↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large-scale calcium imaging generates massive datasets, and while automated algorithms exist for extracting neuron activity, human curation (cell sorting) remains necessary to remove errors. This process is time-consuming and prone to bias. Existing automated methods still require substantial human labor, and manual annotation is impractical due to the massive data size.

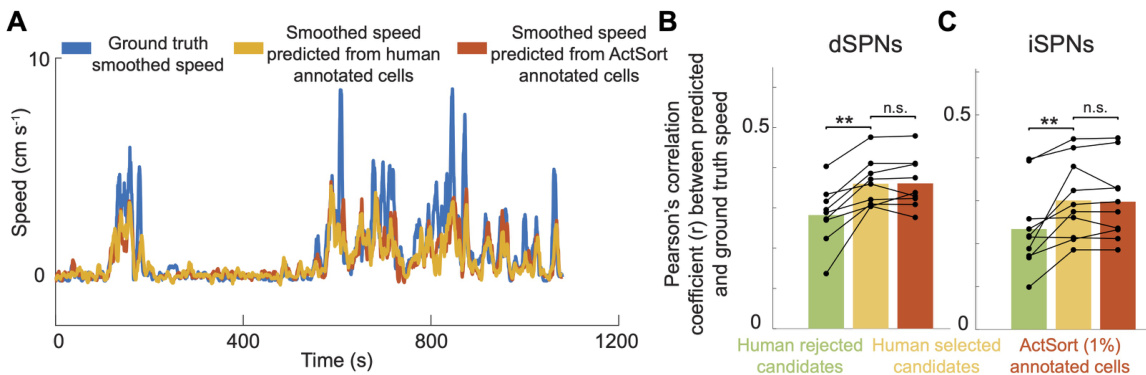

ActSort, an active learning algorithm, addresses this challenge by strategically selecting outlier cell candidates for annotation. It integrates domain-expert features and data formats with minimal memory needs, resulting in a drastic reduction of human effort (to 1-3% of candidates) and enhanced accuracy by mitigating annotator bias. This is supported by a first-of-its-kind benchmark study involving ~160,000 annotations. The user-friendly software makes ActSort accessible to experimental neuroscientists, promising to accelerate systems neuroscience research by enabling analysis of large-scale neural activity datasets.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in systems neuroscience due to its efficient solution to the cell sorting bottleneck in large-scale calcium imaging datasets. It offers a user-friendly software and streamlines data processing, enabling experiments at previously inaccessible scales. The innovative active learning approach and extensive benchmark will likely influence future research, potentially transforming how large-scale neural data is handled.

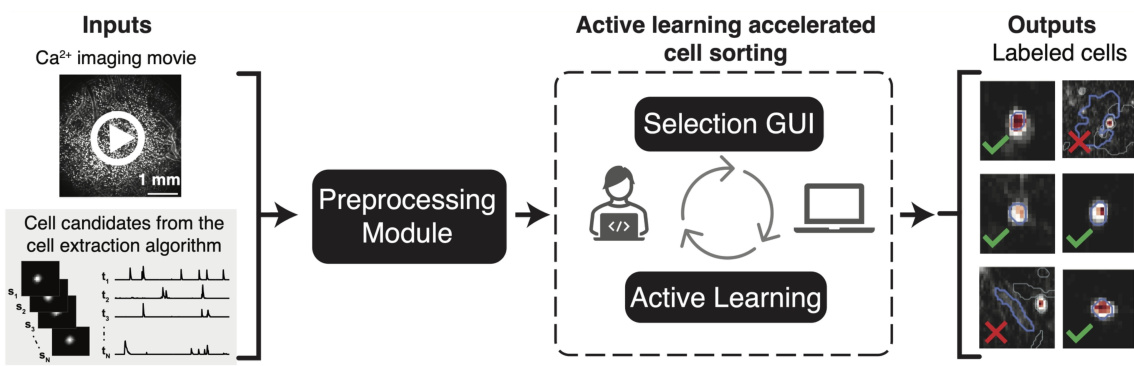

Visual Insights#

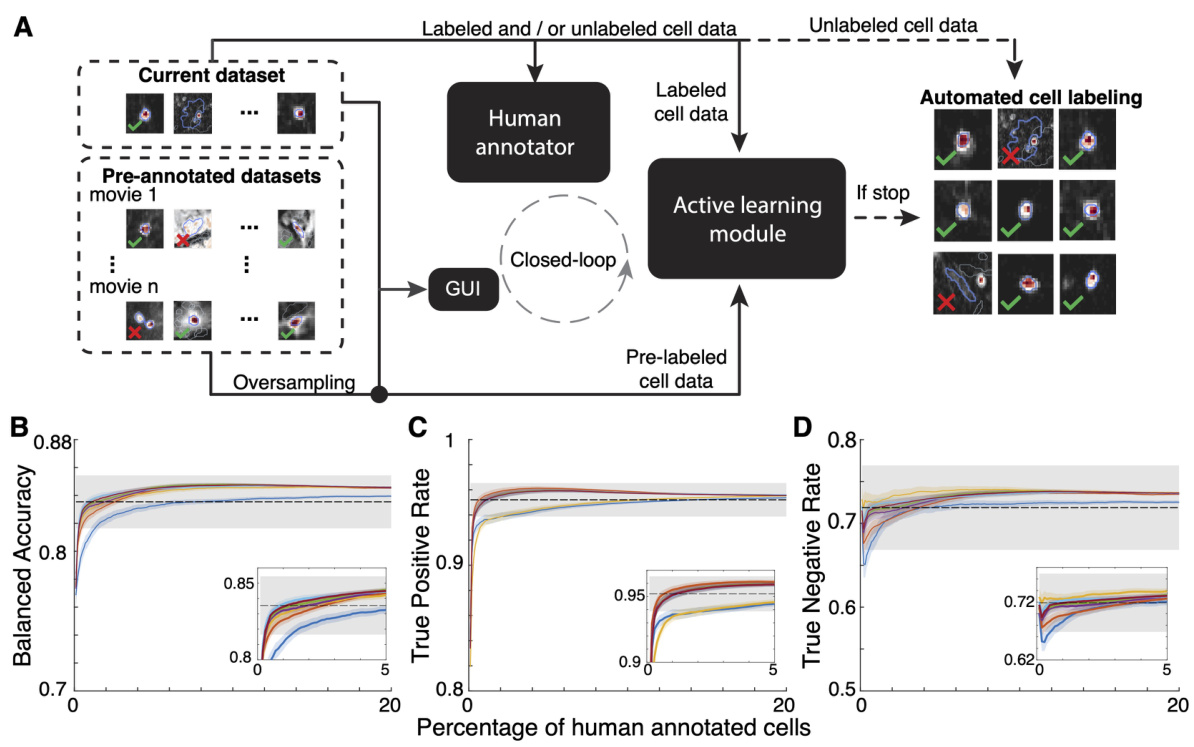

This figure illustrates the ActSort framework, which consists of three modules: preprocessing, selection GUI, and active learning. The preprocessing module compresses large datasets for efficient processing. The selection GUI allows human annotators to review and label cell candidates. The active learning module uses this feedback to intelligently select the most informative cells for annotation, thereby minimizing human effort and improving accuracy.

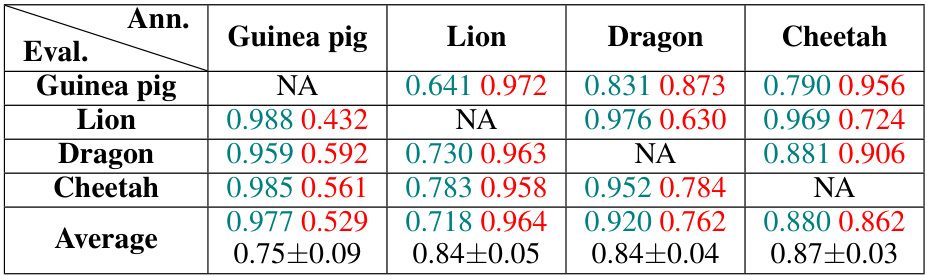

This table presents the results of a human annotation benchmark for a one-photon hemisphere dataset. Four annotators labeled 28,010 cell candidates, resulting in 112,040 annotations. The table shows the agreement between annotators, represented by accuracy scores for accepting and rejecting cell candidates. The average balanced accuracy across all annotators was approximately 80%. More details and visualizations are available in Figure S13.

In-depth insights#

Active Learning’s Role#

Active learning plays a crucial role in ActSort by dramatically reducing the human annotation effort required for large-scale calcium imaging data. Instead of requiring human annotators to label all cell candidates, ActSort strategically selects the most informative samples for annotation. This is achieved through a novel query algorithm that combines discriminative and confidence-based active learning approaches. This intelligent selection significantly minimizes the human-in-the-loop component, leading to substantial time savings and increased efficiency in cell sorting processes. The effectiveness of this active learning strategy is validated by benchmarking studies, demonstrating that ActSort achieves high accuracy with only a small fraction of annotations compared to random sampling or other conventional techniques. In essence, active learning is the core of ActSort’s efficiency and scalability, enabling the analysis of previously inaccessible datasets.

Feature Engineering#

The process of feature engineering in this research paper plays a crucial role in boosting the performance of automated cell sorting. The authors identify limitations in existing approaches, noting that they rely on a limited set of features and often fail to achieve human-level accuracy. To address this, they engineer a substantial set of novel features, drawing inspiration from the methods employed by human annotators. These engineered features explicitly capture spatiotemporal aspects of the cell activity and morphology that are often missed by simpler methods. This multi-faceted approach is a key innovation, enhancing the ability of machine learning models to discriminate effectively between true cells and false positives. The benchmarking study strongly supports the effectiveness of this strategy, demonstrating a significant increase in accuracy and efficiency over existing methods. The focus on mimicking human expertise in feature selection highlights a more sophisticated and effective approach to feature engineering in the context of high-dimensional biological data.

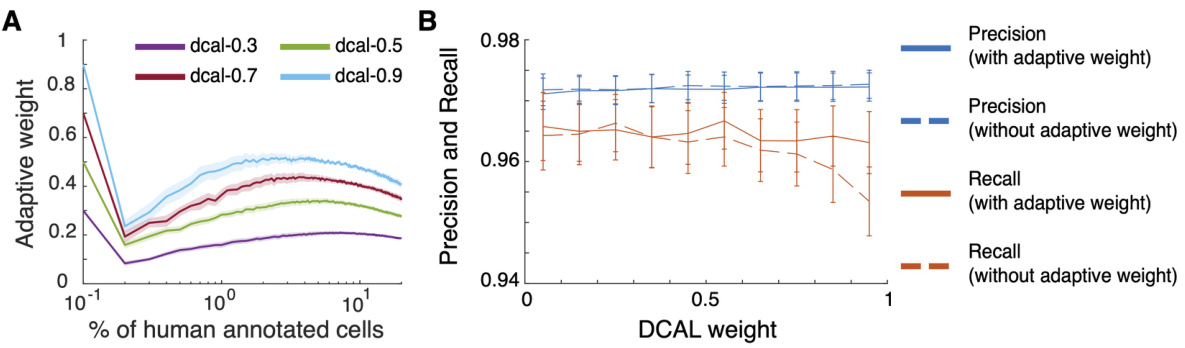

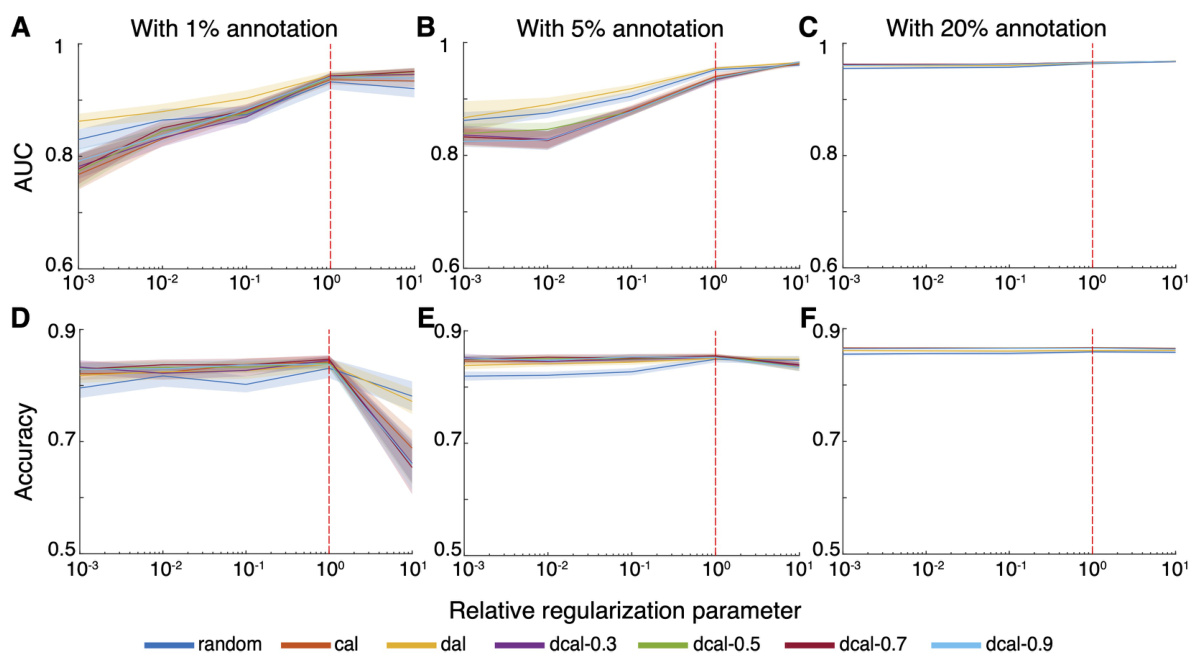

DCAL Algorithm#

The Discriminative-Confidence Active Learning (DCAL) algorithm represents a novel approach to active learning, particularly well-suited for cell sorting in large-scale calcium imaging datasets. DCAL cleverly combines the strengths of two existing active learning strategies: confidence-based active learning (CAL), which focuses on selecting uncertain samples near the decision boundary; and discriminative active learning (DAL), which prioritizes selecting diverse samples representative of the entire dataset. This hybrid approach addresses the limitations of each individual method. DCAL’s adaptive weighting mechanism is key: it dynamically balances the contributions of CAL and DAL throughout the annotation process, ensuring efficient exploration and exploitation of the data. Initially, DAL is emphasized to capture diverse samples, while later, the algorithm transitions towards CAL to efficiently focus on the most informative samples. This adaptive nature makes DCAL robust and parameter-free, reducing the need for meticulous hyperparameter tuning. The empirical evaluations demonstrate the effectiveness of DCAL, showcasing its ability to achieve high accuracy while minimizing human annotation effort compared to random sampling and other active learning methods, highlighting its potential for significant efficiency gains in large-scale biological image analysis.

ActSort’s Scalability#

ActSort demonstrates strong scalability for large-scale calcium imaging datasets. Its memory-efficient design, integrating compressed data formats and strategically selected annotations, avoids the computational bottleneck of processing terabyte-scale data common in systems neuroscience. Active learning further enhances scalability by significantly reducing the human annotation burden, typically to 1-3% of cell candidates, while maintaining high accuracy. ActSort’s performance is validated across various experimental conditions and datasets from multiple animals, showcasing its robustness and generalizability. The user-friendly software also promotes accessibility and widespread adoption among experimental neuroscientists, facilitating large-scale experiments that were previously infeasible. Overall, ActSort’s combination of efficient algorithms, data handling, and interactive annotation establishes a new standard for scalable cell sorting in systems neuroscience.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore integrating ActSort with other cell extraction algorithms, enhancing its generalizability across diverse experimental setups. Improving the active learning query algorithm by incorporating more sophisticated uncertainty estimations or employing a multi-class classification scheme for enhanced accuracy and efficiency could be explored. Further investigation is needed into how human annotator biases affect ActSort’s performance, potentially through advanced bias mitigation techniques. Addressing the computational limitations of the current approach, perhaps through optimized feature engineering or more efficient classifiers, is crucial for scalability. Finally, extending ActSort to other imaging modalities, such as voltage imaging or functional magnetic resonance imaging, could significantly broaden its applicability and impact on neuroscience research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the workflow of ActSort, an active learning-based cell sorting algorithm. The process begins with cell candidates identified from a calcium imaging movie. ActSort’s preprocessing module compresses the data to improve efficiency. A graphical user interface (GUI) allows human annotators to review and label candidates. The active learning module selects informative candidates for annotation, iteratively improving the algorithm’s accuracy. The output shows probabilities and labels for each cell.

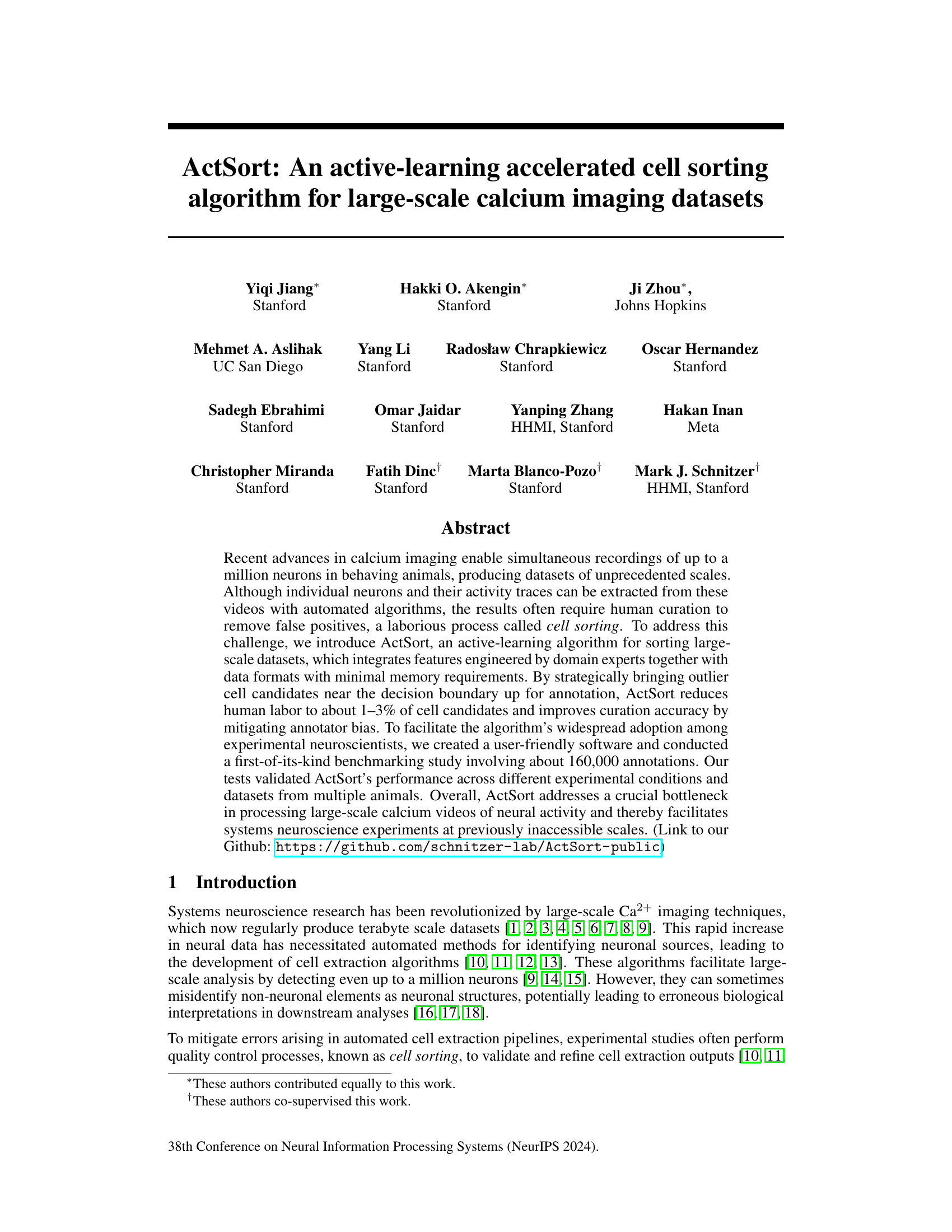

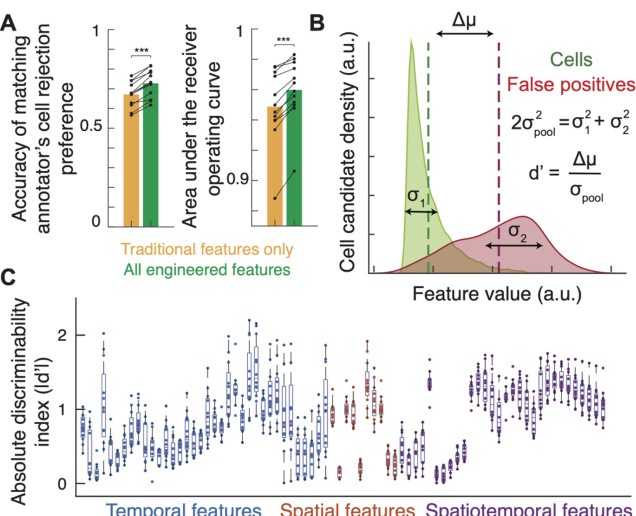

This figure demonstrates the impact of feature engineering on the accuracy of automated cell sorting using linear classifiers. Panel A shows that incorporating newly engineered features significantly improved the classifier’s ability to distinguish between true cells and false positives, as measured by the area under the ROC curve. Panel B visualizes the discriminability (d’) of individual features in separating cells from false positives, indicating the effectiveness of each feature. Panel C summarizes the overall discriminative power of the different feature types (temporal, spatial, and spatiotemporal), illustrating that many features effectively separated cells from false positives.

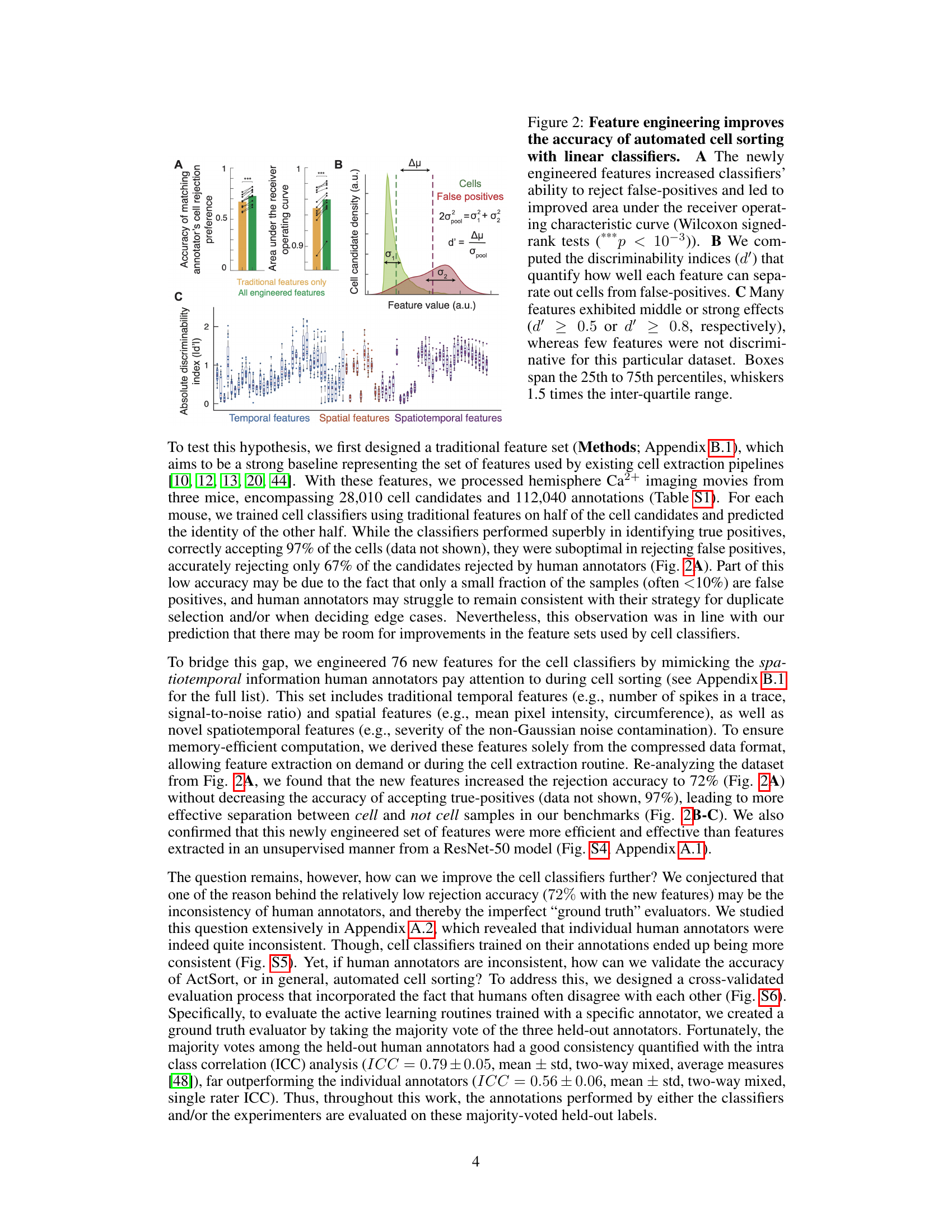

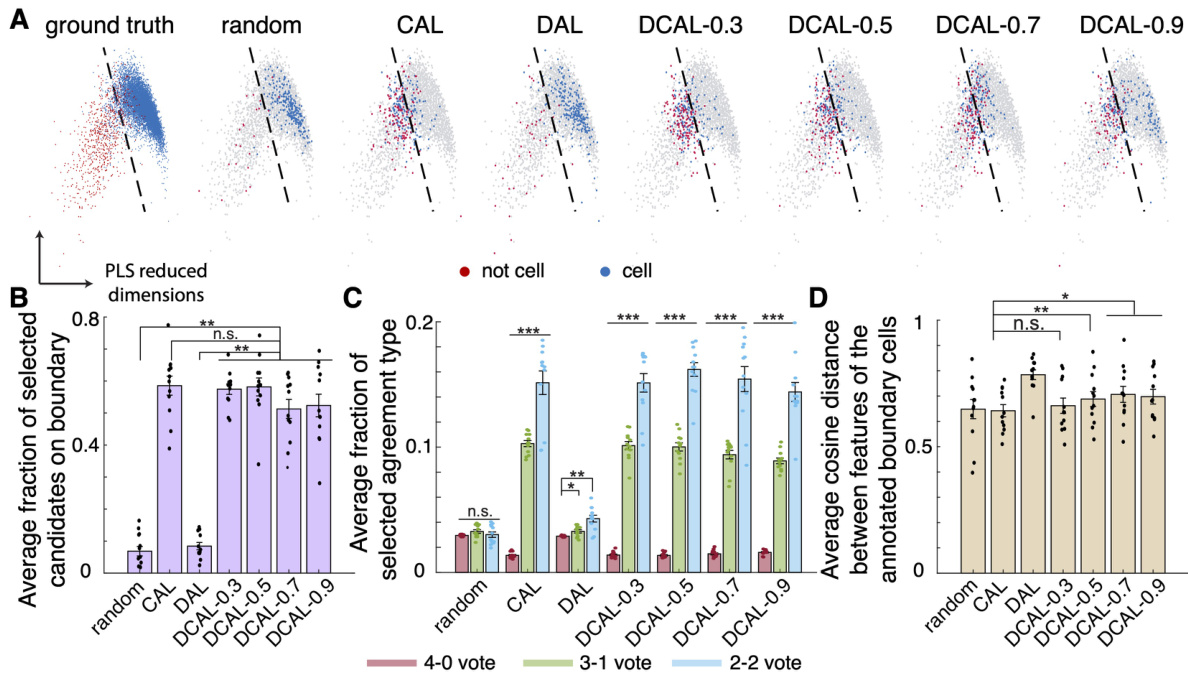

This figure shows the results of a comparison between four active learning query algorithms (random, CAL, DAL, and DCAL) in selecting samples for annotation. Dimensionality reduction was used to visualize the selected samples in a 2D space. The figure demonstrates that DCAL effectively selects outlier boundary samples which are diverse and near the decision boundary, leading to improved efficiency and accuracy in cell sorting compared to other methods.

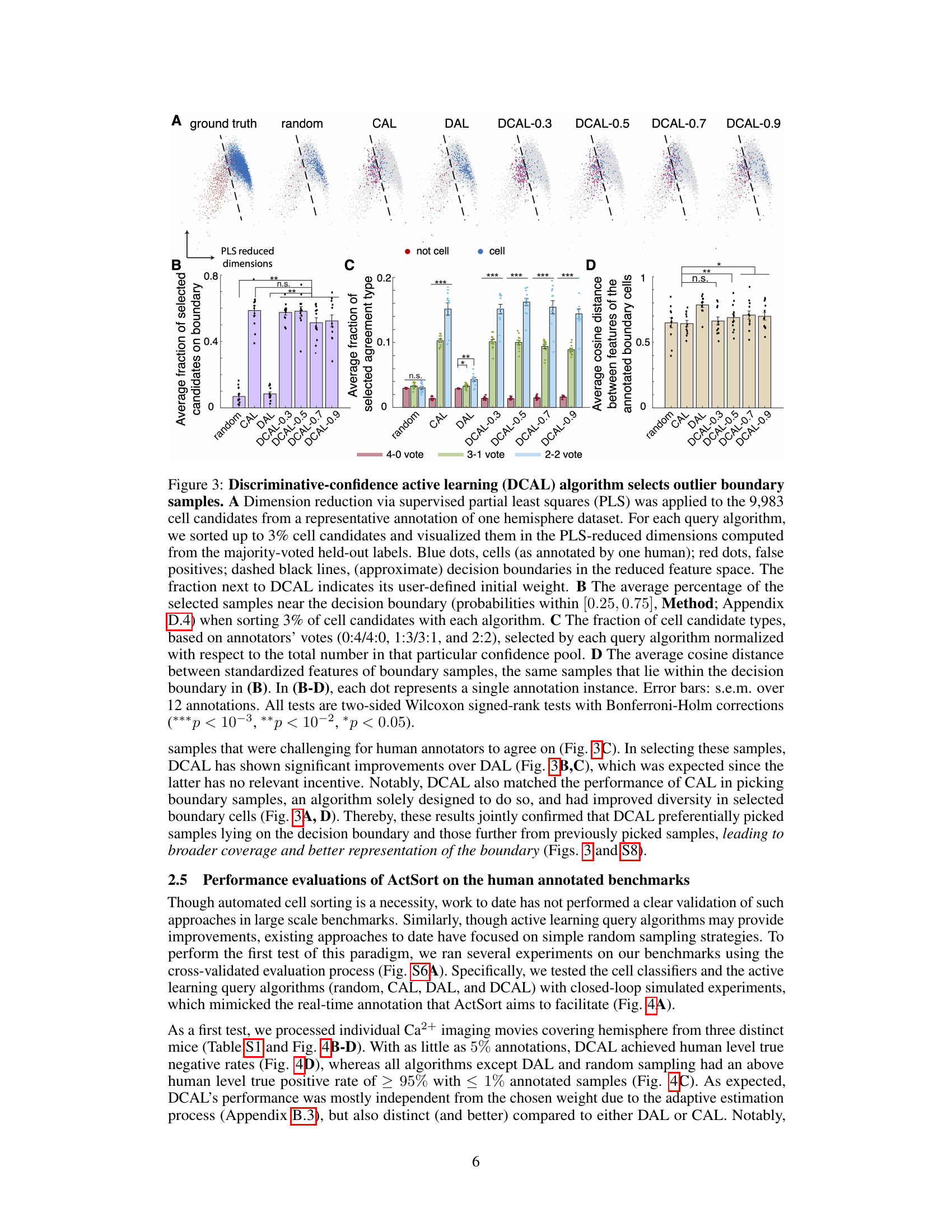

This figure demonstrates the performance of ActSort, a cell-sorting algorithm, compared to human annotators. It shows that ActSort, particularly using the DCAL query algorithm, achieves high accuracy with a significantly smaller number of annotations than human annotators across different experimental settings and combined datasets. The efficiency of ActSort is highlighted by its ability to reach human-level performance with only 1-3% of annotations compared to random sampling which require a much larger percentage.

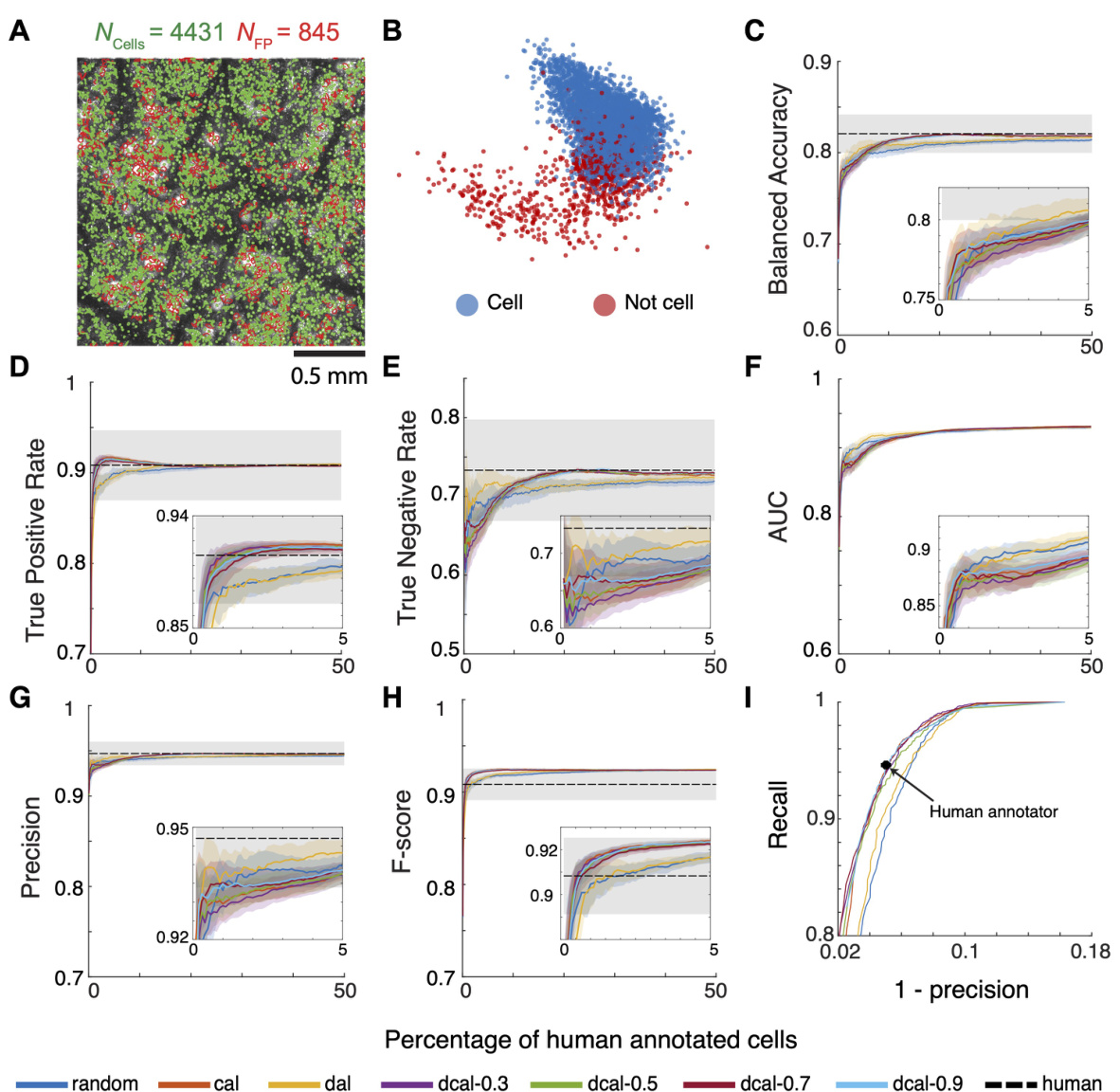

This figure demonstrates ActSort’s performance in cell sorting, comparing it against other active learning methods and random sampling. It shows that ActSort, using the discriminative-confidence active learning (DCAL) algorithm, significantly outperforms other methods in terms of balanced accuracy, true positive rate, and true negative rate, even with a very small percentage of human-annotated data. The experiment is performed on large-scale calcium imaging data and validates ActSort’s efficiency and accuracy across different experimental conditions and datasets from multiple animals.

This figure illustrates the ActSort workflow. The left panel shows the input: a Ca2+ imaging movie and cell candidates identified by a cell extraction algorithm. The middle panel shows the core of ActSort, including the preprocessing module for memory efficiency, the selection GUI for human annotation, and the active learning module for strategic sample selection. The right panel shows the output: labeled cells with associated probabilities.

This figure illustrates the ActSort workflow. The left side shows the input: a Ca2+ imaging movie and cell candidates from a cell extraction algorithm. The middle shows the core of ActSort: the preprocessing module (joint compression of movie and extraction results), the selection GUI (visual inspection and annotation), and the active learning module (strategic selection of candidates for annotation). The right side shows the output: labeled cells and their probabilities of being cells. ActSort uses an active learning approach to minimize human effort in validating the cell extraction results.

This figure illustrates the workflow of ActSort, an active learning algorithm for cell sorting in large-scale calcium imaging datasets. The process begins with input Ca2+ imaging movies and cell candidates from a cell extraction algorithm. ActSort’s preprocessing module efficiently compresses these data, computing quality metrics for each candidate. A user-friendly graphical user interface (GUI) allows human annotators to review candidates and label them as true positives or false positives. ActSort’s active learning module strategically selects the most informative candidates for annotation, reducing human effort and improving accuracy. Finally, ActSort outputs probabilities and binary classifications (cell or not cell) for each cell candidate.

This figure demonstrates that using engineered features significantly improves the accuracy of automated cell sorting. Panel A shows the improvement in the area under the ROC curve when using all engineered features compared to only using traditional features. Panel B illustrates the discriminability index (d’) for each feature, showing how well it separates cells from false positives. Panel C displays the distribution of d’ values, indicating that many features are highly discriminative.

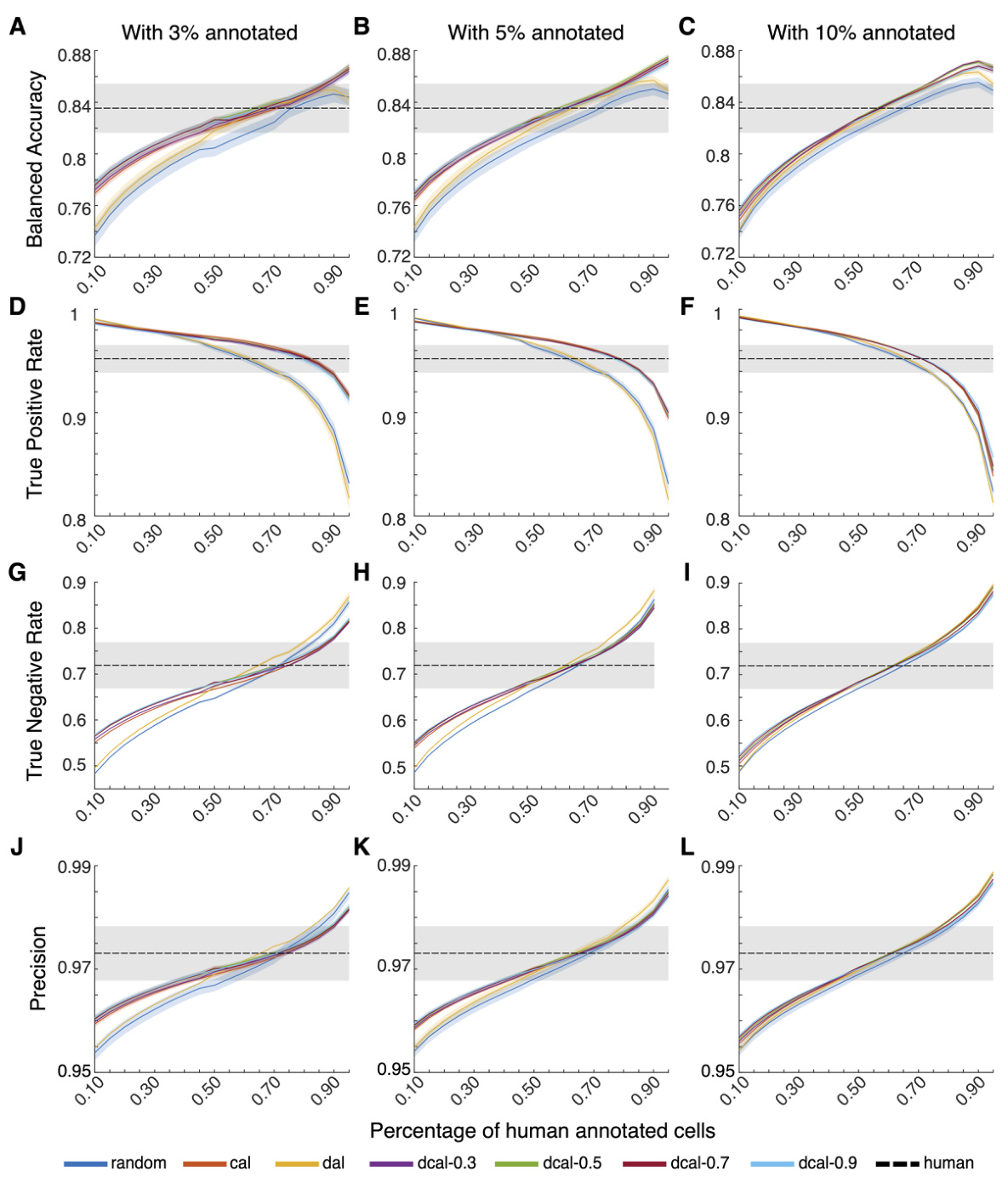

This figure demonstrates ActSort’s ability to generalize to new datasets using pre-trained classifiers. It shows that using pre-training with a subset of annotated data from one mouse enables faster convergence when annotating data from a new mouse, compared to starting from scratch. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of ActSort across different query algorithms (random, CAL, DAL, and DCAL) in terms of balanced accuracy, true positive rate, and true negative rate.

This figure illustrates the ActSort workflow. The left side shows the input: a calcium imaging movie and the cell candidates identified by an automated cell extraction algorithm. The middle section details ActSort’s three main components: a preprocessing module (jointly compressing the movie and cell extraction results), a graphical user interface (GUI) for visual inspection and annotation, and an active learning module (strategically selecting cells for annotation). The right side shows the output: labeled cells with associated probabilities (cell or not cell).

This figure demonstrates that the discriminative-confidence active learning (DCAL) algorithm effectively selects outlier boundary samples for annotation, improving the efficiency of the cell sorting process. It shows the distribution of selected samples in a reduced feature space for different query algorithms (random, CAL, DAL, and DCAL with various weights) and compares their performance in terms of boundary sample selection, diversity, and agreement with human annotators. DCAL shows a superior balance of selecting boundary samples and achieving diverse coverage.

This figure compares four different active learning query algorithms (random, CAL, DAL, and DCAL) in terms of their ability to select boundary samples for annotation in a cell sorting task. DCAL, a novel algorithm combining aspects of CAL and DAL, demonstrates superior performance in selecting outlier boundary samples, leading to more effective and efficient annotation.

This figure shows the geometrical interpretation of different query algorithms (random, CAL, DAL, and DCAL) for active learning in cell sorting. It uses dimension reduction to visualize how each algorithm selects samples for annotation, highlighting DCAL’s ability to select outlier boundary samples that provide broad coverage and better representation of the boundary.

This figure demonstrates the ActSort algorithm’s ability to handle two-photon calcium imaging movies that contain residual motion artifacts. The residual motion created duplicate cell candidates. Despite this, ActSort accurately identifies and classifies cells, showing similar results (balanced accuracy, true positive rate, true negative rate, AUC, precision, F-score, and recall) compared to human annotators. The results are presented in several subplots and highlight the algorithm’s robustness even under challenging imaging conditions.

This figure shows the geometrical interpretation of different active learning query algorithms (random, CAL, DAL, and DCAL) by visualizing their sample selection in a reduced feature space. It demonstrates that DCAL effectively selects samples near the decision boundary while maintaining diversity, improving the efficiency and accuracy of cell sorting.

This figure demonstrates that the discriminative-confidence active learning (DCAL) algorithm effectively selects outlier boundary samples for annotation. It compares DCAL’s performance to other query algorithms (random, CAL, DAL) by visualizing sample selections in a reduced feature space and quantifying the percentage of boundary samples, the distribution of candidate types, and the average cosine distance between selected samples. The results show DCAL’s superior ability to select diverse boundary samples, leading to improved efficiency in reducing annotation effort.

This figure demonstrates how different query algorithms in ActSort select samples for annotation. Dimensionality reduction is used to visualize the samples in a 2D feature space. It shows that DCAL effectively selects samples near the decision boundary, balancing the selection of true and false positives, while also ensuring good coverage across the feature space. The results demonstrate the advantages of DCAL over random, CAL, and DAL.

This figure demonstrates how different active learning query algorithms select samples for annotation. It shows that the discriminative-confidence active learning (DCAL) algorithm effectively selects samples near the decision boundary, while maintaining diversity and focusing on outlier samples. The results are visualized using a dimensionality reduction technique and various metrics are provided to quantify the performance of each algorithm.

More on tables

This table presents the results of a human annotation benchmark for a one-photon neocortex dataset. The dataset contained many false positives (incorrectly identified cells). Four annotators independently labeled the cells. The table shows the accuracy of each annotator in identifying true positives (correctly labeled cells) and true negatives (correctly rejected cells), compared against the labels from each of the other annotators. The average balanced accuracy across annotators was approximately 83%. Figure S9 provides more visual information about the data.

This table presents the results of a human annotation benchmark for a two-photon calcium imaging dataset. It shows the agreement between different annotators on whether each of 5,276 cell candidates is a true cell or a false positive. The teal numbers represent the accuracy of correctly identifying cells, and the red numbers represent the accuracy of rejecting false positives. The average balanced accuracy across annotators was approximately 78%.

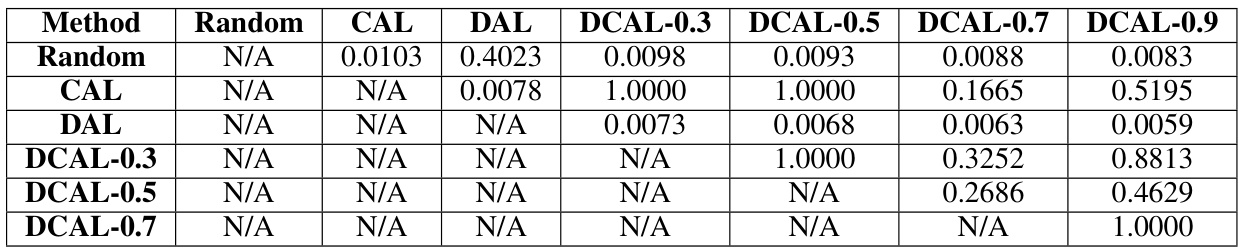

This table shows the p-values from Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Bonferroni-Holm correction, comparing the fraction of boundary samples selected by different query algorithms (Random, CAL, DAL, and DCAL with different weights). The tests assess statistical significance of differences in boundary sample selection between the methods. The data comes from Figure 3B of the paper, with 12 data points per algorithm.

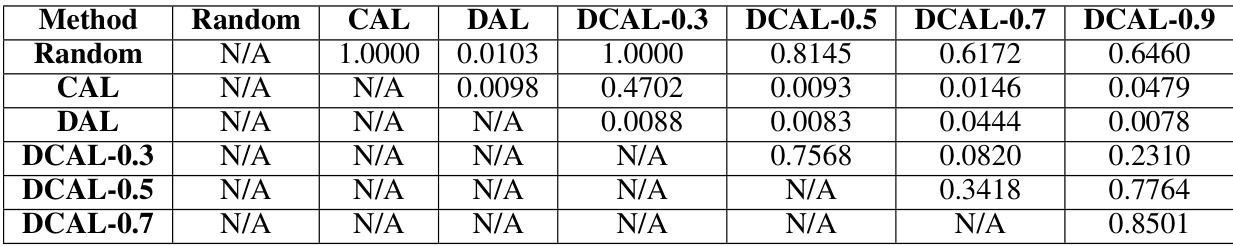

This table shows the p-values from Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Bonferroni-Holm corrections, assessing the statistical significance of differences in average cosine distances between boundary samples across different active learning query algorithms. The tests compared algorithms’ effectiveness in selecting diverse boundary samples. Twelve data points per algorithm (3 datasets × 4 annotators) were used. Random subsampling was applied to ensure fair comparisons between algorithms with varying numbers of selected samples.

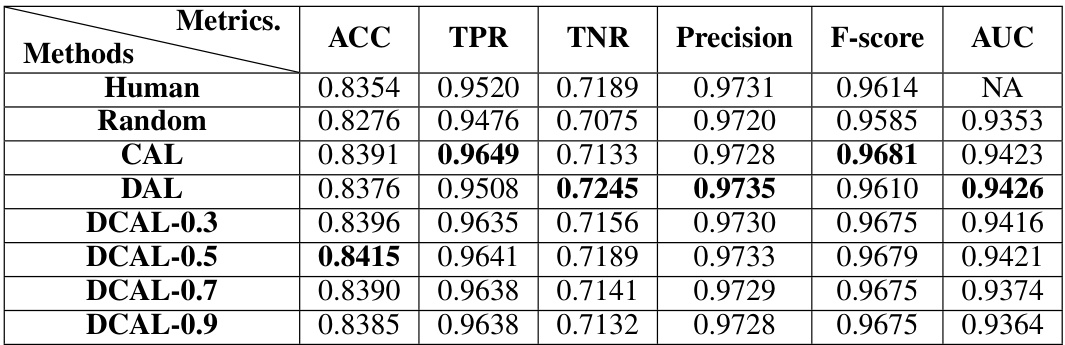

This table presents the performance of ActSort and other methods after annotating only 5% of the cells in the hemisphere dataset. It shows the balanced accuracy, true positive rate, true negative rate, precision, F1-score, and AUC for each method. The results are averaged over 12 annotators and three datasets. The full performance of each method up to 50% annotation is illustrated in figures 4B-D and S13B in the paper.

This table presents the performance of ActSort and other active learning algorithms after annotating 5% of the cells in the hemisphere dataset. The metrics used to evaluate performance are balanced accuracy (ACC), true positive rate (TPR), true negative rate (TNR), precision, F-score, and area under the ROC curve (AUC). The table shows that DCAL outperforms other methods, achieving near human-level performance with only 5% of the cells labeled.

This table presents the performance of ActSort’s active learning algorithms when annotating only 2% of the cells in the batch-processed dataset. It shows various metrics (balanced accuracy, true positive rate, true negative rate, precision, F-score, and AUC) for different active learning strategies (random sampling, CAL, DAL, and DCAL with varying weights). The results highlight the relative performance of these methods at a very early stage of the annotation process, before convergence.

Full paper#