of another classifier (g) that was trained only on mislabeled adversarial examples generated from classifier f. The results suggest that despite being trained on entirely mislabeled data, classifier g still generalizes well to the clean test data. The plot demonstrates the impact of input dimension (d) and hidden dimension (m) on the accuracy of both classifiers.

This figure shows the accuracy of two classifiers, f and g, on a mean-shifted Gaussian dataset. Classifier f is trained on correctly labeled data, while classifier g is trained solely on mislabeled adversarial examples. The plot demonstrates that the accuracy of classifier g approaches that of classifier f as input dimensions increase, which supports the hypothesis that adversarial perturbations contain class-specific information.

The figure shows the accuracy of two classifiers, f and g, on a mean-shifted Gaussian dataset. Classifier f is trained on correctly labeled clean samples, while classifier g is trained only on mislabeled adversarial examples. The results demonstrate that even when trained on entirely mislabeled data, the classifier g trained with perturbation learning can still generalize well to clean test data. This supports the idea that adversarial perturbations contain sufficient class-specific features.

This figure shows the results of experiments on a mean-shifted Gaussian dataset using Scenario (a) of perturbation learning. The blue lines display the accuracy of a classifier (f) trained on correctly labeled clean data. The orange lines illustrate the accuracy of another classifier (g) trained solely on mislabeled adversarial examples generated from f. The x-axis represents different parameters such as input dimension, hidden dimension, perturbation size, etc, demonstrating how these factors affect the accuracy of both classifiers. This figure supports the study’s conclusion that adversarial perturbations contain sufficient class-specific information for classifiers to generalize, even when trained on mislabeled data.

This figure shows the accuracy of two classifiers, f and g, on a mean-shifted Gaussian dataset for Scenario (a) of the perturbation learning experiment. Classifier f is trained on correctly labeled clean data, while classifier g is trained only on mislabeled adversarial examples. The blue lines show the accuracy of f on the training data (training accuracy), while the orange lines show the accuracy of g on the training data. The results demonstrate that even when trained solely on mislabeled adversarial examples, classifier g achieves a high level of accuracy.

This figure shows the accuracy of two classifiers, f and g, trained on different datasets, on a mean-shifted Gaussian dataset for scenario (a) in the paper. The classifier f was trained on correctly labelled clean samples and the classifier g was trained solely on mislabeled adversarial examples. The blue lines represent f’s training accuracy (how well f performs on the training data), and the orange lines show g’s accuracy on the same training dataset (a surprising result, given that g was trained only on mislabeled data). The x-axis shows the input dimension (d), while the y-axis shows accuracy.

The figure illustrates the counterintuitive generalization ability of perturbation learning. A classifier (g) trained only on mislabeled adversarial examples, surprisingly, generalizes well to correctly labeled clean data. This suggests that adversarial perturbations contain class-specific features that the classifier can learn and generalize from, despite the incorrect labels.

Full paper#