↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

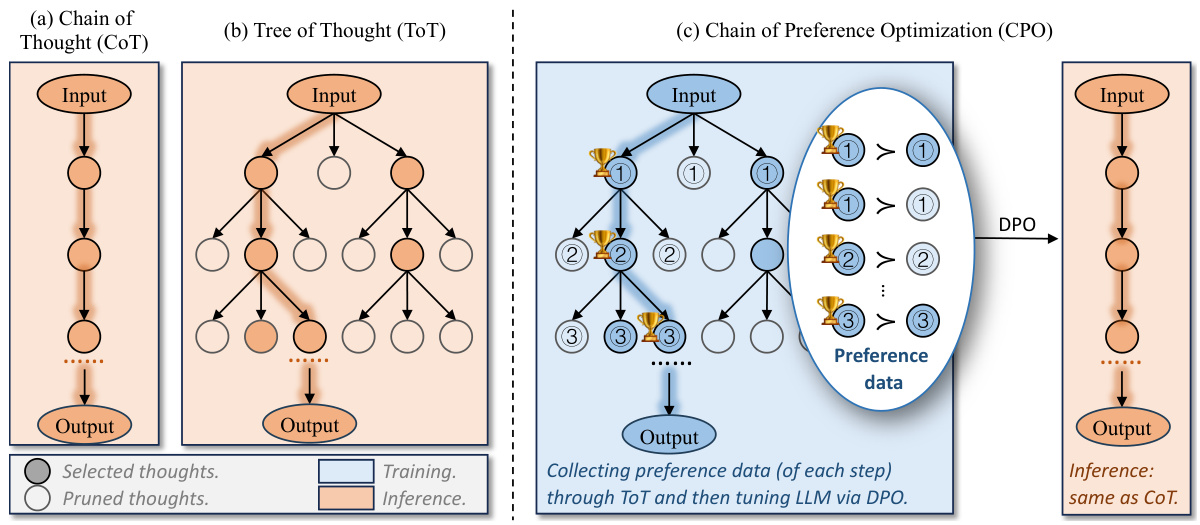

Large Language Models (LLMs) often struggle with complex reasoning tasks. While Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting encourages explicit reasoning, it can overlook optimal paths. Tree-of-Thought (ToT) explores the reasoning space more thoroughly but is computationally expensive. This creates a need for methods that balance reasoning quality and efficiency.

The paper introduces Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO), a novel method that addresses this issue. CPO fine-tunes LLMs using preference data derived from ToT’s search tree, aligning each step of CoT reasoning with ToT’s preferred paths. Experiments show that CPO significantly improves LLM performance across various complex tasks (question answering, fact verification, arithmetic reasoning) while maintaining efficiency, surpassing both CoT and other ToT-based methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on LLMs and reasoning because it presents a novel method (CPO) to significantly improve the reasoning capabilities of LLMs without the substantial increase in inference time that other methods like ToT incur. It leverages inherent preference information from the ToT search process for more efficient training, opening new avenues for research in LLM optimization and reasoning.

Visual Insights#

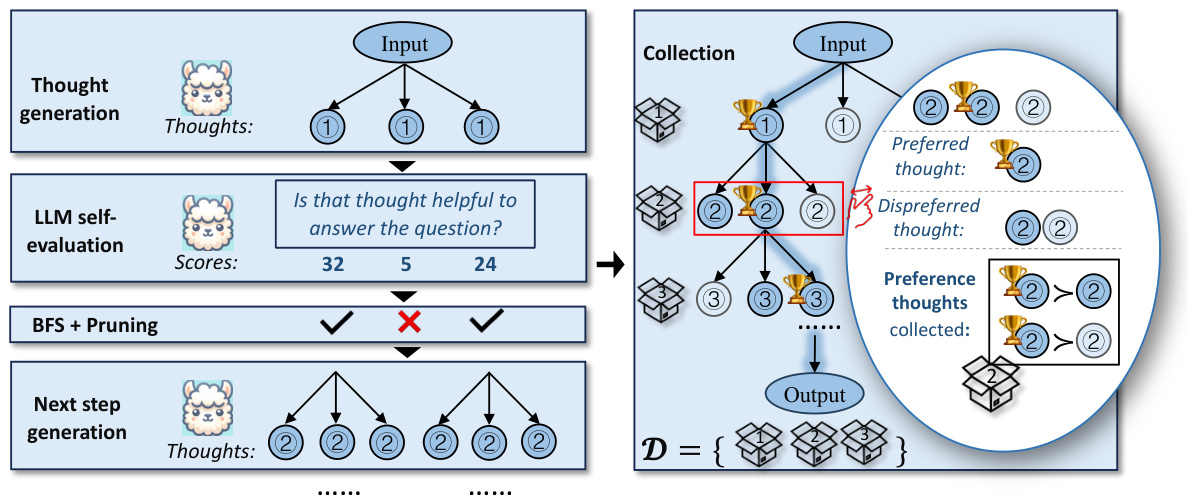

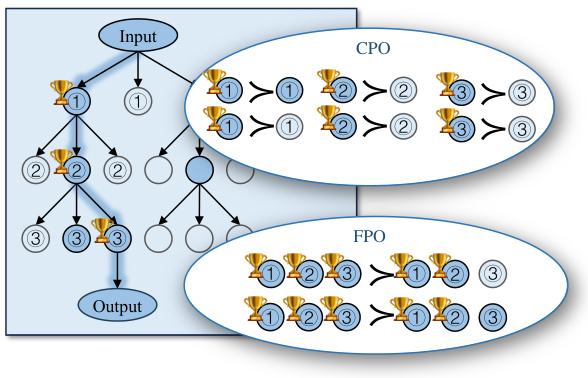

This figure compares three different methods for prompting LLMs to perform chain-of-thought reasoning: CoT, ToT, and CPO. CoT follows a single path, ToT explores multiple paths, and CPO uses ToT’s search tree to generate preference data that is subsequently used to fine-tune the LLM. The figure highlights the differences in their reasoning processes and demonstrates how CPO leverages the strengths of ToT while avoiding its computational cost.

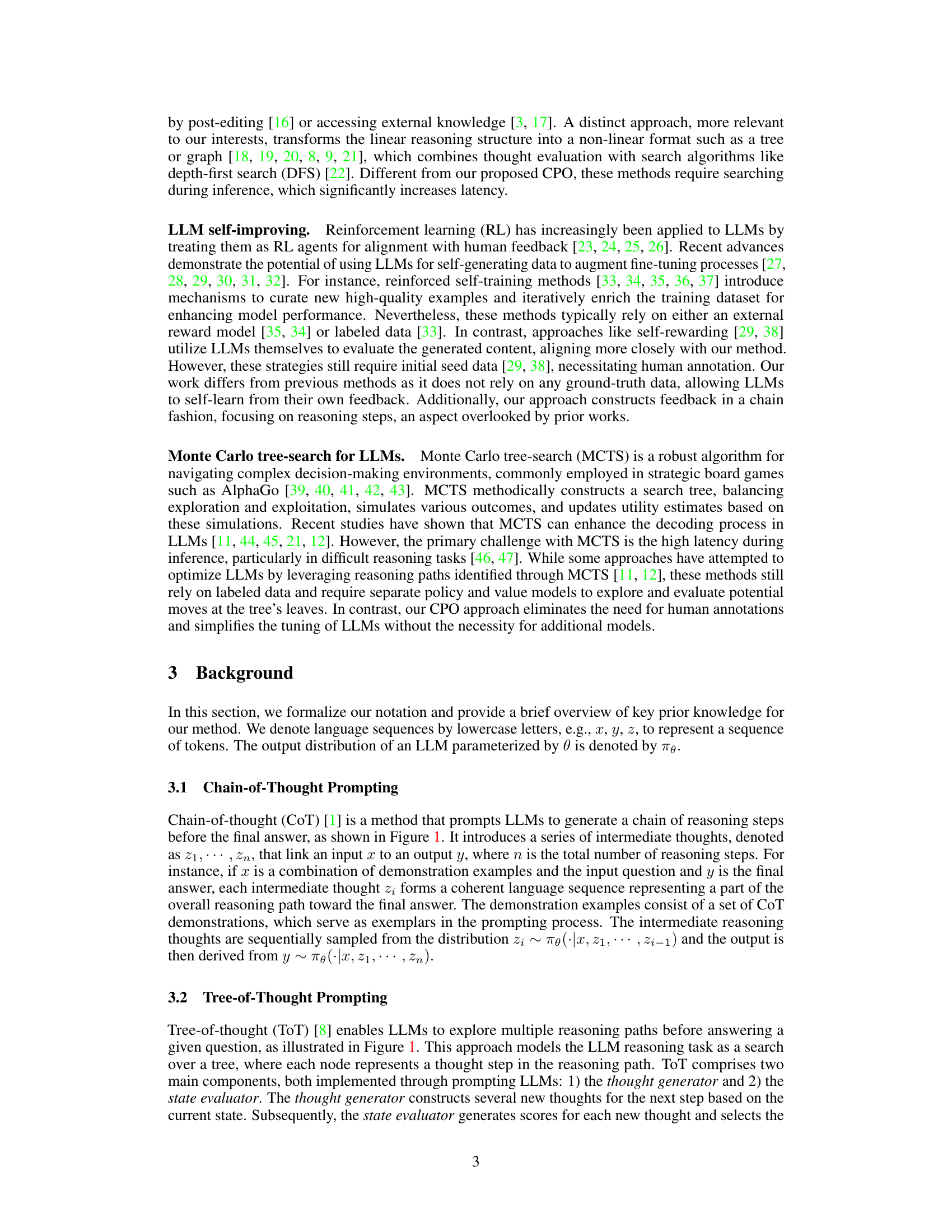

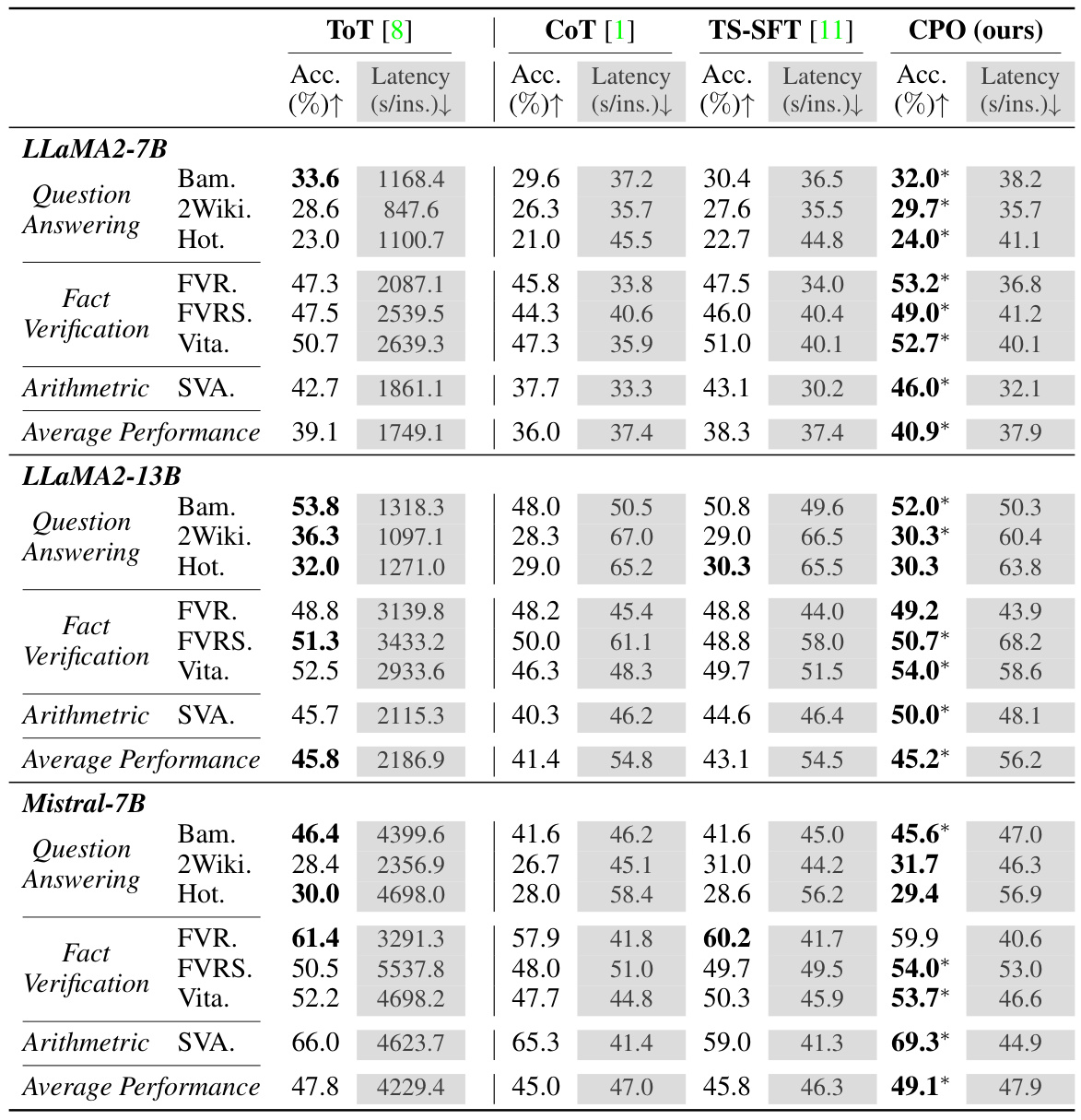

This table presents a comparison of the performance of four different methods (ToT, CoT, TS-SFT, and CPO) on three types of reasoning tasks: Question Answering, Fact Verification, and Arithmetic Reasoning. The results are shown for three different large language models (LLaMA2-7B, LLaMA2-13B, and Mistral-7B). For each method and model, the accuracy and latency (in seconds per instance) are reported. A significant improvement (p<0.01) by CPO over the best baseline is indicated by an asterisk (*). The best result for each task is shown in bold.

In-depth insights#

CoT Reasoning Boost#

A hypothetical ‘CoT Reasoning Boost’ section in a research paper would likely explore methods to enhance the chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning capabilities of large language models (LLMs). This could involve techniques to improve the coherence and accuracy of the generated reasoning steps. One approach might focus on improving the LLM’s ability to select relevant information and avoid irrelevant or misleading details during the reasoning process. Another key area would be developing strategies to mitigate the problem of LLMs getting stuck in suboptimal reasoning paths, perhaps by incorporating exploration mechanisms or incorporating external knowledge sources. Furthermore, the section might investigate fine-tuning strategies to optimize LLMs for CoT reasoning, potentially using reinforcement learning or other advanced training techniques. Ultimately, the goal would be to present empirical evidence demonstrating a significant improvement in the quality and efficiency of LLM reasoning compared to standard CoT methods. The section would also likely discuss limitations, such as potential biases in the training data or the computational cost of more sophisticated reasoning techniques.

CPO: Preference Data#

The effectiveness of Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO) hinges on the quality of its preference data. CPO leverages the inherent preference information within a Tree of Thought (ToT) search, rather than relying solely on the optimal path. This is a crucial distinction, as ToT generates multiple reasoning paths, and CPO uses both the successful and unsuccessful paths to create preference data pairs. Each pair highlights a preferred thought (from the successful path) and a dispreferred thought (from an unsuccessful path at the same step). This approach enriches the training data by capturing nuances beyond just the optimal reasoning sequence. The use of paired preference data, instead of complete path data, allows for more fine-grained supervision during LLM fine-tuning. This leads to an LLM that better aligns with the reasoning strategies implicit in ToT, achieving comparable or improved performance without the computational cost of running ToT during inference. The use of direct preference optimization (DPO) further enhances the effectiveness of the preference data, as it directly optimizes the LLM to reflect the inherent preferences within the data.

ToT’s Search Refined#

The heading “ToT’s Search Refined” suggests a focus on improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the Tree-of-Thought (ToT) search algorithm. ToT, unlike the simpler Chain-of-Thought (CoT), explores multiple reasoning paths simultaneously, creating a tree structure. While this approach can lead to better solutions by avoiding suboptimal paths, it significantly increases computational costs. Therefore, “refining” ToT’s search likely involves strategies to reduce the search space, prioritize promising branches, or utilize more efficient search algorithms. This could include incorporating heuristics to guide the search, using more sophisticated pruning techniques to eliminate unfruitful branches early, or leveraging reinforcement learning to train the model to select optimal paths faster. The goal is likely to maintain ToT’s ability to find superior reasoning paths while mitigating its computational drawbacks, enabling wider applicability in complex problem-solving scenarios. A refined ToT might also integrate techniques from Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), which balances exploration and exploitation, leading to more focused and efficient search. The refinement could also focus on the quality of the generated thoughts, ensuring they are more relevant and coherent, possibly through improved prompting techniques or more advanced language model architectures. Ultimately, “ToT’s Search Refined” suggests a critical enhancement to a promising reasoning method, making it more practical and scalable.

CPO: Efficiency Gains#

The heading ‘CPO: Efficiency Gains’ suggests an analysis of the computational efficiency improvements achieved by Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO). A deep dive would explore how CPO’s mechanism of leveraging inherent preference information from Tree of Thought (ToT) avoids the substantial inference burden of ToT while achieving comparable or superior results. Key aspects to investigate include the reduction in inference time and computational resources required, comparing CPO’s performance to both traditional Chain-of-Thought (CoT) and ToT methods. The analysis should quantify these gains (e.g., X times faster, Y% reduction in resource usage) across various problem types and LLM sizes. It’s crucial to discuss whether the efficiency improvements outweigh any potential increases in training time or complexity associated with CPO, especially considering the creation of paired preference data from ToT. Finally, a discussion on the scalability and generalizability of CPO’s efficiency gains to larger LLMs and more complex problems would provide valuable insights. Overall, a comprehensive discussion of ‘CPO: Efficiency Gains’ will highlight the practical advantages of CPO for real-world applications of LLMs where both accuracy and efficiency are paramount.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO) method could involve several promising avenues. Extending CPO’s applicability to diverse model architectures beyond LLMs, such as incorporating it into vision-language models or other multimodal architectures, is a key area. Another crucial direction is exploring more sophisticated search strategies within the ToT framework to further enhance efficiency and potentially reduce reliance on computationally expensive methods. Investigating the impact of different preference data generation techniques on the effectiveness of CPO is also crucial. Developing more robust methods for handling noisy or incomplete preference data, perhaps via techniques inspired by RLHF, would significantly improve robustness. Finally, addressing potential ethical concerns surrounding the use of CPO, particularly regarding bias amplification and malicious applications, warrants careful consideration and development of mitigation strategies.

More visual insights#

More on figures

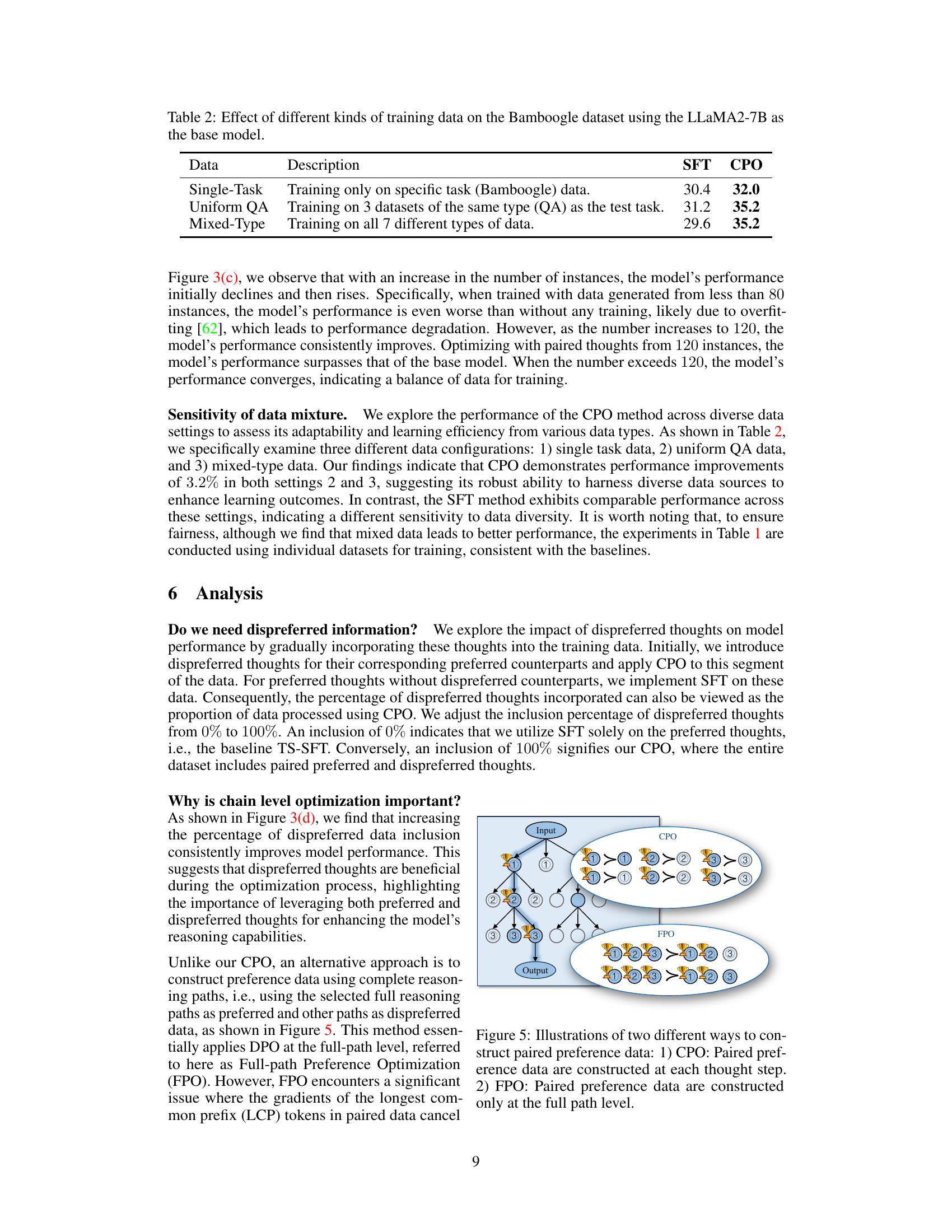

This figure illustrates the Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO) method. The left side shows the thought generation, evaluation, and pruning process. The LLM generates multiple thoughts at each step, evaluates them, and prunes less helpful thoughts using a Breadth-First Search (BFS) algorithm. The right side depicts the collection of preference data. Preferred thoughts (those in the final reasoning path) are paired with their dispreferred siblings to create training data for the CPO algorithm. This preference data guides the LLM to align its reasoning steps with those preferred by the ToT, improving reasoning quality without sacrificing inference efficiency.

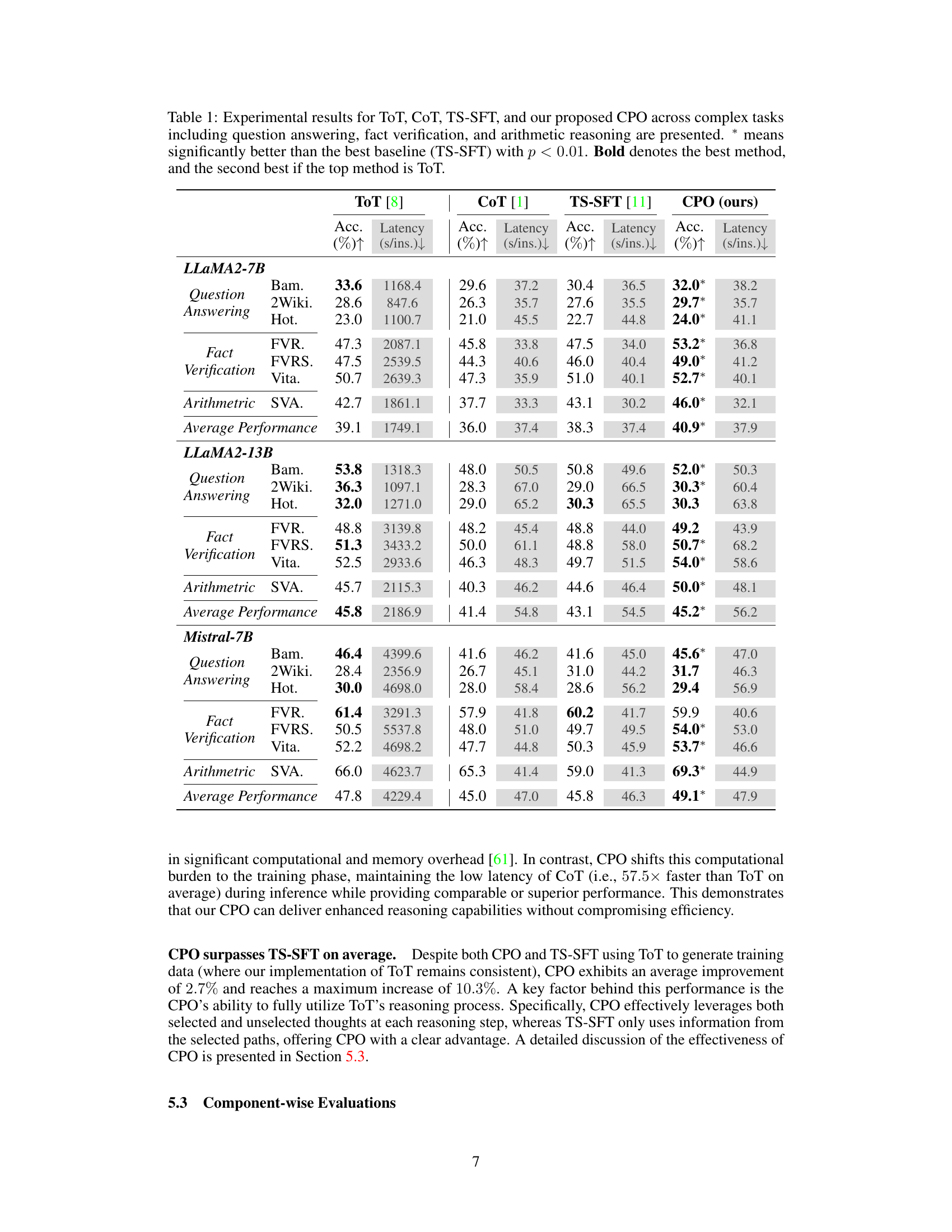

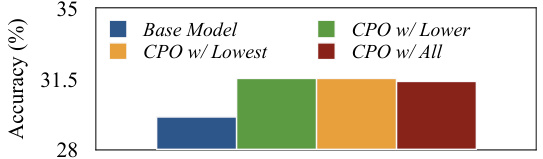

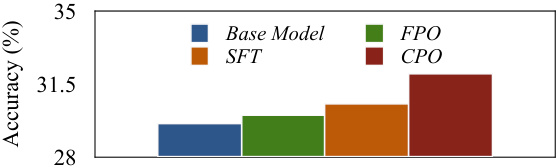

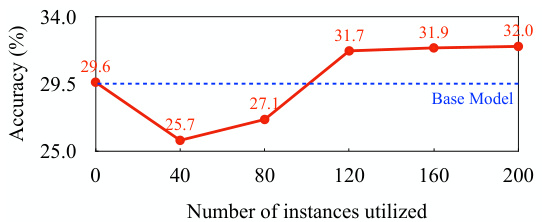

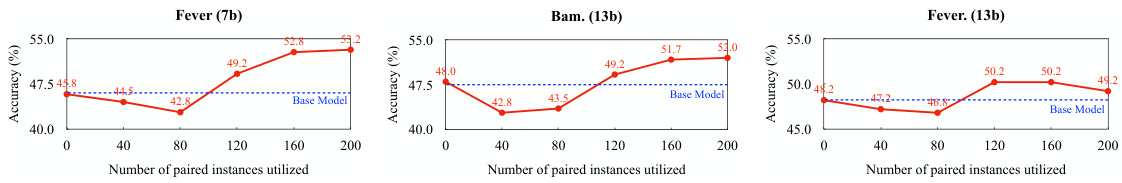

This figure presents a component-wise evaluation of the Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO) method on the Bamboogle dataset using the LLaMA2-7B model. It analyzes the impact of different methods for selecting dispreferred thoughts, the effect of per-step preference supervision, the effect of the number of instances in generating paired thoughts, and the effect of dispreferred thoughts in optimization. The subfigures show that selecting all thoughts not in the selected path as dispreferred yields the best performance, that per-step preference supervision is more effective than full-path supervision, that an optimal amount of training data leads to peak performance, and that including dispreferred thoughts in training is beneficial for improving model accuracy.

This figure presents a component-wise evaluation and analysis performed on the Bamboogle dataset using the LLaMA2-7B model. It visualizes the results of experiments that explore different aspects of the Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO) method, including the impact of varying the number of instances used for training, different methods for selecting dispreferred thoughts, and the effect of incorporating only preferred thoughts in the optimization process. The results are displayed in four subfigures that collectively illustrate the effects of several key parameters and choices on model accuracy and efficiency. This helps to understand the relative contributions of various design choices of the CPO method.

This figure presents a component-wise evaluation and analysis of the Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO) method on the Bamboogle dataset using the LLaMA2-7B model. It shows the impact of different choices made in the CPO algorithm, allowing for a granular understanding of how each part contributes to the overall improved performance. Specifically, it displays accuracy results with respect to different methods for selecting dispreferred thoughts (lowest scoring, lower scoring, all thoughts outside the best path), effects of per-step preference supervision compared to other approaches (SFT and FPO), effect of the number of instances used to generate paired preference thoughts, and effect of the percentage of dispreferred thoughts included in optimization. Each subfigure breaks down one aspect of the CPO process.

This figure presents a comprehensive analysis of different components within the Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO) method. Subfigures (a) and (b) show the impact of using different strategies for selecting dispreferred thoughts and the effect of per-step preference supervision in comparison to the base model and other methods. Subfigure (c) explores the relationship between the number of training instances used and the accuracy of the model. Finally, subfigure (d) illustrates the impact of varying the proportion of dispreferred thoughts used in optimization on the final model accuracy. Overall, this figure provides detailed insights into the key factors affecting the performance of CPO.

This figure presents a component-wise evaluation and analysis conducted on the Bamboogle dataset using the LLaMA2-7B language model. It showcases the impact of different methods for selecting dispreferred thoughts in the Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO) process, the effect of per-step preference supervision in comparison to other methods (SFT and FPO), the influence of the number of instances used to generate preference pairs, and lastly, how the proportion of dispreferred thoughts in optimization influences the performance. Each subplot visualizes a specific aspect of the experiments, providing a detailed breakdown of the CPO method’s efficacy.

This figure compares three different reasoning methods: Chain-of-Thought (CoT), Tree-of-Thought (ToT), and Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO). CoT follows a single path, ToT explores multiple paths, and CPO leverages ToT’s search tree to fine-tune LLMs, aligning their reasoning steps with ToT’s preferred paths to improve efficiency and accuracy. The diagram visually represents the reasoning process as a tree structure, highlighting the differences in path selection and thought generation among the three methods.

This figure presents a component-wise evaluation and analysis of the Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO) method on the Bamboogle dataset using the LLaMA2-7B model. It breaks down the impact of different aspects of the CPO method on accuracy. Subfigures (a) and (b) compare the performance of CPO against baselines, showing the effect of using only the lowest-scoring thoughts as dispreferred, lower-scoring thoughts, and all thoughts not in the optimal paths as dispreferred in (a), and contrasting CPO with other methods like full-path preference optimization (FPO) in (b). Subfigures (c) and (d) demonstrate the impact of the number of training instances and the percentage of dispreferred thoughts used in the optimization process, respectively. The overall findings reveal that CPO effectively leverages preference information from all thoughts generated during the tree-search process to improve the model’s reasoning ability, surpassing the baseline model and other optimization approaches.

This figure presents a component-wise evaluation and analysis performed on the Bamboogle dataset using the LLaMA2-7B model. It shows the impact of different methods for selecting dispreferred thoughts, the effect of per-step preference supervision, the effect of the number of instances used in generating paired thoughts, and the effect of utilizing dispreferred thoughts in optimization. Each subfigure provides a specific analysis on the model’s performance with varying approaches to data selection and inclusion of information from unsuccessful reasoning paths.

This figure presents a component-wise evaluation and analysis of the proposed Chain of Preference Optimization (CPO) method on the Bamboogle dataset using the LLaMA2-7B language model. It comprises four subfigures, each illustrating a different aspect of the CPO methodology. (a) Effect of dispreferred thoughts selection: Compares the performance of the base model and CPO variants with various strategies for selecting dispreferred thoughts (lowest, lower, all), revealing the minimal performance impact of different selection methods. (b) Effect of per-step preference supervision: Contrasts CPO’s performance with base model, SFT (Supervised Fine-Tuning), and FPO (Full-Path Preference Optimization), showcasing CPO’s superior performance due to the use of per-step preference data. (c) Effect of the number of instances in generating paired thoughts: Shows how the number of instances used in generating paired thoughts impacts CPO’s performance, initially decreasing due to overfitting before rising and converging to a stable level. (d) Effect of dispreferred thoughts in optimization: Demonstrates the impact of the proportion of dispreferred thoughts used in optimization, suggesting consistent improvement with increased inclusion. The overall figure highlights the effectiveness of CPO’s specific design choices.

More on tables

This table presents the experimental results comparing four different methods (ToT, CoT, TS-SFT, and CPO) across three complex reasoning tasks: Question Answering, Fact Verification, and Arithmetic Reasoning. The results are shown for three different LLMs (LLaMA2-7B, LLaMA2-13B, and Mistral-7B). For each task and LLM, the accuracy and latency (in seconds per instance) are provided. The ‘*’ indicates statistically significant improvements (p<0.01) compared to the best baseline (TS-SFT), while bold highlights the best-performing method in each case. If ToT is the best-performing method, the second-best method is shown in bold.

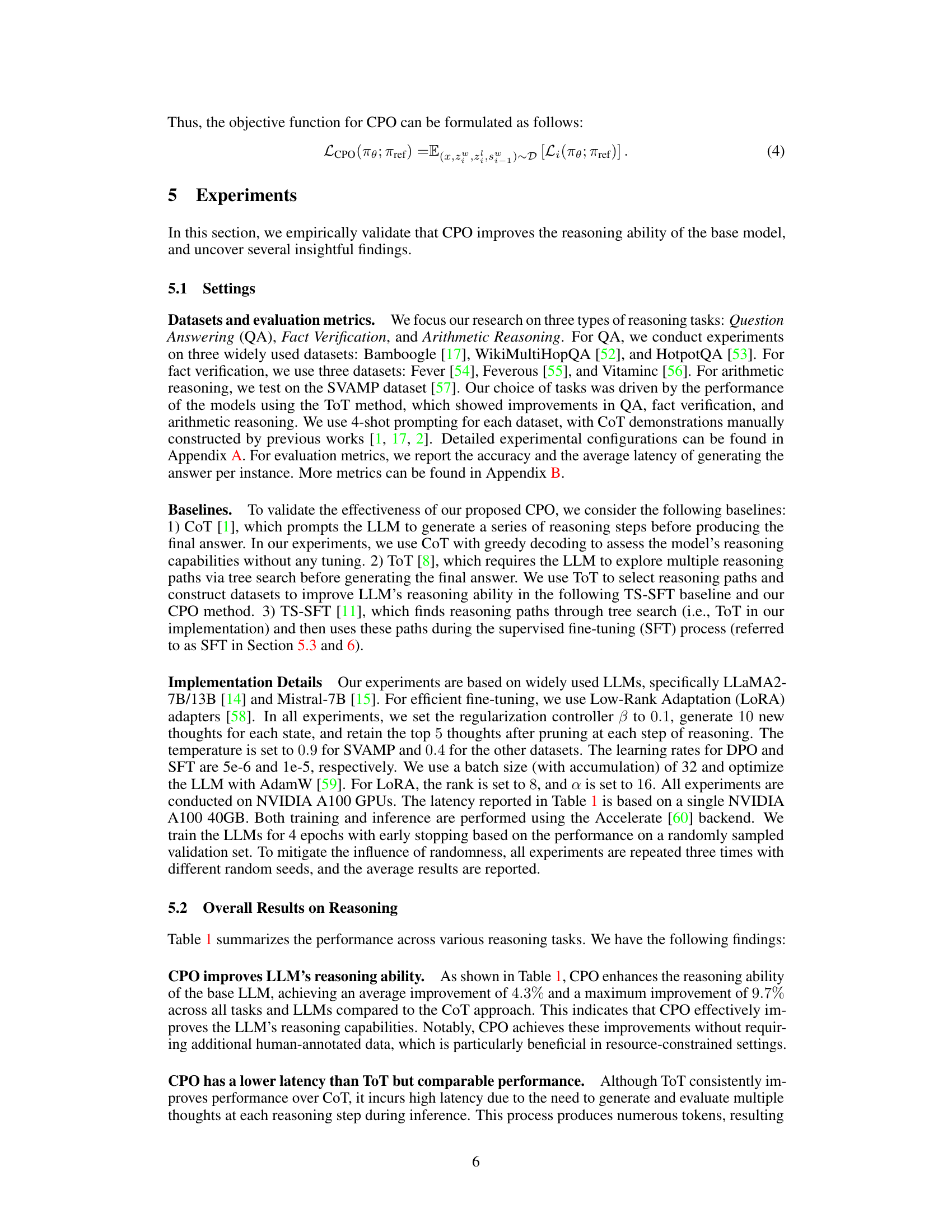

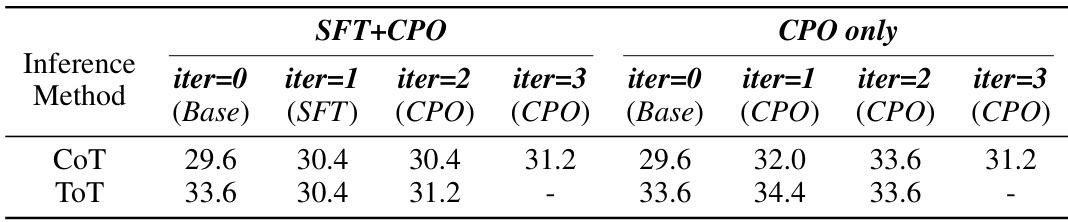

This table shows the results of experiments on the Bamboogle dataset using the LLaMA2-7B model, exploring the impact of iterative learning using two different strategies: SFT+CPO and CPO only. Each strategy involves multiple iterations, with the performance measured using both CoT and ToT inference methods. The table showcases how the model’s performance improves or changes across different iterations and inference methods.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of four different methods (ToT, CoT, TS-SFT, and CPO) across three types of reasoning tasks: Question Answering, Fact Verification, and Arithmetic Reasoning. The results are shown for three different large language models (LLaMA2-7B, LLaMA2-13B, and Mistral-7B). For each method and model, the accuracy and latency (in seconds per instance) are reported. A * indicates that a method’s accuracy is statistically significantly better than the best baseline (TS-SFT) at a significance level of p < 0.01. Bold values indicate either the best or second-best performance for each task and model, with the latter occurring only when ToT achieves the best performance.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of four different methods (ToT, CoT, TS-SFT, and CPO) across three types of reasoning tasks (Question Answering, Fact Verification, and Arithmetic Reasoning). The accuracy and latency (in seconds per instance) are reported for each method on several datasets. The * indicates statistically significant improvements compared to the best baseline method (TS-SFT). Bold values indicate the best performance for each task, while values in bold italics represent the second-best when ToT achieves the top performance.

Full paper#