↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Diffusion models excel in image generation but lack precise control over image editing. Existing methods often require additional training or lack clear mathematical interpretations. This paper addresses these limitations by exploring the semantic spaces within diffusion models. It reveals that within certain noise levels, the learned posterior mean predictor exhibits local linearity, and its singular vectors reside in low-dimensional semantic subspaces.

The paper proposes LOCO Edit, an unsupervised, single-step, and training-free method for precise local image editing. LOCO Edit identifies editing directions with beneficial properties, significantly improving the effectiveness and efficiency of local image editing. These improvements stem from leveraging the identified low-dimensional semantic subspaces, leading to better homogeneity, transferability, and composability. Extensive experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of LOCO Edit across various datasets and models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in image generation and editing because it offers a novel, unsupervised, and single-step method for precise image manipulation. It provides a theoretical framework and empirical evidence, which improves understanding of diffusion model semantic spaces. This opens new avenues for controllable image editing and related applications.

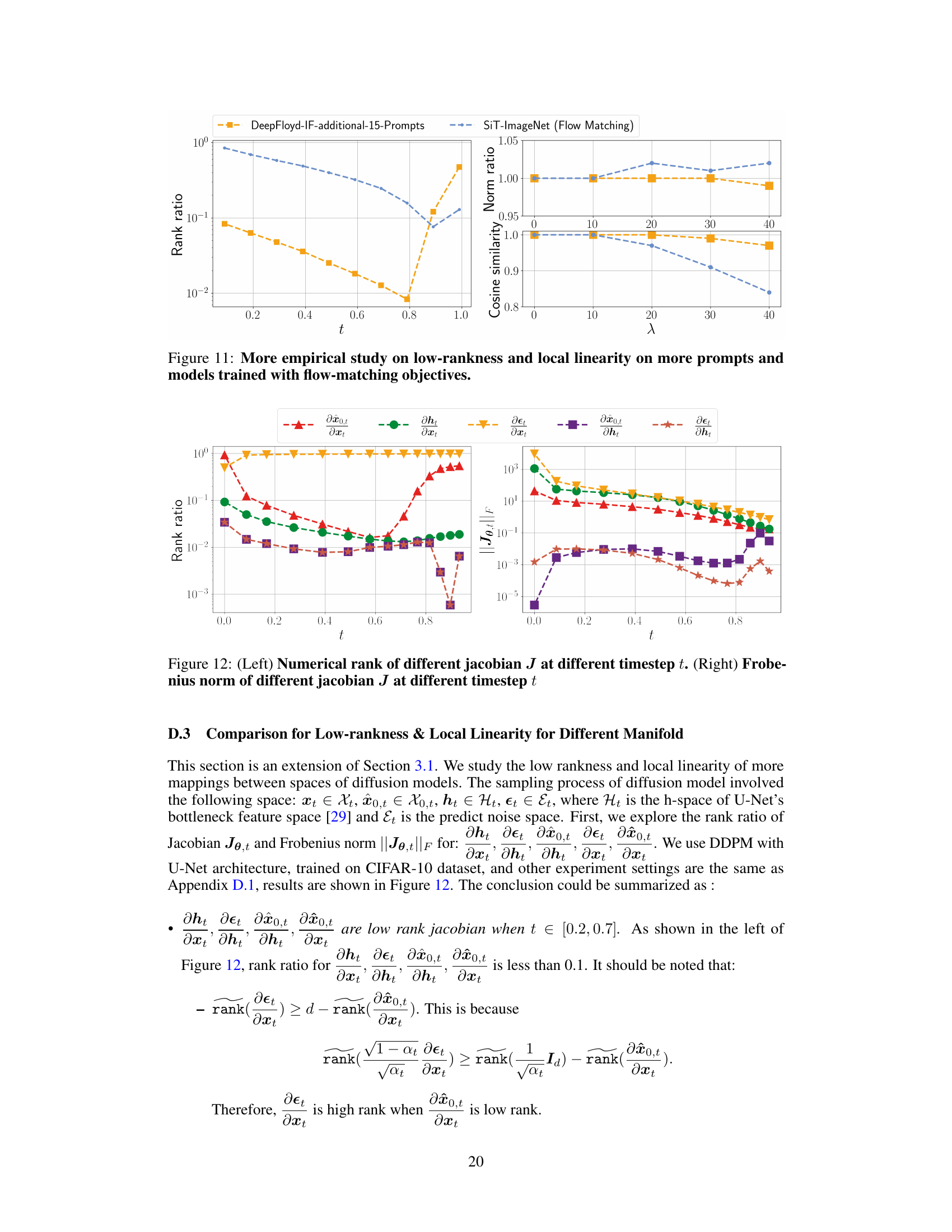

Visual Insights#

This figure demonstrates the capabilities of LOCO Edit, a novel image editing method. Panel (a) showcases its ability to perform precise and localized edits. Panels (b), (c), and (d) highlight additional properties of the editing directions identified by LOCO Edit: homogeneity and transferability across different images and noise levels (b), composability of multiple edits (c), and linearity in the editing direction, meaning proportional changes in a feature with proportional changes in the editing direction (d).

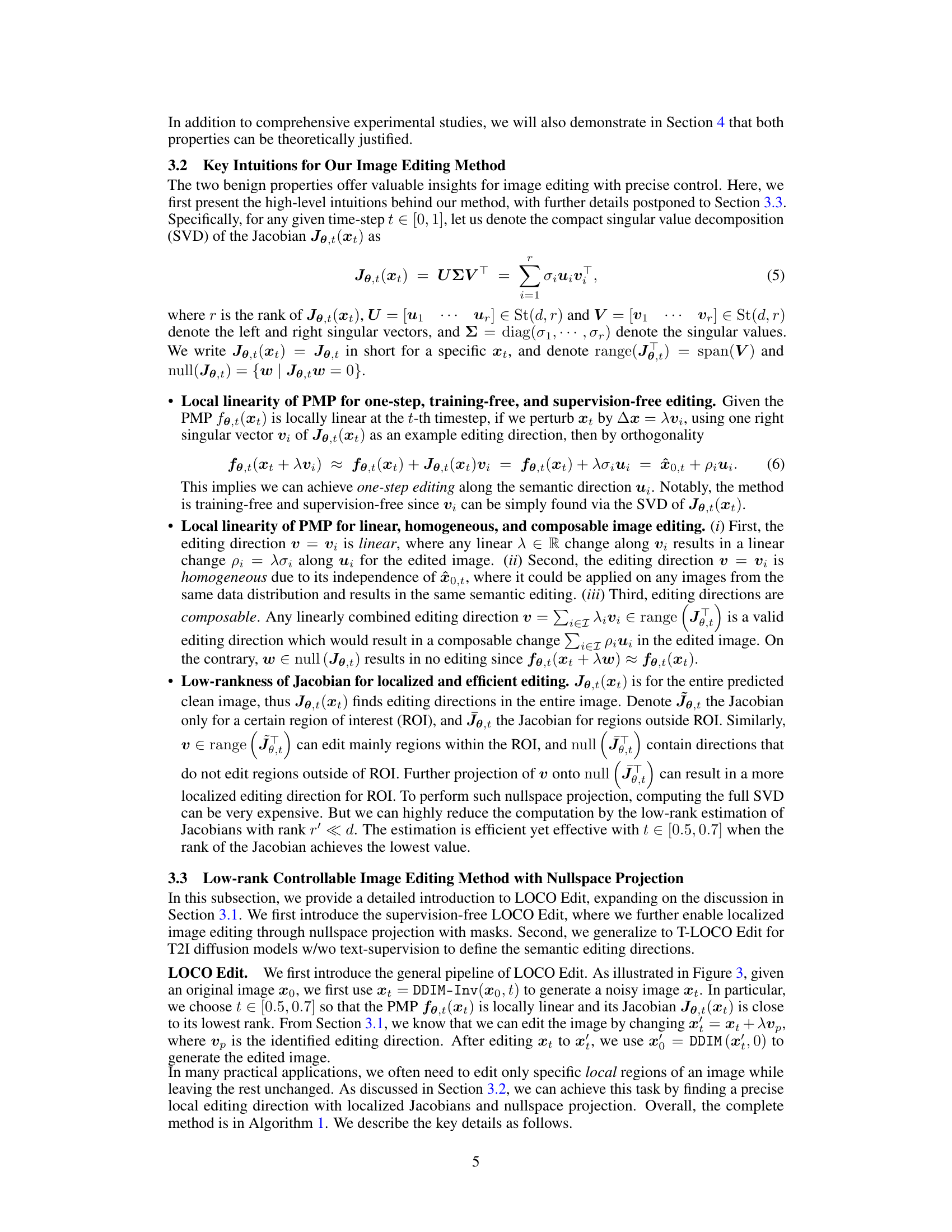

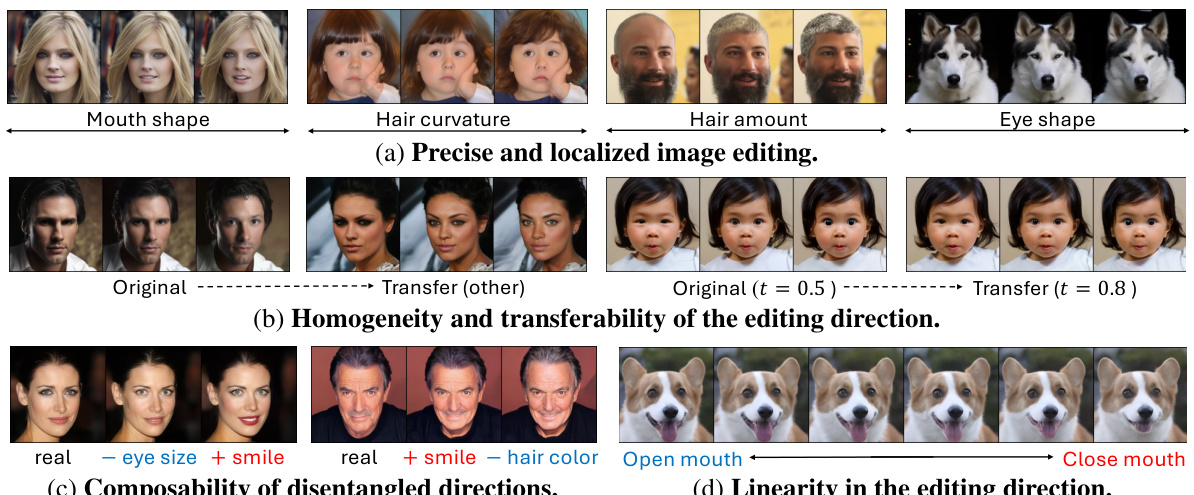

This table compares the proposed LOCO Edit method with other state-of-the-art image editing techniques. The comparison focuses on several key aspects: the success rate of localized editing, the preservation of image quality (measured by LPIPS and SSIM), the ability to transfer the editing style to new images, computational efficiency (learning time and transfer edit time), and the need for training data or supervision. It highlights that LOCO Edit is superior in terms of localized editing success and transferability while being significantly more efficient and training-free. The table also emphasizes LOCO Edit’s unique properties: being a one-step method, requiring no additional supervision, and having a strong theoretical foundation.

In-depth insights#

LocoEdit: Method#

LocoEdit is a novel, single-step, training-free method for controllable image editing within diffusion models. It leverages the observation that the posterior mean predictor (PMP) in diffusion models exhibits local linearity and low-rankness within a specific noise level range. This low-rank property allows the identification of low-dimensional semantic subspaces, enabling precise control over image editing. LocoEdit efficiently computes editing directions using the generalized power method and can perform both precise localized edits via nullspace projection and composable edits by combining disentangled directions. The method’s unsupervised nature and lack of need for additional training or text supervision are key advantages. Its effectiveness is demonstrated through extensive experiments showcasing precise localized edits across various datasets and diffusion model architectures, highlighting its efficiency, homogeneity, and transferability. Theoretical justifications further support its effectiveness, providing a robust framework for controllable image editing within the complex landscape of diffusion models.

Linearity of PMP#

The concept of ‘Linearity of PMP’ within the context of diffusion models for image editing is crucial for understanding how these models function. The Posterior Mean Predictor (PMP) maps noisy images to clean images, and its linearity implies a simplified relationship. Locally, the PMP acts as a linear transformation, allowing straightforward manipulations of the image through linear combinations of singular vectors. This linearity greatly simplifies the process of image editing, enabling precise local modifications without the need for complex, iterative, or training-based methods. The low-dimensionality of the singular vectors further implies that significant changes in image features can be accomplished via edits in a relatively low-dimensional space. This makes the editing process computationally efficient and facilitates disentangled manipulation of semantic features. However, it’s important to note that this linearity is local, implying limitations in scope and generalization to arbitrarily large edits or transformations.

Low-Dim Subspaces#

The concept of ‘Low-Dimensional Subspaces’ in the context of diffusion models for image editing is a powerful idea. It suggests that the seemingly high-dimensional space of images can be effectively manipulated by focusing on lower-dimensional structures that capture significant semantic variations. These subspaces act like latent codes, encoding meaningful changes (e.g., altering hair color, changing facial expressions) which are disentangled and easily controllable. By operating within these low-dimensional regions, computationally expensive global manipulations can be avoided, leading to efficient and precise editing. The local linearity of the posterior mean predictor (PMP) further supports this concept, simplifying the process of finding and utilizing these subspaces. A theoretical understanding of why these subspaces emerge is also crucial, offering a more rigorous foundation than heuristic methods. The effectiveness of using low-dimensional subspaces for image editing relies on the validity of the underlying assumptions and the ability to effectively identify these subspaces in practice.

Future Directions#

The ‘Future Directions’ section of a research paper on controllable image editing using diffusion models would ideally explore several key areas. Extending the theoretical framework to encompass text-supervised editing is crucial, requiring a deeper geometric analysis of how semantic subspaces interact under different text prompts. This would also necessitate exploring more efficient fine-tuning techniques for better control and higher-quality outputs. Another important direction involves investigating the application of the proposed methods to different model architectures, such as transformer-based diffusion models, to determine the universality of the findings. Furthermore, research could focus on combining coarse-to-fine editing, potentially across multiple time steps to enhance precision and flexibility. Finally, exploring the connection between the low-rank structures discovered in this work and other areas of image and video representation learning could reveal valuable insights into the broader field of generative models. Expanding into 3D image and video editing, leveraging the low-rank subspaces for pose or shape manipulation, would be another significant advancement.

Limitations#

A thoughtful discussion on limitations within a research paper should delve into the scope and boundaries of the study. It should acknowledge any methodological shortcomings, such as limitations in data collection, sample size, or the generalizability of findings. It is also important to address any uncertainties or assumptions that influenced the research design or analysis. For instance, were there specific parameters or constraints that affected the ability to explore certain avenues of investigation? What were the trade-offs made between feasibility and rigor? A comprehensive limitations section also highlights any potential biases that could have influenced the interpretation of results. Future research directions stemming from these limitations can be suggested, providing a clear path towards enhancing the work and addressing the identified gaps.

More visual insights#

More on figures

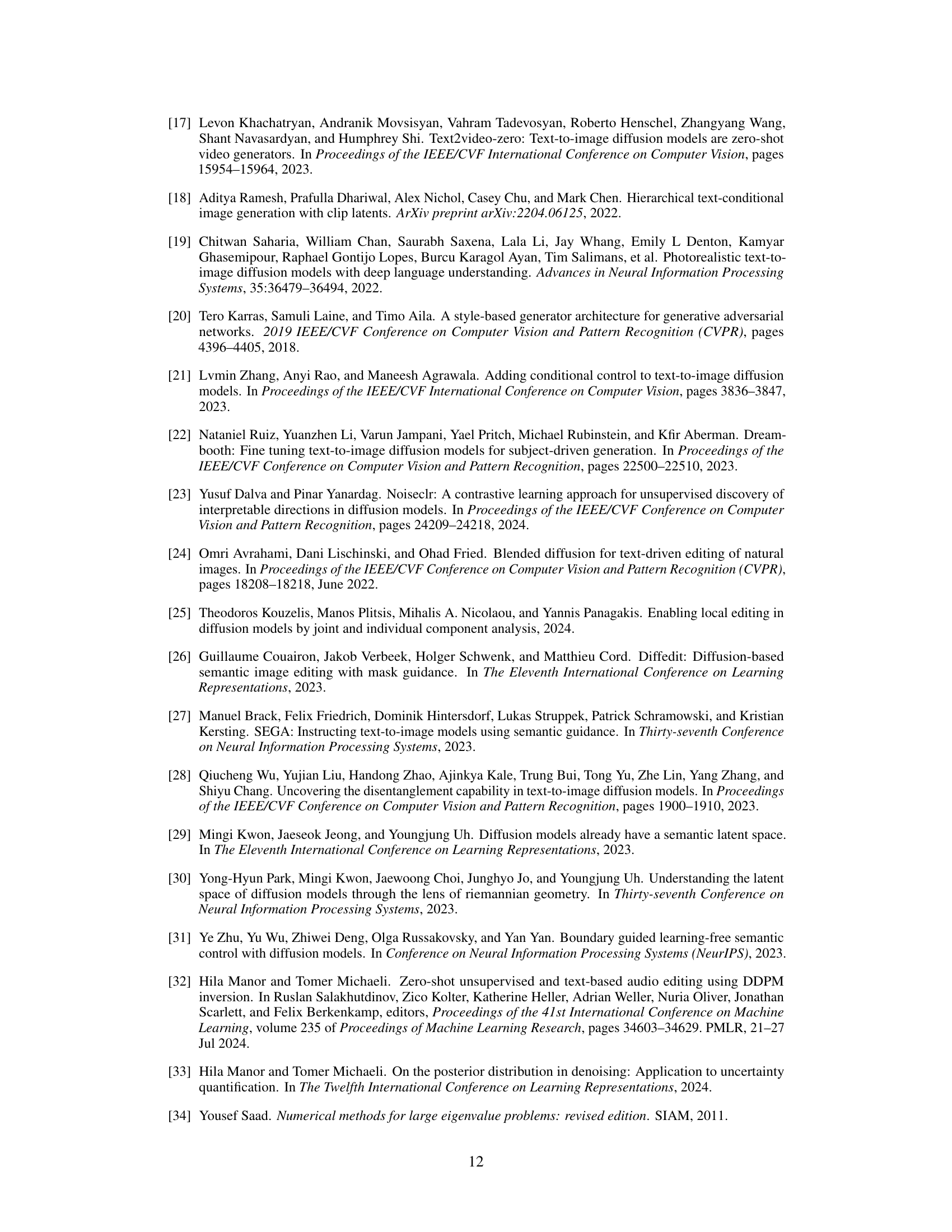

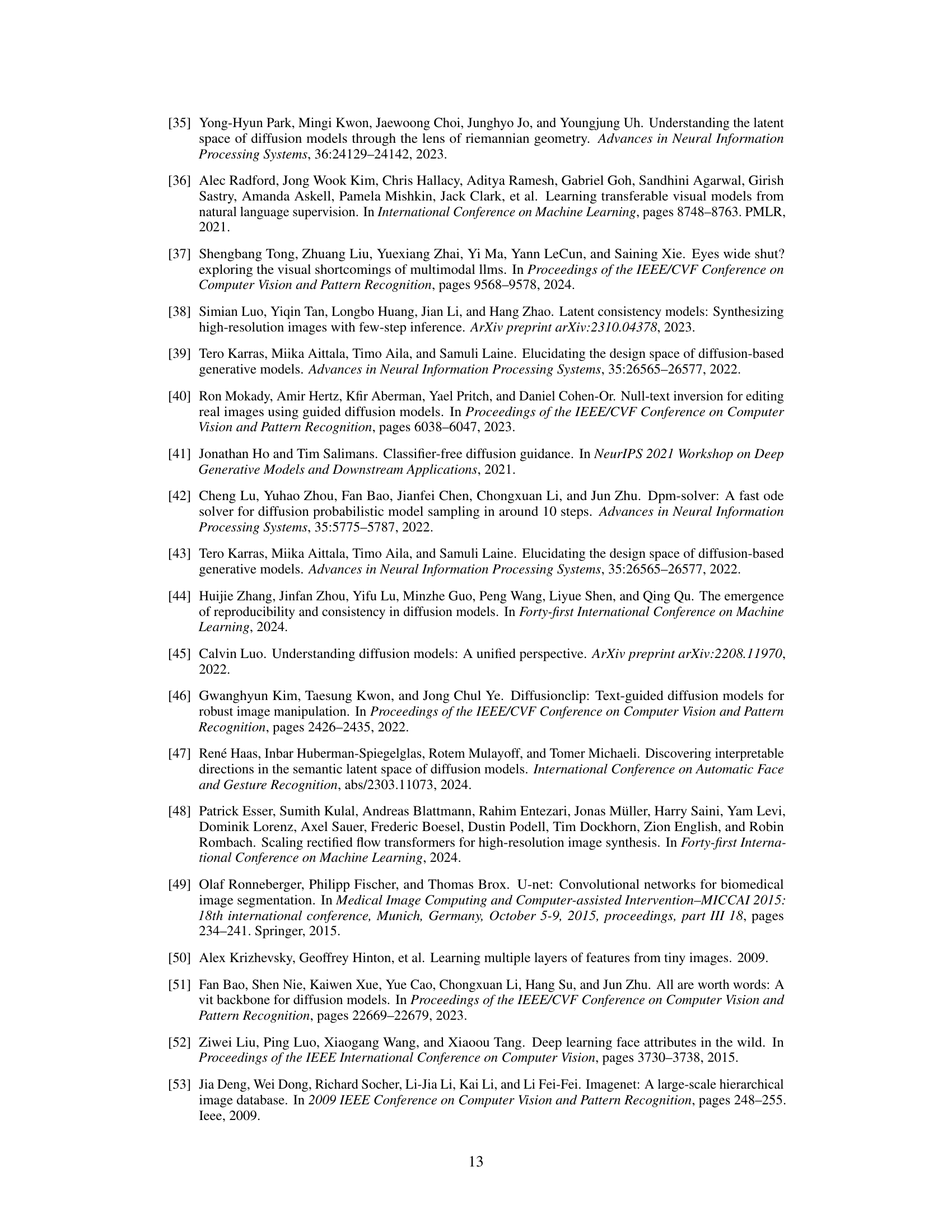

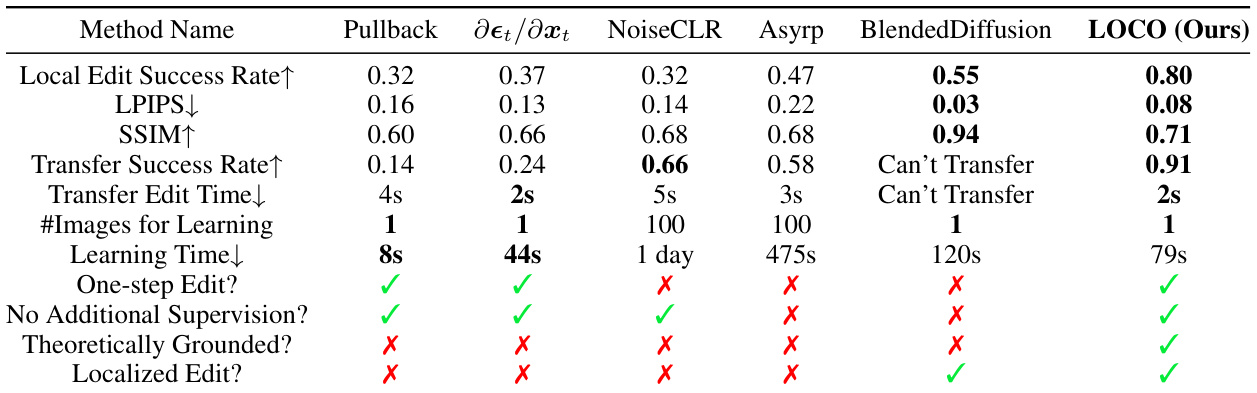

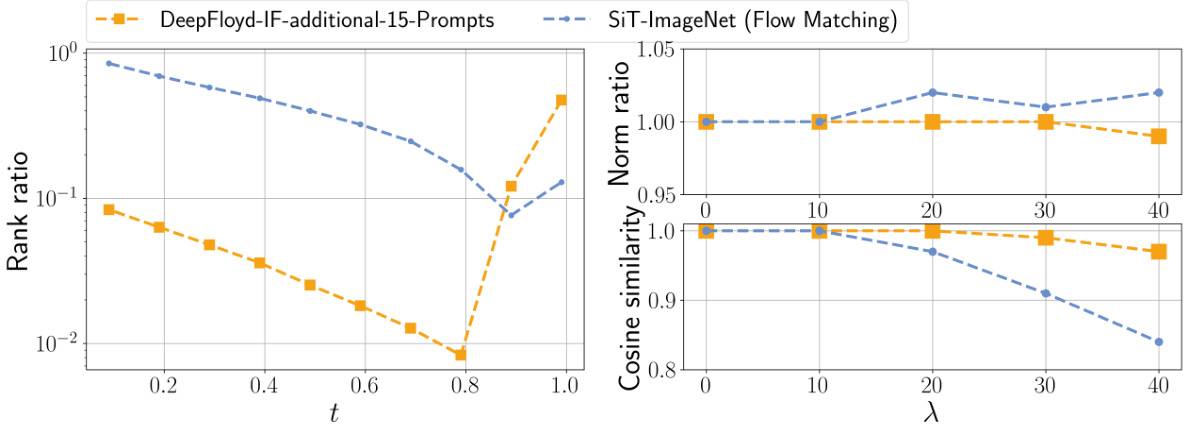

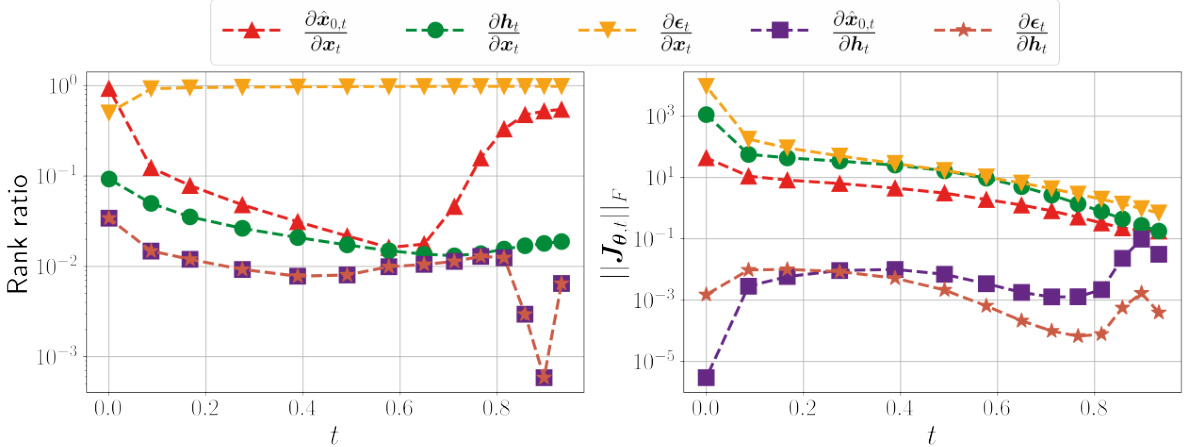

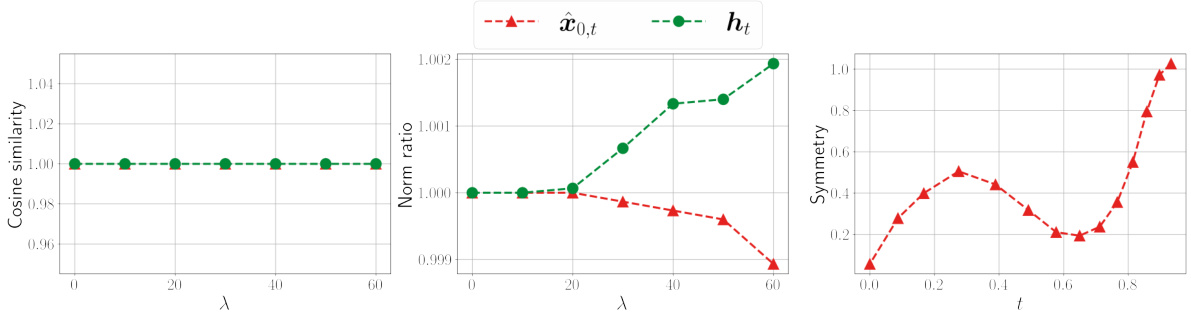

This figure demonstrates the low-rankness of the Jacobian and the local linearity of the Posterior Mean Predictor (PMP) in diffusion models. The left panel (a) shows the rank ratio of the Jacobian of the PMP across different timesteps (t) for various models trained on different datasets. A low rank ratio indicates that the Jacobian primarily acts on a low-dimensional subspace. The right panel (b) shows the norm ratio and cosine similarity between the true PMP output and a linear approximation of it using its Jacobian, calculated for a fixed timestep (t=0.7) and varying perturbation size (λ). High cosine similarity and norm ratio close to 1 indicate local linearity around the chosen timestep.

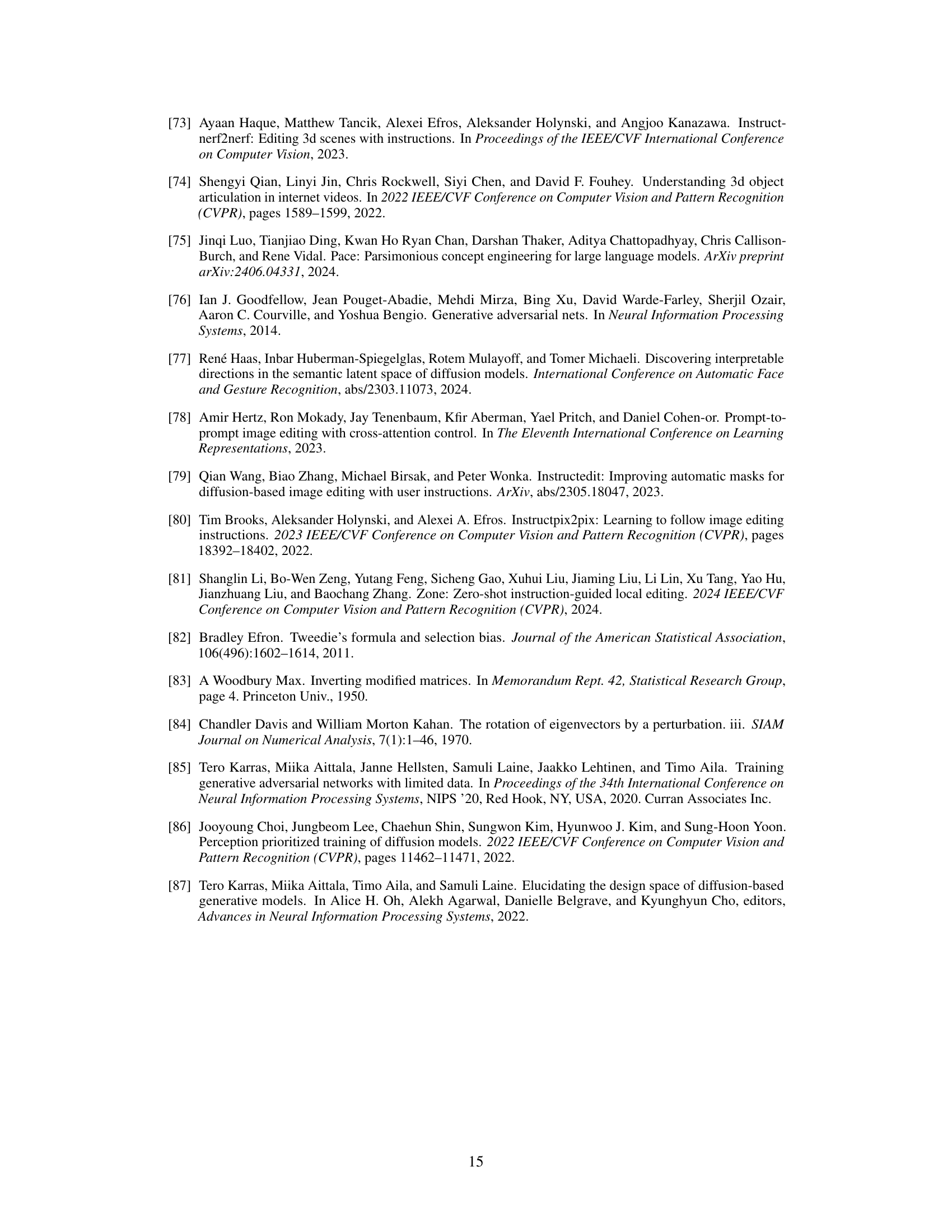

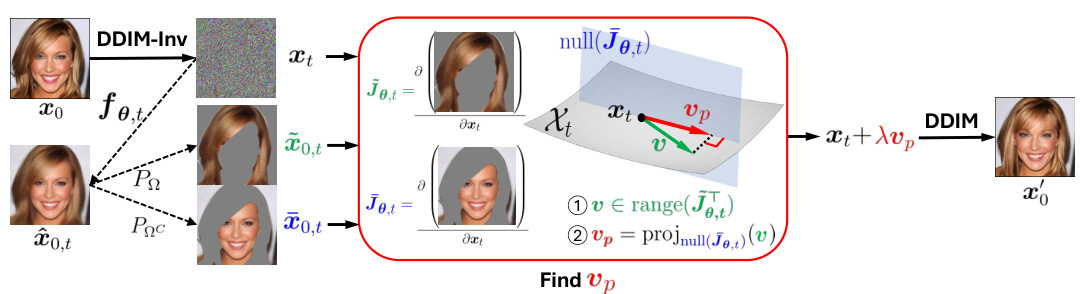

This figure illustrates the unsupervised LOCO Edit method. It starts with an original image (x0), applies DDIM-Inv to obtain a noisy image at time t (xt), and estimates the clean image at time t (x0,t). A mask is then applied to select a region of interest (ROI), and the Jacobian (J0,t) is calculated for this ROI. Singular value decomposition (SVD) is performed on J0,t, leading to the identification of an editing direction (v) within the range of J0,t. This vector is projected onto the null space of J0,t to obtain a localized edit direction (vp). Finally, the noisy image (xt) is modified by adding λvp (λ is the editing strength), and DDIM is applied to generate the final edited image (x′0).

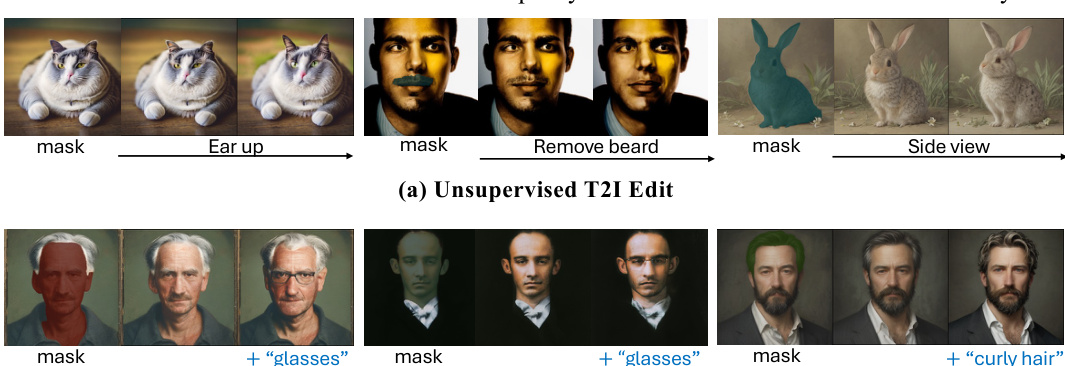

This figure demonstrates the results of T-LOCO Edit on three different text-to-image (T2I) diffusion models: Stable Diffusion, DeepFloyd, and Latent Consistency Model. The top row (a) shows unsupervised editing, where only a mask is used to define the region to be edited. The bottom row (b) shows text-supervised editing, where both a mask and a textual prompt are used to guide the editing process. This illustrates the versatility of the LOCO Edit method, which can be applied with or without textual prompts to achieve precise and controlled image edits.

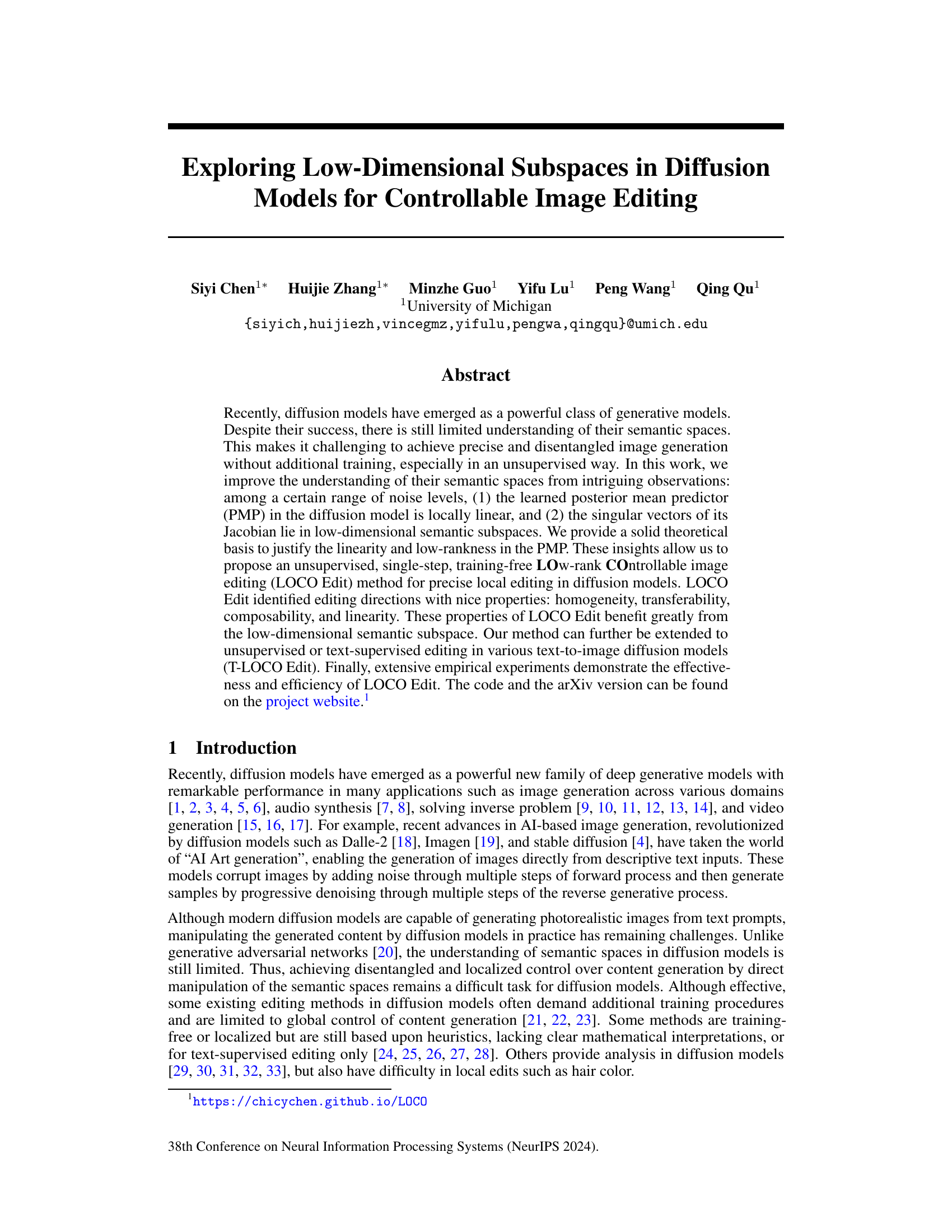

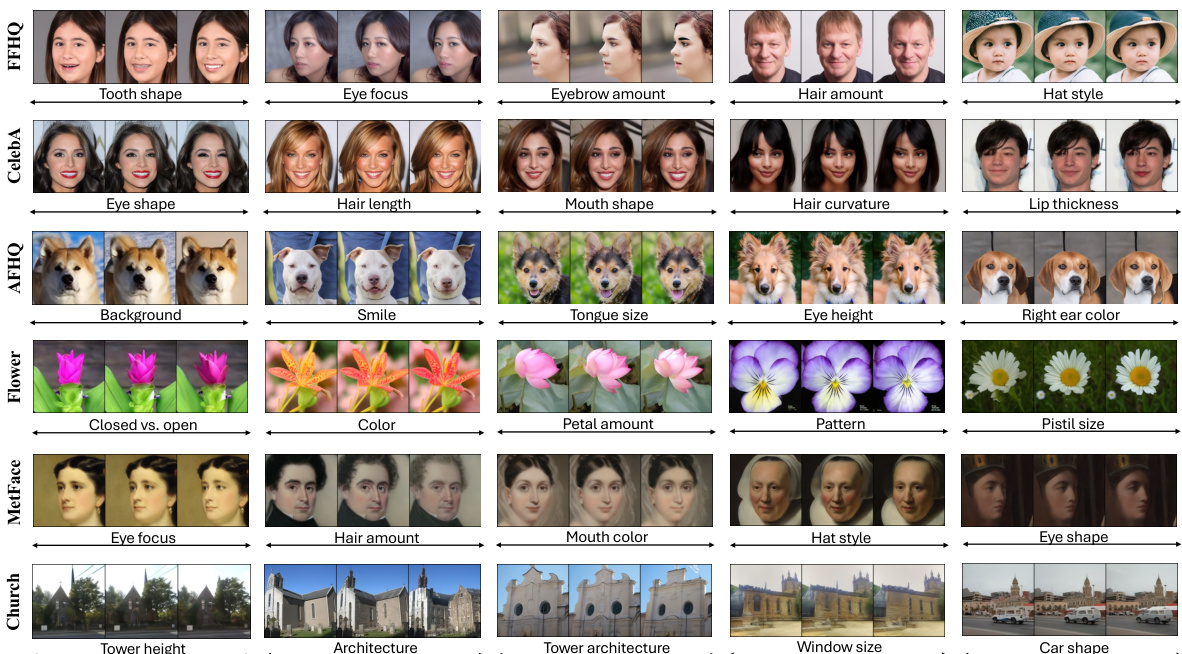

This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the LOCO Edit method on various datasets. Each group of three images shows an original image in the center, and edited versions with changes applied along negative and positive editing directions on the left and right respectively. The datasets include images of churches, faces, flowers, animals, and faces from different artistic periods. The figure showcases the method’s ability to perform precise localized edits in diverse contexts and maintain coherence across various image styles.

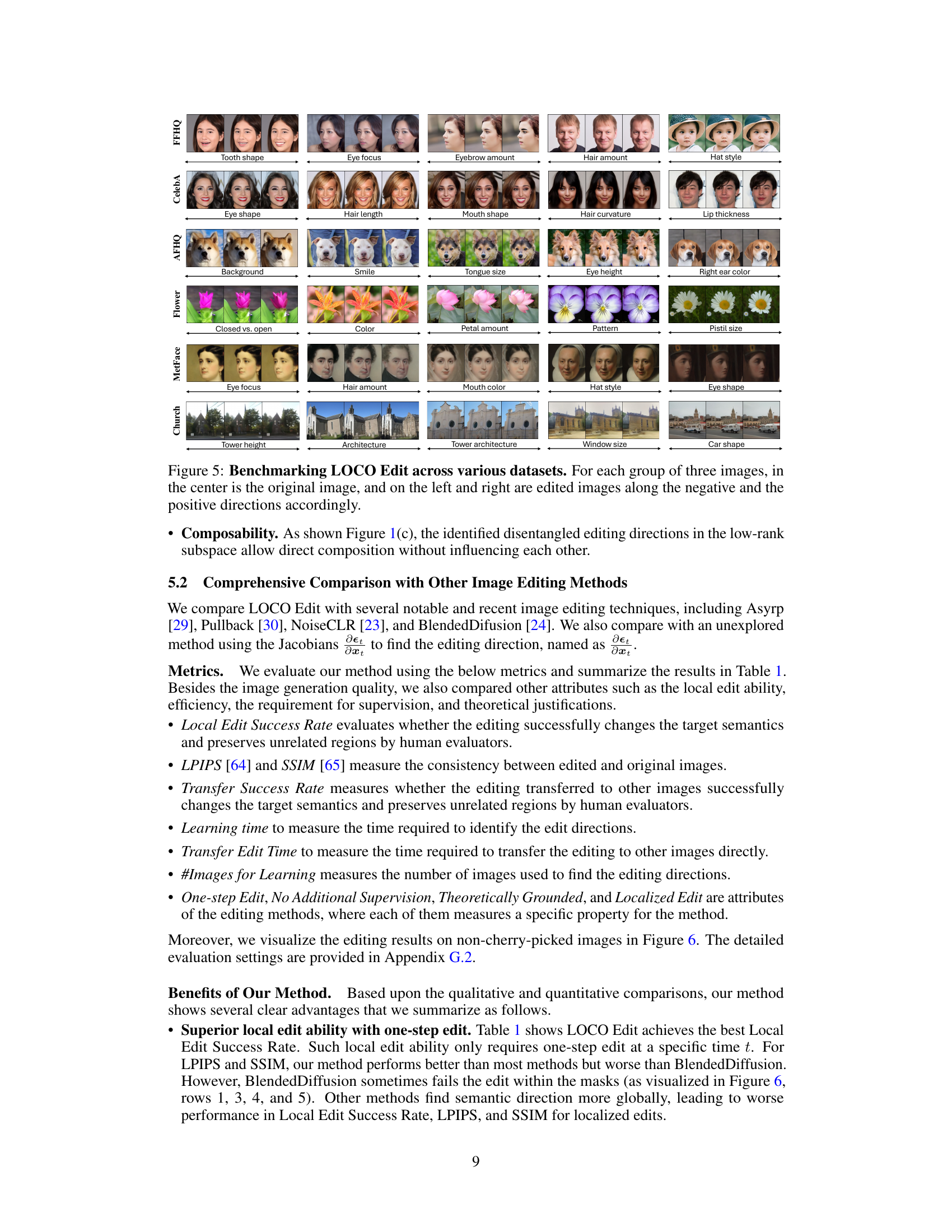

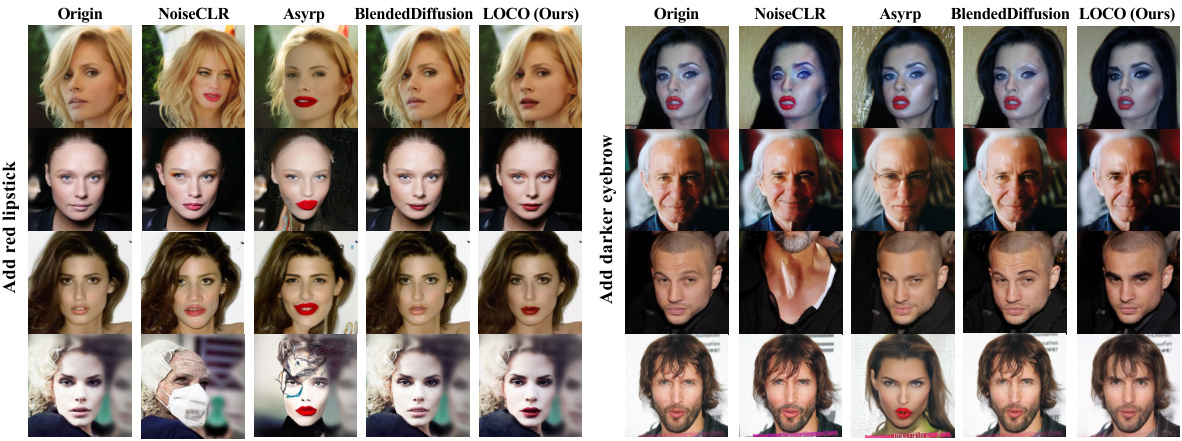

This figure compares the performance of LOCO Edit against other image editing methods on non-cherry-picked images, highlighting its ability to achieve precise and localized edits while other methods often result in inaccurate edits or fail to make any changes at all.

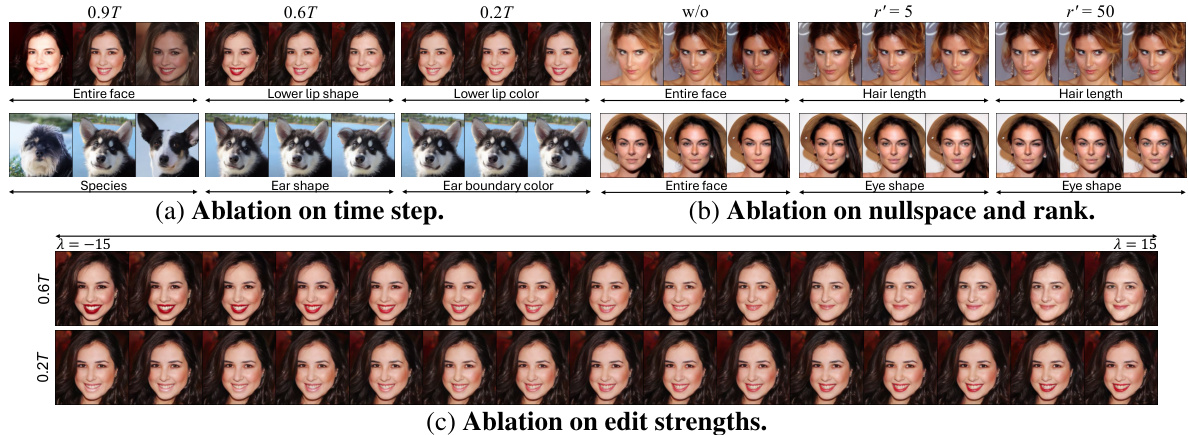

This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the impact of different factors on the performance of the LOCO Edit method. The studies examine three key aspects: (a) The effect of choosing different time steps for the single-step editing process. It shows that a range of time steps produce satisfactory results, with smaller values resulting in finer editing and larger values resulting in more coarse changes. (b) The impact of applying nullspace projection for localized edits, and the effect of using different ranks for this projection. The results indicate that using nullspace projection is crucial for improving editing precision, and that even a low rank is sufficient. (c) The effect of varying the magnitude of the editing strength (λ). This shows that a wide range of editing strengths can achieve effective localized edits, confirming the method’s linearity.

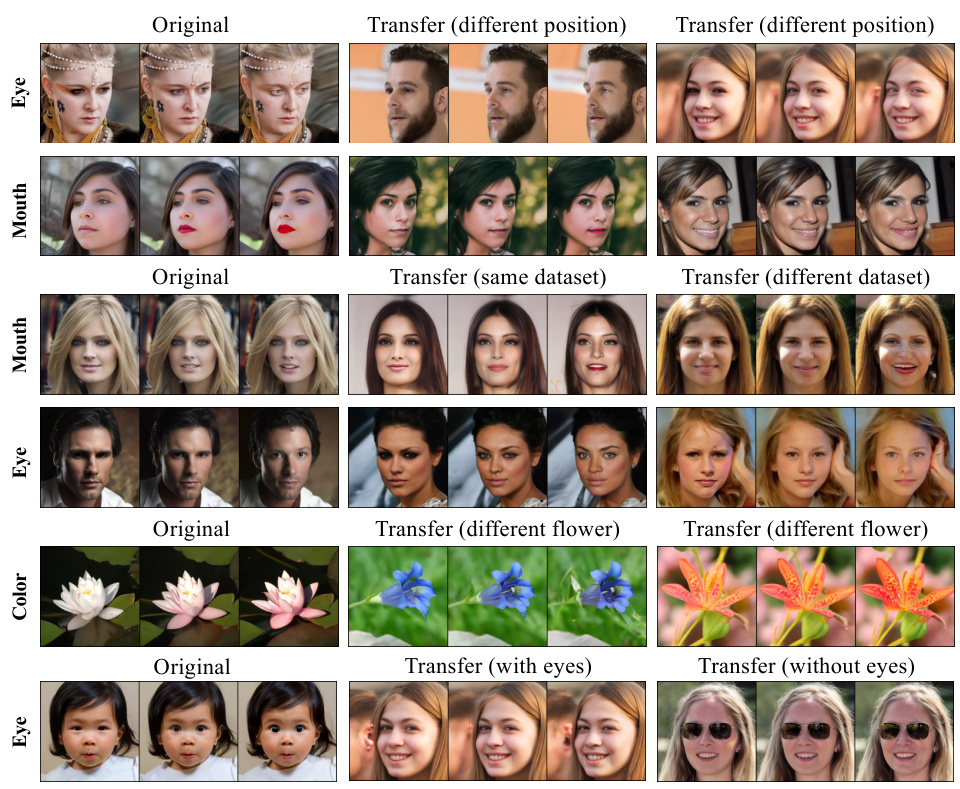

This figure demonstrates the transferability of the editing directions identified by LOCO Edit. The top row shows edits transferred to images of faces with varying poses and positions. The second row shows edits transferred between images of the same dataset and different datasets. The third row displays edits transferred to images of flowers. The final row illustrates transferability to images with and without eyes, demonstrating the method’s sensitivity to the presence of the target feature.

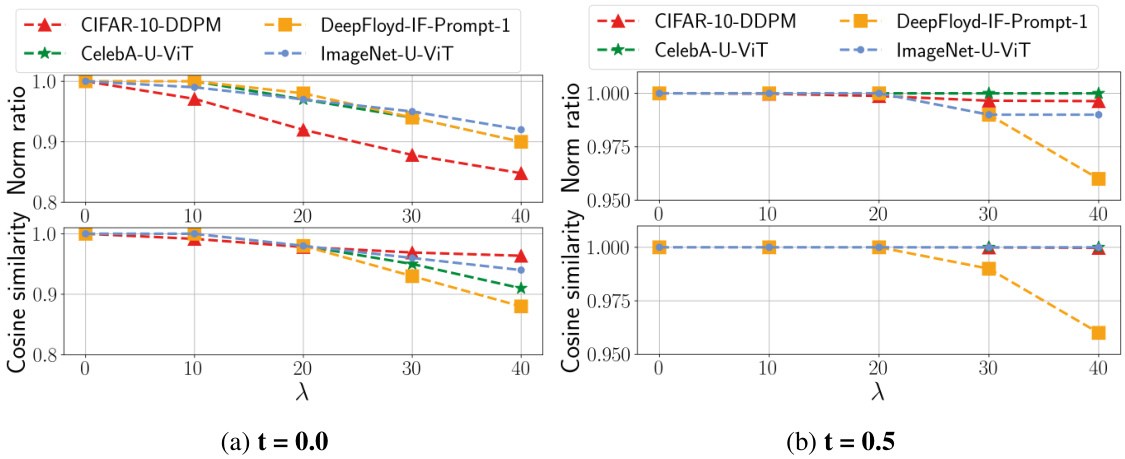

This figure empirically shows the low-rankness of the Jacobian and local linearity of the Posterior Mean Predictor (PMP) in diffusion models. It uses four different models trained on various datasets and displays the rank ratio of the Jacobian of the PMP at different timesteps, as well as the norm ratio and cosine similarity to demonstrate its linearity.

This figure demonstrates the capabilities of the LOCO Edit method. Subfigure (a) shows an example of precise localized image editing, while (b) highlights the homogeneity and transferability of the editing directions. The composability of disentangled directions is shown in (c), and finally, (d) illustrates the linearity of the editing directions. These properties showcase the effectiveness and efficiency of the method for precise and controllable image editing.

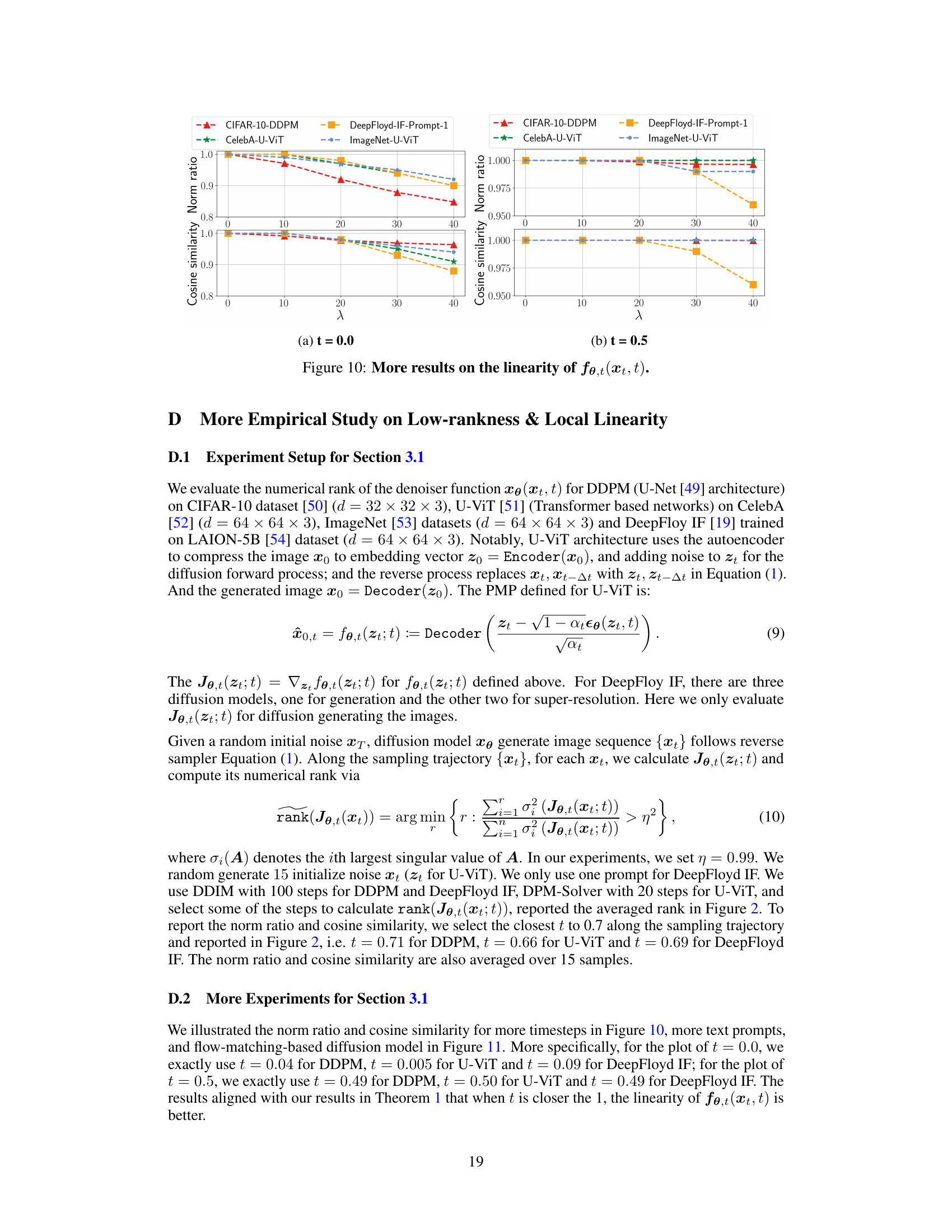

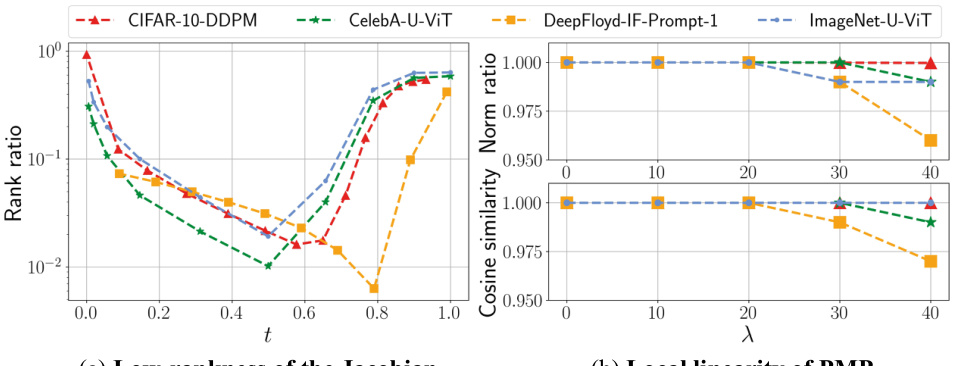

This figure shows the numerical rank and the Frobenius norm of different Jacobians (∂x₀,ₜ/∂xₜ, ∂hₜ/∂xₜ, ∂εₜ/∂xₜ, ∂x₀,ₜ/∂hₜ, ∂εₜ/∂hₜ) at different timesteps (t). It visually demonstrates the low-rank property of certain Jacobians within a specific time range, supporting the paper’s claim regarding the low-dimensionality of the semantic subspaces in diffusion models. The left subplot shows the rank ratios, and the right subplot shows the Frobenius norm, both plotted against time t.

This figure illustrates the process of the unsupervised LOCO Edit method. It starts with an original image (x0), generates a noisy image (xt) at a specific timestep (t), and then estimates the clean image (x0,t) using the posterior mean predictor (PMP). A mask is applied to select the region of interest (ROI), and the Jacobian of the PMP is computed for this ROI. Singular value decomposition (SVD) and nullspace projection are used to find an editing direction (v^p) that modifies the image within the ROI while preserving other areas. Finally, the edited image (x′) is generated by applying the editing direction to the noisy image and then denoising it using DDIM.

Full paper#