↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Graph diffusion equations (GDEs) are essential for various graph-related tasks, but standard iterative methods are computationally expensive for large graphs. Existing local solvers offer improvements but suffer from limitations such as sequential operation and limited applicability. This research addresses these issues.

The paper presents a novel framework for approximately solving GDEs using a local diffusion process. This framework effectively localizes standard iterative solvers via simple, provably sublinear time algorithms suitable for GPU implementation. The approach demonstrates significant speed improvements and applicability to large-scale dynamic graphs, also paving the way for more efficient local message-passing mechanisms in Graph Neural Networks (GNNs).

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large-scale graphs because it offers significantly faster methods for solving graph diffusion equations. This improvement translates to faster GNN training and opens up new avenues for research in large-scale graph analysis and machine learning applications. The framework’s generality and parallelizability make it readily applicable to diverse problems. Its theoretical contributions and empirical results provide a strong foundation for future research.

Visual Insights#

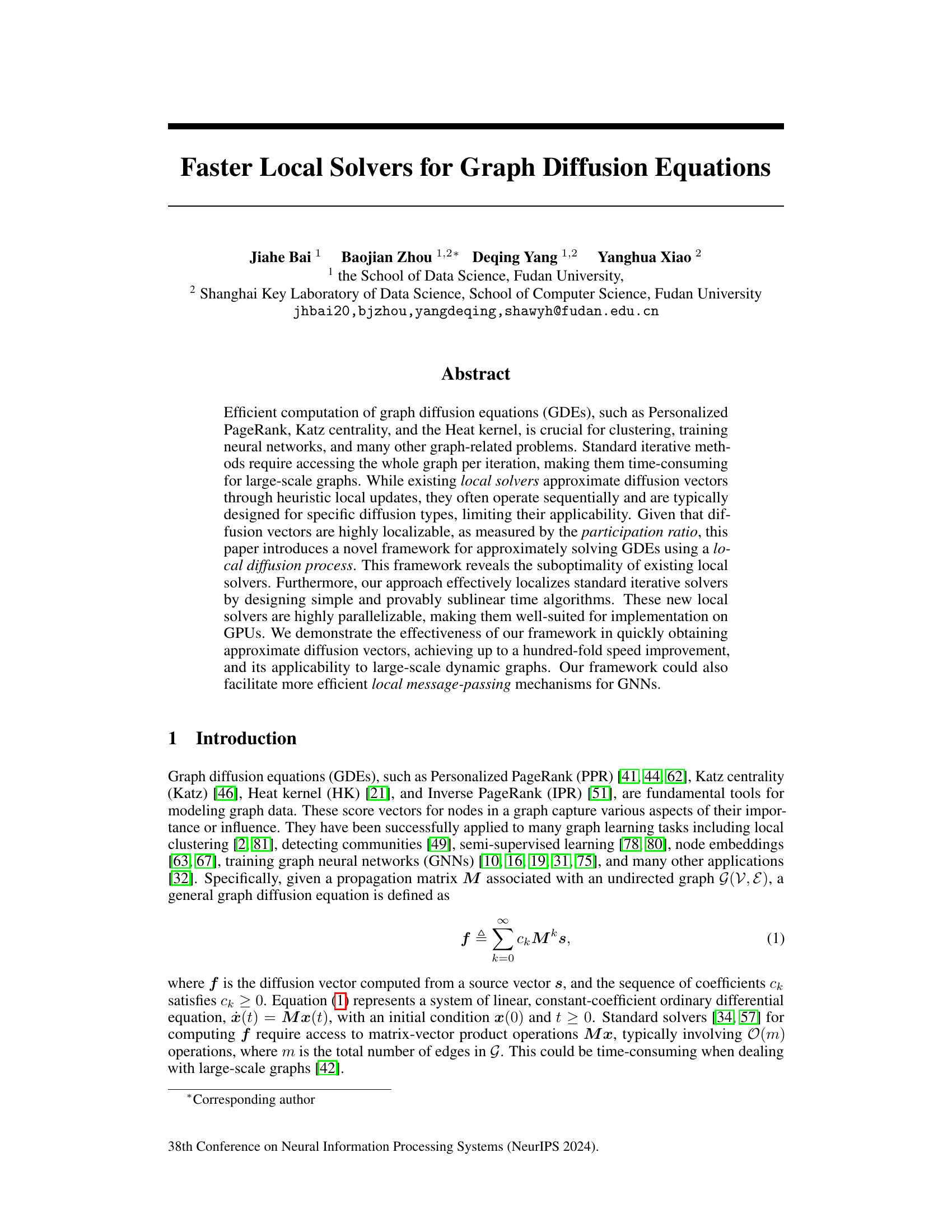

This figure demonstrates the localization property of diffusion vectors for PPR, Katz, and HK. The maximal participation ratio (p(f)), a measure of how concentrated the non-zero values of a vector are, is plotted against the graph index (ordered by graph size). Lower values of p(f) indicate higher localization, meaning the significant values of the diffusion vector are concentrated in a small portion of the graph. The figure shows that for these common graph diffusion equations, the diffusion vectors are indeed highly localized, a key property leveraged by the proposed framework for efficient computation.

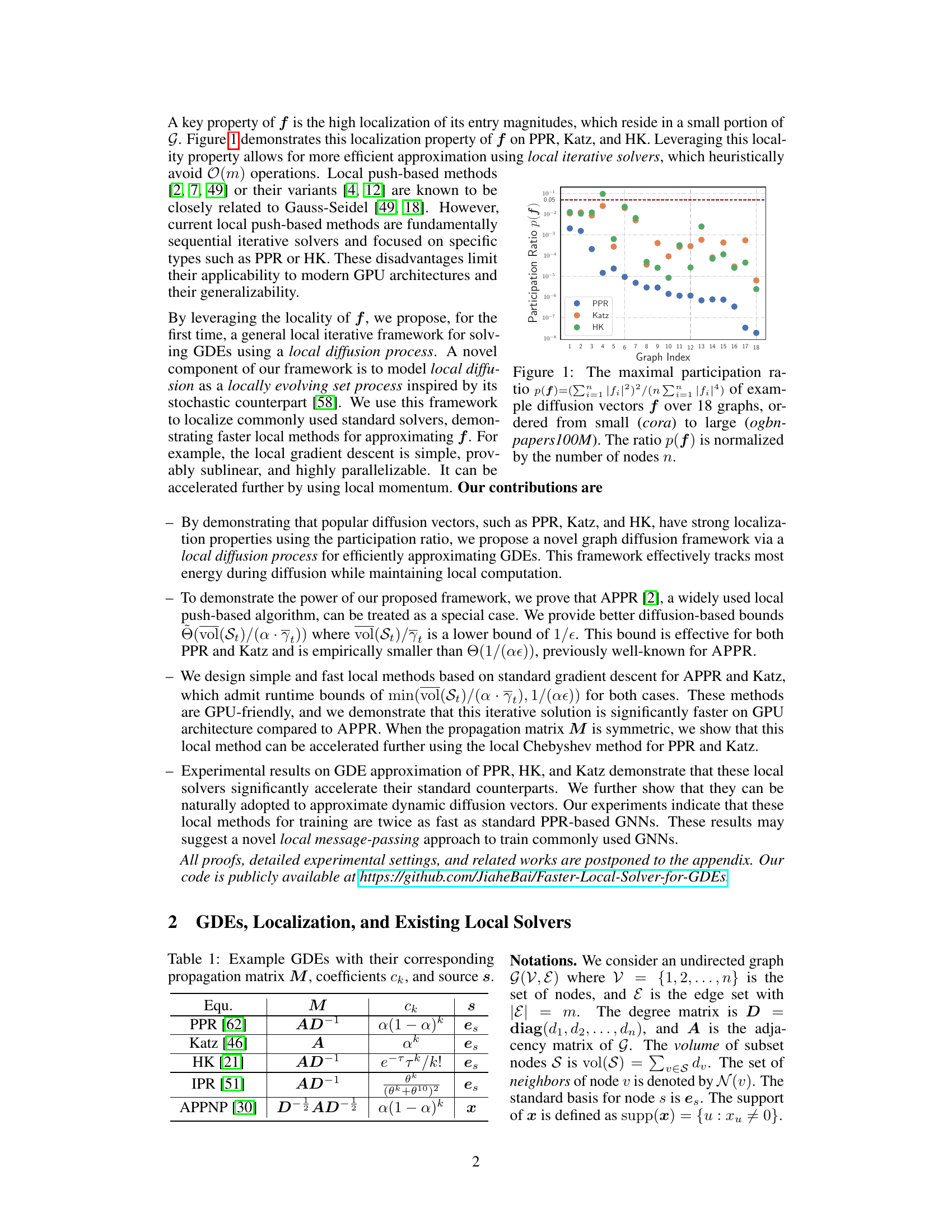

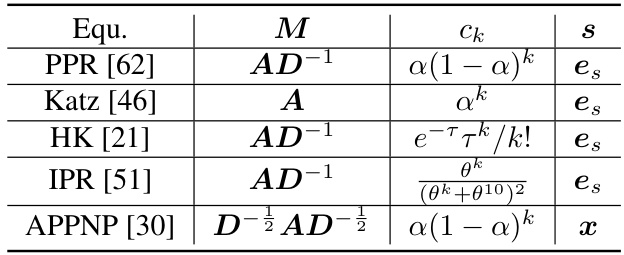

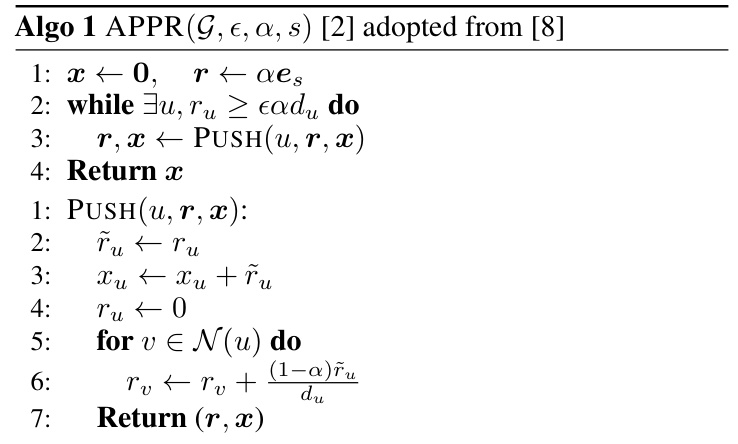

This table lists several examples of Graph Diffusion Equations (GDEs), including their corresponding propagation matrix (M), the sequence of coefficients (ck) that determines the weight of each diffusion step, and the source vector (s) that initiates the diffusion process. The GDEs listed are Personalized PageRank (PPR), Katz centrality (Katz), Heat kernel (HK), Inverse PageRank (IPR), and APPNP.

In-depth insights#

Local GDE Solving#

Local GDE solving tackles the computational challenge of graph diffusion equations (GDEs) on large-scale graphs by focusing on local computations. Instead of processing the entire graph at each iteration, it leverages the locality property of GDE solutions, which implies that the influence of a node typically decays rapidly with distance. This allows for substantial speedups, particularly beneficial in dynamic graph scenarios where recomputation from scratch is inefficient. Approaches such as local push-based methods have been explored but are often heuristic, sequentially-oriented, or limited to specific diffusion types. The proposed framework for local GDE solving offers a more systematic approach. It involves iterative methods where local updates to diffusion vectors are based on a localized neighborhood, enabling GPU-friendly parallelization and significant improvements over traditional global methods. Novel algorithmic designs, such as local gradient descent and local successive overrelaxation, along with runtime complexity analysis, demonstrate the effectiveness of the approach. The framework also opens possibilities for more efficient local message-passing mechanisms in graph neural networks.

GPU-Friendly Solvers#

The concept of “GPU-Friendly Solvers” for graph diffusion equations is crucial for scalability. Parallel processing capabilities of GPUs are ideally suited to the iterative nature of many diffusion algorithms. The paper likely explores how to leverage GPU architecture for faster computation by designing solvers that can efficiently utilize parallel processing. This might involve breaking down the problem into smaller, independent tasks that can be assigned to different GPU cores, perhaps through techniques like data partitioning, algorithmic restructuring, and optimized memory access patterns. Efficient parallelization strategies are vital for large-scale graphs where traditional CPU-based methods become computationally prohibitive. The discussion would likely include comparisons of performance metrics between CPU and GPU implementations, showing the significant speedups attainable through GPU acceleration. The choice of data structures and algorithms tailored for GPU hardware is also a critical component. The paper will likely analyze the tradeoffs between different GPU-friendly approaches, considering factors such as communication overhead and memory bandwidth. The potential for future work would involve exploring further optimization techniques to reduce memory usage and improve parallel efficiency further.

Dynamic GDEs#

The section on “Dynamic GDEs” would explore how the framework handles evolving graph structures. It would likely discuss adapting the local solvers to efficiently update diffusion vectors as edges are added or removed, highlighting the computational advantages over recomputing from scratch. The authors might present algorithms for incremental updates, perhaps leveraging existing techniques for dynamic graph processing. A key aspect would be to show that the framework maintains its speed and accuracy benefits in dynamic settings. Benchmarking against alternative methods for handling dynamic GDEs would provide a strong evaluation of the proposed approach’s performance and scalability. The authors should show that the localization strategy continues to be effective in capturing the important information despite changes to graph topology and that the dynamic updates are significantly faster than recalculating solutions from a static perspective. Furthermore, the extension to dynamic GDEs strengthens the applicability of the local diffusion process by addressing a critical real-world concern, where graphs are rarely static.

Sublinear Time Bounds#

The concept of “Sublinear Time Bounds” in the context of a graph diffusion equation solver is crucial for handling massive graphs. Algorithms achieving sublinear time complexity offer a significant advantage over traditional linear-time methods by reducing the computational cost as the graph size grows. The paper likely demonstrates sublinear bounds for their proposed local solvers by analyzing their computational operations per iteration. These analyses would focus on showing that the number of operations required scales sublinearly (e.g., O(√n) or O(log n)) with respect to the number of nodes (n) or edges (m) in the graph. This efficiency arises from the localization strategy, which focuses computations on a small neighborhood of nodes, rather than the entire graph, in each step. The theoretical analysis underpinning the sublinear bounds probably involves sophisticated mathematical techniques to derive upper bounds on the runtime complexity, likely leveraging properties of graph structure and the nature of the diffusion process itself. Proofs would be essential to rigorously establish the claims and ensure the validity of the sublinear time bounds.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the local diffusion framework to other types of GDEs beyond PPR and Katz is a key area. Investigating the theoretical properties of LocalSOR and LocalCH, particularly proving accelerated convergence bounds without the monotonicity assumption, would strengthen the theoretical foundation. Developing faster local methods under high-precision settings (small epsilon) remains a challenge. Furthermore, applying the local diffusion framework to other graph learning tasks, such as community detection and node classification, should be explored. Finally, integrating the local solvers into more sophisticated GNN training and message-passing mechanisms presents a significant opportunity for improving GNN scalability and efficiency. The potential benefits are numerous, suggesting rich research possibilities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

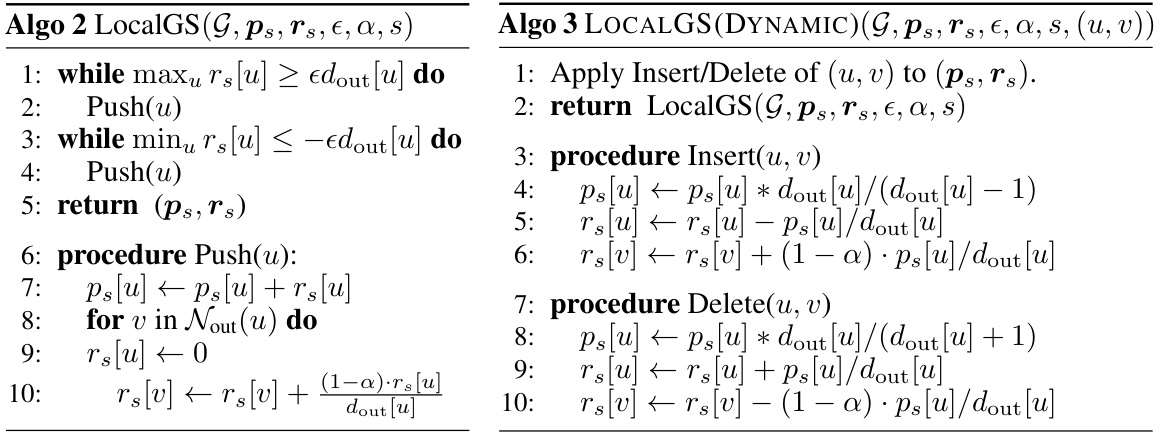

This figure compares the local diffusion processes of APPR and LocalSOR on a small graph. APPR (top row) takes more iterations and operations to achieve a similar level of accuracy compared to LocalSOR (bottom row). This illustrates the efficiency gains of LocalSOR.

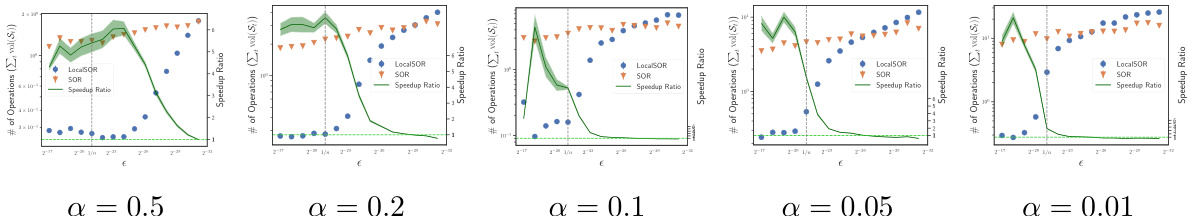

This figure shows the number of operations required for LocalSOR and LocalGS as a function of the relaxation parameter ω for PPR calculations on the wiki-talk dataset. The shaded area represents the standard deviation across multiple runs. The dashed line indicates the average number of operations for LocalGS. The optimal ω value for LocalSOR is approximately 1.19, resulting in a significant reduction in the number of operations compared to LocalGS.

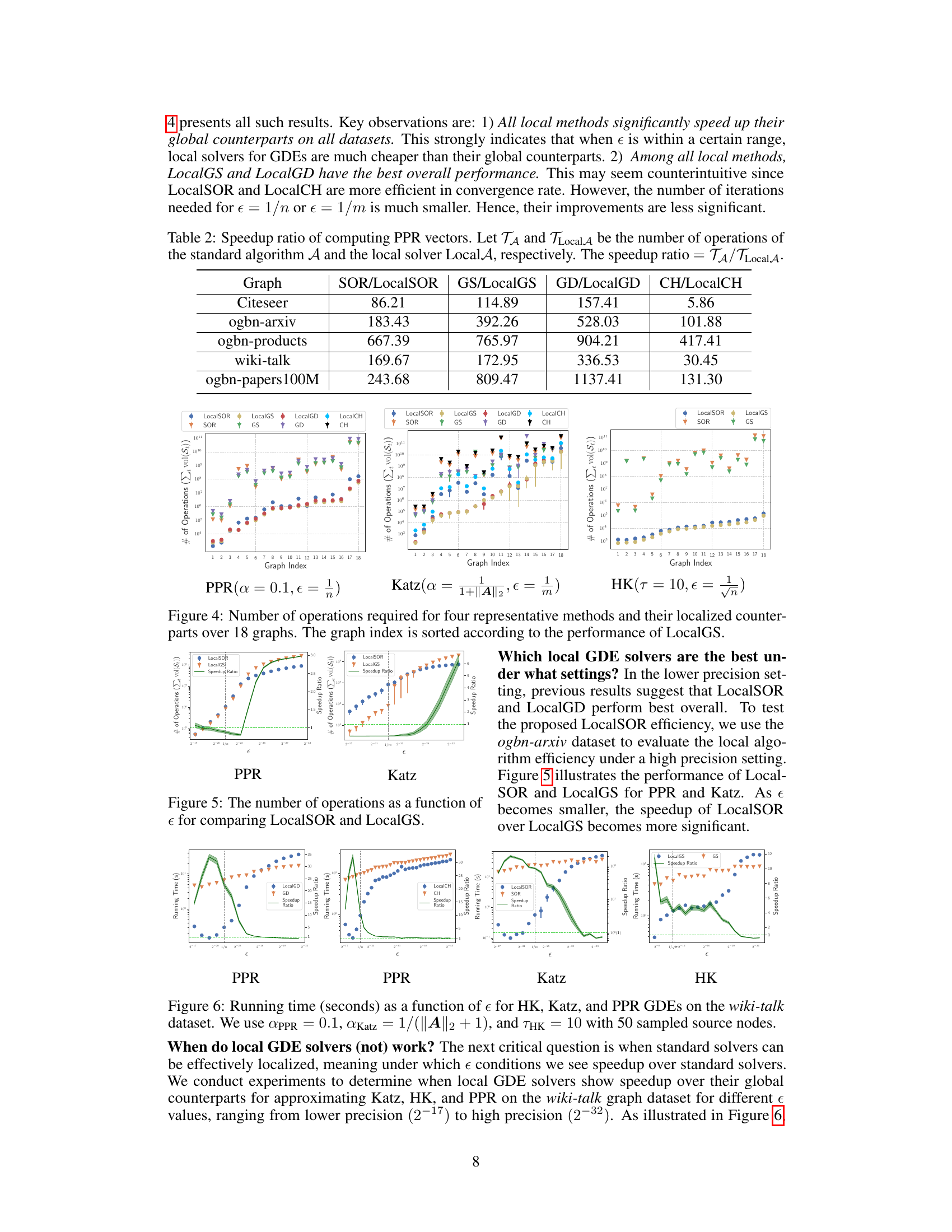

This figure compares the number of operations required by four global methods (GS, SOR, GD, CH) and their corresponding local versions (LocalGS, LocalSOR, LocalGD, LocalCH) for approximating graph diffusion vectors on 18 different graphs. The x-axis represents the graph index, ordered by the performance of LocalGS, which means the first graph is the one where LocalGS performs best, while the last graph is the one where LocalGS performs worst. The y-axis represents the number of operations, shown in logarithmic scale. The figure demonstrates that all local methods significantly outperform their global counterparts, especially LocalGS and LocalGD which show the best overall performance. LocalSOR and LocalCH, although more efficient in convergence rate, have smaller improvements.

This figure shows the running time of three different GDE solvers (HK, Katz, and PPR) as a function of the precision parameter (e). The experiment was run on the wiki-talk dataset using 50 randomly chosen source nodes. The parameters for each solver (damping factor a for PPR, a for Katz, and temperature τ for HK) are specified in the caption. The plot visually demonstrates how the running time of each solver changes with varying levels of precision.

This figure compares the number of operations required by four standard iterative solvers (GS, SOR, GD, CH) and their localized counterparts (LocalGS, LocalSOR, LocalGD, LocalCH) for computing graph diffusion vectors on 18 different graphs. The x-axis represents the graph index, and the y-axis represents the number of operations. Each group of four bars represents the operations required for a given graph by the four methods and their local counterparts. The graph index is sorted based on the performance of LocalGS, which shows that LocalGS significantly outperforms GS in terms of the number of operations for most graphs.

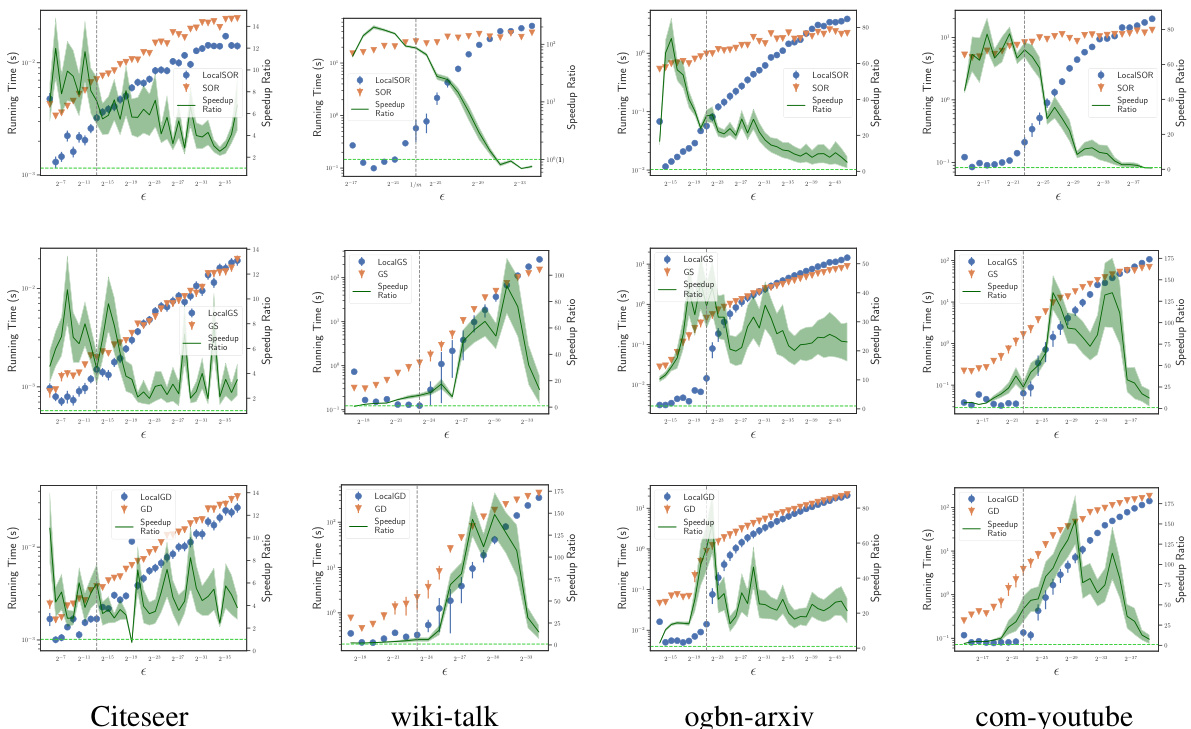

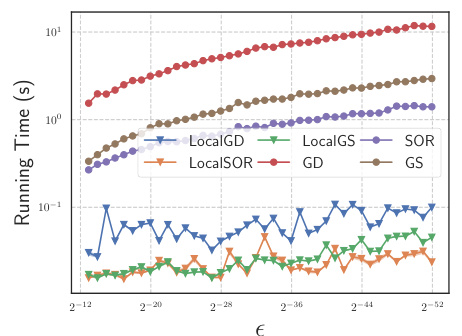

This figure compares the running times of global and local solvers (GD, LocalGD, SOR, LocalSOR, GS, LocalGS) for computing PPR vectors on the wiki-talk dataset. It shows the running times as a function of epsilon (ε), demonstrating the significant speedup achieved by local methods, especially LocalGD, particularly on a GPU architecture. The figure highlights that the advantage of local methods over global methods is pronounced, especially when using GPUs and when epsilon is within a certain range.

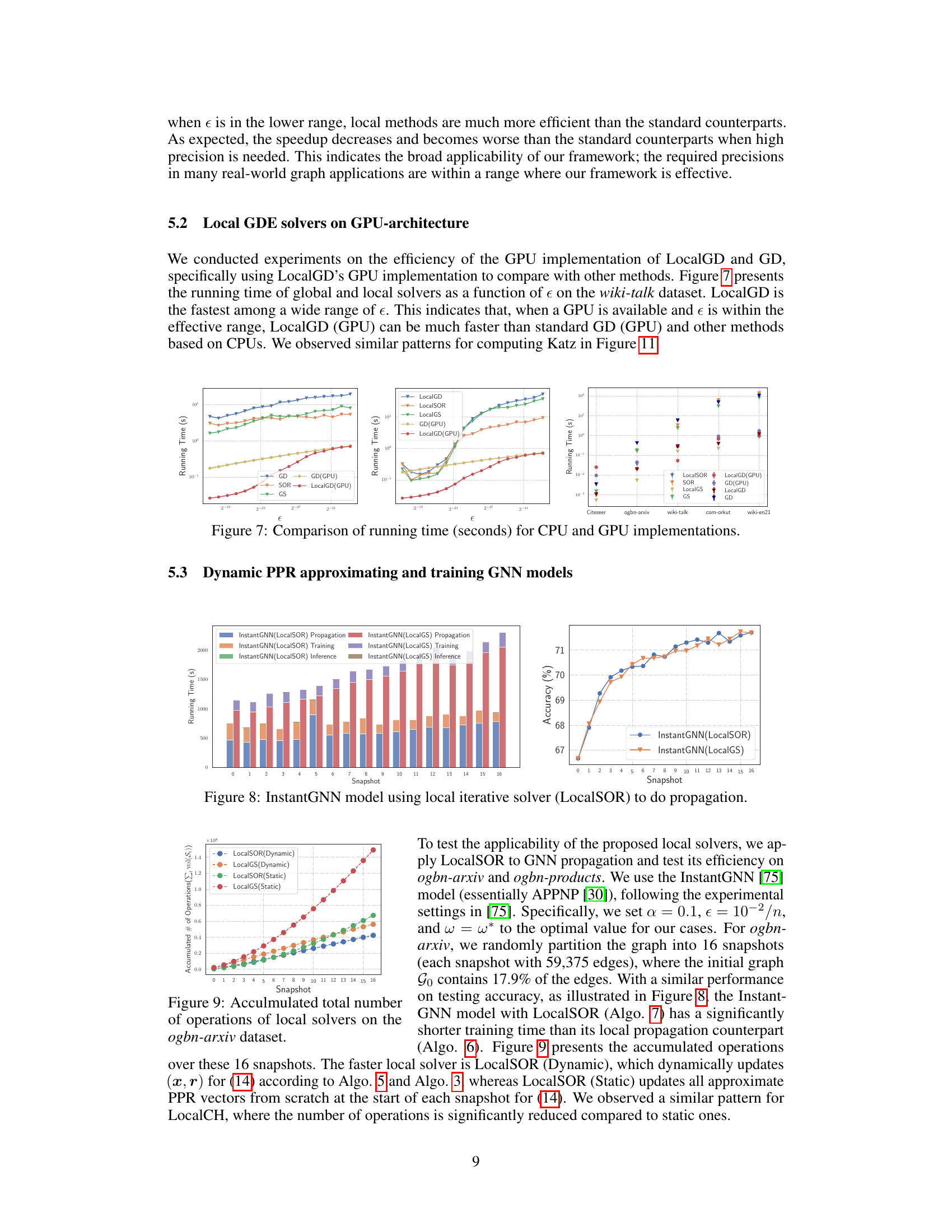

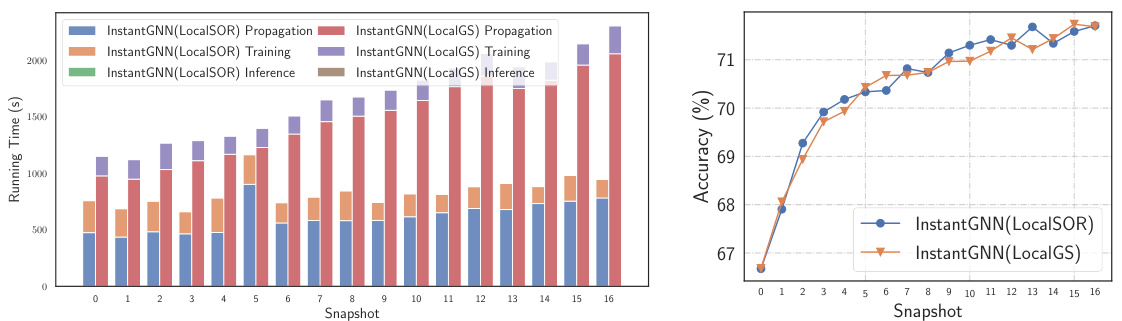

This figure visualizes the results of using InstantGNN with LocalSOR for propagation, training, and inference tasks on a dynamic graph. It shows that the local solver, LocalSOR, significantly outperforms LocalGS in terms of running time, especially for training. The accuracy achieved by both methods is comparable, indicating that LocalSOR offers an efficient way to improve the speed of training dynamic graph neural networks without sacrificing accuracy.

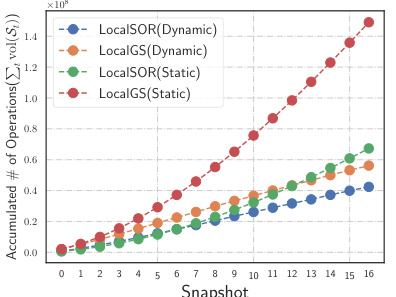

The figure shows the accumulated number of operations needed by LocalSOR and LocalGS for solving dynamic PPR over 16 snapshots on three different dynamic graphs: ogbn-arxiv, ogbn-products and ogbn-papers100M. It compares the performance of the dynamic variants (LocalSOR(Dynamic) and LocalGS(Dynamic)) against the static variants (LocalSOR(Static) and LocalGS(Static)). It demonstrates that the dynamic variants of the algorithms are significantly more efficient in terms of operations than the static variants, especially as the number of snapshots increases. This highlights one of the key advantages of using local solvers in dynamic settings.

This figure compares the number of operations required by the APPR algorithm using FIFO queue and Gauss-Southwell algorithm using Priority queue. The results are shown for various datasets and parameters (α and ε). The x-axis represents the source node, and the y-axis represents the ratio of operations between the two methods (log scale).

This figure compares the running times of global and local solvers (GD, LocalGD, SOR, LocalSOR, GS, LocalGS) as a function of epsilon (e) on the wiki-talk dataset. It showcases the performance gains achieved by using GPU implementations of the local solvers (LocalGD and LocalGD(GPU)) compared to their CPU-based counterparts and other global methods. The figure demonstrates that LocalGD(GPU) is generally the fastest, highlighting the advantages of using local methods and GPU acceleration.

This figure compares the number of operations required by four standard iterative solvers (GS, SOR, GD, CH) and their localized versions (LocalGS, LocalSOR, LocalGD, LocalCH) for approximating graph diffusion vectors on 18 different graphs. The x-axis represents the graph index, ordered based on the performance of LocalGS, and the y-axis represents the number of operations (in log scale). The figure demonstrates that localized solvers significantly reduce the number of operations required, especially for larger graphs.

This figure compares the number of operations required by four standard iterative solvers (SOR, GS, GD, CH) and their localized versions (LocalSOR, LocalGS, LocalGD, LocalCH) for approximating graph diffusion vectors on 18 different graphs. The x-axis represents the graph index, sorted by the performance of the LocalGS method. The y-axis shows the number of operations on a logarithmic scale. The figure demonstrates that the localized methods consistently require far fewer operations than their global counterparts, highlighting the efficiency gains achieved through localization.

This figure compares the number of operations needed by four standard iterative methods (GS, SOR, GD, CH) and their localized versions (LocalGS, LocalSOR, LocalGD, LocalCH) for approximating graph diffusion vectors on 18 different graphs. The x-axis represents the graphs, ordered by the performance of the LocalGS method. The y-axis shows the number of operations. The figure visually demonstrates the significant speedup achieved by the localized methods compared to their global counterparts, highlighting the efficiency gains from the proposed local diffusion process framework.

This figure compares the number of operations required for four standard iterative solvers (SOR, GS, GD, CH) and their localized counterparts (LocalSOR, LocalGS, LocalGD, LocalCH) across 18 different graphs. The x-axis represents the graph index, sorted based on the performance of LocalGS, indicating the relative efficiency of each method across various graph structures. The y-axis represents the total number of operations, which measures the computational cost of each algorithm. The figure visually demonstrates that the localized methods consistently require significantly fewer operations than their standard counterparts, highlighting the efficiency gains achieved through the proposed localization framework.

This figure shows the accumulated number of operations for LocalSOR (Dynamic), LocalGS (Dynamic), LocalSOR (Static), and LocalGS (Static) on three dynamic graphs: ogbn-arxiv, ogbn-products, and ogbn-papers100M. The x-axis represents the snapshot number, and the y-axis represents the accumulated number of operations. The plot shows that the dynamic versions of both LocalSOR and LocalGS have a significantly smaller number of operations compared to the static versions, demonstrating the efficiency of dynamic GDE calculations. The difference in performance between LocalSOR and LocalGS is also noticeable across different graphs.

This figure compares the performance of InstantGNN models using LocalSOR and LocalGS for dynamic PPR approximation and training. It shows the running time for propagation, training, and inference over 16 snapshots, along with the accuracy achieved. LocalSOR demonstrates significant speed improvements for all three tasks, while maintaining comparable accuracy to LocalGS.

This figure compares the running times of standard and local solvers for computing Personalized PageRank (PPR), Katz centrality, and Heat Kernel (HK) diffusion vectors on the wiki-talk graph dataset as the precision parameter (ε) varies. It demonstrates how the performance of local solvers changes with respect to the precision needed and shows that local solvers can significantly speed up the computation under certain conditions.

More on tables

This table lists four example graph diffusion equations (GDEs): Personalized PageRank (PPR), Katz centrality, Heat kernel (HK), and Inverse PageRank (IPR). For each GDE, the table provides the corresponding propagation matrix (M), the sequence of coefficients (ck), and the source vector (s) used in the general GDE equation f = Σk=0∞ ckMk s.

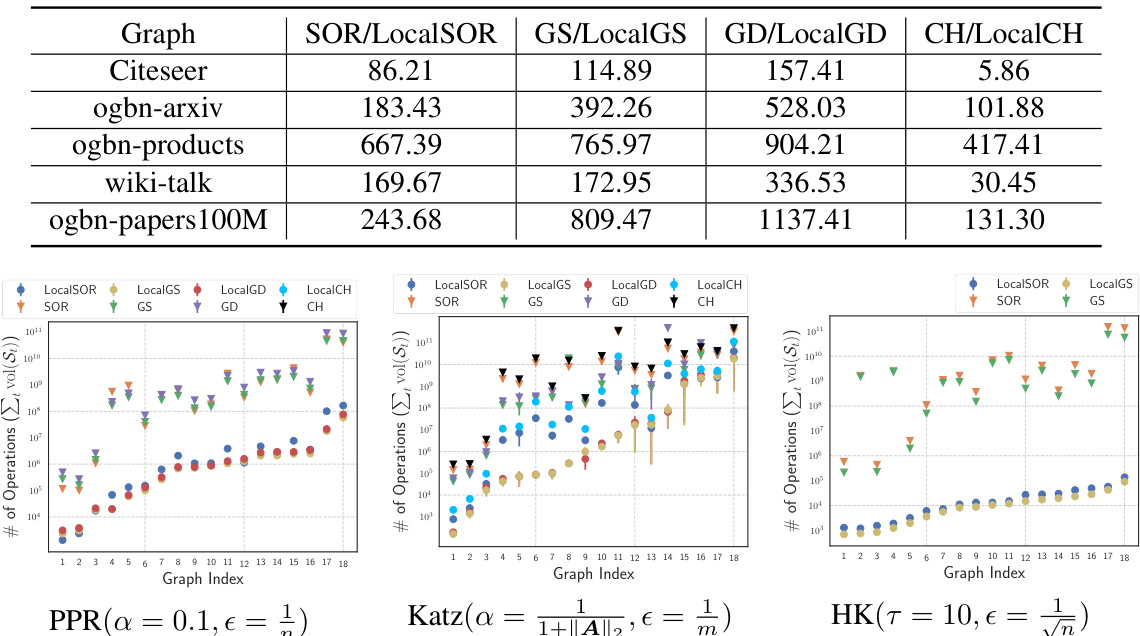

This table presents the speedup ratios achieved by using local solvers (LocalSOR, LocalGS, LocalGD, LocalCH) compared to their global counterparts (SOR, GS, GD, CH) for computing PPR vectors. The speedup ratio is calculated as the ratio of the number of operations required by the global solver to the number of operations required by the corresponding local solver. The table shows that local solvers significantly outperform global solvers in terms of computational efficiency for various datasets.

This table presents the speedup ratios achieved by using local solvers (LocalSOR, LocalGS, LocalGD, and LocalCH) compared to their global counterparts (SOR, GS, GD, and CH) for computing Personalized PageRank (PPR) vectors. The speedup ratio is calculated as the number of operations of the global algorithm divided by the number of operations of the corresponding local algorithm. Higher values indicate greater speedup from the local algorithms. The table includes results for several datasets (Citeseer, ogbn-arxiv, ogbn-products, wiki-talk, and ogbn-papers100M), showcasing the performance improvements across different graph sizes.

This table presents the speedup ratios achieved by using local solvers compared to their global counterparts for computing PPR vectors on various graph datasets. The speedup ratio is calculated as the number of operations of the standard algorithm divided by the number of operations of the corresponding local solver. Higher speedup ratios indicate greater efficiency gains from using the local solvers.

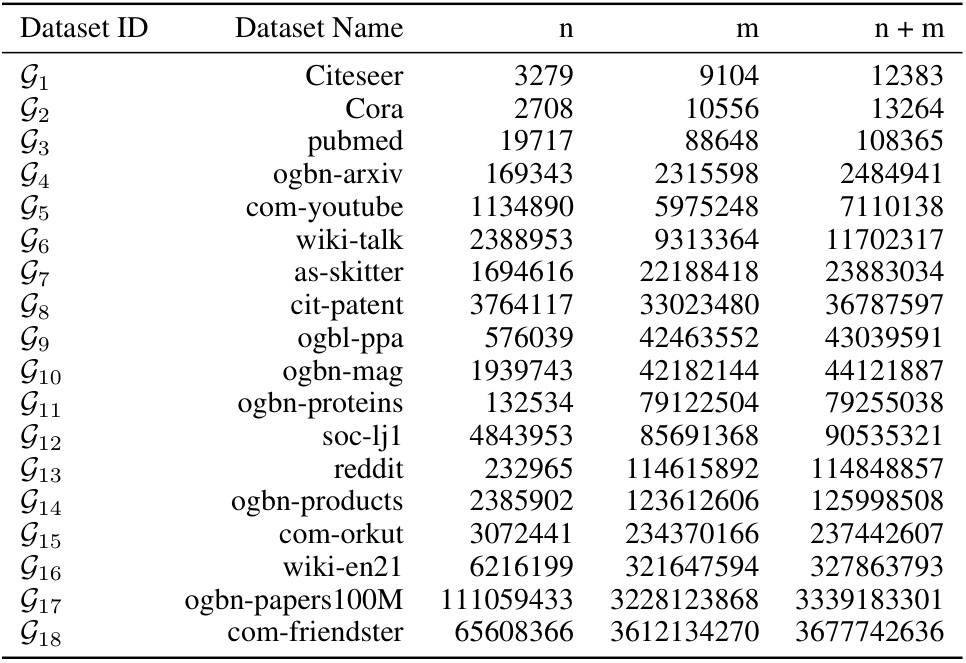

This table presents the statistics of the 18 graph datasets used in the experiments. For each dataset, it provides the number of nodes (n), the number of edges (m), and the sum of nodes and edges (n + m). The datasets are ordered by the value of n + m, ranging from smaller to larger graphs.

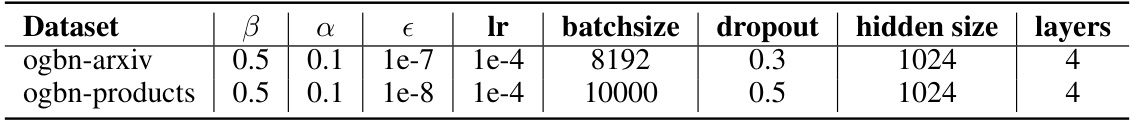

This table presents the hyperparameters used in the InstantGNN model training experiments. It shows the values for beta (β), alpha (α), epsilon (ε), learning rate (lr), batch size, dropout rate, hidden layer size, and number of layers used for the ogbn-arxiv and ogbn-products datasets.

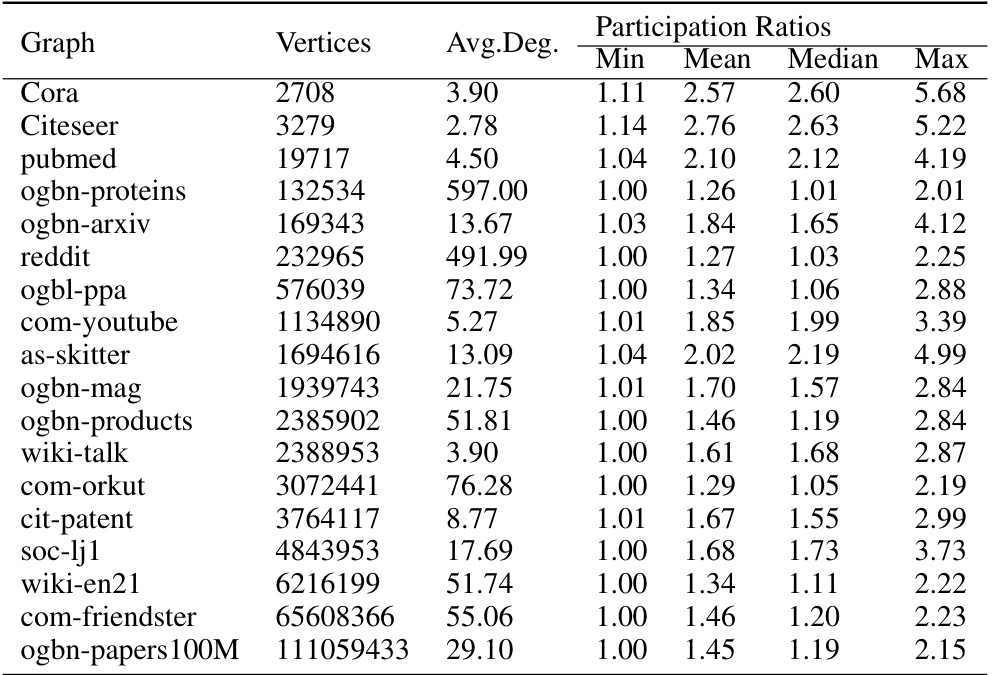

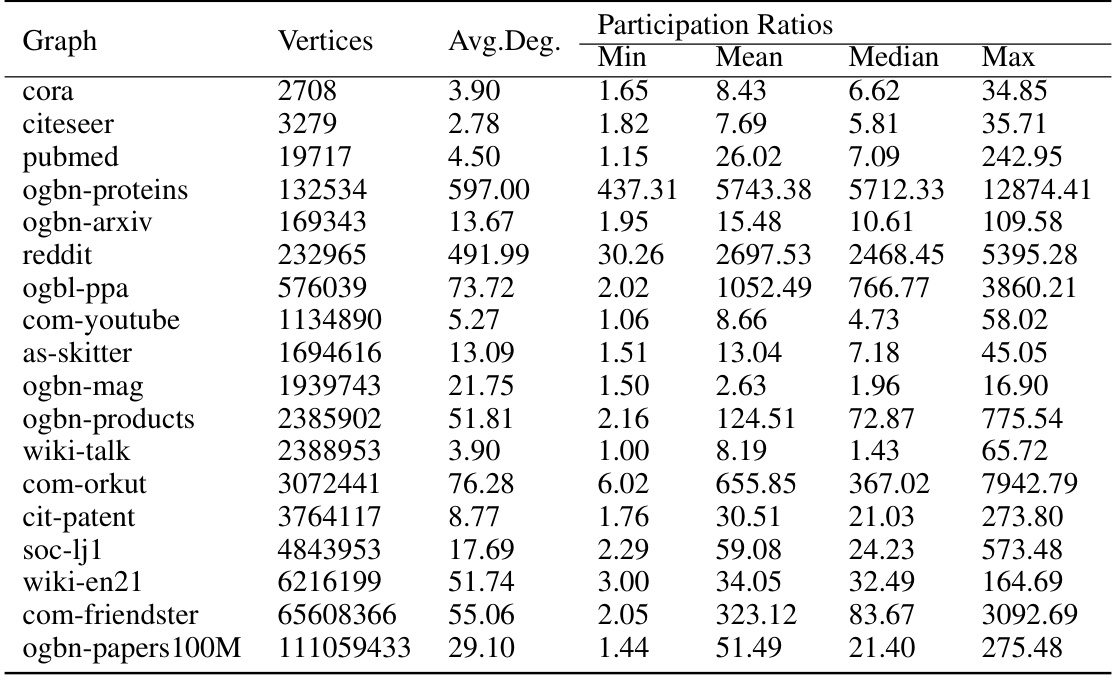

This table presents the unnormalized participation ratios for Personalized PageRank (PPR) with a damping factor α of 0.1, calculated for 18 different graphs. For each graph, the table shows the number of vertices, the average degree, and the minimum, mean, median, and maximum participation ratios. The participation ratio is a measure of the localization of the PPR vector, indicating how concentrated the vector’s values are across the nodes of the graph.

This table presents the unnormalized participation ratios for the Personalized PageRank (PPR) algorithm with a damping factor α of 0.1. For each of the 18 graphs listed, the table shows the average degree, minimum, mean, median, and maximum participation ratios. The participation ratio is a measure of the localization of the PPR vector, indicating how concentrated the vector’s values are across the nodes of the graph. Lower participation ratios generally imply greater localization of the PPR vector.

This table presents the unnormalized participation ratios for the Heat Kernel (HK) diffusion equation with a temperature parameter τ set to 10. It shows the minimum, mean, median, and maximum participation ratios for each of the listed graphs, along with the average degree and the number of vertices in each graph. The participation ratio is a measure of the localization of the diffusion vector, indicating how concentrated the diffusion values are across the nodes of the graph. Lower participation ratios suggest higher localization.

Full paper#