↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current physical adversarial attacks against person detection often neglect the camera’s role, leading to inconsistent results across different devices. This paper points out this limitation. Existing methods struggle to reliably fool detectors across various cameras due to the variations in image processing pipelines.

To overcome these issues, the researchers introduce a novel Camera-Agnostic Patch (CAP) attack. CAP uses a differentiable camera ISP proxy network to simulate the imaging process, bridging the physical-to-digital gap, which is the main contribution of the paper. This, combined with an adversarial optimization framework, enables the generation of more robust and stable adversarial patches. Experiments show CAP’s effectiveness across various cameras and smartphones, significantly improving the success rate of physical adversarial attacks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the limitations of existing physical adversarial attacks by considering the camera’s role in the attack workflow. This opens new avenues for designing more robust and reliable attacks, challenging the security of person detection systems. It also highlights the importance of camera ISP in the physical-to-digital transition and proposes a novel adversarial optimization framework that can be adapted to various imaging devices. The findings will impact research in adversarial attacks, person detection, and camera-agnostic systems.

Visual Insights#

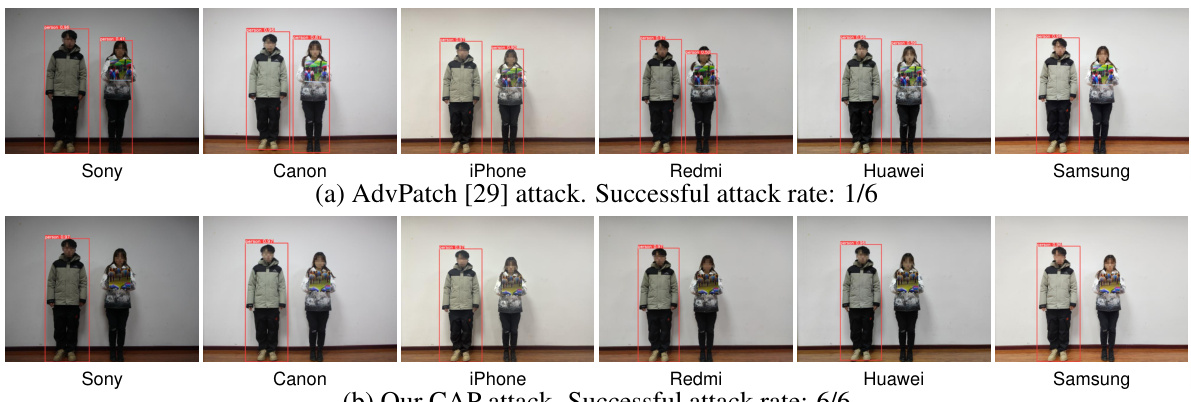

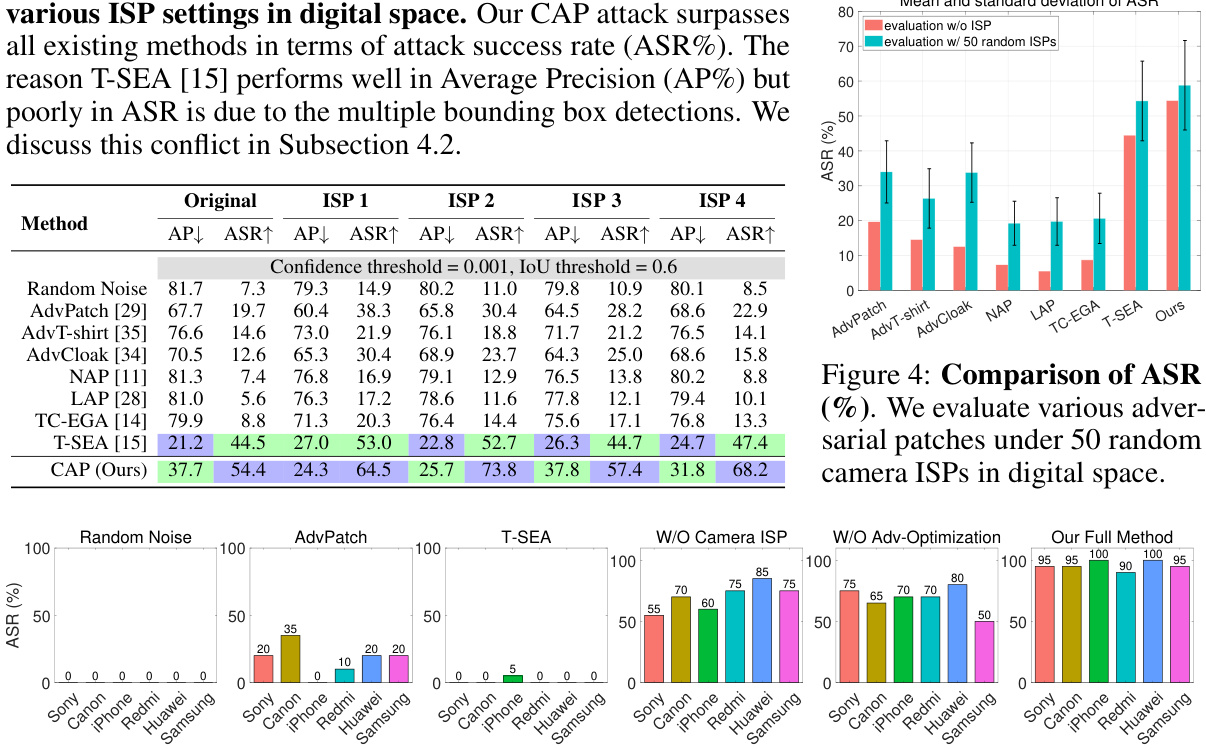

This figure compares the success rate of the AdvPatch attack [29] and the proposed CAP attack across six different cameras (Sony, Canon, iPhone, Redmi, Huawei, and Samsung). The top row shows the results of the AdvPatch attack, which only successfully concealed the person in one out of six camera images. The bottom row displays the results for the CAP attack, showing success across all six cameras, highlighting its camera-agnostic nature and improved robustness.

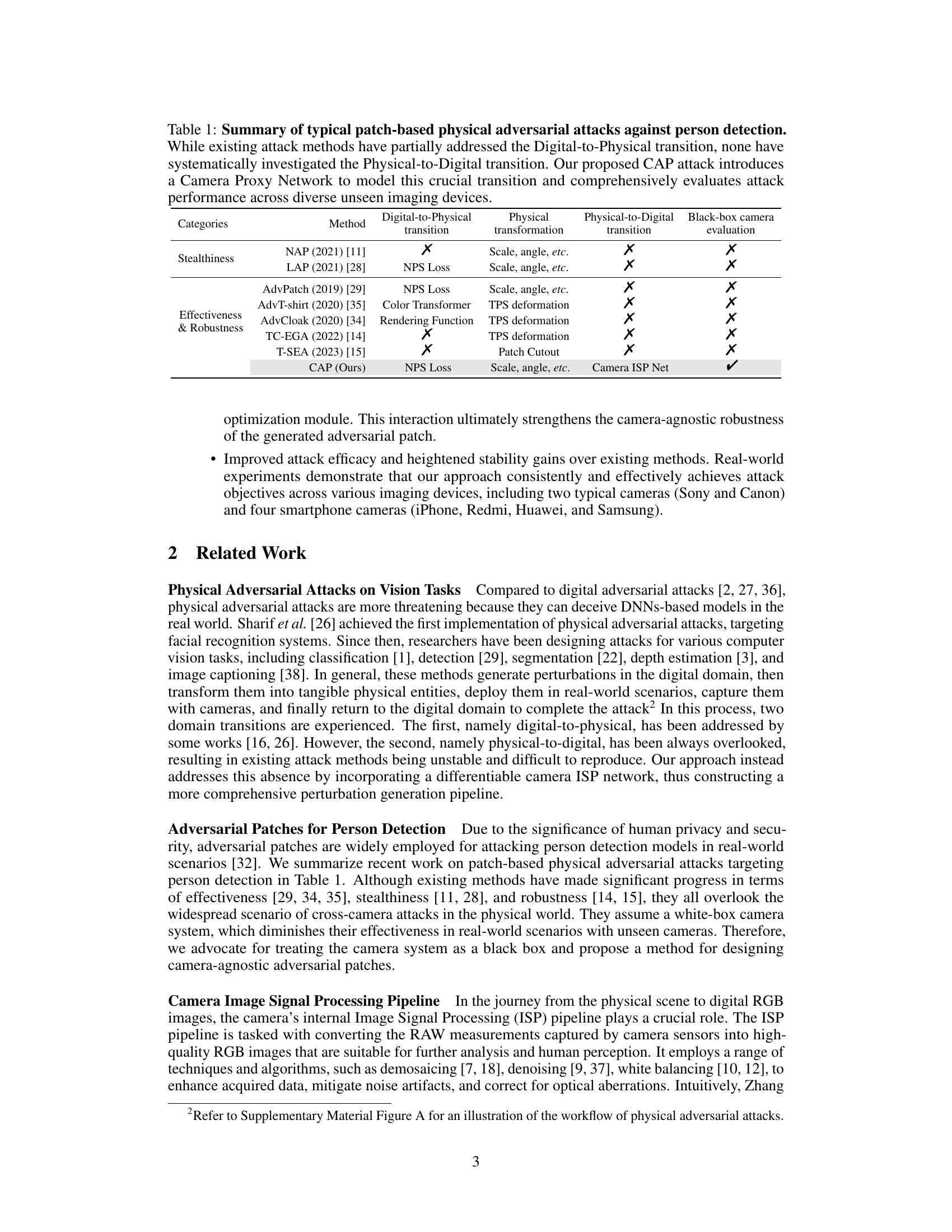

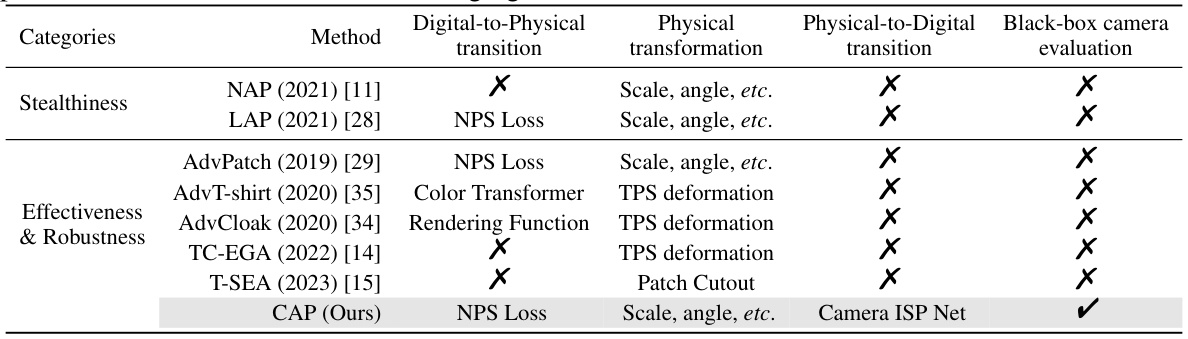

This table compares several existing patch-based physical adversarial attacks against person detection methods. It highlights whether each method considers the digital-to-physical and physical-to-digital transitions, the types of physical transformations used, and whether a black-box camera evaluation was performed. The table emphasizes the novelty of the CAP attack in explicitly addressing the often-overlooked physical-to-digital transition and evaluating performance across diverse cameras.

In-depth insights#

Camera ISP Impact#

The section on ‘Camera ISP Impact’ would explore how the camera’s image signal processing (ISP) pipeline significantly affects the success of physical adversarial attacks. The ISP’s role in converting raw sensor data into a digital image introduces a crucial transformation step often overlooked in prior research. This transformation process can inherently attenuate the effectiveness of adversarial patches, effectively acting as a natural defense mechanism. The analysis would delve into specific ISP components and their impact on adversarial patch visibility. A key insight would be the introduction of a differentiable camera ISP proxy network to model the complex ISP pipeline, which enables the development of camera-agnostic physical adversarial attacks that are robust to variations in imaging hardware. This approach facilitates a novel adversarial optimization framework, where the attack module optimizes adversarial patches to maximize effectiveness, while a defense module optimizes the ISP proxy network to minimize attack effectiveness. The resulting adversarial game enhances the stability and cross-camera generalization capability of the attacks.

Adversarial Patch#

Adversarial patches represent a significant threat to computer vision systems. These small, carefully designed image perturbations, when applied to real-world objects, can fool deep learning models into misclassifying or misdetecting those objects. The effectiveness of adversarial patches stems from their ability to leverage the vulnerabilities of deep neural networks, exploiting subtle features that humans often overlook. Research on adversarial patches explores various methods for generating these patches, including optimization techniques that maximize their effectiveness while maintaining visual stealth. A key challenge lies in transferring these digital attacks to the physical world, where factors like lighting conditions, camera properties, and printing variations can significantly impact their success rate. Therefore, research in this area increasingly emphasizes techniques to enhance the robustness and stability of adversarial patches across diverse real-world conditions. Ultimately, understanding and mitigating the threat of adversarial patches is crucial for ensuring the security and reliability of computer vision systems deployed in safety-critical applications.

Cross-Camera Robustness#

Cross-camera robustness in adversarial attacks focuses on developing attack strategies that consistently deceive person detectors across diverse camera hardware. This is a crucial challenge because real-world camera systems introduce significant variations in image acquisition and processing that can drastically reduce the effectiveness of attacks designed in a controlled environment. Existing approaches often overlook this pivotal physical-to-digital transition stage, neglecting the camera’s crucial role in shaping the final digital image. A robust solution demands a more comprehensive approach, explicitly modeling the camera’s image signal processing (ISP) pipeline to compensate for these variations. By incorporating differentiable ISP proxy networks, researchers can simulate and mitigate the effects of different camera ISPs, leading to attacks that are less susceptible to camera-specific characteristics and achieve greater cross-camera stability. This approach fosters enhanced robustness against real-world deployment conditions, where attackers lack complete control over the imaging setup.

Physical-Digital Gap#

The ‘Physical-Digital Gap’ in adversarial attacks against person detection highlights the critical discrepancy between the physical world and the digital domain within the attack workflow. Existing methods often overlook the camera’s role in bridging this gap, focusing solely on digital perturbation generation and neglecting the transformation of physical patches into digital images. This oversight leads to significant instability in the attacks, as the camera’s image processing pipeline (ISP) can significantly alter the effectiveness of the adversarial patch. The camera acts as an unpredictable variable, introducing a layer of complexity that is not easily accounted for in traditional attack methods. Therefore, addressing the Physical-Digital Gap requires a comprehensive approach that models the camera’s ISP, thereby improving the robustness and reliability of adversarial attacks across diverse camera hardware and settings. A key insight is that treating the camera ISP as a black box limits effectiveness. The camera ISP itself can be a defense mechanism, thus integrating it into the attack design is crucial for creating camera-agnostic attacks and building more robust adversarial examples.

Future Defenses#

Future defenses against adversarial attacks on person detection must move beyond simple countermeasures. Robust solutions need to address the root causes of vulnerability, such as the inherent sensitivity of deep learning models to subtle image manipulations. This suggests exploring new architectural designs for detectors, incorporating robust feature extraction techniques, and developing advanced training methodologies that improve generalization and resilience. Furthermore, research into understanding the interplay between the physical world and the digital domain is crucial. This includes developing more accurate camera ISP models for simulations and considering the real-world effects of lighting, angle, and material properties on adversarial patches. Finally, focus should shift towards proactive security measures, integrated into the system design from the outset, rather than relying solely on reactive defense mechanisms. This holistic approach would encompass hardware and software solutions to mitigate the impact of adversarial attacks effectively.

More visual insights#

More on figures

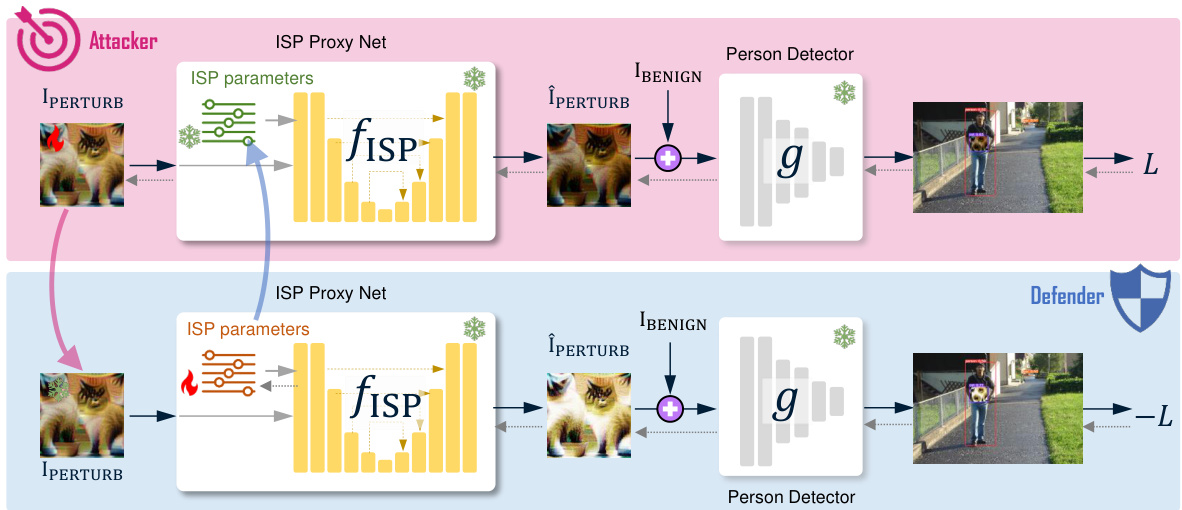

This figure illustrates the adversarial optimization framework used in the paper. It consists of two modules: an attacker and a defender. The attacker module aims to maximize the effectiveness of the adversarial patches by optimizing them. The defender module aims to minimize the effectiveness of the attacks by optimizing the conditional parameters of a camera ISP proxy network. The two modules engage in an iterative process of optimization, with the attacker’s optimization being followed by the defender’s optimization, and this process continuing until convergence or a set number of iterations are reached. The ultimate goal is to create an adversarial patch that is effective across multiple cameras.

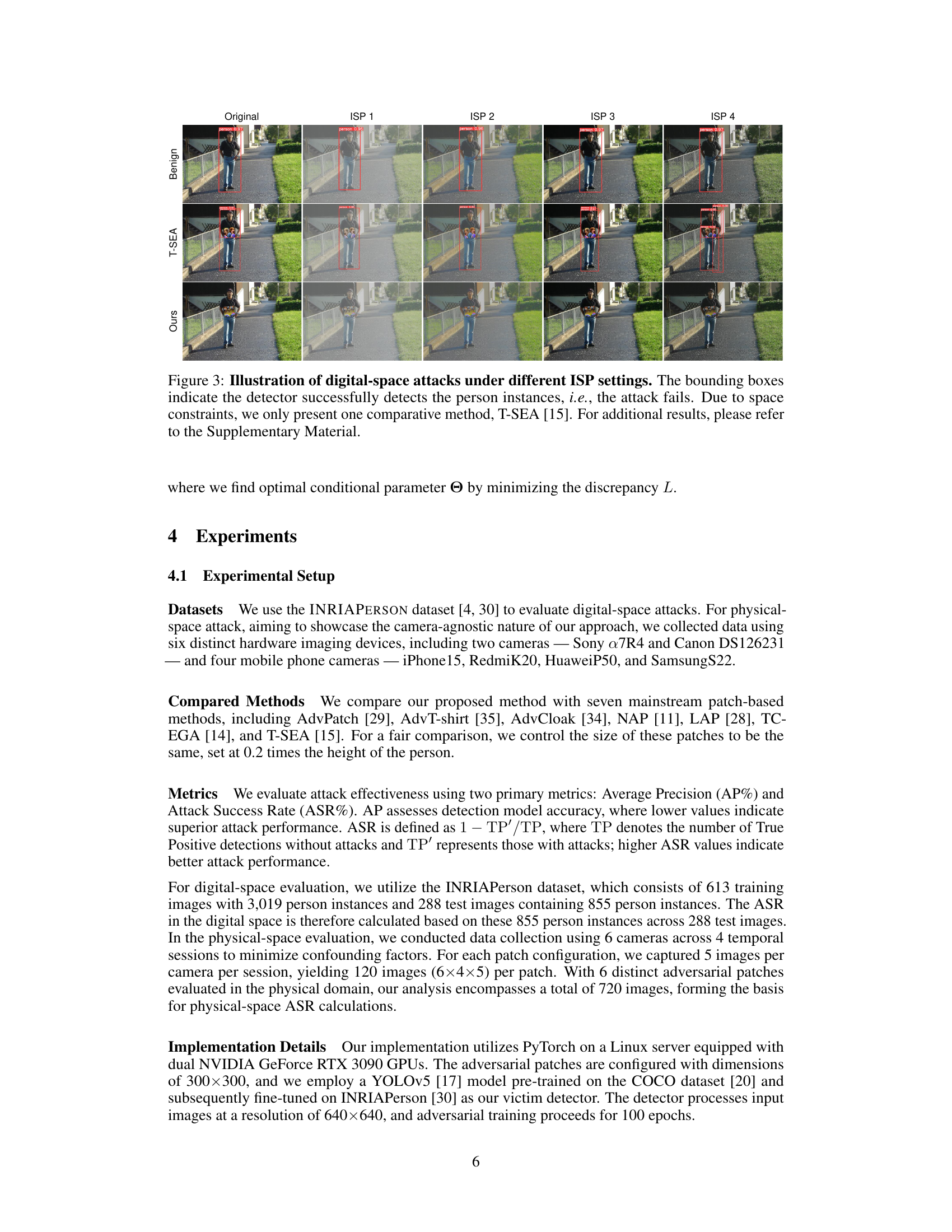

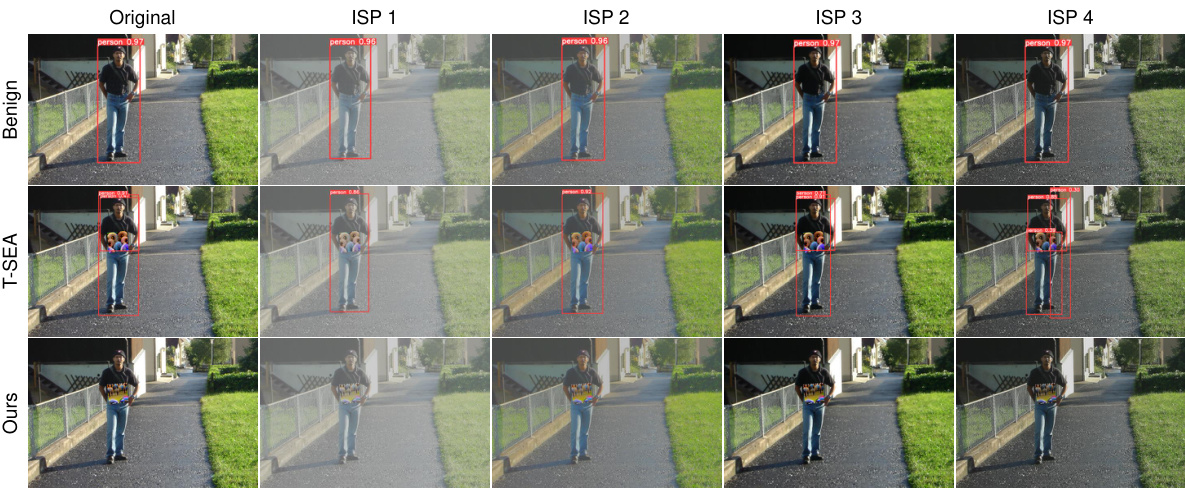

This figure compares the performance of different attack methods in a digital space under various ISP settings. Three rows represent different attack methods: a benign image without attack, T-SEA attack, and the proposed CAP attack. The columns show the detection results under different ISP settings (Original, ISP1, ISP2, ISP3, ISP4), indicated by the bounding boxes around the detected persons. Each setting maintains the same scene. The red boxes indicate successful detection of the person; in contrast, attacks are successful when no bounding boxes are shown. The results illustrate that the CAP attack consistently fails to fool the detector, even under different camera ISP settings, whereas T-SEA occasionally fools the detector.

This figure shows a comparison of the success rate of adversarial attacks against person detection using different cameras. The top row shows the results using the AdvPatch method, where only one out of six cameras successfully concealed the person. The bottom row shows results using the proposed CAP method, where all six cameras successfully concealed the person, demonstrating its camera-agnostic nature.

This figure compares the attack success rate of three different versions of the proposed CAP attack method across six different cameras: Sony, Canon, iPhone, Redmi, Huawei, and Samsung. The three versions are: 1) without the camera ISP module; 2) without adversarial optimization; and 3) the full method (with both camera ISP module and adversarial optimization). The results show that removing either the camera ISP module or the adversarial optimization significantly reduces the attack’s effectiveness and cross-camera consistency. Only the full CAP attack method achieves consistent success across all six cameras.

More on tables

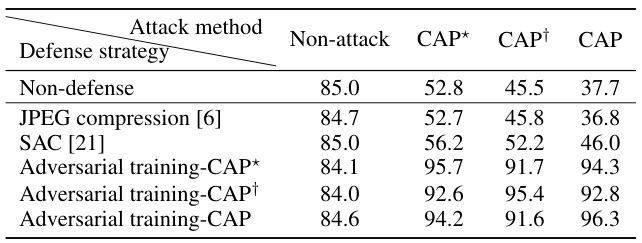

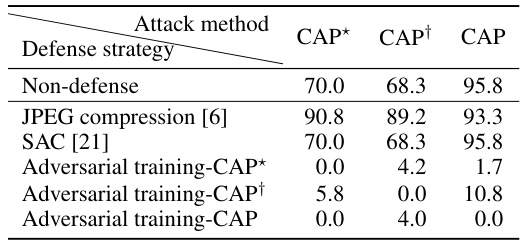

This table presents the results of evaluating three different defense mechanisms against the proposed CAP attack. The Average Precision (AP) metric in the digital space and the Attack Success Rate (ASR) in the physical space are reported for a non-attack baseline and three variations of the CAP attack: CAP*, CAP†, and the full CAP method. CAP* excludes the camera ISP module, CAP† excludes adversarial optimization, and CAP represents the full method. The three defense strategies are JPEG compression, Self-Attentional Classifier (SAC), and adversarial training.

This table presents the results of evaluating three different defense mechanisms against the proposed camera-agnostic patch (CAP) attack. The Average Precision (AP) metric, reflecting the accuracy of person detection, is measured in a digital setting. The Attack Success Rate (ASR), indicating the effectiveness of the attack, is assessed in a physical context. The three defense strategies compared are JPEG compression, Self-Attentional Convolutional network (SAC), and adversarial training. The table shows how each defense strategy affects the CAP attack’s performance (both variants and the full method), providing a quantitative comparison of their effectiveness in mitigating the attack.

Full paper#