↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Adaptive learning rate algorithms are widely used in machine learning, but their dynamics, especially in high dimensions, are not well-understood. Existing analyses often rely on worst-case scenarios or simplifying assumptions, failing to capture the nuances of real-world optimization problems. This limits our ability to precisely compare algorithms’ performance and design better strategies.

This paper addresses these limitations by developing a novel framework for analyzing stochastic adaptive learning rate algorithms using a deterministic system of ODEs. The analysis reveals that the data covariance matrix significantly influences the training dynamics and performance of these algorithms. For instance, a simple, commonly used adaptive strategy, the exact line search, can exhibit arbitrarily slower convergence than the best fixed learning rate. The authors also provide a detailed analysis of AdaGrad-Norm, demonstrating its convergence to a deterministic constant in certain situations and identifying a phase transition when the eigenvalues follow a power-law distribution.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in optimization and machine learning because it provides a novel framework for analyzing the dynamics of stochastic adaptive learning rate algorithms, particularly in high-dimensional settings. This framework enables more precise performance comparisons between different algorithms, reveals the impact of data covariance structure on optimization, and opens new avenues for designing and analyzing more efficient adaptive methods.

Visual Insights#

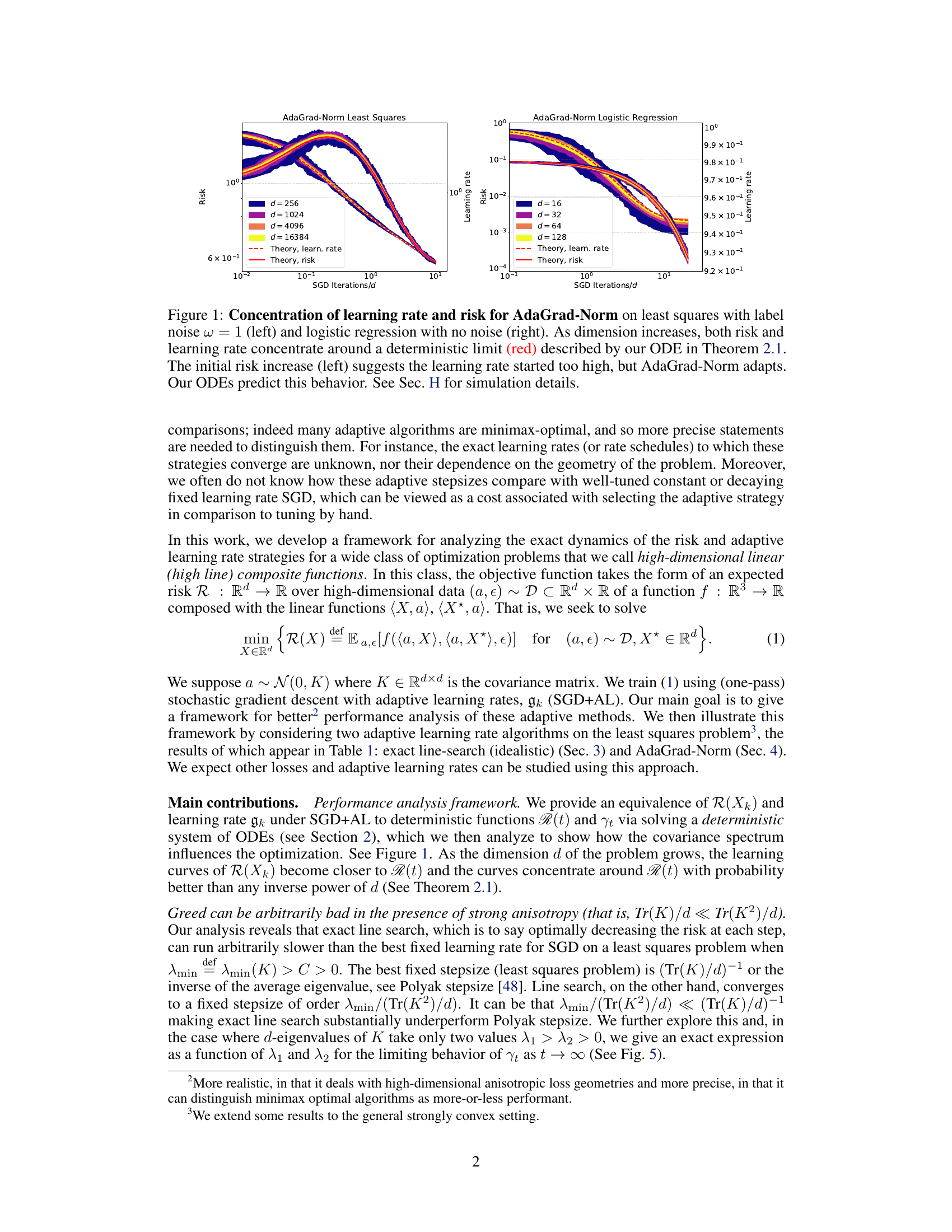

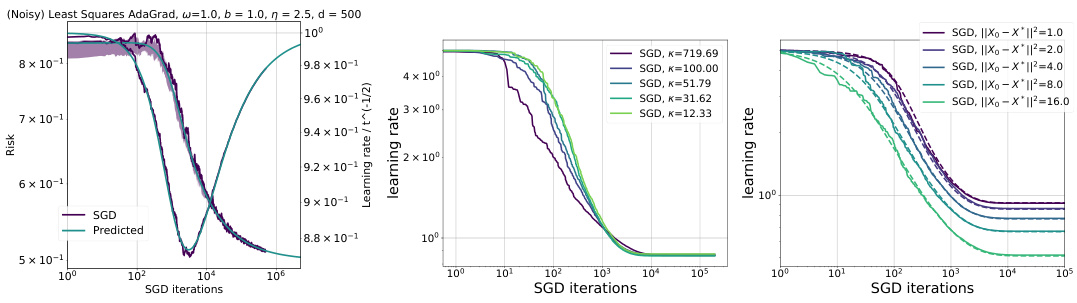

This figure shows the convergence of the risk and learning rate for AdaGrad-Norm on least squares (left) and logistic regression (right) problems. The key observation is that as the dimensionality (d) of the problem increases, both the risk and the learning rate converge to a deterministic limit, which is predicted by a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) derived in the paper. The left panel shows that although the learning rate initially starts high, AdaGrad-Norm adapts and the risk decreases to the deterministic limit. The right panel shows a similar convergence for the logistic regression problem.

This table summarizes the convergence rates of different adaptive learning rate algorithms (AdaGrad-Norm, Exact Line Search, and Polyak Stepsize) applied to the least squares problem under different assumptions on the data covariance matrix (specifically, when the smallest eigenvalue is bounded away from zero, and when the eigenvalues follow a power-law distribution). It shows the limiting learning rate and the convergence rate of the risk function for each algorithm and assumption. The table highlights the impact of covariance matrix properties on the performance of different adaptive learning rates, showing how different assumptions influence the rate at which the risk converges to its minimum.

In-depth insights#

Adaptive SGD+AL#

Adaptive SGD+AL (Stochastic Gradient Descent with Adaptive Learning rate) represents a significant advancement in optimization algorithms. It combines the efficiency of SGD, which updates model parameters iteratively using randomly sampled data points, with adaptive learning rate methods that dynamically adjust the step size during the learning process. Adaptivity is crucial as fixed learning rates often struggle to balance exploration and exploitation; they may converge too slowly or oscillate. The adaptive approach directly addresses this by modifying the step size based on the observed gradient, data characteristics, or other relevant metrics. This dynamic adjustment allows for faster convergence and better generalization in various optimization tasks, particularly those with non-stationary dynamics or complex loss landscapes. The algorithm’s effectiveness hinges on the specific adaptive learning rate strategy employed. Popular choices include AdaGrad, Adam, RMSprop, and their variants, each with its strengths and weaknesses regarding convergence speed, robustness, and computational overhead. The choice of adaptive learning rate significantly impacts the algorithm’s performance, making careful selection and tuning a key aspect of practical implementation. Furthermore, theoretical analysis of adaptive SGD+AL is ongoing, with researchers actively investigating convergence guarantees and exploring the relationship between data properties, algorithmic parameters, and optimization outcomes. Future research may focus on developing more sophisticated adaptation strategies, extending the theoretical understanding, and exploring novel applications in diverse machine learning areas.

High-Dimensional ODEs#

The concept of “High-Dimensional ODEs” in the context of this research paper likely refers to the use of systems of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to model the behavior of stochastic gradient descent (SGD) algorithms in high-dimensional spaces. The high dimensionality is crucial, as it allows for the derivation of deterministic dynamics that approximate the stochastic behavior of SGD, providing a powerful tool for analysis. These ODEs are not just a simple extension of low-dimensional ODEs; they capture the nuanced interactions of gradients and learning rates within the complex geometry of high-dimensional loss landscapes. The key insight is that these ODEs reveal a deterministic limit to the apparently random training dynamics. This opens up avenues to rigorously analyze algorithm performance, including the effects of adaptive learning rates. By modeling such things, researchers are able to gain a deeper theoretical understanding of the convergence speed, stability, and generalization ability of these algorithms. The transition to ODEs facilitates a deeper study of the impact of data covariance structure on algorithm performance, which is often difficult to analyze directly in the stochastic setting. The effectiveness of adaptive stepsize methods is also a significant focus because they aim to address the challenges in high dimensions.

Line Search Limits#

The concept of “Line Search Limits” in the context of optimization algorithms investigates the inherent boundaries and potential inefficiencies of line search methods. Line search, a powerful technique for finding optimal step sizes in iterative optimization, aims to minimize the objective function along a given search direction. However, the effectiveness of line search is limited by several factors. Firstly, the computational cost of performing an exact line search can be substantial, especially in high-dimensional spaces. Secondly, the accuracy of the line search can be affected by noise or inaccuracies in the gradient calculations. In noisy environments, an exact line search might lead to oscillatory behavior or even fail to converge. Thirdly, the choice of search interval significantly impacts performance. A poorly chosen interval might miss the true minimum. Finally, line search methods may struggle in non-convex optimization landscapes, where multiple local minima exist, potentially leading to premature convergence to a suboptimal solution. Understanding these limitations is crucial for effectively designing and applying optimization algorithms, suggesting the need for alternative strategies such as adaptive learning rates or trust-region methods in certain scenarios.

AdaGrad-Norm Dynamics#

The section on ‘AdaGrad-Norm Dynamics’ would likely explore the behavior of the AdaGrad-Norm algorithm in the context of the paper’s overall high-dimensional linear composite function optimization framework. A key aspect would be the derivation and analysis of the learning rate dynamics. The authors would likely present a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that govern the evolution of the learning rate and risk functions over time. These ODEs would reveal how the learning rate adapts to the data covariance matrix’s spectrum. Specific analysis would likely focus on the asymptotic behavior of the learning rate, characterizing its convergence properties under different data and hyperparameter settings. This might involve identifying phase transitions in the learning rate’s convergence speed, depending on factors such as the data covariance’s eigenvalue distribution and the presence of label noise. Furthermore, comparisons with other adaptive learning rate algorithms (such as idealized line search or Polyak stepsize) could highlight AdaGrad-Norm’s relative strengths and weaknesses in different scenarios. The analysis would likely delve into how the algorithm’s dynamics are influenced by the interplay between the problem’s geometry (anisotropy) and the stochastic nature of the data.

Power Law Phase#

A power law phase transition in the context of high-dimensional optimization signifies a dramatic shift in the behavior of an algorithm as the distribution of eigenvalues of the data covariance matrix transitions from a regime where eigenvalues are concentrated to one where they exhibit a power-law distribution. This transition manifests as a change in the convergence rate of the algorithm. In simpler terms, before the transition the algorithm’s efficiency is relatively predictable, but beyond the transition, the algorithm’s behavior becomes highly sensitive to the details of eigenvalue distribution, potentially exhibiting much slower convergence. The emergence of such a phase transition highlights the crucial role of the data’s underlying geometry in determining optimization algorithm success and underscores the need for algorithms robust to strong anisotropies present in real-world datasets. Understanding this phenomenon is critical for improving algorithms and predicting their performance in high-dimensional settings. The point at which the transition occurs (the critical point) would depend on properties like the power-law exponent and the specifics of the adaptive learning rate algorithm involved.

More visual insights#

More on figures

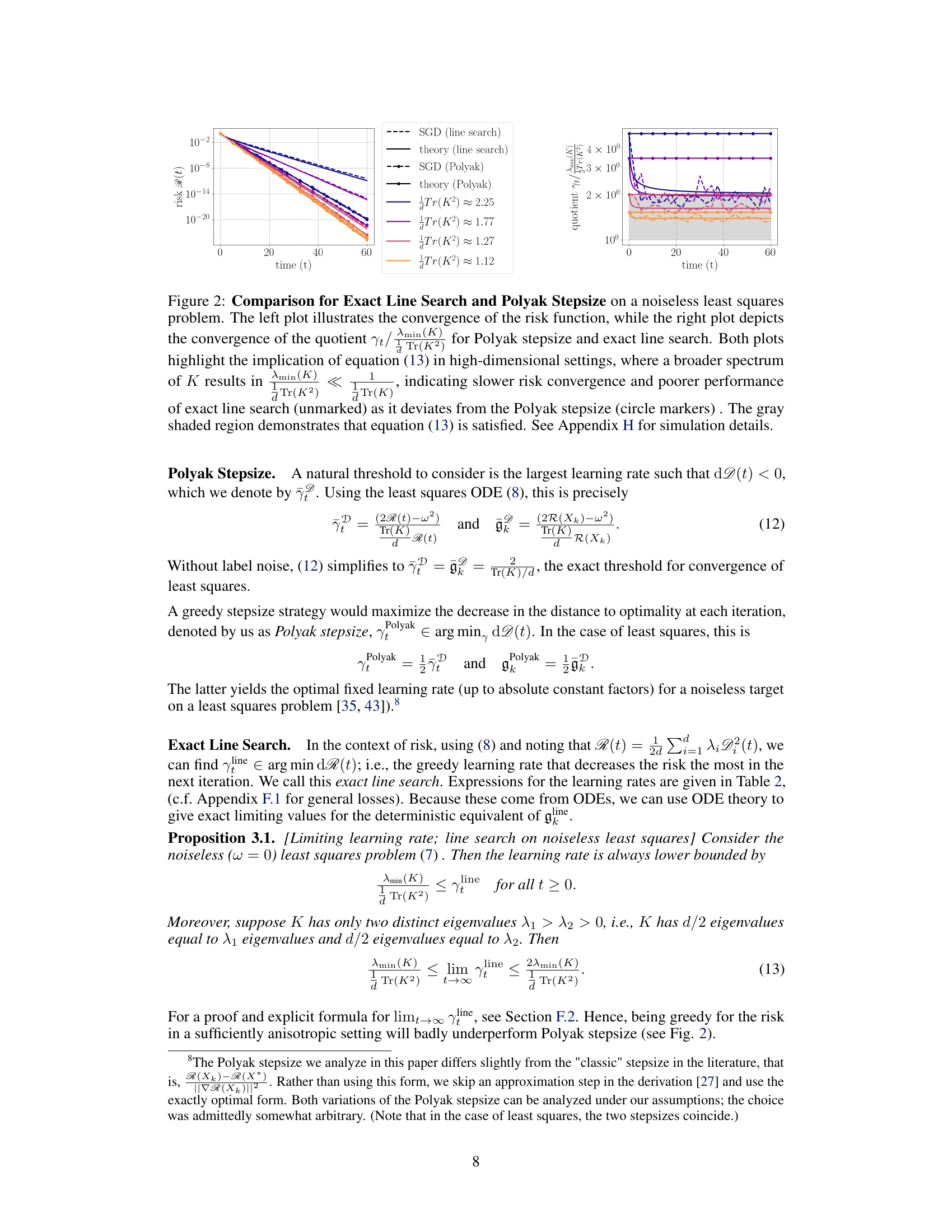

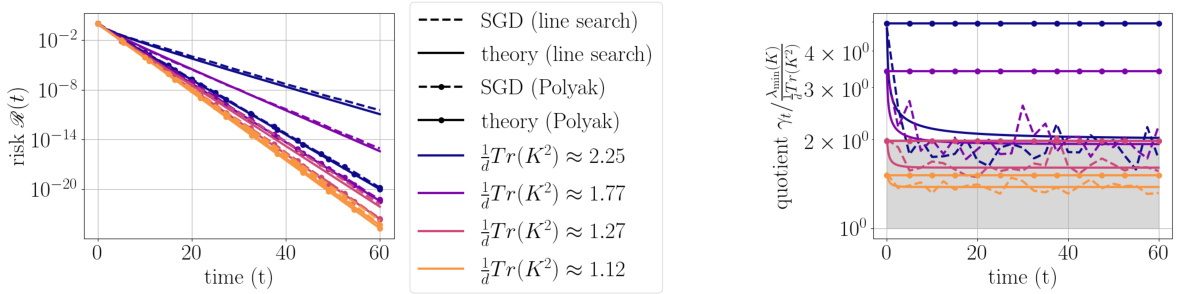

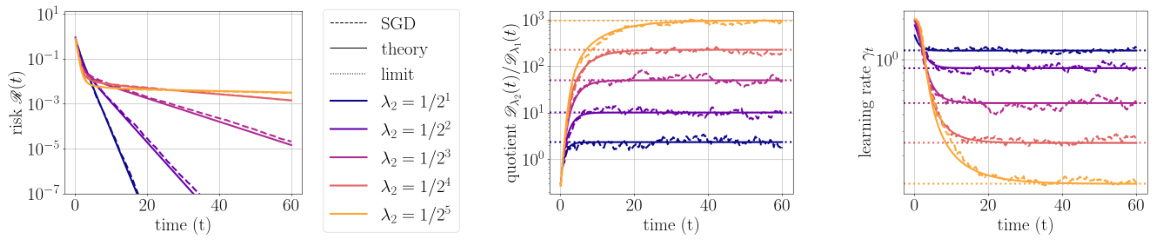

This figure compares the performance of exact line search and Polyak stepsize in a noiseless least squares problem. The left plot shows the convergence of the risk function for both methods, highlighting how exact line search can converge much slower than Polyak stepsize, especially when the covariance matrix K has a broader spectrum. The right plot visualizes this difference by showing the quotient γt/λmin(K) over time.

This figure shows the impact of noise and the initial distance from the optimum on the AdaGrad-Norm learning rate. The left panel shows that with noise, the learning rate decays as t⁻¹⁄², regardless of the covariance structure. The center and right panels show that without noise, the learning rate approaches a constant inversely proportional to the average eigenvalue of the covariance matrix, and scales with the initial distance from the optimum. The simulation results match the theoretical predictions.

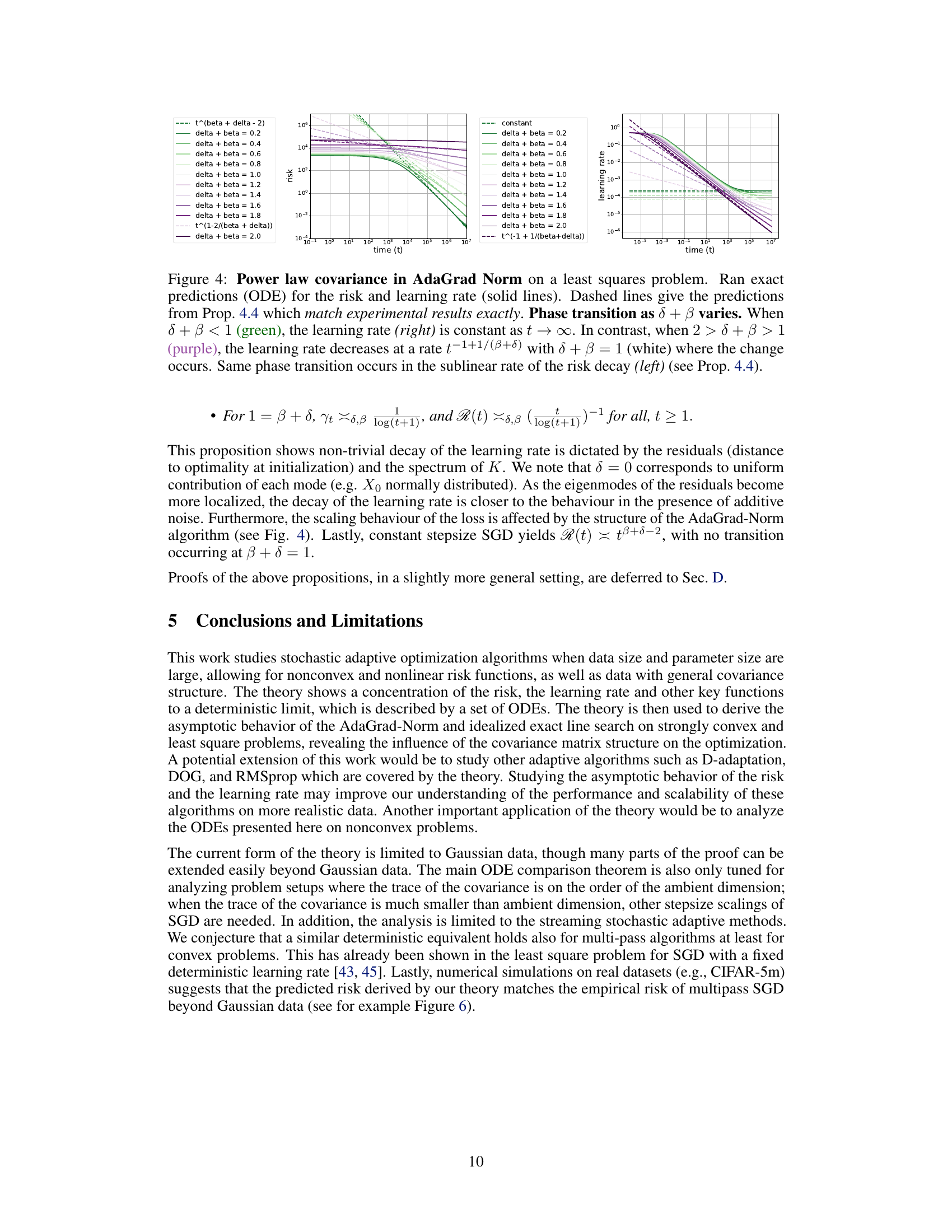

This figure shows the phase transition of the risk and learning rate in AdaGrad-Norm algorithm when the eigenvalues follow a power law distribution. The x-axis represents time, and the y-axis represents risk and learning rate. The different colored lines represent different values of δ + β. When δ + β < 1, the learning rate is constant, while when 1 < δ + β < 2, the learning rate decays. The risk shows a similar phase transition.

This figure shows the convergence of exact line search in a noiseless least squares problem. The left plot displays the convergence of risk, the center plot shows the quotient of learning rate over minimum eigenvalue, and the right plot shows the learning rate itself. The plots illustrate how the algorithm’s performance relates to the data’s spectral properties, specifically the ratio of minimum to average eigenvalue squared. The figure demonstrates how the exact line search strategy’s convergence rate varies depending on this ratio.

This figure empirically validates the theory presented in the paper using real-world data from the CIFAR-5m dataset. It shows the training dynamics of multi-pass AdaGrad-Norm on a least-squares problem for different dataset sizes (n). The results demonstrate that the theory’s predictions hold even with non-Gaussian data and multiple passes, highlighting the model’s robustness and generalizability. The differing curves for varying dataset sizes illustrate a transition from over-parametrization (memorization) at smaller n to generalization at larger n.

Full paper#