↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Text-to-image diffusion models often struggle to faithfully represent complex prompts due to limitations in how the CLIP text encoder processes attributes. This often results in improper attribute binding, where attributes are incorrectly associated with objects, leading to unrealistic or nonsensical image outputs. This is further exacerbated by contextual issues within the text encoding itself.

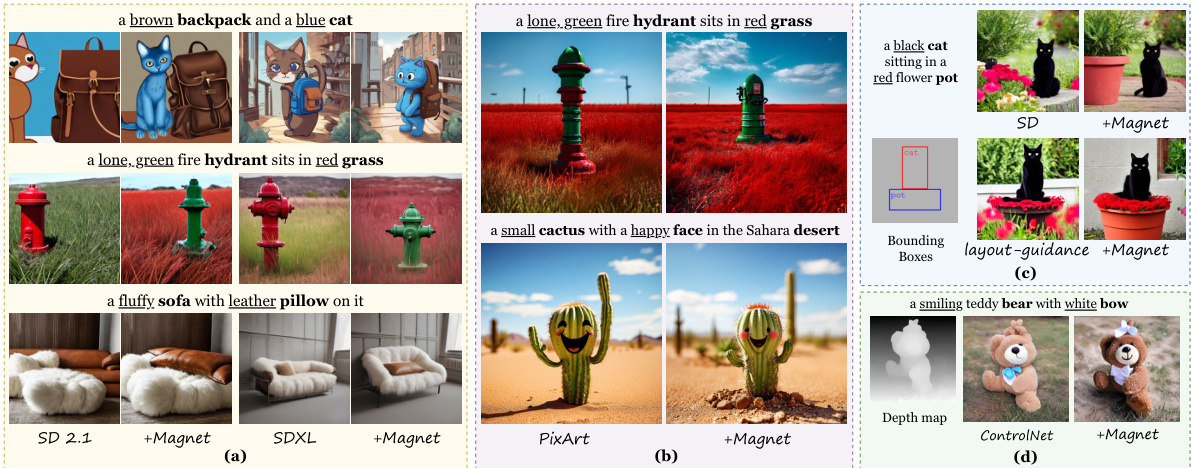

To address these shortcomings, the paper introduces Magnet, a novel training-free method. Magnet leverages positive and negative binding vectors to improve attribute disentanglement. It also employs a neighbor strategy to boost accuracy. The method operates solely within the text embedding space, requiring no model retraining or additional data. Experimental results demonstrate that Magnet substantially enhances image quality and binding accuracy with minimal computational overhead, enabling the generation of more complex and nuanced images.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it pinpoints a critical limitation in current text-to-image models and proposes a novel, computationally inexpensive solution. It directly addresses the problem of improper attribute binding, a major hurdle in generating high-quality images from complex prompts. This work opens up new avenues for improving the accuracy and creativity of AI image generation, impacting various research areas such as computer vision, natural language processing, and creative AI.

Visual Insights#

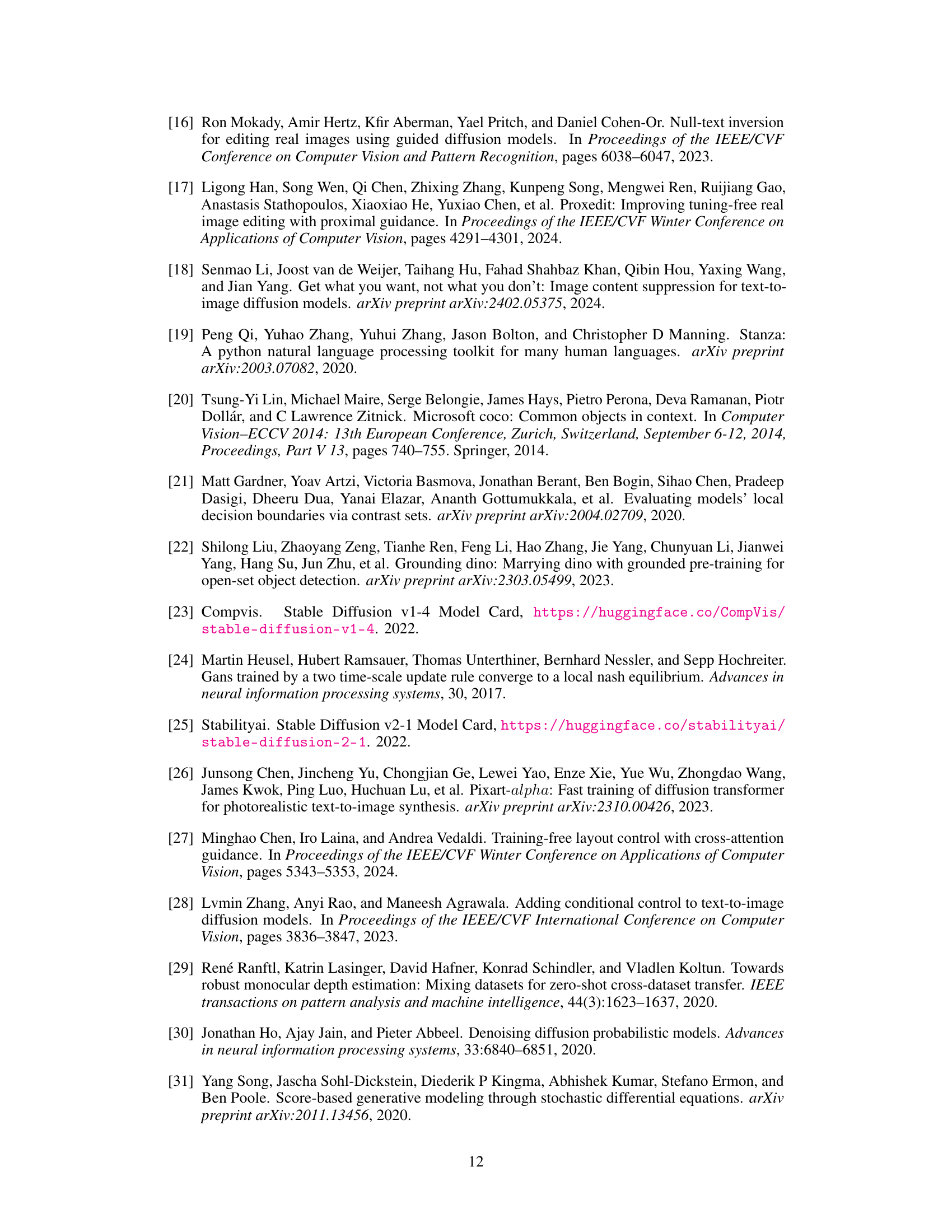

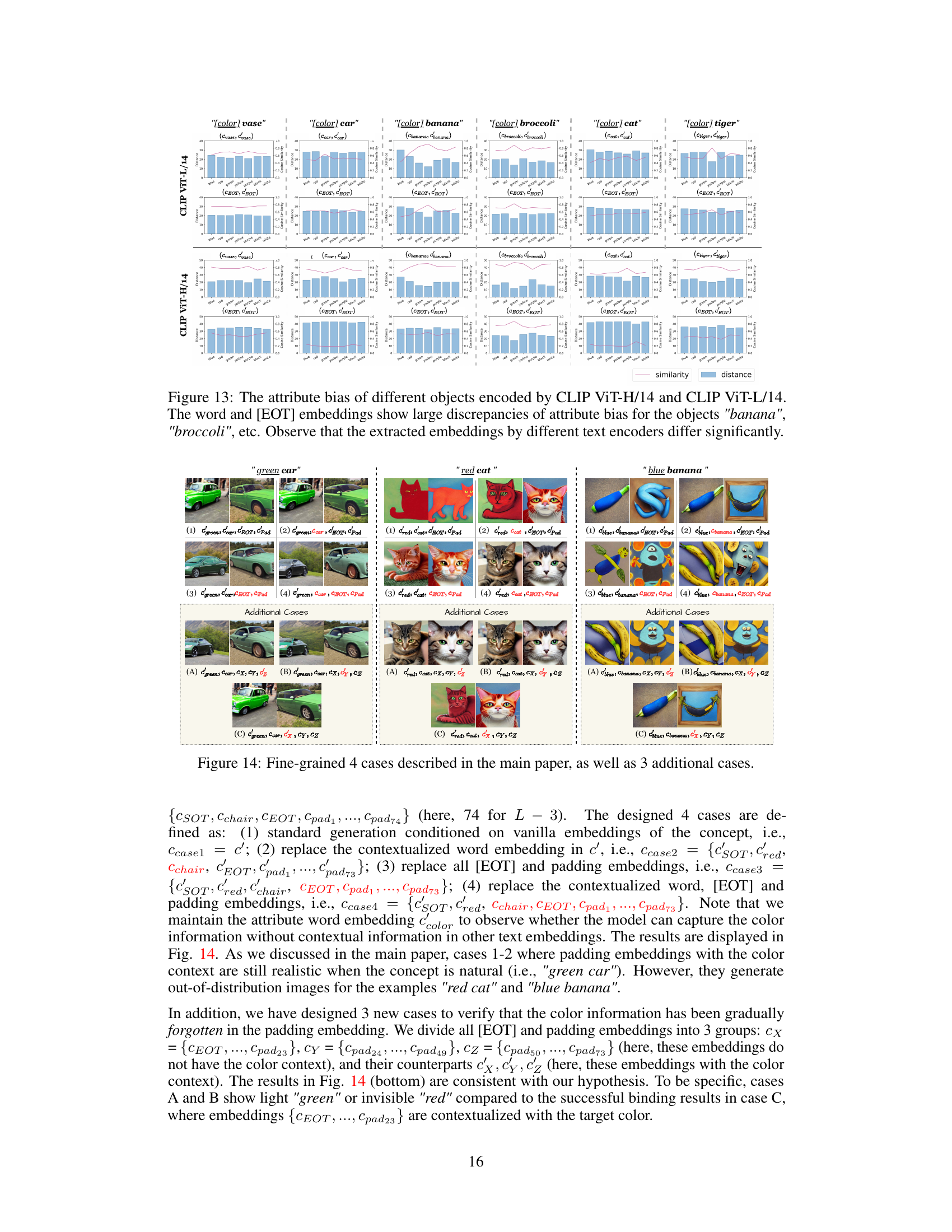

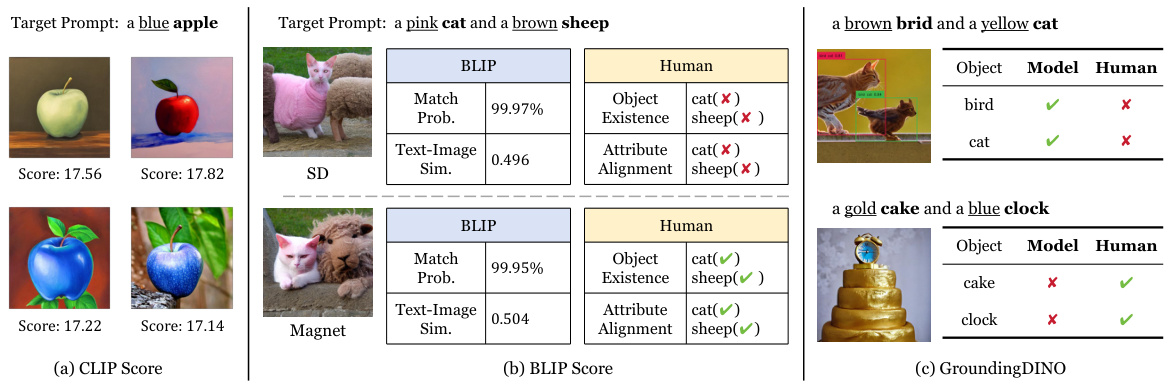

This figure analyzes how the CLIP text encoder understands attributes and how this understanding impacts diffusion models. It shows a comparison of word embeddings and end-of-text ([EOT]) embeddings for various objects with different color attributes. The discrepancy between word and [EOT] embeddings highlights a contextual issue that affects attribute binding in the text space, influencing the quality of image generation by diffusion models.

This table presents a coarse-grained comparison of the proposed Magnet method against three baseline methods (Attend-and-Excite, Structure Diffusion, and Stable Diffusion) using two datasets, ABC-6K and CC-500. The evaluation metrics are image quality, object disentanglement, and attribute disentanglement. The values are normalized percentages, summing to 100 for each dataset. It shows the relative performance of each method on different aspects of image generation quality.

In-depth insights#

CLIP Encoder Limits#

The limitations of CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training) encoders in text-to-image generation are a significant area of research. CLIP’s reliance on a blended text embedding approach often leads to issues such as improper attribute binding, where the model fails to correctly associate attributes with objects. This is particularly problematic when complex prompts are given, involving multiple objects and attributes, resulting in images that do not faithfully represent the user’s intent. The issue stems from CLIP’s inherent architecture and training, which focus on overall semantic similarity but may fail to fully capture the nuanced relationships between individual concepts and their attributes. This results in contextual issues and entanglement of concepts. Further research is needed to improve CLIP’s compositional understanding and address these limitations to improve text-to-image synthesis quality.

Magnet: Binding Fix#

The hypothetical heading “Magnet: Binding Fix” suggests a method focused on resolving the attribute binding issue in text-to-image diffusion models. Magnet likely introduces a novel approach to improve the generation of images accurately reflecting complex prompts containing multiple attributes and objects. This likely involves manipulating the text embeddings to better disentangle and bind the attributes to their correct objects. The method’s name implies a mechanism that attracts desired attributes while repelling undesired ones, much like a magnet. The “Binding Fix” portion emphasizes a direct solution to the problem of incorrect attribute pairings, indicating a high level of efficacy. The core innovation likely lies in its training-free nature, offering a computationally efficient solution that does not require additional datasets or model fine-tuning. Overall, “Magnet: Binding Fix” promises a significant advancement, tackling a major hurdle in creating more precise and nuanced text-to-image generation.

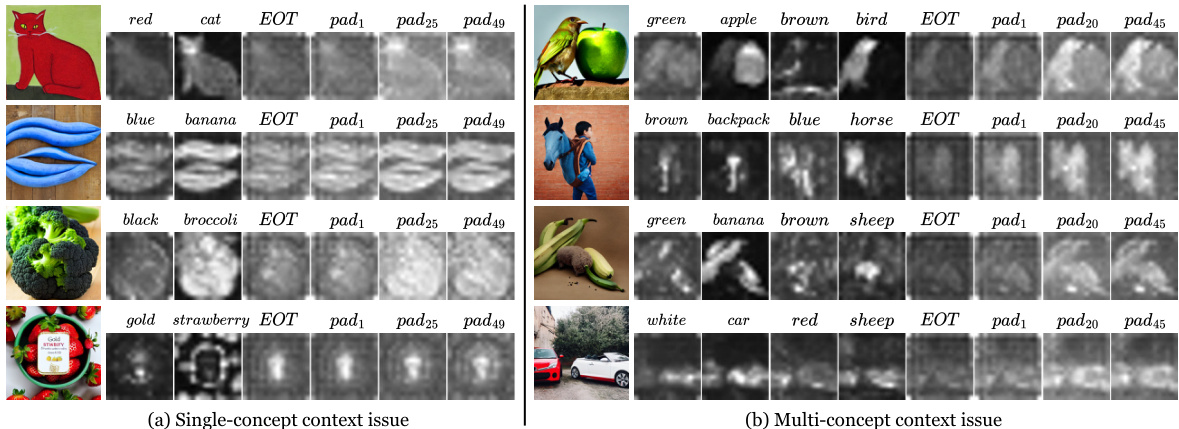

Padding Issue#

The concept of “Padding Issue” in text-to-image diffusion models centers on the problem of how padding tokens, added to ensure fixed-length input sequences, affect the model’s understanding of the prompt. Improper padding can lead to entanglement of different concepts, causing semantic confusion and impacting the model’s ability to faithfully generate the intended image. This issue is especially prominent when dealing with complex prompts involving multiple objects and attributes; the padding might inappropriately blend distinct object features together. Research suggests that the padding’s contextual influence is a crucial factor in attribute binding problems; the way padding tokens interact with other words in the prompt significantly affects how attributes are associated with their corresponding objects. Strategies to mitigate this problem include the careful engineering of padding methods, improved textual embedding techniques, or the incorporation of modules that explicitly disentangle concepts within the text representation before feeding it into the diffusion model. Understanding the padding issue is fundamental to improving the quality and coherence of text-to-image generation, as addressing this limitation is key to enabling the generation of more realistic and complex images from intricate textual descriptions. The effective resolution of this issue requires a deeper investigation into the contextual dynamics within language models and their effect on the downstream generation process.

Neighbor Strategy#

The ‘Neighbor Strategy’ employed in the Magnet model addresses a crucial limitation in estimating binding vectors for enhancing attribute disentanglement in text-to-image diffusion models. A single object’s embedding might not accurately capture the nuances of attribute relationships, particularly for unusual or unconventional concepts. The strategy leverages neighboring objects in the learned textual space that possess similar semantic representations to the target object. This approach ensures a more robust and accurate estimation of the binding vector by incorporating information from semantically related entities. By considering multiple perspectives, the neighbor strategy effectively mitigates the inaccuracies that might arise from relying solely on the target object’s embedding, resulting in improved synthesis quality and binding accuracy. The choice of neighbors (e.g., using cosine similarity) and the number of neighbors considered (K) are hyperparameters that impact the efficacy of the strategy. The inherent assumption is that semantically similar objects will share informative patterns in their embeddings. This strategy elegantly addresses a key challenge in manipulating textual embeddings without requiring further training or data, making it a computationally efficient enhancement to the overall method. However, it is important to consider the potential for bias in the selection of neighbors. The method’s effectiveness depends on the quality and representativeness of the initial textual embedding space.

Future Work#

The paper’s lack of a dedicated ‘Future Work’ section is notable. However, several avenues for future research are implicitly suggested. Extending Magnet’s capabilities to handle more complex prompts and diverse object interactions is crucial. Investigating the impact of different text encoders and their contextual understanding on Magnet’s performance would provide deeper insight into the model’s limitations and potential improvements. A more rigorous exploration of the hyperparameters and their effect on the balance between image quality and attribute binding is warranted. Finally, exploring Magnet’s integration with other image editing or generation techniques and examining its performance on video or 3D data are promising directions. A dedicated section outlining these future directions would strengthen the paper and provide clear guidance for future research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

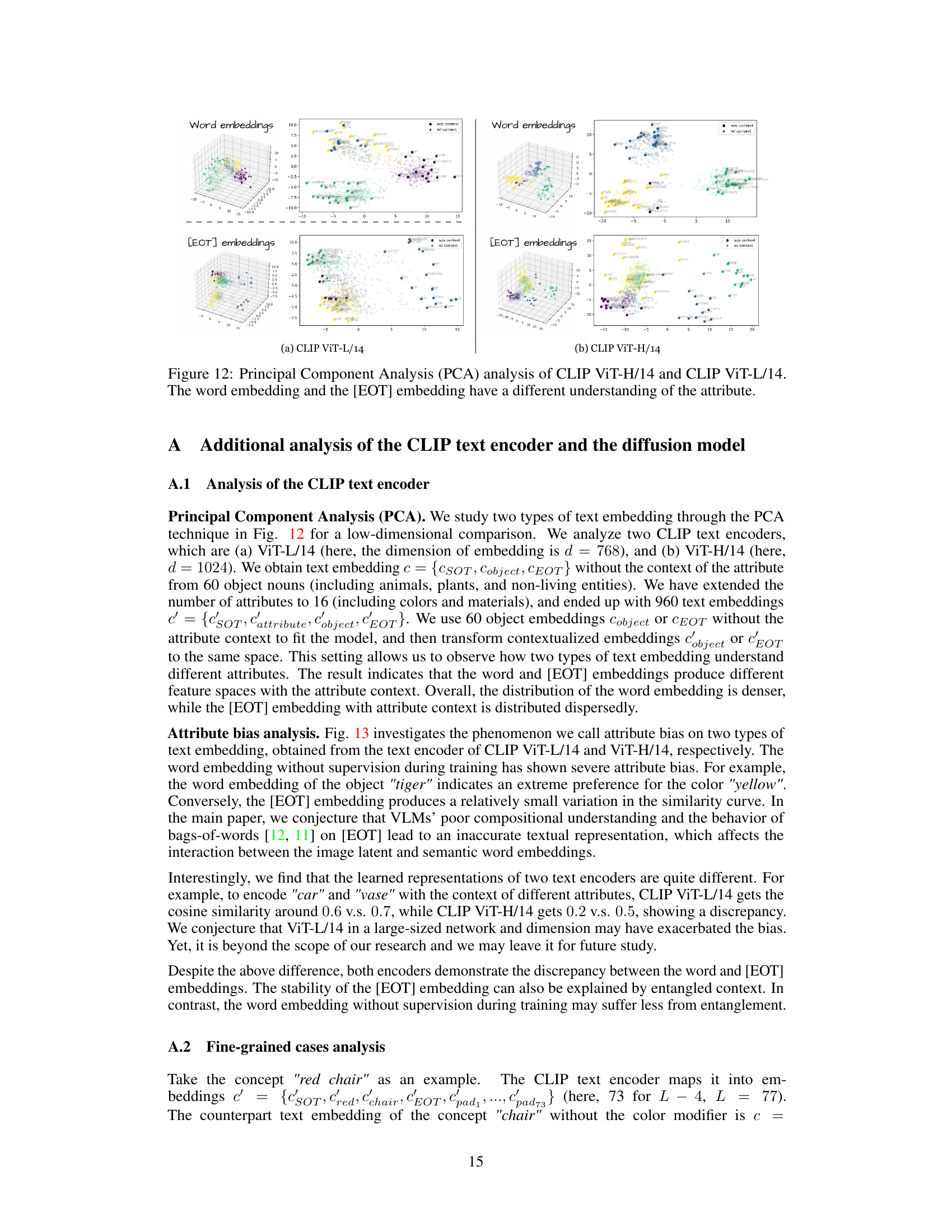

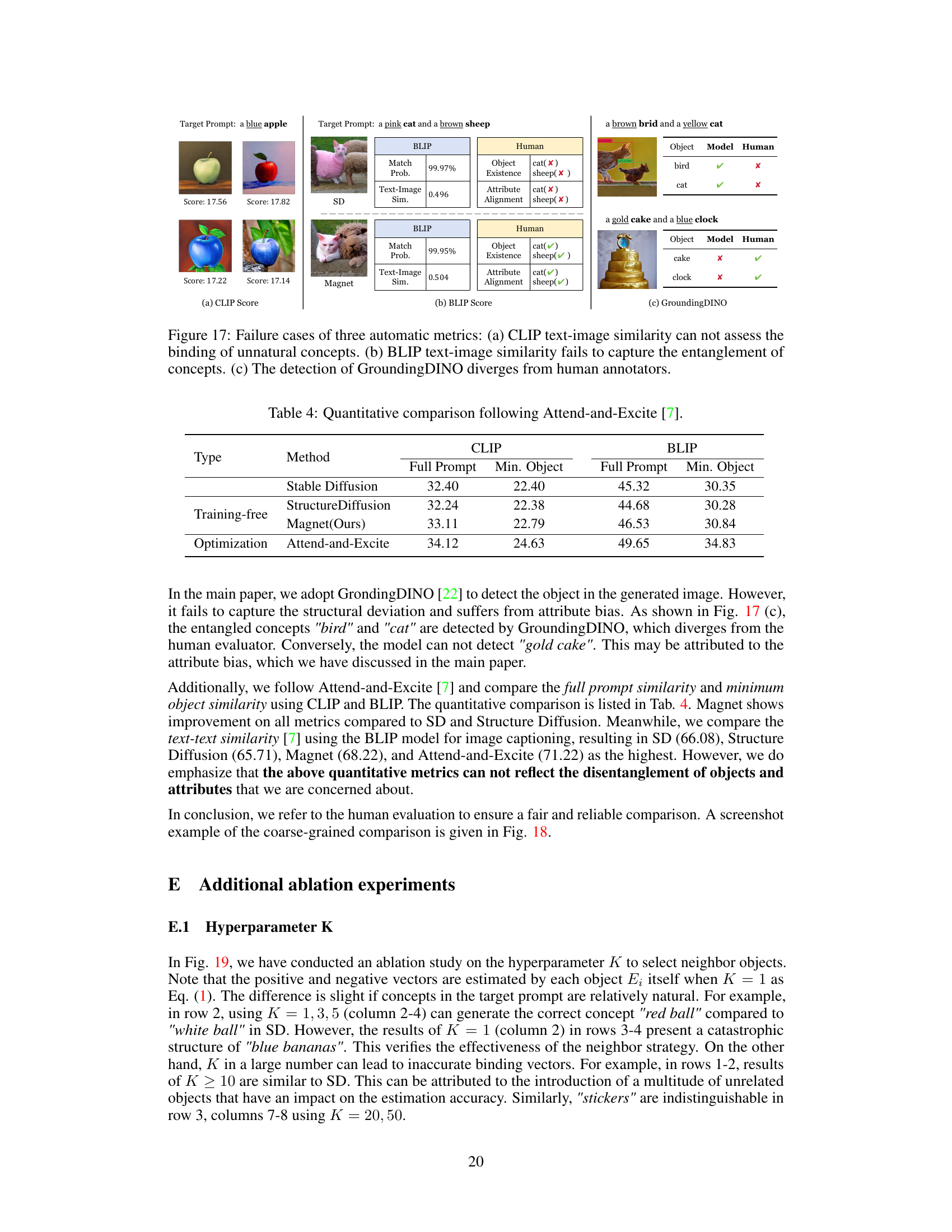

This figure presents a fine-grained analysis of the impact of embedding manipulation on text-to-image generation. (a) shows three example prompts (‘red chair’, ‘black sheep’, ‘blue apple’) with four variations each, demonstrating how changing the contextualized word embedding, [EOT] embedding, and padding embeddings affects the generated images. (b) and (c) visualize the cosine similarity between [EOT] and padding tokens for single-concept and multi-concept prompts, respectively, illustrating the context issue in padding embeddings where the padding tokens forget the context or entangle different concepts. This highlights the contextual problem in padding embeddings, which is crucial for understanding the attribute binding problem.

This figure illustrates the Magnet framework’s architecture. It shows how the framework works, starting from receiving a prompt (P) to generating an image using Stable Diffusion (SD). The framework involves manipulating the object embeddings by adding positive and negative binding vectors to each object in the prompt. These vectors are generated using both the object’s own information and information from its neighboring objects to increase the accuracy of the binding process. Adaptive strength parameters αi and βi are introduced to balance the influence of the positive and negative vectors, making the binding strength dynamic and context-aware. The framework operates entirely in the text space, requiring no additional datasets or training.

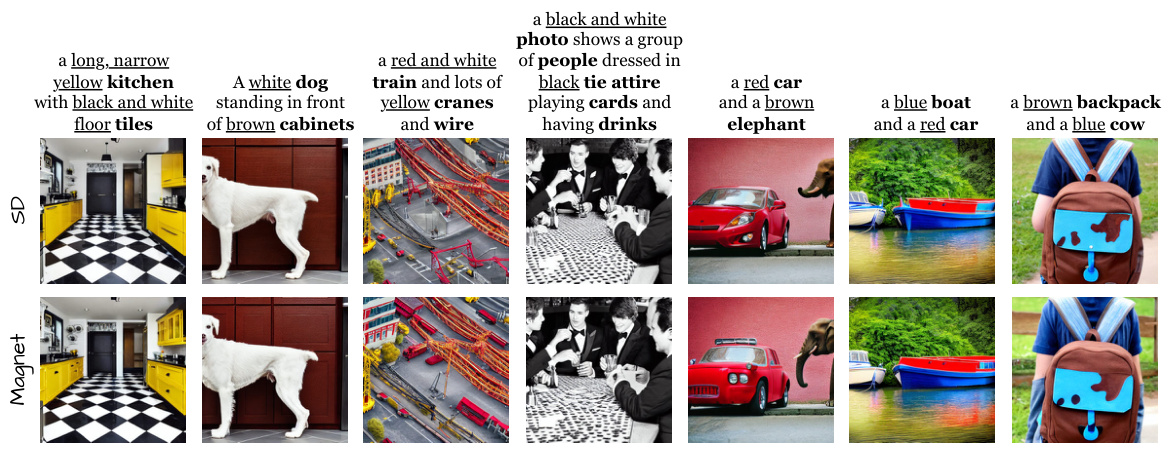

This figure displays a qualitative comparison of the results produced by four different methods (Stable Diffusion, Structure Diffusion, Attend-and-Excite, and Magnet) on various prompts from two datasets (ABC-6K and CC-500). Each row represents a different prompt, and each column represents a different method. The images show the models’ ability to generate images that correctly reflect the attributes and objects specified in the prompt. The figure highlights the differences in the image quality and the accuracy of attribute binding across the different models.

This figure shows the results of generating images from prompts containing unnatural concepts (e.g., blue banana, black sheep). It compares the outputs of Stable Diffusion, Attend-and-Excite, and the proposed Magnet method. The baselines struggle to generate realistic images, often mixing up colors or producing unrealistic artifacts. In contrast, Magnet successfully generates high-quality images that accurately reflect the unnatural concepts in the prompts, demonstrating its ability to overcome biases learned during training.

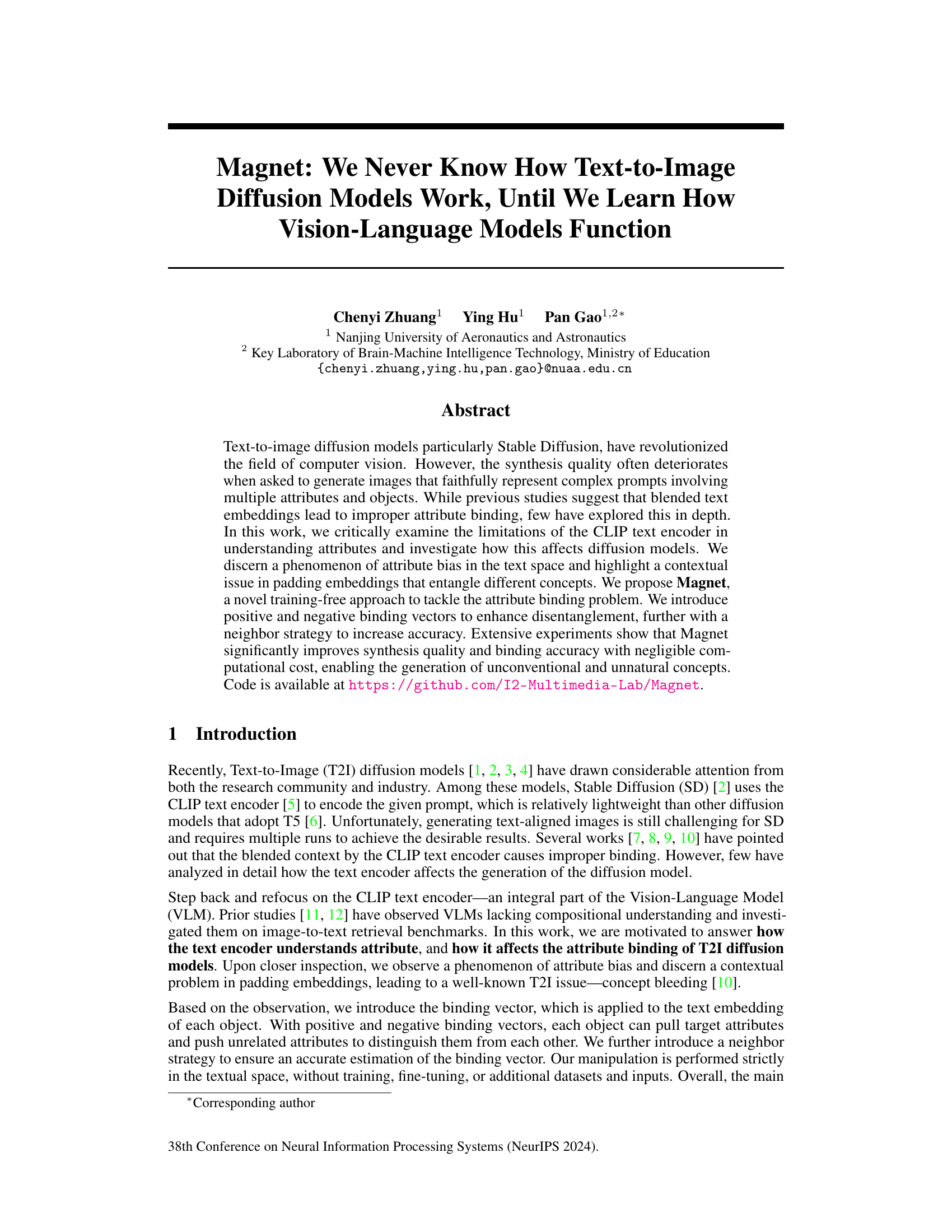

This ablation study demonstrates the effect of the hyperparameter λ on the ability of the Magnet method to disentangle different concepts within a generated image. Using the prompt ‘a pink cake with white roses on silver plate’, the figure shows the results for three different values of λ: 0.0, 1.0, and 0.6 (the value used in the paper). The images show that a low value of λ (0.0) fails to adequately separate the concepts, while a high value (1.0) introduces artifacts. The intermediate value of λ (0.6) provides the best balance between concept separation and image quality.

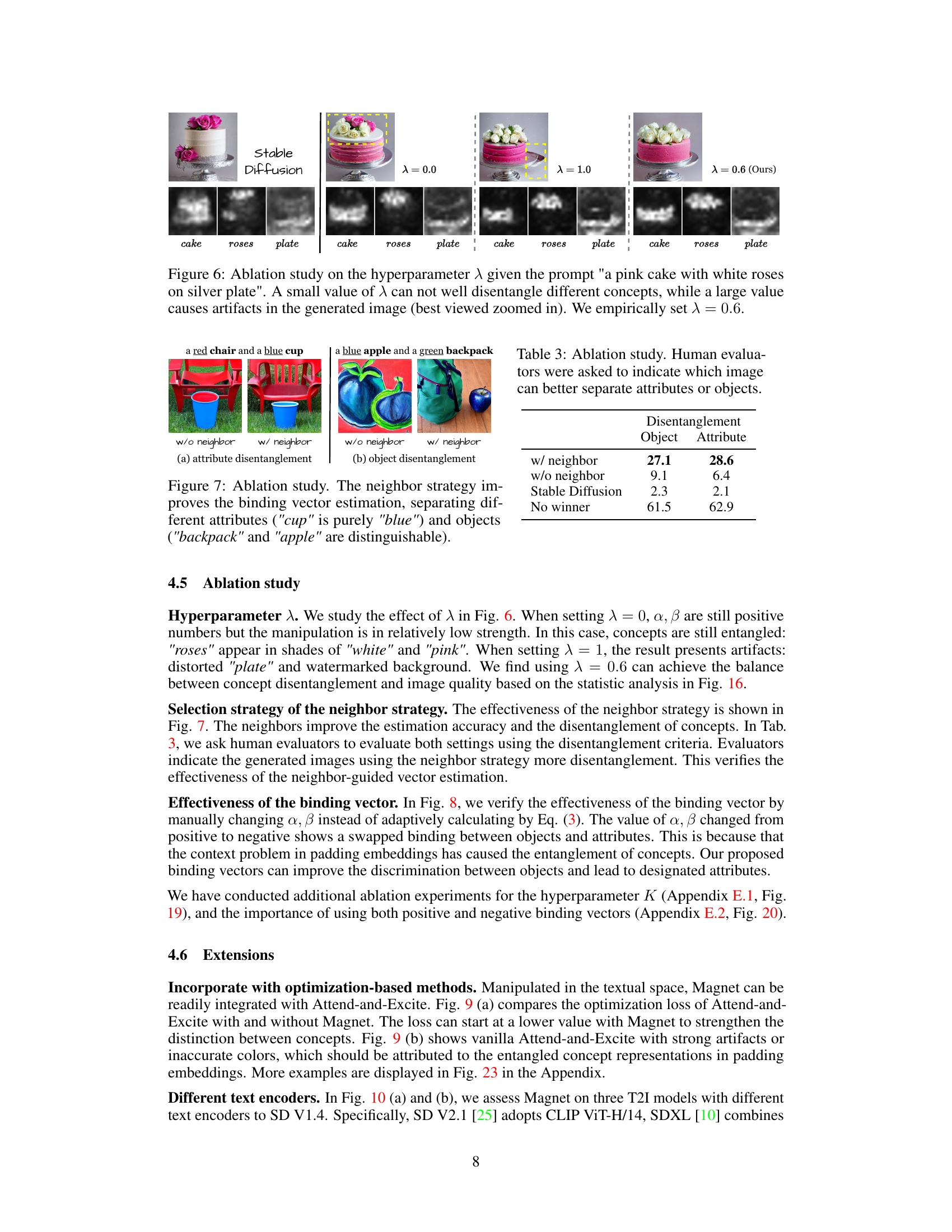

This figure shows an ablation study comparing the results of using a single object versus multiple neighbor objects to estimate the binding vector in the Magnet model. The results demonstrate that incorporating neighbor objects significantly improves the accuracy of the binding vector, leading to better separation of attributes and objects in the generated images. The left panel shows that when only using a single object to estimate the binding vector, the attribute ‘blue’ is not well-associated with the ‘cup’, whereas with neighbors, the ‘blue’ attribute is correctly bound to the ‘cup’. Similarly, on the right panel, with a single object, the generated image contains a ‘blue’ apple and a green backpack. When using neighbors, the objects are properly separated.

This figure shows the results of an ablation study comparing the performance of the proposed Magnet method with and without the neighbor strategy. The neighbor strategy enhances the accuracy of binding vector estimation, leading to better separation of attributes and objects in image generation. The improvements are demonstrated using examples of image generation where attributes and objects are correctly bound when using the neighbor strategy but mis-bound otherwise. This highlights the importance of the neighbor strategy for accurate and effective attribute and object binding.

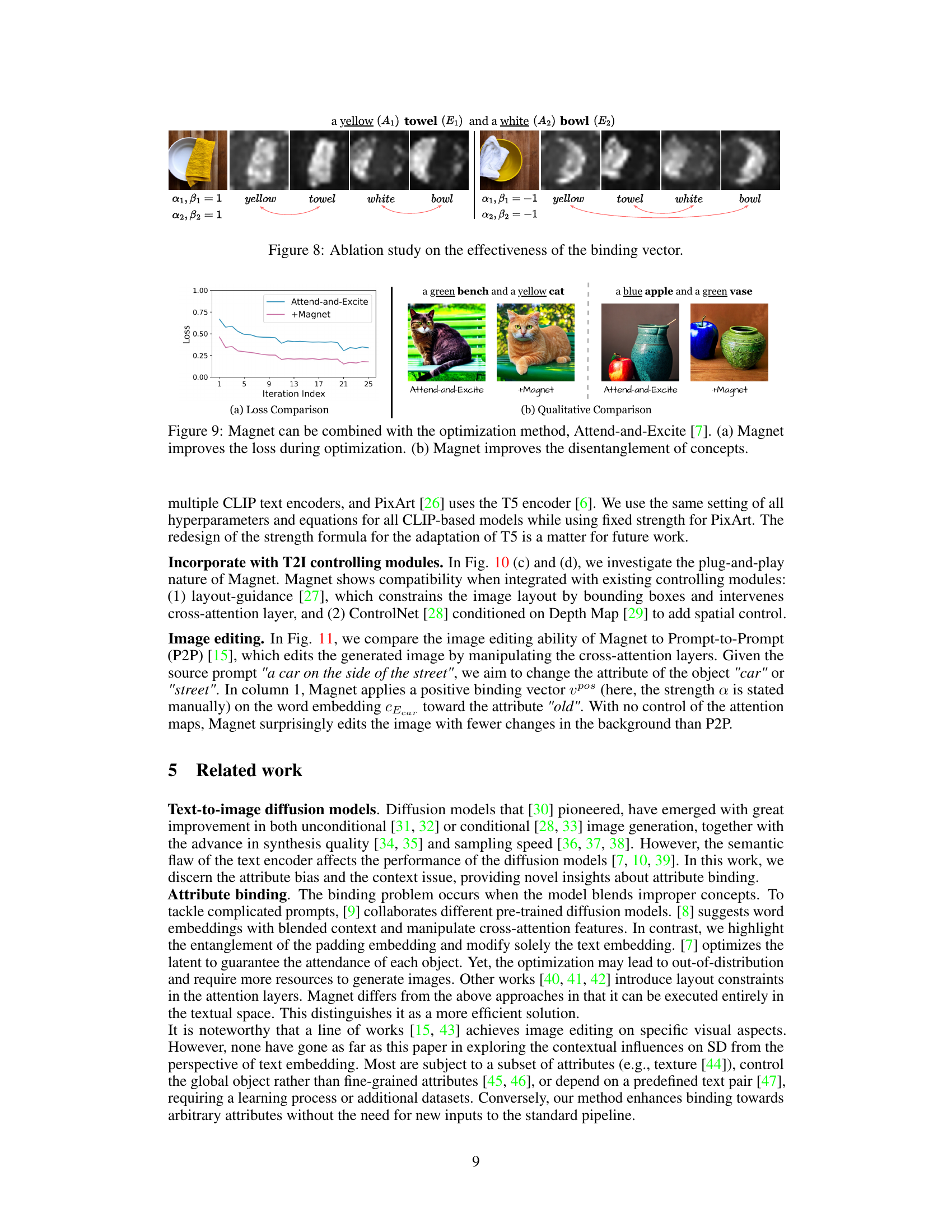

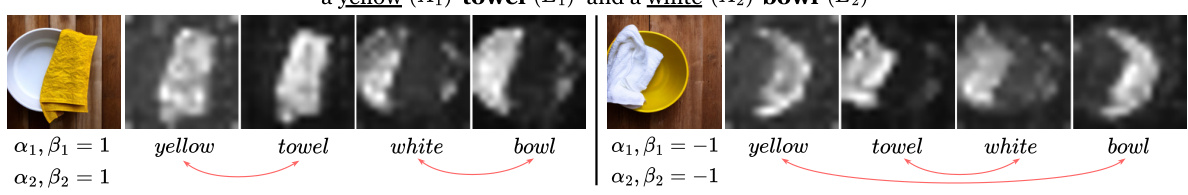

This figure shows an ablation study on the effectiveness of the binding vector. It presents images generated with different combinations of positive and negative binding vectors (α₁, β₁ and α₂, β₂). Specifically, it showcases results where both α₁ and α₂ are set to 1 (positive binding) and where both are set to -1 (negative binding). The images demonstrate how the binding vector influences the generation of objects and their attributes within the context of a prompt.

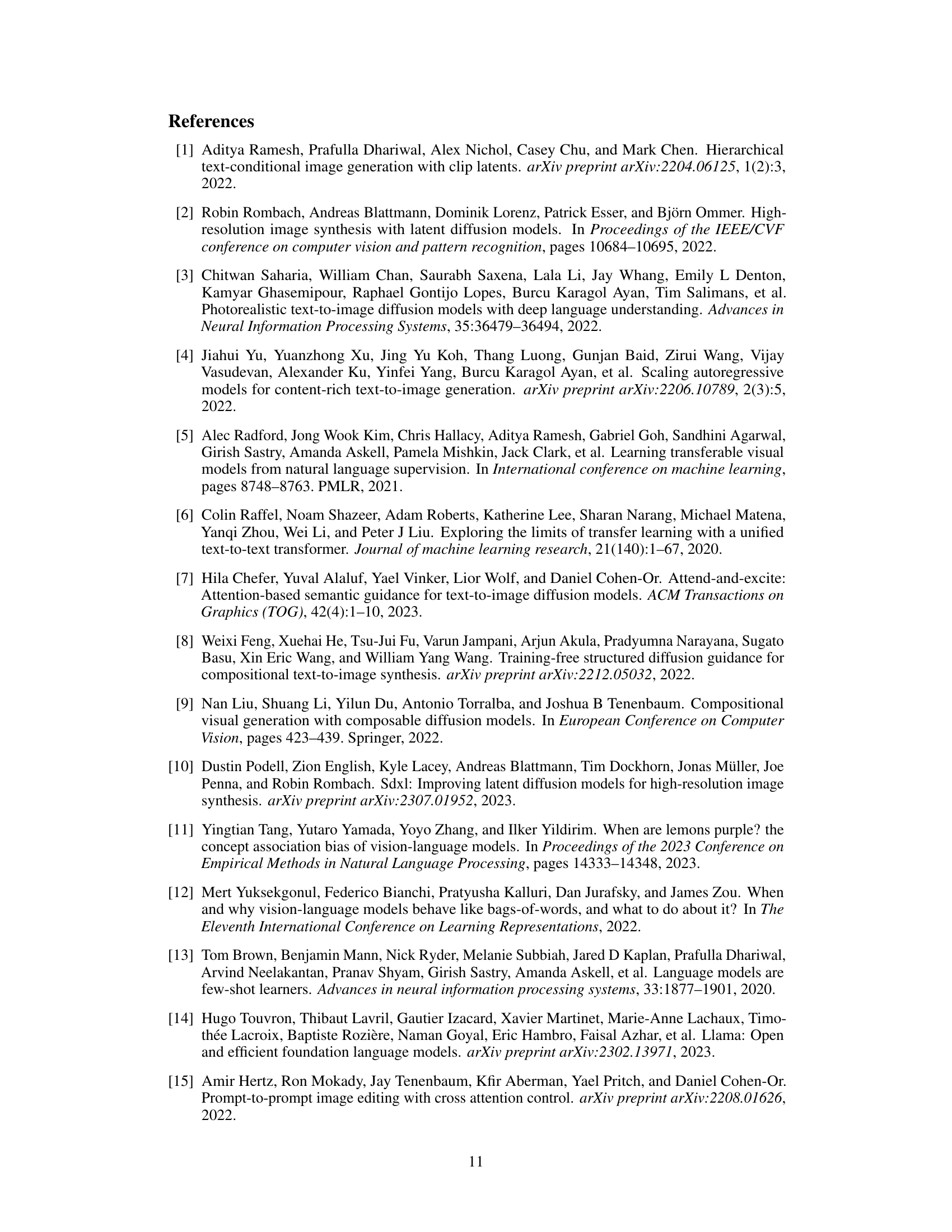

This figure shows the results of combining Magnet with the optimization method Attend-and-Excite. The left panel (a) is a graph showing that adding Magnet to Attend-and-Excite reduces the optimization loss. The right panel (b) shows a qualitative comparison of images generated by Attend-and-Excite alone and with Magnet added. The images demonstrate that Magnet improves the disentanglement of concepts, leading to more realistic and visually appealing results.

This figure shows that the proposed Magnet method can be integrated with other text-to-image (T2I) models and existing controlling modules such as layout-guidance and ControlNet. The results demonstrate the versatility and compatibility of Magnet, showing that it can improve image generation across different model architectures and control schemes.

This figure shows a comparison of image editing results between the Prompt-to-Prompt method and the Magnet method proposed in the paper. The source prompt is ‘a car on the side of the street.’ Different prompts are generated by modifying the initial prompt to change the type of car (‘old car,’ ‘crushed car,’ ‘sport car’) and the street conditions (‘flooded street,’ ‘forest street,’ ‘snowy street’). The top row shows the edits from the Prompt-to-Prompt method, while the bottom row displays the edits from the Magnet method. The comparison highlights the differences in image generation and editing capabilities of the two methods.

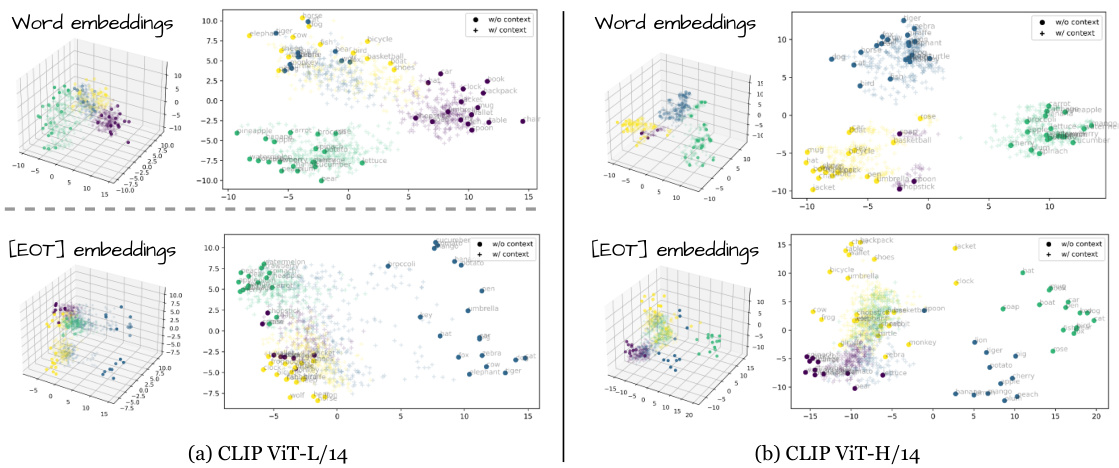

This figure presents the results of a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) applied to word embeddings and End-of-Text ([EOT]) embeddings from two different CLIP text encoders (ViT-L/14 and ViT-H/14). The PCA reduces the dimensionality of the embeddings to visualize them in 3D space. The plots show that word embeddings and [EOT] embeddings differ significantly in their representation of attributes, indicating that the two types of embeddings capture different aspects of the input text and its semantic meaning. This difference highlights a key aspect of the text encoder limitations and informs the design of Magnet.

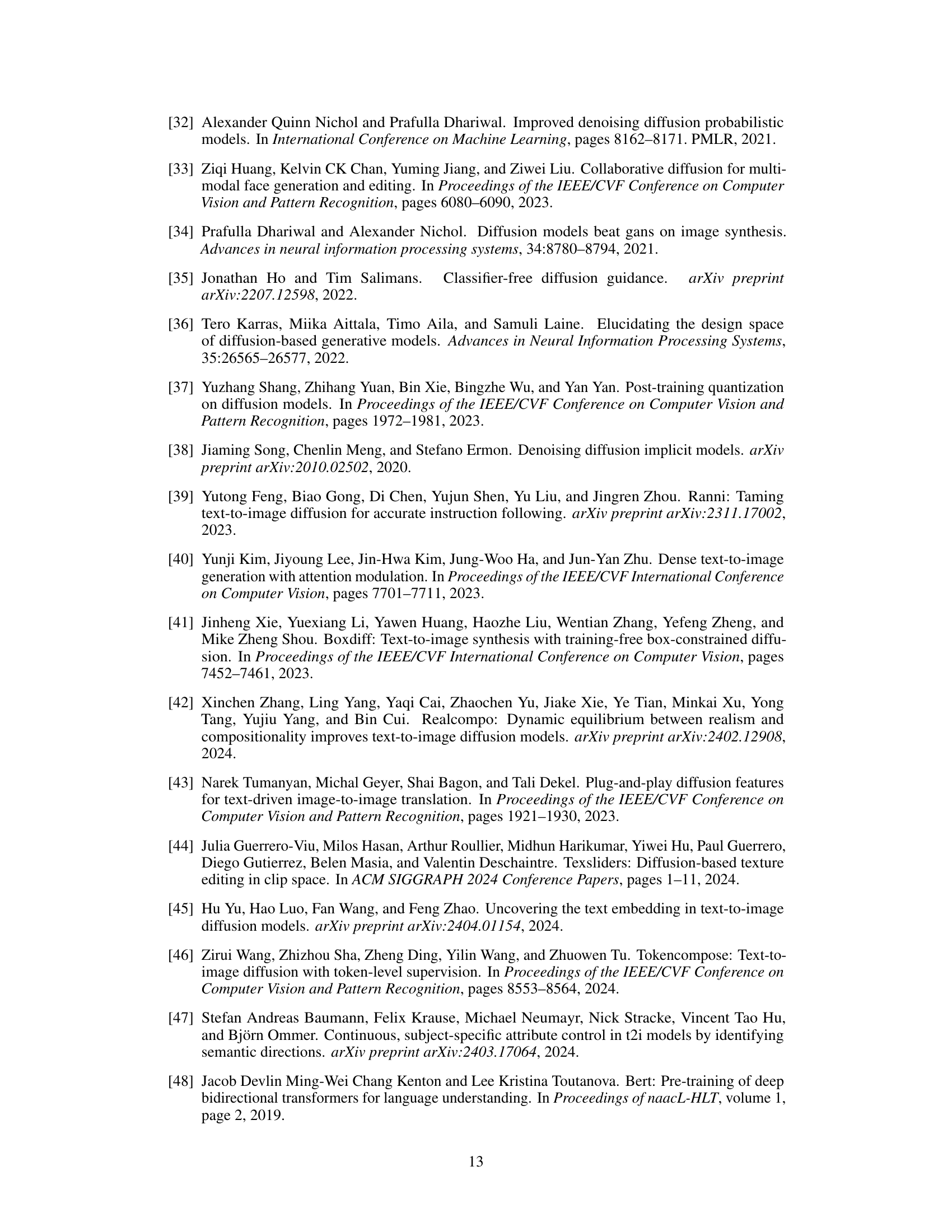

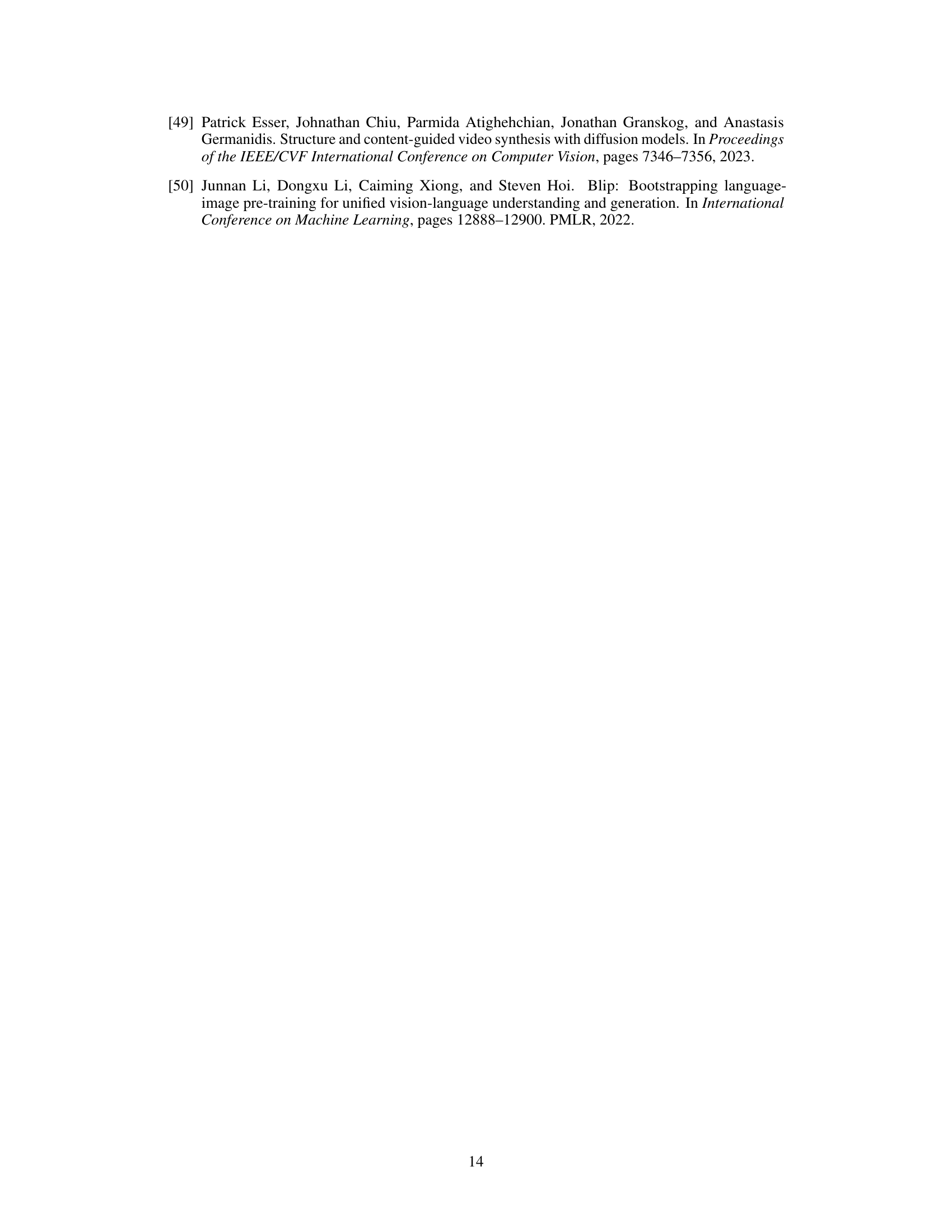

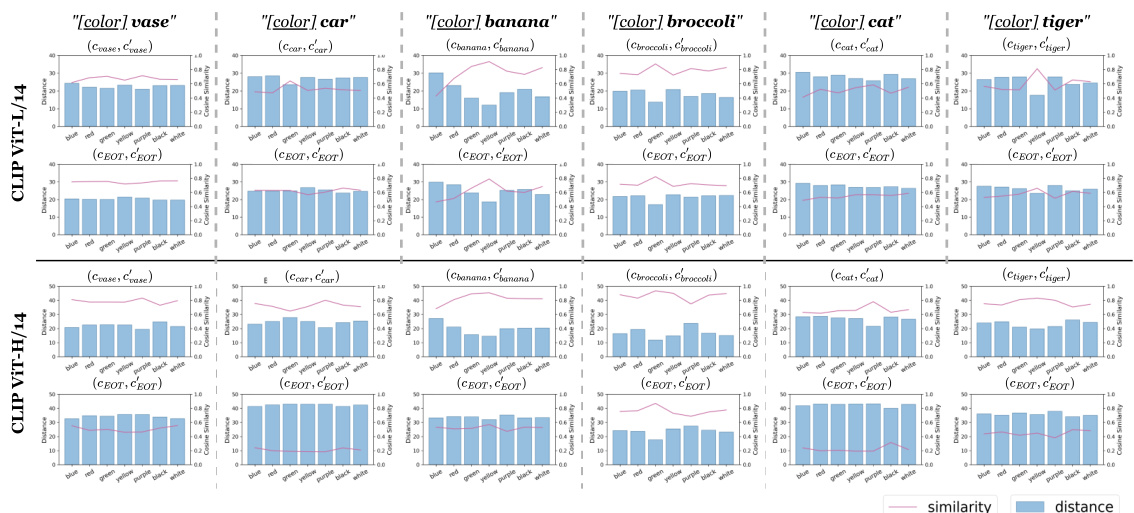

This figure analyzes how CLIP’s text encoder handles attributes, comparing embeddings with and without color context for various objects. It reveals inconsistencies between word embeddings and end-of-text ([EOT]) embeddings, highlighting a phenomenon called ‘attribute bias.’ This bias impacts how diffusion models understand and bind attributes, especially in complex prompts. The graphs showcase cosine similarity and Euclidean distance between embeddings under various conditions.

This figure analyzes how CLIP’s text encoder handles attributes, revealing inconsistencies in how word embeddings and end-of-text ([EOT]) embeddings represent attribute bias across different objects. The visualizations show that there is not a consistent pattern in how the encoder handles attribute understanding, highlighting a potential problem with how attributes are encoded which can impact downstream diffusion models.

This figure visualizes how the context issue in padding embeddings affects the generation process in single-concept and multi-concept scenarios. In single-concept scenarios, it shows that inaccurate object representations or the generation of natural concepts instead of the target unnatural concepts can occur. In multi-concept scenarios, this issue results in color leakage, objects sticking together, and even missing objects. This highlights the impact of entangled contextual information in the padding embeddings, which leads to various image generation problems.

This histogram shows the distribution of the cosine similarity (ω) between the first [EOT] embedding and the last padding embedding of the positive concept (Ppos) across 19648 samples. The x-axis represents the cosine similarity values, and the y-axis represents the count of samples with that similarity. The peak of the distribution is around ω = 0.7, indicating a strong correlation between the two embeddings for most samples. The value ω = 0.6 is chosen as the hyperparameter λ for the adaptive strength of binding vectors because it’s where the count begins to significantly drop, suggesting that values below this threshold represent weaker correlations and therefore weaker binding.

This figure analyzes how the CLIP text encoder understands attributes and how that impacts diffusion models. It shows a discrepancy between word embeddings and [EOT] (End of Text) embeddings in terms of attribute bias across various objects. The visualization highlights how the way the CLIP encoder processes text affects the quality of image generation in diffusion models. Different color prompts were given for different objects and the resulting CLIP vector similarities and norms are plotted.

The figure analyzes how the CLIP text encoder understands attributes, focusing on the difference between word embeddings and end-of-text ([EOT]) embeddings. It reveals a discrepancy in how these two types of embeddings represent attribute bias across different objects. This discrepancy impacts the quality of image generation in diffusion models.

This figure shows an ablation study on the hyperparameter K used in the Magnet model. The study evaluates the effect of varying the number of neighbor objects considered when estimating the binding vector. The results indicate that using K=5 offers a good balance between generating high-quality, disentangled images and computational efficiency. While other values of K might produce better results in certain instances due to the stochastic nature of the latent diffusion process, K=5 provides a more consistent performance across different scenarios and prevents excessive processing times.

This figure shows an ablation study on the impact of using positive and negative binding vectors in the Magnet method. It presents three examples with varying combinations of the vectors and compares the generated images to those produced by Stable Diffusion. The results demonstrate that using both positive and negative binding vectors significantly improves the quality and accuracy of attribute binding in generated images, helping to resolve issues like missing objects and enhance the clarity of attributes.

This figure demonstrates several limitations of the Magnet method. It shows examples where Magnet fails to generate all the objects requested (neglect of object), generates images that are unrealistic or outside the expected distribution (over-manipulation and out-of-distribution), has issues with the spatial arrangement of objects relative to each other (wrong positional relation), and still struggles with the entanglement of concepts that are too closely related (concept entanglement). It also highlights how Magnet’s ability to generate images with unusual concepts (e.g., bananas with bears inside) is limited by the model’s inherent biases (strong attribute bias).

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of image generation results using prompts from the ABC-6K dataset, which focuses on natural compositional prompts. The comparison includes Stable Diffusion, Structure Diffusion, Attend-and-Excite, and the proposed Magnet method. Each method’s output is shown for several indoor scene prompts. The goal is to highlight the differences in image quality and the accuracy of object and attribute representation across the different methods. The images are best viewed at a larger zoom level for finer detail.

This figure shows the results of combining Magnet with the optimization method Attend-and-Excite. The top row shows examples generated by Stable Diffusion (SD), while subsequent rows display results from using Magnet alone, Attend-and-Excite alone, and the combination of both. The results demonstrate the impact of each method on generating images with various prompts that feature natural and unnatural concepts. The last column illustrates a failure case where the combination of methods still fails to generate a satisfactory image. This highlights the need for parameter adjustments to optimize the Magnet method.

This figure showcases a qualitative comparison of image generation results between Stable Diffusion and the proposed Magnet method for several prompts. Each row represents a different prompt, and the left column shows the outputs generated by Stable Diffusion while the right displays results from the Magnet approach. The images demonstrate Magnet’s ability to produce higher-quality and more faithful renderings to the prompt by effectively disentangling and separating different concepts within the image. For example, in some of the images, Stable Diffusion outputs images where elements seem to merge or blend together in a way that doesn’t accurately reflect the prompt’s specifications. The zoomed-in view is recommended for better appreciation of the details.

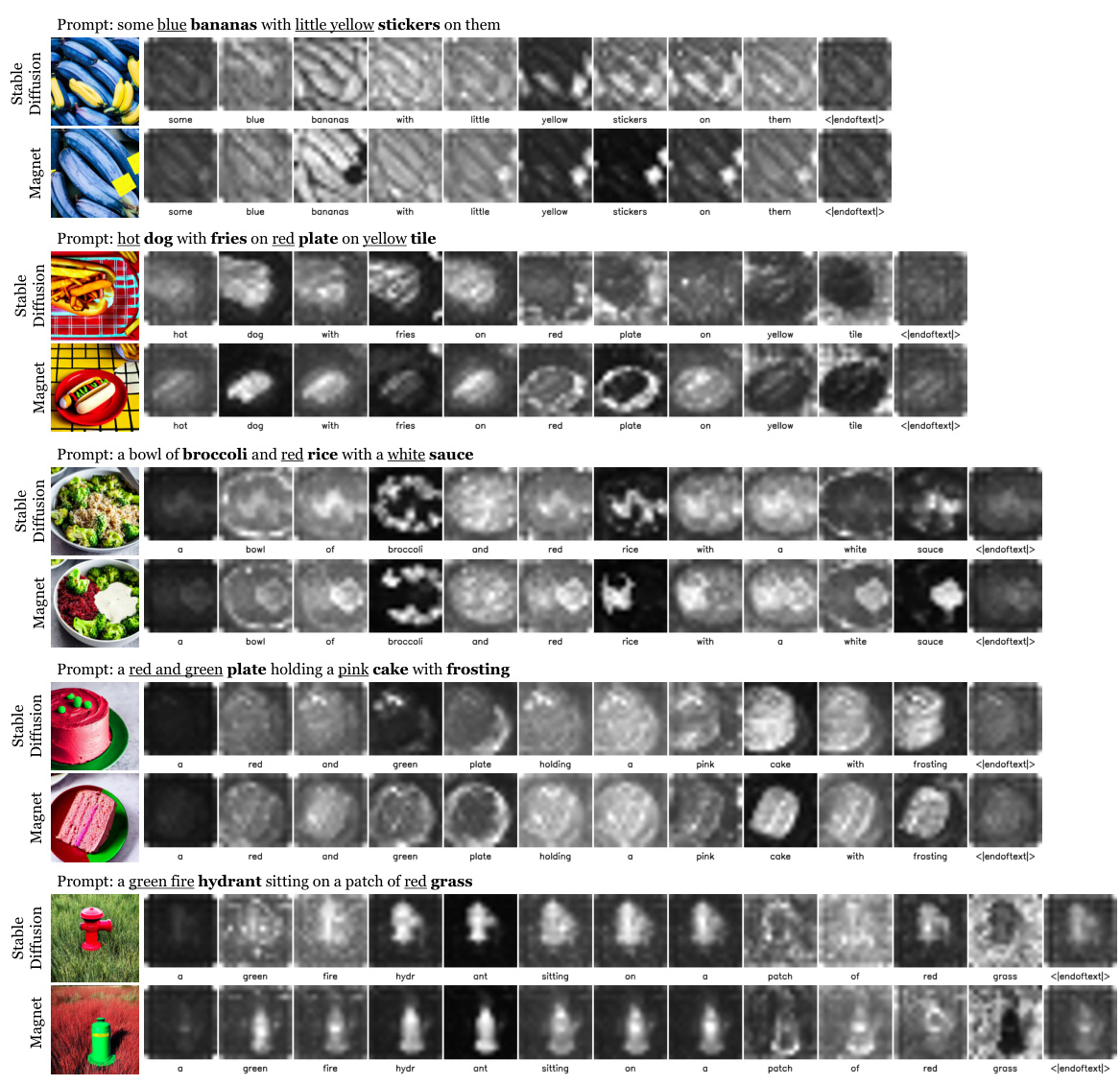

This figure visualizes the attention maps from Stable Diffusion and Magnet for five different prompts. Each row shows the attention maps for a single prompt, comparing the results from Stable Diffusion and Magnet. The goal is to demonstrate that Magnet produces more distinct attention maps, separating the objects more effectively compared to Stable Diffusion, where the activations of different objects tend to be more overlapped.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of the results obtained by four different text-to-image generation methods (Magnet, Attend-and-Excite, Stable Diffusion, and Structure Diffusion) on prompts from the ABC-6K and CC-500 datasets. For each prompt, the images generated by each method using the same random seed are displayed side-by-side, allowing for a visual comparison of the synthesis quality and attribute binding accuracy of each method.

This figure displays a qualitative comparison of the results obtained by four different methods (Magnet, Attend-and-Excite, Stable Diffusion, and Structure Diffusion) when generating images from prompts in the ABC-6K and CC-500 datasets. For each prompt, the images produced by all four methods using the same random seed are shown side-by-side. This allows for a direct visual comparison of the strengths and weaknesses of each approach in terms of image quality, object and attribute binding, and overall adherence to the prompt.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of image generation results for various indoor scenes using four different methods: Stable Diffusion, Structure Diffusion, Attend-and-Excite, and the proposed Magnet. The prompts used are complex and involve multiple attributes and objects, testing the ability of each method to accurately represent these details in the generated images. The figure demonstrates that Magnet produces more realistic and accurate images compared to other methods, especially for challenging prompts with intricate details.

This figure presents a qualitative comparison of image generation results across four different methods (Stable Diffusion, Structure Diffusion, Attend-and-Excite, and Magnet) using prompts from the ABC-6K dataset. Each row represents a different prompt, focusing on complex scene descriptions involving multiple objects and attributes. The images generated by each method are displayed side-by-side, allowing for visual comparison and highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of each approach in handling intricate prompts and generating visually appealing and accurate results.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of images generated by four different methods: Stable Diffusion, Structure Diffusion, Attend-and-Excite, and Magnet (the proposed method). Each row represents a different prompt from the CC-500 dataset, which contains prompts that combine two concepts, each with a color attribute. The figure demonstrates that Magnet outperforms the baselines in terms of object and attribute disentanglement, and in generating images that faithfully represent the prompts. In particular, Magnet is able to generate more realistic and detailed images, and it is less likely to produce artifacts or to misinterpret the prompt.

More on tables

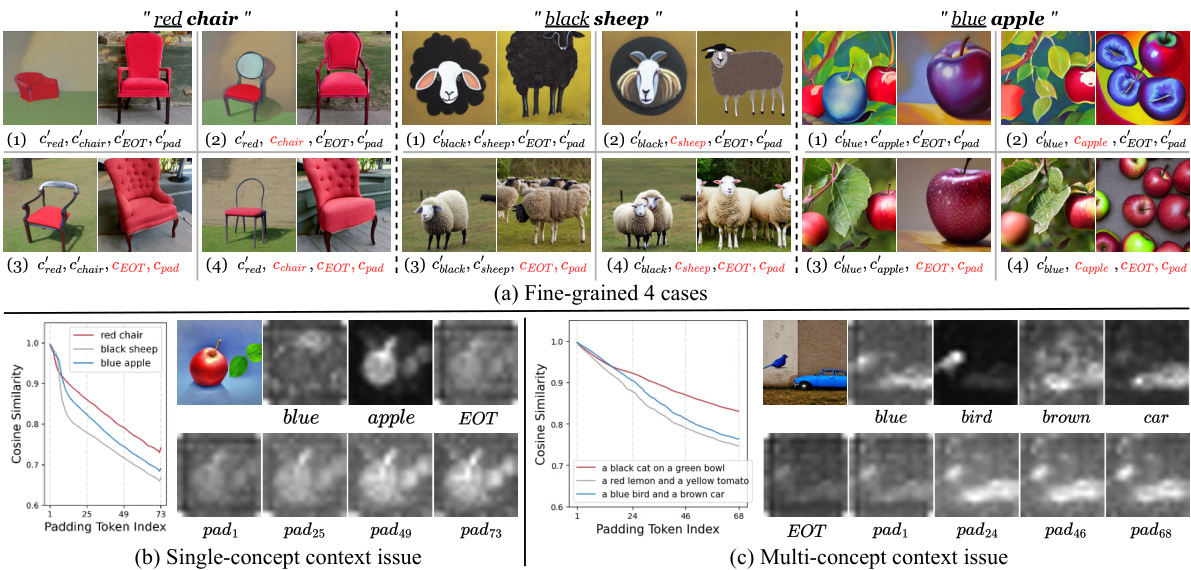

This table presents a fine-grained comparison of different methods on the CC-500 dataset. It compares automatic object detection confidence and manual evaluations of object existence and attribute alignment accuracy. The runtime and memory usage of each method are also included, showing the efficiency of Magnet.

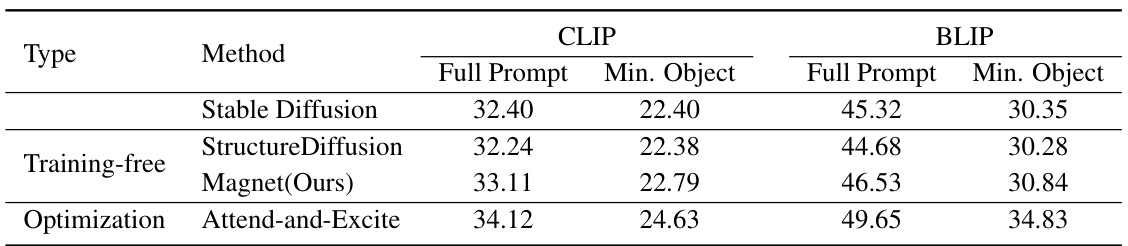

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for addressing the attribute binding problem in text-to-image generation. It compares the performance of Stable Diffusion, Structure Diffusion, Magnet (the proposed method), and Attend-and-Excite using two metrics: CLIP and BLIP scores. Both metrics evaluate the similarity between generated images and their corresponding text prompts. The ‘Full Prompt’ score considers the entire prompt, while the ‘Min. Object’ score considers only the minimum objects. The table is categorized by whether the method is training-free or optimization-based.

This table presents the results of an ablation study evaluating the impact of using positive and negative binding vectors in the Magnet model. It shows the object and attribute disentanglement scores for three scenarios: using both positive and negative vectors, using only positive vectors, and using only negative vectors. The results are compared to a baseline using Stable Diffusion, and also include the percentage of cases where no clear winner could be determined. The table aims to demonstrate the importance of using both vector types for effective disentanglement.

Full paper#