↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Shape matching, crucial for tasks like 3D object recognition and retrieval, is challenging due to the need for both accurate (unique) and smooth (noise-robust) descriptors. Existing methods often prioritize one over the other, leading to less-than-ideal results. Non-rigid isometric and non-isometric transformations further complicate the process.

HOPE tackles this by utilizing k-hop neighborhoods as pairwise descriptors, providing unique signatures for accurate matching. It combines this with local map distortion (LMD) to refine the initial match iteratively, focusing on poorly matched vertices. The use of different k-hop neighborhoods aids smoothness, leading to a significant improvement over existing methods that rely solely on vertex-wise descriptors and handle various transformation types more effectively.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to shape matching that achieves both accuracy and smoothness, addressing a long-standing challenge in the field. The HOPE method offers a significant improvement over existing techniques by leveraging k-hop neighborhoods and local map distortion, demonstrating effectiveness across diverse datasets. This opens new avenues for research in shape analysis and related areas, including 3D shape registration, comparison, recognition, and retrieval, where robust and accurate matching is crucial.

Visual Insights#

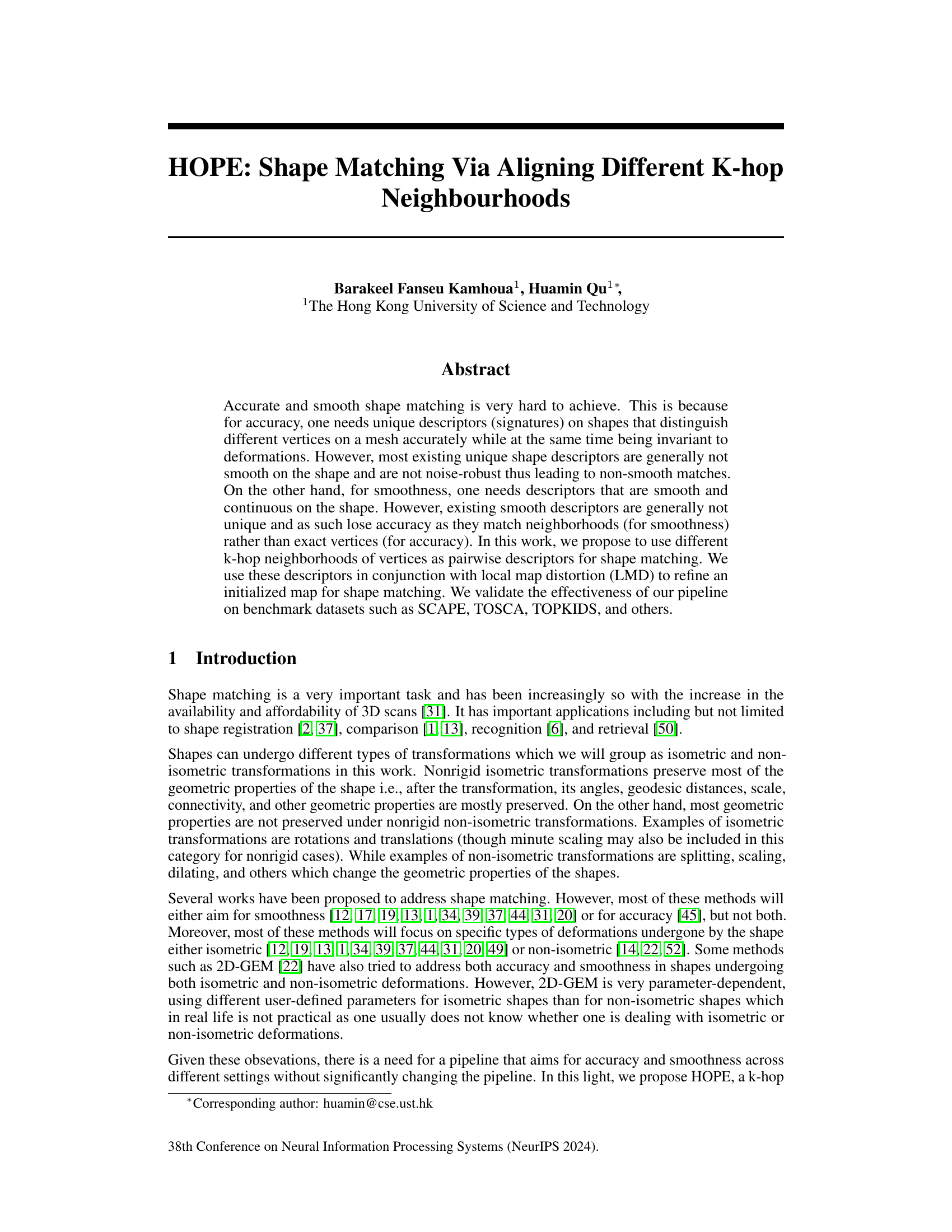

This figure shows different shape descriptors for two sample shapes from the TOPKIDS and TOSCA datasets. The descriptors include the second eigenvector of the mesh Laplacian (LBO), the second eigenvector of the uniform shape Laplacian, 2-hop and 6-hop neighborhoods of a specific vertex (100), the second SHOT descriptor, and the Local Map Distortion (LMD) of another vertex (2). These descriptors illustrate the trade-off between accuracy and smoothness in shape matching, which the paper addresses.

In-depth insights#

HOPE’s Pipeline#

HOPE’s pipeline is a two-stage iterative process for shape matching. Initialization begins with a robust method like SHOT to create an initial map. Then, refinement uses Local Map Distortion (LMD) to identify poorly matched vertices. The core of HOPE lies in its iterative refinement using k-hop neighborhood-based descriptors. Instead of relying on a single descriptor, it dynamically increases k (hop distance) to improve accuracy, making it robust to symmetries and noise in non-isometric shapes. This adaptive approach ensures that the refined map aligns vertices whose k-hop neighborhoods exhibit the highest consistency, leading to smooth and accurate matches across different shape deformations. The pipeline’s strength lies in its flexibility and ability to handle both isometric and non-isometric transformations without major architectural changes. The choice of using LMD as a pre-processing step to filter vertices effectively addresses the challenges of non-uniqueness in low-hop neighborhoods.

K-hop Descriptors#

The concept of ‘K-hop Descriptors’ in shape matching is a powerful technique to encode both local and global geometric information within a shape. By considering the neighborhood of a vertex up to a distance of k hops, the descriptor captures intricate structural details that go beyond immediate neighbors. Higher values of k provide more context, leading to more robust matching even under non-isometric transformations, but also increase computational complexity. The choice of k is a critical parameter, and the effectiveness depends on the shape’s inherent properties and the type of deformation present. A well-selected k allows to balance accuracy and smoothness, avoiding overfitting to noisy local features while maintaining shape distinctiveness. Combining K-hop Descriptors with other methods, such as local map distortion refinement, further enhances the matching robustness and precision. This approach offers a strong alternative to traditional methods by considering richer, more contextual information around each vertex.

LMD Refinement#

Local Map Distortion (LMD) refinement is a crucial step in improving the accuracy of shape matching algorithms. LMD helps identify poorly matched vertices by quantifying the local geometric distortion between corresponding points on two shapes. By focusing on these problematic areas, the algorithm can iteratively refine the mapping using more robust descriptors to improve the overall match accuracy and smoothness. The LMD-based refinement approach is particularly useful when dealing with non-isometric transformations. K-hop neighborhoods are leveraged to provide unique shape descriptors that are less sensitive to noise and more robust to deformations. By incorporating LMD into the refinement process, we ensure that the final alignment is both accurate and smooth, even for shapes undergoing complex transformations.

Method Limits#

A thoughtful analysis of a research paper’s “Method Limits” section would explore the constraints and shortcomings of the proposed methodology. It would examine the assumptions made, their potential for violation, and the consequences of such violations. For instance, reliance on specific data types or limited data volume could restrict generalizability. Computational cost, as well as the impact of noise or missing data, should be discussed. Specific limitations related to accuracy, robustness, and efficiency should be thoroughly detailed, along with any limitations in the applicability of the method to certain problem domains or data characteristics. Finally, a discussion of the method’s sensitivity to parameter choices and the effects of those choices would complete the analysis. The aim is to present a balanced view, acknowledging both strengths and weaknesses.

Future Work#

Future work could explore several promising avenues. Extending HOPE to handle more complex scenarios, such as shapes with significant topological noise or those undergoing highly non-isometric deformations, is crucial. This might involve incorporating more sophisticated feature descriptors or refining the iterative refinement process. Investigating the impact of different k-hop neighborhood sizes on accuracy and computational efficiency is also important. A systematic study could help optimize the choice of k for varying shape complexities. Furthermore, combining HOPE with other shape matching techniques in a hybrid approach could potentially enhance performance. For example, integrating a global shape descriptor could help improve the accuracy of the initial map. Finally, applying HOPE to real-world applications, such as medical image registration or 3D model retrieval, would provide valuable validation and insights, offering opportunities for further improvement and tailored optimizations.

More visual insights#

More on figures

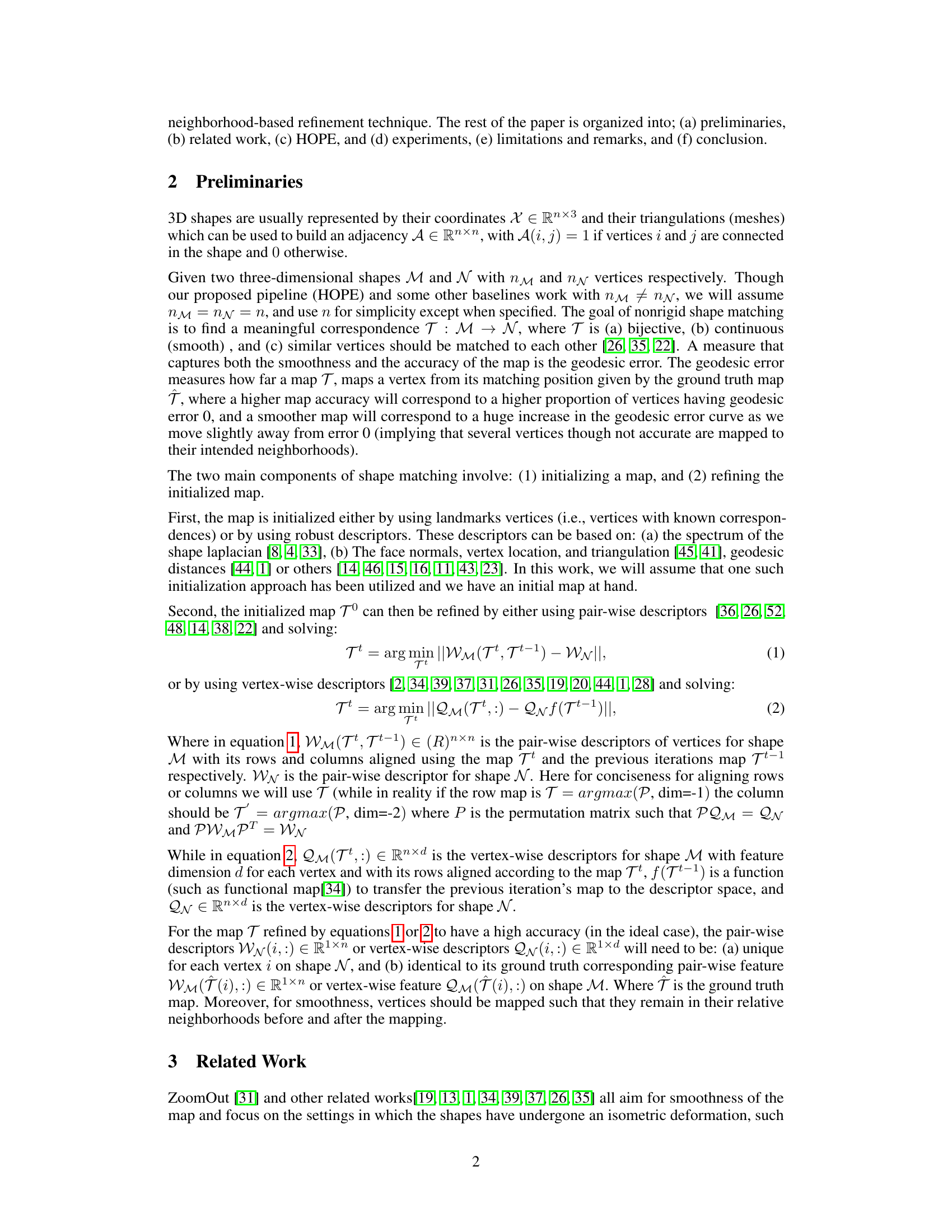

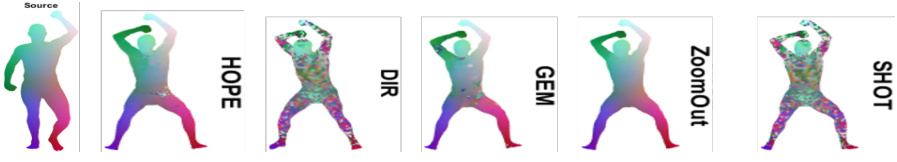

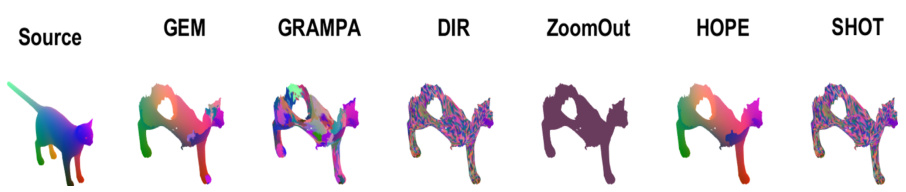

This figure displays the results of several shape matching methods on isometric and non-isometric shapes. The top row shows results using the SCAPE dataset, which contains isometric (rigid) transformations. The bottom row shows results using the TOPKIDS dataset, which contains non-isometric (non-rigid) transformations. Each column represents a different shape matching algorithm: GEM, GRAMPA, DIR, ZoomOut, HOPE, and SHOT. The plots on the right show the percentage of correct correspondences as a function of geodesic error, which measures how accurately the algorithm maps corresponding points on the two shapes. The figure demonstrates that HOPE achieves a better balance of accuracy and smoothness compared to the other baselines, especially for non-isometric shapes.

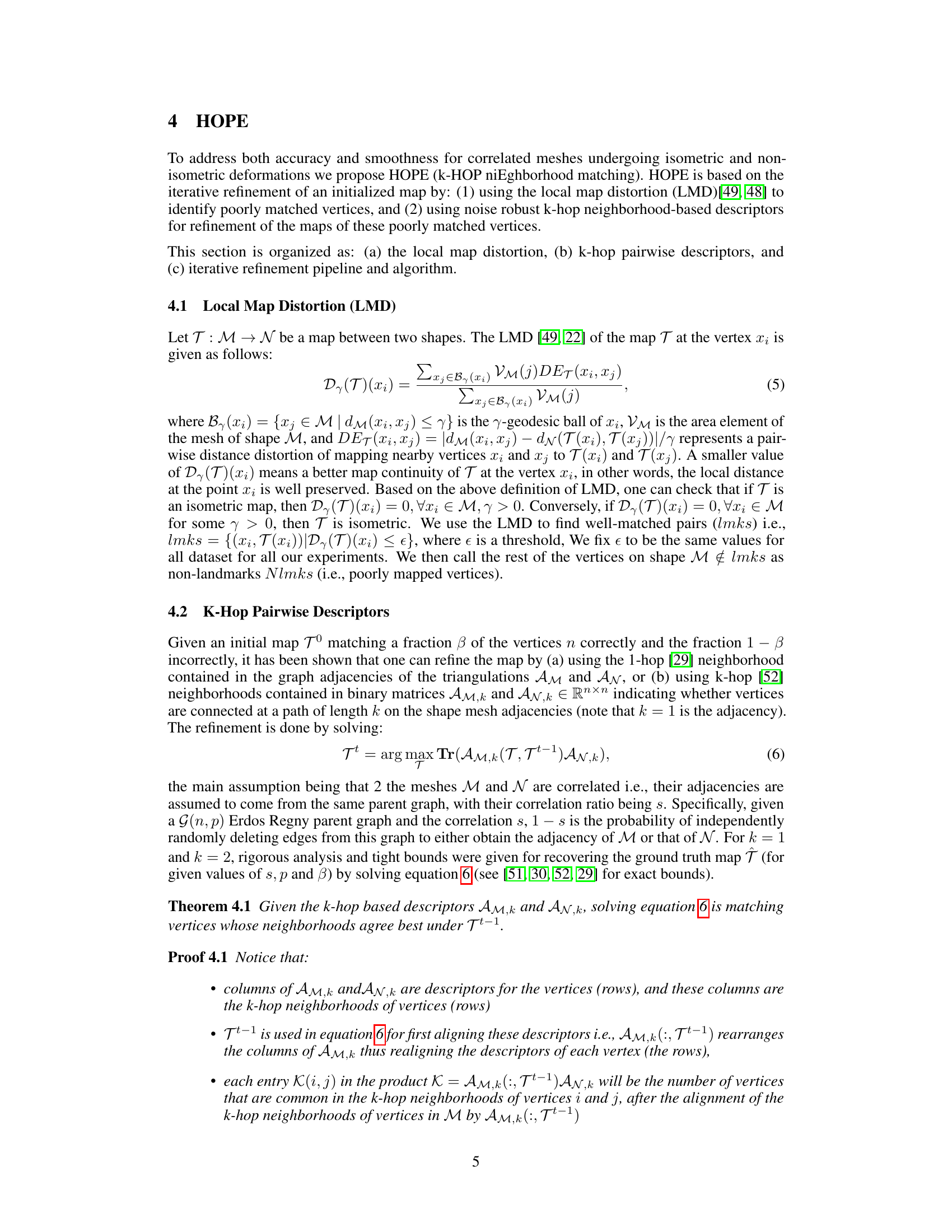

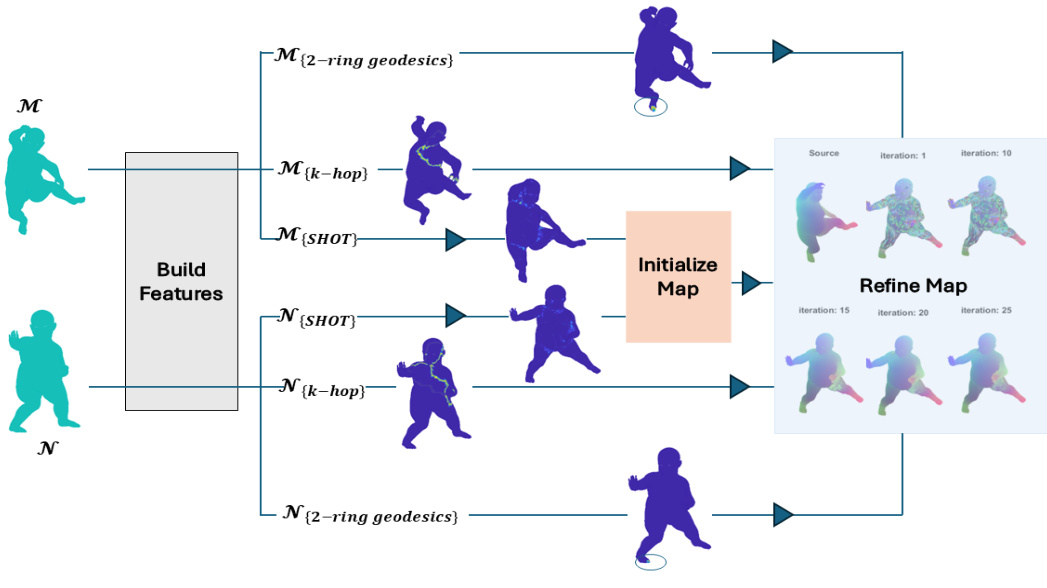

This figure illustrates the pipeline of the HOPE algorithm for shape matching. It begins with two input shapes, M and N. Features are extracted from both shapes using three different methods: 2-ring geodesics, k-hop neighborhoods, and SHOT descriptors. An initial map is created, possibly using SHOT descriptors alone. The core of the algorithm then iteratively refines this map using local map distortion to identify poorly matched vertices and k-hop neighborhood-based descriptors to improve the matches for those vertices. The refined map is iteratively updated across several iterations, showing a progressive improvement in the alignment of the two shapes.

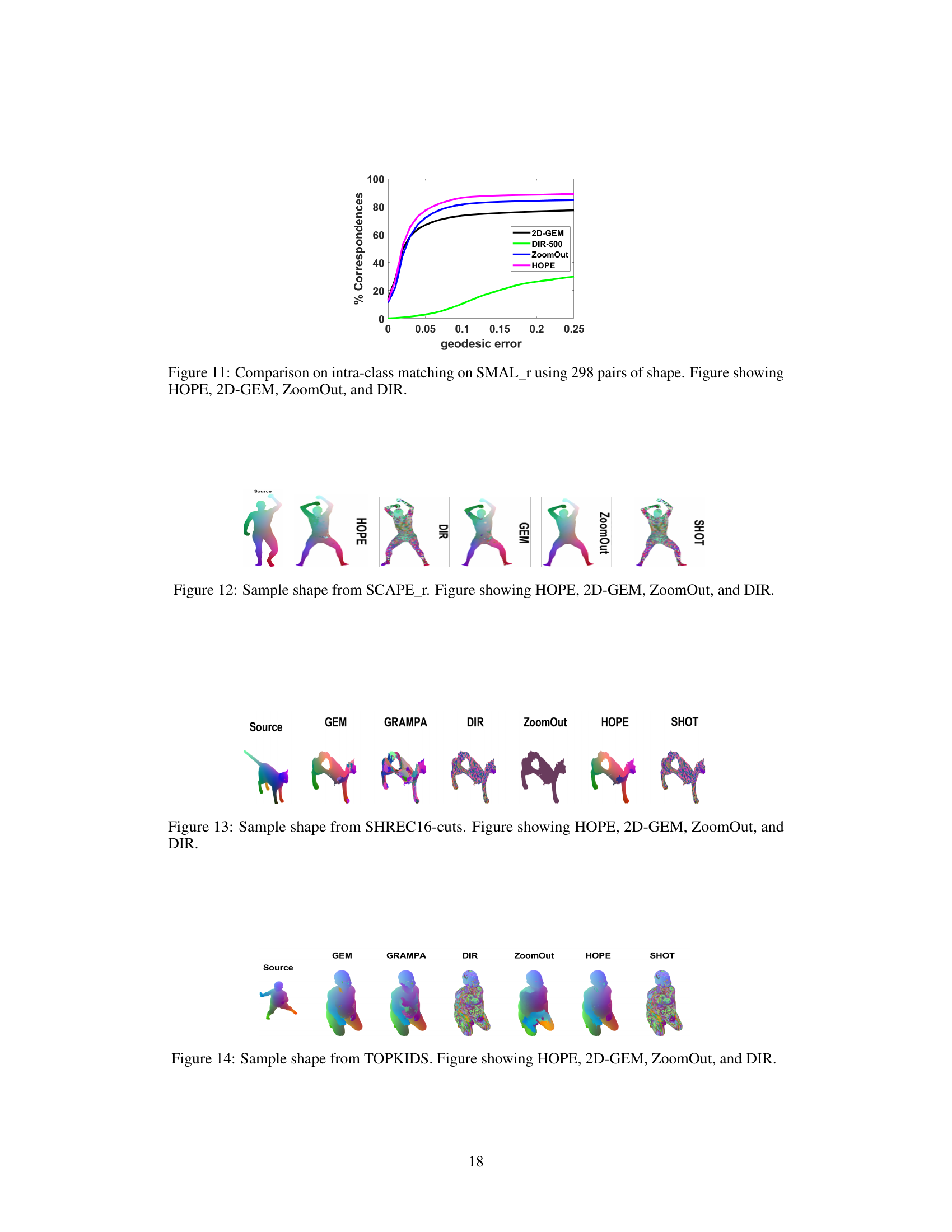

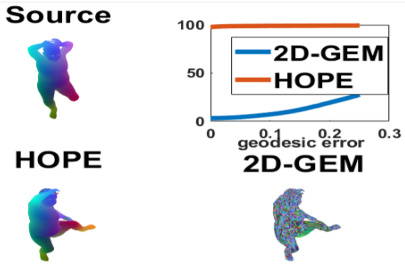

This figure shows a comparison of the performance of HOPE against other baselines (2D-GEM, ZoomOut, and DIR) on the SMAL_r dataset for intra-class matching. The figure includes a plot showing the percentage of correspondences against the geodesic error for each method. It also visually shows the shape matching results for a sample shape using each method, highlighting the differences in accuracy and smoothness between the methods.

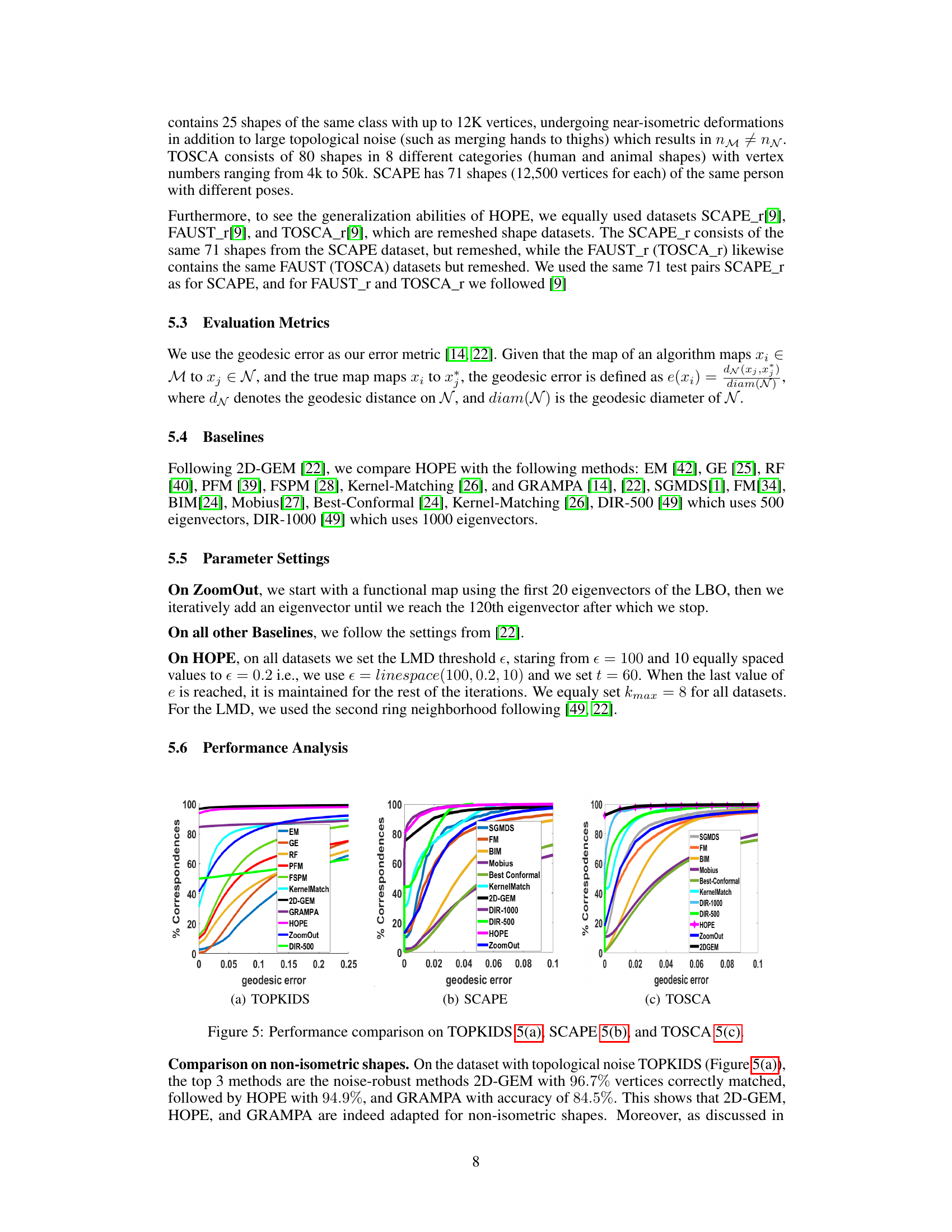

This figure compares the performance of HOPE against several baselines on three different datasets: TOPKIDS, SCAPE, and TOSCA. The x-axis represents the geodesic error, which measures the accuracy of the shape matching. The y-axis represents the percentage of correspondences that were correctly matched. The figure shows that HOPE generally outperforms or performs comparably to other state-of-the-art methods, particularly on the non-isometric dataset TOPKIDS.

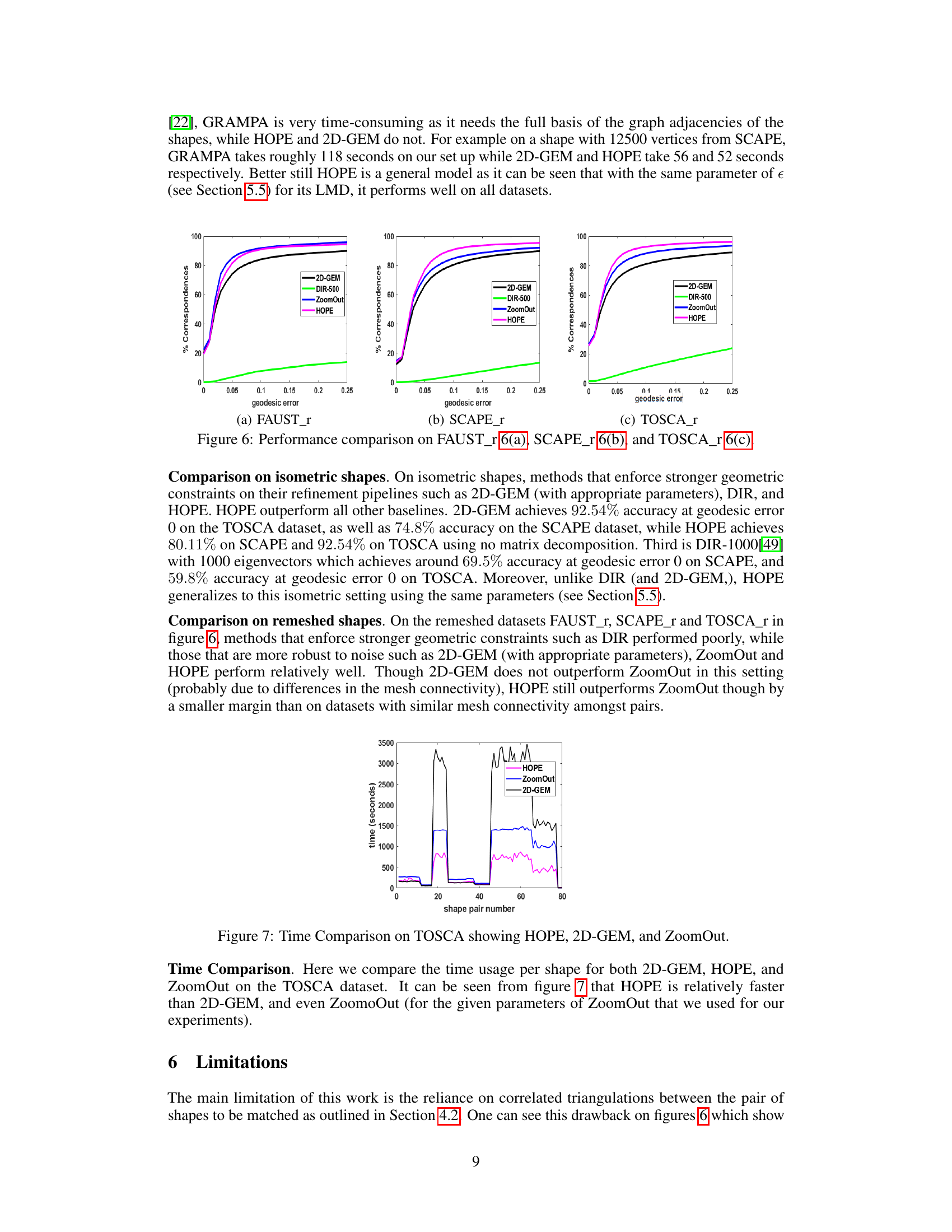

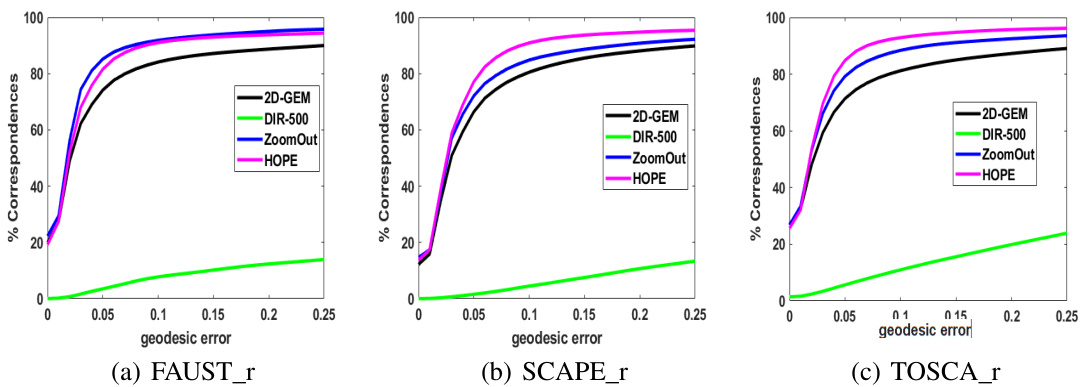

This figure compares the performance of HOPE against other methods (2D-GEM, DIR-500, ZoomOut) on three remeshed datasets: FAUST_r, SCAPE_r, and TOSCA_r. The plots show the percentage of correspondences achieved at different geodesic error levels. The results demonstrate HOPE’s robustness and generalizability across different shapes and mesh structures.

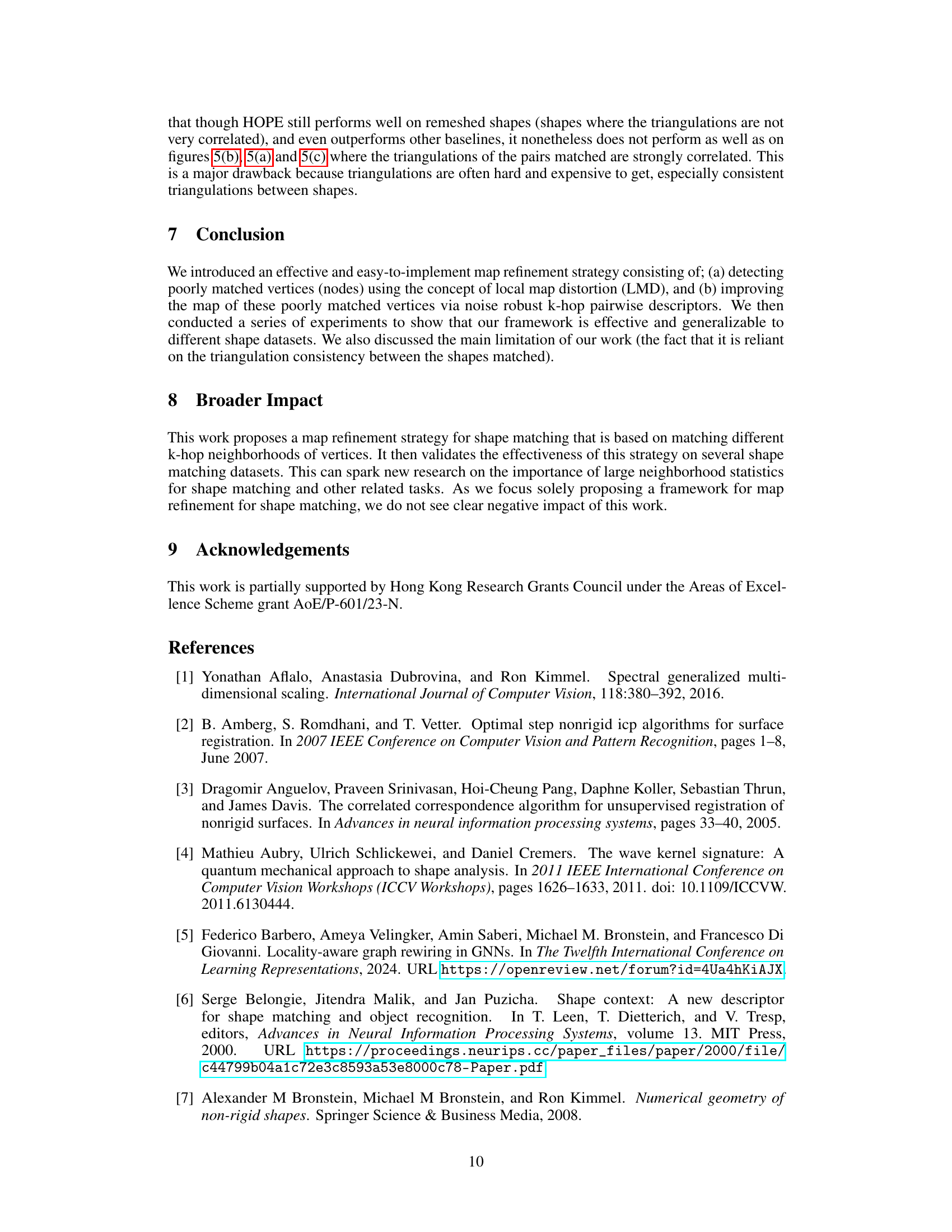

This figure compares the time usage per shape pair for HOPE, 2D-GEM, and ZoomOut on the TOSCA dataset. It demonstrates that HOPE is relatively faster than 2D-GEM and ZoomOut, especially for larger shape pairs, indicating its efficiency in shape matching.

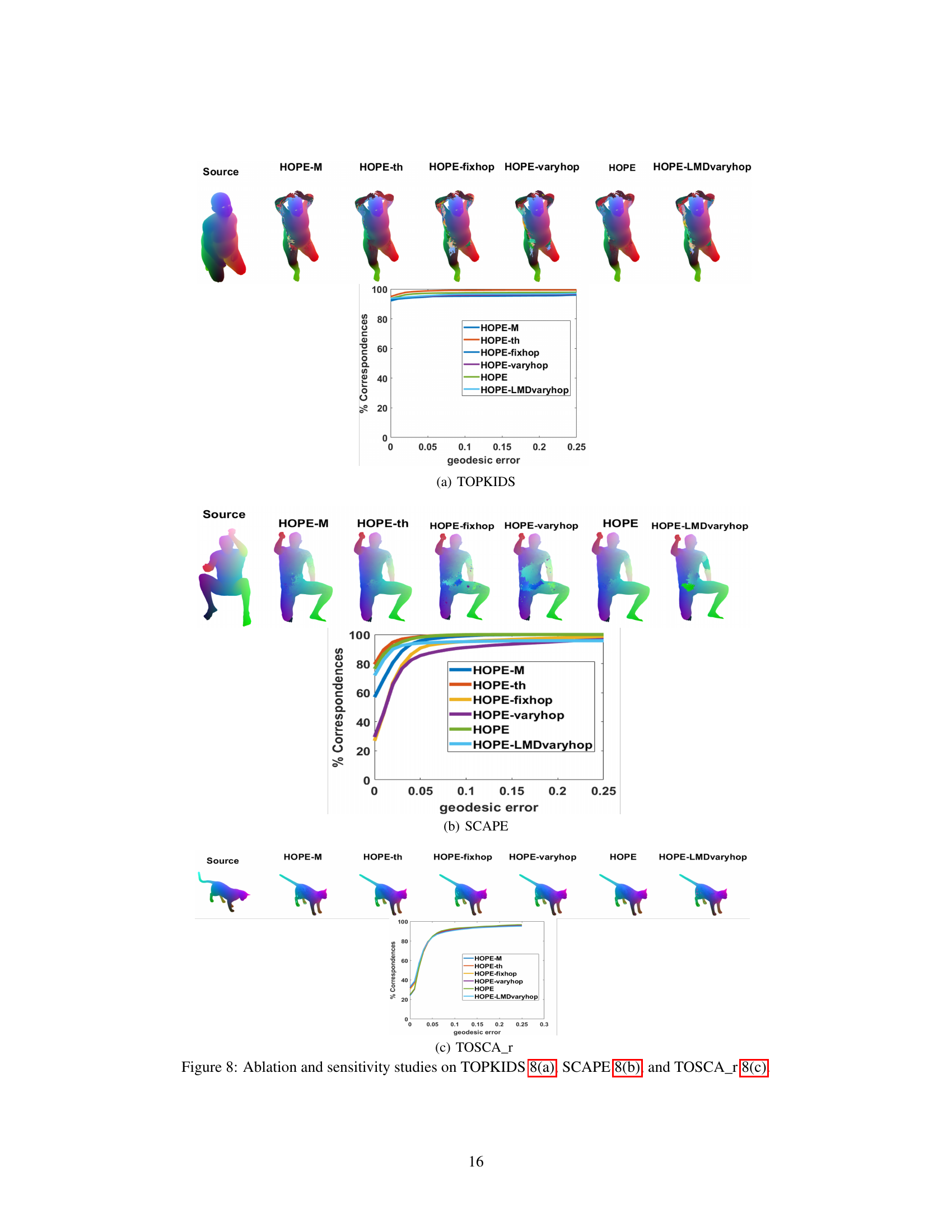

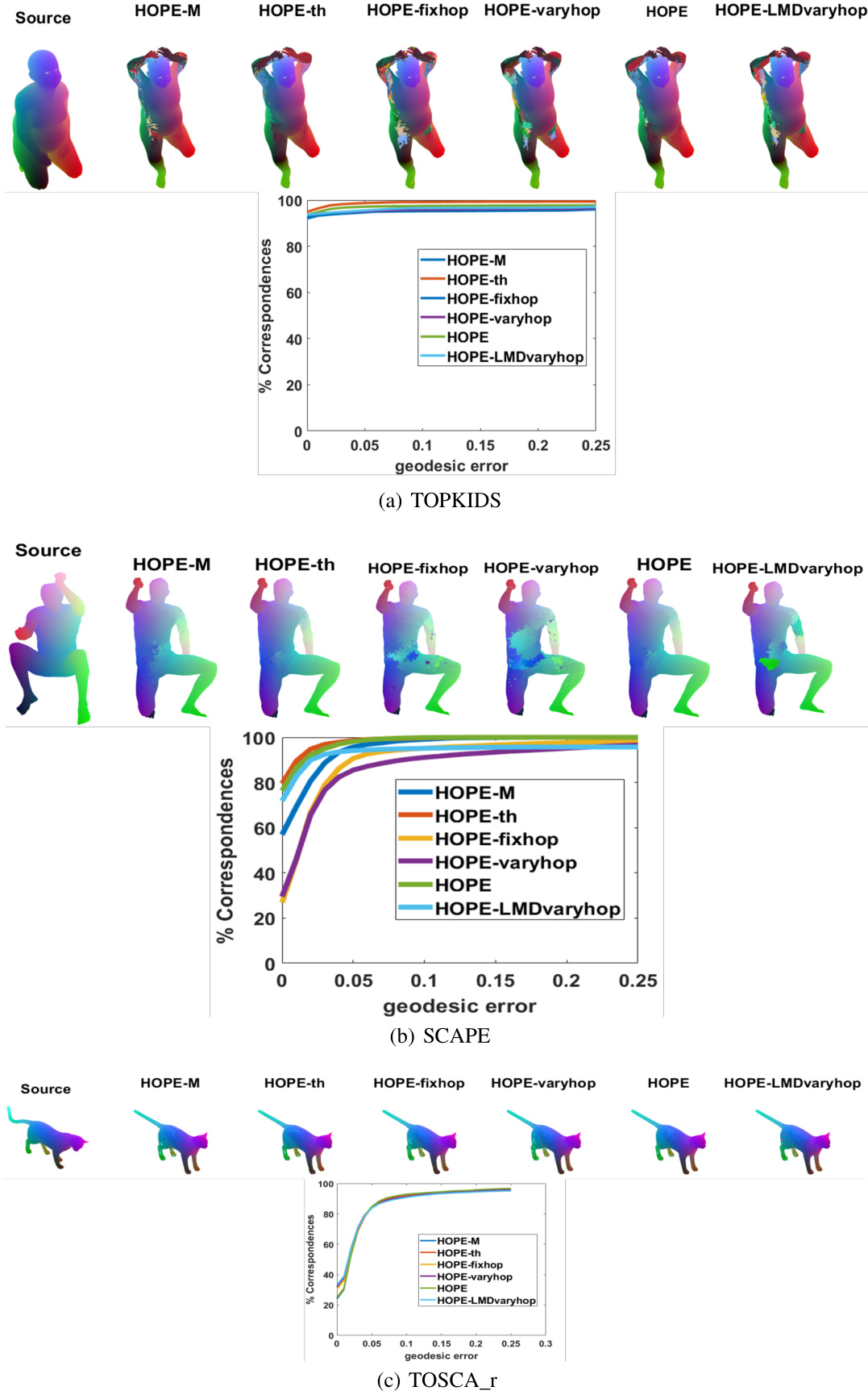

This figure presents the results of ablation and sensitivity studies conducted on three datasets: TOPKIDS, SCAPE, and TOSCA_r. Different versions of the HOPE algorithm were tested, each varying a parameter (like the number of iterations or the k-hop neighborhood strategy) or removing a component (like the local map distortion). The graphs display the percentage of correspondences achieved against the geodesic error for each variant. This allows for comparison and analysis to determine the impact of individual components and parameters on the algorithm’s accuracy.

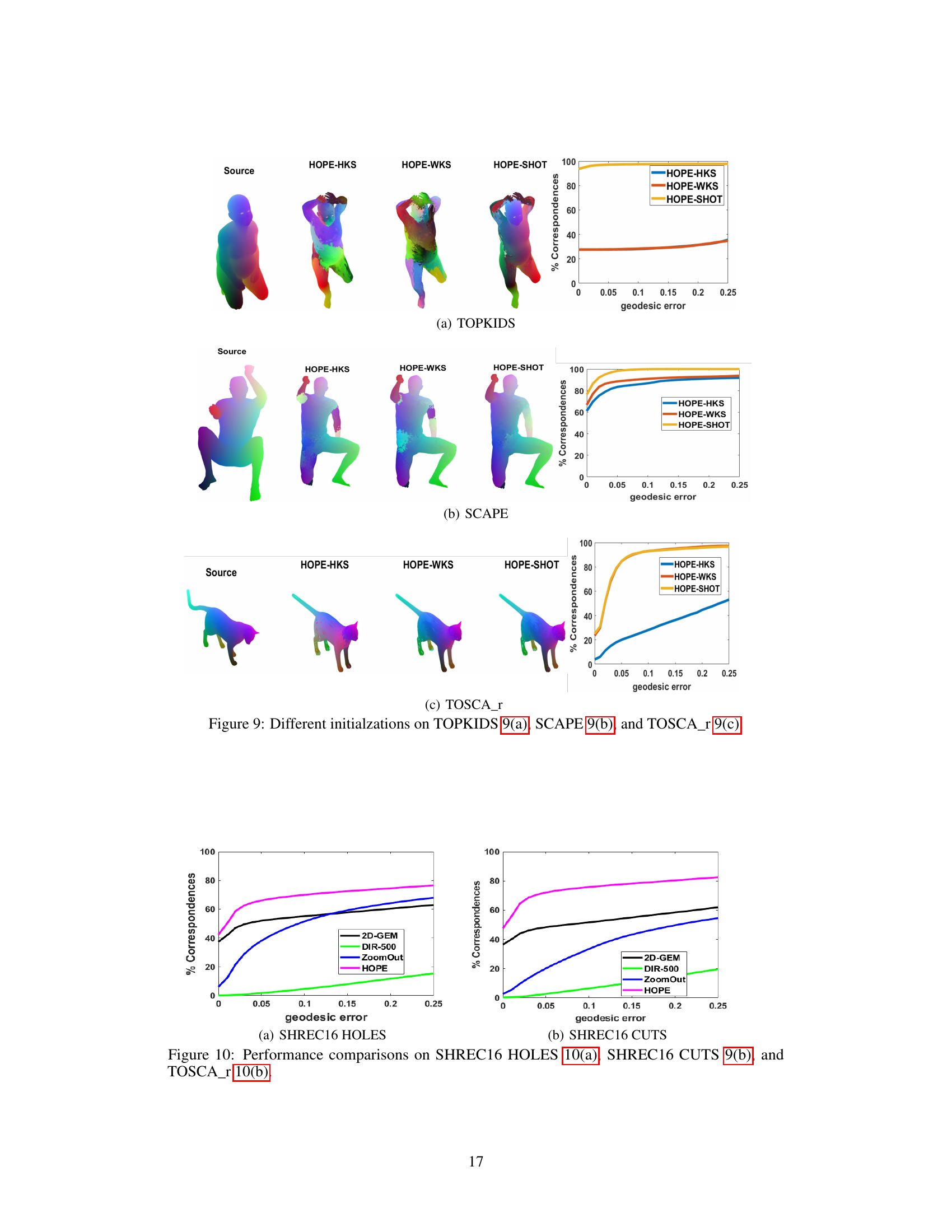

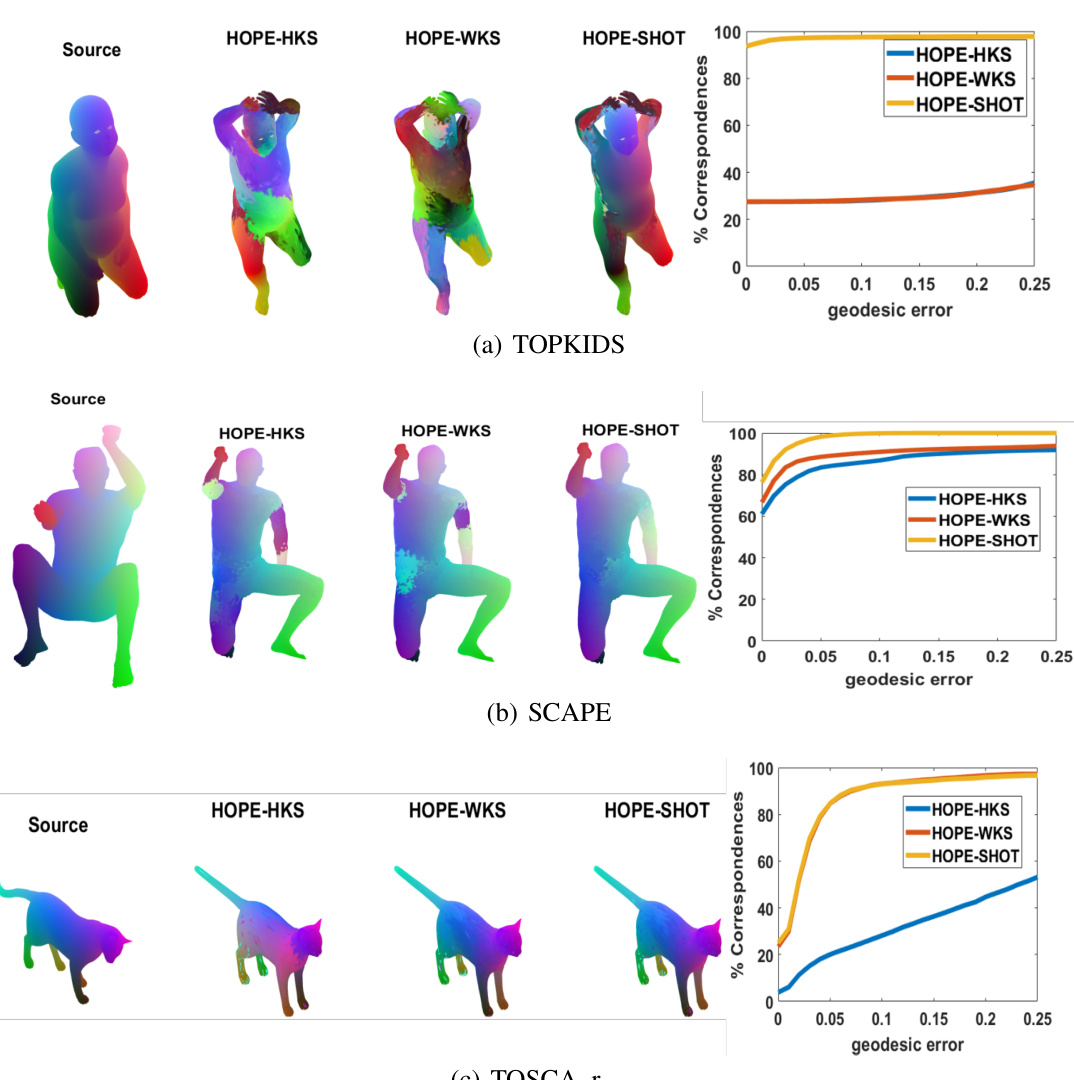

This figure demonstrates the performance of HOPE using different initialization methods: SHOT, HKS, and WKS. For each dataset (TOPKIDS, SCAPE, and TOSCA_r), the ‘Source’ column shows the original shape. The remaining columns show the results after applying HOPE with each initialization method, visualizing the resulting map quality. The corresponding graphs on the right show the percentage of correspondences plotted against the geodesic error for each initialization method. This comparison helps to assess the impact of initialization on the final matching accuracy and smoothness.

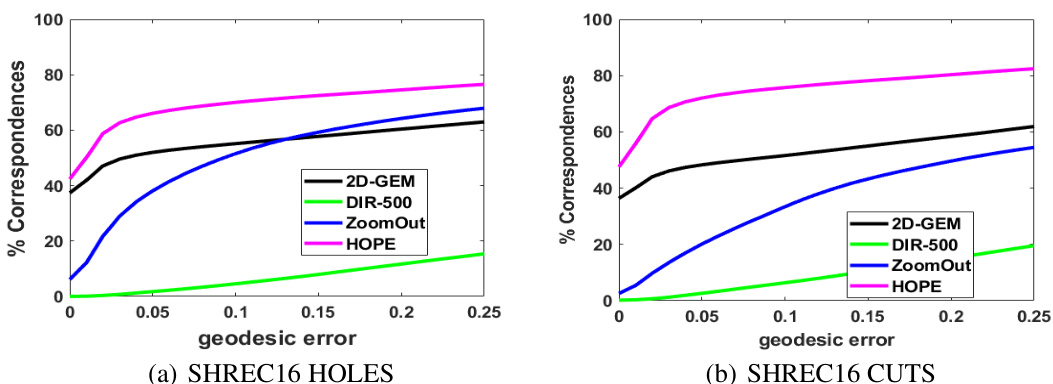

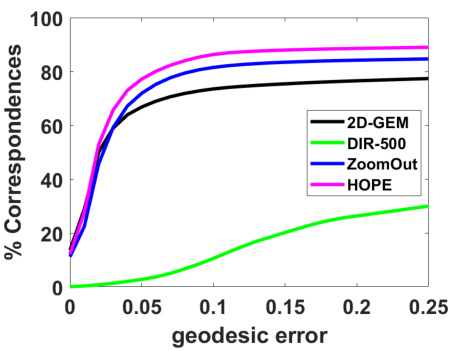

This figure compares the performance of HOPE against several baselines on two partial shape matching datasets (SHREC16 HOLES and SHREC16 CUTS) and one nearly isometric dataset (TOSCA). The x-axis represents the geodesic error, a measure of how well vertices are mapped between shapes. The y-axis shows the percentage of correctly matched vertices. The figure demonstrates HOPE’s performance in the context of partial shape matching and its relative accuracy compared to established methods like 2D-GEM, DIR-500, and ZoomOut.

This figure compares the performance of HOPE against other state-of-the-art shape matching methods on three different datasets: TOPKIDS (non-isometric), SCAPE (isometric), and TOSCA (isometric). The x-axis represents the geodesic error, a measure of the accuracy of the shape matching, while the y-axis shows the percentage of correspondences correctly matched. The figure demonstrates that HOPE achieves competitive performance across all datasets, particularly excelling in the non-isometric TOPKIDS dataset.

This figure compares the performance of several shape matching baselines (GEM, GRAMPA, DIR, ZoomOut, HOPE, SHOT) on isometric (SCAPE dataset) and non-isometric (TOPKIDS dataset) shapes. The results are visualized as color-coded mappings between source and target shapes, illustrating the accuracy and smoothness of the correspondence. The figure demonstrates how HOPE achieves improved accuracy and smoothness compared to the baselines on both isometric and non-isometric shapes.

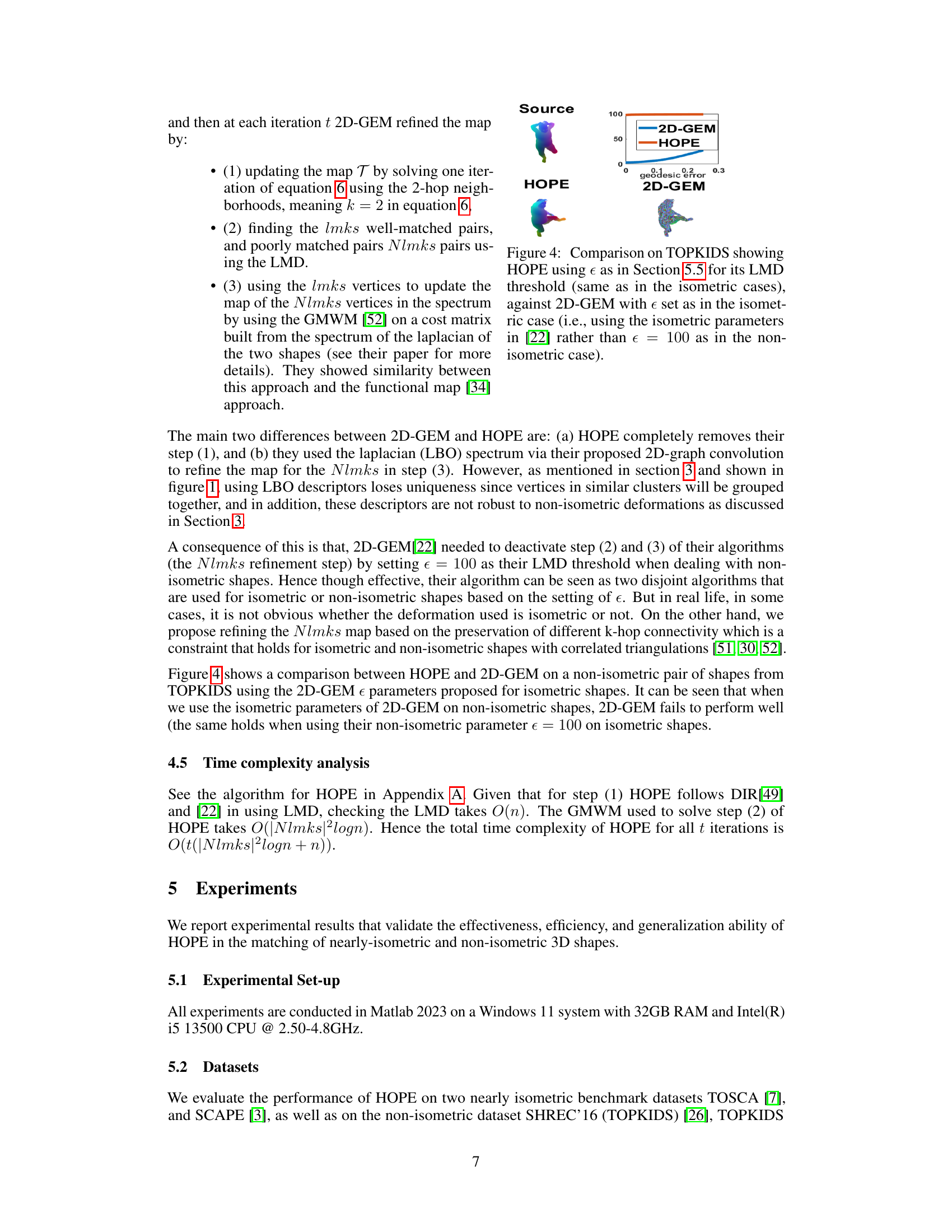

This figure shows a visual comparison of shape matching results on a sample shape from the TOPKIDS dataset. Several methods are compared: HOPE (the proposed method), 2D-GEM, ZoomOut, and DIR. Each method’s output is displayed alongside the original shape. The color mapping represents the correspondence between the vertices of the source and target shapes. The visual comparison allows for qualitative assessment of the accuracy and smoothness of the different methods’ shape matching.

This figure compares the performance of several shape matching baselines (GEM, GRAMPA, DIR, ZoomOut, HOPE, SHOT) on isometric (SCAPE dataset) and non-isometric (TOPKIDS dataset) shape pairs. The color mapping on each shape visually represents the correspondence between vertices of the source and target shapes generated by each method. The plots to the right quantify performance using the percentage of correct correspondences and the geodesic error.

Full paper#