↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

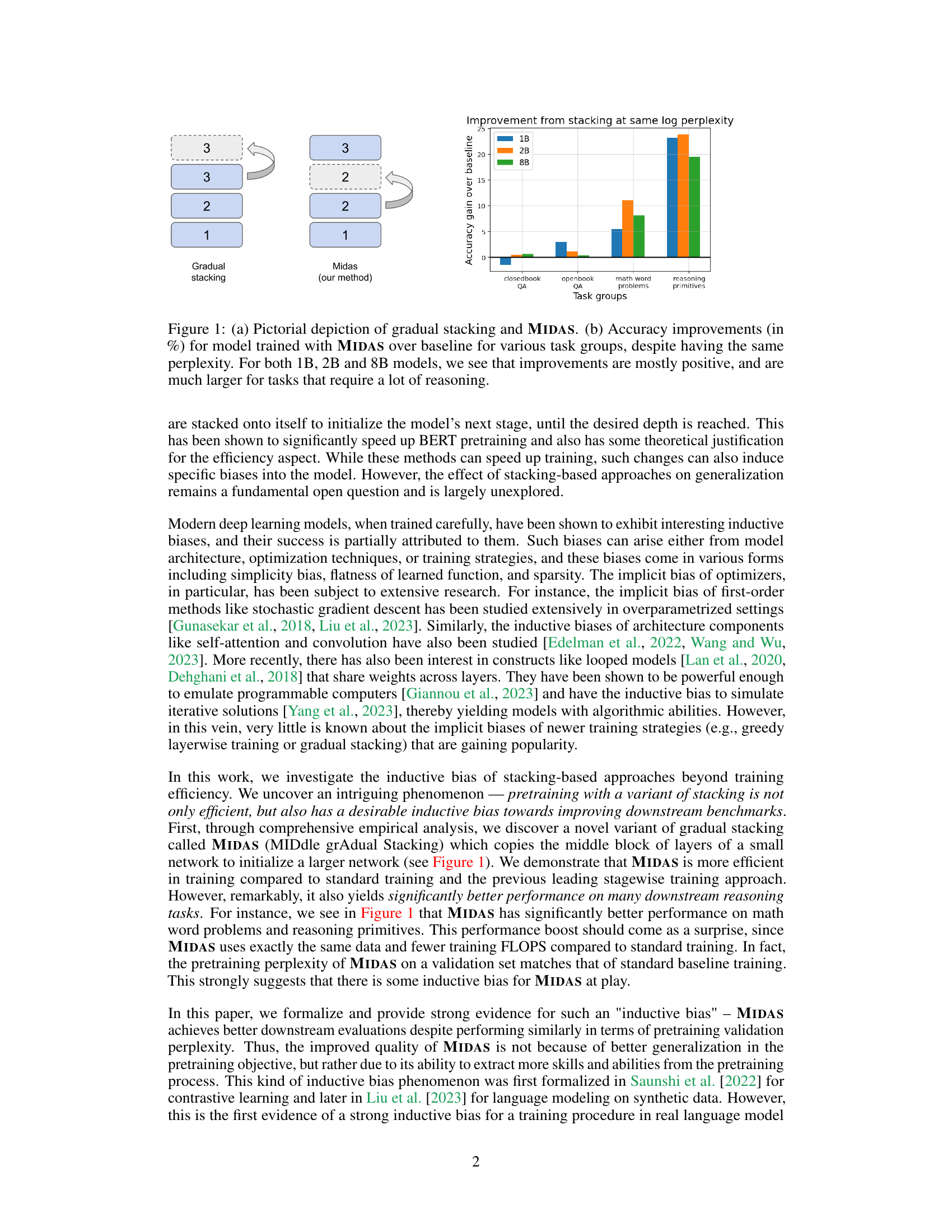

Large language models demand efficient training. Gradual stacking, which incrementally adds layers to a model, offers efficiency but its impact on model biases remains under-explored. This paper addresses this gap. Existing stacking methods often stack new layers atop existing ones, potentially disrupting the natural layer hierarchy and functionality. Furthermore, efficiency gains are not always accompanied by improved downstream performance.

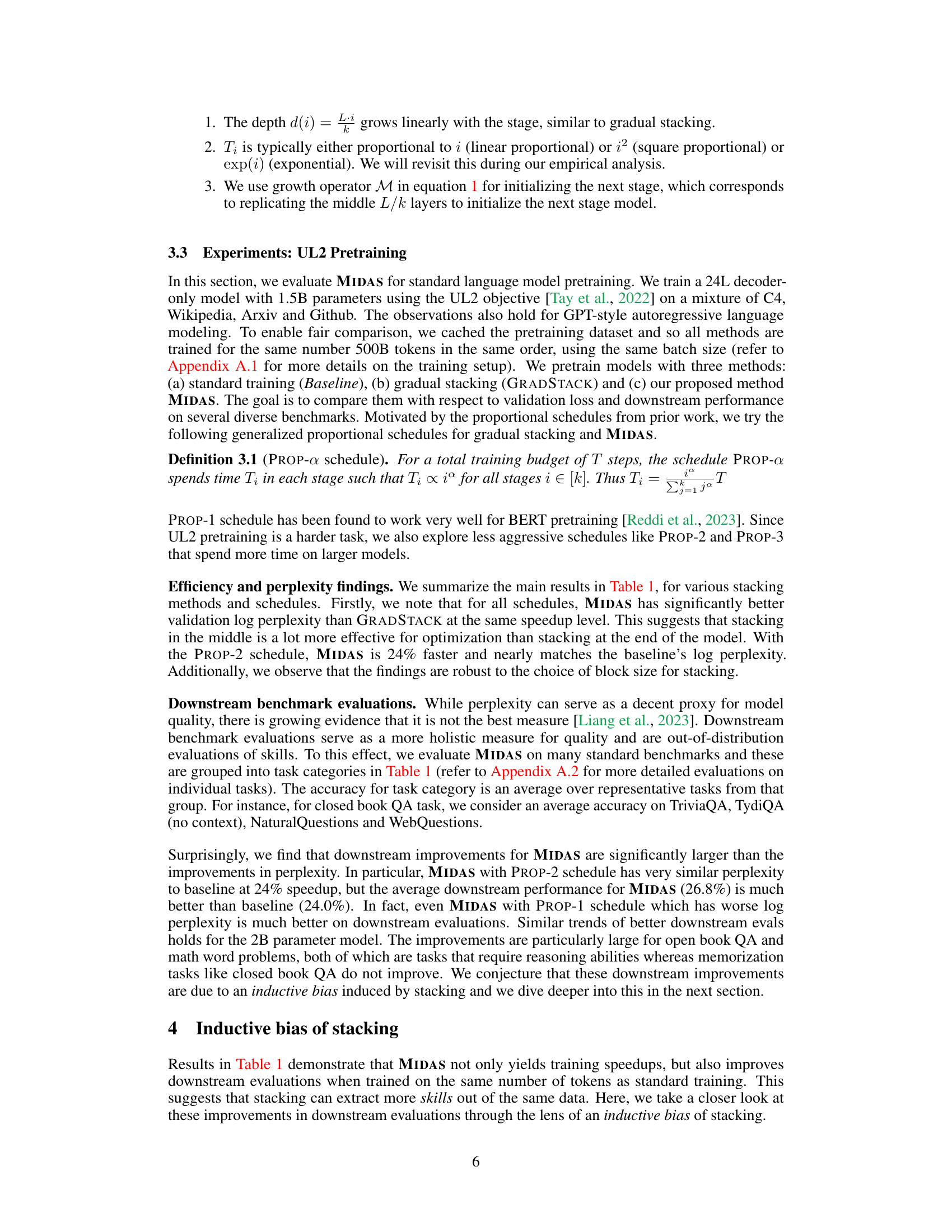

The paper introduces MIDAS, a novel gradual stacking variant. MIDAS stacks middle layers of a smaller model to initialize the next stage, avoiding the potential issues of stacking on top. This strategy proves surprisingly effective: MIDAS improves training speed significantly while simultaneously enhancing downstream reasoning abilities on tasks like reading comprehension and math problems – with no increase in pretraining perplexity. The authors construct synthetic reasoning tasks that demonstrate MIDAS’s superiority even more clearly, thus providing robust empirical evidence for this interesting inductive bias.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in deep learning and NLP because it introduces MIDAS, a novel training method that not only boosts efficiency but also surprisingly enhances model reasoning abilities. This discovery challenges existing assumptions about the inductive biases of training strategies and opens new avenues for research into model architecture and training techniques to improve reasoning performance. The findings, verified across various model sizes, are significant for optimizing the development and application of large language models in various downstream reasoning tasks.

Visual Insights#

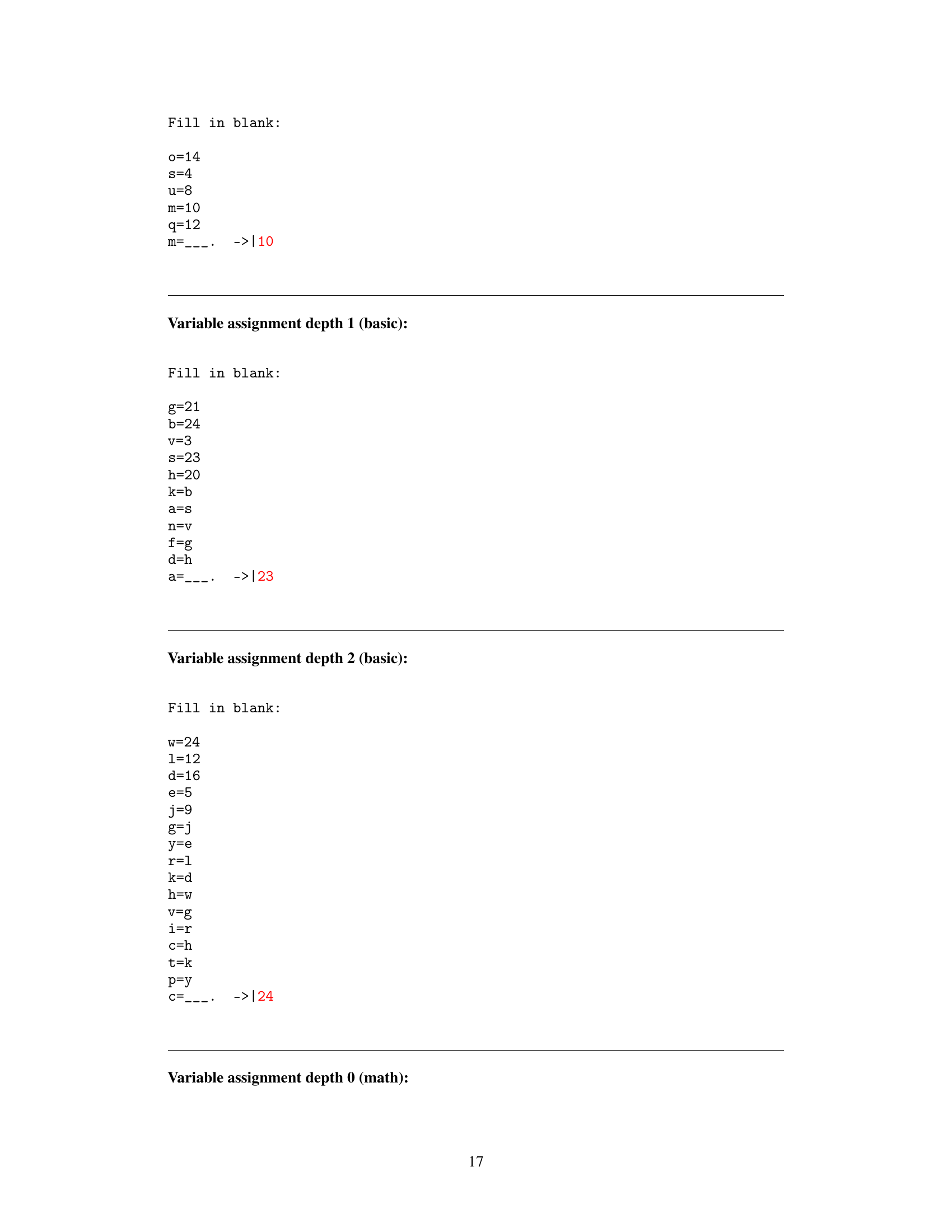

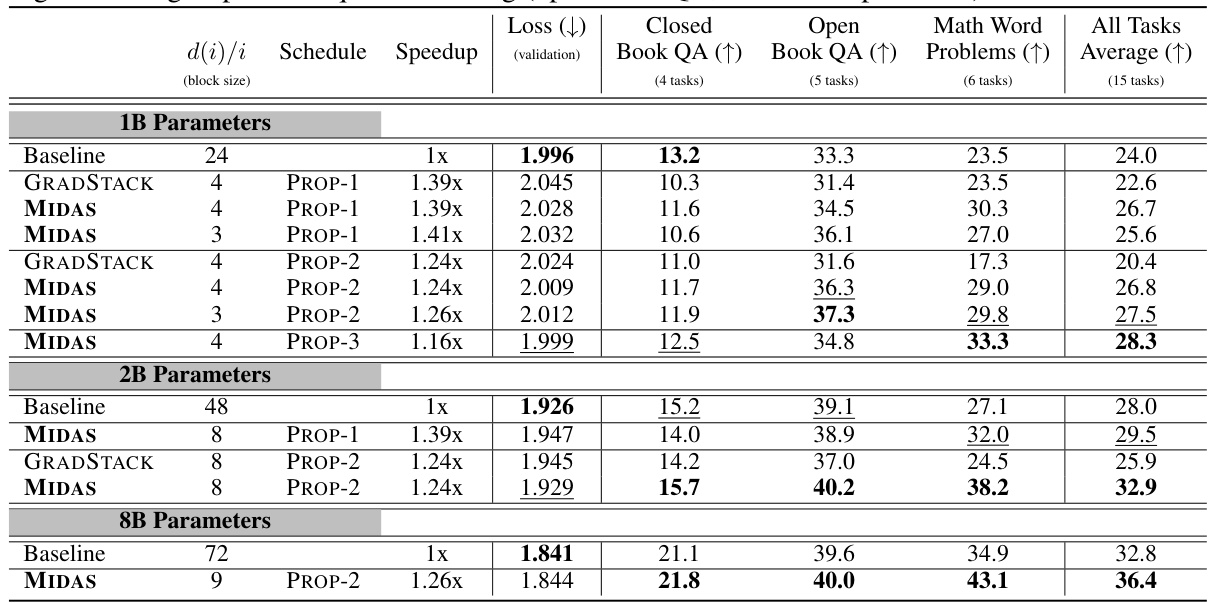

This figure shows a comparison between gradual stacking and MIDAS (a novel variant of gradual stacking proposed in the paper). Panel (a) provides a visual illustration of the two methods. Panel (b) presents a bar chart displaying the accuracy improvements achieved by MIDAS compared to a baseline method across different task groups (closed-book QA, open-book QA, math word problems, and reasoning primitives) for models with 1B, 2B, and 8B parameters. Importantly, MIDAS achieves these accuracy improvements while maintaining the same perplexity as the baseline.

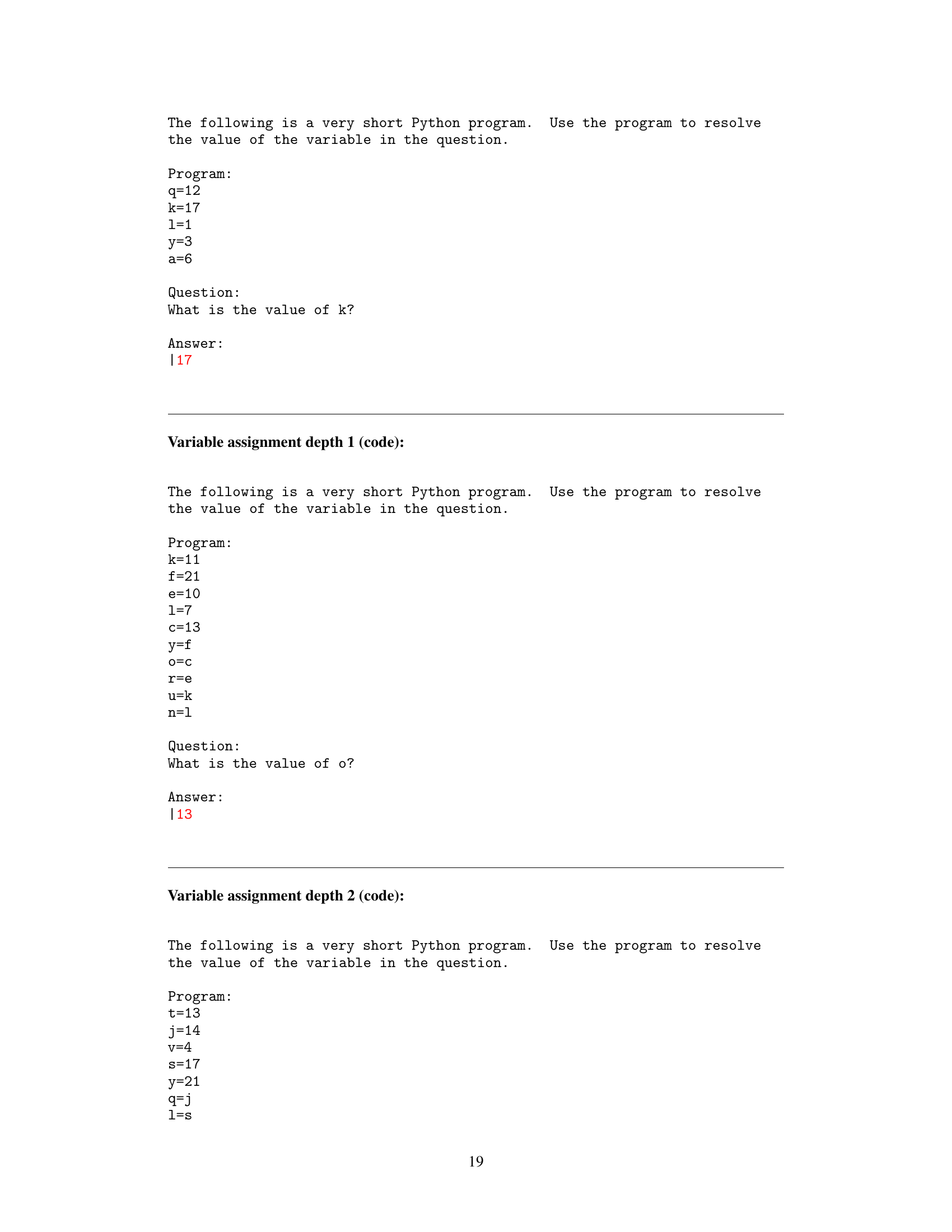

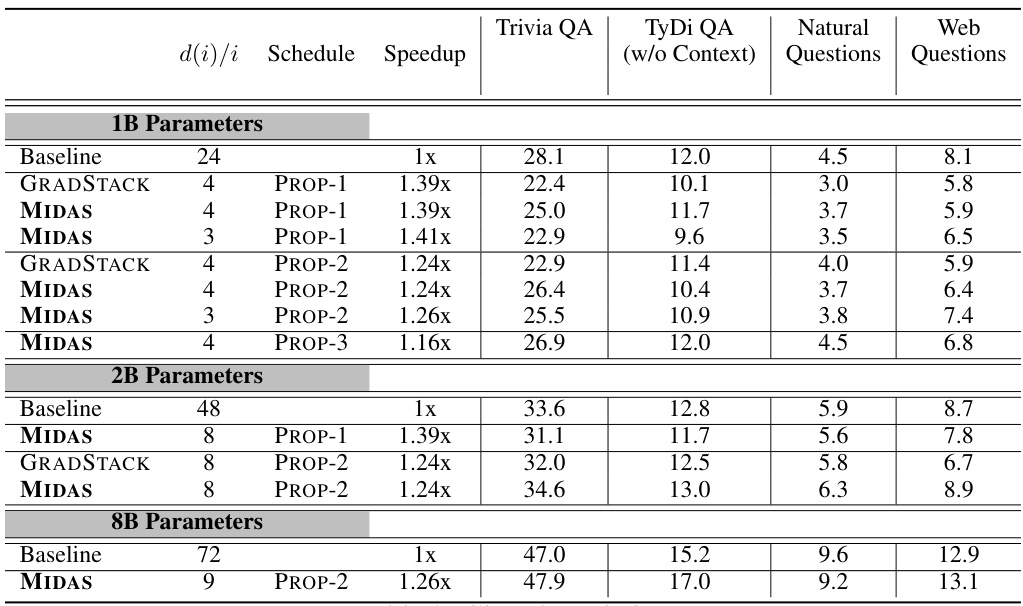

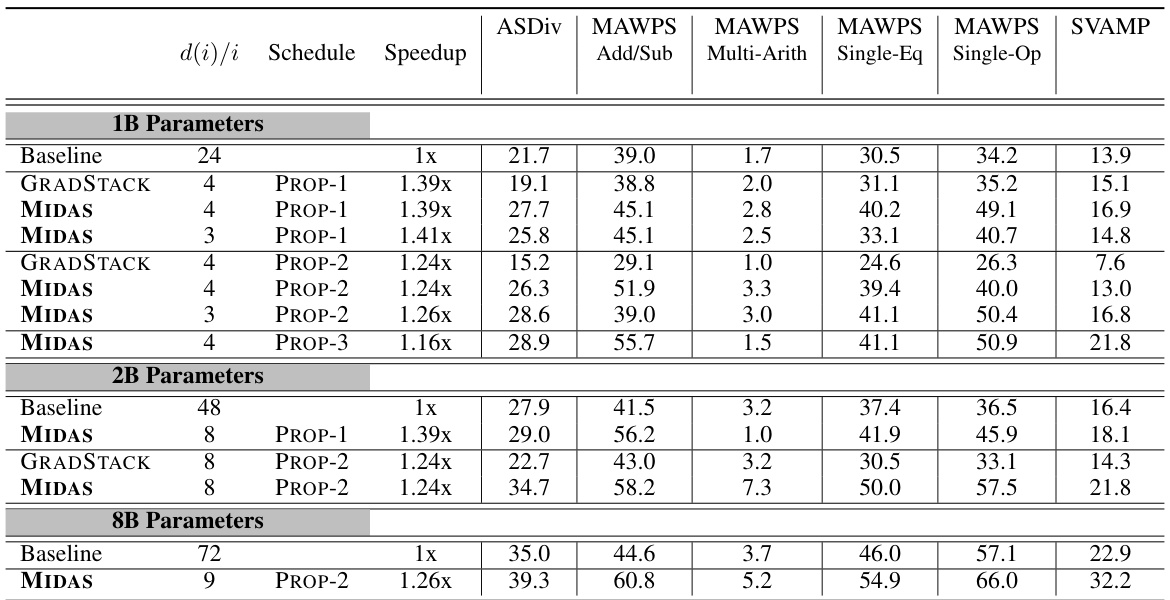

This table presents the downstream evaluation results for three different language model sizes (1B, 2B, and 8B parameters) trained using three different methods: standard training (Baseline), gradual stacking (GRADSTACK), and the proposed MIDAS method. It compares their performance across three task groups: closed-book QA, open-book QA, and math word problems, showing the average accuracy improvements and validation loss. The table highlights the superior performance of MIDAS in terms of both speed and accuracy, particularly on tasks requiring reasoning, while maintaining comparable or even better perplexity compared to the Baseline.

In-depth insights#

Stacking’s Bias#

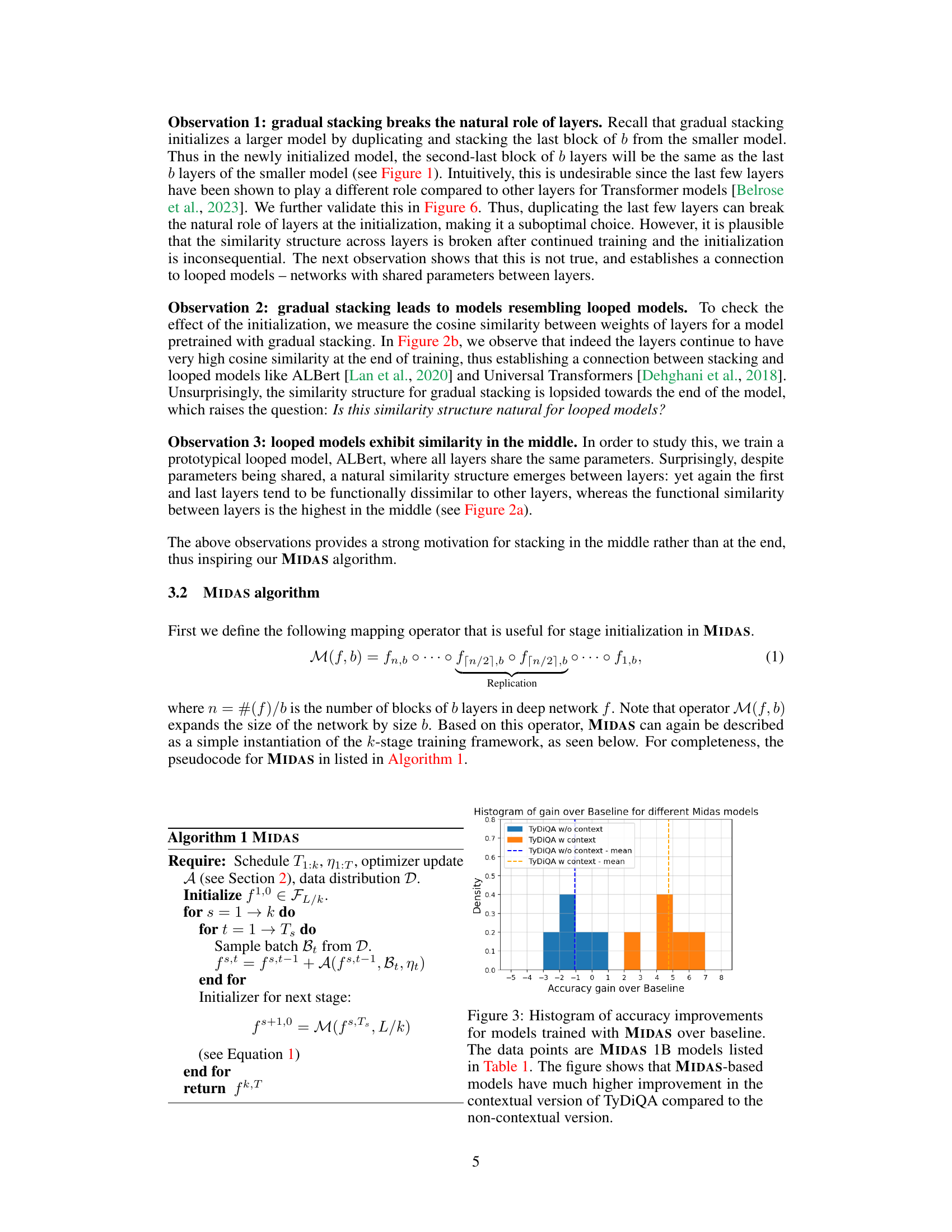

The concept of “Stacking’s Bias” in the context of deep learning models refers to the inherent biases introduced during the training process when employing stacking methods. These methods, such as gradual stacking or MIDAS, build larger models incrementally using smaller models as a basis. This incremental growth, although beneficial for training efficiency, inadvertently introduces biases into the resulting large model. The paper investigates this bias by comparing models trained using stacking against those trained with standard methods, observing performance on downstream tasks. The surprising finding is that while stacking models show comparable or even slightly worse perplexity, they exhibit superior performance on tasks requiring reasoning, such as reading comprehension and math problems. This suggests that the inductive bias of stacking towards reasoning is more than just an artifact of training efficiency. It’s an interesting and important phenomenon that deserves further investigation and theoretical explanation, potentially uncovering connections to looped models and the optimization algorithms involved.

MIDAS Method#

The MIDAS method, a novel variant of gradual stacking for language model training, presents a compelling approach to improving both training efficiency and downstream reasoning performance. Its core innovation lies in strategically copying the middle layers of a smaller model to initialize a larger one, in contrast to traditional methods that stack the final layers. This seemingly small change yields significant improvements: MIDAS is demonstrably faster than baseline training and GRADSTACK, often achieving similar or even better perplexity scores while drastically outperforming those methods on reasoning-intensive tasks. This improved performance is attributed to an inductive bias towards reasoning, evidenced by the superior performance on synthetic reasoning primitives, even without fine-tuning. The choice of copying the middle layers aligns with observations made on looped models, which exhibit similar properties and also suggests that the inductive bias stems from a connection between MIDAS and the architectural properties of looped networks. Further investigation with additional experiments and the construction of synthetic tasks bolster the hypothesis of an inductive bias, suggesting it is not simply due to improved generalization. The effectiveness of MIDAS has been validated on various-sized language models (1B, 2B, and 8B parameters), strengthening the robustness of these findings.

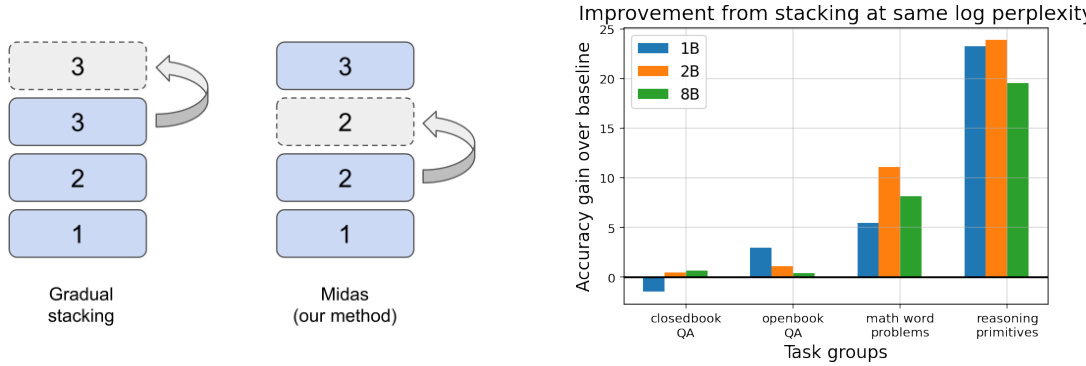

Reasoning Primitives#

The concept of “Reasoning Primitives” in the context of the research paper is crucial for isolating and understanding the inductive biases exhibited by the MIDAS model. These primitives represent fundamental building blocks of reasoning, enabling a controlled evaluation of the model’s ability to perform reasoning tasks. By designing simple synthetic tasks, such as induction copying, variable assignment, and pre-school math problems, the researchers were able to effectively dissect the model’s performance, moving beyond the limitations of standard benchmarks. The findings using these primitives provided stronger and more robust evidence for the inductive bias towards reasoning that MIDAS exhibited, confirming its effectiveness beyond standard real-world benchmarks and potentially showcasing a mechanism for improved reasoning capabilities in large language models. The consistent superior performance of the MIDAS model on these primitives compared to baselines suggests that MIDAS learns more fundamental reasoning skills during pretraining.

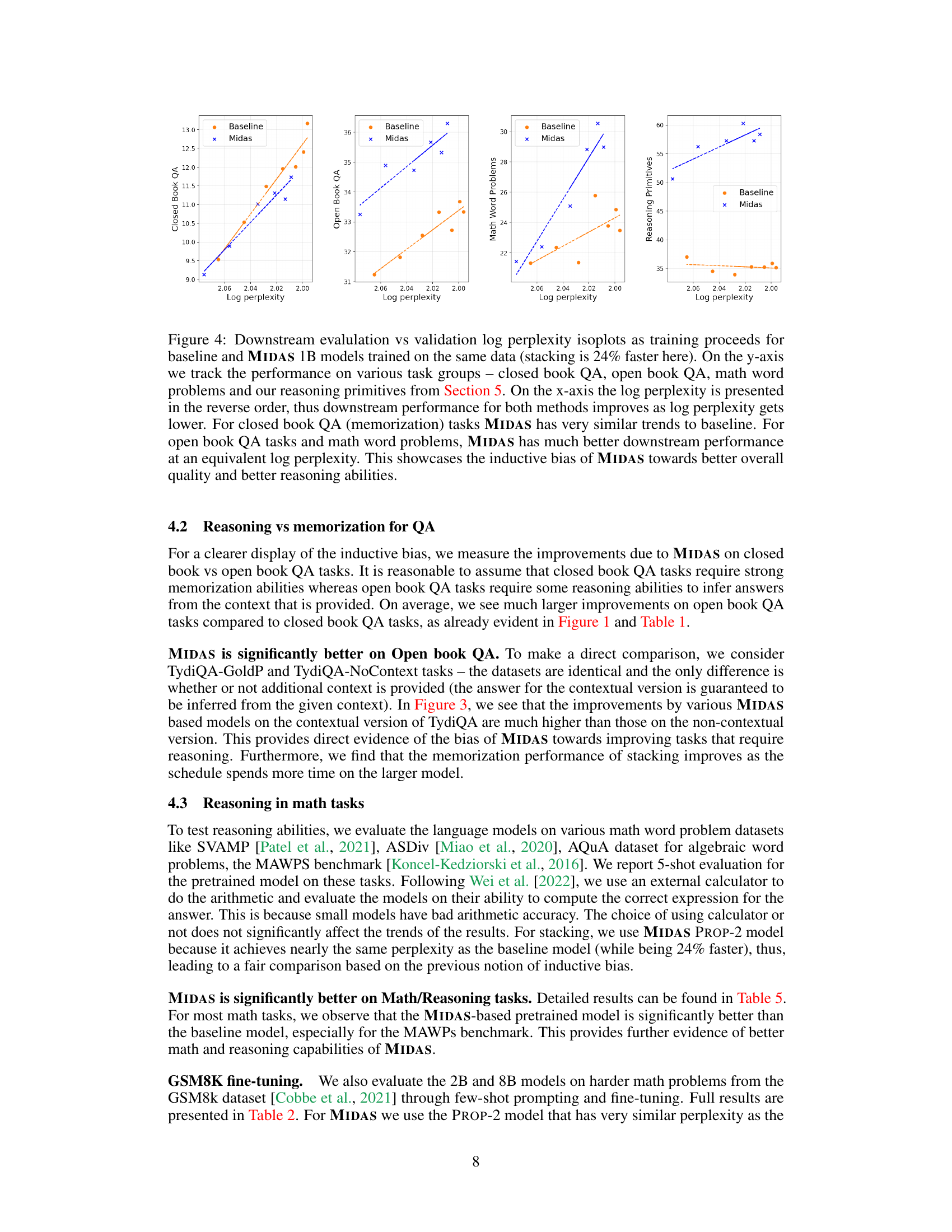

Loop Model Link#

The hypothetical “Loop Model Link” section would likely explore the connection between the inductive biases observed in stacking-based training and the inherent properties of looped models. It would delve into how the weight sharing and cyclical structures within looped models, such as the ALBERT architecture, might implicitly promote the development of reasoning abilities. A key argument might center on how the repeated processing of information through shared layers in looped models mirrors the iterative refinement found in stacking, thereby leading to similar inductive biases. The analysis could involve comparative studies of the weight similarity between layers in models trained with stacking and those in looped models. The discussion might hypothesize that the inductive bias towards reasoning in stacking isn’t simply about faster training but also about unintentionally emulating the iterative processing inherent in looped architectures. This could involve exploring the relationship between the number of layers, the block size in stacking, and the depth/performance tradeoffs in relation to the cyclical nature of looped models, potentially demonstrating that stacking implicitly induces a form of weight sharing, thereby linking it to the properties of looped architectures. Furthermore, the analysis could provide strong evidence linking these two models by demonstrating performance similarities on tasks requiring complex reasoning processes.

Future Work#

The paper’s conclusion mentions several promising avenues for future research. Investigating the interplay between memorization and reasoning in mathematical problem-solving is highlighted as a crucial area, particularly given MIDAS’s disproportionate improvement on reasoning-heavy tasks. Further exploration into the connection between MIDAS and looped models is warranted to fully understand the inductive bias observed. Additionally, a deeper dive into the design of reasoning primitives is suggested, focusing on creating a more comprehensive set of synthetic tasks to capture a wider range of reasoning abilities. Finally, more extensive analysis of the impact of hyperparameter choices and training schedules is necessary to confirm the robustness of MIDAS’s effectiveness and its inductive bias across different model sizes and training settings. These future research directions aim to not only refine MIDAS but also to provide a broader understanding of the fundamental principles underlying effective and efficient language model training.

More visual insights#

More on figures

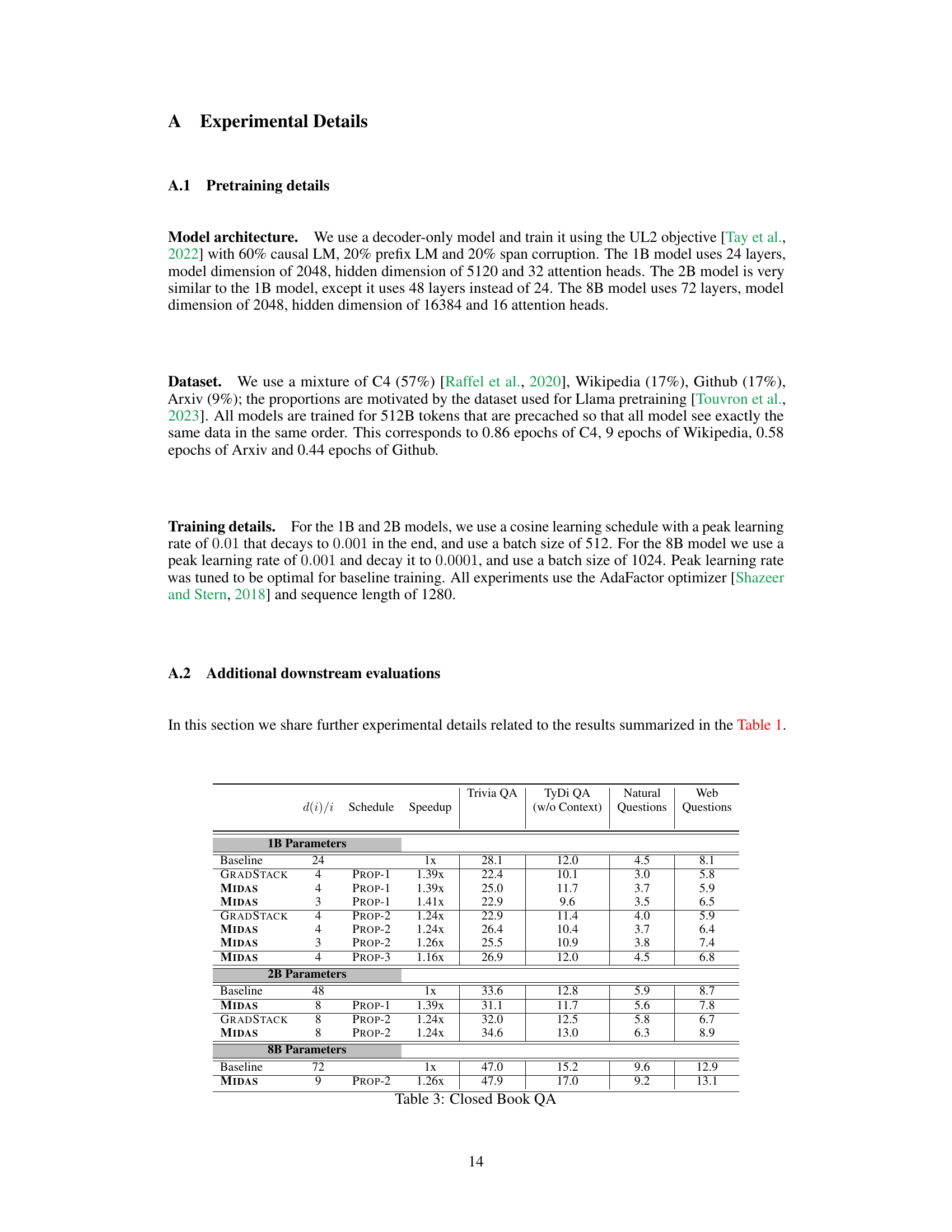

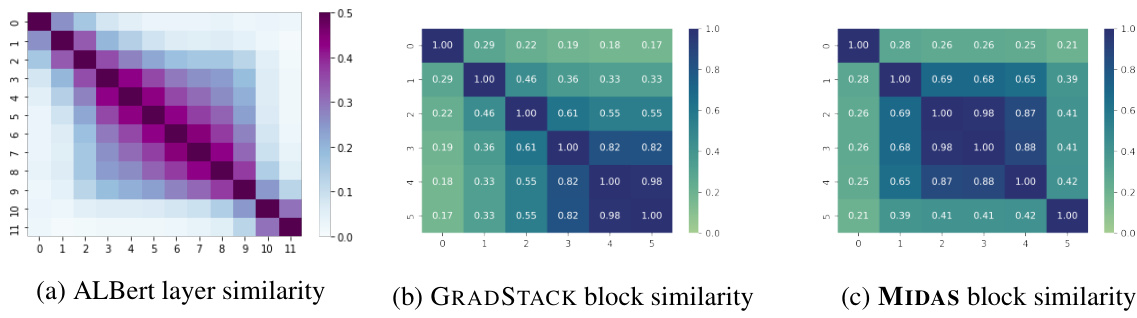

This figure shows the functional similarity between layers for different models. (a) shows the similarity structure in an ALBert model with weight sharing. (b) shows the block similarity in a UL2 model trained with GRADSTACK. (c) shows the block similarity in a UL2 model trained with MIDAS. The results suggest that stacking-based models have a strong connection to looped models, and MIDAS is more similar to ALBert-style looped models than GRADSTACK.

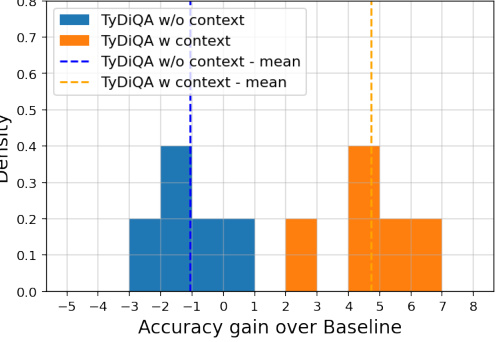

This histogram visualizes the accuracy improvements achieved by MIDAS over the baseline model for different tasks. The data used comes from the 1B parameter MIDAS models detailed in Table 1. Notably, the improvement is significantly greater for the contextual TyDiQA task than for the non-contextual version, highlighting MIDAS’s advantage in tasks that require contextual understanding.

This figure shows the downstream evaluation performance (y-axis) against the validation log perplexity (x-axis) for both baseline and MIDAS models. It compares four task groups: closed book QA, open book QA, math word problems, and reasoning primitives. The plot demonstrates that MIDAS achieves similar or better performance on open-book QA and math problems while having the same or even better perplexity than the baseline model, highlighting the inductive bias of MIDAS towards reasoning abilities.

This figure shows the accuracy improvements achieved by MIDAS compared to the baseline model across various reasoning primitives. The improvements are consistent across both 5-shot evaluation and fine-tuning, particularly for tasks of greater complexity (Depth 1 and 2).

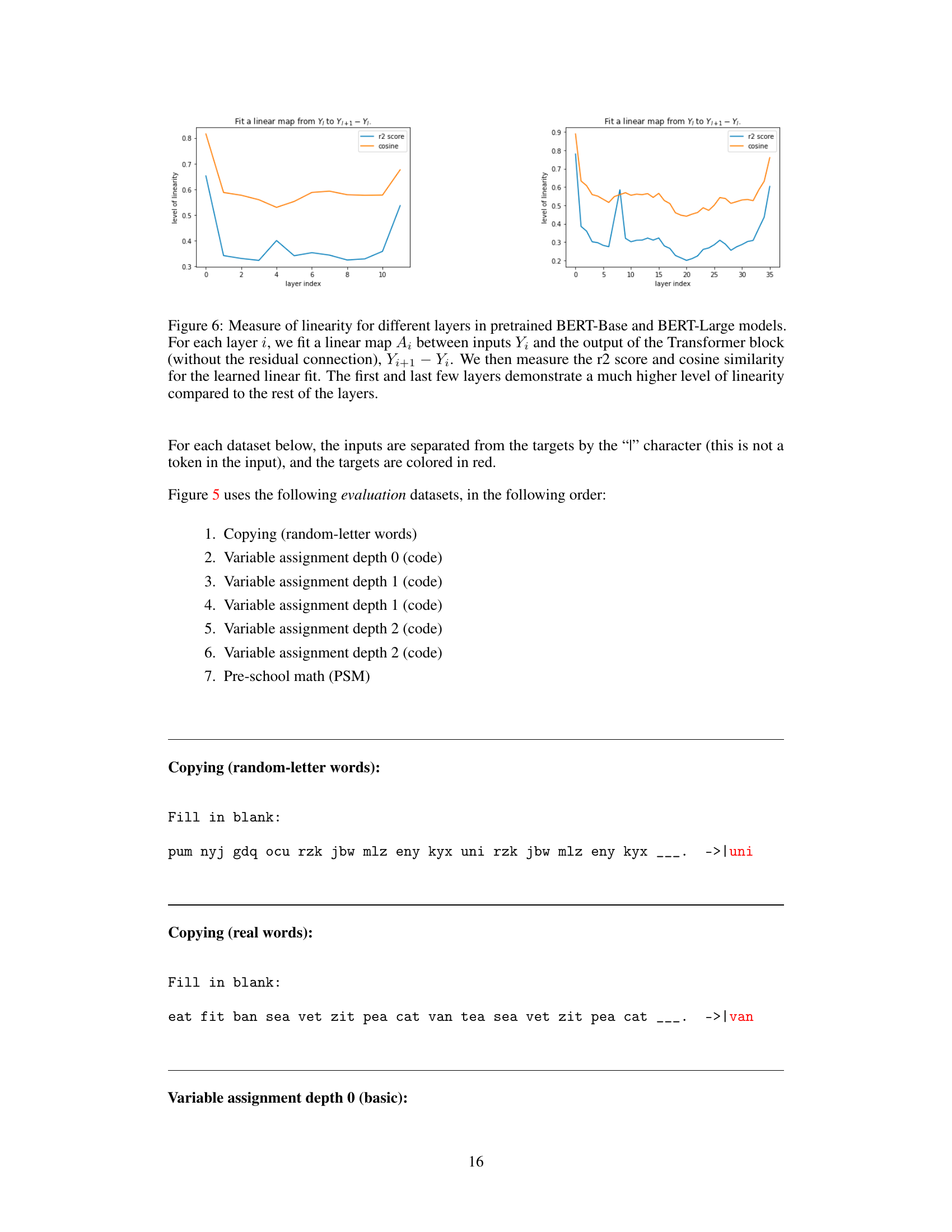

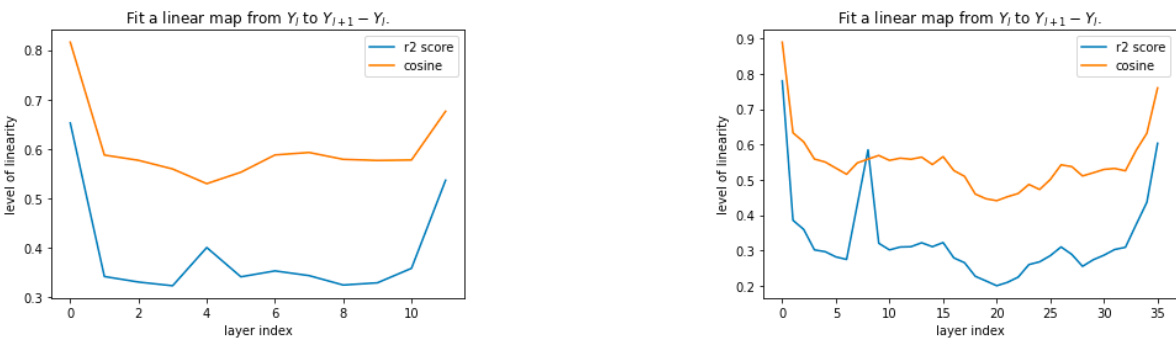

This figure shows the linearity of different layers in pre-trained BERT models (Base and Large). For each layer, a linear map is fit between inputs and the output of the transformer block (excluding residual connections). The R-squared and cosine similarity are then measured for the fit. The results show that the first and last few layers exhibit higher linearity than the rest, suggesting a difference in the role these layers play in the model.

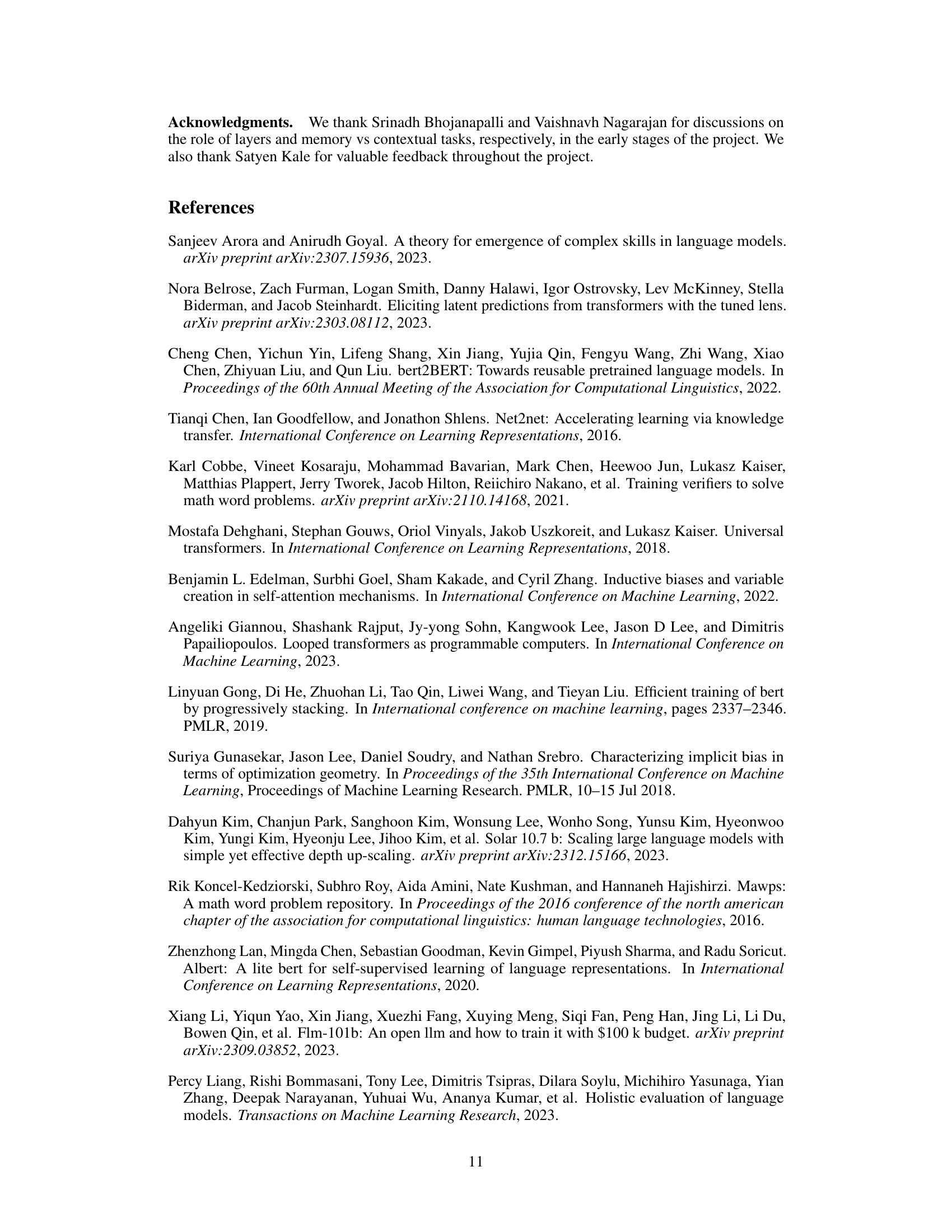

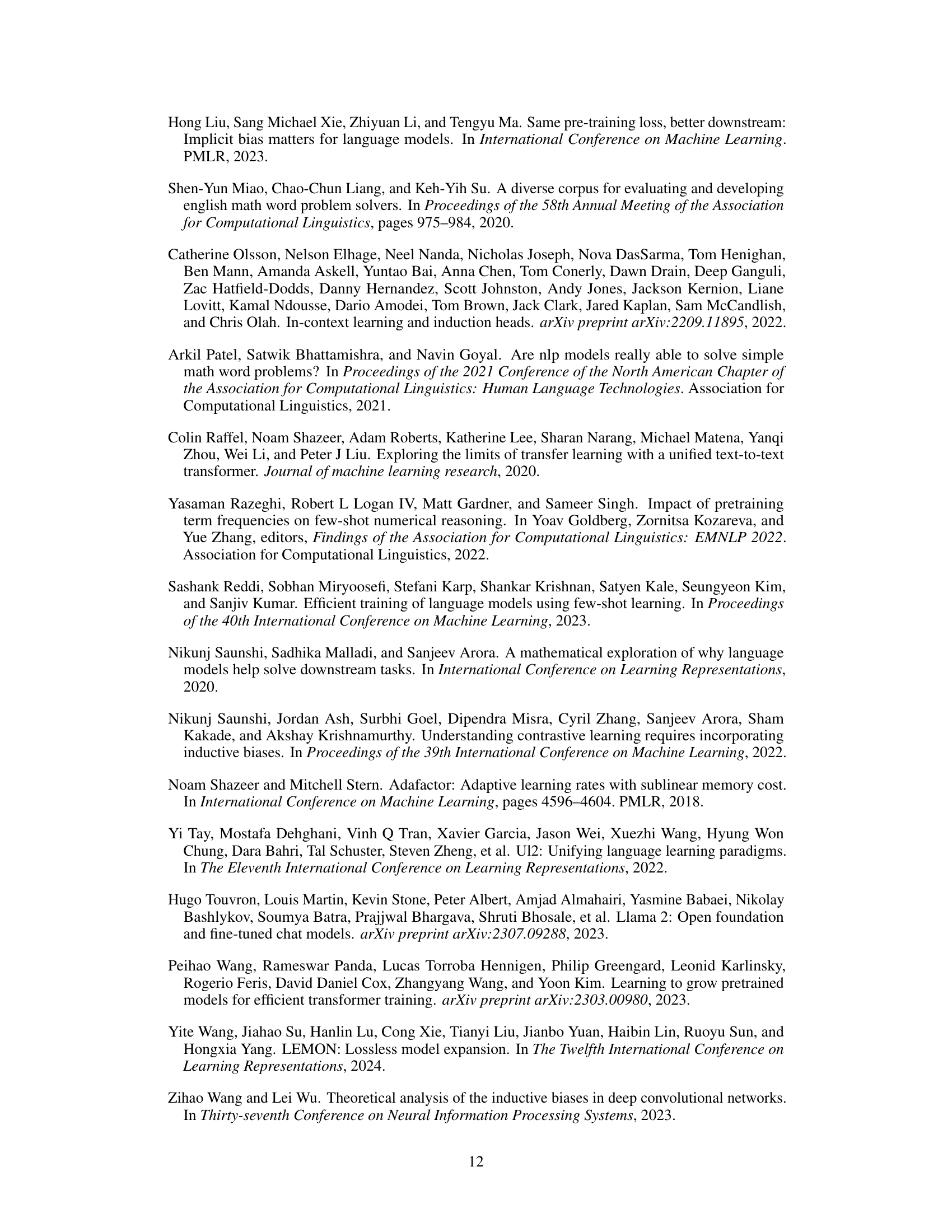

More on tables

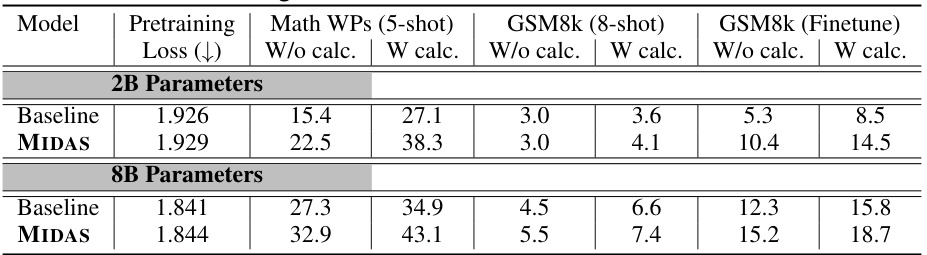

This table presents the downstream evaluation results for three different language models (1B, 2B, and 8B parameters) trained using three different methods: standard training (Baseline), gradual stacking (GRADSTACK), and the proposed MIDAS method. The table compares the models’ performance across three task categories (Closed Book QA, Open Book QA, and Math Word Problems) and overall, showing MIDAS’s superior performance and efficiency. The results highlight MIDAS’s inductive bias towards improving reasoning tasks.

This table presents the downstream evaluation results for UL2 pretrained language models with 1B, 2B, and 8B parameters, comparing standard training, gradual stacking, and the proposed MIDAS method. It shows MIDAS outperforms other methods, especially on reasoning tasks, while maintaining comparable or even better training efficiency.

This table presents downstream evaluation results for UL2 pretrained language models with 1B, 2B, and 8B parameters, comparing standard training (Baseline), gradual stacking (GRADSTACK), and the proposed MIDAS method. It shows accuracy improvements across different task categories (closed book QA, open book QA, math word problems) and overall, highlighting the efficiency and reasoning improvements of MIDAS, especially for tasks requiring reasoning abilities.

This table presents the downstream evaluation results for UL2 pretrained language models with 1B, 2B, and 8B parameters, comparing three training methods: standard training (Baseline), gradual stacking (GRADSTACK), and the proposed MIDAS method. It shows that MIDAS achieves better performance on downstream tasks, particularly those requiring reasoning, while maintaining or even improving training efficiency and log perplexity compared to the baseline.

This table presents downstream evaluation results for UL2 pretrained language models with 1B, 2B, and 8B parameters, comparing three training methods: standard training (Baseline), gradual stacking (GRADSTACK), and the proposed MIDAS method. It shows accuracy across three task groups (Closed Book QA, Open Book QA, Math Word Problems) and overall average performance. Key findings highlight MIDAS’s superior performance and efficiency compared to GRADSTACK and, surprisingly, comparable or even better downstream performance than Baseline despite similar or worse perplexity scores, especially on reasoning-intensive tasks. Appendix A provides details on specific tasks within each group.

This table presents the fine-tuning results for the variable assignment tasks (depth 1 and 2) from Figure 5. The results show the accuracy of MIDAS and Baseline models after fine-tuning on a small dataset (64 examples total). The accuracy is averaged across three runs, with standard deviations included to show variability.

Full paper#