↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) excel at generating text, but controlling their output to precisely match logical constraints remains a challenge. Existing methods struggle with reliability and scalability. This paper introduces Ctrl-G, a novel framework that combines LLMs with Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) to enforce these constraints, represented using deterministic finite automata (DFAs). This approach leverages the strengths of both neural and symbolic AI.

Ctrl-G shows significant improvements over existing techniques. In text editing tasks, Ctrl-G substantially outperforms even GPT-4. It also demonstrates superior performance in common constrained generation benchmarks. The HMM is efficiently conditioned on the DFA and adapts to complex constraints. Ctrl-G offers reliability and adaptability, extending the capabilities of LLMs to tasks requiring stringent logical control.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models (LLMs) because it offers a novel and effective method for controlling LLM outputs to meet logical constraints. It directly addresses the challenge of reliable constrained generation, a major bottleneck in many LLM applications. By providing a practical and adaptable framework (Ctrl-G), the research opens avenues for more reliable and sophisticated LLM applications that require strict adherence to rules and logic.

Visual Insights#

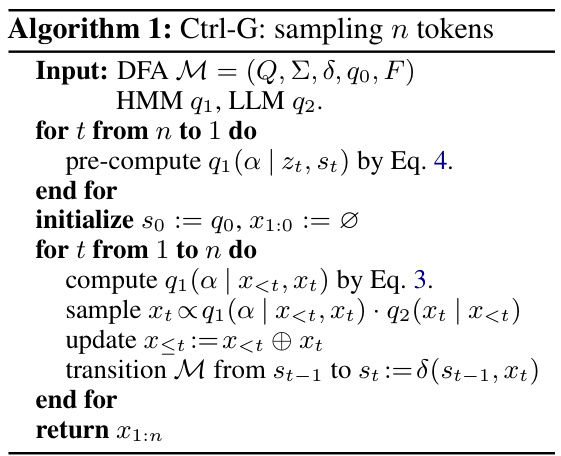

The figure illustrates the Ctrl-G pipeline, a three-step process. First, it distills a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) from a given Large Language Model (LLM). Second, it specifies the logical constraints using a Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA). Finally, during inference, the HMM guides the LLM to generate outputs that satisfy the constraints specified in the DFA. The LLM and HMM are both considered fixed after training.

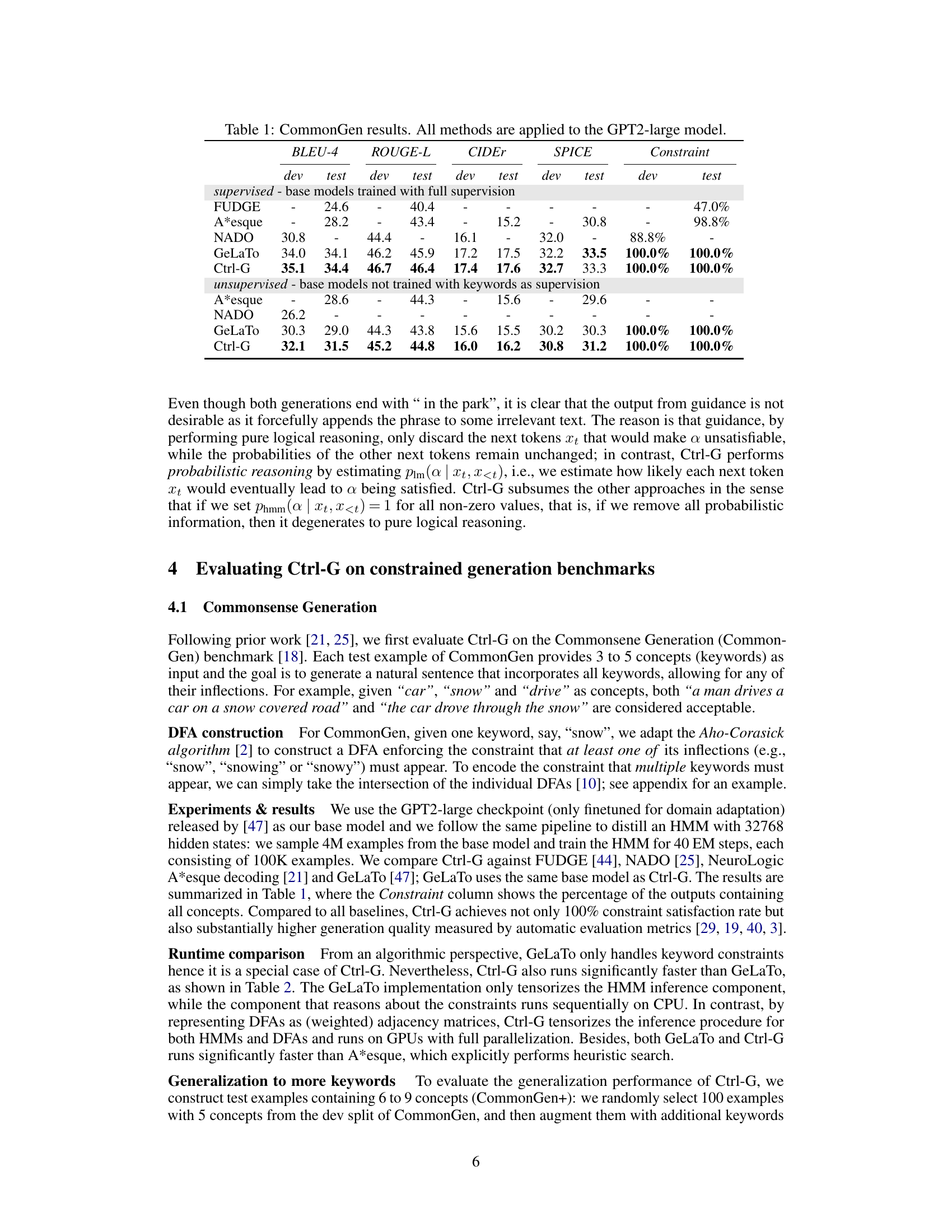

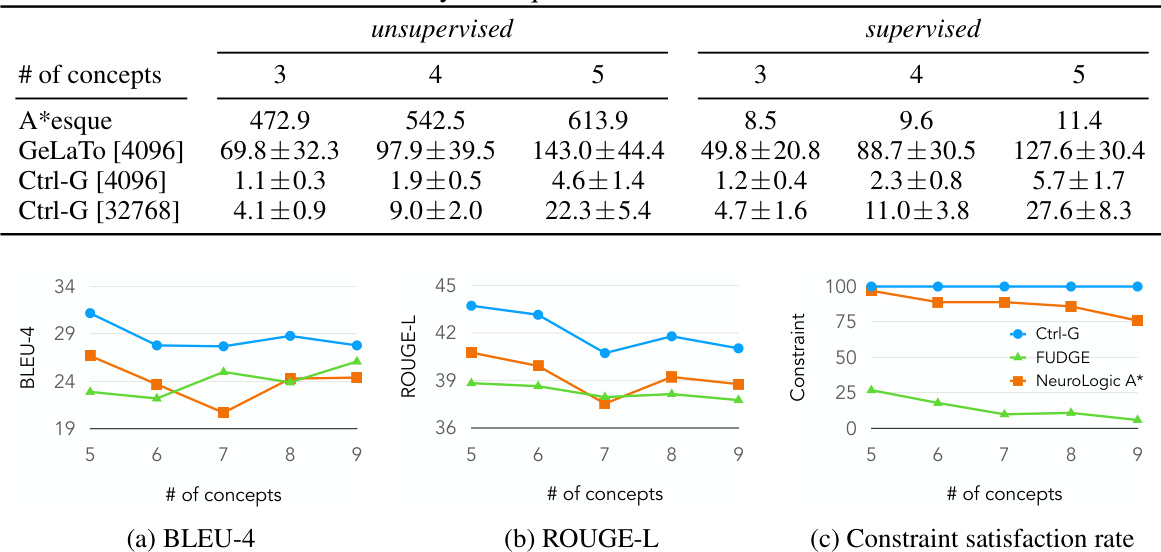

This table presents the results of the CommonGen experiment. The experiment evaluates several methods (FUDGE, A*esque, NADO, GeLaTo, and Ctrl-G) for generating text that includes specific keywords. The table shows the performance of these methods using BLEU-4, ROUGE-L, CIDEr, and SPICE metrics, comparing supervised and unsupervised approaches. It highlights Ctrl-G’s superior performance in achieving 100% constraint satisfaction.

In-depth insights#

Neuro-symbolic Ctrl-G#

A hypothetical ‘Neuro-symbolic Ctrl-G’ framework represents a significant advancement in controlling Large Language Models (LLMs). By integrating neuro (deep learning) and symbolic (rule-based) approaches, it aims to achieve reliable and adaptable control over LLM text generation, overcoming the challenge of enforcing strict constraints during inference. The ‘Ctrl-G’ likely refers to a system that guides the LLM’s output to adhere to specified logical constraints, perhaps represented as deterministic finite automata (DFAs). This neuro-symbolic fusion is crucial, leveraging the strengths of LLMs for fluency and creativity while using symbolic methods to ensure adherence to rules. Tractability and adaptability are key features, implying the framework can handle complex constraints efficiently and be applied to various tasks without extensive retraining. The success of such a system would depend heavily on the effectiveness of the integration between the neural and symbolic components, likely requiring sophisticated techniques like HMMs for guiding LLM generation probabilistically toward constraint satisfaction. Furthermore, evaluation would need to demonstrate improvements in both the quality of the generated text and the reliability of constraint fulfillment, compared to existing methods which often fail to satisfy logical constraints. In short, Neuro-symbolic Ctrl-G could mark a paradigm shift in constrained text generation, combining human-like fluency with rigorous logical control.

HMM-LLM Coupling#

Coupling Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) with Large Language Models (LLMs) offers a powerful approach to incorporating structured constraints into LLM generation. The HMM provides a tractable probabilistic framework for representing and enforcing these constraints, while the LLM provides the fluency and creativity of natural language generation. This synergy addresses a key limitation of LLMs: their difficulty in reliably adhering to strict logical or grammatical rules during inference. The HMM acts as a guide, probabilistically steering the LLM towards outputs that satisfy predefined constraints, encoded as a deterministic finite automaton (DFA). A crucial aspect is the distillation process, where an HMM is trained to approximate the behavior of a given LLM. This allows the HMM to effectively capture the LLM’s inherent biases and characteristics, facilitating smooth integration and accurate guidance. The framework’s adaptability is a significant advantage, allowing the same distilled HMM to be used with different constraints specified as DFAs, avoiding retraining for every new constraint. This approach enhances the overall reliability and controllability of LLM generation, making it more suitable for applications demanding strict adherence to rules and specifications.

Benchmark Results#

A dedicated ‘Benchmark Results’ section in a research paper would ideally present a detailed comparison of the proposed method against existing state-of-the-art techniques. This would involve selecting appropriate benchmarks relevant to the research problem, ensuring the chosen metrics accurately reflect the goals, and reporting results with clear error bars and statistical significance. A strong presentation would highlight both quantitative and qualitative improvements, comparing performance across multiple metrics, datasets, and varying experimental conditions. Visualizations like charts and tables are crucial for effectively communicating the results. Furthermore, a thoughtful analysis of the results is essential, discussing any unexpected findings, limitations, and potential reasons for performance differences. In-depth discussions comparing not only the final results but also aspects of the approach’s computational efficiency and resource requirements provide a holistic perspective. Overall, a robust ‘Benchmark Results’ section convincingly demonstrates the effectiveness and advantages of the proposed method, contributing significantly to the paper’s impact and credibility.

Scalable Text Editing#

Scalable text editing, in the context of large language models (LLMs), presents a significant challenge and opportunity. The ideal system would allow for seamless integration of human and AI contributions, offering flexible and nuanced control over the editing process. Adaptability is key, allowing users to specify complex constraints such as keyword inclusion, length limitations, or stylistic preferences. A truly scalable solution must also address the computational demands of processing and generating text at speed and scale, handling diverse input formats and user preferences. The key to success lies in finding the right balance between the power of LLMs and the precision of formal methods, such as deterministic finite automata or similar constraint representation techniques. This blend will enable more robust, efficient, and user-friendly text editing tools, applicable across numerous contexts like document revision, creative writing, or code generation. Furthermore, guaranteeing constraint satisfaction is crucial; simply prompting an LLM is insufficient due to their probabilistic nature. A robust architecture would incorporate techniques to ensure that logical constraints are always met, while maintaining high-quality and fluent output. The scalability aspect, therefore, hinges not only on efficient algorithms but also on the ability to handle complex constraint combinations effectively.

Future of Ctrl-G#

The future of Ctrl-G hinges on addressing its current limitations and expanding its capabilities. Scalability to even larger LLMs is crucial; while the paper demonstrates success with 7B parameter models, extending its efficacy to models with hundreds of billions of parameters is a key challenge. Furthermore, developing more efficient algorithms for handling complex DFAs and HMMs is needed to maintain reasonable inference times. Expanding the range of expressible constraints beyond DFAs, perhaps through more expressive formalisms like probabilistic logic programs, would significantly enhance Ctrl-G’s flexibility and applicability. Research into automatic DFA generation from natural language descriptions of constraints would improve usability and accessibility. Finally, exploration of Ctrl-G in diverse applications beyond text editing, including areas like code generation, reasoning tasks, and multi-modal generation, represents a promising avenue for future work. Integrating Ctrl-G with other LLM control techniques, such as reinforcement learning or prompt engineering, could yield even more powerful and adaptable control mechanisms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the three main steps of the Ctrl-G pipeline for controlling LLM generation to satisfy logical constraints. First, the LLM is distilled into a Hidden Markov Model (HMM). Second, the logical constraints are specified using a deterministic finite automaton (DFA). Finally, during inference, the HMM guides the LLM’s generation to adhere to the DFA-specified constraints, resulting in outputs that satisfy the constraints. Both the LLM and the HMM are trained beforehand and are frozen during inference.

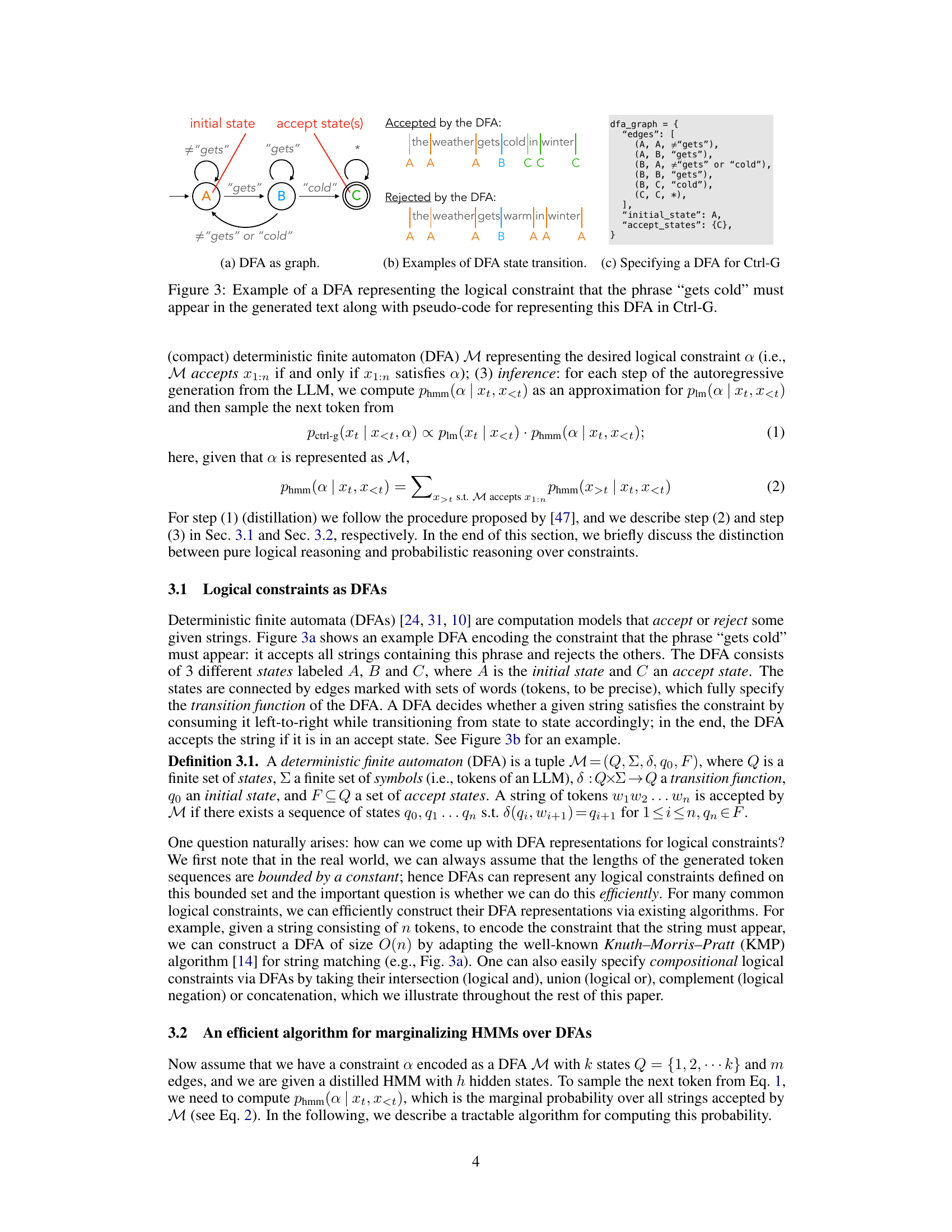

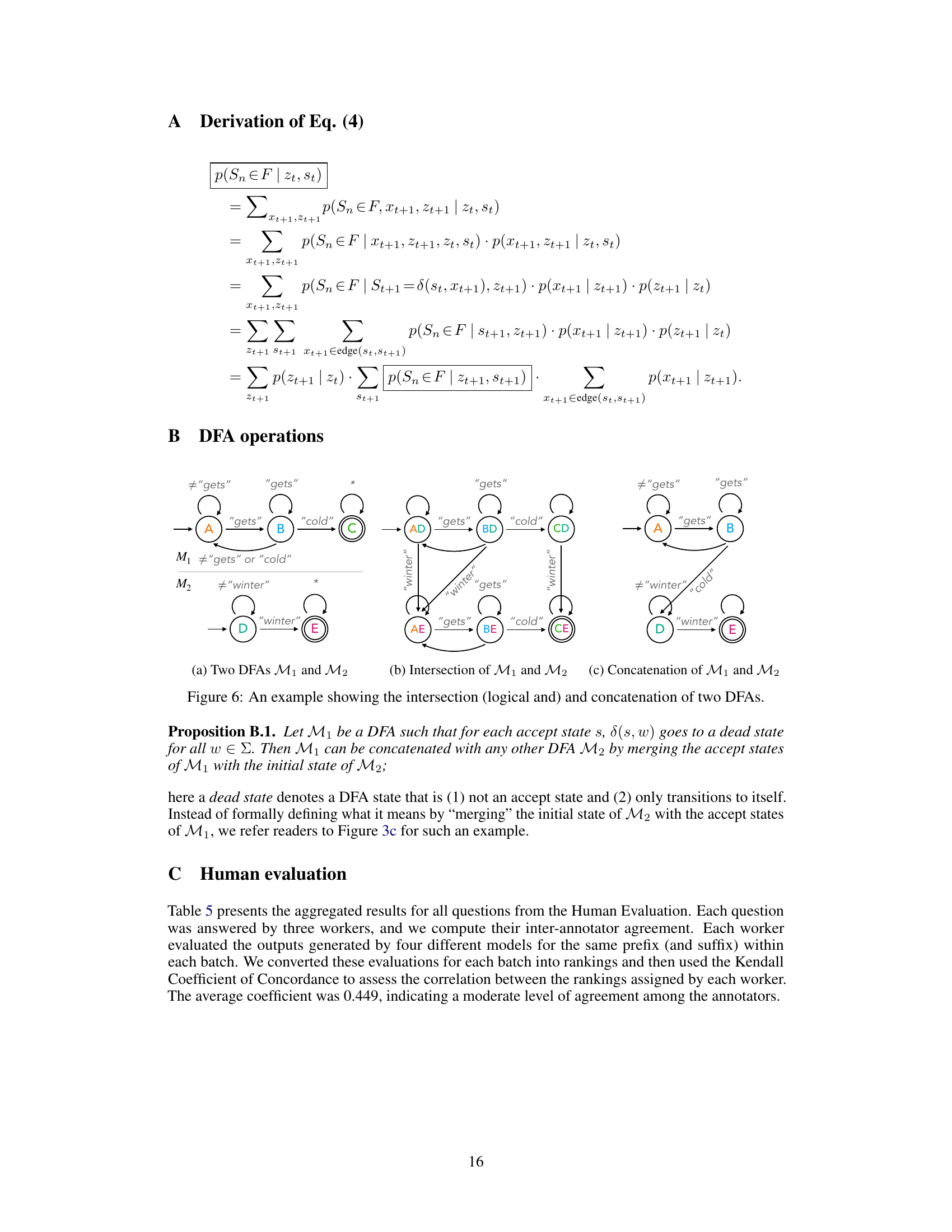

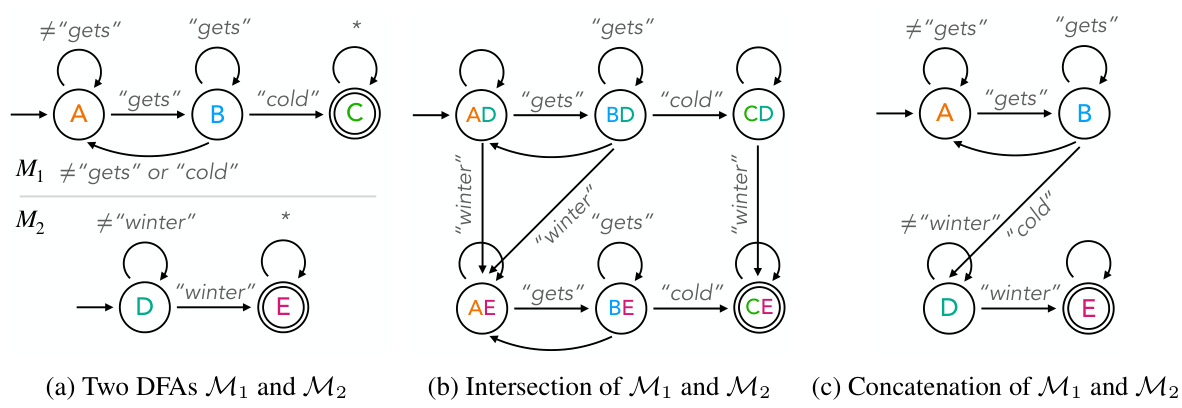

This figure shows an example of a Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA) used to represent a logical constraint in the Ctrl-G framework. The DFA in (a) is a graph representation of the automaton, illustrating its states (A, B, C), transitions (edges with conditions on words like ‘gets’, ‘cold’, etc.), the initial state (A), and accepting state (C). (b) demonstrates the DFA’s behavior with sample strings. The string ’the weather gets cold in winter’ is accepted because it contains the phrase ‘gets cold’, while ’the weather gets warm in winter’ is rejected, as it lacks the specific phrase. (c) provides Python code illustrating how to specify this DFA in the Ctrl-G system, showing the structure as a dictionary including transitions, initial and accepting states.

This figure illustrates the three main steps of the Ctrl-G pipeline for controllable text generation. First, an LLM (Large Language Model) is combined with a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) which is a white-box approximation of the LLM. This HMM guides the LLM’s output to meet specified constraints. These constraints are defined by a Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA). The DFA is then used during the inference phase to guide the LLM’s generation towards outputs that satisfy the given logical constraints. Once the LLM and HMM are trained, they remain frozen during inference.

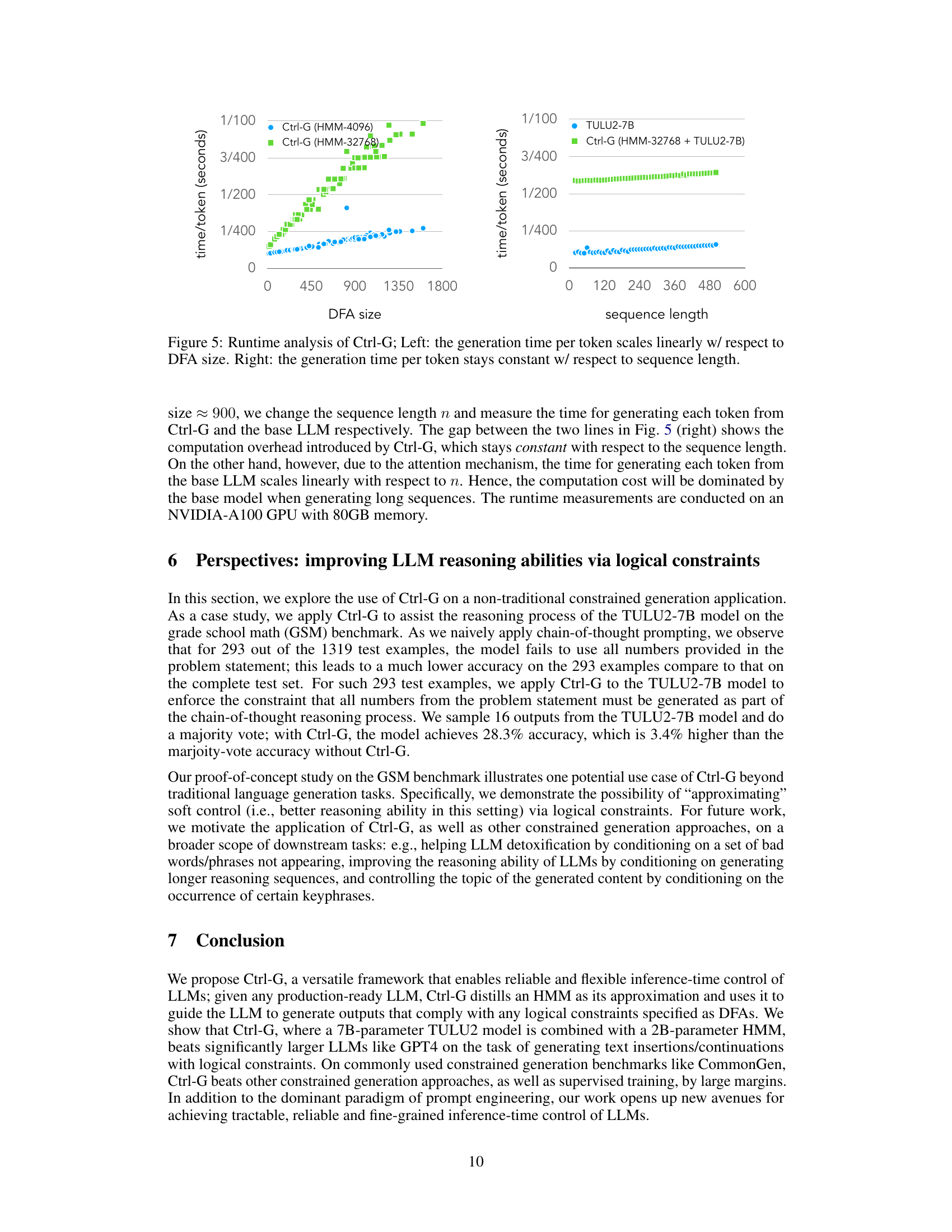

This figure presents the results of a runtime analysis of the Ctrl-G model. The left panel shows a linear relationship between the generation time per token and the size of the Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA) used to represent logical constraints. This suggests that the computational cost of constraint enforcement in Ctrl-G increases proportionally with the complexity of the constraints. The right panel demonstrates that the generation time per token remains relatively constant regardless of sequence length. This indicates that the overhead introduced by Ctrl-G does not scale significantly with the length of the text being generated.

This figure illustrates an example of a Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA) used to represent logical constraints in the Ctrl-G framework. The DFA shown is designed to accept strings containing the phrase ‘gets cold.’ The figure depicts the DFA as a graph with states (A, B, C) and transitions, clearly showing how the DFA processes input strings to determine if the constraint (‘gets cold’) is satisfied. Pseudo-code is included to demonstrate how such a DFA can be specified within the Ctrl-G system. This is a key component of how Ctrl-G translates logical constraints into a form usable by the HMM and LLM for controlled text generation.

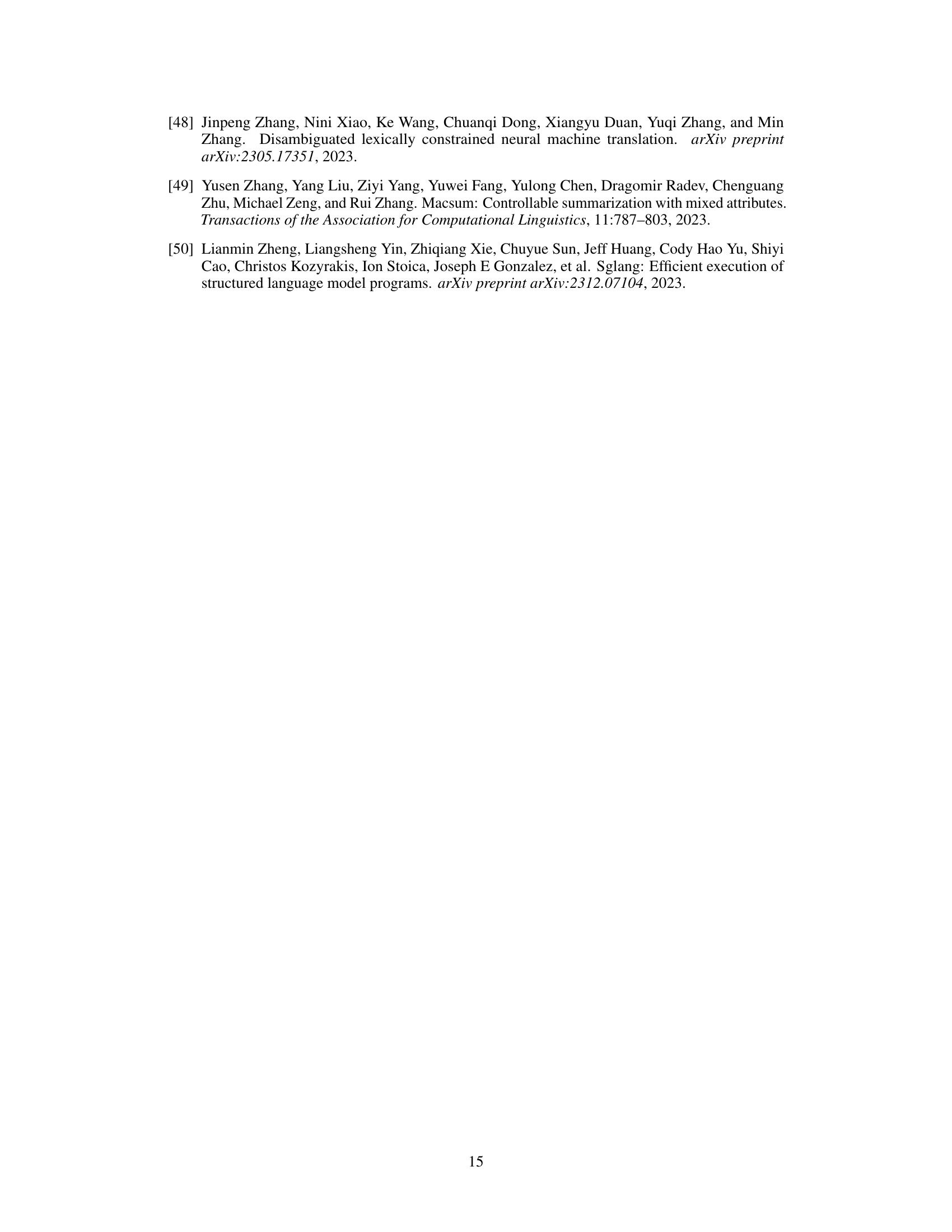

More on tables

This table presents the results of the CommonGen experiment, comparing various methods (FUDGE, A*esque, NADO, GeLaTo, and Ctrl-G) on two versions of the GPT2-large model: one trained with full supervision and one not trained with keywords. The metrics used are BLEU-4, ROUGE-L, CIDEr, SPICE, and the constraint satisfaction rate. Ctrl-G demonstrates superior performance in terms of both generation quality and constraint satisfaction.

This table presents the results of text infilling experiments using different LLMs. It shows the BLEU-4 and ROUGE-L scores achieved by both the ILM model (a baseline model trained with full supervision) and the proposed Ctrl-G model. Different masking ratios (13%, 21%, 32%, and 40%) are applied to the test data to evaluate the performance of both LLMs in handling different levels of text missingness. The ‘diff.’ row highlights the difference in performance between Ctrl-G and the ILM model at each masking ratio.

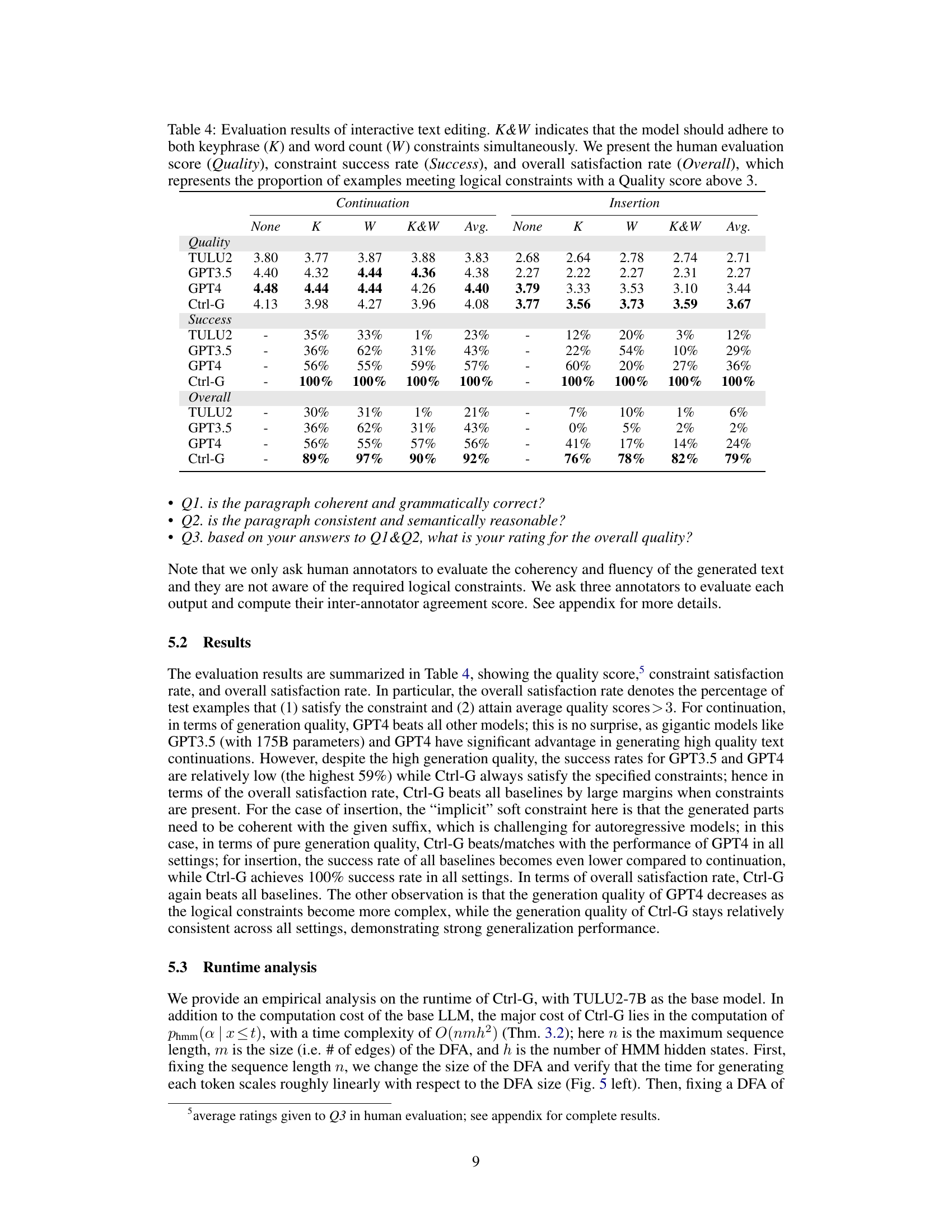

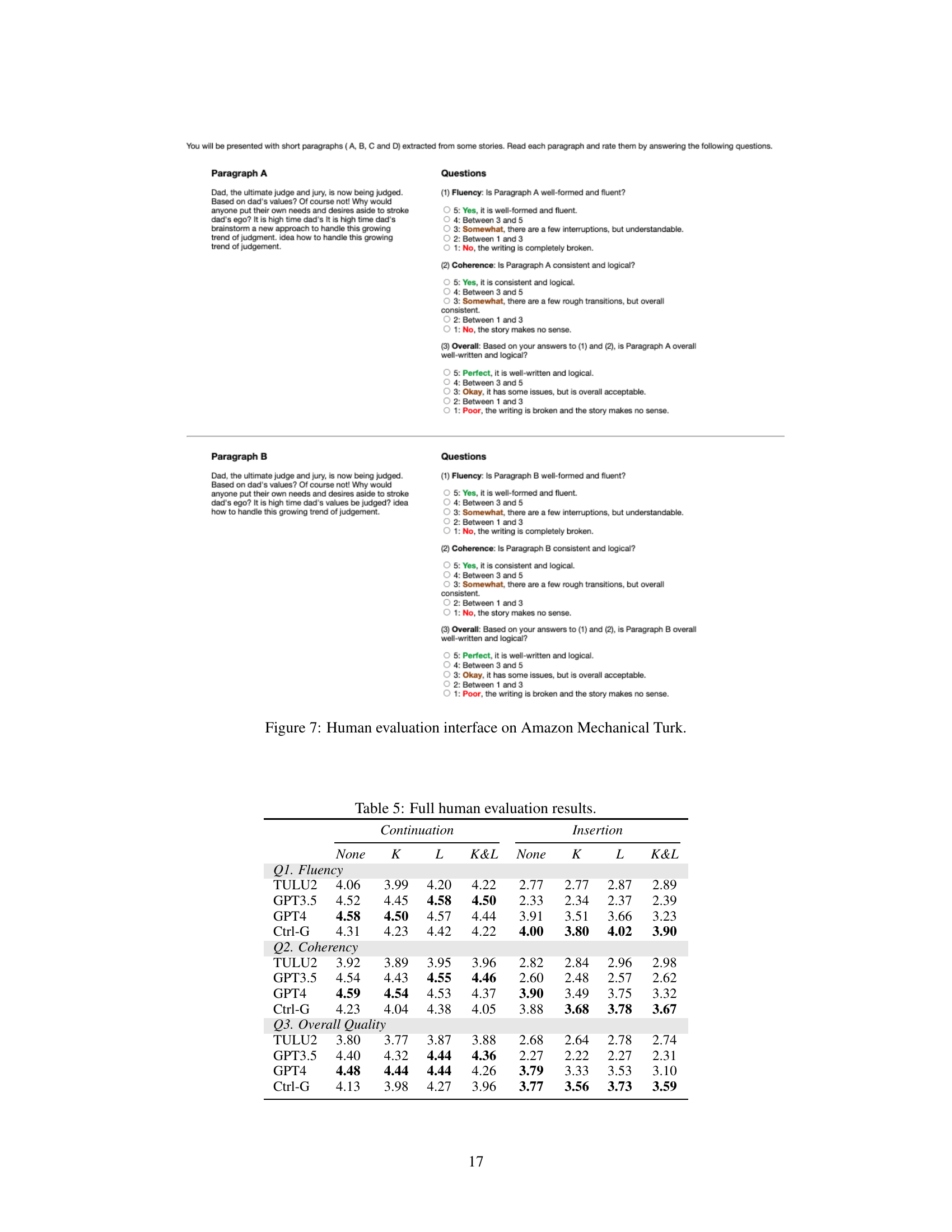

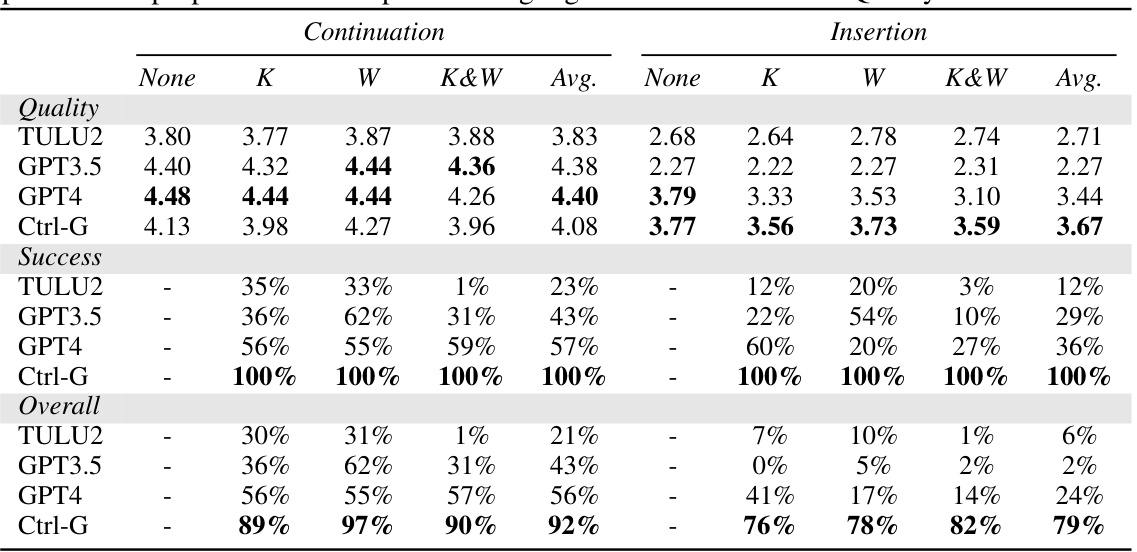

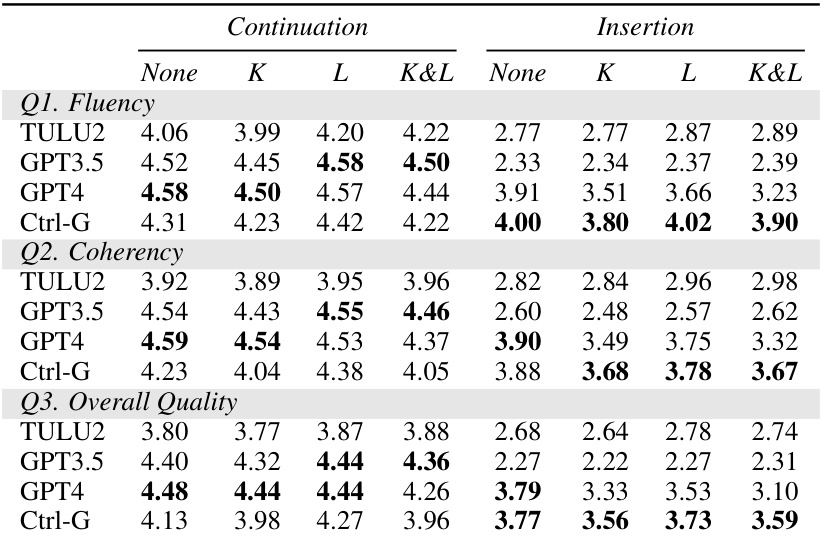

This table presents the results of a human evaluation comparing different LLMs’ performance on interactive text editing tasks. The models were evaluated on their ability to generate text continuations and insertions while adhering to keyphrase and word count constraints. The metrics used are Quality (average human rating), Success rate (percentage of successful constraint satisfaction), and Overall satisfaction rate (percentage of text that meets quality and constraint criteria).

This table presents the results of the CommonGen experiment using the GPT2-large model. It compares several methods (FUDGE, A*esque, NADO, GeLaTo, and Ctrl-G) across different metrics, including BLEU-4, ROUGE-L, CIDEr, and SPICE, both for supervised and unsupervised scenarios. The ‘Constraint’ column indicates the constraint satisfaction rate. The results showcase Ctrl-G’s superior performance compared to existing methods in terms of constraint satisfaction and text generation quality.

Full paper#