↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current incremental learning methods struggle with fine-grained compositionality, neglecting various states (e.g., color, material) attached to objects. This leads to limitations in recognizing state-object compositions and handling ambiguous boundaries. This paper introduces a new task called Compositional Incremental Learning (composition-IL) and proposes CompILer, a prompt-based model that addresses these challenges.

CompILer uses multi-pool prompt learning to learn states, objects, and compositions separately. It incorporates object-injected state prompting, guiding state selection. The selected prompts are fused using generalized-mean fusion to eliminate irrelevant information. Experiments show CompILer achieves state-of-the-art performance, demonstrating its ability to learn new compositions incrementally without forgetting previous knowledge. The paper also contributes by reorganizing two existing datasets and making them suitable for composition-IL.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel task, Compositional Incremental Learning (composition-IL), addressing limitations in existing incremental learning approaches. By focusing on the compositionality of state-object pairs, it enables models to reason more effectively about fine-grained relationships and avoid catastrophic forgetting. The proposed CompILer model, using multi-pool prompt learning, object-injected state prompting, and generalized-mean prompt fusion, shows state-of-the-art results, paving the way for future research on continual learning with rich compositionality and fine-grained state recognition.

Visual Insights#

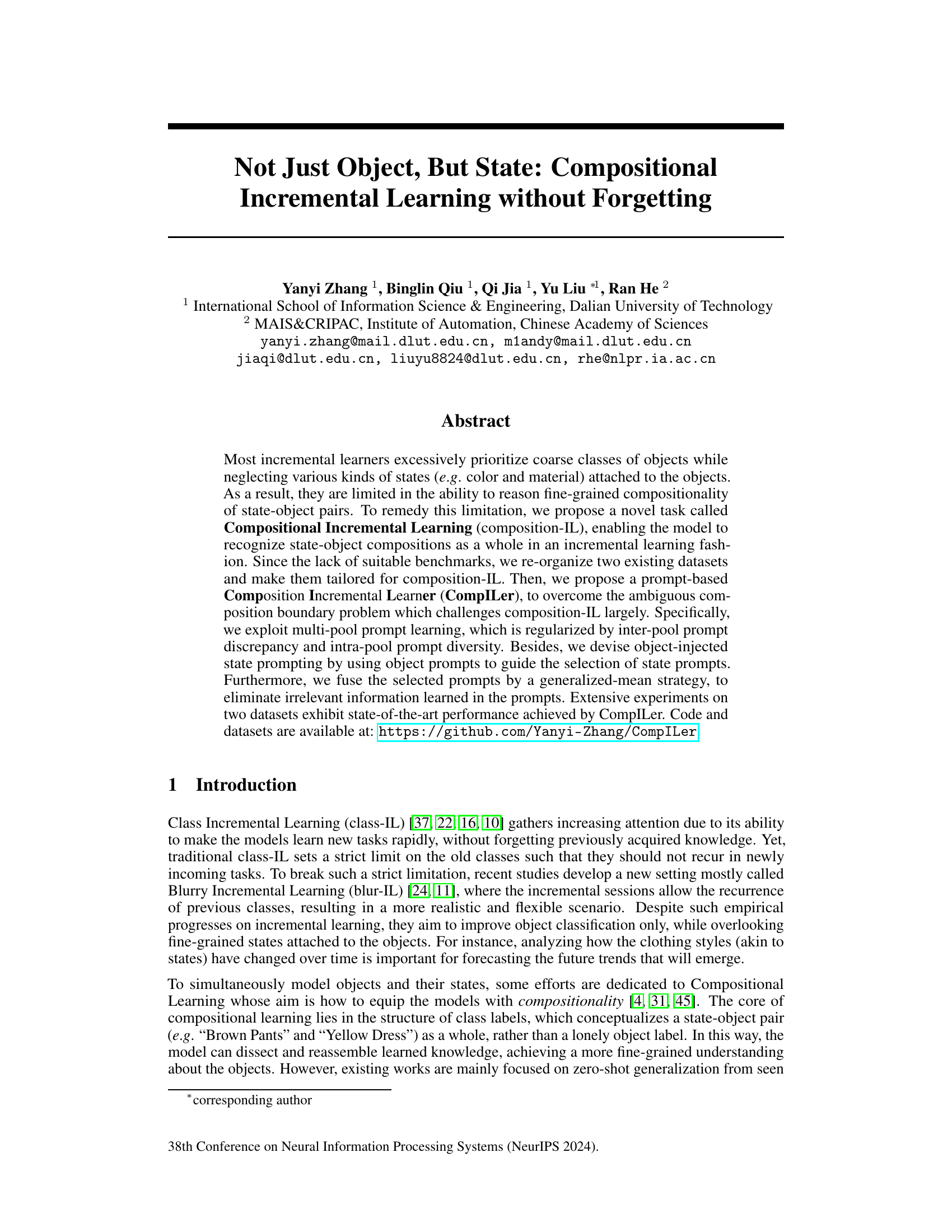

This figure illustrates the differences between three incremental learning paradigms: Class Incremental Learning (class-IL), Blurry Incremental Learning (blur-IL), and Compositional Incremental Learning (composition-IL). Class-IL strictly prohibits the recurrence of previously seen object classes in new tasks. Blur-IL relaxes this constraint, allowing for the random reappearance of previously seen classes. Composition-IL focuses on learning state-object compositions (e.g., ‘brown pants’, ‘yellow dress’). While object and state primitives can reappear across tasks, the specific state-object combinations are unique to each task, preventing redundancy. This visual comparison helps to understand the novel compositional incremental learning problem introduced in the paper.

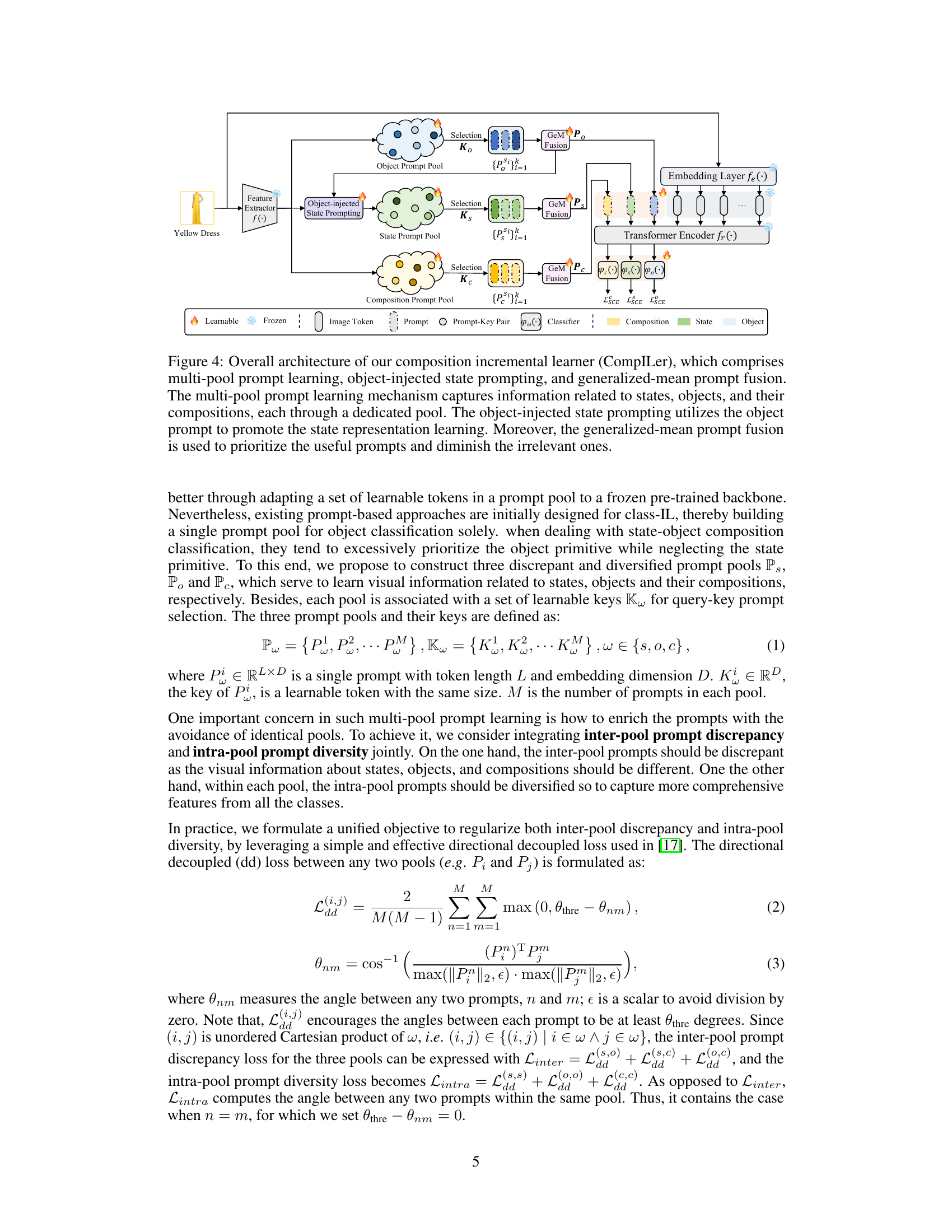

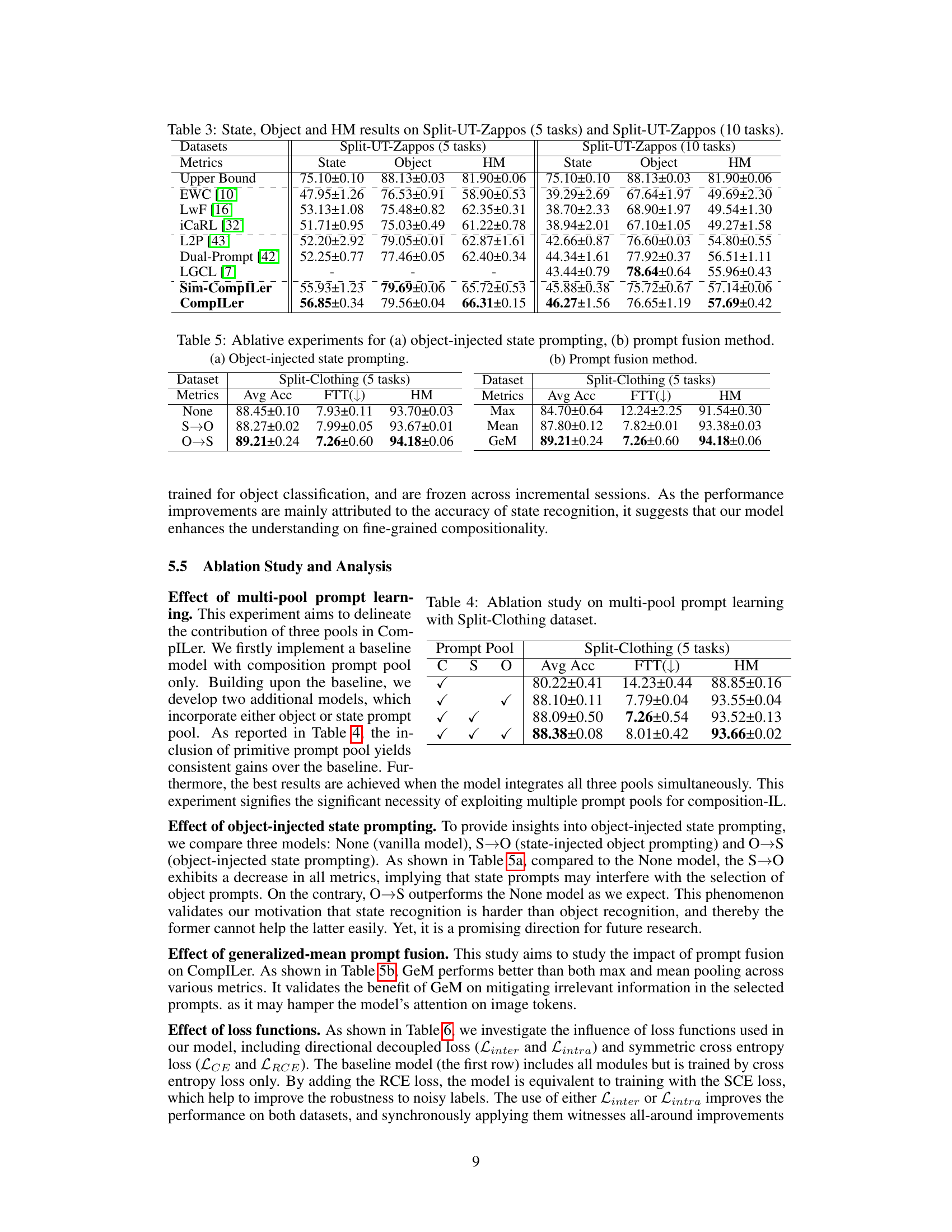

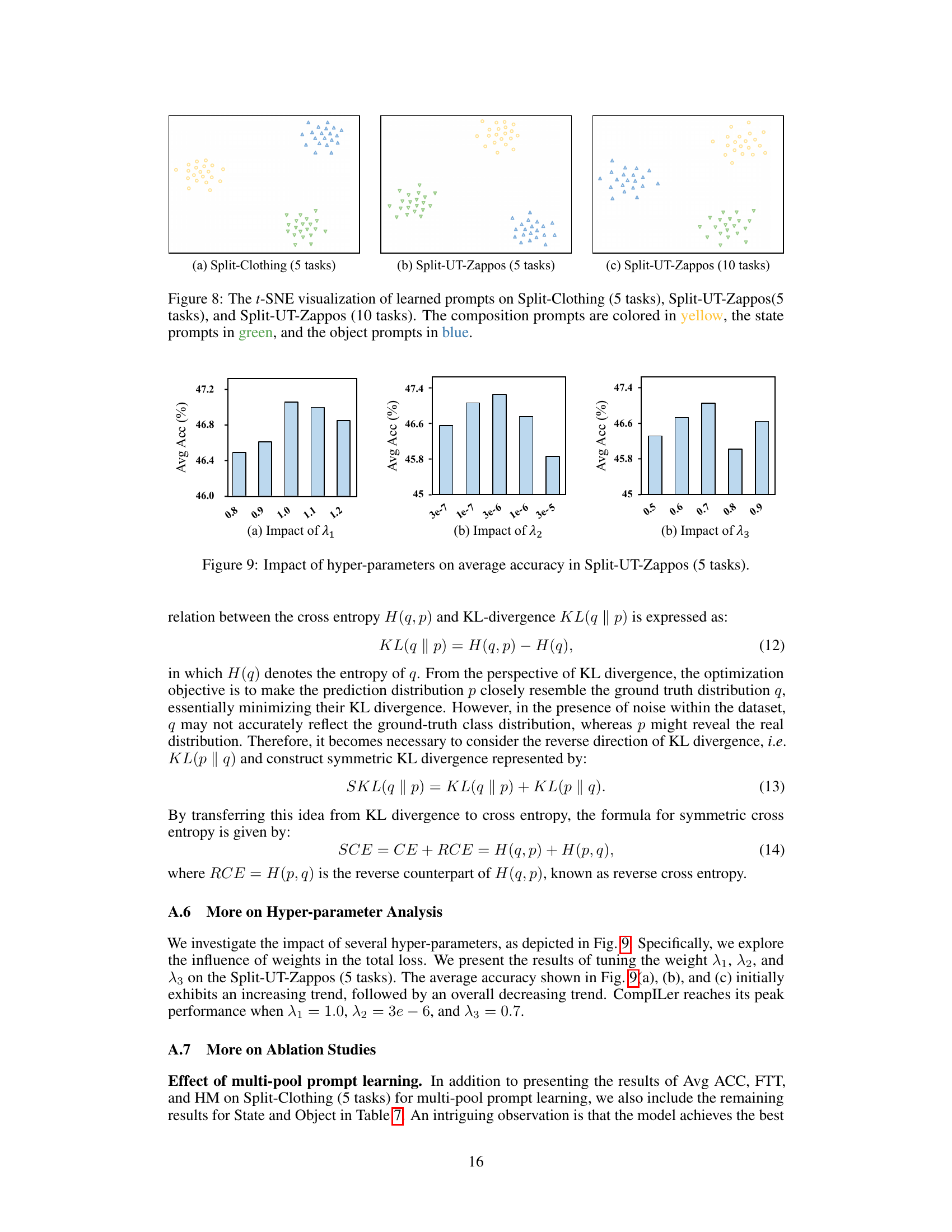

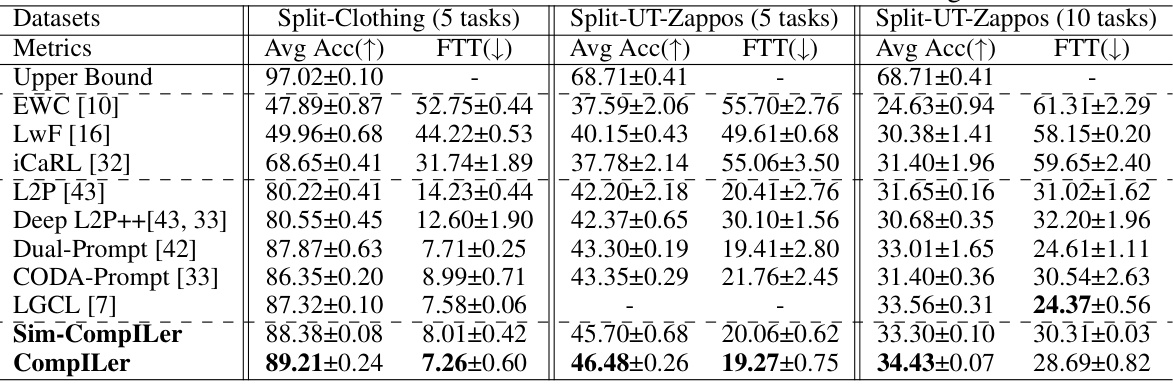

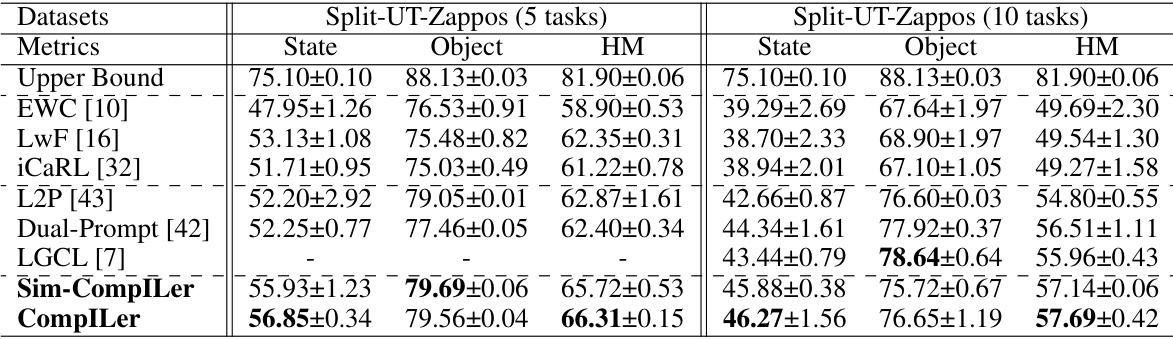

This table presents a comparison of the performance of various incremental learning methods on two datasets: Split-Clothing (with 5 incremental tasks) and Split-UT-Zappos (with both 5 and 10 incremental tasks). The metrics used are Average Accuracy (Avg Acc), which measures the overall classification accuracy, and Forgetting Rate (FTT), which assesses the degree of catastrophic forgetting. The table shows that CompILer outperforms other methods in most cases, demonstrating its effectiveness in compositional incremental learning.

In-depth insights#

Compositional IL#

Compositional Incremental Learning (Compositional IL) presents a novel approach to incremental learning by focusing on the compositionality of state-object pairs. Unlike traditional class incremental learning which primarily focuses on object classes, Compositional IL addresses the limitations of neglecting the nuanced states associated with objects. This is particularly crucial for complex real-world scenarios where understanding the interactions between object attributes (like color or material) and the object itself is essential. The core idea is that the model learns to recognize state-object compositions as holistic entities. This requires overcoming the challenge of ambiguous composition boundaries, a problem that Compositional IL directly tackles through innovative techniques like prompt-based learning. This approach not only improves the fine-grained understanding of compositions but also enhances the model’s ability to reason about unseen compositions incrementally, thus avoiding catastrophic forgetting. A key strength of Compositional IL lies in its suitability for real-world applications where objects possess numerous attributes and continually new combinations of object and state emerge.

Prompt-based Learner#

A prompt-based learner leverages the power of prompts to guide the learning process, offering a flexible and efficient approach to various machine learning tasks. Prompts act as instructions or constraints, shaping the model’s behavior and directing its attention towards specific aspects of the data. This approach is particularly effective in scenarios with limited data, where explicitly providing instructions or examples through prompts can significantly improve performance. The effectiveness of a prompt-based learner heavily depends on prompt design and selection. Well-crafted prompts can lead to remarkable results, while poorly designed ones can hinder performance. Additionally, prompt engineering is a crucial component of a prompt-based system, requiring careful consideration of the task, data, and model architecture. A successful prompt-based learner often combines prompt engineering with advanced techniques such as prompt tuning, multi-task learning, or transfer learning to further enhance its capabilities and address various challenges.

Ambiguous Boundaries#

The concept of “ambiguous boundaries” in compositional incremental learning highlights a critical challenge: models struggle to distinguish between compositions that share the same object but differ in state. This ambiguity arises because existing methods prioritize object recognition over state recognition, leading to indistinguishable compositions. For example, a model might confuse “red shirt” and “blue shirt”, failing to capture the state (color) information effectively. This problem is further exacerbated in incremental learning settings, where the model continually learns new compositions. Addressing this requires novel approaches that give equal importance to states and objects. Prompt-based methods offer a potential solution by learning state and object representations independently, providing better boundary separation between similar compositions.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore more sophisticated prompt engineering techniques, such as incorporating hierarchical or relational prompts to better capture the complex relationships between objects and their states. Investigating alternative prompt fusion methods beyond generalized-mean pooling, perhaps incorporating attention mechanisms or other neural network architectures, could further improve performance. Another promising area is developing more robust and diverse datasets for compositional incremental learning, addressing the challenges of long-tailed distributions and ambiguous composition boundaries. Finally, exploring the application of compositional incremental learning to different domains and tasks beyond object recognition, such as natural language processing or time-series analysis, would open exciting new avenues for research and development.

Limitations of CompILer#

While CompILer demonstrates state-of-the-art performance in compositional incremental learning, several limitations warrant consideration. The reliance on a pre-trained backbone limits adaptability to different domains and may hinder generalization to unseen object or state types. The multi-pool prompt learning strategy, while effective, introduces a larger number of parameters, increasing computational cost and potentially making it less memory efficient. Furthermore, the success of object-injected state prompting depends on the quality of object feature extraction, suggesting potential limitations when dealing with ambiguous or poorly defined object classes. The dataset construction methodology, involving re-organization of existing datasets, introduces potential bias and may not fully represent the complexities of real-world scenarios. Finally, the current experimental scope could be broadened. More comprehensive testing across a wider variety of datasets and tasks would offer stronger validation of the approach’s generality and robustness.

More visual insights#

More on figures

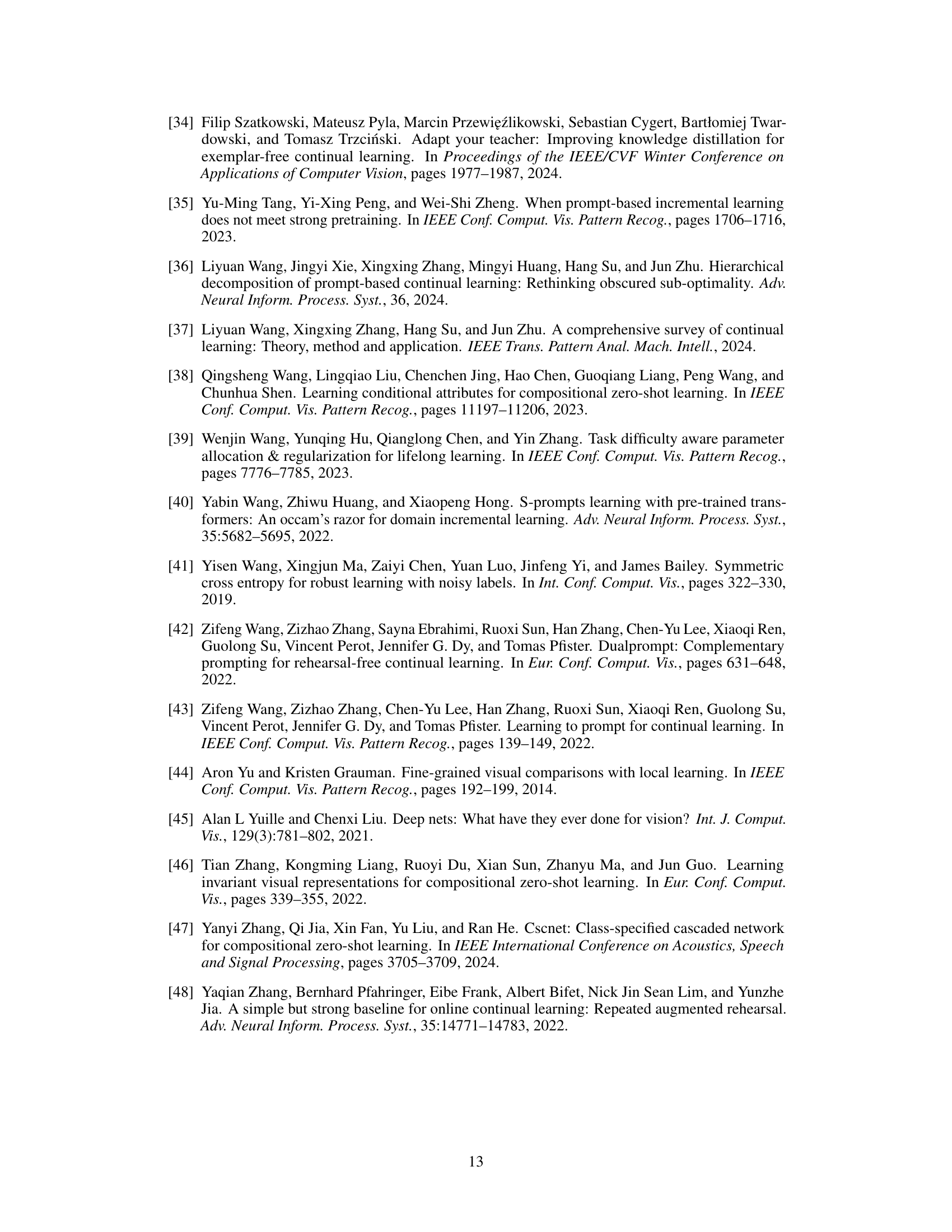

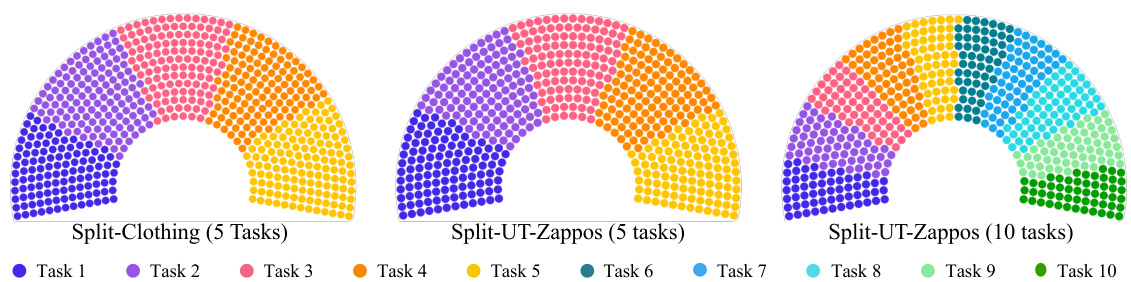

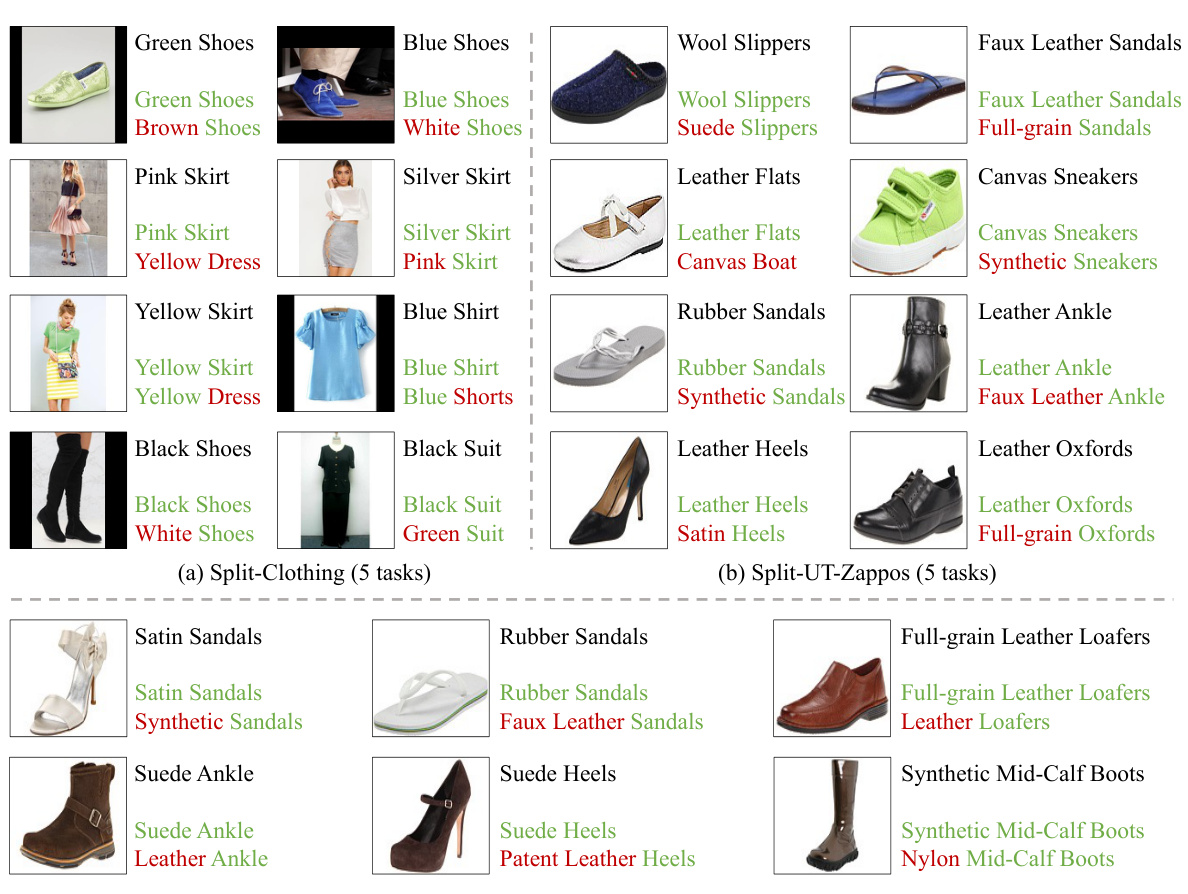

This figure shows the data distribution for the three experimental settings used in the paper: Split-Clothing (5 tasks), Split-UT-Zappos (5 tasks), and Split-UT-Zappos (10 tasks). Each setting is represented by a semicircular chart, divided into sections corresponding to the different tasks. The size of each section is proportional to the number of images in that task. The figure demonstrates that the number of images per task is relatively balanced across all three experimental settings. This ensures a fair comparison between different tasks and experimental setups.

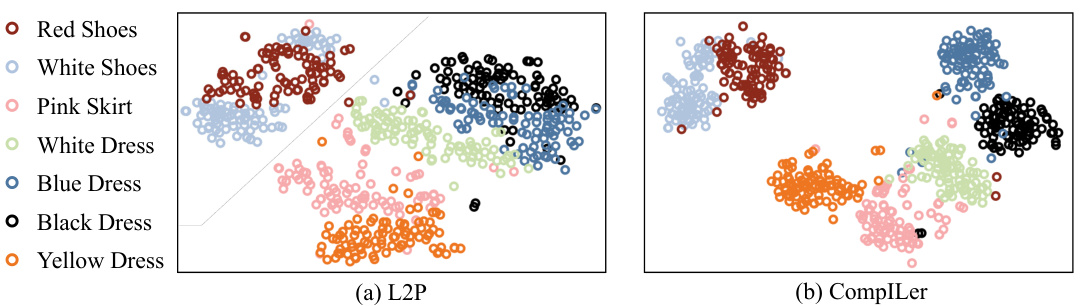

This figure uses t-SNE to visualize the feature distributions of seven compositions from the Split-Clothing dataset learned by both the L2P and CompILer models. The visualization shows that CompILer is better able to distinguish between compositions that share the same object but differ in state (e.g., different colors of dresses). This highlights CompILer’s improved ability to model fine-grained compositionality compared to L2P.

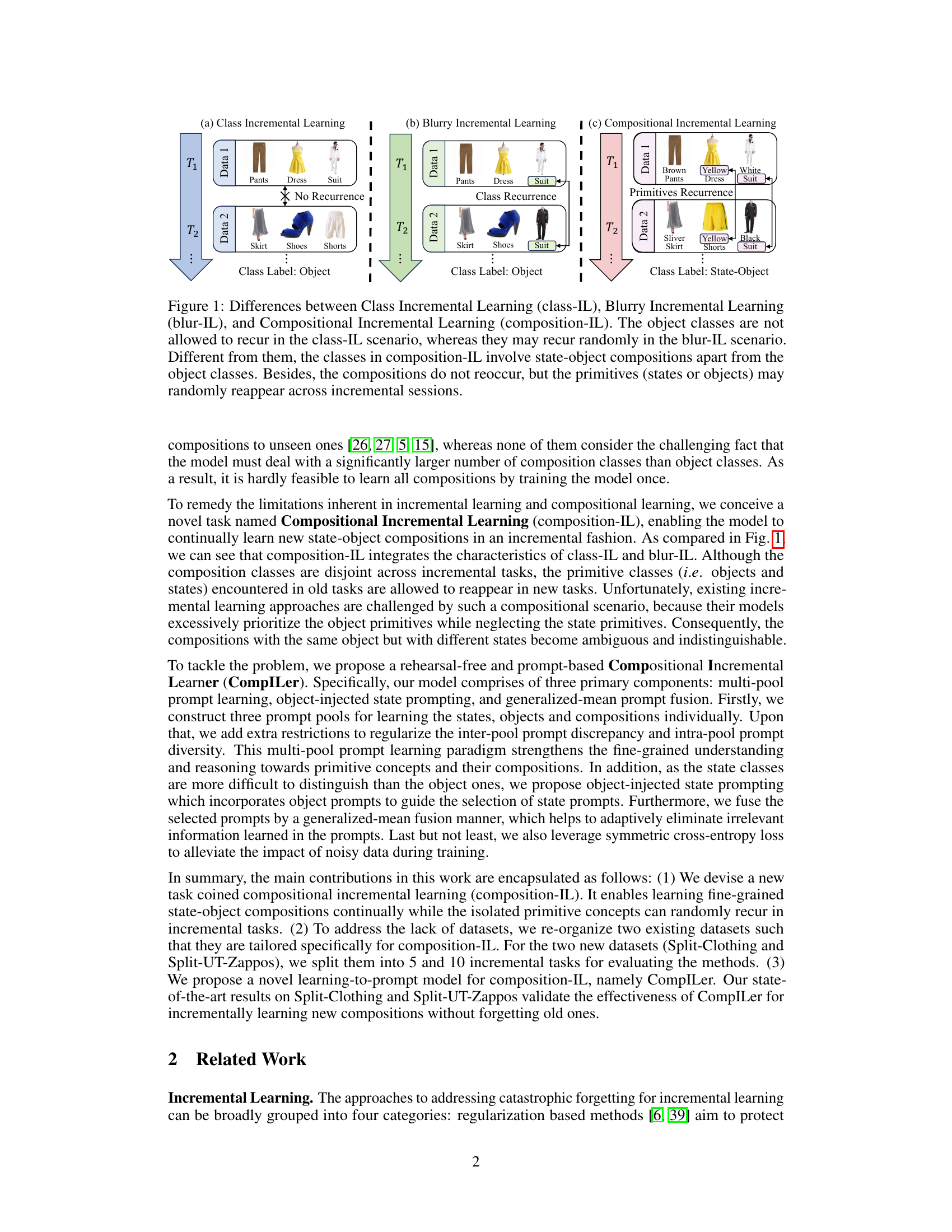

This figure illustrates the architecture of the CompILer model, which is designed for Compositional Incremental Learning. The model consists of three main components: 1) Multi-pool prompt learning that uses separate prompt pools for states, objects, and compositions; 2) Object-injected state prompting, which uses object prompts to guide the selection of state prompts; and 3) Generalized-mean prompt fusion, which combines the selected prompts to reduce irrelevant information. The figure shows how the different components interact, starting with feature extraction from an image and ending with classification based on the fused prompts.

This figure illustrates the object-injected state prompting mechanism. A query feature vector, q(x), representing the input image, acts as the query (Q) in a cross-attention layer. The fused object prompt (Po), a composite of learned prompts representing object features, simultaneously serves as both the key (K) and value (V) vectors in this cross-attention operation. The output of the cross-attention is a refined query feature, qs(x), which is object-informed and used for selecting state prompts. This injection of object information helps to guide the selection of relevant state prompts, improving the state representation learning process.

This figure presents a comprehensive analysis of the CompILer model’s performance on the Split-Clothing dataset across different incremental learning tasks. Subfigures (a), (b), and (c) visualize the accuracy trends for composition, state, and object recognition, respectively, as new tasks are added. Darker colors represent higher accuracy. Subfigure (d) provides a qualitative comparison of CompILer and the L2P baseline predictions on example images. Green indicates correctly classified instances, red indicates errors.

This figure shows the data distribution for the two datasets used in the paper for evaluating compositional incremental learning (composition-IL). Split-Clothing is divided into 5 incremental tasks, while Split-UT-Zappos is divided into both 5 and 10 incremental tasks. The number of images per task is shown in bar graphs for each dataset and task split scenario. The key observation is that the number of images per task is balanced across tasks for all scenarios.

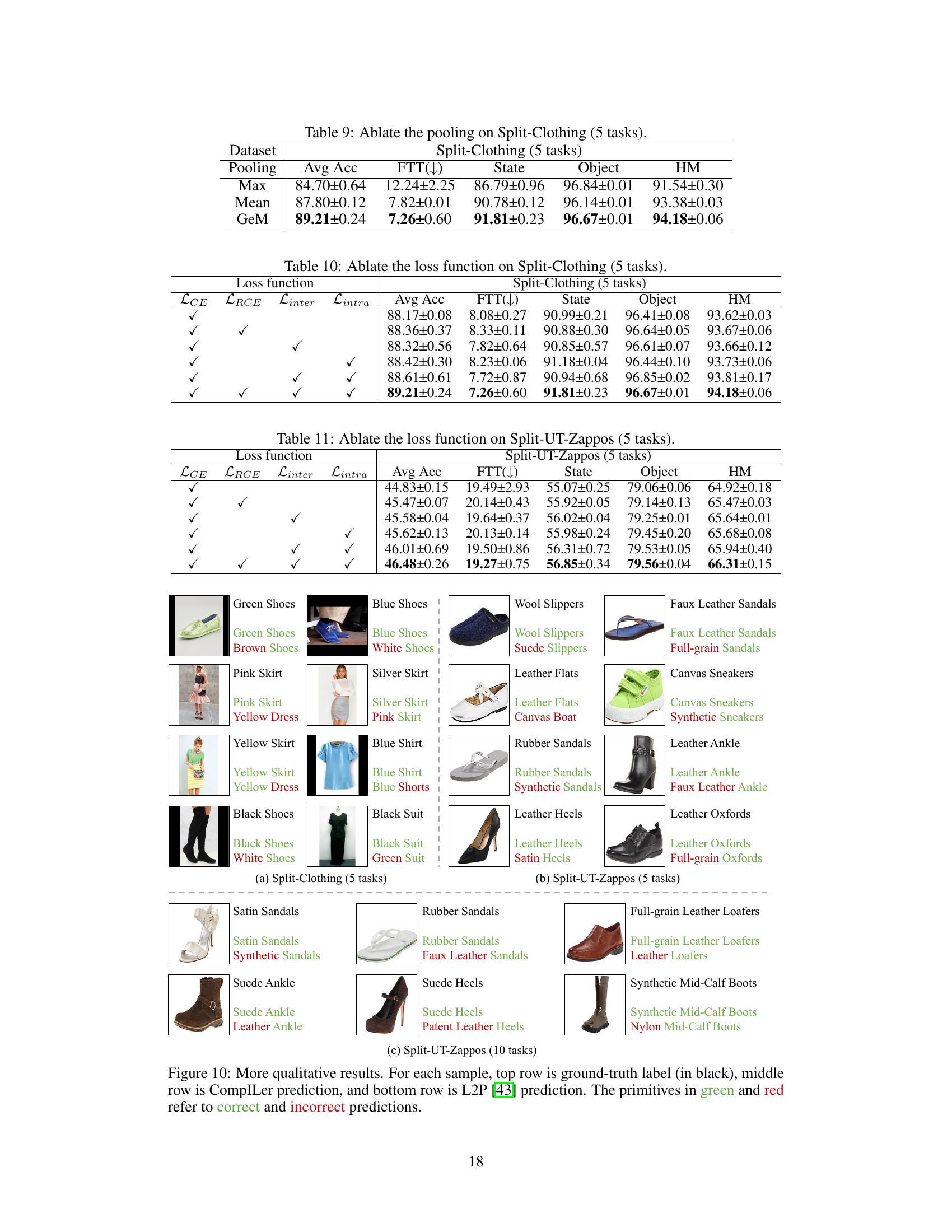

This figure shows the t-SNE visualization of the learned prompts for three different datasets: Split-Clothing (5 tasks), Split-UT-Zappos (5 tasks), and Split-UT-Zappos (10 tasks). The visualization helps illustrate the separation of prompts learned for compositions, states, and objects. Different colors represent different types of prompts: yellow for composition, green for state, and blue for object. The separation demonstrates the effectiveness of the multi-pool prompt learning in distinguishing between these concepts.

This figure shows the effect of hyperparameters (λ₁, λ₂, and λ₃) on the average accuracy of the model in the Split-UT-Zappos dataset with 5 tasks. Each sub-figure displays the average accuracy achieved for different values of a single hyperparameter, while keeping the others constant. It helps understand the sensitivity of the model’s performance to the tuning of these parameters.

This figure compares three incremental learning paradigms: class-IL, blurry-IL, and compositional-IL. Class-IL strictly prohibits the recurrence of old classes in new tasks. Blurry-IL allows old classes to reappear randomly. Compositional-IL focuses on learning state-object compositions (e.g., ‘brown pants’). While compositions themselves don’t reappear, the individual object and state primitives can.

More on tables

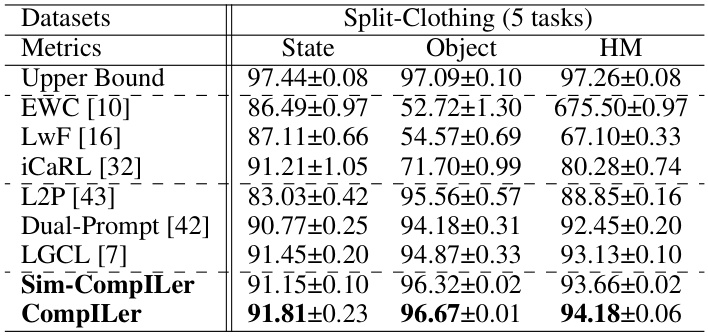

This table presents the performance comparison of different incremental learning methods on the Split-Clothing dataset in terms of average accuracy for state classification, object classification and their harmonic mean. The results are shown for five incremental tasks. The ‘Upper Bound’ represents the performance of a model trained on the entire dataset. The table helps to understand the performance differences between methods and illustrates the effectiveness of the proposed CompILer.

This table presents the average accuracy (Avg Acc) and forgetting rate (FTT) for different incremental learning methods on two datasets: Split-Clothing (5 tasks) and Split-UT-Zappos (5 and 10 tasks). The results show the performance of various algorithms in terms of their ability to classify compositions while minimizing forgetting. The ‘Upper Bound’ represents the best possible accuracy achievable with full training data, providing a benchmark for comparison. Bold values highlight the best-performing method for each metric.

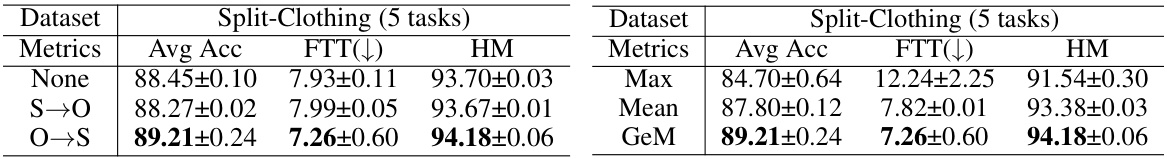

This table presents the ablation study results for two key components of the CompILer model: object-injected state prompting and generalized-mean prompt fusion. It shows the impact of these components on the model’s performance, measured by Average Accuracy (Avg Acc), Forgetting (FTT), and Harmonic Mean (HM) across different experimental settings on the Split-Clothing dataset. The ‘None’ row represents the baseline model without these components. The ‘S→O’ and ‘O→S’ rows represent experiments where state prompts guide object prompt selection and vice versa, respectively. The Max, Mean, and GeM rows show experiments using different fusion strategies for combining the selected prompts.

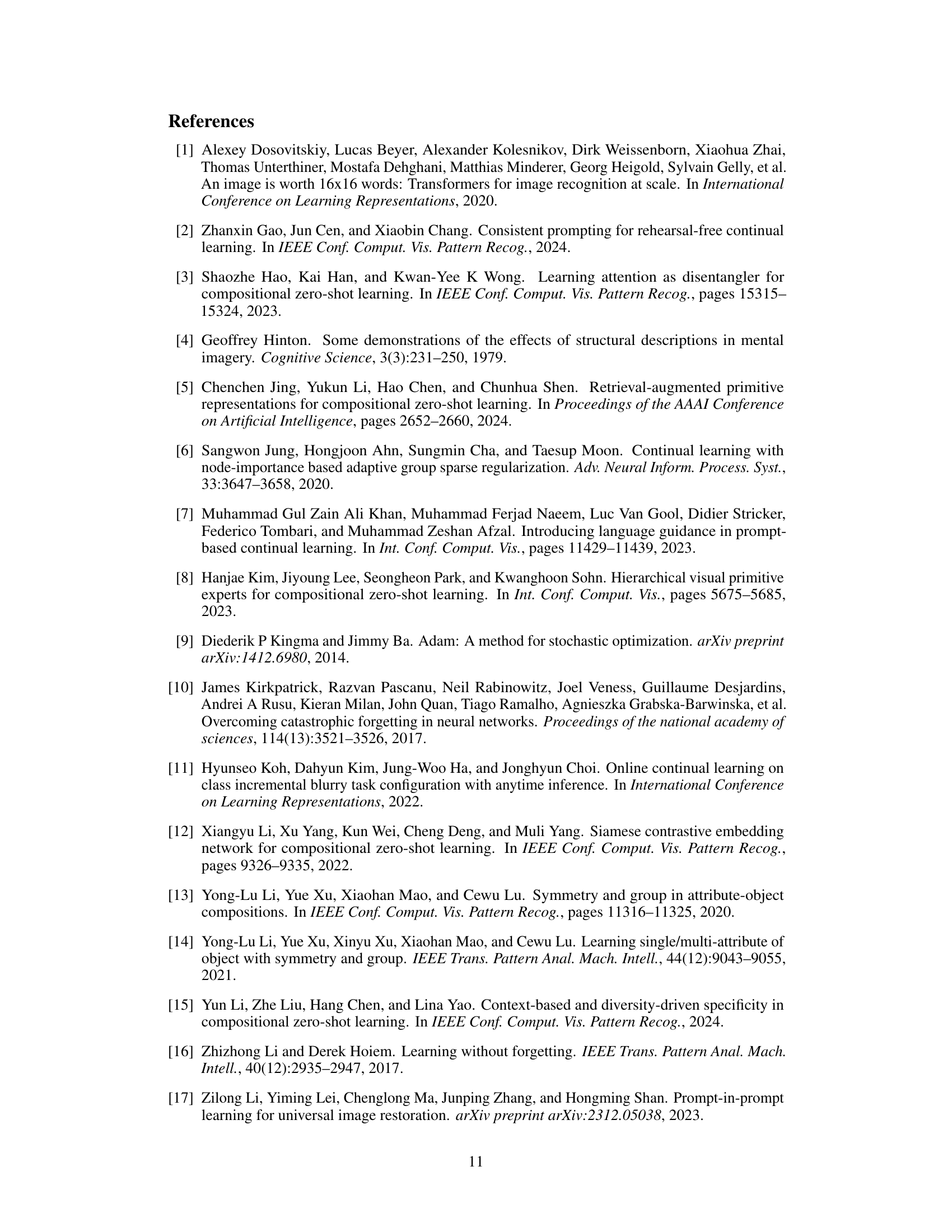

This table presents the ablation study of the multi-pool prompt learning. It shows the performance results (Average Accuracy, Forgetting, and Harmonic Mean) on the Split-Clothing (5 tasks) dataset when different combinations of prompt pools (Composition, State, and Object) are used. The results demonstrate the contribution of each prompt pool and highlight the benefit of incorporating all three pools for optimal performance.

This table presents the ablation study on the impact of using different combinations of prompt pools (composition, state, and object) in the CompILer model on the Split-Clothing dataset. It shows how the model’s performance (Avg Acc, FTT, State accuracy, Object accuracy, and Harmonic Mean) changes as different prompt pools are added or removed. The results highlight the contribution of each prompt pool to the overall performance and demonstrate the synergistic effect of using all three pools together.

This table presents the ablation study results on two aspects of the proposed CompILer model: object-injected state prompting and the prompt fusion method. It compares the performance (Avg Acc, FTT, State, Object, HM) of different configurations, showing the impact of each component on the overall performance of the model. For object-injected state prompting, it examines three settings: no object-injected prompting, state-injected object prompting, and object-injected state prompting. For the prompt fusion method, it investigates three approaches: max pooling, mean pooling, and the proposed generalized-mean pooling.

This table shows the ablation study of different prompt fusion methods on the Split-Clothing dataset with 5 tasks. It compares the performance using max pooling, mean pooling, and generalized-mean (GeM) pooling across various metrics including Average Accuracy (Avg Acc), Forgetting (FTT), State accuracy, Object accuracy, and Harmonic Mean (HM). The results demonstrate the superiority of the GeM pooling method, which yields the best performance overall.

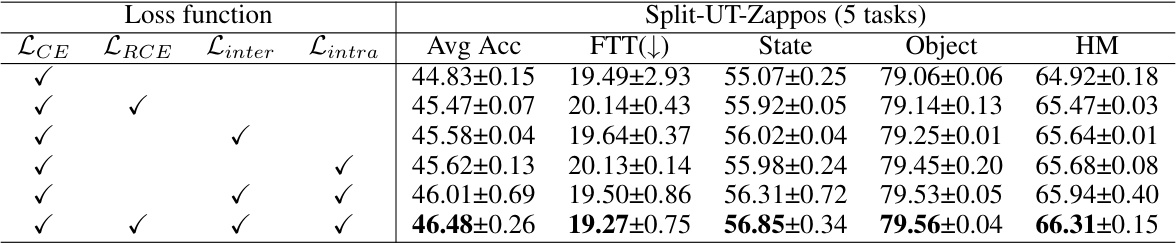

This table presents the ablation study on the impact of different loss functions on the performance of the CompILer model. It shows the Average Accuracy (Avg Acc), Forgetting rate (FTT), State accuracy, Object accuracy, and Harmonic Mean (HM) for different combinations of loss functions (Cross Entropy (LCE), Reverse Cross Entropy (LRCE), Inter-pool Discrepancy Loss (Linter), Intra-pool Diversity Loss (Lintra)) on two datasets: Split-Clothing and Split-UT-Zappos. The results demonstrate the contribution of each loss function in improving the model’s performance.

This table presents the average accuracy (Avg Acc) and forgetting rate (FTT) for different incremental learning methods on two datasets: Split-Clothing (with 5 tasks) and Split-UT-Zappos (with 5 and 10 tasks). The ‘Upper Bound’ row represents the best achievable performance if catastrophic forgetting were not an issue. The table shows that the proposed CompILer method outperforms existing methods in terms of both accuracy and forgetting.

Full paper#