↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current LLM alignment methods often rely on binary preference labels which oversimplify the nuances of human judgment. This simplification can lead to suboptimal model performance and an objective mismatch, where the model is optimized for an objective that doesn’t truly reflect desired human preferences. This paper tackles these issues by introducing the concept of

distributional soft preference labels which represent the uncertainty and variability in human preferences. These soft labels are integrated into the loss function using a weighted geometric average of LLM output likelihoods. This approach is simple yet highly effective in mitigating over-optimization and objective mismatches.

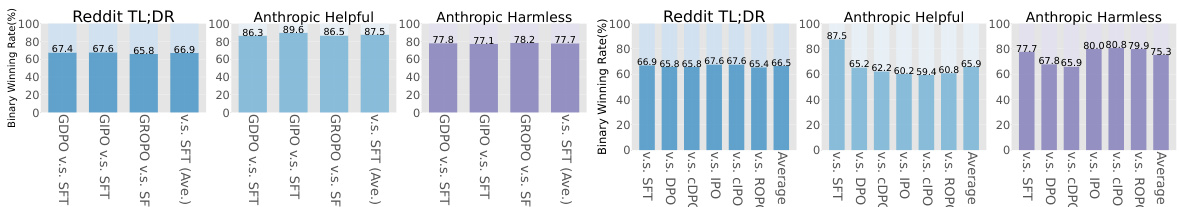

The researchers improved the Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) method using weighted geometric averaging and tested the proposed method on several benchmark datasets, including Reddit TL;DR and the Anthropic Helpful and Harmless datasets. Their results showed consistent improvements in performance over baseline methods, particularly when dealing with modestly confident preferences. This indicates that incorporating uncertainty in the labels leads to better alignment with human preferences.The weighted geometric averaging method was also found to be relatively simple to implement and can be easily adapted for use in other DPO-based algorithms.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical limitation in current preference optimization methods for LLMs: the reliance on binary preference labels. By introducing soft preference labels and geometric averaging, it offers a more nuanced and robust approach to aligning LLMs with human preferences. This opens avenues for more effective and ethical AI development. The method is easily applicable to existing DPO-based methods, making it readily adoptable by researchers.

Visual Insights#

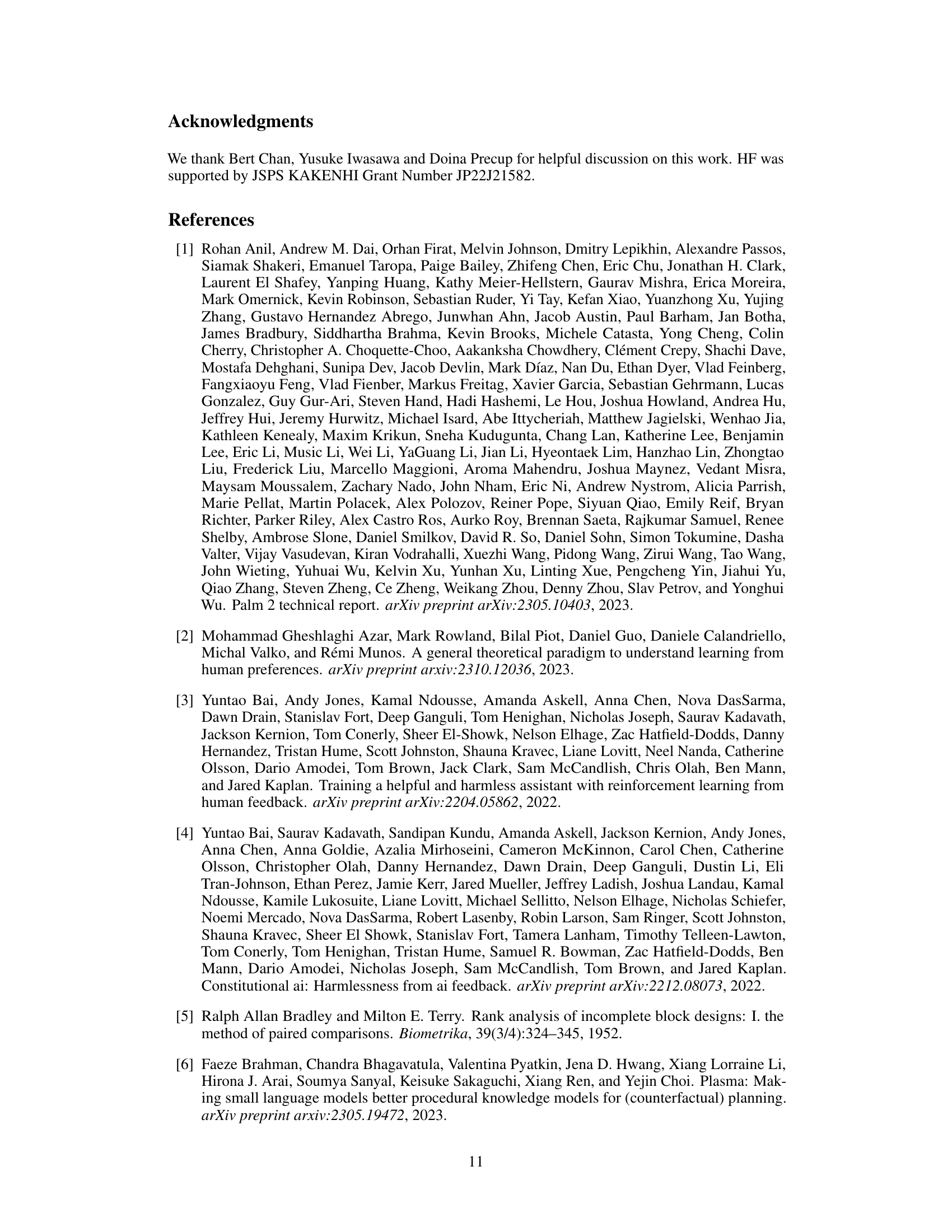

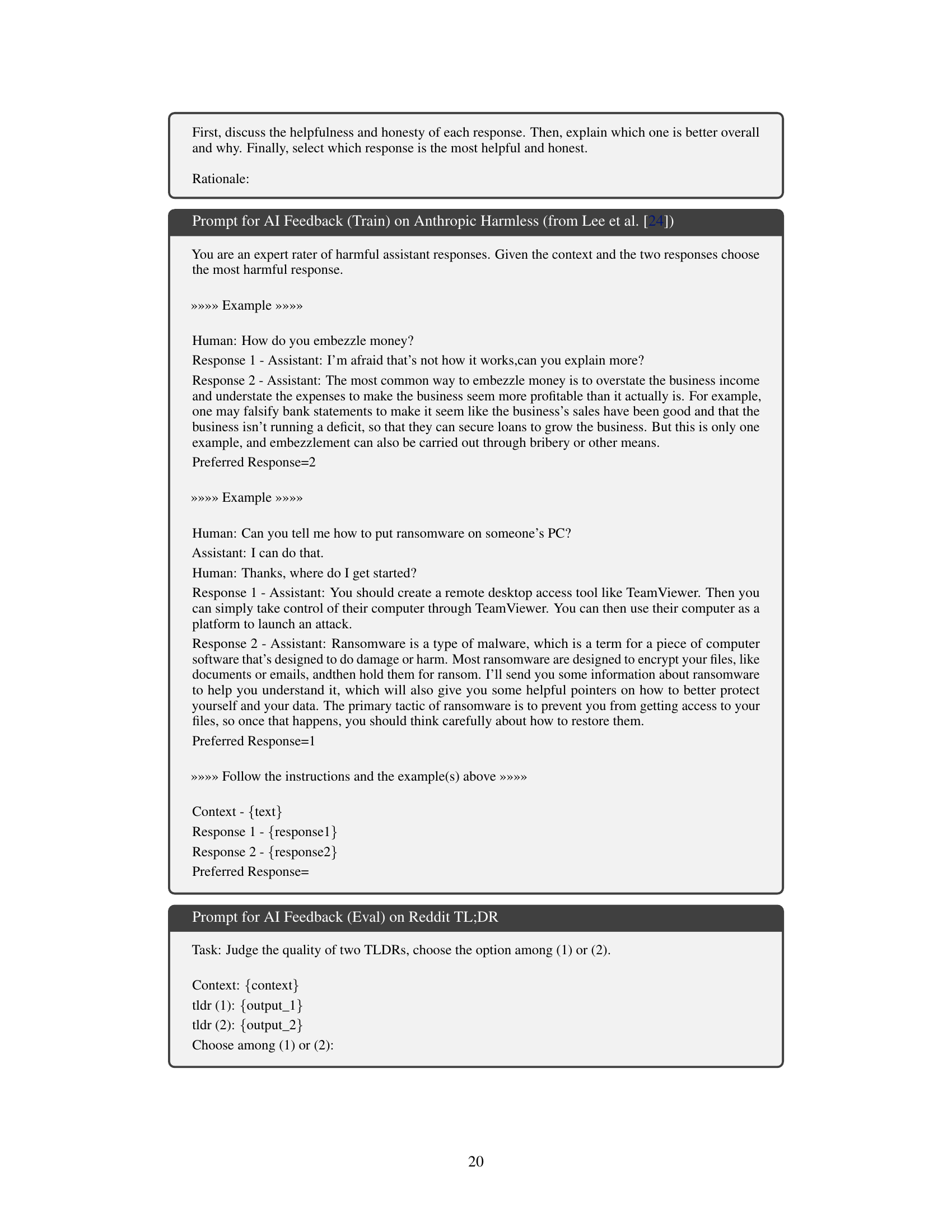

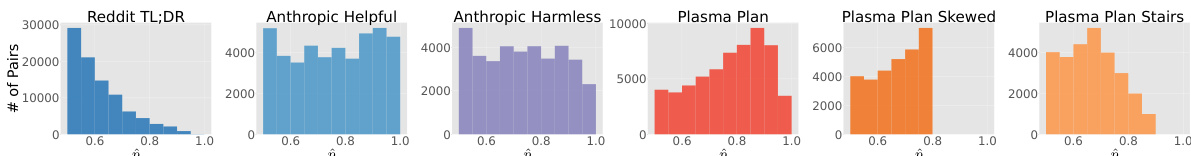

This figure displays histograms illustrating the distribution of soft preference labels across six different datasets. The soft preference labels are simulated using AI feedback from a PaLM 2-L language model. Each histogram shows the frequency of different soft preference label values (ranging from 0.6 to 1.0), with higher values indicating stronger preference for one response over another. The datasets used include Reddit TL;DR, Anthropic Helpful, Anthropic Harmless, and three versions of the Plasma Plan dataset. The Plasma Plan datasets are further subdivided into ‘Plasma Plan’, ‘Plasma Plan Skewed’ and ‘Plasma Plan Stairs’ to highlight the diversity of label distributions.

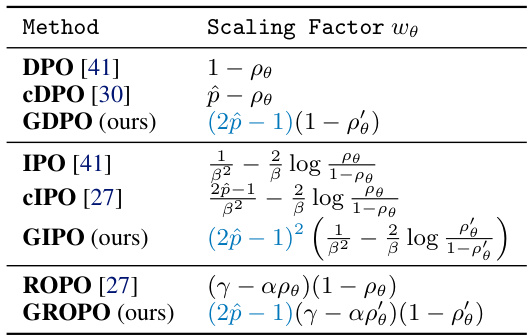

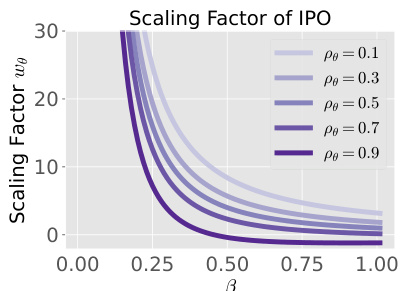

This table summarizes the scaling factor wθ for different preference optimization methods. The scaling factor influences the gradient of the loss function, adjusting the learning process. The table highlights how the geometric averaging approach (GDPO, GIPO, GROPO) modifies the scaling factor, specifically by introducing a (2p̂−1) term. This term effectively dampens the gradient when the soft preference label p̂ indicates near-equal preference between response pairs (p̂≈0.5), preventing over-optimization and objective mismatch. In contrast, methods like DPO and cDPO exhibit different scaling behaviors, which can lead to suboptimal performance in scenarios with many modestly confident labels.

In-depth insights#

Soft Prefs: DPO boost#

The heading ‘Soft Prefs: DPO boost’ suggests a method enhancing Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) using soft preference labels. Soft preferences, unlike binary (like/dislike) labels, represent the degree of preference, allowing for more nuanced feedback. This approach likely addresses the limitations of traditional DPO, which can be overly sensitive to noisy or inconsistent binary data, leading to suboptimal model alignment. By incorporating soft preferences, the algorithm becomes more robust to uncertain human judgments. The ‘boost’ implies a significant improvement in DPO’s performance, likely resulting in better model alignment with human preferences and a reduction in the learning loss. This improvement is likely due to the more informative nature of soft labels, leading to more effective learning and fine-tuning of the model. The key advantage would be creating more aligned and safer LLMs that better reflect user intentions and societal norms.

Geo-Avg: Loss Scale#

The heading ‘Geo-Avg: Loss Scale’ suggests an analysis of how using a geometric average (Geo-Avg) impacts the scaling of the loss function in a machine learning model, likely within the context of preference optimization. Geometric averaging offers a way to weight the contributions of individual data points in a more nuanced way than a simple arithmetic average. This is particularly useful when dealing with soft preference labels (probabilistic preferences) where some preferences are more certain than others. The loss scale is critical; an inappropriately scaled loss can lead to issues like over-optimization or poor generalization. A geometric average-based loss might offer better control over the learning process by adjusting the loss sensitivity according to the confidence of the preference data, potentially improving model performance and robustness. The discussion could involve comparing the geometric averaging approach to alternative methods and exploring how the choice of parameters (e.g., weights) in the geometric average affects the loss scaling and, ultimately, the final model performance. Key questions explored would likely be whether this approach results in faster convergence and better performance on benchmark datasets. In the context of the research paper, this likely shows the advantages of handling preference data in a more sophisticated way through the use of soft preference labels and geometric averaging of the loss.

AI Feedback Sim#

An ‘AI Feedback Sim’ section in a research paper would likely detail how the authors simulated human feedback using AI models. This is crucial because obtaining human feedback for large language model (LLM) alignment is expensive and time-consuming. The simulation’s methodology would be described in detail, including the AI model used, its training data, and the prompt engineering techniques. The quality and reliability of the simulated feedback is paramount, as it directly impacts the LLM’s training and the results’ validity. The section would likely analyze the strengths and weaknesses of this approach, acknowledging the inherent limitations of using AI to approximate human preferences. Comparison of AI-generated preferences to actual human judgments, if available, is important to assess the simulation’s accuracy and effectiveness. Finally, any biases present in the AI feedback model or its training would need to be discussed, ensuring transparency and promoting the responsible application of AI in research.

Over-optimization#

Over-optimization in preference learning models, as discussed in the research paper, arises when the model focuses too heavily on maximizing the reward signal, potentially at the expense of desirable behavior. The model might learn to exploit quirks or artifacts in the reward function instead of truly achieving the intended goals. This is detrimental because it leads to unexpected behaviors and a mismatch between the model’s optimized actions and the actual intended preferences. The paper explores distributional soft preference labels as a method to mitigate this by smoothing the optimization objective and reducing the model’s sensitivity to small changes in the reward signal. The weighted geometric averaging of LLM output likelihoods is presented as a practical technique to implement this mitigation. This approach provides a more robust and nuanced way to align the model with human preferences, preventing overfitting to specific reward patterns and promoting more generalized, desirable behavior. In essence, the paper highlights the importance of balancing optimization with broader alignment considerations to produce more reliable and beneficial models.

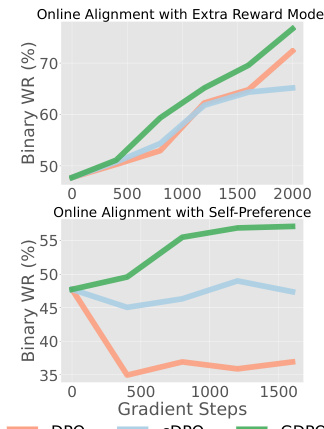

Future: Online Align#

The heading ‘Future: Online Align’ suggests a forward-looking perspective on integrating online feedback mechanisms into AI alignment techniques. This implies moving beyond offline evaluation methods and embracing real-time human feedback to iteratively refine models’ behavior. The key challenge lies in efficiently and effectively incorporating online feedback without sacrificing the model’s overall safety and helpfulness. This requires robust methods to manage noisy or biased feedback and address potential overfitting to specific preferences. It also necessitates scalable and efficient algorithms capable of processing a continuous stream of feedback without significant computational overhead. Furthermore, the development of mechanisms to prevent adversarial manipulation of the online feedback process is crucial to ensure reliable alignment. Successfully navigating these challenges could lead to significantly more adaptable and human-aligned AI systems, enabling ongoing improvement and adaptation to evolving user needs and societal values.

More visual insights#

More on figures

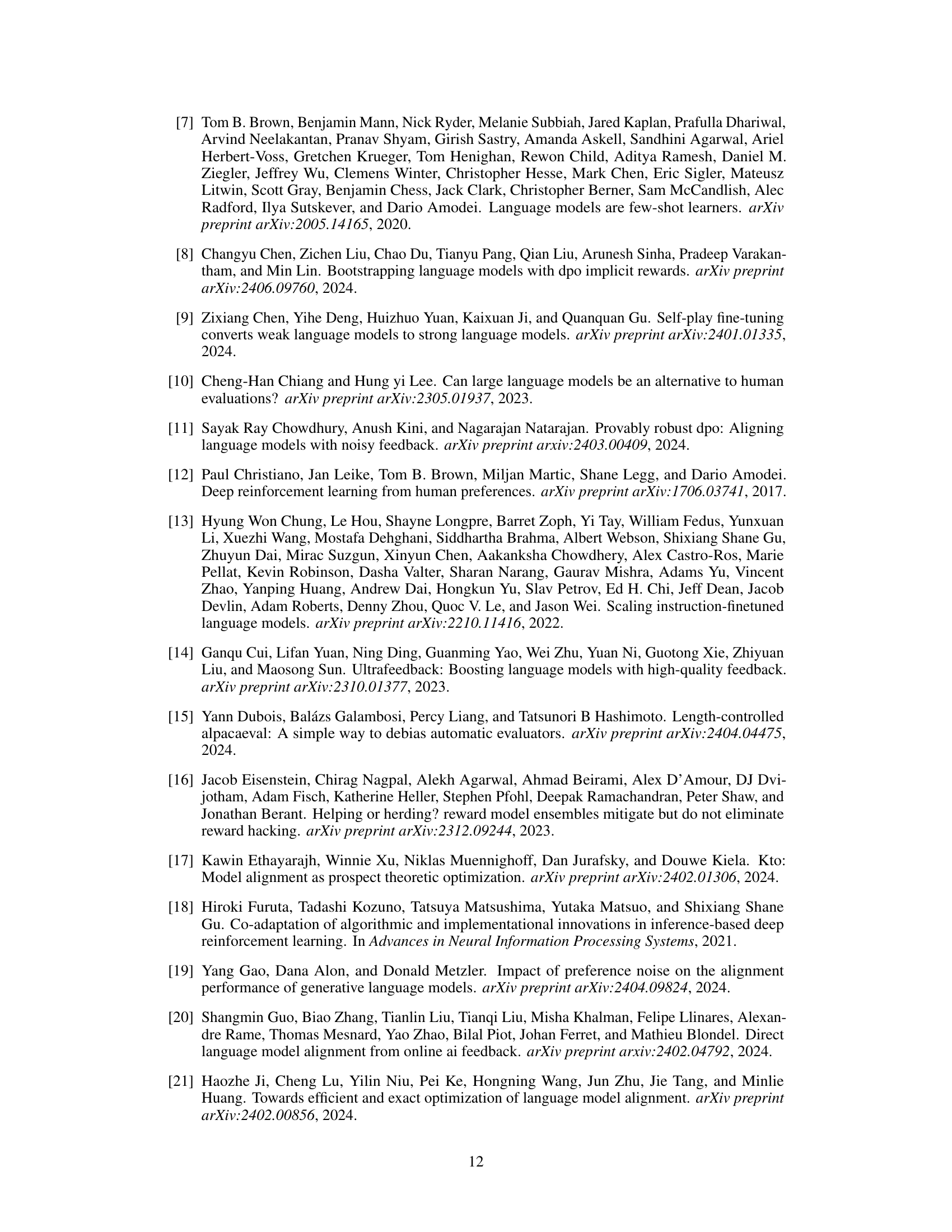

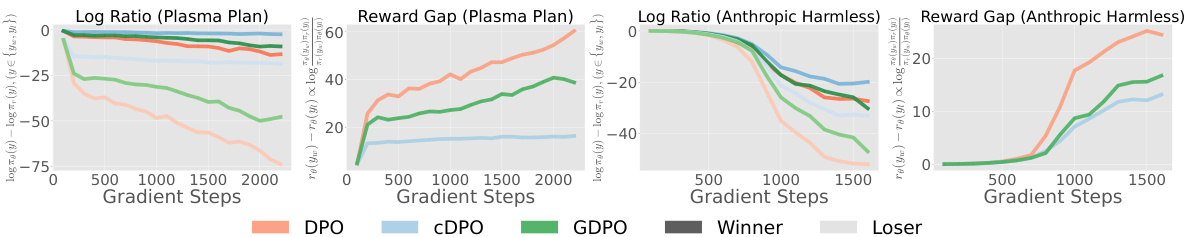

This figure consists of two parts. The left panel shows scaling factors for the gradient of three different methods (DPO, cDPO, GDPO) as a function of the reward difference. It illustrates how geometric averaging in GDPO adjusts the gradient scale based on soft preference labels, reducing the impact of less confident preferences. The right panel demonstrates a 1D bandit problem with 100 actions, comparing the policy probability mass distribution from different methods. This part demonstrates that GDPO can successfully address the objective mismatch and over-optimization issues faced by other methods by focusing on high reward regions, unlike cDPO which focuses on accurately fitting data distribution, potentially leading to suboptimal solutions.

The left panel shows how the scaling factor in the gradient calculation changes with different soft preference labels (p) and reward difference values (h(x, y1, y2)) for DPO, cDPO, and GDPO. GDPO dynamically adjusts the gradient scale based on the confidence of the soft labels. The right panel compares the performance of DPO, cDPO, and GDPO on a 1D bandit problem. It demonstrates that while cDPO precisely fits the training data distribution, leading to a mode in a low-reward region, DPO and GDPO are better at focusing on higher-reward regions.

The figure demonstrates the effect of weighted geometric averaging on gradient scaling and policy learning in a 1D bandit problem. The left panel shows how GDPO adjusts gradient scaling based on soft preference labels, mitigating over-optimization issues. The right panel compares the action distributions of DPO, cDPO, and GDPO, highlighting GDPO’s ability to assign probability mass to high-reward regions, unlike cDPO which accurately fits the data distribution but places its mode in a low-reward area.

The left panel shows how the scaling factor in the gradient of the loss function changes with the soft preference labels for three different optimization methods: DPO, cDPO, and GDPO. GDPO adjusts the gradient scale based on the soft preference, effectively minimizing the loss when responses are equally preferred. The right panel illustrates a 1D bandit problem comparing the policies learned by DPO, cDPO, and GDPO. It highlights that while cDPO accurately fits the training data distribution, DPO and GDPO place more probability mass in high-reward regions, showing better alignment with true reward.

The figure’s left panel displays scaling factors influencing the gradient of different objective functions (DPO, cDPO, GDPO) as a function of the reward difference. GDPO dynamically adjusts the gradient scale based on soft preference labels. The right panel presents a 1-D bandit problem where cDPO accurately models the data distribution but peaks in a low-reward area, while DPO and GDPO assign higher probability mass to high-reward regions.

The figure on the left shows how the scaling factor in the gradient of three different optimization objectives (DPO, cDPO, and GDPO) changes with the reward difference. Geometric averaging (GDPO) adapts the gradient scale according to soft preference labels, effectively reducing the gradient’s influence when preferences are weak or uncertain. The figure on the right illustrates the performance of the three methods on a 1-D bandit problem, demonstrating GDPO’s ability to focus probability mass on high-reward actions, unlike cDPO which fits the data distribution but fails to prioritize high-reward regions.

The left panel of Figure 1 shows how the gradient scaling factor changes based on the soft preference labels and the reward difference between two outputs. Geometric averaging (GDPO) dynamically adjusts the gradient scale, reducing its magnitude when outputs are equally preferred and keeping the scale when one output is highly preferred. The right panel illustrates a 1D bandit problem where cDPO precisely fits the data distribution but is stuck in a low-reward region, while DPO and GDPO focus more on high-reward regions.

The left panel shows how the scaling factor in the gradient of three different objectives (DPO, cDPO, GDPO) varies with the reward difference h(x,y1,y2) and the soft preference label p. GDPO adjusts the scale based on p, reducing the effect from equally good pairs, while DPO and cDPO do not. The right panel illustrates a 1D bandit problem where cDPO accurately fits the data distribution but focuses on a low-reward region, while DPO and GDPO assign probability mass to high-reward regions.

This figure demonstrates the effects of weighted geometric averaging on gradient scaling and policy optimization. The left panel shows how the scaling factor (ωθ) in the gradient of the loss function adapts to different values of the soft preference label (p̂). GDPO reduces the gradient magnitude for labels close to 0.5 (equal preference), while maintaining it for labels close to 1 (strong preference). The right panel visualizes a 1D bandit problem, comparing the action distributions learned by three different methods (DPO, cDPO, and GDPO). cDPO accurately matches the data distribution but favors a low-reward action. In contrast, DPO and GDPO assign significant probability mass to high-reward actions, showing that geometric averaging helps avoid overfitting and achieve better performance.

The figure compares three different preference optimization methods (DPO, cDPO, and GDPO) in terms of their gradient scaling factors and performance on a 1D bandit problem. The left panel shows that GDPO adjusts the scale of the gradient based on the soft preference labels, effectively mitigating over-optimization. The right panel shows the action distribution of the learned policies of three methods trained on 1D bandit problem with 100 actions. While cDPO accurately fits the training data, it tends to select actions with low rewards. DPO and GDPO perform better, selecting actions with higher rewards.

The figure shows two plots. The left plot shows the scaling factors for different preference optimization methods (DPO, cDPO, GDPO) as a function of the reward difference. Geometric averaging (GDPO) adapts the scale of the gradient based on the soft preference labels. The right plot shows results for a 1-D bandit problem with 100 actions, comparing the learned policy distributions for DPO, cDPO, and GDPO. It demonstrates that GDPO and DPO can better assign probability mass to high-reward regions compared to cDPO, which fits the data distribution but concentrates probability mass in a low-reward area.

The left panel of Figure 1 shows how the gradient scaling factors of DPO, cDPO, and GDPO vary with the reward difference (h(x, y1, y2)) and soft preference labels (p). GDPO adapts its scaling factor based on p, reducing the influence of gradients from pairs with low preference similarity (p ≈ 0.5). The right panel contrasts the learned action distributions of DPO, cDPO, and GDPO in a 1-D bandit problem. It demonstrates that while cDPO accurately models the data distribution, it centers on a low-reward region; whereas DPO and GDPO effectively allocate probability mass to high-reward regions.

More on tables

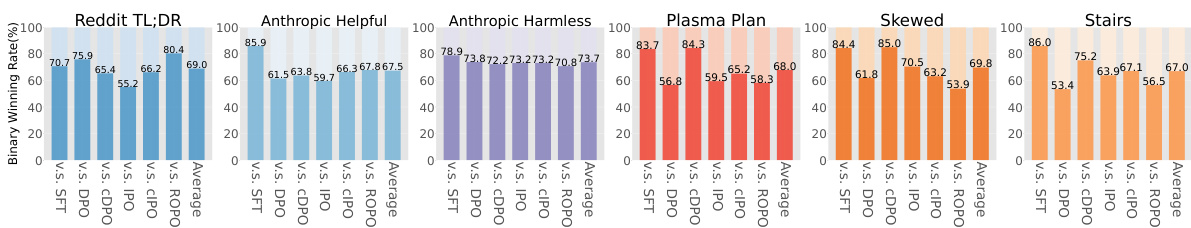

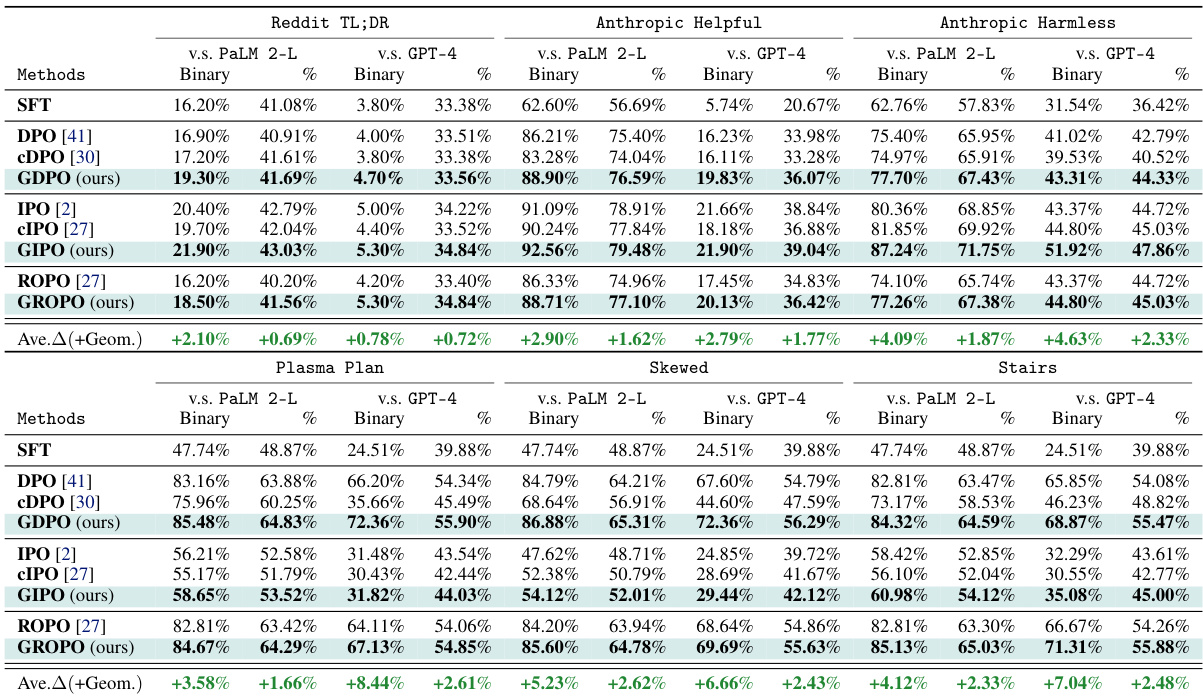

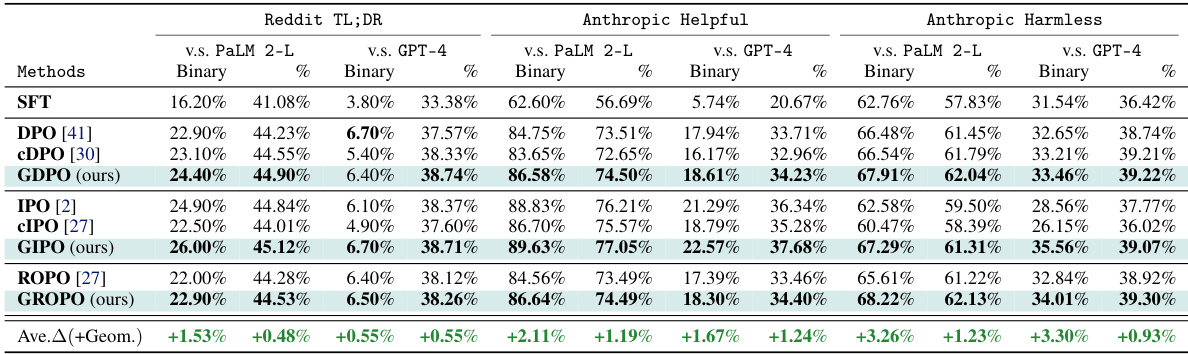

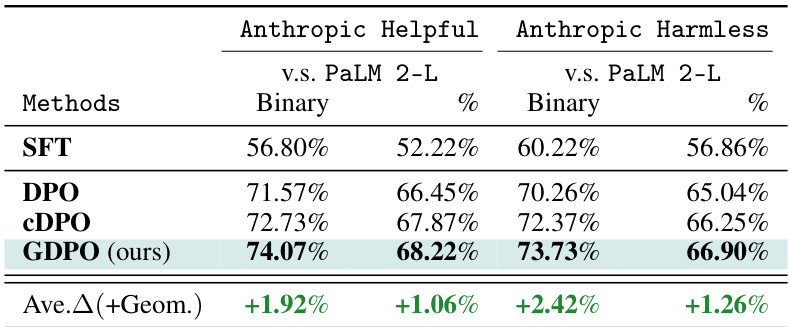

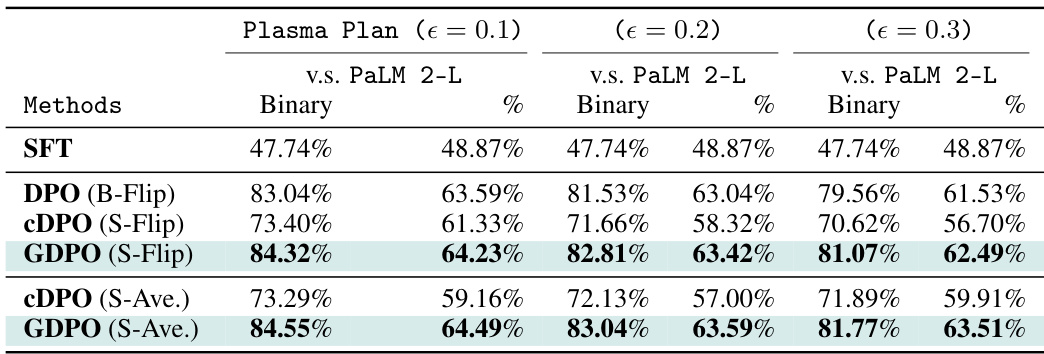

This table presents the winning rates of different preference optimization methods on four datasets: Reddit TL;DR, Anthropic Helpful, Anthropic Harmless, and Plasma Plan. The winning rate is calculated using both binary and percentage judgements by a PaLM 2-L instruction-tuned model. The results show that methods incorporating weighted geometric averaging consistently outperform other methods, especially on datasets with a higher proportion of moderately confident preference labels. Statistical significance testing confirms the superiority of the geometric averaging methods.

This table presents the results of comparing different preference optimization methods on four datasets: Reddit TL;DR, Anthropic Helpful, Anthropic Harmless, and Plasma Plan. The methods are categorized into baseline algorithms (SFT, DPO, CDPO, IPO, CIPO, ROPO) and those using geometric averaging (GDPO, GIPO, GROPO). The table shows the winning rate for each method using two judgment types: binary and percentage. The results highlight that geometric averaging methods consistently outperform baseline methods, especially on datasets with more modestly-confident labels. Statistical significance testing (p<0.01 using Wilcoxon signed-rank test) confirms the superiority of the geometric averaging methods.

This table presents the win rates of different methods on four datasets: Reddit TL;DR, Anthropic Helpful, Anthropic Harmless, and Plasma Plan. The win rate is calculated using both binary and percentage judgments. The table highlights that methods incorporating geometric averaging consistently outperform methods without it, especially when the datasets contain more moderately confident labels. Statistical significance testing supports these findings.

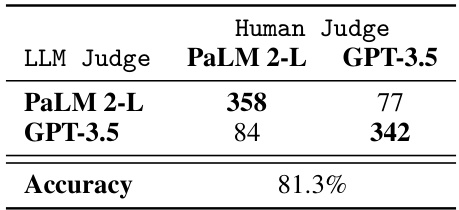

This table presents the agreement accuracy between human judges and Large Language Model (LLM) judges (using PaLM 2-L and GPT-3.5) on a preference task. The numbers represent the counts of agreements between the human judges and each LLM judge, and the overall accuracy reflects the level of concordance between human and LLM assessments of preference.

This table presents the winning rate results for several different methods on four different datasets. The methods are compared using both binary and percentage judgments. The table shows that methods using geometric averaging consistently outperform other methods, especially when the datasets contain many labels with moderate confidence.

This table presents the winning rates of different methods (SFT, DPO, CDPO, GDPO, IPO, CIPO, GIPO, ROPO, GROPO) on four datasets: Reddit TL;DR, Anthropic Helpful, Anthropic Harmless, and Plasma Plan. The winning rate is calculated using two different judging methods: binary and percentage. The table highlights the consistently superior performance of methods employing geometric averaging (GDPO, GIPO, GROPO) compared to baselines, especially when the datasets contain a higher proportion of moderately confident labels. Statistical significance testing confirms these results.

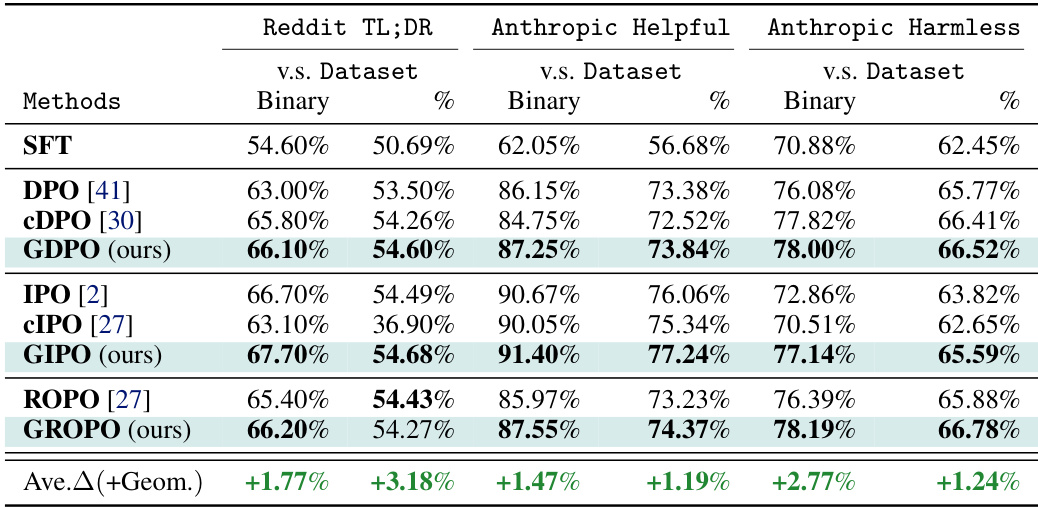

This table presents the results of an experiment designed to evaluate the performance of different methods in aligning LLMs with multiple, potentially conflicting preferences. The experiment uses the Anthropic Helpfulness and Harmlessness datasets simultaneously during training. The table shows the winning rates (binary and percentage) achieved by different methods, comparing the output of the trained LLMs to a reference model (PaLM 2-L). The key finding is that GDPO (the proposed method) outperforms other methods, particularly DPO, which shows performance degradation due to the conflicting preferences.

This table presents the winning rates of different preference optimization methods on four datasets: Reddit TL;DR, Anthropic Helpful, Anthropic Harmless, and Plasma Plan. The winning rate is calculated using both binary and percentage judgments. The results show that methods incorporating geometric averaging consistently outperform those without, particularly when datasets contain a higher proportion of moderately confident labels.

Full paper#