↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Estimating causal effects is challenging when multiple units interact, creating interference. Conventional methods often assume no or limited interference, leading to biased estimates, especially in social sciences and online marketplaces where pervasive interference is common. Existing methods also often assume that the interaction network is known, which is often unrealistic.

This paper introduces Higher-Order Causal Message Passing (HO-CMP) to solve this problem. HO-CMP uses data over time, sample means and variances to learn how outcomes evolve after applying treatment. It uses non-linear machine learning features to model this evolution and estimates the total treatment effect (TTE), outperforming existing techniques in various simulation settings, including those with non-monotonic interference.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers dealing with causal inference in complex systems. It offers robust and efficient methods for estimating treatment effects in scenarios with pervasive, unobserved interference, significantly advancing the field beyond existing approaches that often rely on restrictive assumptions. The proposed framework opens new avenues for designing and analyzing experiments across various domains, impacting social sciences, online platforms, and beyond.

Visual Insights#

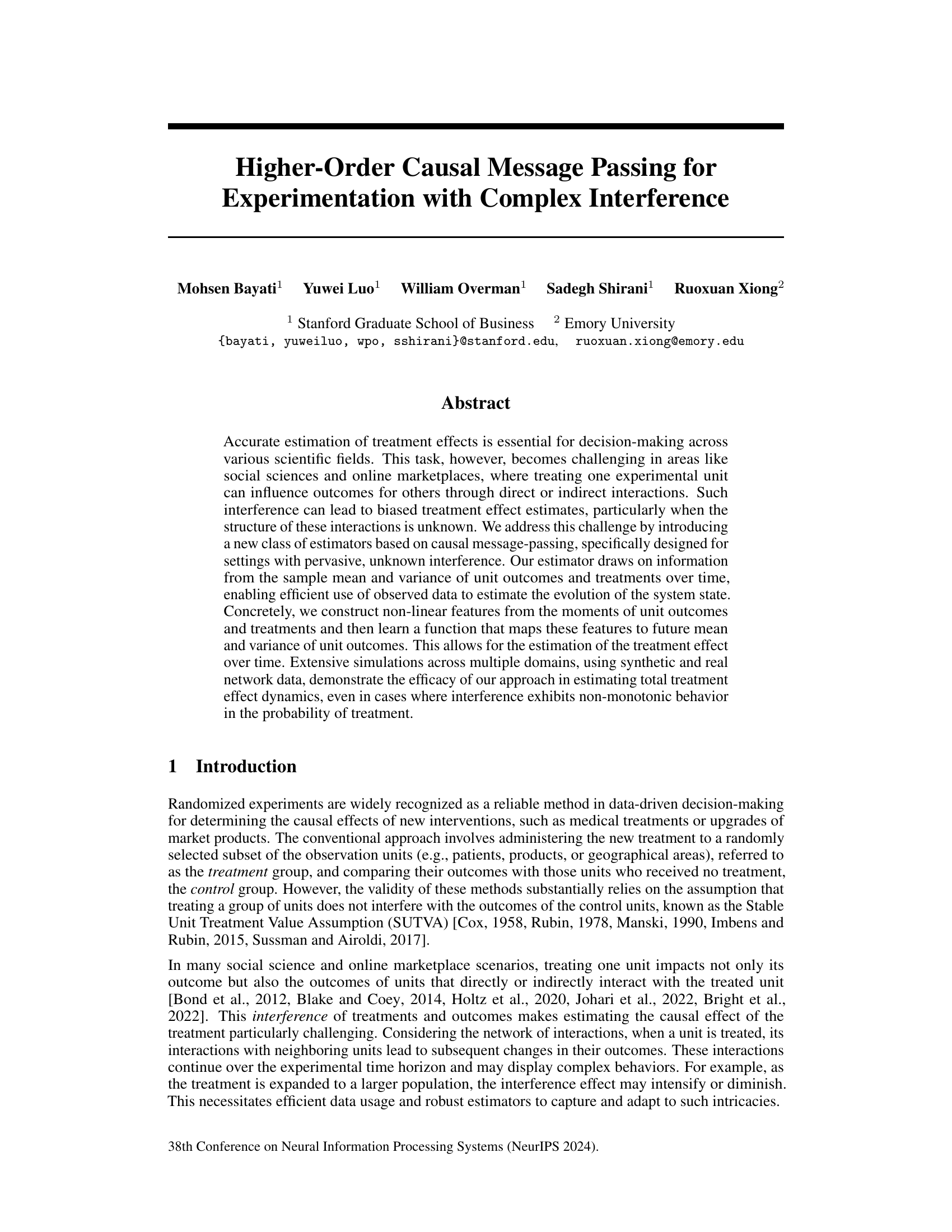

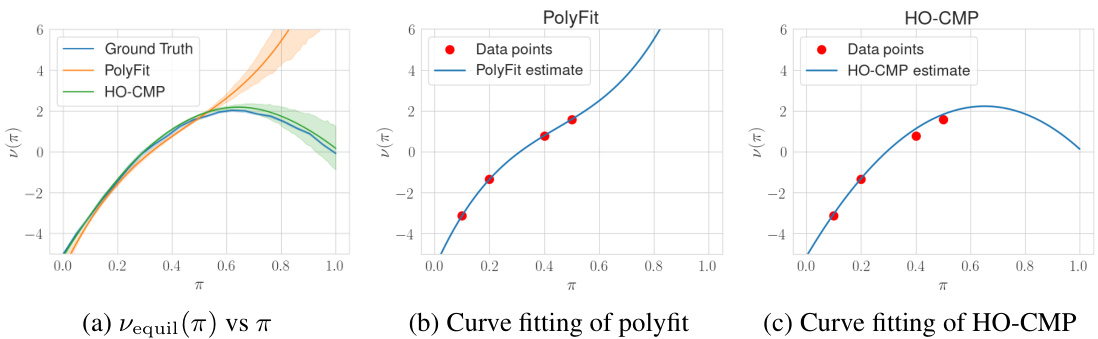

This figure compares the estimates of Vequil(π) (the average outcome at equilibrium for a given treatment probability π) obtained using PolyFit and HO-CMP methods against the ground truth. Panel (a) shows the average estimates across multiple runs for both methods, highlighting their performance in approximating the true function. Panels (b) and (c) provide a closer look at individual runs for both methods, demonstrating how well they fit the observed data points for the Non-LinearInMeans outcome specification. The Non-LinearInMeans specification means that the outcome is a non-linear function of the fraction of treated neighbors, making it a more challenging scenario for causal effect estimation.

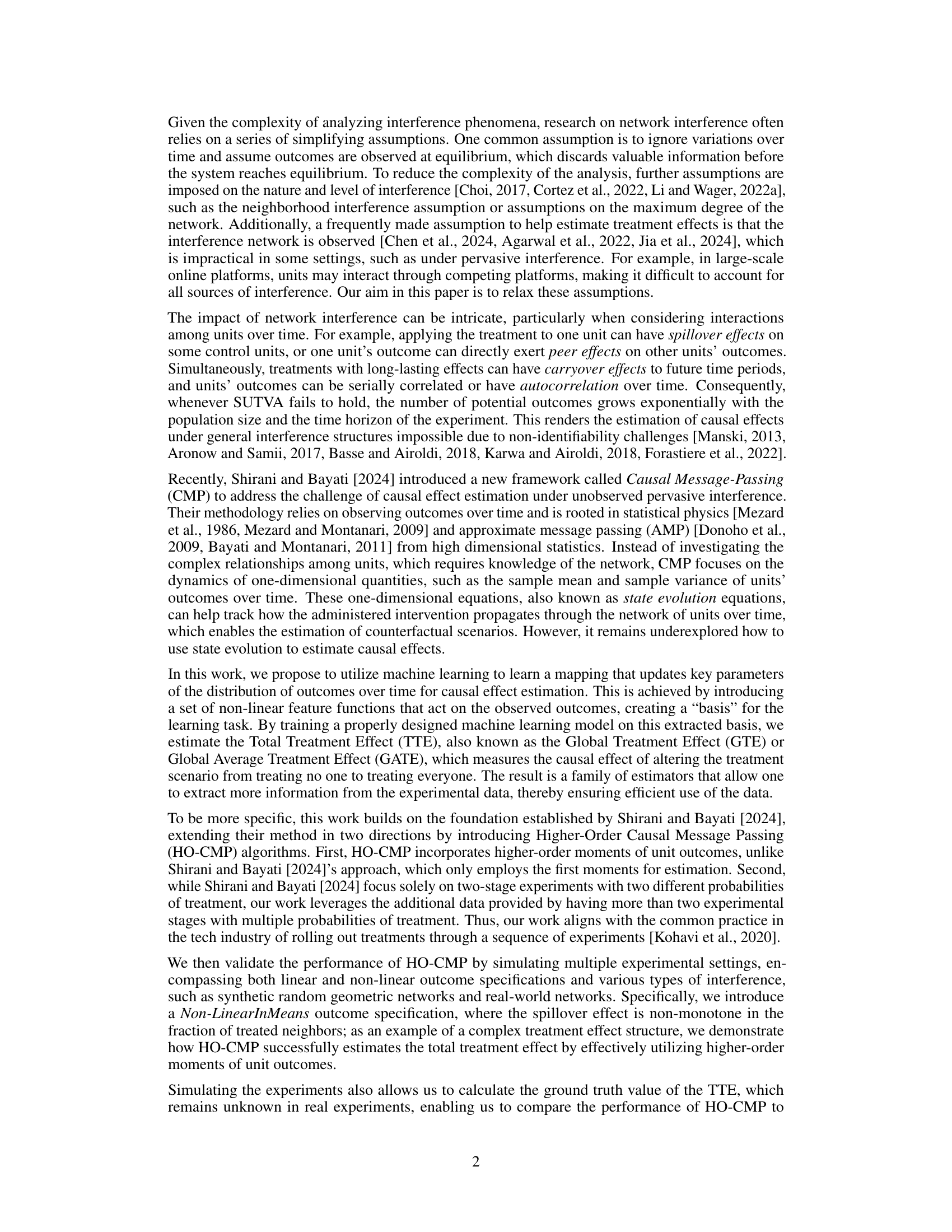

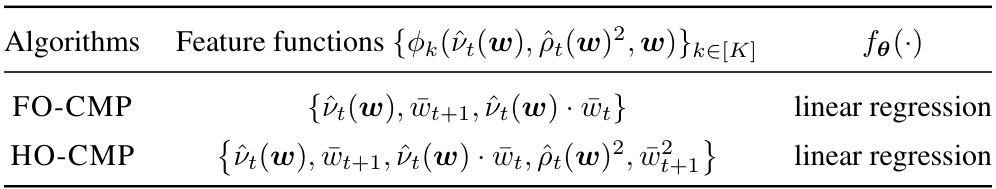

This table presents two examples of feature functions used in the Higher-Order Causal Message-Passing (HO-CMP) algorithm. The feature functions are used as input to a machine learning model to learn the dynamics of the system. FO-CMP uses only first order moments and a simpler set of features, while HO-CMP expands to include second-order moments, enabling better capture of nonlinear dynamics.

In-depth insights#

Higher-Order CMP#

Higher-Order Causal Message Passing (HO-CMP) builds upon the foundation of Causal Message Passing (CMP) by incorporating higher-order moments of unit outcomes and treatments. This enhancement allows HO-CMP to capture more nuanced dynamics in systems with complex interference, going beyond the limitations of first-order methods. By leveraging these higher-order moments, HO-CMP can effectively learn a more accurate mapping between observed data features and the evolution of the system state, ultimately leading to more precise estimation of the total treatment effect. This is particularly crucial in scenarios exhibiting non-monotonic interference effects, where simpler methods might fail to capture the intricate relationships between treatment and outcomes. The method demonstrates improvements in accuracy and robustness compared to both first-order CMP and traditional approaches, particularly in scenarios with nonlinear treatment effects and complex interference structures. This advance significantly improves causal effect estimation in complex systems, especially in settings lacking complete network information.

TTE Estimation#

Estimating the Total Treatment Effect (TTE) in the presence of complex interference is a significant challenge in causal inference. The paper tackles this by introducing Higher-Order Causal Message Passing (HO-CMP), a novel approach that leverages higher-order moments of observed outcomes to learn the system’s dynamics over time. Unlike methods reliant on known network structures, HO-CMP works with unknown interference. It constructs non-linear features from the data’s moments, enabling efficient data use. The efficacy of HO-CMP is demonstrated across various simulated scenarios and real-world network data, outperforming benchmark methods, showcasing its robustness to non-monotonic interference. The method’s ability to utilize off-equilibrium data and efficiently estimate TTE even with limited observations is a key advantage. While the framework requires multiple time-point data, this limitation is offset by the significant improvement in TTE estimation accuracy, especially in complex, real-world scenarios.

Network Interference#

Network interference, in the context of causal inference, presents a significant challenge to accurately estimating treatment effects. It arises when the treatment of one unit in a network influences the outcomes of other units, violating the fundamental Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA). This interference can manifest in various forms, from direct spillover effects among directly connected units to indirect influences through complex network pathways. The impact of network interference is particularly crucial in social sciences and online platforms where interactions are pervasive and often unobserved. Consequently, standard causal inference methods that assume SUTVA produce biased and inconsistent estimates. Addressing this issue requires sophisticated techniques that either model the network structure explicitly or leverage temporal dynamics of treatment propagation to infer network effects. The success of these advanced methods often hinges on the availability of data rich in spatiotemporal information including repeated measurements of treatment assignment and outcomes across time. Furthermore, the complexity of network interference calls for a careful consideration of the underlying network structure and its effect on treatment effect dynamics. Understanding these intricacies is essential for designing robust experiments and obtaining reliable causal estimates in networked settings.

Experimental Design#

The paper’s experimental design is a critical strength, employing a staggered rollout approach with multiple treatment probabilities. This design allows for the observation of treatment effects over time and under varying treatment intensities, providing richer data than a simple A/B test. The use of both synthetic and real-world network data enhances the generalizability of the findings. However, the reliance on simulations raises concerns about ecological validity; real-world scenarios may present unforeseen complexities. Furthermore, the choice of specific network structures and outcome models introduces a degree of potential bias, although the authors attempt to mitigate this through multiple scenarios. The absence of a clear explanation for the specific choice of treatment probabilities is a weakness, as it limits reproducibility and understanding of the selection process. It is important to note that the staggered rollout introduces temporal dependencies, necessitating careful modeling and analysis to avoid confounding effects.

Limitations of SUTVA#

The Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA) is a cornerstone of causal inference, but its limitations become apparent when analyzing experiments with interference. SUTVA’s core assumptions, that treatment assignment to one unit doesn’t affect others’ outcomes and that every unit has only one potential outcome per treatment level, often fail in real-world scenarios. Network effects, spillovers, and general interference violate the independence of units, creating complex dependencies. The presence of indirect interactions, where one unit’s treatment influences others, directly challenges SUTVA’s validity. For example, in social networks, the impact of an intervention might extend beyond those directly treated, due to peer influence or contagion effects. Similarly, in marketplaces, a promotion’s effect can reach far beyond the targeted customers. Thus, the limitations of SUTVA highlight the need for advanced causal inference methods designed to account for interference and the complexities of real-world treatment dynamics. These methods often require sophisticated modelling techniques or advanced statistical approaches capable of unraveling intricate dependencies and accurately estimating treatment effects in the presence of interference. Ignoring SUTVA’s limitations can lead to severely biased treatment effect estimations. Therefore, researchers need to carefully consider the context and nature of treatment effects when choosing a method to estimate causal impacts.

More visual insights#

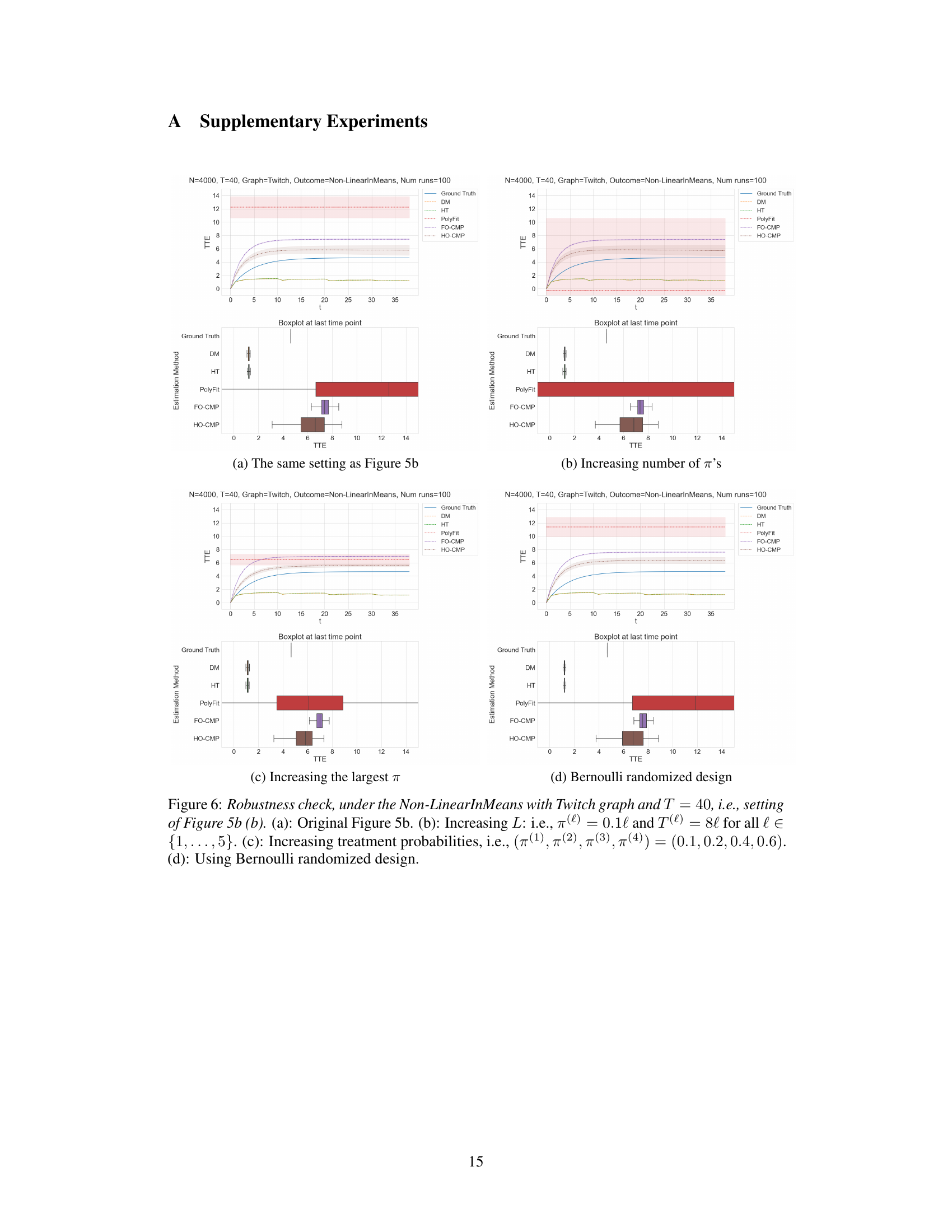

More on figures

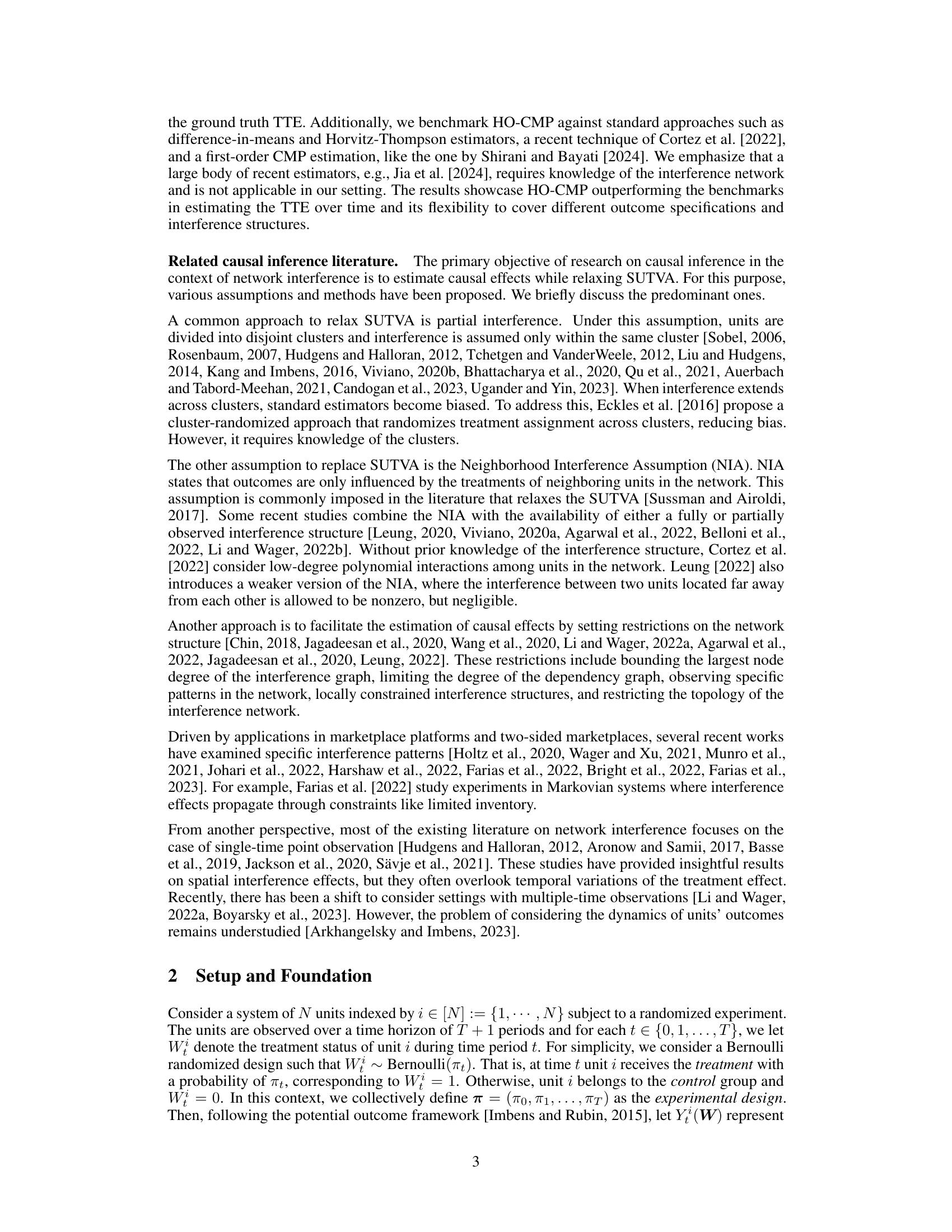

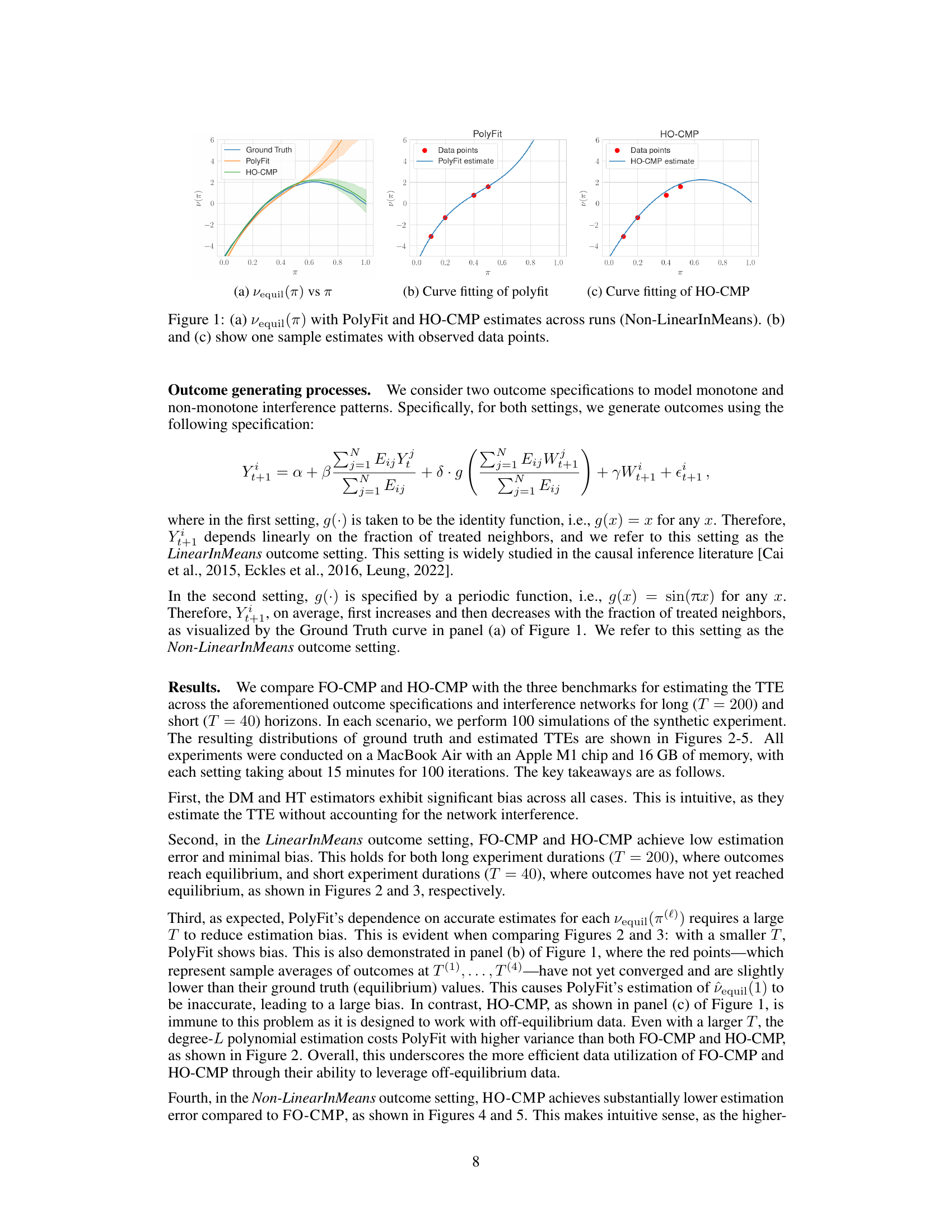

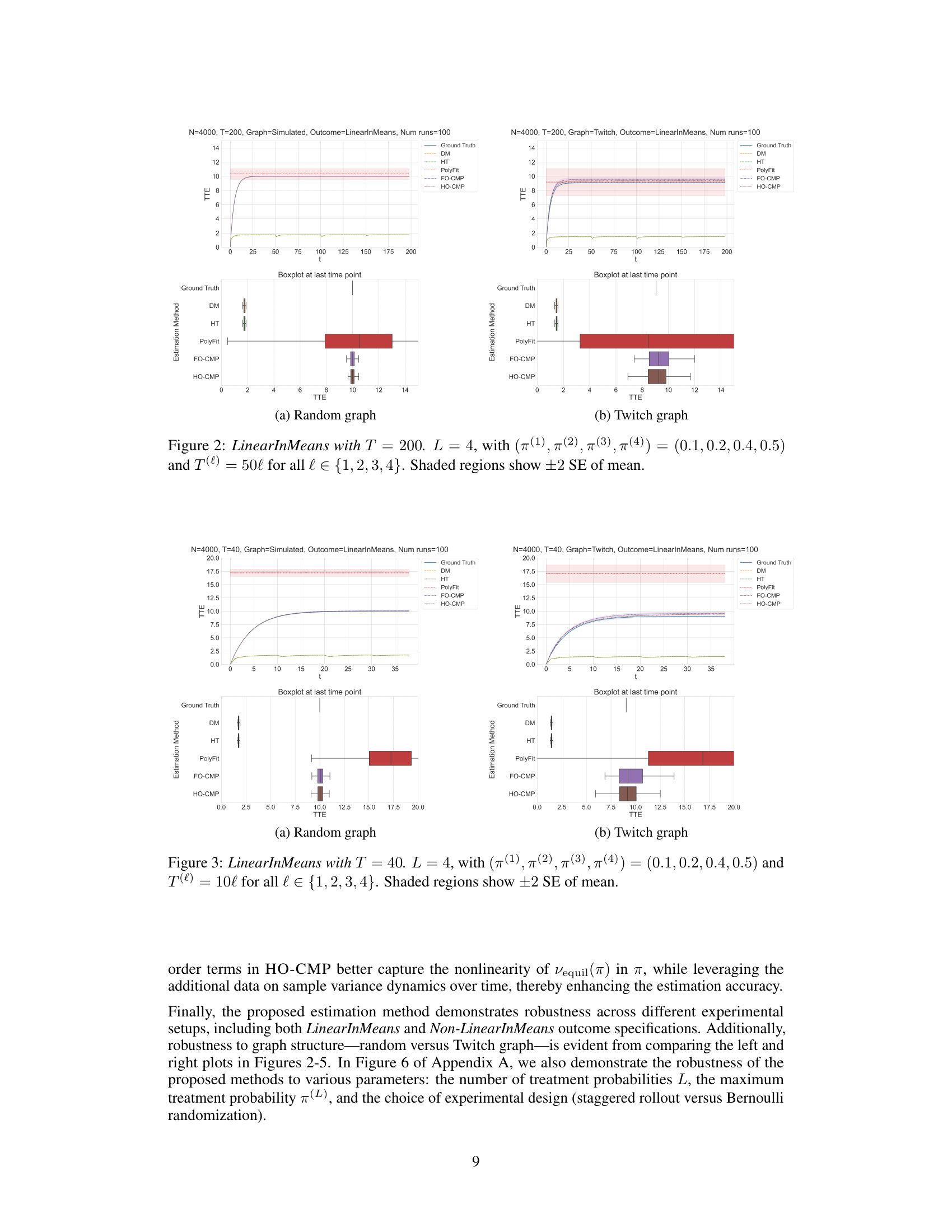

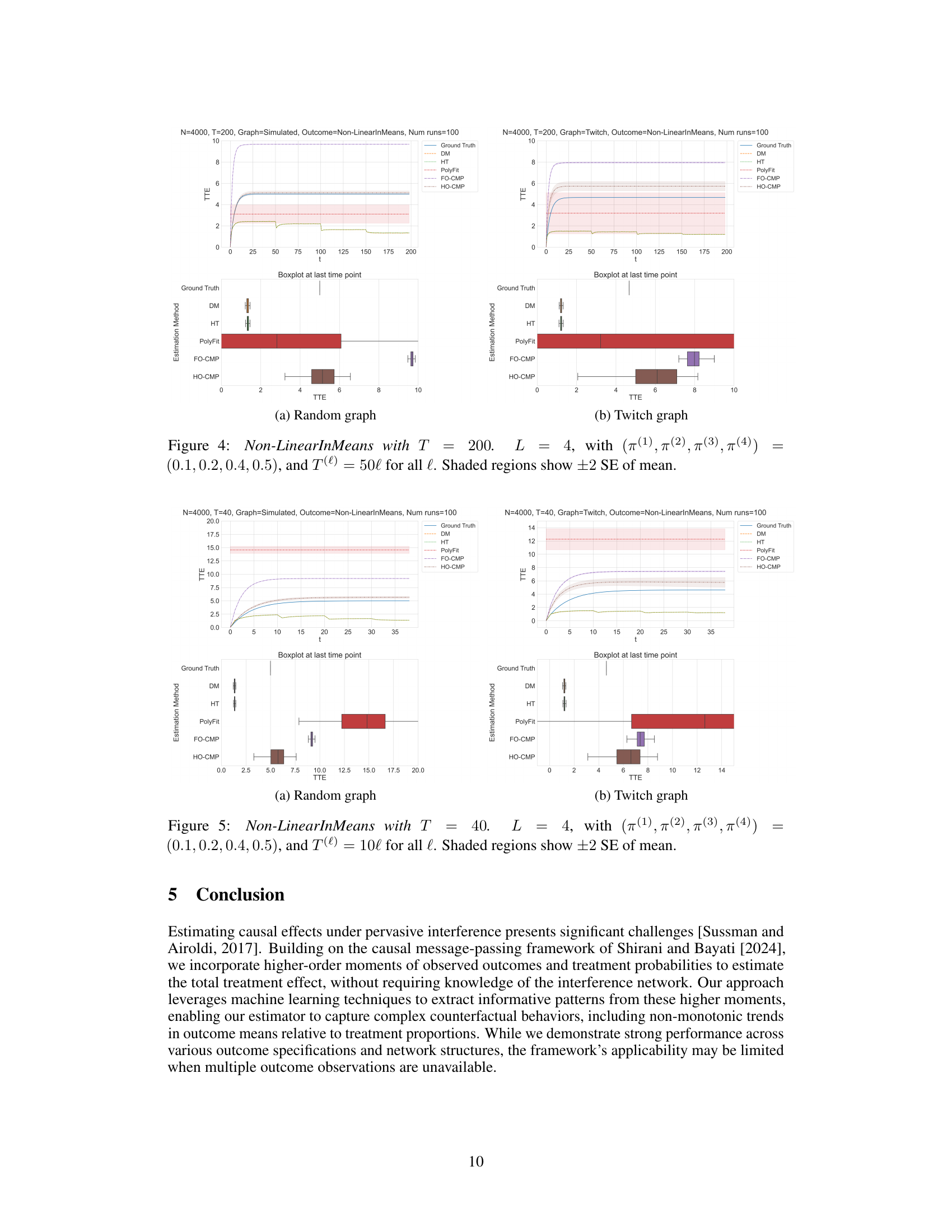

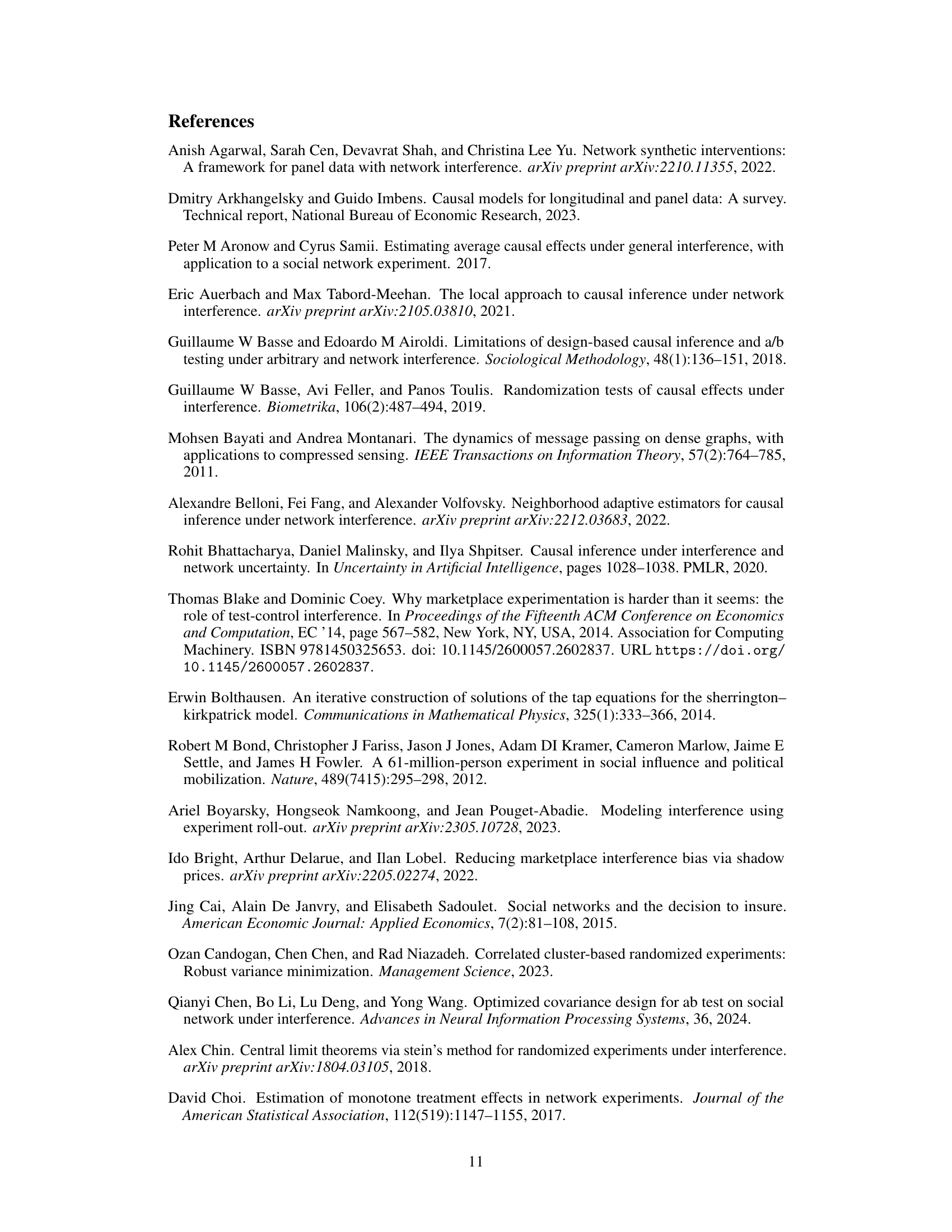

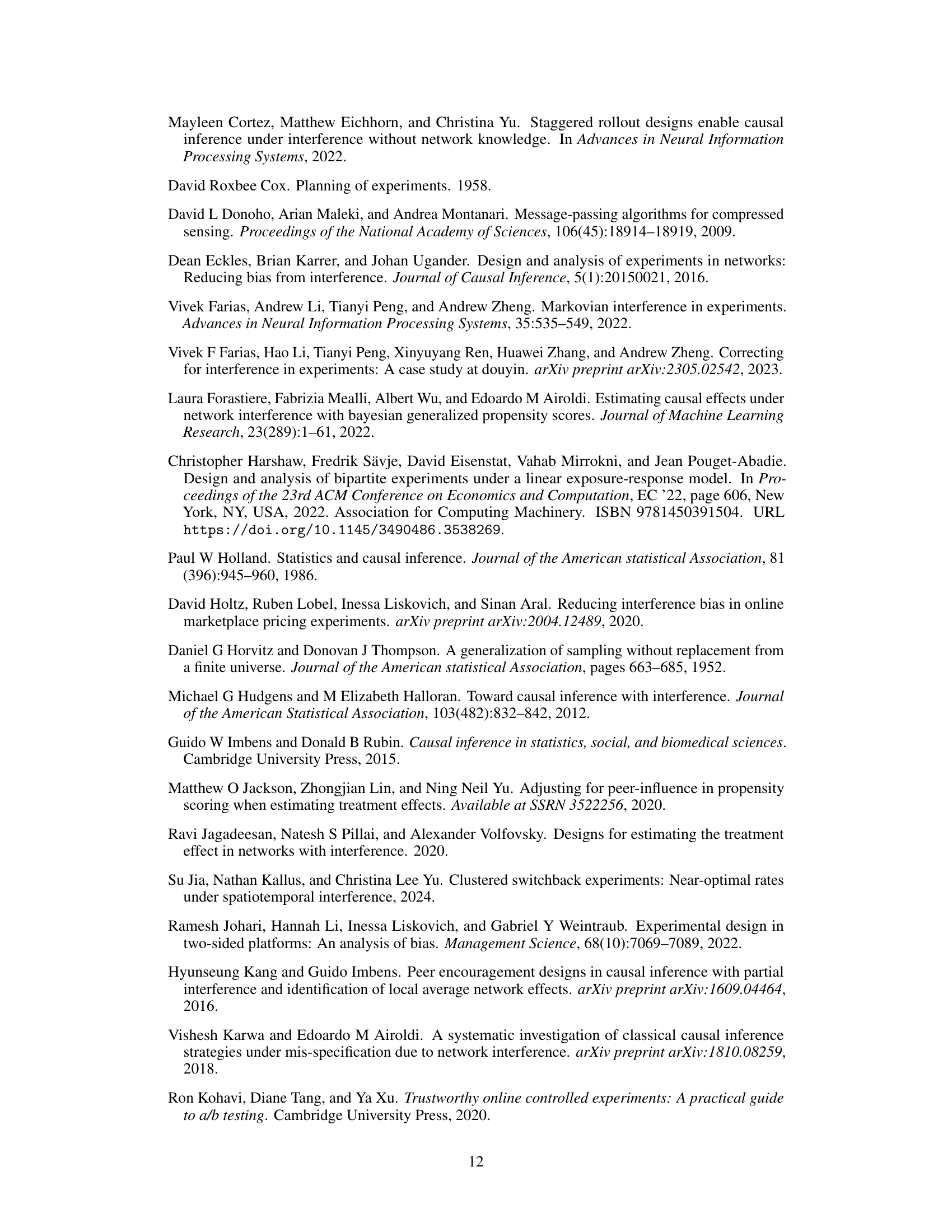

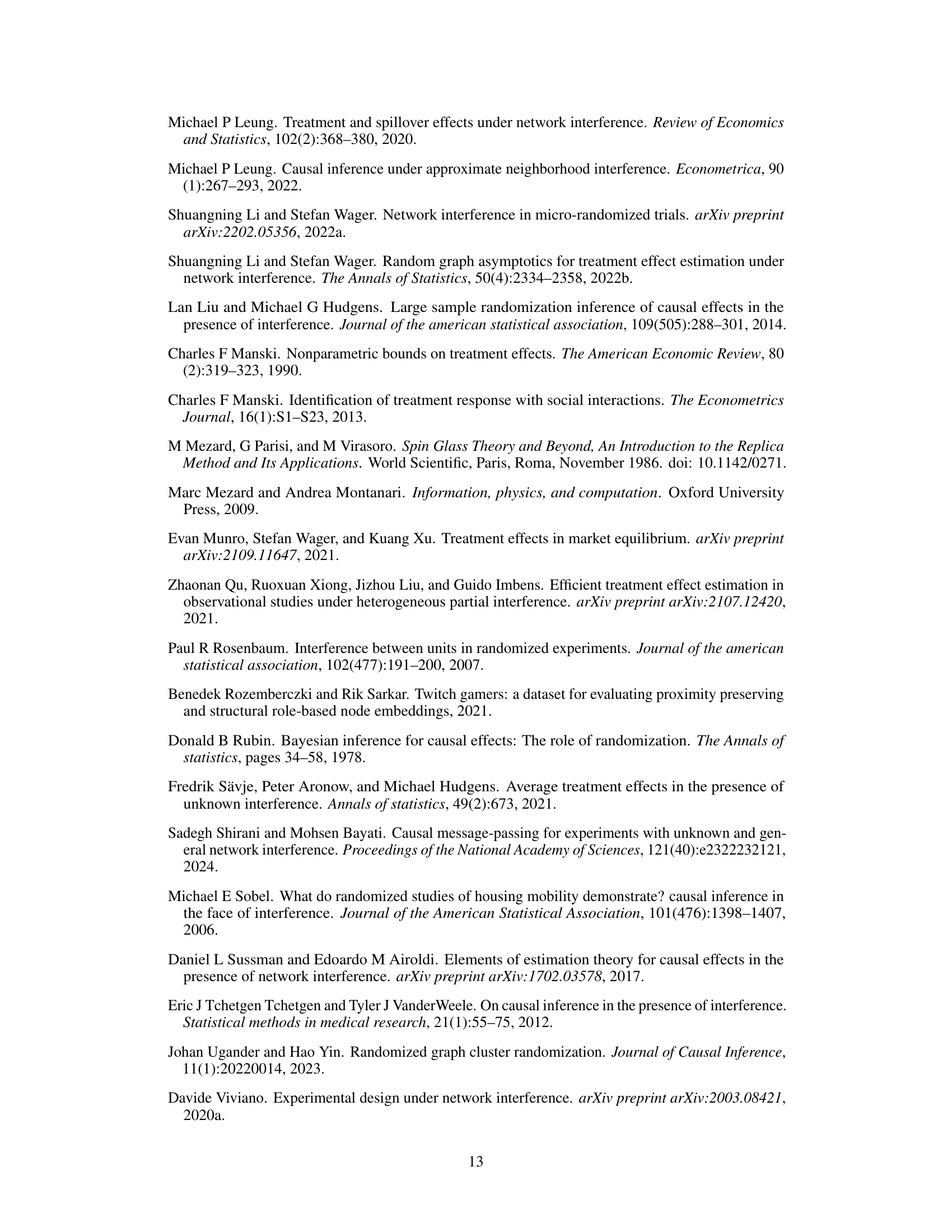

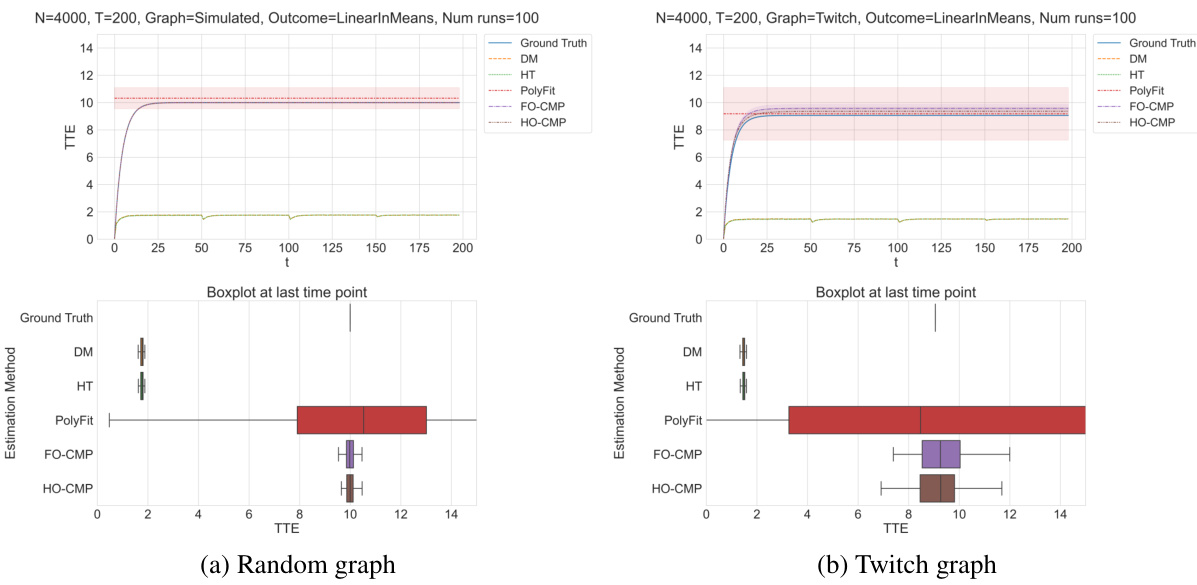

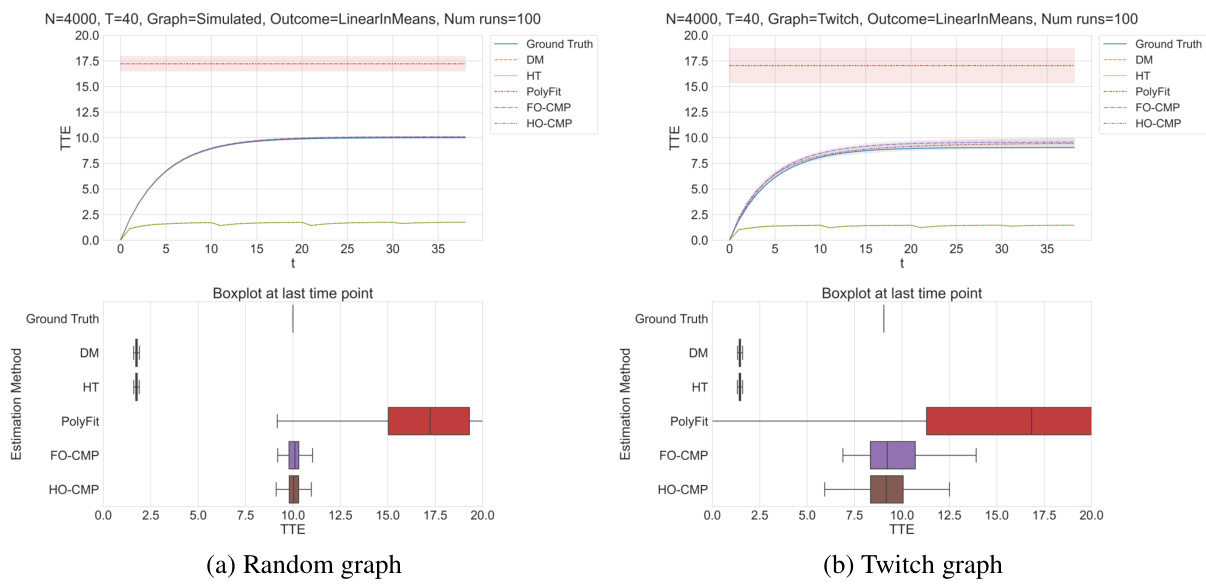

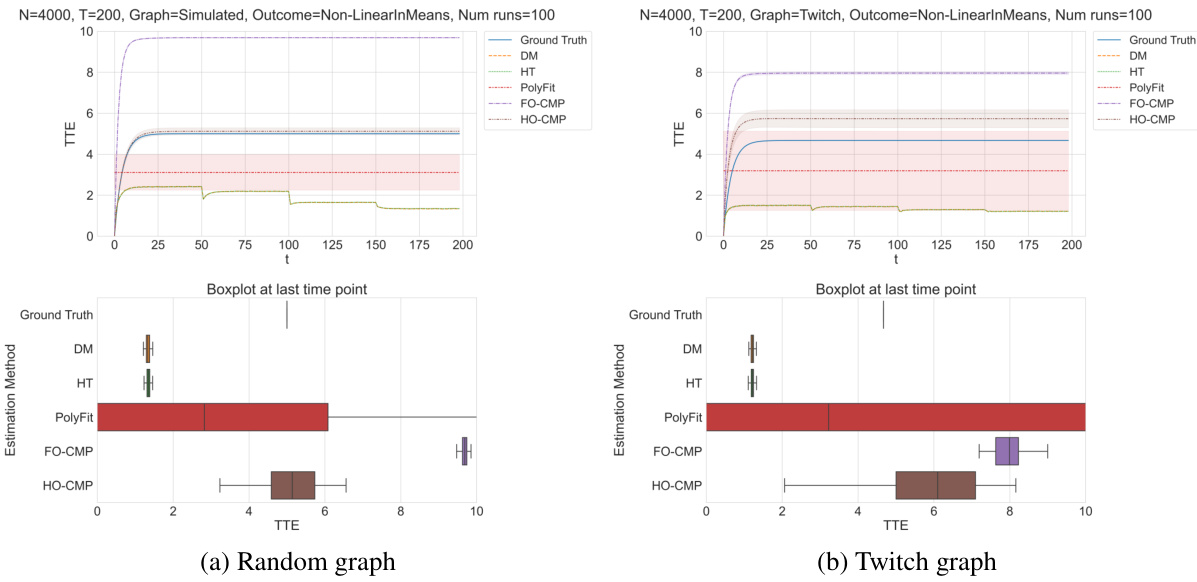

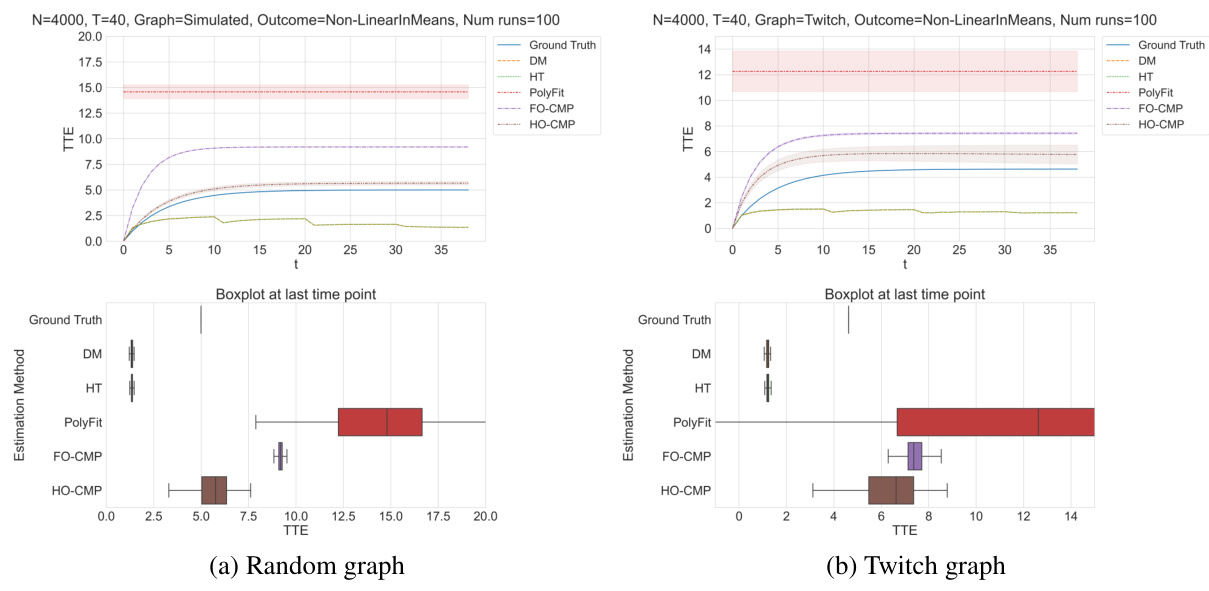

This figure compares the performance of different treatment effect estimation methods (DM, HT, PolyFit, FO-CMP, HO-CMP) against the ground truth in a LinearInMeans setting with T=200, L=4, and specific treatment probabilities. The top panels show the TTE estimations over time for simulated and real-world network data, while the bottom panels provide boxplots summarizing the estimations at the final time point. The shaded regions represent the standard error of the mean.

This figure presents the results of experiments using the LinearInMeans outcome setting with a time horizon of 200 periods. Four distinct treatment probabilities are used, increasing monotonically from 0.1 to 0.5. The duration of each treatment probability phase is 50 times the treatment probability index. The figure compares the performance of several treatment effect estimation methods (DM, HT, PolyFit, FO-CMP, HO-CMP) against the ground truth. Shaded areas represent the standard error of the mean. The figure showcases the results across two different network topologies: a simulated random graph and a real-world Twitch network graph. Boxplots at the last time point summarize the estimation performance across methods.

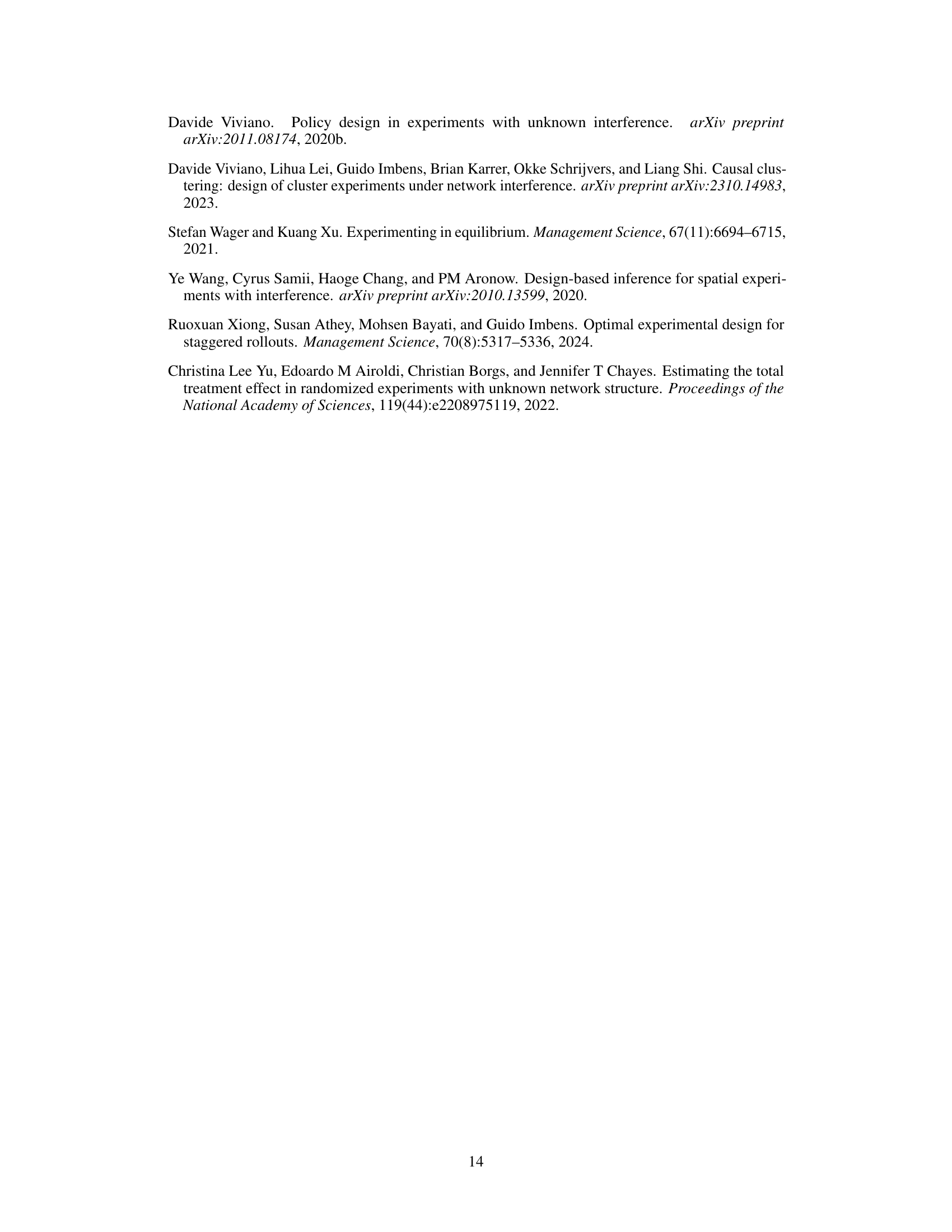

This figure compares the estimated values of Vequil(π) (the average outcome at equilibrium for a given treatment probability π) obtained using PolyFit and HO-CMP methods against the true values. Panel (a) shows the average estimates across multiple simulation runs, while panels (b) and (c) display individual sample estimates along with the observed data points for a single run. The non-linear relationship between Vequil(π) and π highlights the effectiveness of HO-CMP in capturing complex, non-monotonic treatment effects.

This figure compares the ground truth values of Vequil(π) (the average outcome at equilibrium for a given treatment probability π) with the estimates obtained using PolyFit and HO-CMP methods. Panel (a) shows the estimates across multiple simulation runs, while panels (b) and (c) show individual run examples, illustrating the curve fitting of both methods. The Non-LinearInMeans setting implies a non-monotonic relationship between the treatment probability and the average outcome, making this a challenging scenario to estimate.

This figure compares the estimates of Vequil(π) obtained using PolyFit and HO-CMP methods against the ground truth values for the Non-LinearInMeans outcome setting. Panel (a) presents the average estimates from multiple runs, illustrating the performance of each method in approximating the true relationship between Vequil(π) and π. Panels (b) and (c) zoom in on a single run, showing how the fitted curves generated by Polyfit and HO-CMP compare against the observed data points. This visualization helps in understanding the accuracy and efficiency of each estimation technique in capturing the non-linear relationship between the treatment probability (π) and the equilibrium outcome (Vequil(π)).

Full paper#