↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current 3D face reconstruction struggles with accurately recovering facial textures from images with complex illumination caused by occlusions (e.g., hats, hair). Existing methods assume uniform lighting, failing to properly handle these scenarios. This leads to unrealistic textures with baked-in shadows, hindering the creation of lifelike digital humans.

This paper introduces ‘Light Decoupling’, a novel framework that addresses this issue. Instead of assuming single lighting, it learns to model complex illumination as a combination of multiple lighting conditions using neural representations. Experiments on images and video sequences demonstrate that Light Decoupling effectively recovers accurate facial textures, even under challenging illumination with occlusions, producing significantly more realistic results than existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to 3D face texture modeling that addresses the limitations of existing methods in handling complex illumination scenarios. It offers a solution for generating more realistic facial textures, which has implications for various applications, including virtual reality, animation, and forensics. The proposed method’s effectiveness is validated through extensive experiments, establishing it as a valuable contribution to the field. The introduction of neural representations for light decoupling opens new avenues for research in handling challenging illumination conditions and improving the quality of 3D face modeling.

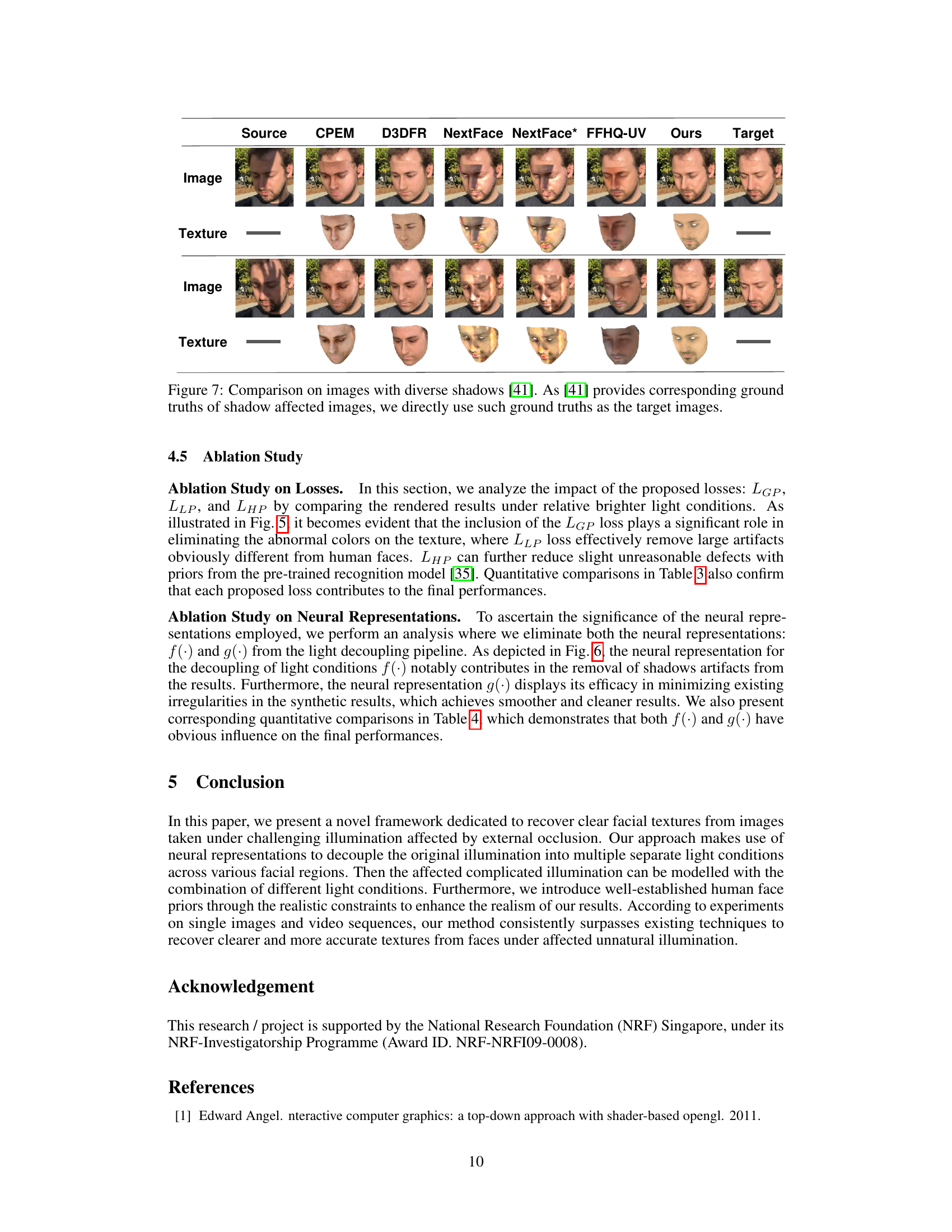

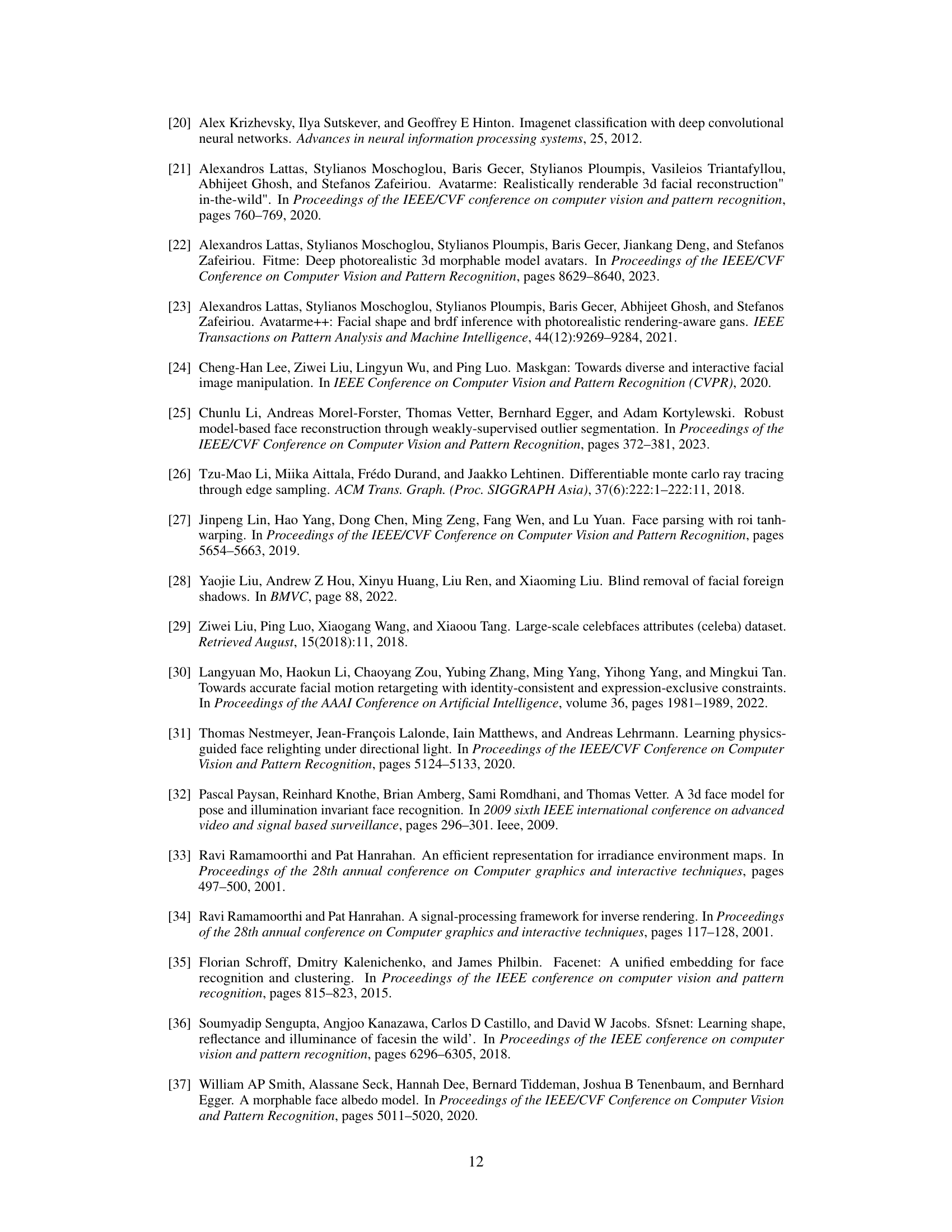

Visual Insights#

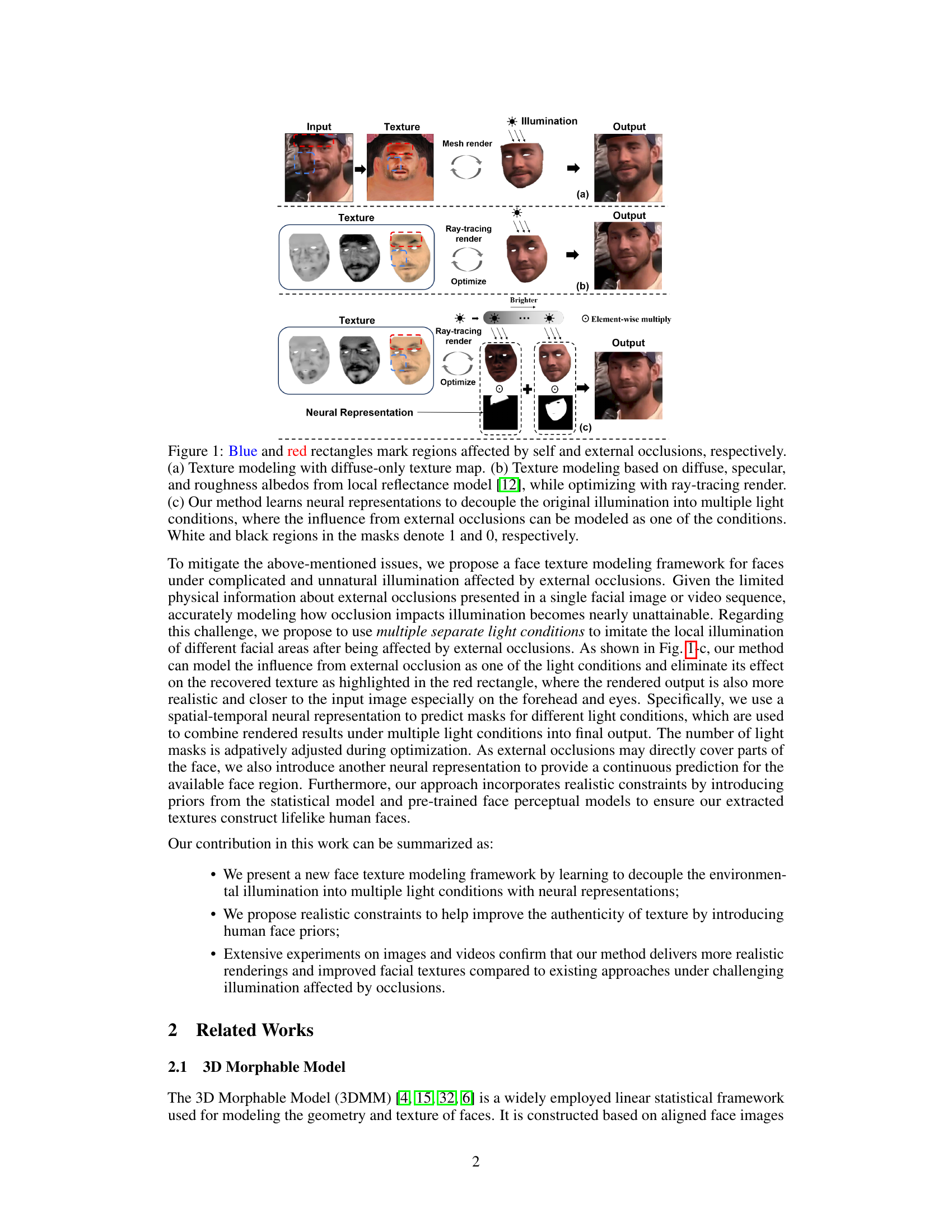

This figure compares three different approaches for 3D face texture modeling under challenging illumination conditions caused by self-occlusions (e.g., nose) and external occlusions (e.g., hat). (a) shows a method using only diffuse texture, resulting in unrealistic shadows. (b) shows a method using a local reflectance model with ray tracing, improving realism but still struggling with external occlusions. (c) illustrates the proposed ‘Light Decoupling’ method, which uses neural representations to separate different light conditions and model the influence of occlusions more effectively, leading to more realistic results.

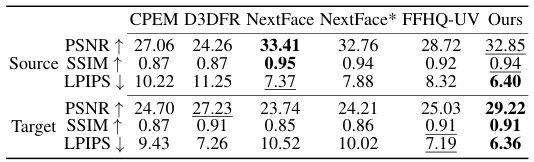

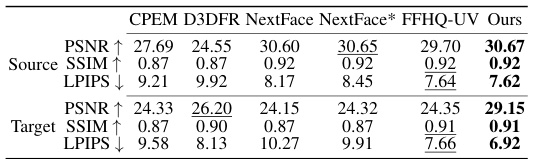

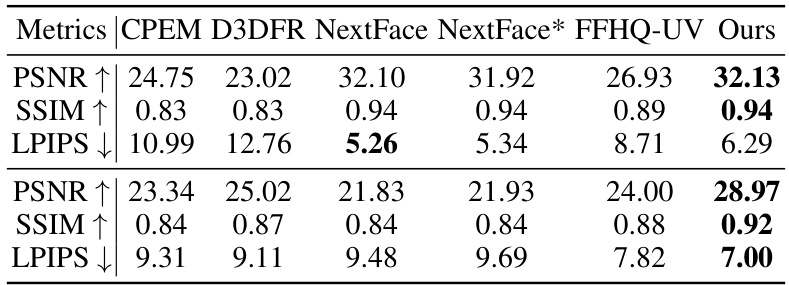

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different face reconstruction methods on single images from the VoxCeleb2 dataset. It compares the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) metrics for both the reconstructed source images (Source) and the synthesized target images (Target). The best results for each metric are bolded, and the second-best are underlined. The LPIPS scores are multiplied by 100 for easier interpretation.

In-depth insights#

Light Decoupling#

The concept of “Light Decoupling” in 3D face texture modeling addresses the challenge of reconstructing accurate facial textures from images with complex illumination affected by occlusions. Instead of assuming a single, uniform light source, this innovative approach models unnatural illumination as a combination of multiple separate light conditions. Each condition is learned through neural representations, effectively decoupling the intertwined effects of various light sources and shadows. This allows for a more accurate modeling of facial textures even when portions of the face are obscured. The method’s strength lies in its ability to disentangle the influence of self-occlusions (like a nose casting a shadow) from external occlusions (like a hat), leading to more realistic and authentic 3D face reconstructions. By separating these lighting effects, the algorithm can better recover detailed textures in the shadowed regions, improving the overall quality and fidelity of the final 3D model. The use of multiple light masks combined with neural networks is crucial for the success of this technique, enabling adaptive adjustment and accurate rendering of the facial features.

Neural Representation#

The concept of ‘Neural Representation’ in this context likely refers to the use of artificial neural networks to learn and encode complex patterns and relationships within facial images, particularly concerning illumination variations and occlusions. The authors likely leverage neural networks to map input image data (pixels, potentially with spatial and temporal information from video sequences) to learned representations capturing the essence of different lighting conditions affecting the face. This decoupling of illumination is a crucial aspect, enabling the model to separate the inherent facial texture from the confounding effects of shadows and unusual lighting scenarios. The network likely learns to predict masks or weights associated with various illumination components, essentially representing the illumination as a composition of learned factors rather than assuming a single, uniform lighting model. This sophisticated approach allows for a more realistic and accurate reconstruction of facial textures, even in challenging imaging conditions. The effectiveness hinges on the network’s ability to disentangle the complex interactions between texture and lighting, leading to improved results compared to methods relying on simpler illumination models.

3DMM Framework#

The 3D Morphable Model (3DMM) constitutes a cornerstone in 3D face modeling, offering a linear statistical framework to represent the geometry and texture of human faces. Its strength lies in its ability to generate realistic 3D faces by linearly combining a set of basis shapes and textures derived from a large dataset of aligned face images via Principal Component Analysis (PCA). This approach allows for efficient representation and manipulation of facial features, making it ideal for applications like face reconstruction, animation, and synthesis. However, the inherent linearity of the 3DMM limits its capacity to capture subtle details and non-linear variations in facial appearance, especially under complex lighting and occlusions. Recent advancements have explored non-linear extensions, integrating deep learning techniques to overcome these limitations and achieve higher fidelity results. Despite its limitations, 3DMM’s versatility and efficiency remain highly relevant to the field, providing a foundational model that’s regularly enhanced and improved upon.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model or system to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a research paper, it’s crucial for validating claims and isolating the effects of specific design choices. A well-executed ablation study demonstrates the necessity of each component by showing a degradation in performance when that component is removed. The findings should provide insight into the relative importance of different features or techniques within the overall system, enabling researchers to focus improvements on the most impactful elements. It’s vital that the ablation study considers all significant factors; otherwise, the results might be misleading. Furthermore, the design must be controlled to avoid unintended side effects from interactions between removed components. The results of an ablation study can be presented quantitatively through metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision) and/or qualitatively through visualizations or descriptions, allowing for a multifaceted understanding of the individual parts’ impact on the whole. A robust ablation study is a cornerstone of rigorous research, strengthening the credibility and understanding of the proposed methods.

Future Works#

Future work could explore several promising directions. Improving the robustness of the light decoupling framework to handle even more challenging illumination conditions, such as extreme shadows or complex reflections, is crucial. Investigating alternative neural architectures, perhaps leveraging more advanced techniques like transformers or graph neural networks, could lead to more accurate and efficient light decomposition. Enhancing the realism of the generated textures is another important goal. This could involve incorporating more sophisticated texture models that capture fine details and material properties or using generative adversarial networks to refine the textures. Finally, expanding the application of the framework beyond facial texture modeling to other areas such as object recognition or image synthesis under complex lighting conditions would be a significant contribution. The use of a pre-trained face model introduces a dependency that should be addressed by a fully self-supervised system in the future. Investigating fully self-supervised approaches would improve generalizability and adaptability.

More visual insights#

More on figures

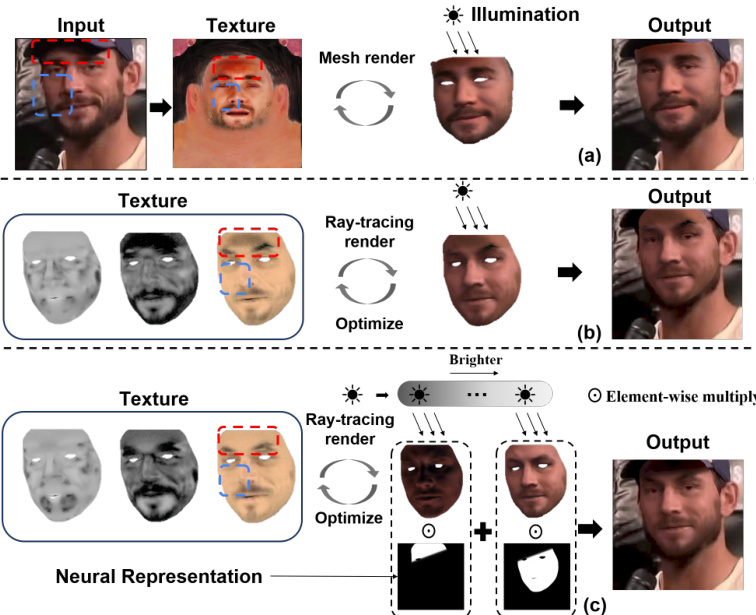

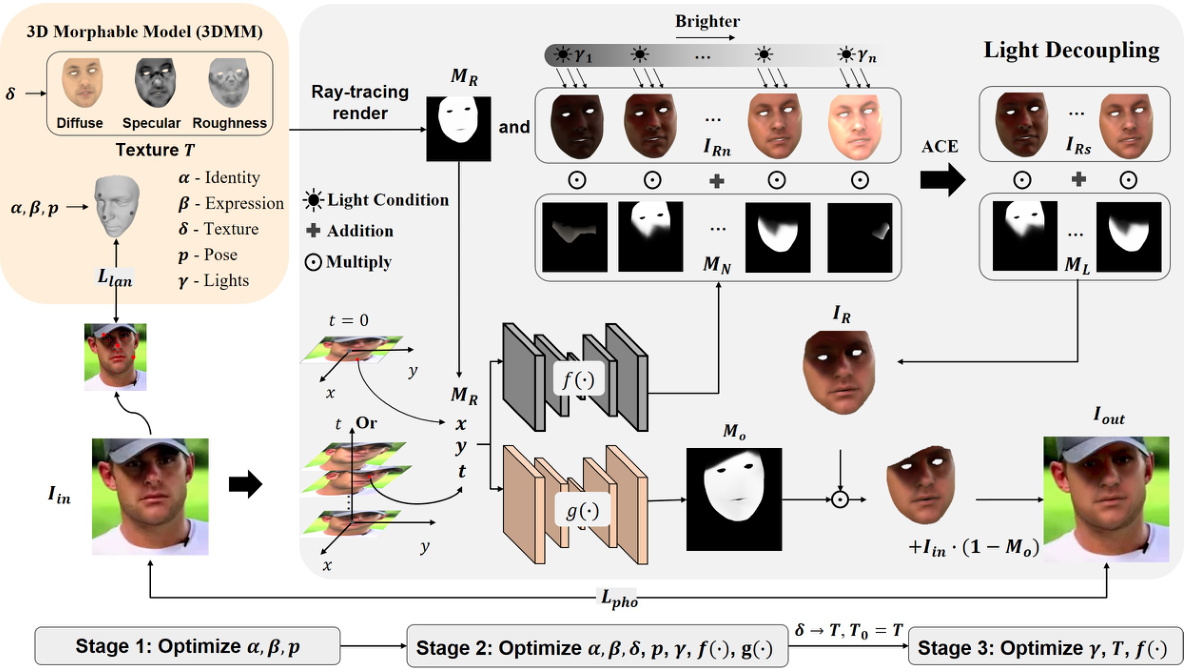

This figure illustrates the proposed face texture modeling framework. It starts with an input image and uses a 3D Morphable Model (3DMM) to initialize the texture. Ray tracing is used to render the face under multiple light conditions, and neural networks predict masks for these conditions. An adaptive condition estimation (ACE) strategy selects the most effective masks and rendered faces, which are combined to generate the final output. The process involves optimizing various parameters (shape, expression, pose, lights, texture) in three stages.

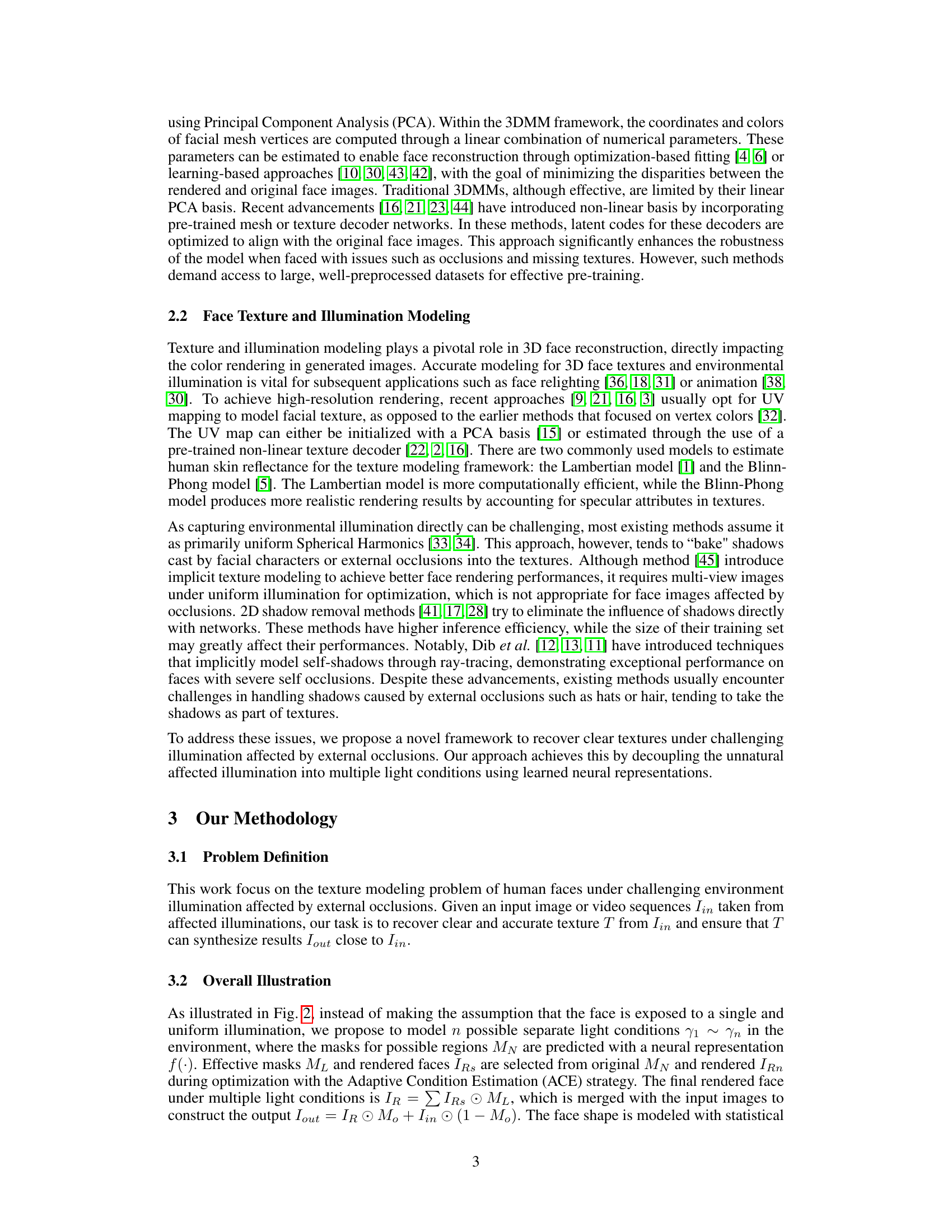

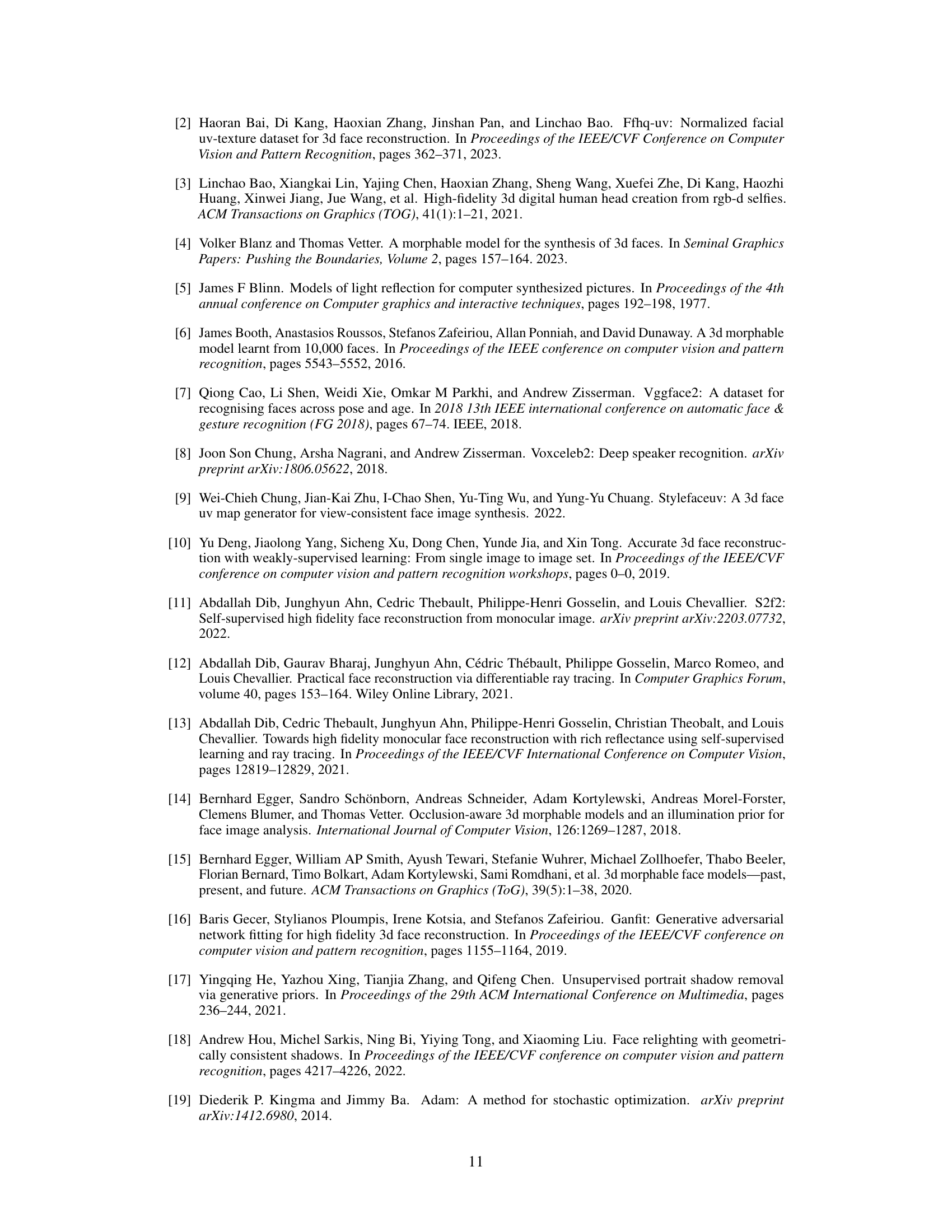

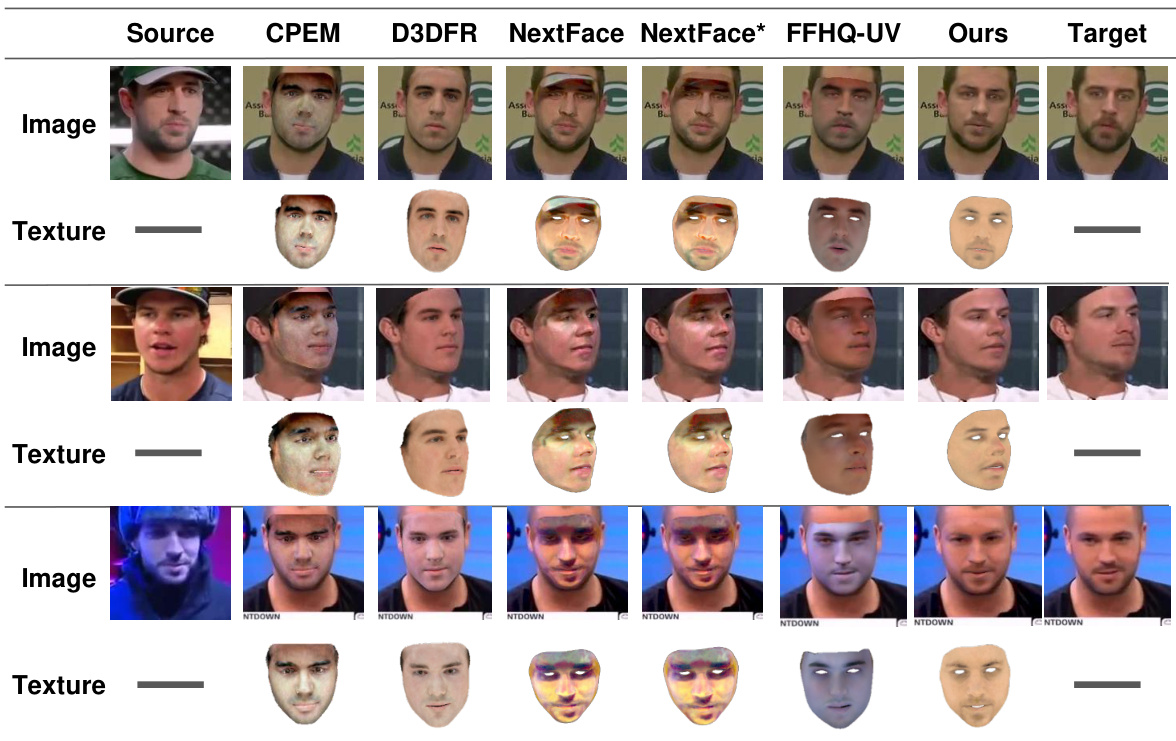

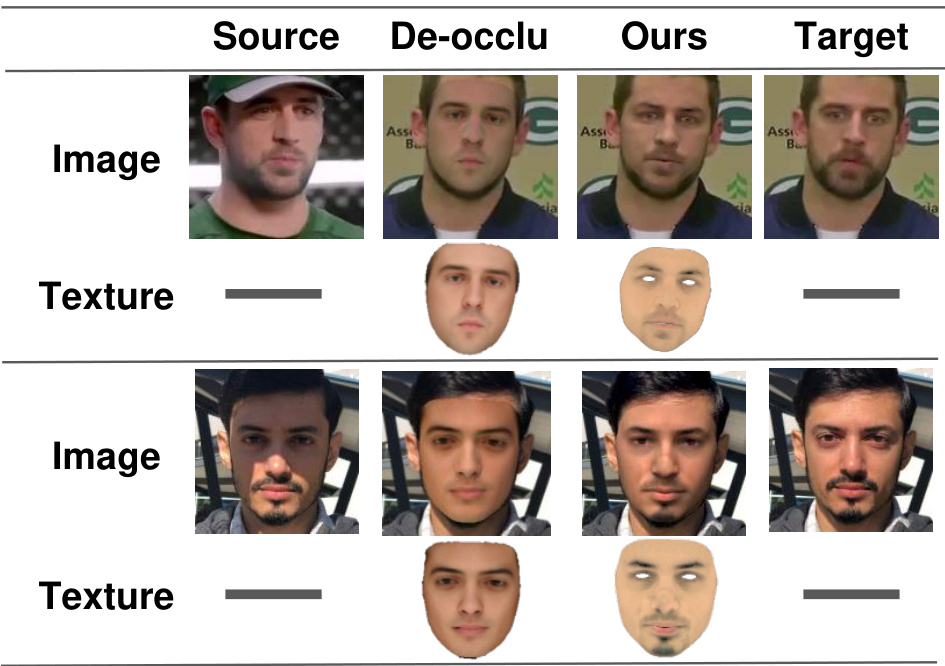

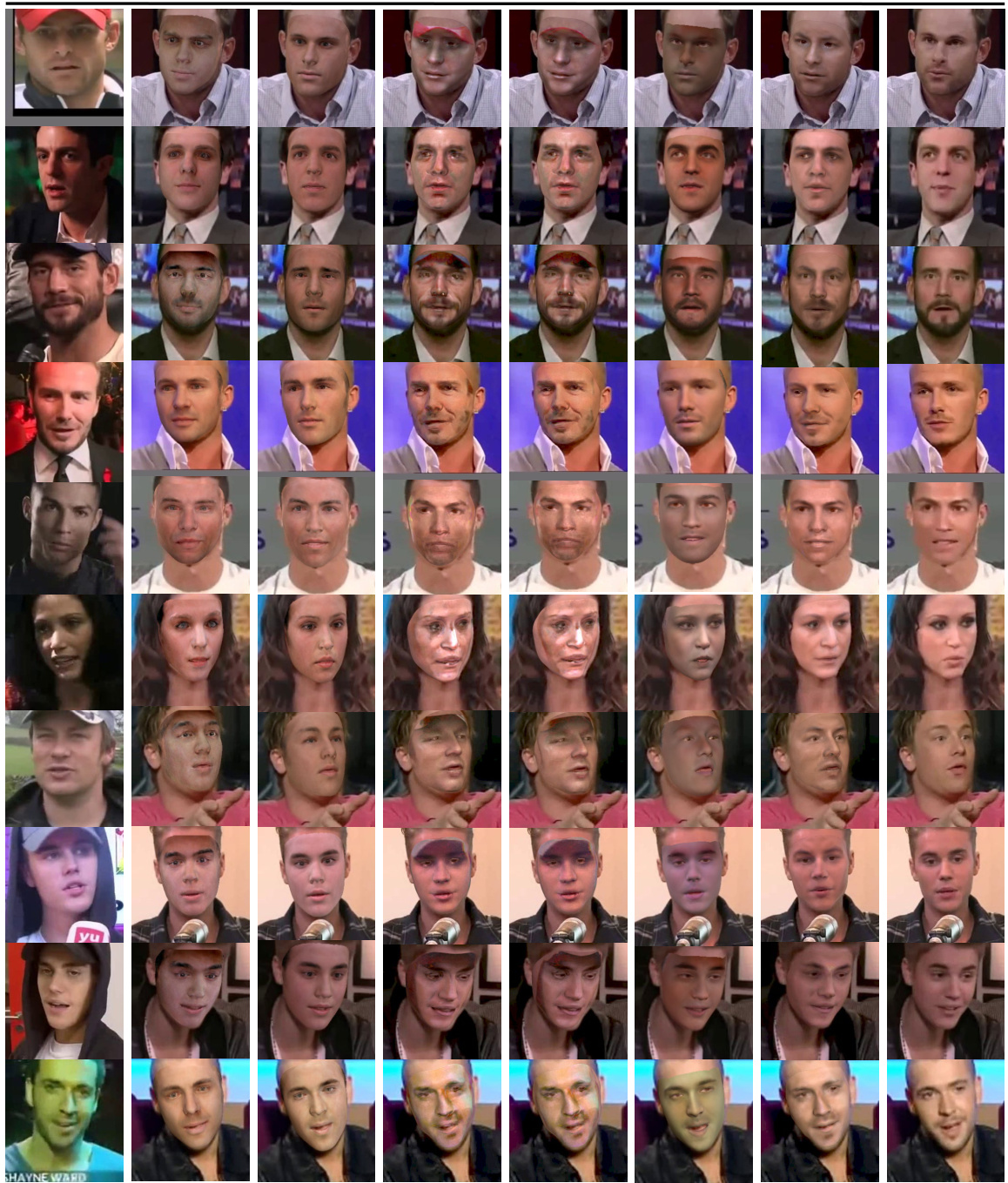

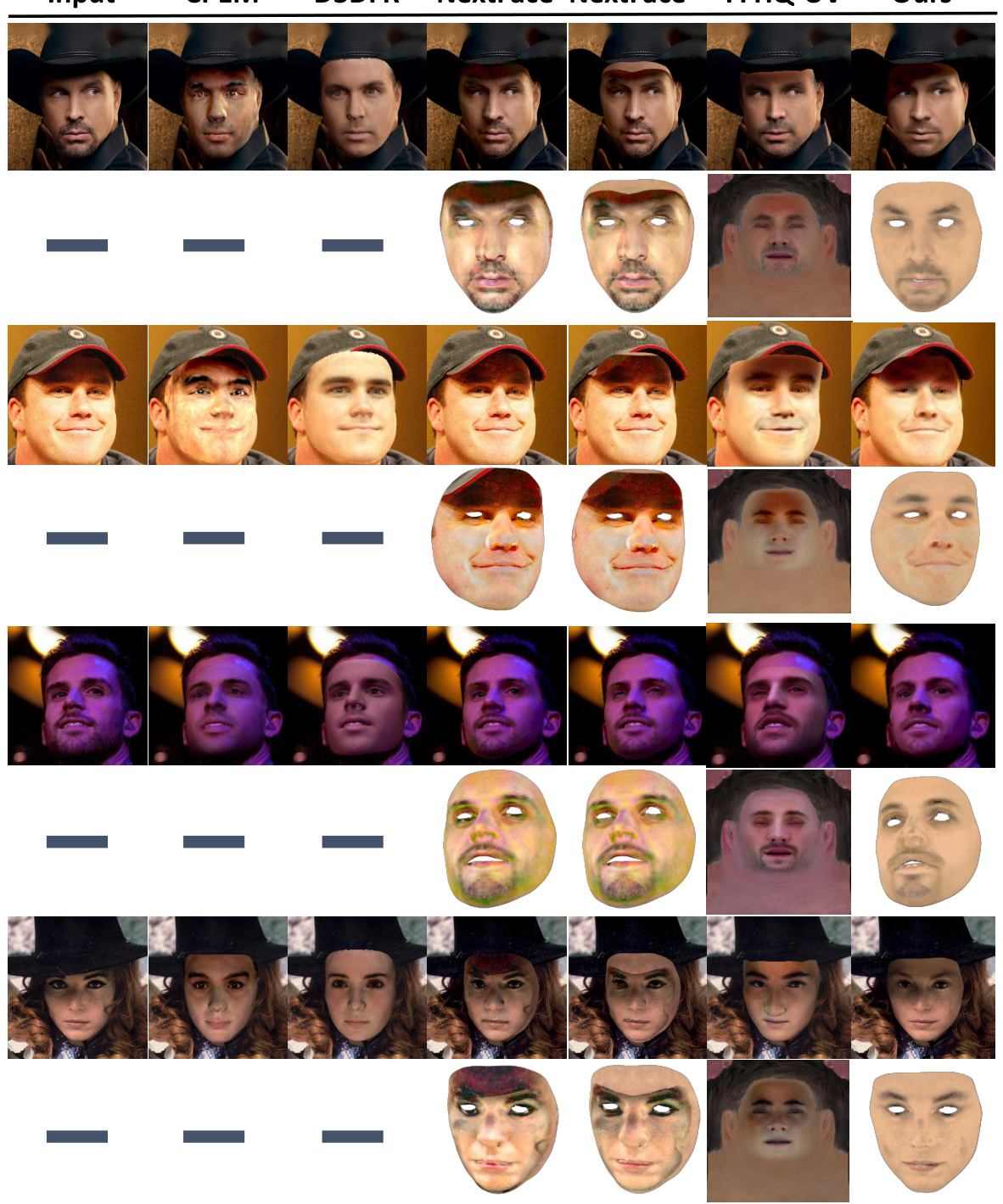

This figure compares the performance of different methods (CPEM, D3DFR, NextFace, NextFace*, FFHQ-UV, Ours) on the VoxCeleb2 dataset for 3D face texture reconstruction. It visualizes the reconstructed textures (diffuse albedo) and corresponding images. NextFace* indicates results where face parsing was used to refine the regions of optimization. The methods are evaluated on their ability to recover accurate facial textures in challenging conditions (illumination changes, occlusions). The target images show what the ideal reconstruction should be.

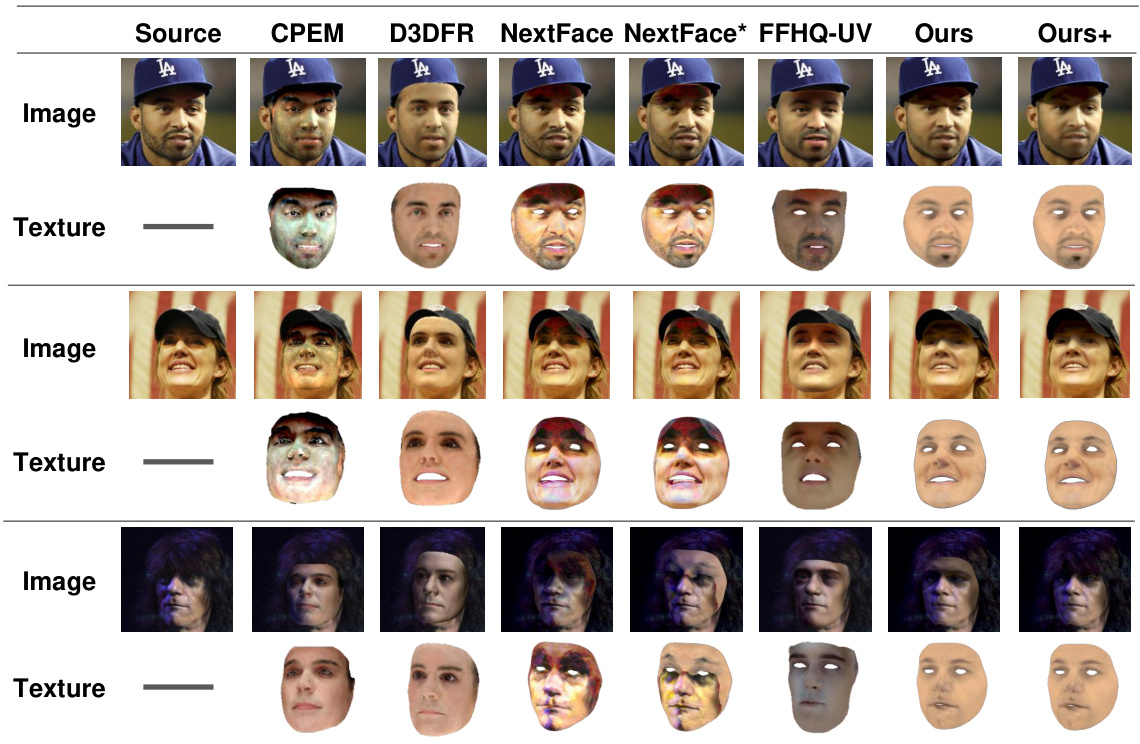

This figure compares the performance of different methods (CPEM, D3DFR, NextFace, NextFace*, FFHQ-UV, and the proposed method) on the Voxceleb2 dataset. The comparison focuses on the quality of reconstructed facial textures under challenging illumination conditions. The diffuse albedo is used as a representation of the texture, and the results are shown for both source and synthesized target images. NextFace* represents the results optimized only on the facial region, obtained using face parsing.

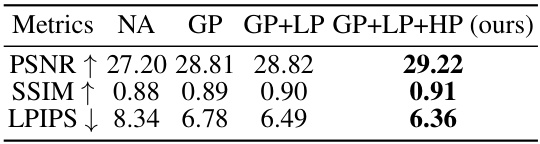

This figure shows an ablation study on the proposed loss functions: Global Prior Constraint (GP), Local Prior Constraint (LP), and Human Prior Constraint (HP). It presents visual comparisons of facial texture reconstruction results with different combinations of these losses included or excluded. The ‘NA’ column indicates that none of these loss functions were used, showcasing the importance of each individual constraint and their combined contribution to realistic facial texture generation.

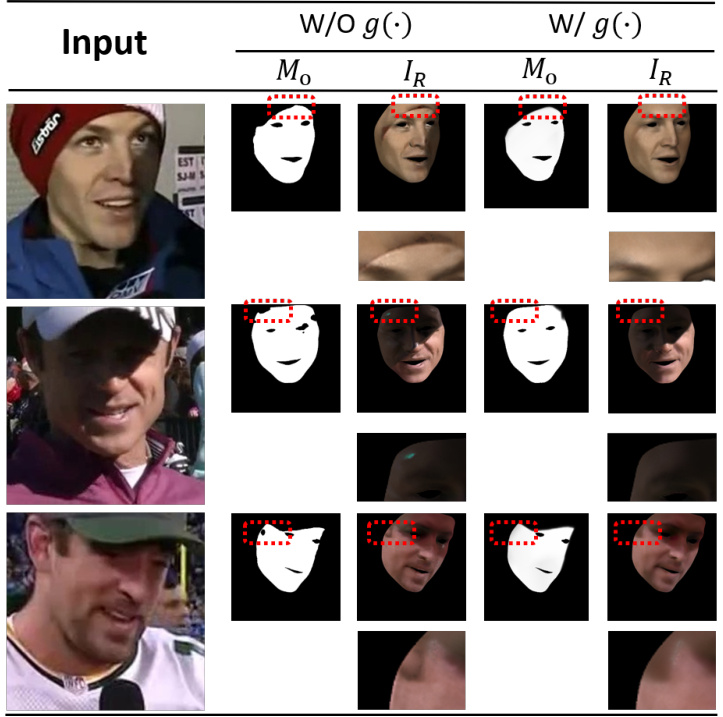

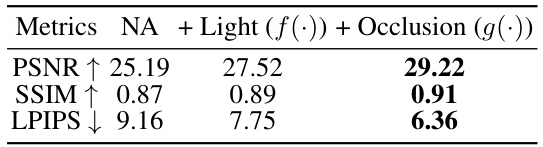

This ablation study analyzes the impact of the neural representations, f(·) and g(·), on the model’s performance. The ‘NA’ column shows the results without either neural representation. The ‘+ Light’ column shows the results with only f(·) (which models the effects of different lighting conditions), and the ‘+ Occlusion’ column shows the results with both f(·) and g(·) (where g(·) models the effects of occlusions). The results demonstrate the individual contributions of each component in improving the quality of the recovered facial textures. Comparing the results across these conditions reveals how each neural representation helps to address different challenges in handling complex illumination scenarios, thereby improving the accuracy and realism of the generated face textures.

This figure compares the performance of different face reconstruction methods on the VoxCeleb2 dataset. The methods are compared based on their ability to recover accurate facial textures from images with challenging illumination conditions, particularly those affected by occlusions (e.g., shadows from hats or hair). The comparison focuses on the diffuse albedo (texture), visualizing the quality of texture reconstruction by each method. NextFace* represents a modified version of the NextFace method that uses face parsing to better isolate the face region before optimization, improving results. The figure highlights the limitations of certain methods that only predict vertex colors, rather than UV textures.

This figure shows three different approaches to 3D face texture modeling under challenging lighting conditions caused by self-occlusions (e.g., nose) and external occlusions (e.g., hat). (a) represents a traditional method using only diffuse textures, resulting in unrealistic shadows. (b) shows an improved method using diffuse, specular, and roughness albedos, handling self-occlusions better but still struggling with external occlusions. (c) illustrates the proposed method, which uses neural networks to decouple the lighting conditions into multiple separate light conditions. This allows for better modeling of both self and external occlusions, resulting in more realistic textures.

This figure shows the ablation study on the effect of the neural representation g(·) on the final texture result. The weight w2 controls the strength of the constraint on g(·). As w2 decreases, the constraint loosens, resulting in weakened shadows and details in the reconstructed texture. The red rectangles highlight the regions affected by shadows, while the black rectangles indicate the detailed texture regions.

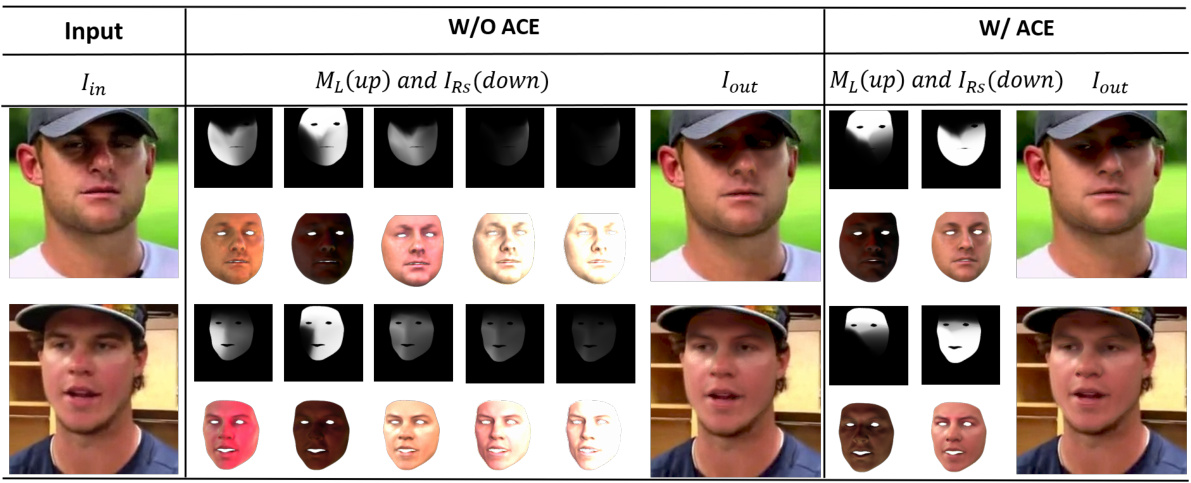

This figure shows an ablation study on the impact of the Larea and Lbin loss functions in the Adaptive Condition Estimation (ACE) process. It compares results with neither loss, only Larea, and both Larea and Lbin. The results show that both losses are needed for optimal performance; Larea removes redundant masks, while Lbin ensures consistency of light conditions with the input.

This figure compares the performance of different methods on the Voxceleb2 dataset for 3D face texture reconstruction. It shows the input image with occlusions, the reconstructed textures, and the final rendered images for each method, including CPEM, D3DFR, NextFace, NextFace* (using face parsing), FFHQ-UV, and the proposed ‘Ours’ method. The target images are synthesized from source images to quantitatively evaluate the texture quality. The authors note limitations in obtaining textures for some methods because they don’t use the same representation (e.g. vertex colors instead of UV textures).

This figure compares three different approaches to 3D face texture modeling under challenging illumination conditions caused by self-occlusions (e.g., nose) and external occlusions (e.g., hat). (a) shows a traditional diffuse-only texture model, which fails to accurately reconstruct textures in occluded regions. (b) demonstrates a more advanced approach using local reflectance modeling and ray-tracing rendering, showing improved realism but still struggles with external occlusions. (c) illustrates the proposed method, which uses light decoupling and neural representations to model unnatural illumination as a combination of multiple light conditions, successfully handling both self and external occlusions.

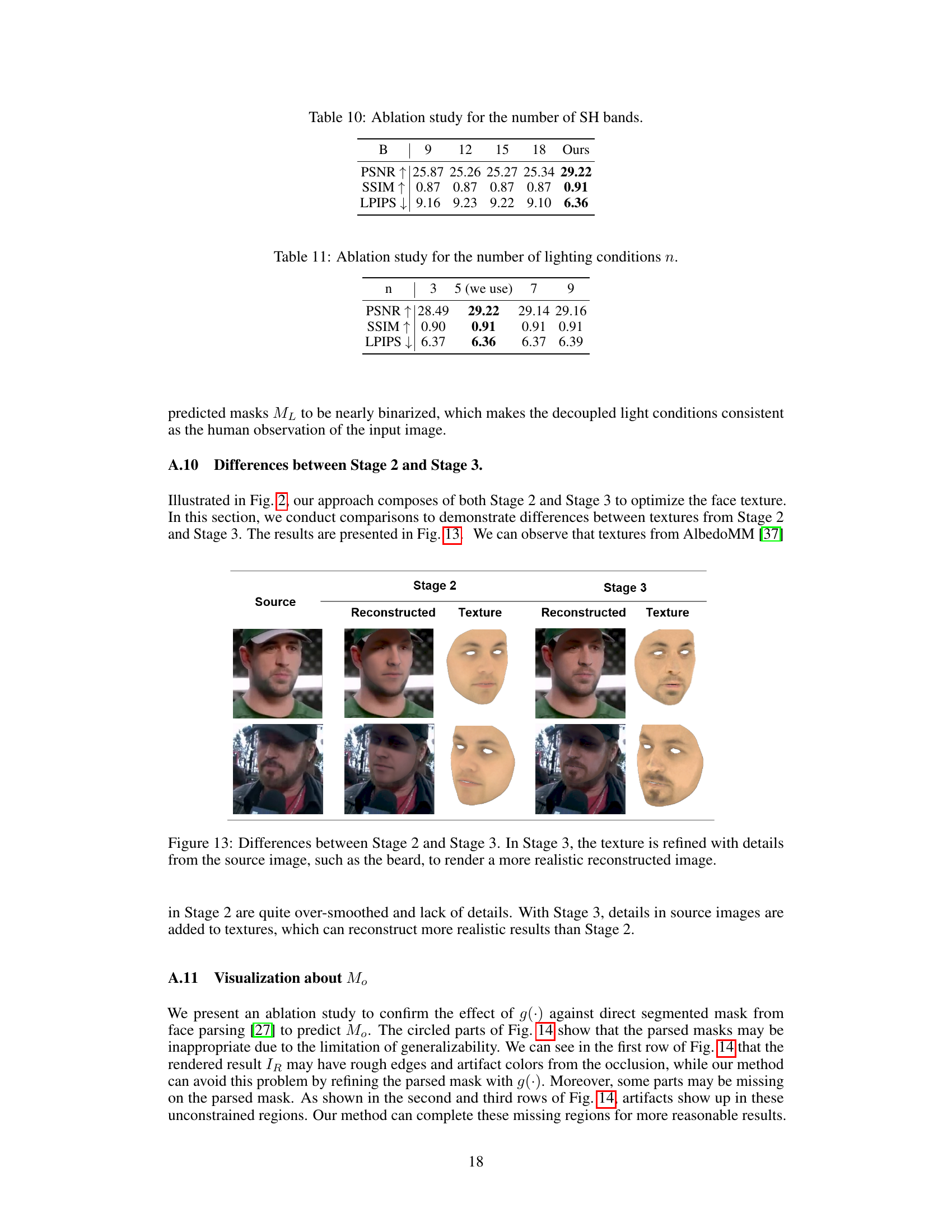

This figure compares the results of face reconstruction and texture generation at Stage 2 and Stage 3 of the proposed method. Stage 2 shows results using only the statistical model, which results in smooth, less detailed textures. Stage 3 incorporates details from the input image to refine the texture, resulting in a more realistic representation.

This figure shows an ablation study on the Adaptive Condition Estimation (ACE) method, specifically focusing on the impact of the Larea and Lbin loss functions. It compares results with both loss functions included, with only Larea, and with neither. The red boxes highlight regions where the effects of the loss functions are evident.

This figure shows a comparison of three different approaches for 3D face texture modeling under challenging illumination conditions caused by self-occlusions (e.g., nose) and external occlusions (e.g., hat). (a) shows a traditional method using only diffuse texture, resulting in unrealistic shadows. (b) shows a more advanced method using diffuse, specular, and roughness albedos, which improves the realism but still struggles with external occlusions. (c) presents the proposed method which uses neural representations to decouple the illumination into multiple components, effectively handling both self and external occlusions.

This figure shows an ablation study on the impact of Adaptive Condition Estimation (ACE) in the proposed method. The left side demonstrates the results without ACE, where the initial masks (MN) and renderings (IRn) under multiple lighting conditions are directly used. The right side shows the results with ACE, where the algorithm selects the most effective masks (ML) and renderings (IRS) for optimal results. The figure aims to highlight ACE’s role in refining the selection of lighting conditions and improving the final output.

This figure compares the performance of different methods on the Voxceleb2 dataset for 3D face texture reconstruction. The comparison is made by visualizing the diffuse albedo as the texture, and using source images to synthesize target images. NextFace* represents results from NextFace, but with face parsing to select optimization regions. The methods CPEM and D3DFR are not included because they do not produce UV textures.

This figure compares the performance of different 3D face reconstruction methods on the VoxCeleb2 dataset. The methods are compared based on their ability to reconstruct facial textures from images with challenging illumination and occlusions. The figure shows the input image, the reconstructed textures, and the final rendered images for each method. The results demonstrate that the proposed method outperforms existing methods in terms of texture quality and realism.

This figure compares the performance of different methods in reconstructing facial textures from Voxceleb2 images. The top row shows the input images, while the subsequent rows display the recovered textures and images generated by each method. The comparison highlights the effectiveness of the proposed method in producing more realistic and accurate textures, especially in challenging scenarios with unnatural illumination.

More on tables

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods on single images from the Voxceleb2 dataset. It compares the performance of CPEM, D3DFR, NextFace, NextFace*, FFHQ-UV, and the proposed method (‘Ours’) in terms of PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS metrics. The comparison is done for both the reconstructed source images and the synthesized target images.

This table presents the quantitative results of an ablation study conducted on the proposed loss functions: Global Prior Constraint (GP), Local Prior Constraint (LP), and Human Prior Constraint (HP). The study evaluates the impact of each loss function on the overall performance of the face texture modeling framework, specifically looking at PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS. By incrementally adding each loss function, the table shows how each one contributes to improved performance. The ‘NA’ row indicates the performance without any of the proposed losses applied.

This table presents the results of an ablation study investigating the impact of the neural representations f(·) and g(·) on the performance of the proposed method. The study measures the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) metrics. The ‘NA’ row shows the performance when both neural networks are omitted. The ‘+ Light (f(·))’ row shows the performance when only the f(·) network is used. The ‘+ Occlusion (g(·))’ row shows the performance when both f(·) and g(·) networks are included. The results demonstrate the individual and combined contributions of these networks in achieving higher-quality facial texture reconstruction.

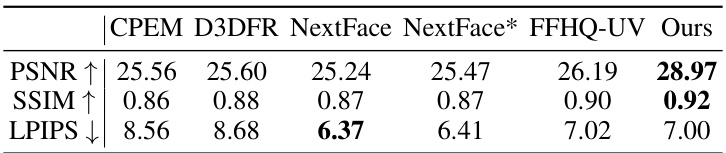

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for face image reconstruction on a dataset of images with diverse shadows. The metrics used for comparison are PSNR (higher is better), SSIM (higher is better), and LPIPS (lower is better). The methods being compared are CPEM, D3DFR, NextFace, NextFace*, FFHQ-UV, and the proposed method (Ours). The table shows the performance of each method on both source and target images. The ‘Source’ metrics evaluate the reconstruction quality on the source images, while the ‘Target’ metrics evaluate the ability of the method to generate realistic images (by comparing the generated images to the ground truth images).

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for face texture reconstruction on single images from the Voxceleb2 dataset. The metrics used are PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS (multiplied by 100), assessing the quality of both reconstructed source images and synthetic target images generated by each method. The best and second-best performing methods for each metric are highlighted.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for 3D face texture reconstruction, specifically focusing on images pre-processed using a 2D shadow removal technique. The methods compared include CPEM, D3DFR, NextFace, NextFace*, FFHQ-UV, and the authors’ proposed method. The metrics used for comparison are PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), SSIM (Structural Similarity Index), and LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity). Higher PSNR and SSIM values, and lower LPIPS values indicate better performance.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method’s performance on video sequences from the Voxceleb2 dataset. It compares the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) metrics for both the source (reconstructed) and target (synthesized) video sequences. Higher PSNR and SSIM values and lower LPIPS values indicate better performance. The comparison includes several state-of-the-art methods for context.

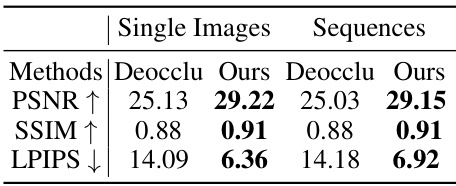

This table compares the performance of the proposed method against baselines using the deocclusion method on the Voxceleb2 dataset. The metrics used are PSNR (higher is better), SSIM (higher is better), and LPIPS (lower is better). The comparison is done for both single images and video sequences, showing that the proposed method achieves better results in most cases, particularly in terms of LPIPS which measures perceptual similarity.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods’ performance on single images from the Voxceleb2 dataset. It evaluates the quality of reconstructed source images and synthetic target images (generated by replacing the texture of a target image with the texture from a source image and re-rendering). The metrics used are PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), SSIM (Structural Similarity Index), and LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity). The best and worst-performing methods are highlighted.

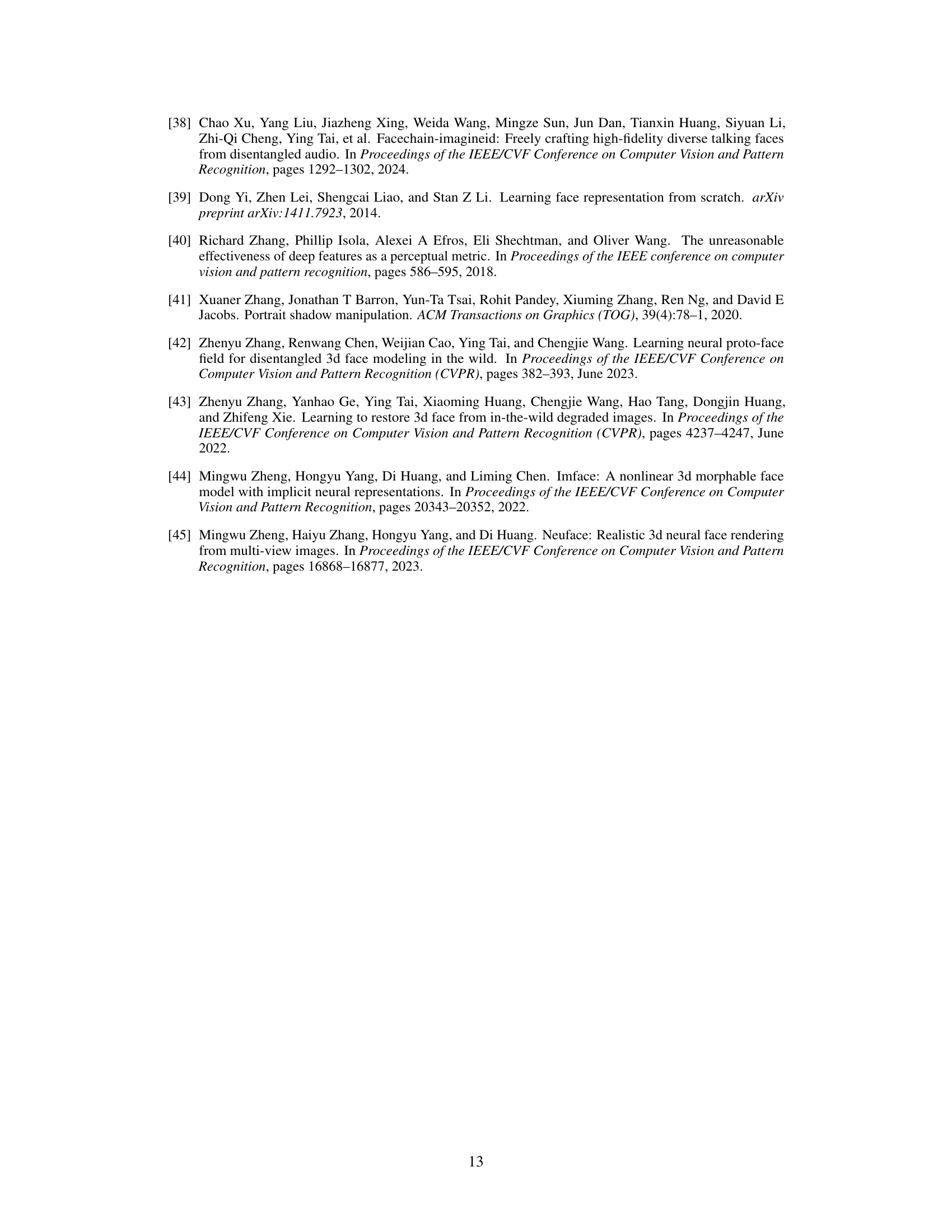

This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted to determine the optimal number of lighting conditions (n) used in the proposed face texture modeling framework. The study varied the number of initial light conditions (n = 3, 5, 7, and 9), and evaluated the performance using three metrics: Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS). The results show that using 5 initial lighting conditions produced the best performance, indicating that increasing the number beyond that point does not yield a significant improvement.

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed losses (GP, LP, and HP) on the performance of the model. It demonstrates the individual contribution of each loss to the overall performance, showing improvements in PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS metrics when more losses are included.

Full paper#