↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Training neural networks involves navigating complex loss landscapes. This paper focuses on shallow ReLU networks, a simpler model to understand these landscapes. A key challenge is that the optimization process, typically using gradient descent, can get stuck in regions of the parameter space that are separated from the optimal solution, making it impossible to find the best solution. This is a problem because the activation function (ReLU) creates a particular geometry in the parameter space, which constrains the optimization trajectory.

The researchers analytically describe these constraints, proving that the parameter space can be fragmented into multiple disconnected parts, significantly impacting the optimization procedure. They precisely quantify this fragmentation and show how the number of disconnected parts depends on the network’s architecture and initialization. Furthermore, they explore the role of symmetries (rescaling and permutation of neurons), demonstrating that they reduce the number of effectively disconnected regions. Their work provides new theoretical insights and a deeper understanding of the challenges in training neural networks. These insights could lead to improvements in training methods and better initialization strategies.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on neural network training and optimization. It reveals fundamental topological obstructions that hinder the training process, particularly in shallow ReLU networks. This challenges the conventional understanding of loss landscapes and opens new avenues for improving training efficiency and avoiding suboptimal solutions. Understanding these obstructions can guide the development of more effective optimization algorithms and initialization strategies, impacting research on various neural network architectures and applications.

Visual Insights#

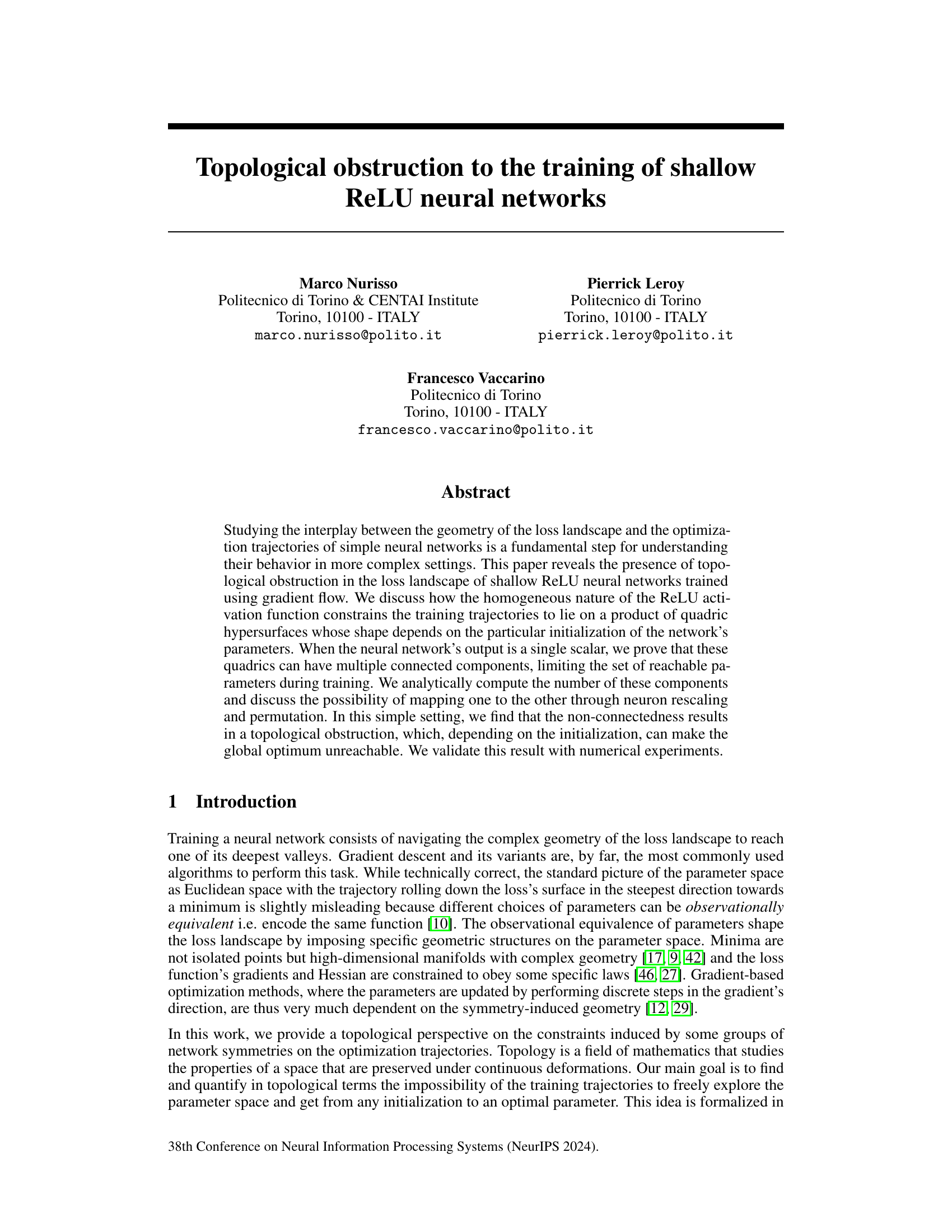

Figure 1 illustrates two group actions on the network’s parameters: neuron rescaling and neuron permutation. Panel (a) visually depicts these actions, showing how rescaling multiplies input and divides output weights by the same factor α, and permutation reorders the neurons. Panel (b) shows the parameter space geometry resulting from ReLU’s rescaling invariance. Orbits (T(θ)) are depicted as dotted lines, and invariant sets (H(c)) are solid lines, demonstrating the gradient’s tangency to H(c) and orthogonality to T(θ).

In-depth insights#

ReLU Geometry#

The ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) activation function’s piecewise linear nature introduces unique geometric properties into neural network loss landscapes. ReLU’s inherent non-smoothness creates regions with sharp changes in gradient, potentially hindering the optimization process. This piecewise linearity results in a complex, non-convex loss landscape with many local minima and saddle points, posing a significant challenge for gradient-based optimization methods. However, the homogeneous nature of ReLU, while introducing challenges, also leads to interesting geometric structures and symmetries in the parameter space. For example, the existence of invariant sets under neuron rescaling and permutation operations could provide insights for improving optimization strategies. Further investigation into ReLU’s geometry could reveal crucial information about the inherent bias of ReLU networks and their tendency towards specific solution types. Understanding these geometric properties is essential for designing improved training algorithms and analyzing network generalization ability. Exploring these geometrical facets, possibly through topological data analysis, could provide better tools to navigate the challenging loss landscapes of ReLU networks.

Training Obstacles#

Training obstacles in neural networks are multifaceted, encompassing issues related to the optimization landscape’s geometry, such as saddle points and local minima, which hinder convergence to a global optimum. High dimensionality of the parameter space exacerbates this problem, often leading to slow convergence or getting trapped in suboptimal regions. The choice of activation functions and network architecture also play a crucial role, with certain choices leading to increased difficulty in training. Vanishing/exploding gradients can prevent effective weight updates, particularly in deep networks. Furthermore, data limitations, such as insufficient data or high noise levels, create significant hurdles during training by making it harder to capture the underlying patterns effectively. Finally, computational constraints frequently impose practical limitations, particularly during training of large-scale models requiring significant memory and processing power.

Symmetry Effects#

Symmetries play a crucial role in shaping the loss landscape and the optimization process of neural networks. Weight rescaling, a common symmetry in networks with homogeneous activation functions like ReLU, leads to observationally equivalent networks, effectively reducing the dimensionality of the parameter space. This symmetry constrains optimization trajectories to lie on specific geometric structures, such as quadric hypersurfaces. The connectedness of these structures is critical, as disconnectedness can create topological obstructions, preventing gradient-based methods from reaching global optima. Furthermore, neuron permutations induce another symmetry, suggesting that seemingly distinct parameter configurations might actually be observationally equivalent. Understanding and leveraging these symmetry effects could pave the way for designing more efficient training algorithms or for developing novel regularization techniques to mitigate the problem of spurious local minima. The interplay between symmetry-induced constraints and the topology of the loss landscape is a rich and fascinating area that deserves further investigation.

Topological Limits#

The concept of “Topological Limits” in a research paper likely refers to constraints on the parameter space of a model imposed by its intrinsic geometric and topological properties. These constraints can prevent the optimization algorithm from reaching the global optimum, even if it’s theoretically possible. The paper might explore how these limitations depend on the model’s architecture, activation function, and the specific optimization method. It could delve into how topological features of the loss landscape, such as connected components or the presence of saddle points, limit the search space of gradient descent. Furthermore, symmetries of the model can play a crucial role, creating observationally equivalent parameters and reducing the effective degrees of freedom. This might lead to identifying specific regions in the parameter space that are unreachable regardless of initialization or optimization strategy, highlighting the inherent limitations of common training methodologies. The analysis could involve the use of Betti numbers or other topological invariants to characterize the complexity and connectivity of the parameter space. Overall, “Topological Limits” suggests a deep investigation into the fundamental interplay between a model’s geometry, its topological structure and the achievable solutions via optimization.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this topological analysis of ReLU network training could involve extending the theoretical framework to deeper networks, investigating the impact of different activation functions and loss landscapes, and exploring the interplay between topological obstructions and optimization algorithms. A particularly interesting avenue would be to develop techniques to mitigate the topological obstructions, perhaps by incorporating topological information into the initialization process or the optimization strategy itself. Furthermore, empirical investigations could focus on verifying the theoretical predictions across a broader range of network architectures and datasets, particularly examining the relationship between network size, dataset properties and the prevalence of topological bottlenecks. Finally, investigating the practical implications of these topological obstructions on generalization performance and how they relate to other forms of implicit bias is vital. This would offer a deeper understanding of the training dynamics of neural networks and potentially inform the development of more efficient and robust training methods.

More visual insights#

More on figures

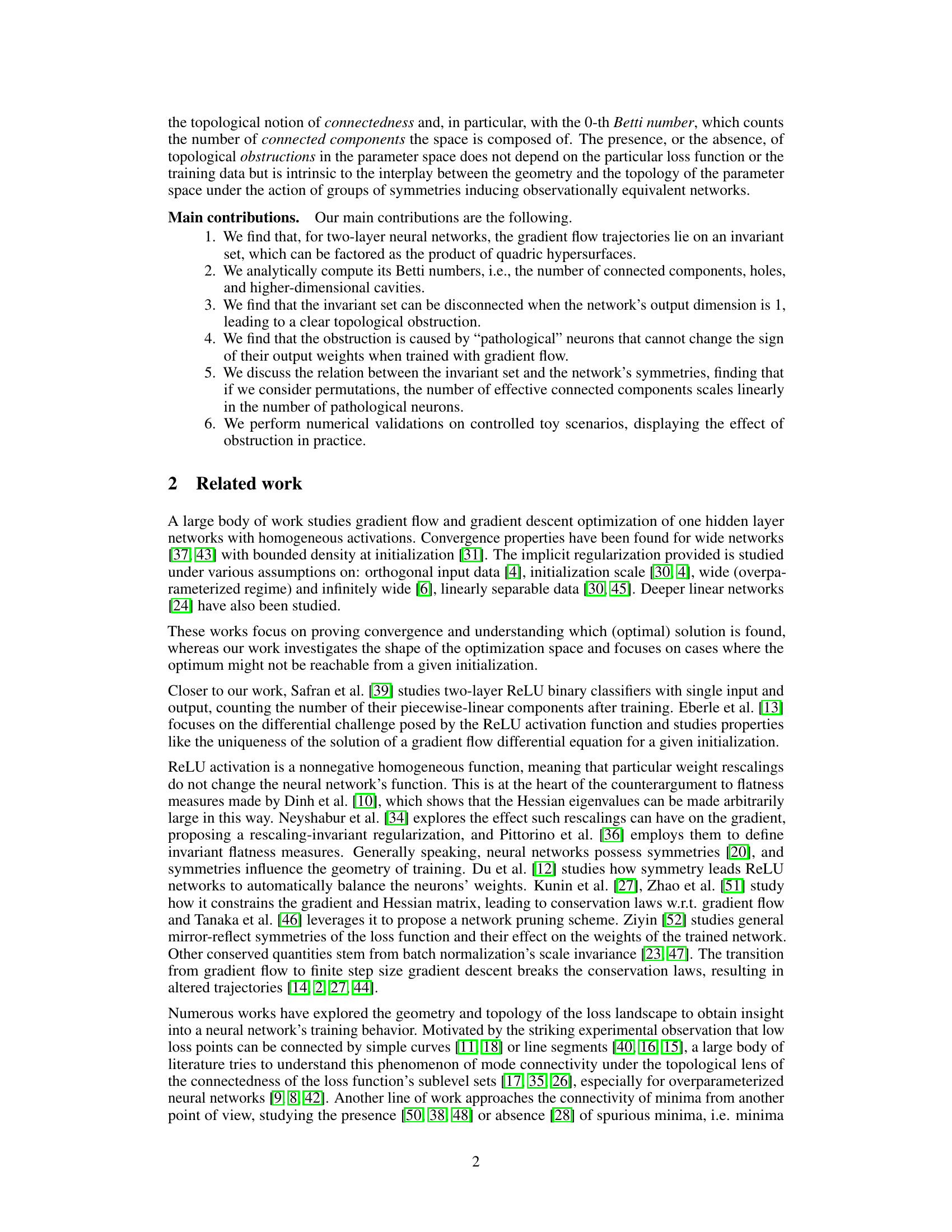

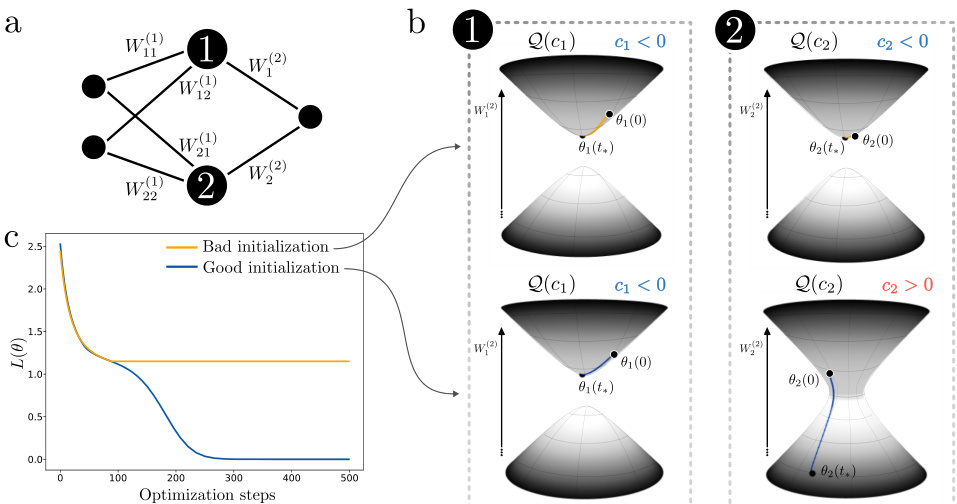

This figure visualizes the geometry of the invariant sets in the parameter space of a two-layer ReLU neural network. Panel (a) shows the shapes of the invariant hyperquadrics Q(ck) for a single neuron with two inputs and one output, for both positive and negative values of ck. Panel (b) illustrates the invariant set H(c) for the entire network when there are two neurons with ck < 0, resulting in four connected components. These components are grouped into three effective components based on the symmetries discussed in the paper. The figure highlights how the geometry of the invariant set can lead to topological obstructions during training, depending on the initialization.

This figure visualizes an experiment’s setup to demonstrate topological obstruction in training shallow ReLU neural networks. Panel (a) shows the simple two-layer neural network architecture. Panel (b) illustrates the parameter space of two hidden neurons, showing how the gradient descent trajectory is constrained by the invariant hyperquadrics. It highlights two scenarios: one with topological obstruction (the trajectory gets stuck), and another without (the trajectory reaches the optimum). Panel (c) presents the loss curves for both scenarios.

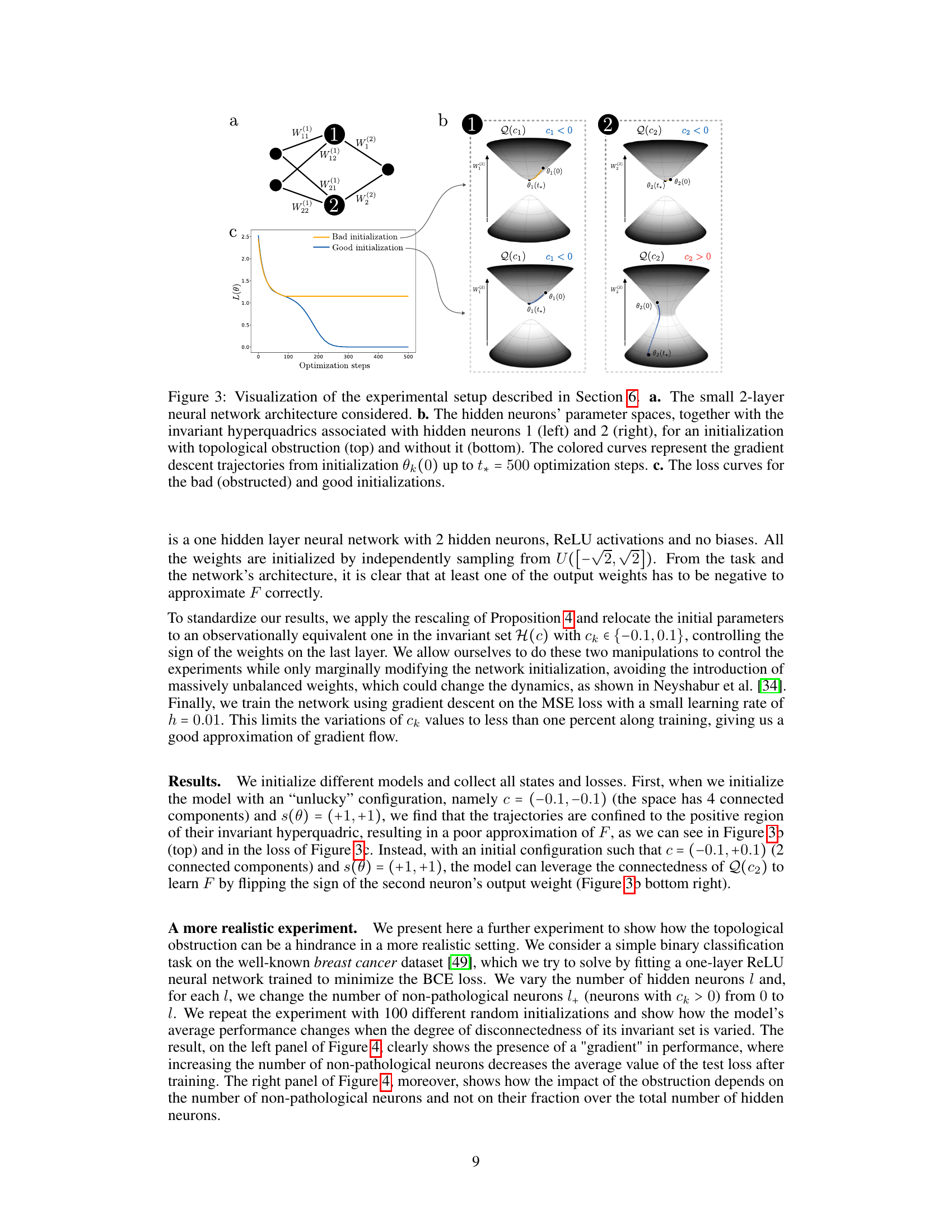

This figure displays the average test BCE loss of a two-layer ReLU neural network trained on the breast cancer dataset. The left panel shows the average loss for different numbers of total neurons (l) and non-pathological neurons (l+), revealing a performance gradient where increasing non-pathological neurons improves performance. The right panel visualizes the same data, showing the average test loss depending on the percentage of non-pathological neurons. This illustrates that the topological obstruction’s impact depends on the absolute number of non-pathological neurons rather than the proportion.

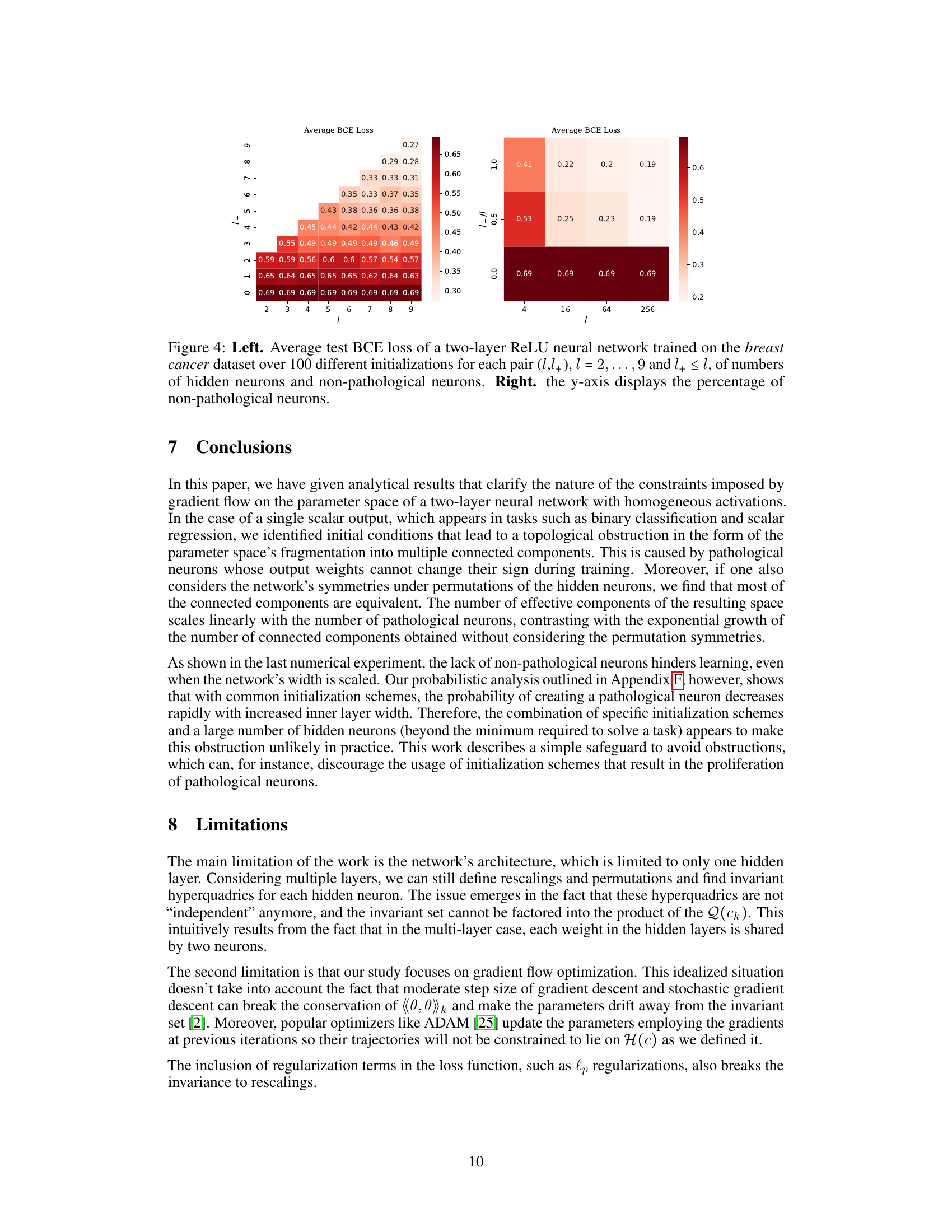

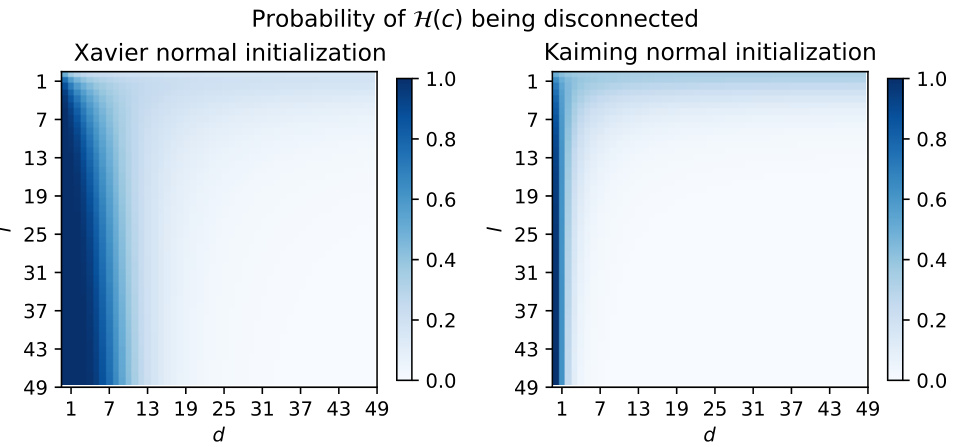

This figure shows the probability of encountering a topological obstruction during the training of a neural network, as a function of the number of input neurons (d) and hidden neurons (l). The obstruction arises from the loss landscape having multiple disconnected components. Two common weight initialization schemes are compared: Xavier and Kaiming normal initialization. The heatmaps illustrate that the probability of obstruction is significantly higher for smaller input dimensions (d) and is generally lower for the Kaiming scheme. For larger d values, the probability decreases rapidly for both initialization methods. This suggests that using appropriate initialization and sufficient input dimension can mitigate the risk of this topological obstruction.

Full paper#