↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

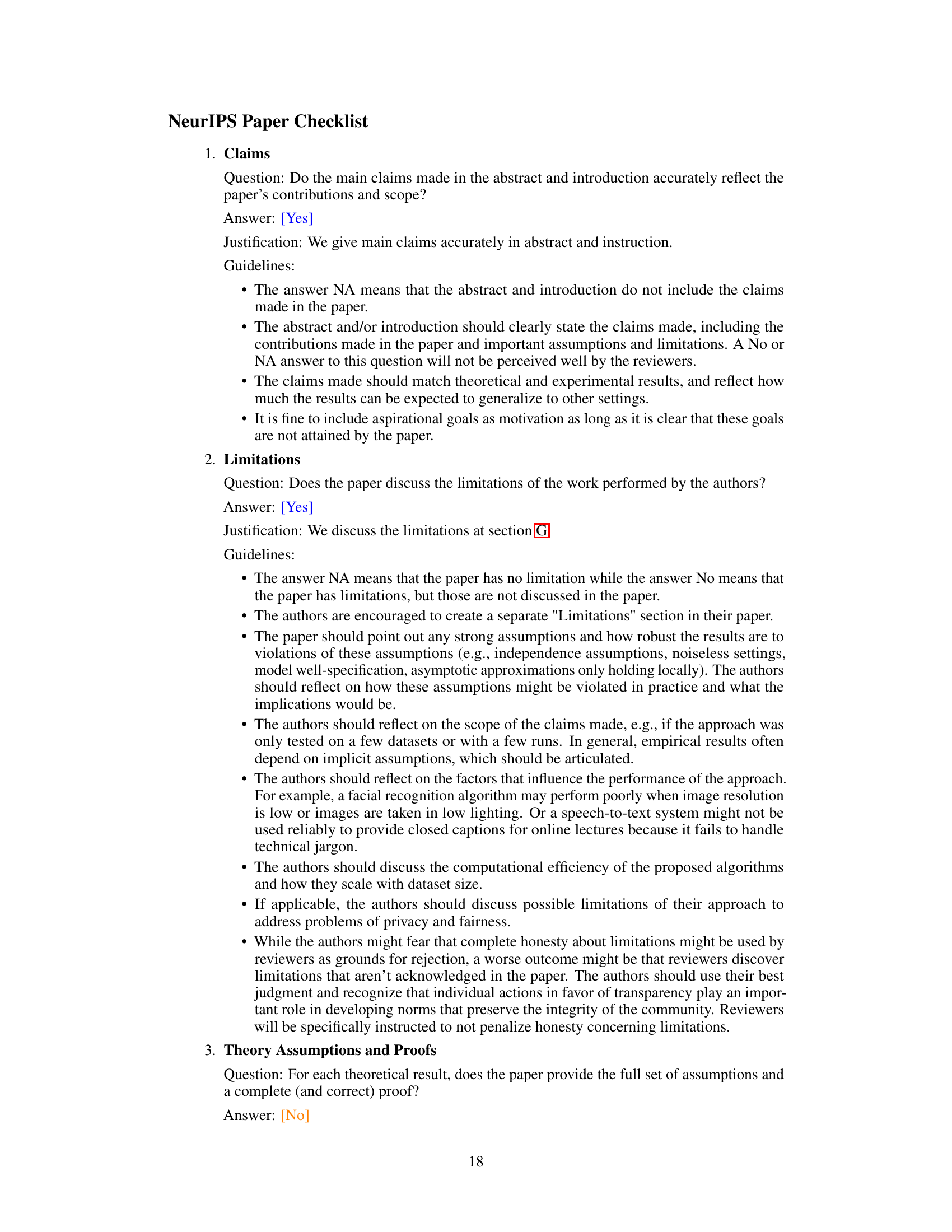

TL;DR#

Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) are powerful but computationally expensive, particularly when handling visual input. Existing methods for aggregating visual information, such as learnable queries, often lead to accuracy loss or high computation costs. The main challenge lies in finding an efficient way to condense the visual tokens without compromising accuracy.

This paper introduces AcFormer, a novel vision-language connector. AcFormer effectively identifies and utilizes “visual anchors” within the vision transformer to efficiently aggregate visual information. This approach drastically reduces the number of visual tokens used, resulting in a substantial reduction in computational cost, up to 66% less, with simultaneous improvements in accuracy compared to existing state-of-the-art methods.

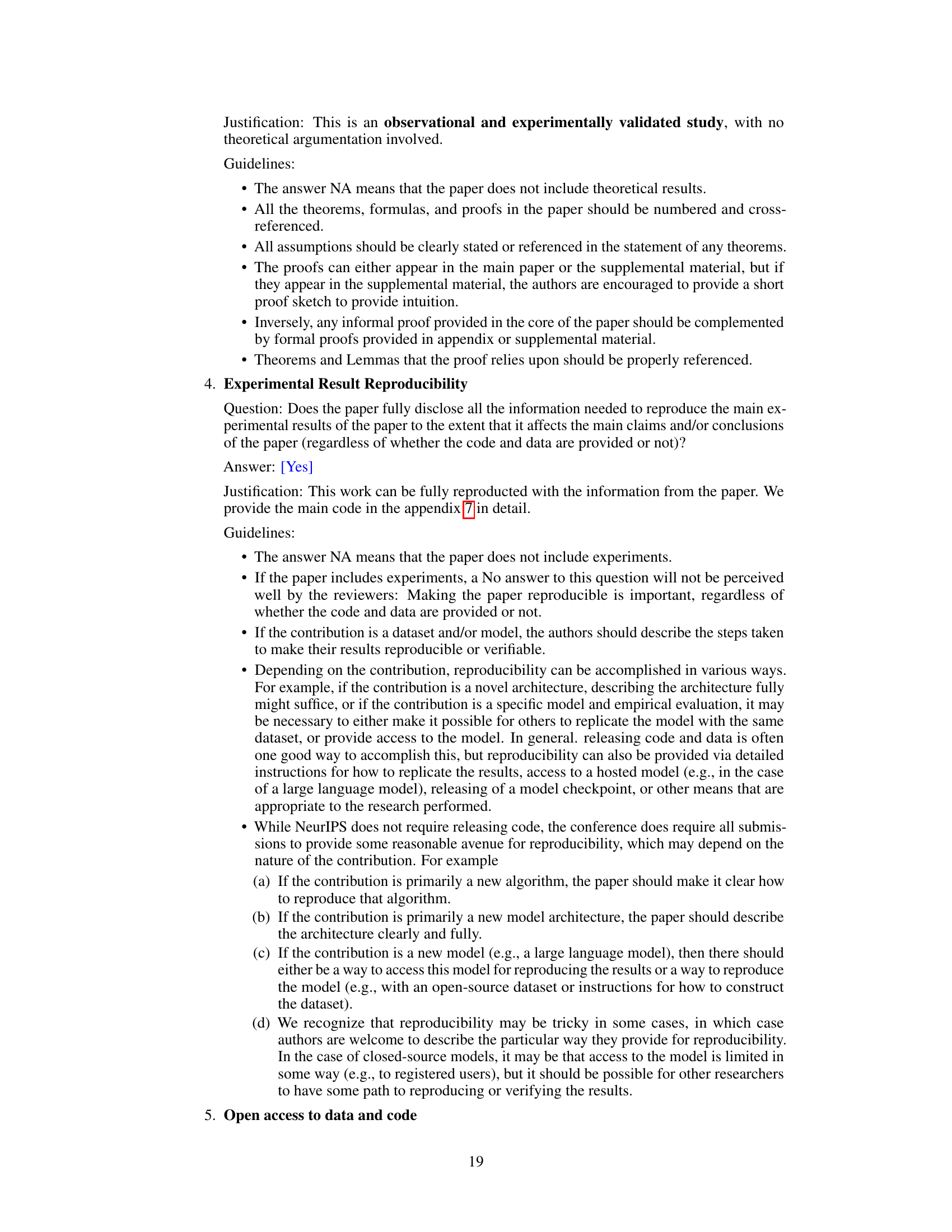

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical challenge in multimodal large language models (MLLMs): the computational cost of processing visual information. By identifying and leveraging “visual anchors” within vision transformers, AcFormer significantly reduces computation time by nearly two-thirds while improving accuracy. This work paves the way for more efficient and effective MLLMs, expanding their applicability to resource-constrained settings and broader applications.

Visual Insights#

This figure compares the average normalized accuracy of different vision-language connectors on three benchmark datasets (MMB, TextVQA, GQA) against the step time (seconds per step). The connectors compared include AcFormer (the proposed method), MLP, C-Abstractor, Pooling, and PR (Perceiver Resampler). The graph shows that AcFormer achieves the highest accuracy across all datasets, while maintaining a relatively fast training speed, outperforming the other methods in both accuracy and efficiency. The number of visual tokens used by each method is also indicated, showing that AcFormer uses significantly fewer tokens than some other methods while still maintaining high accuracy. The figure also visually represents the information aggregation mechanism using visual anchors in Vision Transformer, which is the core idea of the AcFormer method.

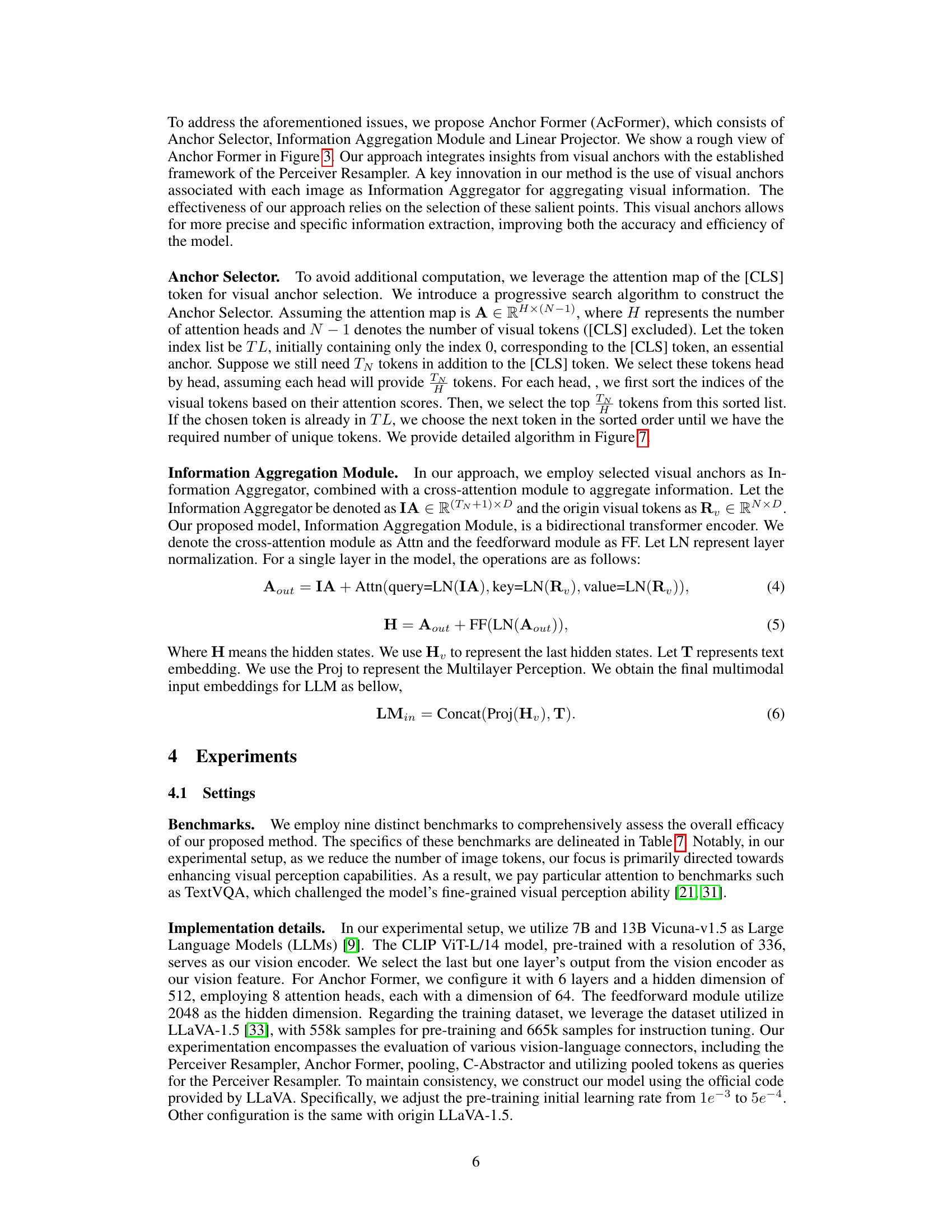

This table presents the results of various models on benchmarks designed for Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs). It compares the performance of the proposed AcFormer model against several existing models (MiniGPT-4, mPLUG-Owl2, InstructBLIP, LLaVA (v1), LLaMA-Adapter V2, Shikra, Qwen-VL, Qwen-VL-Chat, and LLaVA-1.5) across different LLM sizes (7B and 13B). Key metrics include accuracy on several benchmarks (Res, POPE, MME, MMB, MM-Vet) and the relative training speed compared to LLaVA-1.5. The number of visual tokens (V-T Num) used by each model is also shown, demonstrating the impact on computational cost. AcFormer achieves comparable or better accuracy with significantly reduced visual tokens, showcasing its efficiency.

In-depth insights#

Visual Anchor Discovery#

The concept of “Visual Anchor Discovery” in a multimodal large language model (MLLM) context suggests a method for identifying key visual features that are crucial for understanding an image. These anchors, likely discovered within the attention maps of a vision transformer, represent highly informative regions of the image. The discovery process itself is a significant contribution, moving beyond randomly initialized queries used in previous vision-language connectors. By identifying these anchors, the model can efficiently focus attention and aggregate relevant information, reducing computational cost while maintaining or even improving accuracy. This targeted approach contrasts with methods that process all visual tokens equally, making it more computationally efficient and potentially more robust to irrelevant or distracting visual information. The specific algorithm used to locate these visual anchors is likely iterative and data-driven, potentially leveraging the attention weights to identify regions that consistently attract the attention of the [CLS] token or other semantically meaningful tokens. The effectiveness of this technique hinges on the ability to reliably identify informative visual features, which could be affected by image quality, complexity, and the specific training data used. The overall impact is a more efficient and potentially more accurate MLLM.

AcFormer Architecture#

AcFormer’s architecture is characterized by its efficient and effective design for multimodal large language models (MLLMs). It leverages the concept of visual anchors, specific image regions identified within the vision transformer’s feature maps, to significantly reduce computational costs while improving accuracy. The core components include an Anchor Selector that uses a progressive search algorithm to identify these crucial visual anchors based on attention maps, bypassing the need for numerous visual tokens. This selection is followed by an Information Aggregation Module, likely employing cross-attention, to aggregate information from the identified anchors and generate a comprehensive visual representation. Finally, a Linear Projector transforms this representation into a format suitable for integration with the LLM, thus facilitating seamless multimodal processing. Efficiency is paramount; AcFormer achieves this by only processing a small subset of strategically selected visual tokens, making it computationally far less expensive than methods that use the entire image token set.

Efficiency Gains#

Analyzing efficiency gains in a research paper requires a multifaceted approach. First, quantify the improvements: what specific metrics were used to measure efficiency (e.g., speed, memory usage, energy consumption)? How significant are the reported improvements? Next, understand the methodology: what techniques were employed to achieve efficiency gains (e.g., algorithm optimization, model compression, hardware acceleration)? Were these techniques novel or adaptations of existing methods? A critical evaluation necessitates examining the trade-offs: did the efficiency gains compromise accuracy, generalizability, or other crucial aspects? Finally, consider the scope: do the efficiency gains hold across diverse datasets, model sizes, or task settings? The broader impact of the efficiency gains must also be considered: do the improvements enable wider accessibility of the technology or open new avenues of research? A complete analysis considers all these points to generate a nuanced perspective of claimed efficiency gains.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically removes components or features of a model to determine their individual contributions. In this context, it would likely involve removing parts of the proposed AcFormer architecture, such as the Anchor Selector or the Information Aggregation Module, to evaluate their impact on the overall model’s performance. By comparing the results of the full model to those of the models with components removed, researchers can quantify the effectiveness of each part. Key insights would be the relative importance of each AcFormer component and how much each contributes to the overall accuracy and efficiency gains. A well-designed ablation study should control for other factors, such as the number of visual tokens or the training dataset size, to isolate the impact of the removed components. The results would help justify the design choices made in AcFormer and highlight the importance of its unique architecture compared to alternatives such as the linear projection layer, Q-Former or Perceiver Resampler. Ultimately, a successful ablation study strengthens the paper’s claims by providing empirical evidence to support the design decisions and demonstrate the effectiveness of the AcFormer’s architecture.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the AcFormer to handle more complex multimodal tasks, such as those involving longer sequences or richer interaction modalities beyond image-text, would significantly broaden its applicability. Investigating the transferability of visual anchors across different vision encoders and datasets is crucial for establishing its robustness and generalizability. A deeper theoretical analysis of visual anchors, including their formation and properties, could potentially lead to more efficient and effective search algorithms. The impact of visual anchor selection on downstream tasks should also be investigated, possibly through systematic ablation studies and sensitivity analyses. Finally, exploring the integration of AcFormer with other multimodal techniques and exploring its suitability for real-time applications would further enhance its practical value. Ultimately, understanding how visual anchors contribute to visual semantic learning holds the key to unlocking new advancements in multimodal large language models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

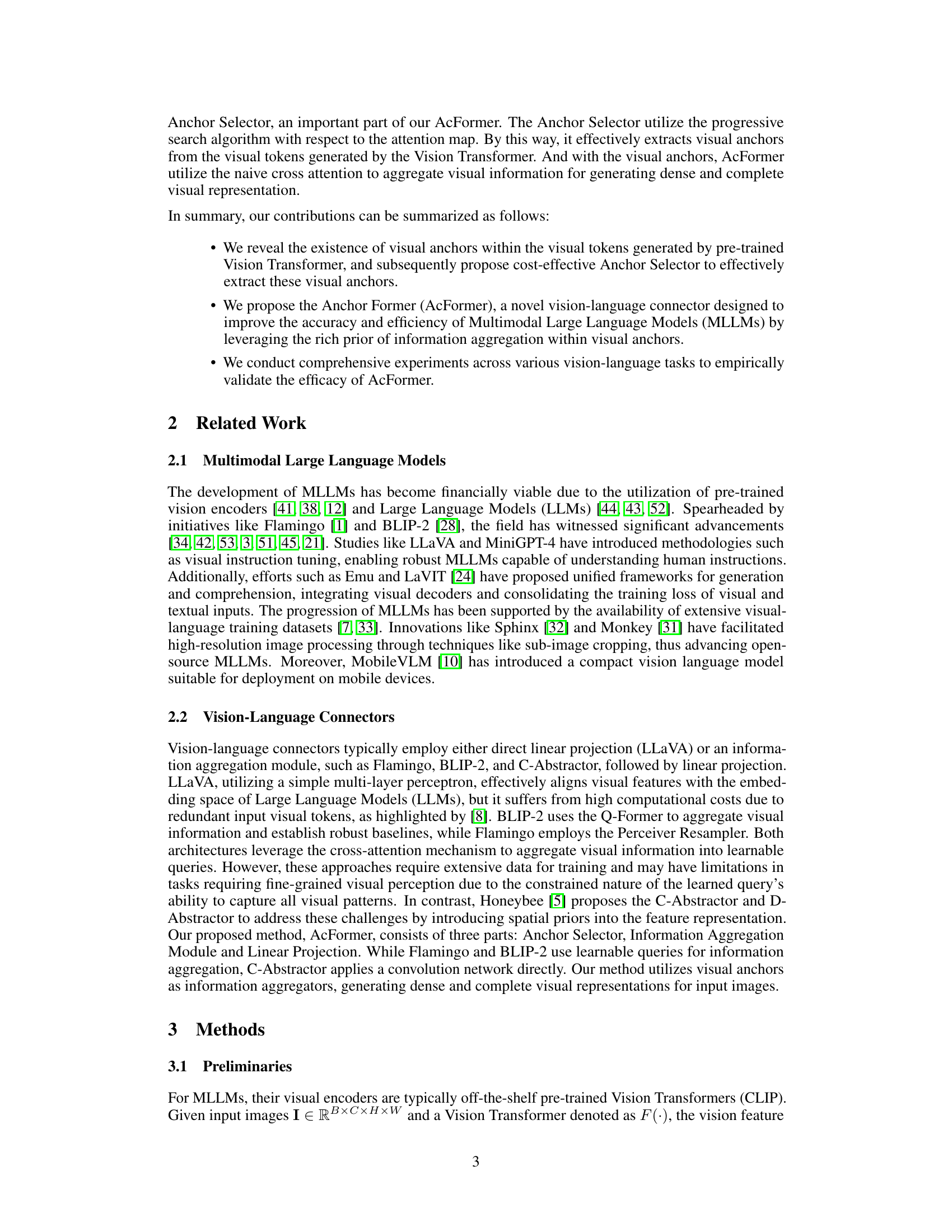

This figure visualizes the feature maps and attention maps from 10 different layers of a Vision Transformer model, focusing on the [CLS] token which represents the global image information. The visualizations highlight specific tokens (marked with red circles) that consistently show strong activation in both the feature maps and attention maps across multiple layers. These tokens are identified as ‘visual anchors’, demonstrating regions of the image that are particularly important for understanding the scene. The figure supports the paper’s claim that these visual anchors provide crucial information aggregation.

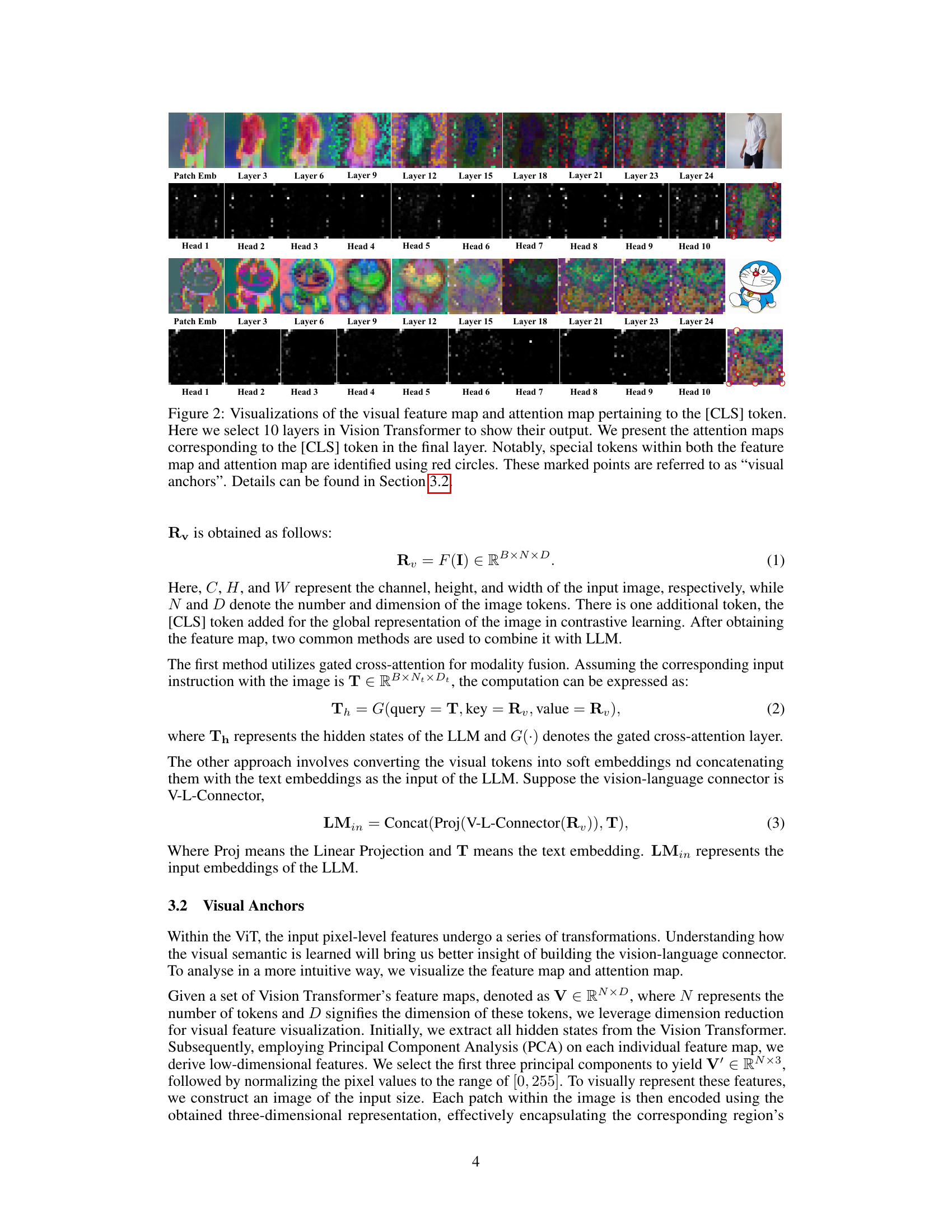

This figure illustrates the architecture of the proposed Anchor Former (AcFormer) method. AcFormer is a novel vision-language connector that leverages visual anchors to improve the efficiency and accuracy of Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs). The figure shows the process, starting with the vision feature extraction, then visual anchor selection by Anchor Selector, followed by Information Aggregation Module using cross-attention with selected anchors, and finally passing the aggregated information to the Large Language Model. It also compares AcFormer with other existing vision-language connectors, highlighting the advantages of using visual anchors and showing differences in flexibility and utilization of prior knowledge.

This figure visualizes the feature maps and attention maps from 10 different layers of a Vision Transformer. The visualization focuses on the [CLS] token, which is a special token used to represent the global context of the image. Red circles highlight special tokens called ‘visual anchors’, which the authors identify as important for information aggregation. The figure supports the authors’ claim that visual anchors exist and can be identified, providing evidence for their AcFormer method.

This figure visualizes feature maps and attention maps from different layers of a Vision Transformer for two example images. The visualizations highlight specific tokens (marked with red circles) that consistently appear activated across multiple layers both in feature maps and attention maps. These tokens, termed ‘visual anchors’, are central to the aggregation of visual information within the transformer, and are the foundation of the paper’s proposed AcFormer method.

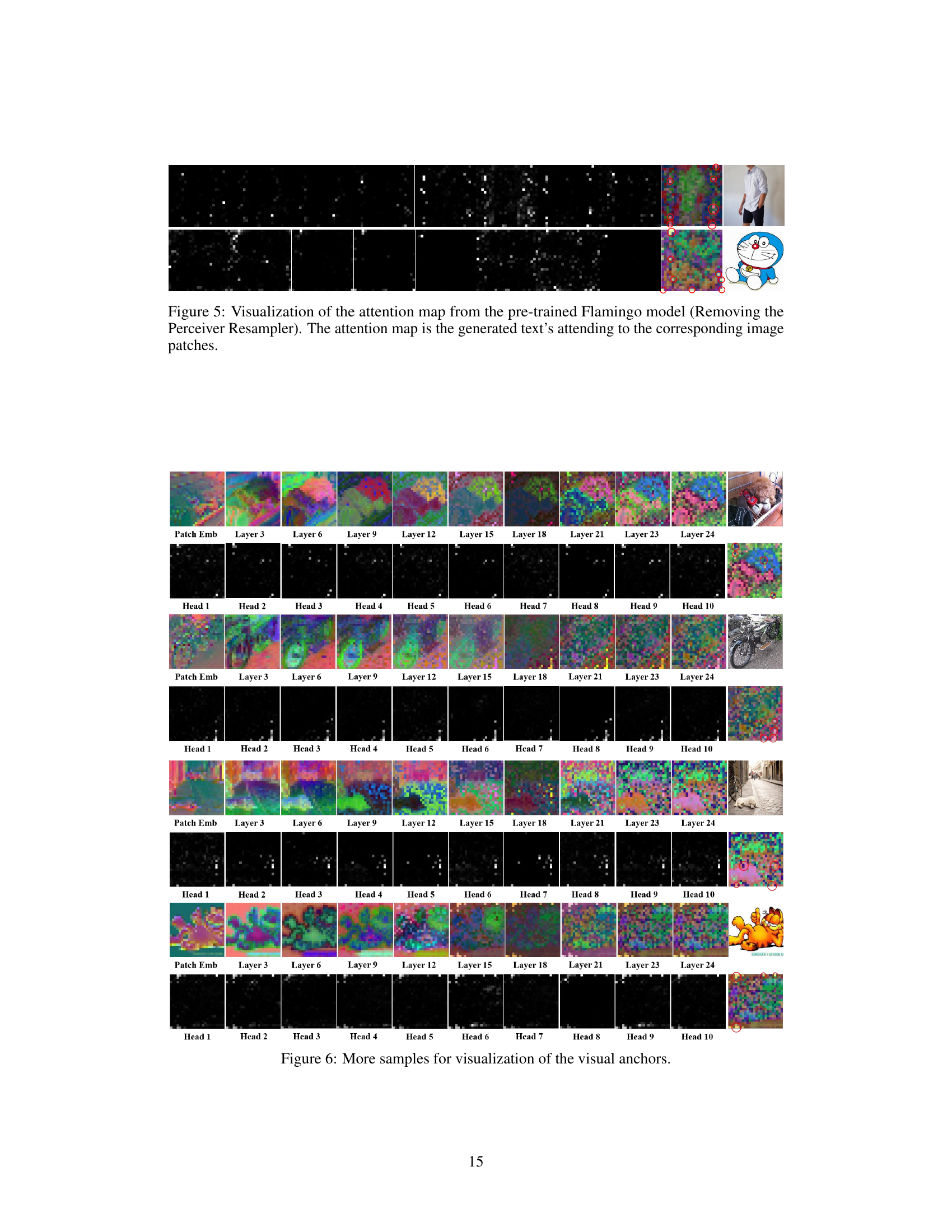

This figure shows more examples of visualizations of feature maps and attention maps from different layers of a vision transformer, supporting the paper’s claim of the existence and importance of ‘visual anchors’ in these models. The consistent pattern of activation across different images further validates the hypothesis that these anchors play a significant role in information aggregation.

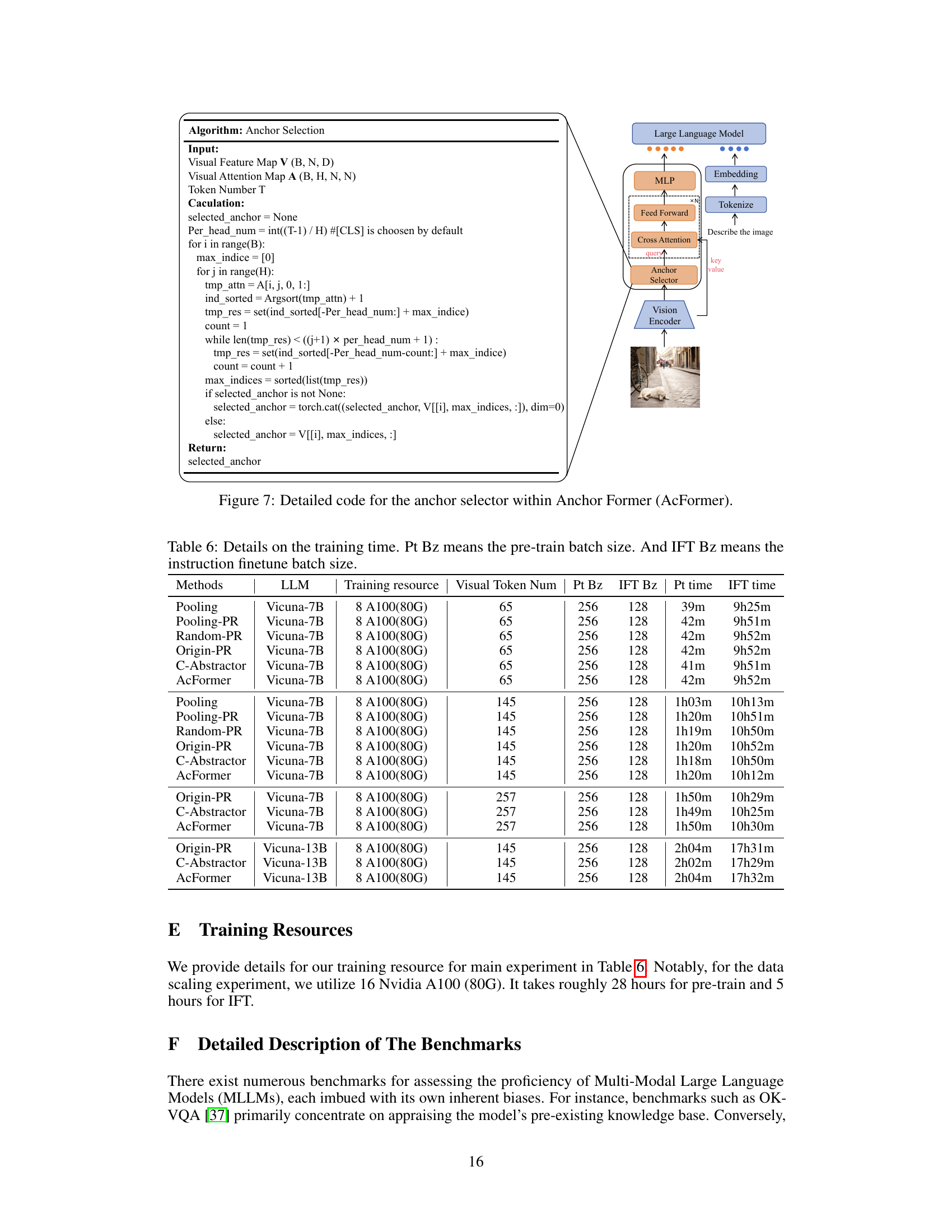

This figure shows the detailed Python code for the anchor selection algorithm used in the Anchor Former. The code iterates through the attention map to find the most salient visual tokens (anchors) and selects them as information aggregators for the vision-language connector. The input includes the visual feature map, attention map and the desired number of tokens. The algorithm uses a progressive search strategy to ensure diverse anchor selection and to avoid redundancy.

More on tables

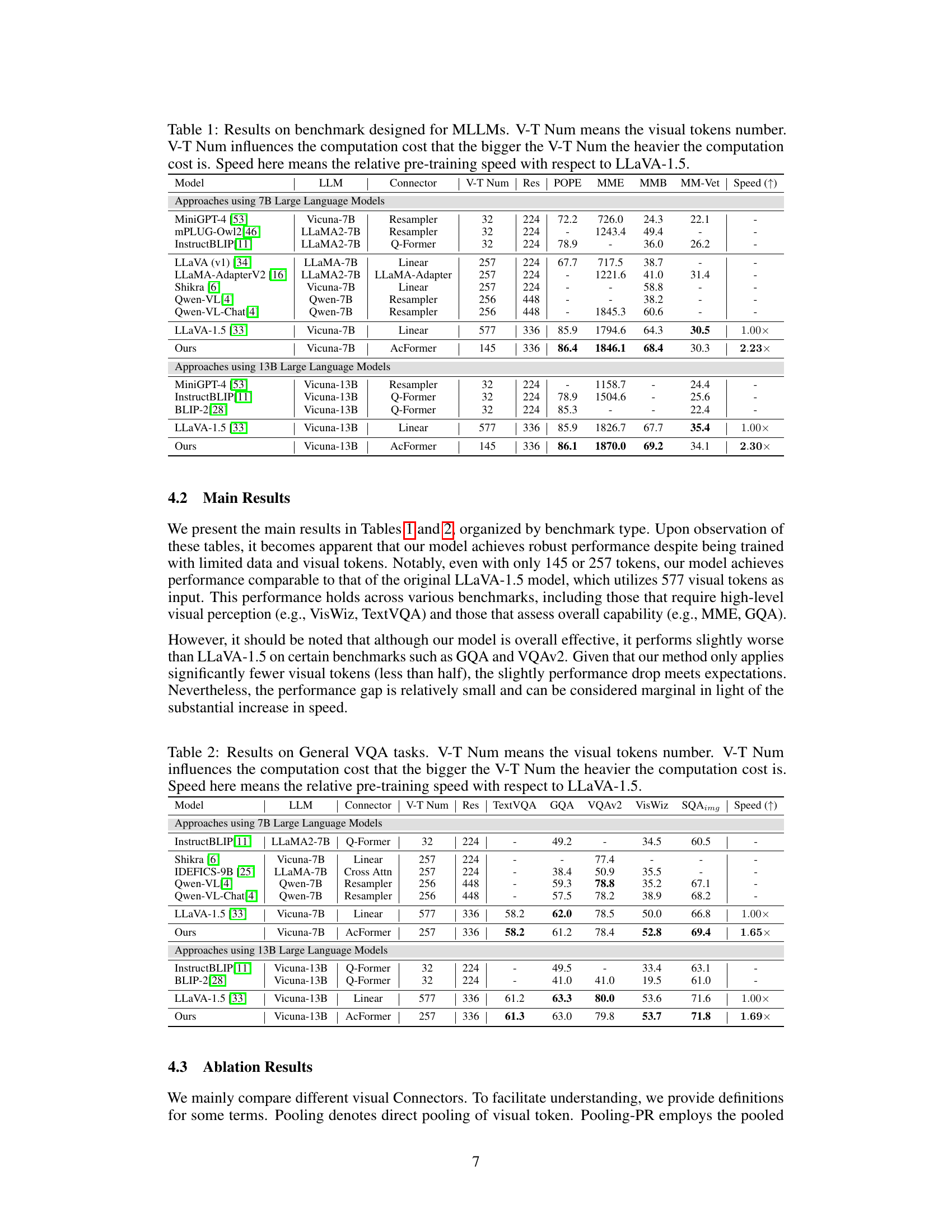

This table presents the results of the proposed AcFormer model and several baseline models on general visual question answering (VQA) benchmarks. It compares the average normalized accuracy and training speed for different models across several VQA datasets (TextVQA, GQA, VQAv2, VisWiz, SQAimg). The number of visual tokens (V-T Num) used by each model is also shown, highlighting the impact of reducing the number of visual tokens on computational cost. The ‘Speed (↑)’ column indicates the relative training speed compared to the LLaVA-1.5 baseline, demonstrating the efficiency gains achieved by AcFormer.

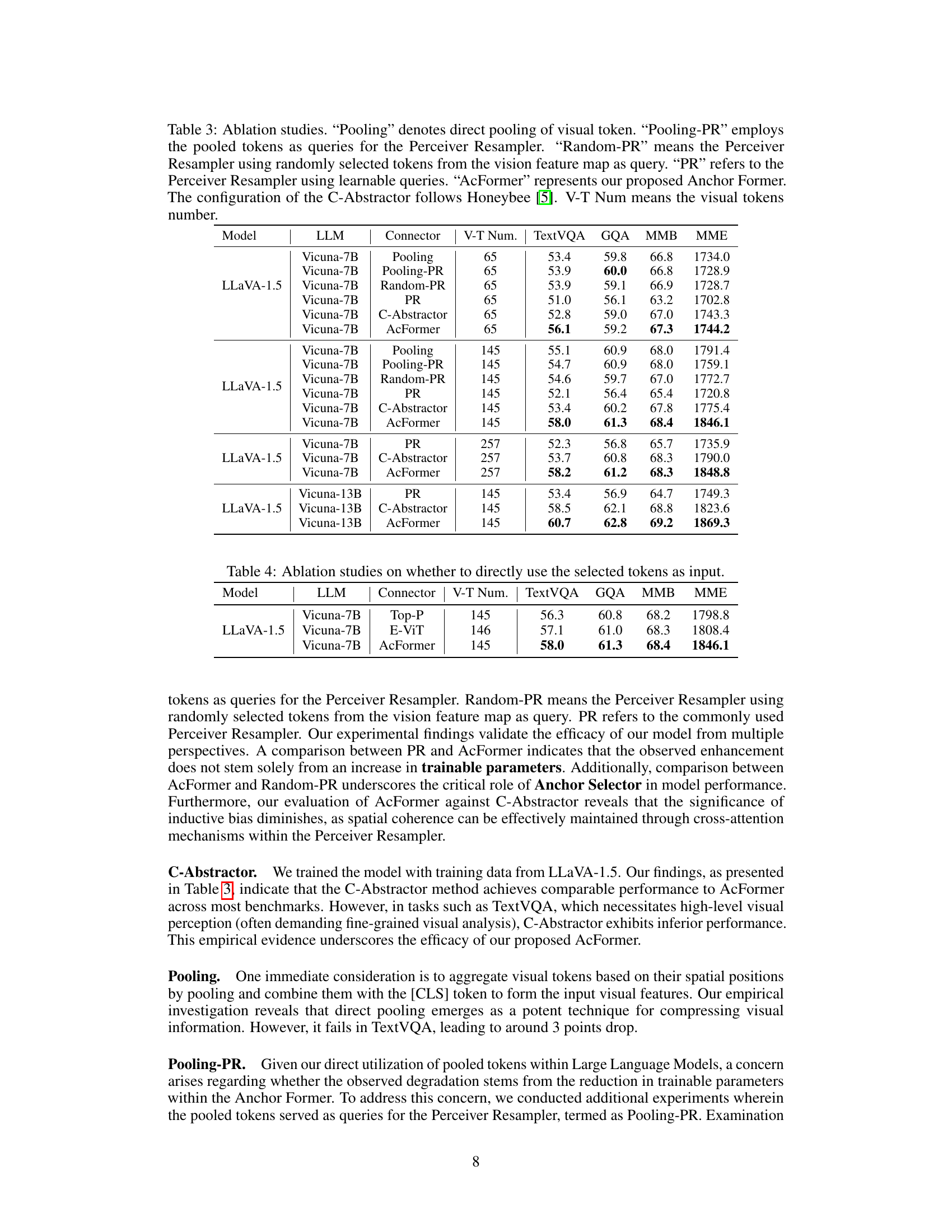

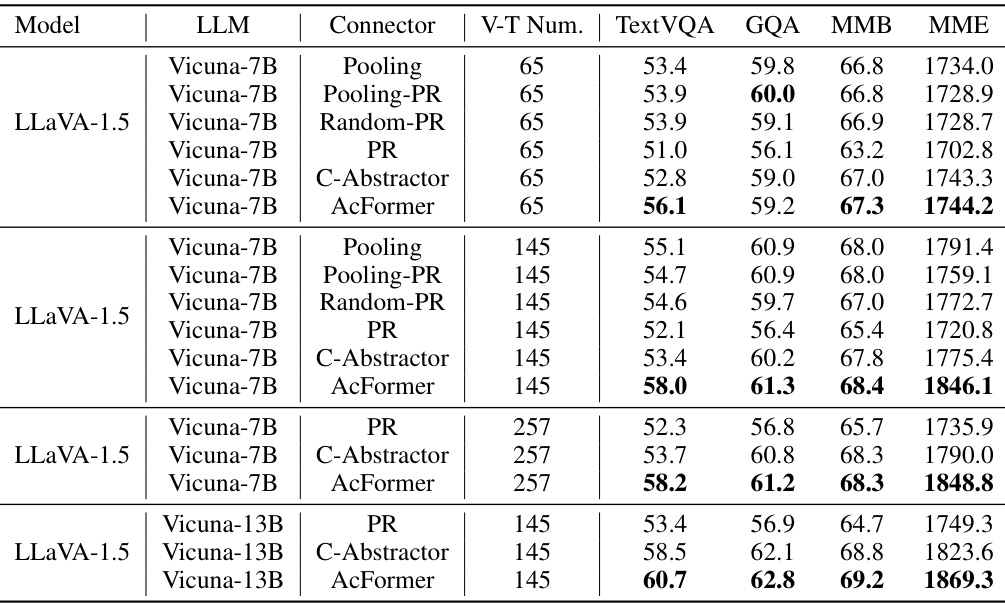

This table presents the ablation study results comparing different visual connectors: Pooling, Pooling-PR, Random-PR, PR, C-Abstractor, and AcFormer. It shows the performance of each connector on various benchmarks (TextVQA, GQA, MMB, MME) using different numbers of visual tokens (V-T Num). The results illustrate the impact of different information aggregation strategies on the overall model performance and the effectiveness of the proposed AcFormer.

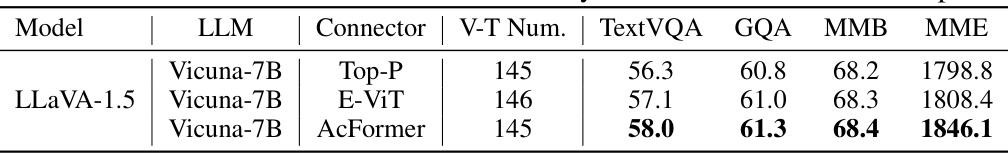

This table presents ablation study results, comparing different methods for utilizing selected visual tokens in the Perceiver Resampler. It shows a comparison of the performance of using the selected tokens directly, using top-p selection, E-ViT, and the proposed AcFormer method, across various metrics (TextVQA, GQA, MMB, MME). The purpose is to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed anchor selection and aggregation method in the AcFormer model.

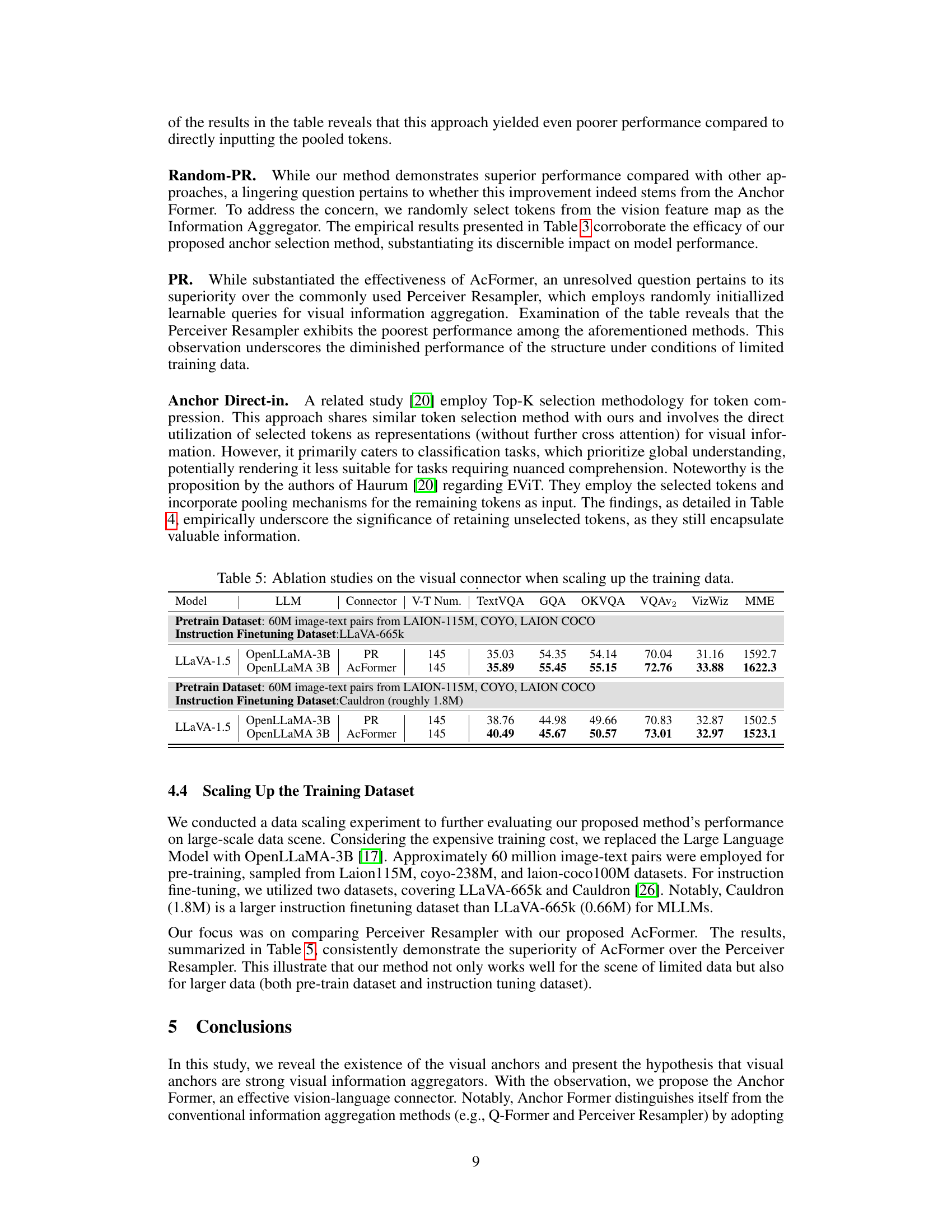

This table presents ablation studies comparing different visual connectors (PR, AcFormer, Top-P, E-ViT) under two different training data scales using OpenLLaMA-3B. It evaluates their performance on TextVQA, GQA, OKVQA, VQAv2, VizWiz, and MME benchmarks. The dataset sizes used for pretraining and instruction finetuning are specified, highlighting the impact of larger datasets on model performance and demonstrating the effectiveness of the AcFormer.

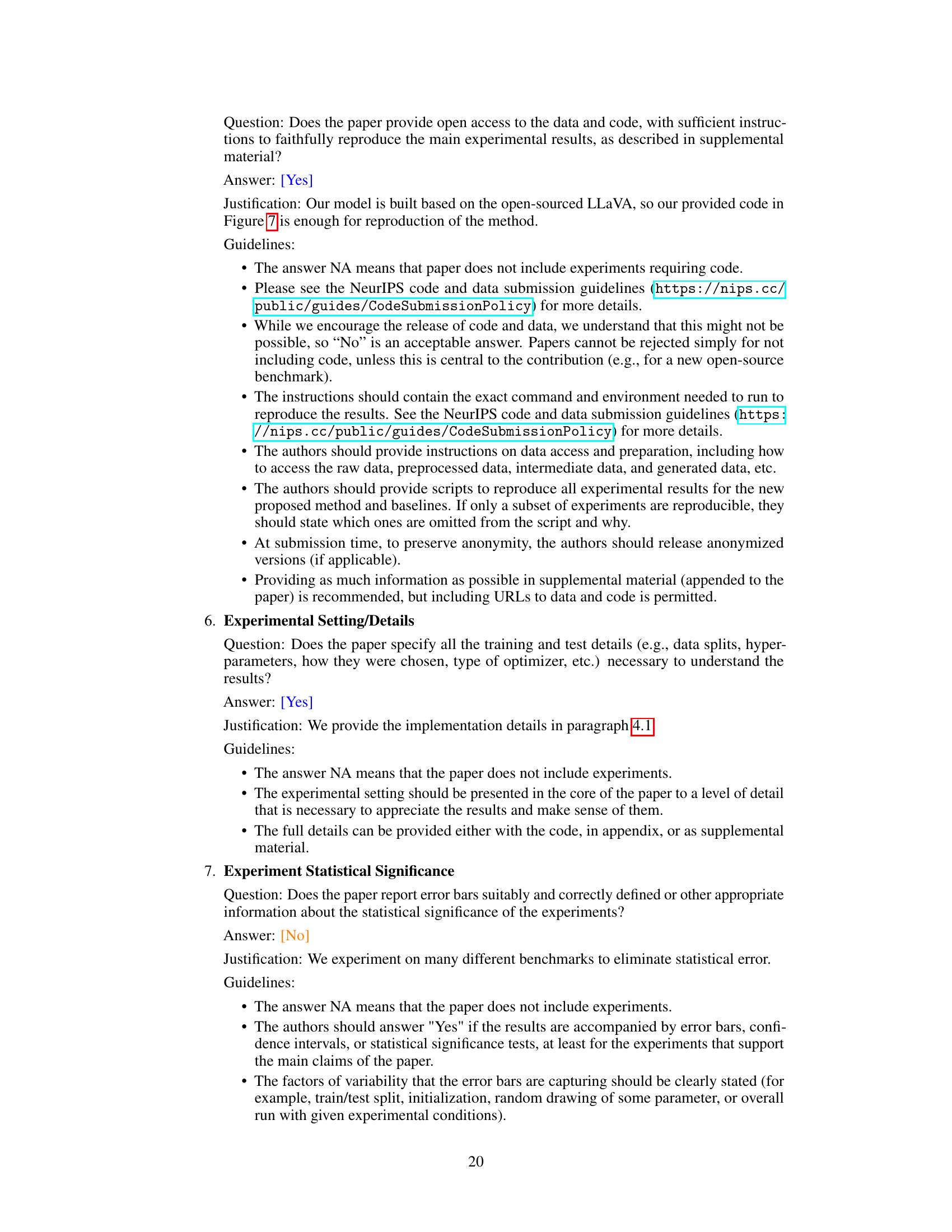

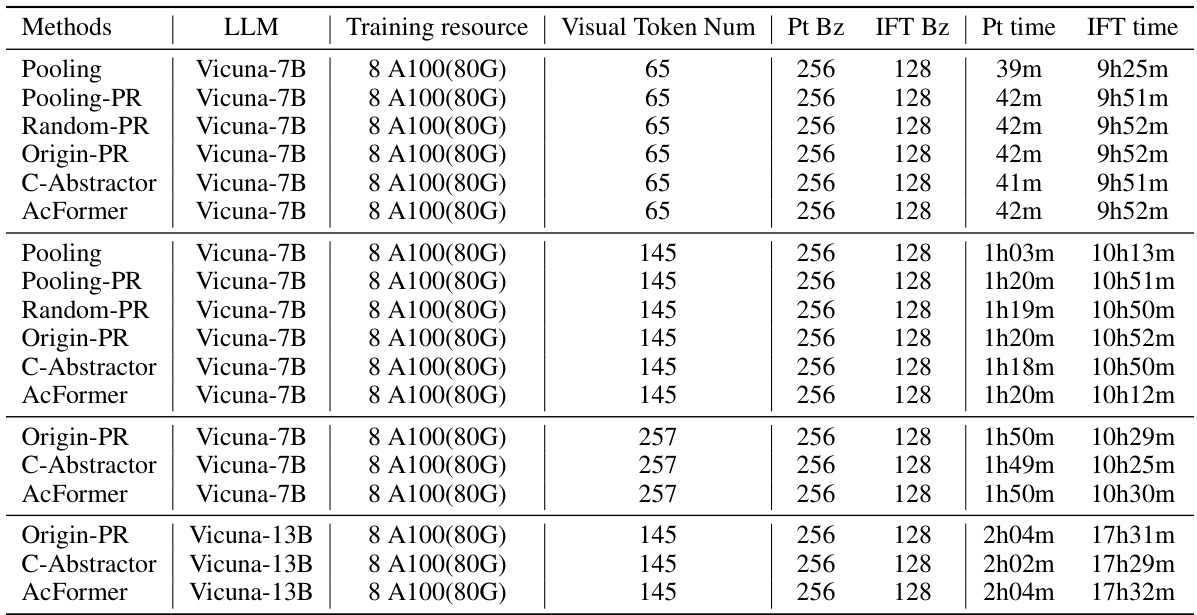

This table shows the training time of different models with various configurations. The training time is broken down into pre-training time and instruction finetuning time. The table includes the model used, the large language model (LLM), the training resources (number of A100 80G GPUs), the number of visual tokens, the pre-training batch size, the instruction finetuning batch size, the pre-training time, and the instruction finetuning time. This allows for a comparison of the training efficiency of different model and configuration.

This table presents nine different benchmarks used to evaluate the performance of Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs). Each benchmark is described with its task description and evaluation metric. The benchmarks cover various aspects of MLLM capabilities including visual perception, complex reasoning, and knowledge integration.

Full paper#