↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional graph neural networks (GNNs) suffer from message-passing bottlenecks and high computational costs due to their reliance on fixed graph topology. These limitations hinder the performance and scalability of GNNs, especially when dealing with large-scale graphs. Existing solutions attempt to mitigate these issues but often introduce new challenges such as high complexity or information bottlenecks.

This paper introduces N2, a novel GNN model that uses a dynamic message-passing mechanism. N2 projects graph nodes and learnable pseudo-nodes into a common space, enabling flexible pathway construction based on evolving spatial relationships. This approach addresses the inherent limitations of traditional message passing, resulting in significant improvements in efficiency and performance. The model utilizes a single recurrent layer, further contributing to parameter efficiency and scalability. Extensive evaluations on various benchmarks demonstrate the superiority of N2, showcasing its ability to successfully tackle complex graph-structured data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on graph neural networks (GNNs). It directly addresses the limitations of traditional message-passing mechanisms by introducing a novel dynamic approach. This offers significant improvements in efficiency and performance, particularly for large-scale graphs. The proposed dynamic message passing mechanism also tackles over-squashing and over-smoothing issues, thus significantly enhancing the scalability and generalizability of GNNs. The proposed N2 model and its superior performance across eighteen benchmarks open new avenues for GNN research and applications.

Visual Insights#

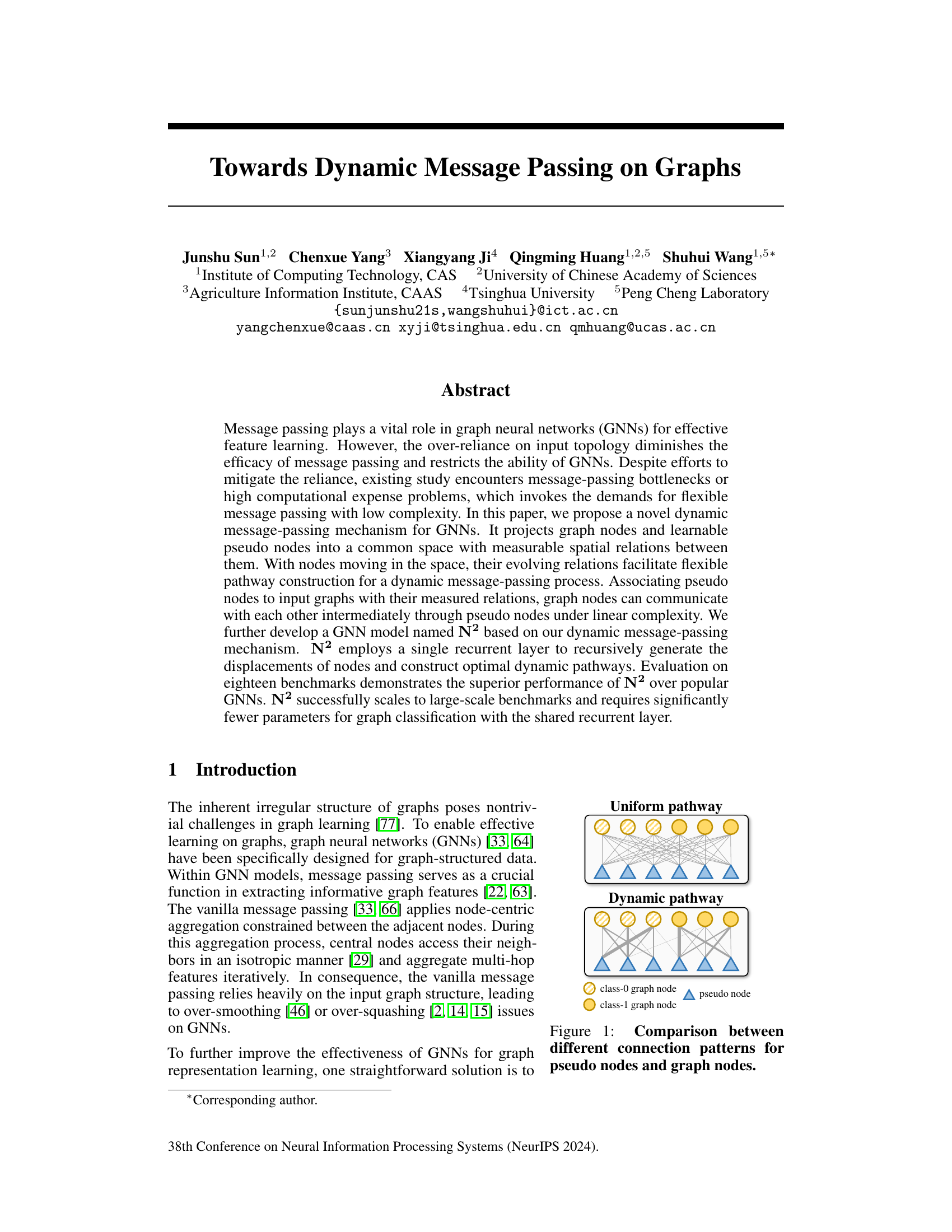

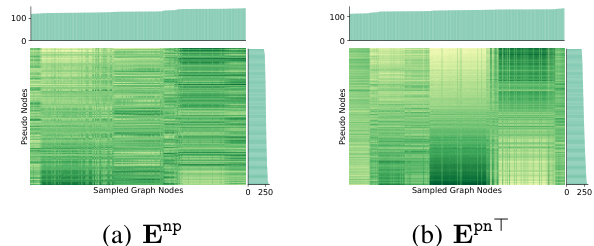

This figure compares two different ways of connecting pseudo nodes and graph nodes. In the ‘Uniform pathway’, each pseudo node is uniformly connected to all graph nodes, whereas in the ‘Dynamic pathway’, connections are dynamic and vary according to the learned relations. This dynamic approach allows for flexible message passing pathways, which is central to the proposed N2 model.

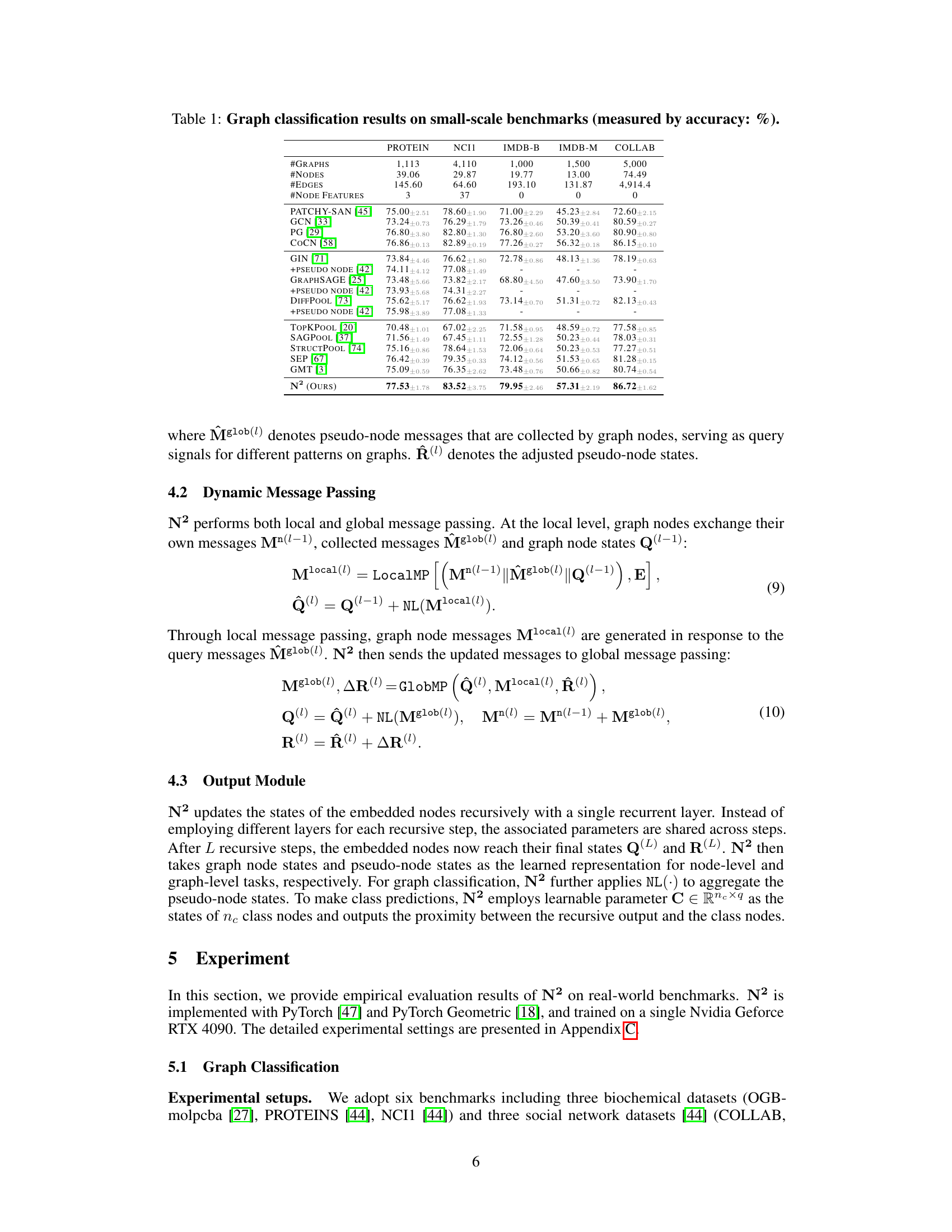

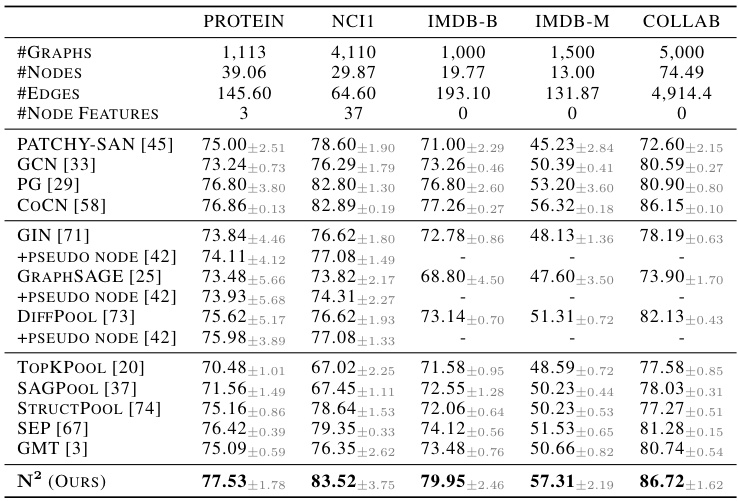

This table presents the results of graph classification experiments on six small-scale benchmark datasets. The table shows the accuracy (%) achieved by various graph neural network (GNN) models, including several baselines and the proposed N². Each row represents a different GNN model, and each column represents a different benchmark dataset. The results demonstrate the performance of N² in comparison to existing models on these relatively smaller-scale graph classification problems.

In-depth insights#

Dynamic GNNs#

Dynamic GNNs represent a significant advancement in graph neural networks, addressing the limitations of static graph structures. They enable modeling of evolving relationships and temporal dependencies within graphs, offering enhanced capabilities for various applications. This dynamism is achieved through mechanisms such as incorporating time-series data directly into the GNN architecture, using recurrent neural networks to process sequential graph data, or by dynamically adjusting the graph structure itself during the learning process. The key advantage lies in their ability to capture the continuous evolution of complex systems, providing improved accuracy and interpretability in scenarios where static models fall short, like social networks, recommendation systems, and traffic flow prediction. However, challenges remain in managing the increased computational complexity and ensuring the model’s stability while handling constantly changing graphs. Future research could explore more efficient algorithms and novel architectures to address these challenges, further expanding the capabilities and applications of Dynamic GNNs.

Pseudo-Node Pathways#

The concept of “Pseudo-Node Pathways” in graph neural networks offers a compelling approach to enhance message passing efficiency and flexibility. By introducing learnable pseudo-nodes into the graph, new communication channels are created that bypass the constraints of the original graph structure. This dynamic approach allows for more flexible information flow and potentially mitigates issues like over-smoothing and over-squashing. The key lies in how the pseudo-nodes interact with the actual graph nodes, possibly through learned spatial relationships or attention mechanisms. Effective design would involve careful consideration of the number of pseudo-nodes to avoid introducing new bottlenecks. The learnability of the pseudo-nodes and their connections offers significant advantages, allowing the model to adapt to specific graph structures and learn optimal information pathways. A well-defined method for measuring and managing the interactions between pseudo-nodes and real nodes would be crucial for its success. Ultimately, the effectiveness hinges on whether these pseudo-node pathways enable the model to learn more informative representations with lower computational cost compared to traditional methods.

Recurrent Layer Design#

Recurrent layers in graph neural networks (GNNs) offer a powerful mechanism for capturing temporal dynamics and higher-order relationships within graph data. A well-designed recurrent layer can significantly improve the model’s ability to learn complex patterns and make more accurate predictions. The choice of recurrent unit (e.g., LSTM, GRU) is crucial, as different units possess varying capabilities in handling long-range dependencies and non-linear transformations. Furthermore, the architecture of the recurrent layer—such as its depth and the way it interacts with the graph’s message-passing mechanisms—greatly impacts the model’s performance and efficiency. Careful consideration of parameter sharing and regularization techniques within the recurrent layer is essential to prevent overfitting and ensure generalizability. Effective initialization strategies can accelerate convergence and improve the overall model training. Finally, a crucial aspect of recurrent layer design lies in its interaction with the rest of the GNN architecture, such as how it integrates with the message-passing layers and the pooling mechanisms. This interplay significantly influences the model’s capacity to capture both local and global information on the graph effectively.

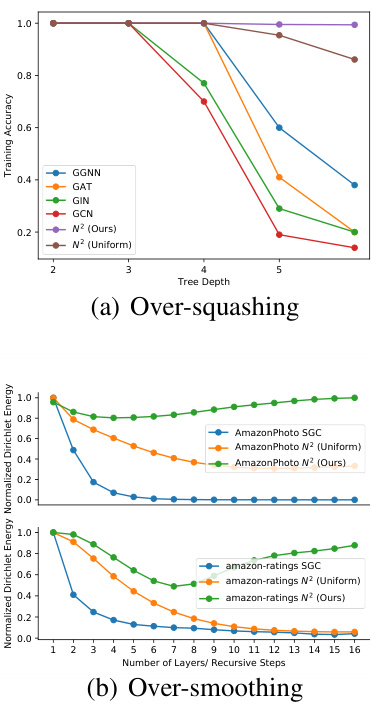

Over-Squashing Relief#

Over-squashing, a phenomenon in graph neural networks (GNNs), arises from the iterative aggregation of node features, leading to information loss and reduced expressiveness. Relief strategies often focus on modifying the message-passing mechanism to mitigate this issue. One approach involves incorporating skip connections or attention mechanisms to allow for the direct flow of information between nodes, bypassing the iterative aggregation steps. Another approach could involve dynamic routing of information, where the pathways for information flow adapt to the specific input graph structure. This adaptive approach could use learned embeddings or attention weights to guide information flow, ensuring that crucial features are not lost during aggregation. Pseudo-nodes could provide a mechanism for intermediate message passing, reducing the reliance on direct node-to-node connections and alleviating over-squashing. By strategically introducing pseudo-nodes, the network could establish multiple paths for feature propagation. Furthermore, a recurrent layer can learn dynamic adjustments to node embeddings, offering a method for recursively refining the feature representations and counteracting the effects of information squashing. Careful design of these approaches is critical; poorly designed methods could exacerbate the issue or introduce other problems like over-smoothing or increased computational cost. Ultimately, effective over-squashing relief relies on finding a balance between preserving essential information, reducing computational overhead, and ensuring that the network remains capable of generalizing to unseen graphs.

Scalability & Limits#

A crucial aspect of any machine learning model is its scalability. The paper’s ‘Scalability & Limits’ section would likely address how well the proposed dynamic message-passing mechanism handles increasingly large graphs. This involves examining computational complexity, analyzing memory usage, and assessing the model’s performance as the number of nodes and edges grows. Key limitations might include the model’s ability to process graphs exceeding a certain size, or constraints arising from the computational cost of dynamic pathway construction. The discussion should also cover the model’s sensitivity to variations in graph structure, density, and the presence of noise or outliers. Practical aspects such as implementation challenges on distributed systems, data partitioning strategies, and the trade-offs between accuracy and speed would also need to be examined. Ultimately, a thorough analysis in this section would clarify the model’s practical applicability across different scales and types of graphs, while highlighting potential areas for future improvement.

More visual insights#

More on figures

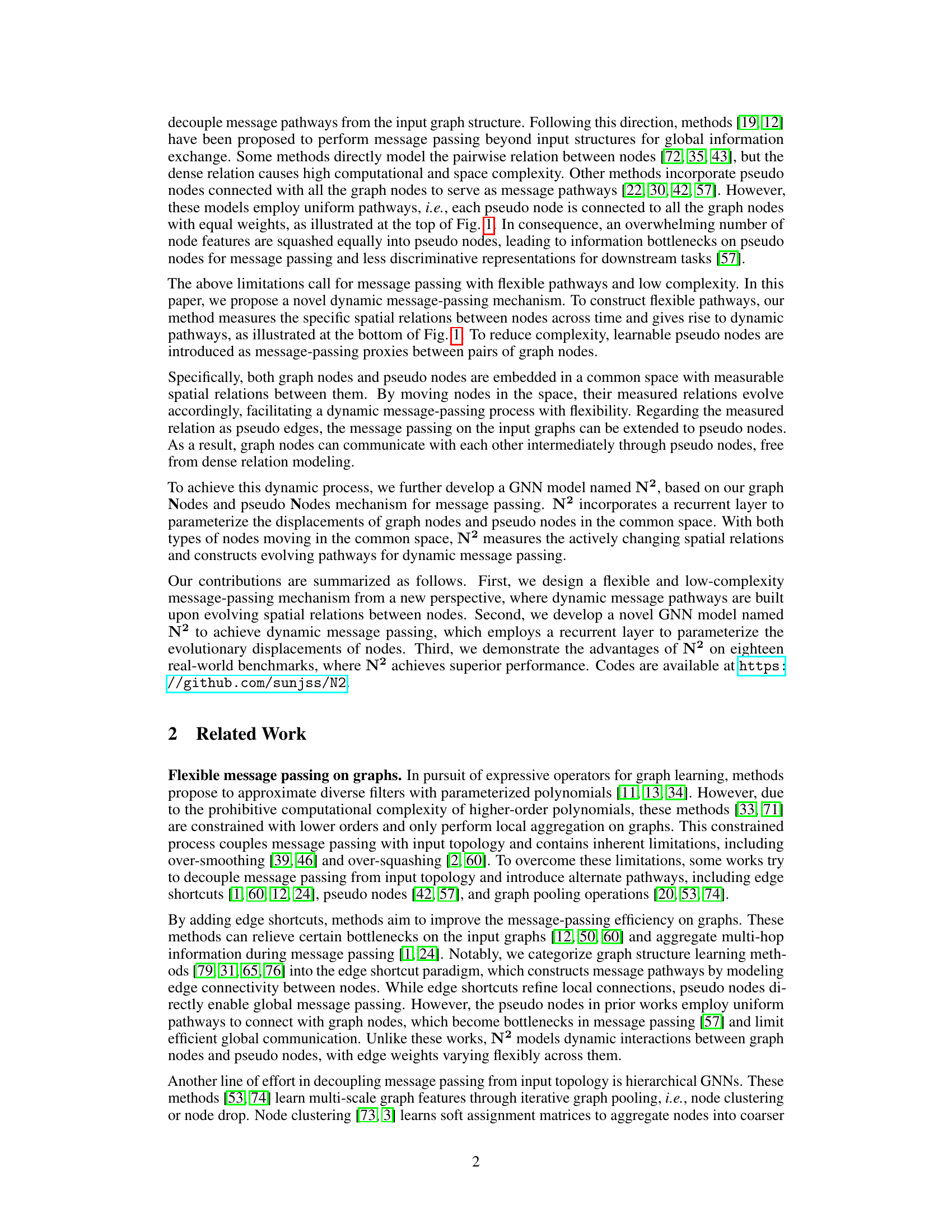

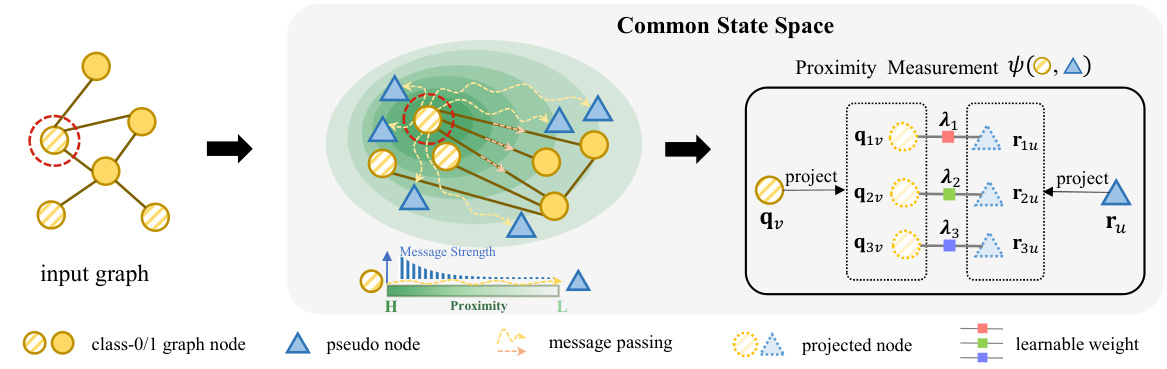

This figure illustrates the dynamic message-passing mechanism of the proposed N2 model. It shows how graph nodes and pseudo-nodes are projected into a common state space where their proximity is measured and used to form dynamic pathways for message passing. The pseudo-nodes act as intermediaries, enabling flexible communication between graph nodes, especially those that are not directly connected. The illustration highlights how the proximity measurement facilitates flexible pathways, unlike traditional fixed pathways in uniform message passing methods. The empirical observation that pseudo-nodes tend to cluster around specific graph node clusters is also noted.

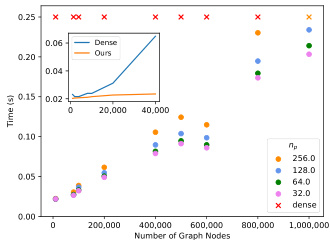

This figure shows the results of a complexity analysis performed on the proposed dynamic message-passing method (N²) and compares it to a dense pairwise relation modeling method. The x-axis represents the number of graph nodes, and the y-axis represents the time taken for computation. The results demonstrate that the proposed dynamic message-passing mechanism scales linearly with the number of graph nodes, whereas the dense method encounters out-of-memory errors for larger datasets. The inset graph provides a zoomed-in view of the lower range of graph nodes to illustrate the difference more clearly.

This figure illustrates the dynamic message-passing mechanism in the common state space. Graph nodes and pseudo-nodes are projected into this space, and their spatial proximity is measured. This proximity determines the message pathways, which dynamically change as nodes move. The illustration highlights how pseudo-nodes act as intermediaries, facilitating flexible communication between graph nodes, and how they tend to cluster near specific groups of graph nodes.

This figure illustrates the dynamic message-passing mechanism of the proposed N2 model. It shows how graph nodes and pseudo-nodes are projected into a common state space where they interact dynamically. The proximity (spatial relationship) between nodes is measured and used to construct dynamic message pathways. The illustration highlights that pseudo-nodes tend to cluster around specific graph node clusters.

This figure illustrates the dynamic message-passing pathway construction in the common state space. Graph nodes and pseudo-nodes are projected into a common space, and their spatial relationships are measured using a proximity function. The proximity measurement allows for flexible pathway construction during message passing, enabling nodes to communicate indirectly through pseudo-nodes even if they aren’t directly connected in the input graph. The dynamic pathways are constructed by learning the displacements of nodes in this space. Empirical studies have shown that pseudo-nodes tend to be attracted to specific clusters of graph nodes in the common space, highlighting their role in facilitating flexible message passing.

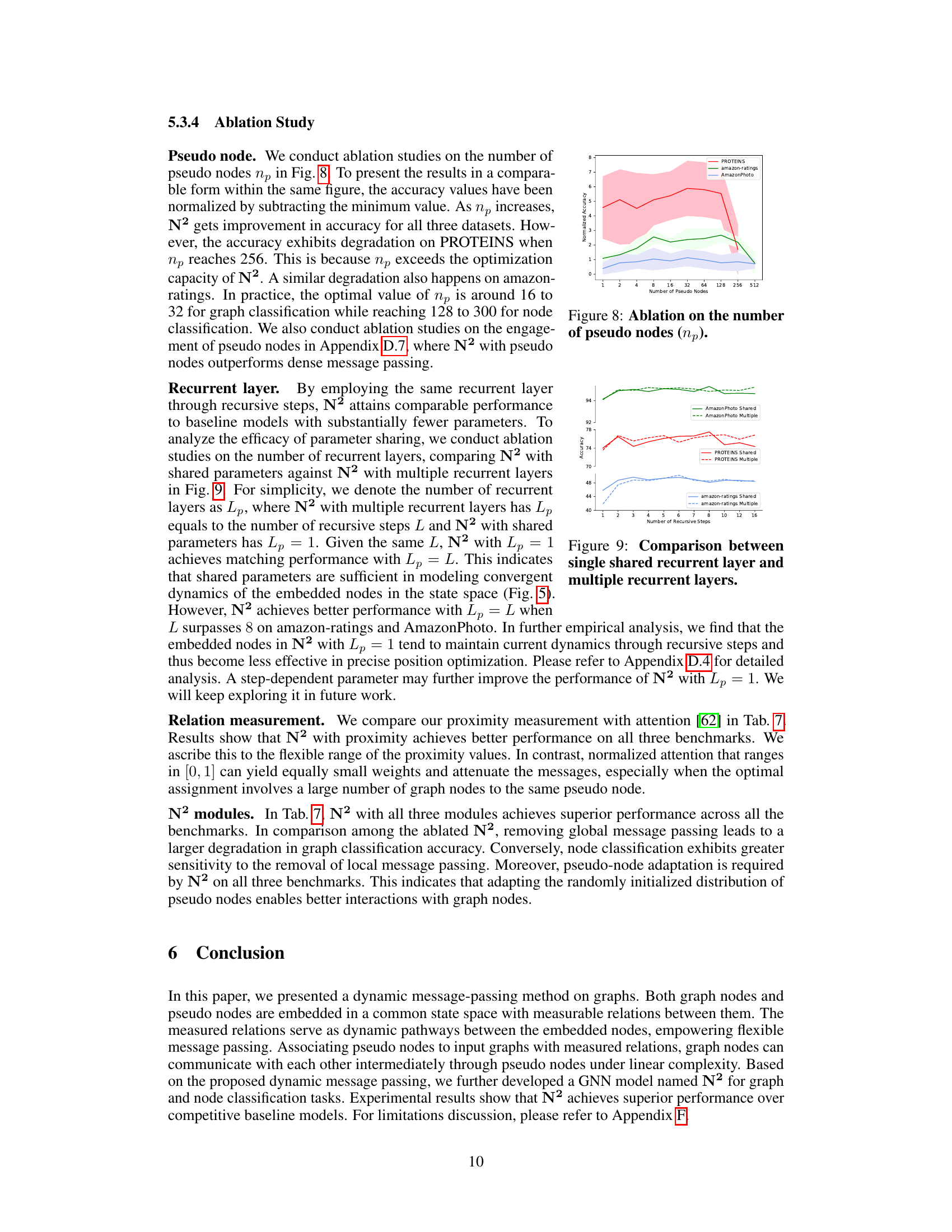

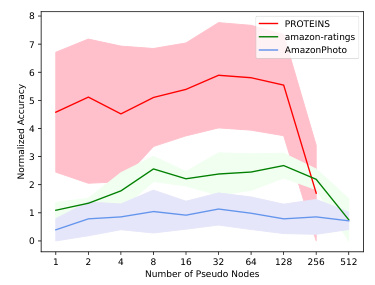

This ablation study analyzes the impact of varying the number of pseudo nodes (np) on the model’s performance across three different datasets: PROTEINS, amazon-ratings, and AmazonPhoto. The results show a general trend of improved accuracy as np increases, but also reveal dataset-specific behavior and an optimal value beyond which performance starts to decrease. The shaded regions represent the standard deviation of the normalized accuracy.

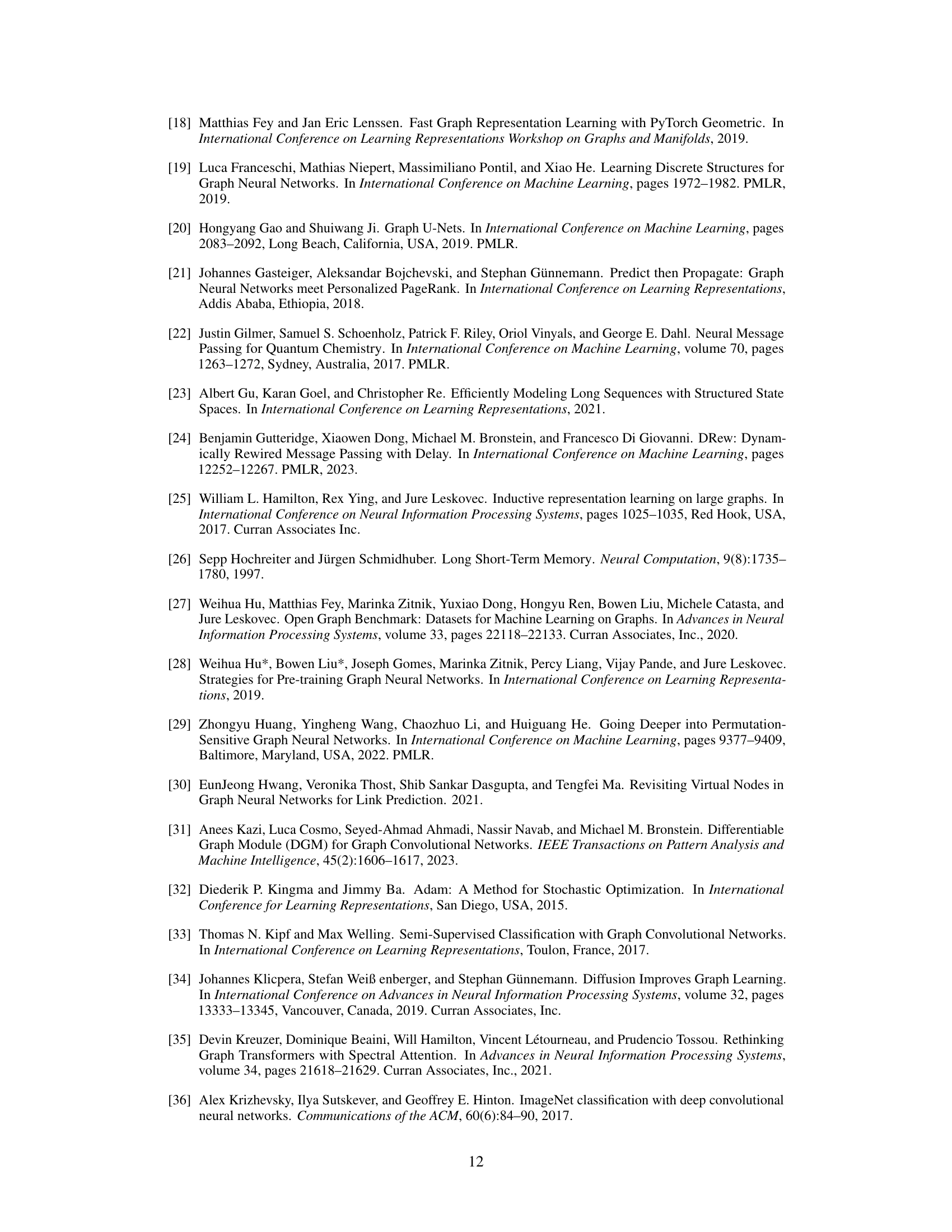

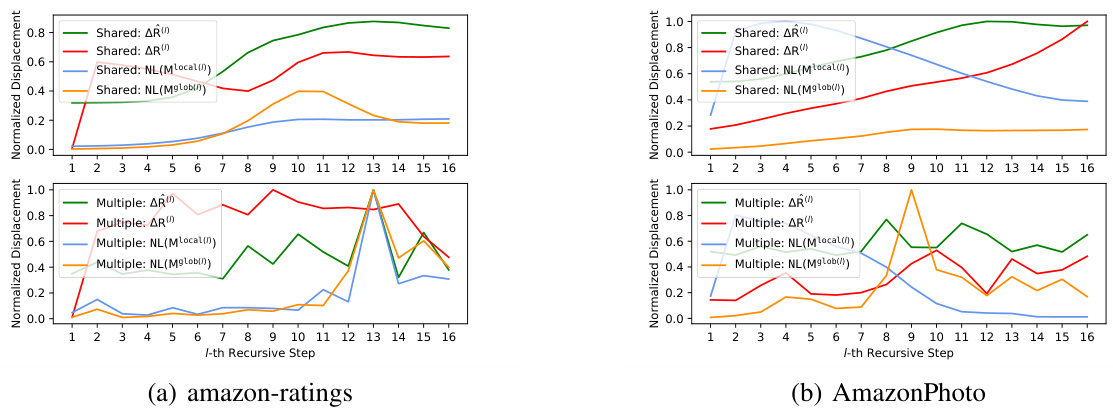

This figure compares the performance of N² with a single shared recurrent layer against N² with multiple recurrent layers. The x-axis represents the number of recursive steps, and the y-axis represents the accuracy achieved on three different datasets (AmazonPhoto, PROTEINS, and amazon-ratings). The solid lines represent results for the model with a single shared recurrent layer, while the dashed lines show results for the model with multiple layers. The results show that a single shared recurrent layer can achieve comparable performance to multiple layers, highlighting the efficiency of parameter sharing in N².

This figure visualizes the distribution of embedded nodes (graph nodes and pseudo-nodes) in the common state space during training. It uses t-SNE to reduce the dimensionality and shows how the nodes cluster based on their labels. The visualization demonstrates that as training progresses (Epoch 20, Epoch 500), pseudo-nodes tend to cluster near specific graph node clusters, effectively creating dynamic pathways for message passing between the node clusters.

The figure illustrates the dynamic message-passing mechanism of the proposed N2 model. Graph nodes and pseudo nodes are projected into a shared common space where their spatial proximity is measured. As nodes move in this space, their relationships change dynamically, creating flexible pathways for message passing. Pseudo nodes act as intermediaries, facilitating communication between graph nodes. Empirical analysis shows pseudo nodes tend to cluster near specific graph node clusters.

This figure illustrates the dynamic message-passing mechanism proposed in the paper. It shows how graph nodes and pseudo-nodes are projected into a common state space, where their spatial relationships determine the message pathways. The proximity measurement function, ψ(·, ·), quantifies the relationships between nodes, enabling the construction of dynamic pathways. The illustration also suggests that pseudo-nodes tend to group near clusters of similar graph nodes, indicating their ability to facilitate efficient and flexible message passing.

This ablation study shows the impact of varying the number of pseudo nodes (np) on the accuracy of graph classification across three datasets: AmazonPhoto, PROTEINS, and amazon-ratings. The accuracy is normalized by subtracting the minimum value for easier comparison. Generally, increasing the number of pseudo nodes improves accuracy up to a point, after which performance starts to degrade because the model’s capacity is exceeded.

More on tables

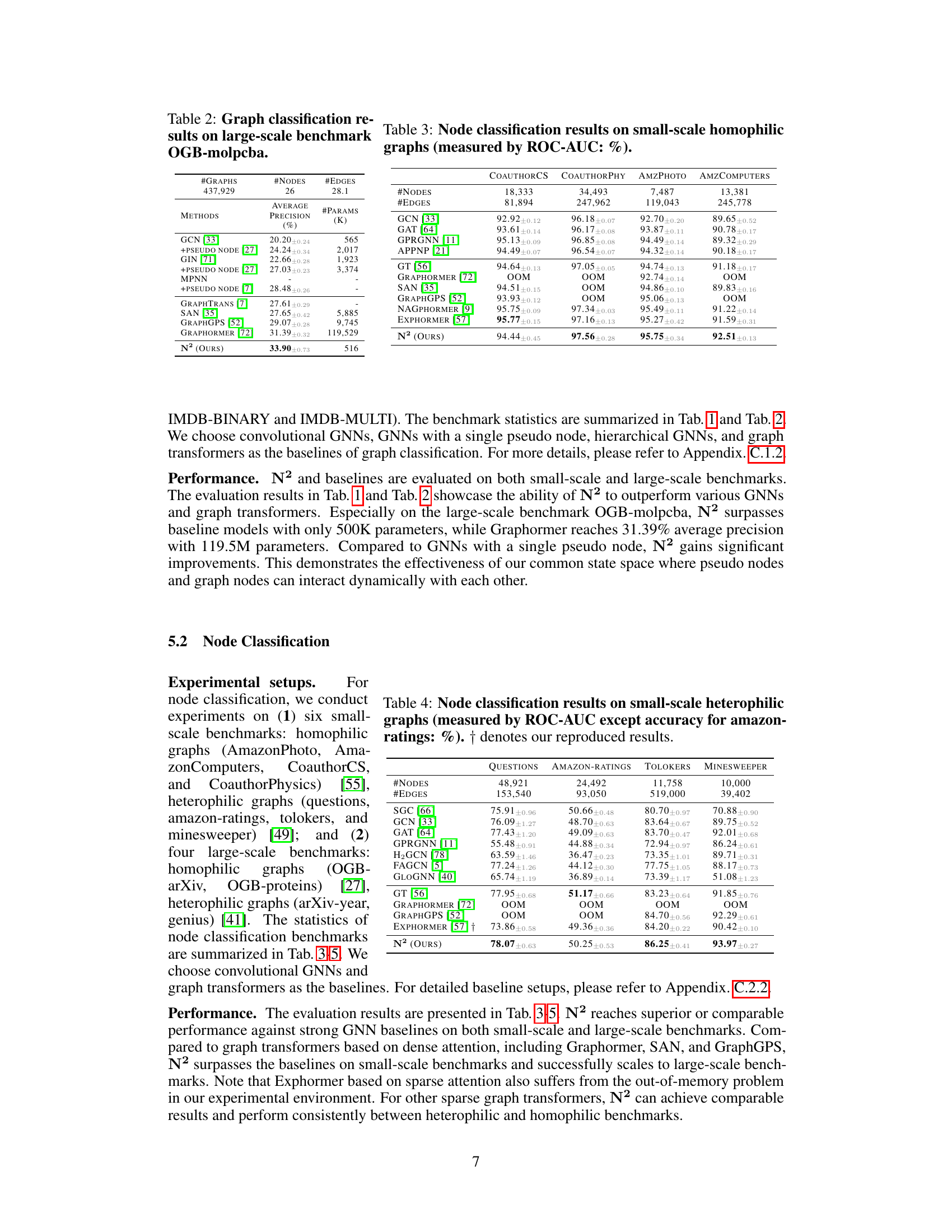

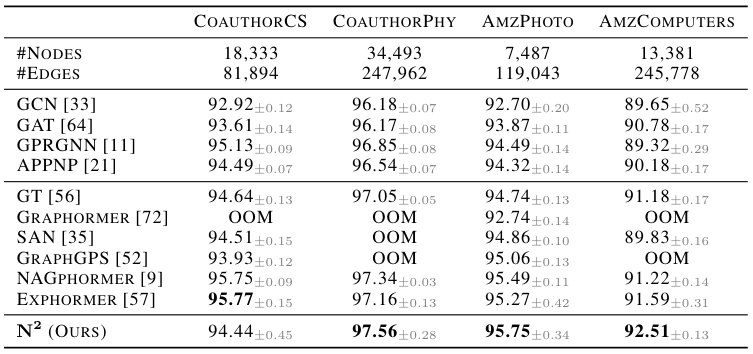

This table presents the results of node classification experiments conducted on six small-scale homophilic graph datasets. The results are measured using the ROC-AUC metric and compare the performance of various methods, including GCN, GAT, GPRGNN, APPNP, GIN, H2GCN, FAGCN, GloGNN, GT, Graphormer, GraphGPS, and Exphormer, with the proposed N² method. The table shows average precision (%) and the number of parameters (in thousands) for each method. The datasets used span a variety of domains and sizes.

This table presents the results of node classification experiments conducted on six small-scale homophilic graph datasets. The results are measured using the ROC-AUC (Receiver Operating Characteristic - Area Under the Curve) metric, a common evaluation measure for node classification problems. The table compares the performance of the proposed N² model against several other state-of-the-art graph neural network (GNN) models. The datasets used are AmazonPhoto, AmazonComputers, CoauthorCS, CoauthorPhysics, Questions, and Amazon-ratings. The table provides a detailed comparison of the ROC-AUC scores achieved by each model on each dataset. This allows for a quantitative assessment of the relative performance of the different GNN models in a homophilic graph setting.

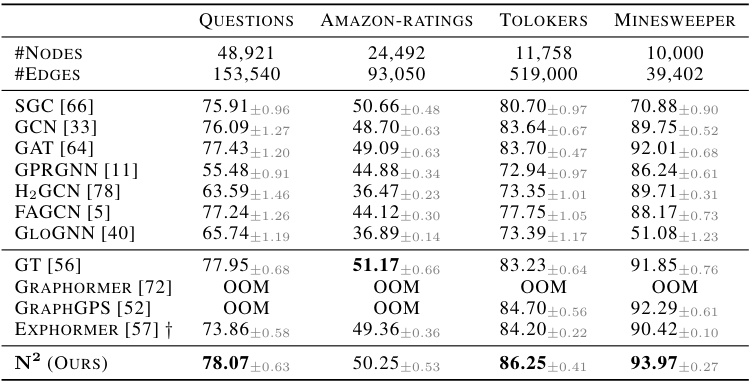

This table presents the results of node classification experiments conducted on six small-scale heterophilic graph datasets. The table compares the performance (measured by ROC-AUC, except for Amazon-ratings where accuracy is used) of the proposed N² model against several baseline methods, including SGC, GCN, GAT, GPRGNN, H2GCN, FAGCN, GLOGNN, GT, Graphormer, GraphGPS, and Exphormer. The results highlight the performance of N² in comparison to these baseline models on heterophilic graph datasets.

This table presents the results of node classification experiments conducted on four large-scale benchmark datasets: GENIUS, ARXIV-YEAR, OGB-ARXIV, and OGB-PROTEINS. The metrics used for evaluation are ROC-AUC (for GENIUS, ARXIV-YEAR, and OGB-PROTEINS) and accuracy (for ARXIV-YEAR). The table compares the performance of the proposed N² model against several state-of-the-art baseline methods. Note that some baseline models resulted in out-of-memory (OOM) errors, highlighting the scalability challenges associated with large graph datasets. The results demonstrate N²’s ability to achieve superior or comparable performance on these challenging benchmarks.

This table presents the ablation study results on the different modules of the N2 model. The accuracy is measured on three datasets: Amz-ratings, Amz-Photo, and RPO-TEINS. The modules being ablated include pseudo-node adaptation (PA.), local message passing (L.), and global message passing (G.). Two variations are tested for the ‘Full’ model, one using attention (Att.) and the other using proximity (Prx.) measurements.

This table shows the hyperparameter settings used for the N2 model across various graph classification and node classification benchmarks. The hyperparameters include the number of recursive steps (L), hidden dimension, state space dimension, number of units (k), number of pseudo-nodes (np), and dropout rate. Different benchmarks have different optimal hyperparameter values, reflecting the varying characteristics of the datasets.

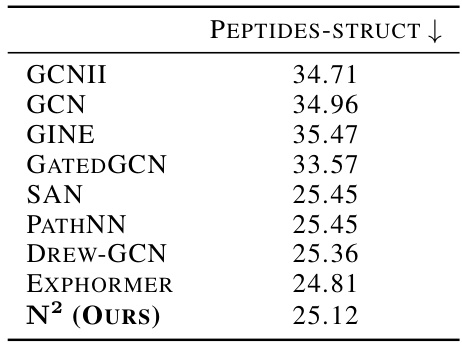

This table presents the results of an effectiveness study conducted on the peptides-struct benchmark dataset. The study compares the performance of various graph neural network (GNN) models, including GCNII, GCN, GINE, GATEDGCN, SAN, PATHNN, DREW-GCN, EXPHORMER, and the proposed model N², in terms of their mean absolute error. The goal is to evaluate the effectiveness of these models in handling the challenges of graph regression tasks, such as over-squashing. The table showcases the mean absolute error achieved by each model on the peptides-struct dataset.

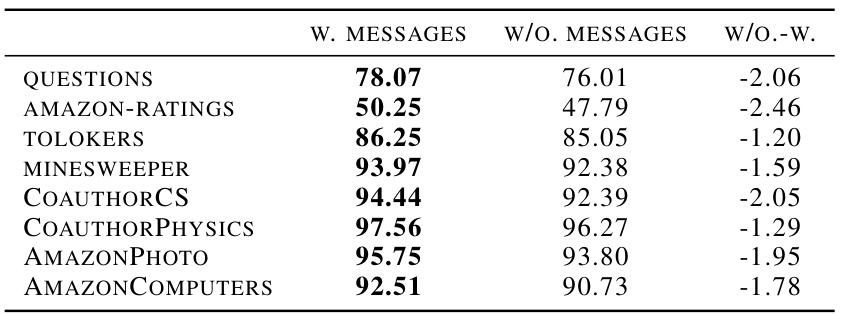

This table presents the ablation study results on the impact of using messages in the dynamic message-passing mechanism of the proposed N2 model. It compares the performance (measured by accuracy) on eight benchmark datasets: Questions, Amazon-Ratings, Tolokers, Minesweeper, CoauthorCS, CoauthorPhysics, AmazonPhoto, and AmazonComputers when using messages (W. MESSAGES) versus when not using messages (W/O. MESSAGES). The last column (W/O.-W.) shows the difference in accuracy between these two scenarios. The results indicate the relative importance of message passing for model performance on different datasets.

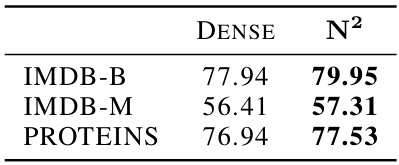

This table presents the graph classification accuracy results (%) for various graph neural network (GNN) models on several small-scale benchmark datasets. The table shows the performance of different GNN models including GCN, GraphSAGE, GIN, and the proposed model N². The benchmarks used cover different domains such as proteins, chemical compounds, and movie collaborations. Each dataset is characterized by its size in terms of the number of graphs, nodes, edges, and node features. This allows for a comparative assessment of the different GNN architectures and their efficacy on different graph characteristics.

Full paper#