↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Transformer models, while powerful, demand significant computational resources. A common strategy to mitigate this involves converting parts of the network into Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) layers, leveraging activation sparsity. However, current approaches do not fully exploit this sparsity and their efficiency is limited. This paper tackles these issues.

The paper introduces D2DMoE, a novel method that enhances activation sparsity before conversion, employs a more effective router training scheme, and introduces a dynamic-k expert selection rule. D2DMoE outperforms existing approaches, reducing inference costs by up to 60% without significant performance loss. It is also generalized beyond feed-forward networks to multi-head attention projections, improving its overall applicability and efficacy.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it offers a novel approach to reduce the computational cost of transformer models, a critical issue in deploying large models. The proposed D2DMoE method significantly enhances the efficiency of converting dense transformer layers into sparse Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) layers, opening up avenues for optimizing existing models and designing new, more efficient architectures. Its efficient GPU implementation further broadens its appeal and practical applicability.

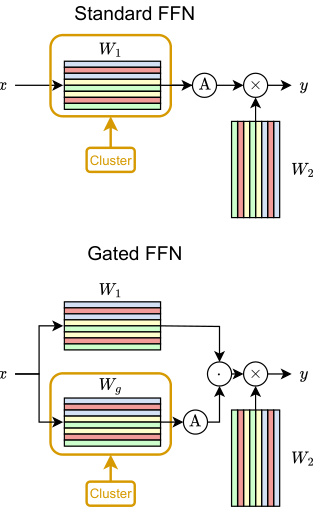

Visual Insights#

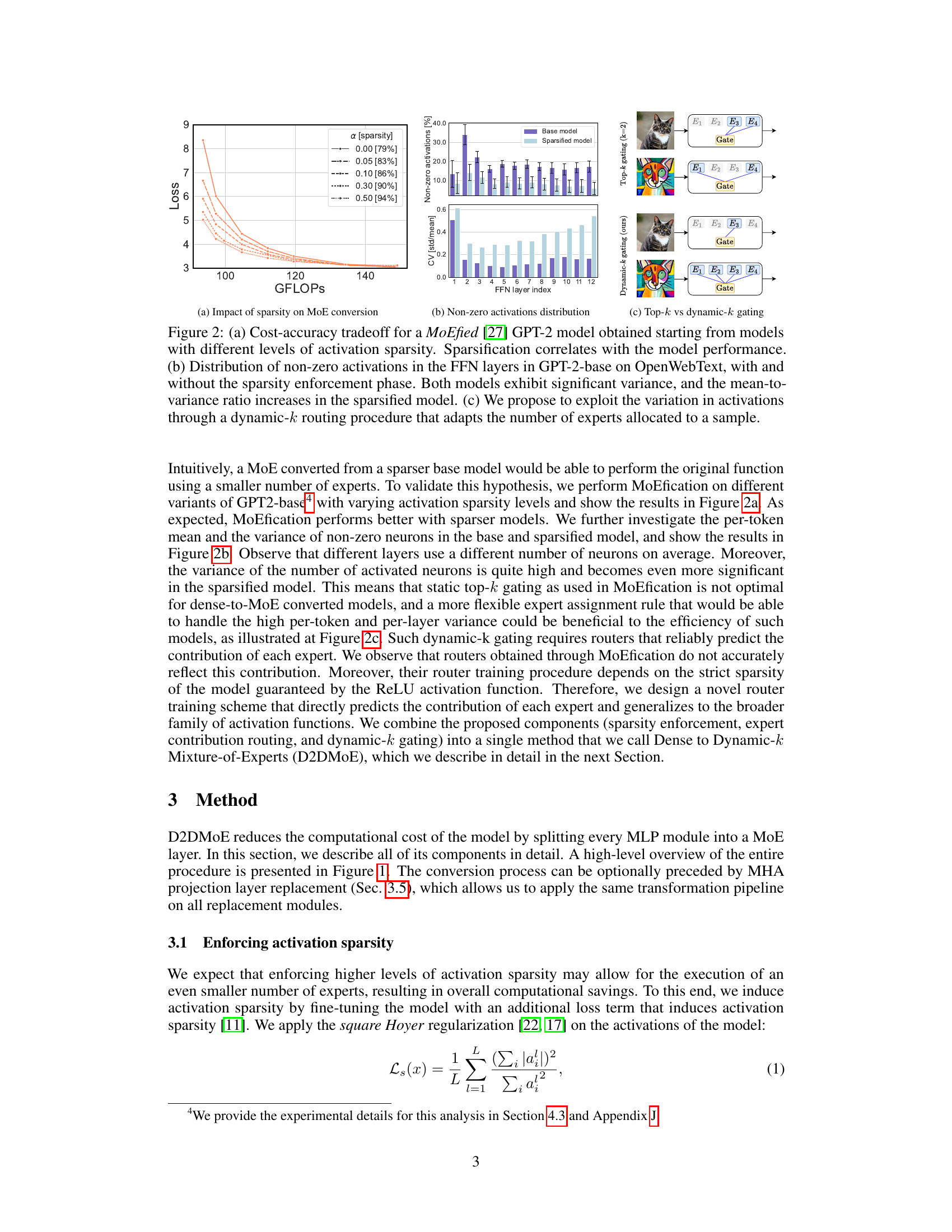

This figure illustrates the three main components of the Dense to Dynamic-k Mixture-of-Experts (D2DMoE) method. (a) shows how the activation sparsity is enhanced in the base model before conversion. (b) depicts the conversion of feed-forward network (FFN) layers into Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) layers, highlighting the role of routers in predicting expert contribution. (c) illustrates the dynamic-k expert selection, a key improvement that adapts the number of experts used per token.

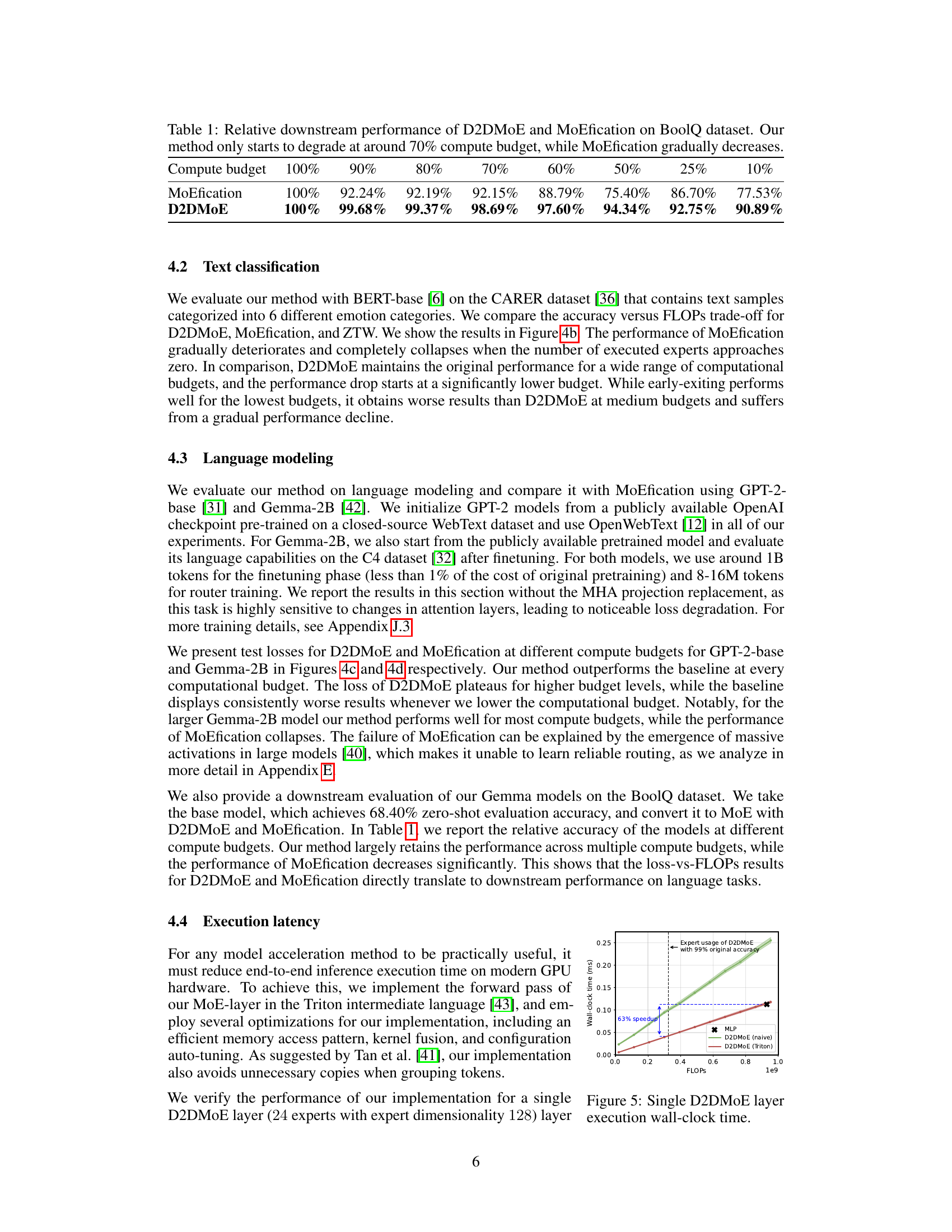

This table shows the relative downstream performance of D2DMoE and MoEfication on the BoolQ dataset at various compute budgets (100%, 90%, 80%, 70%, 60%, 50%, 25%, 10%). It highlights that D2DMoE maintains high performance even at significantly reduced compute budgets (down to 70%), whereas MoEfication’s performance degrades more substantially as the compute budget decreases.

In-depth insights#

Sparse MoE Conversion#

Sparse Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) conversion is a crucial technique for optimizing large transformer models. It aims to reduce computational costs by leveraging the inherent sparsity of activations in these models. The process involves identifying less crucial parts of the network, and replacing them with equivalent MoE layers. These layers only activate a subset of their expert networks for any given input, thereby dramatically decreasing the number of computations. However, the efficiency of this conversion heavily depends on several factors, including the pre-existing activation sparsity of the model, and the training scheme of the routing network that selects which experts to activate. Improving activation sparsity before conversion is critical and can greatly enhance efficiency, and a well-designed routing mechanism is essential for optimal cost-performance trade-offs. Dynamic routing techniques that adjust the number of active experts per input token can further improve efficiency. Careful consideration of these aspects is vital for a successful sparse MoE conversion, enabling the development of significantly more efficient and resource-friendly large models.

Dynamic-k Routing#

Dynamic-k routing is a significant advancement in Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models, addressing the limitations of traditional top-k routing. Instead of a fixed number of experts per input, dynamic-k routing adaptively selects the number of experts based on the input’s complexity. This approach is particularly beneficial for Transformer models exhibiting high variance in activation sparsity across different inputs. By dynamically allocating computational resources, dynamic-k routing improves efficiency without significantly sacrificing performance. This is achieved by using a router that predicts the contribution of each expert, allowing the model to prioritize those most relevant to a given input. The dynamic adjustment ensures that easy inputs require less computation, while difficult inputs receive the necessary resources, leading to improved overall efficiency and a better cost-performance tradeoff. Its effectiveness is demonstrated across various NLP and vision tasks, showing its potential to optimize inference in resource-constrained environments.

MHA Projection MoE#

The concept of “MHA Projection MoE” suggests a significant advancement in efficient Transformer model design. By applying Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) to the projection layers of Multi-Head Attention (MHA), a substantial portion of the computation can be selectively activated, leading to reduced inference costs. This approach tackles the high computational demands of Transformers head-on, by selectively engaging experts based on input significance. This is likely more efficient than applying MoE only to feed-forward networks, as MHA often consumes a larger proportion of the computational budget. The method’s effectiveness depends on the ability of a gating mechanism to accurately predict which experts are crucial for a given input, therefore the design and training of this gating network are critical for success. Careful consideration must be given to the trade-off between accuracy and sparsity. The variance in the number of activated neurons for different inputs must also be addressed for optimal performance. A dynamic k-selection mechanism could be essential to adapt the computation budget on a per-token or per-layer basis, further enhancing efficiency.

Efficient Implementation#

The heading ‘Efficient Implementation’ suggests a focus on optimizing the proposed method’s practical application. A thoughtful analysis would delve into specifics: What optimizations were employed? Did they leverage specialized hardware (like GPUs or TPUs)? Were algorithmic improvements made to reduce computational complexity? Were software engineering techniques used, such as parallel processing or memory management optimizations? The discussion should highlight the techniques employed and their impact, potentially through metrics like speedup or reduction in memory footprint. Crucially, a comparison to existing methods’ implementations would demonstrate the novelty and effectiveness of the proposed optimizations. Were there any trade-offs? For example, did the pursuit of speed sacrifice accuracy or memory usage? A strong ‘Efficient Implementation’ section should provide concrete evidence that the proposed method is not only theoretically sound but also practically viable and competitive.

Ablation & Analysis#

An ablation study systematically evaluates the contribution of each component within a proposed model. By incrementally removing or altering individual parts, researchers isolate their effects and assess the overall impact on performance. This process helps establish the necessity and relative importance of different model elements. A thorough analysis might extend beyond simple performance metrics, delving into the qualitative aspects of model behavior under various ablated conditions. For example, examining changes in activation patterns or feature representations reveals how different components interact. This combination of quantitative and qualitative analysis provides a more complete understanding of the model’s inner workings. The results of the ablation study, combined with insightful analysis, are crucial in justifying design choices and clarifying the mechanism of a model’s success. Careful consideration of limitations and potential confounding factors during the ablation process is important for the trustworthiness of results and conclusions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

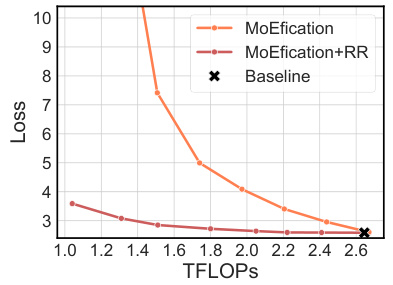

This figure demonstrates the impact of activation sparsity on MoE conversion, showing a cost-accuracy tradeoff. It displays that higher activation sparsity improves the efficiency of MoE conversion and that a dynamic-k expert selection method, which adapts the number of experts used per sample, significantly enhances efficiency compared to a static top-k method. The distribution of non-zero activations shows significant variance, suggesting that a dynamic approach is beneficial.

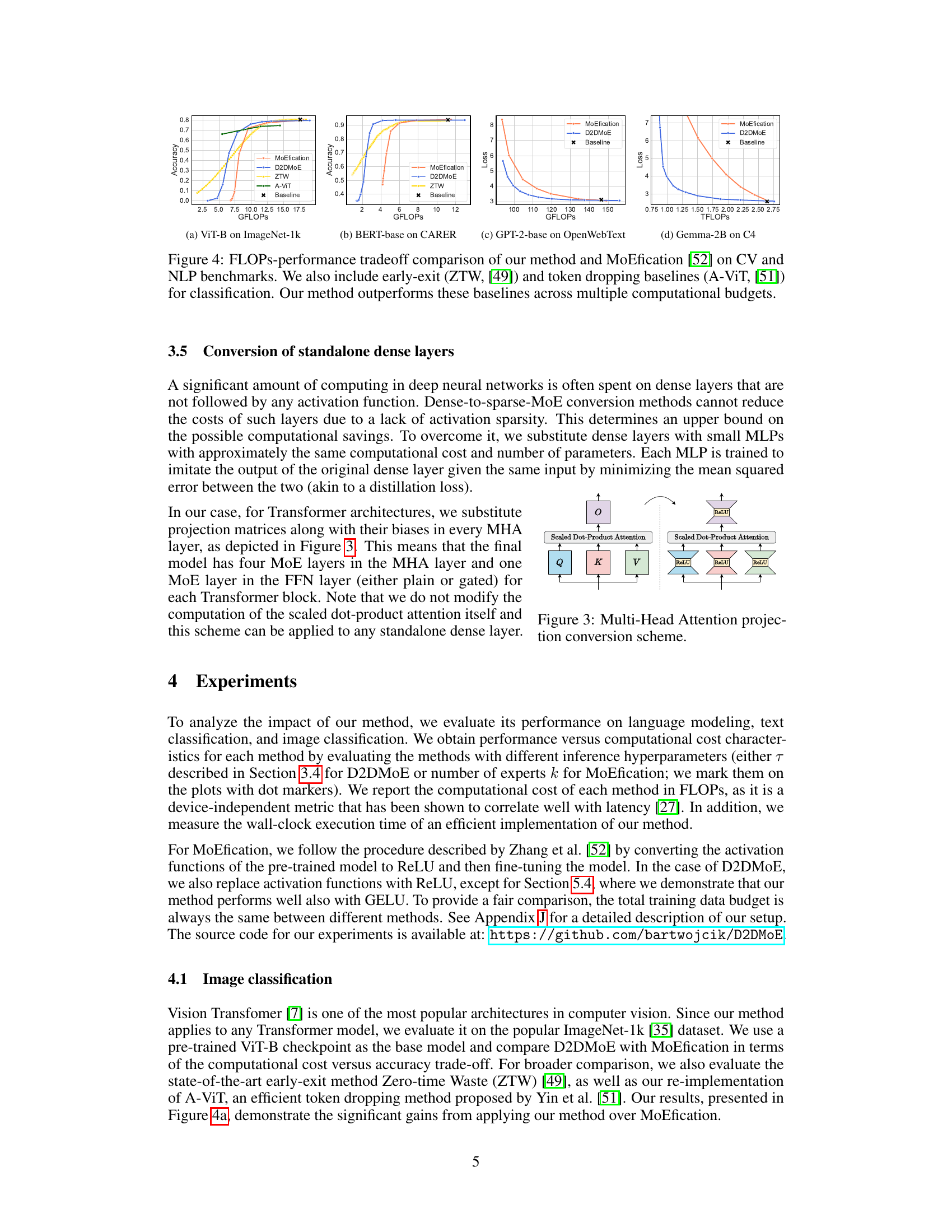

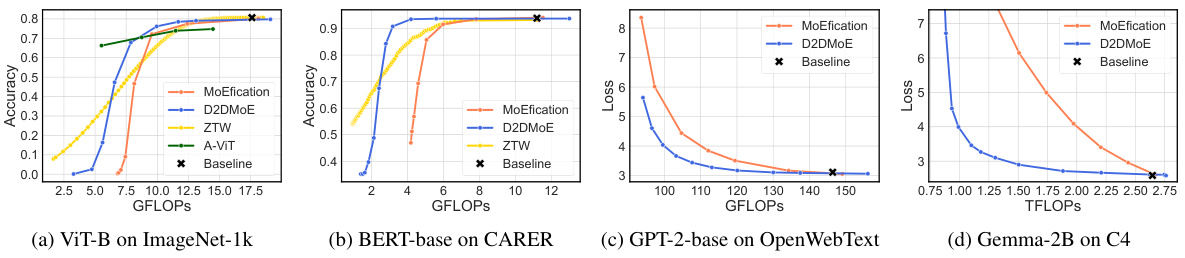

This figure presents the cost-performance tradeoffs of different model compression and acceleration methods applied to four different tasks. The x-axis represents the computational cost in GFLOPS (or TFLOPS for Gemma-2B), and the y-axis represents the accuracy or loss. Four different methods are compared: MoEfication (a baseline method), D2DMoE (the proposed method), ZTW (a zero-time waste early-exit method), and A-ViT (an adaptive token dropping method). The results show that D2DMoE consistently outperforms other methods across a wide range of computational budgets for all four tasks. This demonstrates the efficiency of D2DMoE in achieving high performance while significantly reducing inference cost.

This figure illustrates the three main steps of the D2DMoE method: First, activation sparsity is enhanced in the base model. Then, feed-forward network (FFN) layers are transformed into Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) layers, using routers that estimate the contribution of each expert. Finally, dynamic-k routing is applied to select which experts to activate on a per-token basis.

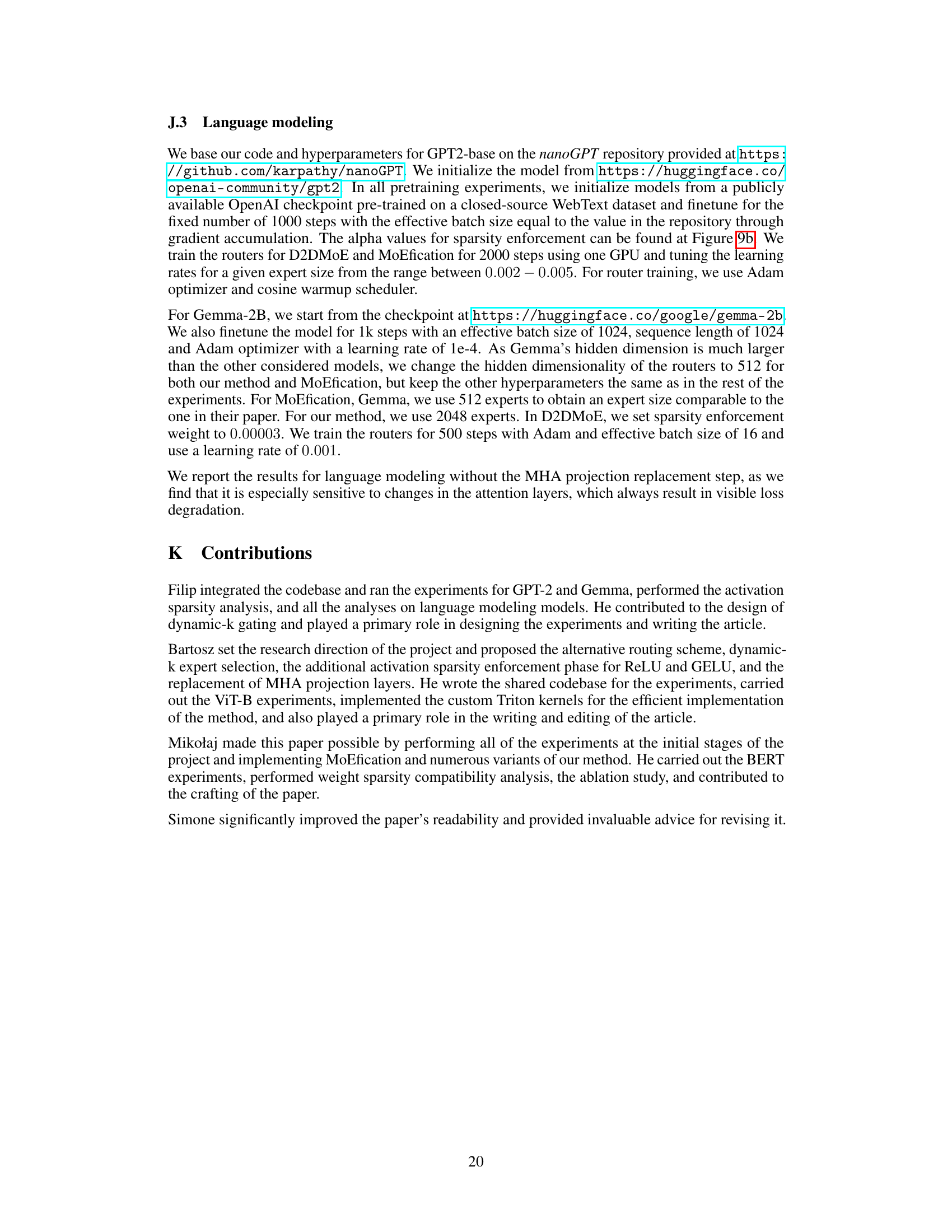

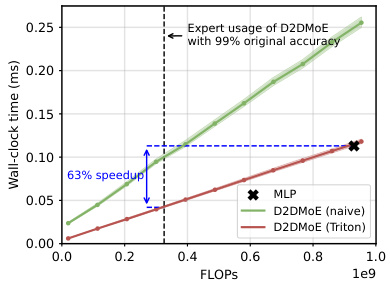

This figure compares the execution time of a single D2DMoE layer against a standard MLP layer on an NVIDIA A100 GPU. The x-axis represents the number of FLOPs (floating point operations), and the y-axis represents the wall-clock time in milliseconds. The figure shows that D2DMoE, especially when using the optimized Triton implementation, significantly reduces the wall-clock time compared to the standard MLP, achieving a 63% speedup at a point where D2DMoE maintains 99% of the original accuracy. The plot demonstrates the efficiency gains of D2DMoE in terms of inference speed.

This figure shows the results of applying the D2DMoE method on top of models that have been pruned using the CoFi method. Different sparsity levels (s) are tested, showing that D2DMoE continues to provide acceleration even when using highly pruned models. The x-axis represents the GFLOPs and the y-axis represents the accuracy. The figure demonstrates the complementarity of D2DMoE and CoFi in achieving both reduced computational cost and maintained performance.

This figure shows the comparison results of the proposed method, D2DMoE, and other methods (MoEfication, ZTW, A-ViT) on various tasks (image classification, text classification, language modeling) with different computational budgets. The x-axis represents the computational cost (GFLOPS or TFLOPS), and the y-axis represents the accuracy or loss. The figure demonstrates that D2DMoE achieves a better cost-performance trade-off compared to existing approaches, maintaining high accuracy even with significantly reduced computational costs.

This figure shows two aspects of the D2DMoE model’s dynamic computation allocation. The left panel (a) displays histograms showing the distribution of the number of experts used per layer for both a standard and a sparsified model on the CARER dataset. It highlights how sparsification significantly reduces the number of experts needed. The right panel (b) presents computational load maps for several ImageNet-1k images processed by a converted ViT-B model. The heatmaps illustrate how the model focuses computational resources on semantically important areas of the images.

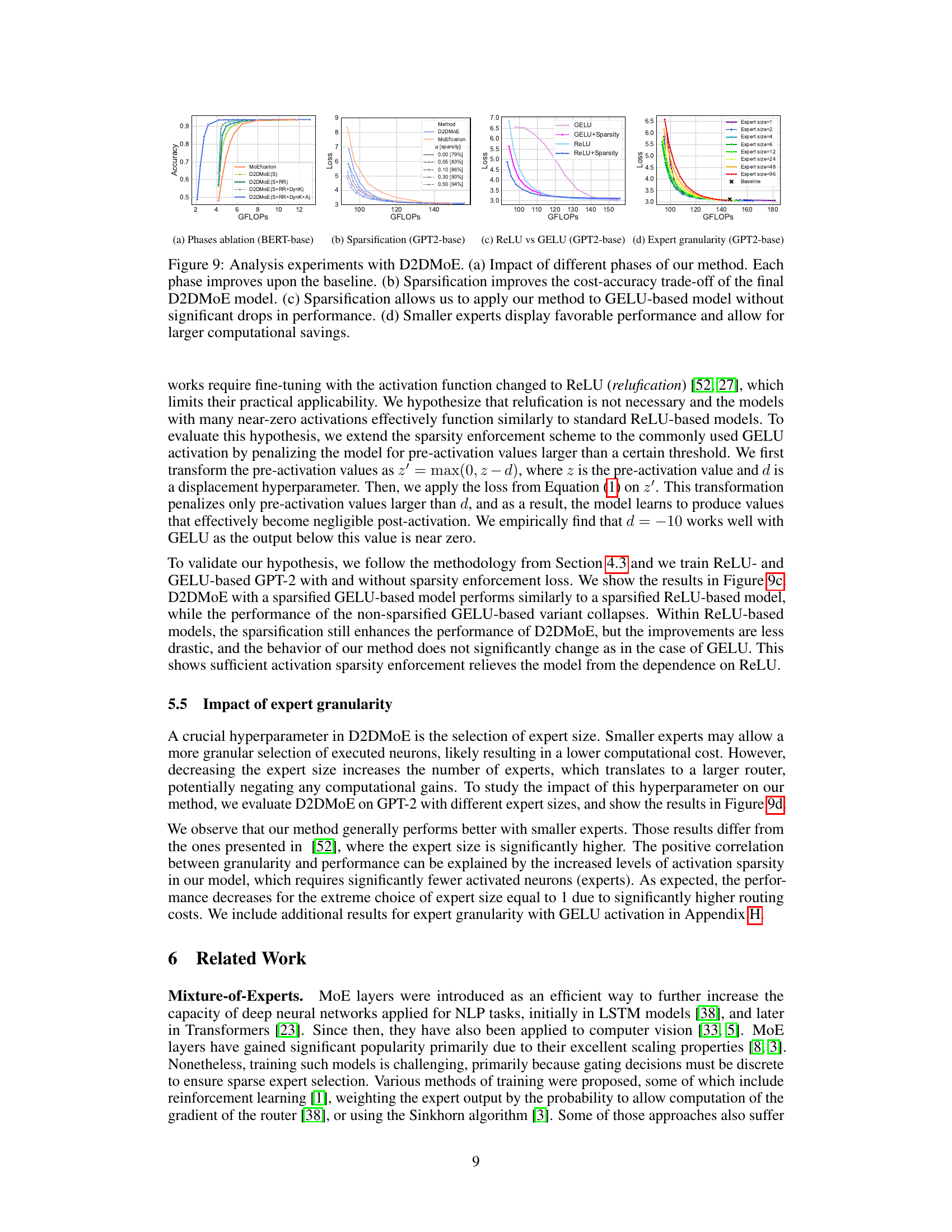

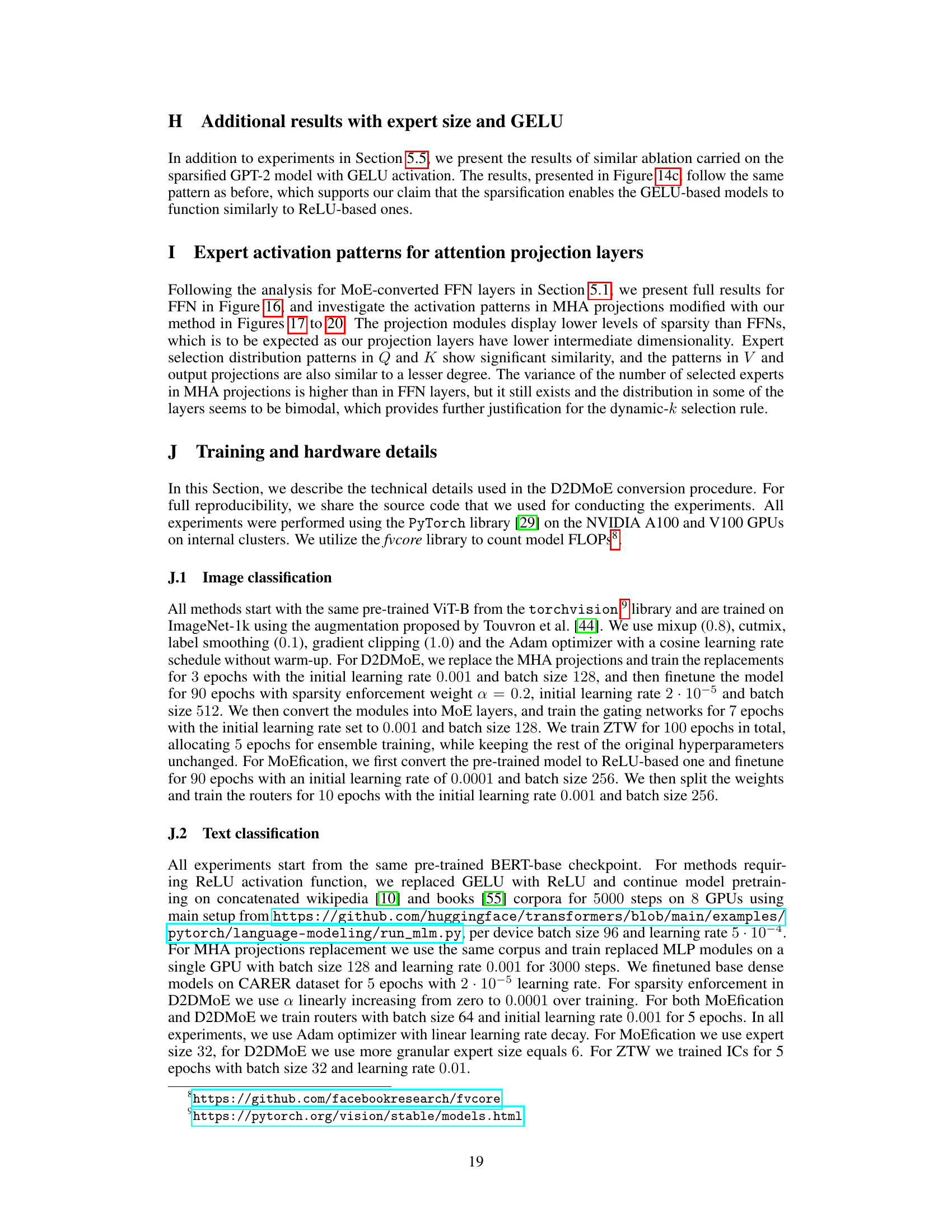

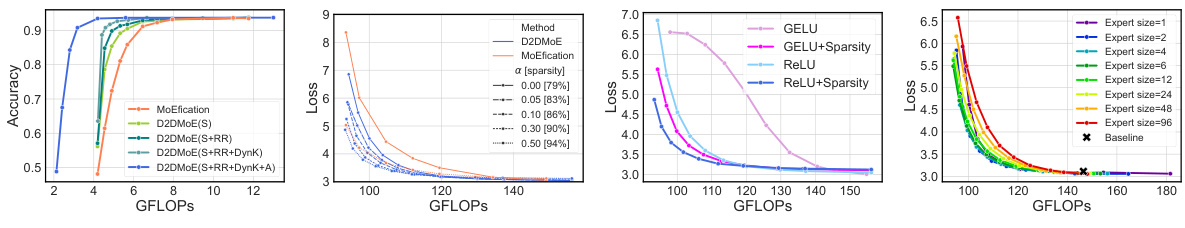

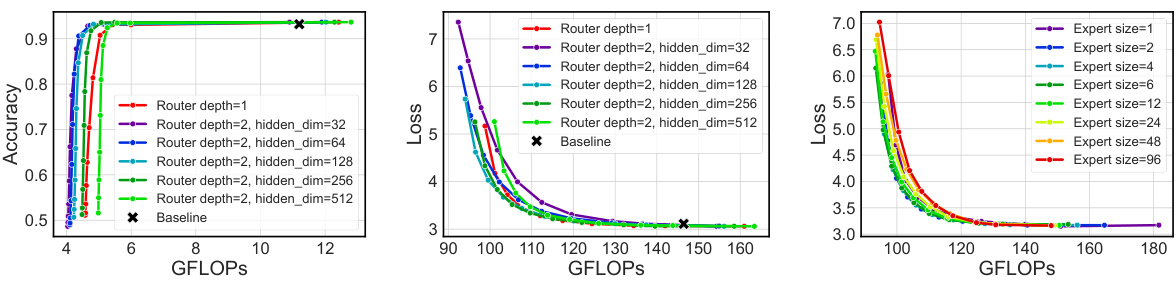

This figure presents the results of ablation studies and other experiments conducted to analyze the impact of different components of the proposed D2DMoE method. Panel (a) shows the impact of each phase (sparsification, regression routing, dynamic-k, and attention projection replacement) on a BERT-base model. Panel (b) shows the correlation between activation sparsity of the base model and performance of the resulting MoE model for GPT-2-base. Panel (c) compares the performance using ReLU and GELU activation functions for GPT-2-base models. Panel (d) analyzes the effect of different expert sizes on the performance and computational cost for GPT2-base.

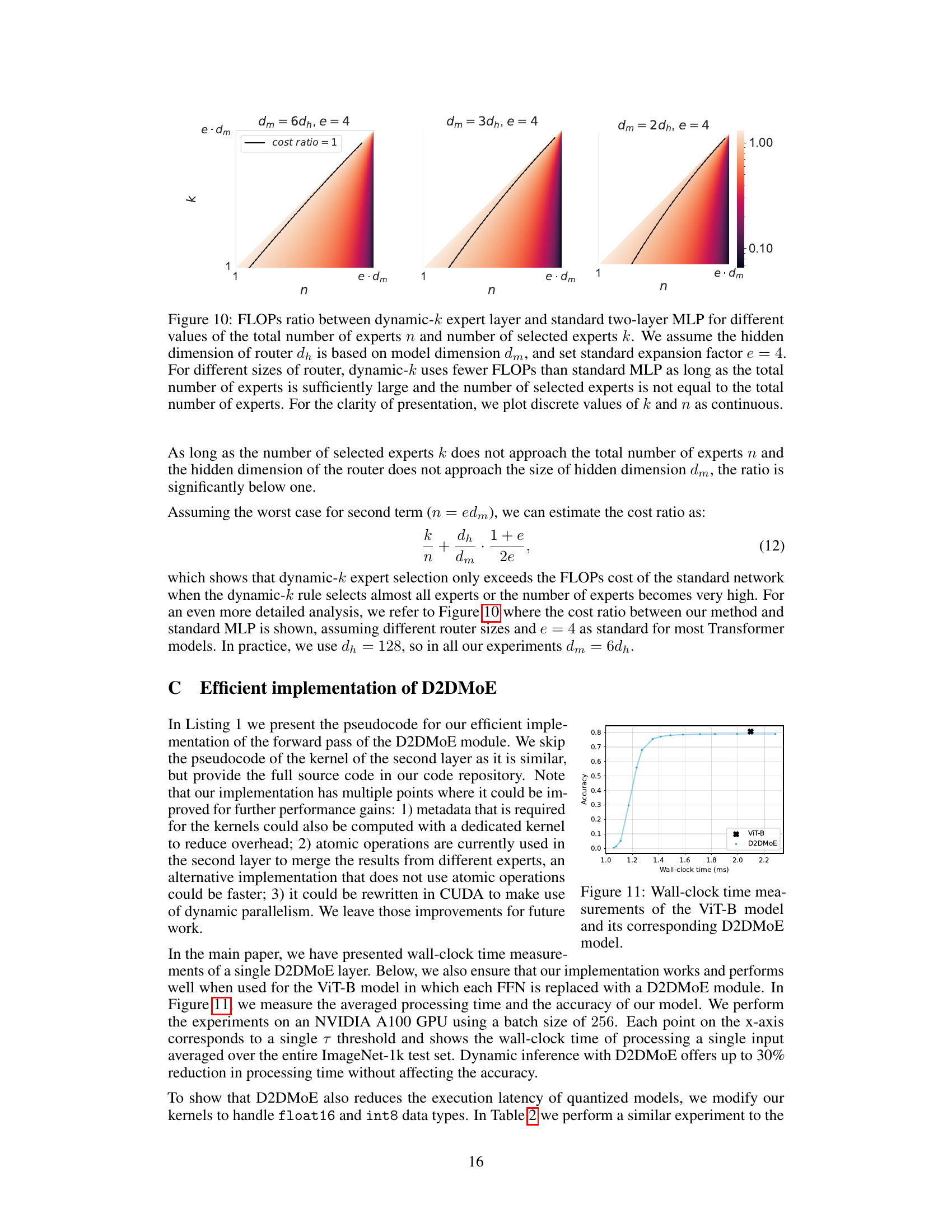

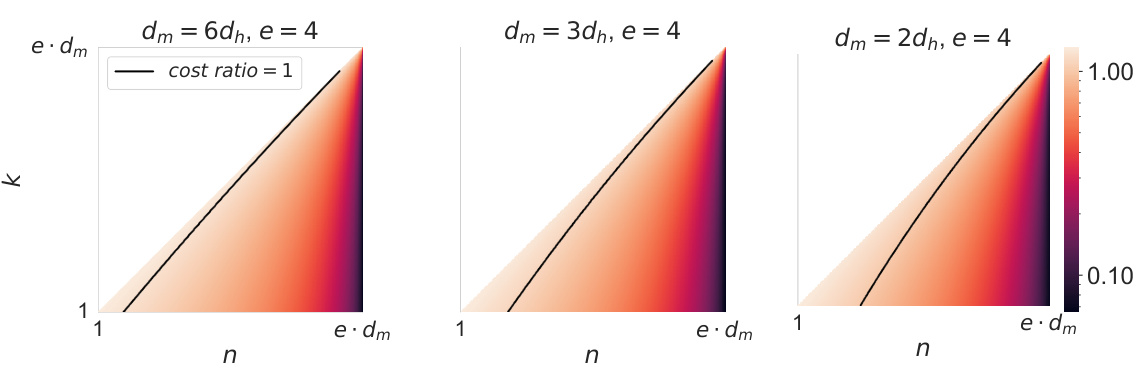

This figure shows the FLOPs ratio between a dynamic-k expert layer and a standard two-layer MLP. It illustrates how the dynamic-k approach, by selecting fewer experts (k) out of the total (n), can significantly reduce computational cost compared to a standard MLP, especially when the total number of experts is sufficiently large and not all experts are used.

This figure shows the wall-clock time of a single D2DMoE layer with 24 experts and an expert dimensionality of 128, measured on an NVIDIA A100 GPU. The x-axis represents the FLOPS (floating point operations per second), and the y-axis shows the wall-clock time in milliseconds. The plot demonstrates that the execution time scales linearly with the number of executed experts, indicating that D2DMoE’s efficient implementation has negligible overhead. The figure also displays a comparison with a standard MLP (Multilayer Perceptron) module, illustrating that D2DMoE achieves a speedup of up to 3 times while maintaining 99% of the original accuracy.

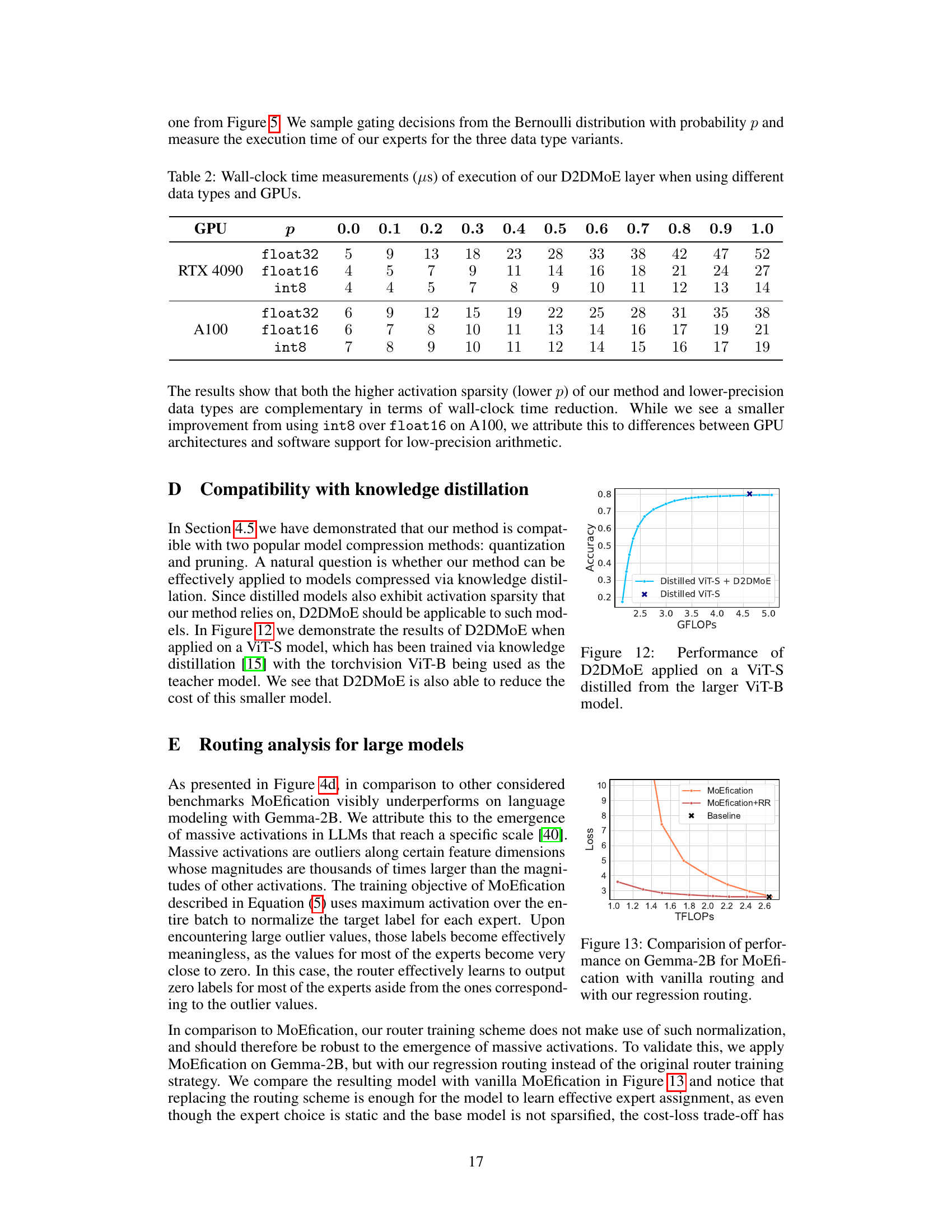

This figure shows the performance of D2DMoE when applied to a Vision Transformer (ViT) model that has been trained via knowledge distillation using a larger ViT model as the teacher. The x-axis represents the computational cost (GFLOPs), while the y-axis shows the accuracy. The plot demonstrates that D2DMoE is effective at reducing the computational cost of even a distilled model, while maintaining a high level of accuracy.

This figure shows the cost-performance trade-off for various model compression techniques on different computer vision (CV) and natural language processing (NLP) benchmarks. It compares the proposed D2DMoE method against MoEfication, an early-exit baseline (ZTW), and a token-dropping baseline (A-ViT). The x-axis represents the computational cost in FLOPs (floating-point operations per second), while the y-axis represents either accuracy or loss, depending on the specific benchmark. The results demonstrate that D2DMoE consistently achieves superior performance across various computational budgets compared to the other methods.

This figure presents the ablation study of the proposed D2DMoE method, showing the impact of each component on the performance, and compares the performance of models with different activation functions (ReLU and GELU) and expert granularities. The results demonstrate that each component contributes to performance improvement, and that D2DMoE achieves better cost-accuracy trade-off compared to the baseline, especially with smaller experts.

This figure illustrates the three main components of the Dense to Dynamic-k Mixture-of-Experts (D2DMoE) method. (a) shows how the activation sparsity of the original dense model is improved. (b) demonstrates the conversion of Feed-Forward Networks (FFN) layers into Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) layers, highlighting the role of routers in predicting expert contribution. Finally, (c) details the dynamic-k routing mechanism which adaptively selects the number of experts to execute per token, enhancing efficiency.

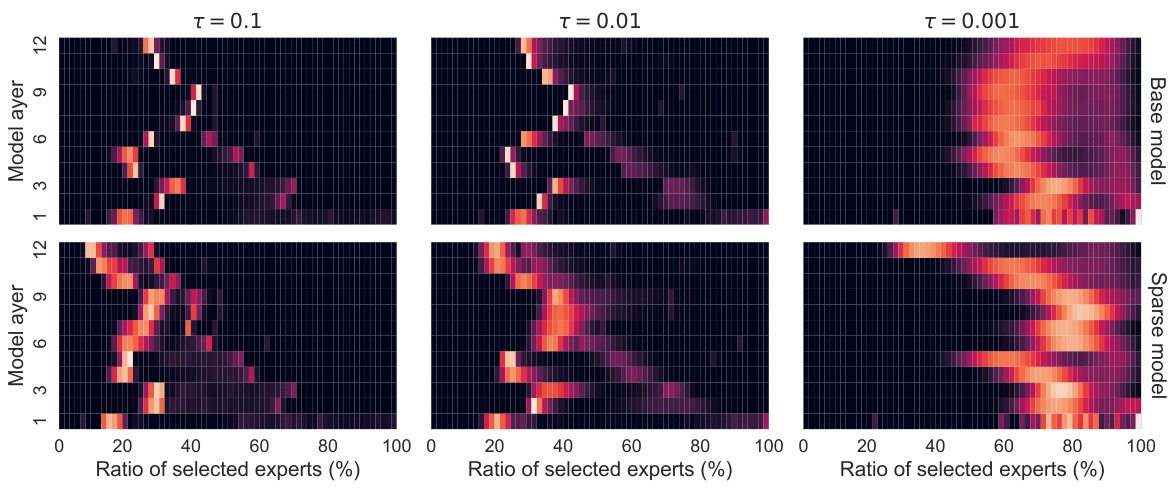

This figure shows the distribution of the number of experts executed per layer for different threshold values (τ) in the D2DMoE model trained on the CARER dataset. The top row displays results for a standard model, while the bottom row shows results for a model with enforced sparsity. The heatmaps illustrate the percentage of selected experts across layers for three different threshold values (τ = 0.1, τ = 0.01, and τ = 0.001). The high variability across layers and across threshold values highlights the advantage of the dynamic-k expert selection strategy; the model adapts compute allocation to the difficulty of each input.

This figure shows the distribution of the number of executed experts across different layers of a model trained on the CARER dataset using the proposed D2DMoE method. It compares a standard model with a sparsified model, showing that the sparsified model consistently uses fewer experts. The variability in the number of experts across layers and different threshold values (τ) highlights the effectiveness of the dynamic-k expert selection mechanism in D2DMoE, which adapts to the complexity of input data by dynamically choosing the number of experts to execute per layer. This dynamic adaptation leads to computational savings.

This figure shows the dynamic computation allocation of D2DMoE. (a) demonstrates how the number of experts used varies across layers, and this variance is reduced by sparsification. (b) illustrates how D2DMoE focuses computation on semantically important regions of an image, showcasing its adaptability.

This figure shows the distribution of the number of experts used per layer in the D2DMoE model trained on the CARER dataset. It compares a standard model with a sparsified model. The heatmaps show the percentage of selected experts for different thresholds (τ = 0.1, 0.01, 0.001). The high variability in the number of experts across layers and different thresholds highlights the efficiency of the dynamic-k expert selection mechanism, which adapts the number of experts to the input complexity. The sparsified model consistently uses fewer experts than the standard model.

This figure shows the distribution of the number of experts executed per layer for both a standard and a sparsified model trained on the CARER dataset using the D2DMoE method. Three different thresholds (τ) are used to control the number of experts selected. The top row displays results for the standard model, and the bottom row displays results for the sparsified model. The heatmaps illustrate the percentage of selected experts across layers for each threshold value. The high variability in the number of experts used across layers highlights the efficiency of the dynamic-k expert selection method, which adapts to the input complexity.

Full paper#