↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Formal verification of AI models is computationally expensive, especially for large models. Existing approaches suffer from high complexity, often focusing on training procedures rather than the models themselves. This paper addresses this by proposing the use of mechanistic interpretability—reverse-engineering model weights to understand the model’s internal functioning. This allows for more efficient proof strategies by focusing on the specific model’s mechanism rather than its overall behavior.

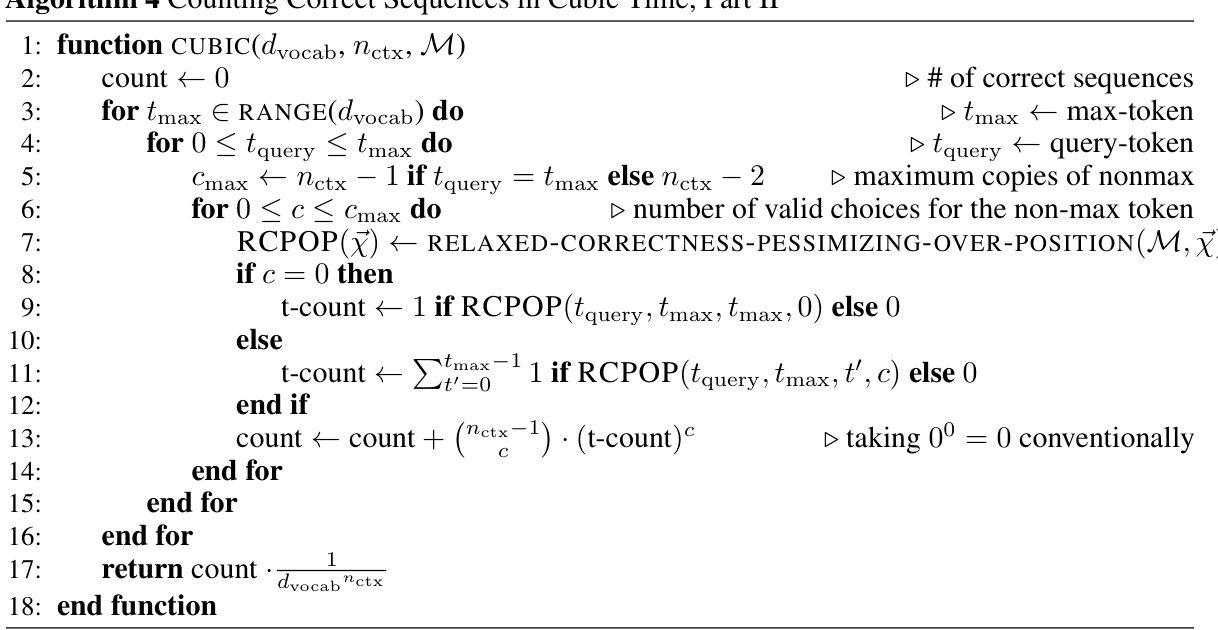

The researchers prototyped their approach on a simplified transformer model trained on a Max-of-K task. They developed various computer-assisted proof strategies, measuring their lengths and the tightness of the performance bounds. Results showed that shorter proofs correlated with more mechanistic understanding and tighter bounds, but also revealed the challenge of compounding structureless errors in generating compact proofs for complex AI models. This work represents a significant advancement toward more efficient and reliable verification of AI systems, particularly emphasizing the use of mechanistic interpretability to improve the efficiency of formal verification.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI safety and reliability research. It introduces a novel approach to formally verify AI models by reverse-engineering their internal mechanisms, paving the way for more efficient and trustworthy AI systems. This addresses a critical challenge in the field, impacting researchers working on formal verification, mechanistic interpretability, and AI safety.

Visual Insights#

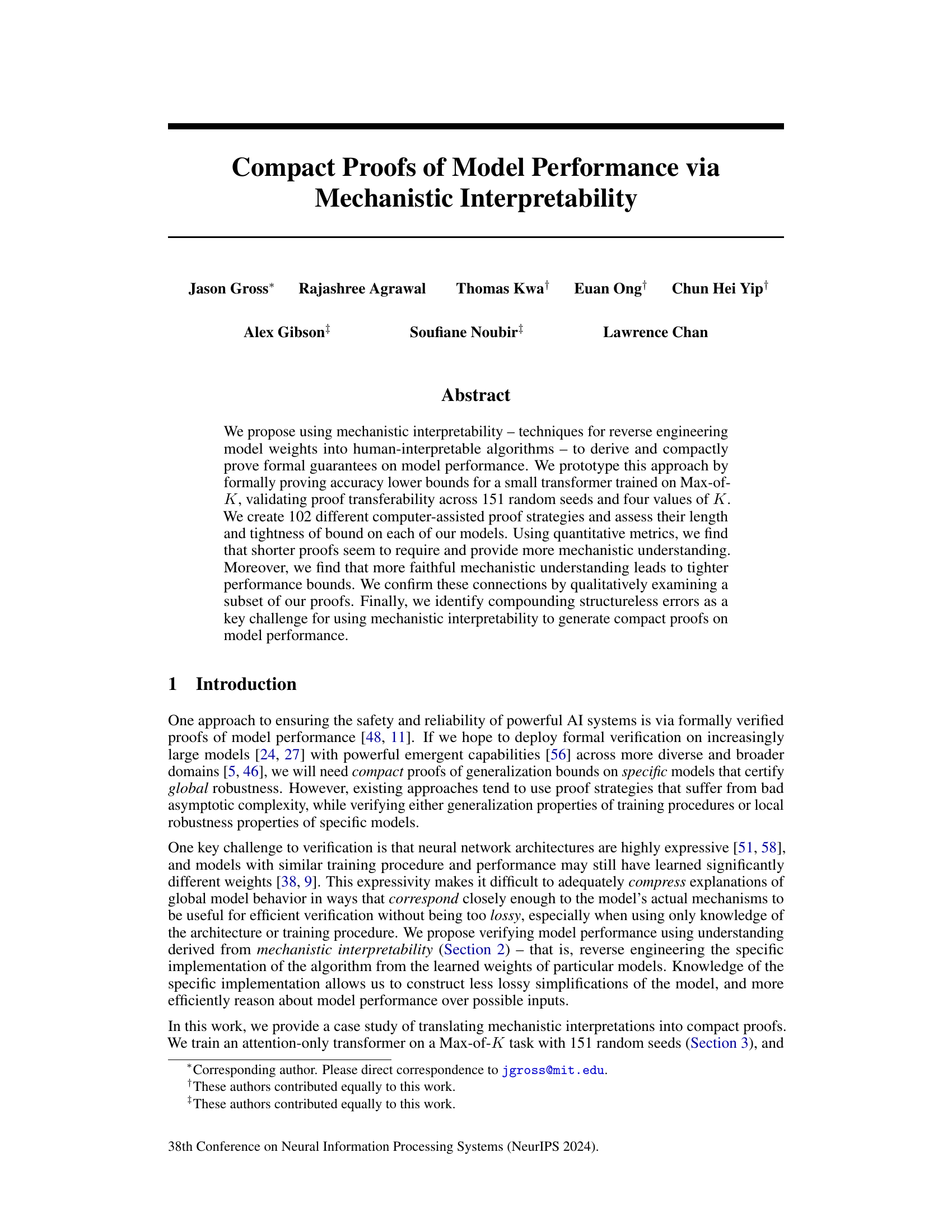

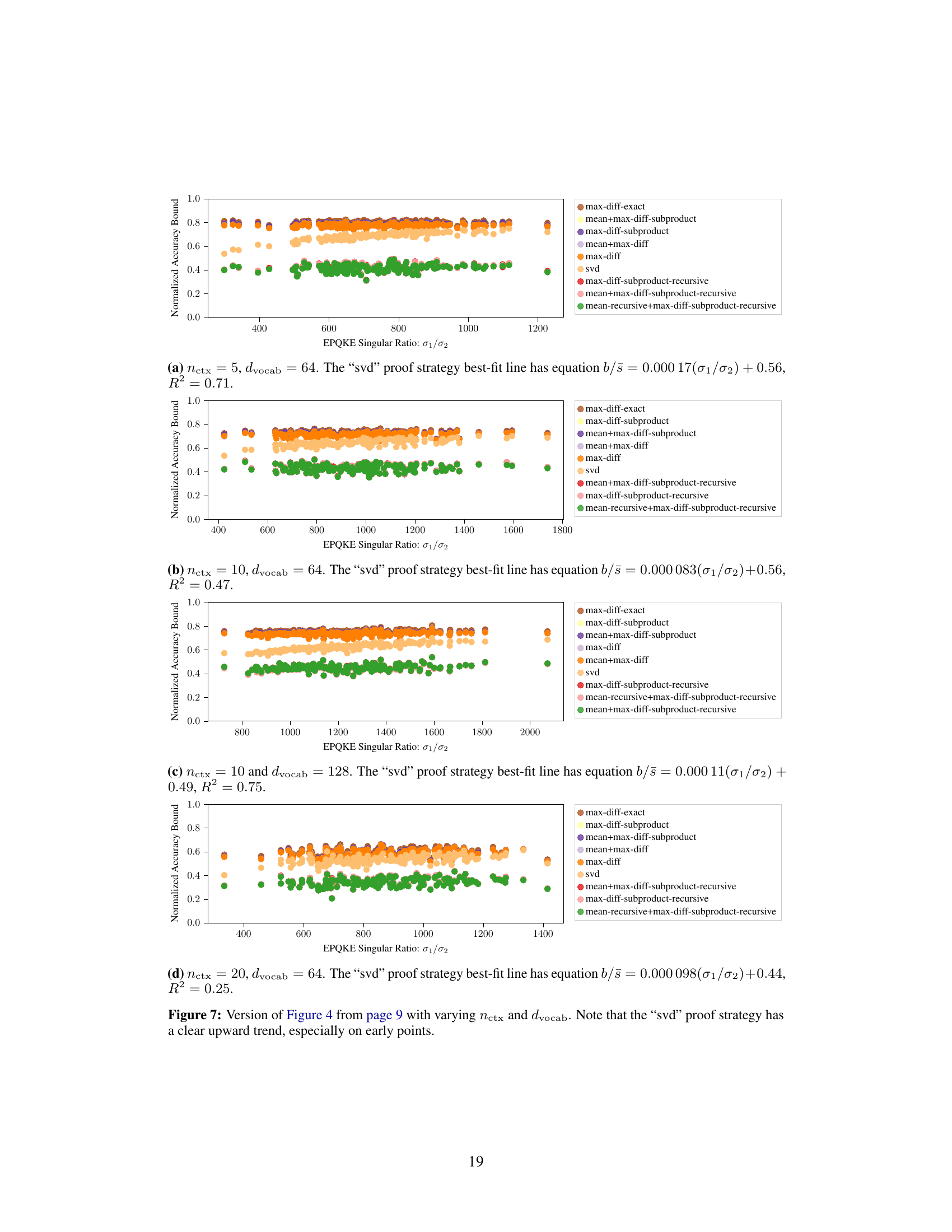

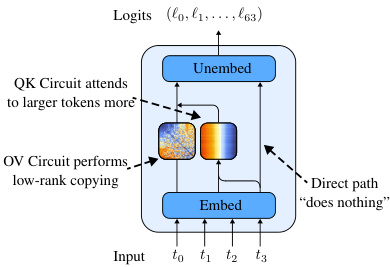

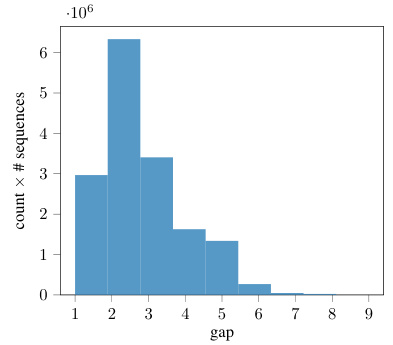

This figure compares three different proof strategies for verifying the performance of a one-layer attention-only transformer model. The strategies differ in their level of mechanistic interpretability, which is the degree to which the model’s internal mechanisms are understood and incorporated into the proof. The brute-force method treats the model as a black box, while the cubic and subcubic methods leverage increasingly detailed mechanistic understanding to create more compact proofs. The figure displays the model architecture, proof strategies, and key metrics for each method (FLOPs required, accuracy lower bound, unexplained dimension, and asymptotic complexity). It highlights the trade-off between proof compactness and accuracy bound tightness, showing that while more compact proofs are achieved with greater mechanistic understanding, those proofs provide less tight bounds.

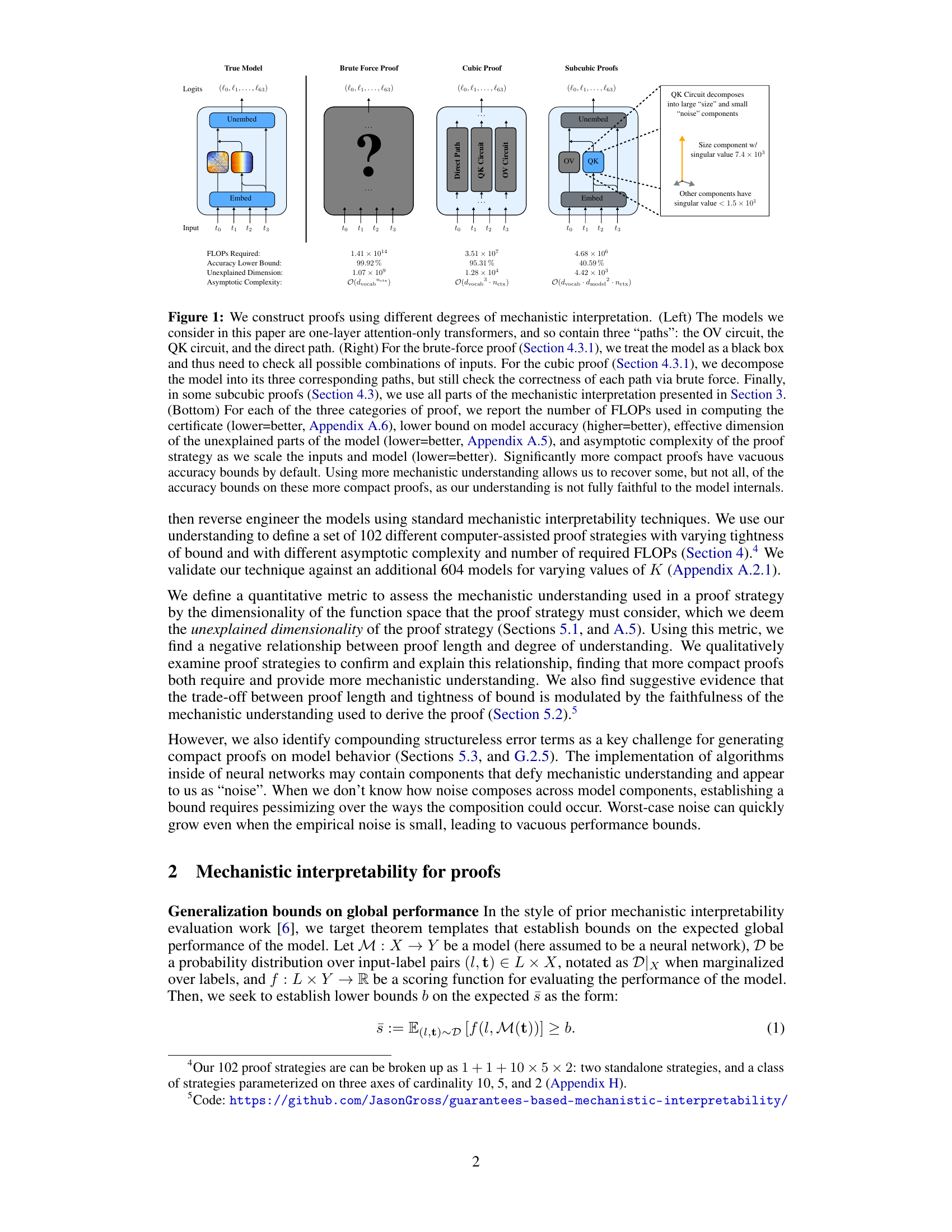

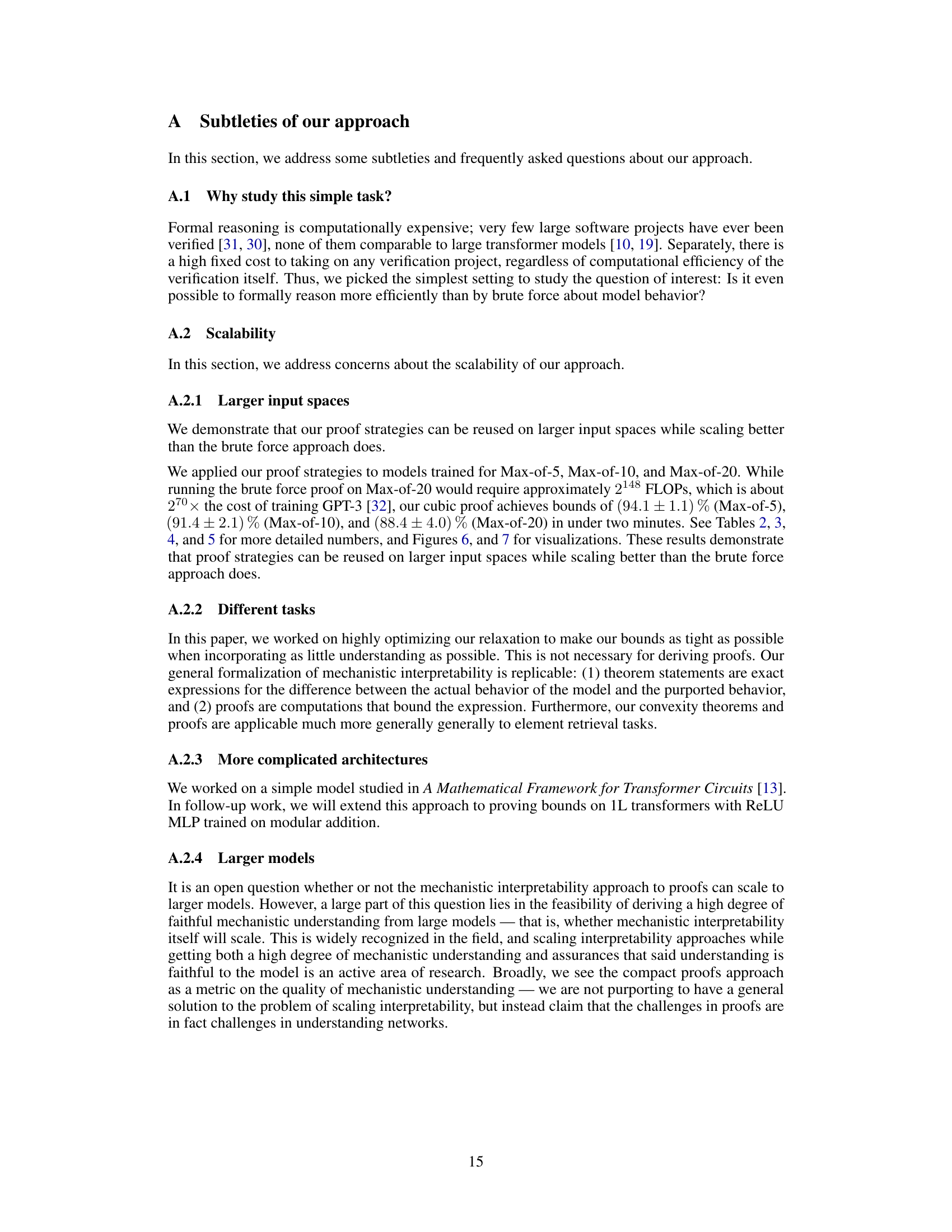

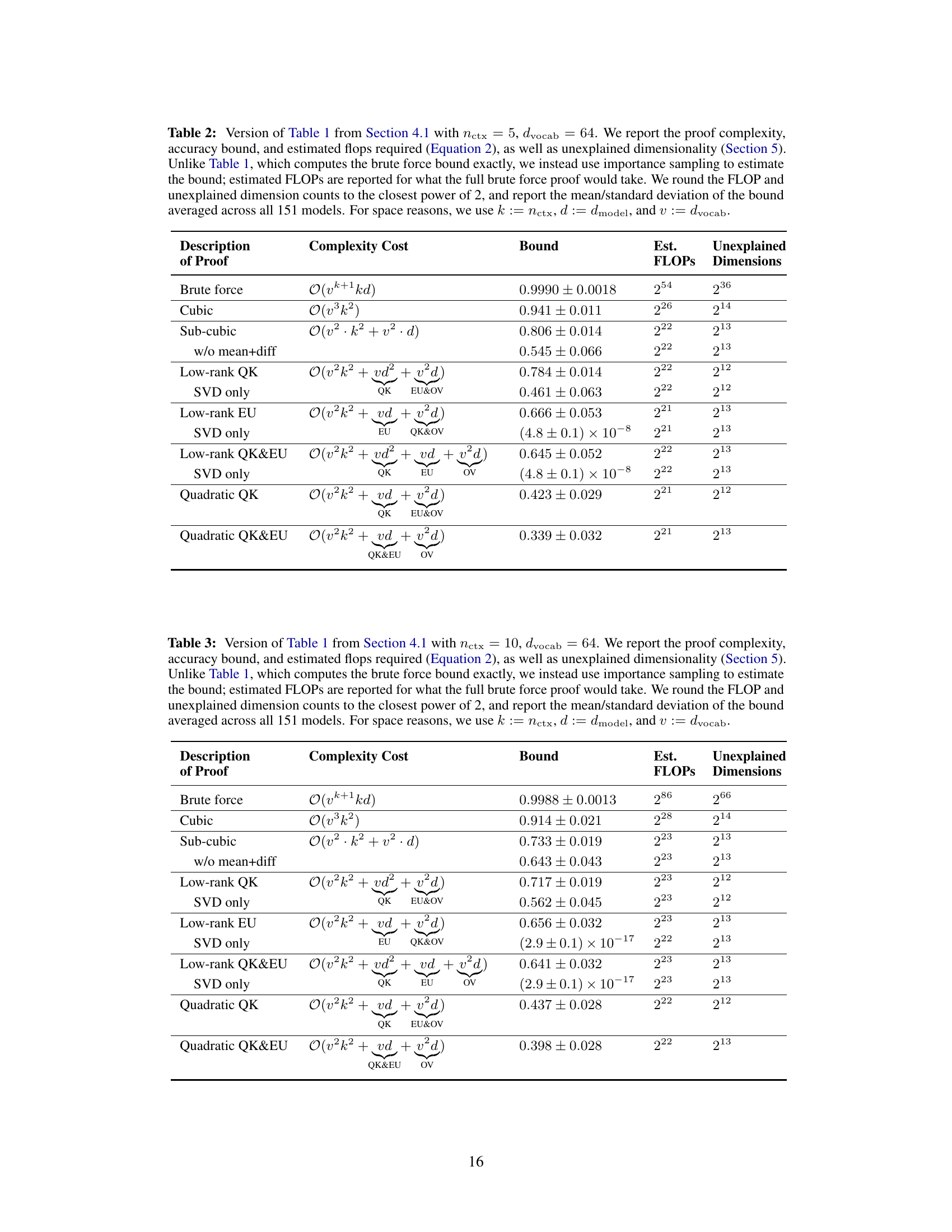

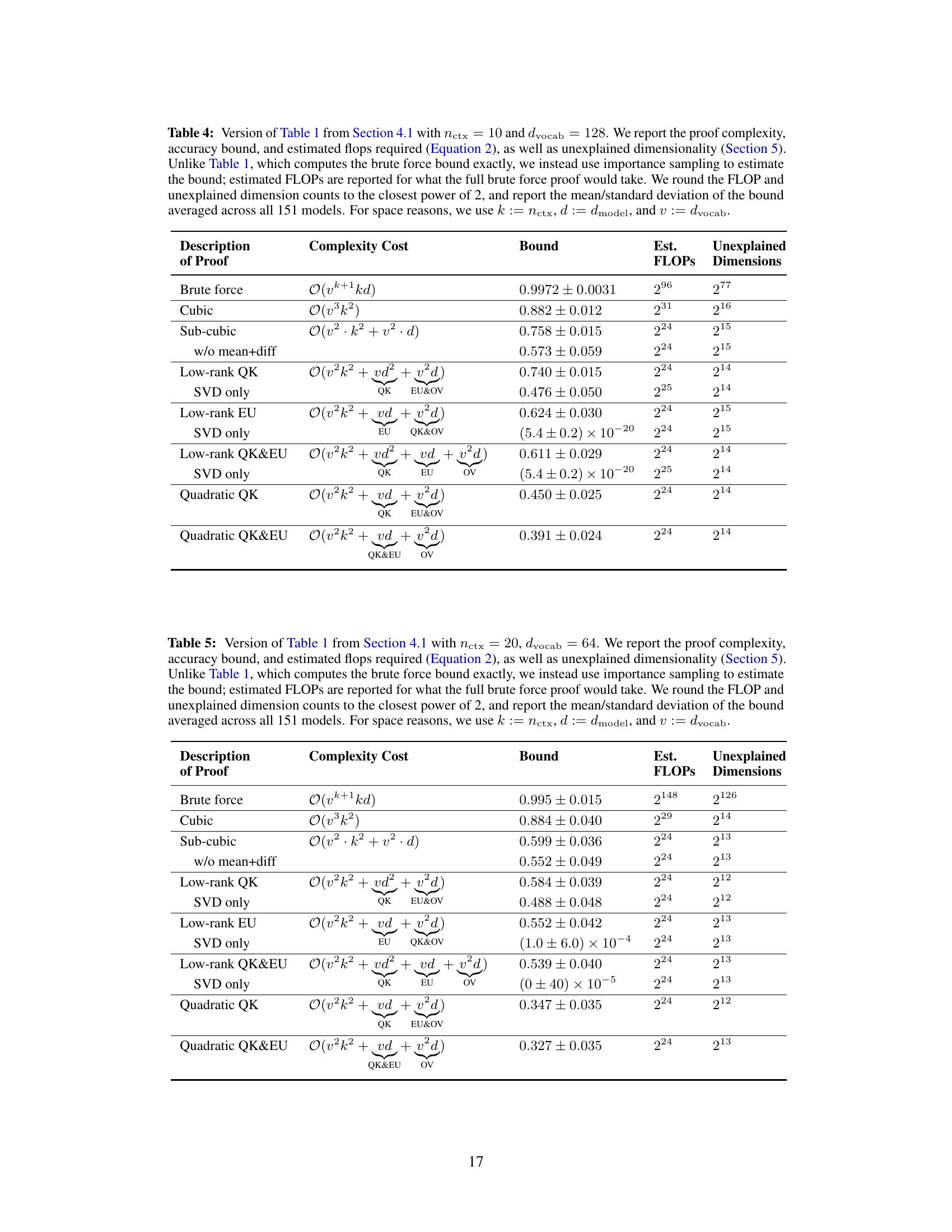

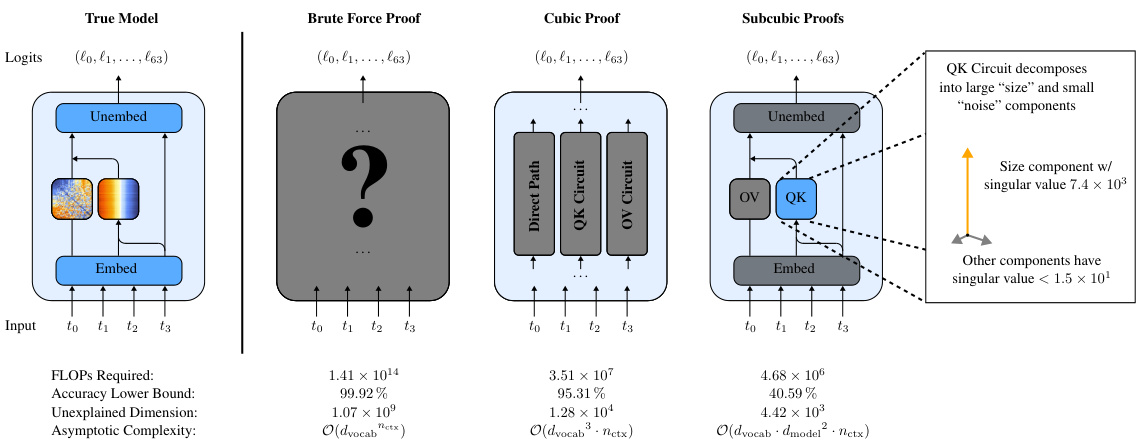

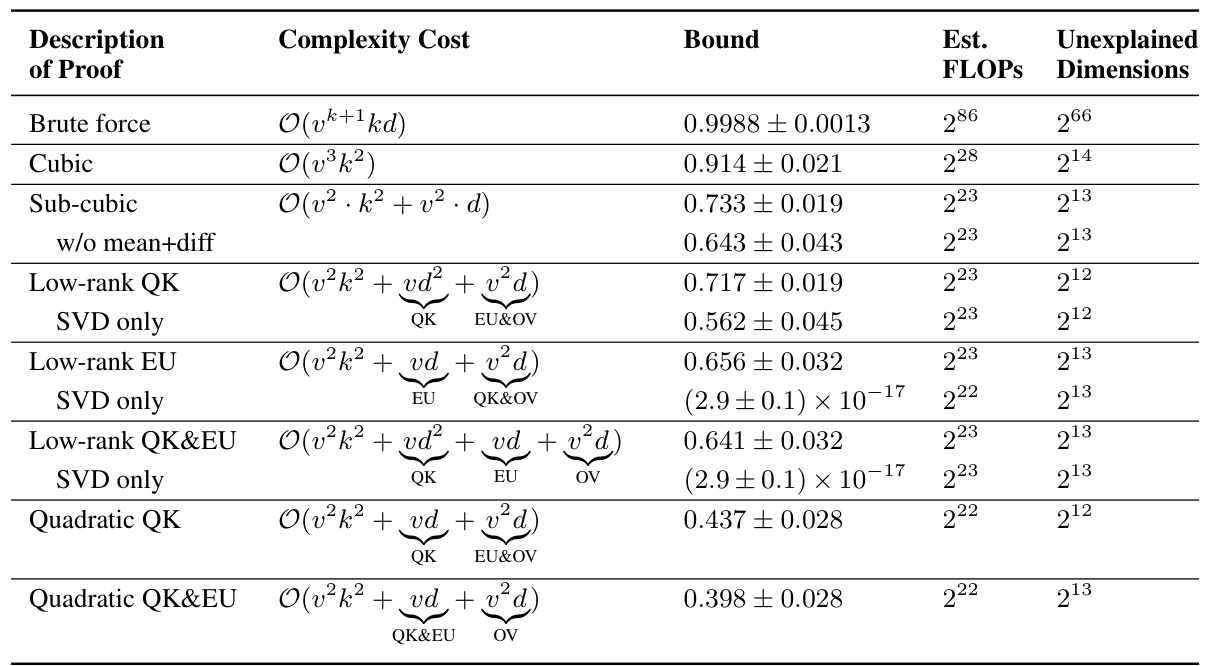

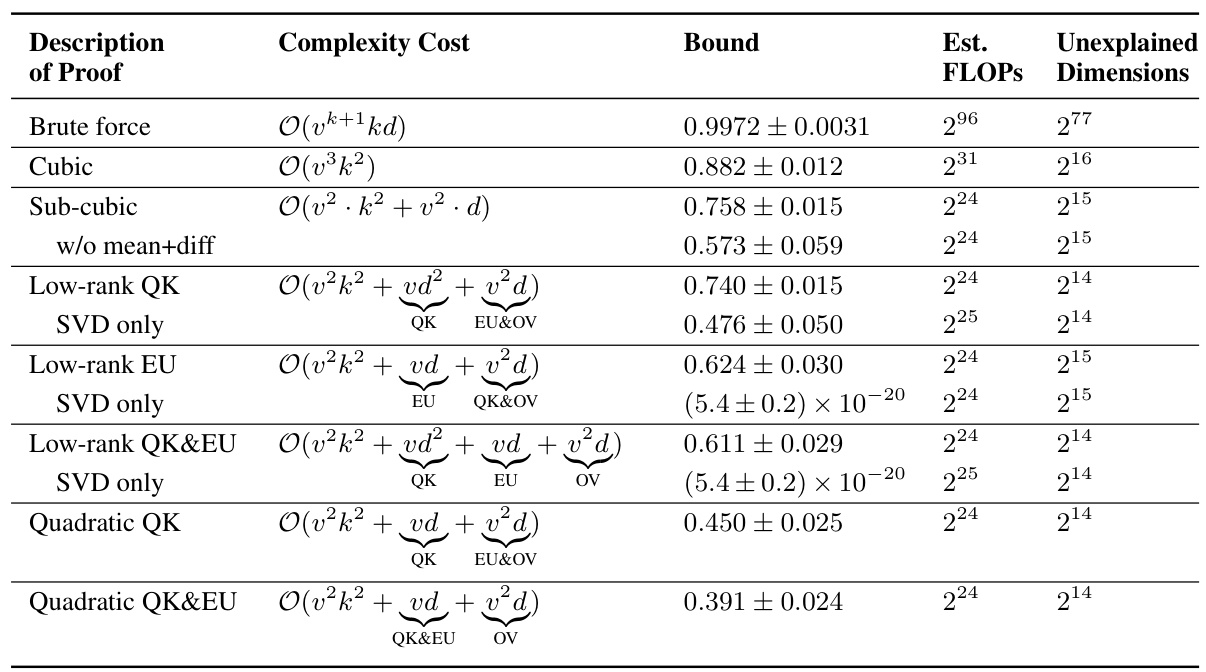

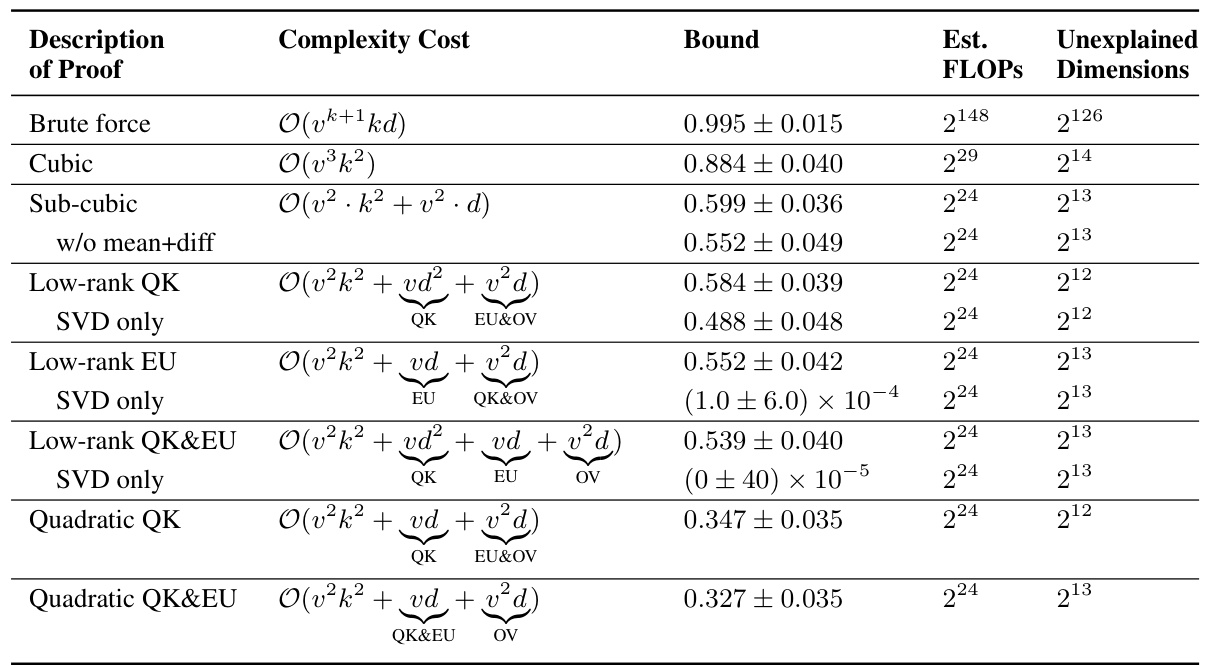

This table summarizes the results of various proof strategies applied to 151 transformer models trained on the Max-of-K task. It compares different proof strategies in terms of their computational complexity (asymptotic complexity and estimated FLOPs), the tightness of the accuracy lower bound they provide, and the amount of mechanistic understanding they require (measured by unexplained dimensionality). The table shows a trade-off between proof compactness and bound tightness: shorter proofs tend to have looser bounds, while tighter bounds require more computationally expensive proofs. Interestingly, it also highlights a correlation between shorter proofs and greater mechanistic understanding. The table uses simplified notation (k for nctx, d for dmodel, and v for dvocab) for brevity.

In-depth insights#

Mechanistic Proofs#

The concept of “Mechanistic Proofs” in AI safety research represents a significant advancement. It proposes leveraging mechanistic interpretability—understanding the inner workings of a model—to formally verify its behavior and performance. Unlike traditional approaches that treat models as black boxes, mechanistic proofs aim to create human-understandable explanations of model behavior. This enables the generation of compact, verifiable proofs guaranteeing model reliability and robustness. A key advantage is the potential for scalability, unlike methods struggling with computational complexity. Challenges remain, notably the difficulty of handling “noise” or unexplained model components and ensuring the faithfulness of the mechanistic interpretation to the model’s actual behavior. Future work should address these challenges, and focus on improving the scalability and applicability of these methods to larger, more complex models, ultimately contributing significantly to the development of trustworthy and safe AI systems.

Max-of-K Models#

The concept of ‘Max-of-K Models’ is intriguing, suggesting a simplified yet insightful approach to understanding complex neural networks. These models, likely focusing on a Max-of-K task where the network outputs the index of the Kth largest element in an input sequence, offer a reduced complexity setting for exploring core concepts of mechanistic interpretability. Their simplicity allows researchers to reverse engineer the model’s internal mechanisms more easily, gaining deeper insights into how the network weights relate to its function. This is crucial for developing and validating compact proofs of model performance, which is the central focus of the research paper. Furthermore, by training multiple Max-of-K models using varied random seeds, the study provides robustness checks by demonstrating the transferability of the proofs across different model instantiations. The use of a Max-of-K framework represents a pragmatic choice, balancing analytical tractability with the potential to illuminate general principles applicable to larger and more intricate models. By studying the relationship between proof length, accuracy bounds, and mechanistic understanding in these models, researchers can establish a valuable benchmark for future research focusing on more complex systems and tasks.

Proof Compactness#

Proof compactness in the context of verifying AI model performance is crucial. The paper explores the trade-off between proof length and accuracy. Shorter proofs, desirable for efficiency, often result in looser, less informative bounds on model accuracy. Conversely, longer, more detailed proofs provide tighter bounds but at the cost of increased computational complexity. The core idea is to leverage mechanistic interpretability, reverse-engineering model weights to understand the model’s internal workings, to generate more compact, yet accurate, proofs. This approach aims to strike a balance, achieving verifiably robust models without excessive computational demands. A key challenge is handling compounding structureless errors, where approximation errors accumulate across model components, potentially yielding vacuous bounds despite substantial effort. The authors quantify ‘mechanistic understanding’ and show that more understanding leads to shorter, though sometimes less tight, proofs. The paper’s contribution is a methodology, not a single, definitive solution, highlighting the need for further research to improve the balance between proof compactness and accuracy in model verification.

Interpretability Limits#

The heading ‘Interpretability Limits’ prompts a critical examination of the boundaries of current mechanistic interpretability techniques. A central challenge highlighted is the difficulty in scaling interpretability methods to larger, more complex models. While reverse-engineering model weights to extract human-understandable algorithms is a powerful approach, the inherent complexity of large neural networks presents substantial hurdles. This complexity manifests in two main ways: first, the sheer computational cost involved in analyzing vast numbers of parameters quickly becomes prohibitive; second, the emergence of ‘structureless errors’ that resist straightforward mechanistic explanations poses a major obstacle to generating compact and meaningful proofs about model performance. Faithful mechanistic interpretations are crucial for deriving tight performance bounds, but even with careful reverse engineering, fully faithful models are extremely difficult to obtain, and compromises inevitably lead to looser, less useful guarantees. Addressing these limitations is key to advancing mechanistic interpretability and generating useful guarantees for the performance of increasingly powerful AI systems.

Future Work#

The paper’s “Future Work” section suggests several promising avenues for extending their research. Scaling to larger models is a crucial next step, moving beyond the small, one-layer transformer used in this study to address more complex architectures and tasks. This involves investigating whether the mechanistic interpretability techniques used can effectively be applied to larger models and whether the compact proof strategies can scale accordingly. The research also highlights the need to explore different algorithmic tasks. Their current work focused on a simplified Max-of-K task, limiting generalizability. Testing the methodology on diverse, more challenging tasks is essential to demonstrate its broader applicability. Addressing compounding structureless errors is another significant challenge that requires further investigation. The authors propose exploring ways to relax from worst-case pessimal ablations to more realistic typical-case scenarios to produce more practical and useful results. Finally, the study was limited to attention-only transformers; exploring models that include MLPs or LayerNorm will provide valuable insights into the robustness of the approach and its generalizability across different model architectures.

More visual insights#

More on figures

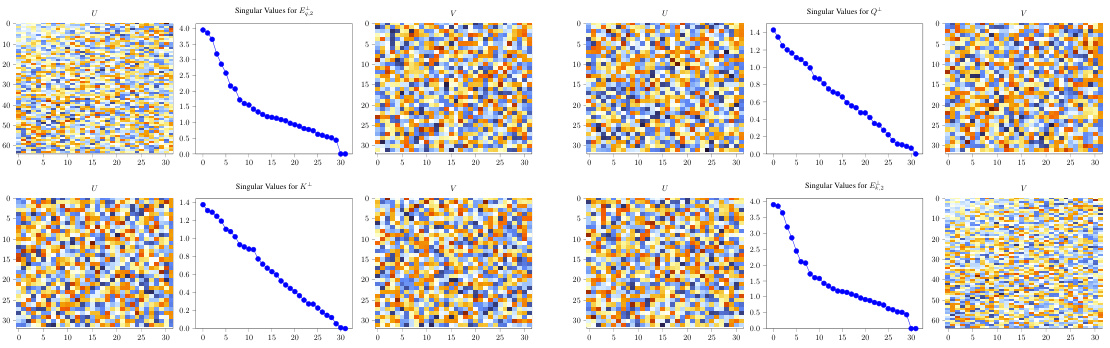

This figure illustrates how different degrees of mechanistic interpretability can be used to construct proofs of model performance. Three proof strategies are compared: brute-force, cubic, and subcubic. The brute-force method treats the model as a black box. The cubic method decomposes the model into three paths (OV, QK, direct) but uses brute force on each. The subcubic method leverages mechanistic interpretability for more compact and efficient proofs, but with potentially looser bounds. The figure shows a comparison of FLOPs, accuracy lower bounds, and unexplained model dimensions for each approach.

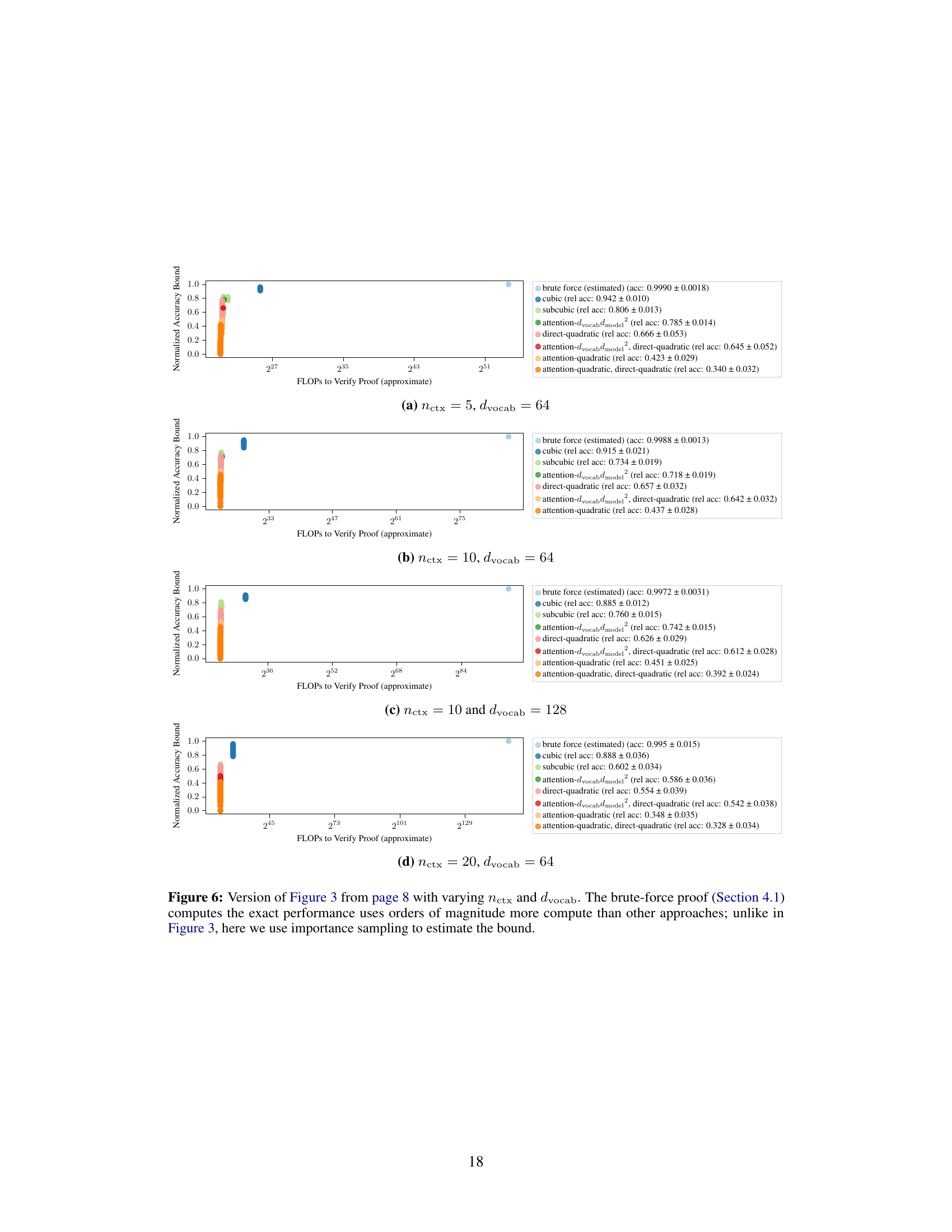

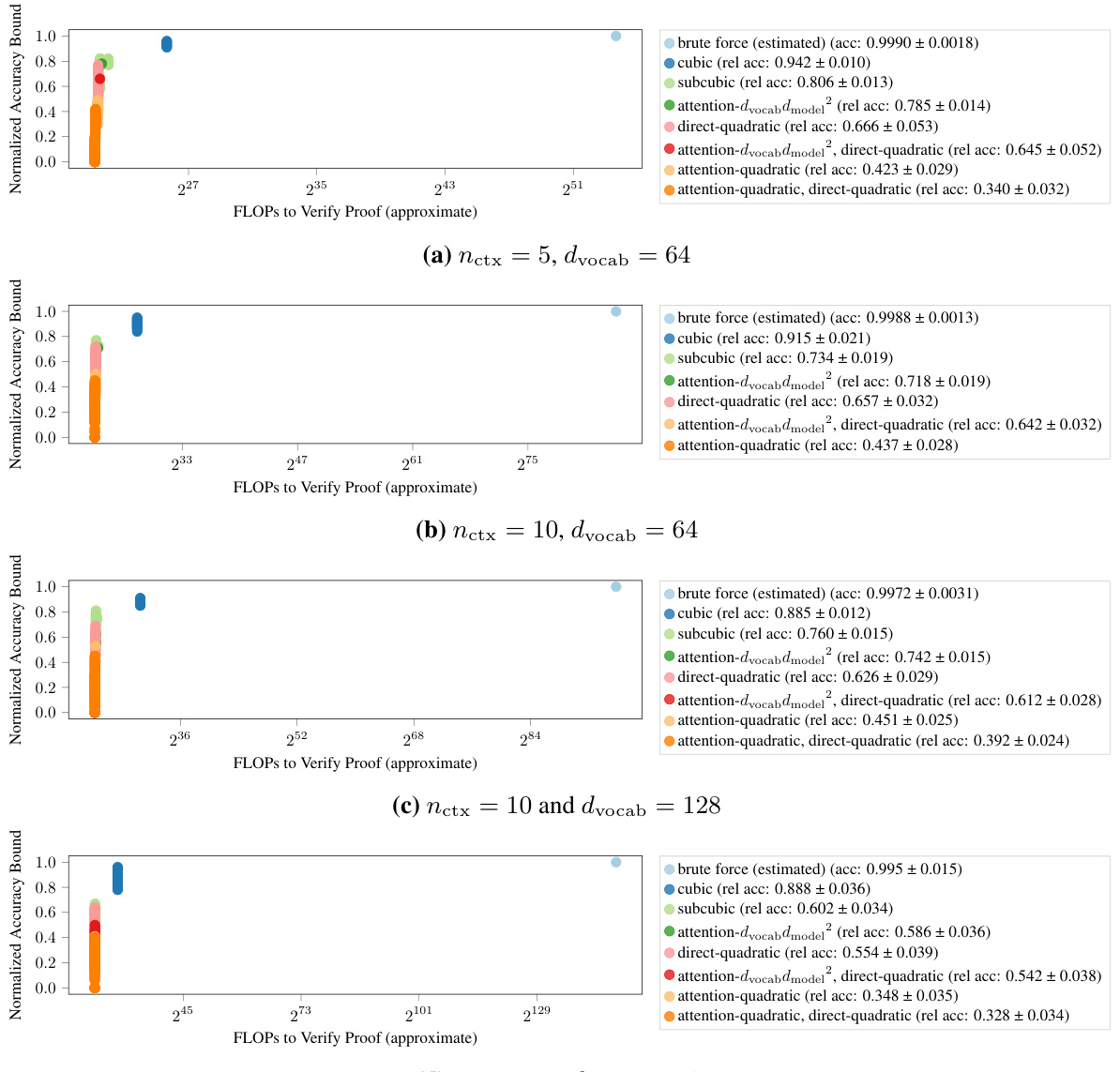

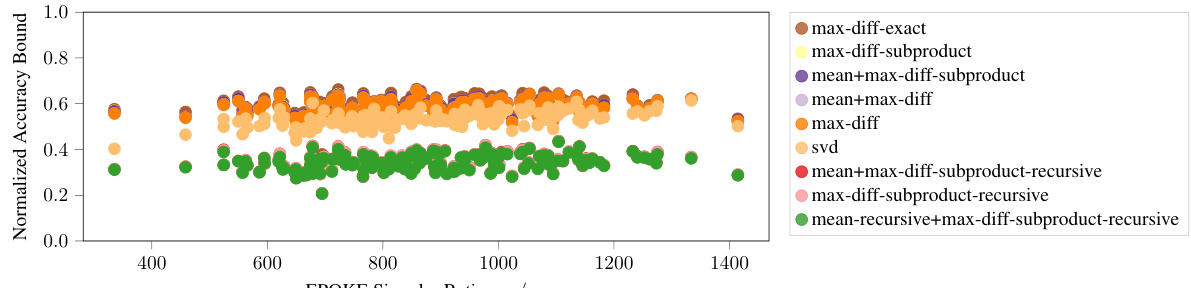

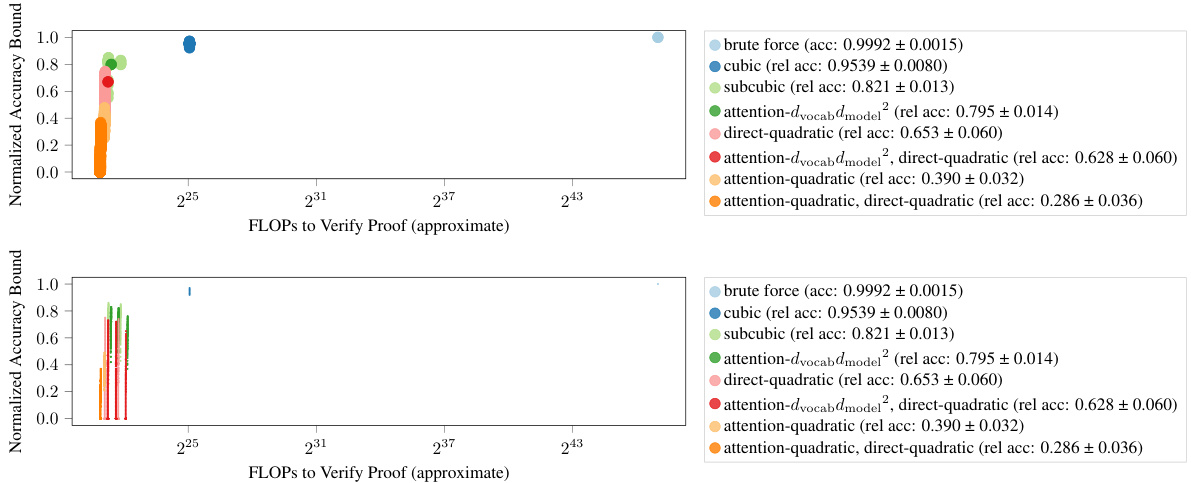

This figure shows the trade-off between the computational cost of the proof and the tightness of the accuracy lower bound. The brute-force approach is the most accurate but computationally expensive, while subcubic proofs achieve greater computational efficiency at the cost of lower accuracy bounds. The cubic proof offers a compromise between cost and accuracy.

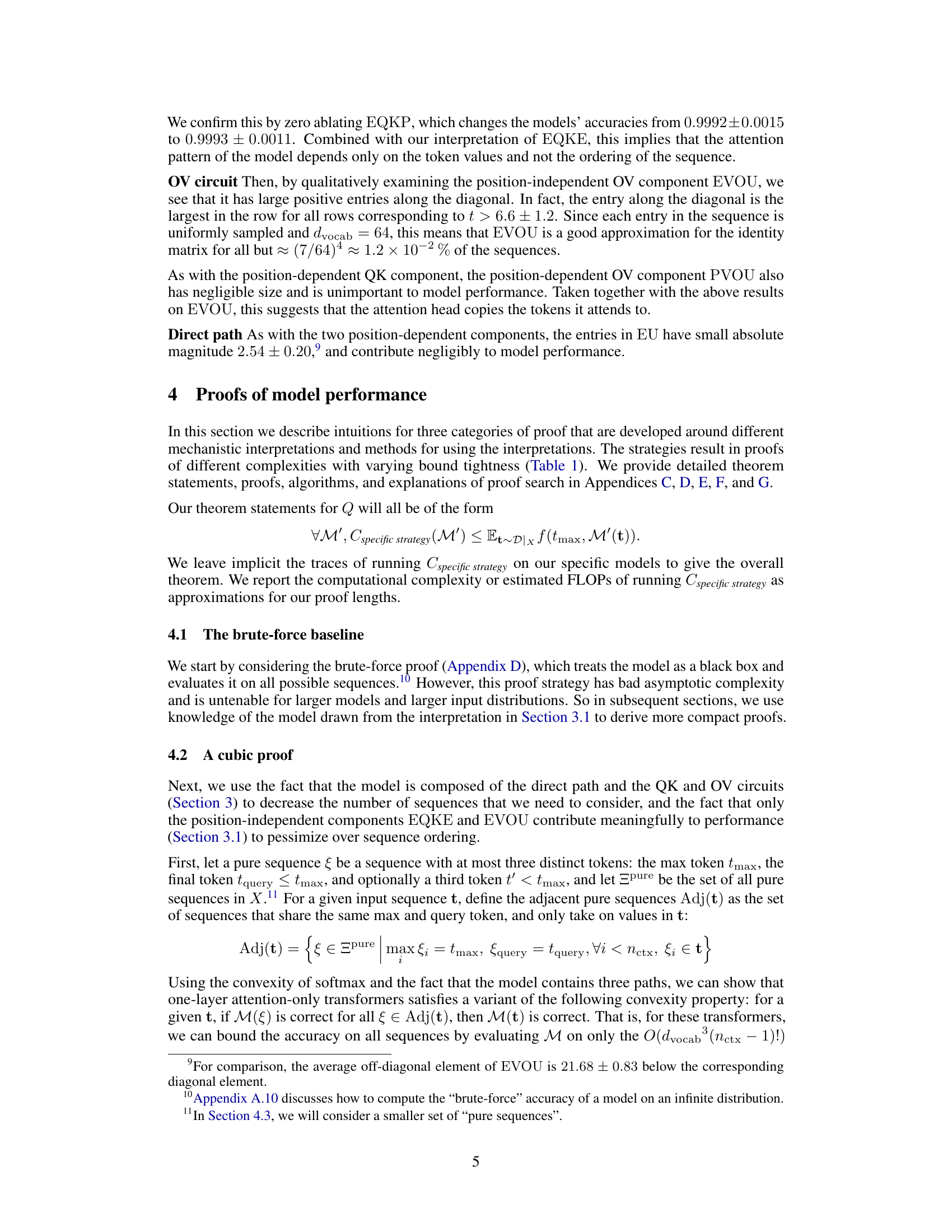

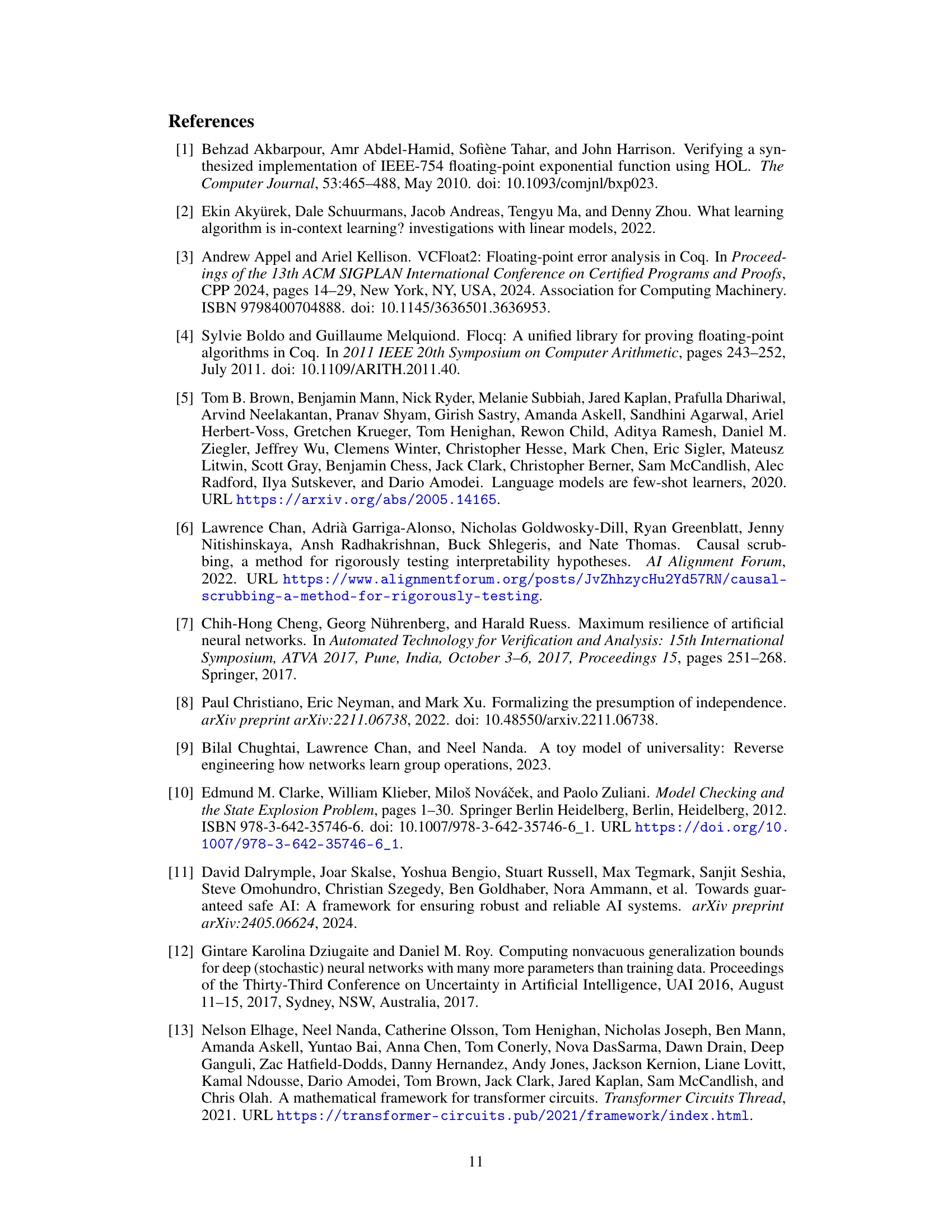

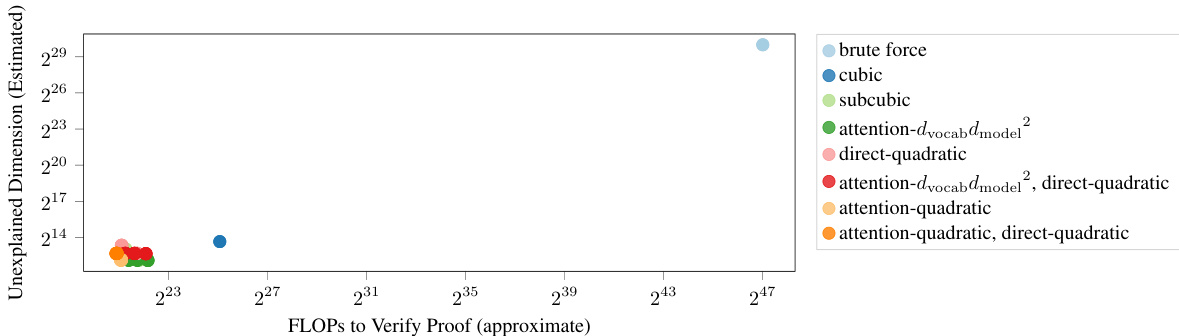

This figure shows the relationship between the computational complexity of a proof (measured in FLOPs) and the amount of mechanistic understanding used in that proof (measured in unexplained dimensions). It supports the paper’s claim that more compact (less computationally expensive) proofs tend to require and provide more mechanistic understanding. The chart visually represents this relationship by plotting FLOPs against unexplained dimensions for various proof strategies. A lower number of unexplained dimensions suggests a higher degree of mechanistic understanding which, as the paper argues, leads to more compact proofs.

This figure shows the trade-off between the computational cost (measured in FLOPs) and the tightness of the accuracy lower bound for different proof strategies. The brute-force method provides the tightest bound but is computationally expensive. Cubic proofs, leveraging some mechanistic understanding, offer a balance between cost and bound tightness. Subcubic proofs, utilizing more comprehensive mechanistic interpretability, reduce the computational cost significantly but achieve looser bounds. The figure demonstrates that increased mechanistic understanding leads to more compact proofs but potentially at the cost of lower bound tightness.

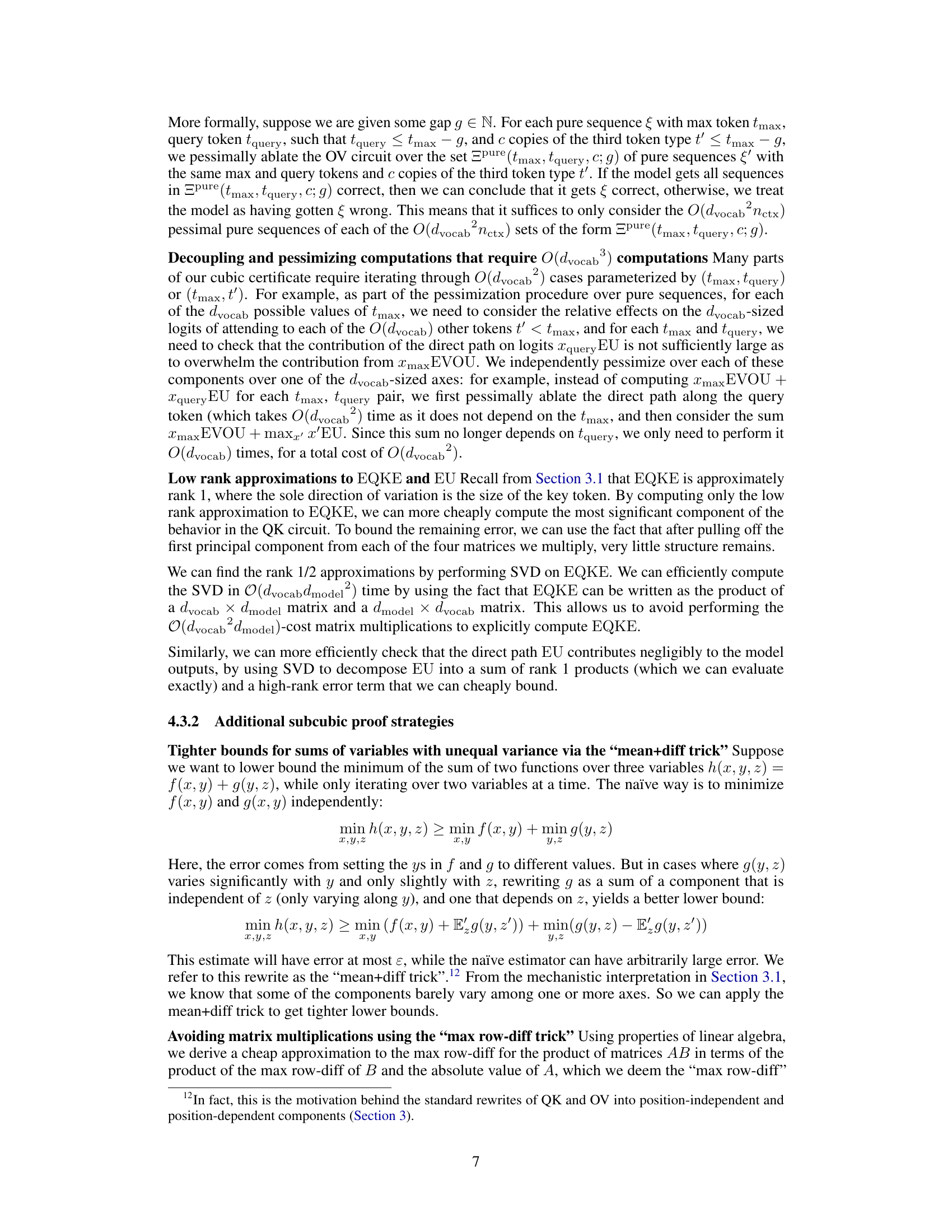

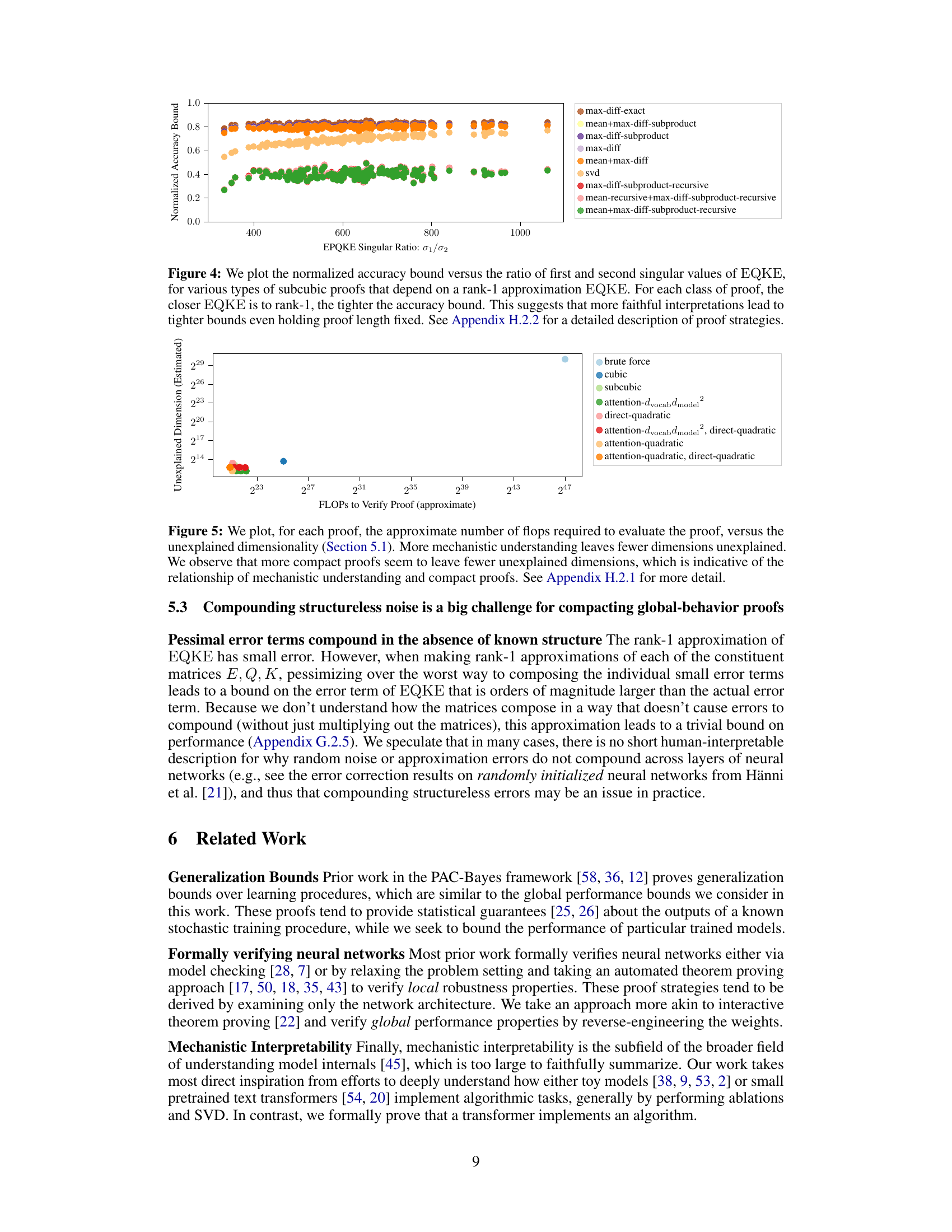

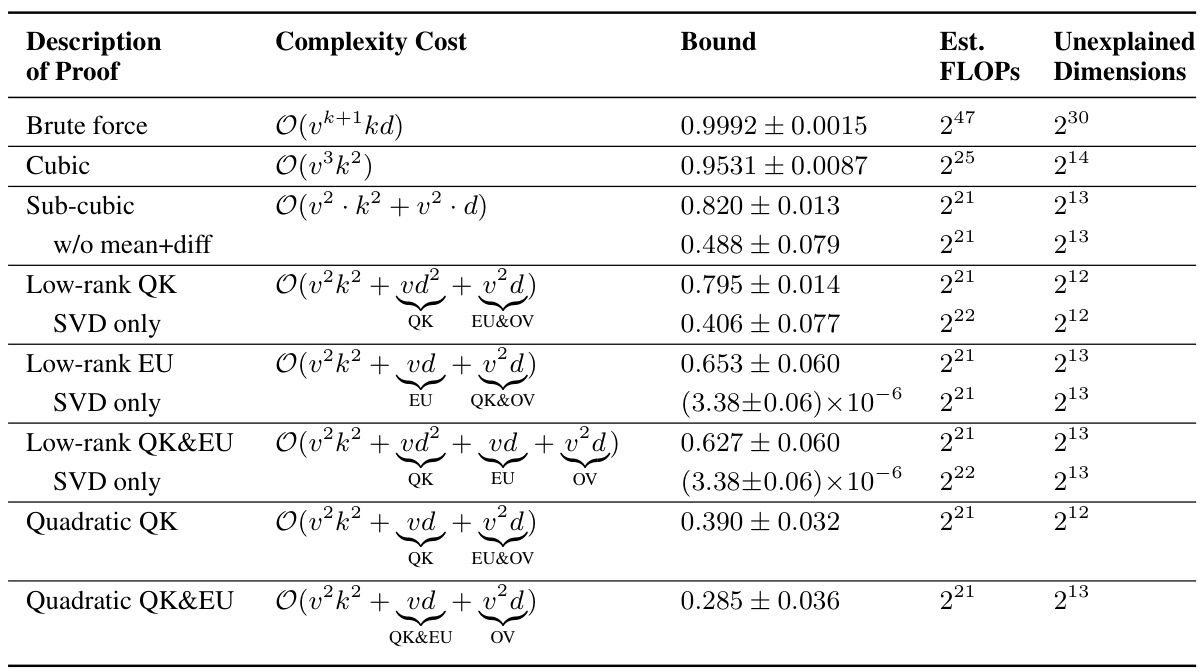

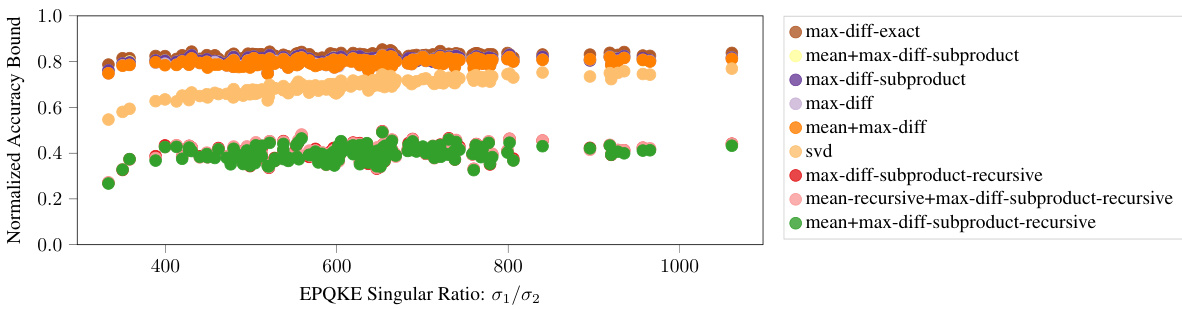

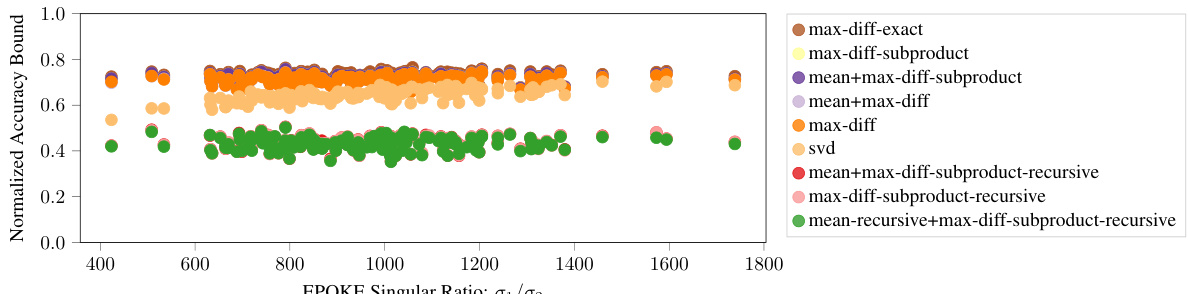

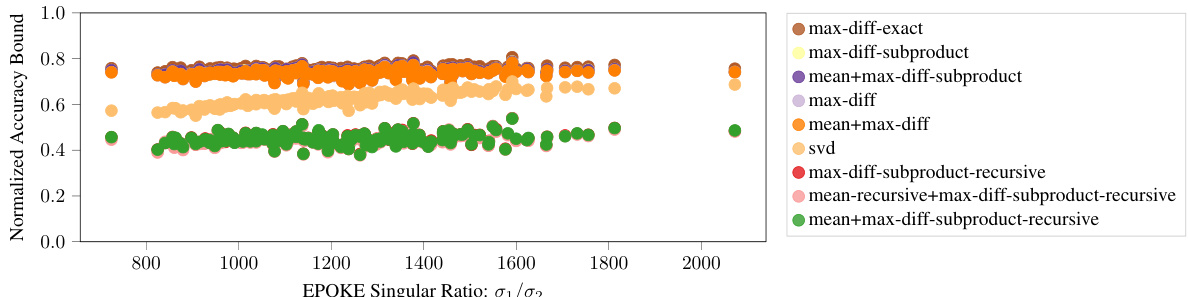

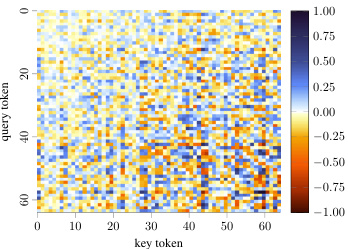

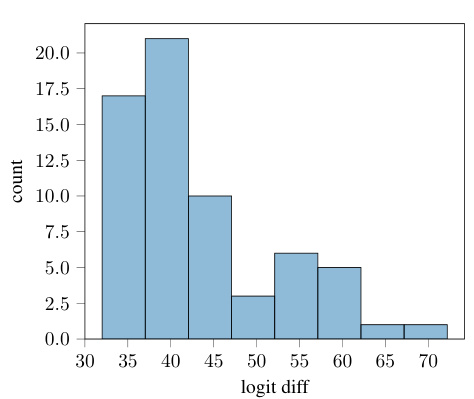

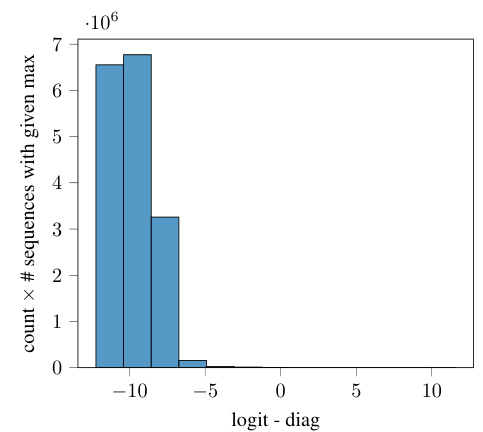

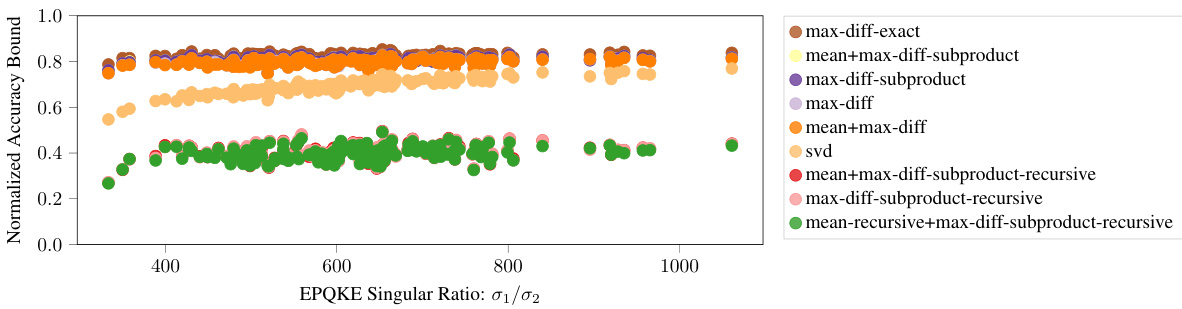

This figure shows the relationship between the normalized accuracy bound and the ratio of the first two singular values of the EQKE matrix for different subcubic proof strategies. The singular values are used as a measure of how close the EQKE matrix is to a rank-1 approximation. The results indicate that a more faithful rank-1 approximation of the EQKE matrix, indicated by a higher ratio of the first to second singular value, leads to tighter accuracy bounds, even when the computational complexity of the proof is held constant. This supports the idea that more faithful mechanistic interpretations yield tighter bounds on model performance.

This figure shows the trade-off between the computation cost and the tightness of the lower bound on accuracy for different proof strategies. The brute-force approach provides the tightest bound but is computationally expensive. As more mechanistic interpretability is incorporated into the proof strategies (moving from brute-force to cubic to subcubic), the computational cost decreases, but the tightness of the lower bound also decreases. The figure demonstrates that while mechanistic interpretability enables more compact proofs, it can lead to looser accuracy bounds. A detailed explanation of the proof strategies is available in the appendix.

This figure shows the relationship between the normalized accuracy bound and the ratio of the first two singular values of EQKE for different subcubic proof strategies. The x-axis represents the ratio of the first two singular values (a measure of how close EQKE is to a rank-1 matrix), while the y-axis represents the normalized accuracy bound. Each point represents a specific proof strategy. The figure demonstrates that as the ratio increases (indicating a closer approximation to a rank-1 matrix), the normalized accuracy bound also tends to increase. This supports the idea that more faithful mechanistic interpretations (represented by a closer approximation to rank-1) lead to tighter accuracy bounds, even when the proof length remains constant.

This figure shows the trade-off between the computational cost and accuracy of different proof strategies for verifying the performance of a Max-of-K model. The brute-force approach is the most accurate but computationally expensive. Cubic proofs, using some mechanistic interpretation, reduce the cost while maintaining relatively high accuracy. Sub-cubic proofs, leveraging a deeper mechanistic understanding, significantly reduce the computational cost, but with a tradeoff in accuracy. The figure highlights that the depth of mechanistic interpretability impacts both efficiency and accuracy of model verification.

The figure shows the relationship between the length of a proof and the tightness of the bound it provides. A shorter proof is faster to compute, but generally leads to a looser bound on the model’s performance. However, by incorporating mechanistic understanding of the model, it is possible to achieve tighter bounds without dramatically increasing the proof’s length. The figure illustrates that there’s a trade-off between proof length (computational cost) and tightness of bound (accuracy of the guarantee).

This figure illustrates the trade-off between proof length (computational cost) and the tightness of the lower bound on model performance. The orange curve shows that shorter proofs generally lead to looser bounds. However, the black arrow indicates that a deeper mechanistic understanding (more faithful interpretation of the model’s internal mechanisms) can partially recover the lost tightness in bounds, even for shorter proofs. It highlights that while shorter proofs are desirable, the faithfulness of the mechanistic interpretation is crucial for achieving tight bounds on model performance.

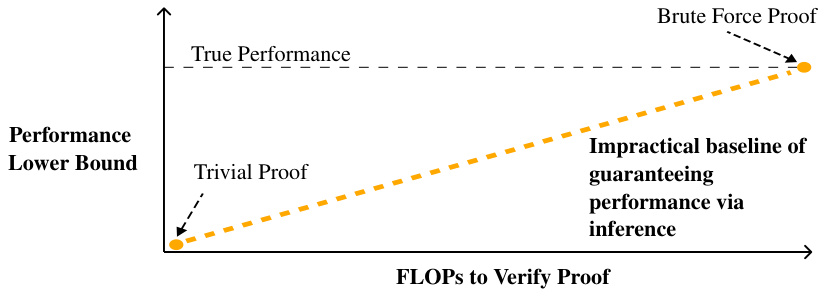

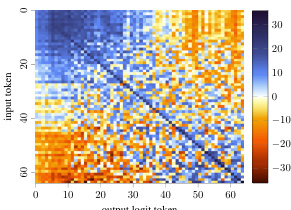

This figure shows the decomposition of the QK circuit into position-independent and position-dependent components. The heatmaps visualize the pre-softmax attention scores computed by the model. The position-independent component (EQKE) shows a clear gradient indicating that larger key tokens receive more attention, regardless of the query token. Conversely, the position-dependent component (EQKP) shows minimal contribution to the attention score. This suggests that the model’s attention mechanism primarily focuses on the magnitude of the key tokens and is less sensitive to their position within the sequence.

This figure shows the decomposition of the QK circuit into position-independent and position-dependent components. The heatmaps visualize the pre-softmax attention scores computed by the model. The position-independent component (EQKE) demonstrates a clear bias towards larger key tokens, indicating that the model attends more to larger tokens regardless of their position. Conversely, the position-dependent component (EQKP) shows minimal contribution to the overall attention score, suggesting that the model’s attention mechanism primarily relies on token values rather than their positions. The patterns of light and dark bands further indicate that certain query tokens are more effective at focusing on larger keys than others.

This figure shows the trade-off between proof length and accuracy. The brute-force method is the most accurate but computationally expensive. As more mechanistic interpretability is incorporated into the proof strategies, the computational cost decreases, but so does the accuracy of the lower bound. This highlights the challenge of balancing conciseness with accuracy in proofs of model performance.

This figure shows the trade-off between the computational cost of verifying a proof and the tightness of the accuracy lower bound obtained. The brute-force method is the most accurate but computationally expensive. Cubic proofs use mechanistic interpretability to reduce computation but with a less tight bound. Subcubic proofs leverage further mechanistic understanding to drastically reduce computation, although the resulting bound becomes looser.

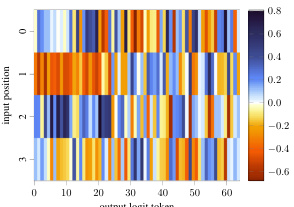

This figure shows the decomposition of the OV circuit into its position-independent and position-dependent components. The position-independent component (EVOU) shows a strong diagonal pattern, indicating that the model copies the tokens that it attends to. This effect is much stronger than the position-dependent component (PVOU). The direct path’s effect is minimal.

This figure shows the trade-off between the computational cost of the proof and the tightness of the lower bound on the accuracy. The brute-force method is the most accurate but computationally expensive. Cubic proofs use some mechanistic interpretability to reduce the computation, while sub-cubic proofs leverage a more complete understanding of the model’s mechanism for significant computational savings, albeit at the cost of a looser lower bound.

This figure shows the tradeoff between proof length (measured in FLOPs) and tightness of the accuracy lower bound. The brute-force method provides the tightest bound but requires significantly more computation. Cubic proofs use some mechanistic interpretability and improve computational efficiency while maintaining relatively good bounds. Subcubic proofs, leveraging more extensive mechanistic understanding, further reduce computation but yield looser bounds. The figure highlights that tighter bounds generally require more computational effort.

This figure shows the decomposition of the QK circuit into position-independent (EQKE) and position-dependent (EQKP) components. The heatmaps visualize the pre-softmax attention scores. The minimal impact of position on attention is evident in the EQKP heatmap. EQKE shows a clear gradient, indicating that the model attends to larger tokens more strongly, independent of the query token. Variability in attention across different query tokens is also observed.

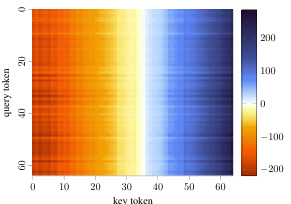

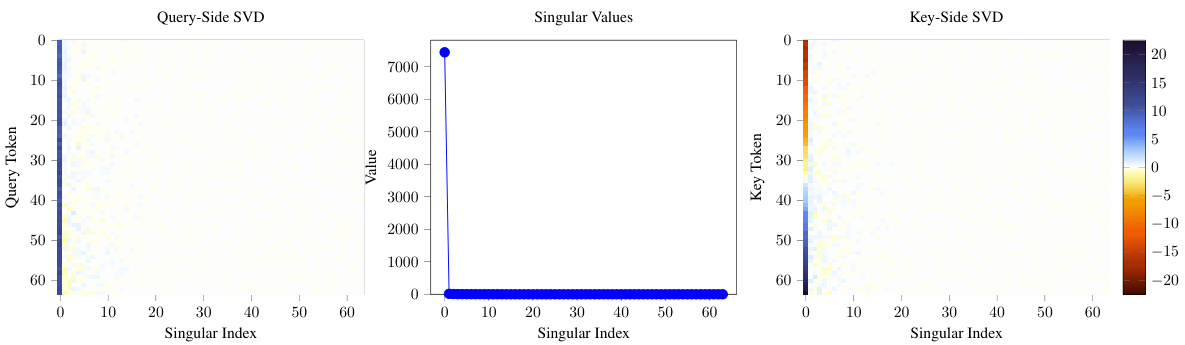

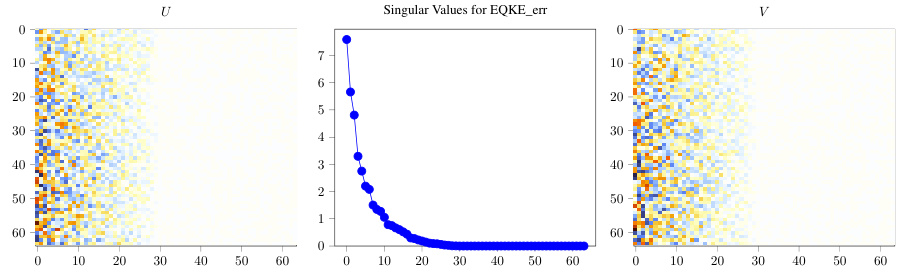

This figure shows the singular value decomposition (SVD) of the EQKE matrix for a specific random seed (seed 123). The SVD decomposes the matrix into three components: U, singular values, and V. The plot shows that the first singular value is significantly larger than all other singular values. The scaling applied to the principal component vectors (U and V) emphasizes the dominance of the first component, visually representing that the EQKE matrix is well approximated by a rank-1 matrix. This observation supports the paper’s argument that the QK circuit primarily focuses on large tokens.

This figure shows the singular value decomposition (SVD) of the EQKE matrix for a specific random seed (seed 123). The SVD decomposes the matrix into singular values and singular vectors. The plot displays the singular values, which represent the strength of the corresponding singular vectors in capturing the variance of the matrix. The plot visually demonstrates that the first singular value is significantly larger than all others. This indicates that the matrix is well-approximated by its rank-one component (using only the first singular value and its corresponding vectors). The caption provides the numerical values of the first two singular values (7440 and 15) to further emphasize the dominance of the first singular value.

This figure shows the trade-off between proof length (measured by FLOPs) and tightness of the lower bound on accuracy. The brute-force approach is the most accurate but computationally expensive. Cubic proofs use some mechanistic interpretability to reduce computation, maintaining accuracy. Subcubic proofs leverage more mechanistic interpretability, resulting in even less computation but slightly lower accuracy bounds.

This figure shows a trade-off between the computational cost and the tightness of the lower bound on the model accuracy for different proof strategies. The brute-force approach is the most accurate but computationally expensive. The cubic proof uses some mechanistic interpretability, requiring less computation while maintaining relatively good accuracy. The subcubic proofs leverage the mechanistic interpretation fully to reduce computation further; however, this leads to less tight bounds.

This figure shows the trade-off between proof length (measured in FLOPs) and tightness of the accuracy lower bound. The brute-force approach provides the tightest bound but is computationally expensive. The cubic proof uses some mechanistic interpretability to reduce computation, and subcubic proofs leverage more mechanistic understanding for further computational savings, but with a sacrifice in bound tightness.

This figure shows the trade-off between proof length (measured in FLOPs) and the tightness of the accuracy lower bound. The brute-force approach is the most accurate but computationally expensive. As more mechanistic understanding is incorporated into the proof strategies (moving from brute-force to cubic to sub-cubic), the computational cost decreases, but so does the tightness of the bound. This illustrates the inherent trade-off between computational efficiency and the strength of the guarantee provided by the proof.

This figure shows the trade-off between the computation cost and the tightness of the lower bound on the accuracy for different proof strategies. The brute-force method is the most accurate but computationally expensive, while subcubic methods, leveraging mechanistic interpretability, achieve much lower computational cost but with less tight bounds.

This figure shows the trade-off between the computation cost and the tightness of the lower bound on model accuracy for different proof strategies. The brute-force approach is the most computationally expensive but provides the tightest bound. The cubic approach uses some mechanistic interpretability and is less computationally expensive, while still providing a relatively tight bound. The subcubic approaches use the most mechanistic interpretability, resulting in the lowest computational cost but also the loosest bounds.

This figure shows the trade-off between proof length (measured in FLOPs) and the tightness of the accuracy lower bound obtained by different proof strategies. The brute-force approach provides the tightest bound but is computationally expensive. Cubic proofs utilize some mechanistic interpretability, resulting in shorter proofs and reasonably good bounds. Subcubic proofs leverage a more complete mechanistic understanding, leading to the most compact proofs, but at the cost of looser bounds. The plot visually demonstrates the relationship between the degree of mechanistic understanding incorporated into the proof strategy and its computational cost and bound accuracy.

More on tables

This table presents a comparison of different proof strategies for verifying model performance. It shows the asymptotic complexity cost, estimated FLOPs, accuracy bound, and unexplained dimensions for each strategy. The table highlights the trade-off between proof compactness and tightness of bounds, indicating that shorter proofs tend to have less accurate bounds and vice versa. It also demonstrates how a deeper mechanistic understanding of the model (represented by fewer unexplained dimensions) can lead to more compact proofs but may sometimes compromise the tightness of the bounds.

This table presents a comparison of different proof strategies for verifying the performance of a Max-of-K model. It shows the trade-offs between proof complexity (asymptotic time complexity and estimated FLOPs), the tightness of the accuracy lower bound, and the degree of mechanistic understanding used in the proof (measured by the unexplained dimensionality). The results suggest that incorporating more mechanistic understanding leads to more compact proofs, but also potentially to looser accuracy bounds. The table also provides a breakdown of proof complexity costs using the notation k=nctx, d=dmodel, and v=dvocab.

This table summarizes the results of applying different proof strategies to 151 transformer models trained on the Max-of-K task. It compares various metrics for each strategy including asymptotic complexity, the accuracy lower bound achieved, the number of floating-point operations (FLOPs) required for computation, and the unexplained dimensionality (a measure of mechanistic understanding). The table shows a trade-off: more compact (lower FLOPs and complexity) proofs lead to looser accuracy bounds but also indicate a higher degree of mechanistic understanding, and vice-versa. The table highlights the impact of mechanistic interpretability on proof compactness and bound tightness.

This table summarizes the results of different proof strategies used to prove lower bounds on the accuracy of a one-layer transformer model trained on a Max-of-K task. Each row represents a different proof strategy, showing its asymptotic complexity cost, the average accuracy bound achieved across 151 model instances, the estimated floating-point operations (FLOPs) required for the proof, and the unexplained dimensionality (a measure of the remaining uncertainty in the model’s behavior not captured by the proof’s mechanistic interpretation). The table highlights the trade-off between proof compactness (low complexity and FLOPs) and tightness of the accuracy bound. Strategies incorporating more mechanistic understanding generally lead to more compact proofs but may result in looser bounds.

This table summarizes the results of different proof strategies used to establish lower bounds on model accuracy. It shows a tradeoff between the complexity/length of the proof and the tightness of the bound. More mechanistic understanding (lower unexplained dimensionality) leads to shorter proofs but potentially looser bounds, while less understanding results in longer, more computationally expensive proofs with tighter bounds. The table provides details about the asymptotic complexity cost, estimated FLOPs, accuracy bound, and unexplained dimensions for each proof strategy.

This table summarizes the results of different proof strategies applied to 151 transformer models trained on the Max-of-K task. It compares various metrics across three categories of proof strategies: brute-force, cubic, and sub-cubic. Metrics include the asymptotic complexity and estimated FLOPs (floating point operations) required to compute the certificate, the accuracy bound achieved, and the unexplained dimensionality (a measure of the mechanistic understanding incorporated in the proof). The table demonstrates a trade-off between proof compactness and the tightness of the accuracy bound, with more compact proofs generally yielding looser bounds but requiring less computation. It also highlights the correlation between shorter proofs and greater mechanistic understanding of the model.

Full paper#