↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Federated learning (FL) faces challenges from data, model, and task heterogeneity across clients. Existing methods often assume homogeneity, limiting their applicability in real-world scenarios. This restricts the development of heterogeneous FL where clients have diverse data, models, and tasks. This necessitates novel approaches designed to handle the heterogeneity issue effectively.

To address this, the paper proposes FedSAK, a new federated multi-task learning framework. FedSAK uses a flexible architecture where each client model is split into feature extractor and prediction head allowing for flexible shared structures. FedSAK leverages tensor trace norm to effectively mine model low-rank structures and learn correlations among clients. The paper derives theoretical convergence and generalization bounds, demonstrating superior performance against 13 existing FL models on six real-world datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it tackles the critical issue of heterogeneity in federated learning, a major hurdle in real-world applications. It offers a flexible and effective solution that allows for diverse client models and tasks, significantly expanding the applicability of FL. The theoretical analysis and extensive experiments provide strong support for its claims, making it valuable to both theorists and practitioners. This work opens new avenues for research in handling diverse FL scenarios, impacting various areas including personalized medicine and decentralized AI.

Visual Insights#

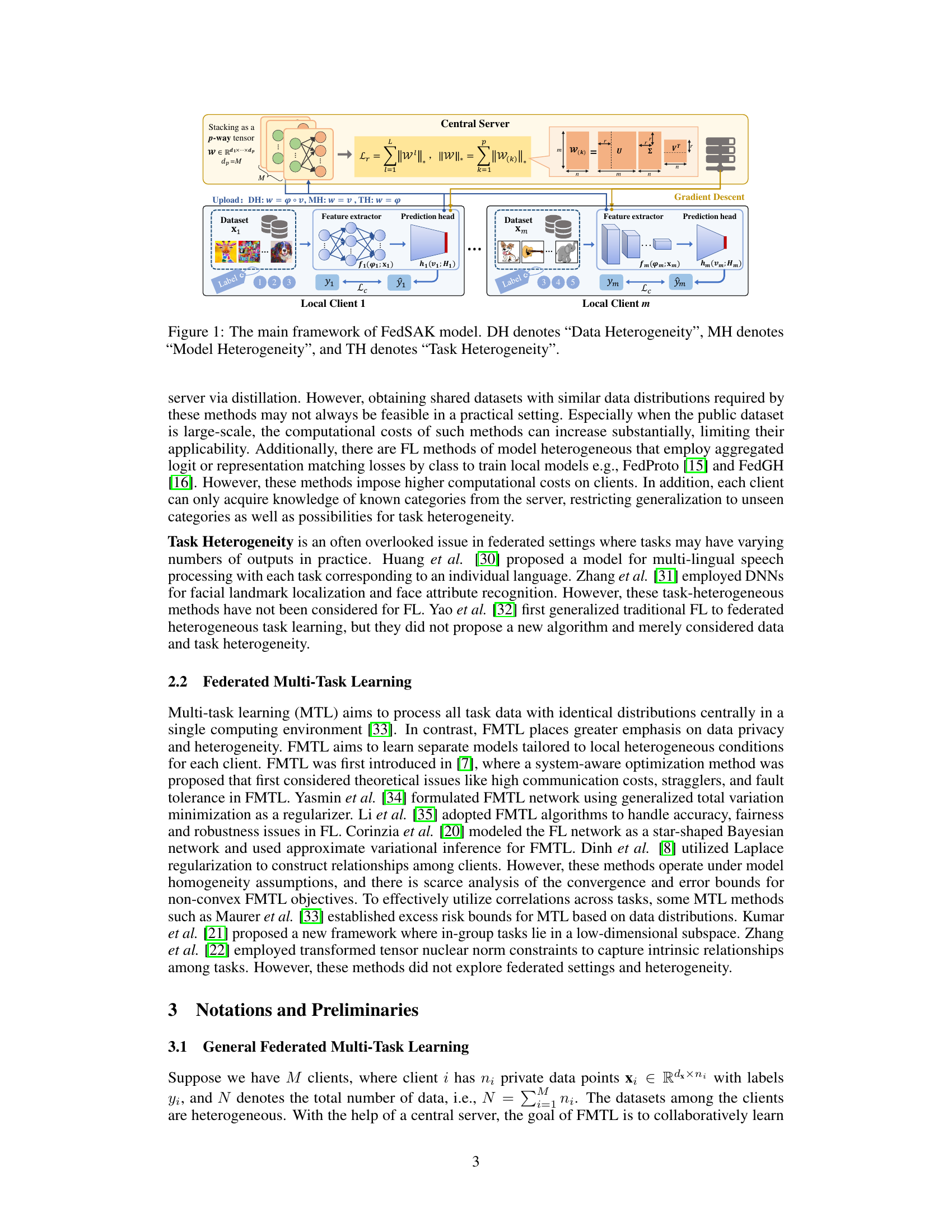

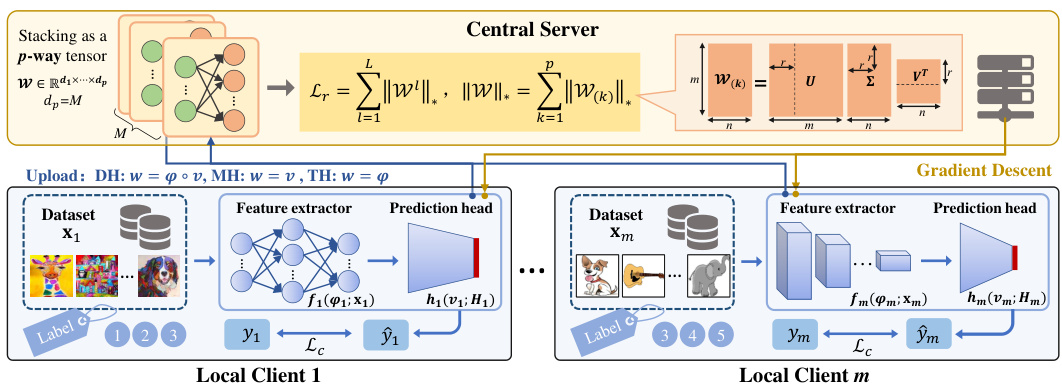

This figure illustrates the architecture of the FedSAK model, which is designed to handle heterogeneous federated learning scenarios. The model consists of multiple local clients and a central server. Each local client has its own dataset and a model composed of a feature extractor and a prediction head. Clients can flexibly choose shared structures based on their specific heterogeneous situations. The clients upload the global shared layers to the server, which learns correlations among client models by mining model low-rank structures through the tensor trace norm. Different heterogeneity types are represented: DH (Data Heterogeneity), MH (Model Heterogeneity), and TH (Task Heterogeneity). The figure shows how the model handles these different types of heterogeneity by adapting its structure.

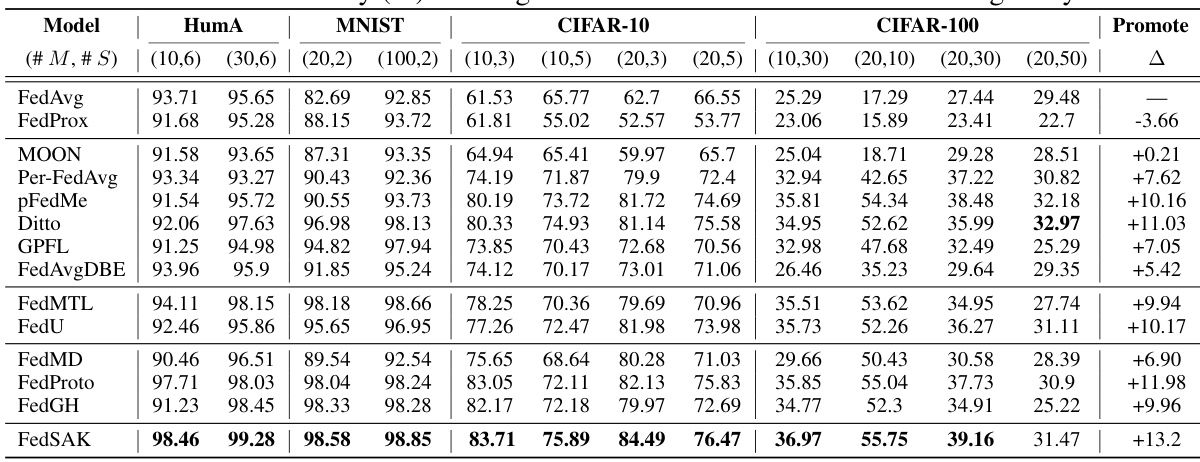

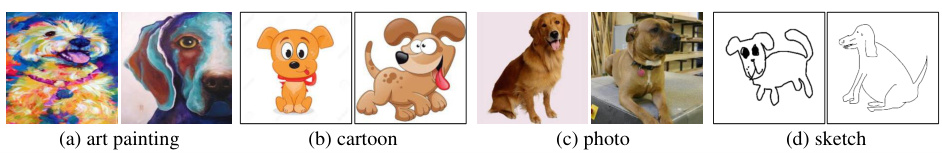

This table presents the results of image classification experiments conducted on six datasets (Human Activity, MNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, PACS, and Adience Faces) under data heterogeneity conditions. It compares the performance of FedSAK against thirteen other federated learning methods across various numbers of clients and label distribution settings. The results show the test accuracy (%) achieved by each method on each dataset, allowing for a comprehensive comparison of their effectiveness in handling data heterogeneity.

In-depth insights#

Heterogeneous FL#

Heterogeneous Federated Learning (FL) presents a significant challenge due to the diversity in client data distributions, model architectures, and learning objectives. This heterogeneity contrasts with the common homogeneity assumption in many FL methods. Addressing this heterogeneity is crucial for real-world applications where devices have varying capabilities and data characteristics. Effective heterogeneous FL strategies need to account for these variations, potentially through personalized models or techniques that learn shared representations across clients while preserving task-specific information. This might involve novel model aggregation techniques that can handle different model structures or regularization methods that encourage low-rank structures in model parameters to facilitate knowledge transfer between clients. The development of robust and efficient solutions for heterogeneous FL is a key area of research, with significant implications for the scalability and applicability of FL.

FedSAK Framework#

The FedSAK framework offers a flexible and robust approach to heterogeneous federated learning by employing a tensor trace norm to capture correlations between client models. Its key strength lies in its ability to handle data, model, and task heterogeneity simultaneously. By decomposing each client’s model into a feature extractor and a prediction head, FedSAK allows for flexible sharing of model components, promoting efficient knowledge transfer while respecting client-specific constraints. The framework’s theoretical foundation, including derived convergence and generalization bounds, provides confidence in its performance. The use of the tensor trace norm is particularly noteworthy, enabling FedSAK to identify and leverage low-rank structures within the aggregated client models, enhancing generalization. This adaptability makes FedSAK a powerful tool for real-world FL deployments where uniformity across clients is often unrealistic.

Trace Norm’s Role#

The trace norm plays a crucial role in the proposed FedSAK framework by facilitating flexible coupling in heterogeneous federated learning. It acts as a regularizer, imposing low-rank structure on the tensor formed by stacking the global shared layers from multiple clients. This low-rank constraint encourages shared representations across clients, enabling knowledge transfer and improving model performance even in the presence of significant data, model, and task heterogeneity. The theoretical analysis demonstrates that the trace norm helps to derive convergence guarantees under non-convex settings, which is a significant contribution considering the complexity of heterogeneous FL. Essentially, the trace norm is the key to unlocking the benefits of multi-task learning in a federated environment, allowing for efficient collaboration and improved generalization despite inherent differences among participating clients.

Convergence & Bounds#

A rigorous analysis of convergence and generalization bounds is crucial for evaluating the robustness and reliability of any machine learning model, especially in complex scenarios like federated learning. The section on ‘Convergence & Bounds’ would ideally delve into the theoretical guarantees of the proposed algorithm. This would involve establishing convergence rates under various conditions, potentially considering non-convex optimization settings. Demonstrating convergence is essential to ensure the algorithm reliably approaches a solution, rather than getting stuck in local optima or diverging. Beyond convergence, the analysis should also cover generalization bounds, which quantify the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data. Tight bounds are desirable as they provide confidence that the model will perform well on new, previously unseen data points. The analysis should clearly state any assumptions made, such as bounds on the data distribution or model complexity, ensuring transparency and reproducibility. Ideally, the bounds should scale gracefully with the number of clients and data points in a federated learning system. The use of techniques like concentration inequalities would be expected to achieve this goal. Strong theoretical results significantly enhance the credibility and impact of the research by providing a solid mathematical foundation for the empirical findings.

Future of FedSAK#

The future of FedSAK hinges on addressing its current limitations and exploring new avenues for improvement. Scalability remains a key challenge; the computational cost of the tensor trace norm increases significantly with the dimensionality of the model parameters. Future work could explore more efficient low-rank approximations or alternative regularization techniques. Generalization to a wider range of heterogeneous settings, beyond the data, model, and task heterogeneity considered in the paper, is crucial. This might involve incorporating advanced techniques like meta-learning or transfer learning to enhance adaptability. Theoretical guarantees could be strengthened by relaxing the assumptions made in the convergence analysis or by developing more robust bounds. Furthermore, exploring the potential of FedSAK in various application domains, such as personalized medicine, smart grids, and autonomous vehicles, would demonstrate its practical impact. Finally, developing user-friendly tools and interfaces that allow non-experts to easily deploy and utilize FedSAK is essential for widespread adoption. Addressing privacy concerns, particularly regarding the aggregation of model parameters on the server, is paramount. Techniques like differential privacy or secure multi-party computation could be integrated to enhance privacy preservation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

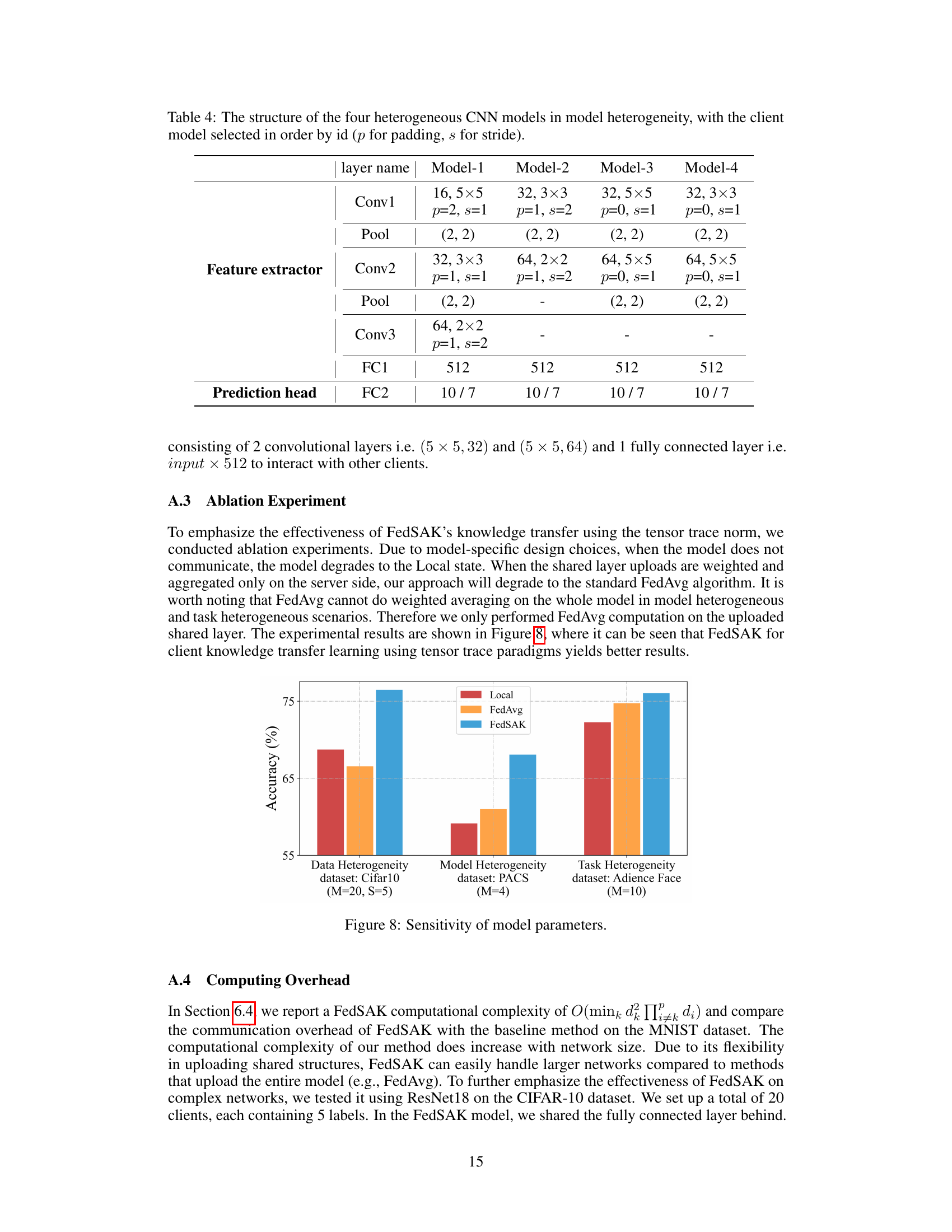

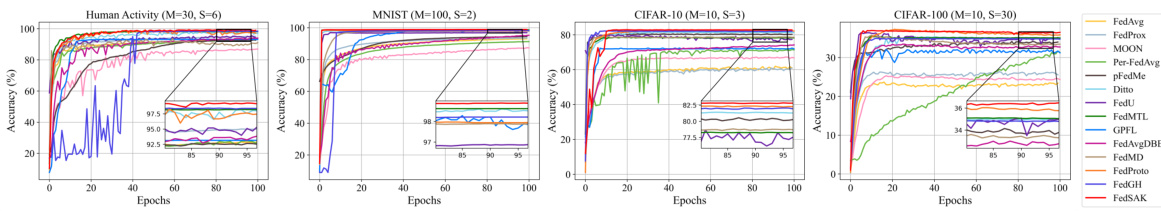

This figure presents the test accuracy and convergence performance of various federated learning (FL) methods across four different datasets: Human Activity, MNIST, CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100. Each dataset represents a different level of complexity and data heterogeneity. The x-axis represents the number of epochs, and the y-axis represents the test accuracy. The figure showcases the relative performance and convergence speed of each method, highlighting the superior performance of FedSAK (in red) in most cases.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the FedSAK model, highlighting its ability to handle data, model, and task heterogeneity in federated learning. The model is split into a feature extractor and a prediction head at each client, allowing for flexibility in model structure. Clients upload their models (or parts thereof) to a central server, which utilizes tensor trace norm to learn correlations among the client models. The figure uses DH, MH, and TH to represent Data, Model, and Task Heterogeneity respectively.

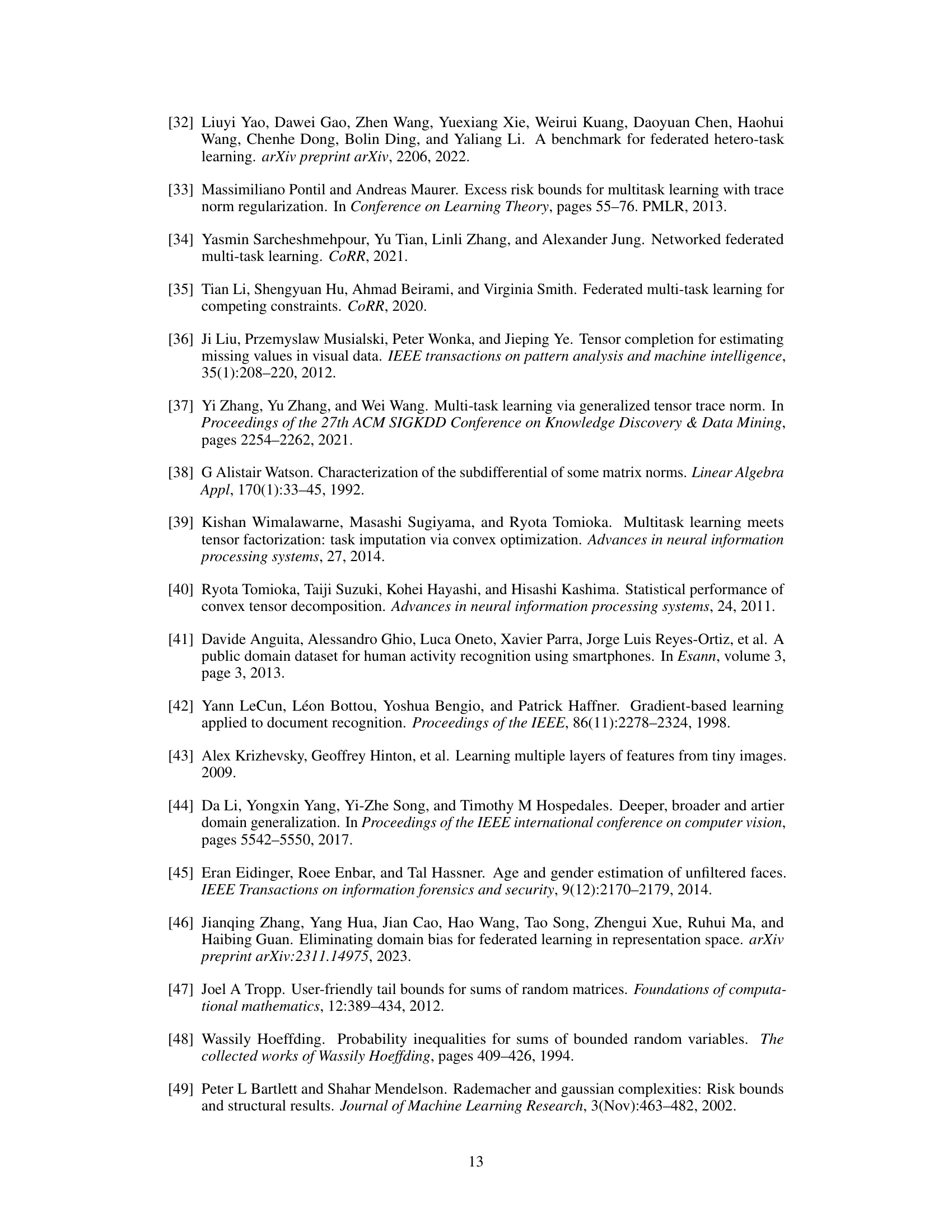

This figure shows the test accuracy of the parameter λ (lambda) in different heterogeneous settings: data heterogeneity (CIFAR-10 dataset with varying numbers of clients and classes), model heterogeneity (PACS dataset with different numbers of clients), and task heterogeneity (Adience Faces dataset with different numbers of clients and tasks). The x-axis represents the value of λ, while the y-axis represents the test accuracy. Each line represents a different experimental setup, illustrating how the optimal λ value varies depending on the type of heterogeneity.

This figure presents the test accuracy and convergence behavior of different federated learning methods across various datasets and heterogeneity scenarios. The x-axis represents the number of epochs (training iterations), and the y-axis shows the test accuracy achieved by each algorithm. Different colored lines represent different algorithms, allowing for a comparison of their performance and convergence speed under the specific settings of each dataset (Human Activity, MNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100). This visualization helps to understand the relative effectiveness of each method in handling data heterogeneity and achieving high accuracy in federated learning.

This figure shows the test accuracy and convergence process of different federated learning methods across various datasets (Human Activity, MNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100). It compares FedSAK’s performance against 13 baseline methods, demonstrating its superior performance and faster convergence in handling data heterogeneity. Each subfigure represents a different dataset, illustrating the training progress over epochs.

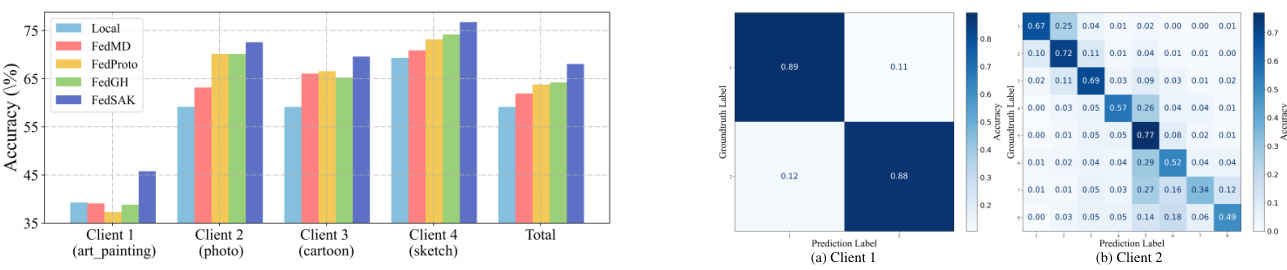

This figure actually contains two figures combined. The first (Figure 3) shows the test accuracy of various federated learning methods under Model Heterogeneity (MH) conditions across several datasets. The second (Figure 4) displays confusion matrices for a task heterogeneity scenario, illustrating the performance of a classifier for two clients on the Adience Face dataset. These matrices showcase the model’s ability to correctly classify different aspects of faces, such as gender and age, across different domains or clients.

The figure illustrates the architecture of the FedSAK model, a federated multi-task learning framework designed to handle data, model, and task heterogeneity. The model is composed of local clients and a central server. Each client has a local dataset and a local model split into a feature extractor and a prediction head. Clients upload their global shared layers (a subset of their model parameters) to the server. The server aggregates these layers, applies a tensor trace norm to mine correlations and low-rank structures, updates the shared layers, and broadcasts them back to the clients. DH, MH, and TH represent the types of heterogeneity addressed by the model.

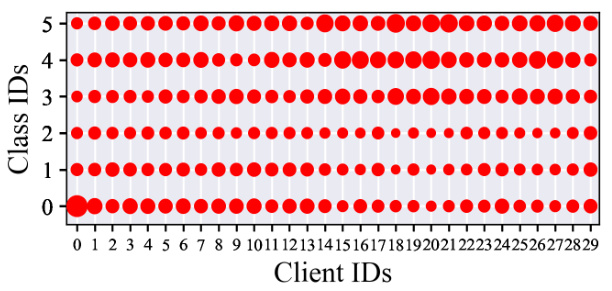

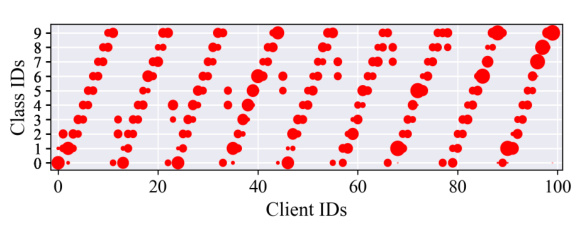

This figure visualizes the data distribution across different clients in the Human Activity dataset. Each client is represented by a column, and each row represents a class ID. The size of the red circle indicates the proportion of data points for that class in the client’s dataset. The visualization helps illustrate the heterogeneity of data distribution among clients, where some clients have more data for specific classes than others.

This figure visualizes the data distribution among 30 clients in the Human Activity dataset. Each client is assigned a subset of the data, and the size of the red circles represents the proportion of data each client has for a given class. It highlights the non-i.i.d. nature of the data distribution, showing that clients do not have the same classes nor the same number of samples per class.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the FedSAK model, a federated multi-task learning framework designed to handle data, model, and task heterogeneity. The model consists of multiple local clients and a central server. Each client has a local dataset and a model divided into two parts: a feature extractor and a prediction head. Clients can customize these components based on their resources and task demands. The clients upload their extracted features to the central server, which aggregates these features and learns correlations between client models using the tensor trace norm. The central server then updates the global shared layers and sends them back to the clients. The figure highlights how the framework addresses different types of heterogeneity: DH (Data Heterogeneity) representing differences in data distribution across clients; MH (Model Heterogeneity) representing differences in model architecture and capacity; and TH (Task Heterogeneity) representing differences in the task objectives of the clients.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the FedSAK model, highlighting its flexibility in handling various types of heterogeneity in federated learning. The model is composed of local clients and a central server. Each client has a local dataset and a model divided into a feature extractor and a prediction head. Clients can upload different parts of their model (feature extractor, prediction head, or both) depending on their resources and the type of heterogeneity present. The server aggregates the uploaded components and learns correlations among client models using the tensor trace norm. The figure also uses abbreviations to represent the different types of heterogeneity addressed by the model: DH (Data Heterogeneity), MH (Model Heterogeneity), and TH (Task Heterogeneity).

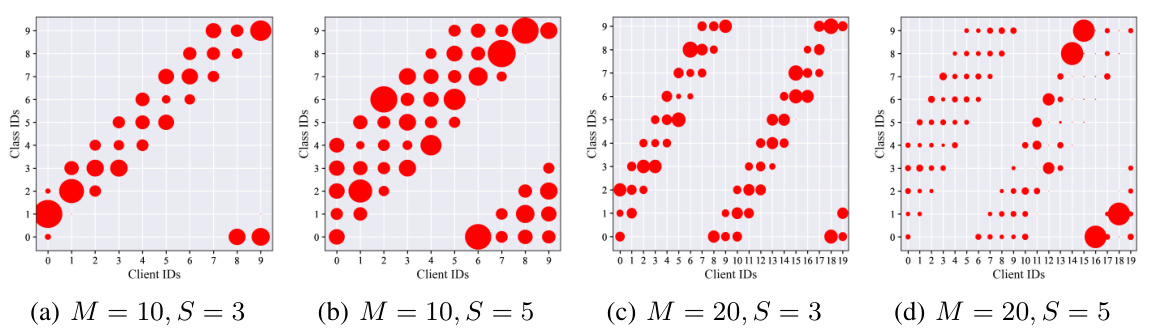

This figure visualizes the data distribution across different clients in the CIFAR-10 dataset. Each small dot represents a data sample, and the size of the dot reflects the number of samples for each class label. The x-axis represents the client ID, and the y-axis represents the class ID. The different subfigures (a, b, c, and d) show the data distribution under varying settings. The distribution is non-IID (non-independent and identically distributed), meaning that the data across clients is not uniform.

The figure illustrates the FedSAK model’s architecture. It shows multiple clients (local clients 1 to m), each with its dataset (X1 to Xm) and labels (Y1 to Ym). Each client model is split into a feature extractor and a prediction head, allowing for flexible model structures depending on the specific client and its data characteristics. The clients upload their model parameters (w) to a central server, which aggregates and processes the information using a tensor trace norm to identify relationships between client models and create a low-rank structure, representing intrinsic correlations among clients. The server then sends back updated global shared layers to each client to facilitate model training and knowledge transfer. The figure highlights the model’s ability to handle Data, Model, and Task Heterogeneity (DH, MH, TH).

More on tables

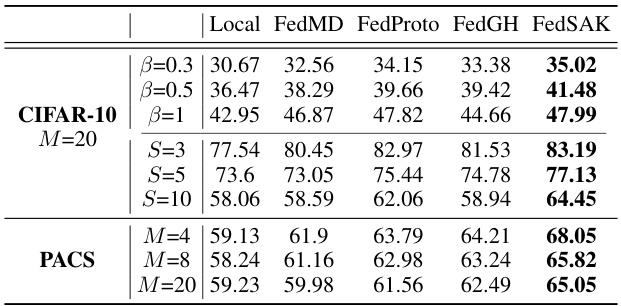

This table presents the test accuracy results of different federated learning methods on image classification tasks under model heterogeneity. It shows the performance of various methods (Local, FedMD, FedProto, FedGH, and FedSAK) across different settings. The settings vary the Dirichlet distribution parameter (β), the number of labels (S), and the number of clients (M) to evaluate performance under varying levels of data and model heterogeneity.

This table presents the results of the Adience Faces experiment, focusing on task heterogeneity. It compares the test accuracy of three different methods: Local (no federated learning), FedAvg-c (a baseline federated averaging method where only the feature extractor is uploaded), and FedSAK. The results are broken down by the number of clients (M), the ratio of gender classification tasks to age classification tasks (1:1, 1:2, 2:1), and the specific task (Gender, Age). The numbers in parentheses show the percentage improvement of each federated learning method compared to the Local method.

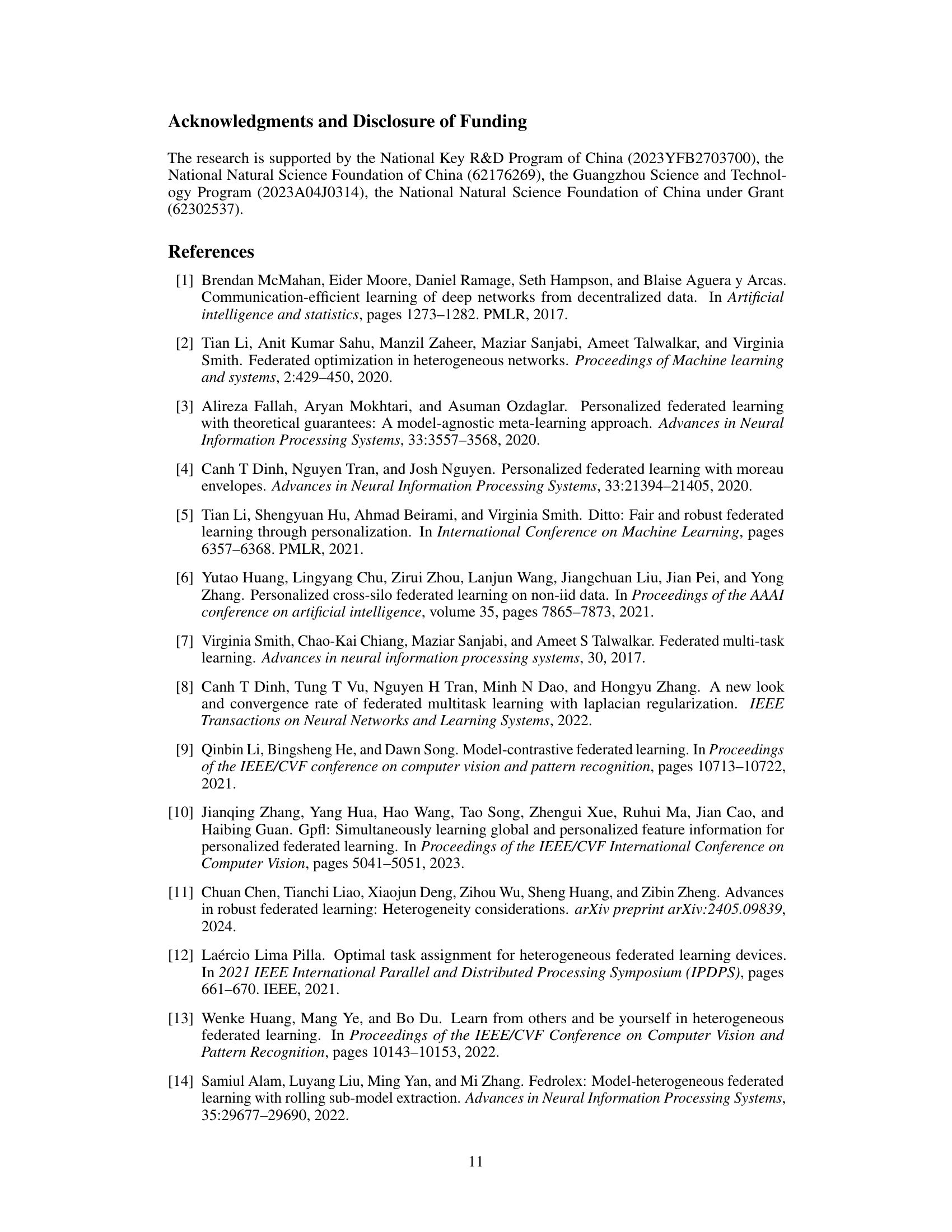

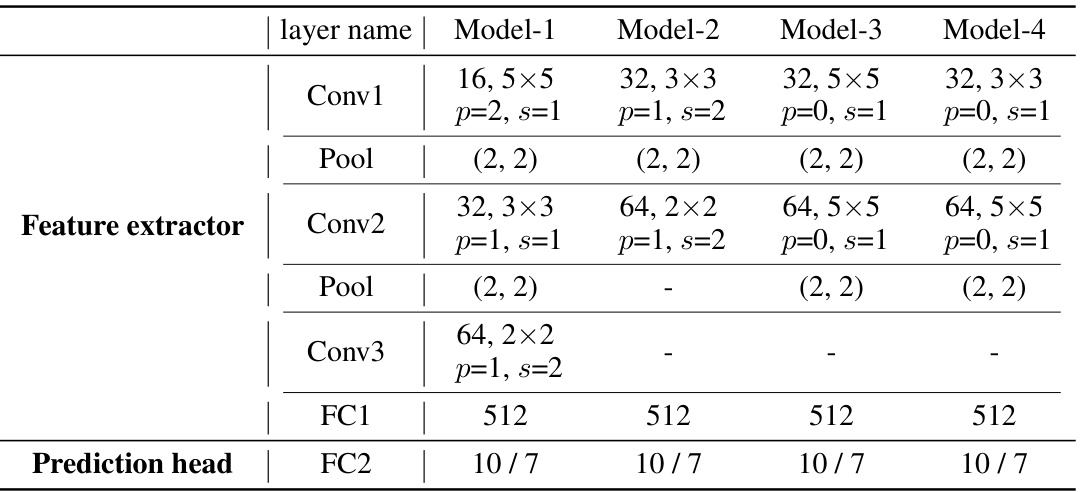

This table details the architecture of four different CNN models used in the model heterogeneity experiments. Each model varies in the number of filters, kernel size, padding, and stride in the convolutional layers. The table shows how these parameters differ across the four models, while keeping the fully connected layers consistent. This variation allows for the testing of model heterogeneity in the federated learning setting.

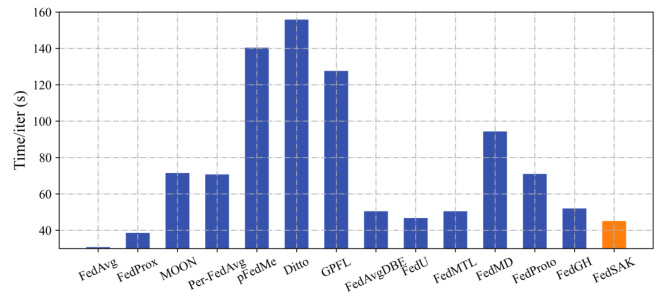

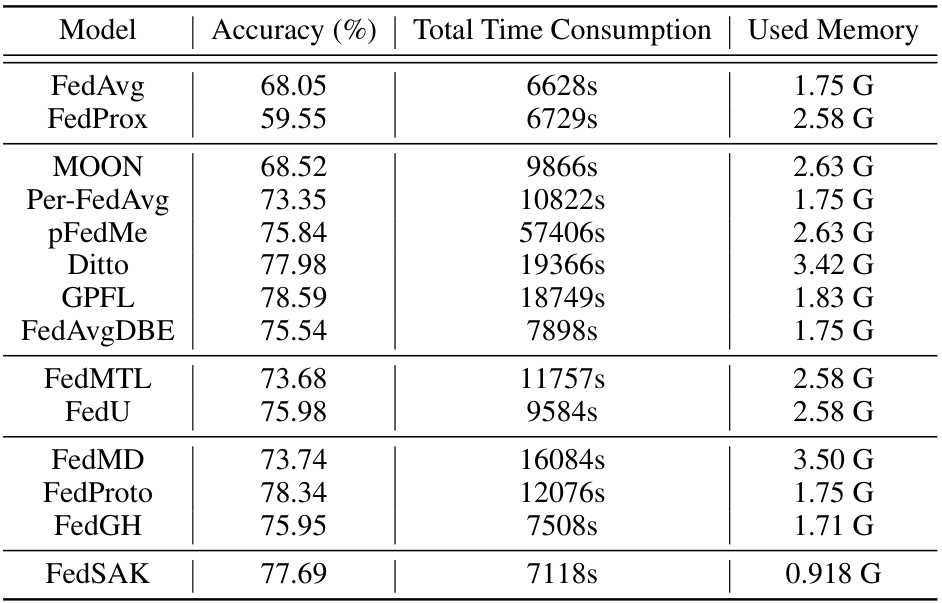

This table presents a comparison of different federated learning methods using ResNet18 on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It shows the accuracy achieved by each method, the total time taken for the training process, and the amount of memory used. The results highlight the trade-offs between accuracy, computational cost, and memory requirements for various approaches to federated learning.

Full paper#