↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Group equivariance has emerged as a valuable inductive bias in deep learning, enhancing generalization, data efficiency, and robustness. However, existing methods often impose overly restrictive constraints or require prior knowledge of exact symmetries, which may not be realistic for real-world data. This limits their applicability to datasets without clear symmetries or to those with limited data. Addressing this challenge requires methods that can dynamically discover and apply symmetries as soft constraints.

This paper proposes a novel weight-sharing scheme that learns symmetries directly from data, avoiding the need for pre-defined symmetries. The method defines learnable doubly stochastic matrices acting as soft permutation matrices on weight tensors, capable of representing both exact and partial symmetries. Through experiments, the authors demonstrate that the proposed approach effectively learns relevant weight-sharing schemes when symmetries are clear and outperforms methods relying on predefined symmetries in scenarios with partial symmetries or in the absence of them, achieving performance comparable to fully flexible models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel and flexible approach to learning symmetries in data, which addresses limitations of existing methods. It offers greater adaptability, handling partial symmetries, and being parameter-efficient, making it particularly relevant for scenarios with limited data or complex real-world datasets. The proposed weight-sharing scheme opens avenues for future research in discovering and utilizing symmetries for enhanced model performance and generalization.

Visual Insights#

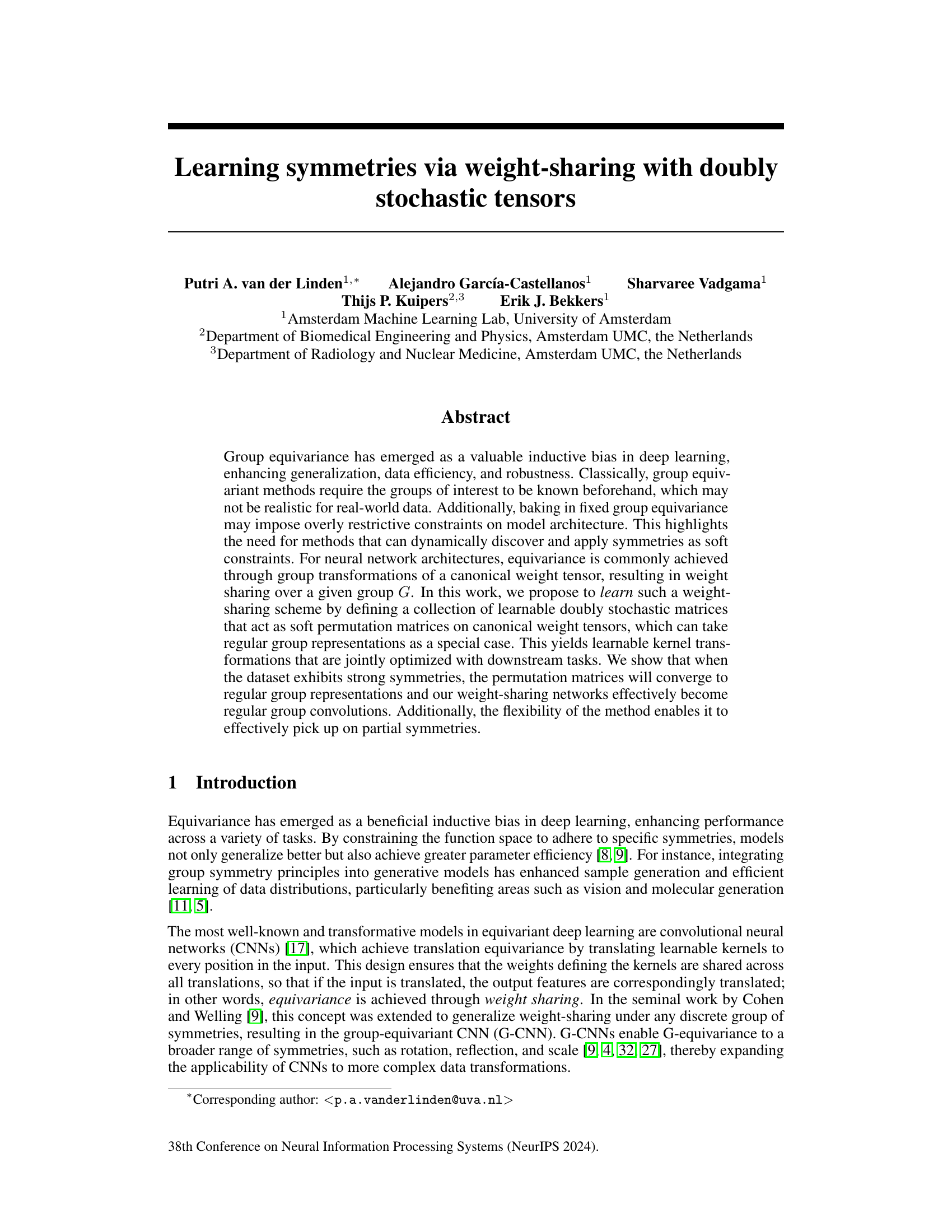

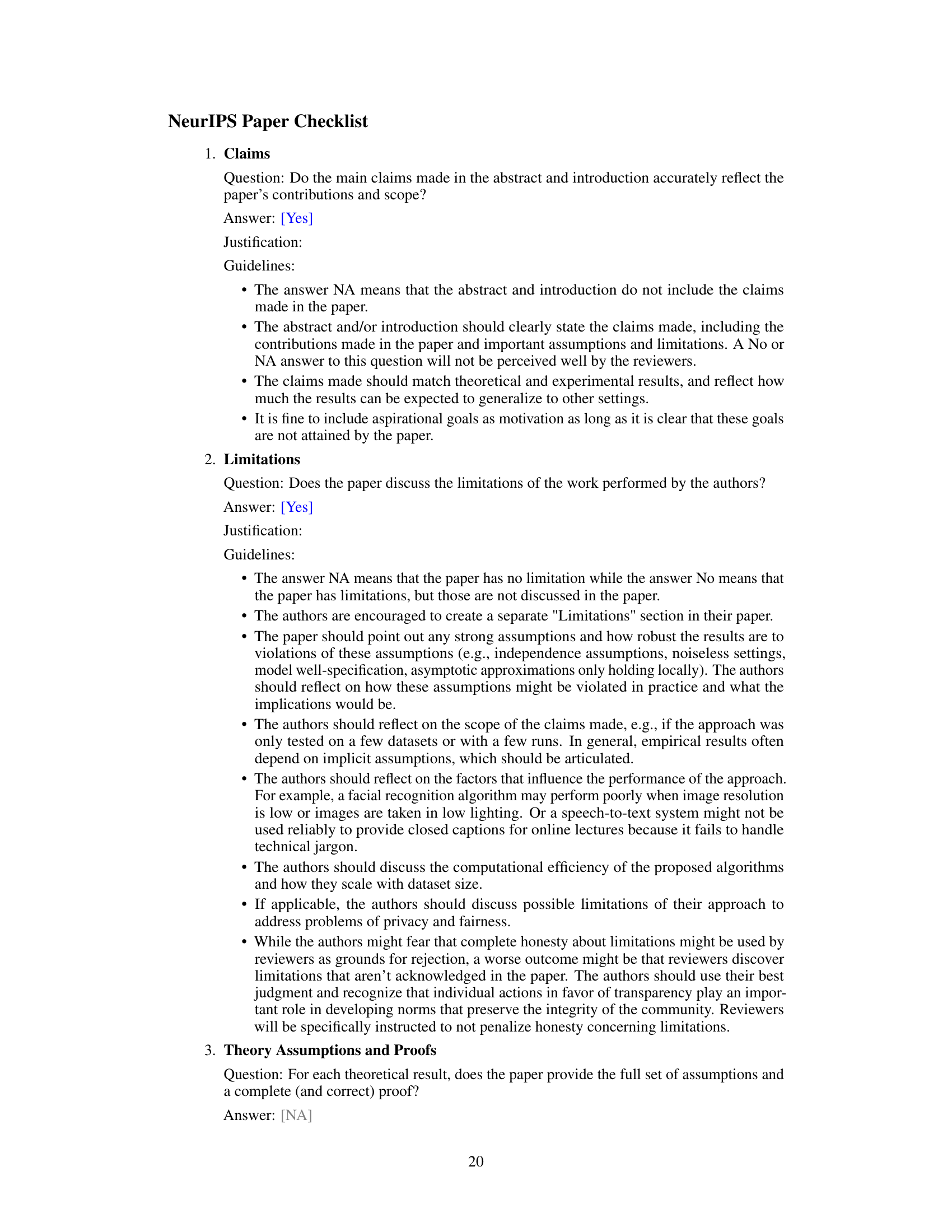

The figure illustrates the process of creating kernel stacks using a learned weight-sharing scheme. It starts with a set of flattened base kernels (represented as a stack of colored layers). These kernels are then transformed by a set of learnable doubly stochastic matrices (R₁, R₂, R₃, R₄), which act as soft permutation matrices. The result of these transformations is a reshaped kernel stack suitable for use in a convolutional layer. The visual shows the transformation from the original kernel layers to the permuted and then reshaped version. This weight sharing is the core concept of the proposed method to learn symmetries from data.

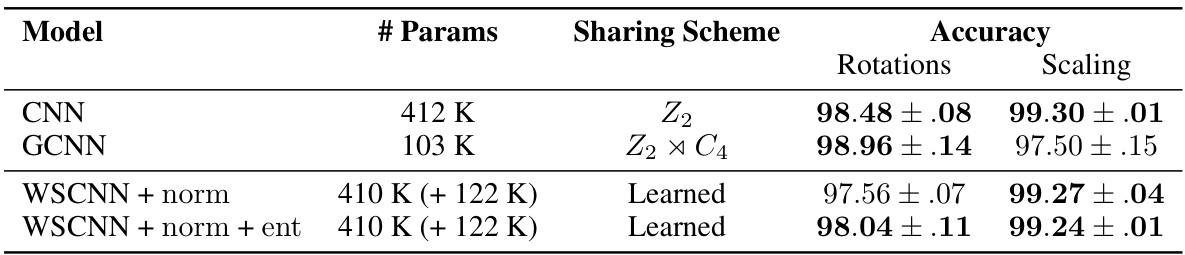

This table presents the test accuracy results on the MNIST dataset for models trained with rotation and scaling transformations. It compares the performance of a standard CNN, a group convolutional neural network (GCNN), and the proposed weight-sharing convolutional neural network (WSCNN) with and without normalization and entropy regularizers. The table shows the number of parameters, the type of weight-sharing scheme used (learned vs. predefined), and the accuracy achieved for both rotation and scaling tasks. Best-performing models (with accuracy within 1% of the top performer) are highlighted in bold. The additional parameters due to the weight-sharing mechanism are indicated with a (+).

In-depth insights#

Symmetry Learning#

Symmetry learning is a crucial area in machine learning, aiming to leverage inherent data symmetries for improved model generalization, efficiency, and robustness. Traditional approaches often rely on predefining specific symmetries, such as translation or rotation invariance, limiting their applicability to datasets without clear, known symmetries. This paper explores a novel, flexible approach that learns symmetries directly from data. Instead of enforcing strict group equivariance, it employs learnable doubly stochastic matrices to represent soft permutations of canonical weight tensors. This enables the model to discover and utilize both exact and partial symmetries, adapting effectively to various data characteristics. The method’s flexibility is a key advantage, allowing it to outperform rigid group convolution methods, particularly in scenarios with limited data or partial symmetries. By learning soft constraints rather than imposing fixed ones, this approach demonstrates potential for enhanced performance across a wider range of applications.

Doubly Stochastic#

The concept of “doubly stochastic” matrices plays a crucial role in the paper, serving as a bridge between the theoretical framework of group representations and the practical implementation of learnable weight-sharing schemes in neural networks. Doubly stochastic matrices, characterized by both row and column sums equaling one, naturally approximate the behavior of permutation matrices, which are central to representing group symmetries. By learning a collection of doubly stochastic matrices, the model effectively learns soft permutations of weights, allowing for flexibility in capturing both exact and approximate symmetries present in the data. This is a key innovation of the proposed method, as it elegantly avoids the limitations of traditional group-equivariant models that require predefined knowledge of the symmetries. The use of the Sinkhorn operator further enhances the method’s practicality, efficiently transforming any arbitrary matrix into a doubly stochastic one. This flexibility is particularly beneficial when dealing with real-world datasets where precise symmetries may not be readily apparent. Overall, the use of doubly stochastic matrices provides a powerful and efficient approach to learning symmetries directly from data.

Weight-Sharing Nets#

Weight-sharing neural networks offer a powerful mechanism to incorporate inductive biases into deep learning models, particularly concerning symmetry. Traditional methods often rely on pre-defined group symmetries, which might not accurately capture the complexities of real-world data. Weight-sharing nets address this limitation by learning the symmetries directly from the data, thereby adapting to various patterns and levels of symmetry present. This adaptive approach enhances model flexibility and generalization capabilities, potentially surpassing the performance of models that are constrained by pre-specified symmetries. By learning doubly stochastic matrices, the network effectively learns soft permutations of base weights, approximating group actions as a special case, and offering an efficient strategy for weight-sharing. This dynamic learning process is particularly valuable when handling partial or approximate symmetries, and offers the potential to discover meaningful structure in datasets where exact symmetries may be absent or unclear.

Partial Symmetry#

The concept of ‘partial symmetry’ in the context of deep learning is intriguing because it addresses the limitations of traditional methods that assume perfect, global symmetries in data. Real-world data often exhibits only approximate or localized symmetries, making rigid group-equivariant models overly restrictive and potentially hindering performance. Partial symmetry acknowledges this by allowing models to learn and exploit symmetries that may not be fully present or consistently applied across the entire dataset. This approach offers increased flexibility, as it avoids imposing strict constraints that could lead to overfitting or poor generalization. By learning soft constraints and partial mappings, instead of imposing hard-coded symmetries, models can better adapt to the nuances of complex data distributions. The key challenge lies in developing effective mechanisms for learning and representing these partial symmetries, perhaps through the use of learnable permutation matrices or probability distributions over group transformations. Successfully addressing this challenge would lead to more robust and data-efficient models that can effectively handle the complexity of real-world datasets.

Future Works#

The paper’s ‘Future Works’ section hints at several promising avenues. Improving computational efficiency is paramount, given the quadratic scaling with group size and kernel dimensions. Addressing this might involve exploring more efficient representations or approximations of the doubly stochastic matrices or leveraging hierarchical structures to share weights across layers. The current reliance on uniform representation stacks across channels limits the model’s ability to learn other transformations (like color jittering); developing more flexible, adaptive architectures is thus a key priority. Investigating methods to enhance the diversity of learned features and improve robustness against overfitting are also crucial. Finally, integrating the weight-sharing framework with established techniques like Cayley tensors could lead to more coherent group structures across layers and increase interpretability. This would also enable the approach to be more broadly applicable to learning symmetries in different domains and data types.

More visual insights#

More on figures

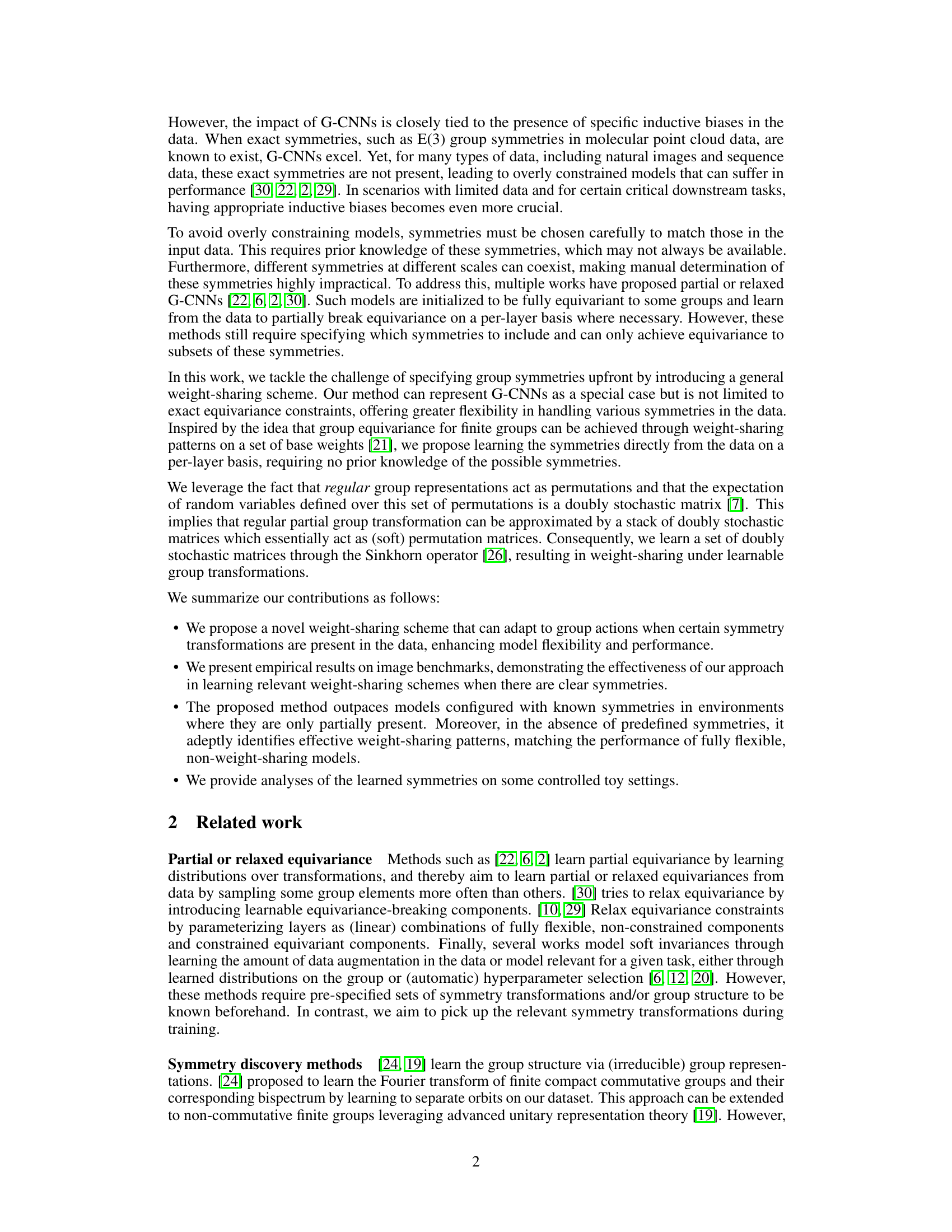

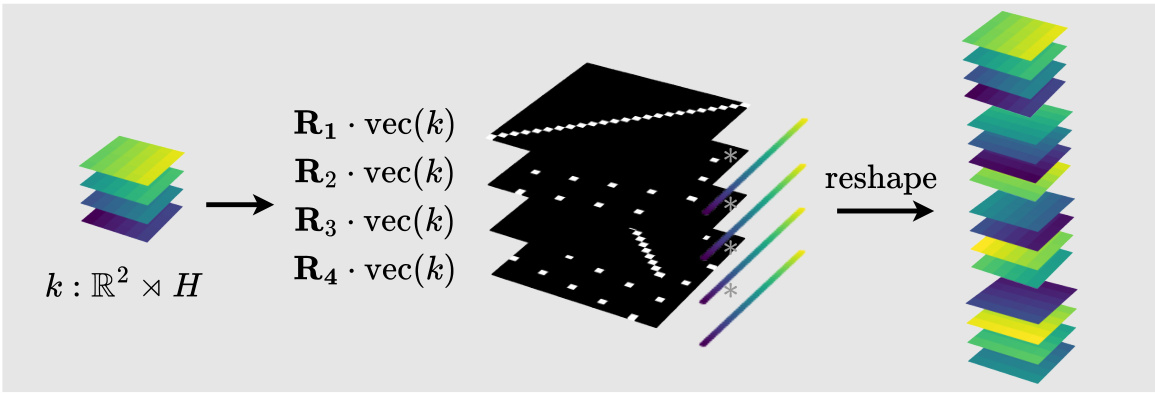

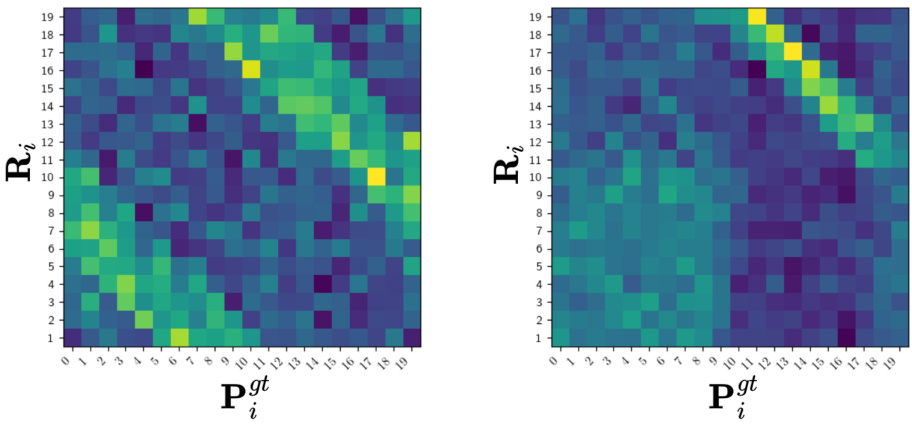

This figure compares the learned representations from the weight-sharing convolutional neural network (WSCNN) with the ground truth C4 representations for rotated MNIST data. The top row shows the learned representation matrices from the WSCNN’s lifting layer. The bottom row displays the true permutation matrices corresponding to the C4 group (cyclic rotations of 0, 90, 180, and 270 degrees) for a 25-dimensional data point (d=25). The comparison illustrates how well the WSCNN learns to approximate the C4 symmetry through its learnable weight-sharing scheme.

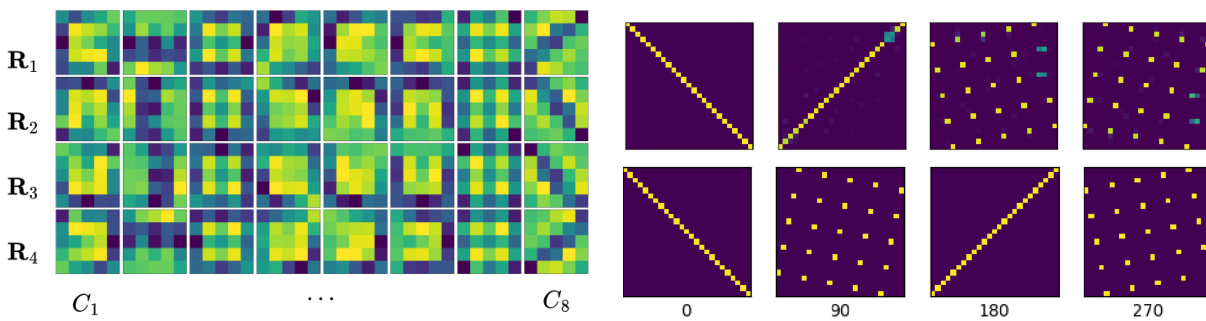

This figure shows example data and labels for two different tasks: an equivariant task and an invariant task. In the equivariant task (a), both the data and labels change according to the group action (in this case cyclic permutations), while in the invariant task (b), the labels remain unchanged regardless of the data transformation. This illustrates the difference in inductive biases used in modeling each scenario.

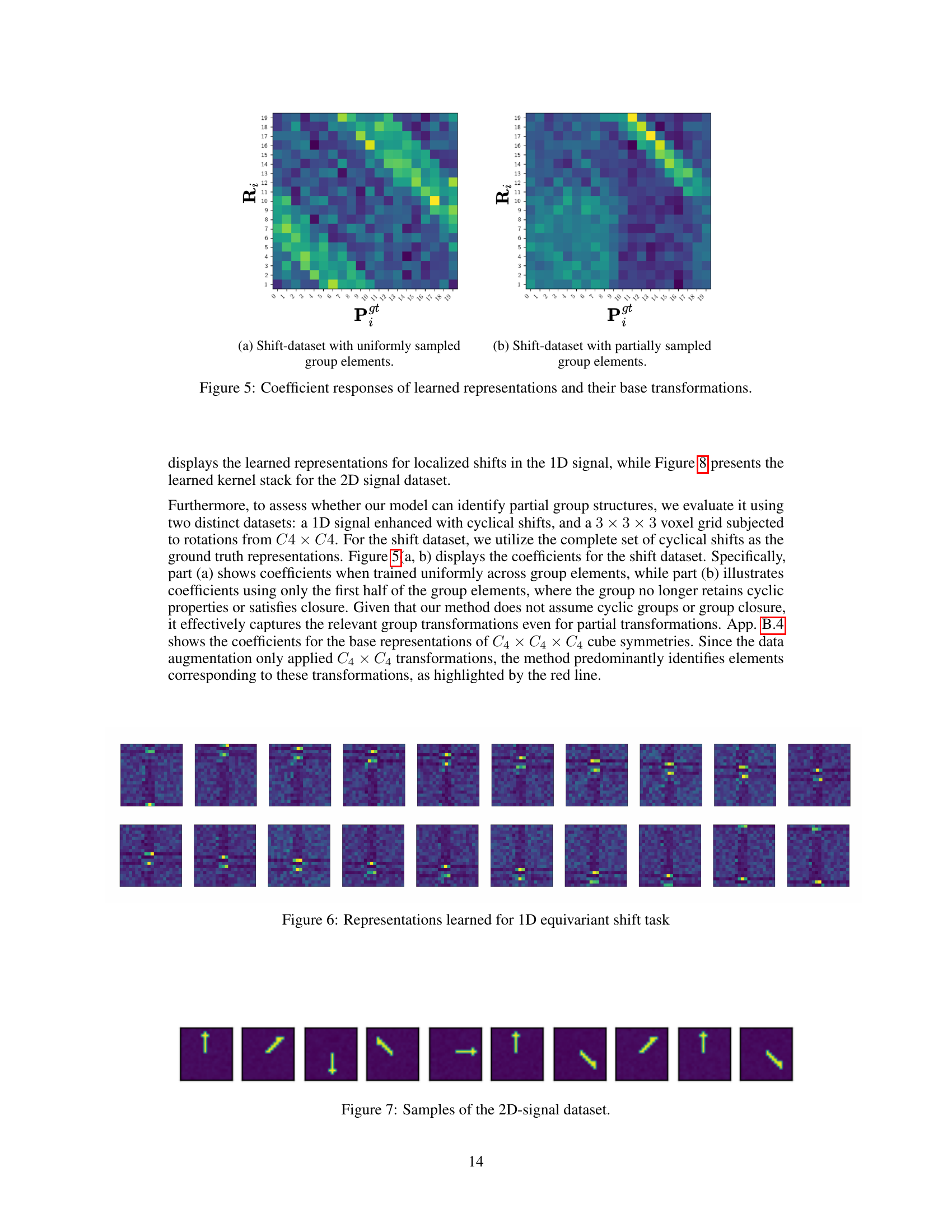

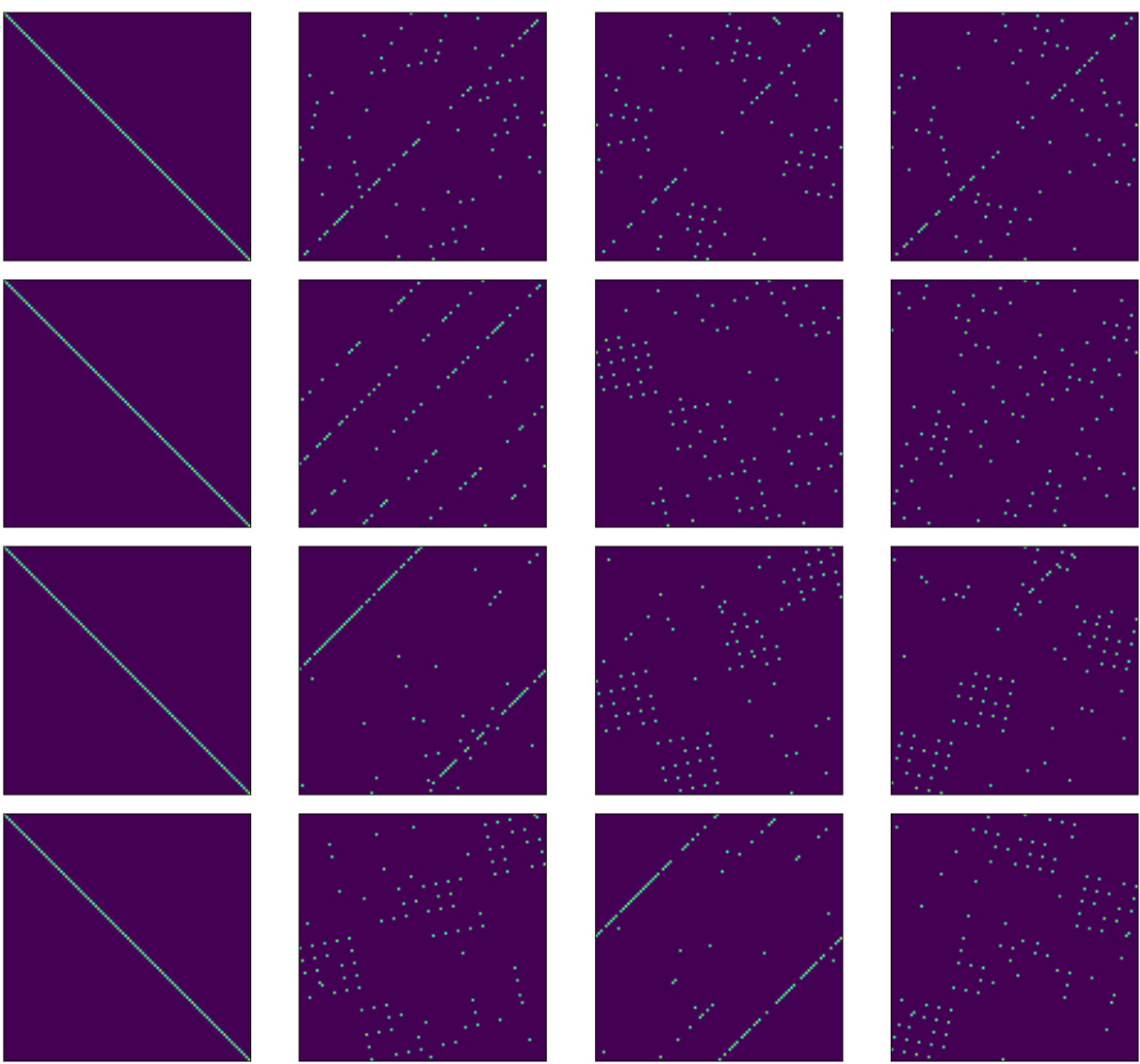

This figure visualizes the learned weight-sharing matrices (representations) and compares them to the ground truth permutation matrices for a dataset with cyclical shifts. Subfigure (a) shows the results when the model is trained with uniformly sampled group elements, resulting in a close match between the learned and ground truth representations. Subfigure (b) demonstrates the model’s ability to learn even when only a subset of the group elements are used during training. Despite the incomplete sampling, the learned representations still capture the underlying symmetry, indicating that the method is robust to partial or incomplete information.

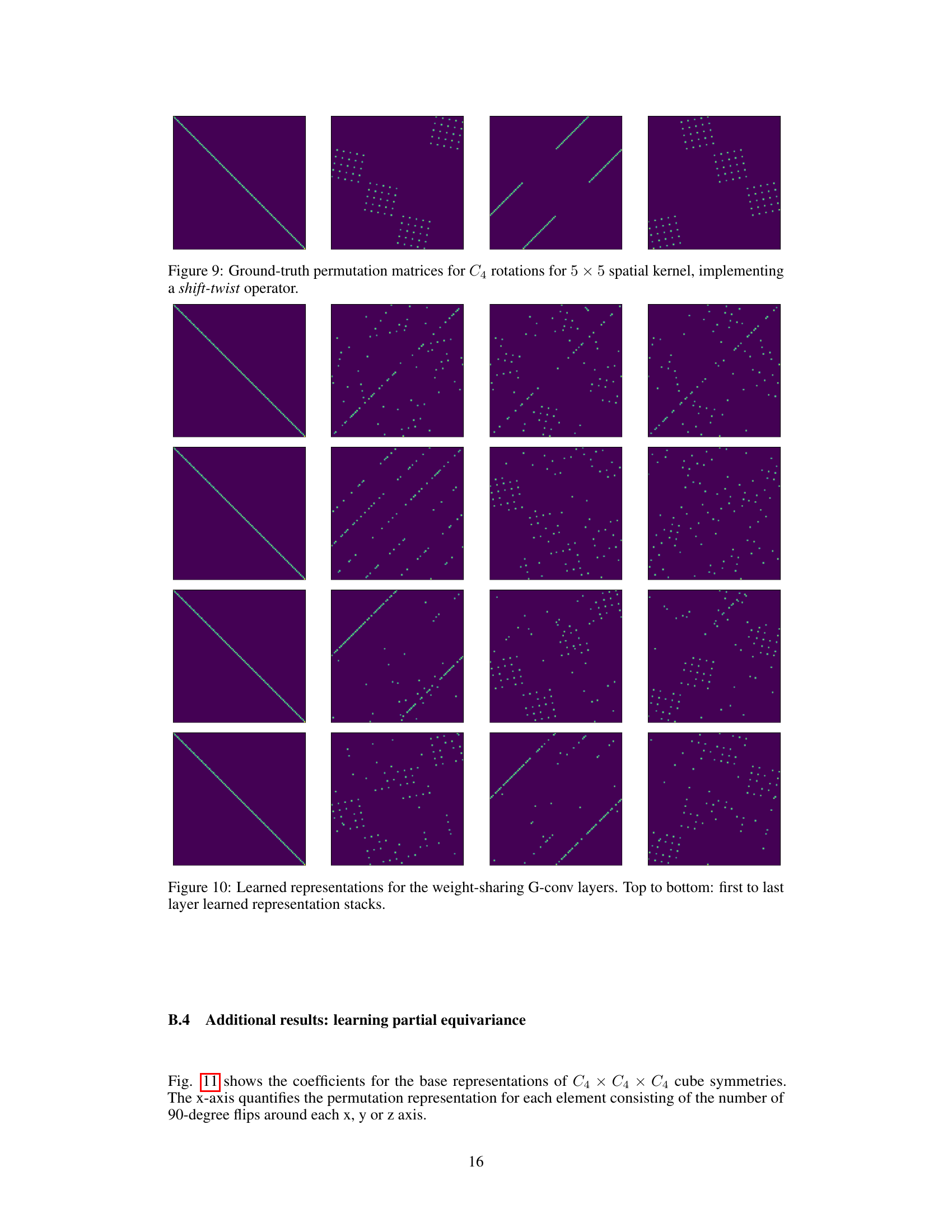

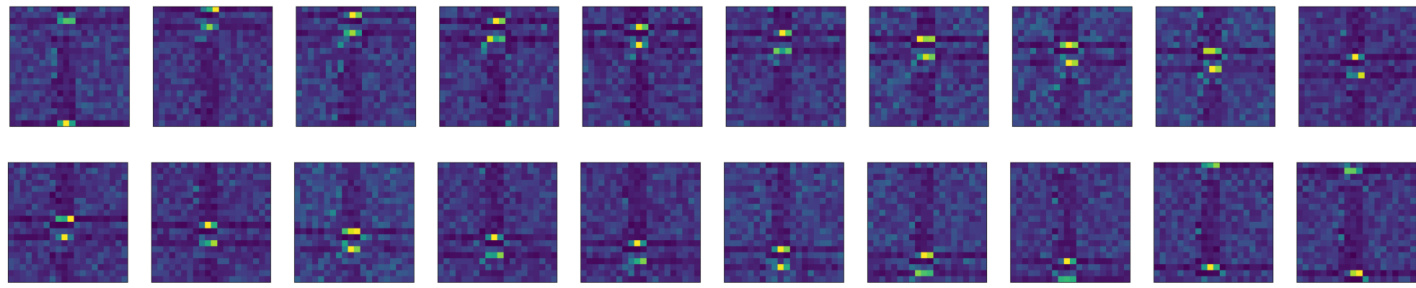

This figure visualizes the learned representation stacks for the weight-sharing G-convolutional layers. Each image represents a layer’s learned weight-sharing scheme. The arrangement from top to bottom corresponds to the order of the layers in the network. The color intensity within each image indicates the strength of the learned weight-sharing connections.

This figure shows sample images from the 2D signal dataset used in the paper’s experiments. The images depict various rotations of a basic pattern, illustrating the types of symmetries the model is trained to recognize. The specific pattern is a stylized snowflake-like shape. These examples highlight the complexity and variety within the dataset, demonstrating the challenge of learning symmetries without prior knowledge of the exact transformations.

This figure shows the learned weight-sharing matrices for the G-convolutional layers of the proposed Weight Sharing Convolutional Neural Networks (WSCNNs). Each matrix represents a learned transformation (permutation matrix) applied to the base kernels of each layer. The figure visualizes how these matrices evolve from the first layer (top) to the last layer (bottom), illustrating how the network dynamically discovers effective weight sharing schemes across different layers.

This figure shows the learned weight-sharing matrices (representations) in the G-convolution layers of the proposed WSCNN model. The matrices visualize how the model learned to share weights across different group transformations during training. The progression from top to bottom indicates the evolution of these learned representations across the layers of the network. The representation matrices are a key element to the WSCNN’s ability to adaptively learn symmetries.

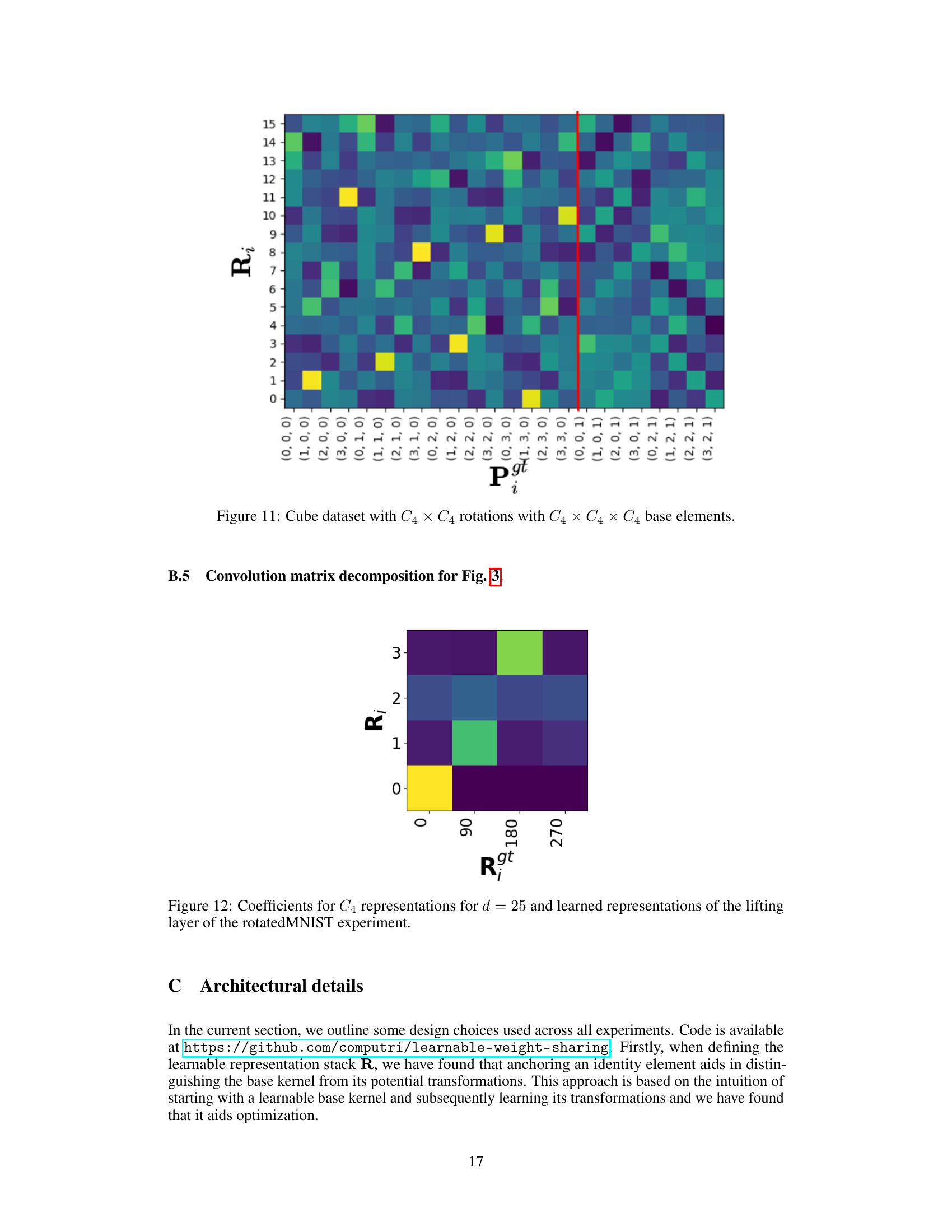

This figure visualizes the learned representations for a cube dataset subjected to C4 × C4 rotations. The x-axis represents the base elements (transformations) of the C4 × C4 × C4 group, and the y-axis represents the indices of the learned representation matrix R. The heatmap shows the coefficients of the learned representation, highlighting which base elements are most prominent in each part of the representation. A red line is drawn to show where the learned representation closely aligns with the applied transformations.

This figure compares the learned representations from the weight-sharing convolutional neural network (WSCNN) model with the ground truth C4 representations. The top row shows the learned representations from the WSCNN model’s lifting layer, while the bottom row displays the true C4 group permutations for a data dimension of 25. The visualization helps to assess how well the learned weight sharing scheme approximates the known symmetries of the C4 group.

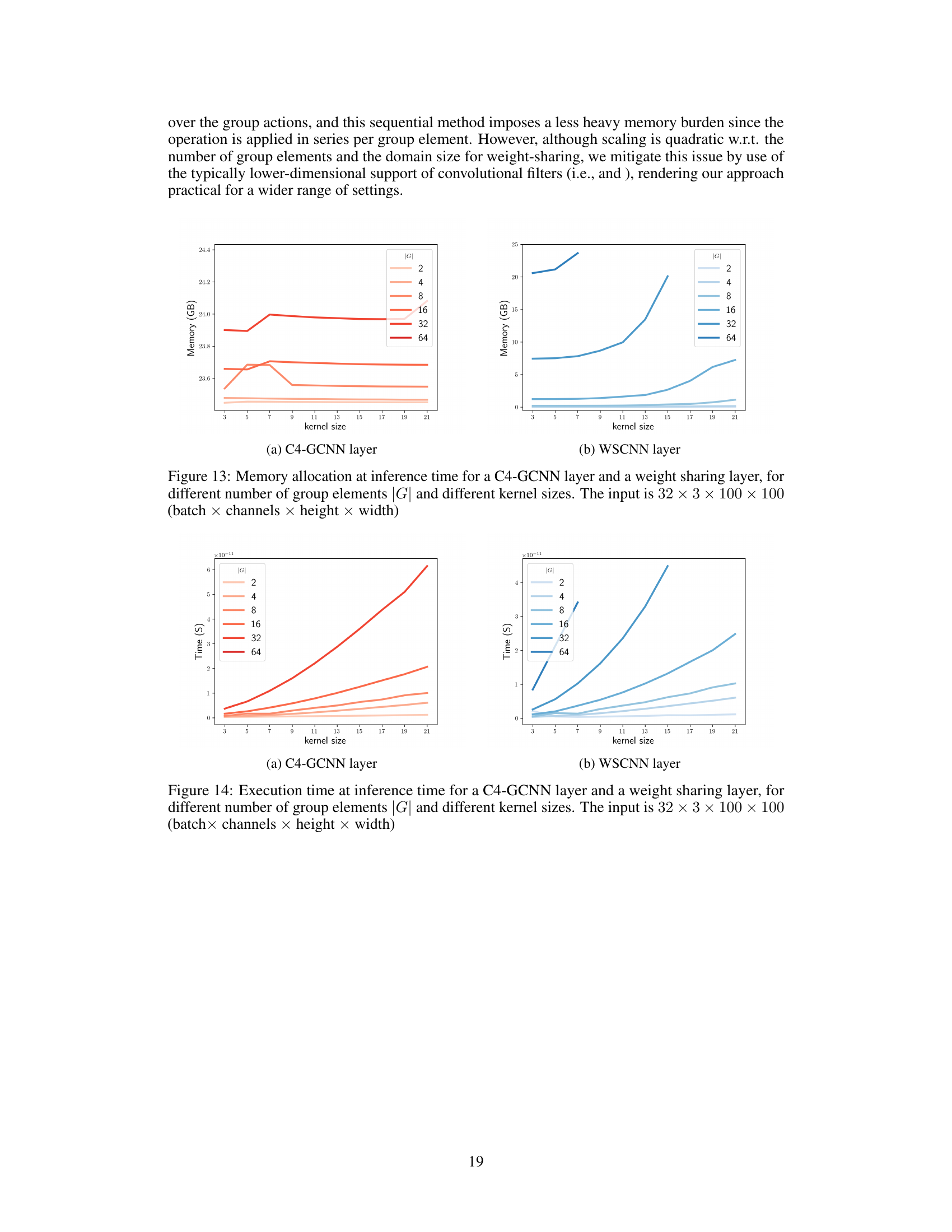

This figure compares the memory usage of C4-GCNN and WSCNN layers during inference. It shows how memory consumption varies with the number of group elements (|G|) and kernel size. The input tensor dimensions are consistent across all scenarios (32 batches, 3 channels, 100x100 height and width). The plots reveal that the WSCNN layer generally requires less memory than the C4-GCNN layer, especially as the number of group elements and kernel size increases.

This figure compares the memory usage of a C4-GCNN layer and a weight-sharing layer at inference time. The comparison is shown for various numbers of group elements (|G|) and kernel sizes. The input data has dimensions 32 x 3 x 100 x 100, representing batch size, channels, height, and width respectively. The results demonstrate that the memory usage scales differently for the two methods with changes in the number of group elements and kernel size.

More on tables

This table presents the test accuracy results on the MNIST dataset for models trained with rotation and scaling transformations. It compares a standard CNN, a Group Convolutional Neural Network (GCNN), and the proposed Weight Sharing Convolutional Neural Network (WSCNN) with and without entropy and normalization regularizers. The number of parameters, the weight-sharing scheme used (learned vs. predefined), and the accuracy for both rotations and scaling are shown. Best-performing models are highlighted in bold.

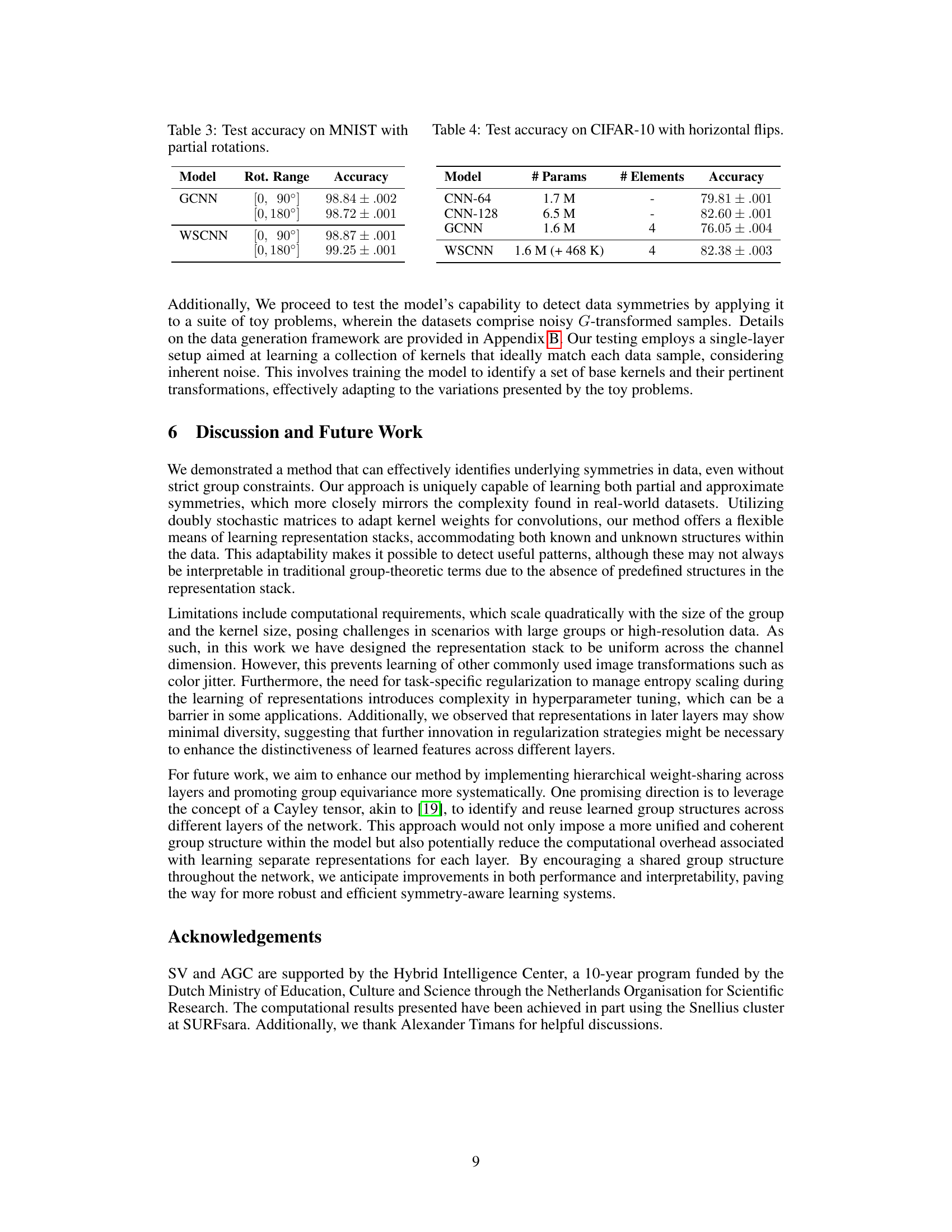

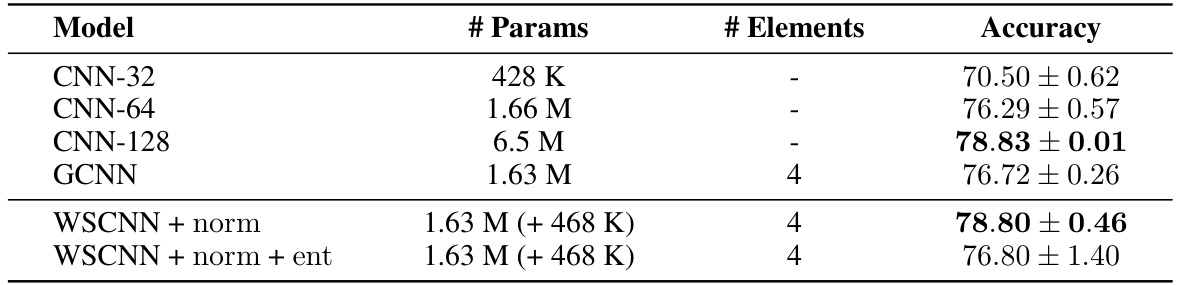

This table presents the test accuracy results on the CIFAR-10 dataset for various models. It compares a standard CNN with different numbers of parameters, a group convolutional neural network (GCNN), and the proposed weight-sharing convolutional neural network (WSCNN) with and without different regularizations. The number of elements in GCNN and WSCNN indicates the size of the group used for the group convolution. The table highlights that the WSCNN achieves comparable performance to the best-performing CNN while using significantly fewer parameters.

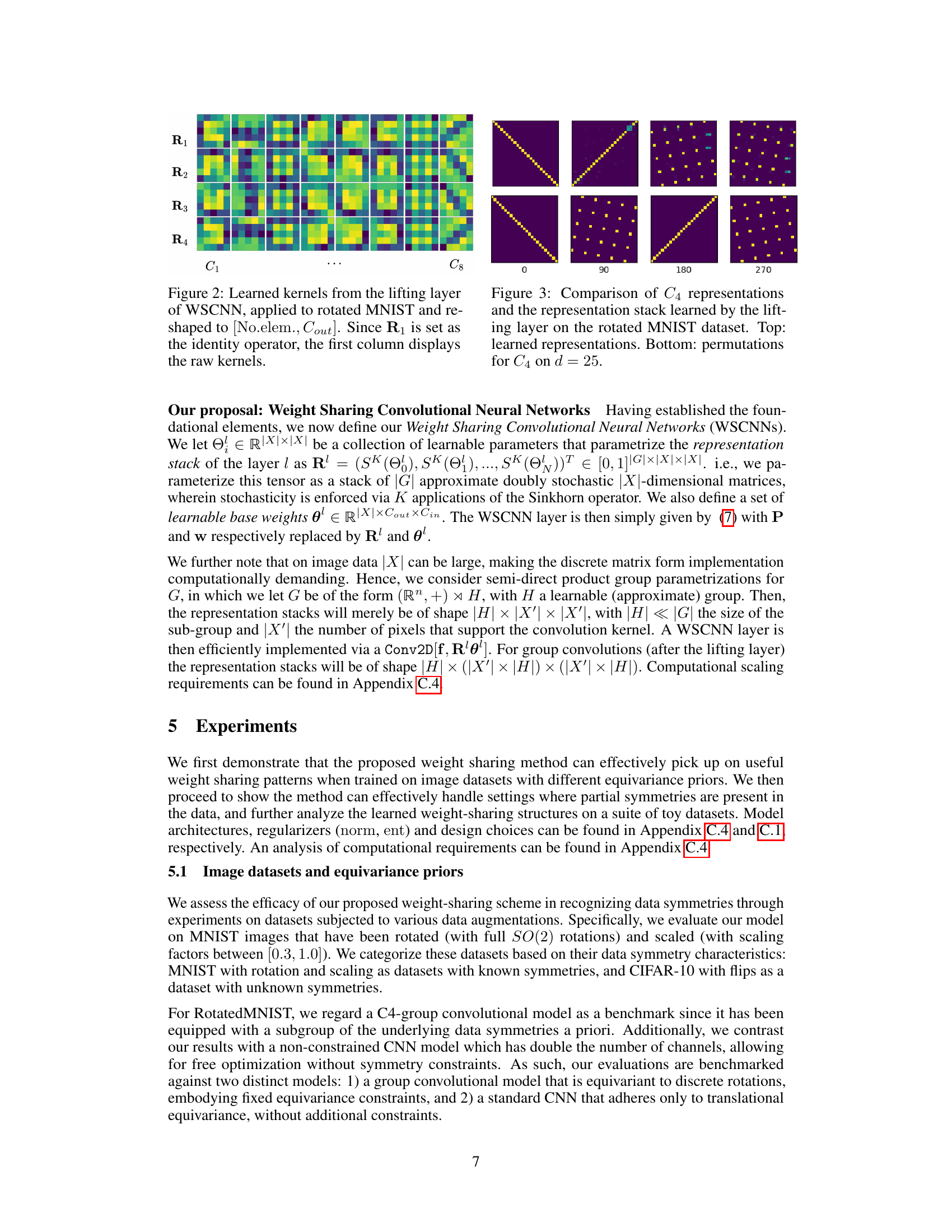

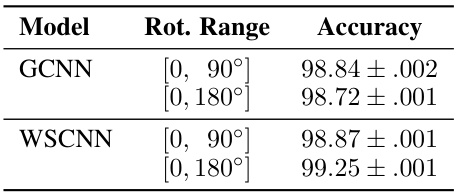

This table presents the test accuracy results on the MNIST dataset for different rotation ranges. The model’s performance is evaluated using two different rotation ranges: [0, 90°] and [0, 180°]. The table compares the accuracy of two models: GCNN and WSCNN, showcasing how well they perform under varying levels of symmetry.

This table presents the test accuracy results on the CIFAR-10 dataset for different models: a standard CNN with varying numbers of parameters, a group convolutional neural network (GCNN) with 4 group elements, and the proposed weight-sharing convolutional neural network (WSCNN) also with 4 group elements. The table highlights the number of parameters for each model, indicating the additional parameters introduced by the weight-sharing mechanism in WSCNN. The best performing models (within 1% accuracy difference) are marked in bold, allowing for a direct comparison of performance.

Full paper#