↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Modern Hopfield Models (MHMs) are promising associative memories but lack optimal capacity guarantees. Their performance hinges on memory set quality, causing suboptimal retrieval accuracy. This paper addresses the limitations of MHMs by introducing Kernelized Hopfield Models (KHMs).

KHMs address the issues through a novel framework leveraging spherical codes from information theory. The optimal memory capacity is achieved when the memories form an optimal spherical code. The authors propose U-Hop+, a sublinear time algorithm to reach this optimal capacity. This approach leads to improved retrieval capability and representation learning in transformers. The findings are further validated with empirical results.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI and memory systems. It offers a novel framework for understanding the optimal memory capacity of modern Hopfield models, filling a critical gap in the field. The sublinear time algorithm to reach optimal capacity is highly practical and applicable to various transformer-compatible models, opening new avenues for improved representation learning and efficient memory utilization.

Visual Insights#

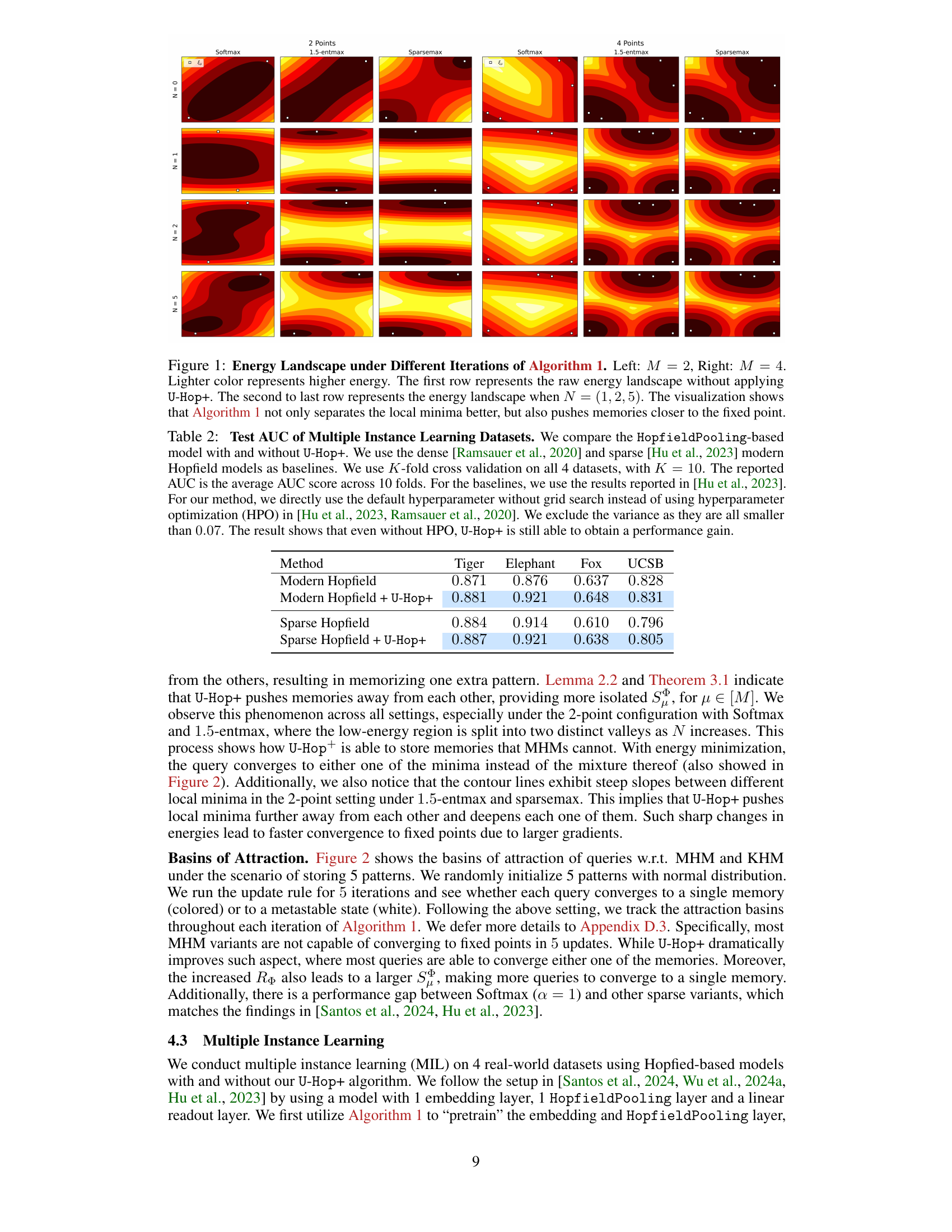

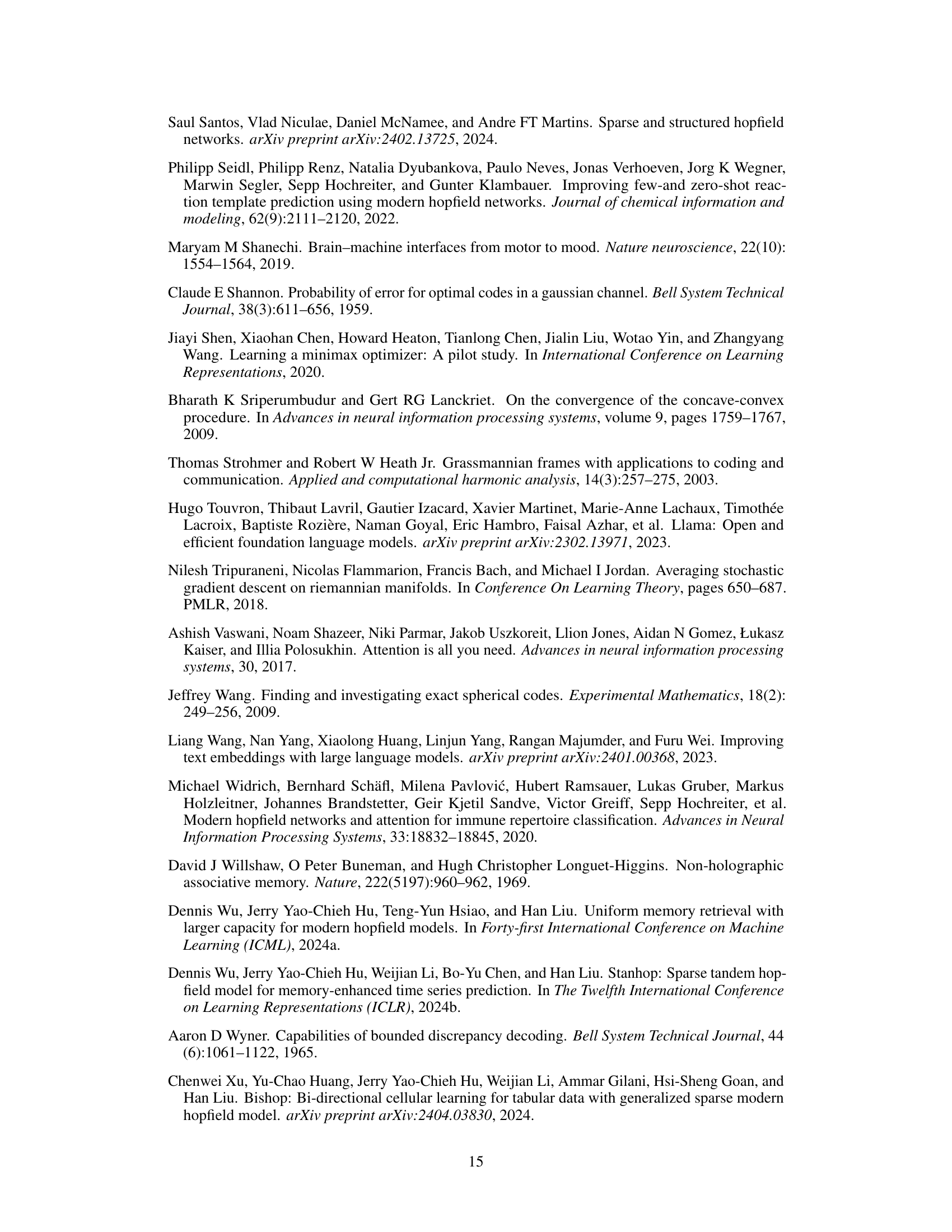

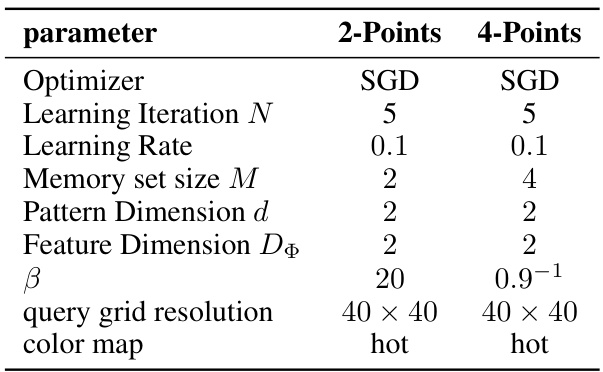

This figure visualizes the energy landscape of KHMs at different stages of Algorithm 1 for two settings: 2 and 4 memories stored in a 2-dimensional space. The raw energy landscape (without U-Hop+) is compared against the energy landscape after applying U-Hop+ for different iterations (N=1,2,5). Lighter colors represent higher energy. The visualization demonstrates how Algorithm 1 improves the separation of local minima (valleys) and pushes memories closer to fixed points, suggesting improved memory storage and retrieval capacity. The visualization shows that Algorithm 1 not only separates the local minima better, but also pushes memories closer to the fixed point.

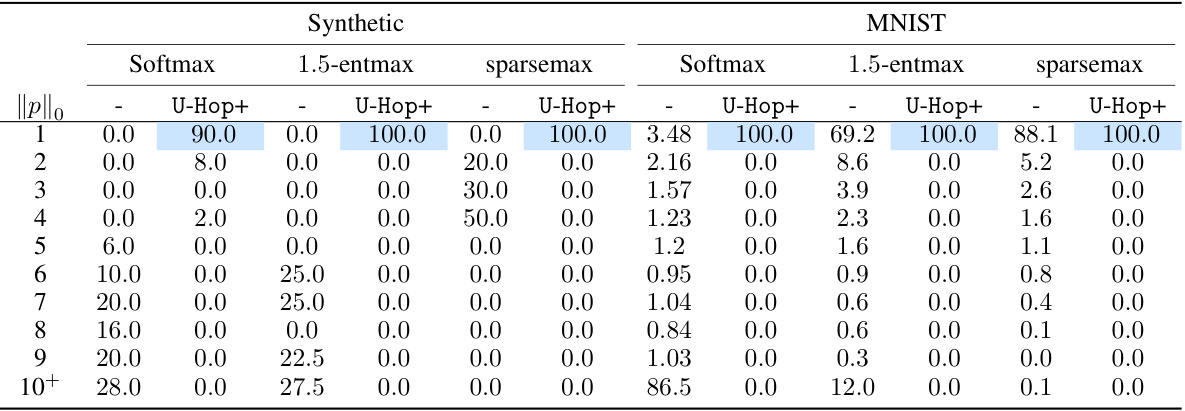

This table shows the distribution of metastable states for different models (Softmax, 1.5-entmax, sparsemax) with and without the U-Hop+ algorithm, on both synthetic and MNIST datasets. A metastable state represents a situation where the model’s retrieval process converges to a mixture of memories instead of a single memory. The size of a metastable state (||p||) indicates the number of memories involved in this mixture. The table illustrates that U-Hop+ significantly reduces the proportion of metastable states, particularly for larger state sizes.

In-depth insights#

Optimal KHM Capacity#

The optimal capacity of Kernelized Hopfield Models (KHMs) is a crucial aspect of their effectiveness as associative memory systems. The key insight is the connection between KHM memory configuration and spherical codes. By treating the stored memories as points on a hypersphere, analysis shifts to a geometric problem of optimal point arrangement. Optimal capacity is achieved when memories form an optimal spherical code, maximizing the minimum angular distance between any two memories. This perspective allows for a tight capacity bound analysis, matching known exponential lower bounds and providing the first optimal asymptotic capacity for modern Hopfield models. This theoretical understanding is complemented by a sublinear-time algorithm (U-Hop+) designed to reach this optimal capacity. The analysis clarifies how KHMs’ learnable feature maps influence memory capacity, linking theoretical optimality to practical algorithm design and improved retrieval capabilities. This approach significantly advances the understanding and application of KHMs in both associative memory and transformer-based architectures.

Spherical Code Theory#

Spherical code theory offers a powerful framework for analyzing the optimal memory capacity of Hopfield-like neural networks. By representing stored memories as points on a hypersphere, the theory elegantly transforms the memorization problem into a geometrical one of optimal point arrangement. The minimal angular distance between any two memory points becomes crucial, directly impacting retrieval accuracy and overall storage capacity. An optimal spherical code, maximizing this minimal distance, provides a theoretical upper bound on memory capacity, offering valuable insights into the design of efficient associative memories. The connection between well-separated spherical codes and the capacity of Hopfield networks highlights the importance of memory distribution and representation learning, providing directions for enhancing retrieval performance and understanding the limitations of existing models.

U-Hop+ Algorithm#

The U-Hop+ algorithm, a key contribution of the research paper, presents a novel sublinear time approach to achieving optimal memory capacity in Kernelized Hopfield Models (KHMs). It directly addresses the challenge of finding an optimal feature map (Φ) that maximizes the minimum separation (ΔΦmin) between stored memories in the feature space. This is crucial because a larger ΔΦmin leads to better memory storage and retrieval capabilities. Unlike previous methods that relied on surrogates or approximations, U-Hop+ leverages the concept of spherical codes and, through a carefully designed optimization process (projected gradient descent), efficiently searches for the optimal Φ. The algorithm’s sublinear time complexity makes it computationally efficient, especially beneficial when dealing with a large number of memories. Theoretical analysis proves that as the temperature approaches zero, U-Hop+ converges to the optimal solution, thus bridging theory and practice. The effectiveness of U-Hop+ is demonstrated through numerical experiments showing a significant reduction in metastable states and faster convergence, validating its capacity to improve KHM performance and representation learning.

Memory Code Analysis#

A hypothetical ‘Memory Code Analysis’ section would delve into the mathematical representation of memories as codes, likely focusing on high-dimensional spaces. It would likely explore how the properties of these codes, such as distance and orthogonality, affect memory storage capacity and retrieval accuracy. The analysis would probably involve tools from information theory and coding theory, potentially drawing connections to concepts like spherical codes and packing bounds. A key aspect might involve demonstrating how well-separated memory codes lead to better performance, tying directly into the model’s ability to avoid confusion between similar memories. Optimal memory capacity would likely be framed in terms of achieving the most efficient and robust code structure, possibly drawing parallels between code properties and the model’s convergence behavior. Finally, the analysis would likely discuss the practical implications of using these optimal codes for memory management within the model, highlighting the trade-offs between capacity and algorithmic complexity.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on optimal memory capacity in Kernelized Hopfield Models (KHMs) could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis beyond linear feature maps to encompass more complex, potentially non-linear mappings would unlock a deeper understanding of KHMs’ capacity limits. This could involve investigating different kernel functions or exploring the application of deep learning architectures to learn optimal feature transformations. Investigating the impact of various normalization functions, beyond softmax, entmax, and sparsemax, on memory capacity and retrieval accuracy is crucial to achieving optimal performance in different scenarios. A thorough examination of the influence of these normalization methods on the energy landscape could lead to significant advancements in model design. Furthermore, a comprehensive exploration of the relationship between the feature dimension and the number of storable memories is needed to optimize the model’s scalability and efficiency. This might involve deriving tighter bounds or developing more sophisticated algorithms for feature space dimension selection. Finally, research should focus on developing practical applications of the improved KHMs, particularly in areas like large language models, brain-machine interfaces, and other domains where efficient content-addressable memory is crucial. Experimental validation of these applications would demonstrate the practical impact of the theoretical contributions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure visualizes the basins of attraction for different numbers of iterations of Algorithm 1. It compares the raw basins of attraction (without U-Hop+ or KHM) to those after 1, 2, and 5 iterations. Each color represents a different memory, while white indicates queries that don’t converge to a single memory. The results show that U-Hop+ improves convergence to fixed points and reduces metastable states.

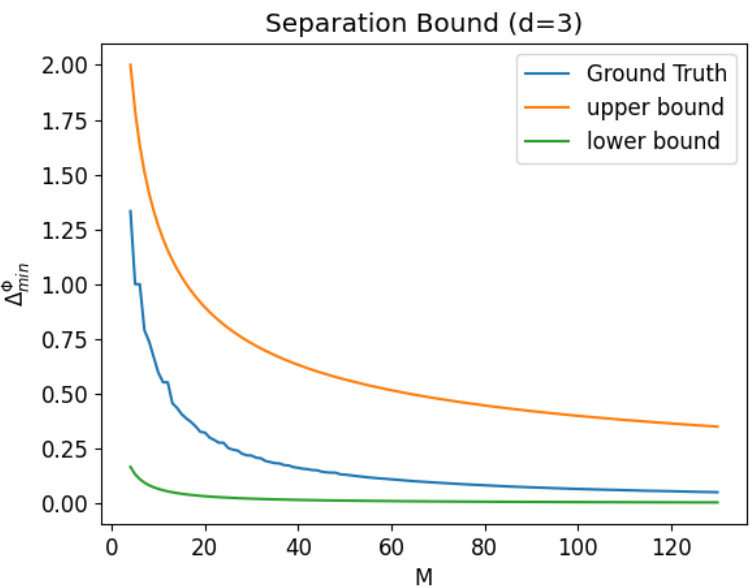

This figure shows a numerical simulation of the bound presented in Proposition 3.1 of the paper, which deals with the minimal separation in 3 dimensions. The plot compares the theoretical upper and lower bounds with the empirically observed minimal separation (ground truth) as the number of points (M) increases. The results indicate that the bound becomes tighter (more accurate) as the number of points increases.

This figure visualizes the results of an experiment on a point assignment problem in 2D space. The goal was to see if the learned feature map from the U-Hop+ algorithm would place semantically similar items closer together, even without explicitly incorporating semantic information into the algorithm’s training. The plot shows the arrangement of six points (representing different image classes from CIFAR10) on a unit circle after the feature map learned these points via Algorithm 1. As shown, semantically similar pairs were placed closer together in most trials, suggesting that the algorithm implicitly learns and preserves semantic relationships.

This figure shows the loss curves for the average separation loss (L) during the training process of the U-Hop+ algorithm. Two different memory set sizes (M=100 and M=200) are compared. The x-axis represents the training epoch, and the y-axis represents the value of the loss function L. The plot demonstrates the convergence of the algorithm, showing that the loss decreases quickly within the first few epochs and then plateaus, indicating the algorithm’s fast convergence speed which confirms the sub-linear time complexity of the algorithm, as theoretically analyzed in the paper.

More on tables

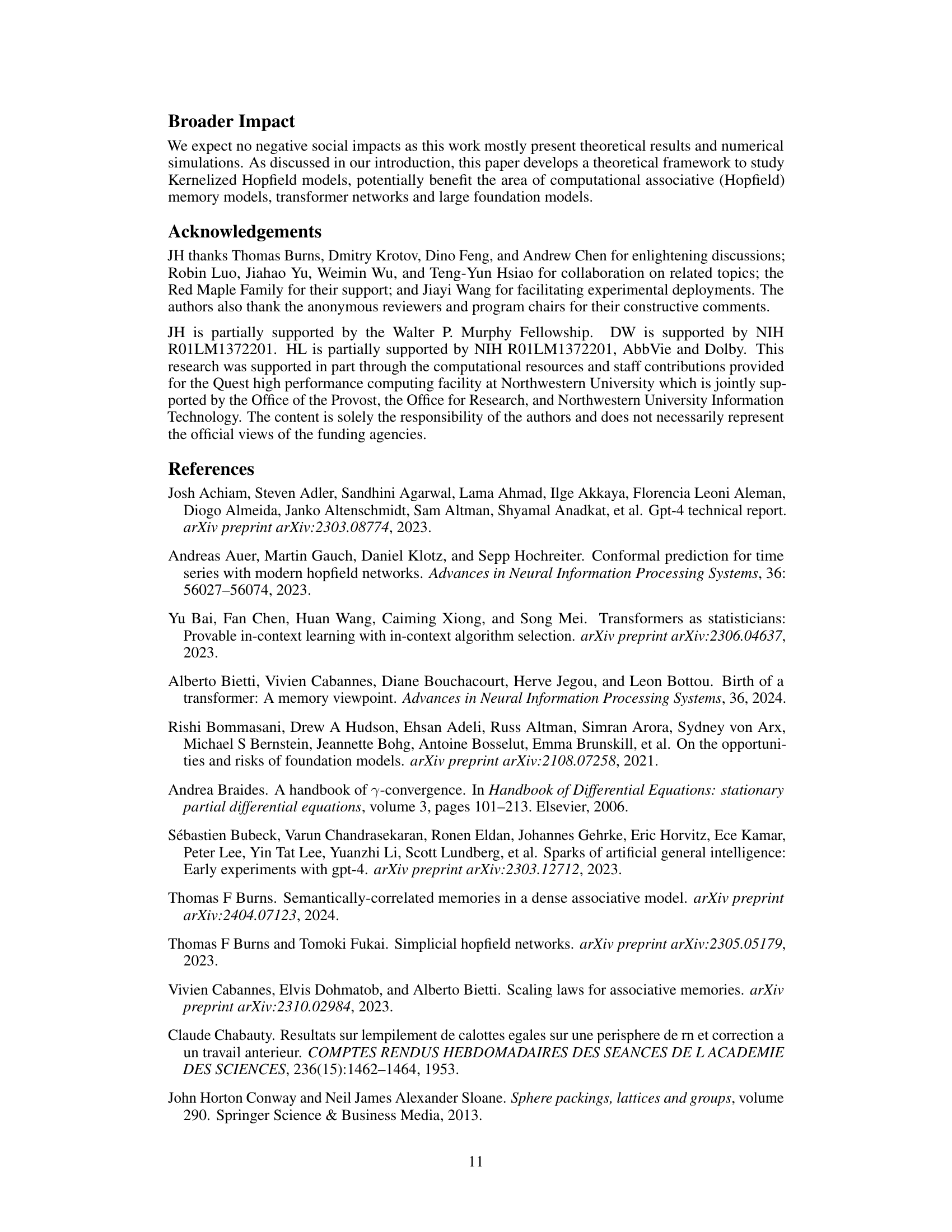

This table presents the test Area Under the Curve (AUC) scores for multiple instance learning on four datasets. It compares the performance of HopfieldPooling models with and without the U-Hop+ algorithm, using dense and sparse modern Hopfield models as baselines. The results demonstrate that U-Hop+ improves performance even without hyperparameter optimization.

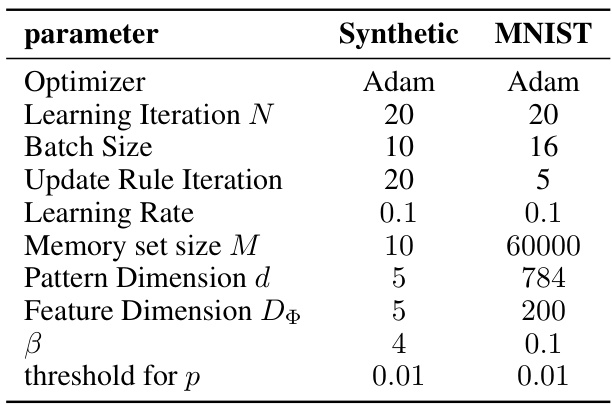

This table presents the distribution of metastable states for different softmax variants (Softmax, 1.5-entmax, sparsemax) and for both synthetic and MNIST datasets. The size of a metastable state (||p||) is the number of non-zero entries in the probability distribution. A size of 1 indicates that the system converges to a single memory, while larger sizes indicate convergence to a mixture of memories. The table demonstrates the impact of the U-Hop+ algorithm on reducing the size of metastable states, indicating improved memory capacity. The data was obtained under specific experimental conditions detailed in Table 3.

This table shows the distribution of metastable states for different models and datasets (synthetic and MNIST). A metastable state represents the convergence of the Hopfield model update to a state that is not a single memory but rather a mixture of memories. The size of the metastable state, denoted as ||p||, indicates the number of non-zero entries in the probability distribution. The table compares different softmax variants (softmax, 1.5-entmax, sparsemax) along with the use of the U-Hop+ algorithm. A threshold of 0.01 is applied to the softmax probability distribution to determine non-zero values. Hyperparameters used are specified in Table 3 of the paper.

This table lists the hyperparameters used in the basins of attraction experiment. It includes settings for the optimizer, learning iterations, update rule iterations, learning rate, memory set size, pattern and feature dimensions, beta parameter, and query grid resolution.

Full paper#