↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Offline Reinforcement Learning (RL) faces challenges with return-conditioned supervised learning (RCSL) due to its lack of stitching ability, hindering the combination of suboptimal trajectory segments for better overall performance. Value-based methods using Q-functions, while capable of stitching, suffer from over-generalization, negatively impacting stability.

The proposed Q-Aided Conditional Supervised Learning (QCS) method addresses these challenges. QCS cleverly integrates Q-function assistance into RCSL’s loss function based on trajectory return. This adaptive approach leverages the strengths of both methods: RCSL’s stability for optimal trajectories and Q-function’s stitching for suboptimal ones. Empirical results across several benchmarks show QCS consistently outperforms RCSL and value-based methods, showcasing its effectiveness in various offline RL scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in offline reinforcement learning as it presents Q-Aided Conditional Supervised Learning (QCS), a novel method that significantly improves the performance of existing techniques. It tackles the limitations of current approaches by adaptively integrating Q-functions into return-conditioned supervised learning, thus offering a more robust and effective approach. The findings are highly relevant to the current trends of combining value-based and policy-based offline RL methods and open new avenues of research for improving stitching ability and preventing over-generalization.

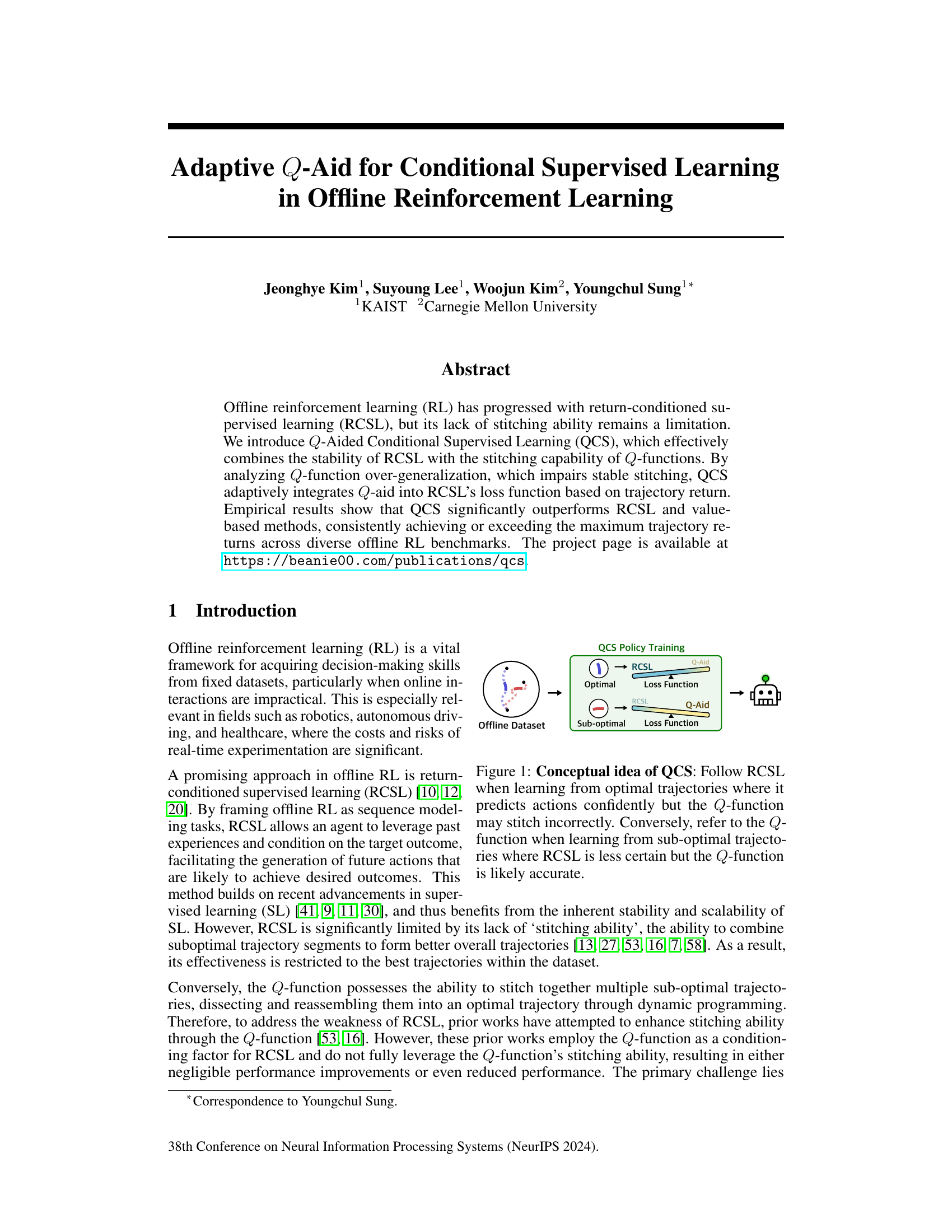

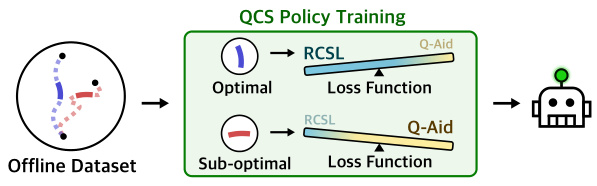

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the core concept of Q-Aided Conditional Supervised Learning (QCS). QCS adaptively combines Return-Conditioned Supervised Learning (RCSL) and Q-functions. When the agent learns from optimal trajectories, RCSL is prioritized due to its inherent stability and accuracy in predicting confident actions. However, RCSL struggles with stitching suboptimal trajectory segments to improve overall performance. Therefore, when the agent encounters suboptimal trajectories, the Q-function’s stitching ability is leveraged to create a more accurate loss function. The weighting between RCSL and the Q-function is dynamically adjusted based on the trajectory return; higher returns favor RCSL, lower returns favor the Q-function.

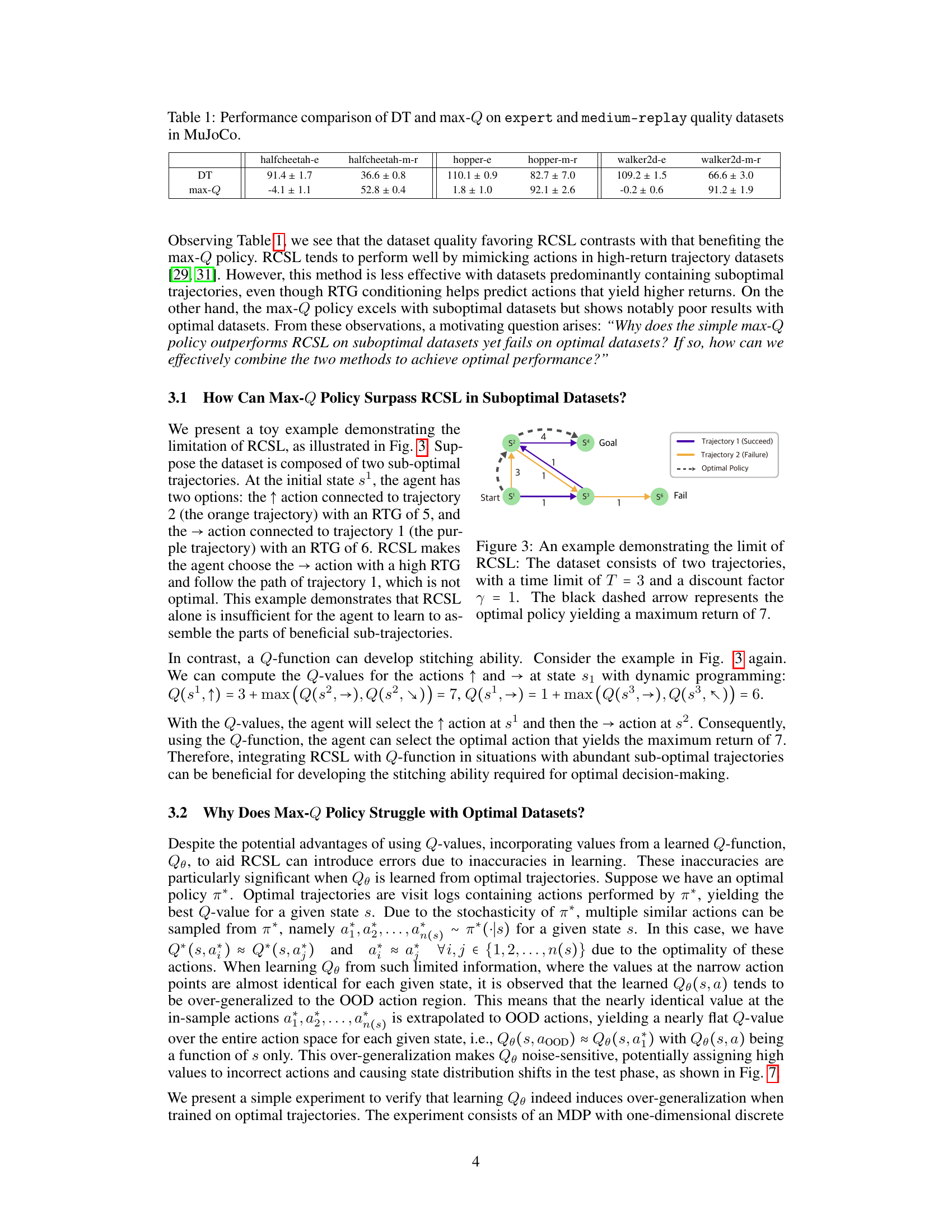

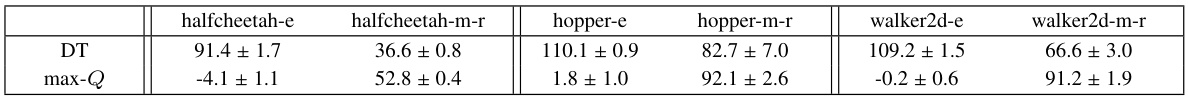

This table compares the performance of the Decision Transformer (DT) algorithm and a max-Q policy on two different quality datasets from the MuJoCo environment in the D4RL benchmark. The expert datasets contain mostly optimal trajectories, while the medium-replay datasets include suboptimal trajectories. The results show that DT performs better on expert datasets, while the max-Q policy performs better on medium-replay datasets. This highlights the strengths and weaknesses of each approach and motivates the need for a combined method that leverages the benefits of both.

In-depth insights#

QCS: Adaptive Aid#

The concept of “QCS: Adaptive Aid” in offline reinforcement learning presents a novel approach to bridge the gap between the stability of return-conditioned supervised learning (RCSL) and the stitching capability of Q-functions. The core idea is to selectively leverage the Q-function (Q-aid) to enhance RCSL’s performance, especially in scenarios involving suboptimal trajectories where RCSL struggles. This adaptive integration is crucial because while Q-functions excel at stitching together suboptimal trajectories, they can suffer from over-generalization when trained on predominantly optimal data, leading to performance degradation. QCS addresses this by dynamically weighting the Q-aid based on the trajectory return, providing a more robust solution that avoids this over-generalization problem. This adaptive weighting scheme is key to the success of QCS, allowing it to achieve or surpass the maximum trajectory returns across various benchmarks, clearly outperforming both RCSL and value-based methods. The thoughtful incorporation of Q-aid based on trajectory performance represents a significant contribution to the field, providing a practical and effective improvement in offline reinforcement learning.

Over-generalization Issue#

The over-generalization issue arises when a Q-function, trained primarily on optimal trajectories, fails to discriminate effectively between actions, leading to inaccurate estimations for out-of-distribution actions. This stems from the limited variation in Q-values observed during training, causing the model to over-generalize learned values across the entire action space. The resulting flat Q-value landscape impairs the stitching capability crucial for combining suboptimal trajectory segments. This phenomenon is particularly problematic in offline reinforcement learning (RL), where interactions are limited, and the model’s ability to correct inaccurate estimations is restricted. Consequently, leveraging the Q-function for stitching in offline RL requires careful consideration of this over-generalization issue. Strategies to mitigate this include employing techniques like implicit Q-learning or datasets with more diverse trajectories, thus ensuring the Q-function generalizes more accurately and facilitates effective stitching without introducing substantial errors.

Offline RL Benchmarks#

Offline Reinforcement Learning (RL) heavily relies on robust benchmarks to evaluate algorithm performance. A comprehensive benchmark suite should encompass diverse environments, reward structures, and dataset characteristics to thoroughly assess an algorithm’s capabilities. Key aspects include the diversity of tasks (e.g., locomotion, manipulation, navigation), the density of rewards (sparse vs. dense), and the degree of sub-optimality in the datasets (expert vs. medium vs. replay). The choice of benchmark tasks directly influences the insights gained. A well-designed benchmark should challenge algorithms’ ability to generalize across different environments and dataset characteristics, pushing the boundaries of current state-of-the-art methods. Furthermore, consideration should be given to the computational cost of evaluating on the benchmark, as this can influence the practicality and scalability of algorithm development and research reproducibility. Finally, the ongoing evolution of offline RL necessitates a continuous update and expansion of benchmarks, incorporating new tasks and data to keep the evaluation process relevant and reflective of the field’s advancement.

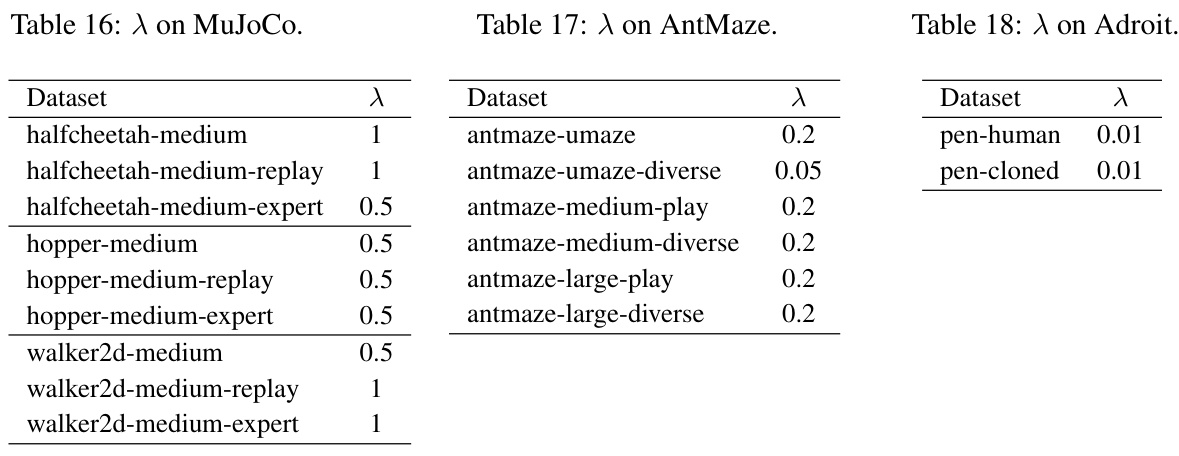

Dynamic QCS Weights#

The concept of “Dynamic QCS Weights” introduces an adaptive weighting mechanism within the QCS (Q-Aided Conditional Supervised Learning) framework for offline reinforcement learning. Instead of a fixed weighting scheme, the weights dynamically adjust based on the trajectory return, reflecting the optimality of the trajectories. This adaptive approach is crucial because it addresses the limitations of both RCSL (Return-Conditioned Supervised Learning) and Q-function based methods. For high-return trajectories, RCSL’s stability is leveraged, while for low-return trajectories, the Q-function’s stitching ability is emphasized. This dynamic weighting elegantly combines the strengths of both methods, leading to more robust and accurate policy learning. The effectiveness of this approach is supported by empirical results showing improved performance across various offline RL benchmarks. The choice of a monotone decreasing function for weight assignment suggests a deliberate design to ensure a smooth transition between prioritizing RCSL and Q-function contributions, although the specific functional form (linear decay in the provided example) could be further explored and potentially optimized.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the adaptive Q-aid mechanism beyond simple linear weighting based on trajectory return is crucial. More sophisticated methods for dynamically adjusting Q-aid, perhaps incorporating contextual information or considering the inherent uncertainty in Q-function estimates, could significantly enhance performance and robustness. Investigating alternative Q-learning methods beyond IQL, and analyzing the interaction between different Q-learning algorithms and RCSL, presents another exciting area. Exploring different conditioning schemes within RCSL itself, or combining multiple conditioning techniques, may unlock further improvements. A deeper investigation into the over-generalization problem of Q-functions, potentially leading to novel regularization techniques, could significantly benefit offline RL. Finally, applying QCS to a broader range of offline RL benchmarks and tasks with diverse characteristics, including those with sparse rewards or high-dimensional state/action spaces, will help further validate its efficacy and establish its generalizability. The success of QCS highlights the value of carefully integrating complementary strengths of different offline RL approaches; this concept should be studied further, perhaps by developing a framework for identifying and combining suitable methods for specific tasks and dataset characteristics.

More visual insights#

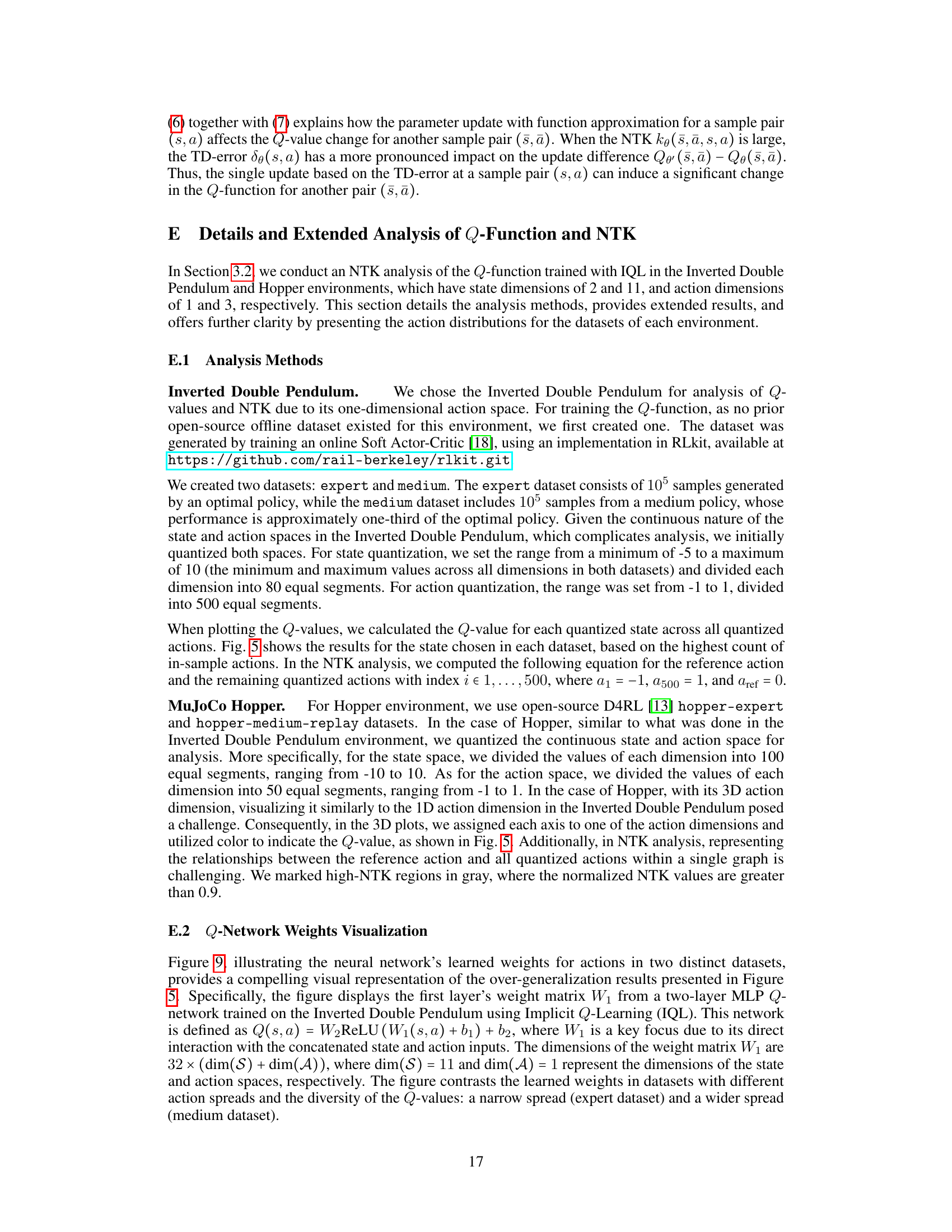

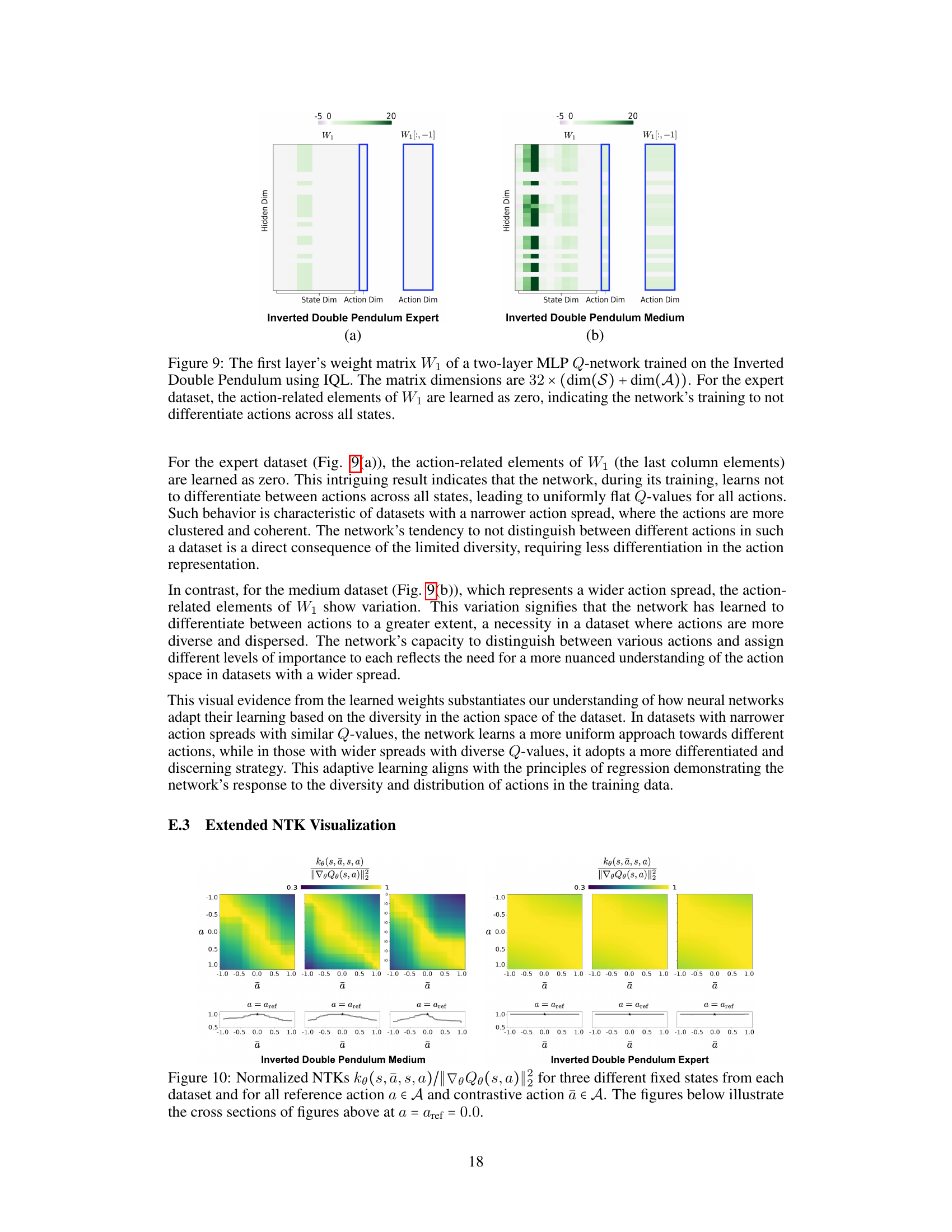

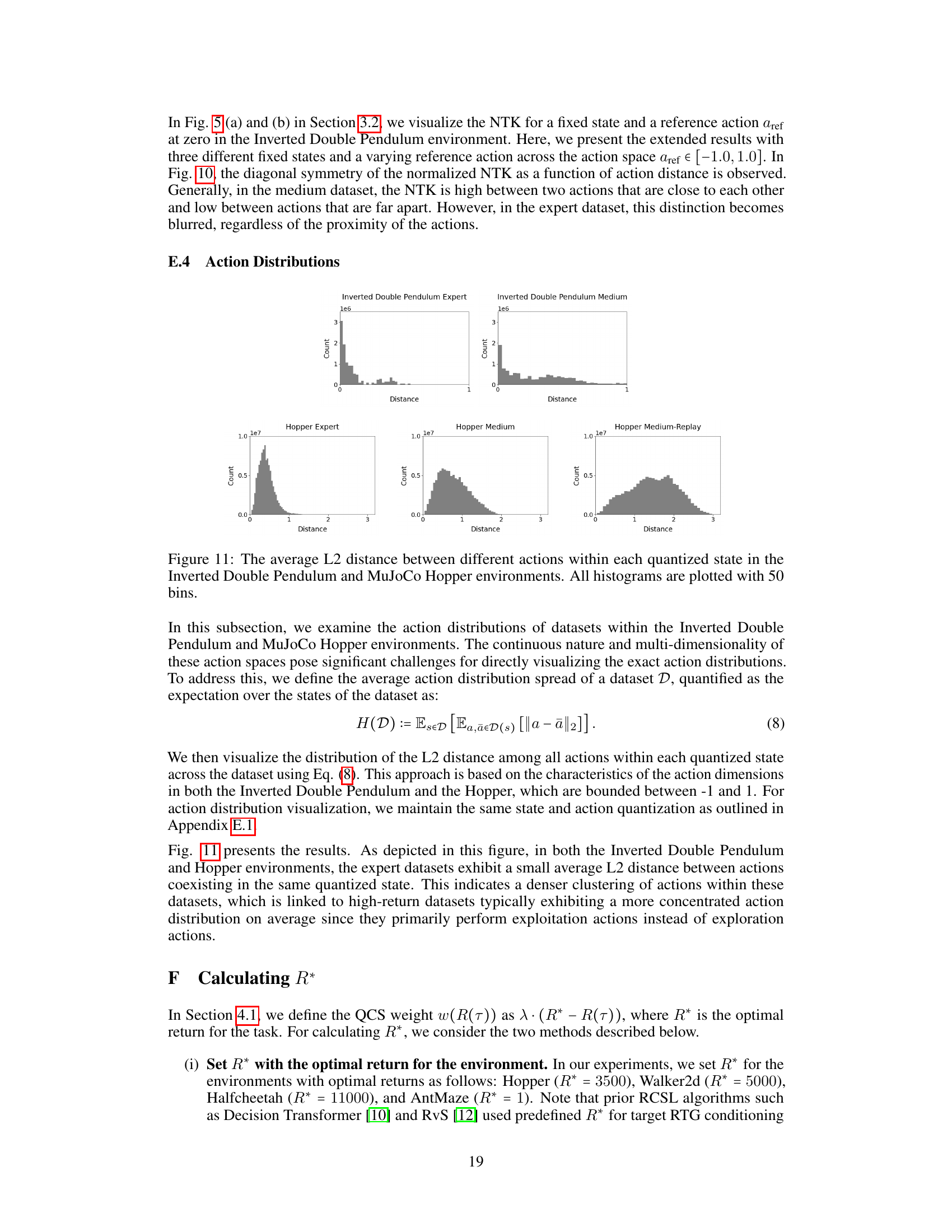

More on figures

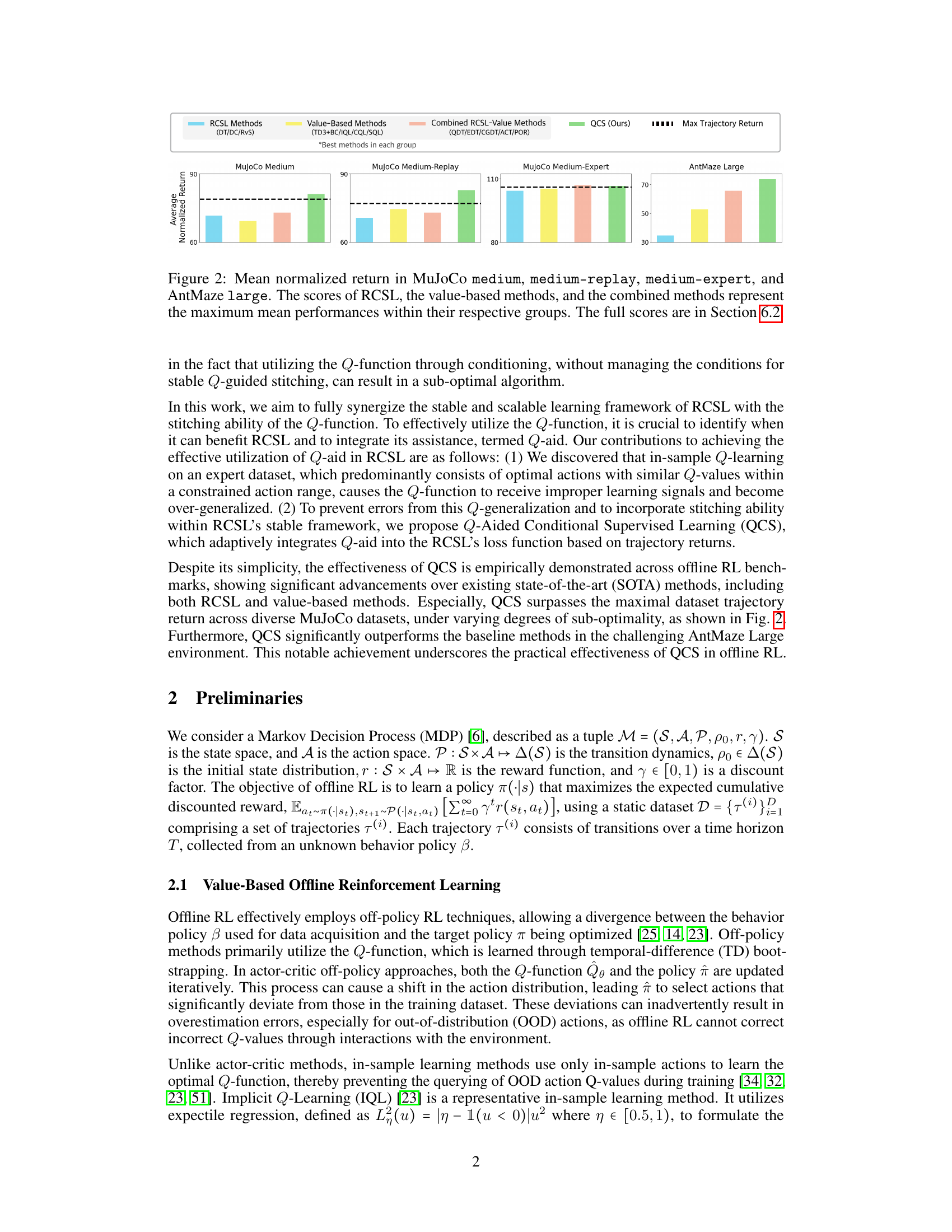

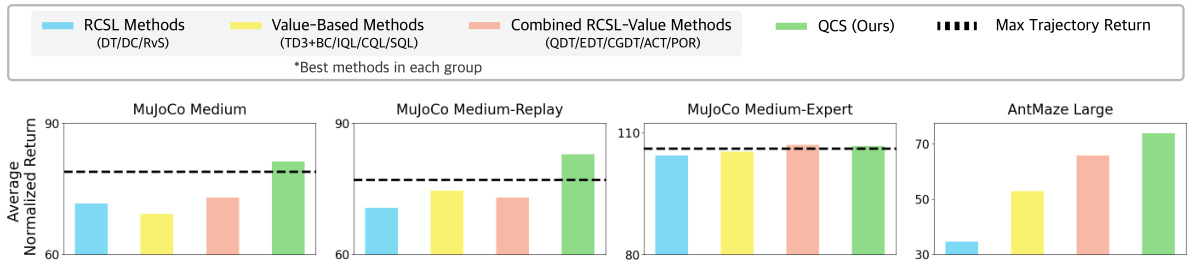

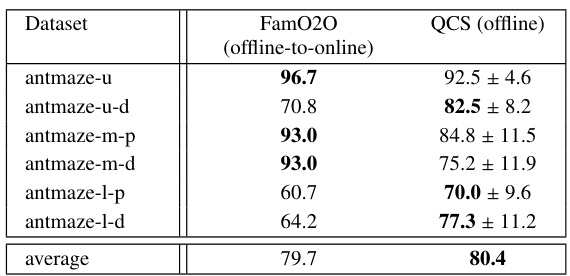

This figure compares the performance of QCS against other state-of-the-art methods across four different environments: MuJoCo medium, MuJoCo medium-replay, MuJoCo medium-expert, and AntMaze large. The results are presented as mean normalized returns, grouped by method type (RCSL, Value-Based, Combined RCSL-Value, and QCS). The maximum mean return achieved within each group is highlighted. The figure shows that QCS consistently outperforms other approaches in most scenarios, often exceeding the maximum return achieved by other methods. Detailed scores for each environment and method are provided in Section 6.2 of the paper.

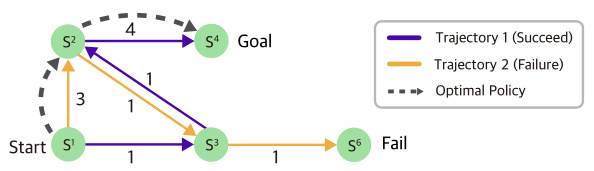

This figure illustrates a simple Markov Decision Process (MDP) with a start state and a goal state. Two trajectories are shown: one successful trajectory with a return of 7 and one unsuccessful trajectory with a return of 6. The optimal policy (dashed arrows) is to go from the start state to the goal state with a return of 7, but because RCSL only considers returns from the provided trajectories, it might choose the suboptimal path with the highest return from the provided trajectories, demonstrating its lack of stitching ability.

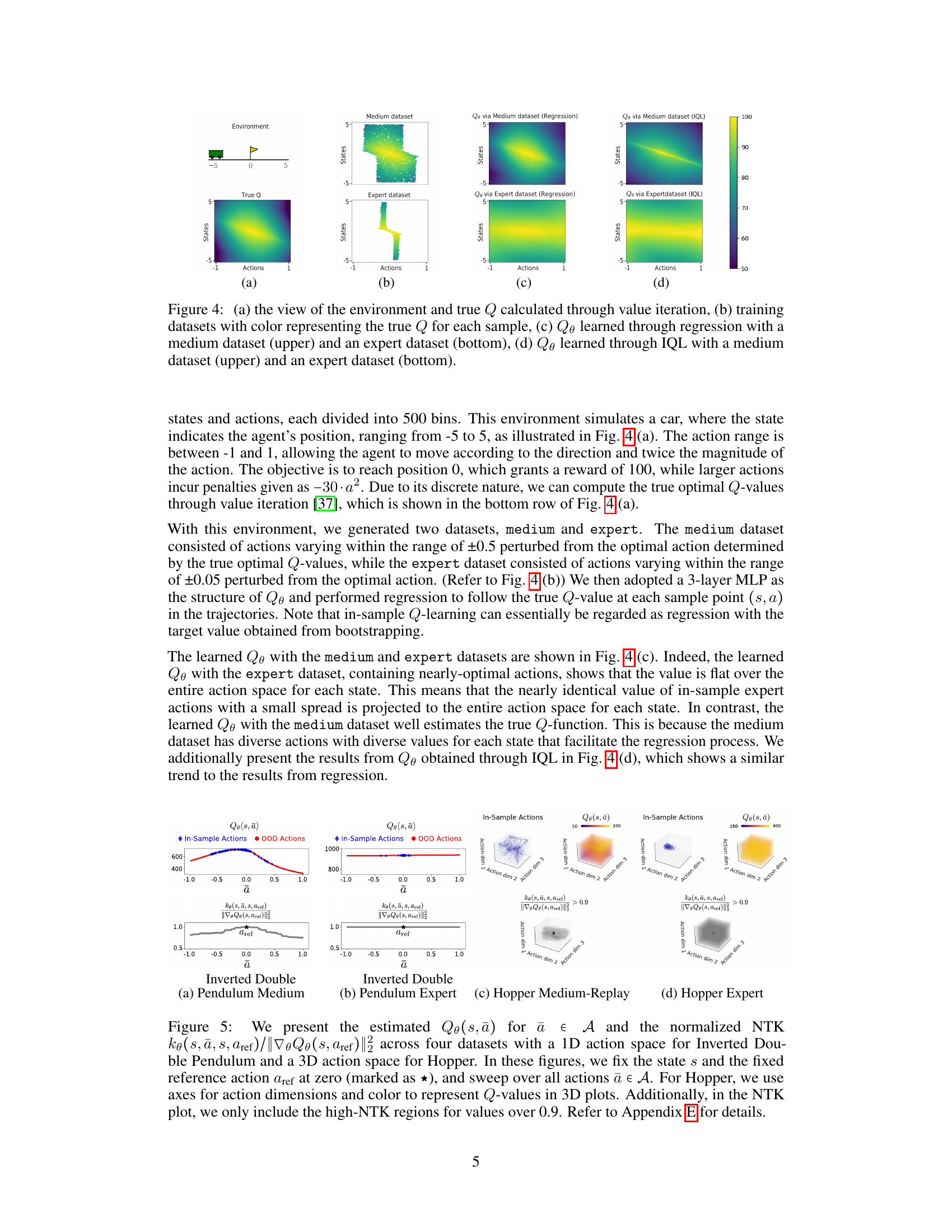

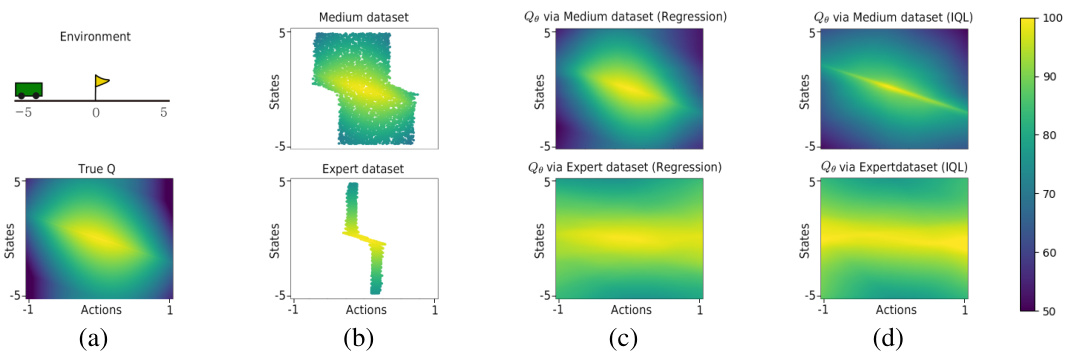

This figure shows a visualization of the learned Q-function (Qe) in a simple environment with discrete states and actions. Panel (a) displays the environment and the true Q-values obtained through value iteration. Panels (b) show the training datasets, where color intensity represents the true Q-value for each data point. Panels (c) and (d) compare the learned Qe using regression and IQL, respectively, trained on both a medium-quality dataset (containing a mix of near-optimal and suboptimal actions) and an expert dataset (containing mostly near-optimal actions). The figure highlights the over-generalization effect observed when the Q-function is trained on the expert dataset, showing a flattened Qe, which contrasts with the more accurate Qe learned from the medium dataset.

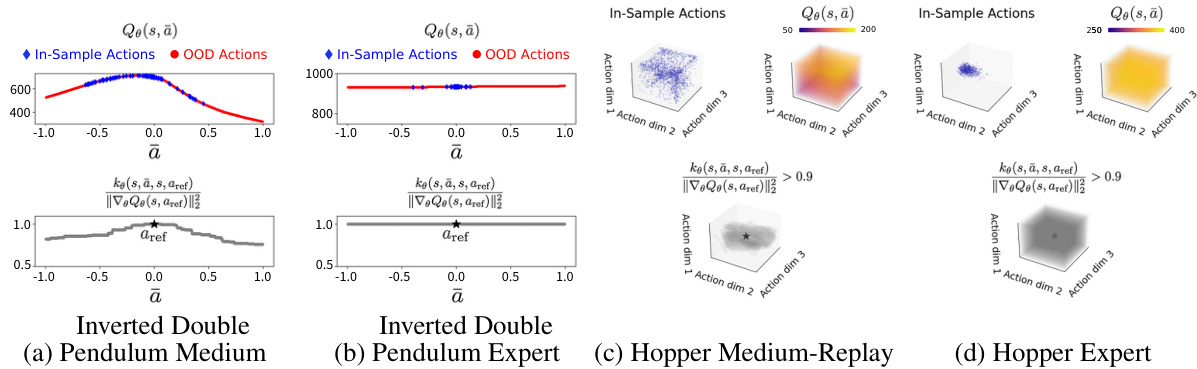

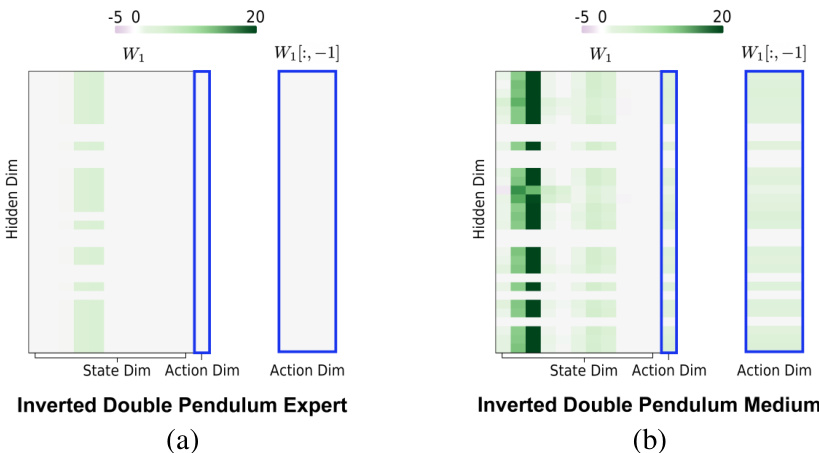

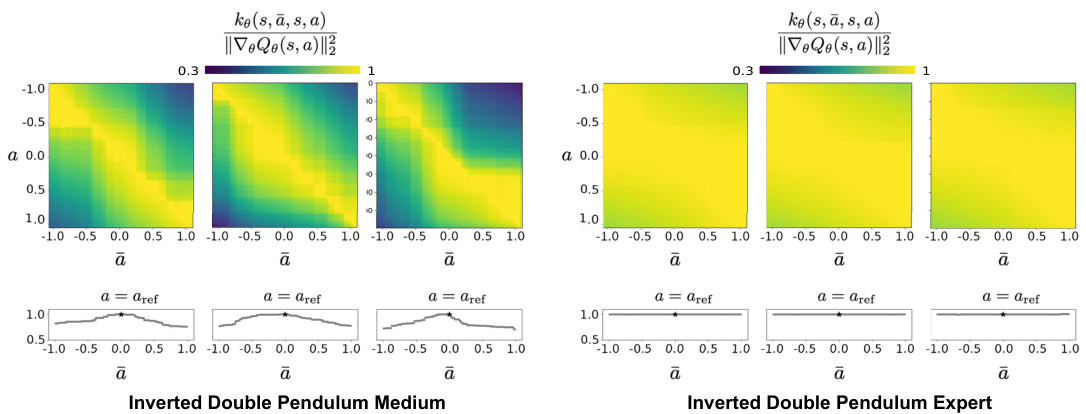

This figure visualizes the learned Q-function (Qe) and the Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK) for four different datasets: Inverted Double Pendulum Medium, Inverted Double Pendulum Expert, Hopper Medium-Replay, and Hopper Expert. It shows how the Q-function and NTK vary across the action space, illustrating the over-generalization phenomenon observed in the expert dataset where the Q-function becomes nearly flat due to limited action diversity.

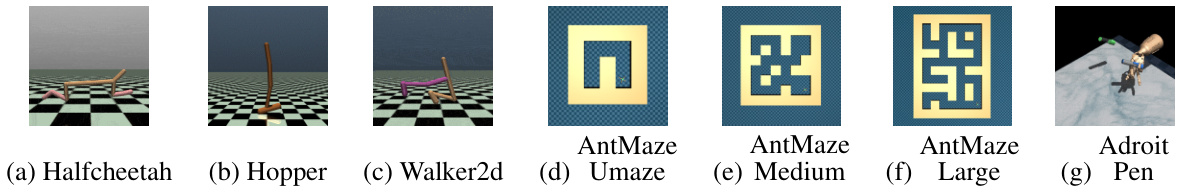

This figure shows screenshots of the seven different tasks used in the paper’s experiments. The tasks represent a variety of challenges in offline reinforcement learning, including continuous control (Halfcheetah, Hopper, Walker2d), sparse rewards (AntMaze), and complex manipulation (Adroit). The AntMaze environments showcase different map complexities and sizes. The variety of tasks demonstrates the broad applicability and effectiveness of the proposed QCS algorithm across diverse offline RL benchmarks.

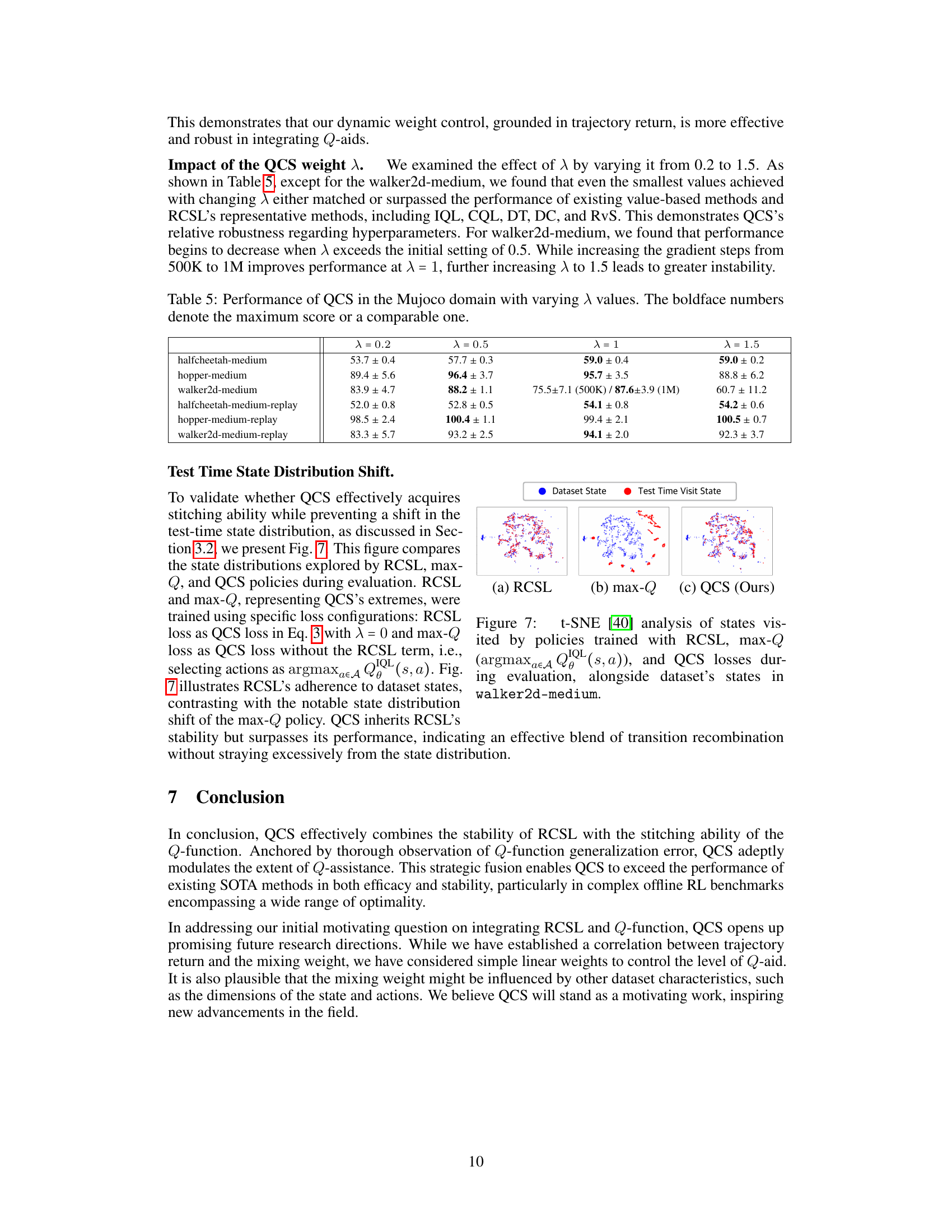

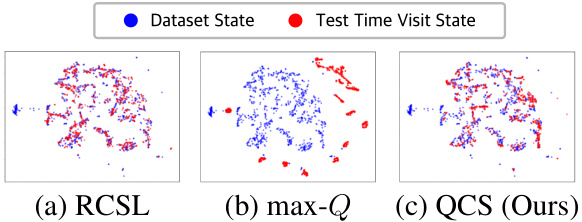

This figure compares the state distributions explored by RCSL, max-Q, and QCS policies during evaluation. RCSL and max-Q represent the extremes of QCS. RCSL’s adherence to dataset states is shown, contrasting with the state distribution shift of max-Q. QCS inherits RCSL’s stability but surpasses its performance, indicating a blend of transition recombination without straying from the state distribution.

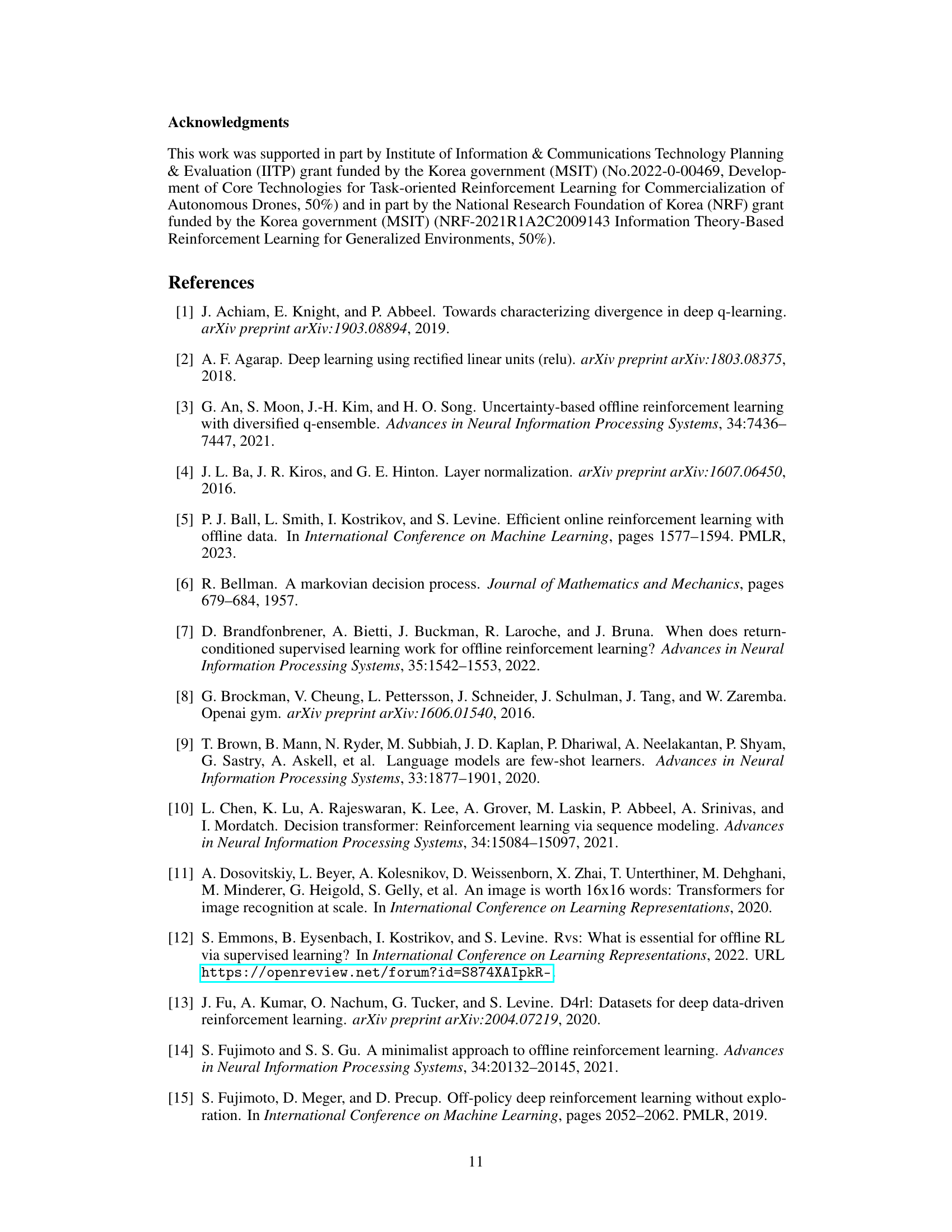

This figure shows the distribution of trajectory returns for different datasets in the MuJoCo environment. Each dataset (medium, medium-replay, medium-expert for each of the three tasks: Halfcheetah, Hopper, Walker2d) is represented by a histogram showing the frequency of different trajectory returns. Vertical lines indicate the maximum trajectory return observed in each dataset, and the score achieved by the QCS algorithm. The figure helps illustrate the differences in dataset quality and how QCS performs relative to the best possible outcome.

This figure visualizes the results of an experiment designed to demonstrate the over-generalization of the Q-function when trained on optimal trajectories. Panel (a) shows the environment and the true Q-values calculated using value iteration. Panel (b) displays the training datasets used, with color-coding representing the true Q-value for each sample. Panels (c) and (d) present the learned Q-functions (Qe) obtained using regression and IQL, respectively. The upper row shows results using a medium dataset, and the bottom row displays results from an expert dataset. This comparison highlights how the Q-function trained on the expert dataset exhibits over-generalization, resulting in a flat Q-value across the action space.

This figure shows the learned Q-function (Qe) and its Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK) for different datasets. The 1D action space plots (Inverted Double Pendulum) show Qe values as a function of actions (ā) while fixing the state (s) and a reference action (aref). The 3D action space plots (Hopper) visualize Qe values using color for the three dimensions of action. The NTK plots demonstrate the influence of updating the Q-function for one action-state pair on other pairs. High NTK values indicate strong overgeneralization of the Q-function, particularly visible in the expert dataset.

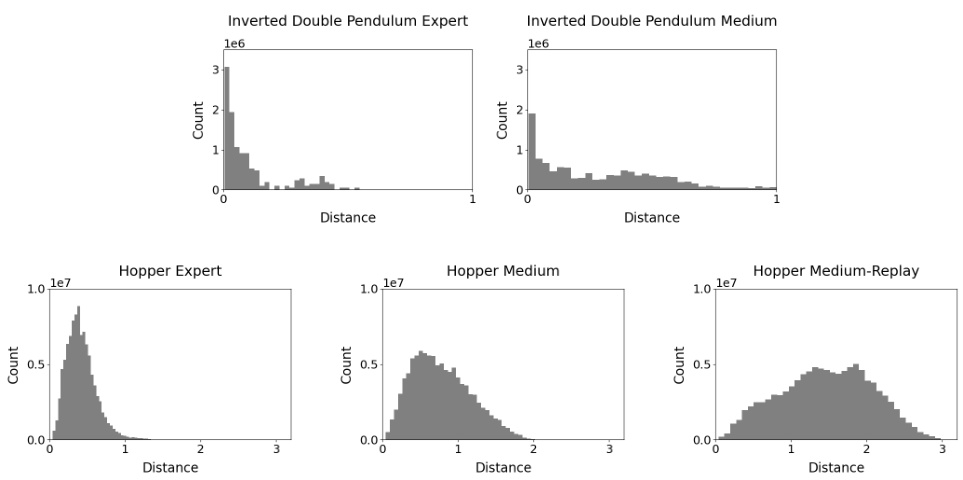

This figure shows the distribution of the L2 distances between actions within each quantized state for the Inverted Double Pendulum and Hopper environments. Separate histograms are shown for the expert, medium, and medium-replay datasets. The expert datasets show a more concentrated distribution of actions, indicating that optimal policies tend to select actions within a narrower range. In contrast, suboptimal datasets show a wider spread of actions.

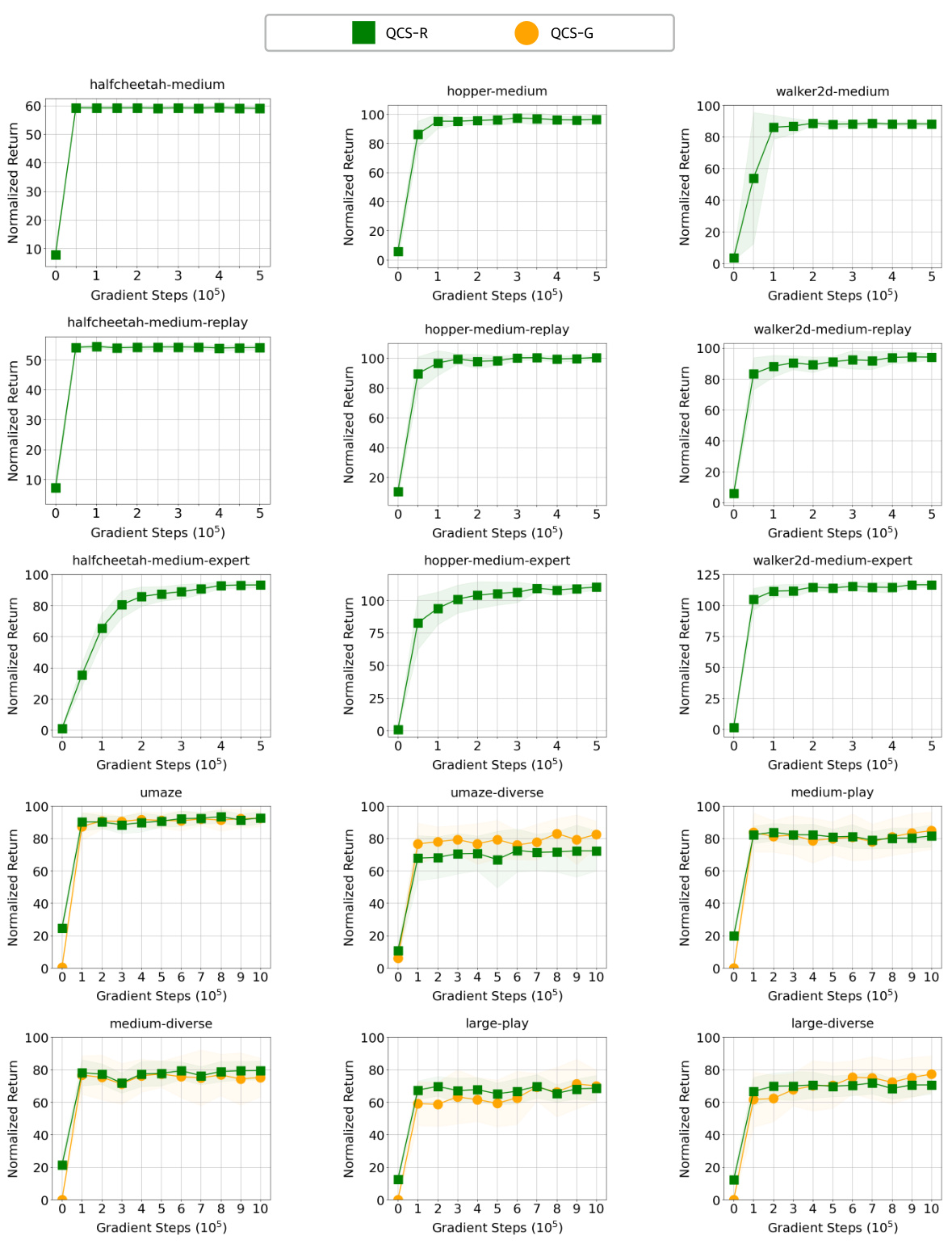

This figure presents the training curves for both QCS-R (return-maximizing tasks) and QCS-G (goal-reaching tasks) across various MuJoCo and AntMaze environments. The x-axis represents the gradient steps (in powers of 10), and the y-axis displays the normalized return. The curves show the performance trends for each algorithm during training across different datasets. The shaded regions likely represent confidence intervals or standard deviations. This helps visualize the stability and convergence of the QCS algorithms in different environments and tasks, showcasing their learning performance.

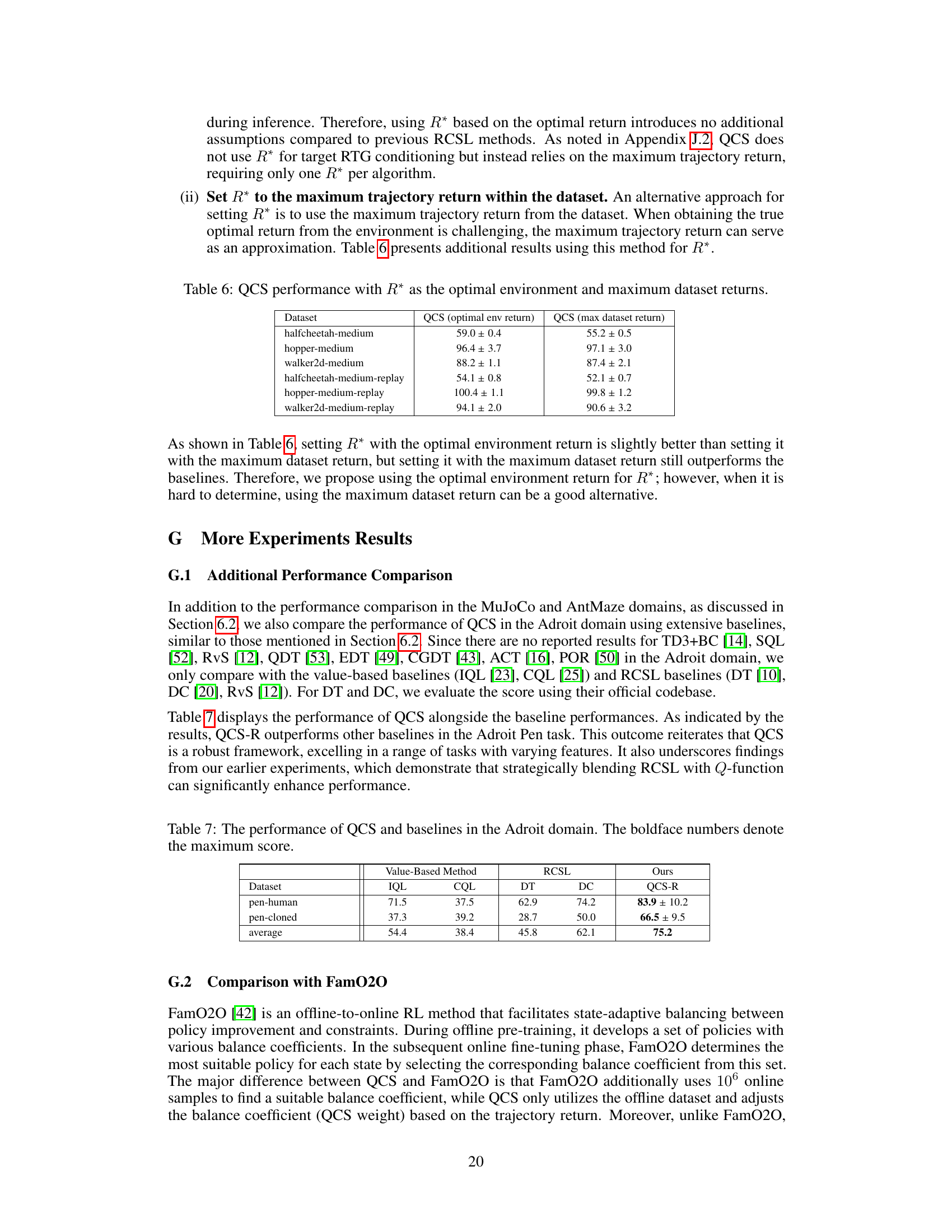

More on tables

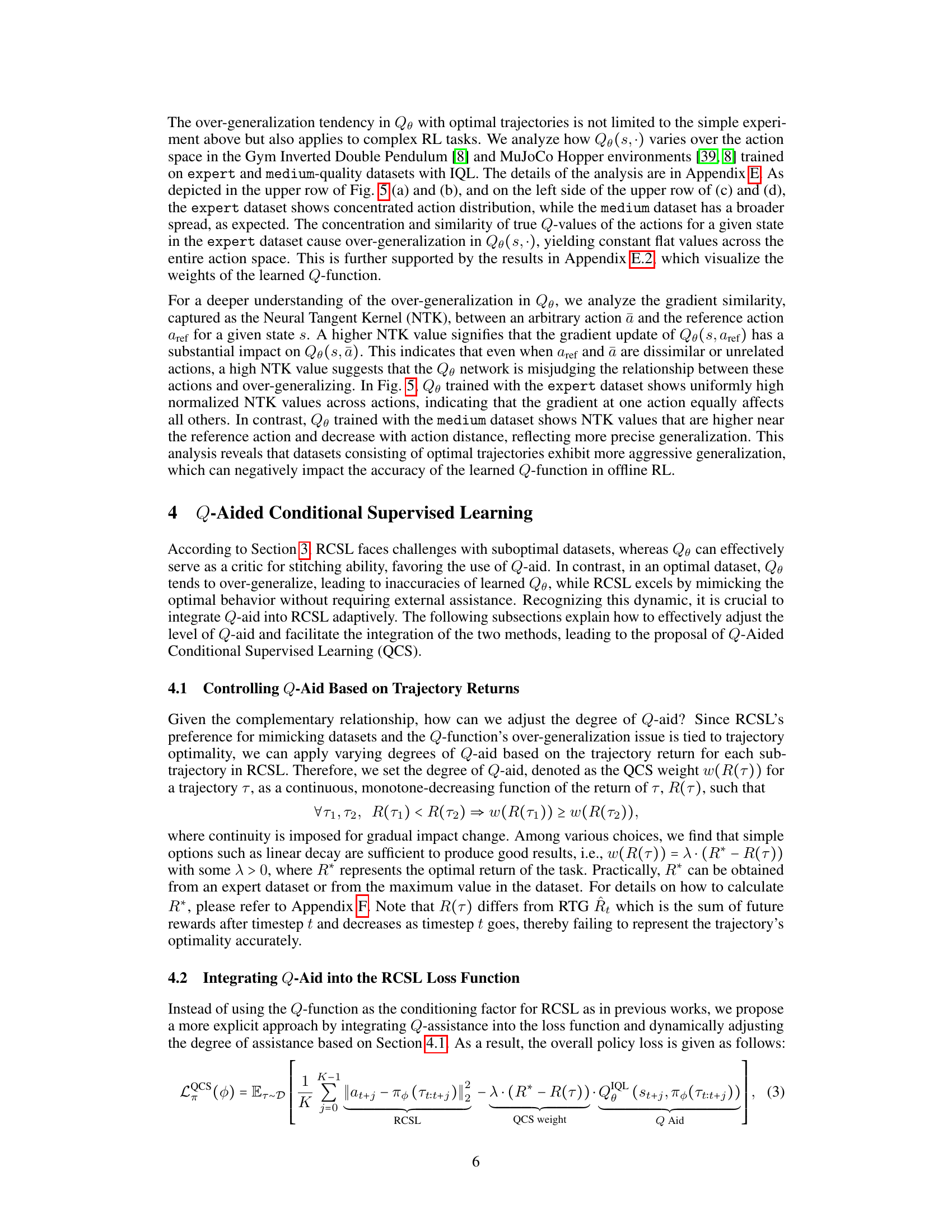

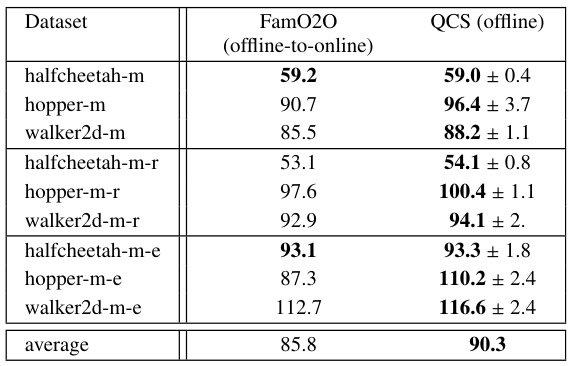

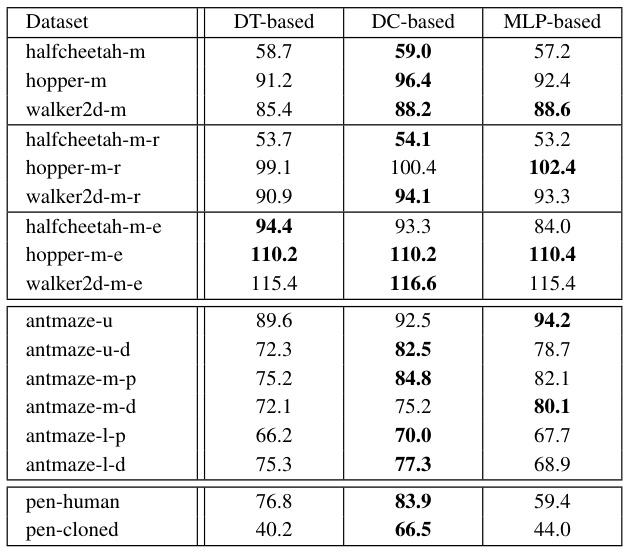

This table presents a comparison of the performance of QCS against various baseline methods across different datasets in the MuJoCo domain. The datasets vary in quality, ranging from medium (m) to medium-replay (m-r) and medium-expert (m-e). The table shows the mean normalized return for each method on each dataset. Boldface numbers indicate the top-performing method for each dataset.

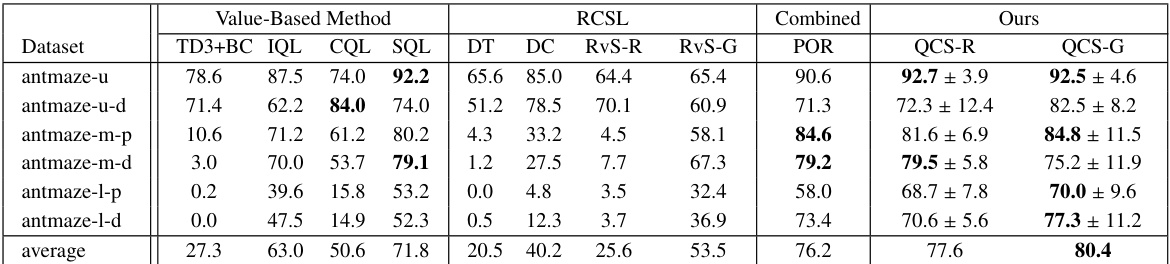

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the QCS algorithm against 12 state-of-the-art baseline methods across six different AntMaze environments. Each environment varies in terms of map size (umaze, medium, large) and data diversity (play, diverse). The table shows the mean normalized returns for each algorithm and environment, with the maximum return (or a comparable value) bolded for easier comparison. The results highlight QCS’s superiority in goal-reaching tasks with varying levels of sub-optimality.

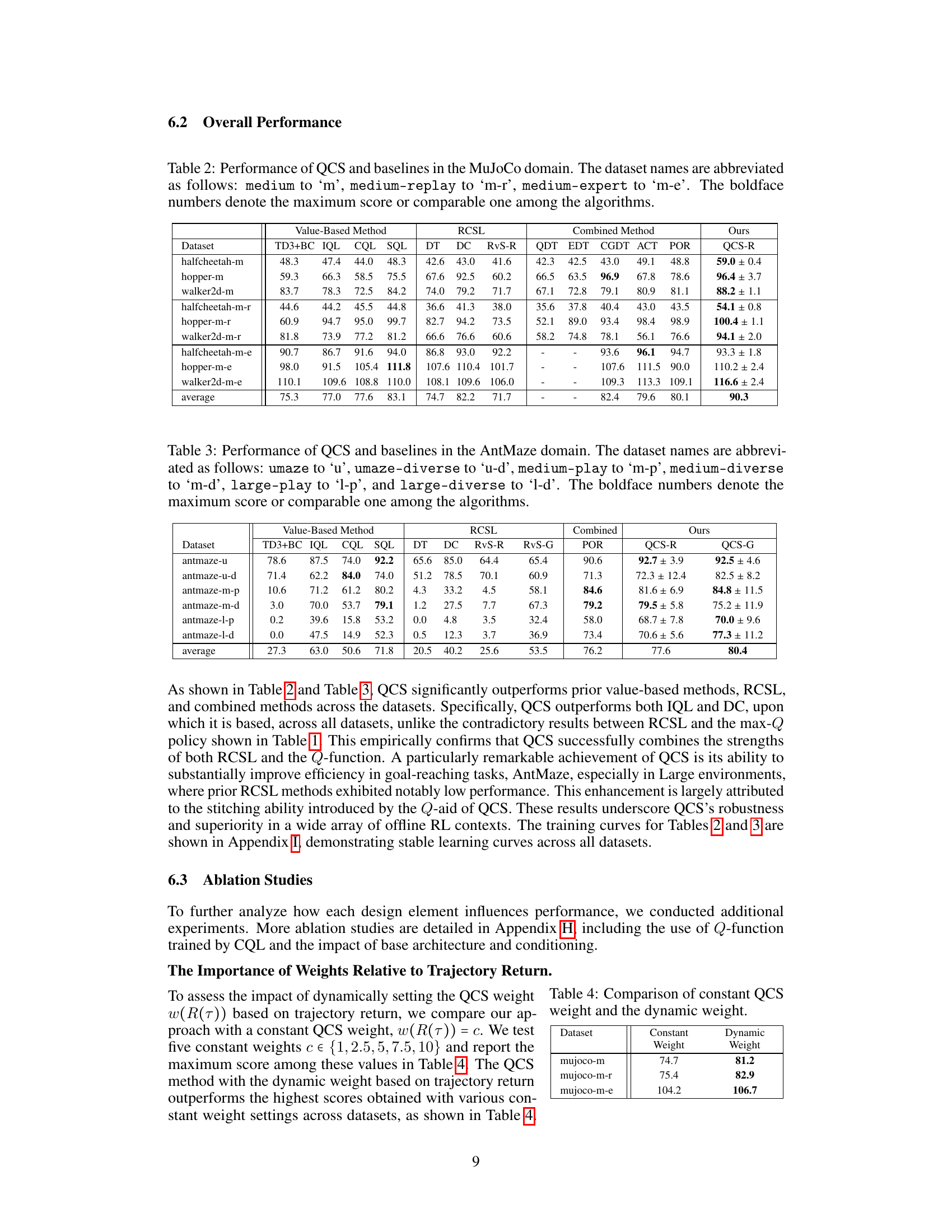

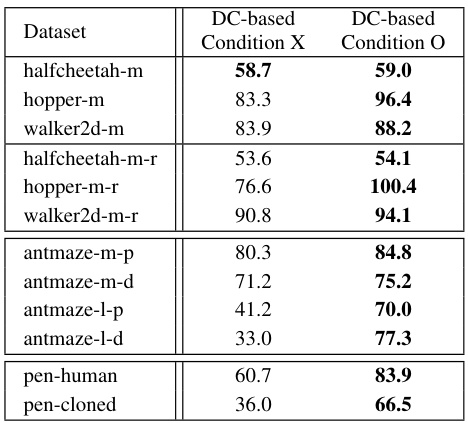

This table compares the performance of QCS using a constant weight versus a dynamic weight that adapts to the trajectory return. It shows that the dynamic weight consistently outperforms the best constant weight across various datasets, highlighting the effectiveness of QCS’s adaptive weighting mechanism.

This table presents the performance of the QCS algorithm across different MuJoCo datasets, varying the hyperparameter λ. The results show the mean normalized return and standard deviation over five random seeds. The purpose is to demonstrate QCS’s performance robustness across different settings and to evaluate its sensitivity to the λ hyperparameter. The bold numbers indicate the best performance for each dataset.

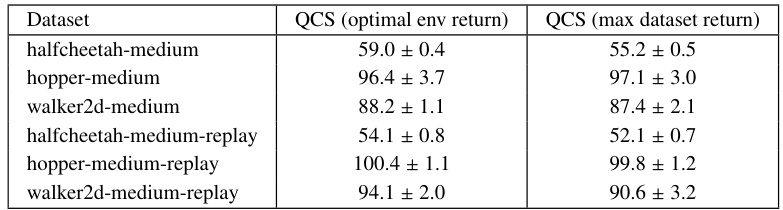

This table compares the performance of QCS using two different methods for determining R*, the optimal return for the environment. The first method uses the actual optimal return from the environment, while the second uses the maximum return observed within the dataset. The table shows the mean ± standard deviation of the normalized returns for various tasks in the MuJoCo dataset. This comparison helps to assess the robustness of QCS to different methods of estimating the optimal return.

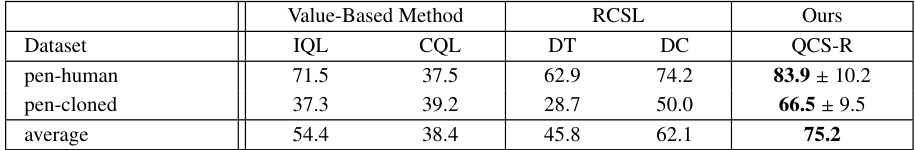

This table compares the performance of QCS against various baseline methods in the Adroit domain, specifically focusing on the ‘pen’ task. It shows the mean normalized returns for IQL, CQL (value-based methods), DT, DC (RCSL methods), and QCS-R (the proposed method). The boldfaced numbers highlight the best-performing method for each dataset (pen-human and pen-cloned). The average performance across both datasets is also provided.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of QCS against various baseline methods across different datasets in the MuJoCo domain. The datasets vary in quality (medium, medium-replay, medium-expert). The table shows the mean normalized return for each method and dataset, highlighting the best-performing method(s) in bold. It offers a quantitative assessment of QCS’s performance relative to existing state-of-the-art (SOTA) offline RL methods, in the context of a return-maximization task.

This table presents a performance comparison of the proposed QCS algorithm against various baselines on different AntMaze datasets. The datasets vary in size and the difficulty of the tasks. The boldfaced numbers highlight the best-performing algorithm for each dataset. The results showcase QCS’s performance against value-based methods, return-conditioned supervised learning (RCSL) methods, and combined RCSL-value methods.

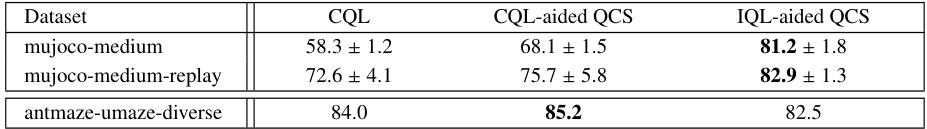

This table compares the performance of three different methods: CQL, CQL-aided QCS, and IQL-aided QCS, across three different datasets: mujoco-medium, mujoco-medium-replay, and antmaze-umaze-diverse. The results show the mean and standard deviation of the performance for each method on each dataset. This table demonstrates the effect of using different Q-function training methods (CQL vs. IQL) within the QCS framework.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of the proposed QCS algorithm against various baseline methods across different MuJoCo datasets. The datasets vary in quality (’m’ for medium, ’m-r’ for medium-replay, ’m-e’ for medium-expert), representing different levels of data optimality. The table shows the mean normalized return for each algorithm on each dataset. Boldface numbers highlight the top-performing algorithm for each dataset. The results demonstrate QCS’s performance relative to other value-based methods, RCSL methods, and combined RCSL-value methods.

This table compares the performance of QCS using three different base architectures (DT, DC, and MLP) and with and without conditioning. The results show the impact of architecture choice and the benefit of conditioning, especially on more complex tasks and datasets with variable optimality.

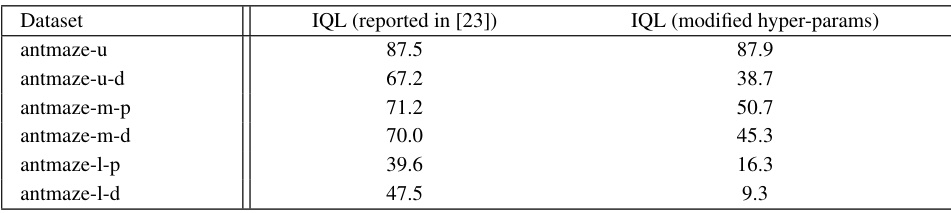

This table compares the performance of Decision Transformer (DT), a return-conditioned supervised learning method, and a max-Q policy (selecting actions that maximize the Q-function) on two datasets of different qualities: expert and medium-replay. The results are presented for three MuJoCo environments: halfcheetah, hopper, and walker2d. The table highlights the contrasting performances of DT and max-Q across dataset types, motivating the need for an approach that can adaptively leverage the strengths of both methods.

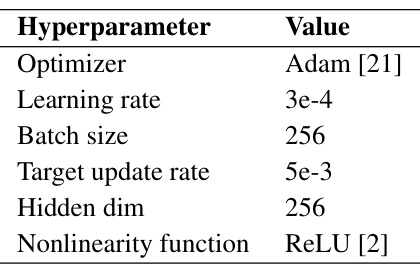

This table compares the performance of Implicit Q-Learning (IQL) as reported in the original IQL paper [23] with the performance achieved using modified hyperparameters in this paper. The modified hyperparameters were used to train the Q-function for QCS (Q-Aided Conditional Supervised Learning) and include changes to the expectile, Layer Normalization, and discount factor. The comparison highlights the effect of these modifications on IQL performance across different AntMaze datasets. Note that the modified hyperparameters negatively impacted IQL performance, hence the results from the original IQL paper were used in Table 3 of the main text.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the policy in QCS experiments using two different RCSL base architectures: Decision Transformer (DT) and Decision Convformer (DC). The hyperparameters are specified for each of the three domains used in the experiments: MuJoCo, AntMaze, and Adroit. The parameters shown include the hidden dimension size of the networks, the number of layers in the networks, batch size for training, and the learning rate.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the policy in the DT-based and DC-based versions of the QCS algorithm. Different hyperparameters were used for the MuJoCo, AntMaze, and Adroit domains, reflecting the varying complexity and characteristics of each environment. The hyperparameters include the hidden dimension, number of layers, batch size, and learning rate.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of QCS (the proposed algorithm) against twelve baseline methods across various MuJoCo datasets. The baselines cover value-based methods, return-conditioned supervised learning (RCSL) methods, and combined methods that incorporate stitching abilities. Datasets vary in their level of optimality (medium, medium-replay, medium-expert) representing different data quality levels. The boldface numbers highlight the top-performing algorithm for each dataset.

Full paper#