↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) heavily rely on tokenizers to effectively process and understand text. Traditional tokenization methods, however, often use static, frequency-based approaches that aren’t synchronized with LLM architectures, limiting model performance. This creates a need for more dynamic and adaptive tokenization techniques that can evolve alongside the models.

To tackle this, the researchers propose ADAT (Adaptive Data-driven Tokenizer), a method that refines its tokenizer iteratively during LLM training by monitoring changes in model perplexity. Starting with a large initial vocabulary, ADAT prunes tokens that negatively impact model performance, resulting in an optimized vocabulary that closely aligns with the model’s evolving dynamics. Experimental results confirm that ADAT significantly enhances accuracy over static methods while maintaining comparable vocabulary sizes, showcasing the effectiveness of their adaptive approach.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it proposes ADAT, a novel adaptive tokenizer that significantly improves the accuracy of large language models. This addresses a key challenge in the field by dynamically optimizing tokenization to better align with evolving model dynamics, which is highly relevant to current research focusing on improving LLM efficiency and performance. It opens avenues for research in more sophisticated adaptive tokenization methods and their integration into LLM training pipelines.

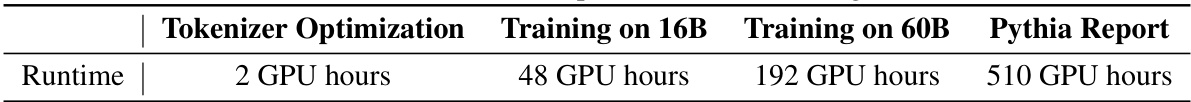

Visual Insights#

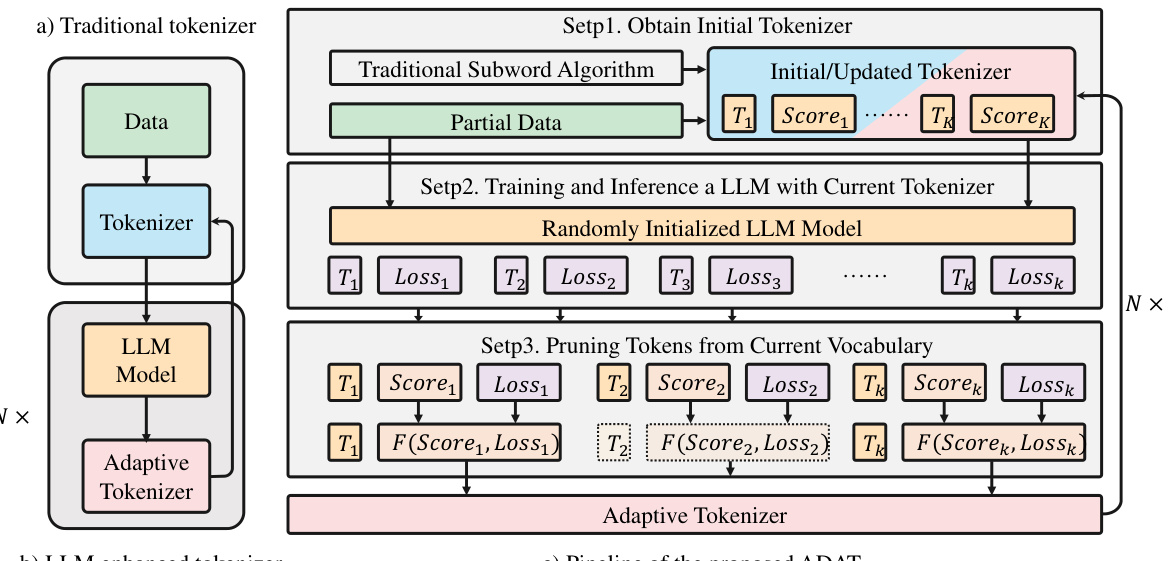

This figure illustrates the Adaptive Tokenizer (ADAT) pipeline. Panel (a) shows a traditional tokenizer’s workflow, which directly creates a vocabulary from data using a subword algorithm. Panel (b) depicts the LLM-enhanced tokenizer which incorporates model feedback to iteratively refine its vocabulary during training. Panel (c) provides a comprehensive overview of ADAT’s process; it shows the stages of initial vocabulary acquisition, LLM training, iterative loss evaluation, and the pruning process for vocabulary optimization based on loss and score functions.

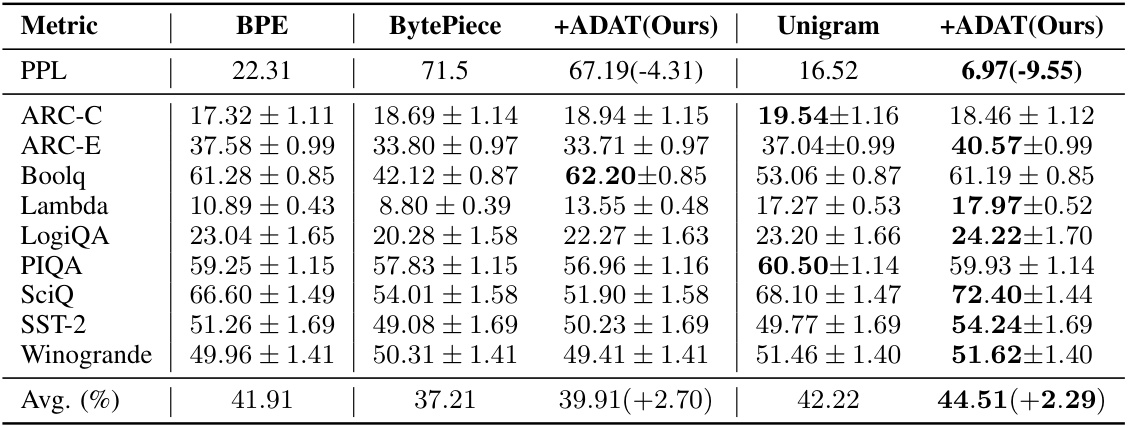

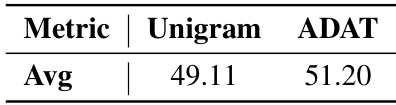

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different tokenization methods, including BPE, BytePiece, Unigram, and the proposed ADAT method, across various metrics such as PPL and several downstream tasks (ARC-C, ARC-E, BoolQ, Lambda, LogiQA, PIQA, SciQ, SST-2, Winogrande). The results show improvements achieved by ADAT over traditional methods. The average percentage improvement is also highlighted.

In-depth insights#

Adaptive Tokenization#

Adaptive tokenization represents a significant advancement in natural language processing by dynamically adjusting the tokenization process to align with a language model’s evolving understanding. Unlike static methods like Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) or Unigram, which create fixed vocabularies, adaptive tokenization refines its vocabulary during the model’s training. This is typically achieved by monitoring metrics such as perplexity and iteratively adjusting the vocabulary based on the model’s performance. This dynamic approach offers several key advantages. First, it leads to improved model accuracy by ensuring that the tokens best reflect the model’s internal representations. Second, it can potentially enhance efficiency by creating a vocabulary tailored to a specific task or model. However, the computational cost of adaptive tokenization and the need for careful monitoring of model performance throughout training are key challenges to overcome. Further research is needed to explore ways to make adaptive tokenization more efficient and practical. This includes developing more sophisticated algorithms for vocabulary refinement and investigating alternative metrics that may be more robust or less computationally intensive.

LLM-Enhanced Loss#

An LLM-Enhanced Loss function represents a significant advancement in the field of large language model (LLM) training. It leverages the LLM’s own internal understanding of language to refine the loss calculation process, moving beyond traditional frequency-based methods. This adaptive approach allows the tokenizer to evolve and better align with the LLM’s dynamic learning patterns, leading to more accurate and efficient training. By incorporating perplexity scores or other LLM-derived metrics, the loss calculation becomes more sensitive to the nuances of language and contextual understanding. This results in a more finely-tuned tokenizer, which ultimately improves the LLM’s performance, accuracy, and potentially inference speed. A key advantage is that the method can maintain comparable vocabulary sizes while significantly improving accuracy. This focus on aligning the tokenizer with the LLM’s evolving representation of language is crucial, and represents a departure from the traditionally static nature of tokenizer optimization.

Vocabulary Pruning#

Vocabulary pruning, a critical step in optimizing large language models (LLMs), aims to reduce the size of the vocabulary while minimizing the loss of information. Effective pruning enhances both the speed and accuracy of the model by removing less useful or redundant tokens. Several methods exist, with Unigram being a prominent example, iteratively removing tokens based on their contribution to overall model loss. However, traditional methods are often static, decoupled from the model’s learning dynamics. The paper proposes an adaptive approach to pruning, monitoring the model’s perplexity during training and using this information to guide the removal of tokens. This allows the vocabulary to adapt and evolve with the model, leading to significant performance gains. In contrast to the static nature of traditional methods, this adaptive strategy ensures that only tokens that become detrimental to the model’s evolving understanding are removed. The optimal balance between minimizing vocabulary size and maintaining model performance is a complex trade-off, which is elegantly addressed through iterative refinement based on live model feedback.

Scalability and Limits#

A discussion on “Scalability and Limits” in a research paper would explore how well the proposed method handles increasing data volumes and model complexities. It would examine the computational resources required and identify potential bottlenecks. Resource constraints, such as memory and processing power, are key limitations to scalability. The analysis should also assess the method’s performance degradation at scale, noting any decline in accuracy or efficiency. Generalizability is another crucial aspect, determining if the model’s effectiveness remains consistent across diverse datasets and tasks beyond those used in the initial experiments. A crucial part of this section is to define the practical limits of the approach—where it becomes computationally infeasible or its accuracy drops unacceptably. It is important to consider if there are any inherent limitations in the method’s design or if the limits are mainly due to current technological constraints. The ultimate goal is to provide a realistic evaluation of the method’s potential applicability in real-world scenarios, acknowledging the trade-off between scalability and performance.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this adaptive tokenizer work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the adaptive approach to other tokenizer types, beyond the Unigram model used here, is crucial for broader applicability. Investigating the impact of different loss functions and weighting schemes on the adaptive process would refine its effectiveness and potentially lead to even better performance gains. A major focus should be placed on thorough analysis of the computational cost and scalability of the adaptive method, particularly for very large language models. This involves exploring more efficient pruning techniques and optimizing the iterative refinement process. Finally, a crucial area for future investigation is the application of adaptive tokenizers to various downstream tasks including machine translation, question answering, and text summarization. By evaluating the adaptive approach’s performance in these diverse applications, its generalizability and utility could be confirmed. A more robust understanding of these aspects will enable the development of truly effective and widely applicable adaptive tokenization methods.

More visual insights#

More on tables

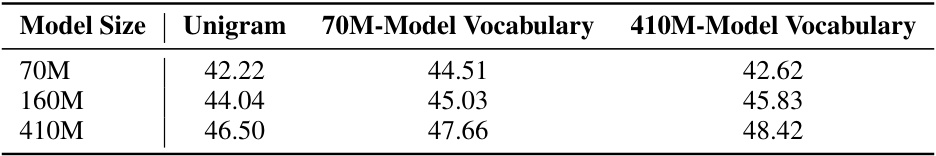

This table presents the performance comparison of the Unigram and ADAT tokenization methods across different model sizes (70M, 160M, and 410M parameters). It shows the perplexity (PPL) and accuracy scores on eight common language modeling benchmark datasets (ARC-C, ARC-E, BoolQ, Lambda, LogiQA, PIQA, SciQ, SST-2, Winogrande) for each model size and tokenization method. The results demonstrate the scalability and effectiveness of the ADAT method across varying model sizes.

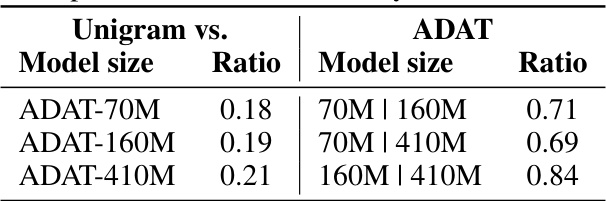

This table shows the performance of different sized language models (70M, 160M, 410M parameters) when using three different vocabularies: a standard Unigram vocabulary and vocabularies optimized for the 70M and 410M model sizes. The results demonstrate the cross-model adaptability of the vocabularies generated by the adaptive tokenizer approach, showing that vocabularies trained on one model size can generalize effectively to other model sizes, improving performance.

This table presents the results of experiments comparing the performance of models trained with different vocabulary sizes (50,000 and 30,000) using two different tokenization methods: Unigram and ADAT. It shows accuracy and perplexity (PPL) scores for two different model sizes (70M and 160M parameters). The table highlights how the ADAT method improves accuracy and reduces perplexity compared to the Unigram method, demonstrating its effectiveness across various vocabulary and model sizes.

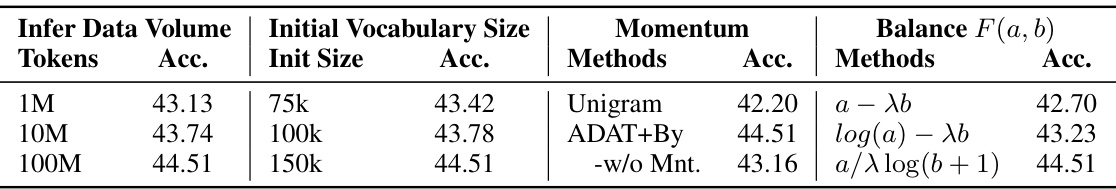

This table presents the ablation study results, showing the impact of variations in the inference corpus size used for calculating token loss, initial vocabulary sizes, momentum strategy, and the balance function F(a, b) on the accuracy of the proposed adaptive tokenizer method. Different configurations are tested to isolate the effects of each of these factors on the overall performance.

This table presents the results of evaluating the performance of different model sizes (70M, 160M, 410M parameters) using various tokenization methods. The metrics used are Perplexity (PPL) and several downstream task evaluation scores, which aim to assess the model’s linguistic capabilities. The results allow for a comparison of the performance impact of the tokenization strategies across different model scales.

This table presents the compression rate achieved by different tokenization methods (BPE, BytePiece, ADAT+By, Unigram, ADAT+U) on the Pythia 70M model. The compression rate is a measure of how efficiently the tokenization method reduces the size of the vocabulary while preserving linguistic information. Lower values indicate higher compression.

This table shows the average performance comparison between the Unigram model and the proposed ADAT method on a 1B parameter model. ADAT demonstrates improved performance over Unigram, indicating its scalability across different model sizes.

This table presents the overlap ratios between vocabularies generated by ADAT and Unigram for different model sizes (70M, 160M, and 410M). The overlap ratio indicates the similarity between the two sets of tokens. It shows that there are significant differences between the vocabularies generated by the two methods, and that the overlap is generally higher for larger model sizes, indicating that ADAT’s vocabularies become more similar to Unigram as model size increases. This also indirectly explains that the tokenizer generated by ADAT-410M is more suitable for Pythia-160M compared to the tokenizer generated by ADAT-70M.

This table shows the distribution of tokens in the initial vocabulary (100k) that fall into different score intervals, comparing the Unigram and ADAT (70M-50k) methods. The results indicate that ADAT relies not only on token frequency but also on the prediction difficulty of tokens during LLM training.

This table presents the results of an experiment investigating the effect of varying the number of training epochs on the performance of a model using vocabularies developed over different numbers of epochs. The relationship between training duration and vocabulary efficacy is evaluated. The table shows accuracy for models trained for 3, 5, and 7 epochs, indicating a clear relationship between training duration and the final model’s accuracy, with gains diminishing after 5 epochs.

This table presents the results of an ablation study investigating the impact of varying inference data volume tokens and initial vocabulary sizes on model performance. It shows accuracy scores for different combinations of inference data volume (1M, 10M, 100M, and 1000M tokens) and initial vocabulary size (75K, 100K, 150K, and 200K tokens). The data illustrates how the model’s performance is affected by the amount of data used for loss calculation and by the initial vocabulary size during the model training process.

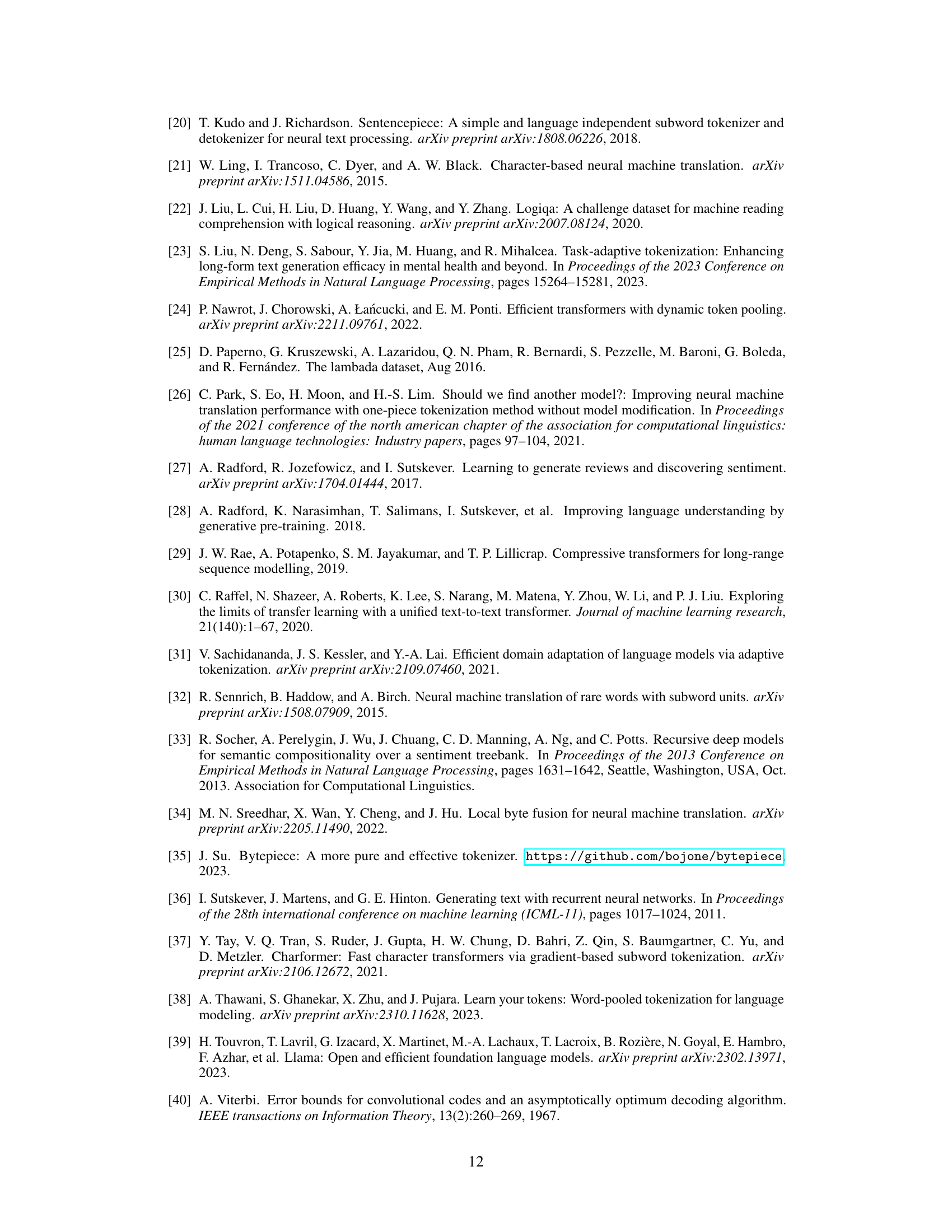

This table presents the specifications of the three different sizes of large language models (LLMs) used in the paper’s experiments. For each model size (70M, 160M, and 410M parameters), it lists the number of layers, the model dimension, the number of heads, the learning rate used during training, and the batch size.

Full paper#