↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current vision-language models (VLMs) struggle with decision-centric tasks like controlling real-world devices due to a lack of relevant training data and the inherent stochasticity of real-world interactions. Static demonstrations are insufficient for training such agents. This paper addresses these limitations.

DigiRL, a two-stage approach (offline RL followed by offline-to-online RL), effectively addresses these issues. By combining offline RL for initialization with online RL for continuous adaptation, DigiRL enables the training of highly robust and effective in-the-wild device control agents. The Android-in-the-Wild (AitW) dataset showcases DigiRL’s superior performance, achieving a substantial improvement over previous state-of-the-art methods. This novel approach significantly advances the field of autonomous RL for digital agents.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on autonomous digital agents and reinforcement learning. It presents a novel approach to overcome the limitations of existing methods, offering a significant step forward in the field and opening new avenues for future research. Its focus on real-world, stochastic environments and its achievement of state-of-the-art results make it especially relevant for researchers working towards practically deployable AI.

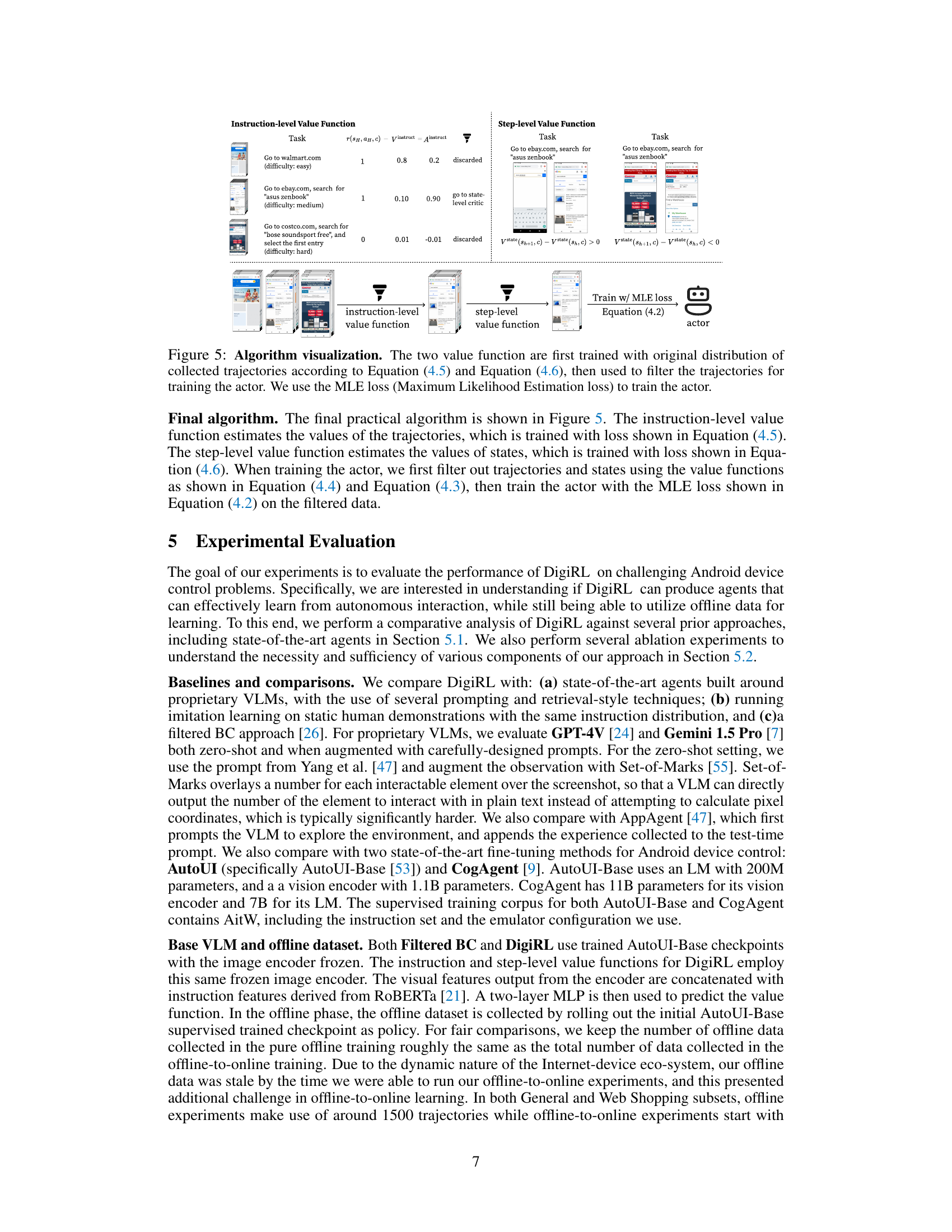

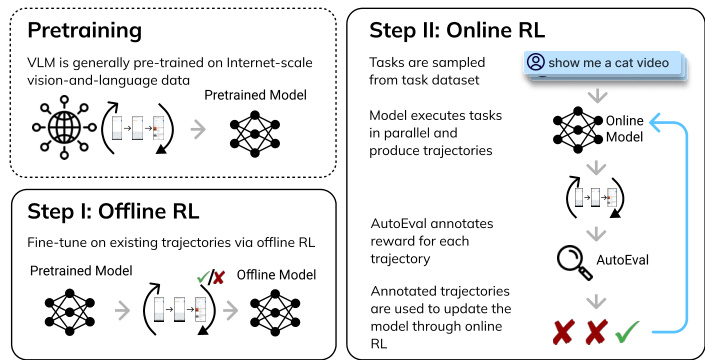

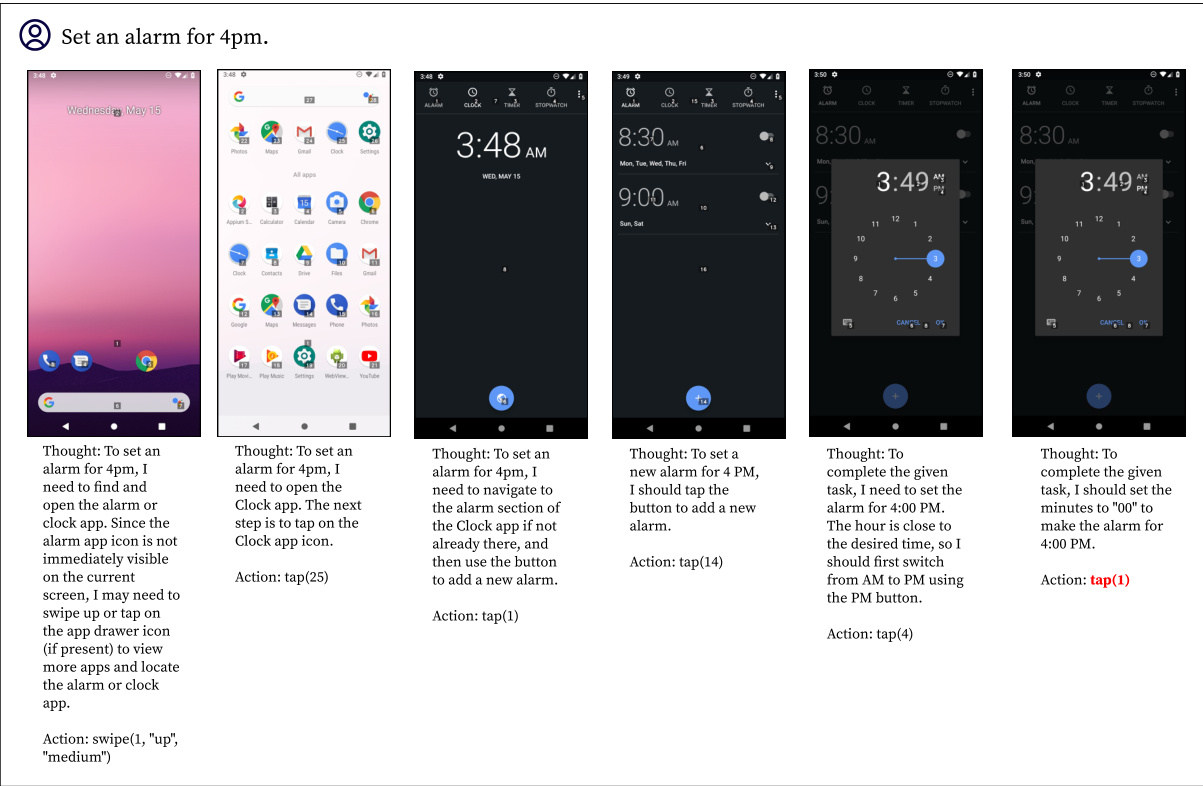

Visual Insights#

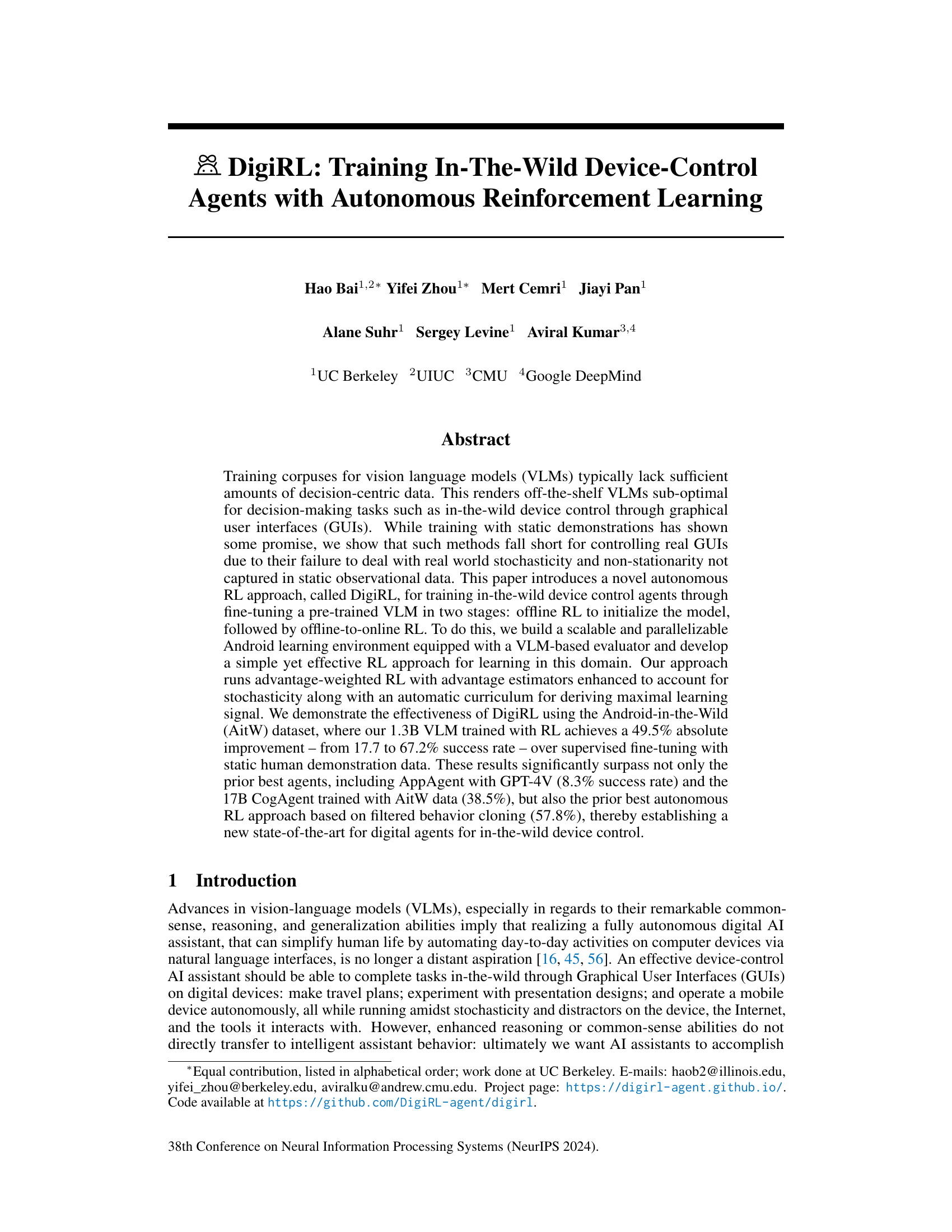

This figure provides a high-level overview of the DigiRL approach. It starts by describing the use of a pre-trained Vision-Language Model (VLM) as the foundation. The first stage involves offline reinforcement learning (RL) to fine-tune the VLM using existing trajectory data. This helps the model learn initial goal-oriented behavior. Then, the second stage introduces online RL where the agent interacts with real-world GUIs. The agent’s performance is continuously improved by the online RL process, guided by an automated evaluation system that provides rewards based on the agent’s performance.

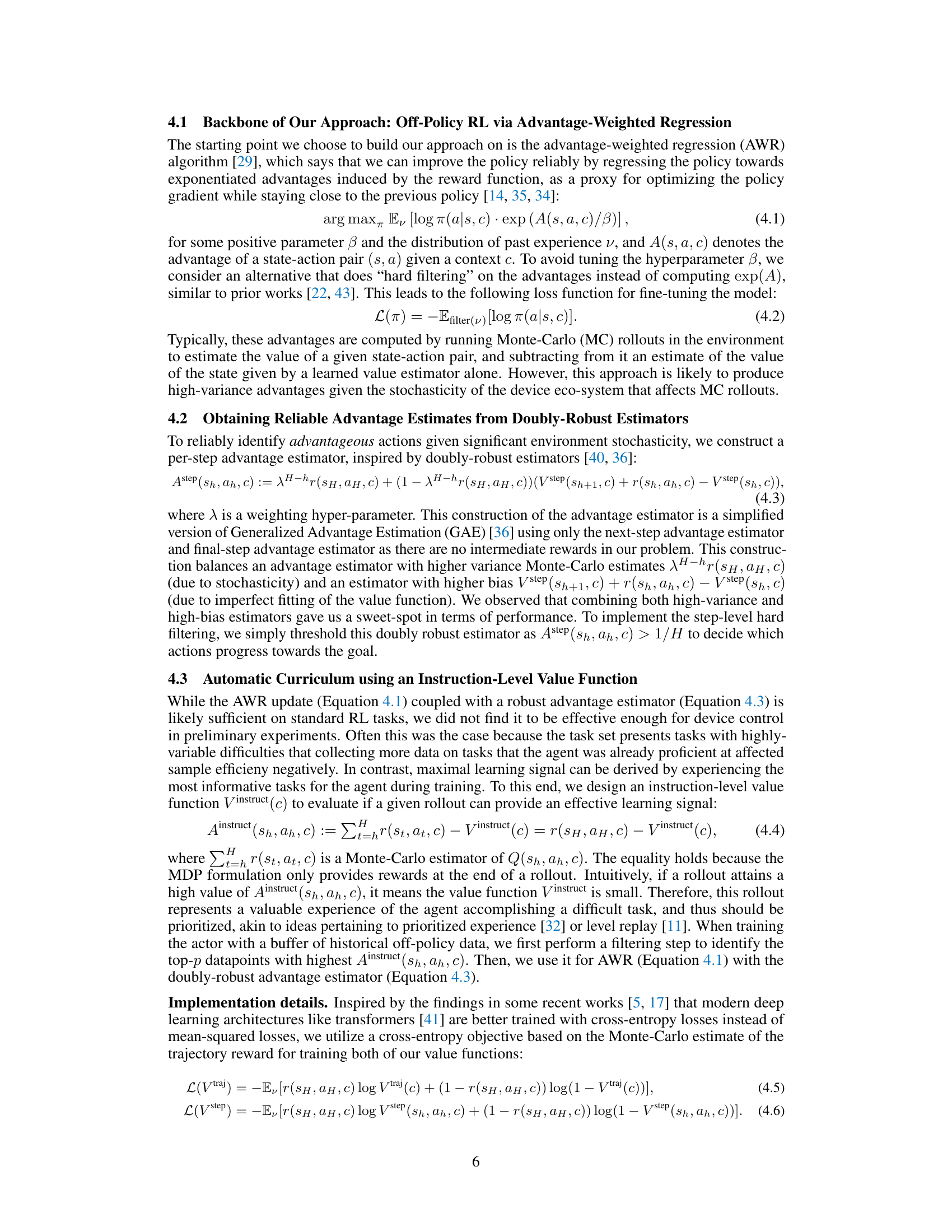

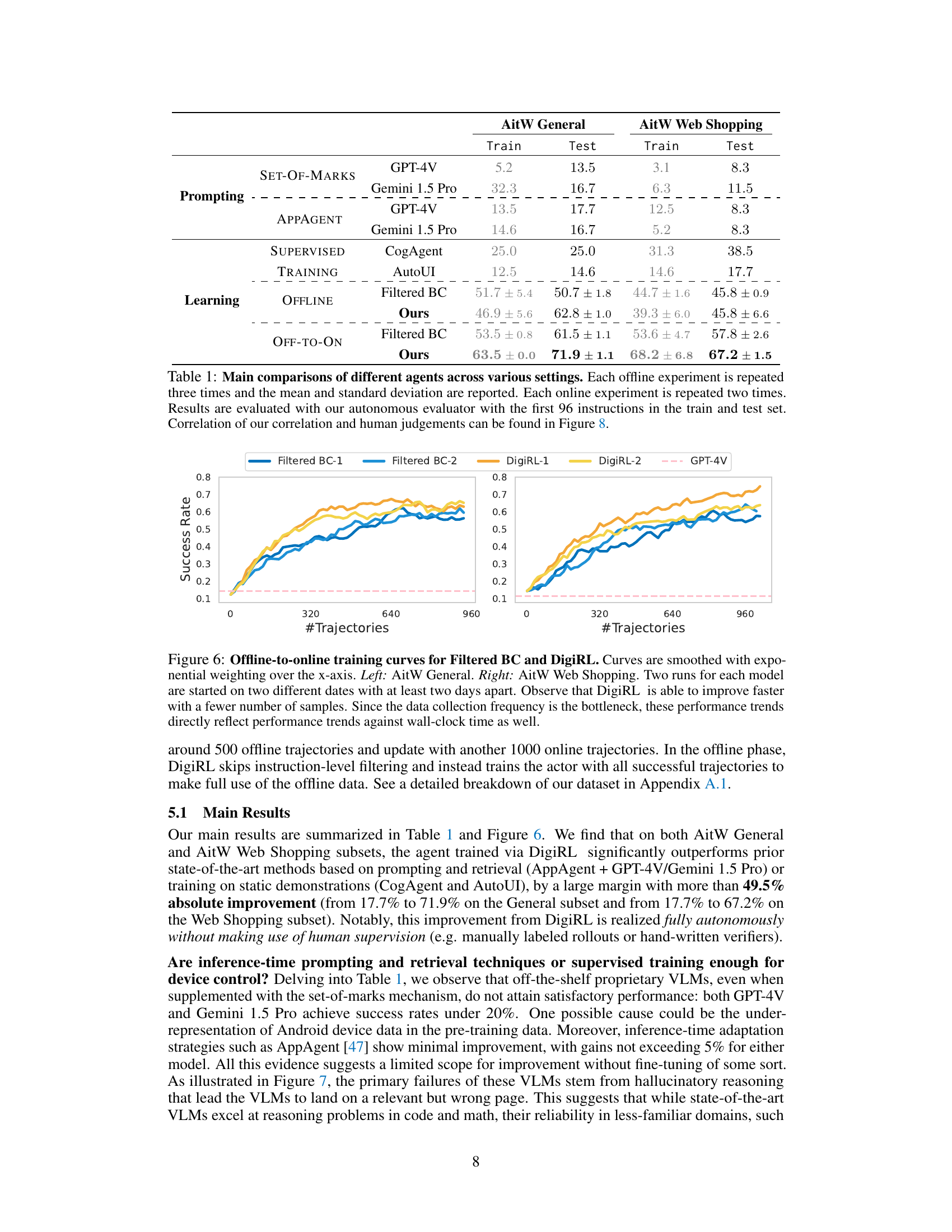

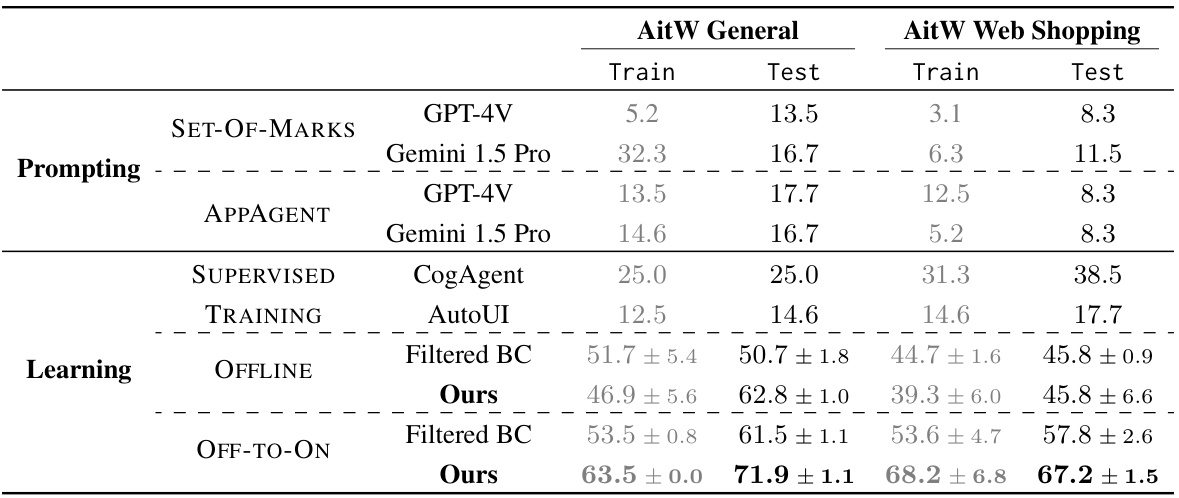

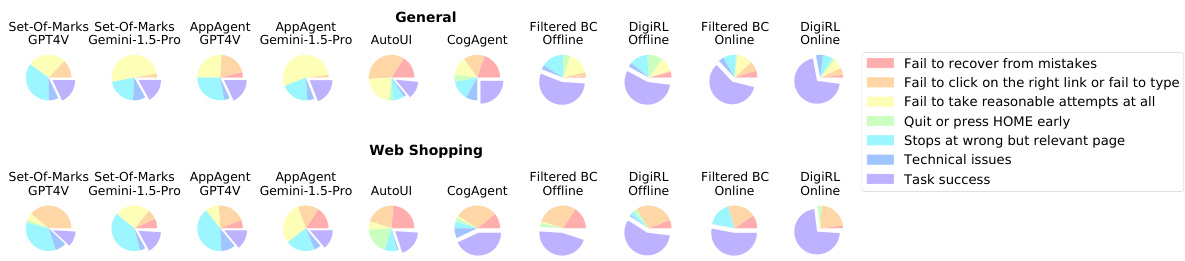

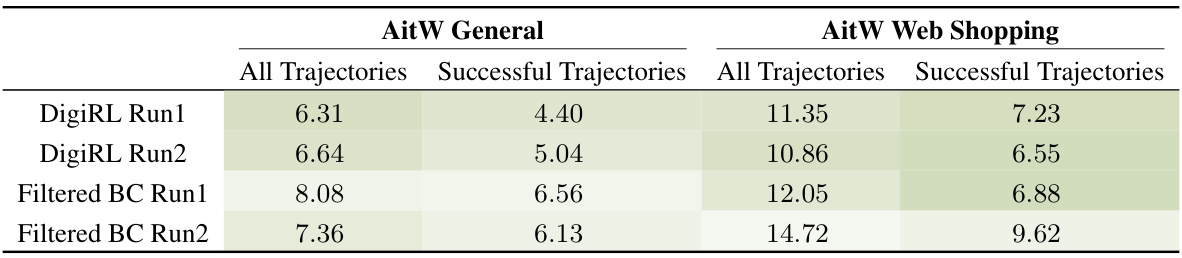

This table compares the performance of DigiRL against other state-of-the-art methods for Android device control tasks. It shows the success rate (percentage) achieved by various approaches, including those based on prompting/retrieval, supervised training, and autonomous RL (DigiRL). The table is divided into different training methods (Prompting, Supervised Training, Offline, and Off-to-On) and evaluation datasets (AitW General, AitW Web Shopping). The results highlight the superior performance of DigiRL over other methods.

In-depth insights#

DigiRL Framework#

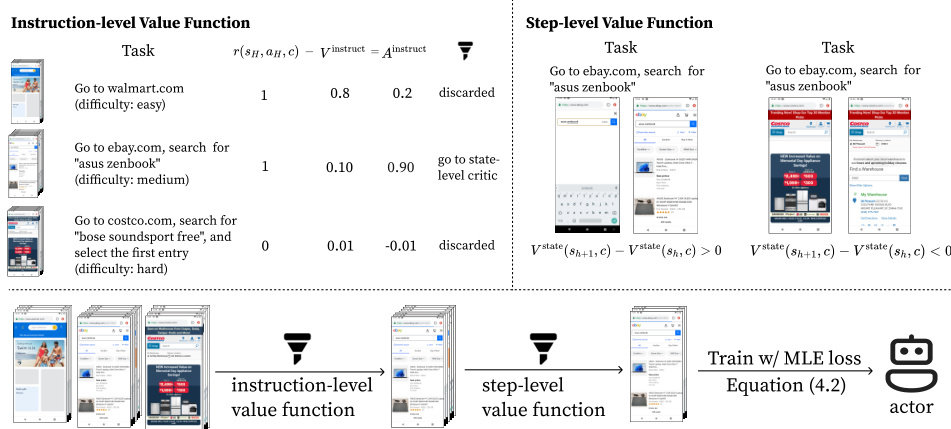

The DigiRL framework presents a novel approach to training in-the-wild device-control agents by leveraging autonomous reinforcement learning. Its core innovation lies in a two-stage training process: offline RL for model initialization using existing data and offline-to-online RL for continuous adaptation and refinement via real-world interactions. This addresses the limitations of traditional approaches that struggle with real-world stochasticity and non-stationarity. DigiRL incorporates several key enhancements to standard RL techniques, including advantage-weighted RL with improved estimators to account for stochasticity, and an automatic curriculum based on an instruction-level value function for efficient learning signal extraction. The framework also includes a scalable and parallelizable Android learning environment and a robust VLM-based evaluator, enabling real-time online learning and performance assessment. By combining offline pre-training with online autonomous RL, DigiRL achieves state-of-the-art results in in-the-wild device control, significantly surpassing both supervised fine-tuning methods and existing autonomous RL approaches.

RL for VLMs#

Reinforcement learning (RL) presents a powerful paradigm for enhancing Vision-Language Models (VLMs). Traditional VLM training primarily relies on supervised methods using large-scale datasets, often lacking the decision-centric data crucial for complex tasks. RL offers a compelling solution by directly optimizing VLM behavior for specific goals, allowing them to learn complex decision-making policies through interaction with an environment. This approach can address the limitations of static demonstrations, enabling VLMs to adapt to dynamic and stochastic environments, such as real-world GUI interactions, and generalize better to unseen situations. Offline RL methods are particularly useful to leverage existing data for pre-training, but online RL is essential for adapting to the real-world’s non-stationary nature. The combination of offline and online RL techniques offers a promising avenue to train robust and adaptive VLMs for real-world applications. However, challenges remain, including the need for efficient RL algorithms that can handle the high-dimensionality of VLM actions and states, the difficulty in designing effective reward functions that accurately reflect task success, and the computational cost of online RL. Future research should focus on addressing these challenges to unleash the full potential of RL for training advanced, adaptable VLMs.

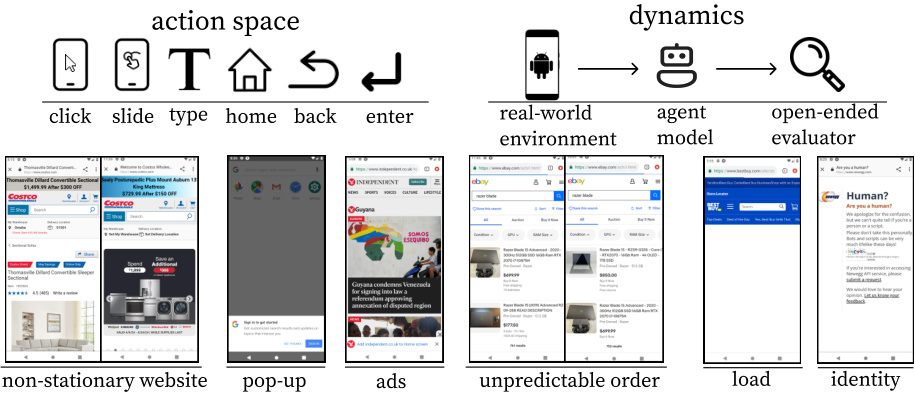

Stochasticity#

The concept of stochasticity is central to the DigiRL paper, highlighting the unpredictability inherent in real-world environments. Unlike simulated settings, real-world device control via GUIs involves numerous sources of randomness. Website layouts change, pop-up ads appear unexpectedly, network latency fluctuates, and even the device itself may behave unexpectedly. The authors emphasize how these stochastic elements make static demonstration data inadequate for training robust agents, as such data fails to capture the dynamism of real-world interactions. DigiRL’s success stems directly from its ability to learn in situ, constantly adapting to these unforeseen variations. Online RL, integrated with mechanisms for filtering out incorrect actions and automatically curating the learning signal, is key to mastering this challenge. The paper’s experiments showcase how a continuously updated model significantly outperforms those trained solely on static demonstrations, underscoring the critical role of handling stochasticity for achieving robust, generalizable performance in real-world scenarios. This highlights the need for RL methods capable of directly handling real-world noise and unpredictability in training data rather than relying on pre-trained models fine-tuned with static data.

Offline-to-Online RL#

Offline-to-online reinforcement learning (RL) represents a powerful paradigm for training agents in complex, real-world environments. It leverages the benefits of both offline and online RL, combining the sample efficiency of offline learning with the adaptability of online learning. The offline phase uses pre-collected data to pre-train the agent, initializing its policy and providing a foundation for subsequent online learning. This is particularly beneficial when online data collection is costly or dangerous, as it allows the agent to begin with some level of competence before interacting with the environment. The online phase then refines the pre-trained policy through continuous interaction with the environment, allowing the agent to adapt to unforeseen circumstances and dynamic changes. This approach is especially advantageous in scenarios with non-stationary environments, such as controlling real-world devices through GUIs. The effectiveness of offline-to-online RL hinges on several factors: the quality and representativeness of the offline data, the choice of RL algorithm and its hyperparameters, and the design of the online learning process. By strategically combining offline and online learning phases, this approach allows for efficient and robust agent training in scenarios where purely online methods might be impractical or inefficient. The approach is especially crucial for real-world applications like in-the-wild device control where the environment is inherently complex and unpredictable.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending DigiRL to other device types and operating systems beyond Android would significantly broaden its applicability. This could involve adapting the Android learning environment and the VLM-based evaluator to handle the unique characteristics of different interfaces and operating systems. Improving the robustness of DigiRL to handle even greater levels of real-world stochasticity and non-stationarity is also crucial. This could involve designing more sophisticated RL algorithms that are inherently more resilient to unexpected changes in the environment, as well as developing more effective curriculum learning strategies. Investigating more advanced RL techniques, such as model-based RL or hierarchical RL, could further enhance the efficiency and performance of DigiRL. Model-based RL could potentially reduce the amount of real-world interaction needed for training, while hierarchical RL could enable the agent to solve more complex tasks by breaking them down into smaller subtasks. Exploring the use of larger and more powerful VLMs would likely improve the generalization capabilities of DigiRL, allowing it to handle a wider range of instructions and tasks. Finally, developing more sophisticated methods for evaluating the performance of in-the-wild device control agents remains an important open problem. This includes developing more robust and comprehensive evaluation metrics, as well as developing methods for analyzing the failure modes of such agents to identify areas for improvement.

More visual insights#

More on figures

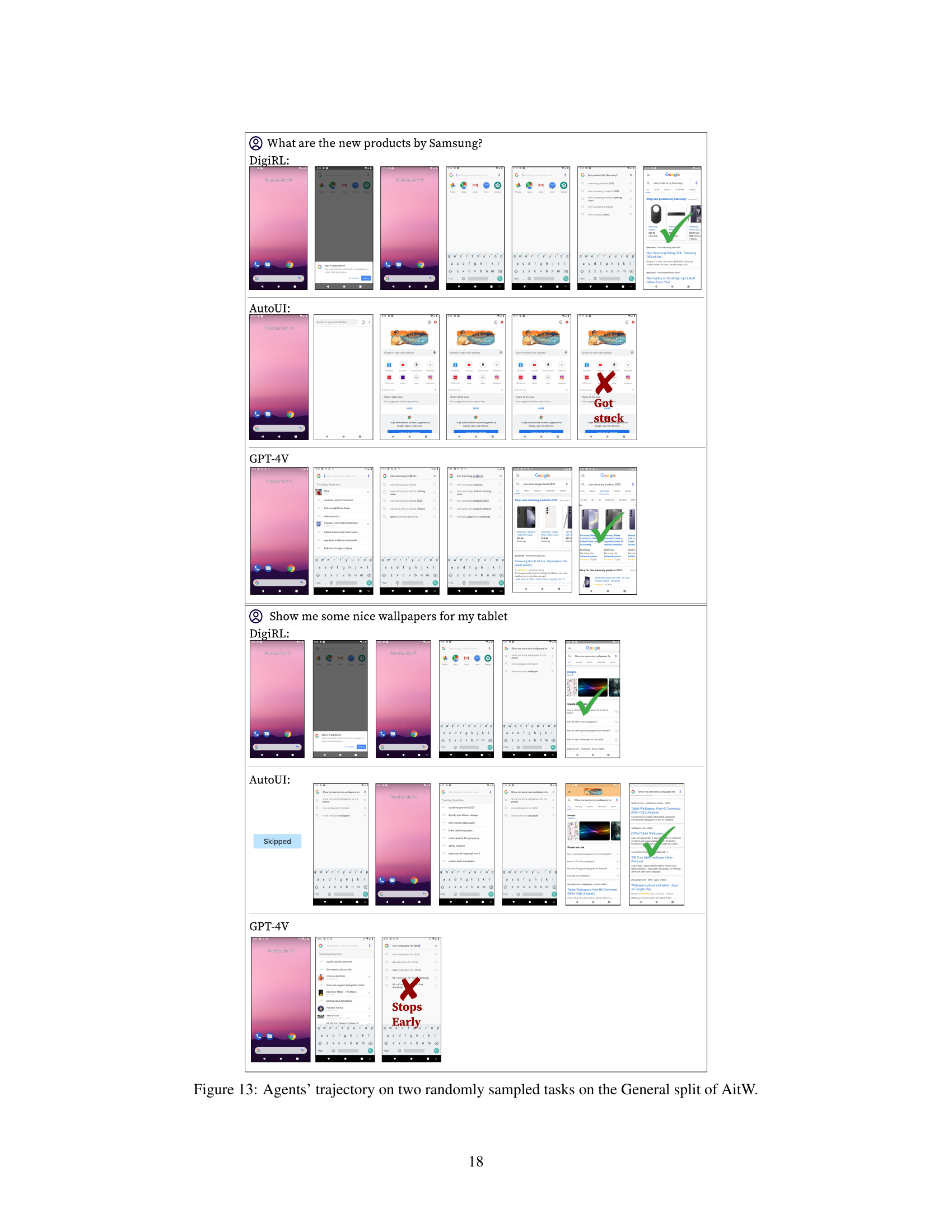

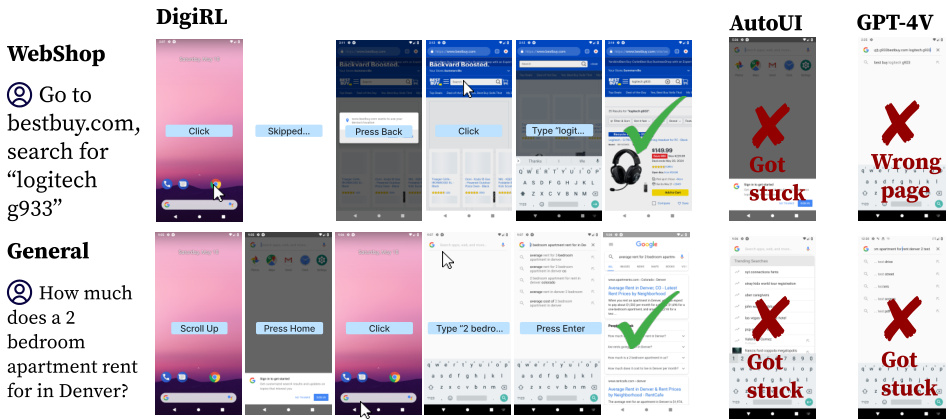

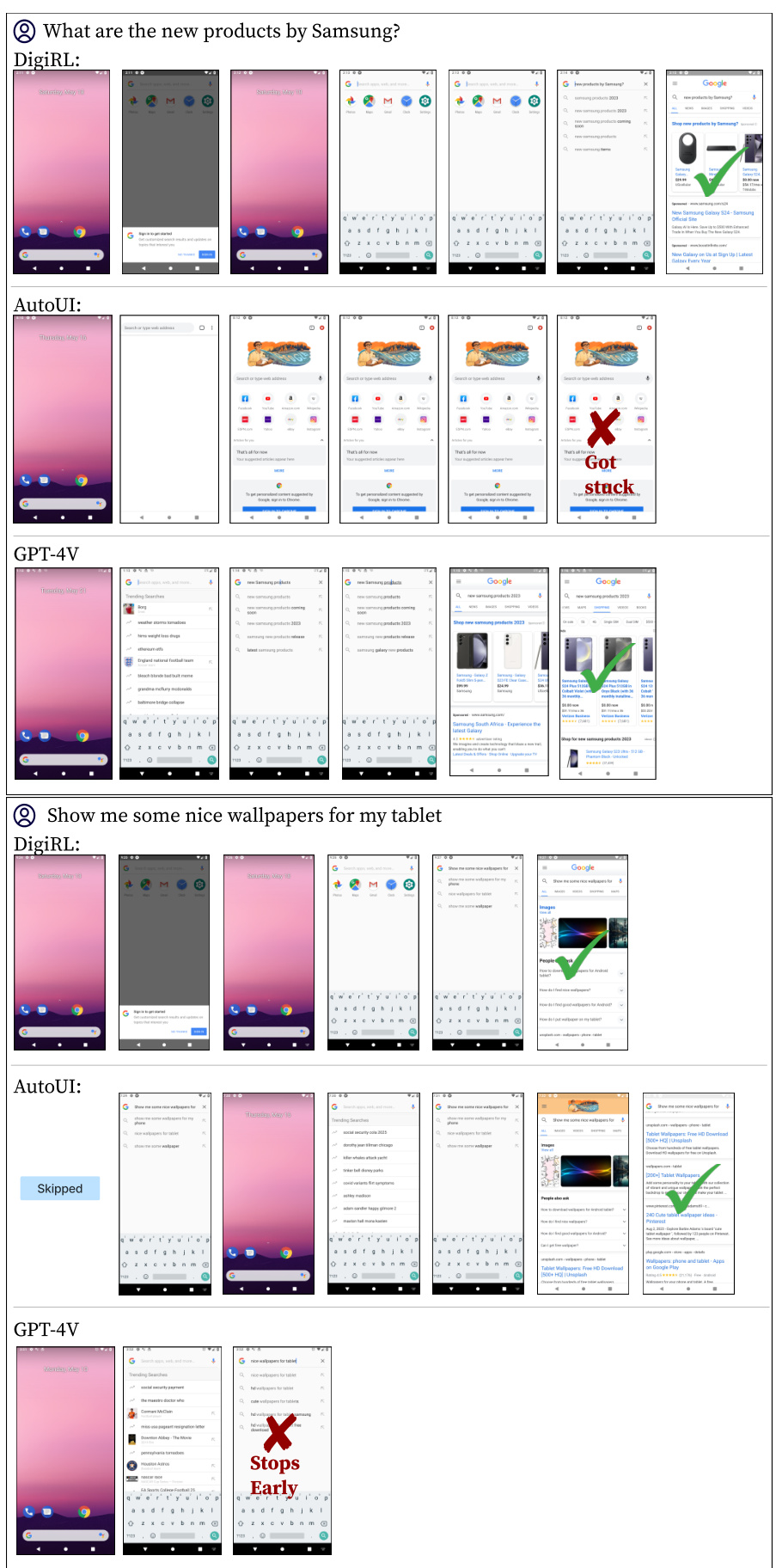

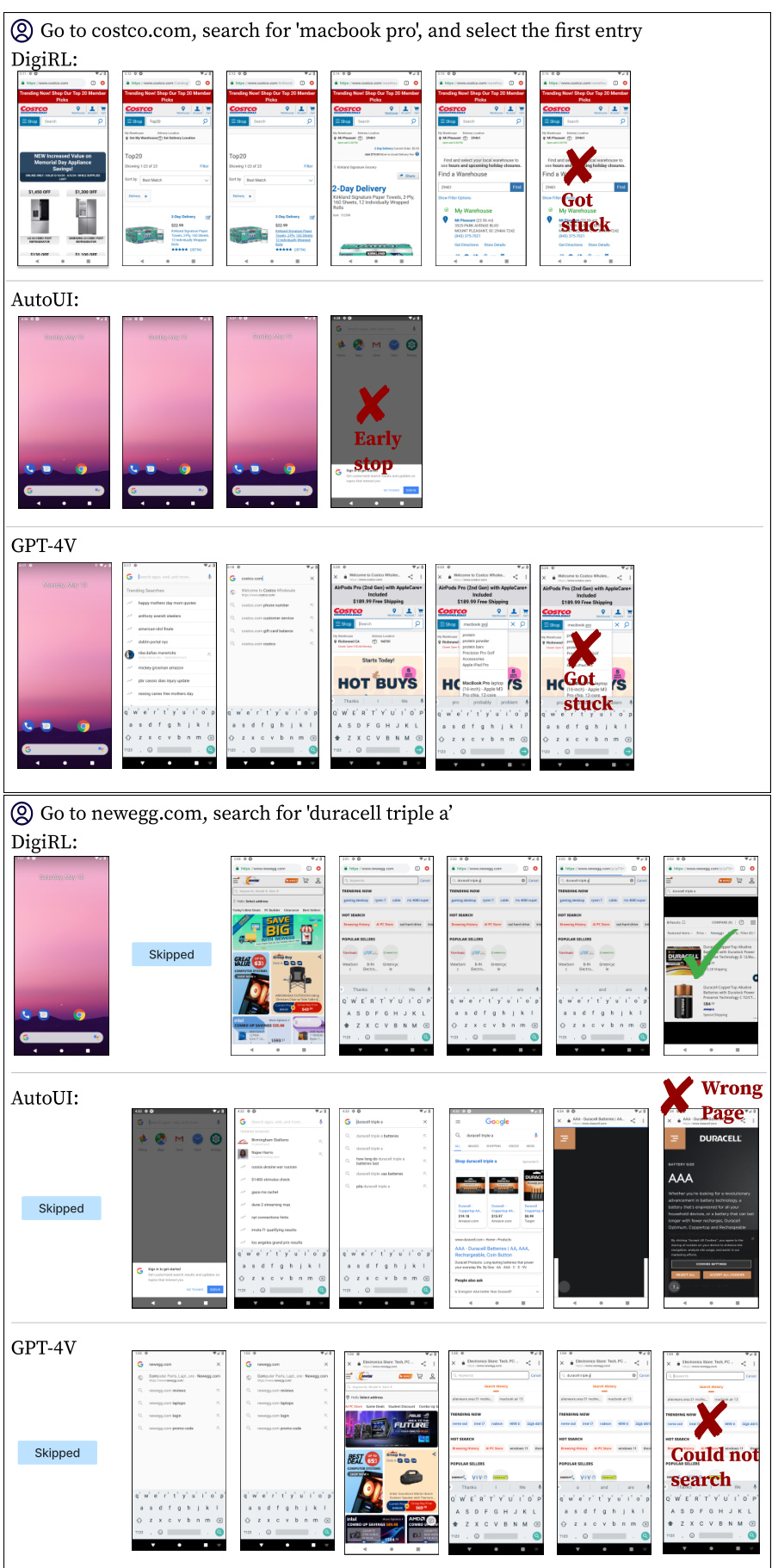

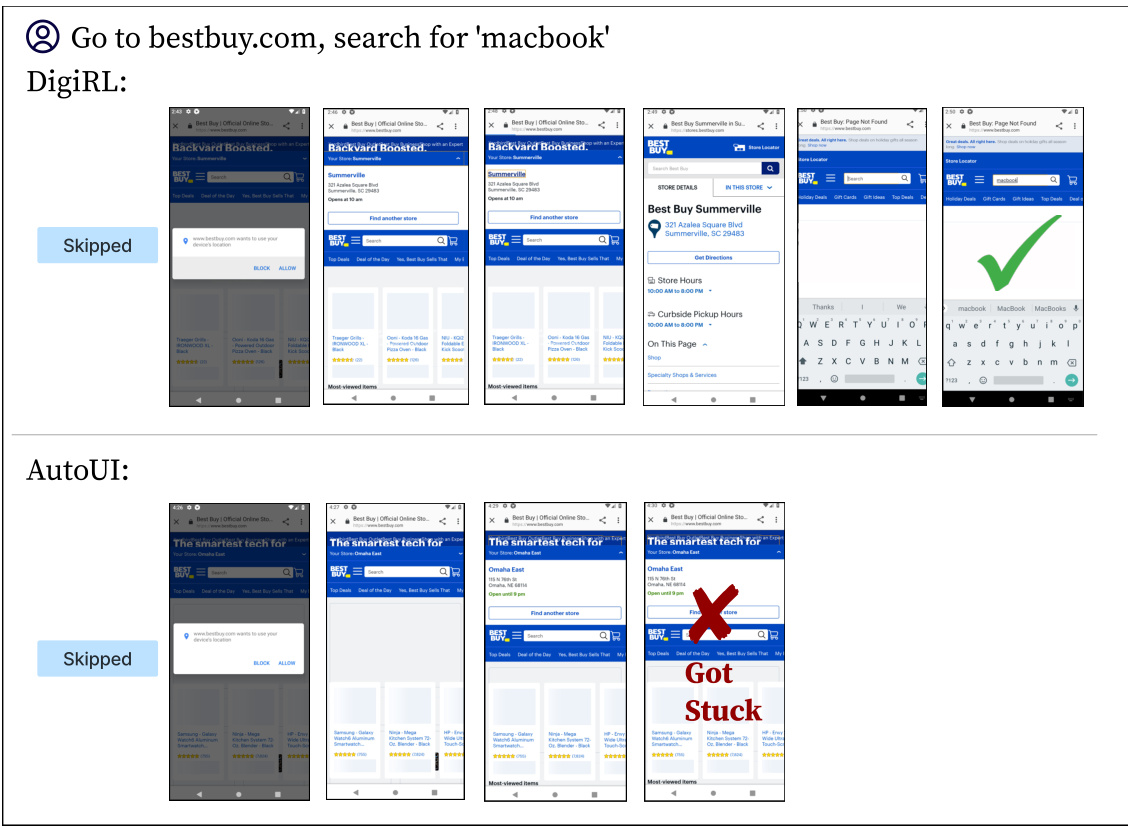

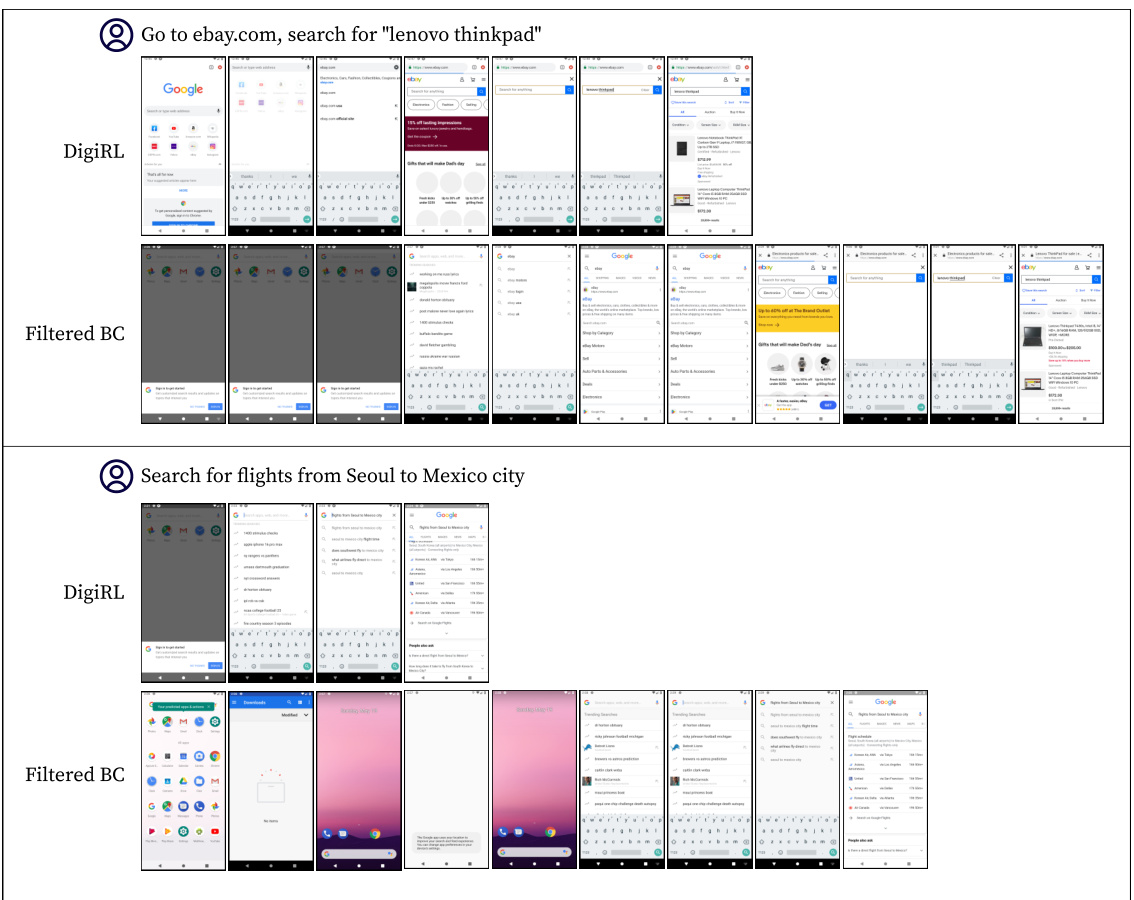

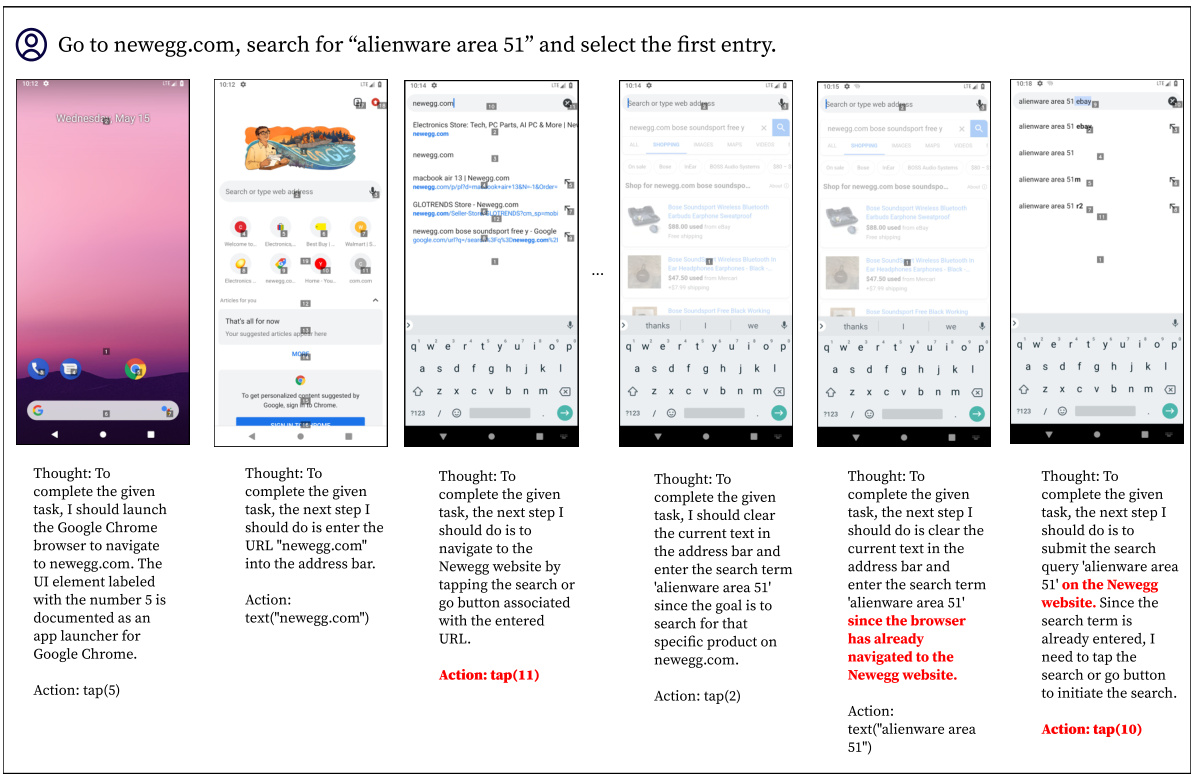

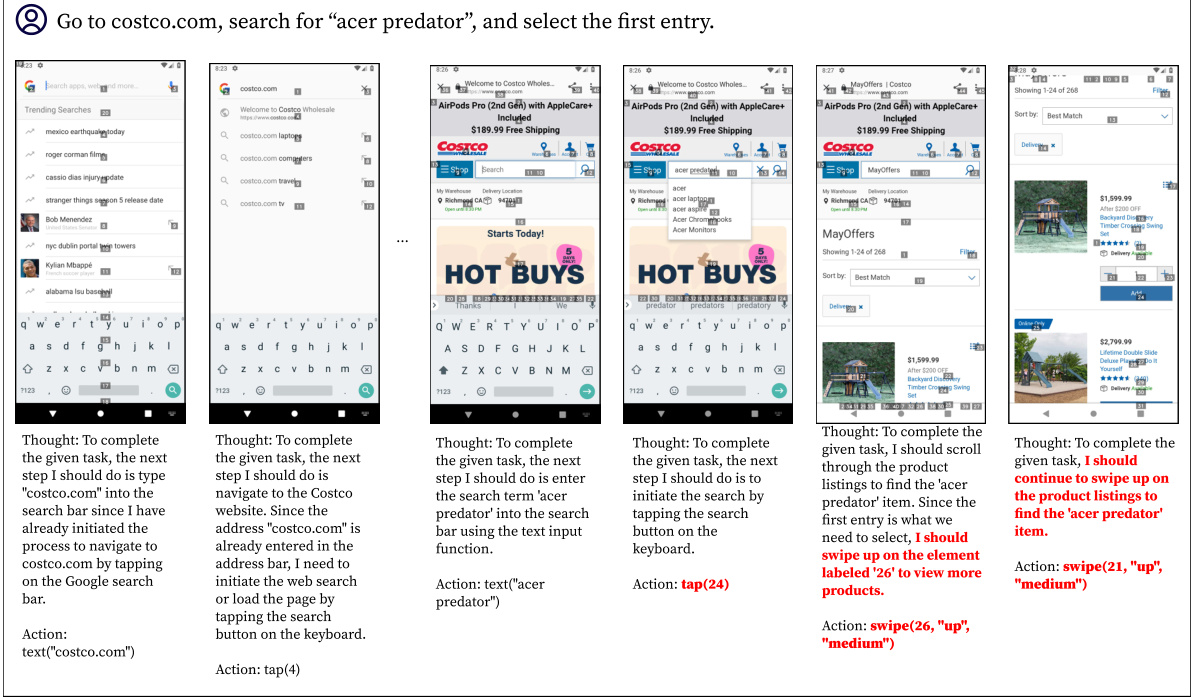

This figure compares the performance of DigiRL, AutoUI, and GPT-4V on two example tasks. AutoUI, trained with static demonstrations, frequently gets stuck in unexpected situations. GPT-4V sometimes pursues the wrong goal, demonstrating a lack of robust reasoning and action selection. In contrast, DigiRL successfully completes both tasks, showcasing its ability to recover from errors and handle unexpected situations.

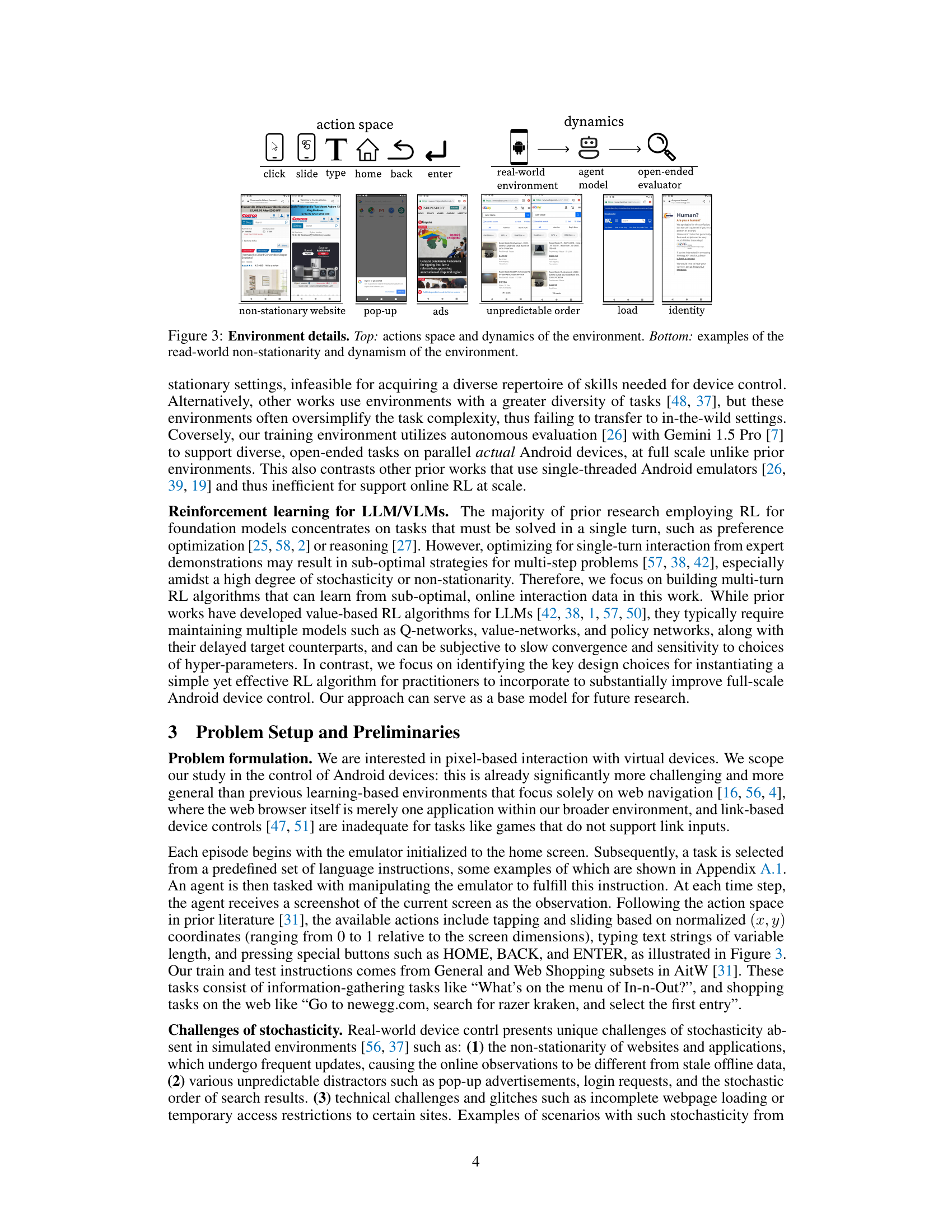

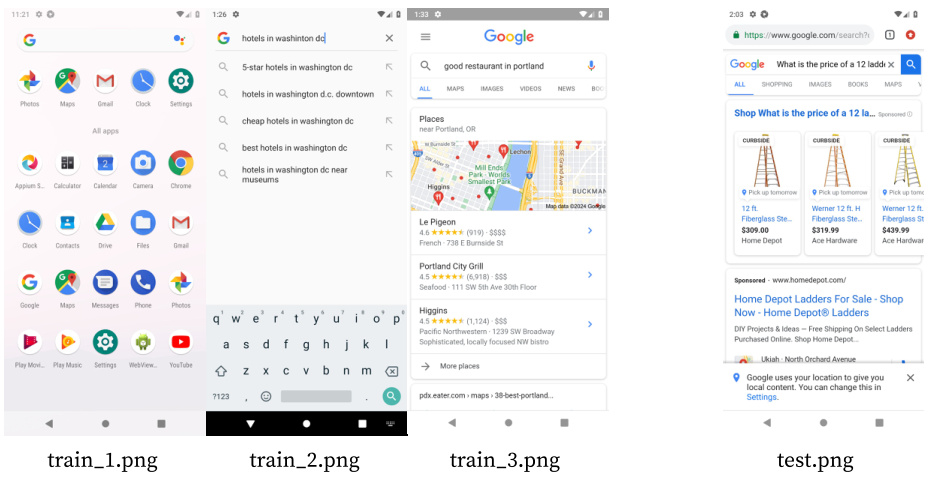

This figure illustrates the environment used for training the digital agents in the DigiRL approach. The top part shows the action space (the actions available to the agent, such as clicking, sliding, typing, and using home, back, or enter buttons) and the dynamics of the environment (how the agent interacts with the real-world environment, a model of the agent, and an open-ended evaluator). The bottom part shows examples of real-world non-stationarity and dynamism, highlighting the challenges encountered such as non-stationary websites (websites that change frequently), pop-ups, ads, unpredictable order of elements on a screen, loading times, and identity checks. These elements contribute to the stochasticity and non-stationarity of the environment which DigiRL aims to address.

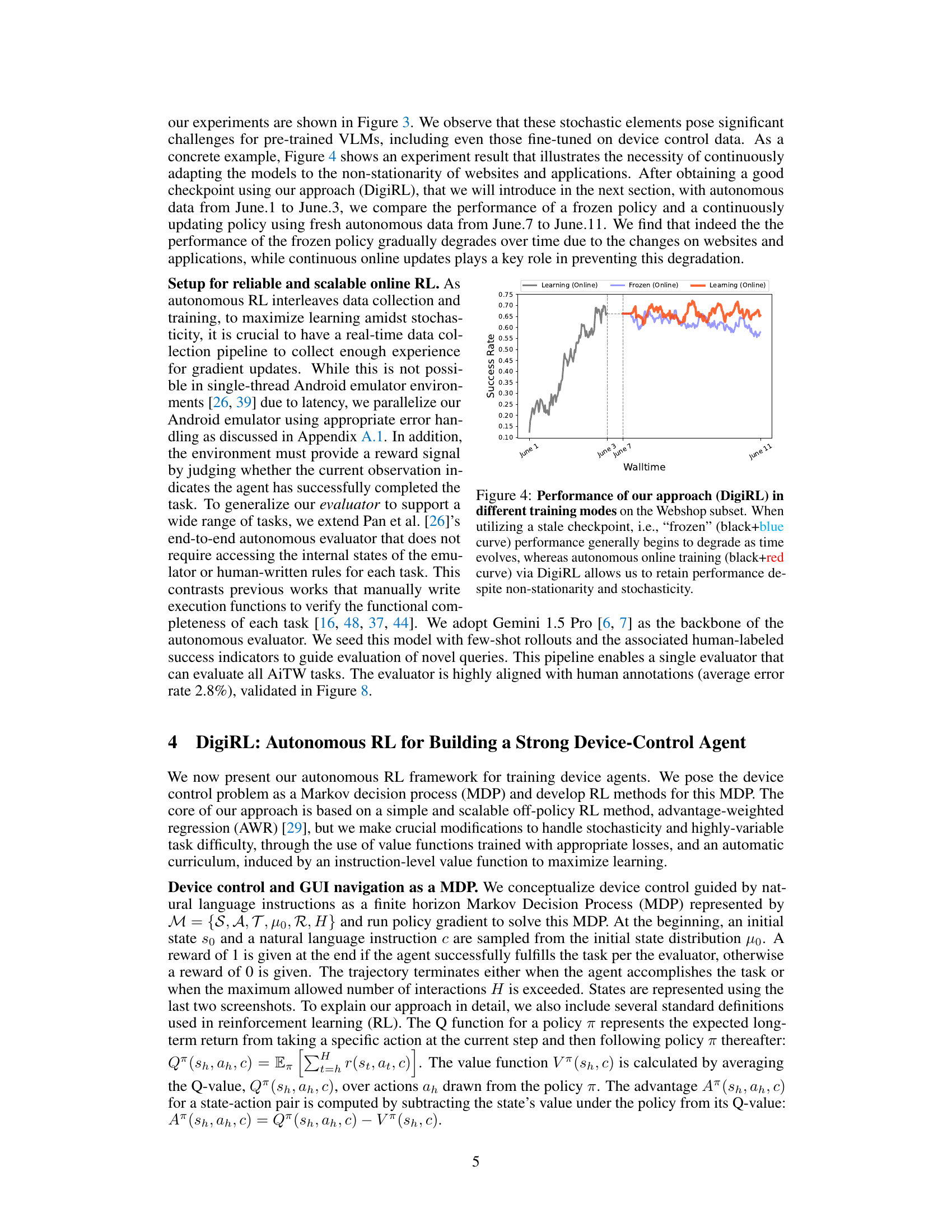

This figure compares the performance of DigiRL in two different training modes on the Webshop subset of the Android in the Wild (AitW) dataset. The ‘Frozen (Online)’ line shows the performance of a model trained using data from June 1-3 and then tested on new data from June 7-11 without further training. The ‘Learning (Online)’ line depicts the performance of a model that continuously updates itself using the newer data. The graph shows that the frozen model’s performance degrades over time while the model that continuously learns maintains its performance, highlighting the importance of continuous online adaptation for dealing with real-world non-stationarity.

This figure illustrates the DigiRL algorithm’s workflow. It starts with two value functions, instruction-level and step-level, trained using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) loss on the collected trajectories. These functions then filter the trajectories, retaining only those deemed most informative. Finally, an actor is trained using MLE loss on this filtered data, leading to a refined agent.

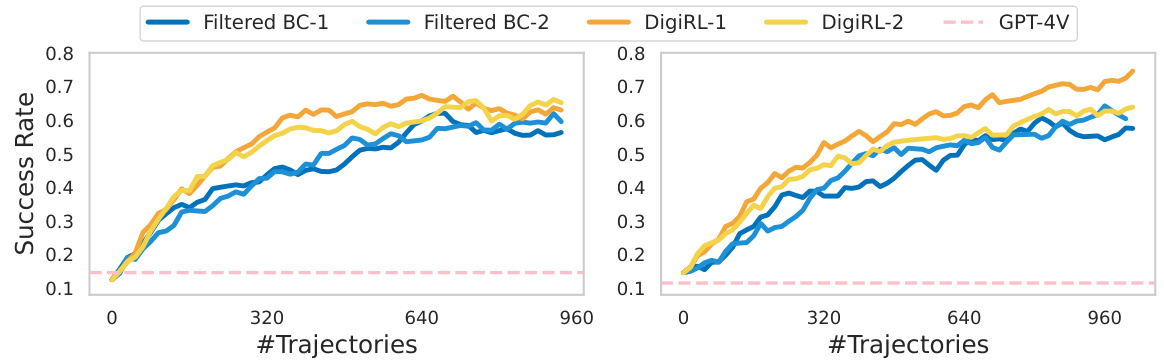

This figure shows the learning curves for Filtered Behavior Cloning (Filtered BC) and DigiRL, comparing their success rates over the number of trajectories. Two runs for each method are included, performed on different dates to account for the dynamic nature of the data. DigiRL demonstrates faster improvement with fewer samples, and this speed advantage is also reflected in wall-clock time due to the data collection bottleneck.

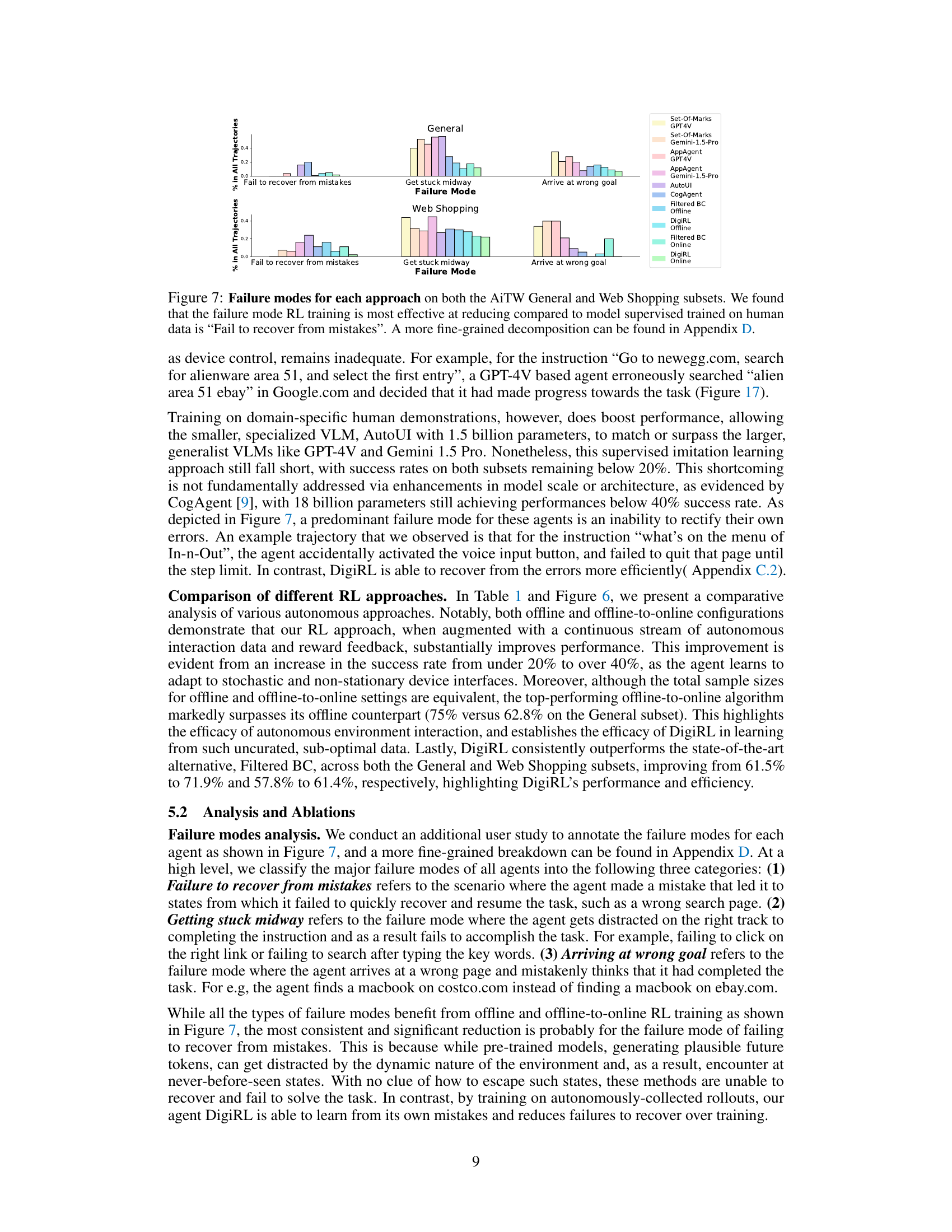

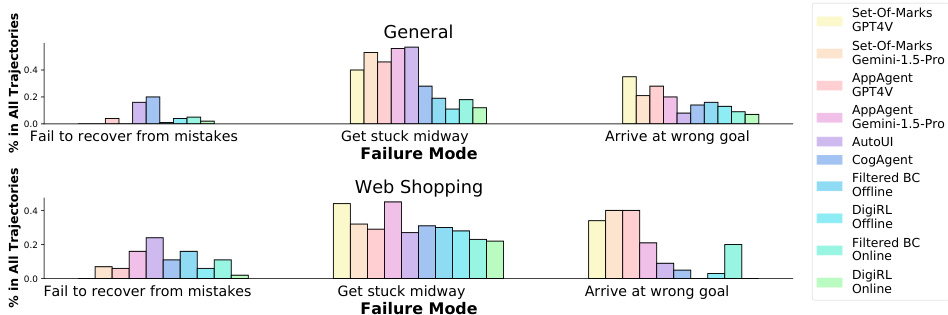

This figure shows a comparison of failure modes across different methods for device control tasks on two subsets of the Android-in-the-Wild (AiTW) dataset: General and Web Shopping. The three main failure modes are categorized: inability to recover from mistakes, getting stuck mid-task, and reaching the wrong goal. The bar chart visually represents the proportion of each failure mode for each method, illustrating DigiRL’s superior performance in reducing failure rates compared to other methods.

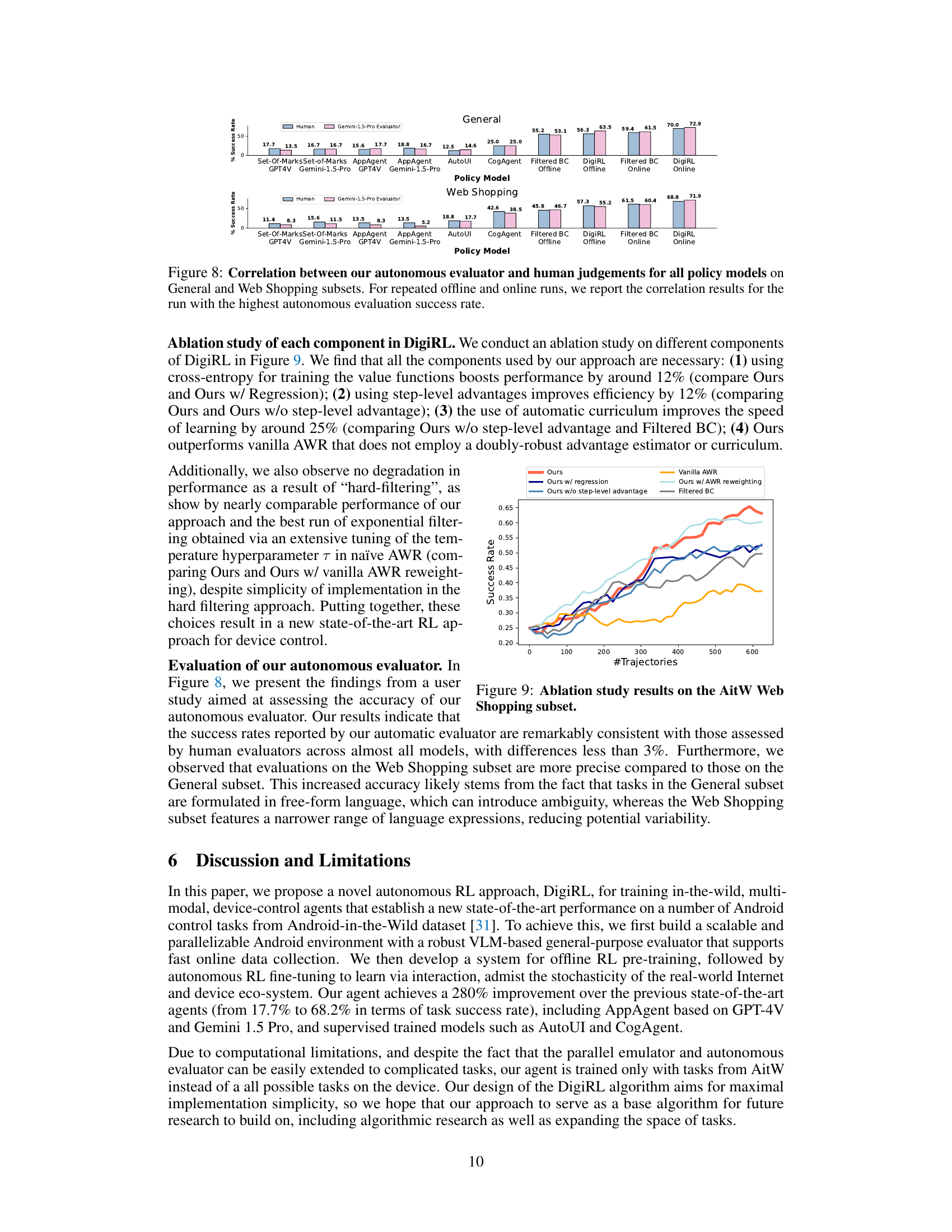

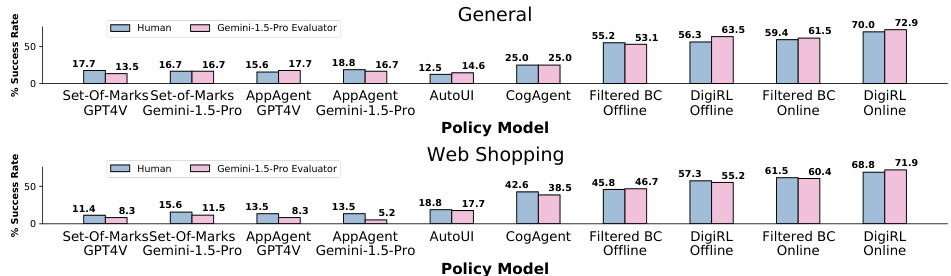

This figure displays bar charts illustrating the correlation between the success rates determined by the autonomous evaluator and human judgements for different policy models (Set-of-Marks GPT-4V, Set-of-Marks Gemini-1.5-Pro, AppAgent GPT-4V, AppAgent Gemini-1.5-Pro, AutoUI, CogAgent, Filtered BC Offline, DigiRL Offline, Filtered BC Online, DigiRL Online). The results are shown separately for the General and Web Shopping subsets of the AiTW dataset. The higher the bars, the stronger the agreement between human and automated evaluation.

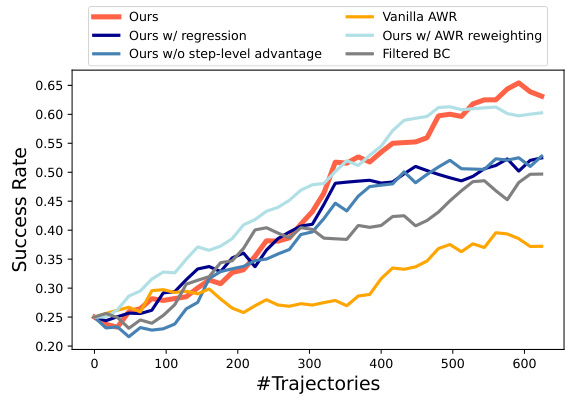

This figure shows the ablation study results on the AitW Web Shopping subset. It compares the performance of DigiRL with several variants, including removing the regression, removing the step-level advantage, using vanilla AWR, and using AWR with reweighting. The x-axis represents the number of trajectories used for training, and the y-axis represents the success rate. The results demonstrate that all components of DigiRL contribute to its superior performance. Specifically, using a cross-entropy loss for value functions and incorporating an automatic curriculum significantly improves the learning efficiency.

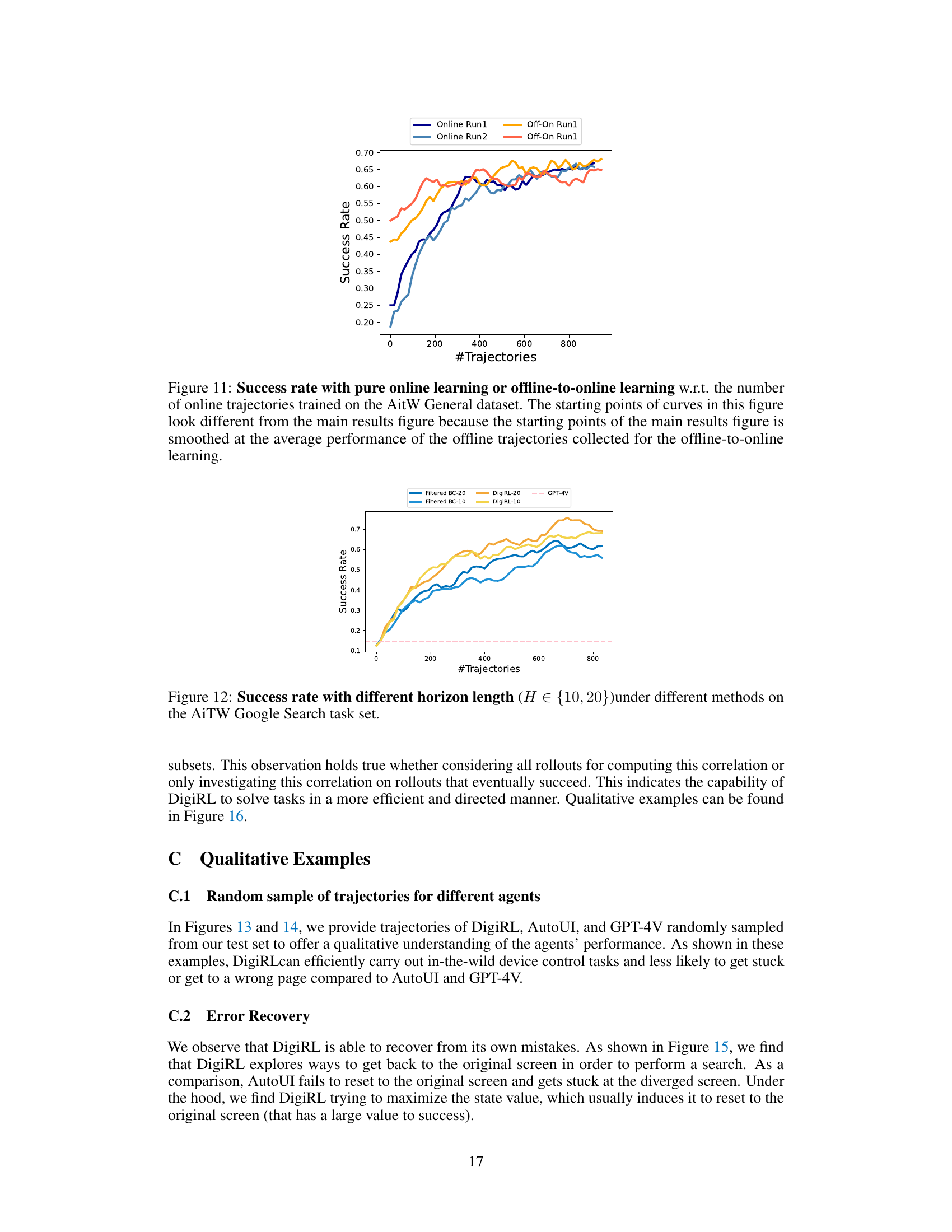

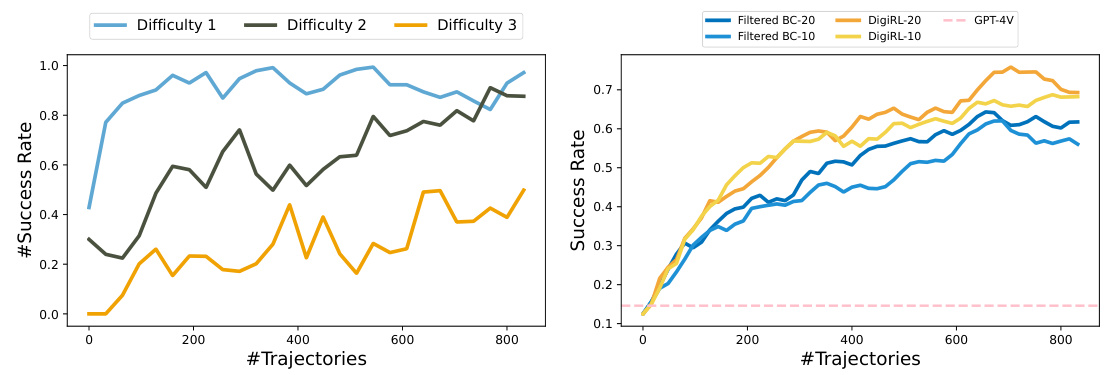

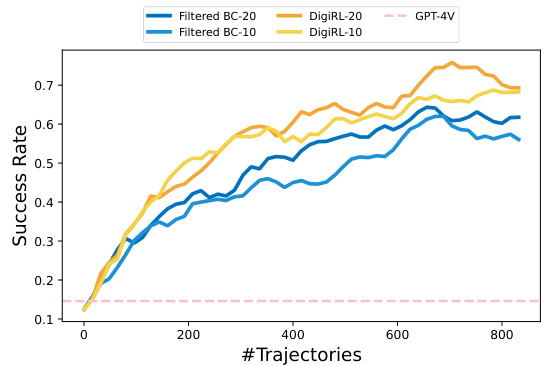

The left plot shows the success rate for tasks of different difficulty levels in the Web Shopping subset of the Android-in-the-Wild (AiTW) dataset. The difficulty is determined by the complexity of the task instructions (see Table 3). The plot illustrates the learning process for the DigiRL model, showing how success rates on easier tasks improve performance on more difficult ones. The right plot compares the learning curves of DigiRL and Filtered Behavior Cloning (Filtered BC) for the Google Search task, varying the maximum number of steps (H) allowed to complete each task (horizon length). The plot demonstrates that DigiRL generally achieves higher success rates than Filtered BC and that increasing the horizon (from 10 to 20) can potentially improve the model’s learning performance. The success rate of GPT-4V is also included as a baseline for comparison.

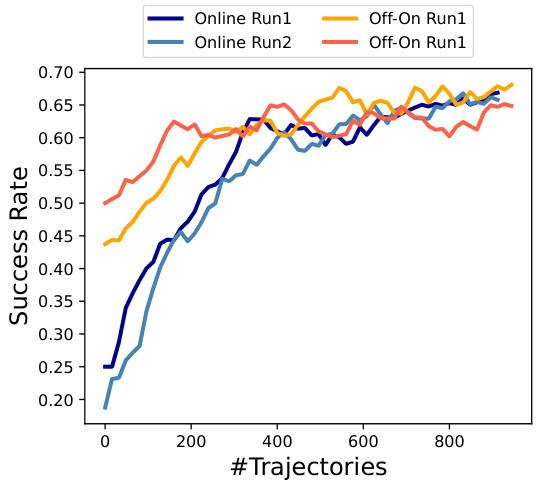

This figure compares the success rate of two training methods: pure online learning and offline-to-online learning, on the AitW General dataset. The offline-to-online approach starts with some pre-trained data from offline RL, and then fine-tunes the model with online data. The pure online approach trains the model only on online data. The x-axis represents the number of online trajectories used for training and the y-axis represents the success rate. The figure shows that offline-to-online learning converges faster, achieving a higher success rate with fewer trajectories, though the final success rates of both methods are comparable.

This figure compares the offline-to-online learning curves of DigiRL and Filtered BC on two subsets of the Android-in-the-Wild (AiTW) dataset: General and Web Shopping. The x-axis represents the number of trajectories used for training, while the y-axis shows the success rate. The curves are smoothed to highlight trends. DigiRL demonstrates faster improvement with fewer samples than Filtered BC, likely due to its more efficient learning strategy and ability to adapt to the changing nature of the environment. The data collection frequency is the limiting factor, so the learning curves reflect the wall-clock training time.

This figure shows the qualitative comparison of DigiRL, AutoUI, and GPT-4V on two randomly sampled tasks from the General split of the Android-in-the-Wild (AitW) dataset. It visually demonstrates the differences in how each agent approaches and completes the tasks. DigiRL showcases a more robust and successful approach compared to AutoUI and GPT-4V, which encounter issues like getting stuck or arriving at the wrong goal.

This figure shows example trajectories of DigiRL, AutoUI, and GPT-4V on two randomly selected tasks from the General subset of the Android-in-the-Wild (AiTW) dataset. The figure qualitatively demonstrates the differences in the agents’ abilities to perform device control tasks. DigiRL showcases efficient and effective task completion, while AutoUI and GPT-4V encounter difficulties such as getting stuck or reaching an incorrect destination.

This figure shows two examples of agent’s trajectories on the General split of the Android-in-the-Wild (AiTW) dataset. The top example shows the trajectory for the task ‘What are the new products by Samsung?’, and the bottom example shows the trajectory for the task ‘Show me some nice wallpapers for my tablet’. Each row represents the trajectory of a different agent: DigiRL, AutoUI, and GPT-4V. The screenshots in each row illustrate the sequence of actions taken by the agent. The figure highlights the differences in how each agent approaches the task, demonstrating the superior ability of DigiRL to complete these tasks without getting stuck or making significant errors compared to AutoUI and GPT-4V.

This figure provides a visual comparison of the trajectory lengths (number of steps) between DigiRL and filtered BC for two sample tasks from the Android in the Wild (AiTW) dataset. It shows that DigiRL consistently requires fewer steps to complete the tasks compared to filtered BC, highlighting the efficiency improvement achieved by DigiRL.

This figure illustrates the DigiRL architecture, a two-stage training process for a Vision-Language Model (VLM)-based agent. Stage 1 involves offline reinforcement learning (RL) to fine-tune the pre-trained VLM using existing trajectory data, which helps the agent learn to exhibit goal-oriented behaviors. In Stage 2, offline-to-online RL is employed, where the agent interacts with real-world graphical user interfaces (GUIs). The agent’s performance is continuously improved through online RL using feedback from an autonomous evaluation system. This system assesses the agent’s actions and provides reward signals based on whether the tasks were successfully completed.

This figure presents an overview of the DigiRL approach. It begins with a pre-trained vision-language model (VLM) that is further fine-tuned using offline reinforcement learning (RL) on existing trajectory data. This offline stage aims to establish basic goal-oriented behavior. The second stage involves online RL where the agent interacts with real-world graphical user interfaces (GUIs), continuously learning and improving its performance through autonomous evaluation of its actions. The figure visually depicts the two-stage process, highlighting the use of offline and online RL, the integration of a VLM-based evaluator, and the iterative refinement of the agent’s performance.

This figure shows two example tasks from the General subset of the Android-in-the-Wild (AiTW) dataset. For each task, it displays the sequences of screenshots showing the agent’s actions for three different approaches: DigiRL, AutoUI, and GPT-4V. The figure visually demonstrates the differences in how these agents approach and complete (or fail to complete) the tasks, highlighting DigiRL’s superior performance and ability to handle complex instructions and recover from mistakes, unlike the other agents.

This figure presents the correlation between the results from the autonomous evaluator and human evaluations across various policy models for both the General and Web Shopping subsets of the dataset. The plot shows how well the automated assessment aligns with human judgement on the success rate of different agents. Repeated offline and online experiments were conducted, and the correlation for the run with the best evaluation score is reported.

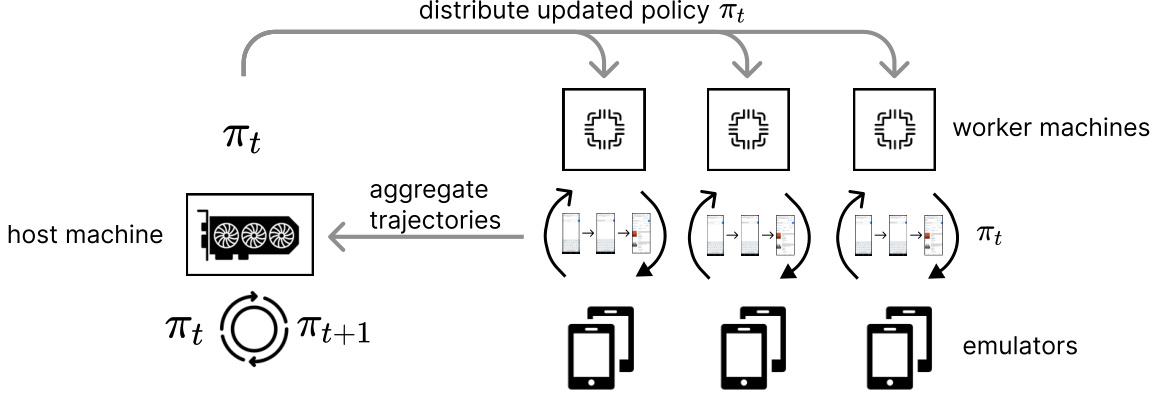

This figure illustrates the parallel computing architecture used for training the DigiRL agent. A host machine with GPUs handles the policy updates, while multiple worker machines with CPUs concurrently run Android emulators. Each worker machine independently collects trajectories, which are then aggregated by the host machine for efficient model training. This distributed approach scales training to a larger number of emulators and speeds up the overall process.

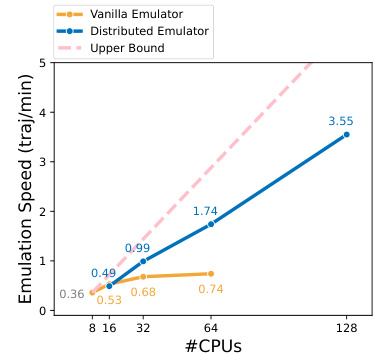

This figure shows the emulation speed comparison between the vanilla emulator and the distributed emulator with respect to the number of CPUs used. The upper bound represents the ideal scenario without communication and error handling overhead. The results demonstrate that the distributed emulator design significantly improves the emulation efficiency compared to the vanilla approach, especially as the number of CPUs increases.

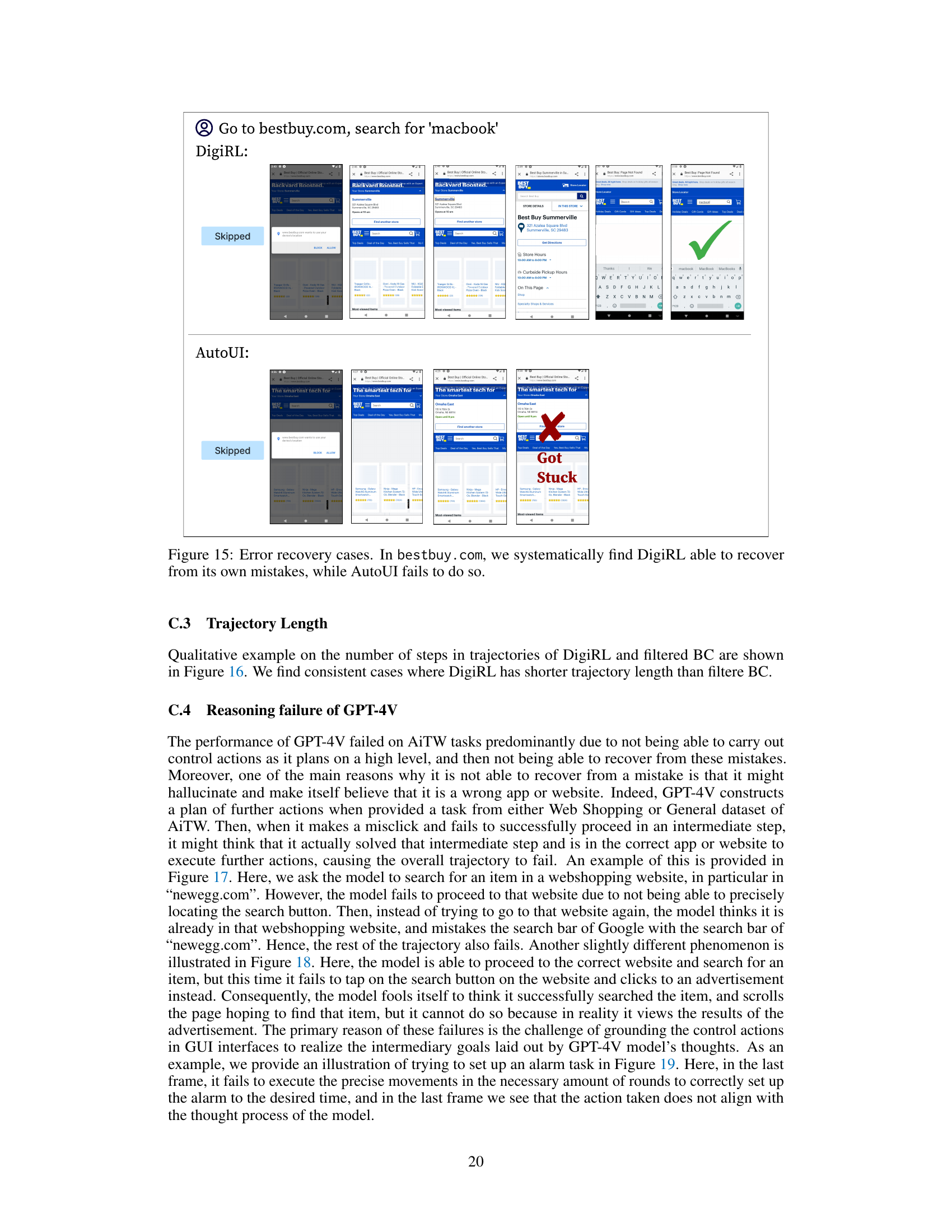

This figure compares the performance of DigiRL with AutoUI and GPT-4V on two example tasks. AutoUI, trained with static demonstrations, struggles with out-of-distribution scenarios, frequently getting stuck. GPT-4V, despite its strong capabilities, sometimes focuses on the wrong goal, as seen in the example task where it incorrectly searches on Google instead of BestBuy. In contrast, DigiRL demonstrates its robustness by successfully completing the tasks, showcasing its ability to adapt to real-world stochasticity and recover from mistakes.

This figure qualitatively compares DigiRL’s performance against AutoUI and GPT-4V on two example tasks. AutoUI, trained with static demonstrations, frequently gets stuck in unexpected situations (out-of-distribution states). GPT-4V, while capable of abstract reasoning, often fails to translate this into correct actions, taking the user down an incorrect path. In contrast, DigiRL successfully completes both tasks and demonstrates its ability to recover from errors and handle real-world stochasticity.

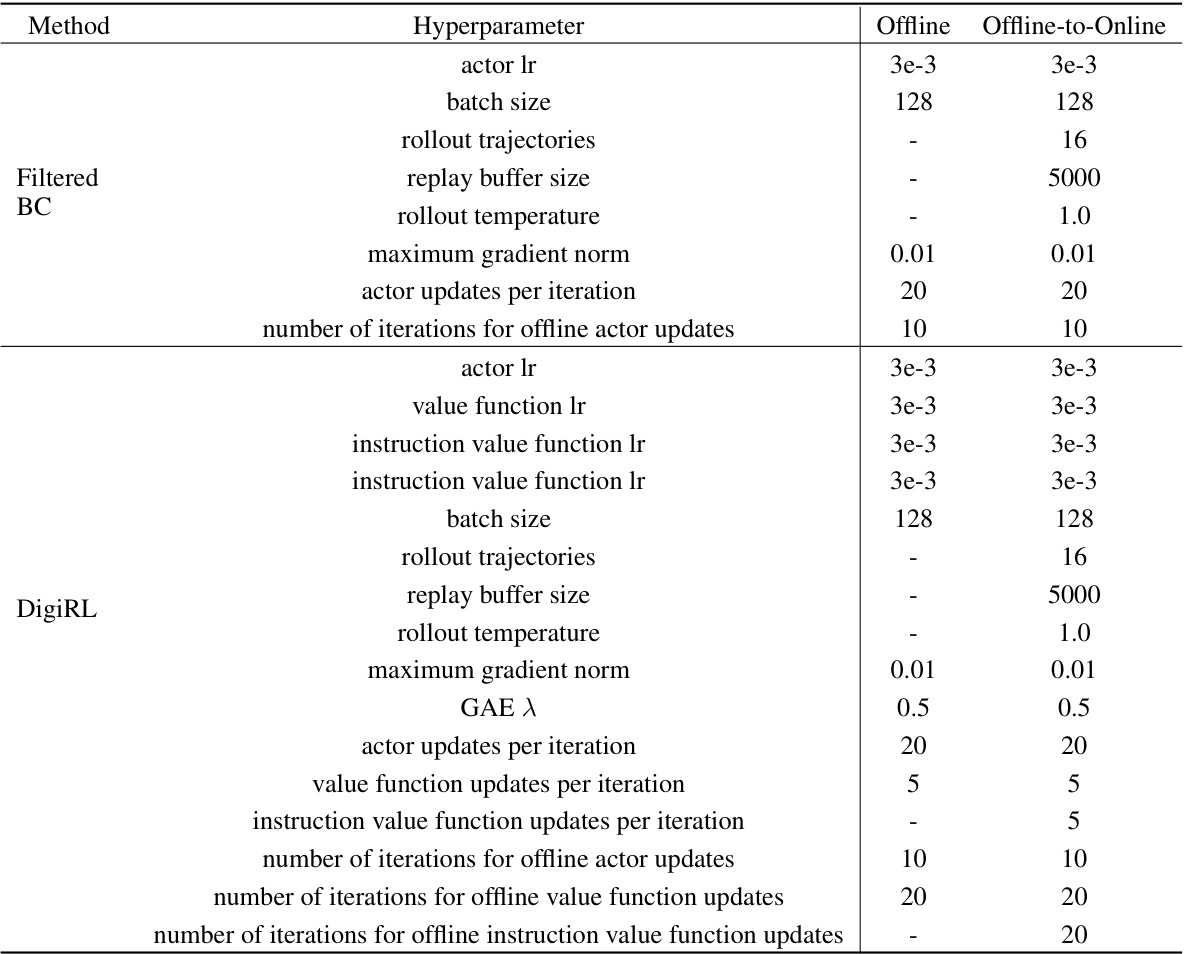

More on tables

This table compares the performance of DigiRL against several other approaches on two subsets of the Android-in-the-Wild dataset (AitW). It shows the success rates (train and test) for different agents categorized by their training method (prompting, supervised training, offline RL, and offline-to-online RL). The agents include those based on proprietary VLMs (GPT-4V, Gemini), imitation learning (CogAgent, AutoUI), and prior autonomous RL (Filtered BC). The table highlights DigiRL’s superior performance, significantly surpassing all other methods. Note that the evaluation is based on the first 96 instructions in both training and test datasets.

This table compares the performance of DigiRL against several baseline methods on two subsets of the Android-in-the-Wild (AiTW) dataset: General and Web Shopping. The baselines include methods using prompting and retrieval with proprietary VLMs (GPT-4V, Gemini), supervised training on static demonstrations (CogAgent, AutoUI), and a prior autonomous RL approach (Filtered BC). The table shows the success rates (train and test) for each method, highlighting DigiRL’s significant improvement over the state-of-the-art.

This table compares the average rollout length of the DigiRL agent and the Filtered BC agent on two subsets of the Android-in-the-Wild (AitW) dataset: General and Web Shopping. The rollout length represents the number of steps taken by the agent to complete a task. Shorter rollout lengths indicate greater efficiency. The table shows that DigiRL consistently achieves shorter rollout lengths than Filtered BC on both subsets.

This table compares the performance of DigiRL against several baseline methods across two subsets of the Android-in-the-Wild (AiTW) dataset: General and Web Shopping. The baselines include approaches using prompting and retrieval with proprietary VLMs (GPT-4V and Gemini 1.5 Pro), supervised training methods (CogAgent and AutoUI), and a Filtered Behavior Cloning (Filtered BC) method. The table shows the success rates on both training and test sets for each method, highlighting the significant improvement achieved by DigiRL (Ours) in both offline and offline-to-online settings. The results demonstrate DigiRL’s superior performance in comparison to existing state-of-the-art approaches.

This table compares the performance of DigiRL against other state-of-the-art methods for Android device control, including methods based on prompting and retrieval (AppAgent + GPT-4V/Gemini 1.5 Pro), supervised training (CogAgent and AutoUI), and filtered behavior cloning (Filtered BC). The results show that DigiRL significantly outperforms all of these methods in terms of success rate on both the AitW General and AitW Web Shopping subsets. The table also breaks down the results by training type (offline, offline-to-online), highlighting the effectiveness of DigiRL’s autonomous learning approach.

Full paper#