↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Structure-based drug design (SBDD) traditionally assumes rigid proteins, limiting its effectiveness. This simplification leads to inaccurate predictions and lower-quality drug candidates because real-world protein-ligand interactions involve significant conformational changes. Many existing methods fall short in modeling this flexibility, hindering the discovery of more effective drugs.

FlexSBDD is a new deep generative model designed to overcome these issues. It efficiently models flexible protein-ligand interactions, using a novel approach that leverages a flow matching framework and E(3)-equivariant neural networks. The model’s performance significantly outperforms existing methods in generating high-affinity molecules, demonstrates increased favorable interactions, and reduces steric clashes. A case study on KRASG12C further highlights its potential for identifying novel drug targets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical limitation in structure-based drug design (SBDD): the rigid protein assumption. By introducing FlexSBDD, a deep generative model that accounts for protein flexibility, the research opens new avenues for discovering high-affinity drugs and provides a novel approach to SBDD. The state-of-the-art results achieved demonstrate its potential to significantly impact drug discovery.

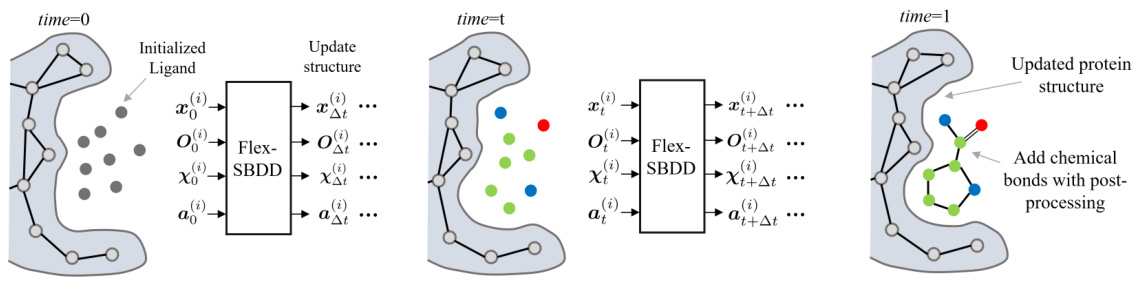

Visual Insights#

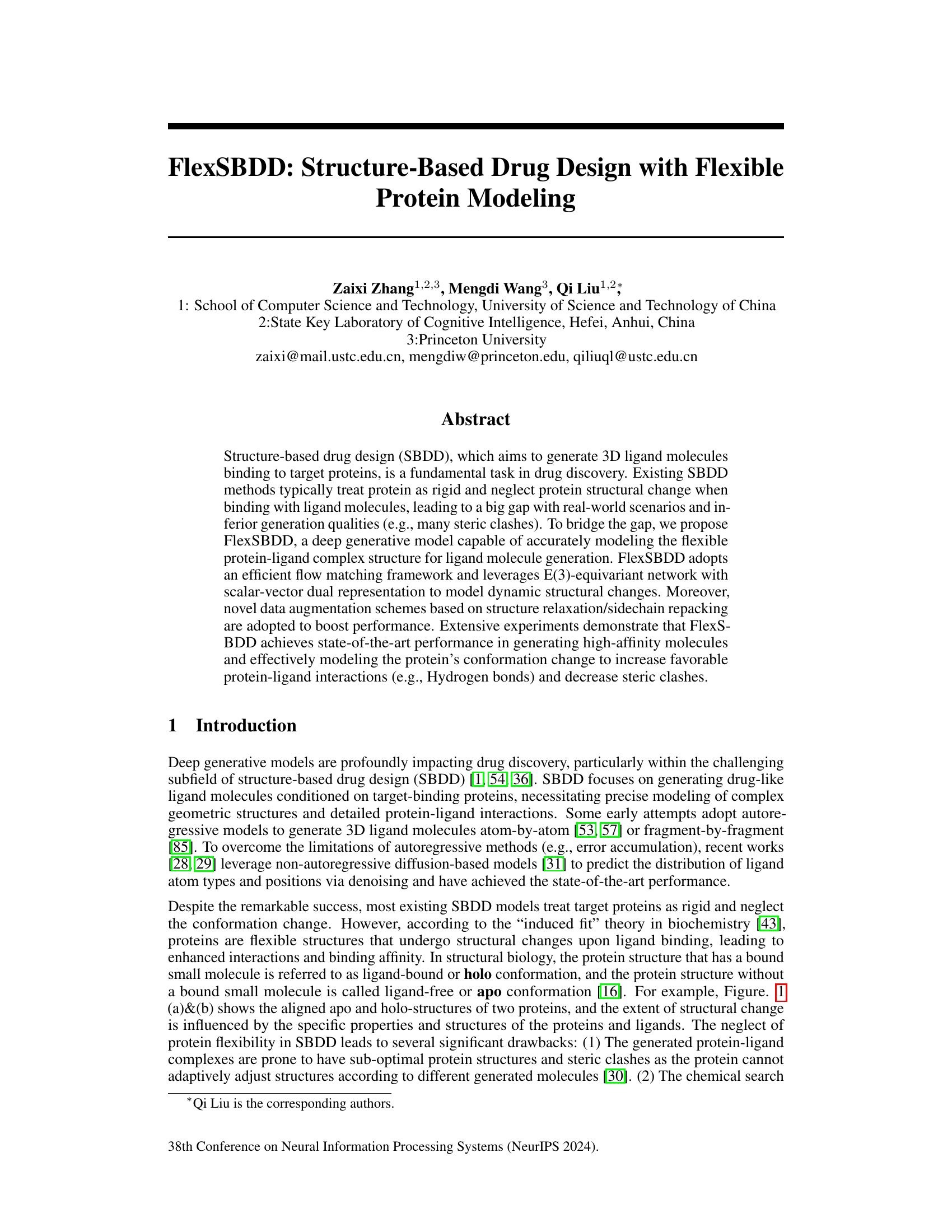

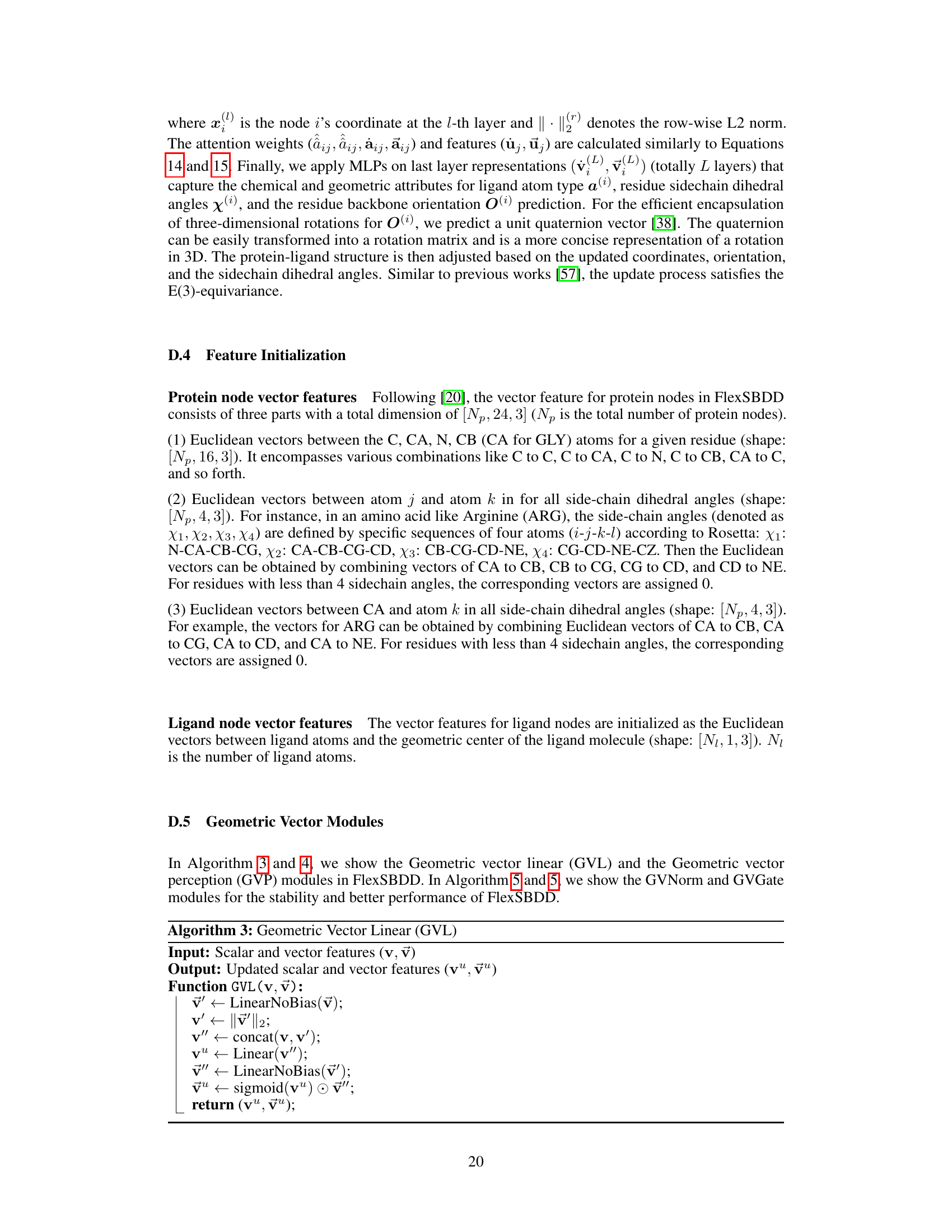

This figure shows two examples of aligned apo (ligand-free) and holo (ligand-bound) protein structures. The first example is Human Glutathione S-Transferase protein (PDB ID: 10GS), and the second example is Human Menkes protein (PDB ID: 2KMX). The apo structures are shown in magenta, the holo structures in cyan, and the bound ligands are orange. A third subfigure illustrates how the protein structure and ligand molecule are parameterized for the model.

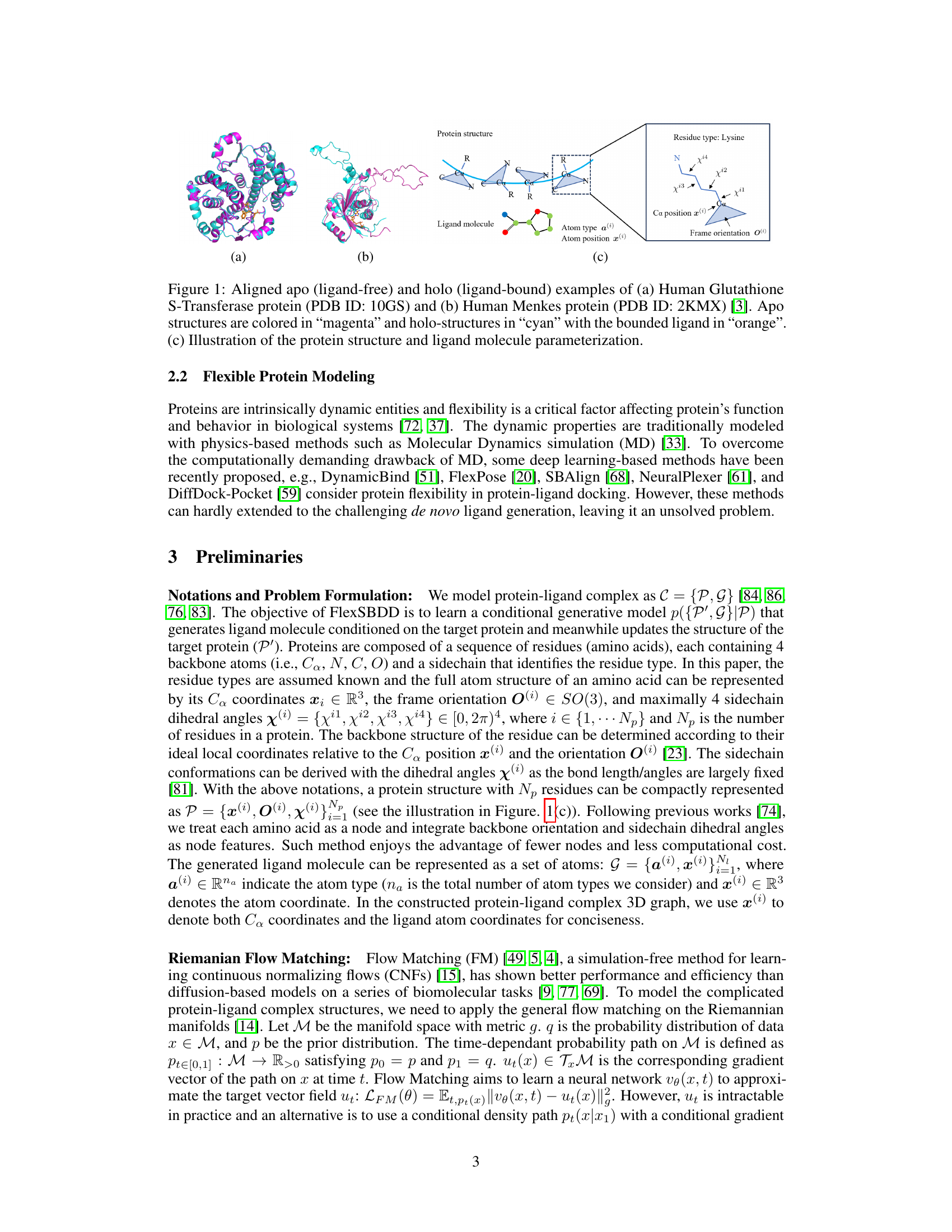

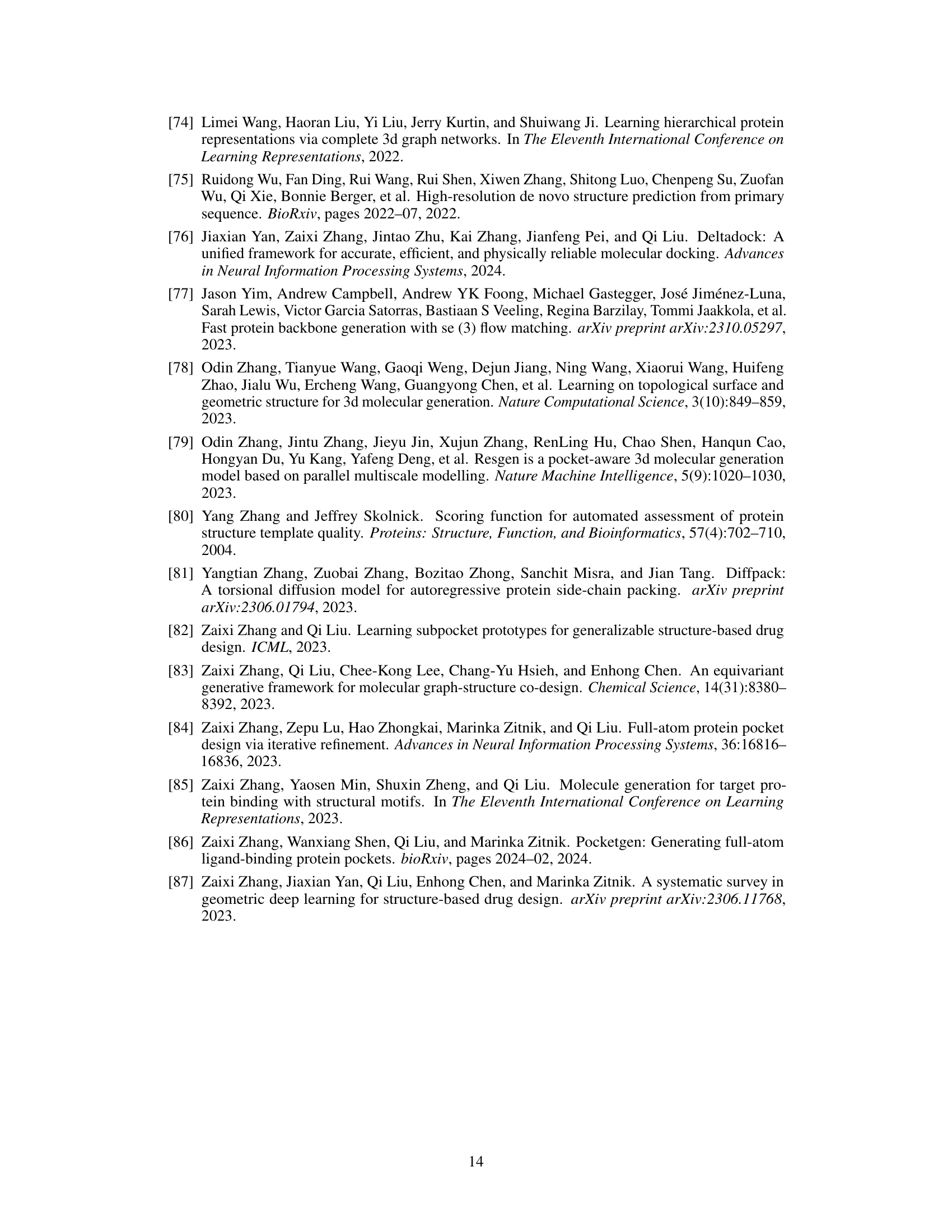

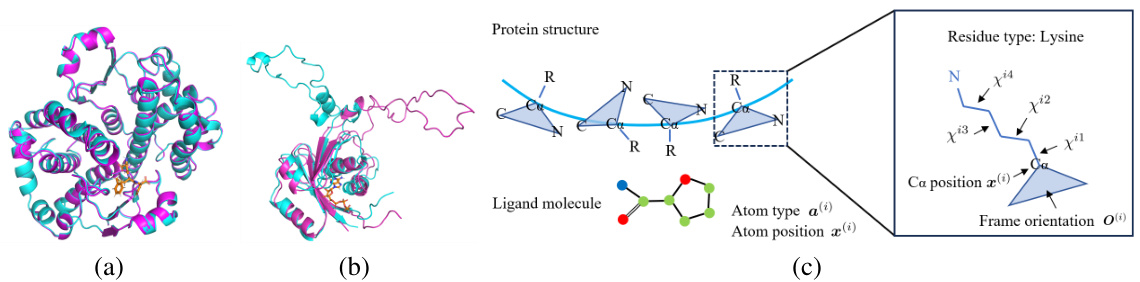

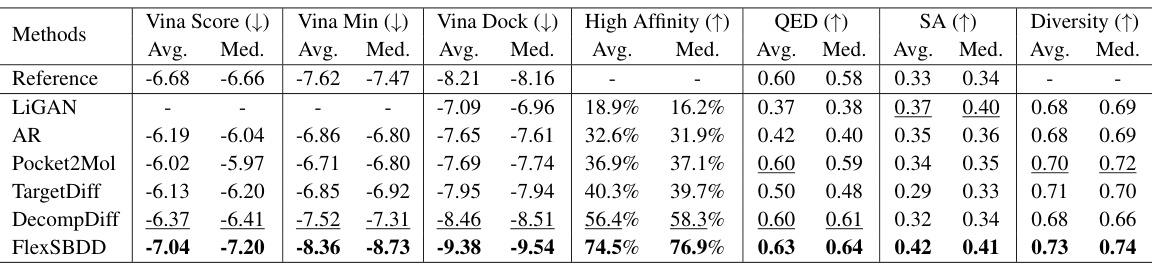

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different methods in generating molecules on the CrossDocked dataset. It evaluates the generated molecules based on various properties, including binding affinity (Vina Score, Vina Min, Vina Dock), the percentage of generated molecules with higher binding affinity than the reference (High Affinity), drug-likeness (QED), synthetic accessibility (SA), and diversity. Lower Vina scores, Vina Min, and Vina Dock indicate stronger binding affinity, while higher High Affinity, QED, SA, and Diversity are desirable.

In-depth insights#

Flexible Protein Modeling#

The concept of ‘Flexible Protein Modeling’ in drug design is crucial because proteins are not static entities; their conformations change upon ligand binding. Traditional structure-based drug design (SBDD) often simplifies this by treating proteins as rigid, which limits the accuracy and diversity of generated drug candidates. Flexible modeling addresses this by incorporating protein flexibility, enabling the generation of molecules that better interact with the dynamic protein target. This is achieved through various computational techniques including molecular dynamics simulations or deep learning-based methods that capture protein conformational changes during ligand interaction. Accurate prediction of these changes is essential for improving the success rate of drug discovery, helping generate higher-affinity, more selective, and less prone-to-failure drug candidates. The challenge lies in computational cost and the need for sufficient high-quality data for training the models. The development of efficient, robust and accurate methods for flexible protein modeling remains a key area of ongoing research within SBDD.

Flow Matching Framework#

A flow matching framework offers a compelling alternative to diffusion models for generative tasks, particularly in complex domains like molecular design. Its strength lies in its efficiency: eschewing the iterative denoising process of diffusion, it directly learns a mapping between a simple prior distribution and the complex target data distribution. This direct approach leads to faster generation times and reduces computational costs. The framework’s flexibility is also noteworthy, allowing adaptation to various data modalities and manifold structures through appropriate choice of distance metrics and optimization techniques. While theoretically elegant, successful implementation requires careful consideration of the underlying probability distributions and the selection of appropriate neural network architectures for accurate modeling of the learned mapping. A key advantage is its simulation-free nature, avoiding the computational expense associated with methods like molecular dynamics simulations. The effectiveness hinges on efficiently learning and implementing the mapping in high-dimensional spaces, demanding robust and efficient algorithms capable of handling the complex geometries involved in many applications.

E(3)-Equivariant Network#

Employing an E(3)-equivariant network offers a significant advantage in processing 3D data, such as protein structures and ligand molecules, because it inherently encodes rotation and translation invariance. This means the network’s output is consistent regardless of the input’s orientation or position in space. This is particularly crucial for structure-based drug design (SBDD) where the relative spatial arrangement of atoms is paramount, and minor changes in orientation can affect binding affinity. By leveraging this property, the model avoids learning redundant representations for rotated or translated versions of the same molecule, leading to improved efficiency and generalization. The network can learn more robust and transferable features, making it better at predicting high-affinity molecule candidates. Moreover, this approach likely reduces the need for extensive data augmentation which would be otherwise needed to account for various orientations of input data.

Cryptic Pocket Discovery#

Cryptic pockets, hidden binding sites on proteins, are challenging to discover using traditional methods. Computational approaches like the one presented in the research paper offer a powerful way to identify these elusive sites. By modeling protein flexibility and simulating ligand binding, such methods can reveal pockets that are only formed upon ligand interaction. The study of cryptic pockets is crucial because they represent potential drug targets that were previously inaccessible, offering opportunities for novel drug design and development. Deep generative models, employing techniques such as flow-matching and equivariant networks, have shown promising results in accurately predicting these cryptic binding sites. This approach surpasses previous limitations of rigid protein modeling by explicitly incorporating protein conformational changes. However, challenges remain, including the computational expense of these methods and the need for high-quality training datasets. Furthermore, careful consideration must be given to the validation of predicted cryptic pockets, ensuring that the predictions accurately reflect real-world scenarios and avoid false positives.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore improving efficiency by developing more sophisticated flow matching techniques or leveraging alternative generative models. Expanding the scope to encompass diverse drug modalities beyond small molecules, including peptides and antibodies, presents a significant challenge and opportunity. Furthermore, investigating cryptic pockets in more detail, potentially integrating protein dynamics simulations, is crucial for unlocking novel drug targets. Addressing the limitations of the current dataset through extensive data augmentation or developing new experimental techniques that explicitly model protein flexibility and protein-ligand interaction dynamics would significantly benefit future work. Finally, generalizing FlexSBDD to model a wider range of protein-ligand interactions and other biomolecular systems, including enzyme-substrate interactions, will be paramount in advancing the field.

More visual insights#

More on figures

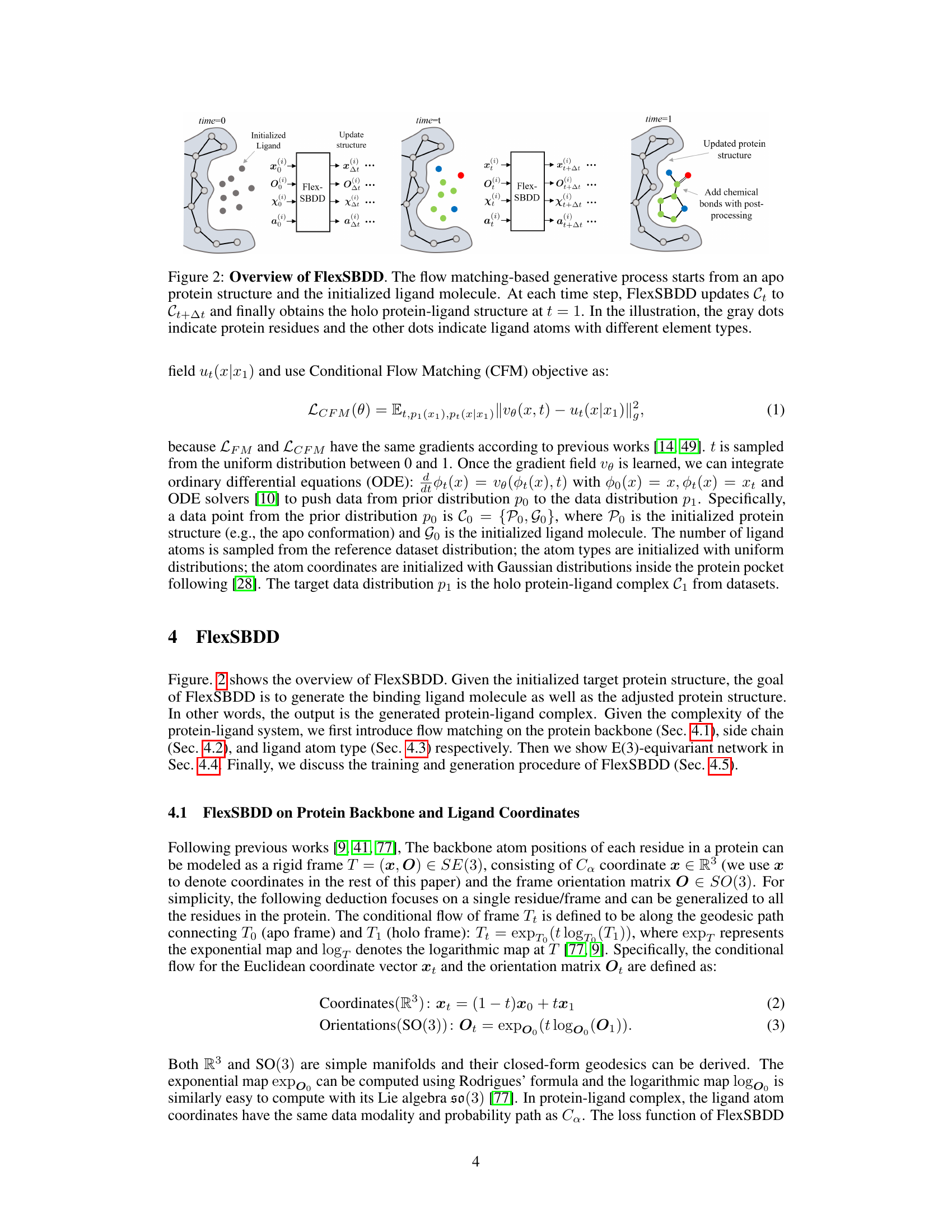

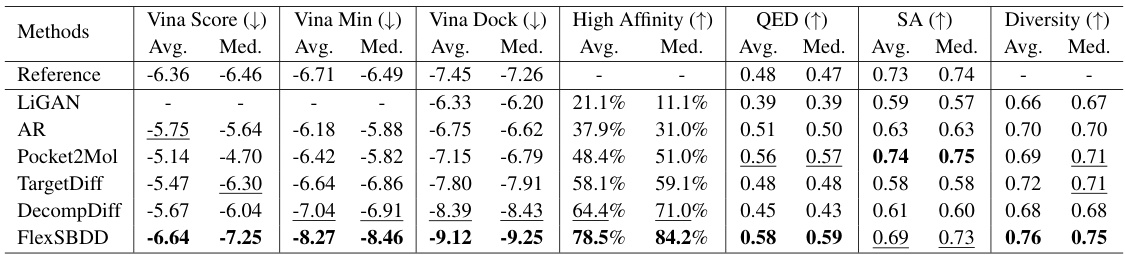

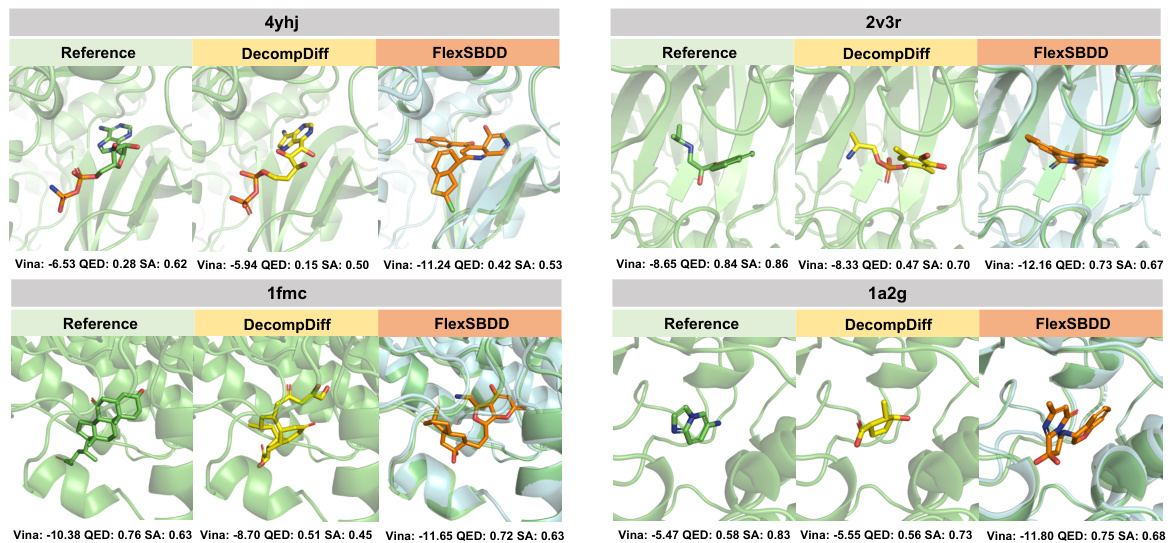

This figure illustrates the overall process of FlexSBDD. It starts with an apo protein structure (no ligand bound) and an initialized ligand molecule. FlexSBDD iteratively updates both the protein structure and ligand at each time step, using a flow-matching based approach. The process continues until time=1, at which point the model outputs an updated holo protein-ligand complex (ligand bound). The figure visually depicts this process by showing the protein and ligand structures at time=0, time=t (during the iteration), and time=1, emphasizing the structural changes.

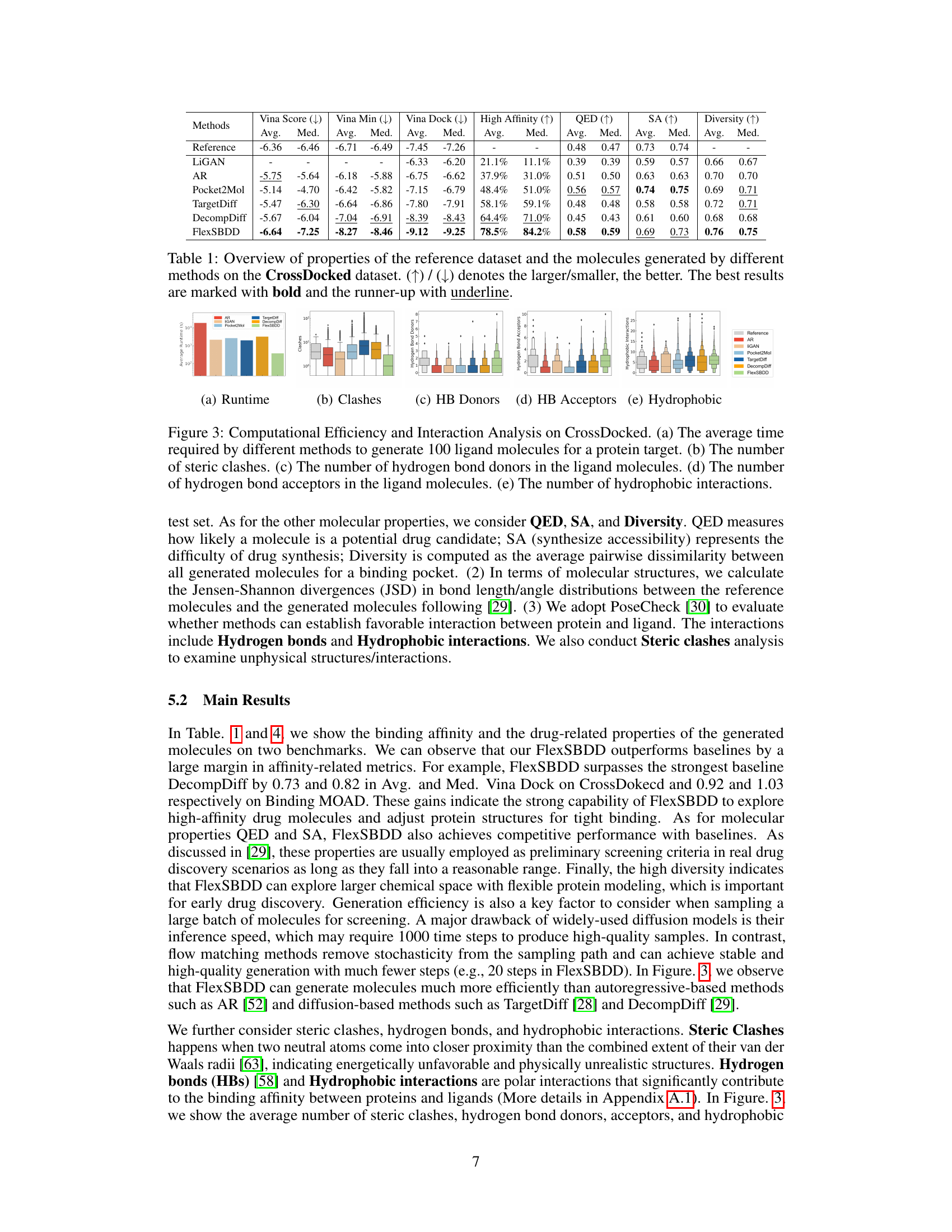

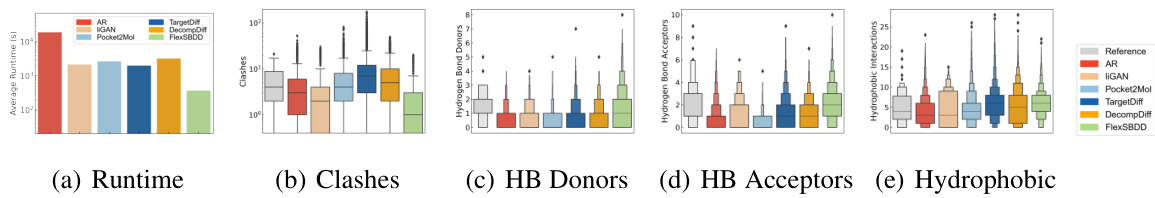

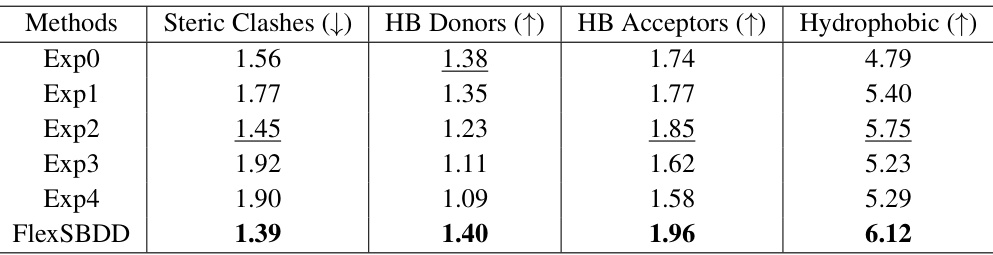

This figure compares several metrics across different methods for structure-based drug design (SBDD) using the CrossDocked dataset. Panel (a) shows the average runtime for generating 100 ligand molecules. Panels (b) through (e) illustrate the number of steric clashes, hydrogen bond donors, hydrogen bond acceptors, and hydrophobic interactions, respectively, providing insights into the quality and druggability of generated molecules.

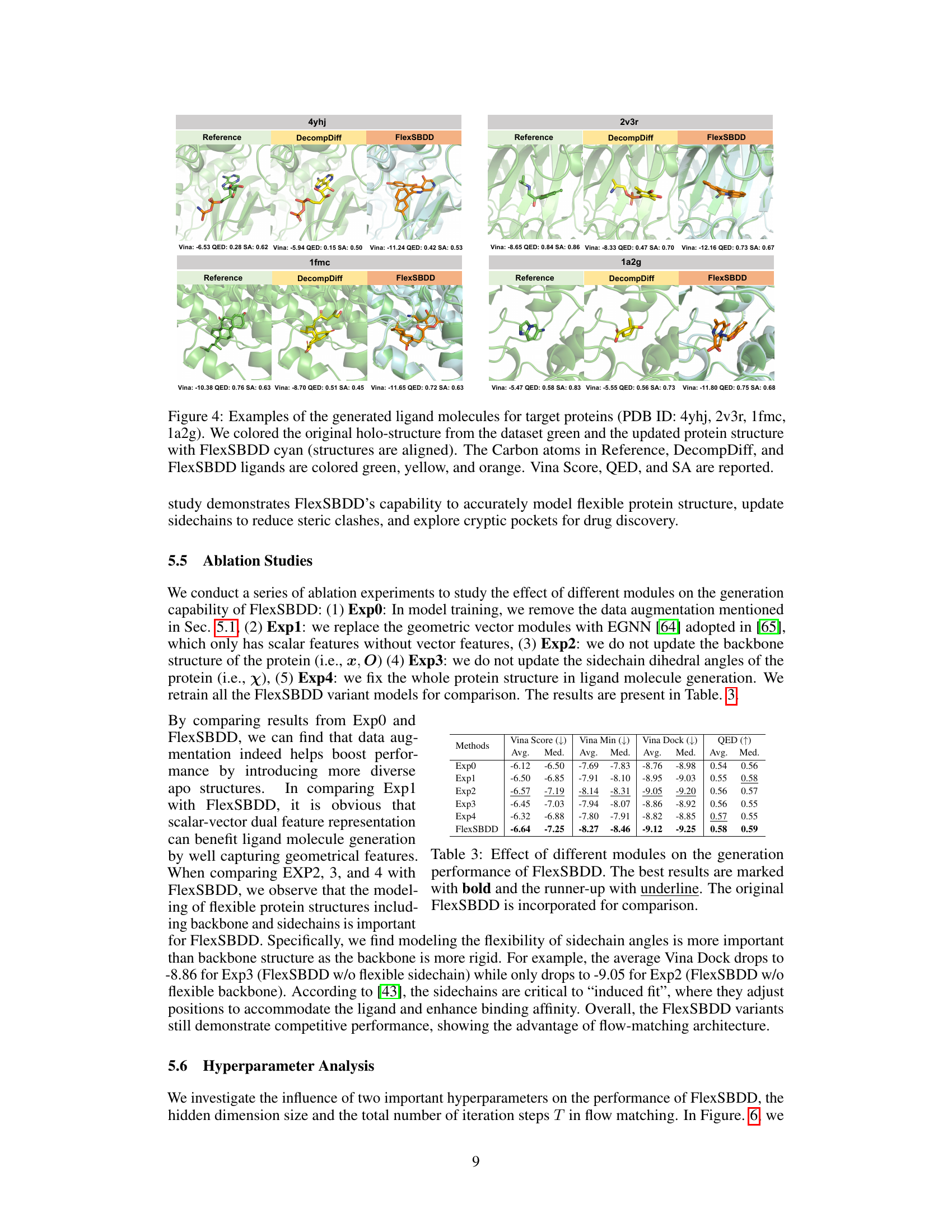

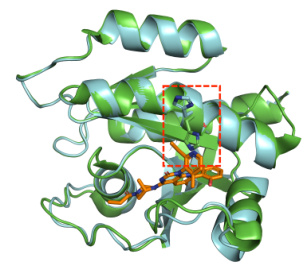

This figure shows four examples of generated ligand molecules for different target proteins. Each example includes the original holo protein structure (green), a protein structure generated using DecompDiff (yellow), and a protein structure generated using FlexSBDD (cyan). The carbon atoms of the ligands in all three structures are colored according to which method generated them (green for reference, yellow for DecompDiff, and orange for FlexSBDD). The figure also provides the Vina Score, QED, and SA values for each ligand, allowing for a comparison of the results from each method.

This figure showcases examples of ligand molecules generated by FlexSBDD for four different target proteins. It compares the generated molecules (FlexSBDD) with the reference molecules from the dataset and those generated by DecompDiff, a competing method. The visualization highlights the protein structures (original holo structures in green and FlexSBDD-updated structures in cyan), and ligand molecules (reference in green, DecompDiff in yellow, and FlexSBDD in orange). Key metrics like Vina Score, QED (Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness), and SA (synthetic accessibility) are provided for each generated molecule, illustrating FlexSBDD’s ability to generate high-affinity molecules with improved properties.

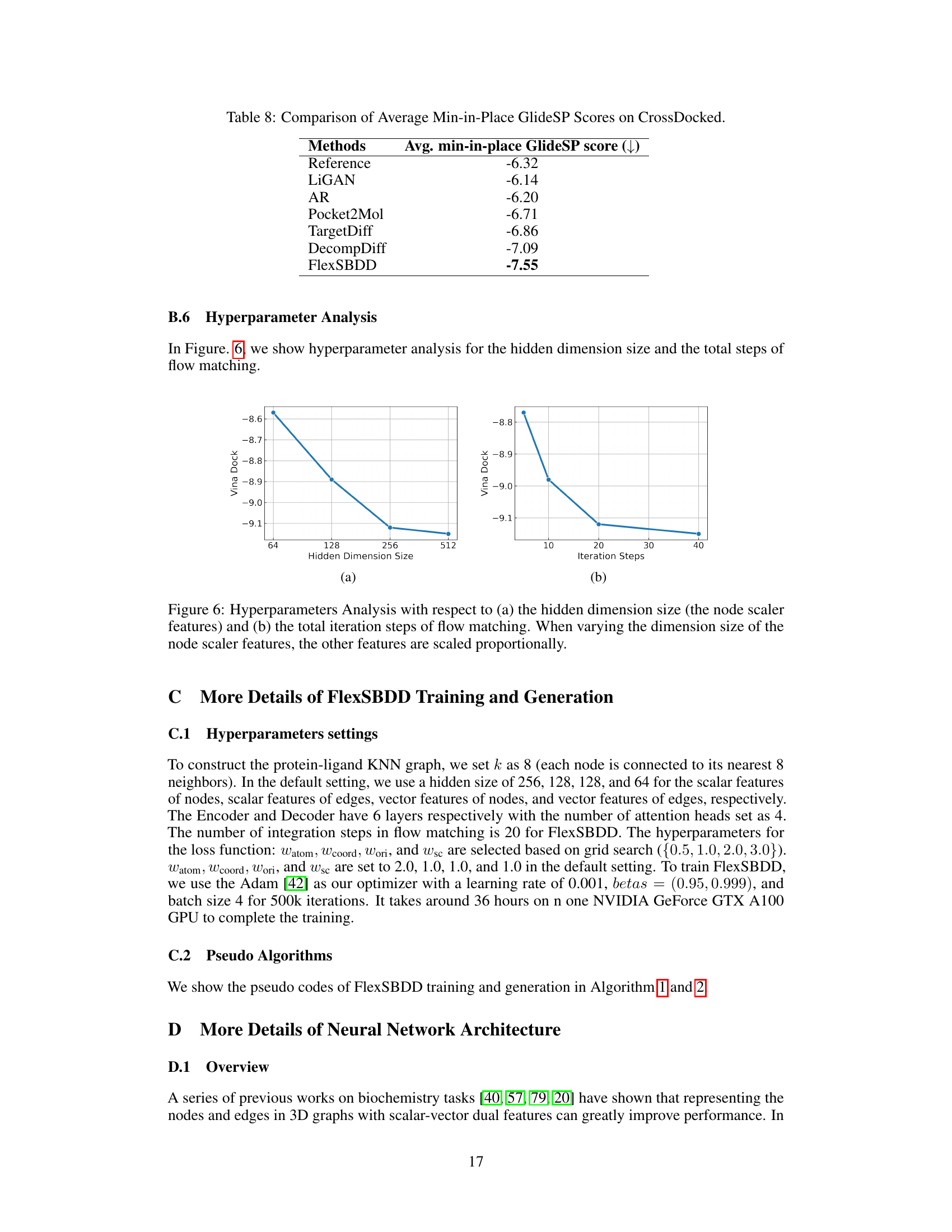

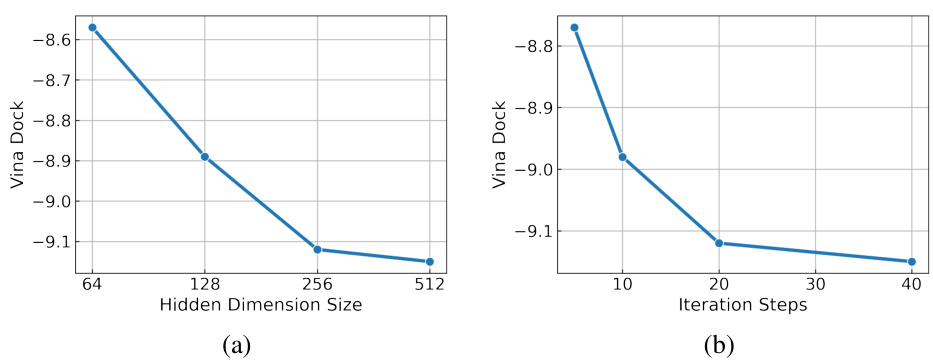

This figure shows the effect of two hyperparameters on the performance of FlexSBDD: (a) Hidden dimension size: The graph shows that increasing the hidden dimension size leads to better Vina Dock scores, although improvements diminish after 256. (b) Iteration steps: The graph shows that increasing the number of iterations in flow matching also leads to better Vina Dock scores, with diminishing returns after 20 steps. In both cases, optimal values are determined through experimentation to find a balance between model performance and computational cost.

More on tables

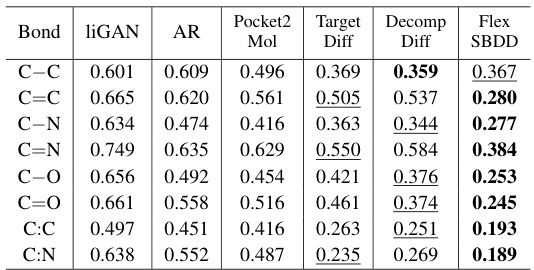

This table presents the Jensen-Shannon divergence values, which measure the similarity between the bond distance distributions of the reference and generated ligand molecules. Lower values indicate a higher similarity, suggesting that the generated molecules have more realistic bond distances compared to the reference molecules. The bond types considered are single, double, and aromatic bonds, represented as ‘-’, ‘=’, and ‘…’, respectively. The table helps evaluate the quality of the 3D molecules generated by FlexSBDD by comparing their structural properties to those of real molecules.

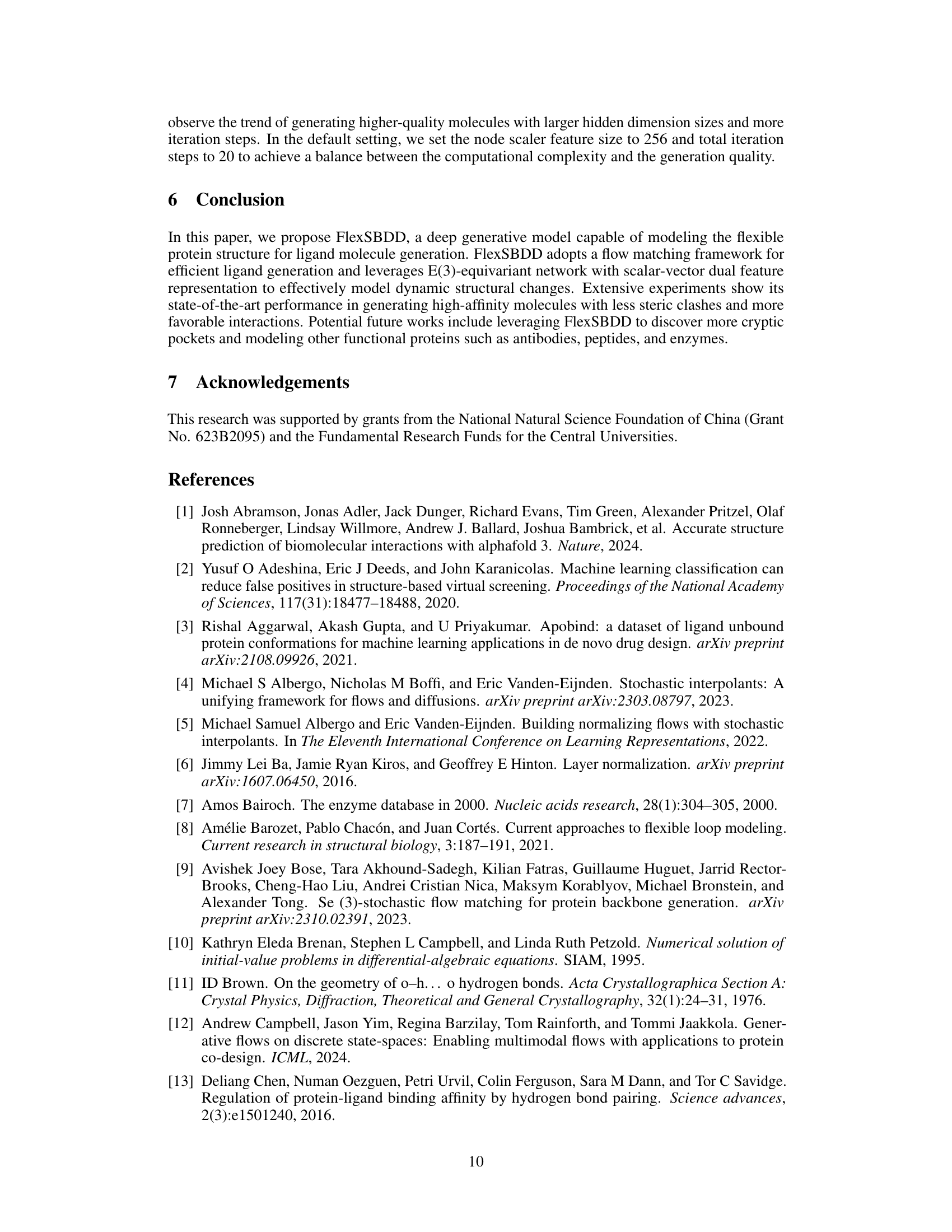

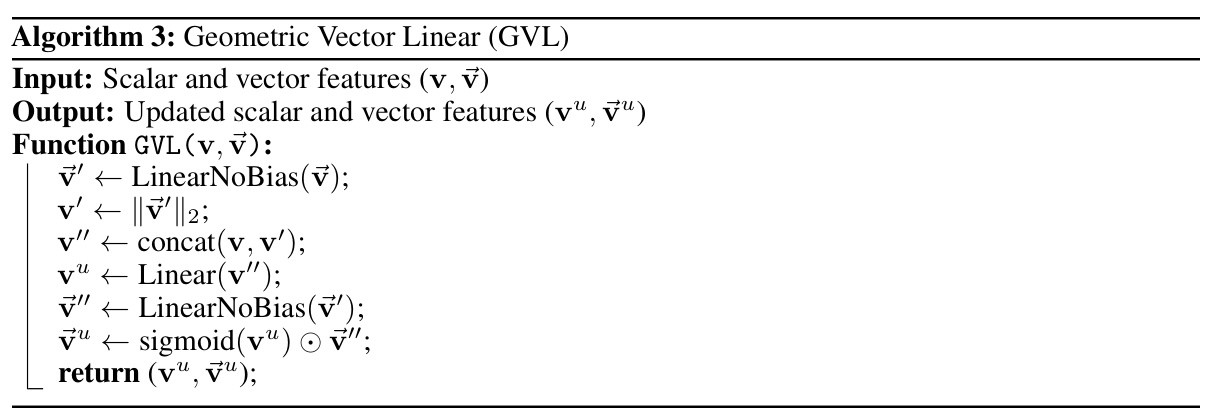

This table presents the ablation study results, comparing FlexSBDD’s performance against variants with different components removed or replaced. It shows the impact of data augmentation, the choice of geometric vector modules (compared to EGNN), and the impact of updating the protein backbone and side chains. The metrics used are Vina Score (lower is better), Vina Min (lower is better), Vina Dock (lower is better), and QED (higher is better). The table highlights how each component contributes to FlexSBDD’s overall performance.

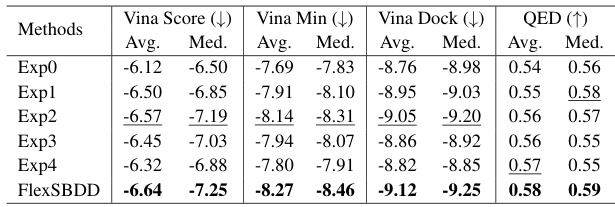

This table presents a comparison of the performance of different methods for structure-based drug design (SBDD) on the CrossDocked dataset. It shows key metrics related to the generated molecules, including binding affinity (Vina Score, Vina Min, Vina Dock), the percentage of molecules with higher binding affinity than the reference molecule (High Affinity), drug-likeness (QED, SA), and diversity. Lower Vina scores indicate higher binding affinity. Higher values for QED, SA, and diversity are generally preferred.

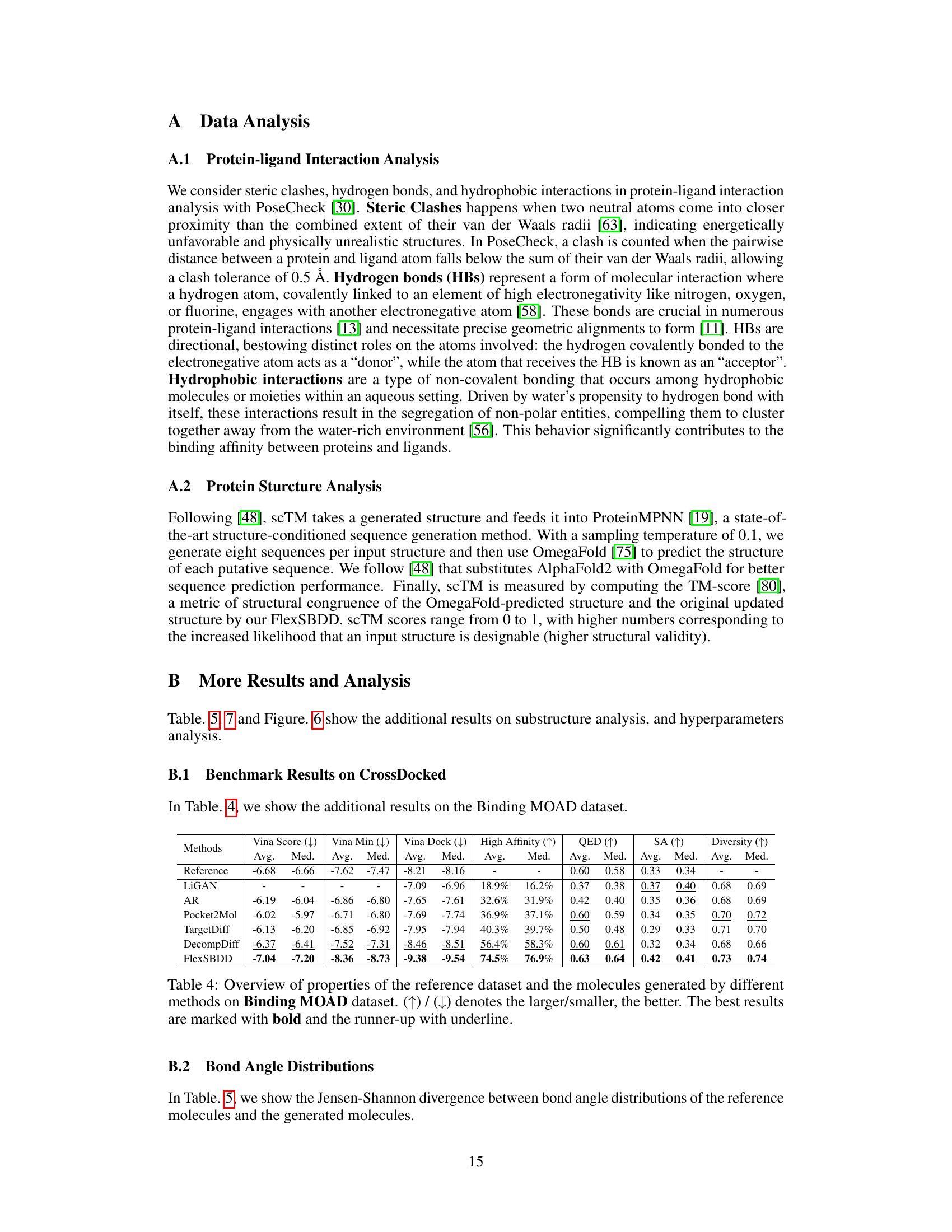

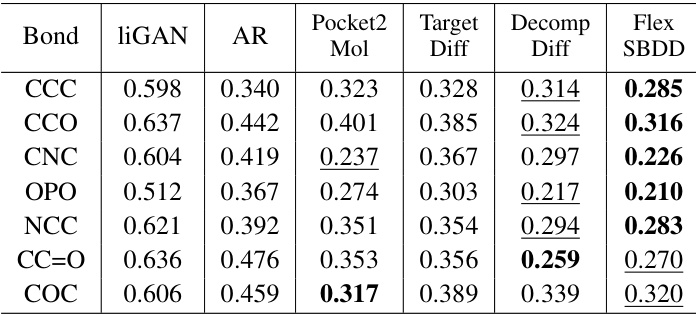

This table shows the Jensen-Shannon divergence (JSD) values for different bond angle types between the generated molecules and the reference molecules. Lower JSD values indicate a better match between the generated and reference molecules, suggesting the model is producing more realistic molecular structures. The best two results for each bond angle type are highlighted.

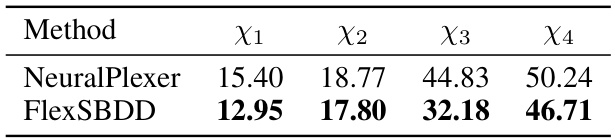

This table presents the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) in degrees for sidechain torsion angles (χ1, χ2, χ3, χ4). It compares the performance of FlexSBDD against NeuralPlexer, a state-of-the-art protein-ligand complex structure prediction method. Lower MAE values indicate better accuracy in predicting sidechain conformations. FlexSBDD shows improved accuracy over NeuralPlexer across all four torsion angles.

This table presents the ablation study results, comparing FlexSBDD’s performance against variants with modifications to data augmentation, geometric vector modules, protein structure updates, sidechain updates, and the overall model flexibility. It shows the impact of each component on key metrics like Vina Score, Vina Min, and QED, highlighting the contribution of each feature.

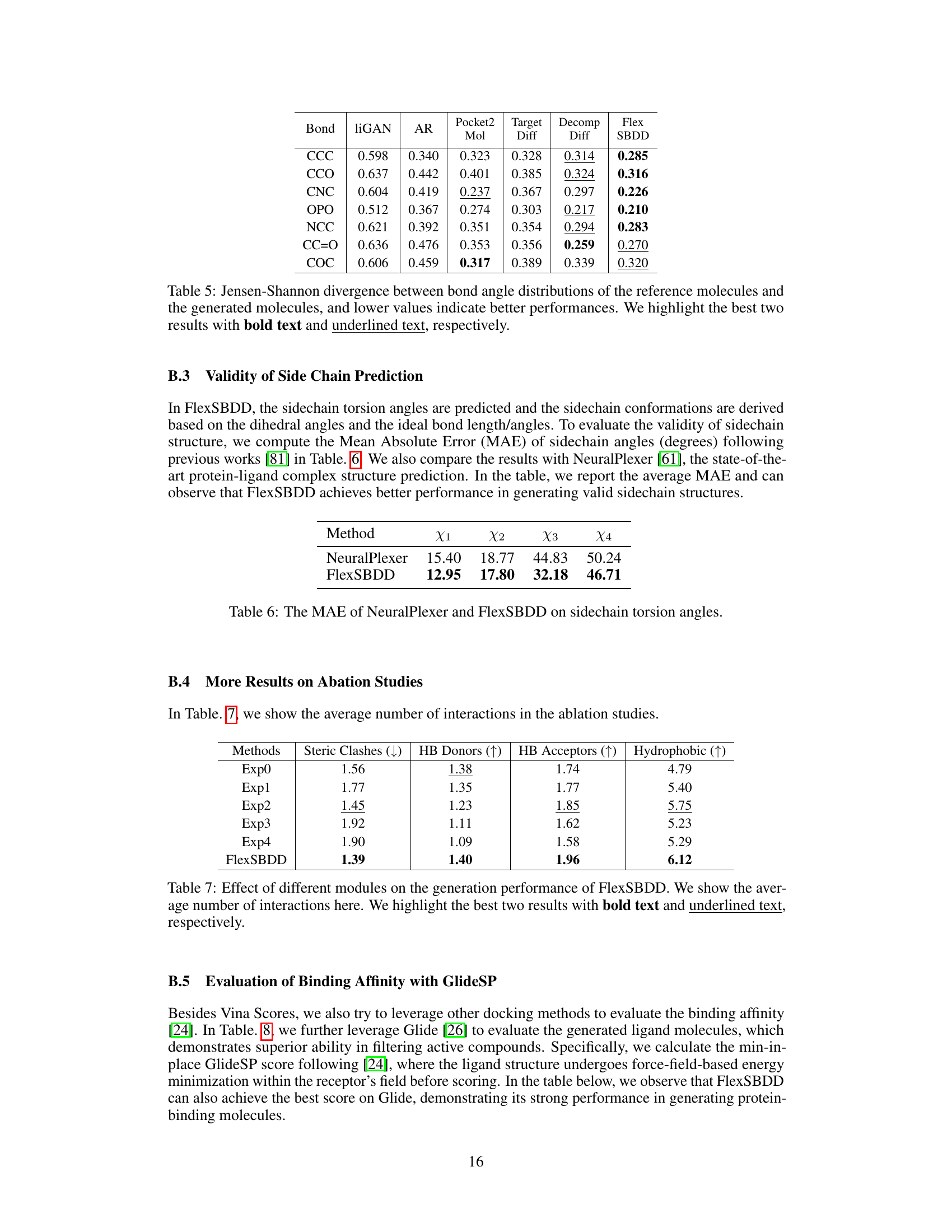

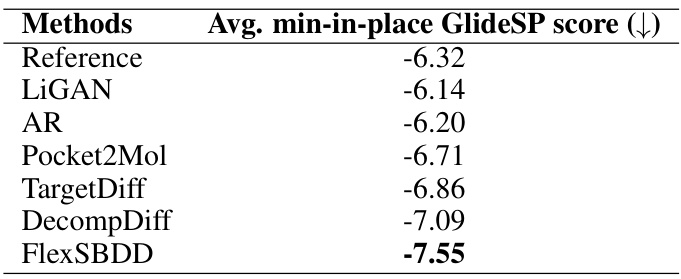

This table compares the average minimum-in-place GlideSP scores achieved by different methods on the CrossDocked dataset. GlideSP is a docking scoring function that involves force-field energy minimization within the receptor’s field, offering a more refined evaluation than other scoring functions. Lower GlideSP scores indicate higher binding affinity. The table shows that FlexSBDD outperforms other state-of-the-art methods.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of various methods for structure-based drug design (SBDD) on the CrossDocked dataset. It assesses the quality of generated molecules based on various metrics, including binding affinity (Vina Score, Vina Min, Vina Dock), the percentage of generated molecules with higher binding affinity than the reference molecule (High Affinity), drug-likeness properties (QED, SA), molecular diversity, and the number of steric clashes. Lower Vina scores indicate better binding affinity, while higher QED, SA, and Diversity scores are preferred.

Full paper#