↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD) is a successful approach, but many existing molecule generation methods struggle to explore beyond existing fragments. These methods primarily reassemble or slightly modify known fragments, limiting the discovery of novel drug candidates with better properties. This often leads to a trade-off between efficiently using existing knowledge (exploitation) and the discovery of new high-quality fragments (exploration).

To tackle this challenge, the paper introduces f-RAG (Fragment Retrieval-Augmented Generation), a new framework that augments a pre-trained molecular generative model with retrieval augmentation. f-RAG retrieves two types of fragments: “hard” fragments, explicitly included in the new molecule, and “soft” fragments, used as guidance during generation. The model is iteratively refined, adding generated high-quality fragments to its vocabulary and using genetic algorithms for further optimization. This improved exploration-exploitation balance leads to better optimization performance and more diverse, novel, and synthesizable drug candidates.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in drug discovery and machine learning. It presents f-RAG, a novel framework that significantly improves molecule generation by combining fragment-based drug discovery with retrieval augmentation. This addresses the limitations of existing methods by exploring beyond known fragments, leading to more diverse and novel drug candidates. The proposed approach’s strong performance and exploration-exploitation trade-off open new avenues for research in molecular optimization and generative modeling.

Visual Insights#

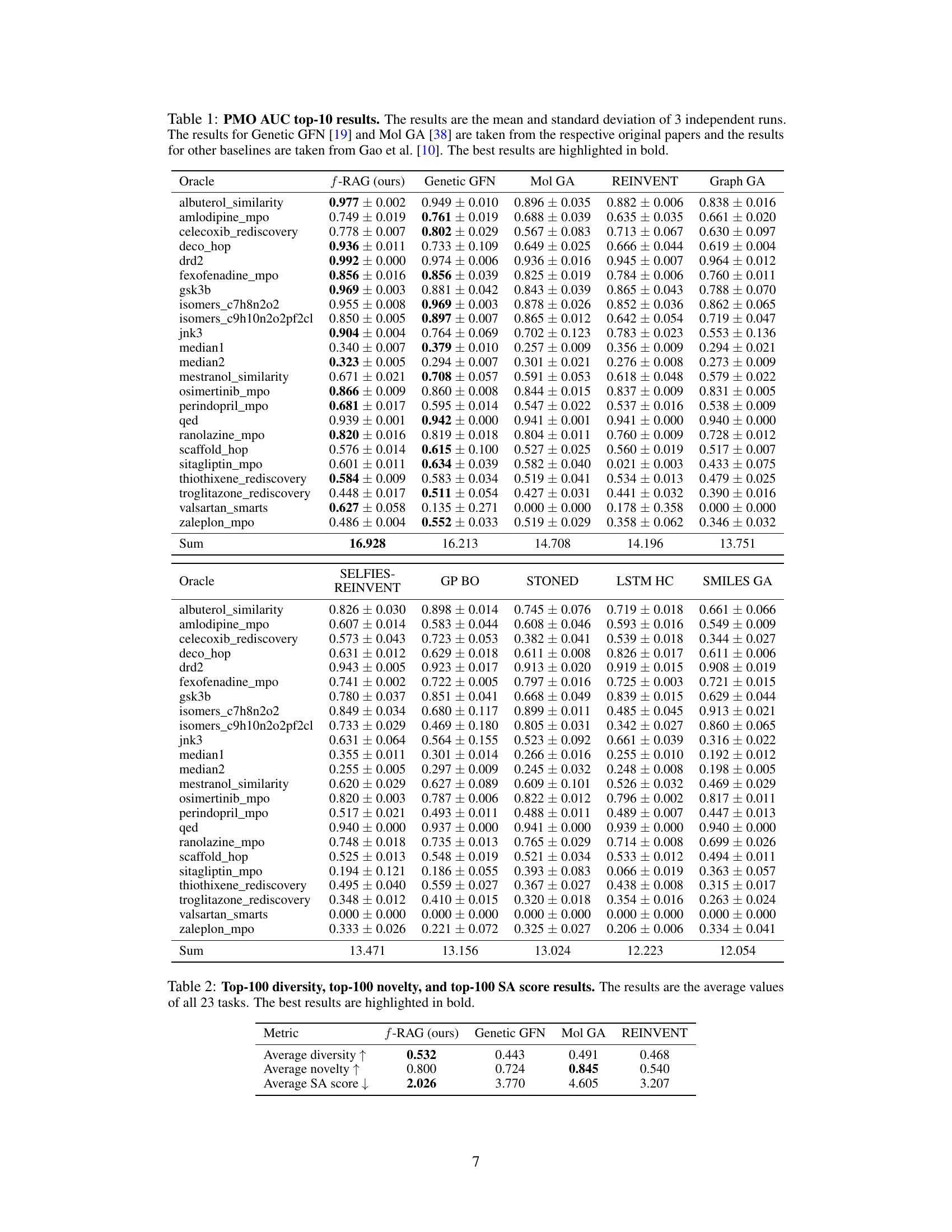

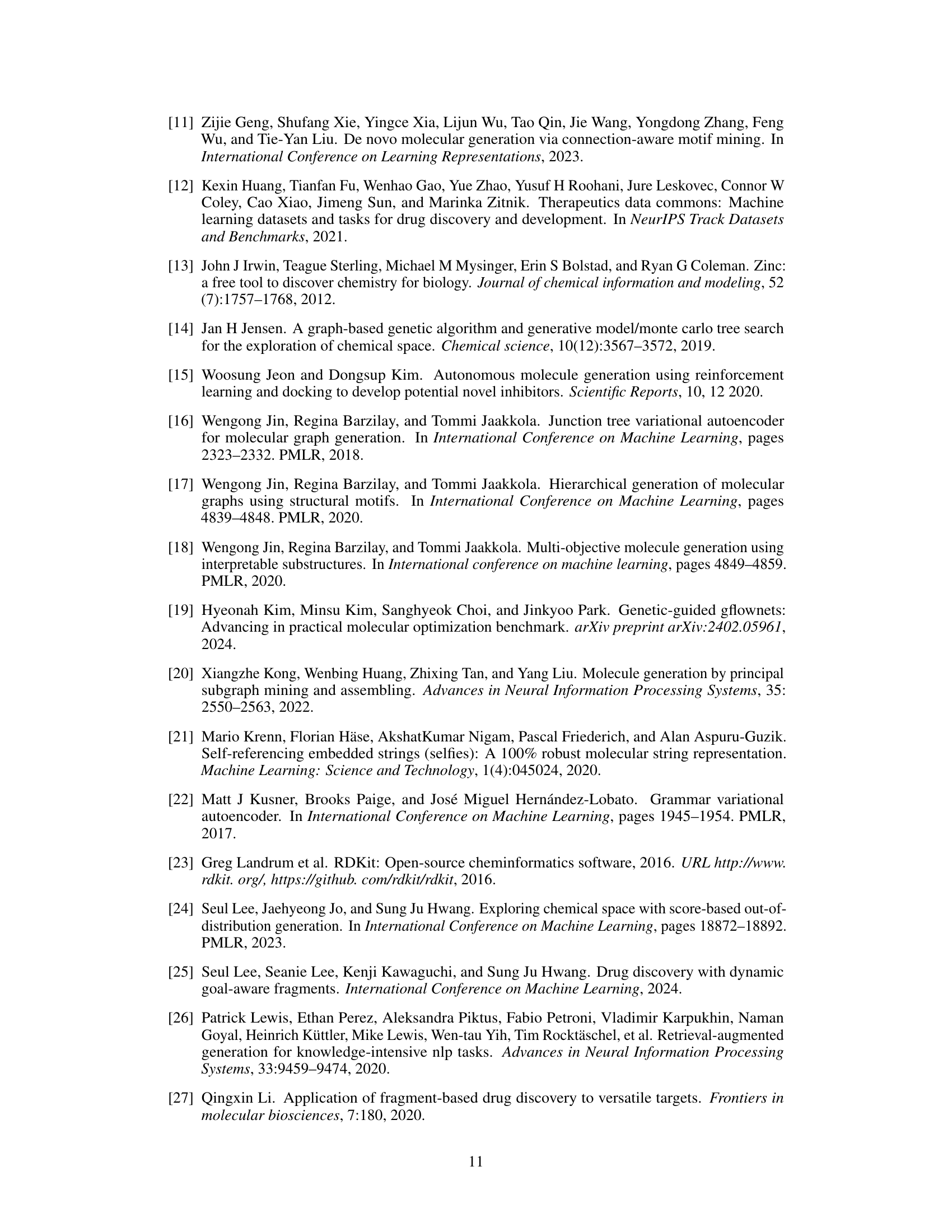

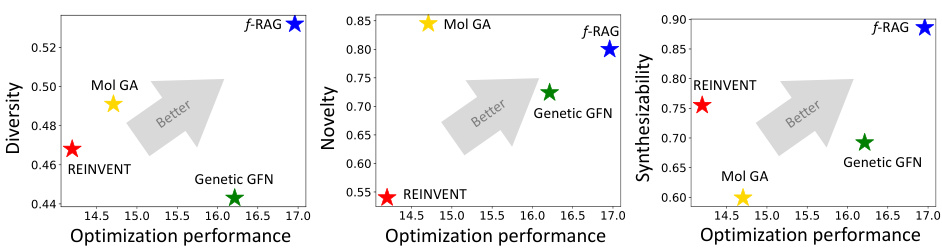

The radar plot compares the performance of f-RAG against other state-of-the-art methods across four key aspects in molecular optimization: optimization performance, diversity, novelty, and synthesizability. Each axis represents one of these properties, and the plotted points show the relative strength of each method in each area. f-RAG demonstrates a superior balance, excelling in all aspects when compared to the other methods. This figure visually highlights the advantage of f-RAG in drug discovery tasks.

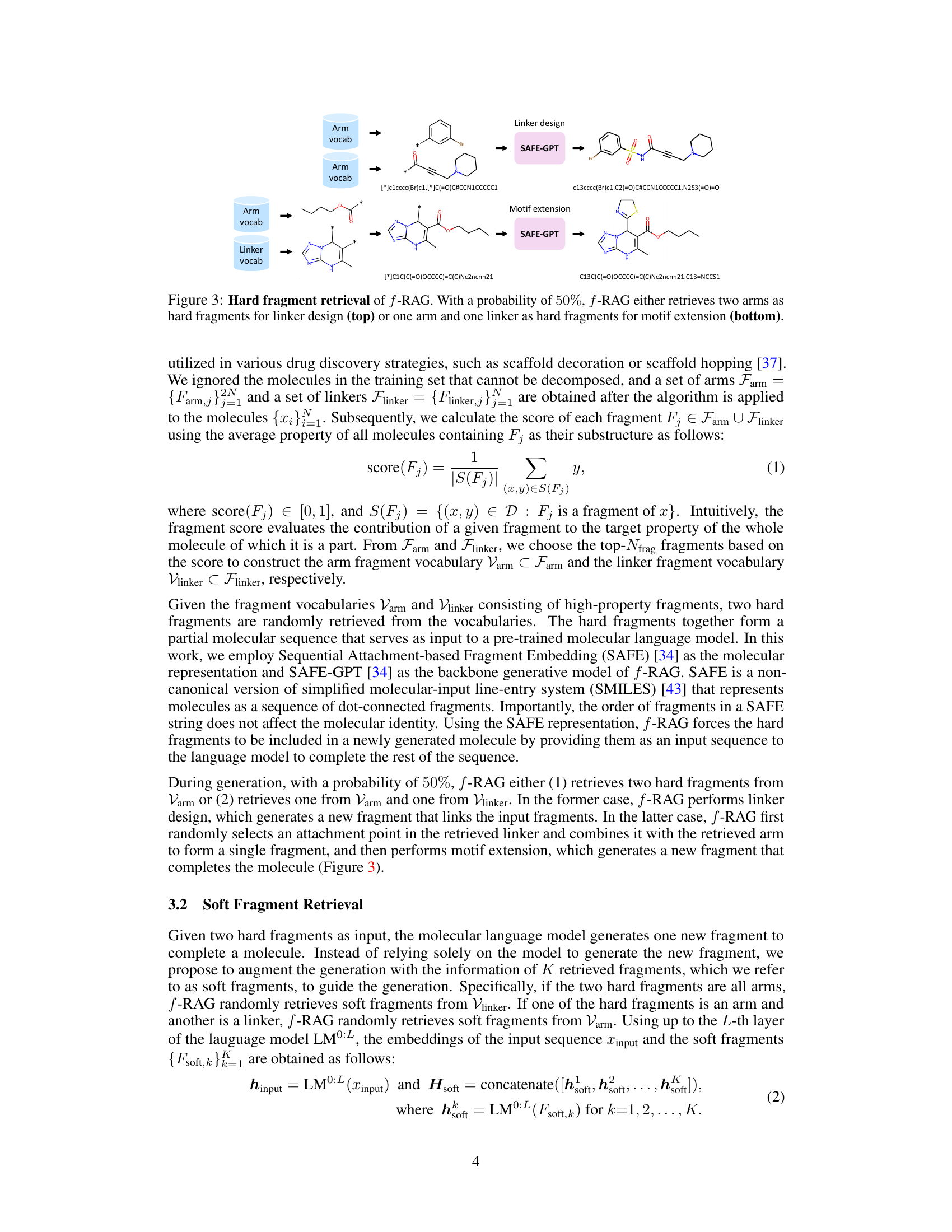

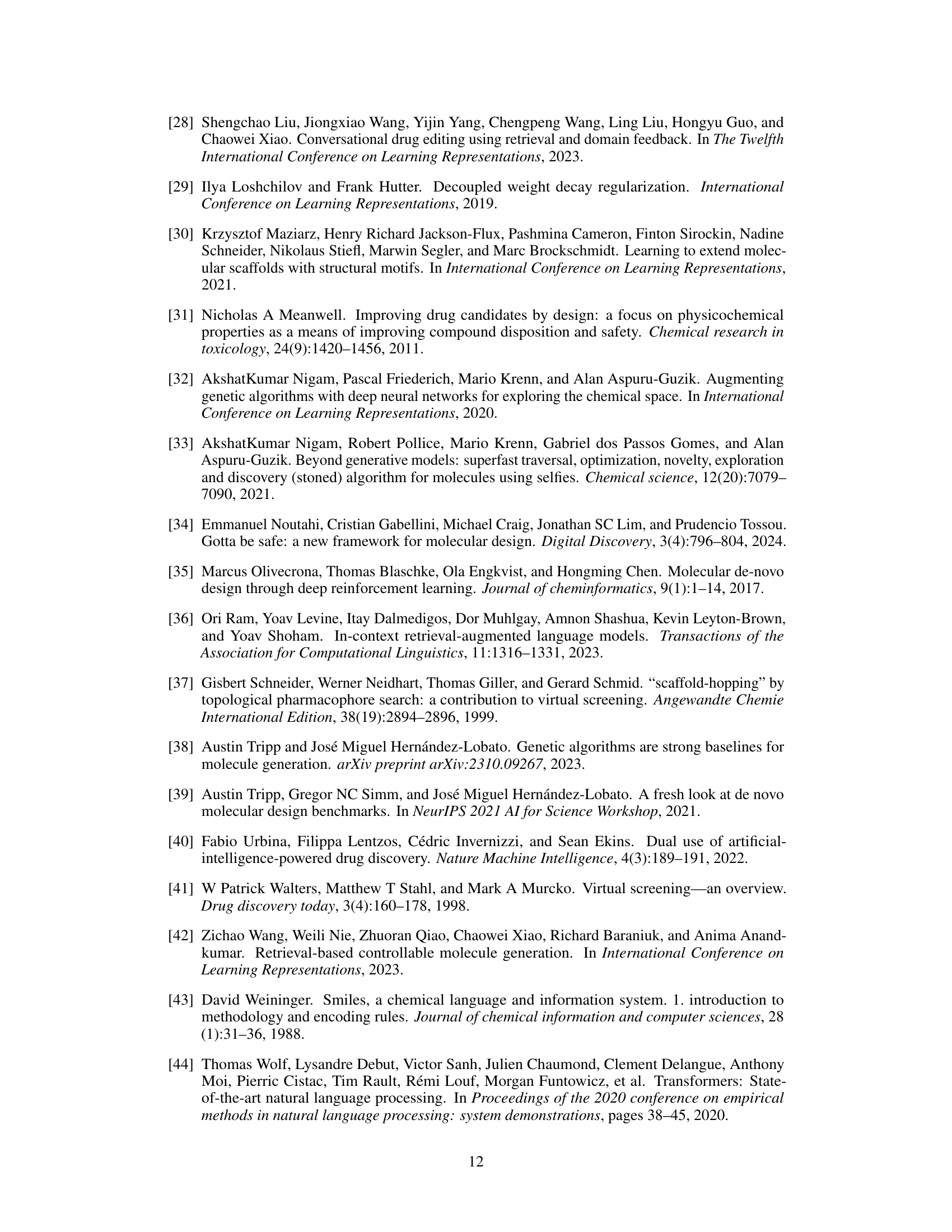

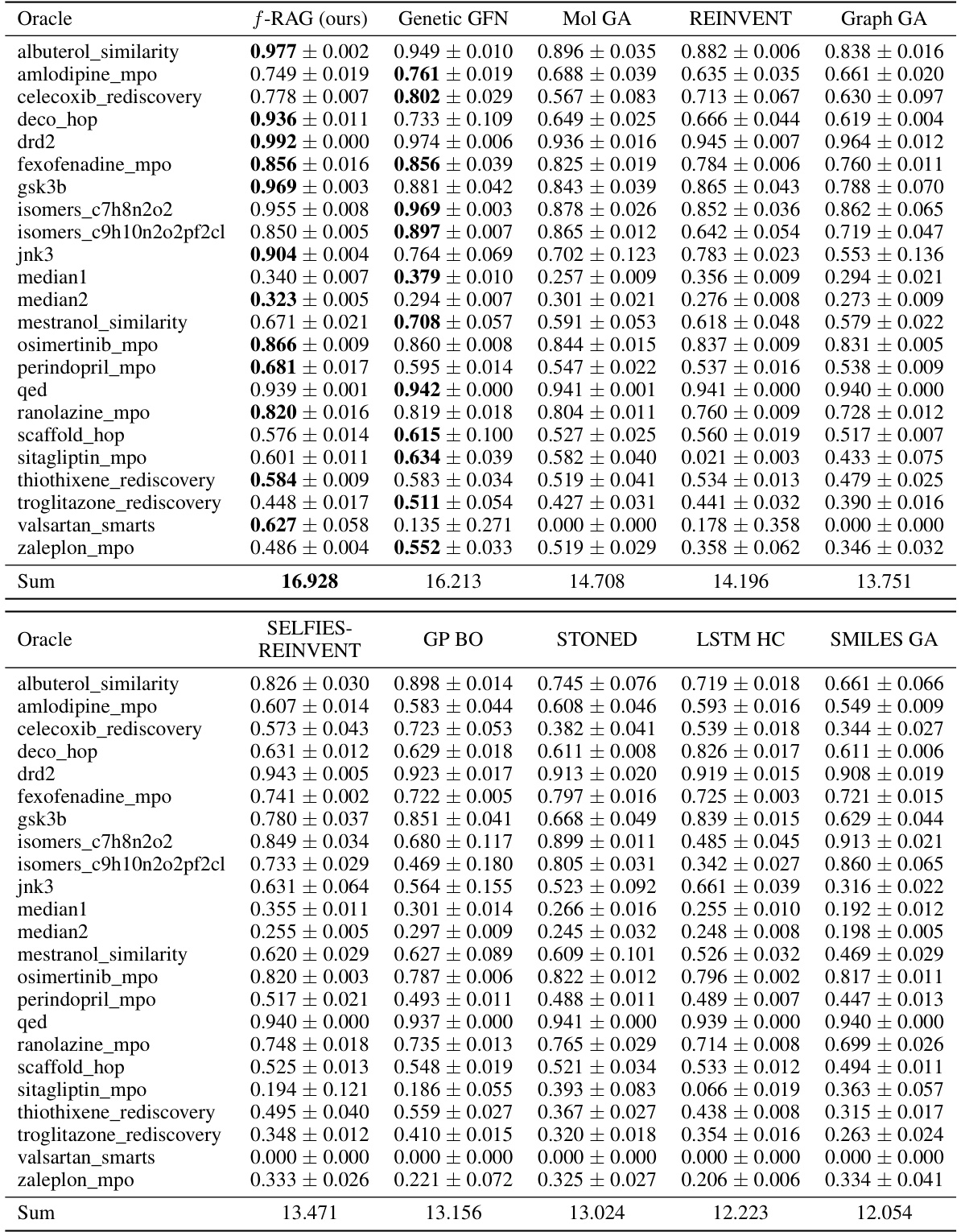

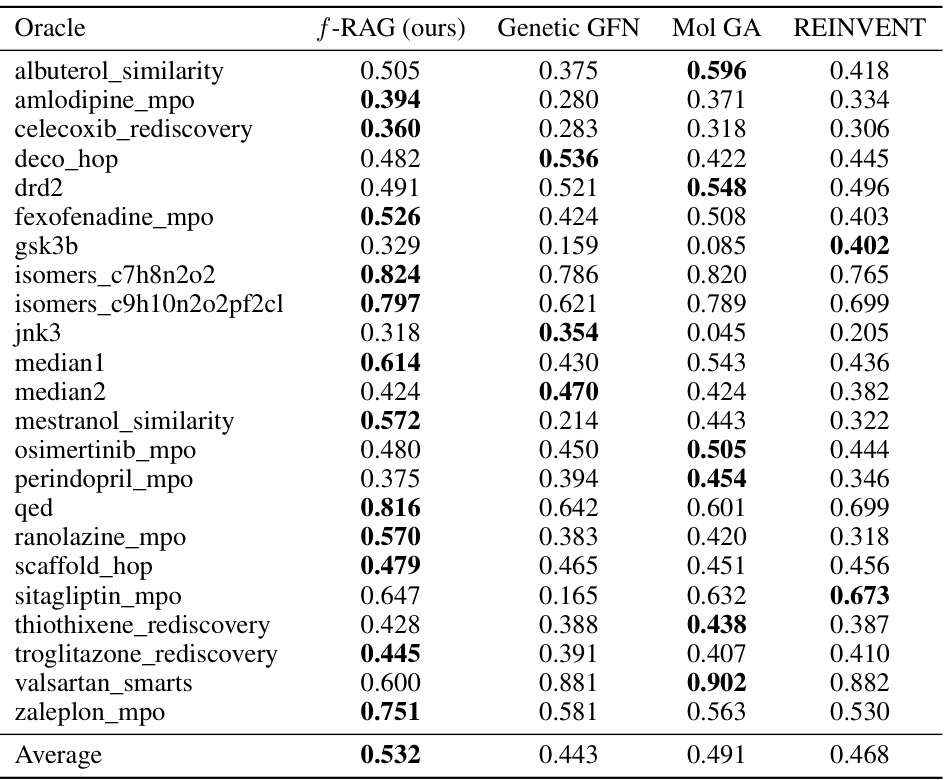

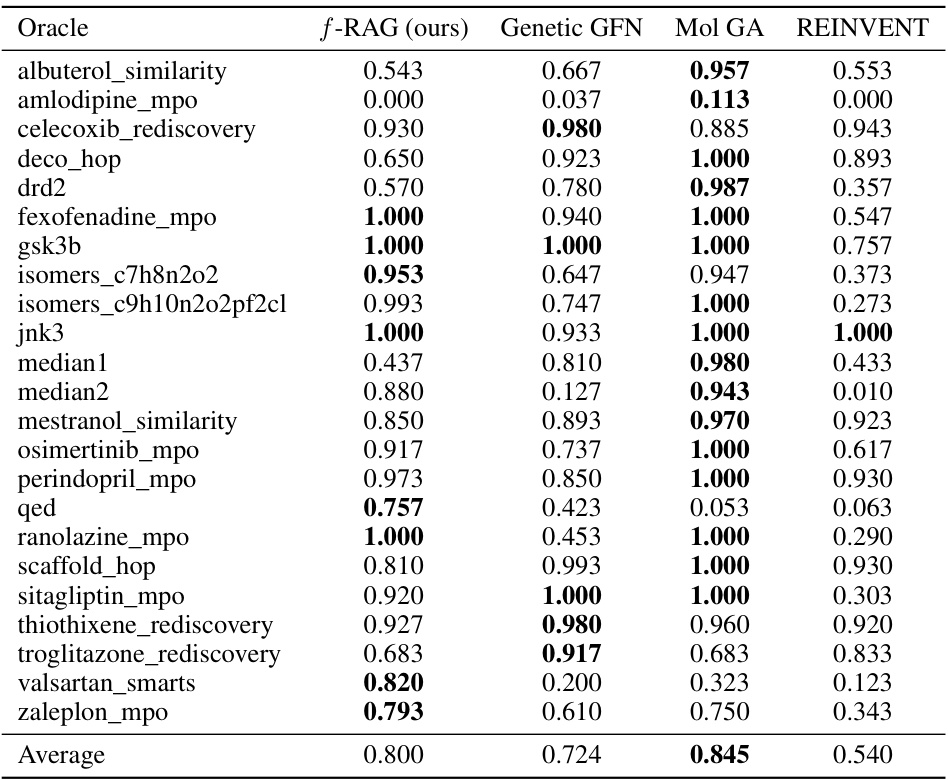

This table presents the results of the practical molecular optimization (PMO) benchmark. It shows the area under the curve (AUC) of the average property scores of the top-10 molecules versus oracle calls for several methods, including f-RAG, Genetic GFN, Mol GA, REINVENT, Graph GA, SELFIES-REINVENT, GP BO, STONED, LSTM HC, and SMILES GA. It also shows diversity, novelty and synthesizability scores for each method.

In-depth insights#

Frag Retrieval Augmentation#

Fragment Retrieval Augmentation represents a novel approach to molecular generation, enhancing the exploration and exploitation balance in drug discovery. It leverages a pre-trained molecular generative model augmented by retrieving two types of fragments: ‘hard’ fragments, directly incorporated into the generated molecule, and ‘soft’ fragments, guiding the generation of novel structures. This dual approach facilitates a more balanced exploration of chemical space, extending beyond existing fragment libraries. The iterative refinement of the fragment vocabulary, coupled with post-hoc genetic fragment modification, further optimizes this trade-off, leading to a higher likelihood of discovering diverse, novel, and high-quality molecules suitable for drug development. The effectiveness of this strategy is demonstrated by its superior performance on various benchmarks, showcasing a significant advantage over existing methods.

SAFE-GPT Enhancement#

A hypothetical ‘SAFE-GPT Enhancement’ section in a research paper would likely detail modifications improving the model’s performance beyond its original capabilities. This could involve several key areas. Architectural improvements might include adding new layers, attention mechanisms, or residual connections to enhance learning and generalization. Data augmentation techniques might be explored to address potential biases and limitations in training datasets. This could be done by generating synthetic molecules with desired properties or by incorporating external knowledge bases to enrich the training data. Fine-tuning strategies could target specific tasks or datasets for optimized performance, possibly through transfer learning from related domains, further enhancing the model’s robustness and predictive accuracy. Addressing limitations is another key aspect, perhaps through the development of methods to mitigate overfitting or improve the handling of novel, unseen chemical structures. Finally, evaluating the enhanced model’s efficiency, in terms of both computation and memory usage, while maintaining accuracy and effectiveness is crucial for practical applications.

Genetic Fragment Mod#

The heading ‘Genetic Fragment Modification’ suggests a method to enhance the diversity and novelty of generated molecules. It likely involves applying genetic algorithm operators (mutation, crossover) to modify existing fragments, creating new structural variations not present in the initial fragment library. This process could significantly improve exploration of the chemical space, potentially leading to the discovery of molecules with unique properties and improved optimization outcomes. By introducing new fragments generated through these genetic manipulations back into the fragment pool, the model is able to iteratively refine and expand its chemical knowledge. This iterative refinement process is a key strength, allowing for continuous exploration and exploitation of chemical space. The success of this approach, however, relies heavily on the effectiveness of genetic operators tailored to molecular structures. Careful design and implementation of these operators are crucial to ensure a balance between exploration and exploitation; otherwise the algorithm could lead to many non-viable molecules, thus decreasing the overall efficiency of the drug discovery process.

Exploration-Exploitation#

The exploration-exploitation dilemma is central to many fields, including drug discovery. Exploration involves searching for novel molecular structures with potentially improved properties, while exploitation focuses on optimizing existing structures for enhanced performance. In the context of molecule generation, this trade-off is critical. Overly emphasizing exploration might lead to inefficient, low-quality molecules; focusing solely on exploitation could limit the discovery of superior drug candidates. Balancing this trade-off is essential; strategies that effectively combine the exploration of novel chemical space with the efficient optimization of promising leads are crucial. This often requires innovative algorithms that can learn from both successful and failed attempts, dynamically adjusting their search strategy based on feedback and existing knowledge. Effective strategies may involve incorporating techniques like reinforcement learning or evolutionary algorithms, allowing the model to both explore diverse areas of chemical space while also fine-tuning promising molecules already identified.

Drug Discovery Tasks#

Drug discovery is a complex process, and various tasks are involved in identifying and developing new medications. Fragment-based drug discovery (FBDD), a prevalent approach, focuses on assembling small molecular fragments into larger molecules with desired properties. Generative models, such as the one discussed in the research paper, have emerged as powerful tools to accelerate this process. These models address several crucial drug discovery tasks: optimization, aiming to enhance molecules’ properties; diversity, ensuring a range of molecular structures to explore different functionalities; novelty, seeking molecules distinct from existing drugs; and synthesizability, prioritizing molecules that are easily manufactured. The success of these models depends on their ability to strike a balance between exploration (discovering new chemical space) and exploitation (optimizing known promising molecules). The integration of retrieval augmentation, as highlighted in the paper, enhances this balance by facilitating both exploration and exploitation, ultimately improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the drug discovery workflow.

More visual insights#

More on figures

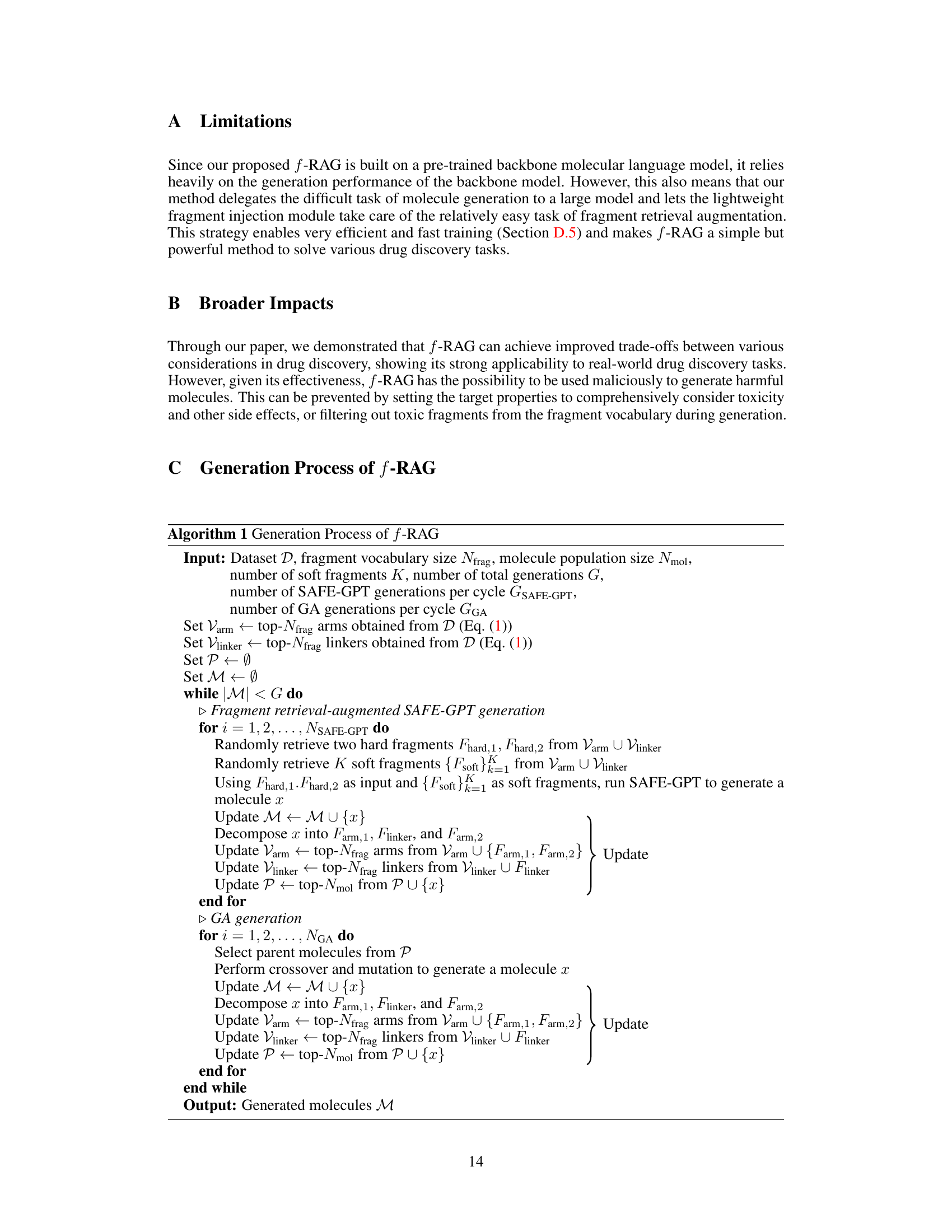

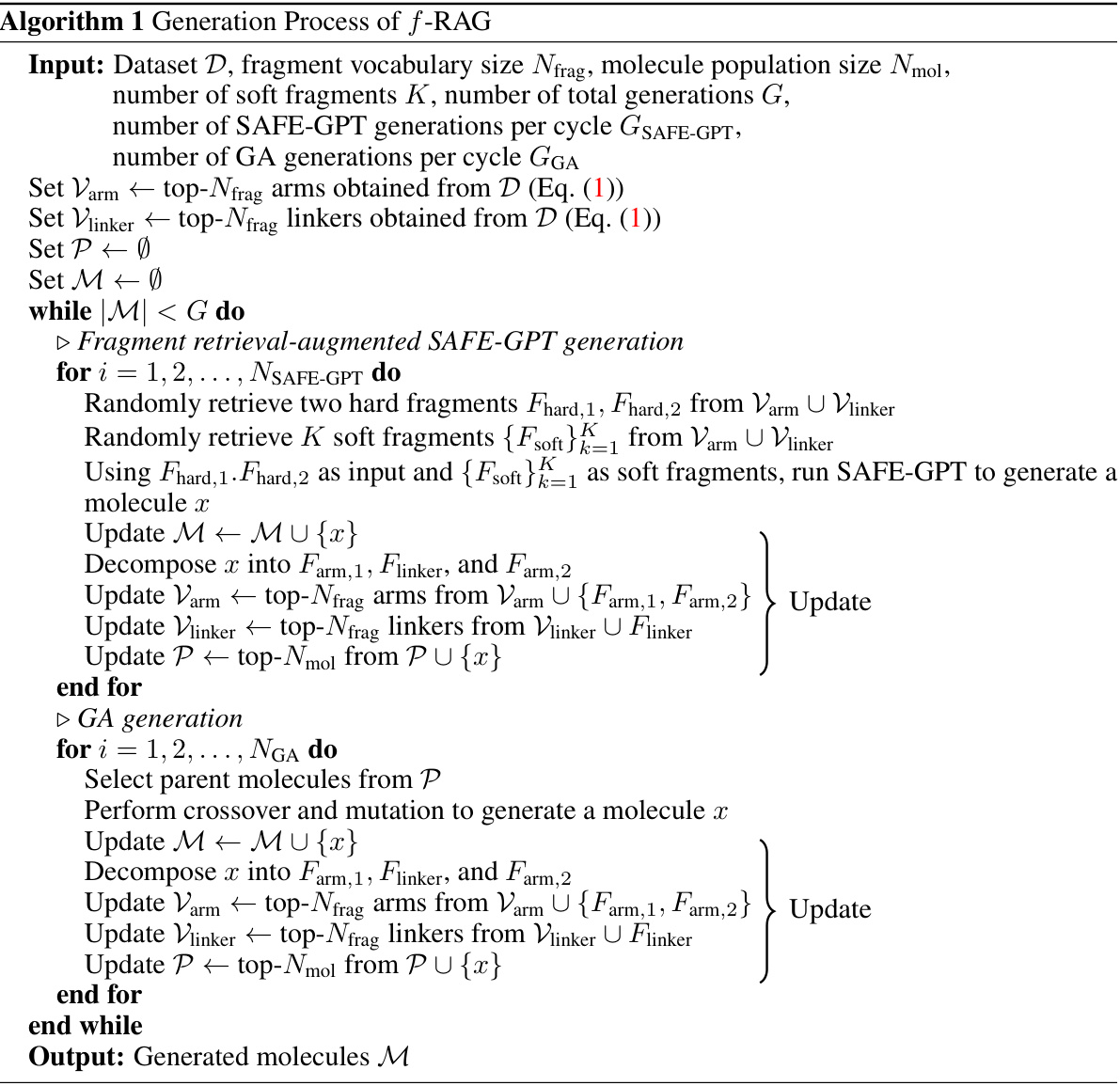

This figure illustrates the f-RAG framework. It starts with an initial fragment vocabulary built from an existing molecule library. During molecule generation, f-RAG retrieves two types of fragments: hard fragments (explicitly included in the new molecule) and soft fragments (implicitly guide the generation of new fragments). A pre-trained molecular language model (SAFE-GPT) uses the hard fragments as input, with the soft fragment embeddings injected via a fragment injection module. After generation, the model iteratively refines its fragment vocabulary and molecule population using the newly generated molecule and fragments, further enhanced by post-hoc genetic fragment modification.

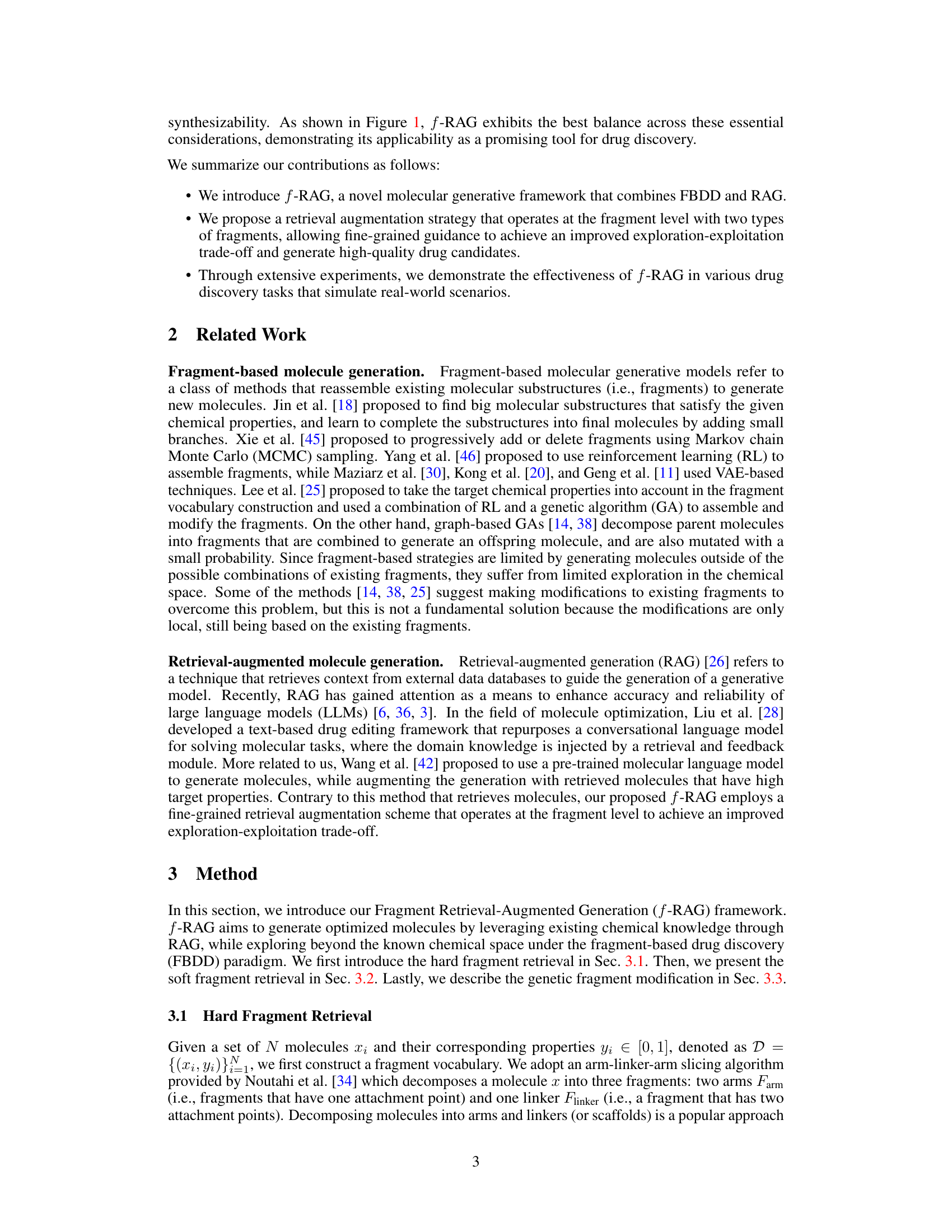

This figure illustrates the two hard fragment retrieval strategies used in the f-RAG framework. The top half shows the linker design strategy, where two arm fragments are retrieved and used as input to the SAFE-GPT model to generate a linker fragment that connects them. The bottom half shows the motif extension strategy, where an arm and a linker fragment are retrieved. The arm is connected to an attachment point on the linker and then fed into SAFE-GPT to generate a new fragment to complete the molecule.

This figure illustrates the self-supervised training process for the fragment injection module in the f-RAG model. The goal is to learn how to effectively incorporate soft fragments (similar fragments that aren’t part of the final molecule) into the generation process. The model uses two hard fragments (F1 and F2) as input, along with a set of K soft fragments (F3 and its k nearest neighbors). The training objective is to predict the k-th nearest neighbor to F3 (F3NN) given the hard and soft fragments, using a cross-entropy loss.

This radar plot visualizes the performance of f-RAG against other state-of-the-art molecule generation techniques across four key aspects: optimization performance, diversity, novelty, and synthesizability. Each axis represents one of these aspects, with the distance from the center indicating the relative strength of the method in that area. The plot demonstrates that f-RAG achieves a better balance across all four criteria compared to existing methods, showing its ability to generate molecules that are both optimized for specific properties and also diverse, novel, and synthesizable.

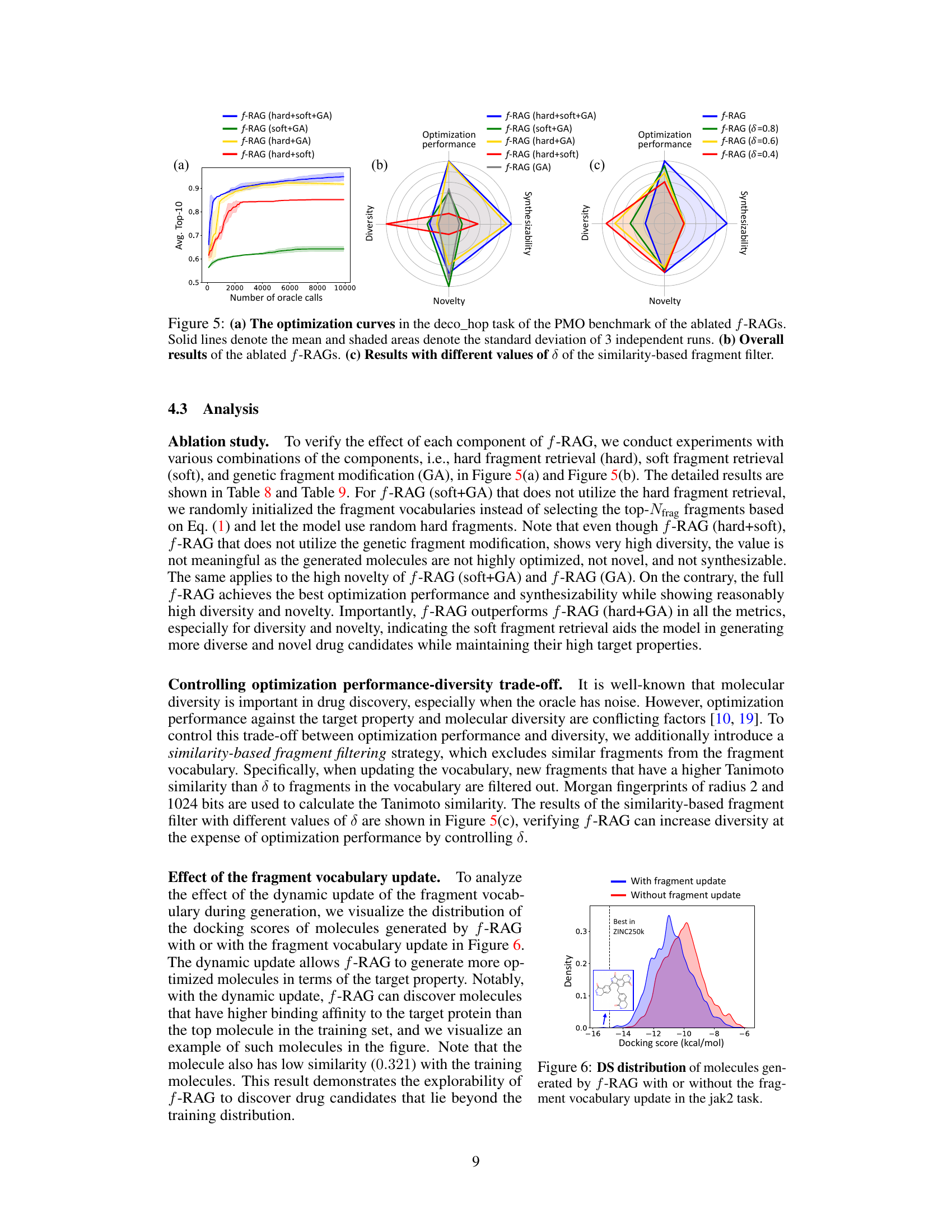

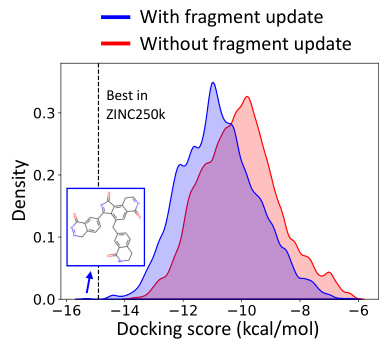

This figure shows the distribution of docking scores (DS) for molecules generated using f-RAG, with and without the fragment vocabulary update during the generation process for the jak2 task. The blue curve represents the molecules generated with the dynamic update of the fragment vocabulary, showing a wider range of DS values including molecules that have higher binding affinity to the target protein compared to the top molecule in the training set. The red curve represents those generated without the update, demonstrating a narrower distribution of DS values. This visualization highlights the benefit of the dynamic update, improving the explorability of f-RAG and allowing it to discover molecules beyond the training data distribution.

The radar plot compares the performance of f-RAG against other state-of-the-art molecule generation methods across four key aspects: optimization performance, diversity, novelty, and synthesizability. Each axis represents one of these properties, and the length of the line extending from the center to the axis indicates the method’s score on that property. f-RAG outperforms the others by exhibiting a superior balance across all four dimensions.

More on tables

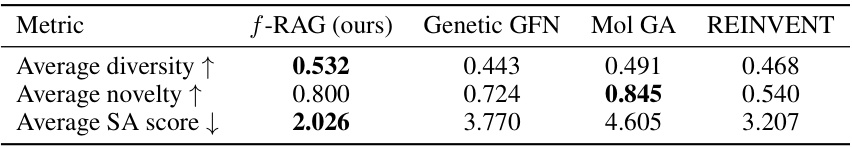

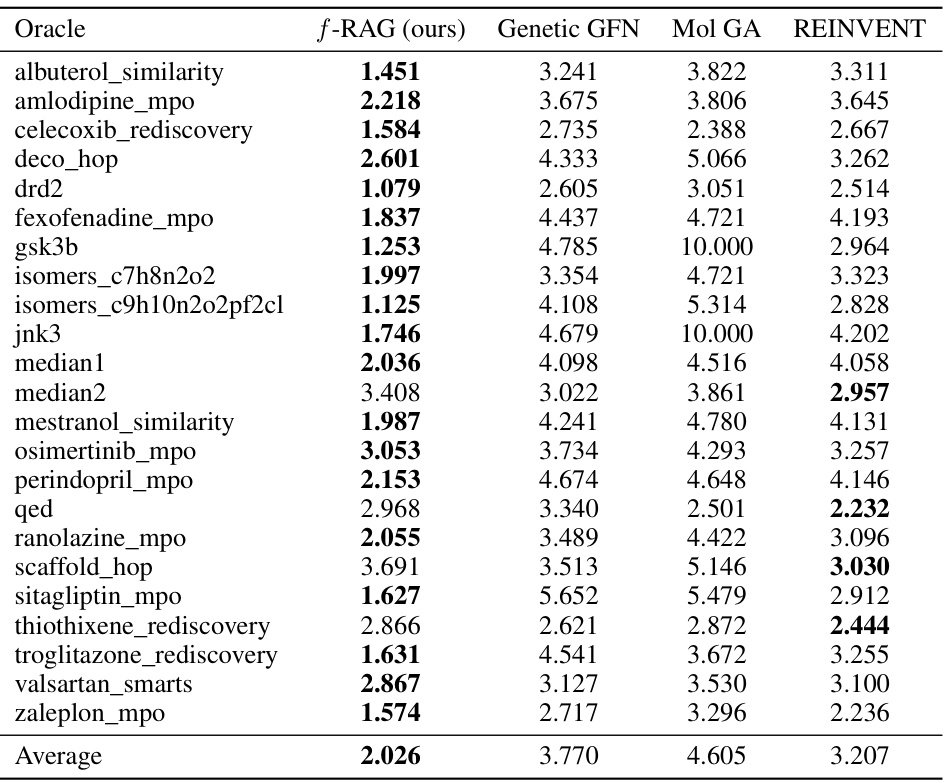

This table presents a comparison of three metrics (diversity, novelty, and synthetic accessibility score) across four different methods (f-RAG, Genetic GFN, Mol GA, and REINVENT) on a benchmark of 23 molecular optimization tasks. Higher values for diversity and novelty are better, while a lower value for the SA score is preferred, indicating easier synthesis. f-RAG shows a competitive performance, achieving the best diversity and SA score on average.

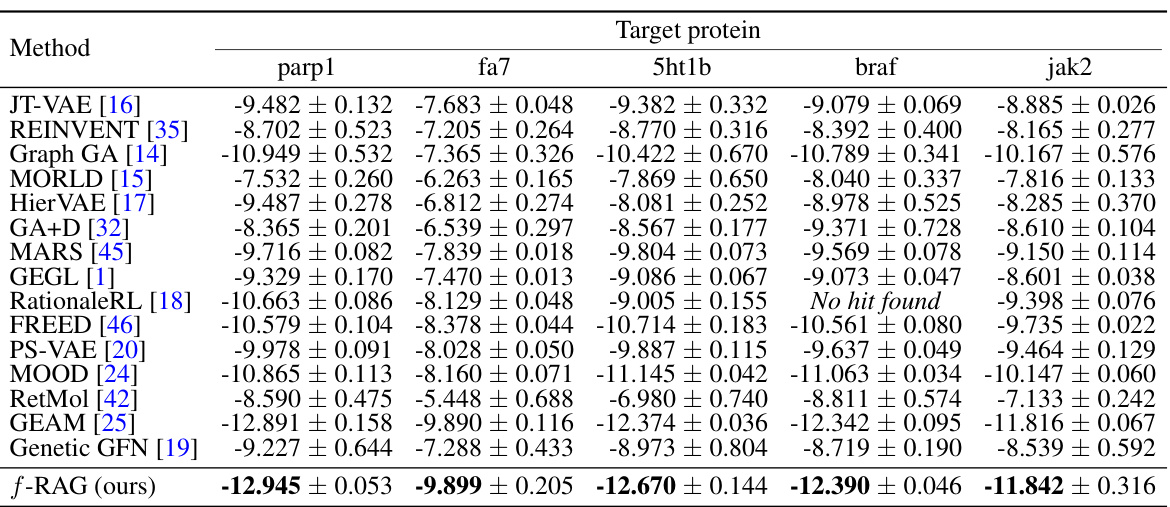

This table presents the results of experiments to optimize the binding affinity against five target proteins while considering drug-likeness and synthesizability. It compares the performance of the proposed f-RAG model against several baseline methods, showing the novel top 5% docking scores (in kcal/mol) for each target protein. Lower scores indicate better binding affinity.

This table presents the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the top 10 molecules’ average property scores versus the number of oracle calls for 23 tasks in the Practical Molecular Optimization (PMO) benchmark. It compares the performance of f-RAG against several state-of-the-art baselines, highlighting f-RAG’s superior performance in most tasks. The results include the mean and standard deviation for each method and task, and the best performance is bolded.

This table presents the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the top 10 molecules’ average property scores versus the number of oracle calls for 23 tasks in the Practical Molecular Optimization (PMO) benchmark. It compares the performance of f-RAG against several state-of-the-art methods. The best performing method for each task is highlighted in bold. The table shows f-RAG’s performance across a range of molecular optimization challenges.

This table presents the results of the seven multi-property optimization (MPO) tasks in the PMO benchmark. It compares the performance of f-RAG against several baseline methods including REINVENT, Graph GA, SELFIES-REINVENT, and GEAM. The AUC top-100 scores for each task are shown, indicating the area under the curve for the average property scores of the top 100 molecules versus oracle calls. The best-performing method for each task is highlighted in bold.

This table presents the results of the practical molecular optimization (PMO) benchmark, comparing the performance of f-RAG against several state-of-the-art methods. The AUC (Area Under the Curve) of the average property scores of the top-10 molecules versus the number of oracle calls is used as the primary metric for optimization performance. The table also includes results for diversity, novelty, and synthesizability, which are essential considerations in drug discovery.

This table compares the performance of f-RAG against several baselines on seven multi-property optimization (MPO) tasks from the PMO benchmark. The AUC (Area Under the Curve) top-100 metric is used to assess the optimization performance. f-RAG shows superior performance across all tasks.

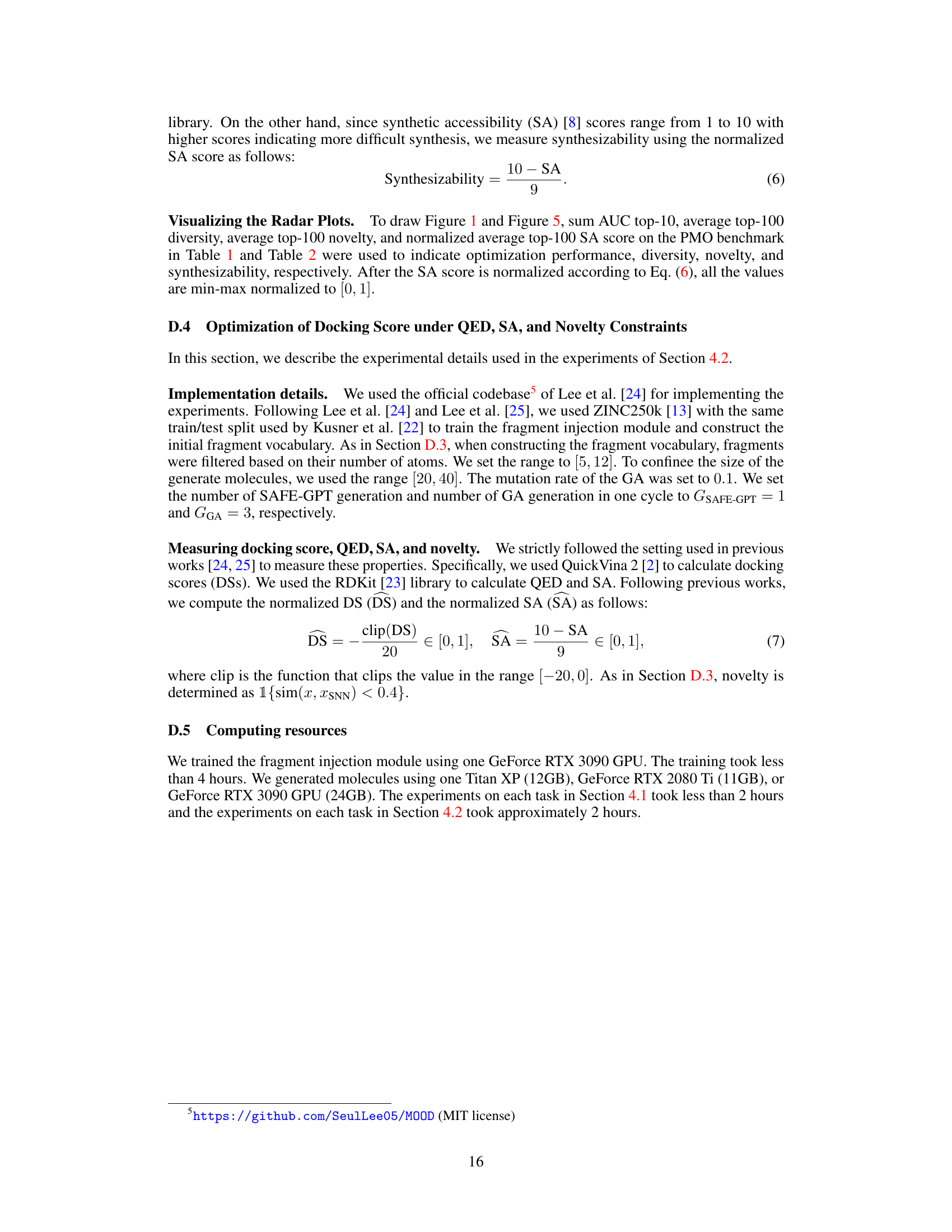

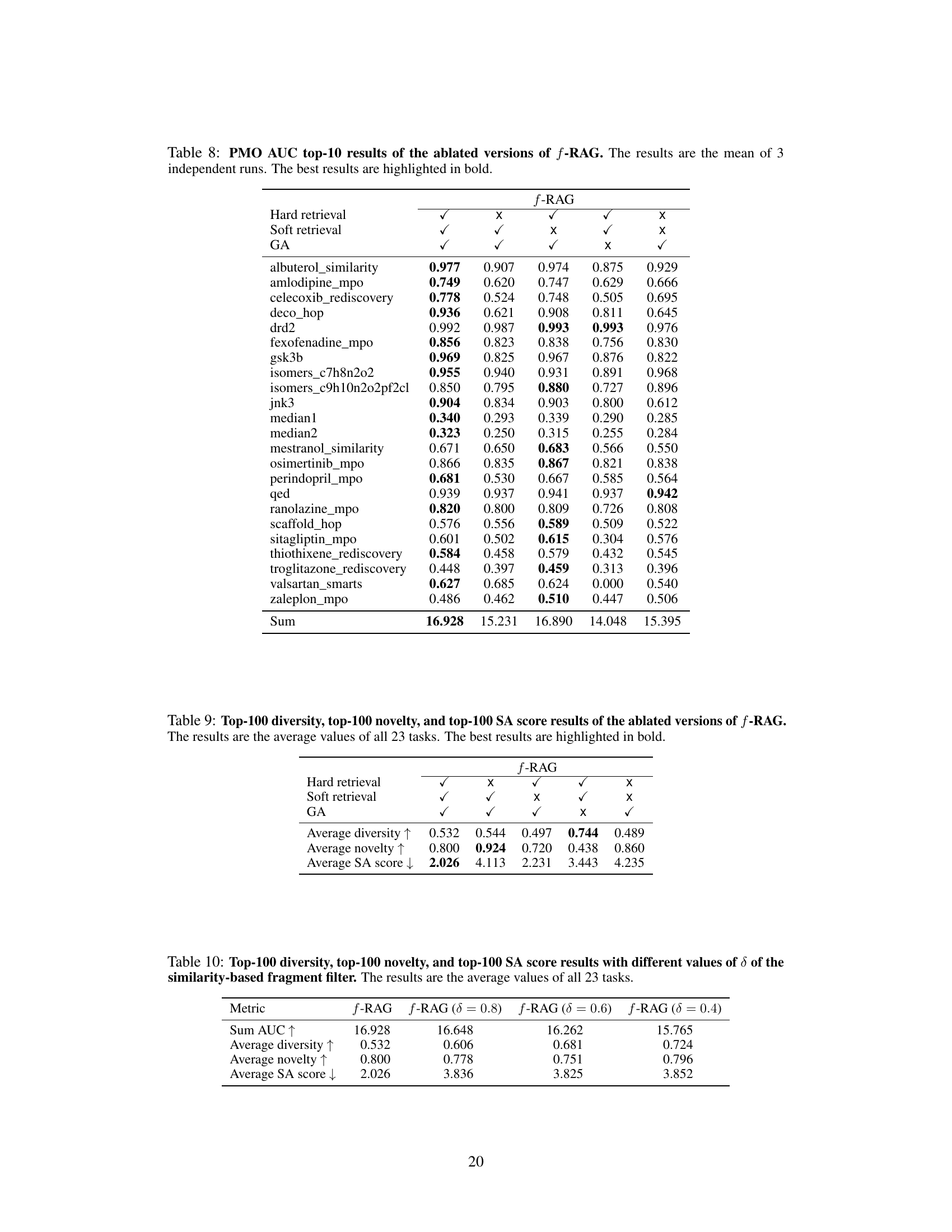

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the proposed f-RAG model. It shows the performance of f-RAG when different components are removed (hard fragment retrieval, soft fragment retrieval, and genetic algorithm). The AUC (Area Under the Curve) top-10 scores for 23 tasks from the Practical Molecular Optimization (PMO) benchmark are shown, allowing comparison of the effectiveness of each component. The best-performing configurations are highlighted.

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the f-RAG model. It shows the average diversity, novelty, and synthetic accessibility (SA) scores across 23 tasks from the PMO benchmark for five different versions of the model: the full f-RAG model, and four versions with one component removed (hard fragment retrieval, soft fragment retrieval, or genetic algorithm). The results highlight the contribution of each component to the overall performance.

This table presents the average diversity, novelty, and synthetic accessibility (SA) scores for the top 100 molecules generated by f-RAG using different thresholds (δ) for filtering similar fragments. A higher δ value means that more similar fragments are excluded during vocabulary updates, leading to increased diversity but potentially impacting optimization performance and SA scores. The results show how the similarity threshold influences the exploration-exploitation trade-off of the f-RAG model.

This table presents the results of an ablation study, comparing the performance of the f-RAG model with the fragment injection module placed at different layers (L=1 and L=6) of the SAFE-GPT model. The results show the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the top 10 molecules across 23 different tasks in the PMO benchmark. The table demonstrates the impact of the fragment injection module’s position on the overall performance, indicating the optimal layer for integration.

This table presents the results of novel top 5% docking score (kcal/mol) for five target proteins (parp1, fa7, 5ht1b, braf, and jak2). It compares the performance of f-RAG against several baselines, highlighting the mean and standard deviation of docking scores obtained from 3 independent runs. Lower scores indicate better performance. The table also notes the source of baseline results from Lee et al. [24,25].

Full paper#