↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional machine learning often assumes a static data distribution. However, in many real-world applications, algorithmic decisions influence user behavior, leading to a phenomenon known as “performative learning.” This poses a significant challenge because the data distribution changes as a consequence of the deployed model, invalidating standard learning approaches. This paper addresses this issue by proposing a new framework for modelling performative effects using “push-forward measures.” This framework allows researchers to understand how model parameters affect data distributions and enables new gradient estimation techniques. The framework is applied to classification problems, and under a new set of assumptions, the paper proves the convexity of performative risk. This has important implications for training algorithms and opens up new research directions.

The paper’s main contribution is a new and more efficient way to estimate the gradient of performative risk. This is achieved by modelling performative effects as push-forward measures, leading to a more intuitive and scalable learning strategy. Moreover, they prove the convexity of the performative risk in binary classification problems under specific conditions, removing the previous requirement for small performative effects. Finally, they establish a link between performative learning and adversarial robustness, suggesting that techniques from robust learning could improve performative learning models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in machine learning and related fields because it offers novel solutions to a critical problem: performative learning. It provides new theoretical insights into the convexity of performative risk and demonstrates how this relates to adversarial robustness. The proposed push-forward model and efficient gradient estimation method can be applied to various real-world problems and improve the scalability of performative learning models. Furthermore, the paper opens new avenues for research on the intersection of performative learning and adversarial robustness.

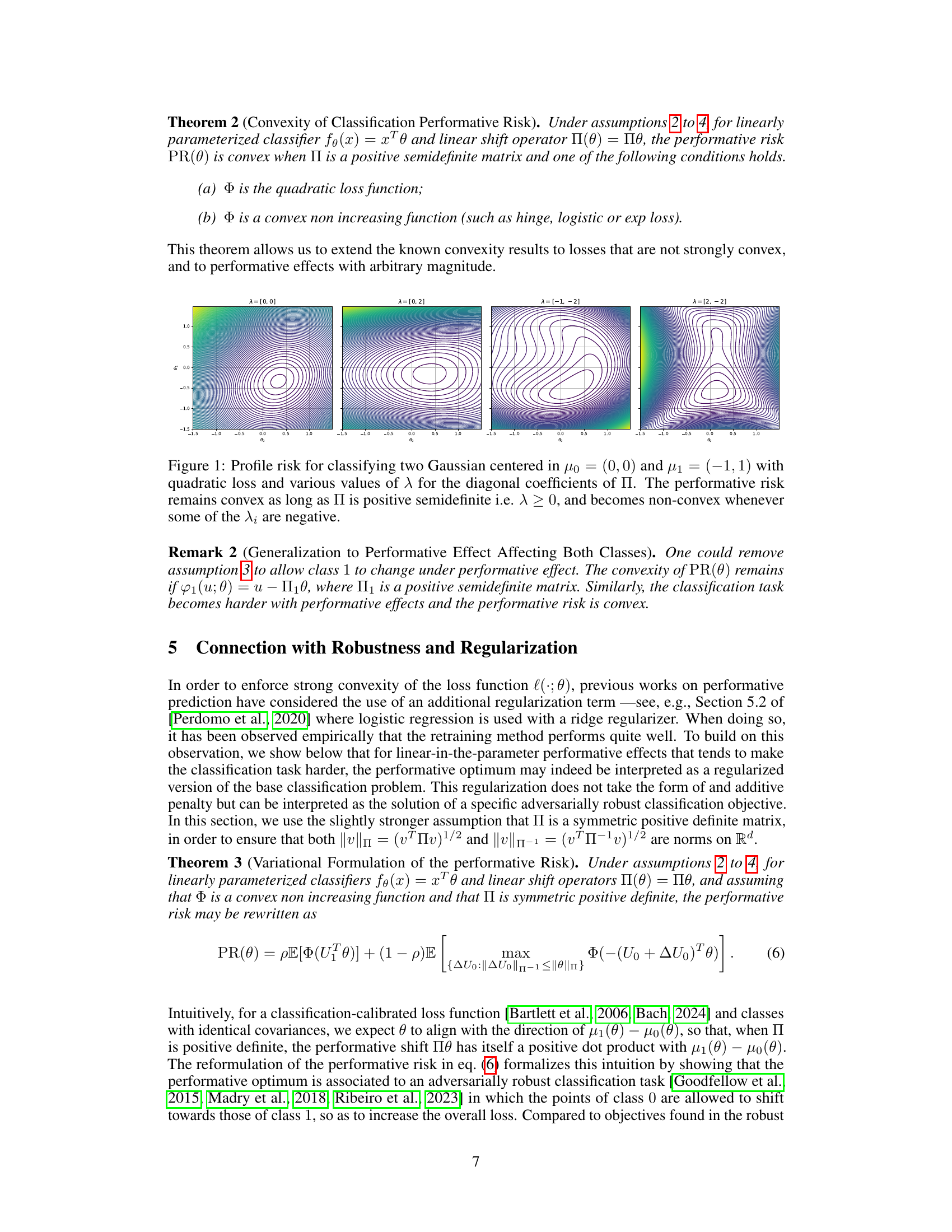

Visual Insights#

This figure shows contour plots of the performative risk for a binary classification problem with two Gaussian distributions. The x and y axes represent the parameters θ1 and θ2 of a linear classifier. Different subplots show the performative risk with varying diagonal elements (λ) of the matrix Π, which represents the performative effect. The plots illustrate how the convexity of the performative risk depends on the values of λ. Specifically, the risk is convex when all λi are non-negative, and becomes non-convex when some λi are negative.

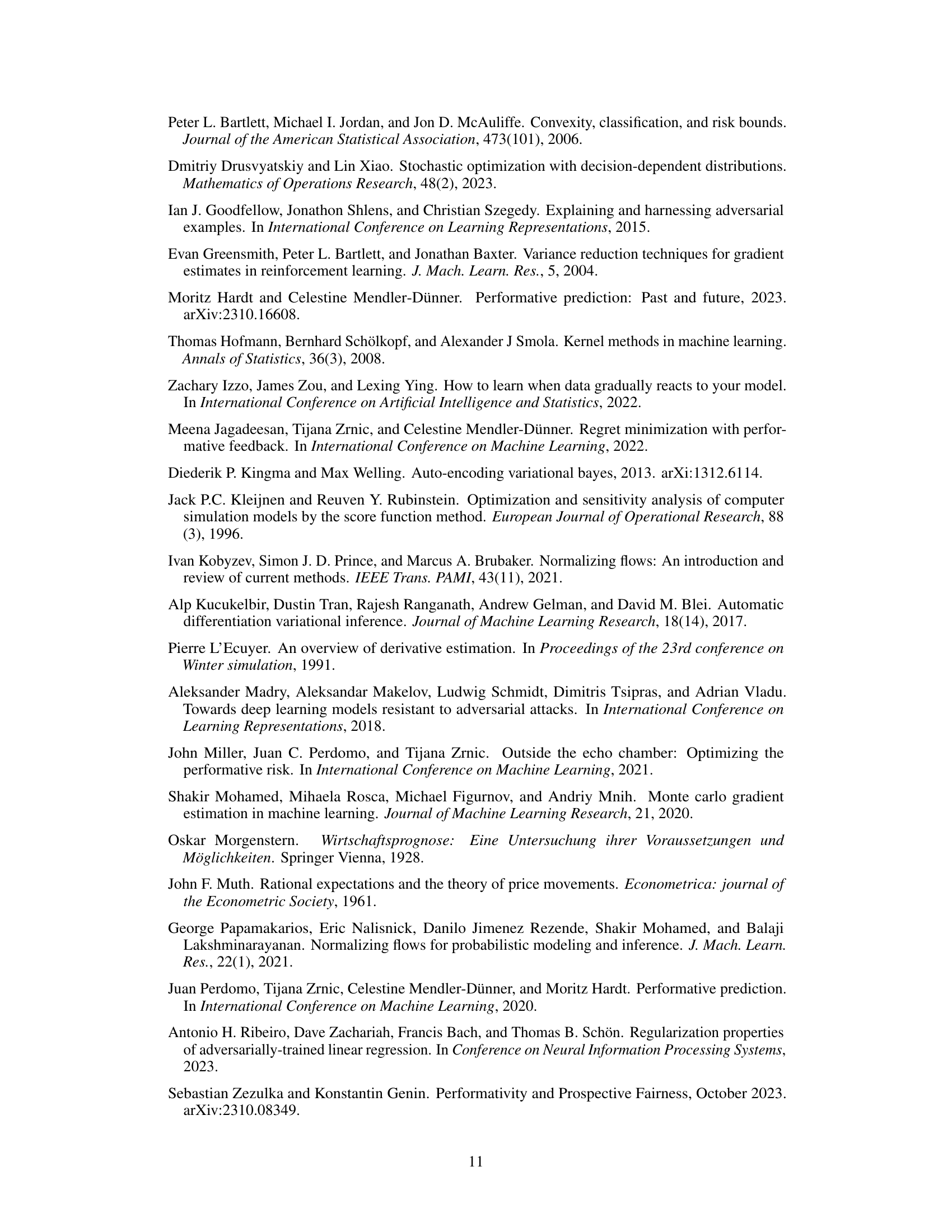

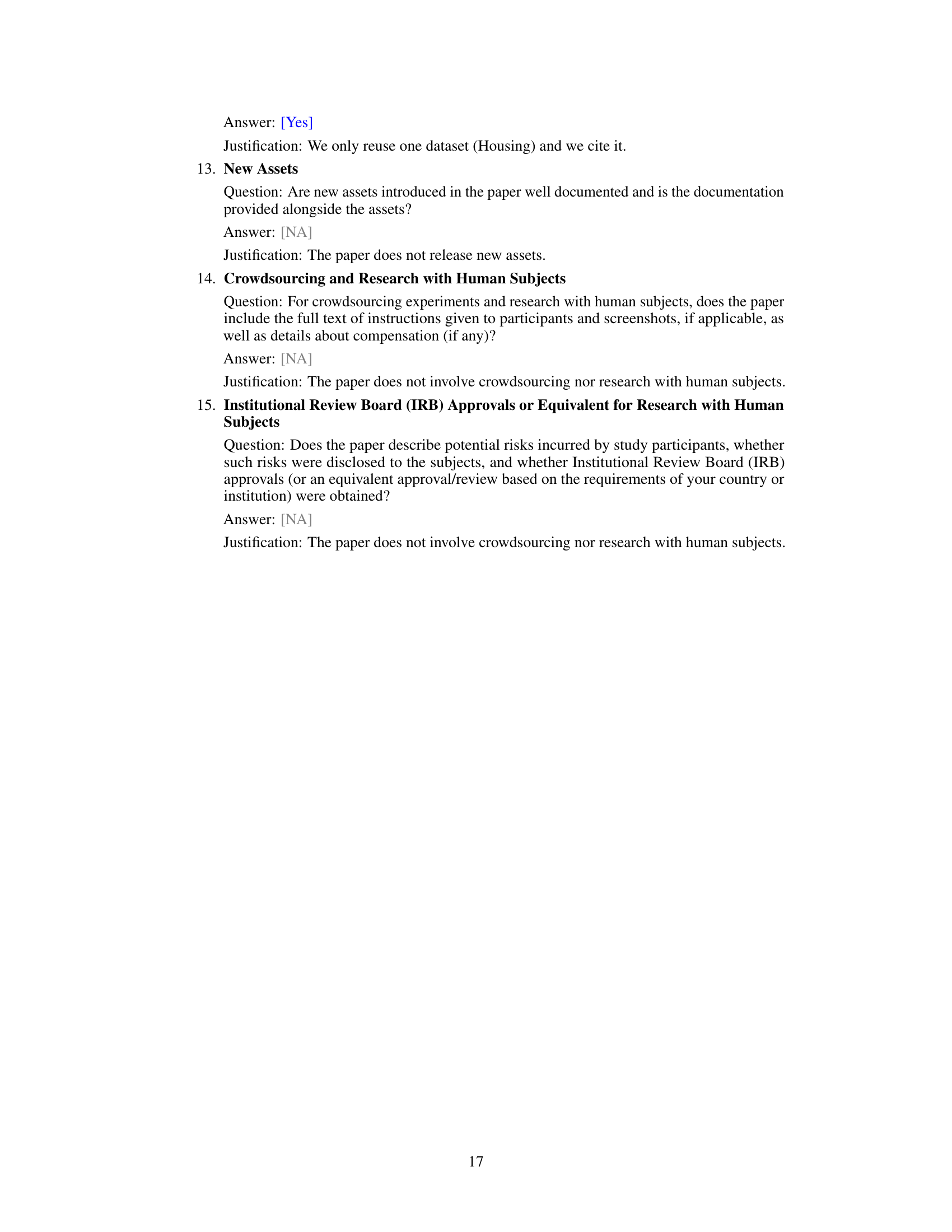

This table lists the hyperparameters used to generate Figure 2b of the paper. The figure shows the trajectory of model parameters in a 2D space under different learning algorithms. The hyperparameters control aspects of the learning process, including the number of iterations, sample size, scaling factor, and regularization parameter.

In-depth insights#

Performative Risk#

The concept of “Performative Risk” is central to the study of performative prediction, where a model’s predictions influence the very data it learns from, creating a feedback loop. The risk isn’t simply the model’s error rate on a static dataset; it’s a dynamic measure that accounts for how the model’s deployment alters the data distribution. This dynamic aspect introduces significant challenges for traditional machine learning approaches. Models trained to minimize standard risk may perform poorly in practice due to unforeseen changes induced by their predictions. The research highlights the need for novel methods that explicitly account for this performative feedback, suggesting innovative gradient estimation techniques and pushing the boundaries of convexity analysis in such scenarios. A key contribution is the use of push-forward measures to model performative effects, leading to more efficient and scalable learning strategies. The paper also links performative risk minimization to adversarial robustness, offering a fresh perspective and potentially valuable connections between these fields. The concept of stable points versus performatively optimal points is also discussed. Ultimately, understanding and mitigating performative risk is crucial for deploying reliable and beneficial AI systems in real-world applications.

Push-forward Models#

The concept of ‘Push-forward Models’ in the context of performative prediction offers a novel perspective on how algorithmic decisions can alter data distributions. Instead of directly modeling the complex interplay between predictions and data changes, this approach elegantly represents the performative effect as a transformation (push-forward) of the original data distribution. This simplifies the modeling process significantly, allowing for more efficient and scalable learning strategies, especially in higher dimensions. The framework leverages the power of change-of-variable techniques, enabling seamless integration with other statistical models like VAEs or normalizing flows. A key advantage lies in the reduced need for complete specification of the shifted distribution, requiring only the knowledge of the transformation operator. This makes it applicable in real-world scenarios where perfect data distribution characterization is practically impossible. Furthermore, the push-forward approach facilitates the development of more efficient gradient estimation methods for optimizing the performative risk, leading to more accurate and robust models capable of handling strong performative effects.

Convexity Analysis#

A convexity analysis within a machine learning context often centers on the objective function’s shape. Convexity guarantees that any local minimum is also a global minimum, simplifying optimization. In the context of performative prediction, where model outputs influence data distribution, the analysis becomes considerably more intricate. The paper likely investigates the convexity of the performative risk, which is a function of model parameters and the data distribution shaped by the model itself. Establishing convexity of this risk is crucial for ensuring that optimization algorithms reliably converge to the best possible model under these performative effects. The analysis likely involves deriving conditions under which the performative risk is convex, potentially exploring different loss functions and types of performative feedback mechanisms. Assumptions about the nature and strength of the performative effect are key in determining convexity, with stronger effects potentially breaking the convexity property. The analysis might reveal that only under specific, potentially restrictive, conditions is convexity guaranteed, highlighting the challenges in optimizing models subject to performative shifts. Furthermore, the analysis could explore the relationship between convexity and other desirable properties, such as stability or robustness of the model. The convexity analysis provides a critical theoretical foundation for developing effective learning strategies in the face of performative feedback loops.

Robustness Links#

The concept of “Robustness Links” in the context of performative prediction suggests a crucial connection between the robustness of a model and its ability to handle performative shifts. A robust model, resistant to adversarial attacks or noisy data, is inherently better equipped to adapt to changes in data distribution caused by its own predictions. This link implies that techniques for improving model robustness can be directly leveraged to enhance its performance under performative settings. This is particularly relevant because performative prediction often leads to feedback loops, where model predictions influence future data, thus requiring adaptability. Conversely, analyzing the performance of models under performative shifts offers insights into their underlying robustness. Therefore, the exploration of “Robustness Links” could significantly improve our understanding of both robustness and performative prediction, leading to more reliable and adaptable machine learning systems. Investigating this link could also suggest new strategies for designing models that are robust to both adversarial attacks and performative shifts.

Empirical Testing#

An empirical testing section in a research paper on performative prediction would ideally involve a rigorous evaluation of the proposed methods. This would likely encompass experiments on both synthetic and real-world datasets, allowing for controlled comparisons under various conditions. The choice of datasets should be justified, highlighting their relevance to the problem of performative prediction. Key metrics for assessing performance (e.g., accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, AUC, etc.) need to be clearly defined and their interpretation discussed. Importantly, a thorough comparison with relevant baseline methods is crucial to demonstrate the effectiveness of the novel approach. The analysis should go beyond simple performance figures, exploring the behavior of the algorithms under different levels of performative effect strength, dataset characteristics, and hyperparameter settings. Statistical significance testing is essential to ensure that observed differences are not merely due to random chance. A robust empirical evaluation is critical for establishing the practical value of the proposed techniques and advancing the field of performative prediction.

More visual insights#

More on figures

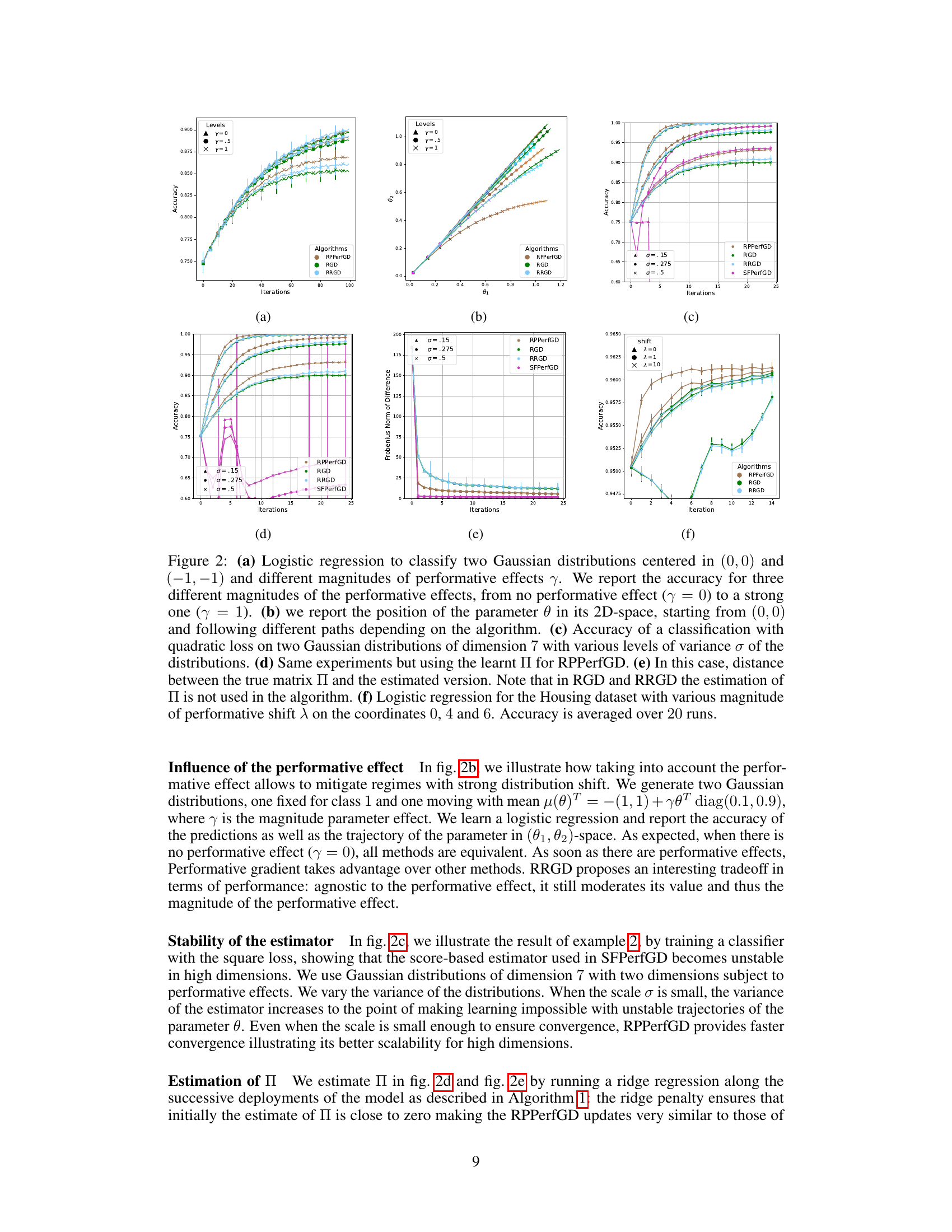

This figure displays the results of several experiments evaluating the performance of different algorithms (RPPerfGD, RGD, RRGD, SFPerfGD) under different scenarios. Subfigure (a) shows the accuracy of logistic regression for classifying two Gaussian distributions with varying strengths of performative effects. Subfigure (b) visualizes the parameter trajectories in a 2D parameter space. Subfigure (c) illustrates classification accuracy with varying data variance, while subfigure (d) repeats the experiment using a learned parameter. Subfigure (e) shows the difference between the true and estimated parameters. Finally, subfigure (f) demonstrates the performance on the Housing dataset with varying levels of performative shift.

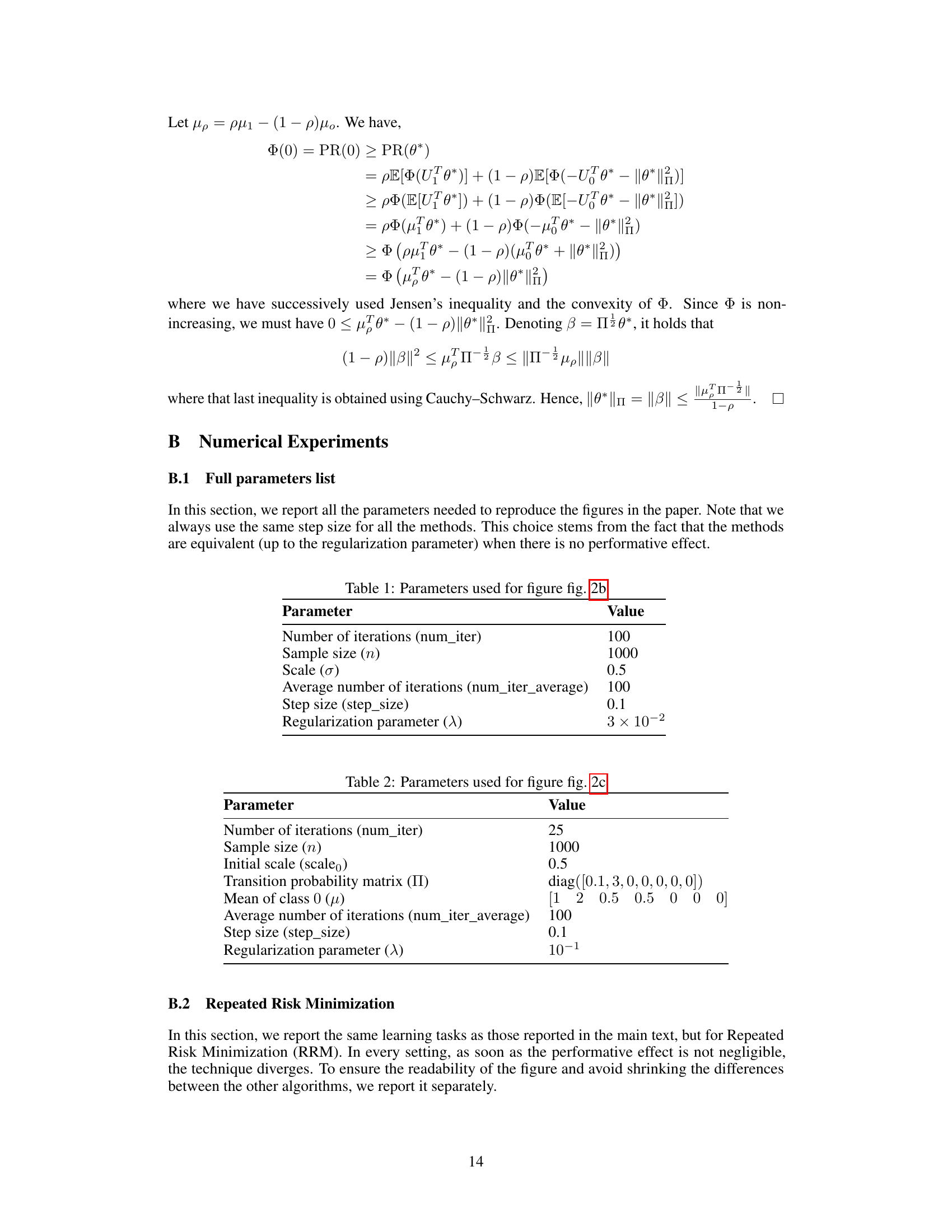

Figure 3 shows the result of using the Repeated Risk Minimization (RRM) algorithm on two different tasks. Subfigure (a) illustrates the algorithm’s performance in a logistic regression task with two Gaussian distributions, varying the magnitude of performative effects (γ). The plot shows the accuracy over iterations for three different levels of performative effects. Subfigure (b) demonstrates the algorithm’s performance in a classification task with a quadratic loss, varying the noise level (σ) in two 7-dimensional Gaussian distributions. Both subfigures show that RRM performs poorly in the presence of even moderate performative effects or noise.

More on tables

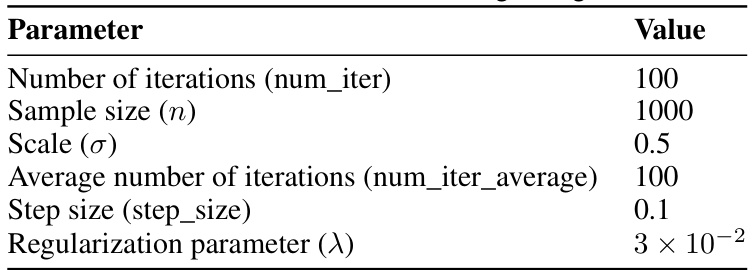

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the experiment in Figure 2c of the paper. The parameters control aspects of the simulation, including the number of iterations, sample size, initial scale, transition probability matrix, mean of class 0, average number of iterations, step size, and regularization parameter.

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the experiment shown in Figure 2f of the paper. It includes the number of iterations, sample size, number of runs, step size, and regularization parameter used in the logistic regression model for the Housing dataset.

Full paper#