↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current active learning methods for video captioning often struggle due to inconsistent human annotations, leading to suboptimal model performance. This paper identifies this as a ’learnability’ problem, highlighting that collective outliers—videos with highly variable annotations—are particularly challenging to learn.

The researchers propose a new active learning algorithm that directly addresses this issue by incorporating ’learnability’ alongside the traditional measures of diversity and uncertainty. Their approach leverages predictions from pre-trained vision-language models to estimate annotation consistency, effectively identifying easier-to-learn samples. A novel caption-wise annotation protocol further enhances efficiency by focusing human effort on the most informative captions. Results demonstrate substantial performance gains on benchmark datasets, suggesting the significant potential of their approach for real-world video captioning applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it tackles a critical, yet often overlooked problem in active learning for video captioning: the impact of inconsistent human annotations. By introducing the concept of ’learnability’ and proposing a novel active learning algorithm, this research offers a significant improvement over existing methods. It also provides valuable insights into how to leverage human knowledge more efficiently in complex tasks. Its findings could potentially reshape the field of active learning and inspire new research directions in video captioning and related areas.

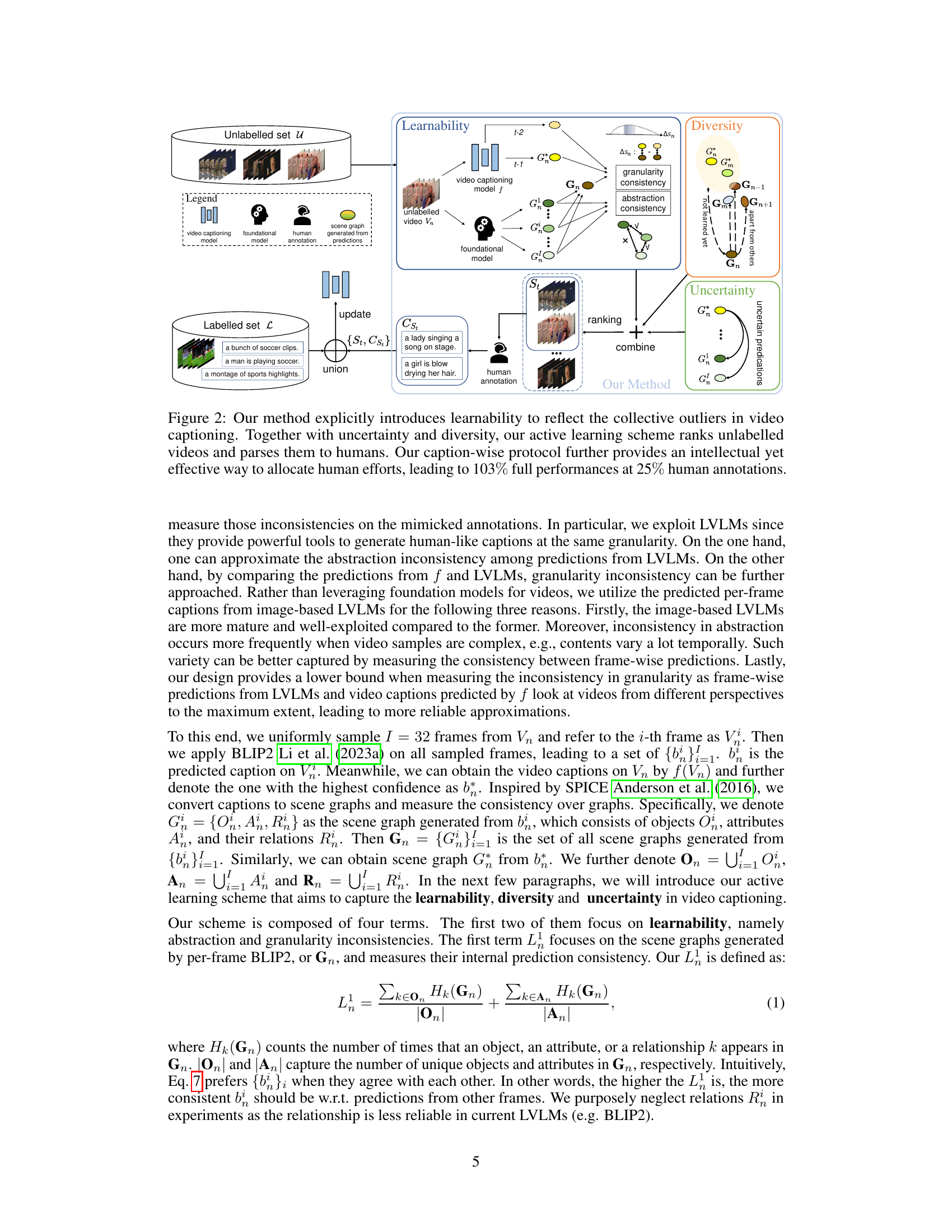

Visual Insights#

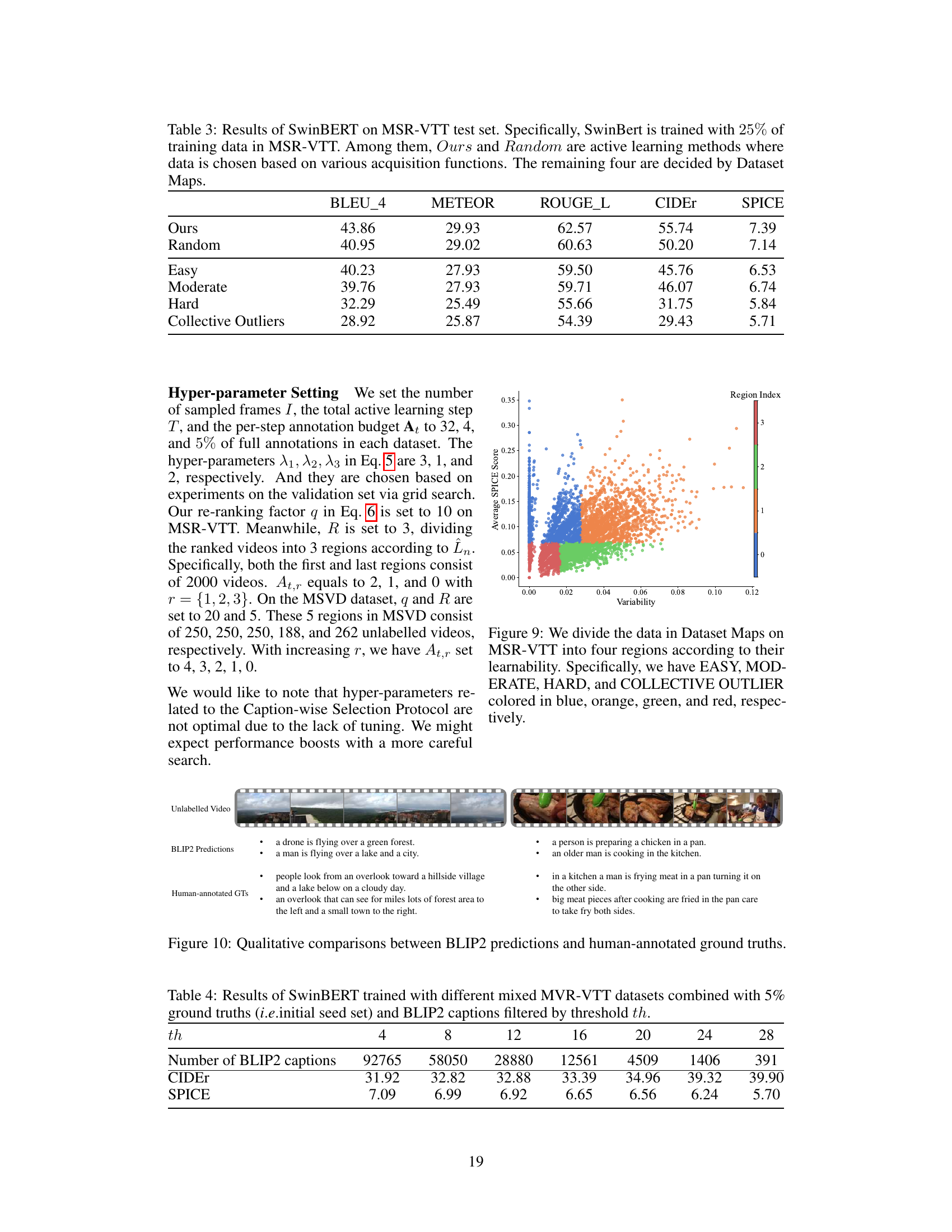

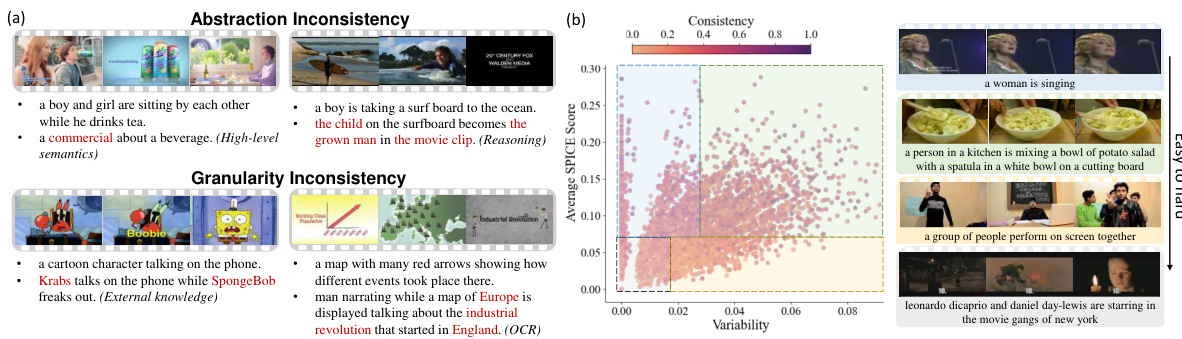

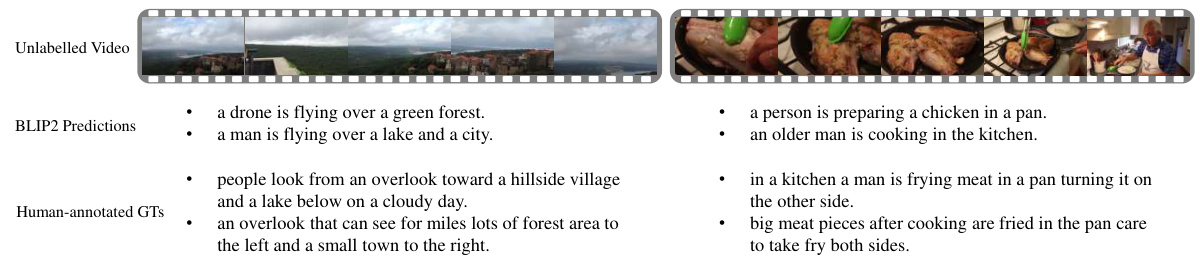

This figure shows examples of collective outliers in video captioning and how they are caused by abstraction and granularity inconsistencies in human annotations. The (a) part illustrates these inconsistencies with specific examples. The (b) part is a Dataset Map visualizing the average SPICE score (reflecting annotation quality) against variability across training epochs for the MSR-VTT dataset. The plot is divided into four quadrants representing different levels of learnability (ease of learning for the model) based on the consistency and variability of SPICE scores. Examples of captions from each quadrant further illustrate the concept of learnability.

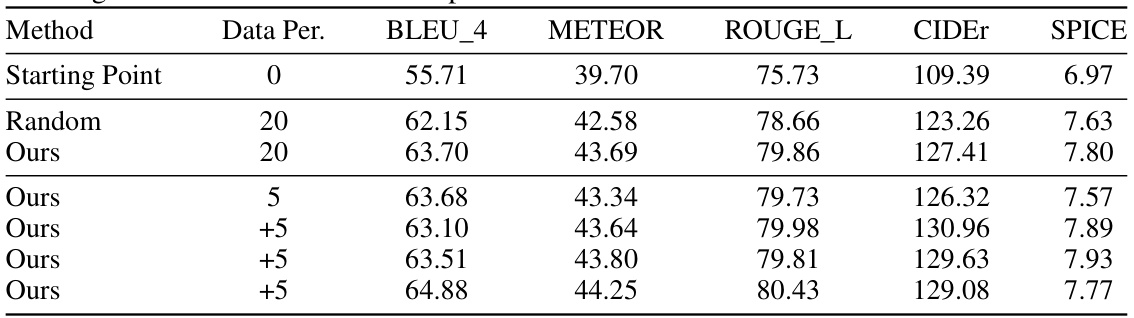

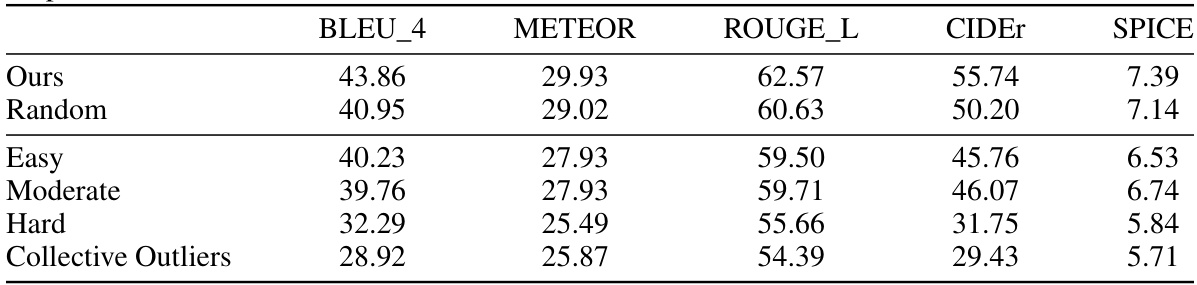

This table presents the results of an experiment where the model was initially trained on the fully annotated MSVD dataset. Then, the active learning algorithm was used to select additional data from the large, unannotated MSR-VTT dataset. The table shows the performance (using BLEU_4, METEOR, ROUGE_L, CIDEr, and SPICE metrics) on the MSVD test set after adding different percentages of data from MSR-VTT. The ‘Starting Point’ row shows the initial performance before any data from MSR-VTT was added. The ‘Random’ row shows the performance when data from MSR-VTT was randomly selected. The rows labeled ‘Ours’ show the performance after using the proposed active learning algorithm to select data from MSR-VTT, with varying amounts added at each step.

In-depth insights#

Learnability’s Role#

Learnability is a crucial, often overlooked, aspect of active learning in video captioning. Ground truth inconsistency, stemming from variations in human annotations (abstraction and granularity differences), significantly impacts model performance. The paper highlights that addressing this learnability challenge is vital for effective active learning. By incorporating a measure of learnability alongside traditional active learning metrics (diversity, uncertainty), the proposed method leverages estimated ground truths from pre-trained vision-language models to identify and prioritize more consistent, easier-to-learn samples for annotation. This approach focuses on mitigating the impact of collective outliers and improving overall accuracy using fewer human annotations. The results demonstrate that explicitly addressing learnability leads to substantial gains in performance compared to state-of-the-art methods. This research emphasizes the importance of understanding and incorporating learnability into active learning strategies, suggesting a more nuanced and sophisticated approach to sample selection than simply focusing on uncertainty and diversity.

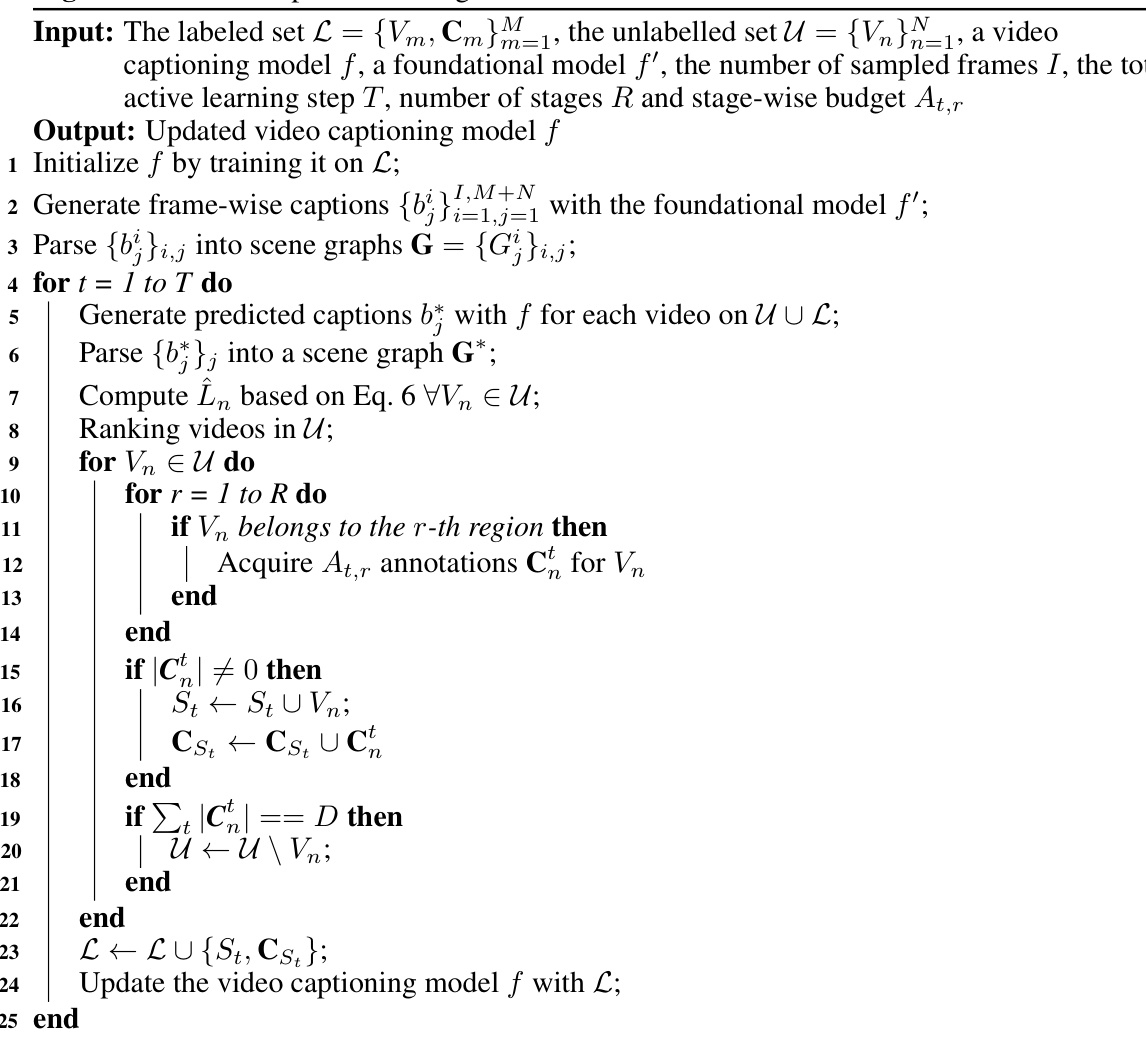

Active Learning Algo#

An active learning algorithm strategically selects data points for labeling, aiming to maximize model performance with minimal annotation effort. Effective algorithms balance exploration (sampling diverse data) and exploitation (focusing on uncertain data points). The choice of acquisition function, which scores data points based on informativeness, is critical. Popular methods include uncertainty sampling, query-by-committee, and expected model change. The algorithm’s success is heavily reliant on the quality of the acquisition function and how well it represents the model’s needs. Practical considerations often involve batch selection to reduce annotation costs and computational overhead. A successful strategy often combines multiple acquisition criteria (e.g., balancing uncertainty with diversity) to produce a more robust learning process. Considerations also include dealing with noise in labels and the computational complexity of the algorithm itself.

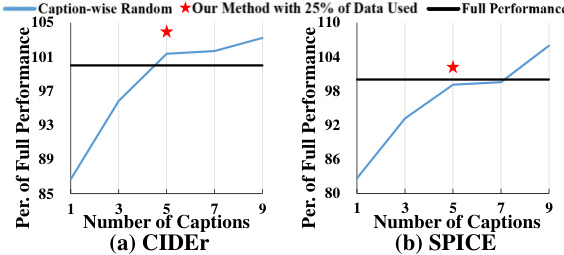

Caption-Wise Protocol#

The proposed caption-wise protocol offers a significant advancement in active learning for video captioning by addressing the limitations of traditional video-based selection methods. Instead of acquiring all annotations for a selected video, this approach intelligently selects a subset of captions, thereby mitigating the negative impact of annotation inconsistencies (collective outliers). This strategy reduces annotation costs while improving data quality and model performance. The protocol leverages the observation that fewer annotations per video lead to less inconsistency, and thus, better model learning. By strategically allocating annotation resources, the caption-wise protocol optimizes human effort, allowing for more diverse video selection and maximizing overall model improvement with minimal human intervention. The intellectual and effective human-effort allocation of this method contrasts sharply with the inefficient video-based methods, demonstrating a substantial improvement in active learning efficiency and effectiveness.

Dataset Map Analysis#

Dataset Map analysis offers a powerful visual tool for understanding the characteristics of a dataset, particularly in revealing the presence and impact of collective outliers. By plotting average performance metrics (like SPICE scores) against their variability across training epochs, a Dataset Map can effectively stratify samples into distinct learnability categories: easy, moderate, hard, and collective outliers. This visualization is crucial for active learning strategies, allowing researchers to prioritize samples with high uncertainty and moderate difficulty for annotation, thereby maximizing model improvement with limited human effort. A key strength of this approach is its ability to highlight the less obvious, yet impactful, collective outliers, which are difficult to identify individually but significantly hinder model training. This analysis provides a deeper, more nuanced understanding than simpler uncertainty-based sampling methods, leading to more informed decisions in the active learning process and ultimately, better model performance. The insights from a Dataset Map can guide the design of better active learning algorithms, focusing efforts on data points that will generate a significant return in improved model capabilities.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on active learning for video captioning could explore several promising avenues. Improving the robustness and generalizability of the proposed method by testing on more diverse datasets and video captioning models is crucial. Investigating alternative ways to estimate sample learnability beyond using pre-trained Vision-Language Models would enhance the method’s reliability and independence from external resources. A deeper investigation into the inherent inconsistencies in human annotations, perhaps using more advanced techniques or larger-scale human studies, could yield more refined models for handling such inconsistencies. Furthermore, exploring alternative active learning protocols beyond the caption-wise approach, while potentially more computationally expensive, may prove beneficial in scenarios where capturing comprehensive context is paramount. Finally, combining this active learning approach with other techniques, such as semi-supervised or transfer learning, could significantly improve overall performance and efficiency in annotating large video datasets. This multifaceted approach would lead to a more robust and effective video captioning system.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the proposed active learning method for video captioning. The method incorporates three key aspects: learnability (to address collective outliers), diversity (to select a variety of samples), and uncertainty (to prioritize samples with less reliable predictions). The process begins by evaluating an unlabeled set of videos using a video captioning model and a foundational model. The foundational model generates approximate ground truths to estimate the learnability of each video. Then, the method combines the learnability, diversity, and uncertainty scores to rank unlabeled videos. Finally, it selects the highest-ranked videos for human annotation using a caption-wise protocol to optimize human effort. This figure shows the workflow and highlights the key components of the proposed method.

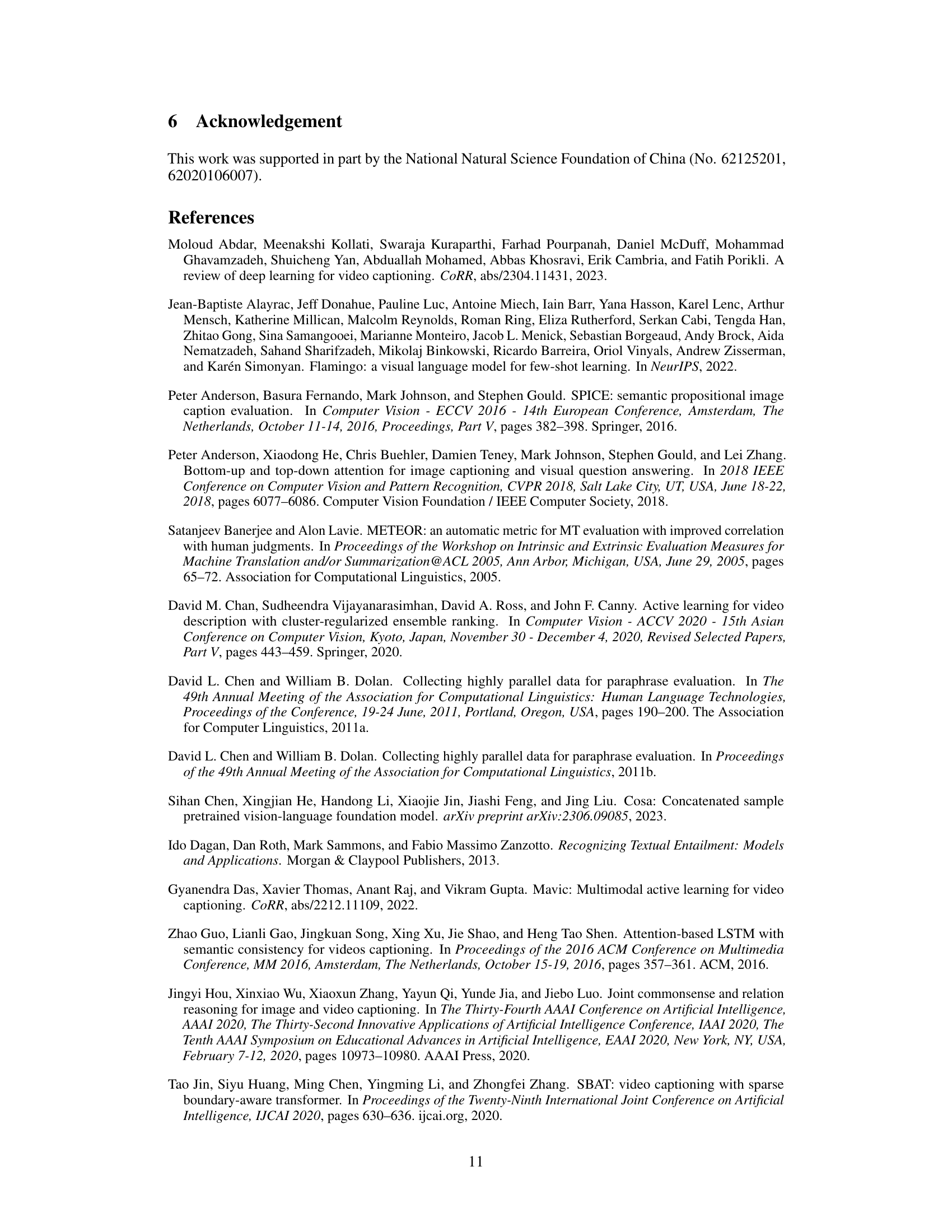

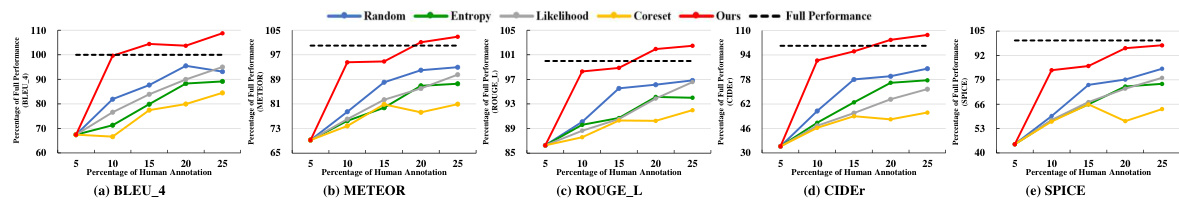

This figure shows the performance comparison of different active learning methods on the MSVD dataset. The x-axis represents the percentage of human annotations used, while the y-axis represents the percentage of full performance achieved on various metrics (BLEU-4, METEOR, ROUGE-L, CIDEr, and SPICE). The results show that the proposed method (‘Ours’) consistently outperforms other baselines, such as random sampling, maximum entropy, minimum likelihood, and coreset selection, across all metrics and annotation percentages. For several metrics, ‘Ours’ even surpasses the full performance achieved when using 100% of human annotations. The plot includes error bars to illustrate variability.

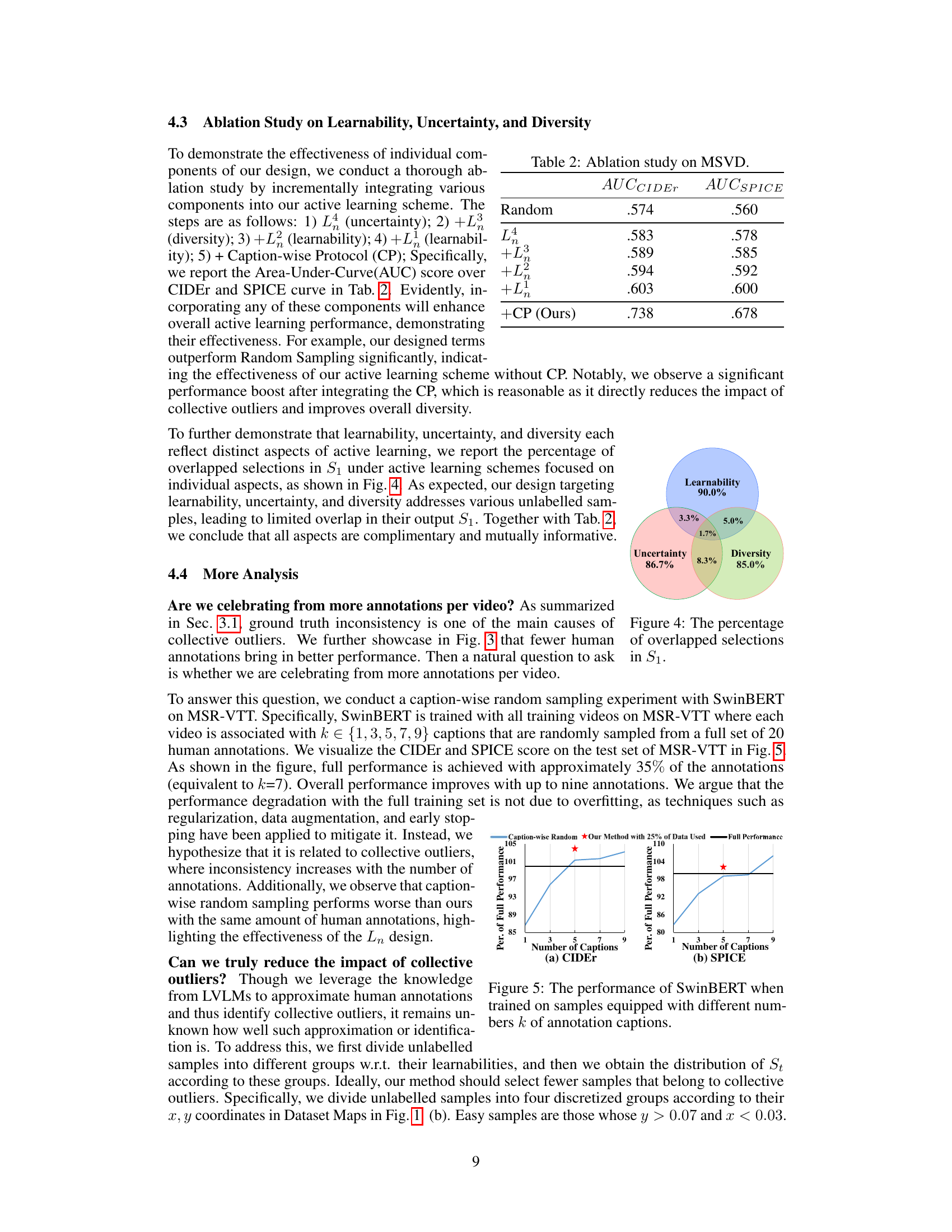

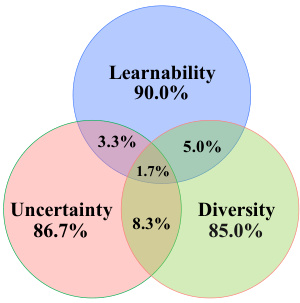

This Venn diagram shows the overlap between samples selected by active learning methods focusing on learnability, uncertainty, and diversity individually. The large, non-overlapping portions indicate that each criterion selects a significantly different subset of samples. The small overlaps demonstrate that these three criteria complement one another in identifying valuable unlabeled datapoints for training a video captioning model.

This figure displays the results of an active learning experiment on the MSVD video captioning dataset. The x-axis represents the percentage of human annotations used for training, while the y-axis shows the performance of various active learning methods relative to the performance achieved with 100% of human annotations (the full performance). The figure shows that the proposed method (‘Ours’) consistently outperforms other state-of-the-art (SOTA) active learning methods across multiple evaluation metrics (BLEU4, METEOR, ROUGE-L, CIDEr, and SPICE), achieving nearly or even exceeding the full performance with significantly less human annotation.

This figure shows the distribution of selected samples (S1) categorized by their learnability (Easy, Moderate, Hard, Collective Outliers) for different active learning methods. The method proposed in the paper (‘Ours’) shows a significantly higher proportion of easy samples and a lower proportion of collective outliers, highlighting its effectiveness in selecting less challenging and more reliable samples for annotation.

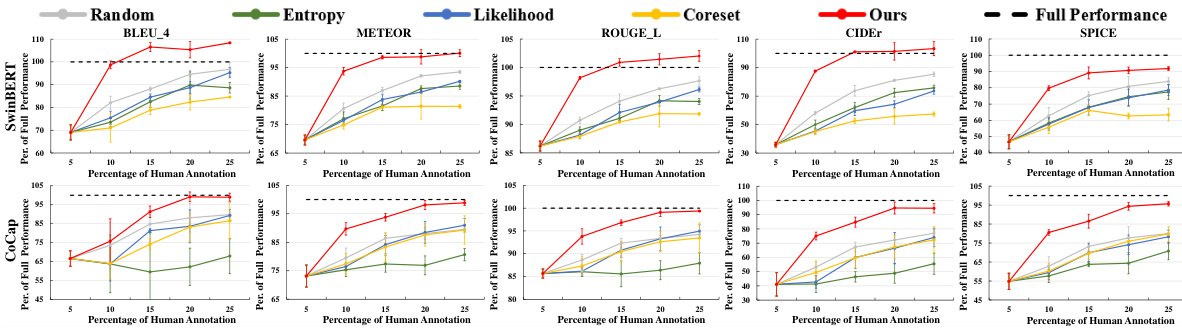

This figure compares the performance of different active learning methods on the MSVD dataset across five evaluation metrics (BLEU-4, METEOR, ROUGE-L, CIDEr, and SPICE) using two different backbones (SwinBERT and CoCap). The x-axis represents the percentage of human annotations used, and the y-axis shows the performance relative to the full performance achieved with 100% annotations. The results demonstrate that the proposed method (‘Ours’) consistently outperforms other methods, including random sampling, maximum entropy, minimum likelihood, and coreset selection, across all metrics and backbones. The method achieves performance exceeding 100% of the full performance with a relatively small percentage of human annotations.

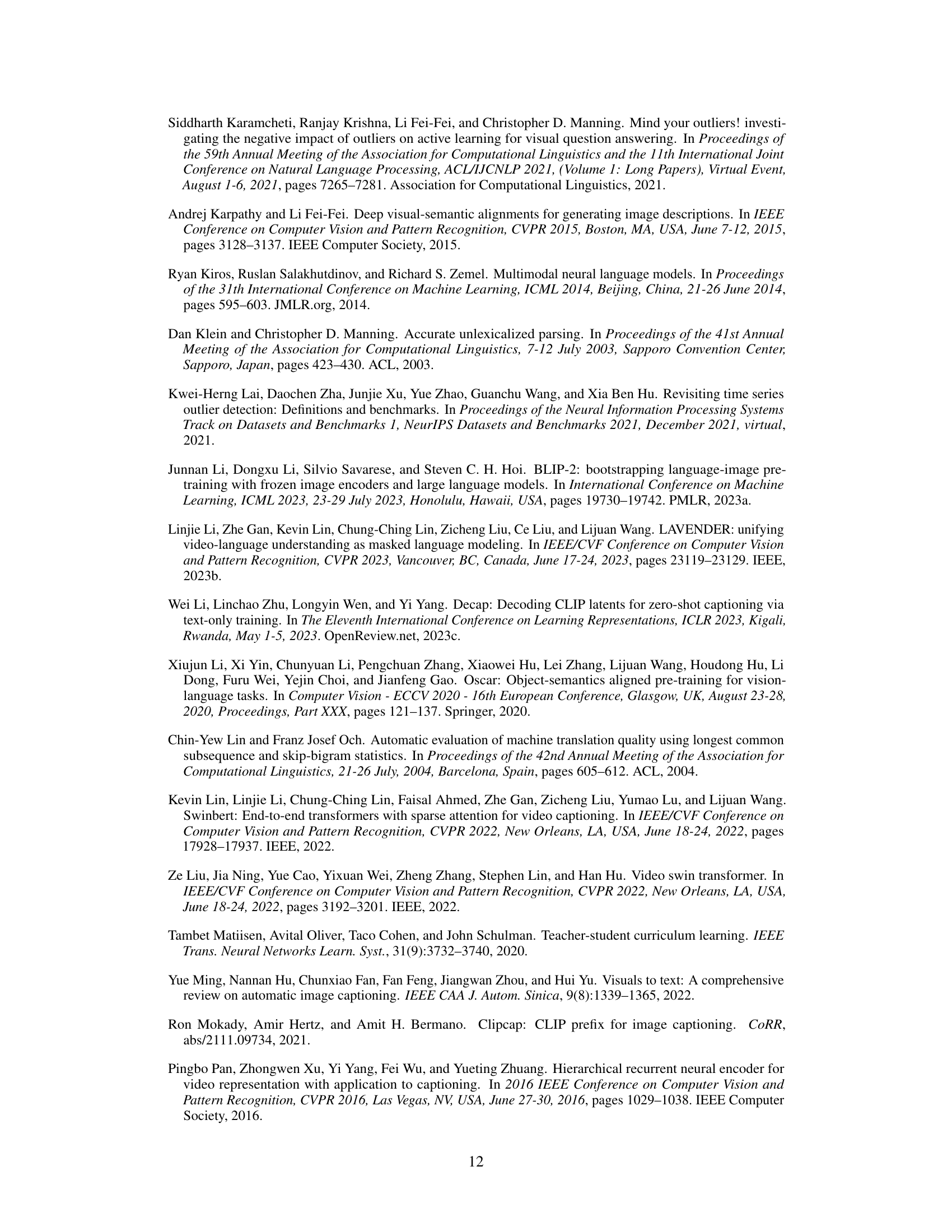

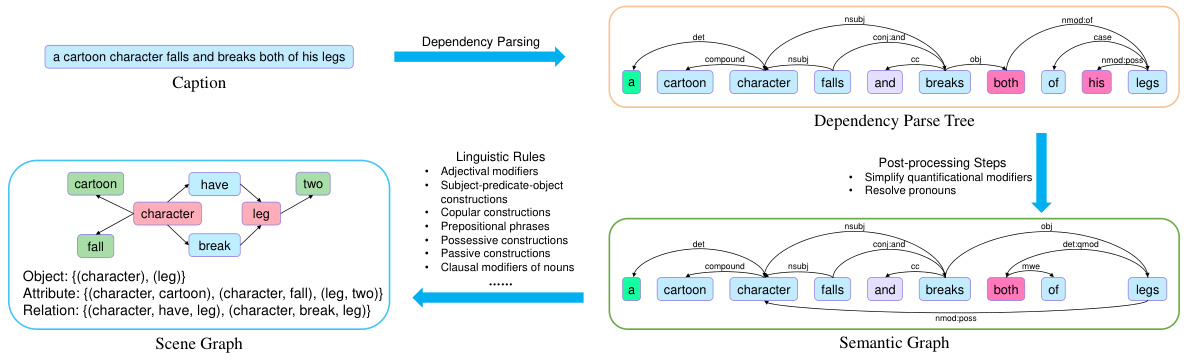

This figure shows the process of generating a scene graph from a caption. It begins with a caption, which undergoes dependency parsing to create a dependency parse tree. Linguistic rules are then applied to transform this parse tree into a semantic graph. Finally, post-processing steps like simplifying quantificational modifiers and resolving pronouns produce the final scene graph, which includes objects, attributes, and relations. The example shown illustrates the steps involved in processing the caption ‘a cartoon character falls and breaks both of his legs.’ The resulting scene graph represents the key elements and their relationships.

This figure illustrates the proposed active learning method for video captioning. The method incorporates three key aspects: learnability (to address collective outliers), diversity, and uncertainty. It uses a novel caption-wise protocol to efficiently allocate human annotation effort. The diagram shows the flow of the algorithm, highlighting the selection of unlabeled videos based on learnability, diversity, and uncertainty scores, and how the selected videos are presented to human annotators for captioning. The caption-wise protocol ensures that only a limited number of human-annotated captions are requested for each selected video.

This figure shows the distribution of MSR-VTT training data points based on their average SPICE score (y-axis) and variability (x-axis), which represent the learnability and uncertainty of the data, respectively. The data is divided into four regions based on these two metrics, indicating different levels of learnability: EASY, MODERATE, HARD, and COLLECTIVE OUTLIERS. Each region is represented by a different color. The figure is used to demonstrate the property of Dataset Maps to diagnose the training process and identify collective outliers.

This figure shows examples of collective outliers in video captioning and how they relate to learnability. Part (a) illustrates two types of inconsistencies in human annotations that lead to outliers: abstraction inconsistency (different high-level interpretations of the same video) and granularity inconsistency (descriptions at varying levels of detail). Part (b) presents a Dataset Map, visualizing the average SPICE score (a video captioning evaluation metric) and its variability across training epochs for the MSR-VTT dataset. The map is divided into four quadrants based on variability and average SPICE score, representing different levels of learnability (ease of learning). Examples of captions from each quadrant are given to demonstrate varying learnability.

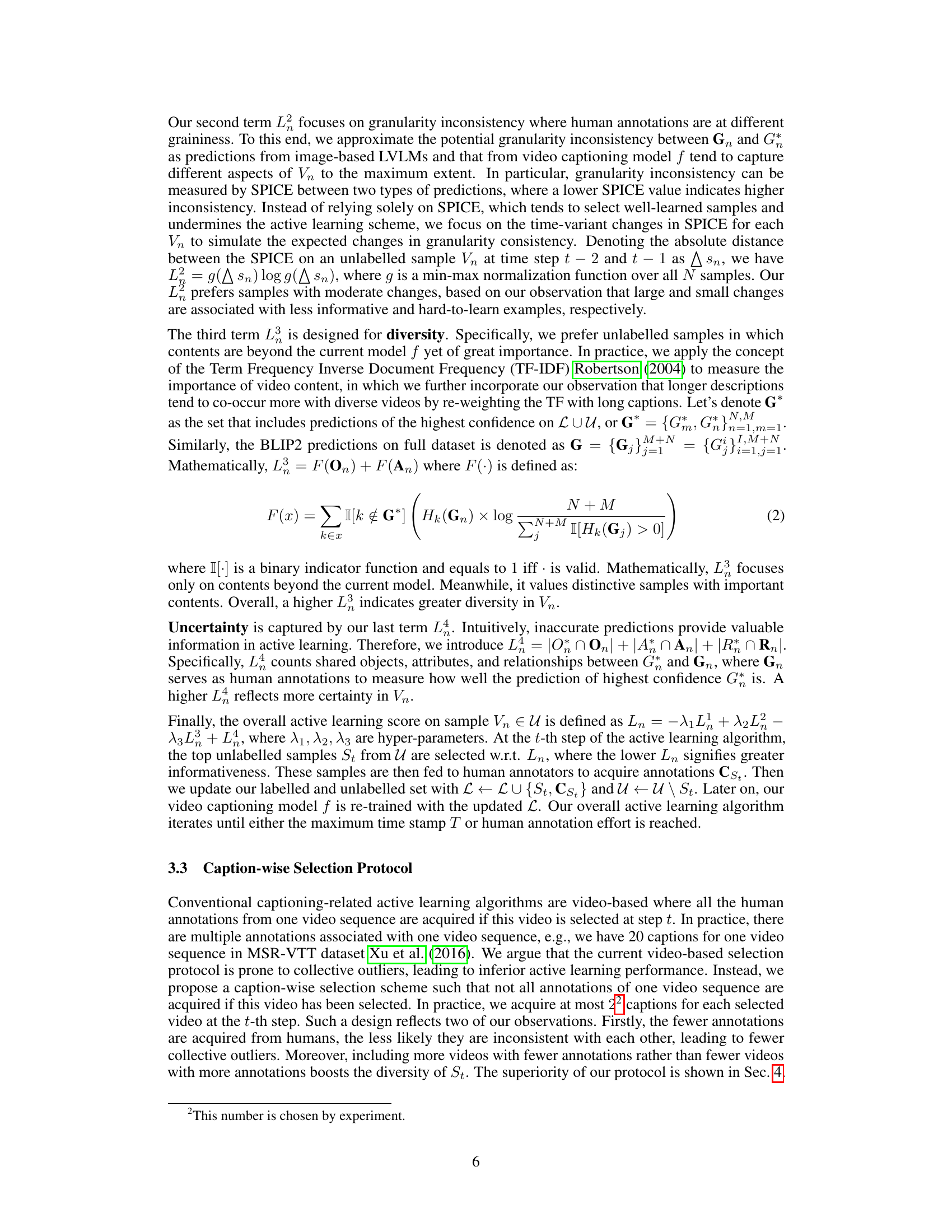

More on tables

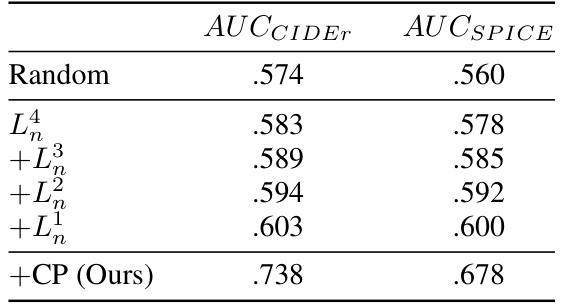

This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted on the MSVD dataset to evaluate the effectiveness of individual components of the proposed active learning scheme. The study incrementally integrates various components, starting with a baseline of random sampling, and then adding uncertainty (L4n), diversity (L3n), learnability (L2n), and finally the caption-wise protocol (CP). The Area Under the Curve (AUC) scores for CIDEr and SPICE are reported for each step, demonstrating the cumulative improvement in performance as components are added. The final row shows the results for the complete proposed method (+CP (Ours)).

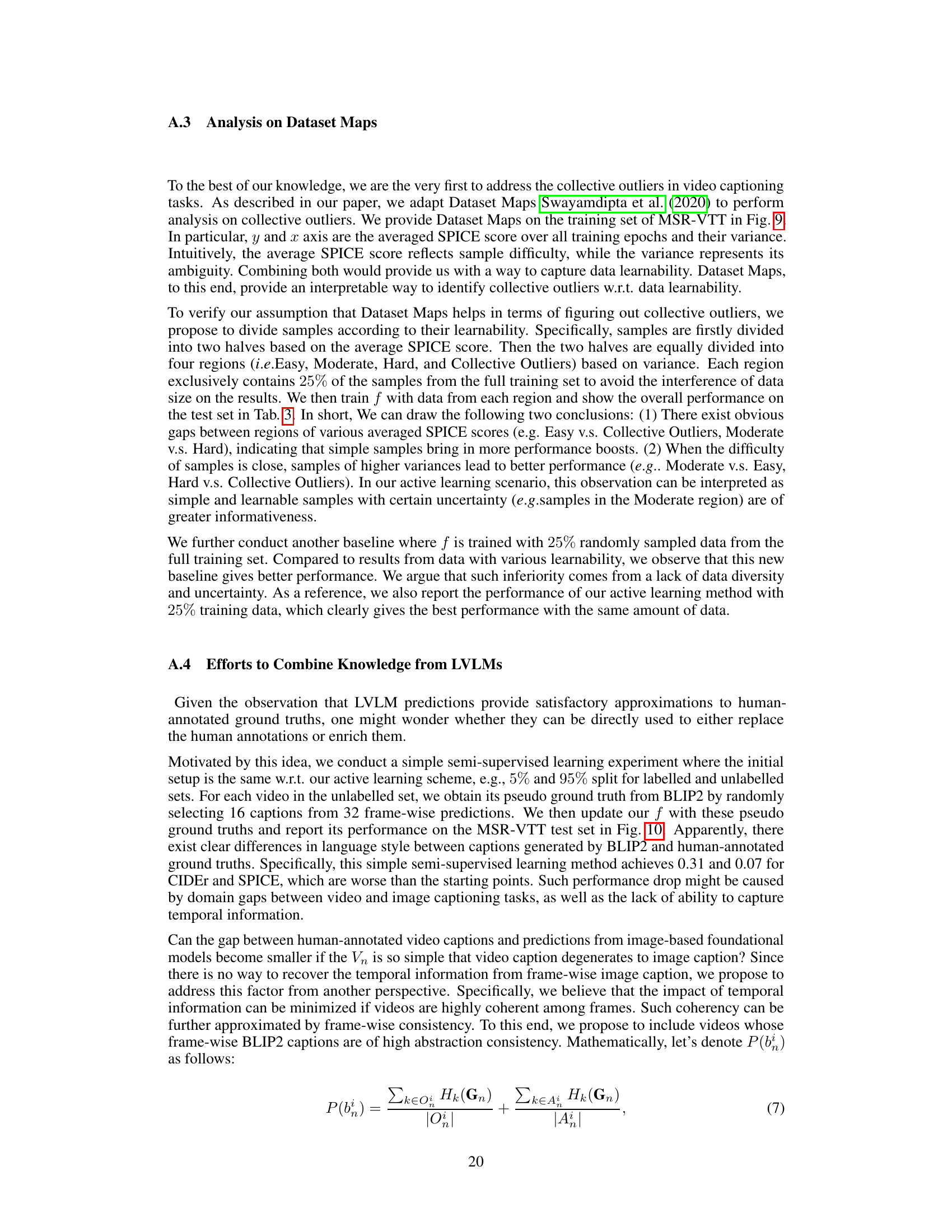

This table presents the results of using SwinBERT on the MSR-VTT test set. The model was trained with only 25% of the training data. The results compare the performance of the proposed active learning method (‘Ours’) against a random sampling baseline and four other methods based on different data selection strategies derived from Dataset Maps (Easy, Moderate, Hard, Collective Outliers). The metrics used to evaluate performance are BLEU-4, METEOR, ROUGE-L, CIDEr, and SPICE.

This table shows the results of using SwinBERT, a video captioning model, trained on different combinations of the MSR-VTT dataset and BLIP2 captions. The MSR-VTT dataset is a large video dataset used for training video captioning models, while BLIP2 captions are captions generated by a large language model. The experiment started with 5% of the original MSR-VTT dataset (ground truth) and then added varying numbers of BLIP2 captions based on different threshold values (th). The table reports the CIDEr and SPICE scores for each experimental setup. These metrics assess the quality of the generated captions compared to human-written captions. The results show how the performance of SwinBERT improves as more BLIP2 captions are added, up to a certain point, after which performance starts to decrease.

Full paper#