↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Visual perception involves complex interactions between low-level sensory processing and high-level cognitive functions. Existing models struggle to capture the flexible modulation of sensory processing based on context and goals, often failing to replicate human behavior. This limits our understanding of visual attention and its neurological basis.

This paper introduces a novel neural network model called DCnet, inspired by the visual cortex. DCnet incorporates local, lateral, and top-down connections and uses a low-rank mechanism to modulate sensory responses according to cues. The model significantly outperforms state-of-the-art deep learning models on visual search tasks and replicates key human psychophysics findings in attention experiments, including reaction times. This demonstrates its ability to capture both the biological realism and computational efficiency.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel biologically-inspired model, DCnet, that outperforms existing models on visual search tasks and replicates human psychophysics data. It offers a promising new framework for understanding visual processing and attention in the brain, opening new avenues for neuroscience research and artificial intelligence.

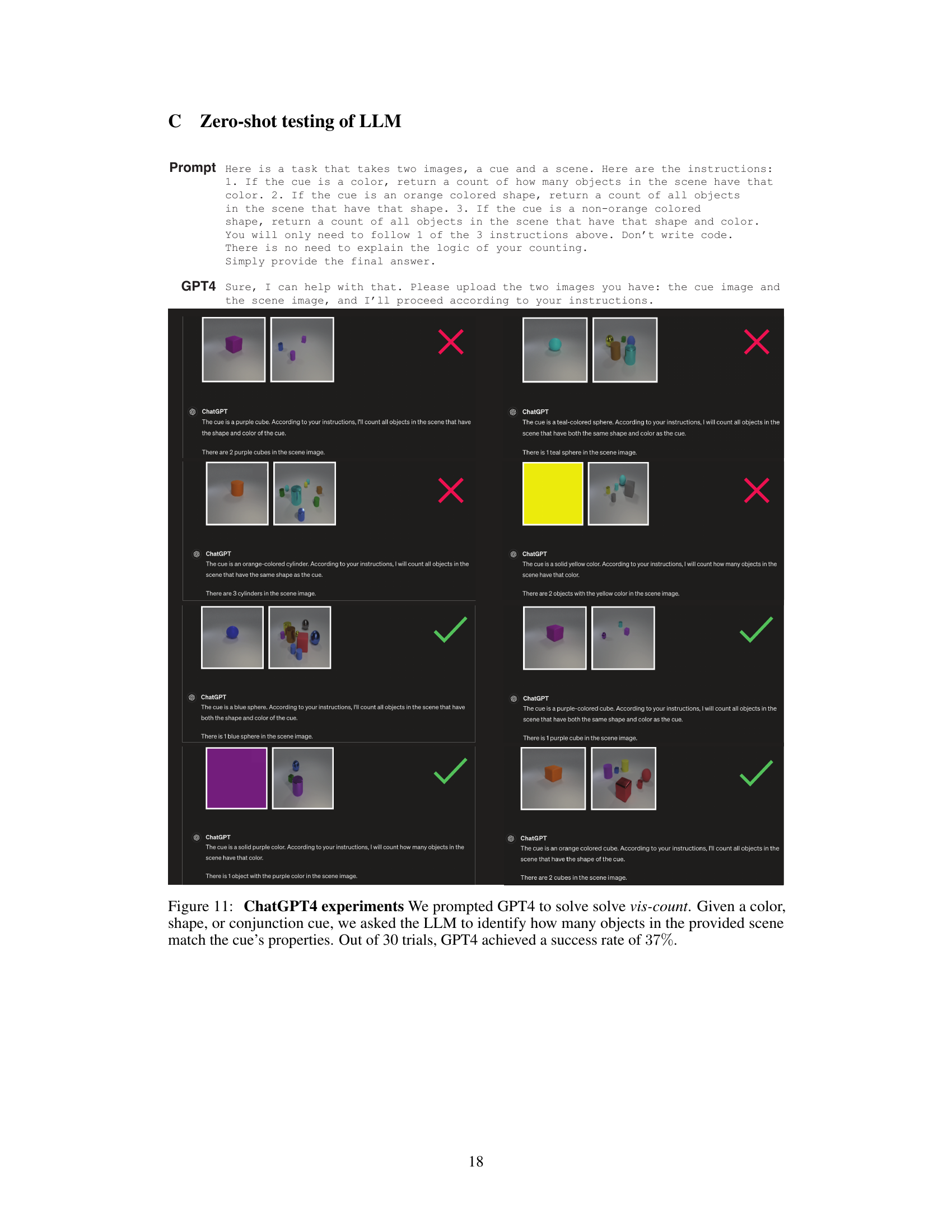

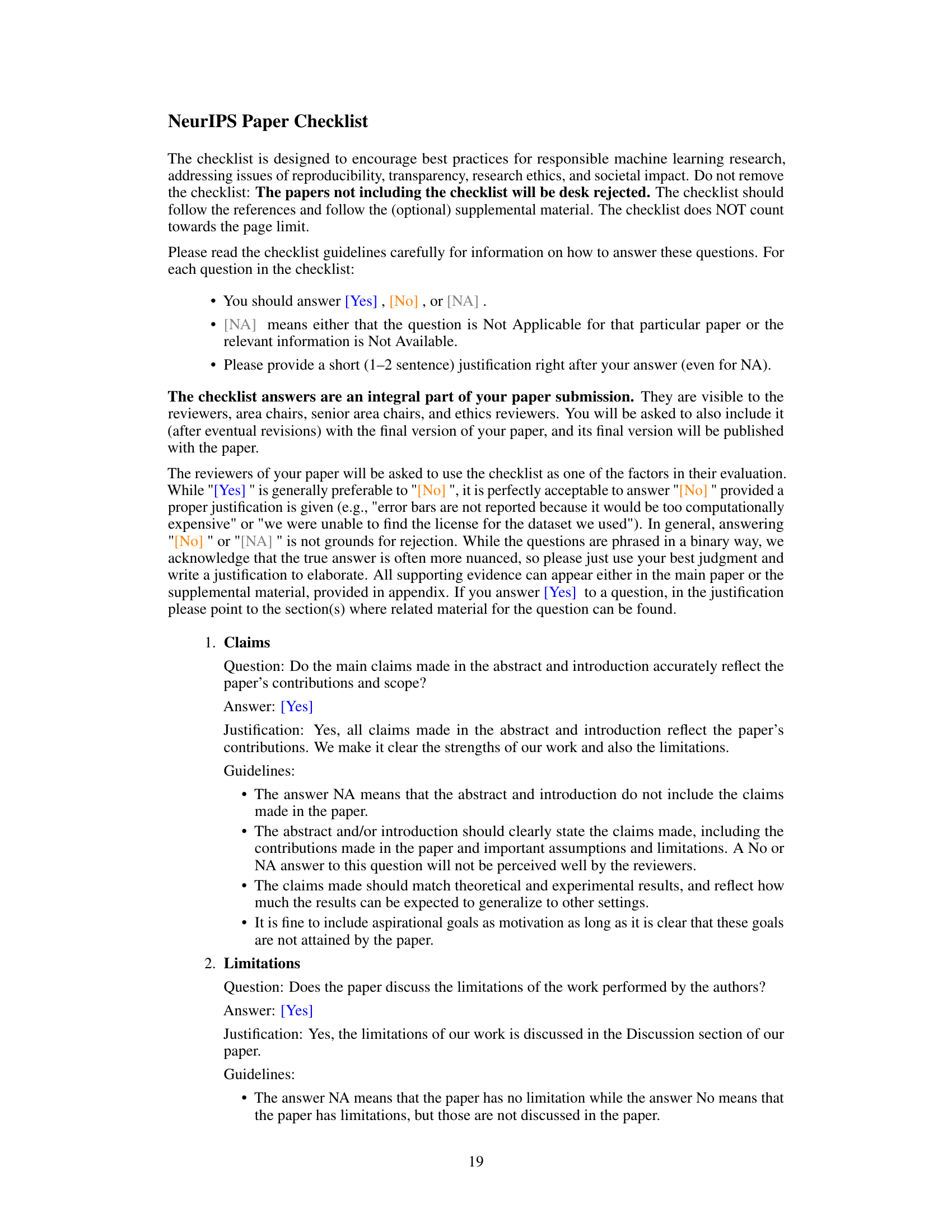

Visual Insights#

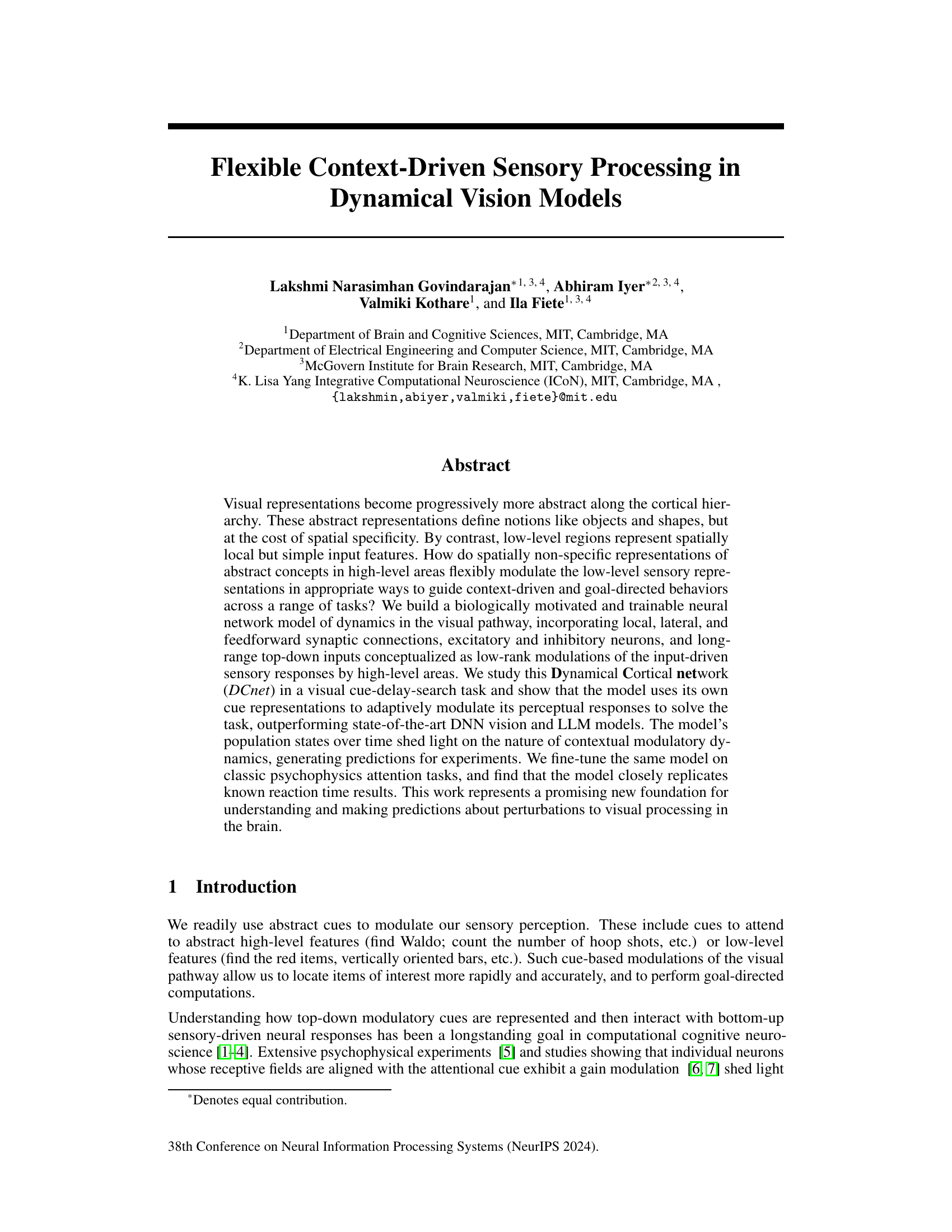

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Dynamical Cortical Network (DCnet) model. The model consists of multiple layers representing different stages of visual processing (V1, V2, etc.), each containing excitatory (E) and inhibitory (I) neural populations. These layers are interconnected via local, lateral, and feedforward connections. Critically, a higher-order layer sends low-rank modulatory signals back down to the sensory layers to guide context-driven processing. The low-rank modulations act as multiplicative factors, shaping the input-driven activity in the sensory areas based on higher-level context cues extracted from earlier parts of the trial.

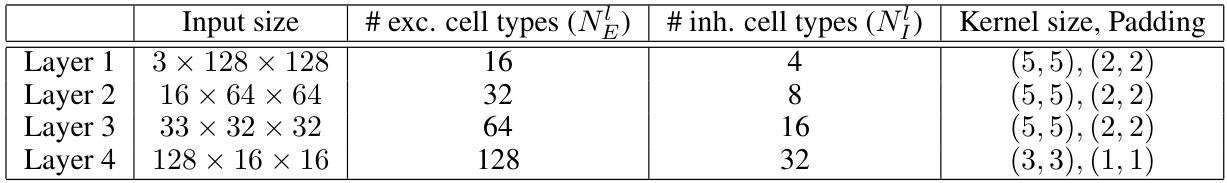

This table details the architecture of the Convolutional RNN baseline model used in the paper. It provides information on the input size, number of output channels, kernel size, padding, activation function (ReLU), and pooling layers for each convolutional layer. It also specifies the fully connected and GRU layers, along with their input and output dimensions.

In-depth insights#

Cued Visual Search#

Cued visual search is a fundamental task in visual cognition, probing how attentional mechanisms guide efficient target detection amidst distractors. Top-down cues dramatically influence search performance by biasing the visual system towards relevant features. This study uses a novel task, vis-count, that parametrically manipulates cue type (color, shape, conjunction), and scene complexity, allowing for nuanced analysis of contextual effects. The model, DCnet, showcases the importance of explicit context integration, using the cue to dynamically modulate bottom-up sensory responses, unlike implicit models that integrate cues and scenes simultaneously. This leads to superior generalization, replicating human performance, which showcases how the model learns to extract abstract cues and effectively use them in the search process. Ultimately, the findings highlight the critical role of biologically plausible recurrent dynamics and top-down modulation in efficient visual search, providing a more comprehensive understanding of visual processing and attention in the brain. The work also provides a framework for generating testable hypotheses about how various brain regions and neural circuits interact to solve visually guided tasks.

DCnet Architecture#

The Dynamical Cortical Network (DCnet) architecture is a biologically-inspired model designed for visual processing, incorporating several key features of the visual pathway. It’s structured as a layered network, mirroring the hierarchical organization of the visual cortex, with each layer composed of both excitatory and inhibitory neurons. This E/I balance is crucial for regulating network activity and achieving stable dynamics. Synaptic connections between layers are established through both local and long-range pathways, reflecting both feedforward and feedback processing. A particularly innovative feature is the inclusion of a higher-order layer that interacts with the lower sensory layers through low-rank modulations. This represents a mechanism for top-down attentional control, where higher-level contextual information can selectively modulate lower-level activity. Furthermore, the model integrates recurrent connections within layers, making it a dynamic system that processes information over time. This time-dependent processing allows for modelling the temporal unfolding of visual computations and reaction times observed in psychophysics experiments. The model’s design facilitates end-to-end training, allowing for the network’s parameters, including synaptic weights and time constants, to be learned directly from the data. The overall architecture strikes a balance between biological realism and computational tractability, making it a promising tool for understanding visual processing in the brain.

Model Dynamics#

The heading ‘Model Dynamics’ suggests an exploration of the temporal evolution of the model’s internal representations and computations. A deep dive would likely reveal how the model processes information over time, showcasing the interplay between bottom-up sensory inputs and top-down contextual cues. Crucially, an analysis of model dynamics would likely illuminate the mechanisms underlying context-dependent behavior, such as how the model flexibly adapts its responses based on the provided visual cues. Investigating model dynamics could involve analyzing the temporal patterns of neural activity within the model, identifying key transitional states or activity regimes, and characterizing the stability and robustness of these dynamics. This analysis is essential for establishing the model’s reliability and generalizability. Specific attention should be paid to how the model handles delayed visual search tasks, clarifying how information is maintained and integrated across different temporal phases. The analysis of model dynamics would, therefore, serve as a crucial step in understanding the model’s computational capabilities and its neurobiological plausibility. Moreover, the exploration of model dynamics could reveal underlying principles of human visual processing, potentially revealing insights into how contextual cues influence perception, attention, and decision-making.

Psychophysics Tasks#

The section on psychophysics tasks is crucial for validating the model’s biological plausibility and demonstrating its capacity to predict human behavior. It directly tests the model’s ability to handle visual search tasks that are well-established in the psychophysics literature. By replicating reaction time and accuracy results from these classic experiments, the model’s predictive power is significantly strengthened. The choice of parametric tasks allows for a systematic investigation of how various factors such as distractor heterogeneity and target-distractor similarity influence performance. This parametric approach provides a more nuanced understanding than simple accuracy metrics, revealing the model’s dynamic response to subtle changes in visual input. Successful replication of these psychophysical findings suggests that the model captures fundamental aspects of the underlying neural computations, providing a powerful link between theoretical models and experimental observations. The results showcase the model’s ability to go beyond simple image classification and tackle complex temporal aspects of visual processing in a biologically plausible manner.

Future Directions#

Future research should explore extending the DCnet model to encompass more complex visual tasks, such as object recognition in cluttered scenes or visual question answering. Investigating the model’s performance with noisy or incomplete sensory data would also be valuable, mirroring real-world conditions. A key area for future work is exploring different attention mechanisms, comparing the current low-rank modulation approach with other biologically plausible alternatives. Furthermore, delving deeper into the model’s internal dynamics through more detailed in silico electrophysiological analyses is crucial for validating its biological plausibility and generating more specific, testable hypotheses. Finally, investigating the model’s generalizability to other sensory modalities beyond vision would provide a broader understanding of its potential applications. The inherent interpretability of DCnet provides a unique opportunity to bridge the gap between computational neuroscience and machine learning, making it a compelling platform for future research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

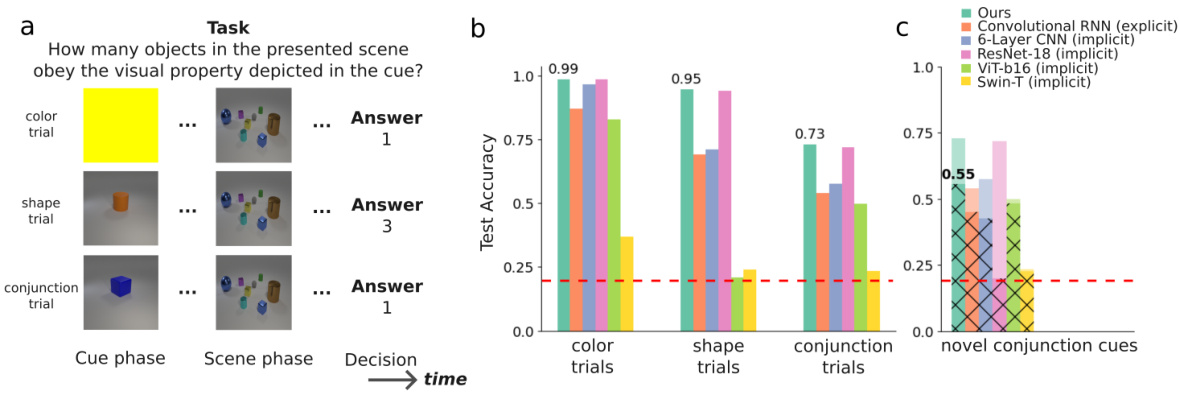

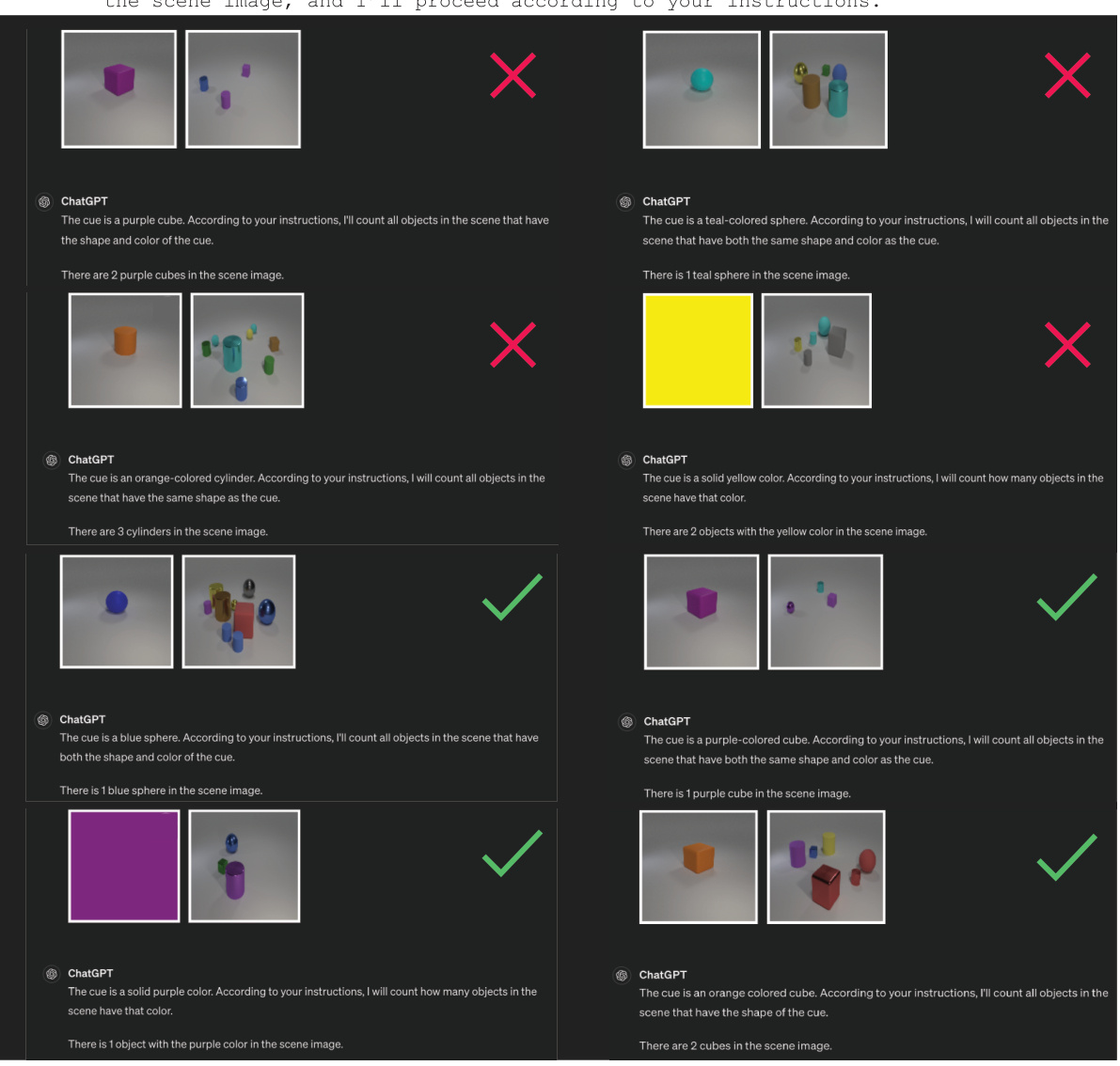

This figure demonstrates the performance of the Dynamical Cortical Network (DCnet) model on the vis-count task compared to several baseline models. The vis-count task involves a cue-delay-search paradigm where the model first receives a cue (color, shape, or conjunction) and then a scene, and it must count the number of objects in the scene matching the cue. Panel (a) illustrates the task. Panel (b) shows the model’s superior performance on various types of trials compared to different Deep Neural Networks (DNNs). Panel (c) demonstrates the model’s strong generalization ability to novel scenes and cues, exceeding the performance of implicit models.

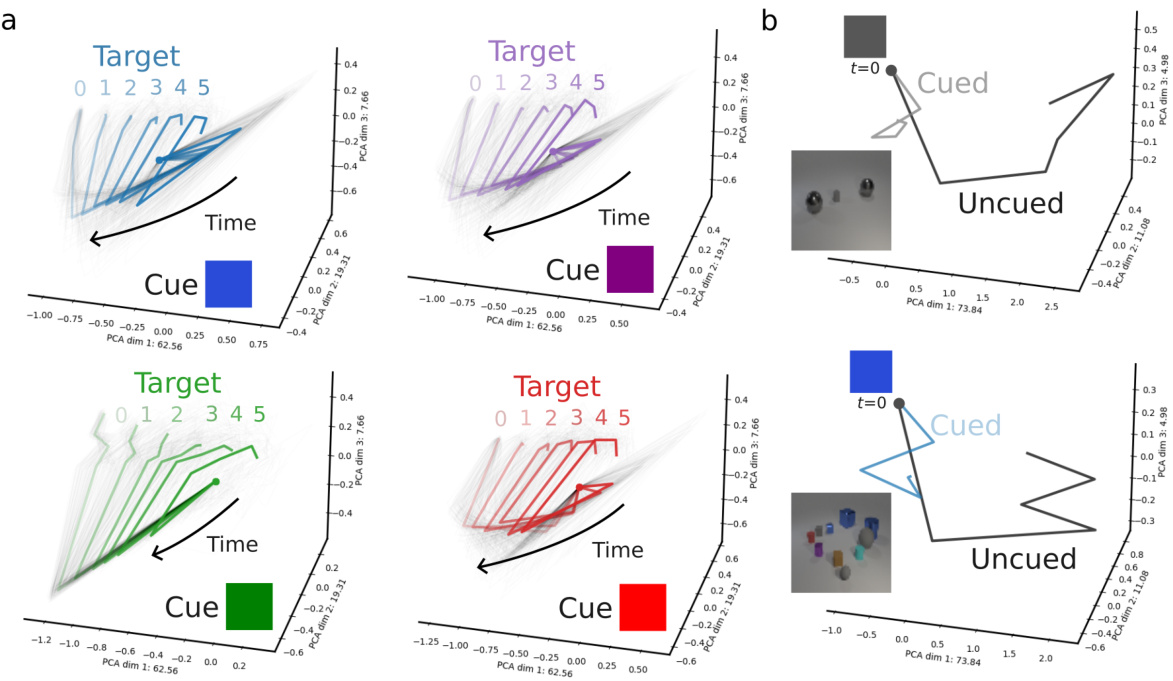

This figure visualizes the neural network dynamics of the DCnet model in a cue-delay-visual search task. Panel (a) shows how the model’s activity, for a fixed cue, tracks the relevant information (number of objects meeting the cue criteria) while ignoring irrelevant details in the scene. Panel (b) compares the model’s response to cued and uncued trials with the same scene, illustrating how the top-down cue modulates the bottom-up responses, leading to distinct neural trajectories.

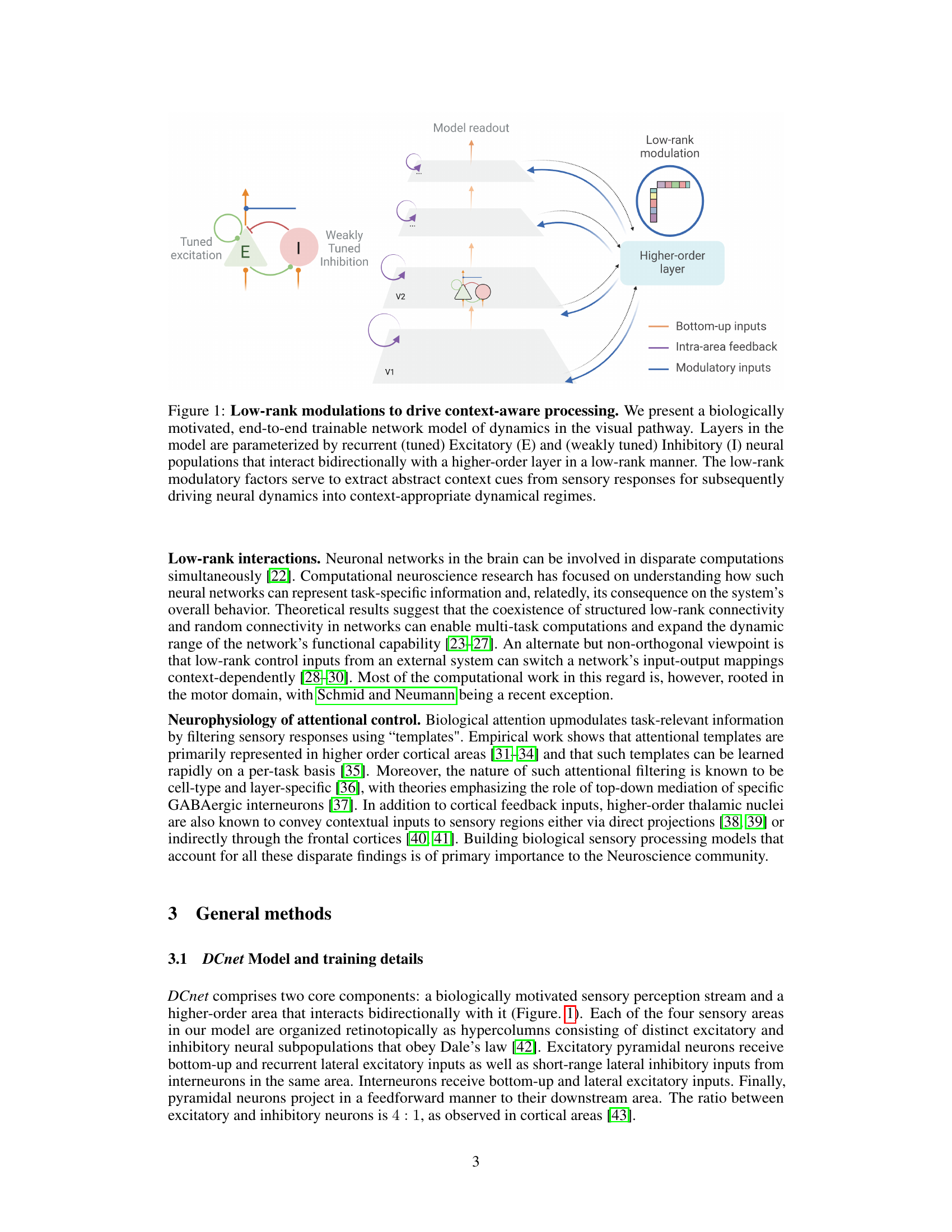

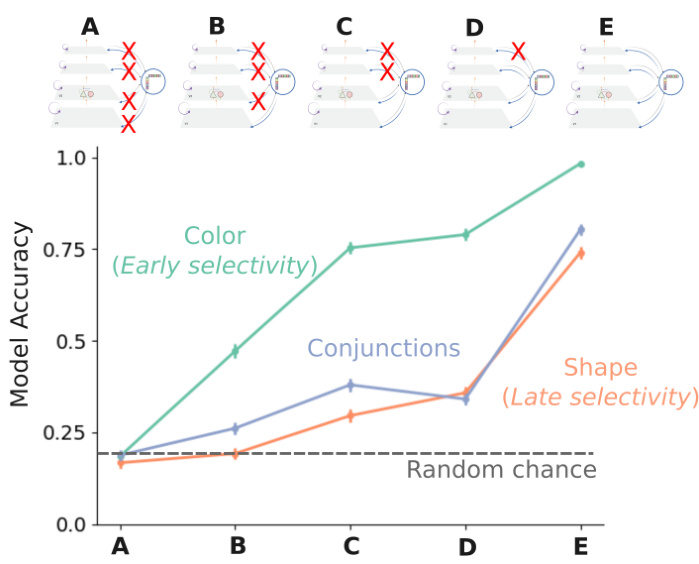

This figure shows a selectivity gradient across cortical layers for different visual cues (color, conjunctions, shape). By sequentially lesioning modulatory synapses from higher-order layers to sensory areas, the authors demonstrate that early areas exhibit color selectivity, while later areas show shape selectivity. This suggests a hierarchical processing of visual information where early layers process basic features and later layers integrate more complex information.

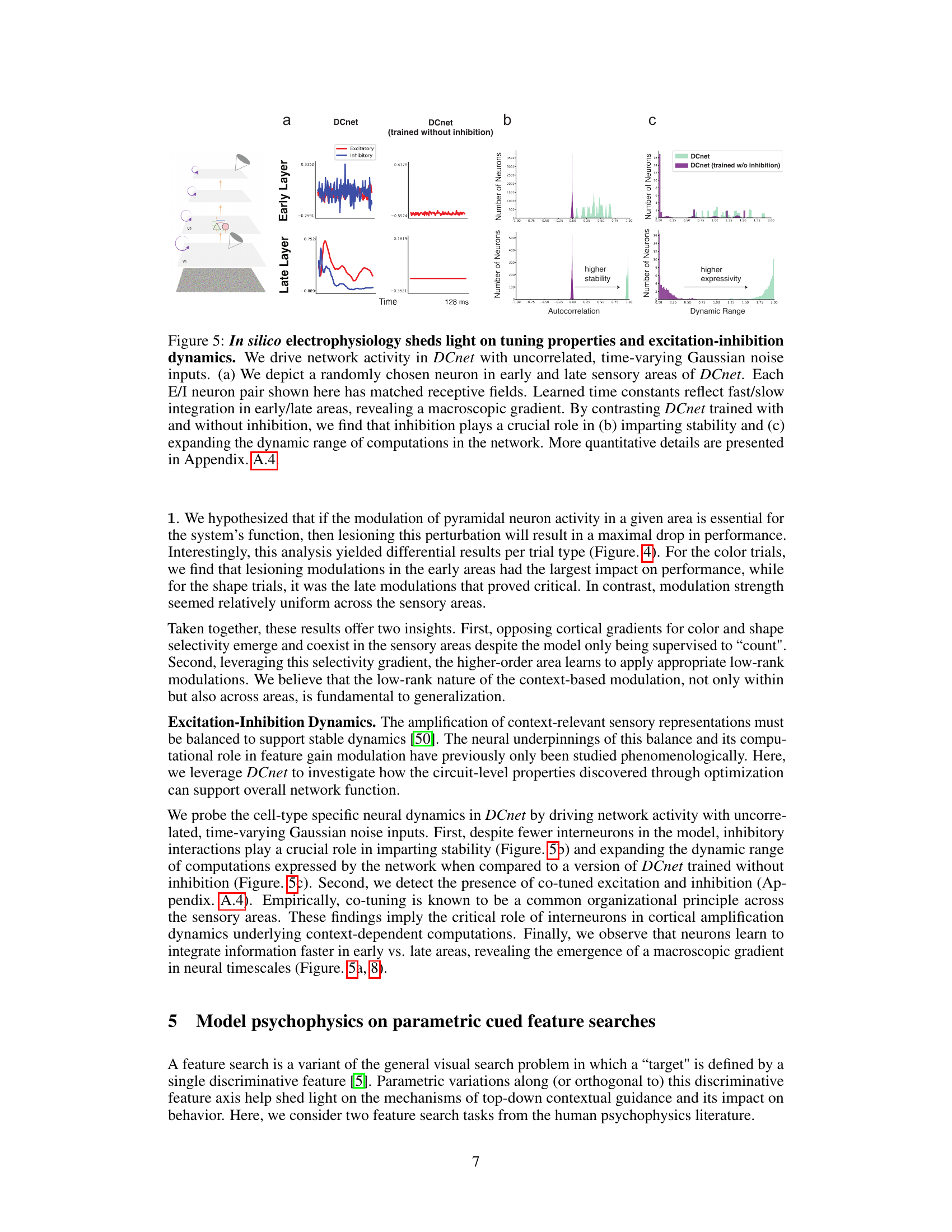

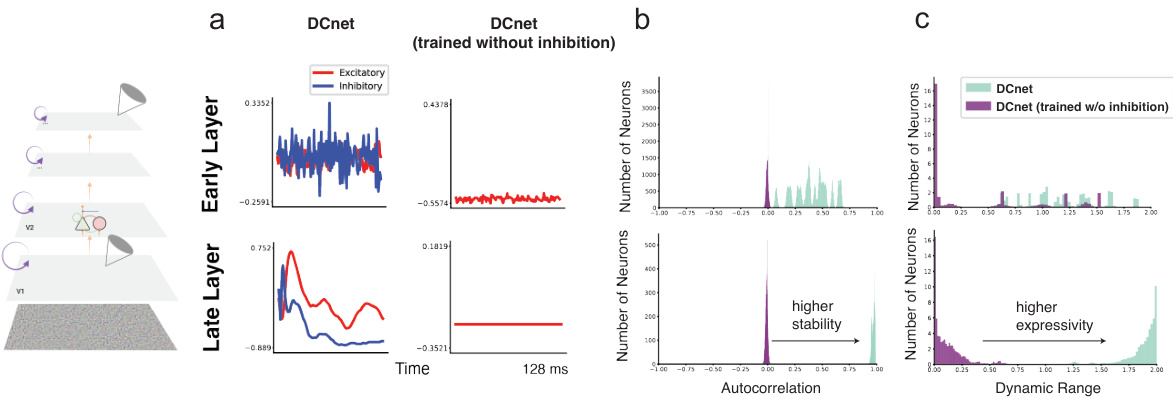

This figure demonstrates the results of in silico electrophysiology experiments on the DCnet model. Panel (a) shows the activity of a single excitatory/inhibitory neuron pair in early and late sensory areas, highlighting the different time constants learned by the network. Panels (b) and (c) compare the autocorrelation and dynamic range of the network’s activity when trained with and without inhibition, showing that inhibition is crucial for stability and increased computational expressiveness.

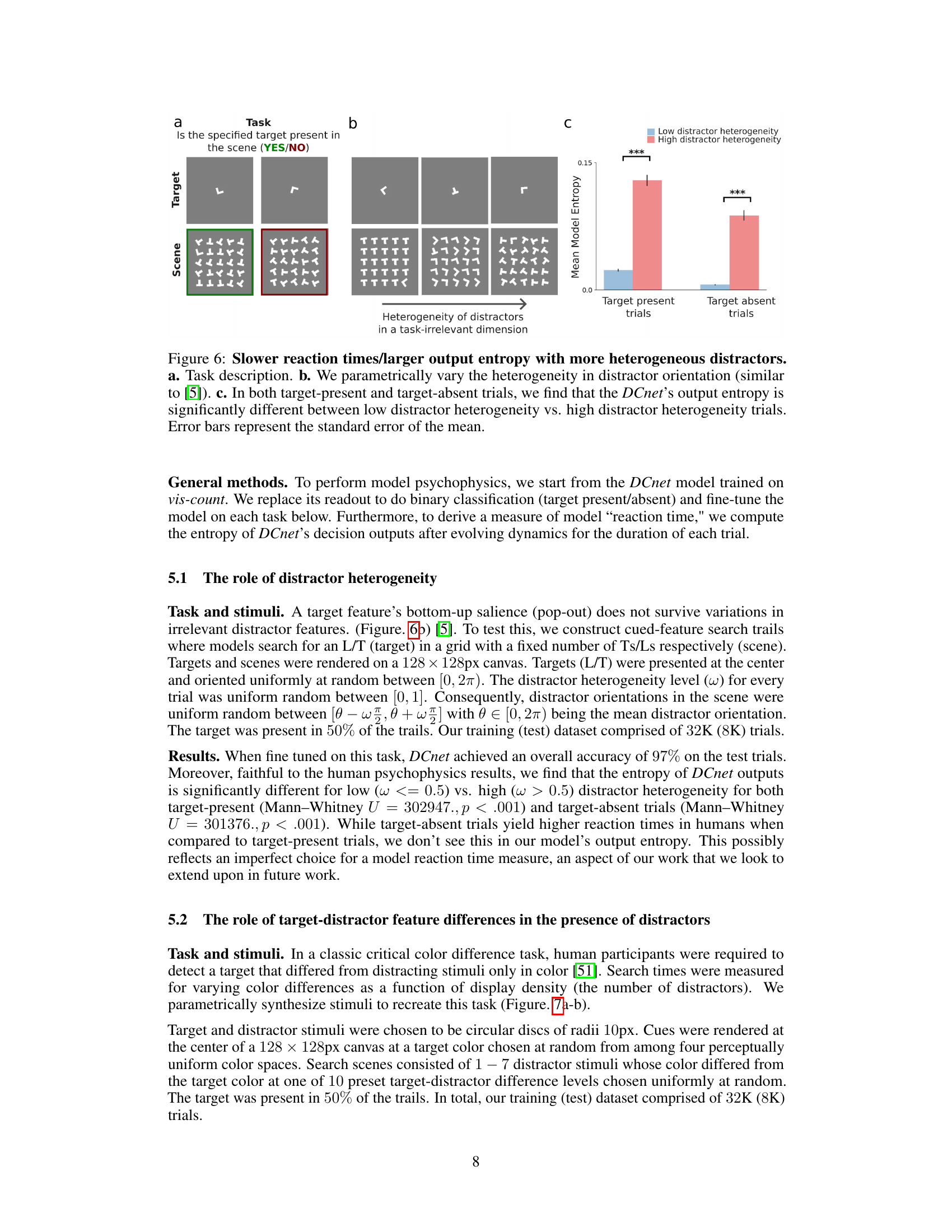

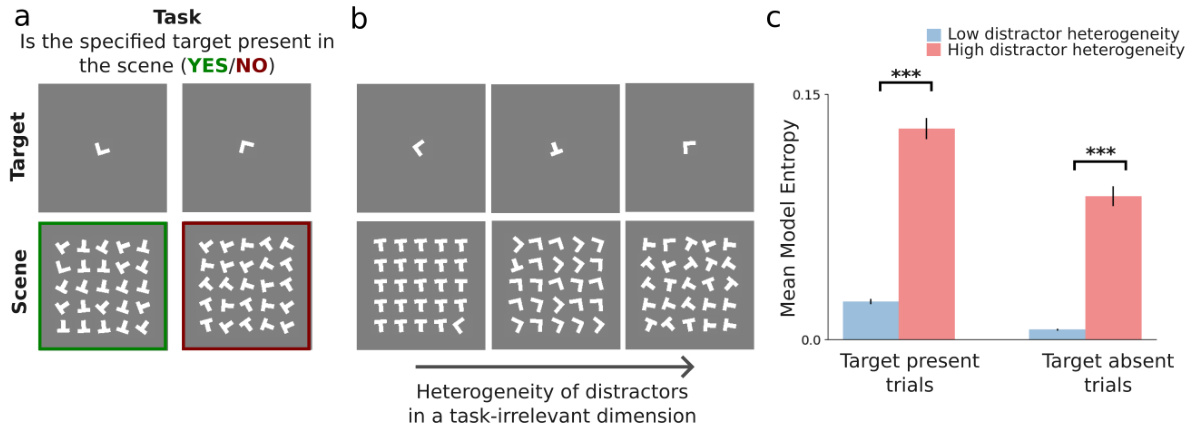

This figure demonstrates the impact of distractor heterogeneity on the model’s performance in a visual search task. Panel (a) describes the task: determining if a target shape (L or T) is present in a scene filled with distractors (also L or T shapes). Panel (b) shows how the experiment manipulates distractor heterogeneity: the orientation variability of distractor shapes increases from left to right. Panel (c) presents the key results, showing that higher distractor heterogeneity leads to significantly higher model entropy (a proxy for reaction time) in both target-present and target-absent trials. This aligns with human performance in similar tasks, showing that increased distractor similarity slows reaction times.

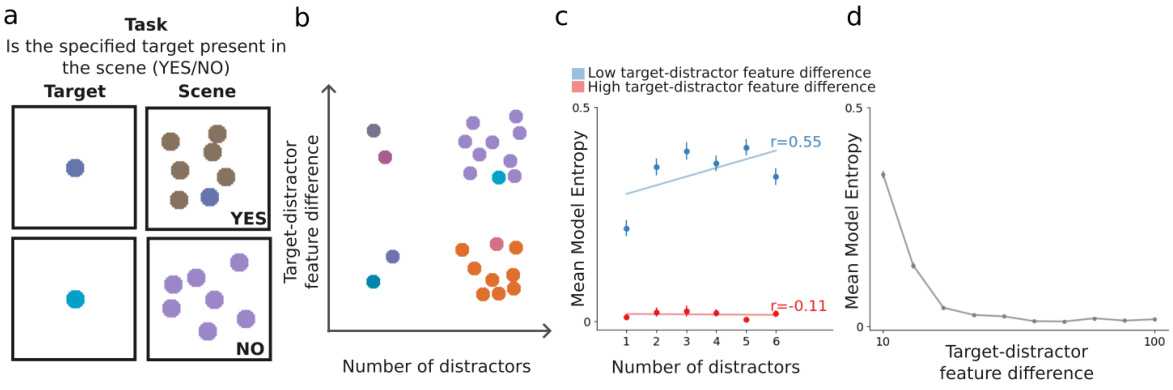

This figure shows the results of a psychophysics experiment using the DCnet model. It demonstrates the model’s ability to replicate human behavior in a feature search task, showing how reaction time (represented by entropy) changes based on the number of distractors and the difference in features between the target and distractors. Panel (c) and (d) specifically illustrate the ‘pop-out’ effect, where a large difference in features between target and distractors makes reaction time independent of the number of distractors.

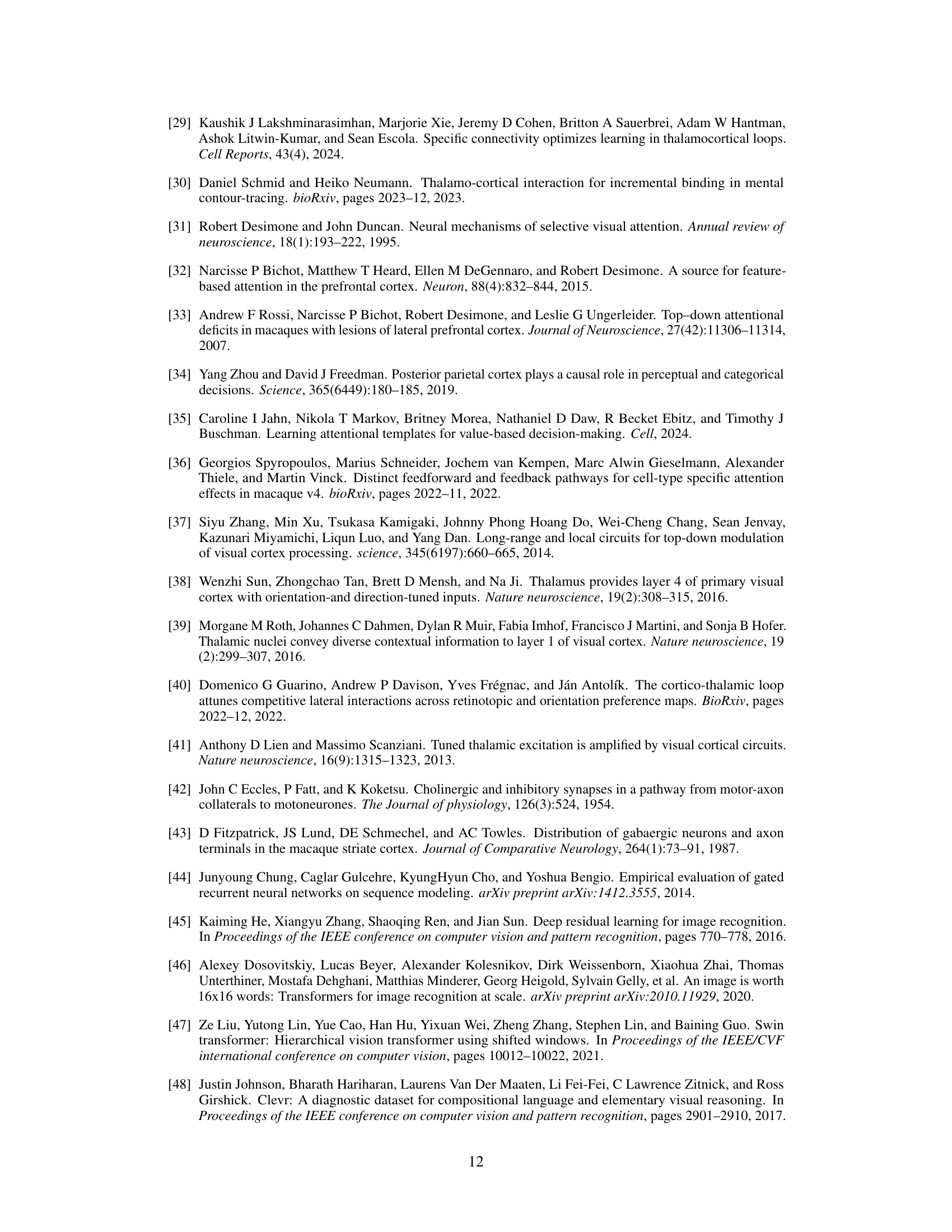

This figure shows the distribution of excitatory (a) and inhibitory (b) neuron time constants at the start and end of training across four cortical layers. The initial distribution is uniform, but after training, a gradient emerges. The time constants (integration times) become progressively shorter in higher layers, suggesting that the network learns a hierarchical processing structure where information is integrated at different time scales in different cortical areas.

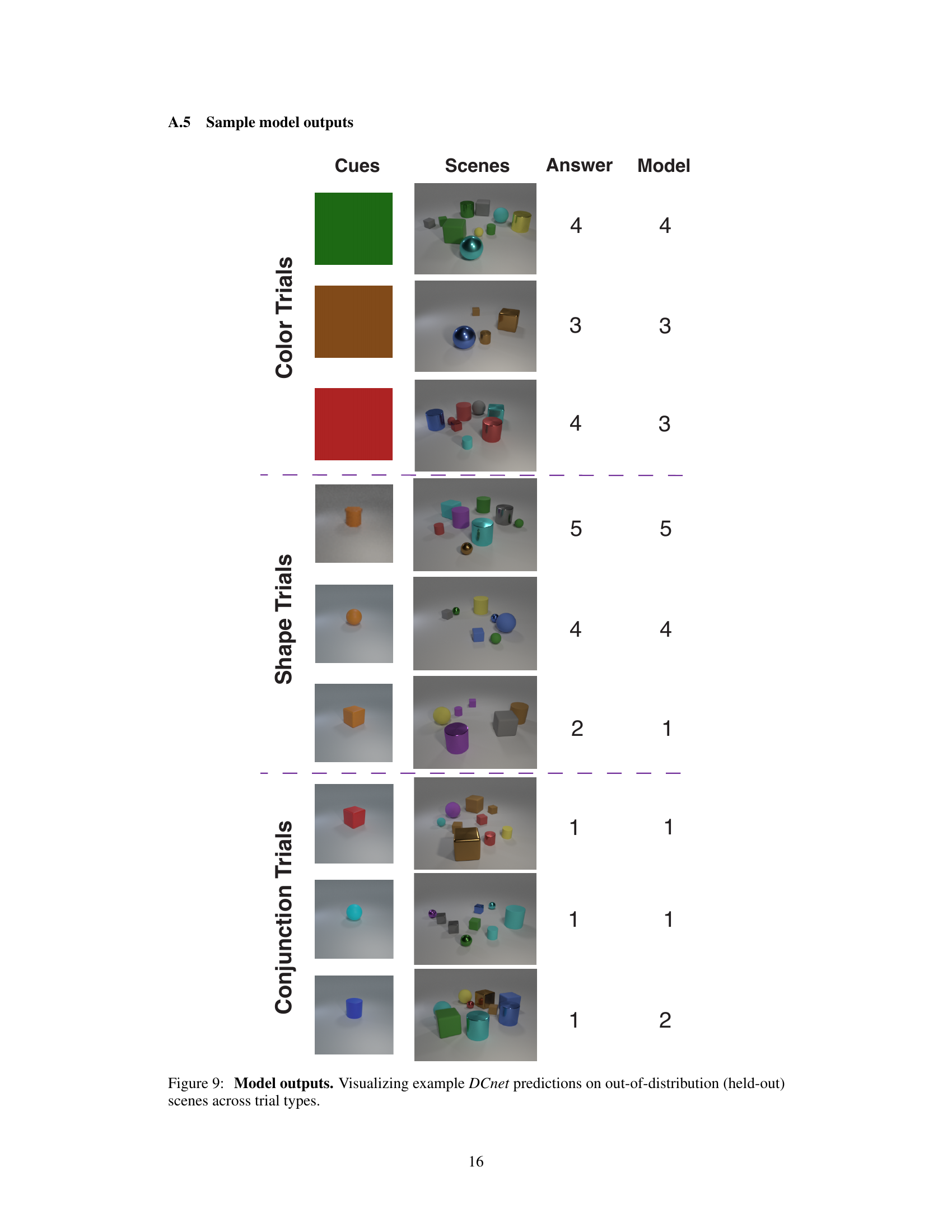

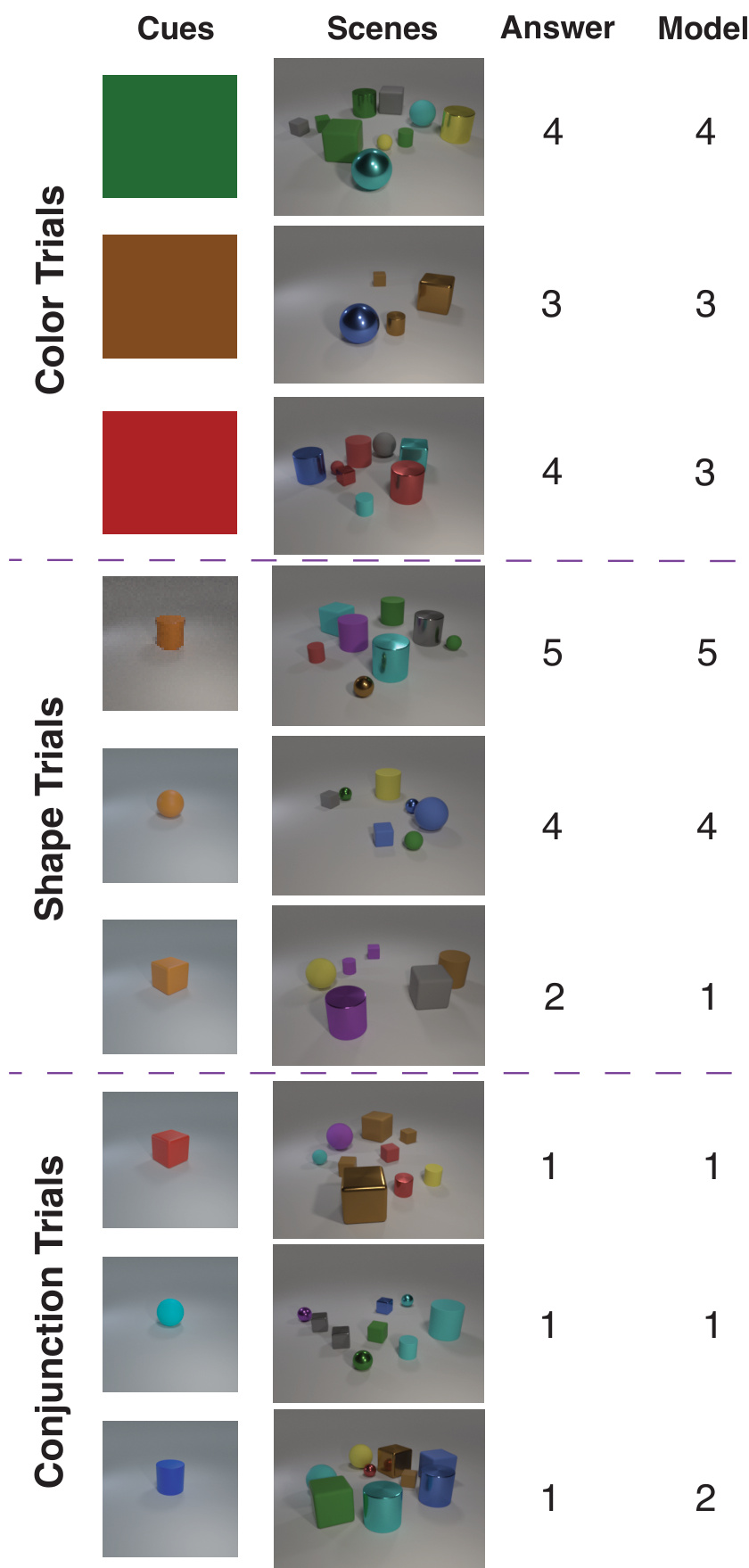

This figure shows example outputs from the DCnet model on held-out test sets (out-of-distribution). The table shows examples for color, shape, and conjunction trials. For each trial type, the cue (a color, shape, or combination), the scene image, the correct answer (count of objects matching the cue), and the model’s prediction are presented. This visualization helps illustrate the model’s generalization performance on unseen data.

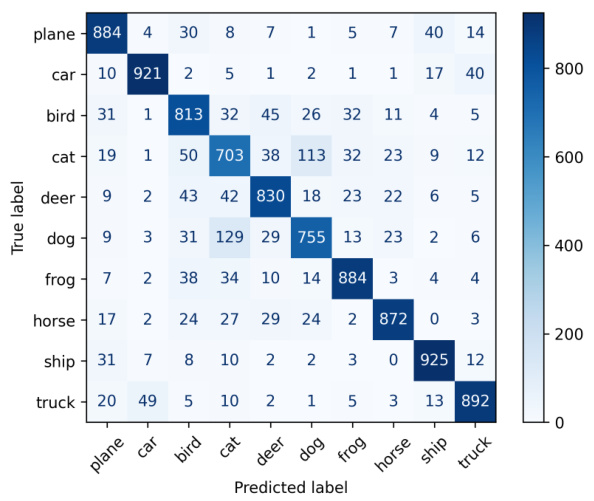

This figure shows a confusion matrix visualizing the performance of the DCnet model on the CIFAR-10 object recognition benchmark. The matrix displays the counts of correctly and incorrectly classified images for each of the ten classes (plane, car, bird, cat, deer, dog, frog, horse, ship, truck). The diagonal elements represent the number of correctly classified images for each class, while off-diagonal elements show misclassifications between classes. The overall accuracy of the model on this dataset is reported as 84.79%. This demonstrates that the model architecture developed for context-aware visual search can be adapted for other image classification tasks.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Dynamical Cortical network (DCnet) model. The model is a biologically-inspired, trainable neural network designed to simulate the visual pathway. It consists of multiple layers, each containing excitatory (E) and inhibitory (I) neural populations. Crucially, a higher-order layer uses low-rank modulations to send top-down signals that flexibly adjust the processing in lower layers. This allows the model to incorporate context and abstract cues to guide its processing, making it context-aware.

Full paper#