↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Offline model-based optimization (MBO) is essential when querying the true objective function is expensive. However, inaccurate surrogate models often lead to poor optimization results. This is particularly problematic in areas such as drug design or materials science where each function evaluation is very expensive. Existing methods for offline MBO struggle with inaccurate surrogate models, leading to suboptimal designs.

This paper introduces a novel framework, Generative Adversarial Model-based Optimization using adaptive source critic regularization (aSCR), to address these issues. aSCR dynamically adjusts the strength of a constraint that keeps the optimization within the reliable region of the design space. The method is shown to outperform existing approaches on a variety of offline generative design tasks, demonstrating its effectiveness and broad applicability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in model-based optimization, particularly those working with offline settings. It introduces a novel regularization technique, aSCR, significantly improving the accuracy and reliability of offline optimization. The results demonstrate improved performance across diverse scientific domains, highlighting the broad applicability of the method. This work opens avenues for further exploration and refinements of offline MBO strategies, impacting multiple scientific domains needing efficient optimization under constrained data availability.

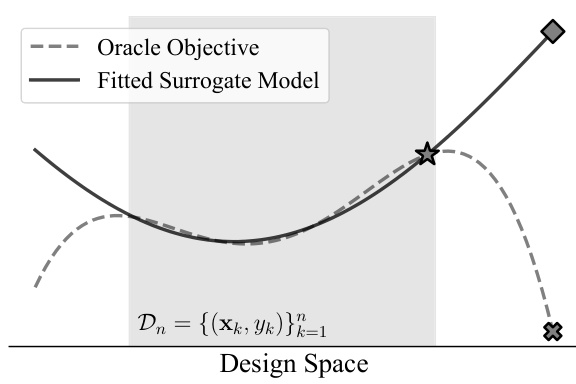

Visual Insights#

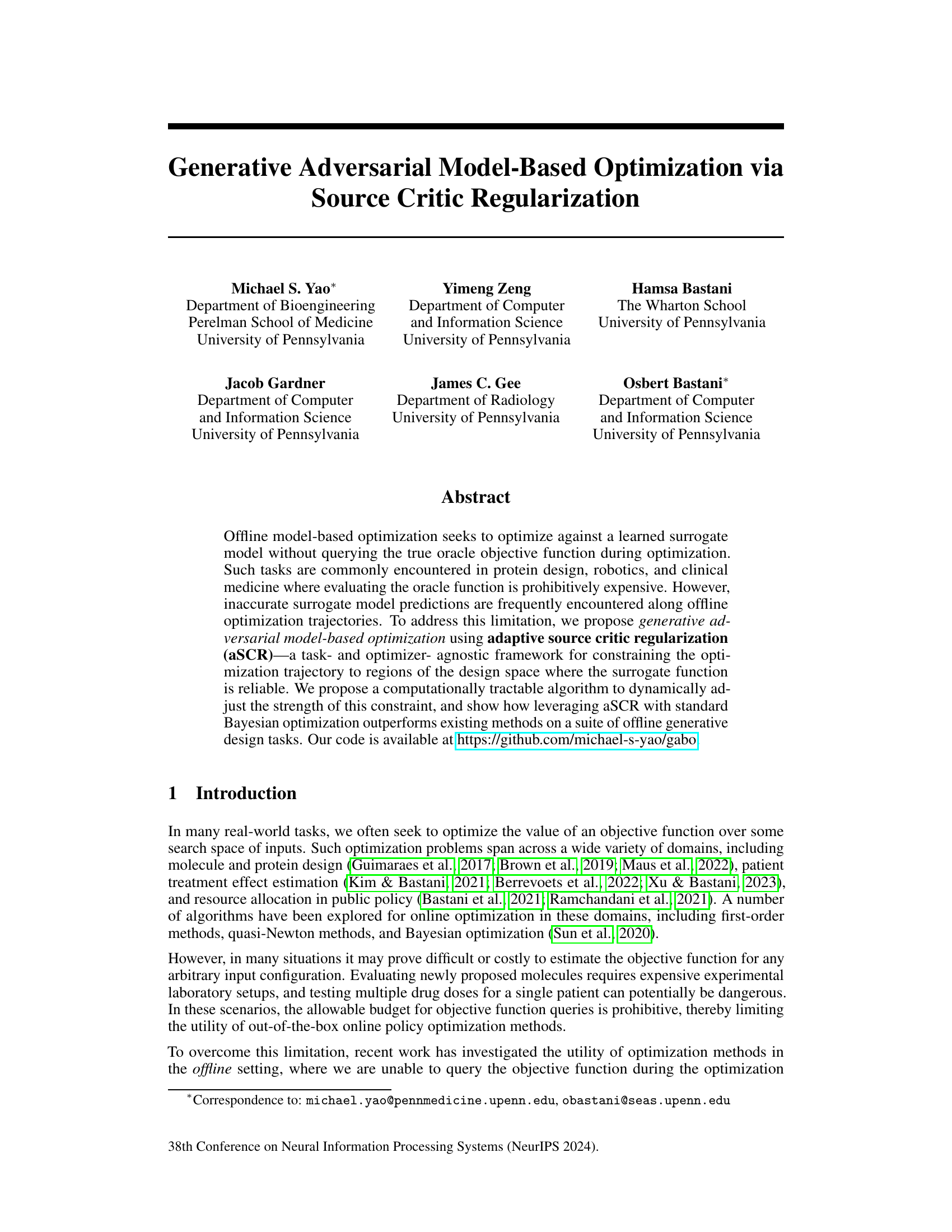

The figure illustrates the problem of naive offline model-based optimization (MBO). A surrogate model is trained on a limited dataset and used to find optimal designs. However, because the surrogate model is only trained on the limited data, it can extrapolate poorly into areas where it is not accurate, leading to poor designs when measured against the true objective function. The authors’ proposed method (aSCR) addresses this by constraining the optimization trajectory to regions where the surrogate model is reliable, thus improving the overall design.

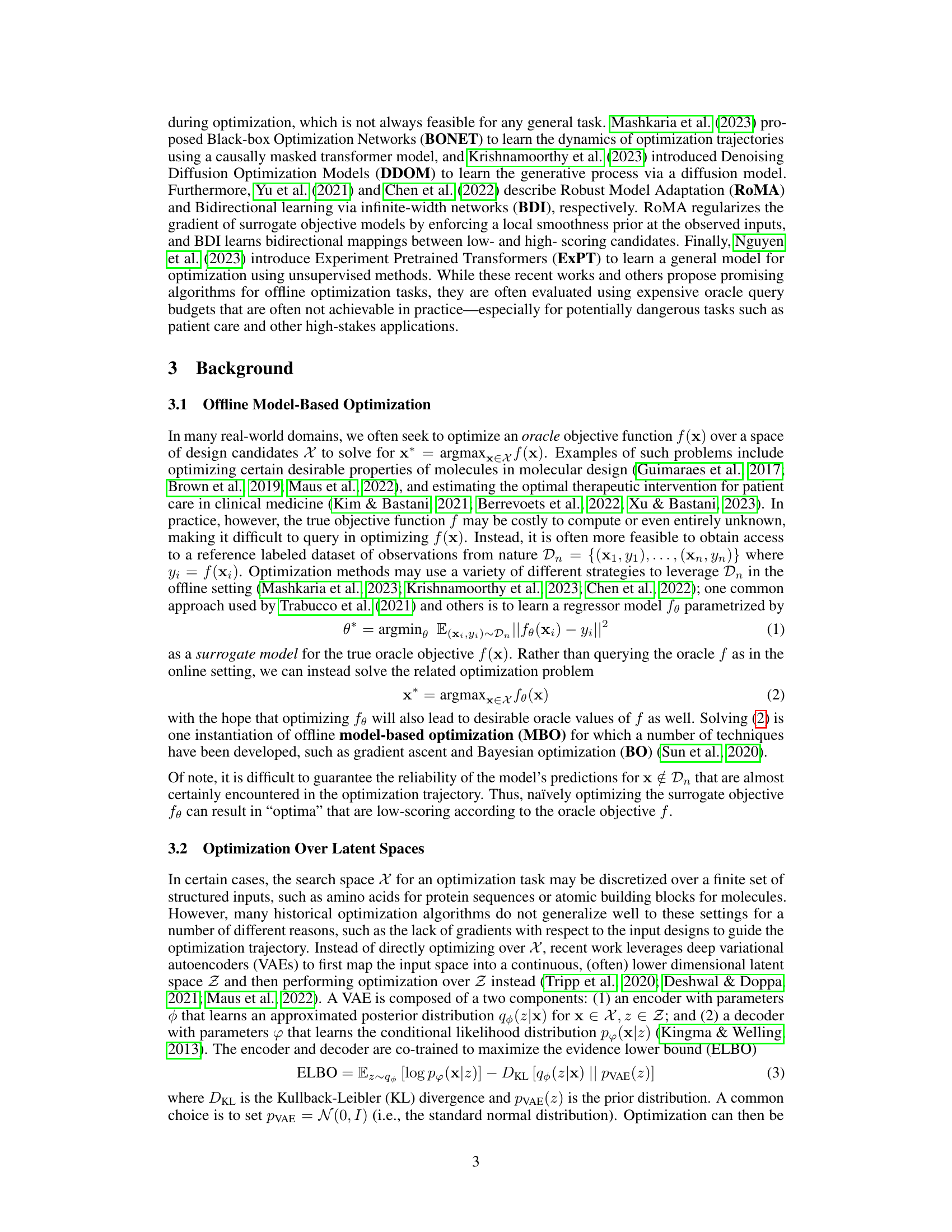

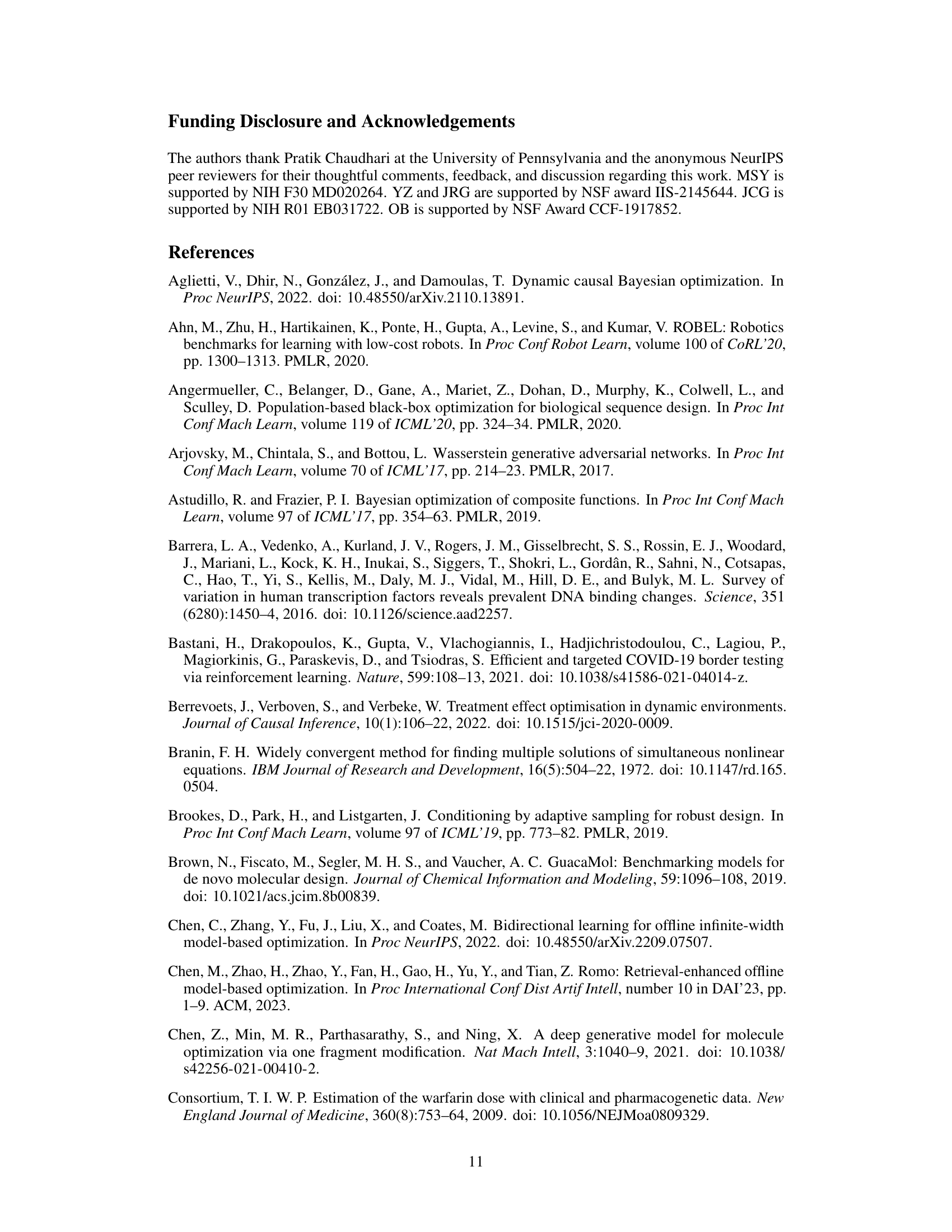

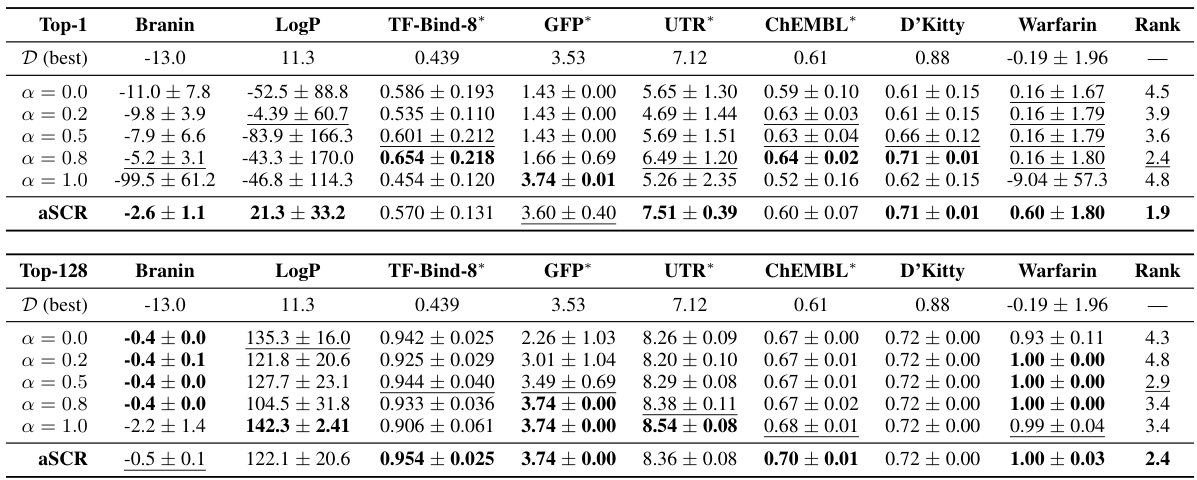

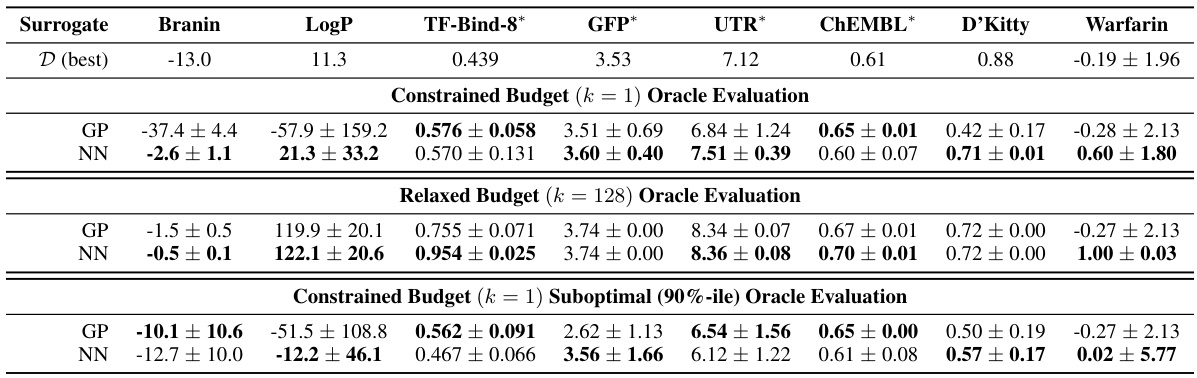

This table presents the results of a single-design evaluation (k=1) using eight different offline model-based optimization (MBO) methods across eight diverse tasks. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the oracle function scores for each method and task, and ranks the methods by average rank across all tasks. The ‘D (best)’ column shows the best oracle score observed in the dataset for each task. A lower average rank indicates better performance.

In-depth insights#

Offline MBO#

Offline model-based optimization (MBO) tackles the challenge of optimizing an objective function without directly querying it during the optimization process. This is particularly relevant when evaluating the objective function is expensive or impossible, as in many real-world scenarios such as drug discovery or materials science. The core idea is to learn a surrogate model from a set of pre-collected data points, which approximates the true objective function. The optimization then proceeds by iteratively improving the surrogate model and selecting promising candidate solutions. A key challenge is the inherent inaccuracy of surrogate models, which can lead to suboptimal solutions if not carefully addressed. This necessitates techniques for ensuring reliability, such as incorporating uncertainty estimations or employing regularization methods to constrain optimization trajectories to regions where the surrogate model is trustworthy. Methods often involve generative models or Bayesian approaches, which allows exploration of the search space and efficient adaptation to new data. The development of robust offline MBO methods is crucial for making progress in many fields where direct evaluation is prohibitively expensive. The ultimate goal is to find a balance between optimizing the surrogate model and avoiding overfitting, leading to truly effective optimization in the offline setting.

aSCR Regularization#

The core idea behind aSCR regularization is to address the problem of inaccurate surrogate model predictions during offline model-based optimization. Instead of blindly optimizing a learned surrogate model, aSCR dynamically constrains the optimization trajectory to regions of the design space where the surrogate is reliable. This is achieved by introducing a source critic, a component trained to distinguish between data points from the true objective function and those predicted by the surrogate. The source critic acts as a regularizer, penalizing exploration of regions where the surrogate model is deemed unreliable. This adaptive approach (denoted by ‘a’) dynamically adjusts the penalty’s strength, balancing the need to optimize the surrogate with the need to remain within the reliable region of the surrogate, leading to improved robustness and performance in offline optimization.

GAMBO Algorithm#

The Generative Adversarial Model-Based Optimization (GAMBO) algorithm is a novel approach to offline model-based optimization. It addresses the challenge of inaccurate surrogate model predictions, a common issue in offline settings where evaluating the true objective function is expensive. GAMBO cleverly integrates adaptive source critic regularization (aSCR). This technique dynamically adjusts the strength of a constraint that keeps the optimization trajectory within the reliable region of the surrogate model. This is accomplished by dynamically adapting a Lagrange multiplier, preventing overestimation errors and leading to more robust optimization. The algorithm is optimizer-agnostic, meaning it can be used with various methods like Bayesian Optimization (BO) or gradient ascent. Experimental results demonstrate that GAMBO with Bayesian Optimization (GABO) outperforms existing methods across multiple domains, achieving a higher rank in design evaluation. The aSCR component is crucial to GAMBO’s success, showcasing its ability to improve the reliability of surrogate models and ultimately find higher-scoring solutions in offline scenarios. However, the method’s performance depends on the choice of the acquisition function and the quality of the surrogate model. Further investigation into the algorithm’s robustness and sensitivity to hyperparameter choices is needed.

Empirical Results#

The Empirical Results section of a research paper is crucial for demonstrating the validity and practical implications of the proposed methods. A strong presentation would begin by clearly stating the metrics used for evaluation, ensuring they align with the research goals. A comprehensive comparison against relevant baselines is vital, showcasing not just superior performance but also quantifiable improvements. The discussion should extend beyond raw numbers, exploring the reasons behind any observed trends. Statistical significance testing is essential to rule out random chance, providing confidence in the reported findings. Detailed analysis of both successful and unsuccessful cases can enhance understanding and highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the methodology. Visualizations like graphs and charts are highly beneficial for effectively communicating results, particularly when dealing with multiple variables or complex datasets. Finally, a thoughtful interpretation of the results should connect them back to the paper’s central hypothesis and broader implications, acknowledging limitations while offering perspectives on future research directions.

Future Work#

The paper’s omission of a dedicated ‘Future Work’ section presents a missed opportunity for insightful discussion. Given the significant advancements in offline model-based optimization (MBO) demonstrated with the proposed aSCR framework, several promising avenues merit exploration. Extending aSCR to more sophisticated optimization algorithms beyond Bayesian Optimization and gradient ascent would enhance its versatility and applicability. Addressing the computational cost associated with aSCR, particularly in high-dimensional spaces, is crucial for practical scalability. Further research should investigate the sensitivity and robustness of aSCR to various hyperparameter settings and explore methodologies for automated hyperparameter tuning, reducing reliance on manual adjustments. A deeper examination of the interaction between aSCR and the choice of surrogate model, exploring the impact of different surrogate model architectures on aSCR’s performance would provide valuable insights. Finally, evaluating aSCR on a wider array of offline optimization tasks across diverse domains will strengthen its generalization capabilities. Addressing these research directions could significantly enhance the impact and broaden the reach of this promising MBO methodology.

More visual insights#

More on figures

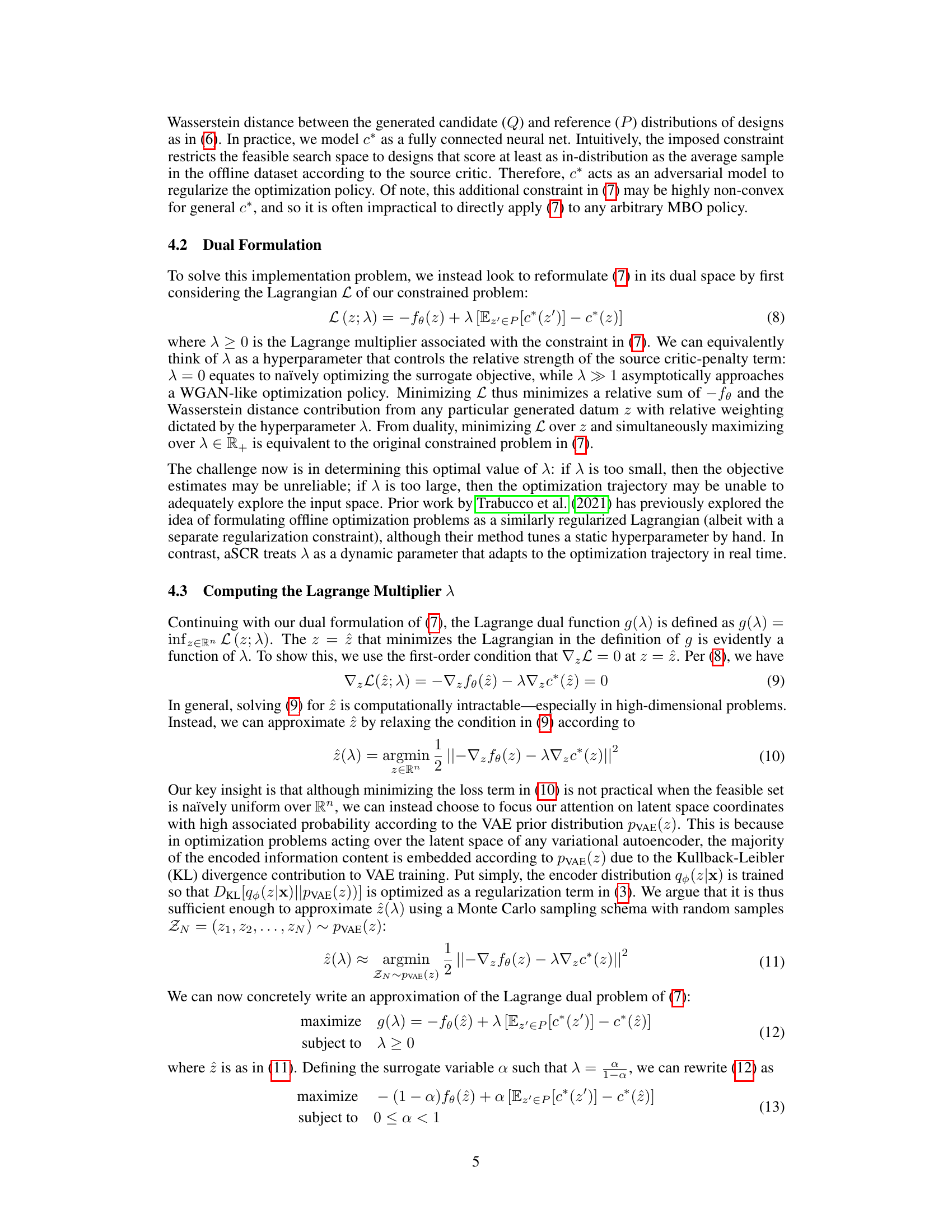

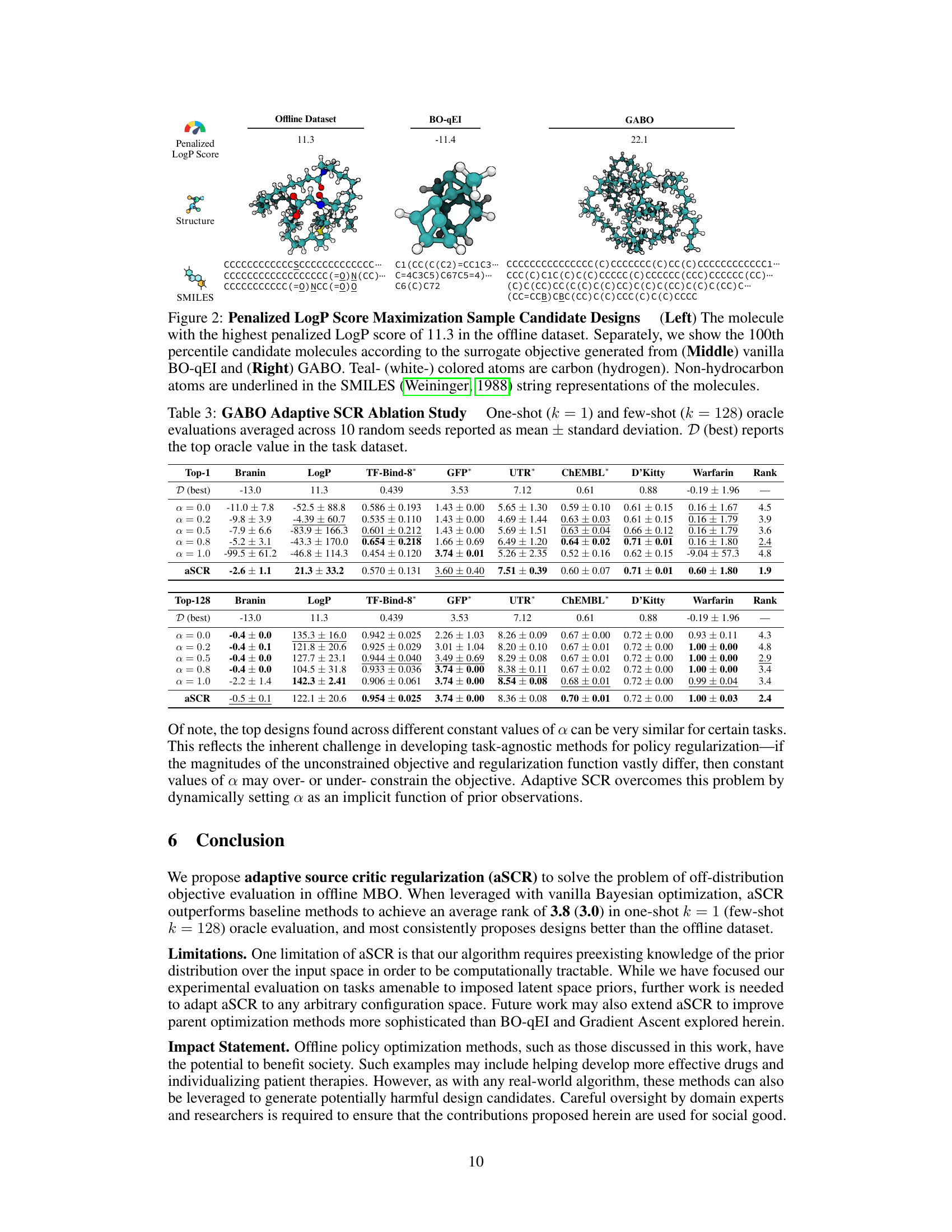

This figure compares three molecules: the best molecule from the offline dataset, the molecule generated by the BO-qEI method, and the molecule generated by the proposed GABO method. It highlights how the proposed method is able to generate a higher-scoring molecule by avoiding overestimation errors in the surrogate model.

This figure compares the top molecule from the offline dataset with the top molecule generated by two different optimization methods, BO-qEI and GABO. The image shows that BO-qEI produces a molecule with rings which results in a lower penalized LogP score. GABO produces a molecule without rings, leading to a higher score.

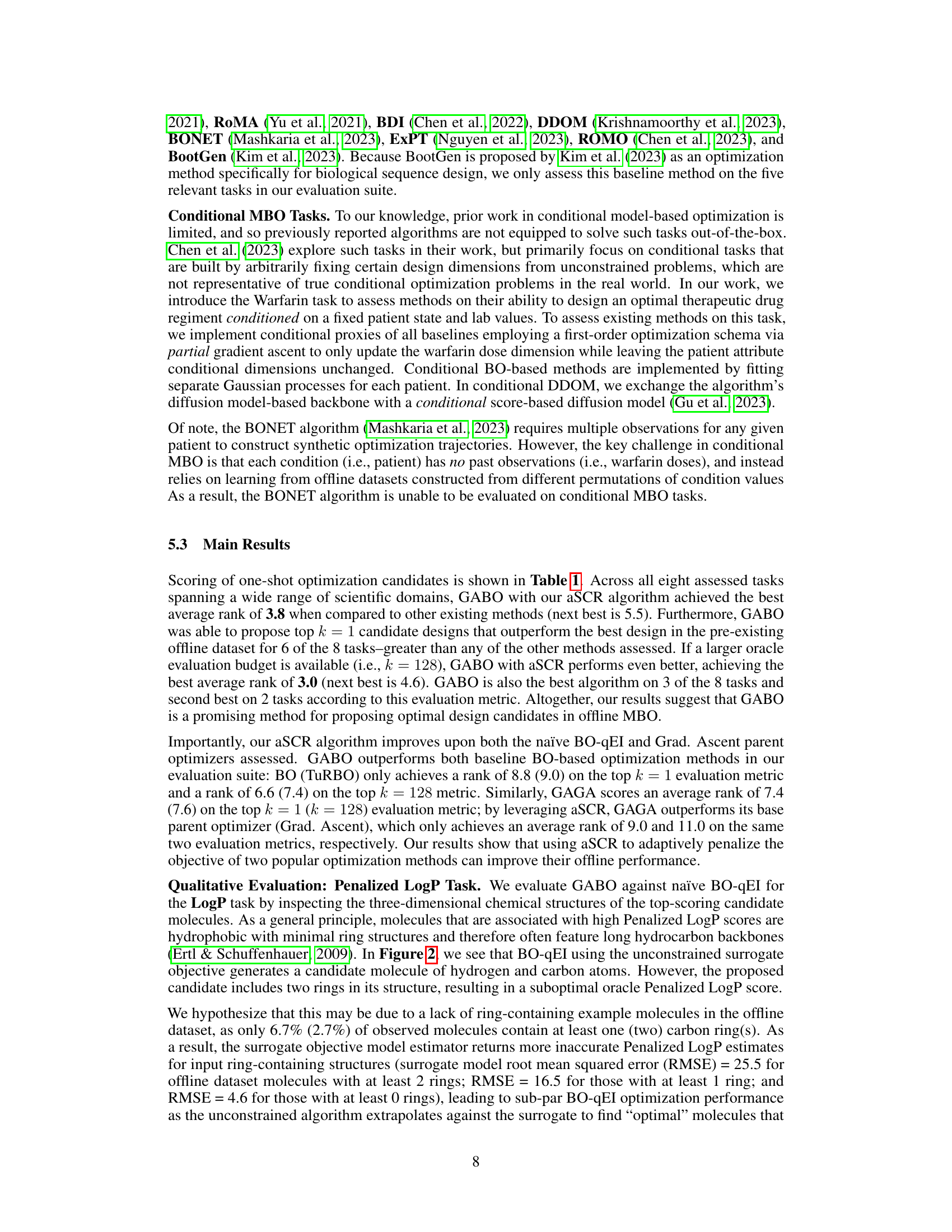

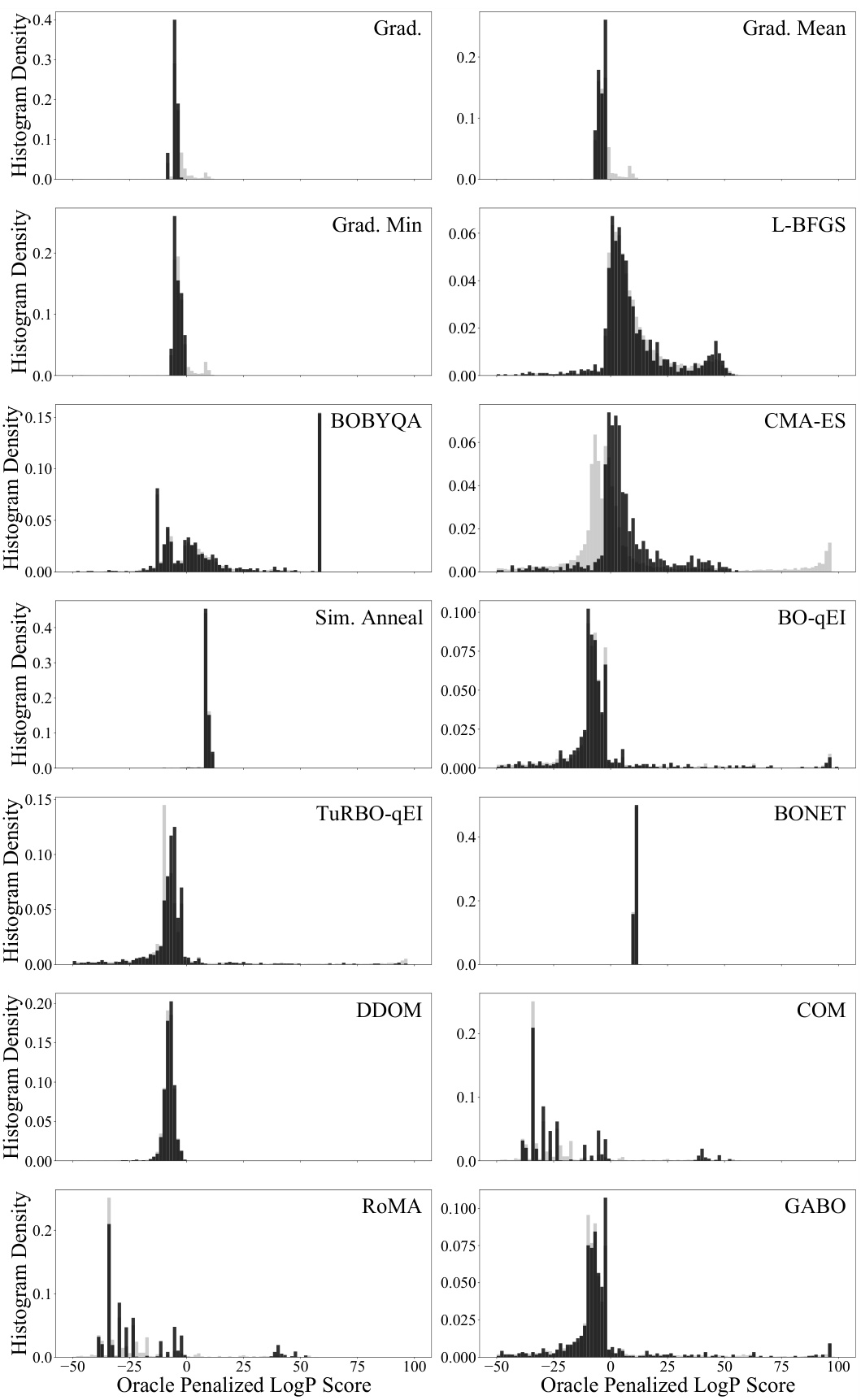

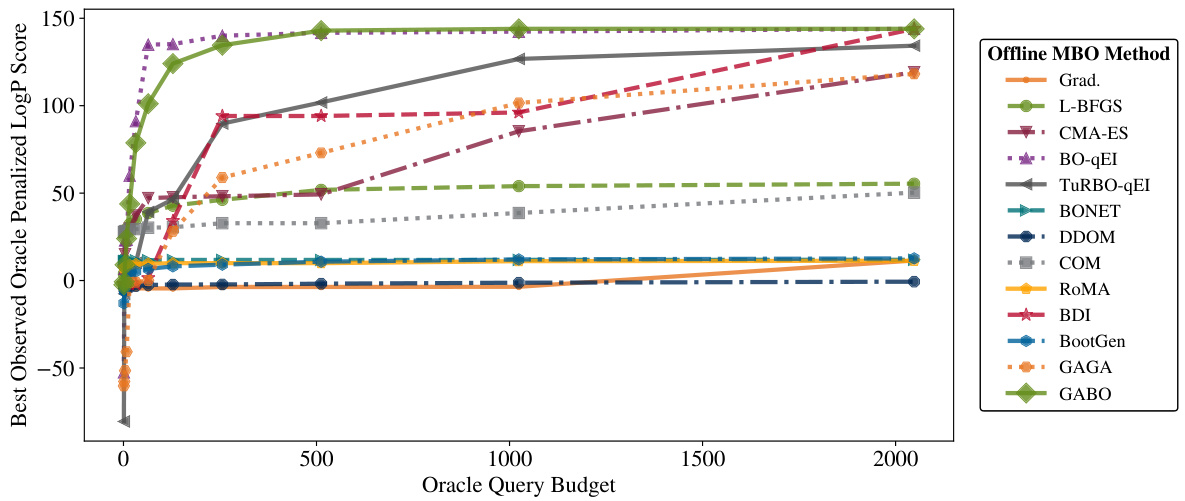

This figure shows the performance of different offline model-based optimization methods for the Penalized LogP task as a function of the number of allowed oracle calls (k). It demonstrates how the best observed oracle score varies across methods as the oracle query budget increases. The graph highlights the relative performance of each algorithm under different resource constraints. The methods compared include gradient ascent, L-BFGS, CMA-ES, standard Bayesian Optimization (BO-qEI), TURBO-qEI, BONET, DDOM, COM, RoMA, BDI, BootGen, GAGA, and GABO.

This figure shows how the best observed oracle penalized LogP score changes as the number of allowed oracle calls (k) increases for various offline model-based optimization (MBO) methods. It demonstrates how the performance of different MBO algorithms varies depending on the oracle query budget. GABO and GAGA, which incorporate the adaptive source critic regularization, show better performance, especially when the budget is limited.

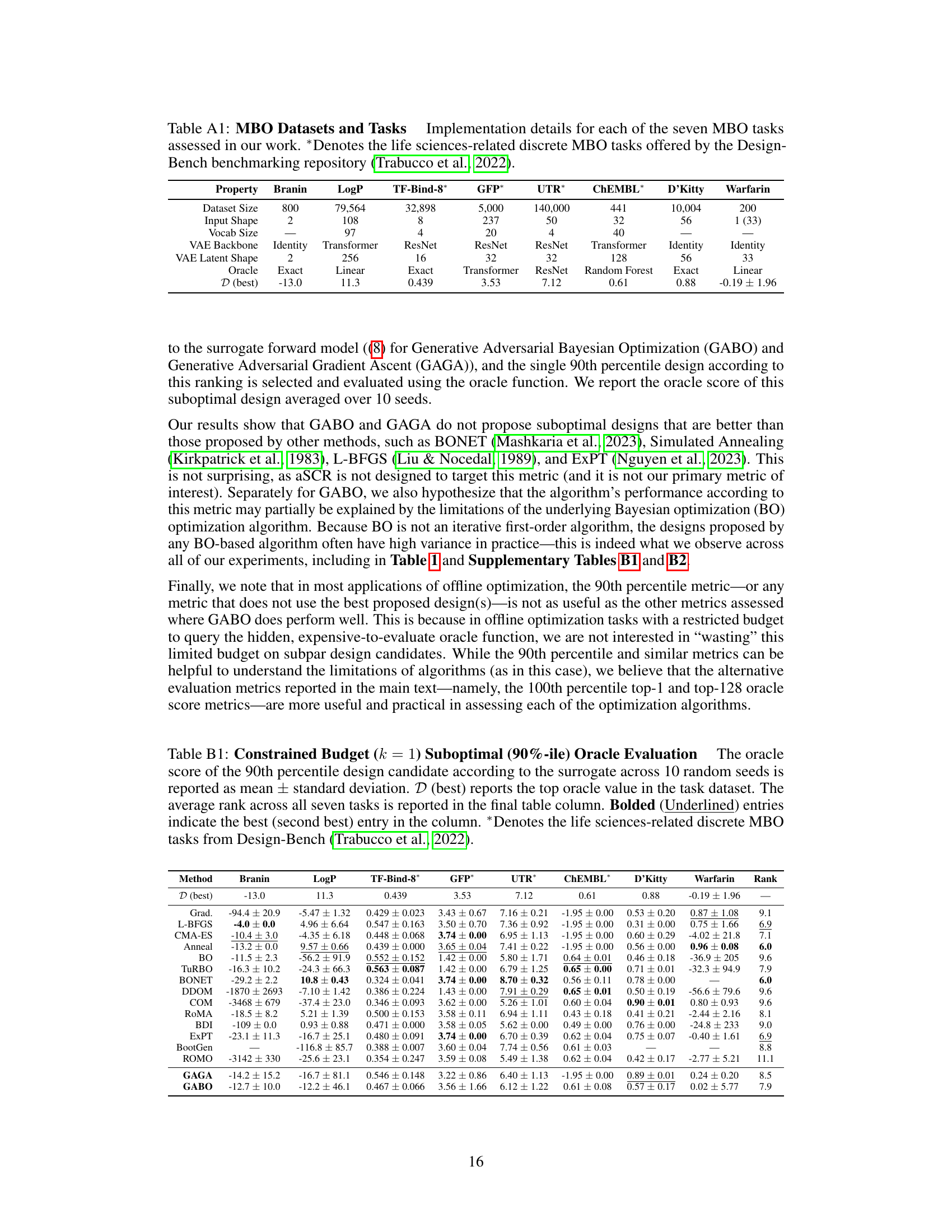

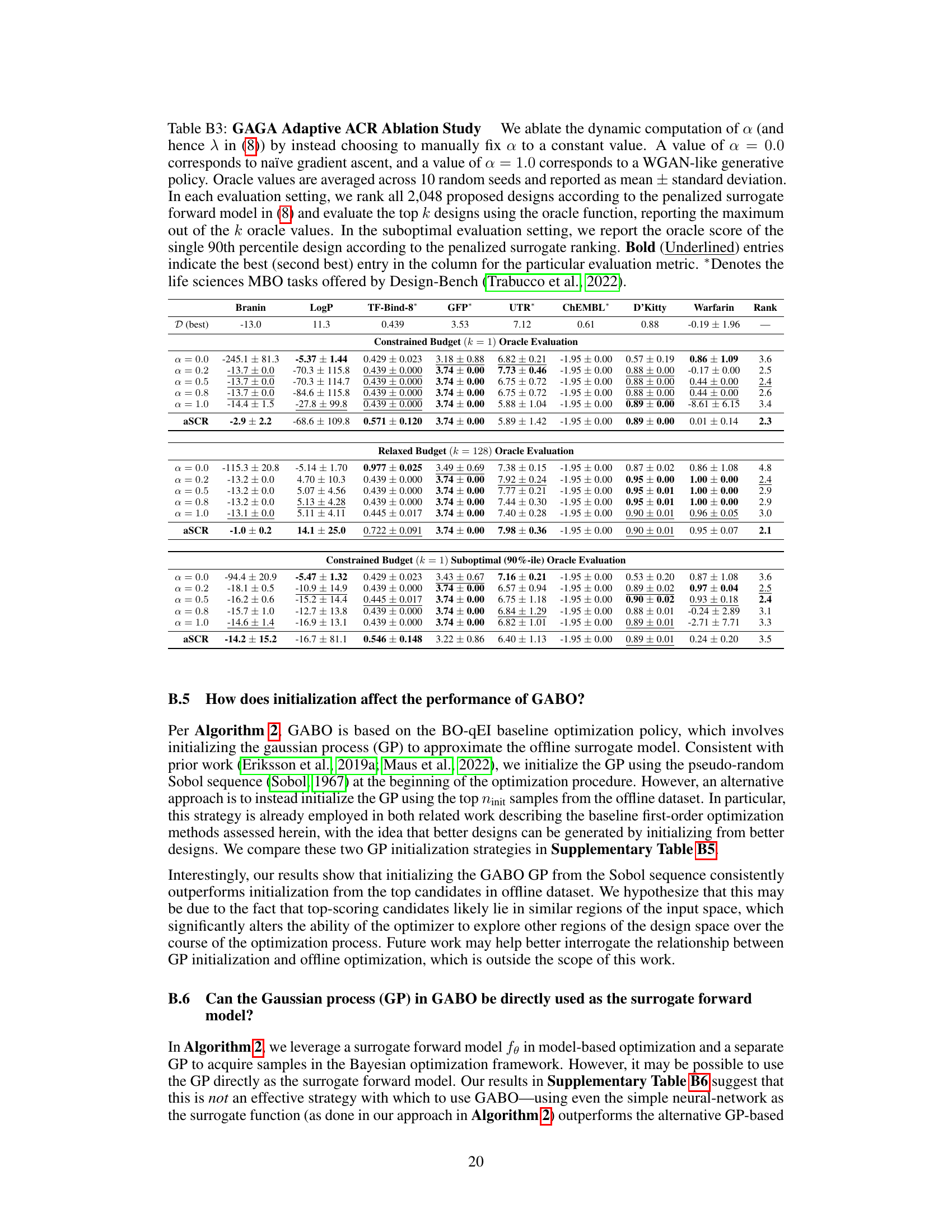

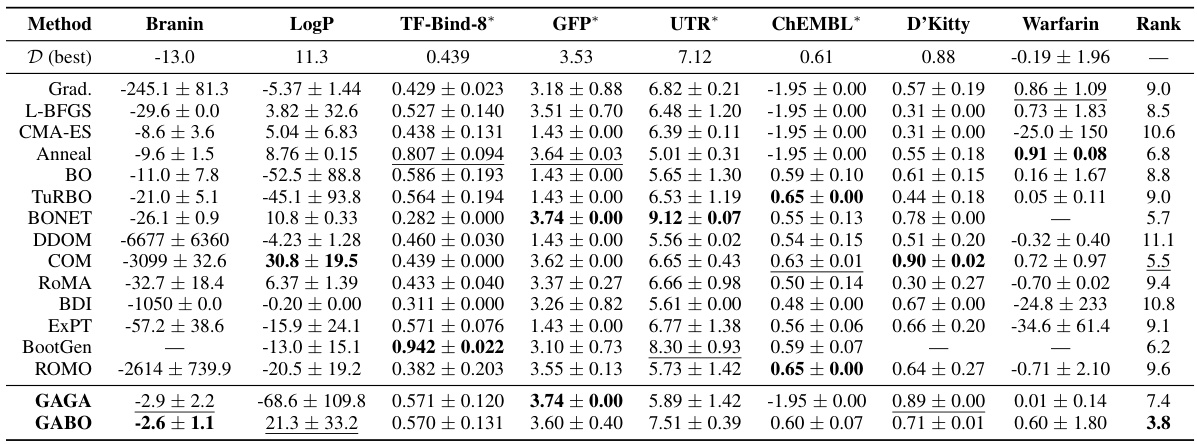

More on tables

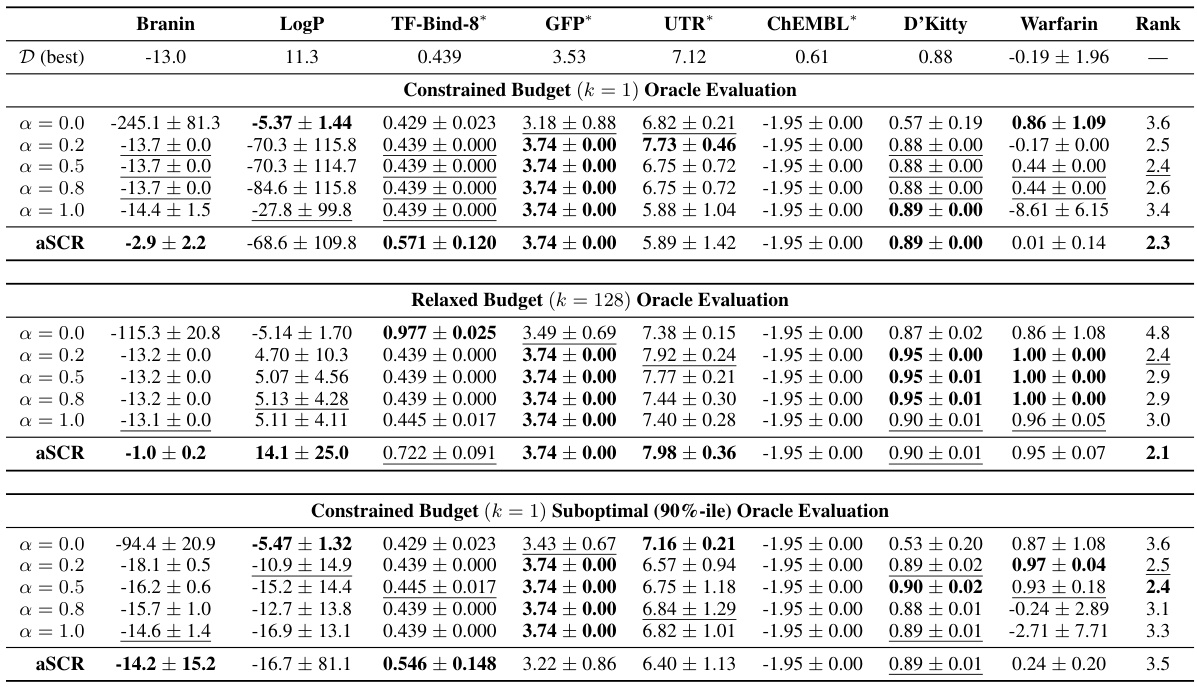

This table presents the results of evaluating different model-based optimization (MBO) methods on eight tasks using a constrained budget of one oracle query (k=1). For each method and task, the table shows the mean and standard deviation of the top-1 oracle score over 10 random trials. The best performing method for each task is bolded. The average rank across all eight tasks is also provided, with a lower average rank indicating better overall performance. The tasks are diverse, spanning multiple domains and including several from the Design-Bench benchmark.

This table presents the results of the constrained budget (k=1) oracle evaluation for eight different optimization tasks using various methods. Each method proposes a single design, which is then evaluated using the oracle function (true objective function). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the scores across 10 random trials for each method on each task. The best observed score in each task’s dataset is also included for comparison. Methods are ranked based on average score across all tasks, and the best and second-best methods for each task are highlighted.

This table presents the results of a constrained budget (k=1) oracle evaluation for eight different tasks. Each optimization method proposes a single design, and its score is evaluated using the oracle function. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the scores across 10 random trials, and ranks each method based on its average score across all tasks. The best and second-best methods for each task are also highlighted.

This table presents the results of the constrained budget (k=1) oracle evaluation for eight different optimization tasks. For each task, multiple optimization methods are compared based on their average rank and the top-performing design’s score using the oracle function. Lower rank indicates better performance. The table includes the best oracle score observed in the dataset as a benchmark. The table highlights the best and second-best performing methods for each task.

This table presents the results of the constrained budget (k=1) oracle evaluation. For each of eight tasks, multiple model-based optimization methods are compared based on their mean score, standard deviation, and average rank. The best performing method for each task, and overall, is highlighted.

This table presents the results of the one-shot (k=1) oracle evaluation for eight different tasks, comparing several model-based optimization (MBO) methods. Each method proposes a single design, which is then evaluated using the true objective function (oracle). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the oracle scores across 10 random trials for each method and task. The best performing method for each task is highlighted in bold, and the average rank across all tasks is included as a final measure of overall performance.

This table presents the results of a constrained budget (k=1) oracle evaluation for eight different model-based optimization (MBO) methods on eight benchmark tasks, including both continuous and discrete tasks from various scientific domains. For each task, the table shows the mean and standard deviation of the oracle score achieved by each method across 10 random trials. It also provides the best oracle score observed in the dataset and the average rank of each method across all tasks. The table highlights the best-performing method for each task.

This table presents the results of the constrained budget (k=1) oracle evaluation. For eight different tasks, various model-based optimization (MBO) methods proposed a single design. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the oracle scores achieved across 10 random trials. The best oracle score from the dataset is included for comparison. Methods are ranked by their average performance across all eight tasks, providing a comprehensive comparison of their effectiveness in this offline optimization scenario.

This table presents the results of the constrained budget (k=1) oracle evaluation for eight different model-based optimization (MBO) tasks. Each method proposes a single design, which is then evaluated using the oracle function. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the scores across 10 random seeds, along with the best observed score from the dataset. Methods are ranked according to their average score across the tasks. The table is broken down by task, with each having its best and second-best performing methods highlighted.

This table shows the computational cost of running the algorithms. It compares the runtime of gradient ascent (Grad.), Generative Adversarial Gradient Ascent (GAGA), Bayesian optimization (BO), and Generative Adversarial Bayesian Optimization (GABO) on the Branin and Penalized LogP tasks. The percent increase in runtime when using Adaptive Source Critic Regularization (aSCR) is also shown. The table highlights that while aSCR adds computational cost, the increase is less significant for the more complex LogP task, suggesting that the added cost is worthwhile for real-world applications.

Full paper#