↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Hierarchical clustering is a widely used technique in data analysis. Existing theoretical analyses focus on cost functions which are not easily interpretable in metric spaces and do not distinguish average-link from random hierarchies. This paper uses new criteria which are more interpretable and directly quantify cohesion and separability. These are useful metrics for evaluating clustering performance, especially in scenarios requiring both compact clusters and clear separation between them.

This paper presents a comprehensive study of average-link in metric spaces using the new criteria. The authors provide theoretical analyses showing average-link performs better than other popular methods. Their results also reveal that average-link has a logarithmic approximation to the new criteria, unlike single-linkage and complete-linkage. Finally, experiments on real datasets validate the theoretical findings and support the choice of average-link.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in clustering and machine learning as it provides a deeper understanding of average-link’s performance, offering new theoretical guarantees and practical insights. It challenges the existing theoretical frameworks by introducing interpretable criteria for evaluating cohesion and separability, paving the way for improved algorithms and better interpretations of clustering results. The experimental results validate the theoretical findings, adding to the paper’s significance and opening doors for future research into improving hierarchical clustering algorithms and selecting appropriate criteria for various applications.

Visual Insights#

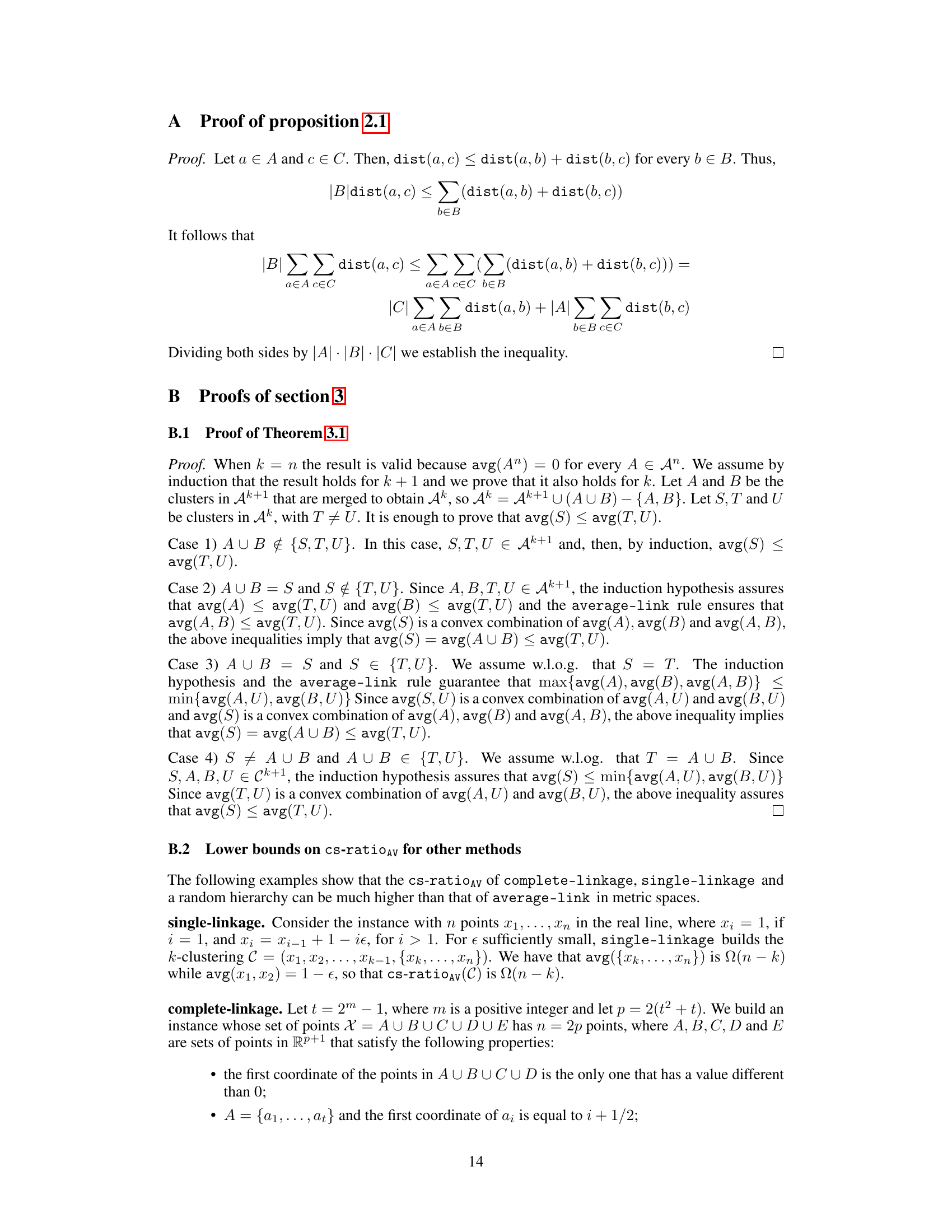

This figure compares the maximum diameter criterion for three different hierarchical clustering methods (single, complete, average) across ten different datasets. The bar height for each dataset represents the average ratio of the maximum diameter achieved by each method to the best maximum diameter achieved among the three methods for that dataset. Lower values indicate better performance according to this metric.

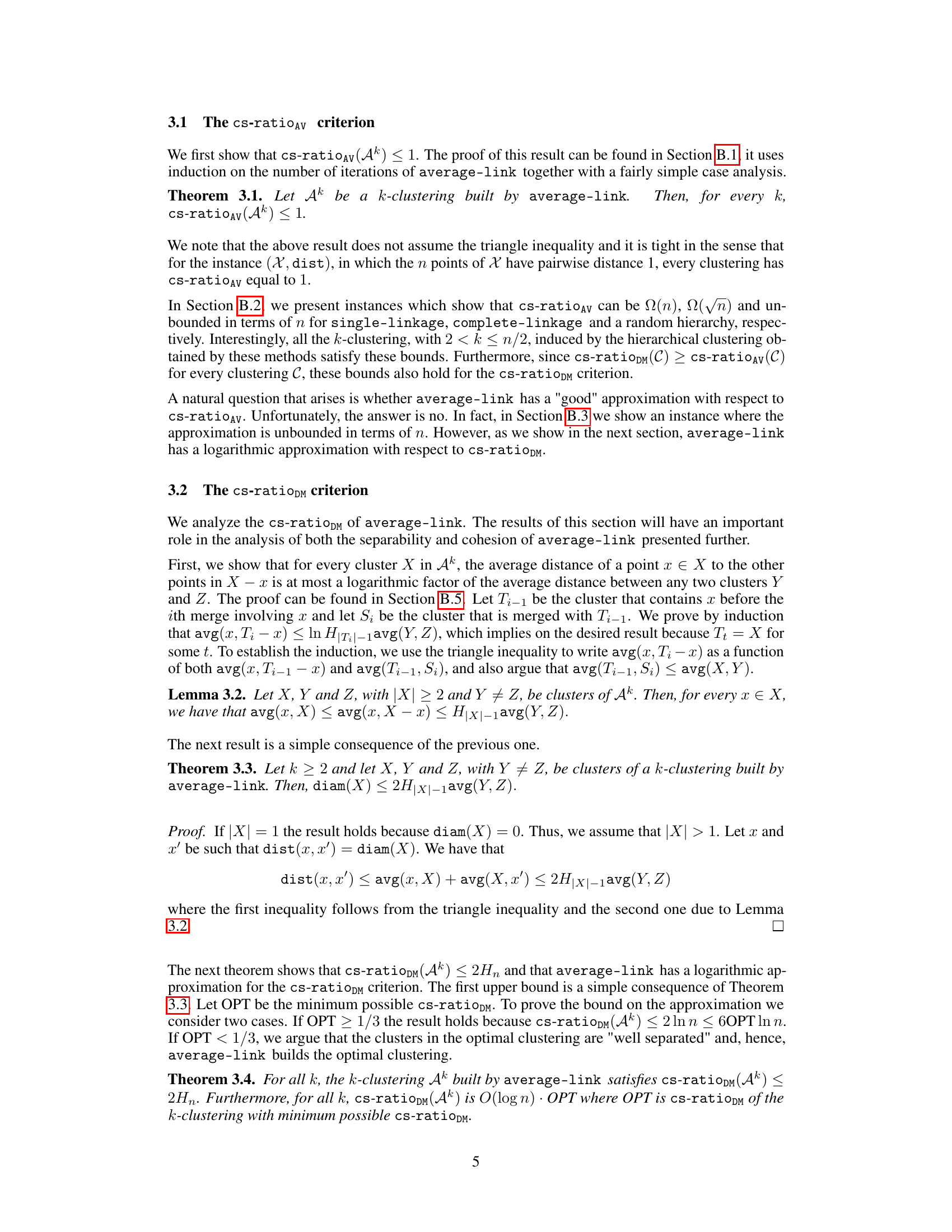

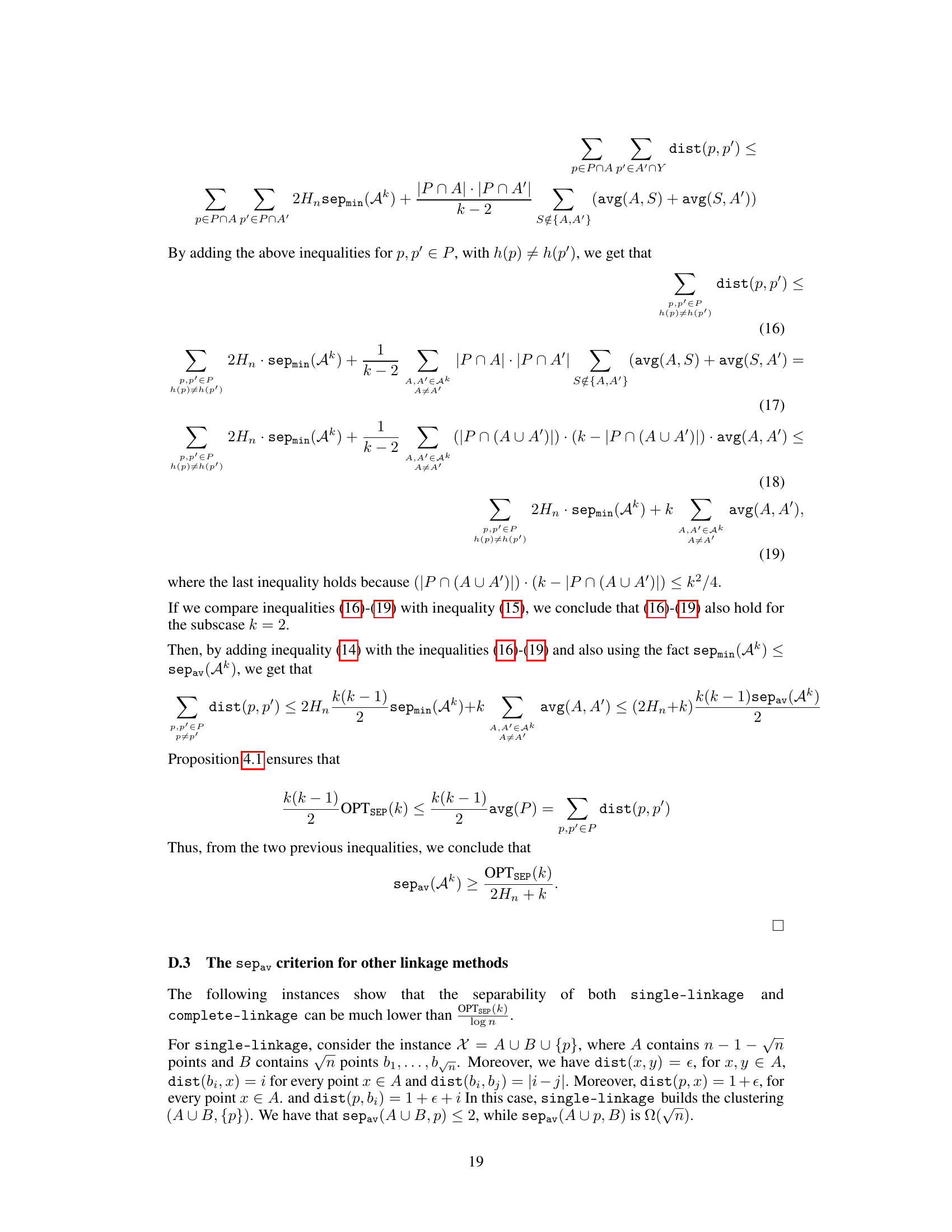

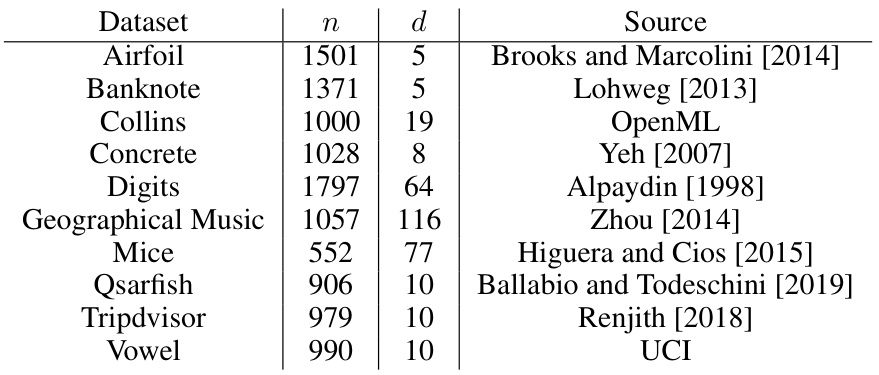

This table presents the average ratio between the result obtained by a given method (average-link, complete-linkage, single-linkage) and the best result obtained for each criterion (sepmin, sepav, max-diam, max-avg, cs-ratioDM, cs-ratioAV) across different dataset groups (small, medium, large k-values). A higher ratio indicates better performance relative to the best method for that specific criterion and k-group. Bold values denote the best-performing methods.

In-depth insights#

Avg-Link Cohesion#

The analysis of average-link cohesion in hierarchical clustering focuses on how well the algorithm groups similar data points together within clusters. Average-link’s strength lies in its balance between cohesion and separation. While it doesn’t guarantee optimal cohesion in all cases, its iterative merging strategy based on average pairwise distances between clusters helps to form relatively compact and well-separated groups. The theoretical work often examines approximation bounds using metrics like Dasgupta’s cost function, but these don’t fully capture the intuitive notion of cluster compactness. Research often highlights average-link’s better performance compared to single or complete-linkage, suggesting it’s a practically effective method for balancing cohesion and separation goals in hierarchical clustering.

Separability Analysis#

A comprehensive separability analysis within a clustering context would delve into how effectively the algorithm distinguishes between different clusters. It would examine the distances between clusters (inter-cluster distances) and within clusters (intra-cluster distances), ideally aiming for large inter-cluster and small intra-cluster distances. Metrics such as average inter-cluster distance, minimum inter-cluster distance, and cluster diameter could be employed for quantitative assessment. The analysis might also consider the impact of various parameters and data characteristics on separability, such as the choice of distance metric, the dimensionality of the data, or the presence of noise. Visualizations, like dendrograms or scatter plots, would offer insights into the structure of the clusters and how well-separated they are. A robust separability analysis goes beyond simple metrics; it should explore how the algorithm’s separability performance changes with the number of clusters (k) and provide explanations for any observed trends. Furthermore, a comparison with other clustering methods provides important context, highlighting relative strengths and weaknesses in cluster separation.

Empirical Validation#

An empirical validation section in a research paper serves to demonstrate the practical relevance and effectiveness of the proposed methods or models. It typically involves applying the research findings to real-world datasets or scenarios and comparing the results to existing approaches or benchmarks. A strong empirical validation shows robustness across various datasets, highlighting advantages in accuracy, efficiency, or other relevant metrics. Conversely, a weak empirical validation may reveal limitations of the approach, such as susceptibility to specific data characteristics or underperformance compared to competing methods. The results should be presented clearly, ideally with visualizations and statistical analysis, to aid in the interpretation and assessment of the research. Furthermore, a good empirical validation will include a detailed discussion on the choices made for datasets, metrics, and comparison methods, ensuring the rigor and reliability of the findings. The quality of the empirical validation section significantly impacts the credibility and overall impact of the research paper.

Approximation Bounds#

Approximation bounds in the context of hierarchical clustering algorithms, such as average-link, are crucial for understanding their performance guarantees. These bounds quantify how close the output of an approximation algorithm, like average-link, comes to an optimal solution, often measured by a specific cost function (e.g., Dasgupta’s cost function). Tight approximation bounds demonstrate the algorithm’s efficiency and help compare it to other methods. However, the choice of cost function heavily influences the obtained bounds, and a cost function that is more interpretable or meaningful in the specific application domain is often preferred over one that merely yields tight bounds. Furthermore, approximation bounds often consider worst-case scenarios, potentially overlooking the algorithm’s typical performance on real-world datasets. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation involves both theoretical approximation bounds and experimental analysis to obtain a holistic picture of the algorithm’s performance.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore average-link’s behavior in non-metric spaces, investigating its robustness and approximation guarantees under different distance functions or similarity measures. A deeper analysis into the impact of data dimensionality and noise on average-link’s performance is warranted, potentially leading to improved algorithms for high-dimensional or noisy data. The development of more efficient algorithms for average-link, especially for large datasets, remains crucial and could involve exploring techniques such as distributed or parallel computing. Finally, comparative studies against other hierarchical clustering methods, using a broader range of evaluation metrics and real-world datasets, would enhance our understanding of average-link’s strengths and limitations in specific applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

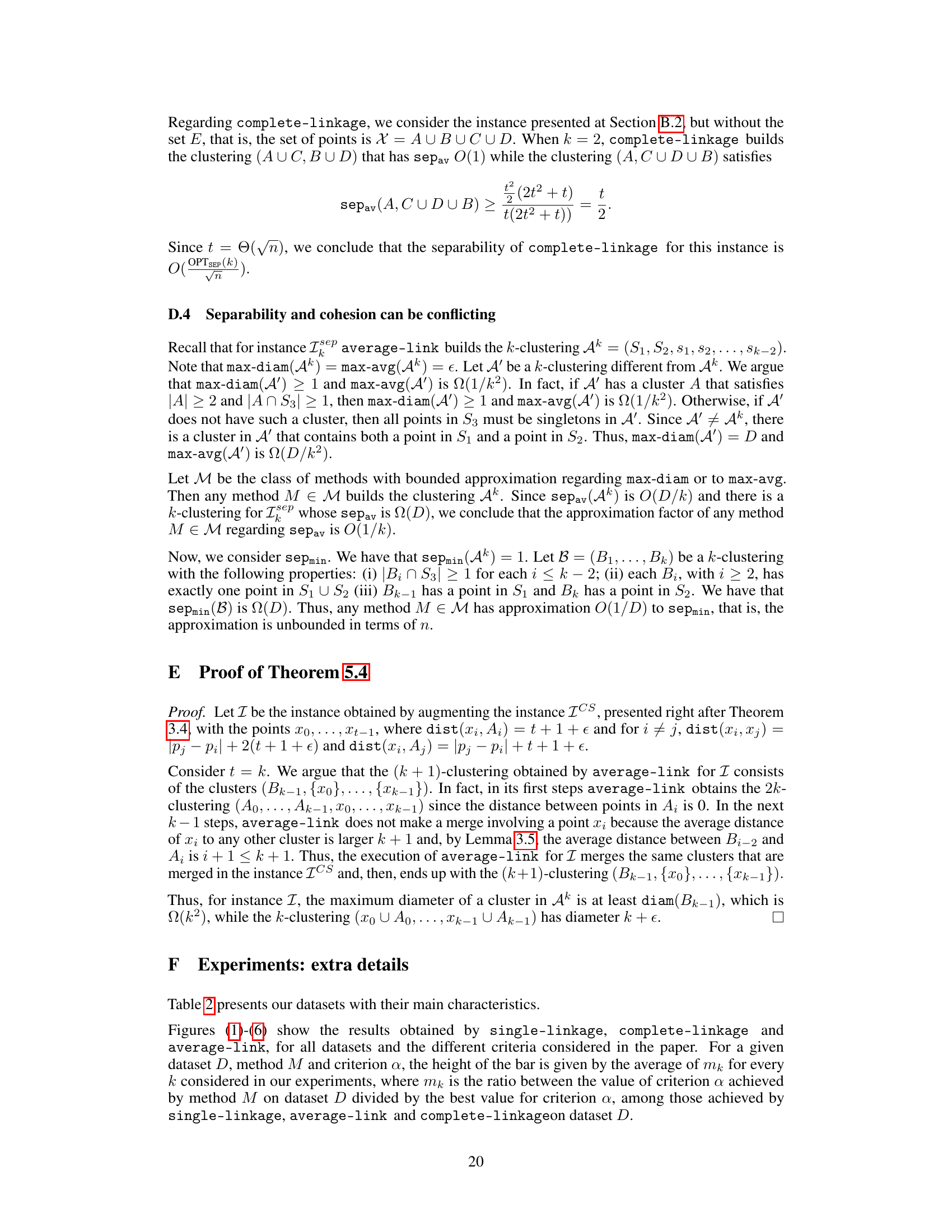

This figure compares the performance of three hierarchical clustering methods (single, complete, and average linkage) across ten different datasets using the maximum average pairwise distance (max-avg) as a metric. The height of each bar represents the average ratio of the max-avg achieved by each method to the best max-avg among the three methods for a given dataset and k-value. A lower value indicates better performance.

This figure presents the results of the max-diam criterion for different datasets. The max-diam criterion measures the cohesion of a clustering by considering the maximum diameter of the clusters. The lower the bar, the better the clustering performance according to this criterion. The figure compares the results obtained by three different hierarchical clustering methods: single-linkage, complete-linkage, and average-linkage. Each bar represents a different dataset.

This figure presents a bar chart comparing the performance of three hierarchical clustering methods (single, complete, and average-linkage) across ten different datasets. The performance metric is sepav (average separability), where higher values are better, indicating greater separation between clusters. Each dataset is represented by a group of three bars, one for each method, showing their sepav values. The chart helps to visually assess the relative effectiveness of each clustering method in achieving good cluster separation across a variety of data.

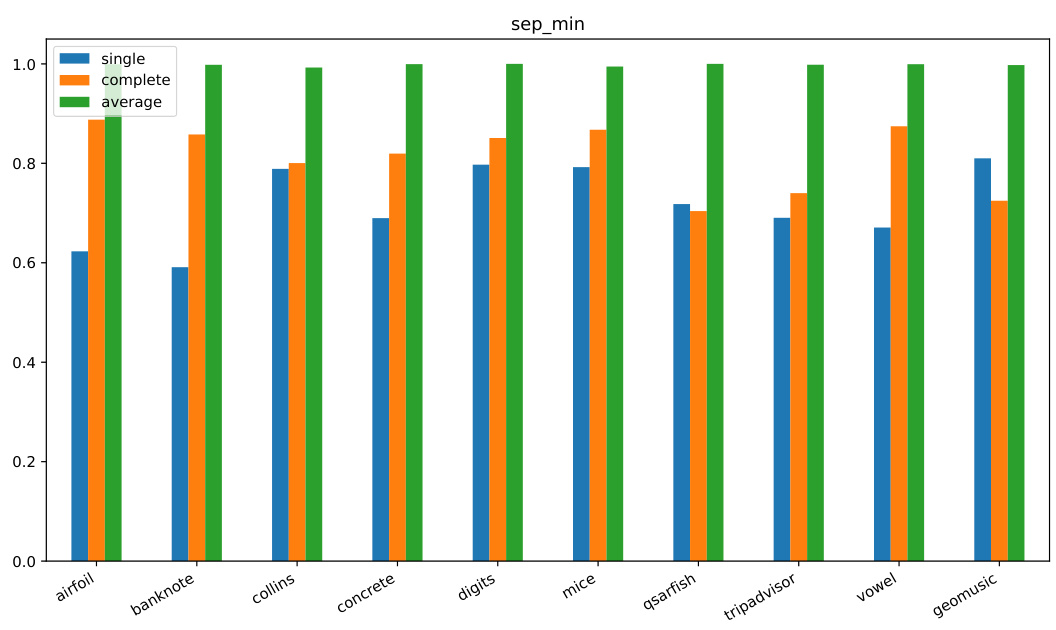

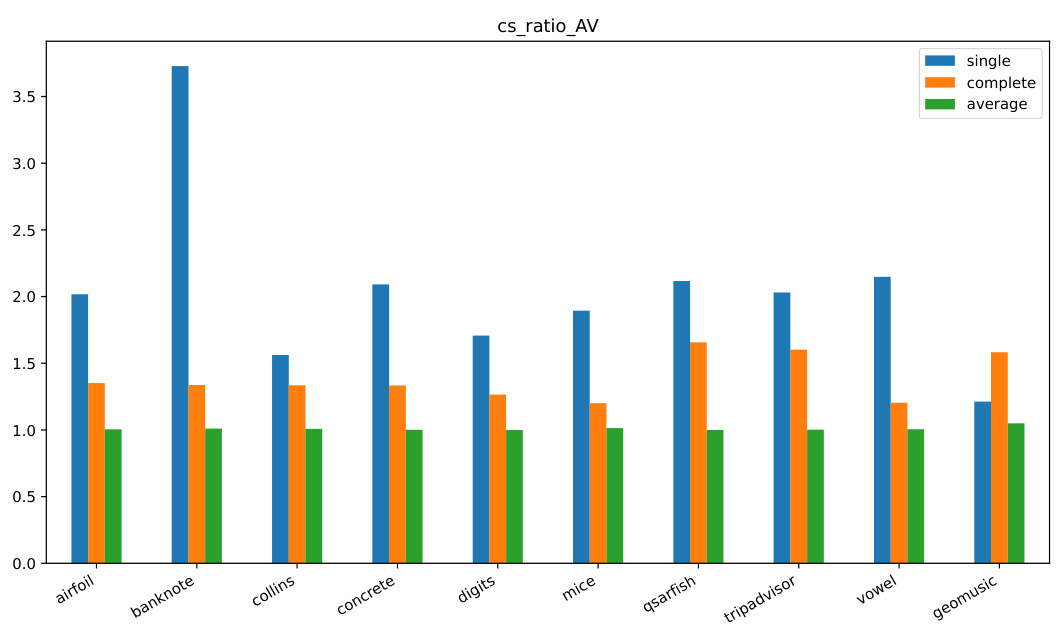

This figure compares the performance of three hierarchical clustering methods (single, complete, and average linkage) across ten different datasets using the cs-ratioAV criterion. Lower values indicate better performance. The bar chart shows that average linkage generally outperforms single and complete linkage in minimizing the cs-ratioAV metric across the tested datasets.

This figure displays the results of the cs-ratioDM criterion for different clustering methods (single, complete, and average linkage) across ten datasets. The cs-ratioDM combines cohesion and separability criteria, and lower values indicate better performance. The bar chart visualizes the average ratio of each method’s cs-ratioDM result to the best-performing method’s result for each dataset, providing a comparative analysis of the methods’ performance with respect to this combined criterion.

More on tables

This table presents the average ratio between the results obtained by each clustering method (average-link, complete-linkage, and single-linkage) and the best result for each criterion (sepmin, sepav, max-diam, max-avg, cs-ratioDM, cs-ratioAV). The results are grouped by different ranges of k values (Small, Medium, Large) to show how performance varies with the number of clusters. The best result for each criterion and k-group is shown in bold.

This table presents the average ratio between the results obtained by each of three methods (average-link, complete-linkage, and single-linkage) and the best result for each criterion (sepmin, sepav, max-diam, max-avg, cs-ratioDM, cs-ratioAV). The results are grouped by the size of k (small, medium, large) to show the performance of each method across different cluster sizes.

This table presents the average ratio between the results obtained by three hierarchical clustering methods (average-link, complete-linkage, and single-linkage) and the best result for each criterion and group of k values. The criteria evaluated include measures of separability (sepmin, sepav), cohesion (max-diam, max-avg), and a combination of both (cs-ratioDM, cs-ratioAV). The best result for each criterion and k is highlighted in bold. The table provides a summary of the experimental performance of the methods across different datasets and various numbers of clusters (k).

This table presents the average ratio between the results obtained by each clustering method (average-link, complete-linkage, and single-linkage) and the best-performing method for each criterion (sepmin, sepav, max-diam, max-avg, cs-ratioDM, cs-ratioAV). The ratios are calculated for different group sizes of k (small, medium, and large), providing a comparative analysis across various clustering quality metrics and k values.

Full paper#