↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Recent research suggests that the emergence of new capabilities in large language models (LLMs) is not solely dependent on model size, but also on the pre-training loss. Previous studies have linked the appearance of certain abilities to the size of the models, leading to the belief that larger models are necessary to achieve these abilities. However, this paper challenges that notion by demonstrating that smaller models can also exhibit high performance on these so-called “emergent” abilities. This casts doubt on the existing metrics used to assess these abilities and the methods used to predict the performance of future models based on the trends of currently available models.

This research proposes a novel definition of emergent abilities based on pre-training loss, demonstrating that these abilities emerge only when pre-training loss drops below a specific threshold. The study uses a consistent data corpus, model architecture, and tokenization across models of varying sizes, showing similar performance on several downstream tasks for models with the same pre-training loss. This finding suggests that pre-training loss is a more reliable predictor of a model’s capabilities than simply extrapolating from the performance trends of larger models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it redefines emergent abilities in language models, shifting the focus from model size to pre-training loss. This new perspective is important for guiding future research directions, resource allocation, and the development of more efficient and effective models. The findings challenge existing assumptions about scaling laws and pave the way for more accurate predictions of model capabilities. It offers a more practical way to predict model capabilities, impacting resource allocation and the design of future models.

Visual Insights#

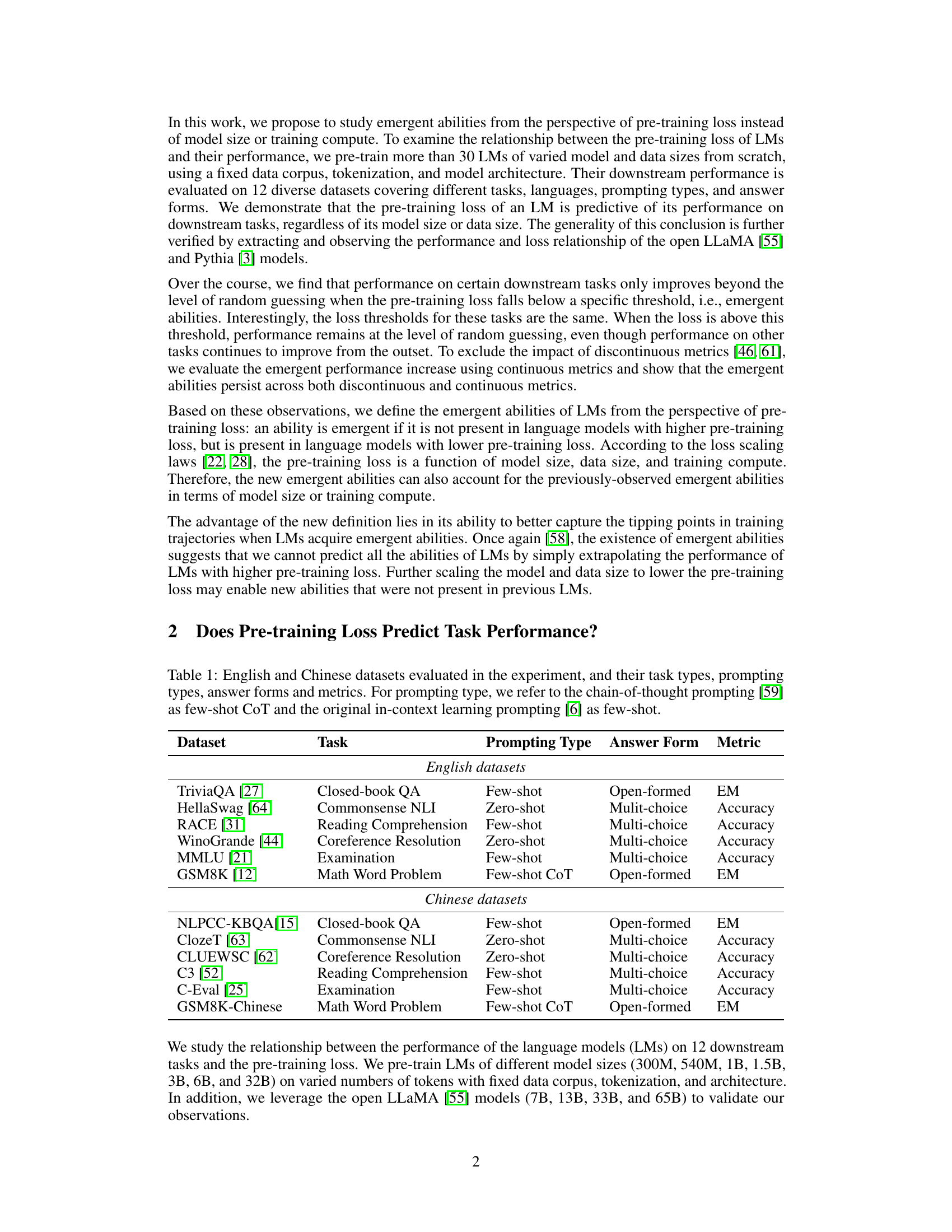

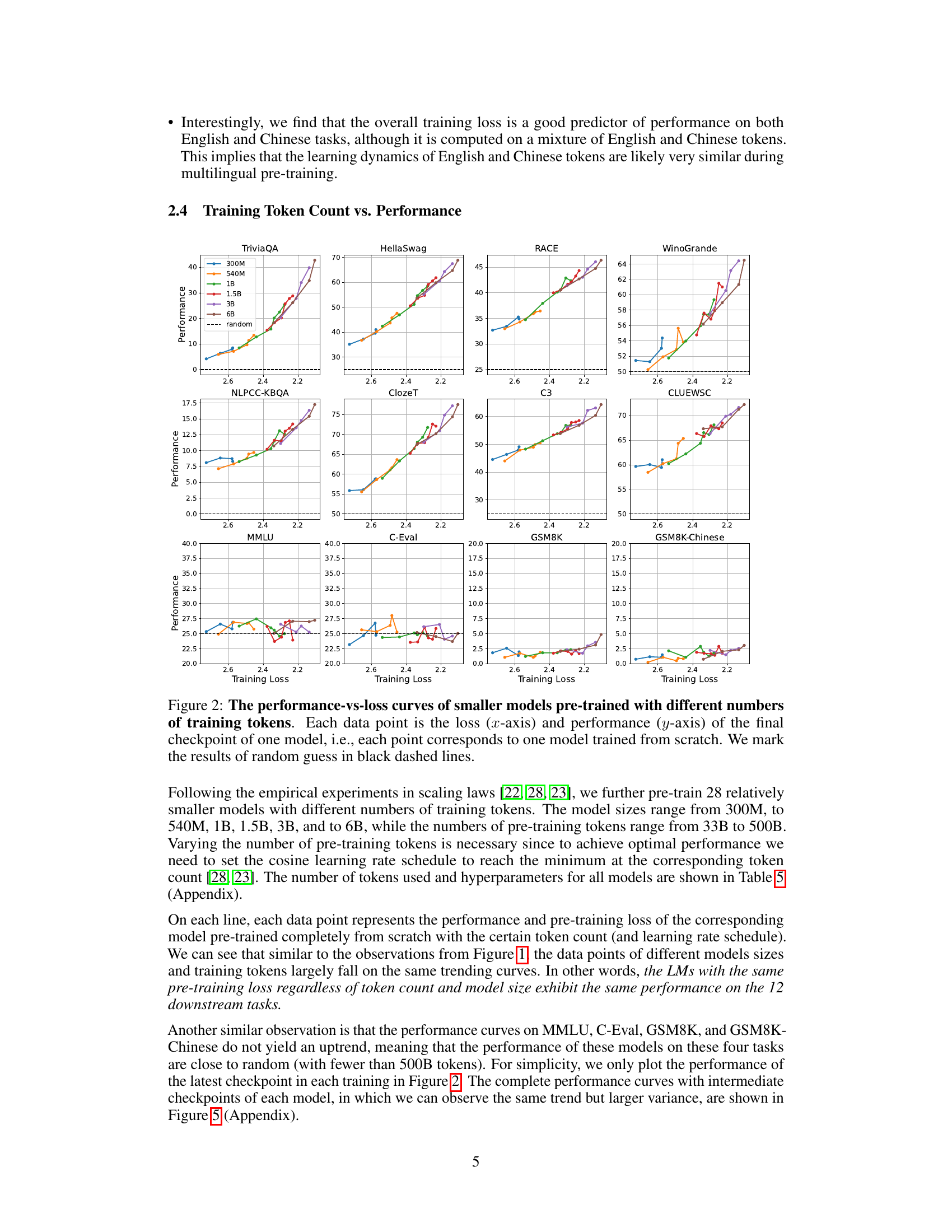

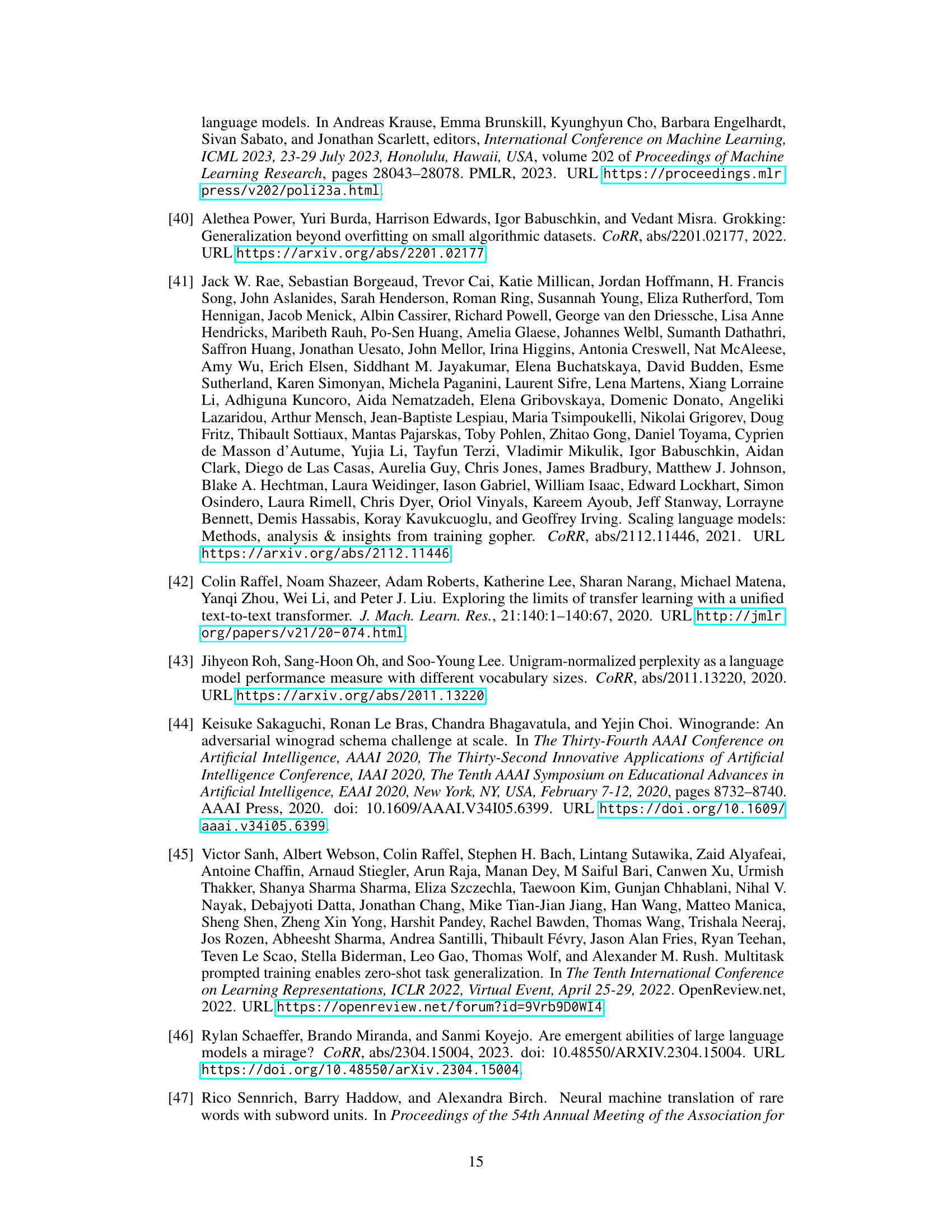

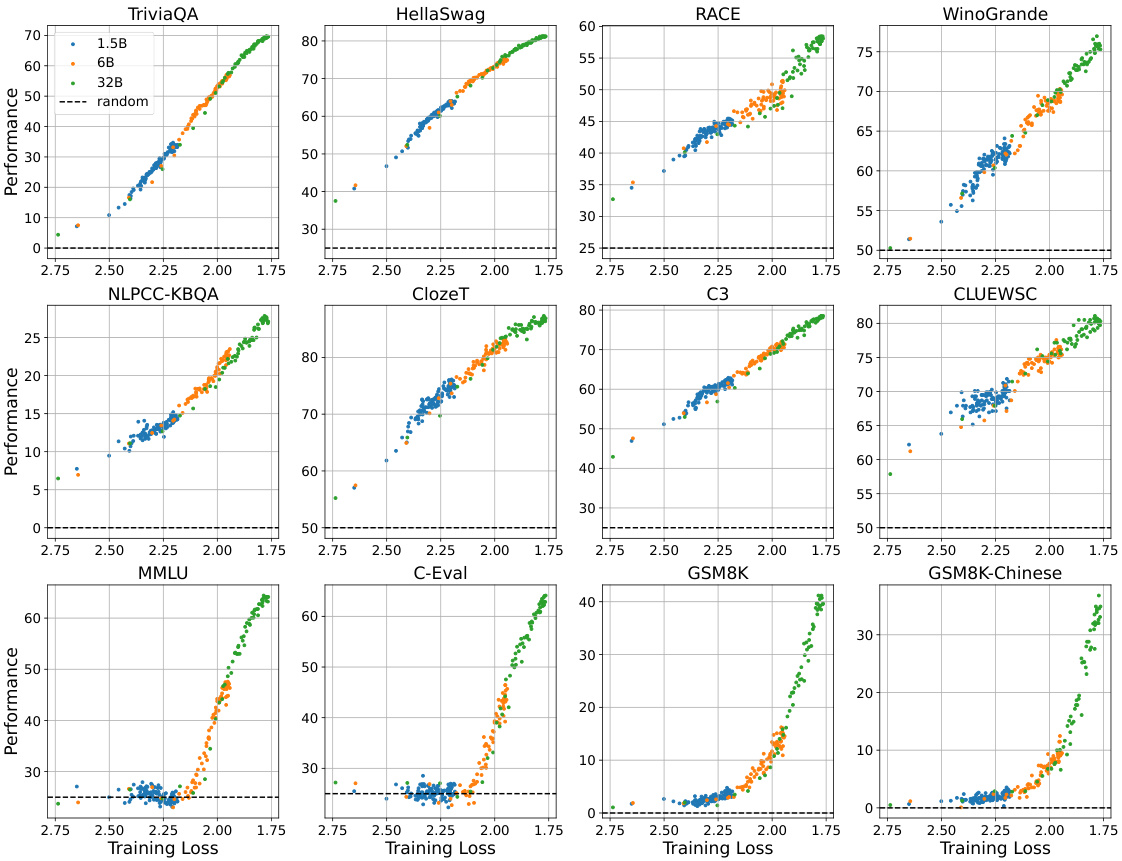

This figure displays the relationship between the pre-training loss and the performance on 12 downstream tasks for three different sized models (1.5B, 6B, and 32B parameters). Each point represents a model checkpoint during training, showing performance on each task as pre-training loss decreases. The dashed lines indicate random performance levels for each task.

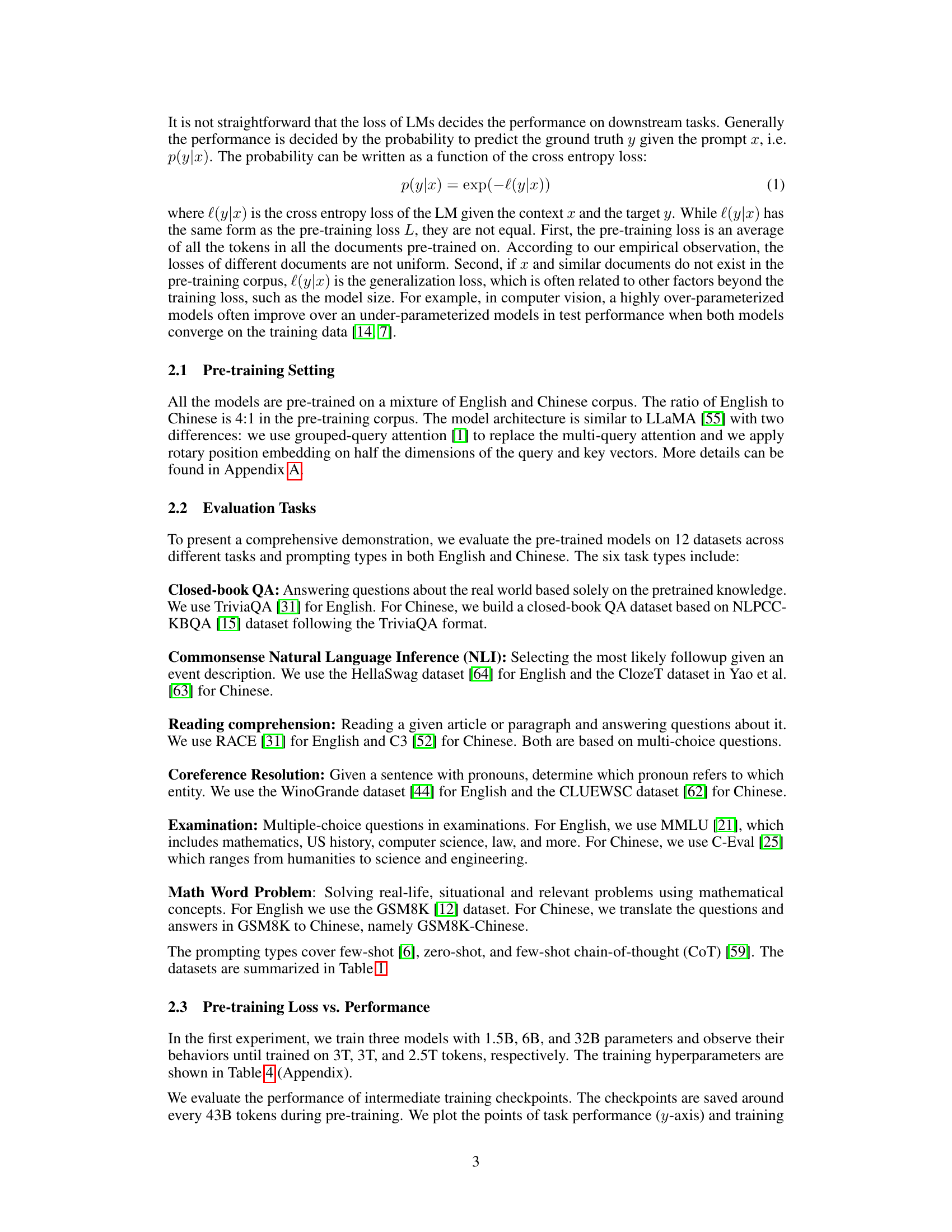

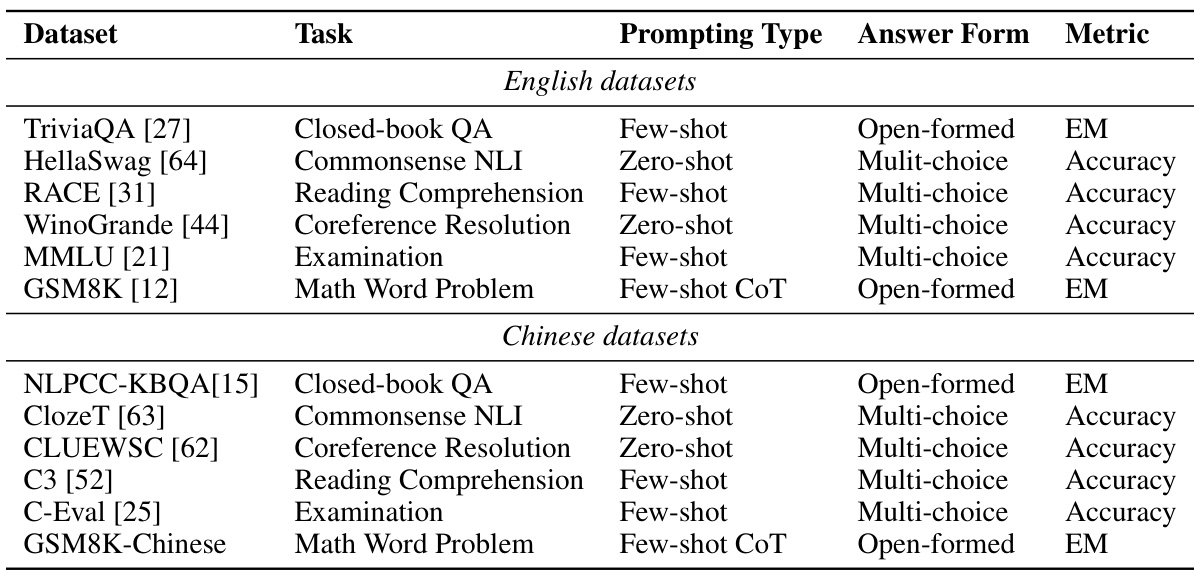

This table lists twelve English and six Chinese datasets used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset, it specifies the task type (e.g., question answering, natural language inference), the prompting type used (zero-shot, few-shot, or few-shot chain-of-thought), the answer format (e.g., open-ended, multiple choice), and the evaluation metric used (e.g., Exact Match, Accuracy). The table provides a comprehensive overview of the diverse tasks and evaluation methods employed in the study.

In-depth insights#

Loss-Based Emergence#

The concept of “Loss-Based Emergence” offers a novel perspective on emergent abilities in large language models (LLMs). Instead of focusing solely on model size or training data, it proposes that emergent abilities arise when the pre-training loss falls below a critical threshold. This shift highlights the importance of the learning process itself, suggesting that sufficient training, regardless of scale, leads to a fundamental change in model capabilities. This framework also helps reconcile conflicting observations—smaller models achieving high performance on tasks previously considered exclusive to large models—by focusing on the underlying learning process and its optimization trajectory. By defining emergence based on a loss threshold, rather than arbitrary metrics or model size, the new definition becomes less susceptible to methodological biases. This allows for a more robust and generalizable understanding of when and how LLMs acquire new abilities. The pre-training loss serves as a more fundamental and direct indicator of model proficiency than metrics which can be impacted by discontinuities or arbitrary choice of evaluation methodology.

LM Scaling Effects#

LM scaling effects explore how changes in model size and training data impact language model performance. Larger models generally show improved performance on various downstream tasks, but this relationship isn’t always linear or consistent across all tasks. Emergent abilities, capabilities only appearing in sufficiently large models, are a key focus. However, recent research challenges this notion, suggesting smaller models, trained well, may achieve comparable or superior performance on some tasks. The pre-training loss, a measure of model learning progress, emerges as a potentially better indicator of performance than sheer size, suggesting that optimizing pre-training loss is crucial, regardless of model size or data size. Further research needs to explore the interplay between different scaling factors, architecture, and the specific tasks to fully understand the complex dynamics of LM scaling.

Metric Influence#

The choice of evaluation metrics significantly influences the observed emergence of abilities in large language models (LLMs). Discontinuous metrics, such as accuracy in multi-choice questions, can obscure gradual improvements and create an artificial appearance of sudden emergence. Continuous metrics, like Brier score or probability of correct answer, provide a more nuanced view, revealing that performance often increases smoothly before reaching a threshold where it becomes significantly better than random guessing. This suggests that apparent discontinuities might be an artifact of the measurement method rather than a fundamental shift in LLM capabilities. Therefore, careful selection and interpretation of metrics are crucial for understanding the development of LLM abilities, and continuous metrics should be prioritized to avoid misinterpreting gradual performance improvements as sudden emergent phenomena.

Emergent Ability#

The concept of “emergent ability” in large language models (LLMs) is a central theme explored in the research paper. The authors challenge the prevailing notion that these abilities are exclusive to massive models, arguing instead that pre-training loss, rather than model size, is the key predictor. They demonstrate that models with the same pre-training loss, regardless of their scale, achieve comparable performance on various downstream tasks. This suggests a threshold of pre-training loss, below which emergent abilities appear, irrespective of model size or the continuity of evaluation metrics. The study thus redefines emergent abilities as a function of pre-training loss and provides a new framework for understanding the acquisition of capabilities in LLMs. This paradigm shift challenges existing scaling laws and offers a more nuanced perspective on how capabilities manifest in LLMs.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore the impact of different pre-training data distributions on emergent abilities, investigating whether a more diverse or specialized dataset influences the threshold loss at which these abilities appear. A deeper investigation into the relationship between specific architectural choices and emergent abilities, moving beyond simply scaling models, is also warranted. This includes exploring novel architectures and analyzing how different attention mechanisms or positional encoding schemes might influence the emergence of specific capabilities. Furthermore, a significant area of future work is to develop more robust and continuous evaluation metrics that accurately capture the subtle nuances of emergent abilities, avoiding the pitfalls of discontinuous metrics. Finally, research should focus on developing techniques to reliably predict the emergence of abilities based on pre-training loss, allowing for a more efficient allocation of computational resources and a more targeted exploration of model capabilities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure displays the relationship between pre-training loss and performance across three different model sizes (1.5B, 6B, and 32B parameters) on twelve downstream tasks. Each point represents a model checkpoint, showing performance on the y-axis and corresponding pre-training loss on the x-axis. The dashed lines indicate the performance expected from random guessing. The figure demonstrates the strong correlation between lower pre-training loss and improved performance across all model sizes.

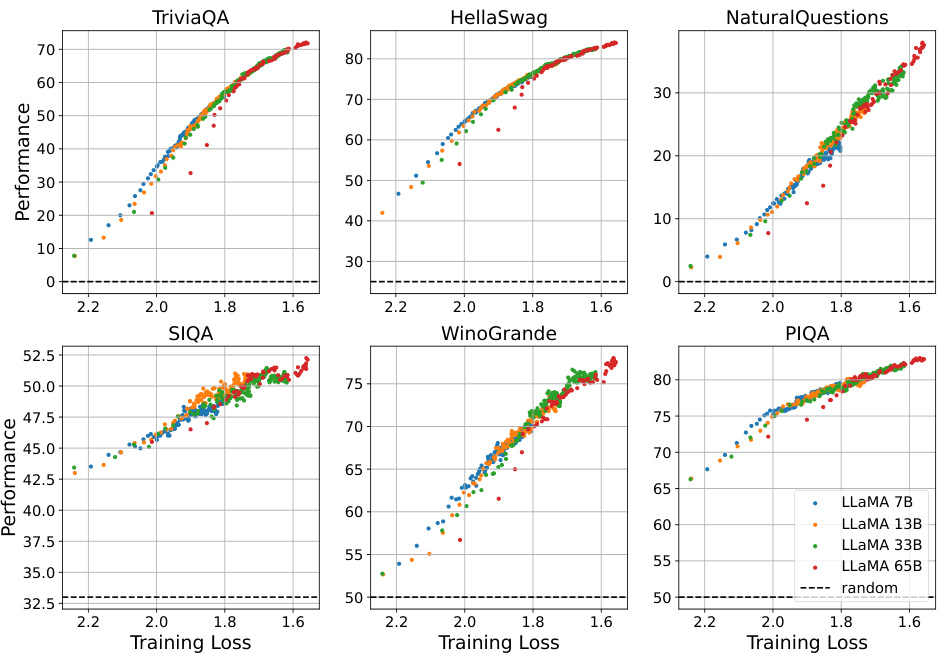

This figure displays the performance versus training loss curves for various LLaMA models. The data points are taken directly from the original LLaMA paper and showcase the relationship between pre-training loss and performance on multiple downstream tasks. The figure helps to validate the authors’ claim that pre-training loss is a good predictor of performance, regardless of model size.

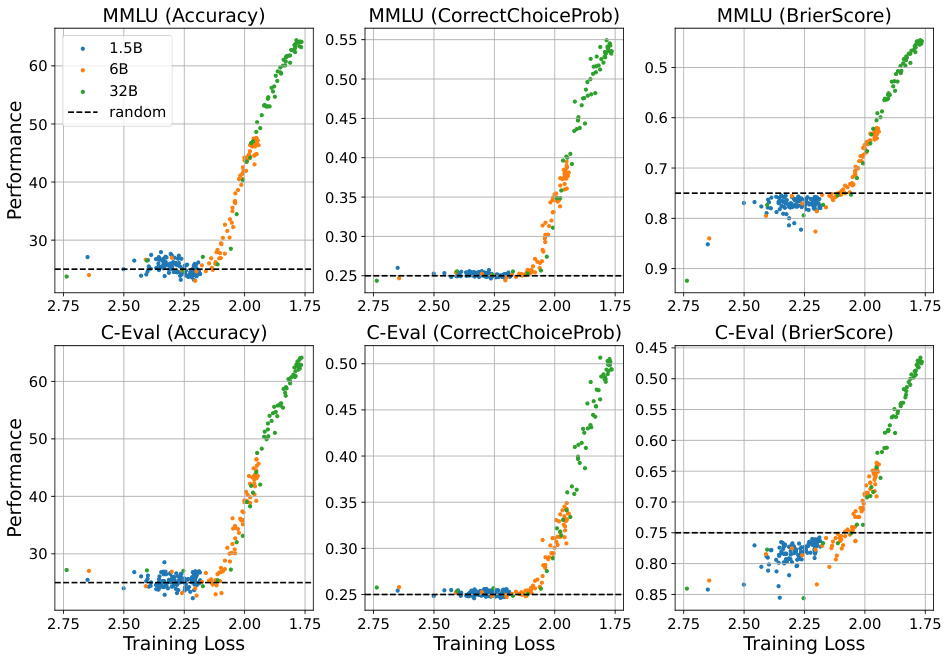

This figure shows the performance versus training loss curves for MMLU and C-Eval using three different metrics: Accuracy, CorrectChoiceProb, and BrierScore. The purpose is to demonstrate that the relationship between pre-training loss and performance persists even when using continuous metrics (CorrectChoiceProb and BrierScore), addressing concerns that the observed emergent abilities are simply an artifact of using discontinuous metrics (Accuracy). The dashed lines indicate the performance level expected from random guessing.

This figure shows the relationship between the pre-training loss and the performance on 12 downstream tasks for three different sized language models (1.5B, 6B, and 32B parameters). Each point represents a checkpoint during training. The plot demonstrates that performance improves as pre-training loss decreases, and that models of different sizes exhibit similar performance trends at the same loss level.

This figure shows the performance (y-axis) versus training compute (x-axis) for language models with 1.5B, 6B, and 32B parameters on 12 downstream tasks. It complements Figure 1, which showed performance against pre-training loss. The purpose is to compare the predictability of model performance using training compute versus pre-training loss, showing pre-training loss is a better predictor. Each point represents a model checkpoint during training.

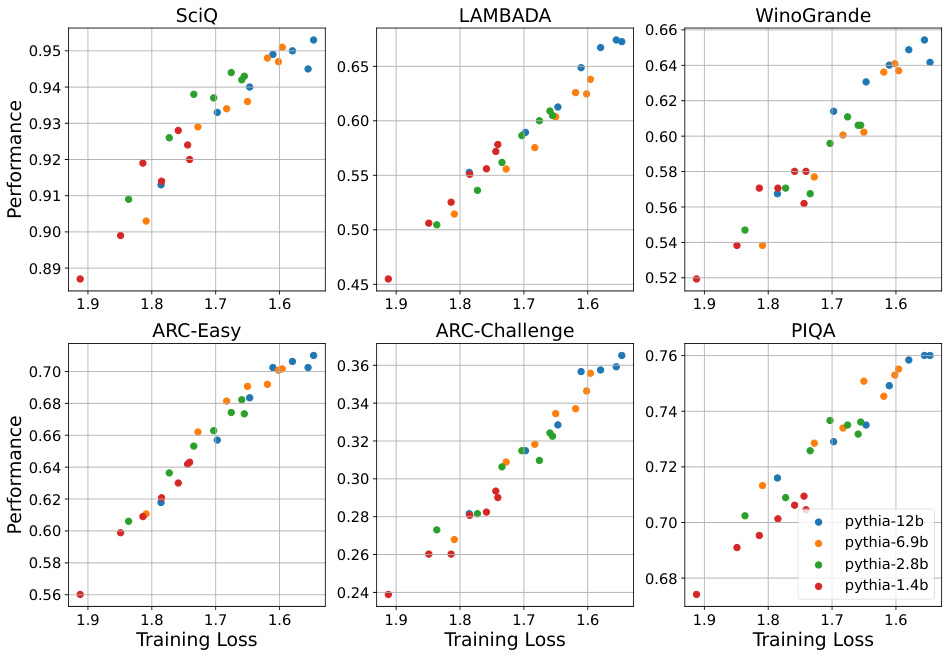

This figure displays the performance-versus-loss curves for different sizes of Pythia language models across six downstream tasks. Each point represents a model checkpoint. The x-axis shows the training loss, and the y-axis represents the model’s performance. This figure supports the paper’s claim that pre-training loss is a good predictor of model performance, irrespective of model size.

This figure displays the performance against pre-training loss curves for three different sized models (1.5B, 6B, and 32B parameters) across three BIG-bench tasks: word unscramble, modular arithmetic, and IPA transliteration. Each point represents an intermediate checkpoint during training. The black dashed line indicates the performance level of random guessing. The figure demonstrates the relationship between pre-training loss and model performance on these tasks, highlighting the point at which performance moves beyond random chance.

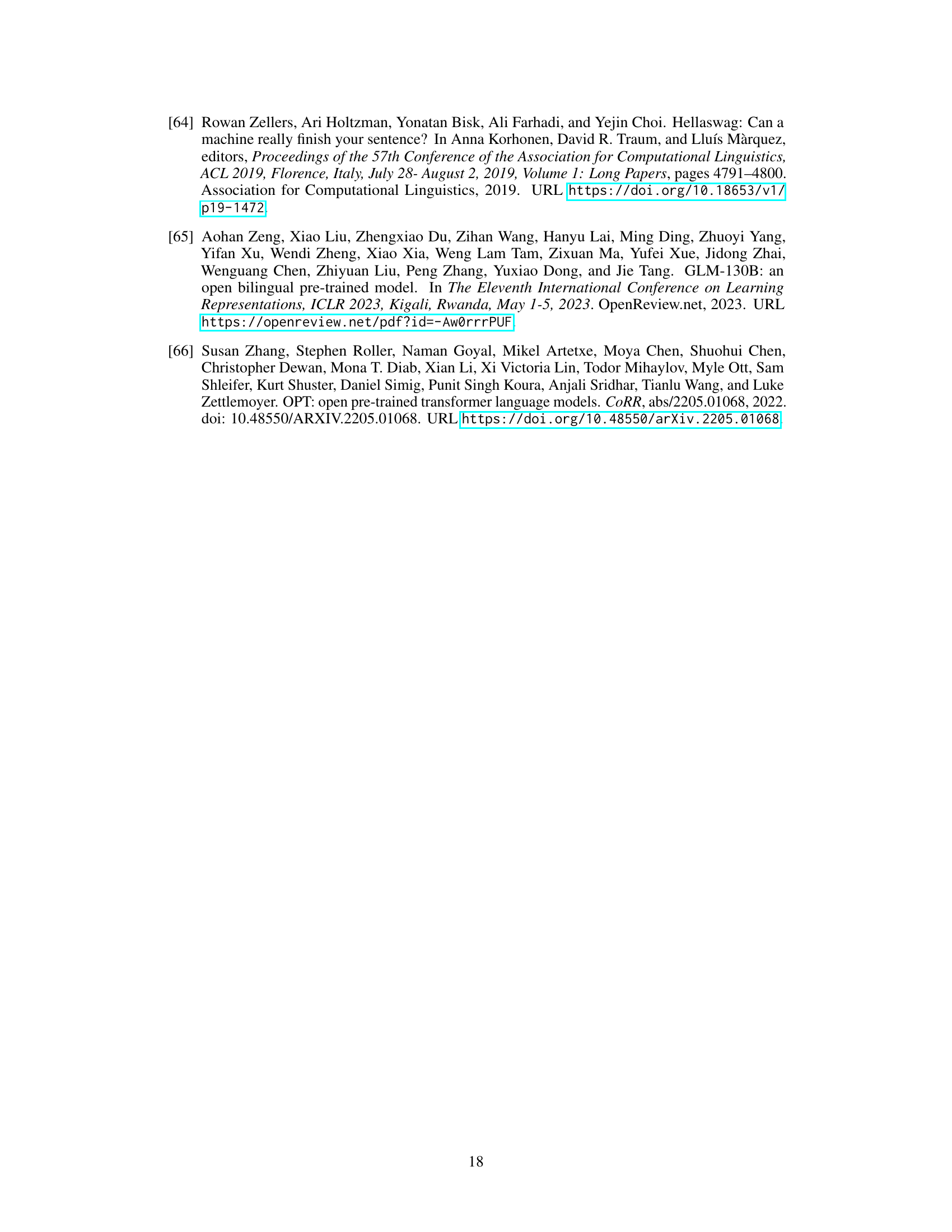

More on tables

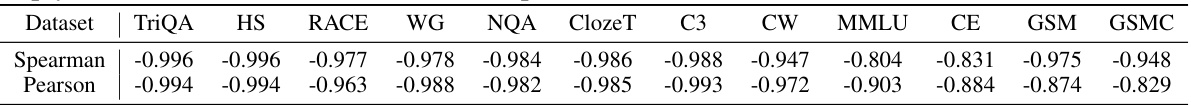

This table presents the statistical correlation (Spearman and Pearson) between pre-training loss and the performance of 12 downstream tasks. It shows the strength and type of relationship between the pre-training loss and performance across diverse tasks.

This table lists twelve English and six Chinese datasets used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset, it specifies the task type (e.g., question answering, natural language inference), the prompting type used (zero-shot, few-shot, few-shot chain-of-thought), the answer format (open-formed, multiple-choice), and the evaluation metric (exact match, accuracy). The table shows the diversity of tasks and languages used to evaluate the relationship between pre-training loss and model performance.

This table lists twelve English and Chinese datasets used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset, it specifies the type of task (e.g., question answering, natural language inference), the prompting type used (zero-shot, few-shot, few-shot chain-of-thought), the answer form (open-ended, multiple-choice), and the evaluation metric (exact match, accuracy). The table provides a comprehensive overview of the diverse tasks and evaluation methods employed in the study.

This table lists twelve English and Chinese datasets used in the paper’s experiments to evaluate the performance of language models. For each dataset, it provides the task type (e.g., question answering, natural language inference), the prompting type used (zero-shot, few-shot, few-shot chain-of-thought), the answer format (e.g., open-ended, multiple-choice), and the evaluation metric (e.g., exact match, accuracy). The table helps to illustrate the diversity of tasks and evaluation methods used in the study.

This table lists twelve English and Chinese datasets used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset, it specifies the type of task (e.g., question answering, natural language inference), the prompting type used (zero-shot, few-shot, few-shot chain-of-thought), the format of the answers (open-formed, multiple-choice), and the evaluation metric used (Exact Match, Accuracy). The table provides a comprehensive overview of the diverse range of tasks and evaluation methods employed in the study.

Full paper#