↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Complex 3D scene understanding is a rapidly growing field, with scene encoding strategies built upon visual foundation models playing a critical role. However, the optimal encoding methods for diverse scenarios remain unclear. This lack of clarity hinders progress in developing robust and efficient scene understanding systems. Existing studies often focus on 2D image-based tasks, leaving 3D scene understanding relatively unexplored.

Lexicon3D directly addresses this gap by presenting the first comprehensive study to probe various visual encoding models (image, video, and 3D) for 3D scene understanding. The researchers evaluate these models across four tasks: Vision-Language Scene Reasoning, Visual Grounding, Segmentation, and Registration. Their findings reveal that unsupervised image foundation models offer superior overall performance. This contrasts with common assumptions that language-guided models are universally better for language related tasks. The study also shows the advantages of video models for object-level tasks and generative models for geometric tasks, highlighting the importance of choosing appropriate encoders for specific tasks and promoting the use of MoVE strategies.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computer vision and natural language processing as it provides a comprehensive benchmark for evaluating various visual foundation models in 3D scene understanding. It challenges existing assumptions, offering novel insights into model selection and highlighting the need for flexible encoder strategies. The findings open avenues for future research on 3D scene understanding and vision-language tasks.

Visual Insights#

This figure shows the evaluation results of seven different vision foundation models (VFMs) on four tasks related to 3D scene understanding: Vision-Language Scene Reasoning, Visual Grounding, Segmentation, and Registration. The VFMs are categorized by input modality (Image, Video, 3D Points) and pretraining task (Self-supervised Learning, Language-guided Learning, Generation). The plot visualizes the performance of each VFM on each task, allowing for comparison across different model types and tasks. This helps to identify the strengths and weaknesses of different VFMs for various 3D scene understanding scenarios.

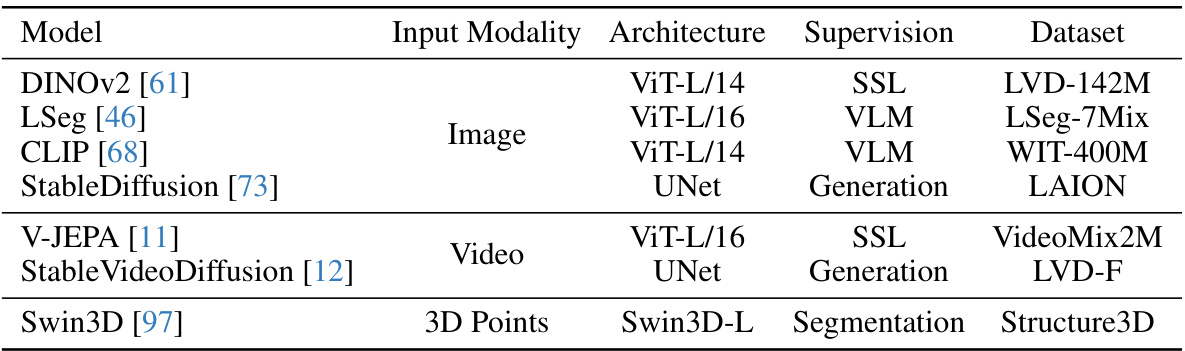

This table lists the seven visual foundation models (VFMs) used in the paper’s experiments. For each model, it specifies the input modality (image, video, or 3D points), the architecture used, the type of supervision (self-supervised learning or vision-language modality alignment), and the dataset used for pretraining. More details about each VFM can be found in Appendix A of the supplementary material.

In-depth insights#

3D Encoding Models#

The effectiveness of 3D scene understanding hinges significantly on robust 3D encoding models. A core challenge lies in selecting optimal encoding strategies, especially when comparing image-based and video-based approaches. Unsupervised image-based models often demonstrate superior performance, likely due to their ability to capture broader scene characteristics and generalize better across various tasks. Conversely, video models often excel in object-level tasks, leveraging the inherent temporal information to improve instance discrimination. The optimal model choice often depends on the specific downstream tasks. Generative models demonstrate unexpected strengths in geometric tasks, highlighting the potential for using different model architectures for different types of 3D scene analysis. Future research should focus on more flexible encoder selection and potentially explore hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of different models for improved performance and generalizability. Mixture-of-expert strategies show promise, but further investigation into optimal model combinations and feature fusion techniques is needed.

Vision-Language Tasks#

Vision-language tasks explore the synergy between visual and textual information processing. They are crucial for bridging the gap between human understanding of scenes and machine perception. Effective vision-language models must seamlessly integrate visual features with semantic information from text, allowing for tasks like image captioning, visual question answering, and visual grounding. A key challenge lies in effectively aligning the different modalities, requiring sophisticated attention mechanisms and multimodal embedding techniques. The success of these models hinges on large-scale datasets combining images and text annotations, enabling the training of powerful, generalizable models. However, challenges remain in handling complex scenes, nuanced language, and diverse visual content. Future work should focus on improving robustness, addressing bias, and broadening the scope of tasks addressed to fully realize the potential of vision-language understanding for applications such as robotics, autonomous driving, and assistive technologies.

MoVE Strategy Benefits#

A hypothetical ‘MoVE Strategy Benefits’ section in a research paper would explore the advantages of a Mixture-of-Vision-Experts (MoVE) approach to 3D scene understanding. MoVE’s core strength lies in its ability to combine the strengths of diverse visual foundation models. This approach would likely outperform single-model encoders, demonstrating improved performance across various downstream tasks like vision-language reasoning, visual grounding, segmentation, and registration. The analysis would likely showcase that MoVE effectively mitigates the limitations of individual models by leveraging their complementary capabilities. For instance, a video model might excel at temporal understanding, while an image model shines in semantic recognition. Combining these strengths within a MoVE architecture would lead to more robust and generalizable scene understanding. The discussion would delve into specific examples illustrating how the combined expertise improves accuracy and reduces reliance on any single model’s weaknesses. Furthermore, it would likely analyze the computational trade-offs, highlighting the efficiency of MoVE strategies relative to training independent, larger models. Finally, it would emphasize the potential of MoVE in future research to enhance flexibility and adaptability to diverse 3D scenarios.

Unsupervised Models Win#

The assertion that “Unsupervised Models Win” requires careful consideration. While the paper might show unsupervised models outperforming supervised ones in specific 3D scene understanding tasks, it’s crucial to avoid overgeneralization. Superior performance in certain tasks doesn’t automatically translate to overall dominance. Factors such as dataset size, task complexity, and specific model architectures significantly influence the results. It’s likely that unsupervised methods excel where labeled data is scarce or expensive to obtain, highlighting their potential for real-world applications. However, supervised models might still retain advantages in scenarios with ample labeled data and well-defined tasks. A nuanced discussion should also acknowledge the potential limitations of unsupervised methods, such as the possibility of learning spurious correlations or lacking the fine-grained control offered by supervised training. Therefore, declaring a definitive “winner” is premature; rather, the findings suggest a more balanced perspective, advocating for model selection based on the specific context and available resources.

Future Research Needs#

Future research should prioritize expanding the scope of visual foundation models beyond indoor scenes to encompass complex outdoor environments, handling dynamic elements like moving objects and changing weather conditions. A deeper investigation into the interplay between different visual encoding models, such as combining image and video features, is crucial for enhancing scene understanding. Exploring more sophisticated strategies for encoder selection and fusion to optimally leverage the strengths of various models, rather than relying on default choices, would yield significant improvements in performance and generalization. Finally, research should address the computational cost and memory constraints associated with large models, exploring efficient training and inference methods to enable wider adoption of these advanced scene understanding techniques. Addressing these key areas will unlock the full potential of visual foundation models for real-world applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

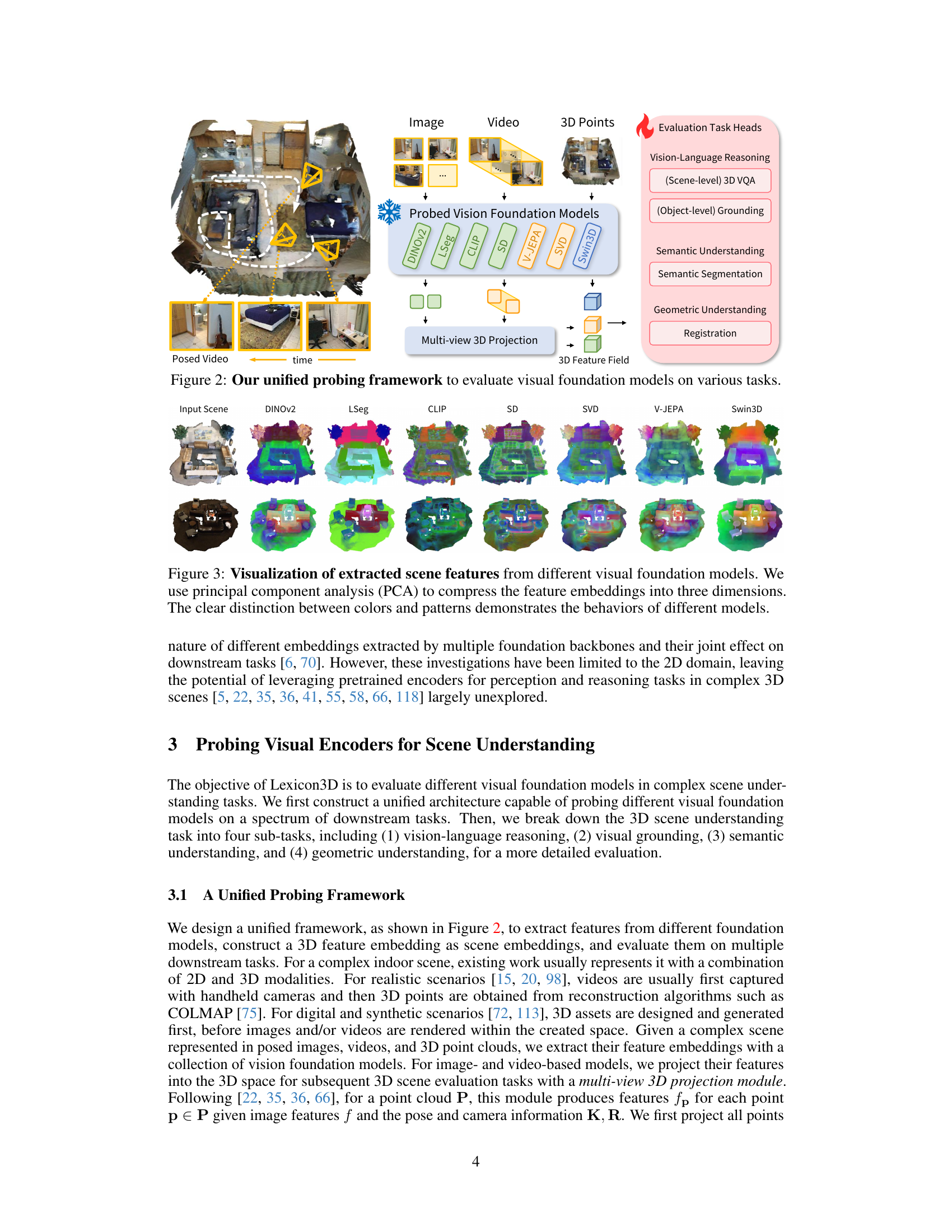

This figure illustrates the architecture used to evaluate various visual foundation models on different tasks related to 3D scene understanding. The framework takes as input posed images, videos, and 3D points representing the scene. These are then fed into seven different vision foundation models (DINOv2, LSeg, CLIP, Stable Diffusion, V-JEPA, Stable Video Diffusion, Swin3D). A multi-view 3D projection module projects image and video features into 3D space to create a consistent 3D feature field. This 3D feature field is then used to perform four different downstream tasks: Vision-Language Scene Reasoning (assessing scene-level understanding), Visual Grounding (evaluating object-level understanding), Semantic Segmentation (measuring semantic understanding), and Registration (testing geometric understanding). The figure clearly depicts the unified workflow for evaluating different models and showcases the multi-faceted evaluation approach.

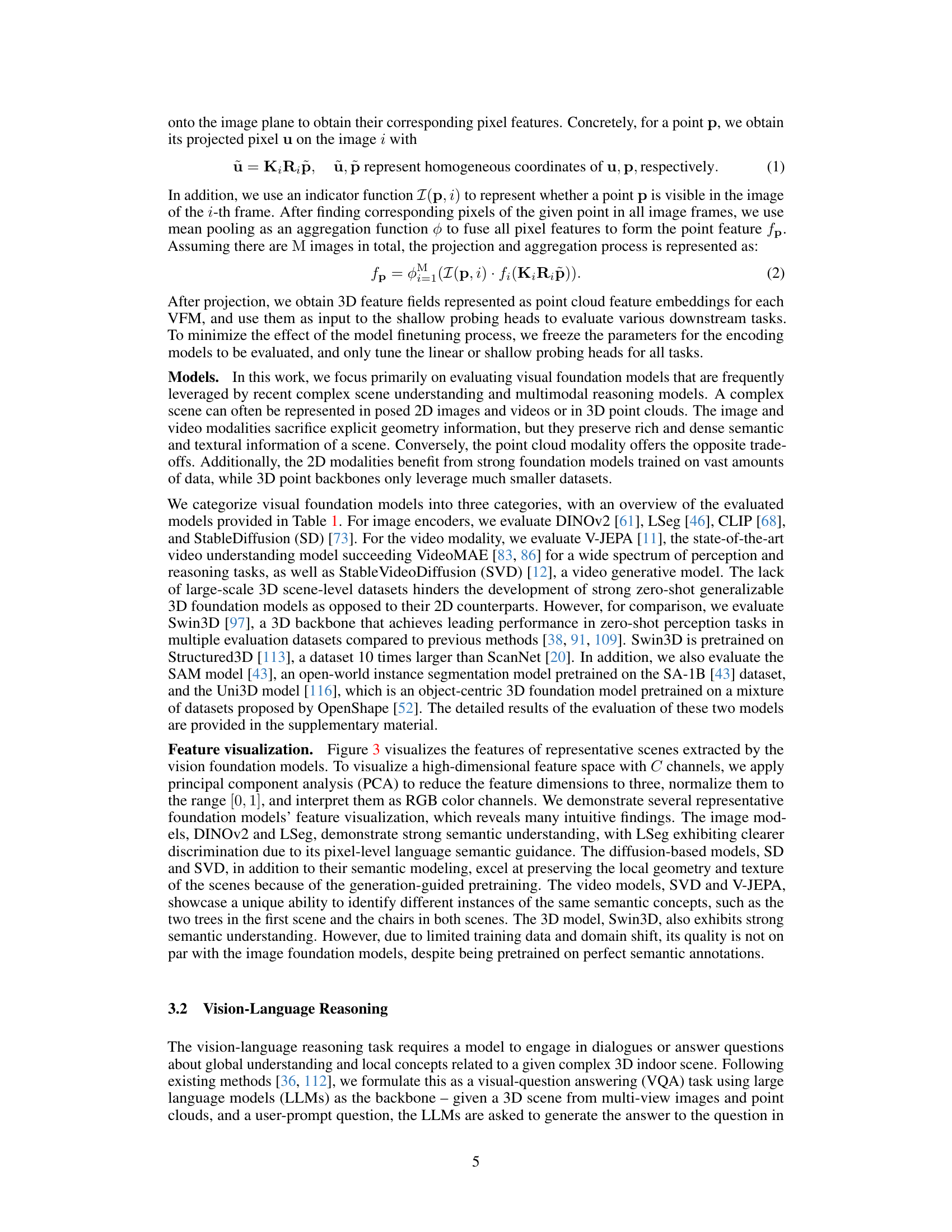

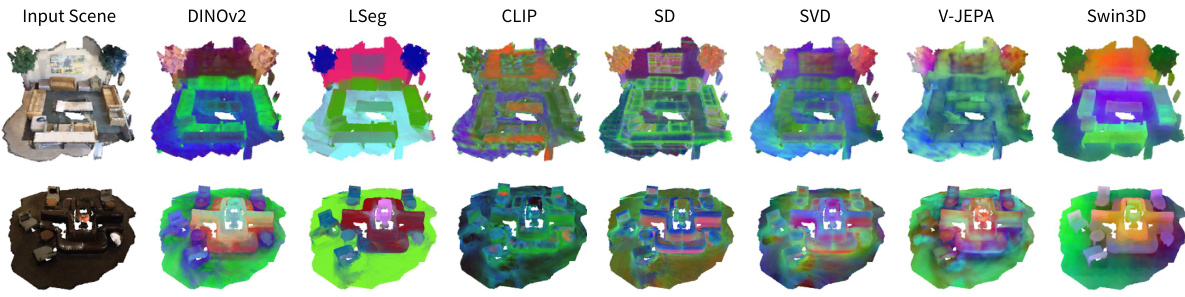

This figure visualizes the features extracted by different visual foundation models (VFMs) using principal component analysis (PCA) to reduce dimensionality to 3D for better visualization. The resulting visualizations show distinct patterns and colors for each model, highlighting their unique feature representations and demonstrating how different VFMs capture different aspects of the scene.

This figure summarizes the experimental setup and key findings of the Lexicon3D paper. It shows the performance of seven different vision foundation models (VFMs) across four scene understanding tasks: Vision-Language Scene Reasoning, Visual Grounding, Semantic Segmentation, and Registration. The VFMs are categorized by input modality (image, video, 3D points) and pretraining task (self-supervised learning, language-guided learning, generation). The results highlight the strengths and weaknesses of each model type across different tasks, revealing for example, that unsupervised image foundation models generally perform best overall, while video models excel in object-level tasks, and diffusion models are beneficial for geometric tasks. The figure uses a scatter plot to visualize the performance of each VFM on each task, providing a concise overview of the extensive evaluation reported in the paper.

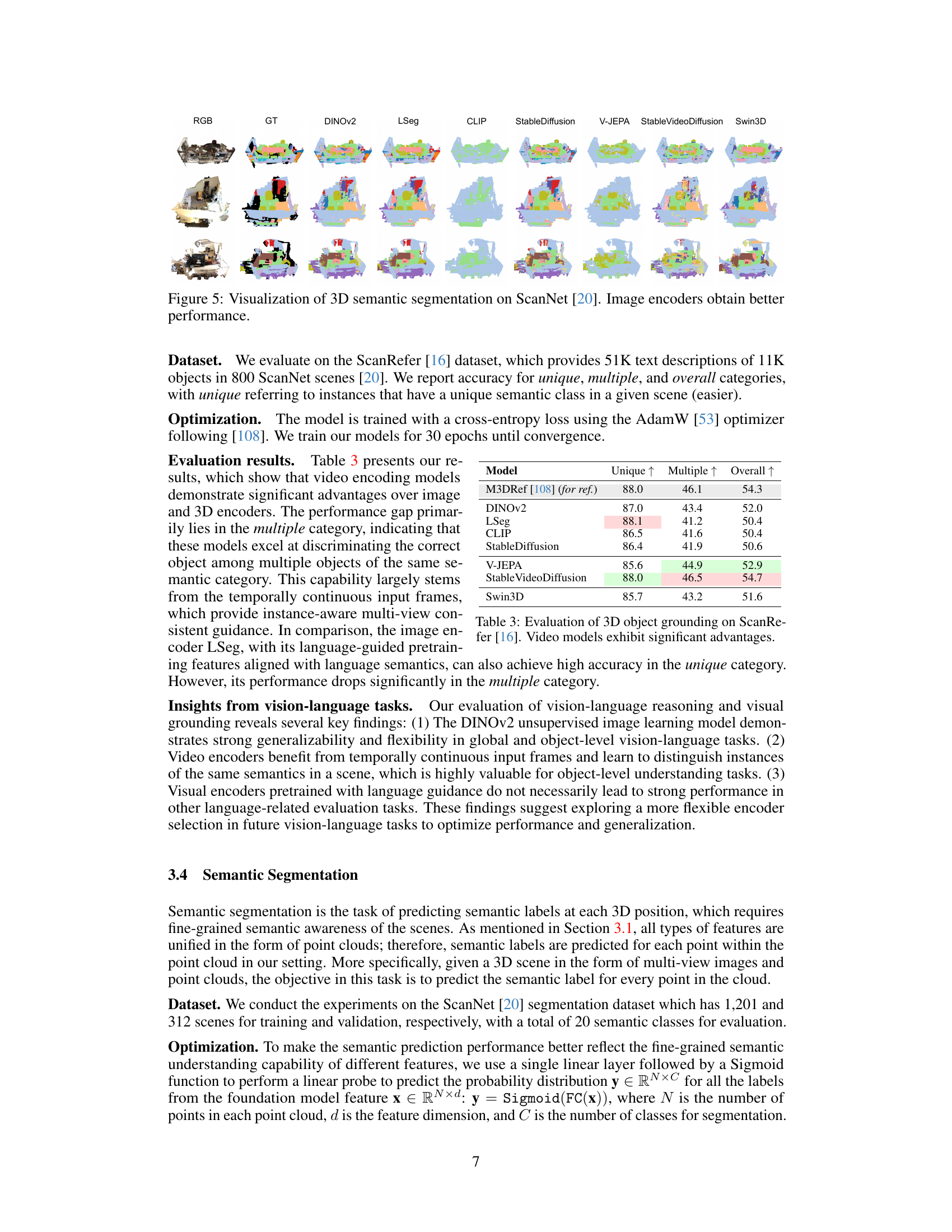

This figure visualizes the results of 3D semantic segmentation on the ScanNet dataset using different vision foundation models. Each row shows a different scene with the RGB image, ground truth segmentation, and the segmentation results obtained by seven different models: DINOv2, LSeg, CLIP, Stable Diffusion, V-JEPA, Stable Video Diffusion, and Swin3D. The results demonstrate that image-based encoders generally achieve superior performance compared to video-based and 3D point-based encoders in semantic segmentation.

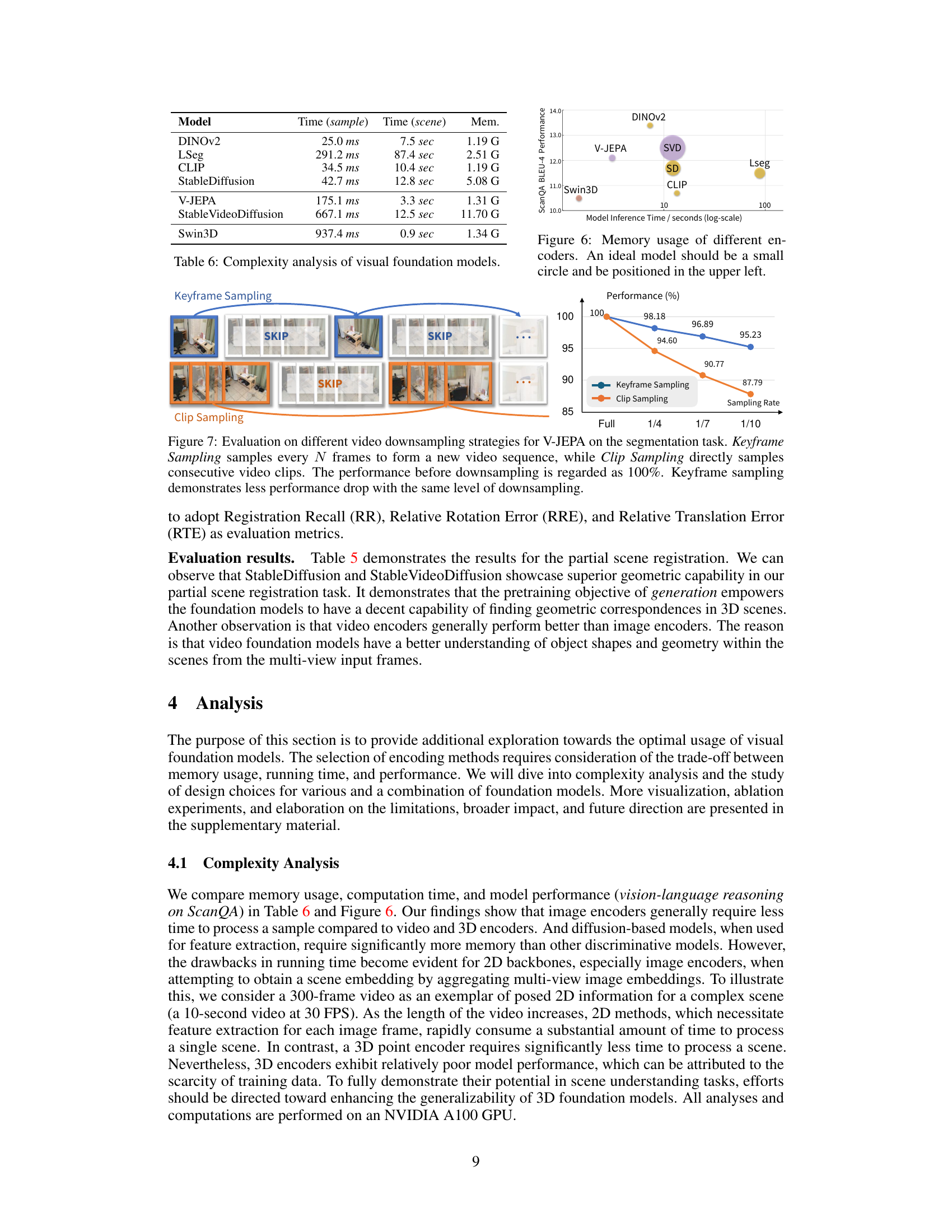

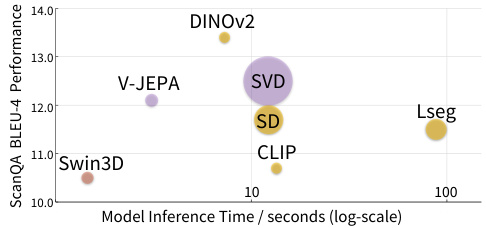

This figure visualizes the memory usage and inference time of different visual foundation models used in the paper. Each model is represented by a circle, where the horizontal position represents inference time (log scale) and the vertical position represents ScanQA BLEU-4 performance. Ideally, a model would have both low memory usage and high performance, placing it in the upper-left corner of the graph. The size of the circle is proportional to the memory used.

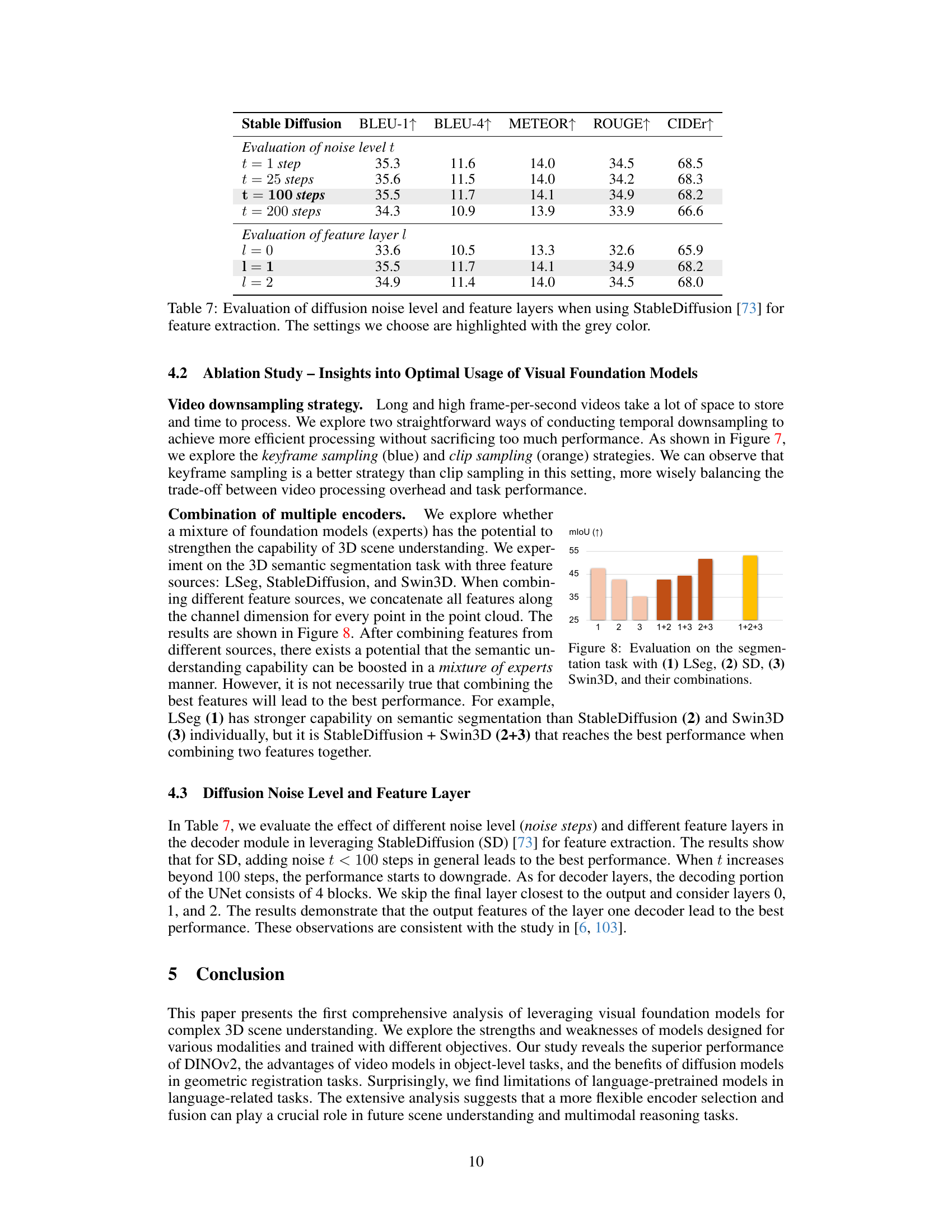

This figure compares two video downsampling strategies: keyframe sampling and clip sampling. Keyframe sampling selects frames at regular intervals, while clip sampling takes consecutive sequences. The results show that keyframe sampling preserves performance better than clip sampling when reducing the number of frames.

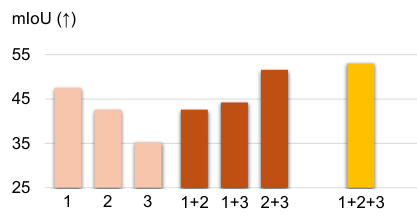

This figure visualizes the results of an ablation study on the semantic segmentation task. It shows the performance of using different combinations of three visual foundation models (LSeg, Stable Diffusion, and Swin3D). Each model’s features are concatenated, and the resulting mIoU is measured. The results indicate that combining multiple encoders, particularly LSeg and Swin3D, can improve performance. However, simply combining the three best-performing individual models (1+2+3) doesn’t necessarily guarantee the best overall performance. The experiment highlights the potential benefits and complexities of leveraging multiple visual foundation models for scene understanding tasks.

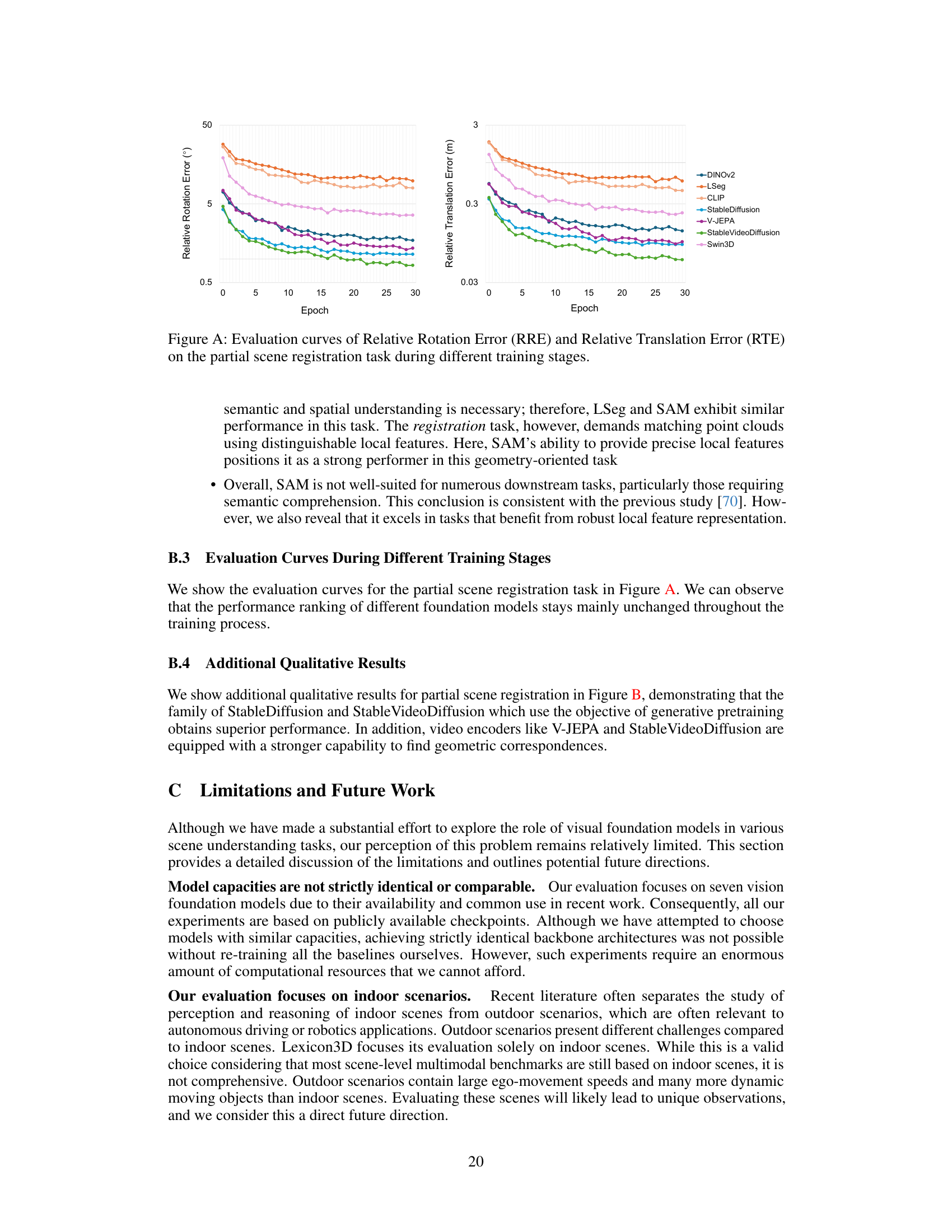

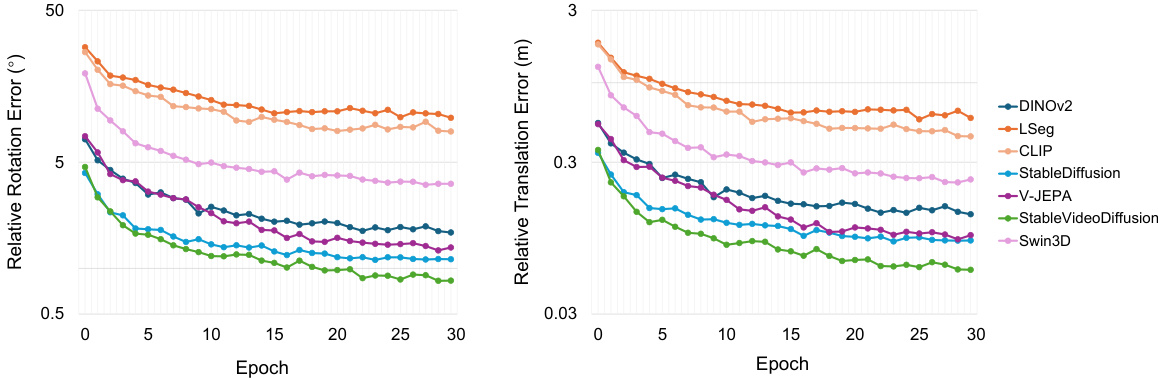

The figure shows the relative rotation error (RRE) and relative translation error (RTE) during the training of a partial scene registration task using different vision foundation models. The x-axis represents the training epoch, and the y-axis shows the error metric. The lines represent different models’ performance over the training epochs, allowing for a visual comparison of their convergence rates and final accuracy. This visualization helps to understand how different models learn to align point clouds in a partial scene registration scenario. Notably, models like StableDiffusion and StableVideoDiffusion show relatively lower error rates and faster convergence compared to others.

This figure visualizes the results of partial scene registration for different vision foundation models. The visualizations show two partial point clouds, P1 and P2, overlaid on top of each other, with a color-coded representation of the registration quality. The models that achieved higher accuracy in the registration task are displayed with more accurate alignment of the two point clouds. Specifically, Stable Diffusion and Stable Video Diffusion models show better registration performance, and video-based models (V-JEPA and Stable Video Diffusion) generally perform better than image-based models. This illustrates that generative models and models with temporal information are better suited for this geometric task.

More on tables

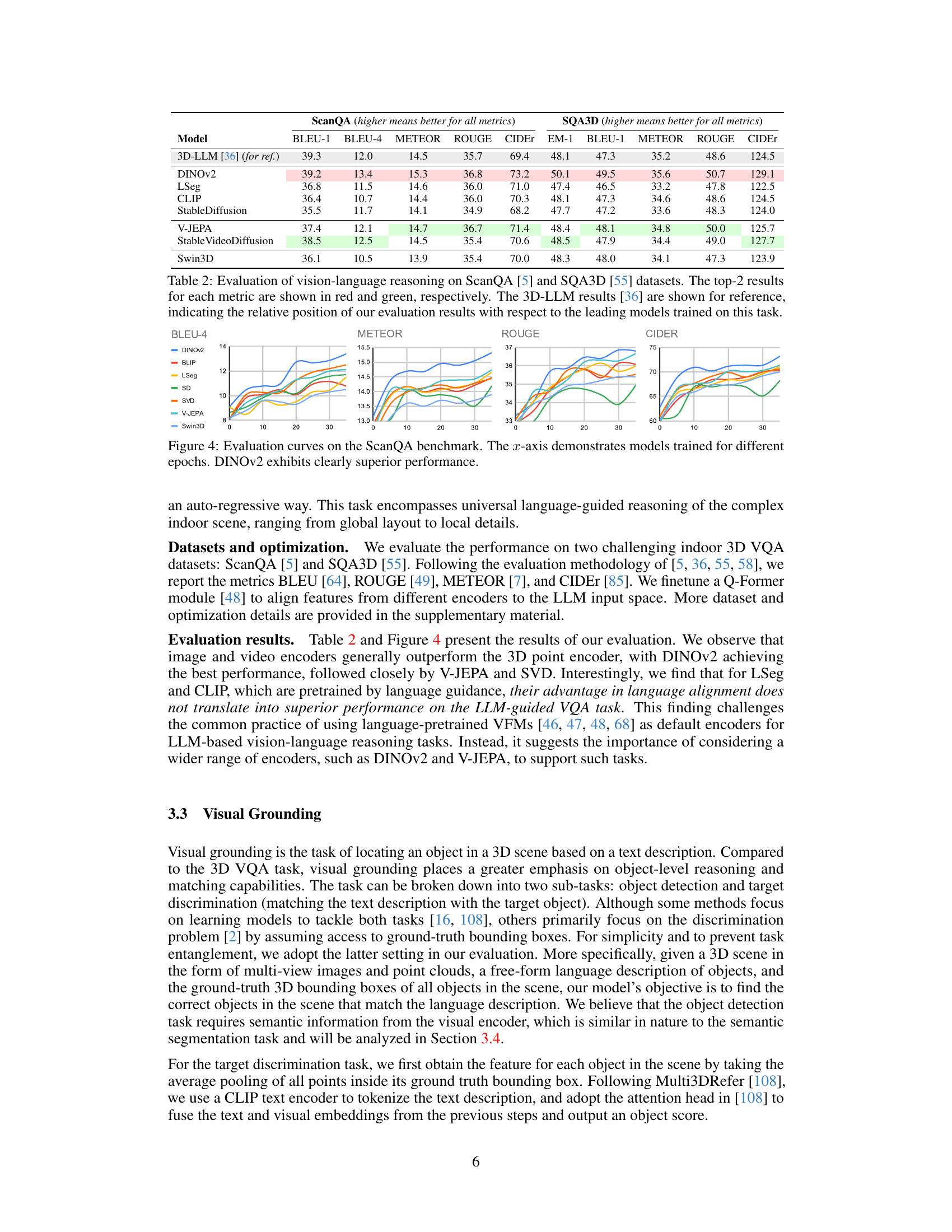

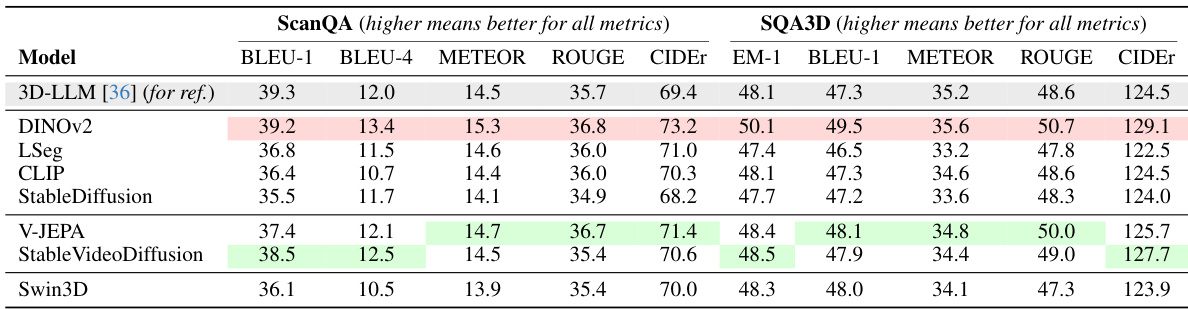

This table presents the quantitative results of vision-language reasoning experiments conducted on two benchmark datasets: ScanQA and SQA3D. Seven different vision foundation models (VFMs) are evaluated based on several metrics (BLEU-1, BLEU-4, METEOR, ROUGE, CIDEr, EM-1). The results highlight the relative performance of different VFMs in this task and compare them to a state-of-the-art model (3D-LLM) for reference. The top two performing models for each metric are highlighted.

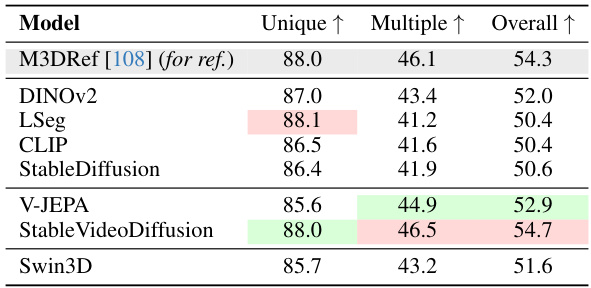

This table presents the results of the 3D object grounding task evaluation on the ScanRefer dataset. It compares the performance of seven different vision foundation models (VFMs) across three categories: Unique (objects with a single semantic class in the scene), Multiple (objects with multiple instances of the same semantic class), and Overall (all objects). The results show that video encoding models significantly outperform image and 3D encoders, particularly in the Multiple category, highlighting the advantage of temporal information in distinguishing objects of the same semantic class.

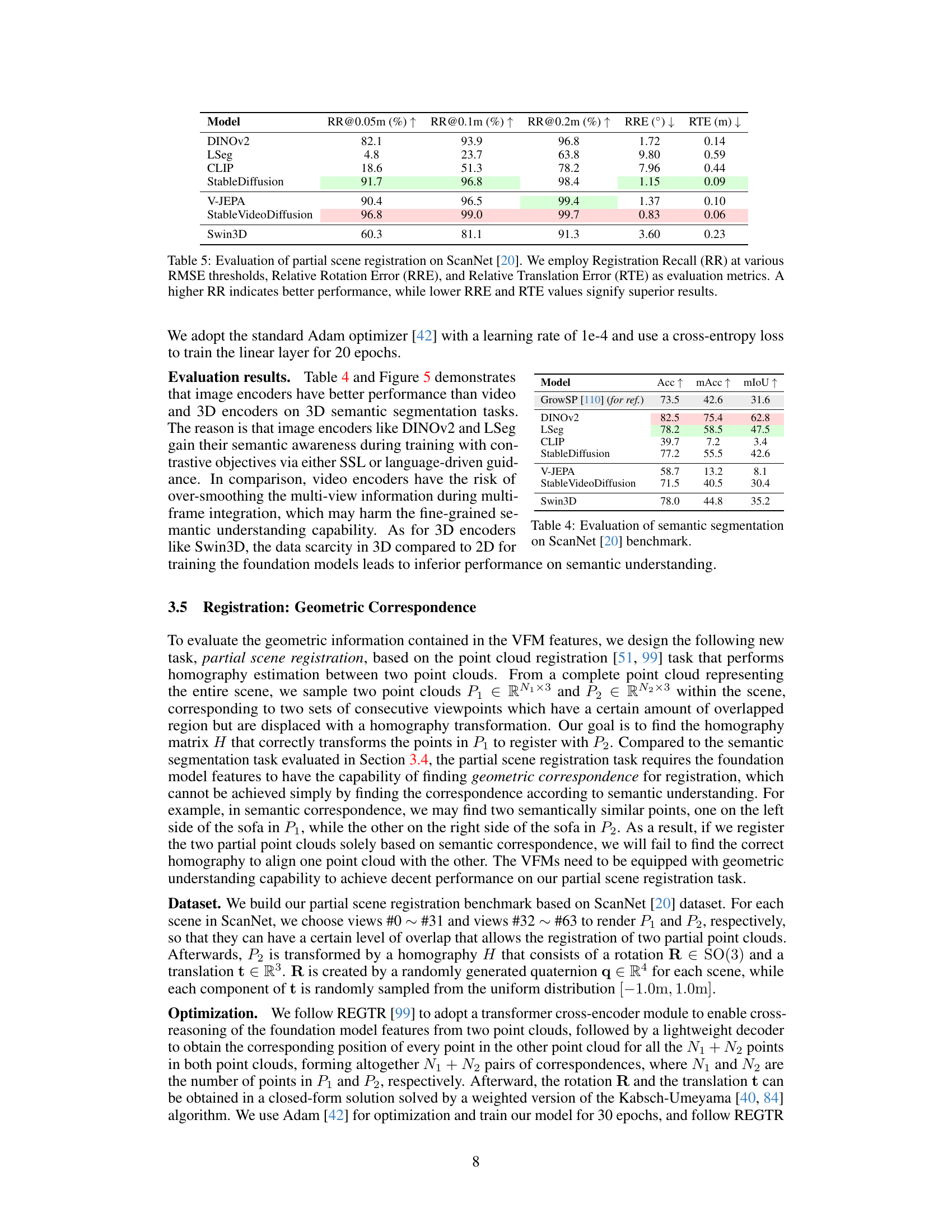

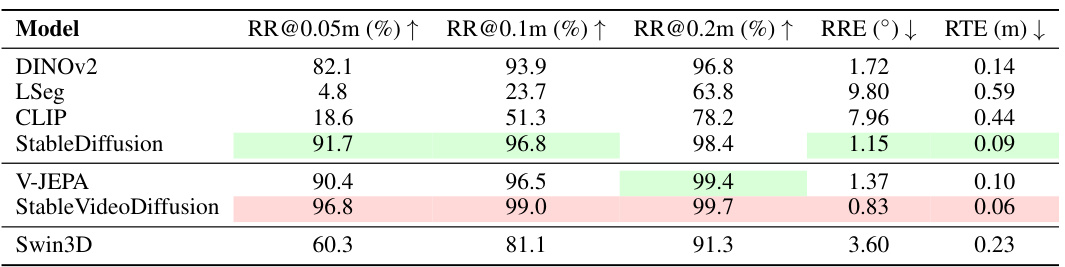

This table presents the results of evaluating seven different visual foundation models on a partial scene registration task using the ScanNet dataset. The models are assessed based on three metrics: Registration Recall (RR) at different distances (0.05m, 0.1m, 0.2m), Relative Rotation Error (RRE), and Relative Translation Error (RTE). Higher RR values indicate better performance, while lower RRE and RTE values are preferred. The table shows that Stable Diffusion and Stable Video Diffusion models achieve the highest RR values and lowest error values, suggesting their superiority in this specific task compared to other models tested.

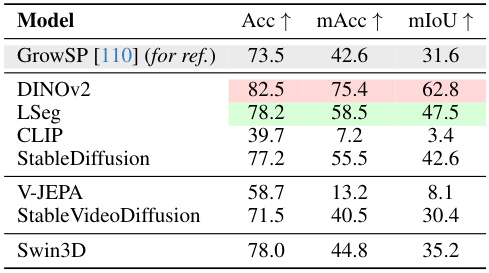

This table presents the results of the semantic segmentation task on the ScanNet benchmark. It compares the performance of different vision foundation models (VFMs) in terms of accuracy (Acc), mean accuracy (mAcc), and mean Intersection over Union (mIoU). Higher values indicate better performance. The table includes results for DINOv2, LSeg, CLIP, Stable Diffusion, V-JEPA, Stable Video Diffusion, and Swin3D, with a comparison to the GrowSP baseline.

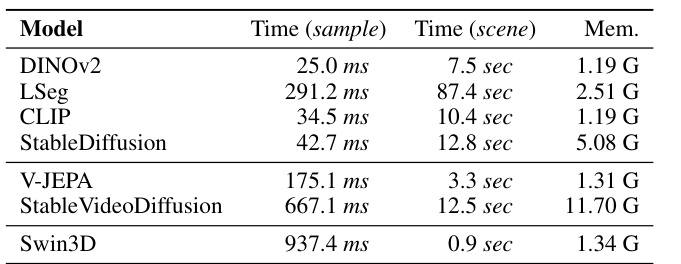

This table presents a complexity analysis of seven different visual foundation models. It shows the time taken to process a single sample, the time to process an entire scene, and the memory usage for each model. The models are compared across various metrics to provide insights into their computational efficiency and resource requirements for 3D scene understanding.

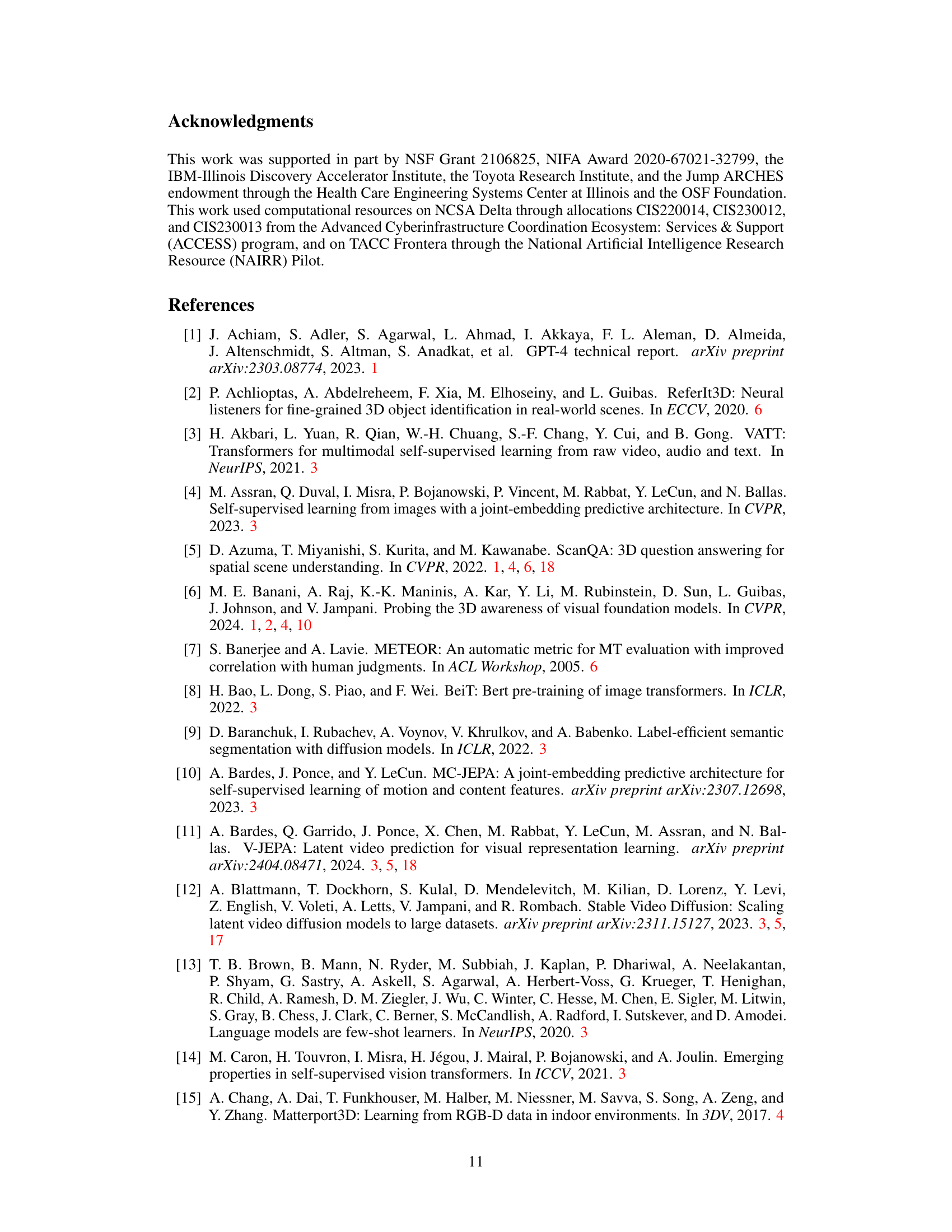

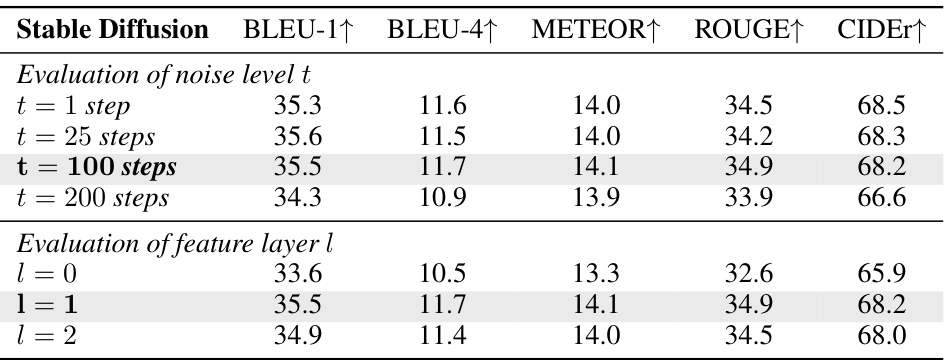

This table presents the ablation study on Stable Diffusion model, evaluating the impact of different noise levels and feature layers on the model’s performance. The noise levels refer to the number of steps in the diffusion process, while the feature layers correspond to different layers in the decoder network. The results show that the optimal noise level is 100 steps and the optimal feature layer is 1, suggesting the importance of choosing the right hyperparameters in using Stable Diffusion for feature extraction tasks.

This table compares the performance of two different 3D foundation models, Uni3D and Swin3D, across four scene understanding tasks: Vision-Language Question Answering (VQA), Visual Grounding, Semantic Segmentation, and Registration. Uni3D, being object-centric, focuses on individual objects within a scene, while Swin3D takes a scene-centric approach, considering the overall scene context. The table highlights the significant performance differences between these two approaches across the four tasks, demonstrating the impact of model architecture and training strategy on downstream scene understanding capabilities.

This table compares the performance of two different models, SAM (Segment Anything Model) and LSeg, across four tasks related to 3D scene understanding. SAM is an instance segmentation model, focusing on identifying individual objects within a scene, while LSeg is a semantic segmentation model, focusing on assigning semantic labels to each pixel. The tasks evaluated include Vision-Language Reasoning, Visual Grounding, Semantic Segmentation, and Registration. The results highlight that the choice of model significantly affects performance across these different aspects of 3D scene understanding, with SAM excelling in tasks requiring precise object localization and LSeg performing better on tasks requiring semantic understanding.

Full paper#