↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Learning optimal regularizers for solving inverse problems and statistical inference tasks is crucial but challenging. Existing data-driven approaches often lack theoretical grounding, hindering the development of more efficient and robust algorithms. This paper tackles this challenge by focusing on a specific family of regularizers, namely, gauges of star-shaped bodies. These regularizers are both expressive enough to represent various types of regularizers and sufficiently tractable for rigorous analysis.

The authors leverage tools from star geometry to develop a framework for analyzing the geometry of regularizers learned from data. They show that optimizing critic-based loss functions, derived from variational representations of statistical distances, is equivalent to solving a dual mixed volume problem. This allows the derivation of exact expressions for the optimal regularizer in certain cases, providing valuable insights into the structure of regularizers learned via these critic-based losses. Furthermore, they identify neural network architectures which induce these star-shaped regularizers and discuss the useful optimization properties they enjoy.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in machine learning and inverse problems. It bridges the gap between empirical success and theoretical understanding of data-driven regularizer learning. By introducing novel tools from star geometry, it provides powerful techniques for analyzing and designing optimal regularizers, opening up new avenues for research in unsupervised regularizer learning and the optimization of non-convex functions. The findings are also highly relevant to current research trends in deep learning and the development of more effective algorithms for solving inverse problems.

Visual Insights#

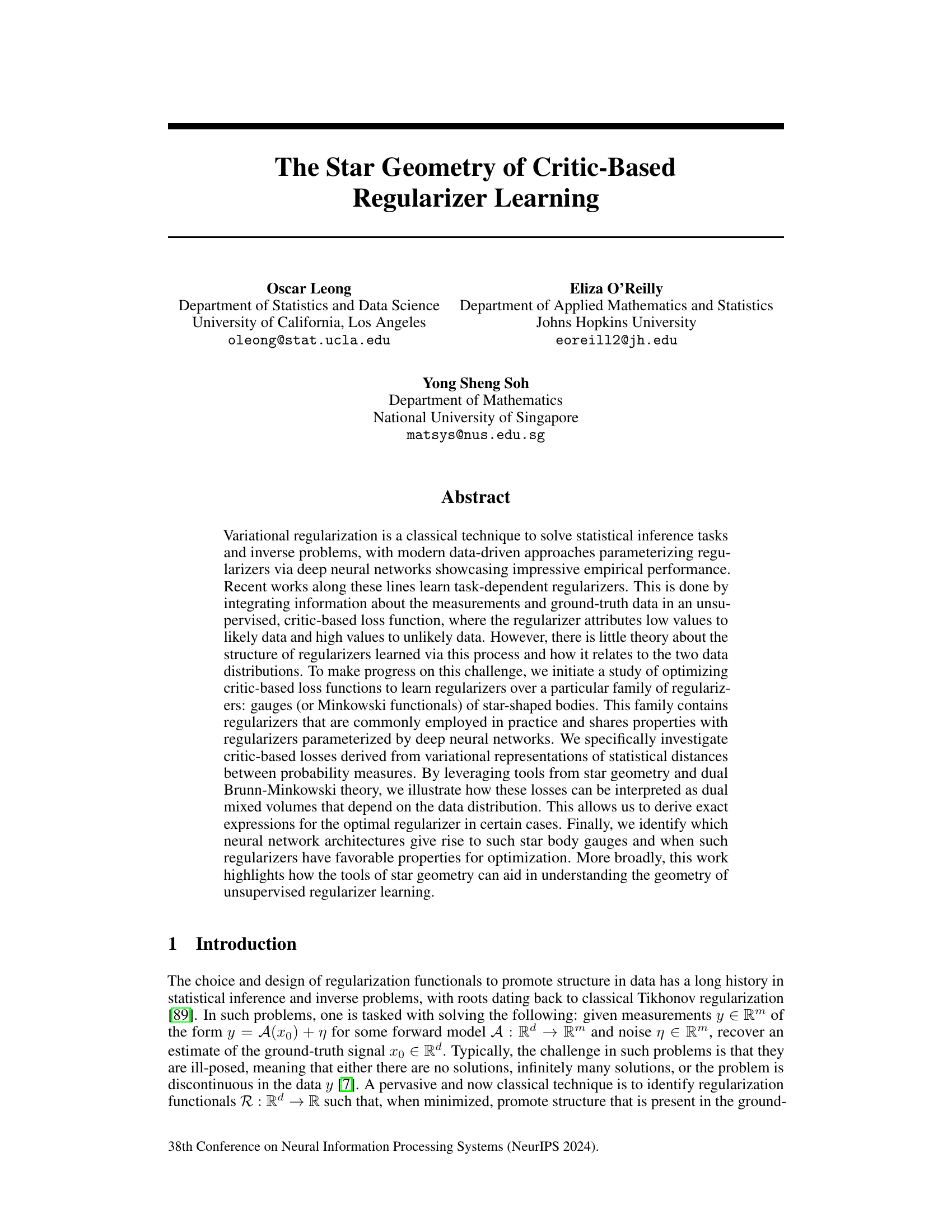

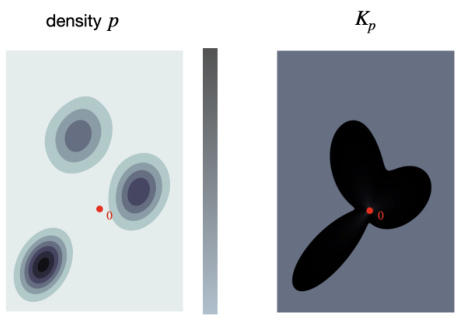

This figure illustrates how the geometry of a data distribution relates to a data-dependent star body. The left panel shows contours of a Gaussian mixture model density, while the right panel shows the star body Kp induced by the radial function defined in equation (3) of the paper. The radial function summarizes the distribution in each unit direction by measuring the average mass and its distance from the origin.

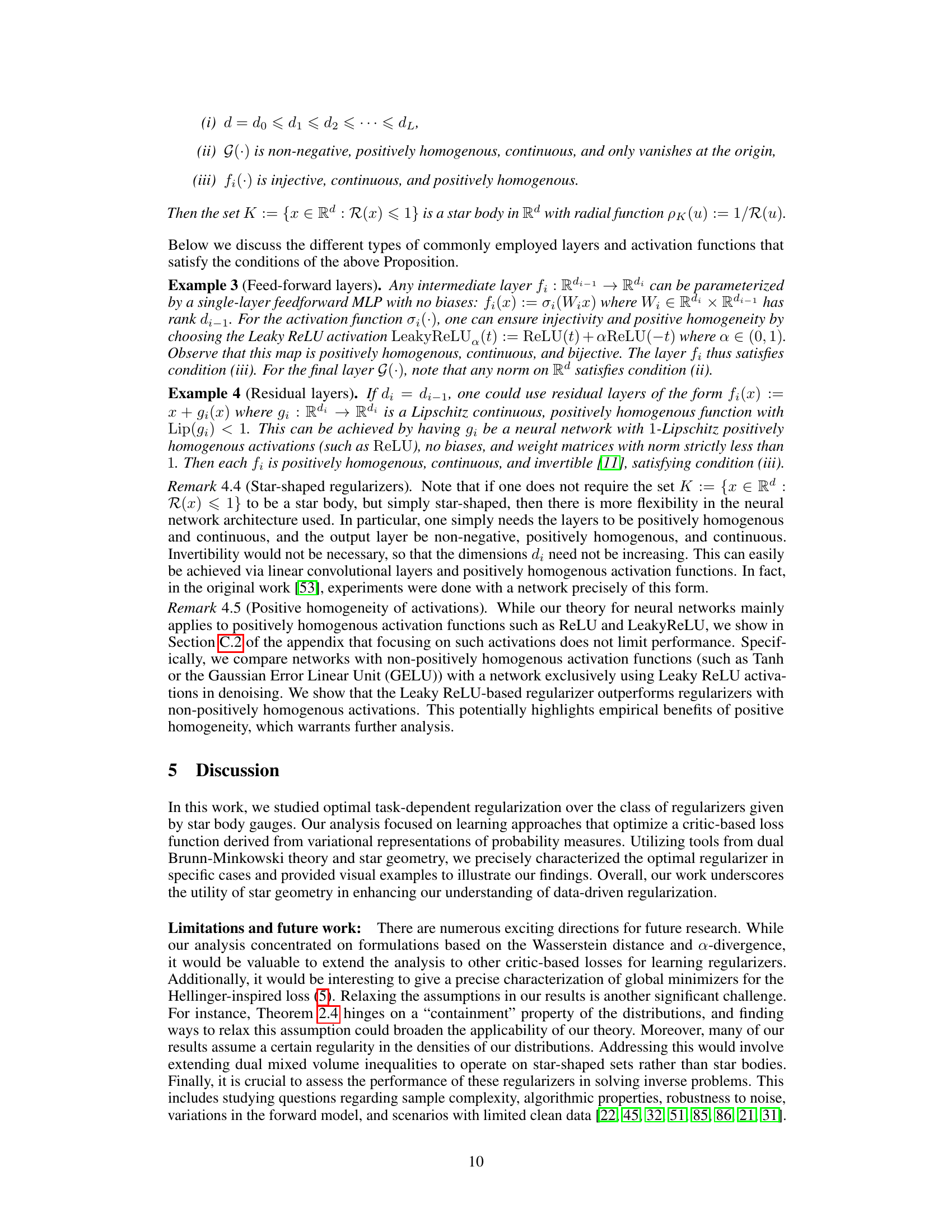

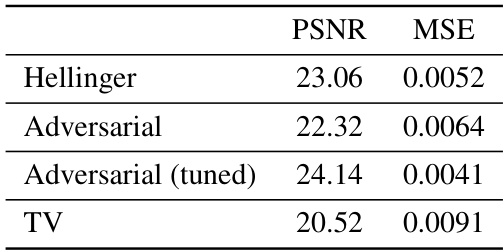

This table compares the performance of three different regularizers (Hellinger, Adversarial, and TV) on the MNIST denoising task, measured by PSNR and MSE. The Adversarial regularizer is tested both with its original and a tuned hyperparameter.

In-depth insights#

Star Body Regularizers#

The concept of “Star Body Regularizers” presents a novel approach to regularization in machine learning, particularly within the context of inverse problems. The core idea revolves around representing regularizers as gauges of star-shaped bodies. This framework offers a flexible and expressive way to capture various types of structure in the data, going beyond the limitations of traditional convex regularizers. The use of star geometry and dual Brunn-Minkowski theory provides a powerful mathematical foundation for analyzing these regularizers. This allows for a deeper understanding of their properties and behavior, enabling characterization of optimal regularizers under specific conditions. A significant advantage is the ability to derive exact expressions for optimal regularizers in certain cases, making the approach theoretically grounded. This approach also connects to neural network architectures, showing how specific network designs can implicitly implement star body gauges. The combination of theoretical rigor and practical applicability makes “Star Body Regularizers” a promising direction for advancing the field of unsupervised regularizer learning. The framework’s extensibility to various divergence-based loss functions further enhances its versatility and potential impact.

Adversarial Learning#

Adversarial learning, a subfield of machine learning, focuses on creating models that improve by competing against each other. This often involves two neural networks, a generator and a discriminator, engaged in a minimax game. The generator attempts to create outputs that are indistinguishable from real data, while the discriminator tries to distinguish between the generated and real data. This creates a feedback loop, constantly improving both networks. Applications are vast, ranging from image generation and style transfer to drug discovery and anomaly detection. A key advantage is that it can generate high-quality, diverse data without relying on extensive labeled datasets, but it also has challenges. Training can be unstable, requiring careful hyperparameter tuning and architecture design to avoid mode collapse or other issues. Evaluating performance can be subjective, particularly when dealing with creative tasks like image generation. However, ongoing research is addressing these issues, with the development of more stable training methods and more objective evaluation metrics. The inherent competitiveness fosters the creation of robust models, which are less susceptible to adversarial attacks than those trained using traditional methods.

f-Divergence Losses#

The concept of f-divergence losses presents a powerful extension to the Wasserstein distance-based adversarial regularization techniques explored in the paper. f-divergences offer a more general framework for measuring the discrepancy between probability distributions, encompassing several well-known divergences like the chi-squared divergence and the Hellinger distance as special cases. This generalized approach allows for a richer exploration of the loss landscape, potentially leading to improved performance and a more nuanced understanding of learned regularizers. The theoretical analysis of f-divergence losses, leveraging dual mixed volume interpretations, provides valuable insights into the geometry of optimal regularizers. The connection between dual mixed volumes and star geometry establishes a more rigorous mathematical foundation, complementing existing empirical observations. Examining specific f-divergences, such as the Hellinger distance, reveals novel loss functionals that show competitive performance in practical applications, highlighting the practical value of this theoretical advancement beyond the Wasserstein distance.

Optimization#

Optimization is a crucial aspect of the research paper, focusing on how to effectively learn regularizers. The paper investigates the use of star-shaped bodies and their gauges as regularizers, offering a theoretically grounded approach. A key challenge is the potential non-convexity of the resulting optimization problems. The authors address this by exploring tools from star geometry and dual Brunn-Minkowski theory, which helps analyze the properties of the objective functions and identify conditions for optimization. Weak convexity is discussed as a desirable property and neural network architectures are analyzed to determine which can efficiently learn star body gauges. The paper explores the use of dual mixed volumes which helps to interpret optimal regularizers and understand properties like uniqueness. The analysis shows how different choices of critic-based loss functions affect the geometry of the resulting optimal regularizers.

Future Directions#

The paper’s core contribution lies in establishing a theoretical framework for understanding how critic-based losses, particularly those derived from statistical distances, shape the geometry of learned regularizers. Future work should explore a broader class of loss functions beyond those based on α-divergences and the Wasserstein distance, potentially investigating losses derived from other statistical divergences or information-theoretic measures. The focus on star-shaped bodies as the regularizer family is insightful, but extending the analysis to more general families of regularizers, including those parameterized by neural networks with non-positive homogeneous activations, would enhance the applicability and practical implications of the findings. While the paper establishes optimality conditions under certain assumptions, future research could address the limitations imposed by these assumptions, relaxing restrictions on data distributions and exploring the behavior of the optimal regularizers in high-dimensional settings. Finally, direct empirical validation and comparative studies involving diverse inverse problems and datasets are crucial to demonstrate the practical effectiveness of the proposed framework. This includes assessing computational efficiency in high-dimensional settings and analyzing the robustness of the approach to noise and modeling errors.

More visual insights#

More on figures

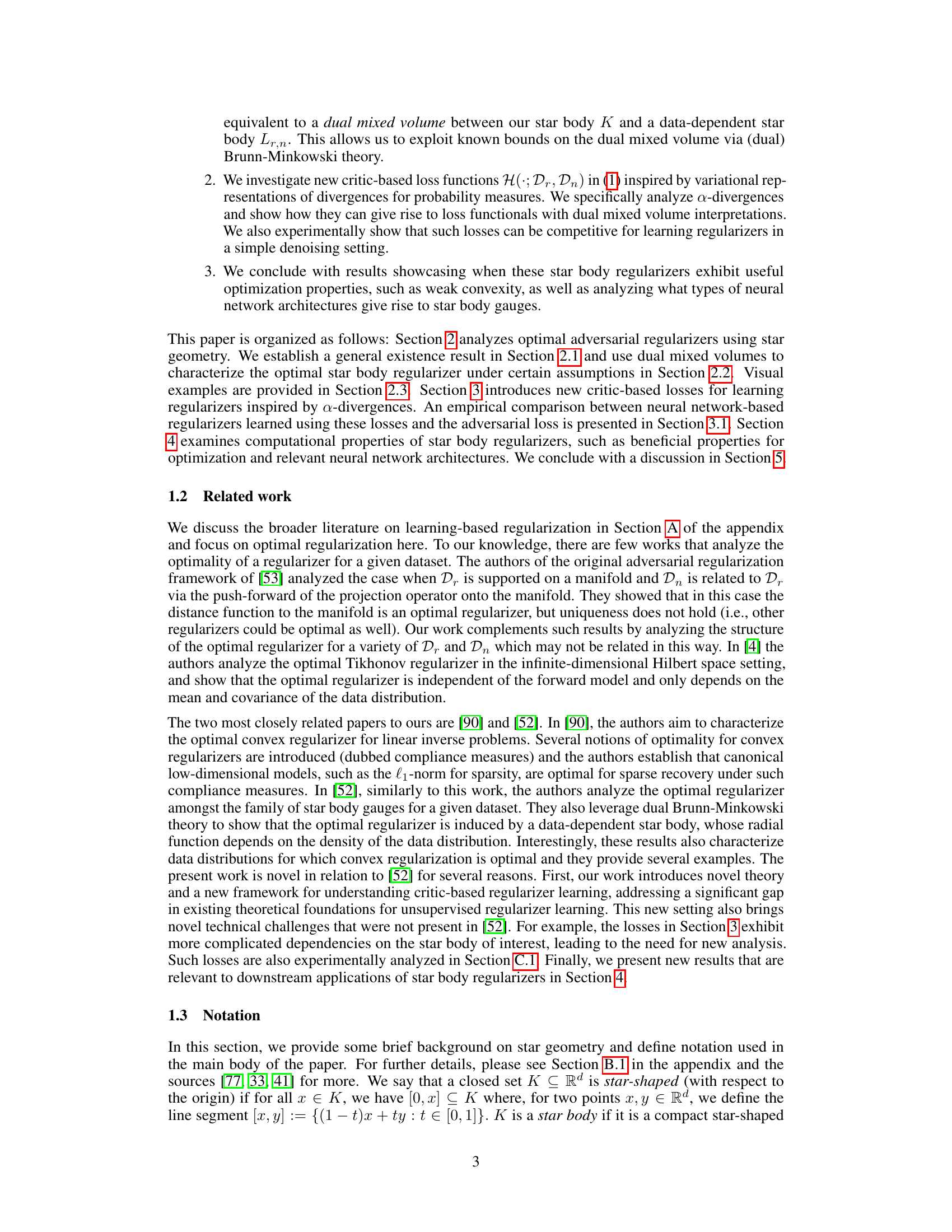

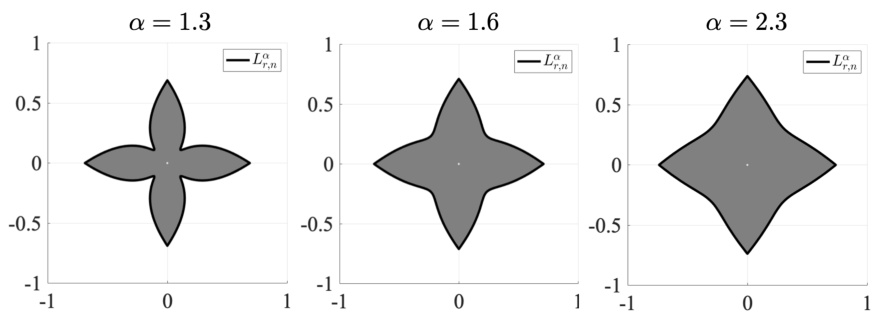

This figure shows the data-dependent star body Lr,n for different values of the parameter α. The star body Lr,n is derived from the dual mixed volume interpretation of the adversarial loss function and depends on the data distributions Dr and Dn. Each subplot represents a different value of α and shows the contours of the corresponding Lr,n. The plots show how the geometry of the data distributions Dr and Dn affects the shape of the optimal regularizer Lr,n.

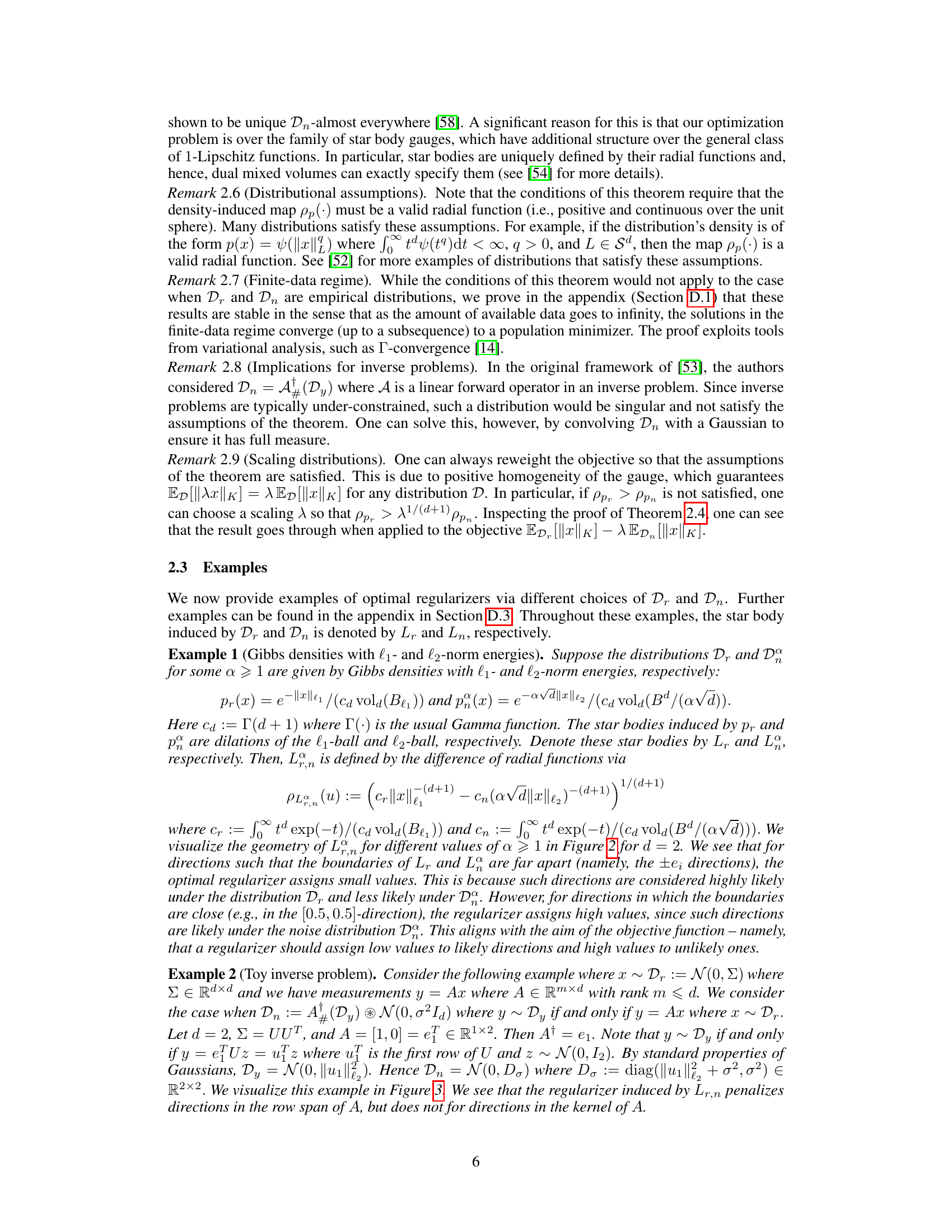

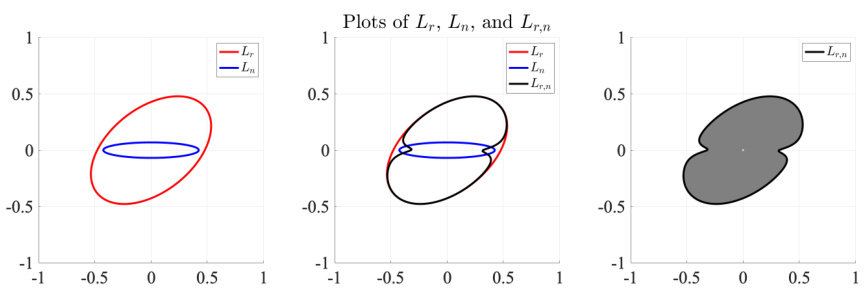

This figure visualizes the distributions from Example 2 in the paper. It shows the star bodies Lr and Ln derived from the data distributions Dr and Dn, respectively. The left panel displays contours of Lr and Ln. The middle panel shows contours of Lr, Ln, and their dual mixed volume Lr,n. The right panel shows the optimal regularizer, Lr,n, which is a function of the two original distributions. This illustrates how the geometry of the data relates to the optimal star body regularizer.

This figure shows three star bodies: Lr, Ln, and K+,λ. Lr and Ln represent the star bodies derived from the distributions Dr (likely data) and Dn (unlikely data), respectively, using the method described in Theorem 3.1 of the paper. K+,λ is the optimal regularizer obtained by minimizing a specific loss function, also detailed in Theorem 3.1. The figure visually demonstrates how the optimal regularizer K+,λ balances the geometry of Lr and Ln; it is larger in regions where Lr dominates and smaller where Ln dominates. K−,λ is also shown to highlight that the optimal regularizer is not simply a dilation of Lr. It demonstrates that K+,λ has the favorable property of assigning low values to likely data and high values to unlikely data, whereas K−,λ does not.

This figure visualizes the data-dependent star bodies Lr,n for different values of the parameter α, which controls the shape of the distributions Dr and Dn. The left column shows the contours of the distributions’ star bodies, Lr and Ln. The middle column adds the contour of the learned regularizer (star body) Lr,n, highlighting how it balances the two data distributions. The right column shows Lr,n alone, illustrating the final regularizer learned for each α.

This figure visualizes the data-dependent star bodies Lr,n obtained from different choices of parameter α. Each row presents the contours of the data distributions (Lr and La), the resulting optimal star body (Lr,n) and the resulting shape Lr,n. This demonstrates how the shape of the optimal regularizer varies with α, showing the flexibility of star-shaped regularizers in capturing different data distributions.

This figure visualizes how the harmonic combination of a star body and a Euclidean ball becomes convex as the parameter p increases. The star body is generated from a Gaussian mixture model, showcasing a data-dependent star body whose squared gauge transitions from nonconvex to weakly convex with increasing p. This illustrates the optimization properties of star body regularizers.

Full paper#