↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current text-to-video models struggle to produce high-quality videos that accurately reflect input text prompts due to limitations in training data and reward models. Manually annotating video preference data is expensive and time-consuming, hindering progress. This research tackles this issue by exploring the use of Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) for creating a large-scale video preference dataset.

The researchers utilized MLLMs to create VIDEOPREFER, a dataset comprising 135,000 preference annotations across two dimensions (Prompt-Following and Video Quality). Building upon VIDEOPREFER, they developed VIDEORM, a general-purpose reward model specifically designed for video preference in the text-to-video domain. The model is tailored to capture temporal information, enhancing quality assessment. Experiments confirmed the effectiveness of VIDEOPREFER and VIDEORM, representing a significant step forward in the field, leading to improved generation quality and alignment.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in text-to-video generation because it introduces a novel approach to improve the quality and alignment of generated videos with textual prompts. By utilizing large language models for annotation and developing a new reward model, the research addresses the limitations of current methods and opens new avenues for enhancing video generation quality. This is highly relevant given the increasing interest in high-fidelity video generation and the need for more efficient and effective training methods.

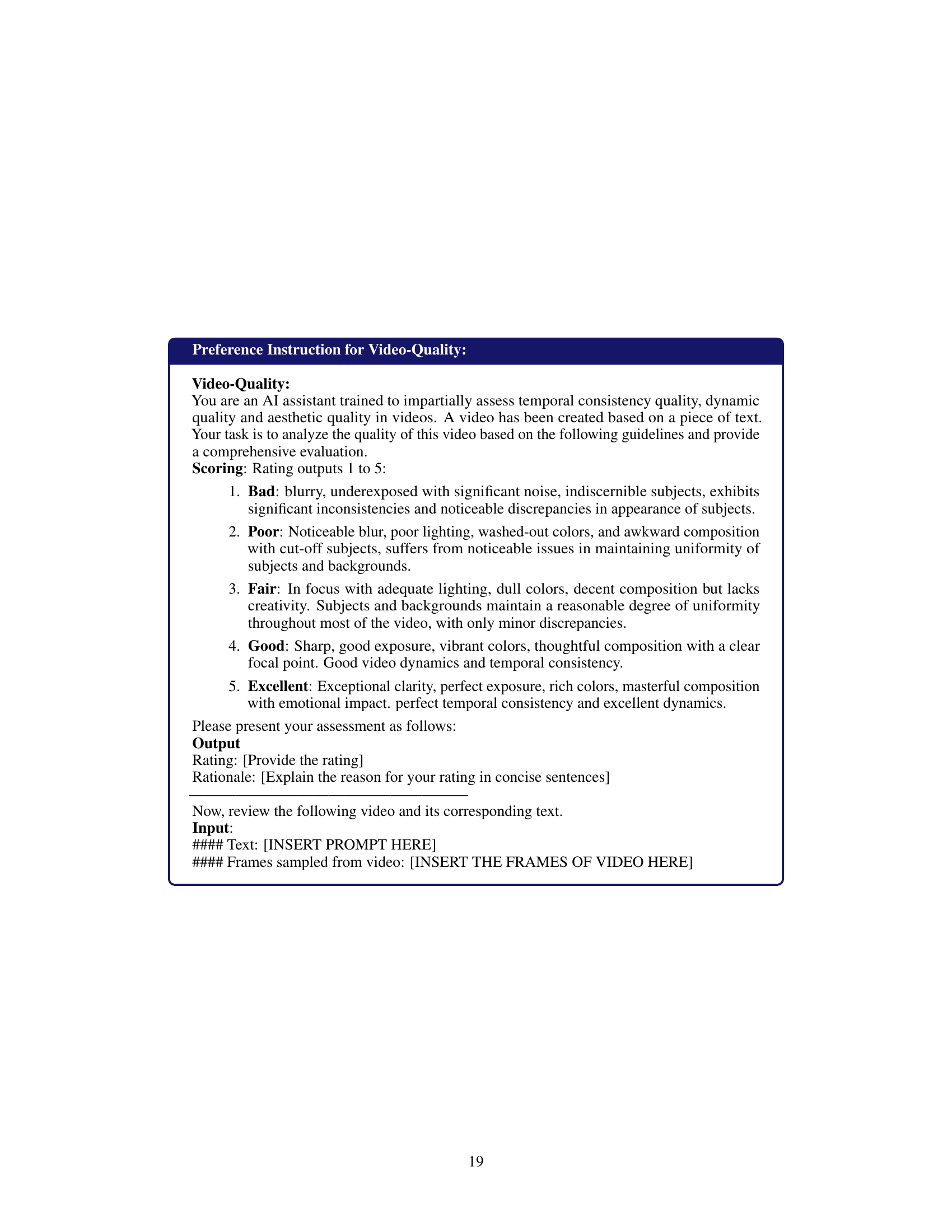

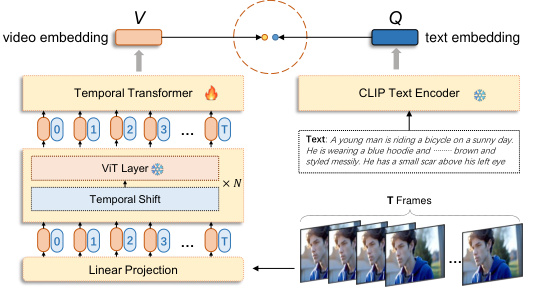

Visual Insights#

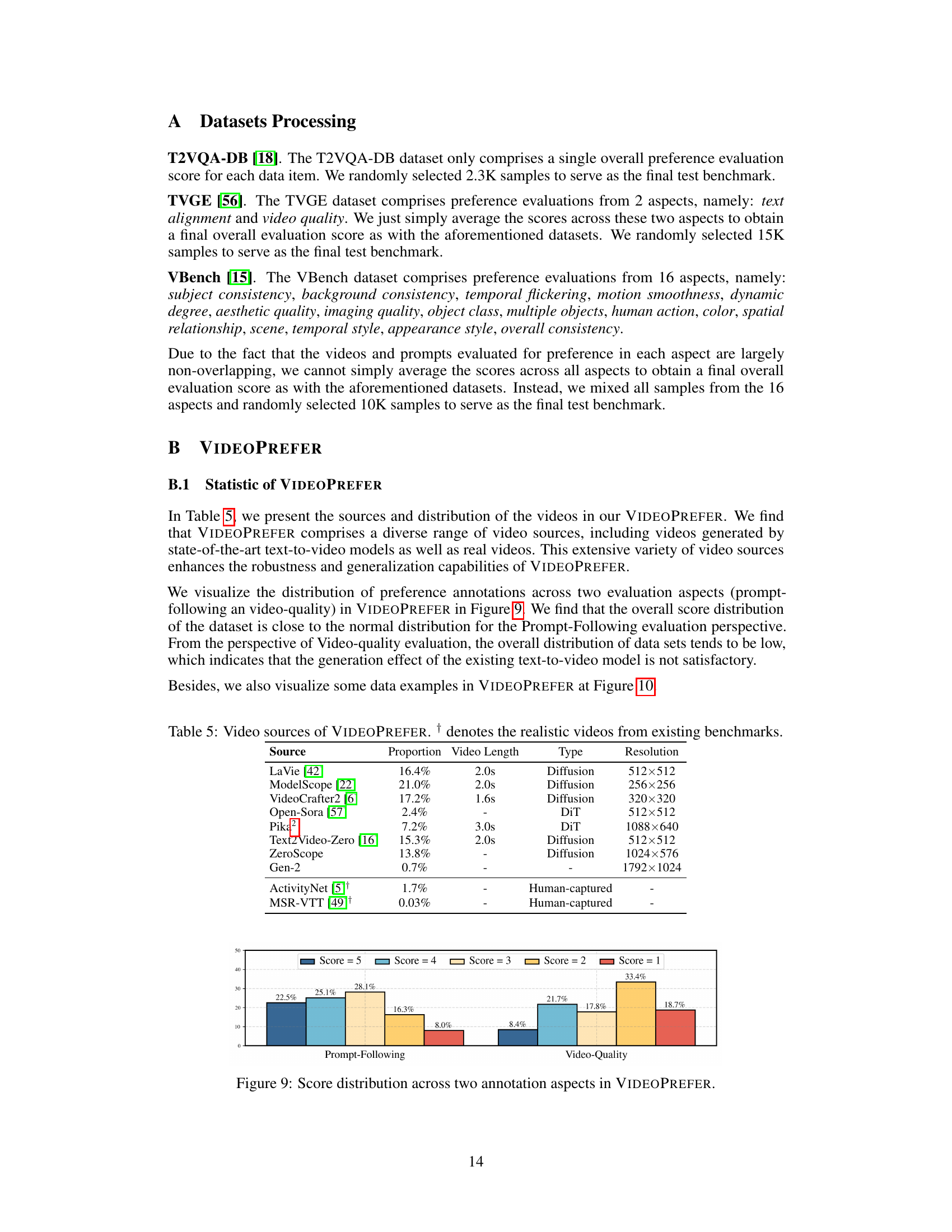

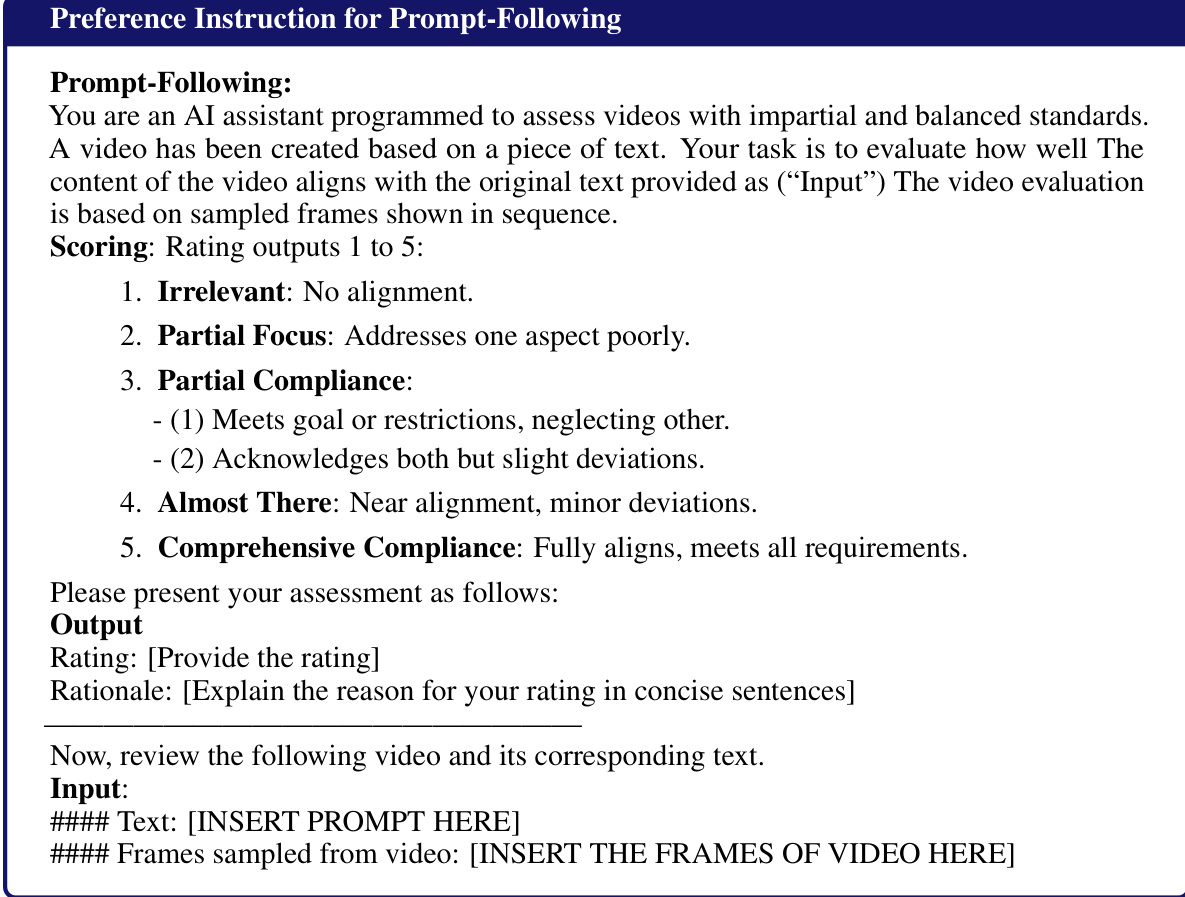

This figure illustrates the architecture of VIDEORM, a video preference reward model. It shows how the model combines a text encoder (CLIP Text Encoder) with an image encoder that processes video frames (using ViT layers and Temporal Shift). A Temporal Transformer module is included to model temporal dynamics in videos. The model ultimately outputs a scalar value representing the overall preference score, integrating both individual frame quality and temporal coherence.

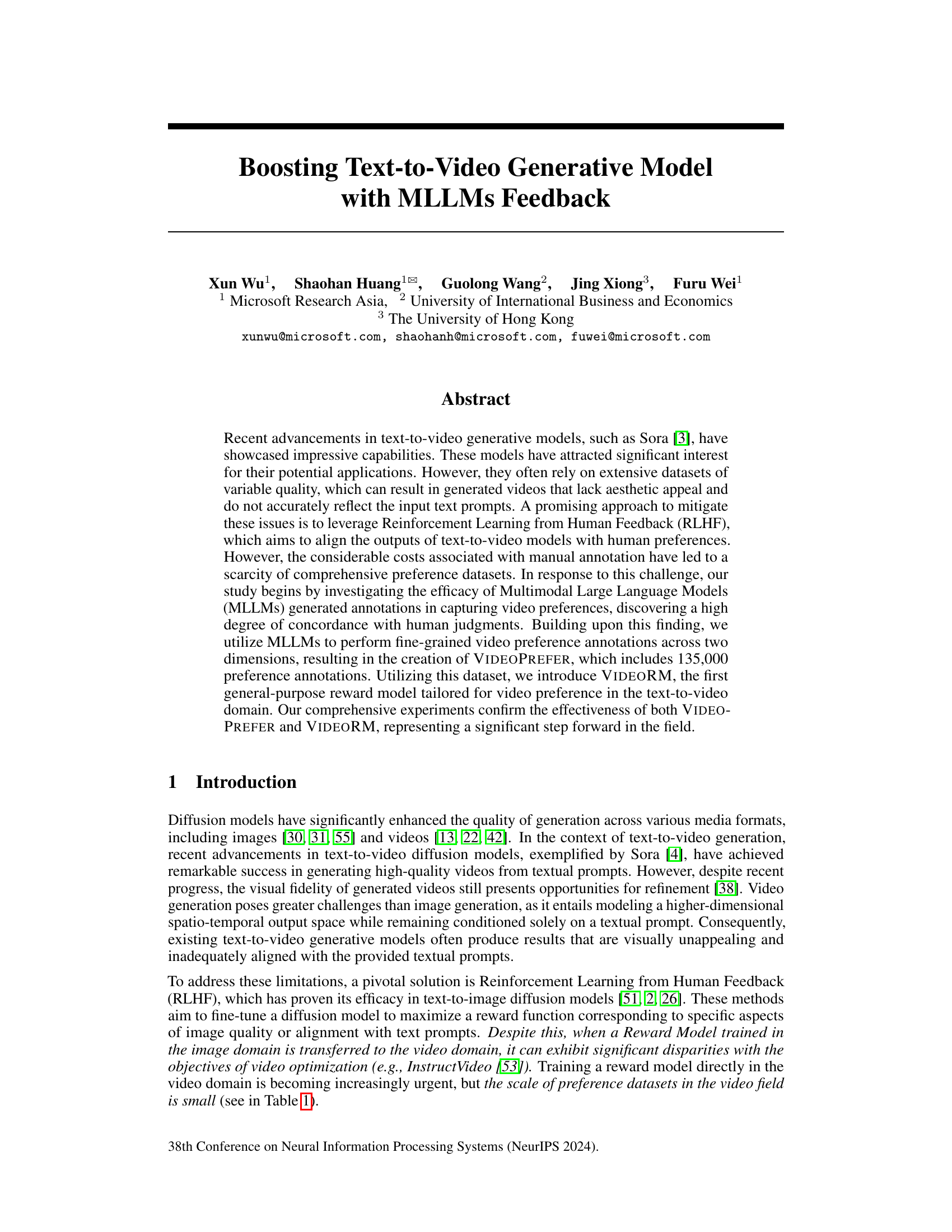

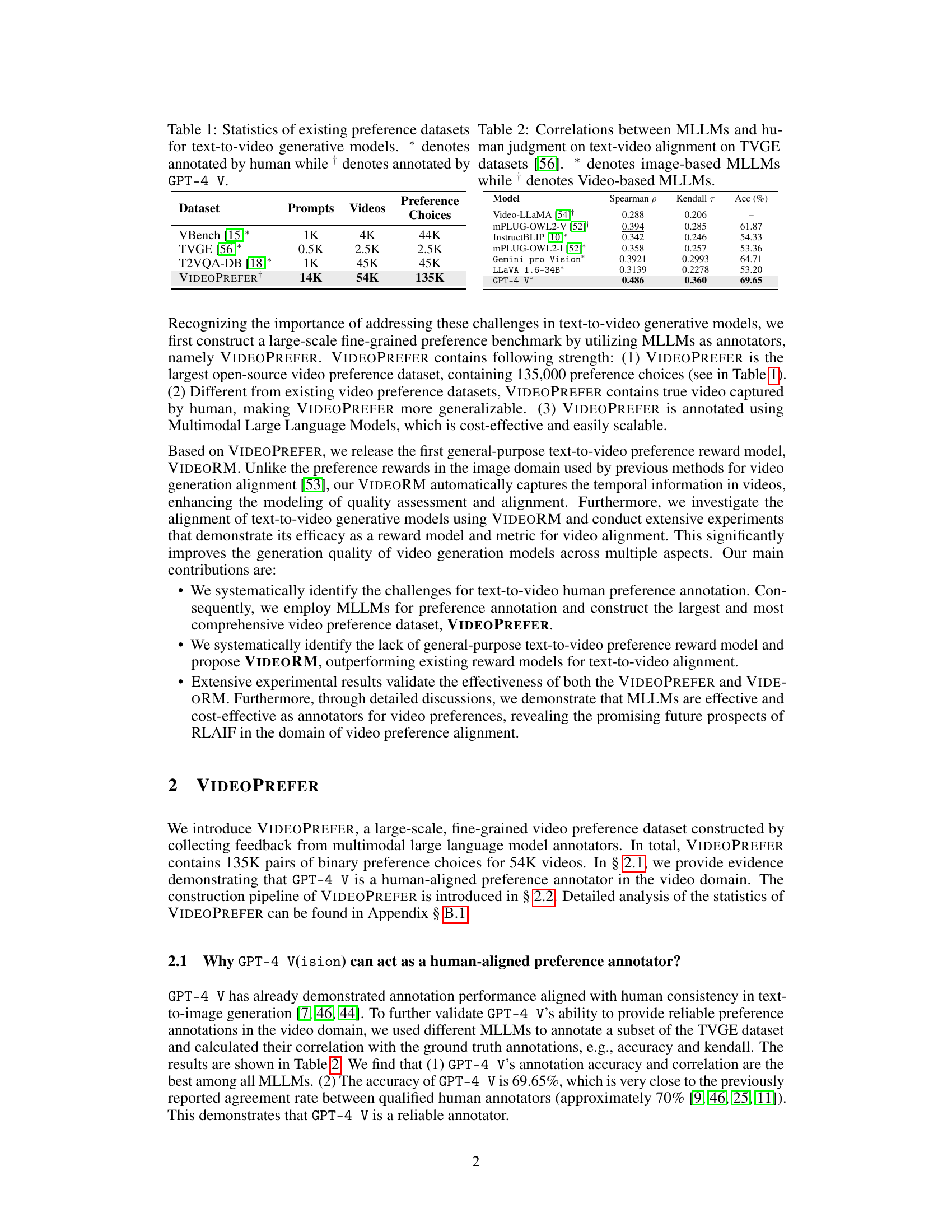

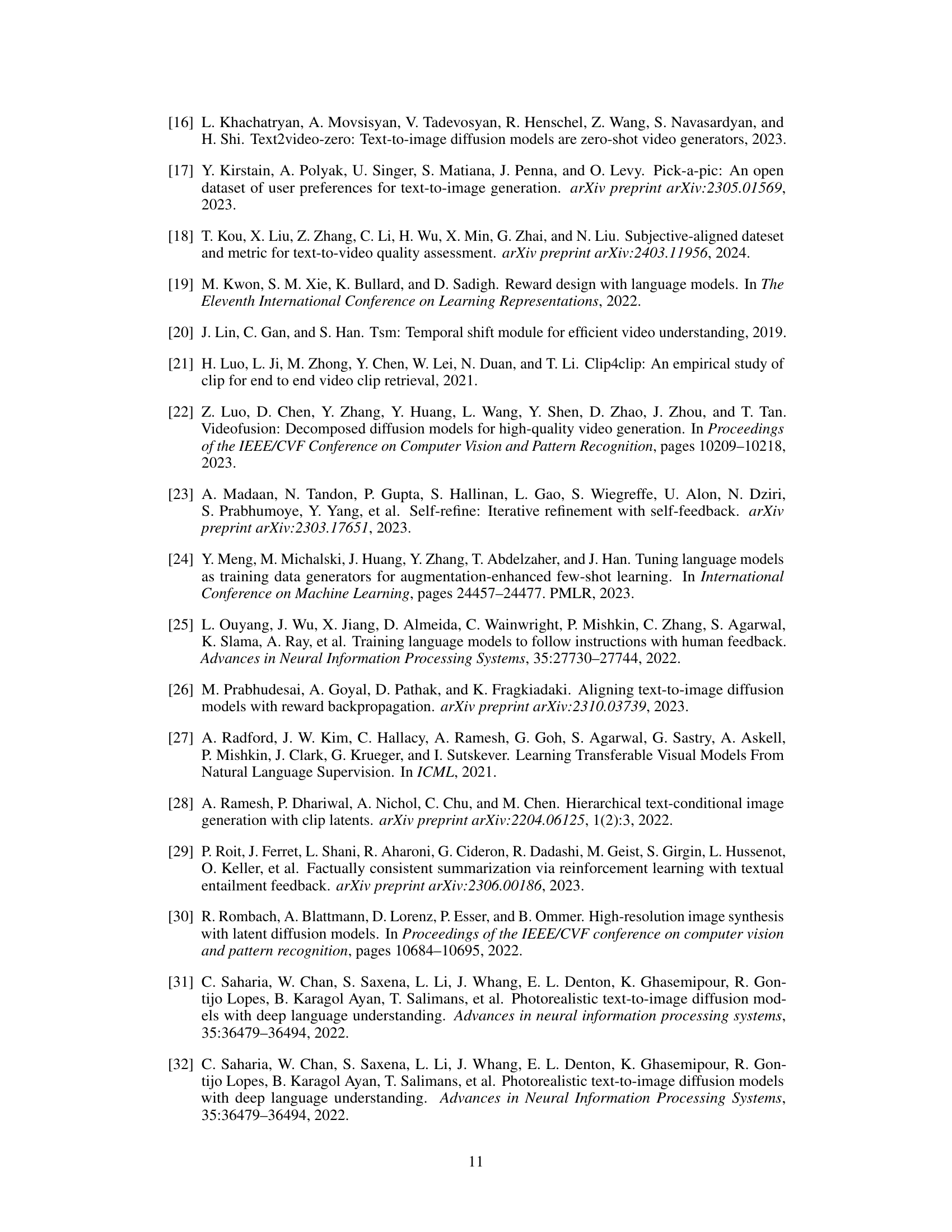

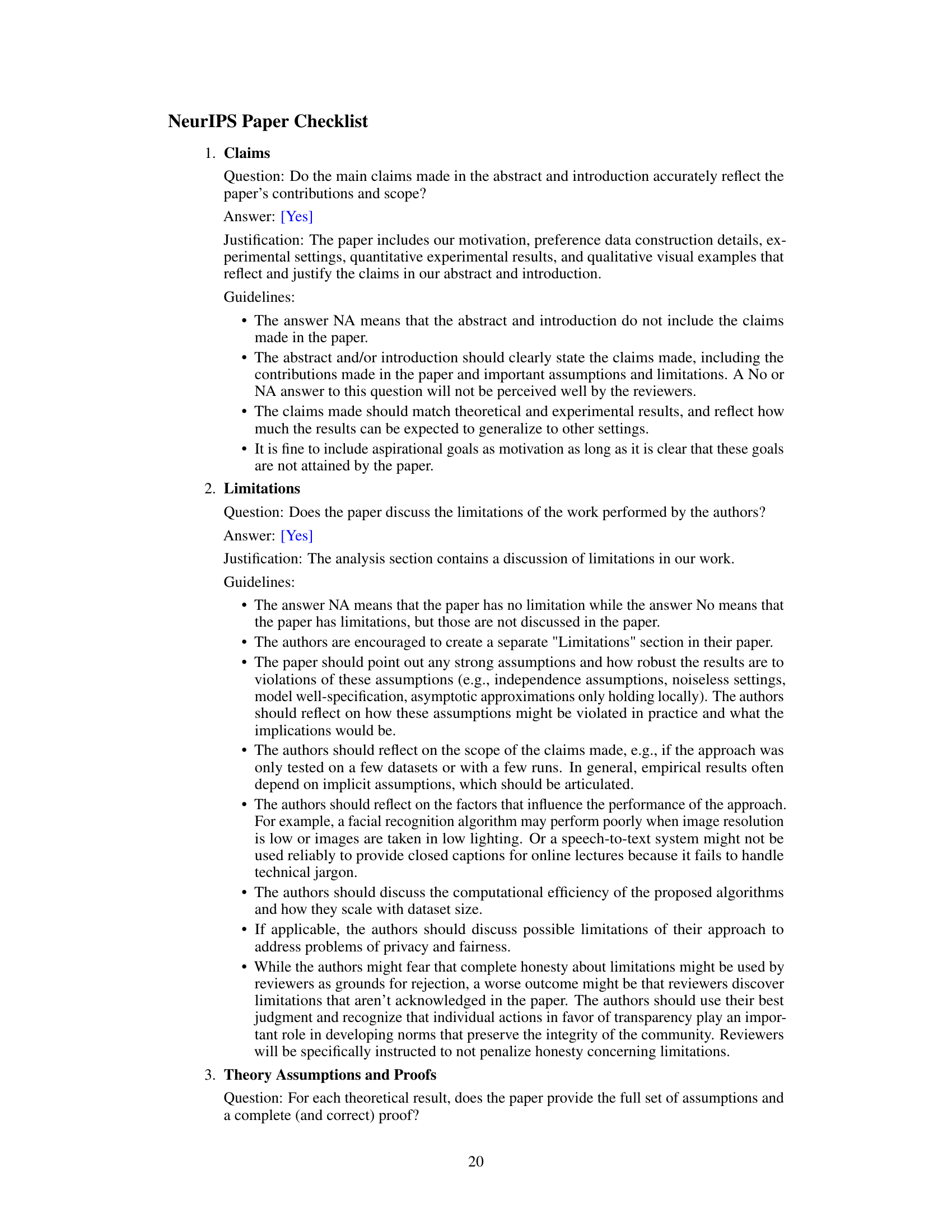

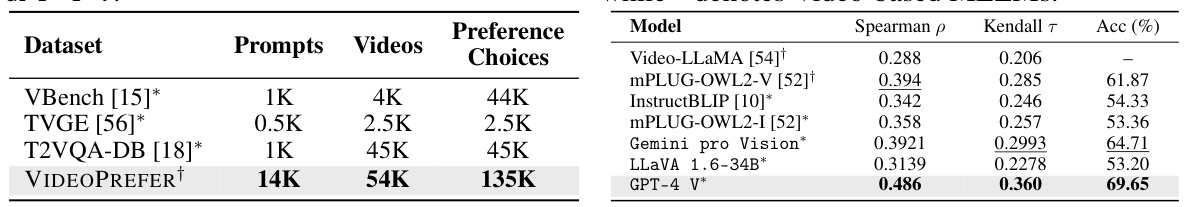

This table presents a comparison of various existing preference datasets used for training text-to-video generative models. It shows the number of prompts, videos, and preference choices in each dataset. The asterisk (*) indicates datasets where human annotation was used to create the preference dataset, while the dagger (†) indicates that GPT-4 V (a large language model from OpenAI) was used for annotation. The table highlights the significantly larger scale of the VIDEOPREFER dataset compared to existing datasets.

In-depth insights#

MLLM Feedback#

The core idea of using Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) for feedback in text-to-video generation is a significant advancement. MLLMs offer a cost-effective and scalable alternative to expensive human annotation, enabling the creation of large-scale preference datasets like VIDEOPREFER. This is crucial because the success of reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) methods in this domain heavily relies on the availability of such data. By leveraging MLLMs to annotate video preferences across multiple dimensions, the researchers were able to overcome the limitations of existing datasets, which were often smaller and less comprehensive. The study’s findings highlight the high concordance between MLLM judgments and human evaluations, validating the use of MLLMs as reliable and efficient annotators. This approach paves the way for future research into more sophisticated reward models and training methods that can leverage the strengths of MLLMs to boost the quality and alignment of text-to-video generative models. The creation of VIDEOPREFER and VIDEORM, a general-purpose reward model for video preferences, represents a significant advancement in this field.

VideoPREFER Dataset#

The VideoPREFER dataset represents a substantial advancement in the field of text-to-video generation, addressing the critical need for large-scale, high-quality datasets to train effective reward models. Its open-source nature and significant size (135,000 preference choices) make it a valuable resource for researchers. The dataset’s fine-grained annotations across two crucial dimensions, prompt-following and video quality, allow for more nuanced evaluation of generated videos. This approach surpasses earlier datasets that focused on more limited aspects of quality. Utilizing MLLMs (Multimodal Large Language Models) for annotation offers a cost-effective and scalable method for creating such extensive resources, an important step toward democratizing the research in text-to-video generation. The inclusion of both model-generated videos and real-world videos further increases the dataset’s generalizability and robustness, making the results applicable to a wider range of applications. However, potential limitations include the reliance on MLLM judgments, which may not perfectly capture human preferences. Future work could explore ways to enhance the annotation process and further expand the diversity of videos and prompts.

VIDEORM Model#

The VIDEORM model, a general-purpose video preference reward model, represents a significant advancement in text-to-video generation. Unlike previous models that rely on image-domain rewards, VIDEORM directly addresses the challenges of video by incorporating temporal modeling modules. This allows it to assess not just individual frames, but the temporal dynamics and coherence of videos. Built using the large-scale VIDEOPREFER dataset, which itself is a major contribution in providing human-aligned video preferences, VIDEORM is shown to be effective in fine-tuning text-to-video models, significantly improving the quality and alignment of generated videos. Its use leads to videos with improved temporal coherence, higher fidelity, and better alignment with textual prompts, showcasing its strength in overcoming the limitations of existing methods. The model’s architecture incorporates Temporal Shift and Temporal Transformer, thereby directly addressing the temporal nature of videos. The integration of VIDEORM into DRaFT-V, an optimized RLHF algorithm, further enhances the efficiency of training, making it a highly effective solution for improving text-to-video generation.

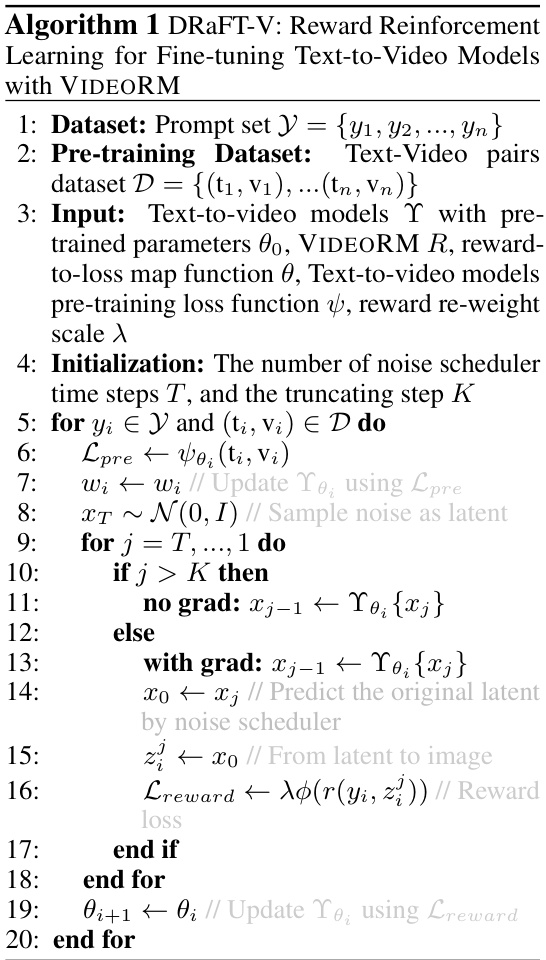

DRaFT-V Algorithm#

The DRaFT-V algorithm, a novel approach for fine-tuning text-to-video generative models, cleverly integrates the VIDEORM reward model into the image-domain DRaFT algorithm. Its key innovation lies in efficiently leveraging the temporal modeling capabilities of VIDEORM, which unlike previous methods that rely on frame-by-frame processing, assesses the entire video. This holistic evaluation improves the quality assessment and model alignment. Furthermore, DRaFT-V strategically truncates the backward pass, only computing reward scores from the final K steps, significantly boosting computational efficiency without sacrificing performance. This optimization is critical considering the high dimensionality of video data. The use of LORA further accelerates fine-tuning, mitigating the risk of catastrophic forgetting. By incorporating VIDEORM, DRaFT-V overcomes limitations of existing techniques that directly use image-domain reward models. This results in more effective video preference alignment and minimizes visual artifacts like structural twitching and color jittering often seen in previous methods.

Future of RLAIF#

The future of Reinforcement Learning from AI Feedback (RLAIF) appears incredibly promising, particularly within the context of text-to-video generation. The success of using MLLMs as efficient and scalable annotators for video preferences demonstrated in this research significantly lowers the barrier to generating large-scale, high-quality datasets necessary for training robust reward models. This opens the door for improved fine-tuning of generative models, leading to videos that more faithfully reflect textual prompts and exhibit enhanced visual appeal. Moving forward, research should focus on addressing remaining challenges such as the cost-effectiveness of large-scale annotation even with MLLMs, and exploring new methods to better capture the nuances of human preferences in video generation. Addressing these limitations will be crucial to fully unlock the potential of RLAIF for creating even more compelling and realistic text-to-video experiences. Investigating the generalizability of MLLM-based annotation across diverse video styles and cultures would also enhance the applicability of RLAIF. Further research exploring novel reward model architectures optimized for the inherent spatio-temporal nature of video data, and further advancements in reinforcement learning algorithms specifically designed for the video domain, are important next steps. Ultimately, the future of RLAIF hinges on effectively bridging the gap between machine-generated evaluations and the complex subtleties of human aesthetic judgment.

More visual insights#

More on figures

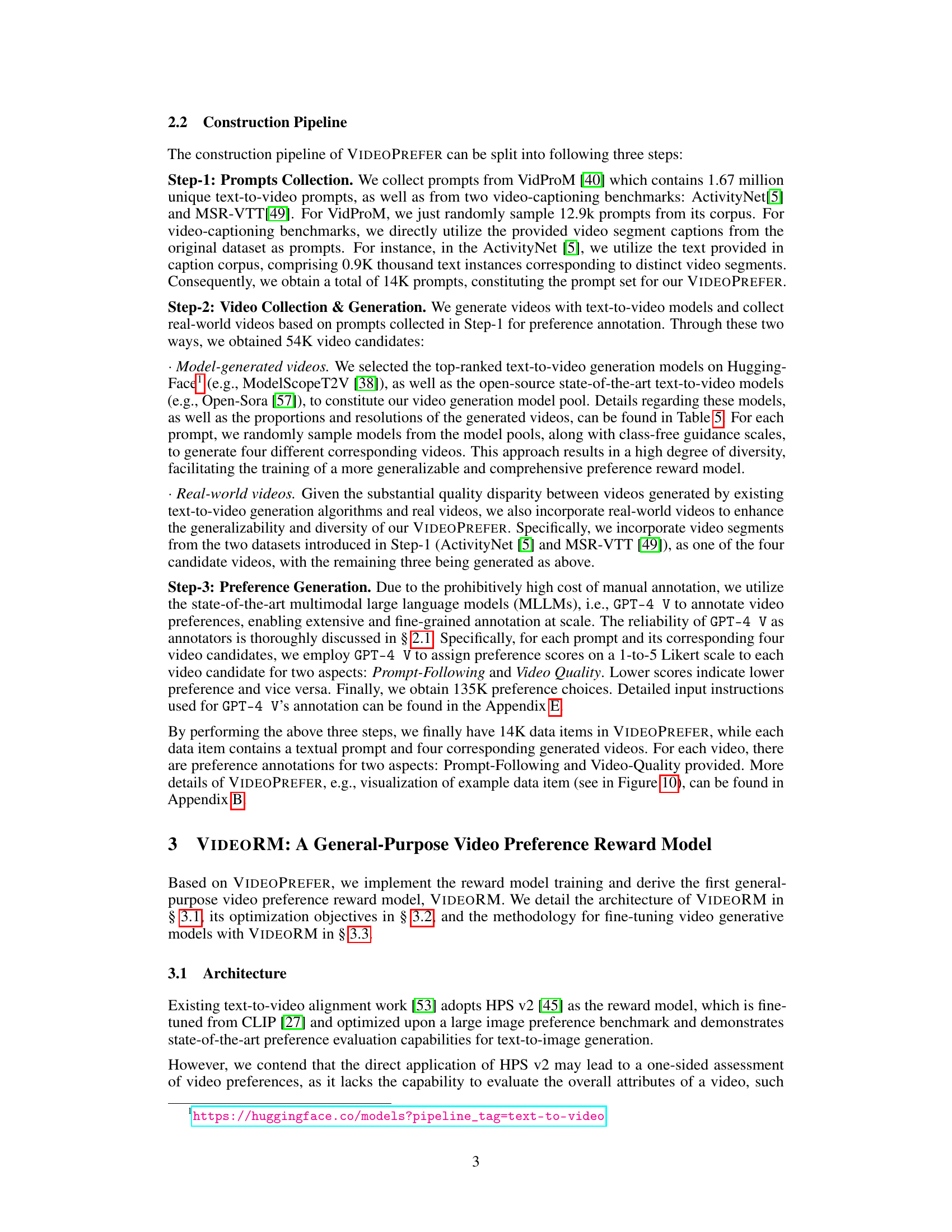

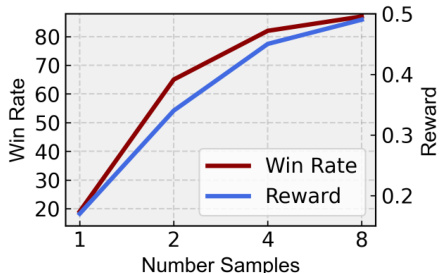

This figure shows the results of best-of-n experiments conducted on the T2VQA-DB benchmark dataset to evaluate the effectiveness of VIDEORM in selecting high-quality videos. In these experiments, n videos were generated for each prompt, and the video with the highest reward score (as determined by VIDEORM) was selected as the ‘best’. The graph plots the win rate (percentage of times the best video selected by VIDEORM was preferred by human evaluators) against the number of samples (n). As n increases, the win rate also increases, indicating that VIDEORM is effective in identifying higher-quality videos.

This figure shows the results of best-of-n experiments conducted on the T2VQA-DB [18] test benchmark to evaluate the effectiveness of VIDEORM in identifying high-quality videos. In these experiments, n videos were generated for each prompt, and VIDEORM’s reward scores were used to select the best video. The x-axis represents the number of samples (n) considered, and the y-axis shows the win rate, indicating the percentage of times the top-ranked video selected by VIDEORM was indeed considered superior. The results demonstrate a clear positive correlation between the number of samples considered and the win rate, suggesting that VIDEORM is effective at identifying higher-quality videos.

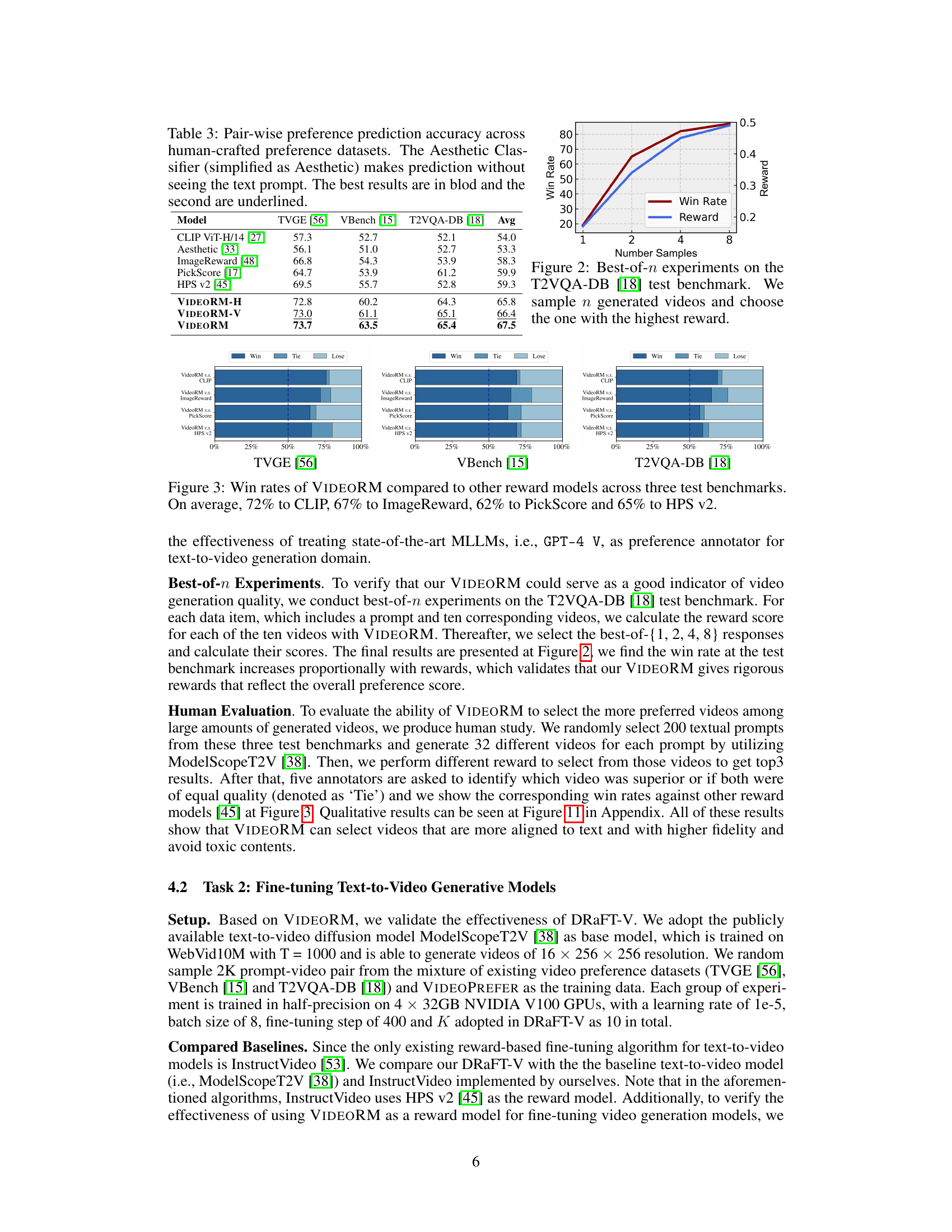

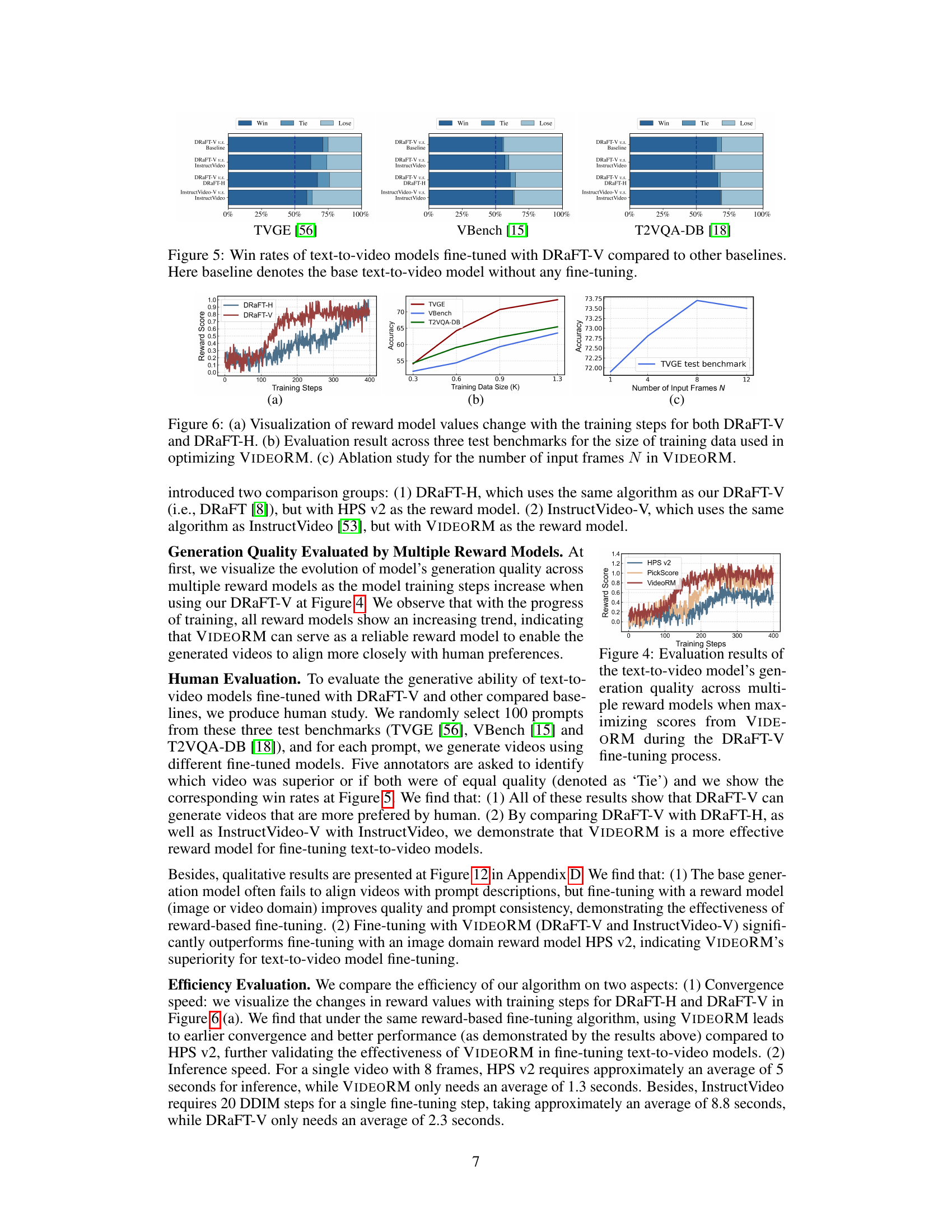

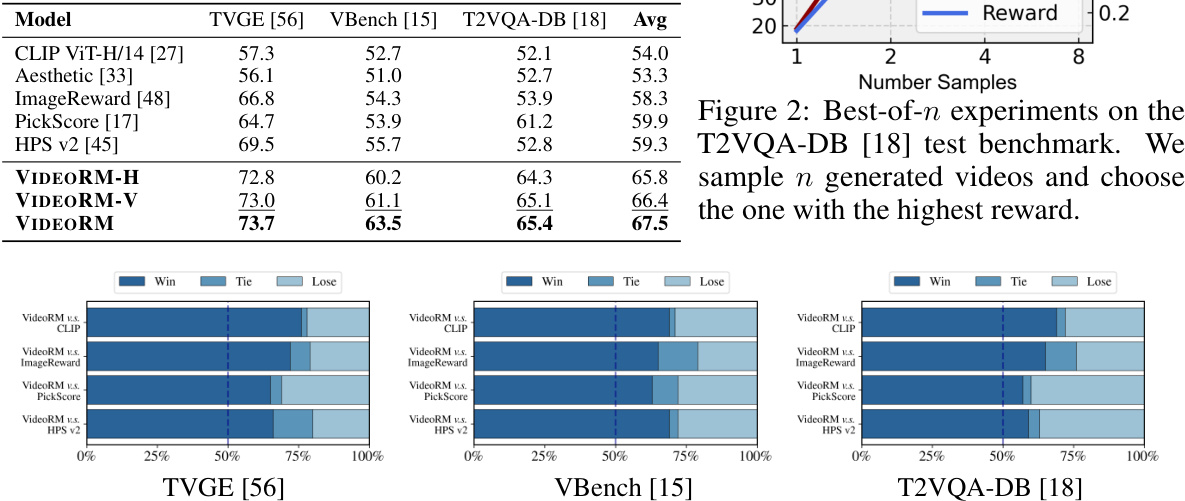

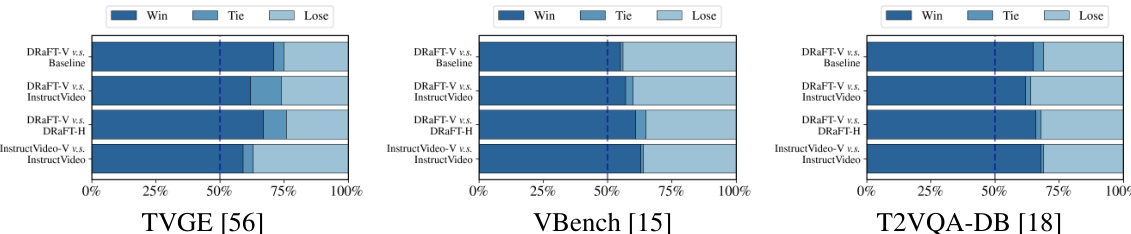

This figure presents the results of a human evaluation comparing the performance of three different fine-tuning methods for text-to-video models: DRaFT-V, InstructVideo, and a baseline model without fine-tuning. The evaluation metrics are win rate, tie rate, and loss rate across three benchmark datasets: TVGE [56], VBench [15], and T2VQA-DB [18]. Each bar in the chart represents the proportion of wins, ties, and losses for each comparison on a given dataset. The results show that DRaFT-V consistently outperforms both InstructVideo and the baseline, demonstrating its effectiveness in aligning text-to-video generation with human preferences.

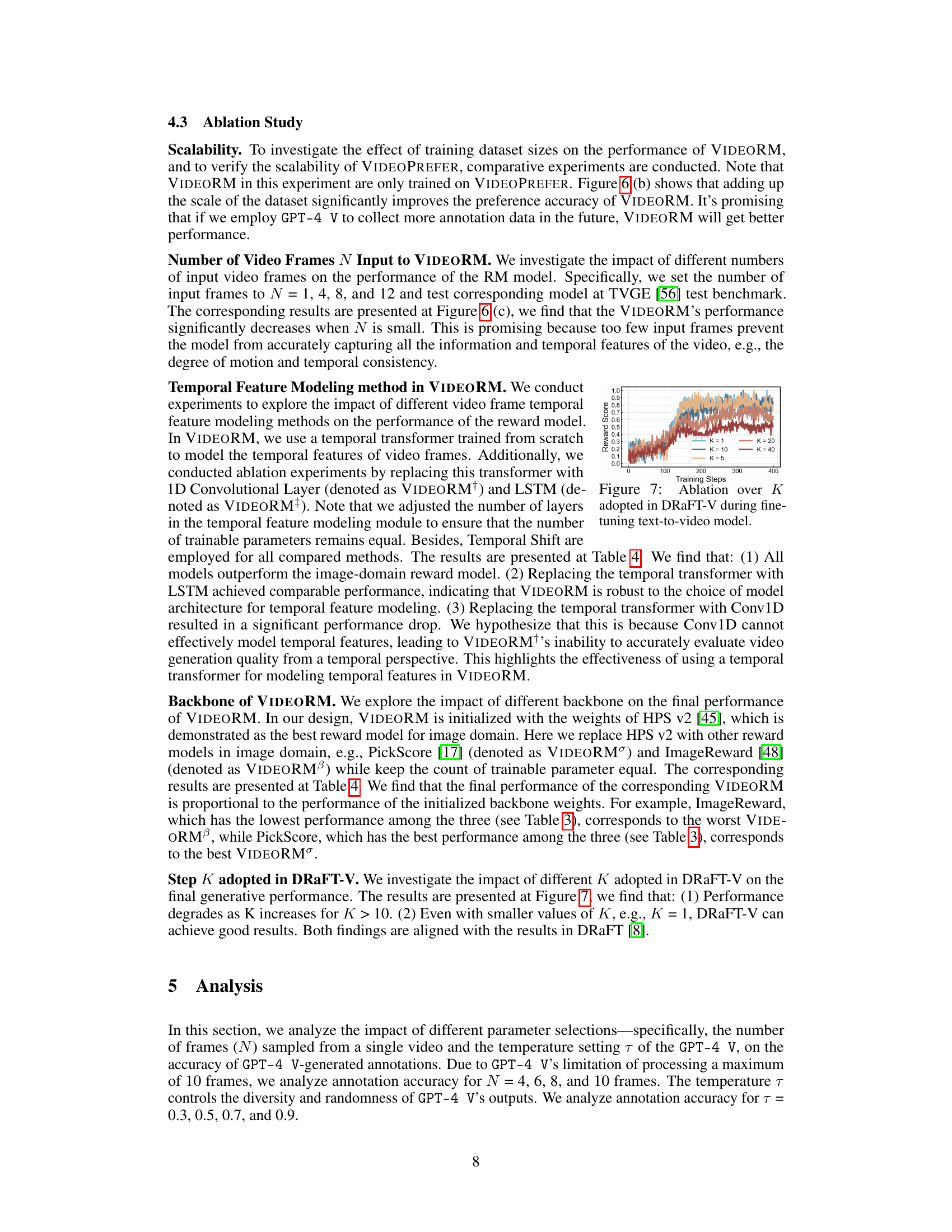

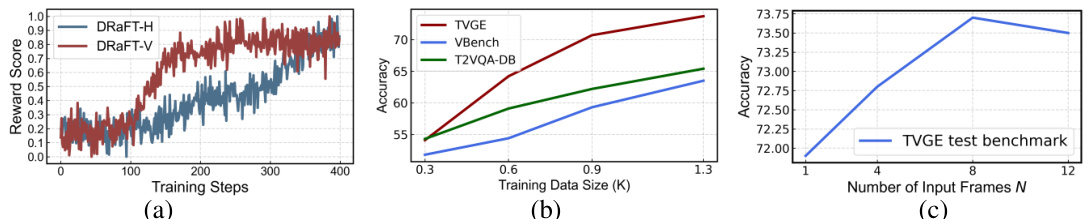

This figure presents three subplots that demonstrate the impact of different hyperparameters on the performance of reward models. Plot (a) compares the change in reward scores for DRaFT-V and DRaFT-H during training steps. Plot (b) shows the accuracy of VIDEORM on three benchmark datasets (TVGE, VBench, and T2VQA-DB) under different sizes of training data. Plot (c) examines the effect of varying the number of input frames (N) in VIDEORM on the accuracy of the model on TVGE benchmark dataset.

This figure presents three subplots showing the results of experiments evaluating the VIDEORM model. (a) shows the reward model values changing over training steps for two different methods, DRaFT-V and DRaFT-H. (b) shows evaluation results across three benchmarks for varying training data sizes used to optimize VIDEORM. (c) shows an ablation study for the number of input video frames (N) used in VIDEORM, demonstrating its performance under different input frame numbers.

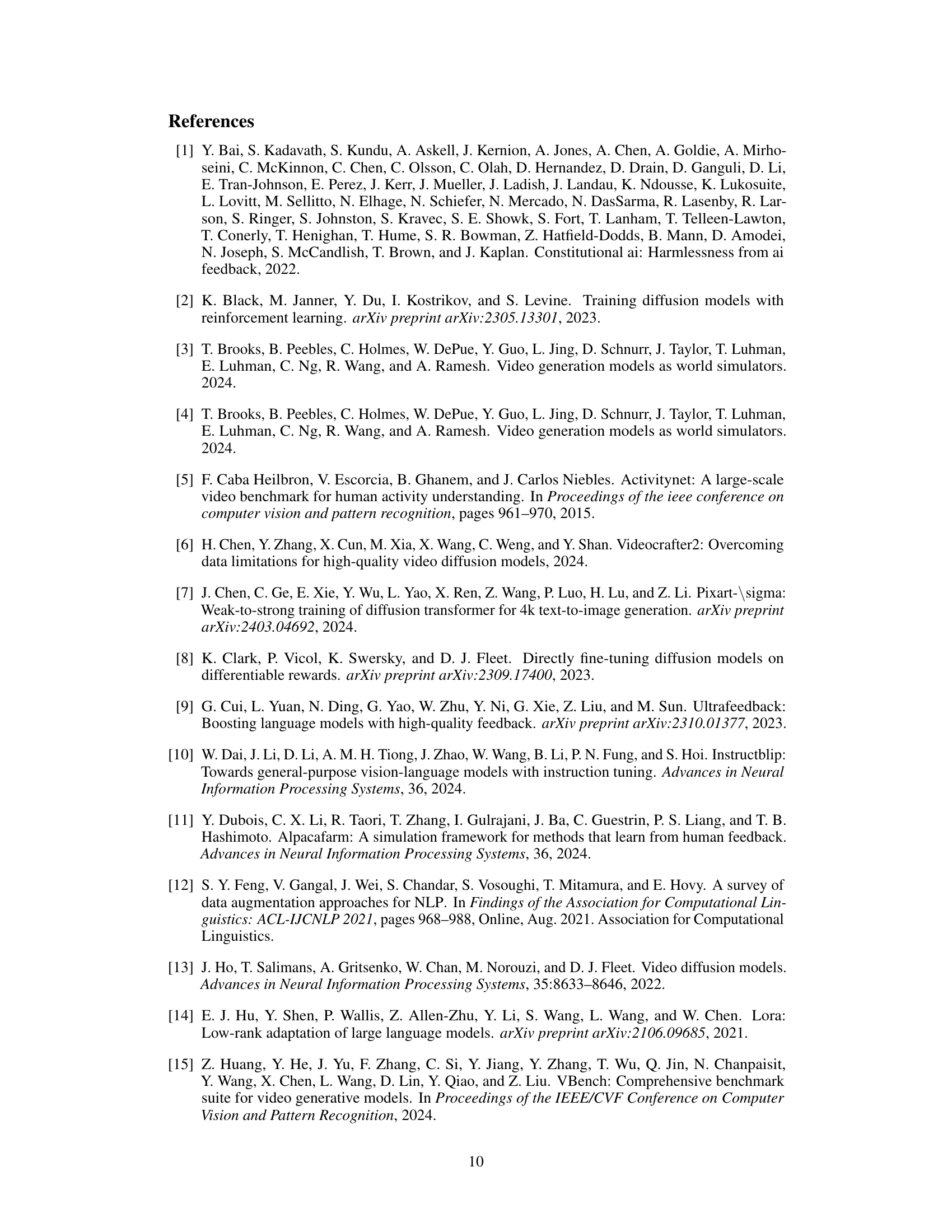

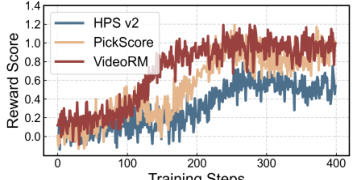

This figure shows the ablation study on the impact of different K values adopted in the DRaFT-V algorithm during the fine-tuning process of text-to-video models. The x-axis represents the training steps, and the y-axis represents the reward score. Different lines represent different values of K (1, 5, 10, 20, 40). The figure demonstrates how the performance of the algorithm changes with different K values during model training.

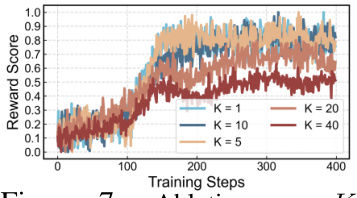

The figure shows the impact of two hyperparameters, the number of frames (N) and the temperature (τ), on the accuracy of GPT-4 V annotations. The x-axis represents the number of frames considered, while the y-axis represents the annotation accuracy. Two lines are plotted, one for different temperature values and another for different frame numbers, showing how accuracy changes. The results suggest that annotation accuracy increases initially with the number of frames considered, but then plateaus or even decreases for higher frame counts. Similarly, lower temperatures generally lead to higher accuracy, suggesting that less randomness in the GPT-4 V model improves annotation consistency.

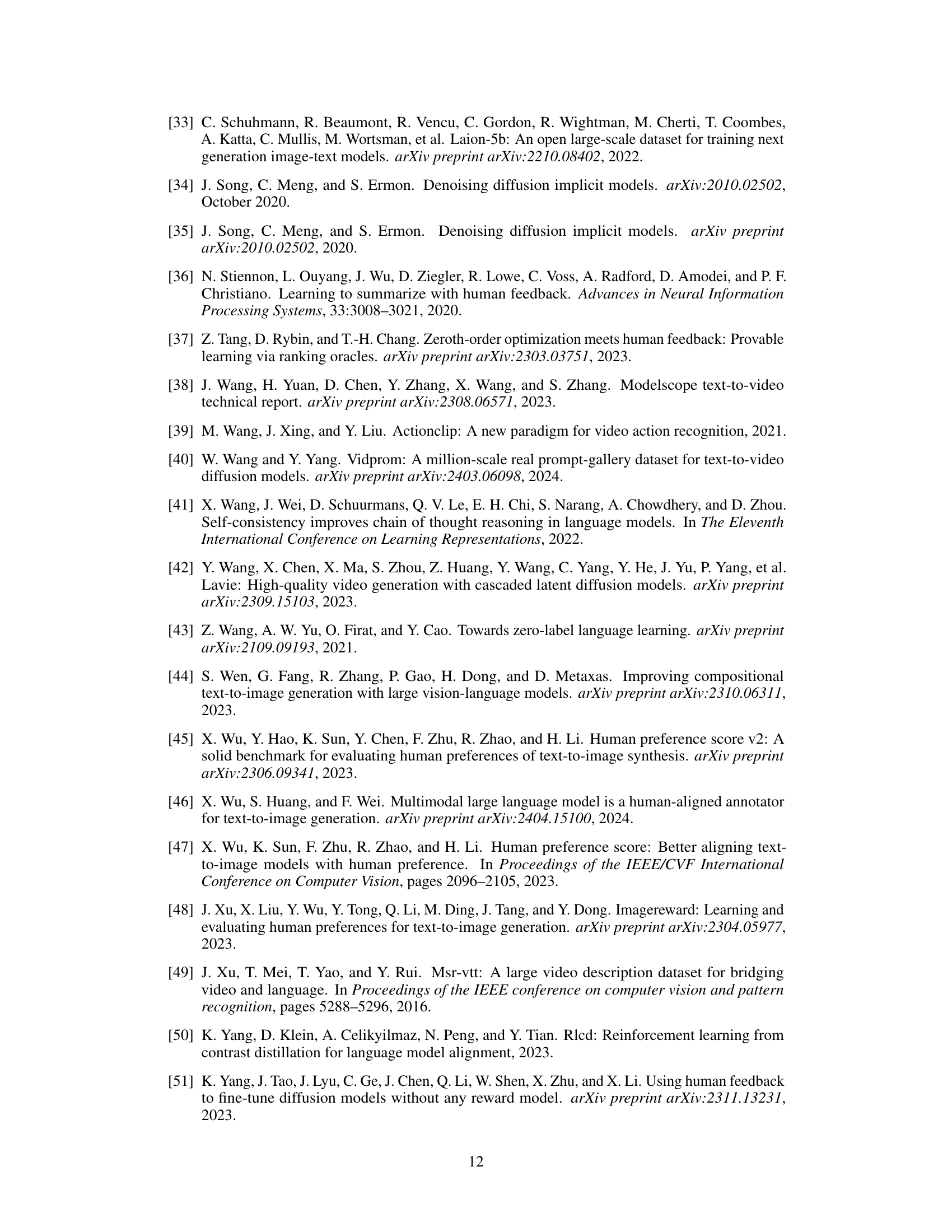

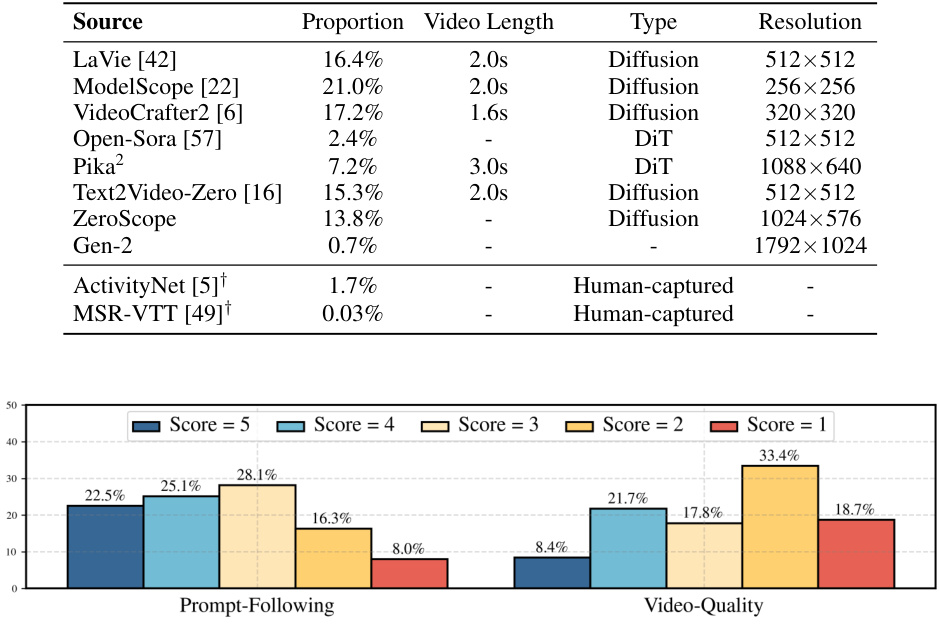

This figure shows the distribution of scores across the two annotation aspects in the VIDEOPREFER dataset: Prompt-Following and Video-Quality. The bar chart displays the percentage of annotations receiving each score (1-5) for each aspect. The distribution for Prompt-Following is relatively normal, indicating a good spread of opinions, while the Video-Quality scores skew toward the lower end, suggesting that the generated videos often fall short of ideal quality.

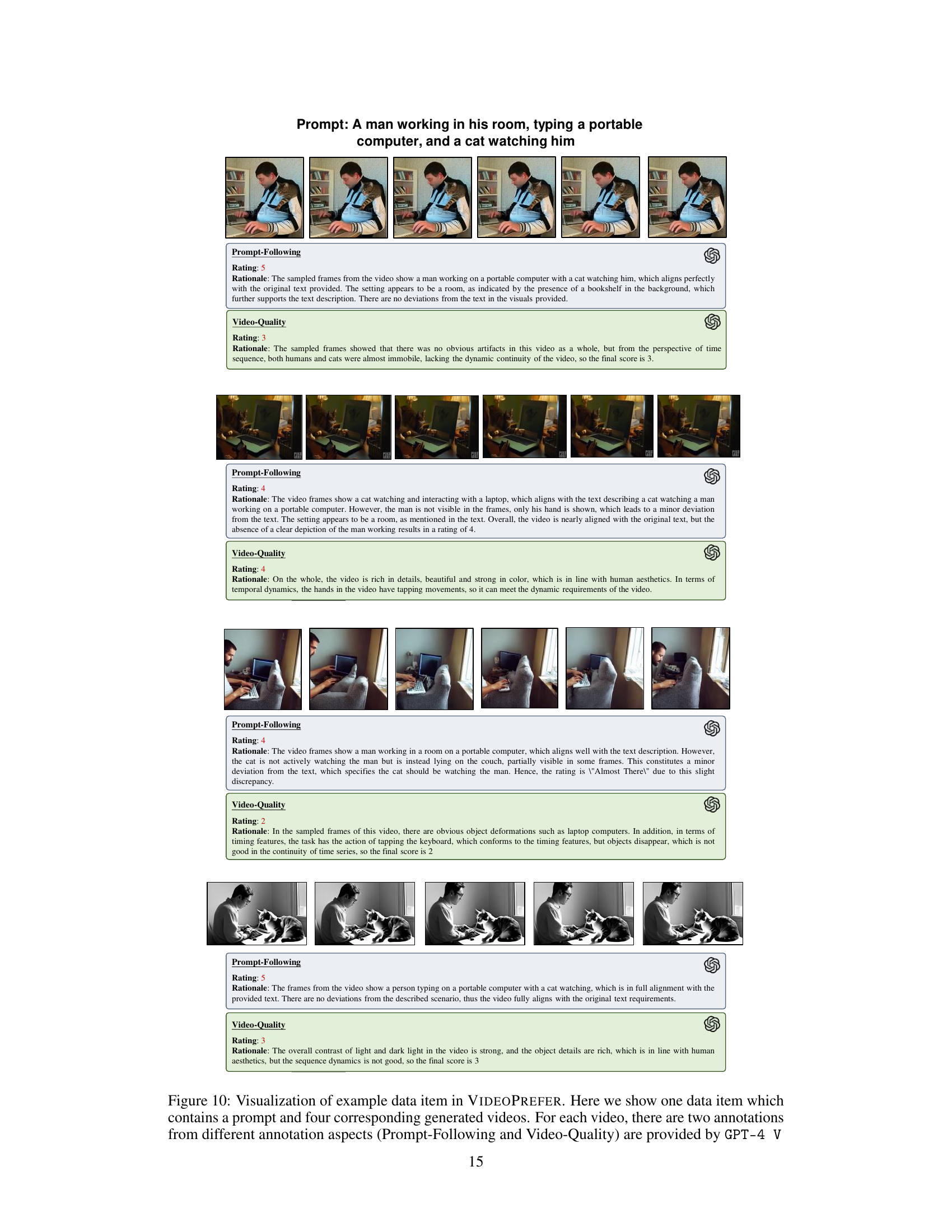

This figure shows an example data point from the VIDEOPREFER dataset. It consists of a text prompt (e.g., a description of a scene) and four corresponding video clips generated by different models. Each video clip is accompanied by two scores provided by GPT-4 V, assessing how well the video follows the prompt and the overall video quality. The scores provide a fine-grained evaluation of the generated videos.

This figure shows an example data item from the VIDEOPREFER dataset. It consists of a text prompt and four video clips generated from that prompt by different models. Each video is accompanied by two scores from GPT-4 V: one evaluating how well the video follows the prompt, and one assessing its visual quality.

This figure shows an example data item from the VIDEOPREFER dataset. Each data item includes a text prompt and four generated videos. For each video, GPT-4V provides two scores: one for how well the video follows the prompt, and another for video quality. The figure visually displays the prompt, the four video frames, and the two scores assigned by GPT-4V for each video.

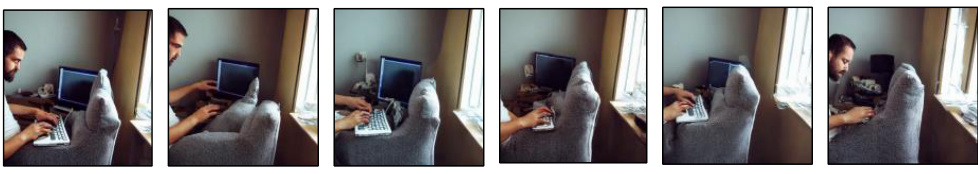

This figure shows a sample data entry from the VIDEOPREFER dataset. Each entry consists of a text prompt describing a scene (e.g., ‘A man working in his room, typing on a portable computer, and a cat watching him’) and four corresponding videos generated by different models. Each video receives two scores from GPT-4 V: one for ‘Prompt-Following’ (how well the video matches the prompt) and one for ‘Video-Quality’ (the overall aesthetic and technical quality of the video). The scores provide a fine-grained evaluation of the generated videos, demonstrating the dataset’s capacity for detailed assessment.

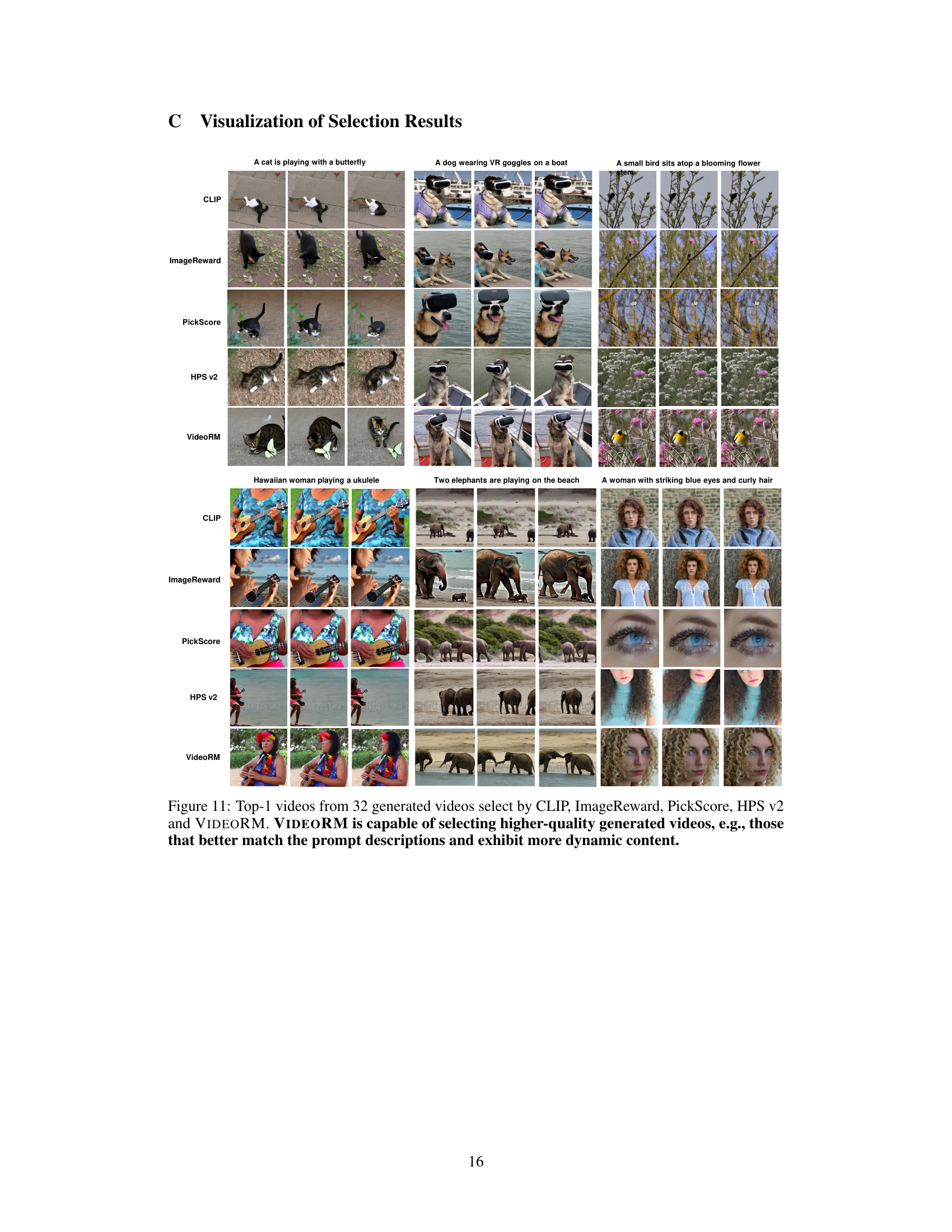

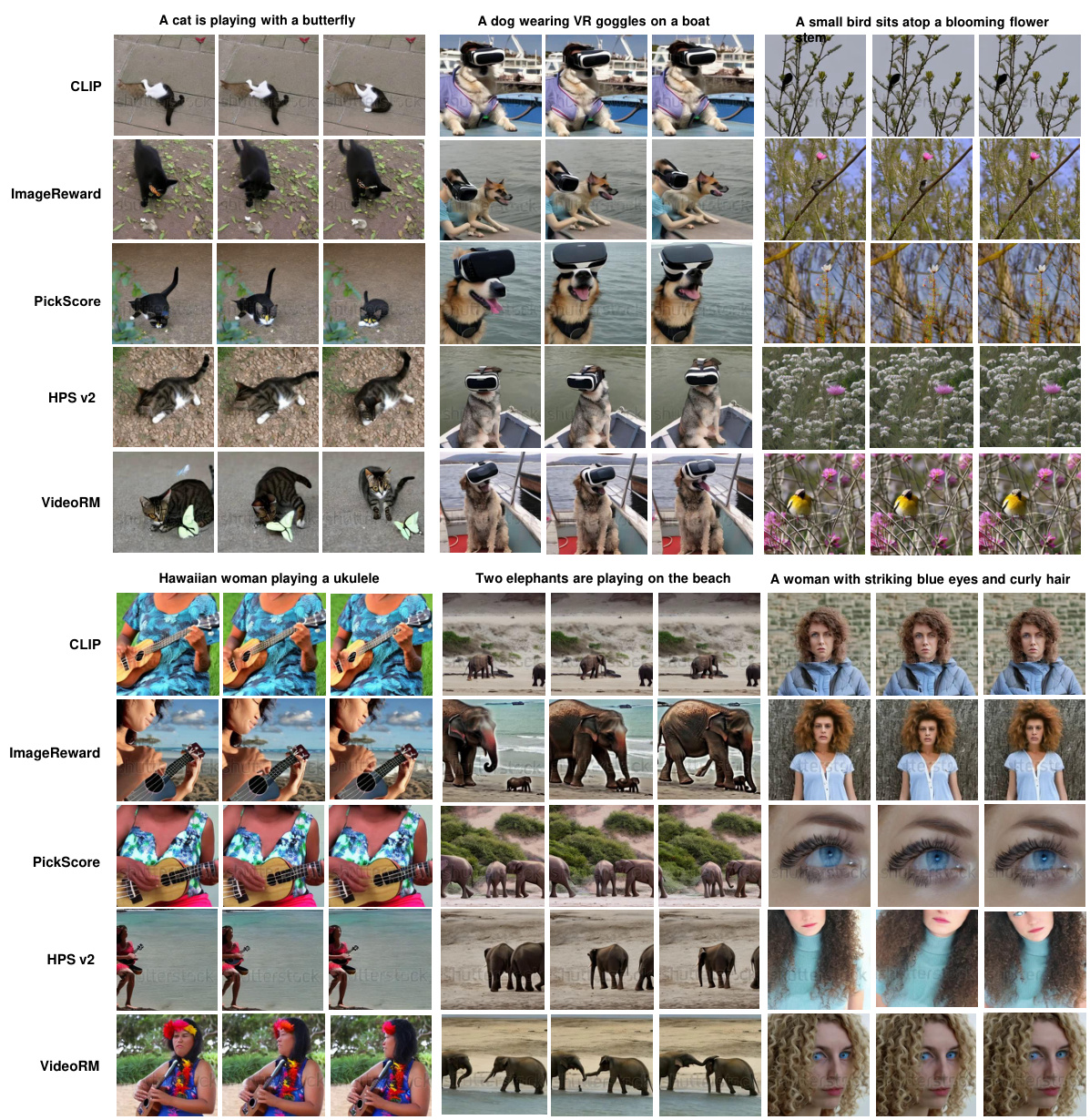

This figure shows the top-ranked videos selected by five different reward models (CLIP, ImageReward, PickScore, HPS v2, and VIDEORM) for three different prompts. The goal is to demonstrate the ability of VIDEORM to select videos that better match the text prompt and exhibit more dynamic and engaging content compared to other reward models.

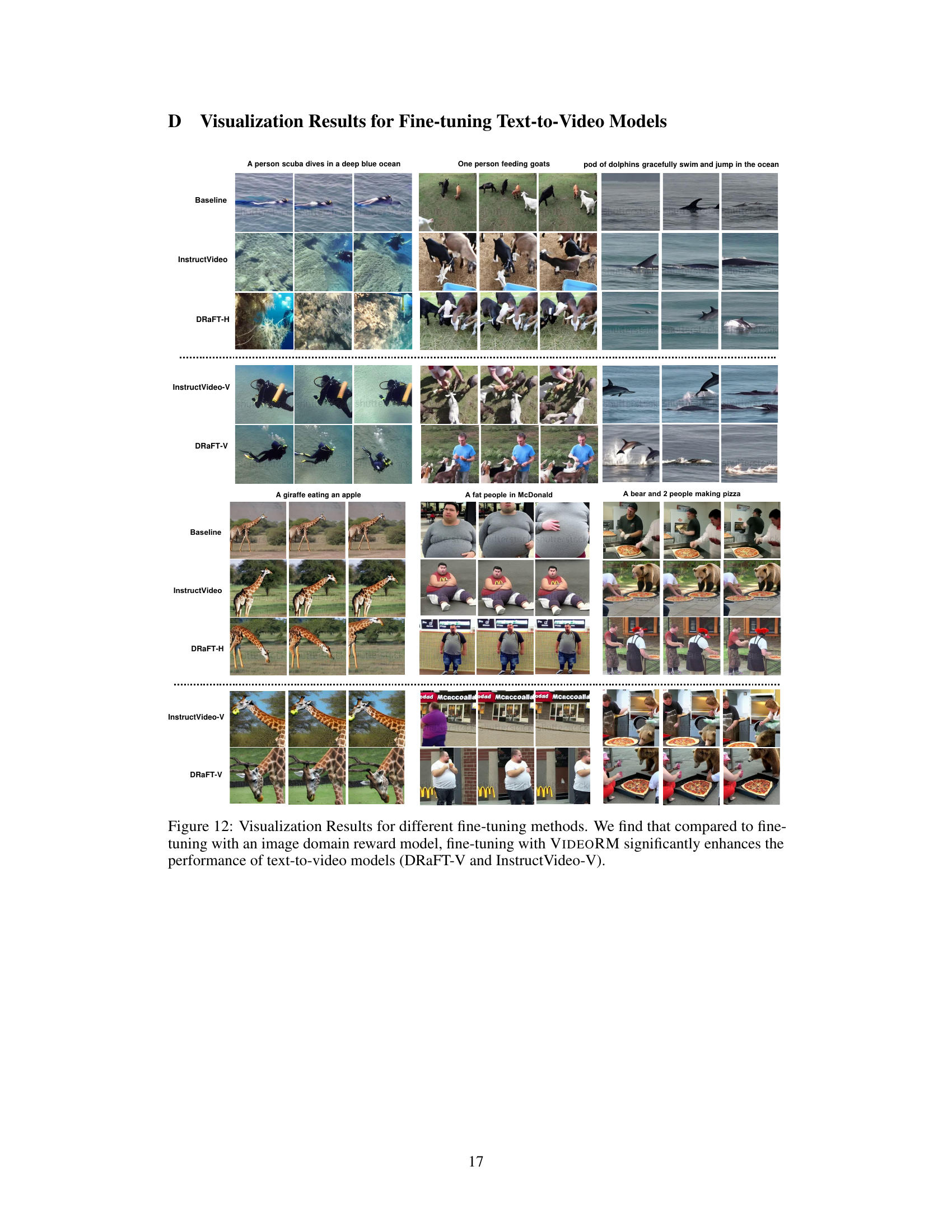

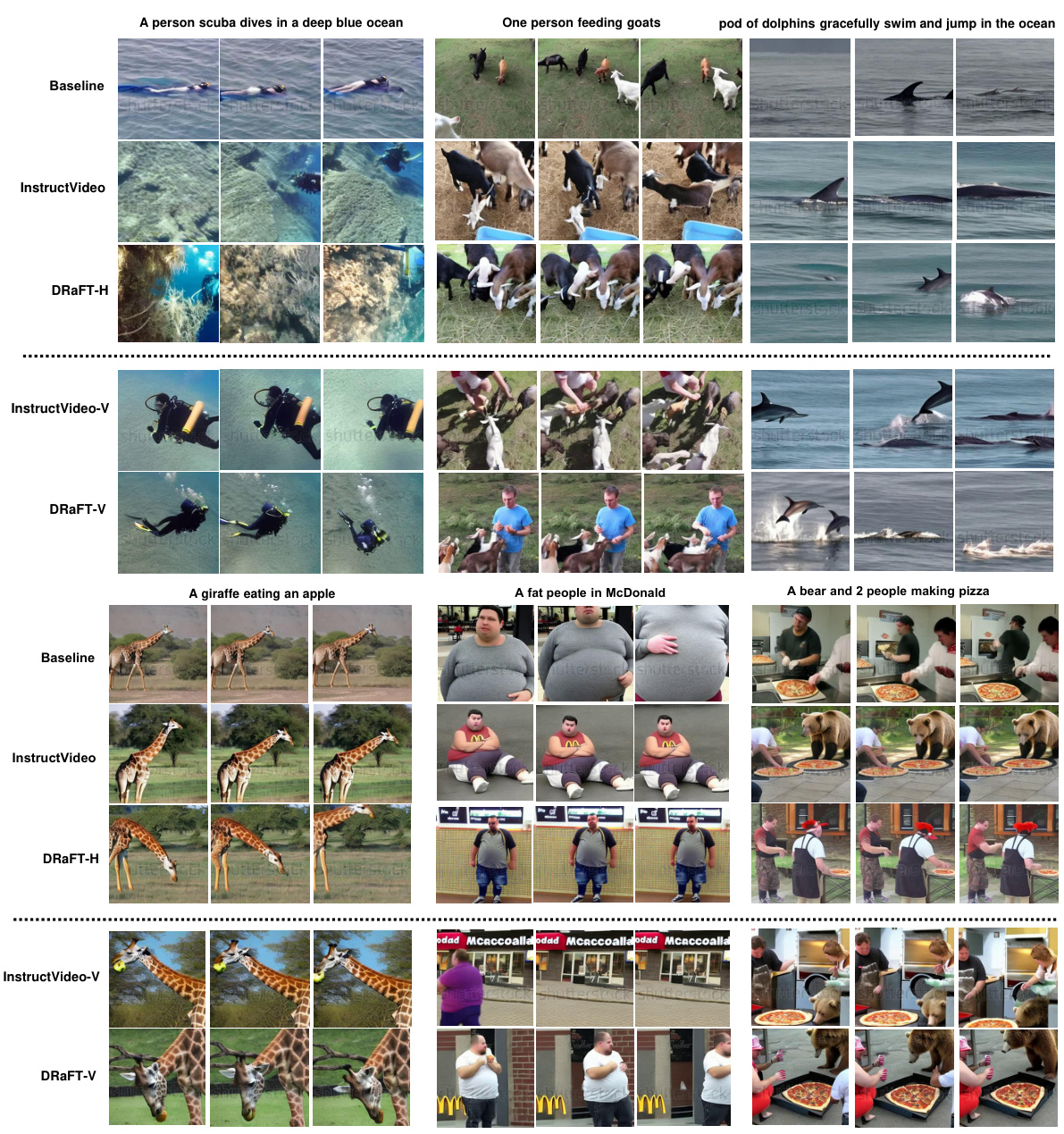

This figure compares the results of fine-tuning text-to-video models using different reward models. The baseline model is compared to InstructVideo (using HPS v2), DRaFT-H (using HPS v2), InstructVideo-V (using VIDEORM), and DRaFT-V (using VIDEORM). The results show that using VIDEORM for fine-tuning significantly improves the quality of the generated videos compared to using an image-based reward model like HPS v2.

The figure illustrates the architecture of VIDEORM, a video preference reward model. It shows how the model uses a combination of image and text encoders, along with added temporal modeling modules (Temporal Shift and Temporal Transformer), to evaluate video preferences holistically, considering both individual frames and the overall temporal coherence and dynamics of the video. The text input is processed by a text encoder and compared against the video, which is processed by an image encoder that includes the temporal modules before finally outputting a preference score.

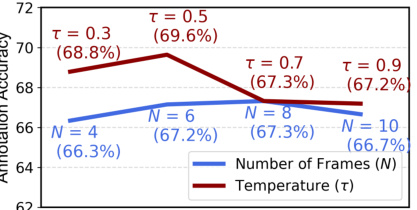

More on tables

This table presents a comparison of various existing preference datasets used for training text-to-video generative models. It shows the number of prompts, videos, and preference choices included in each dataset. The table highlights the relative scarcity of large-scale preference datasets in the video domain compared to the image domain, and indicates whether the annotations were provided by humans or an AI model (GPT-4 Vision). The dataset VIDEOPREFER is introduced as a significantly larger dataset compared to those previously available.

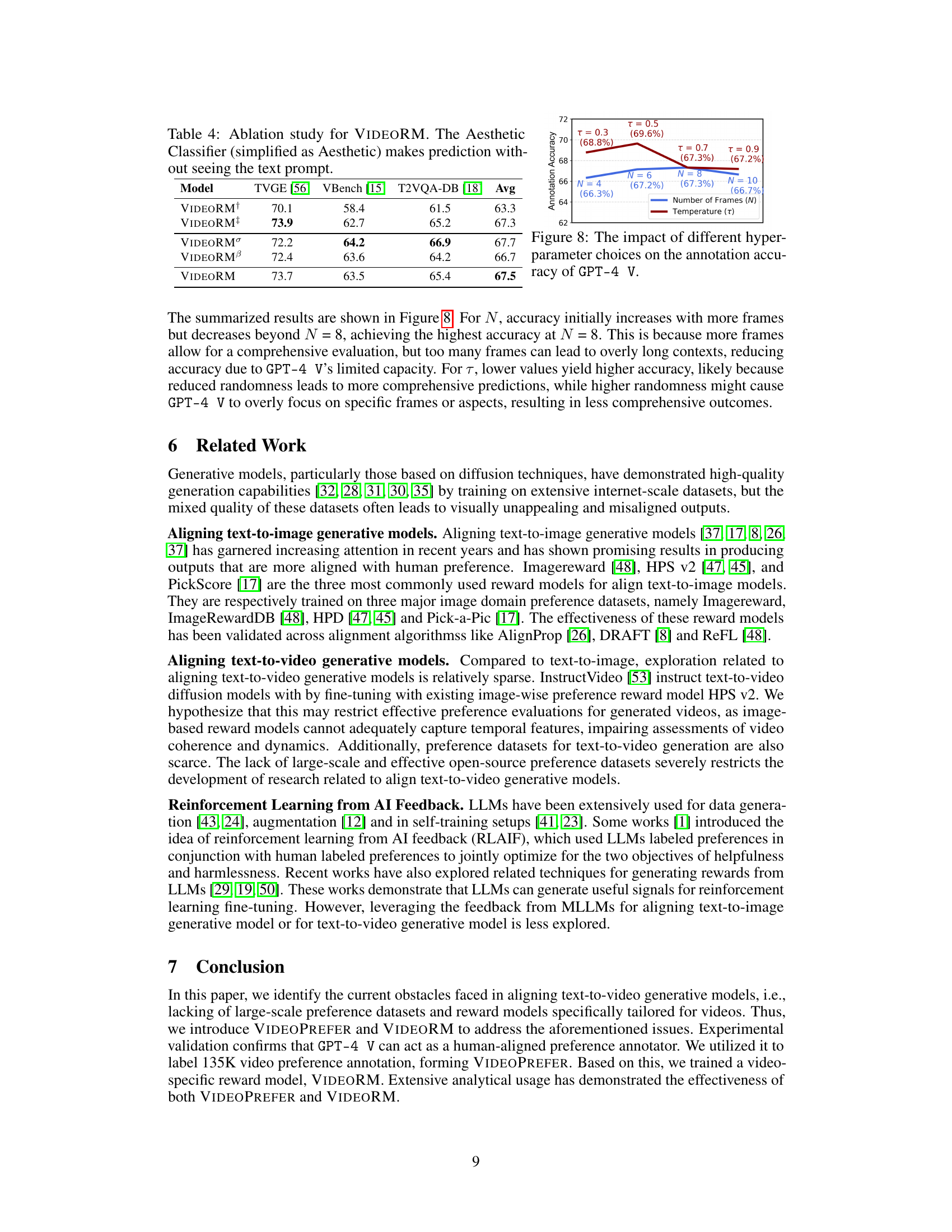

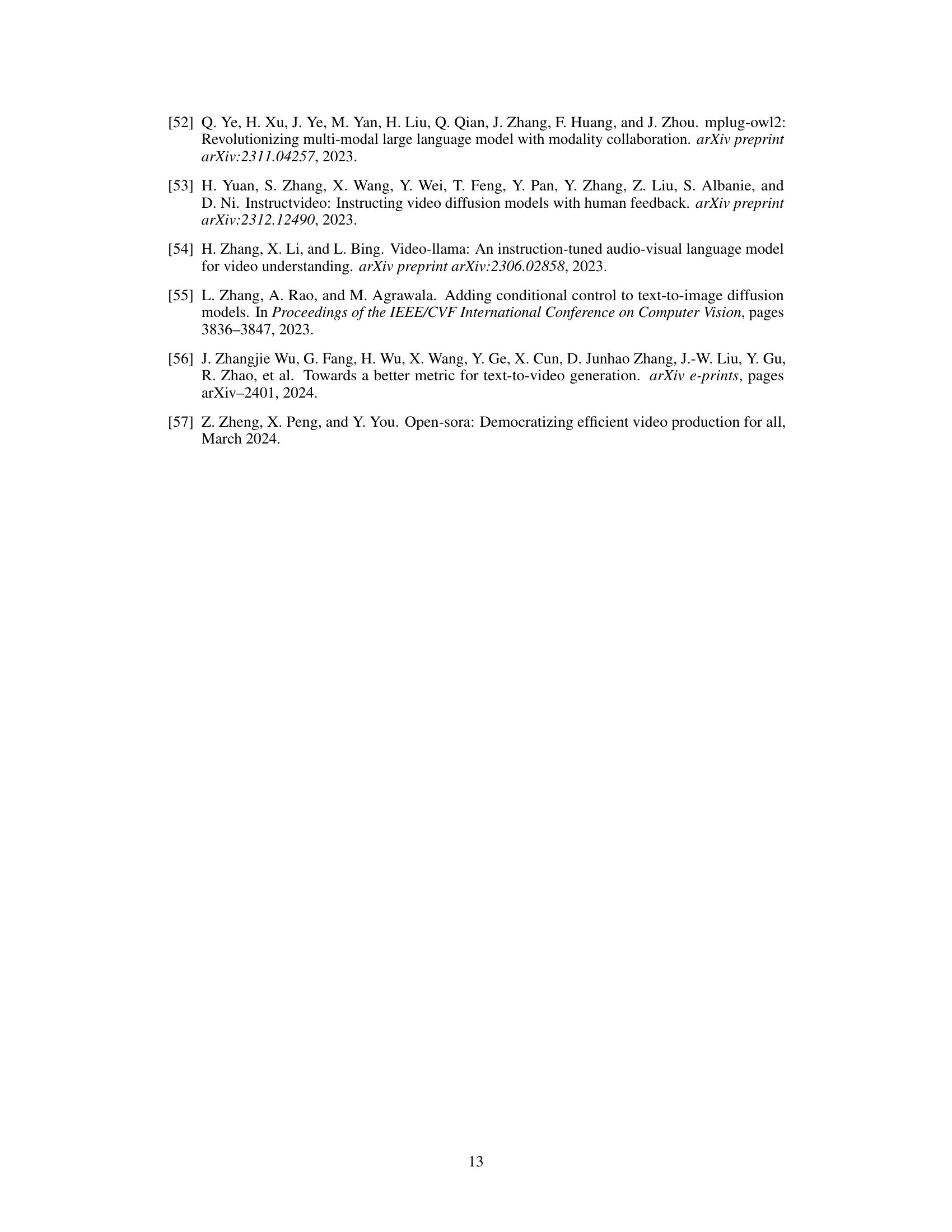

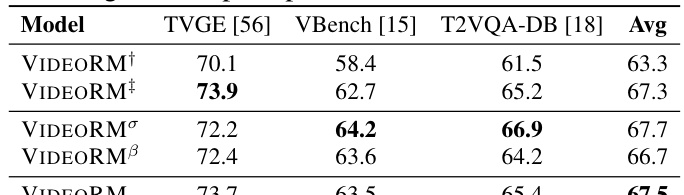

This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted on the VIDEORM model. The study investigates the impact of different components and configurations of the model on its performance. Specifically, it shows the pairwise preference prediction accuracy across three different human-crafted datasets (TVGE [56], VBench [15], T2VQA-DB [18]) for several variations of the VIDEORM model. The variations include changes to the temporal feature modeling method (VIDEORM+, VIDEORM†), the backbone model (VIDEORMa, VIDEORMβ), and the original VIDEORM model. The ‘Aesthetic’ row represents a baseline model that makes predictions without considering text prompts. The average accuracy across all three datasets is also provided for comparison.

Full paper#