↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Episodic memory, crucial for remembering specific events, is often modeled using associative memory. However, Neural Episodic Control (NEC), a powerful reinforcement learning framework, uses a differentiable dictionary for memory, lacking a direct theoretical link to established associative memory models. This poses challenges in understanding its functioning and improving its efficiency. The lack of a clear theoretical connection between NEC’s dictionary and traditional associative memory models hinders understanding its performance and optimization.

This paper addresses this by demonstrating that NEC’s dictionary is an instance of the recently introduced Universal Hopfield Network (UHN) framework. The authors propose two novel energy functions for NEC’s dictionary readout and empirically show its improved performance over existing Max separation functions. They also highlight that using a Manhattan distance kernel instead of Euclidean improves performance. Furthermore, they introduce a novel criterion to evaluate associative memory by separating memorization and generalization, addressing a key limitation in the existing evaluation methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it bridges the gap between reinforcement learning and associative memory, potentially leading to more efficient controllers and memory models for AI systems. It also offers a novel criterion for evaluating associative memory, disentangling memorization from generalization. Furthermore, the findings suggest that replacing the Euclidean distance kernel with a Manhattan distance kernel could improve performance, opening up new avenues for research in both fields.

Visual Insights#

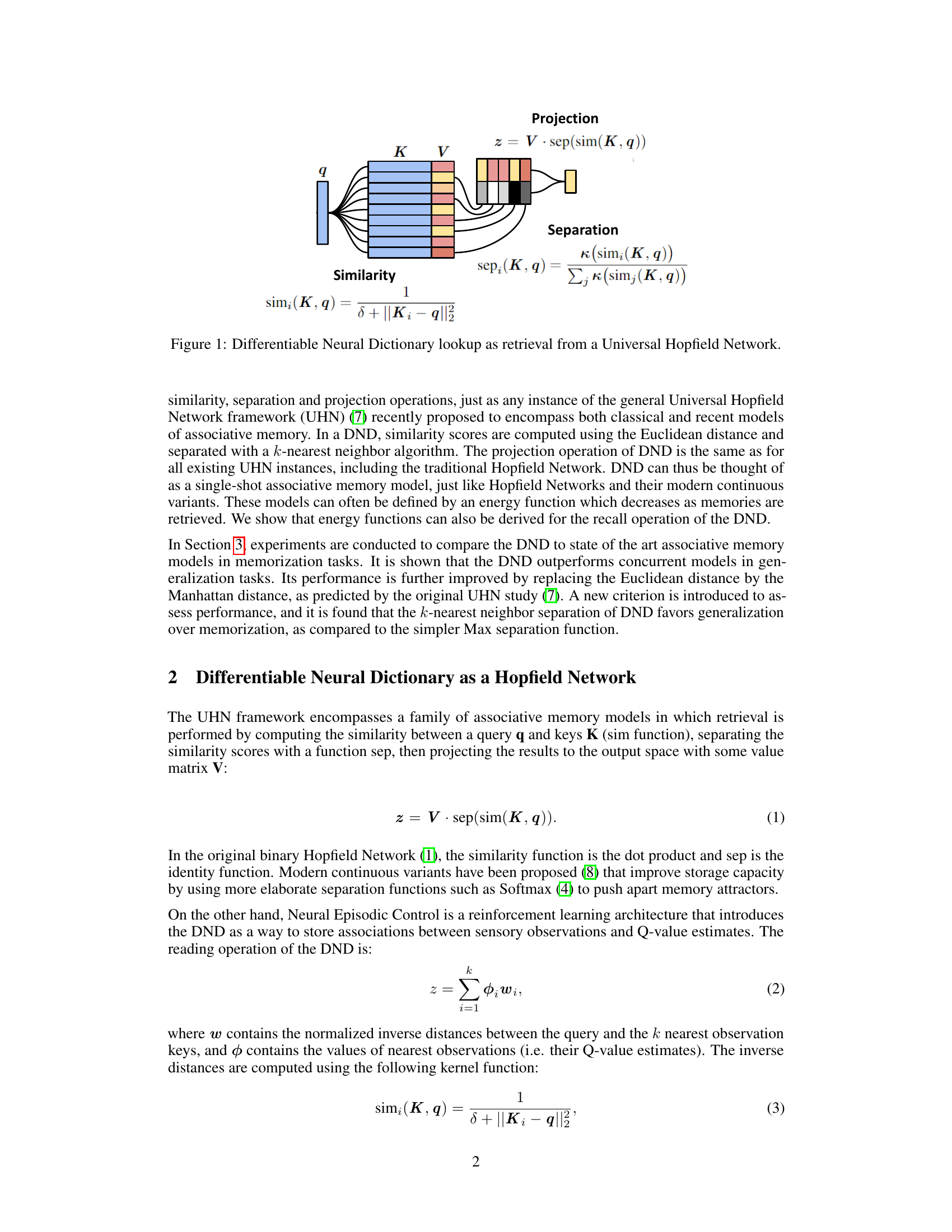

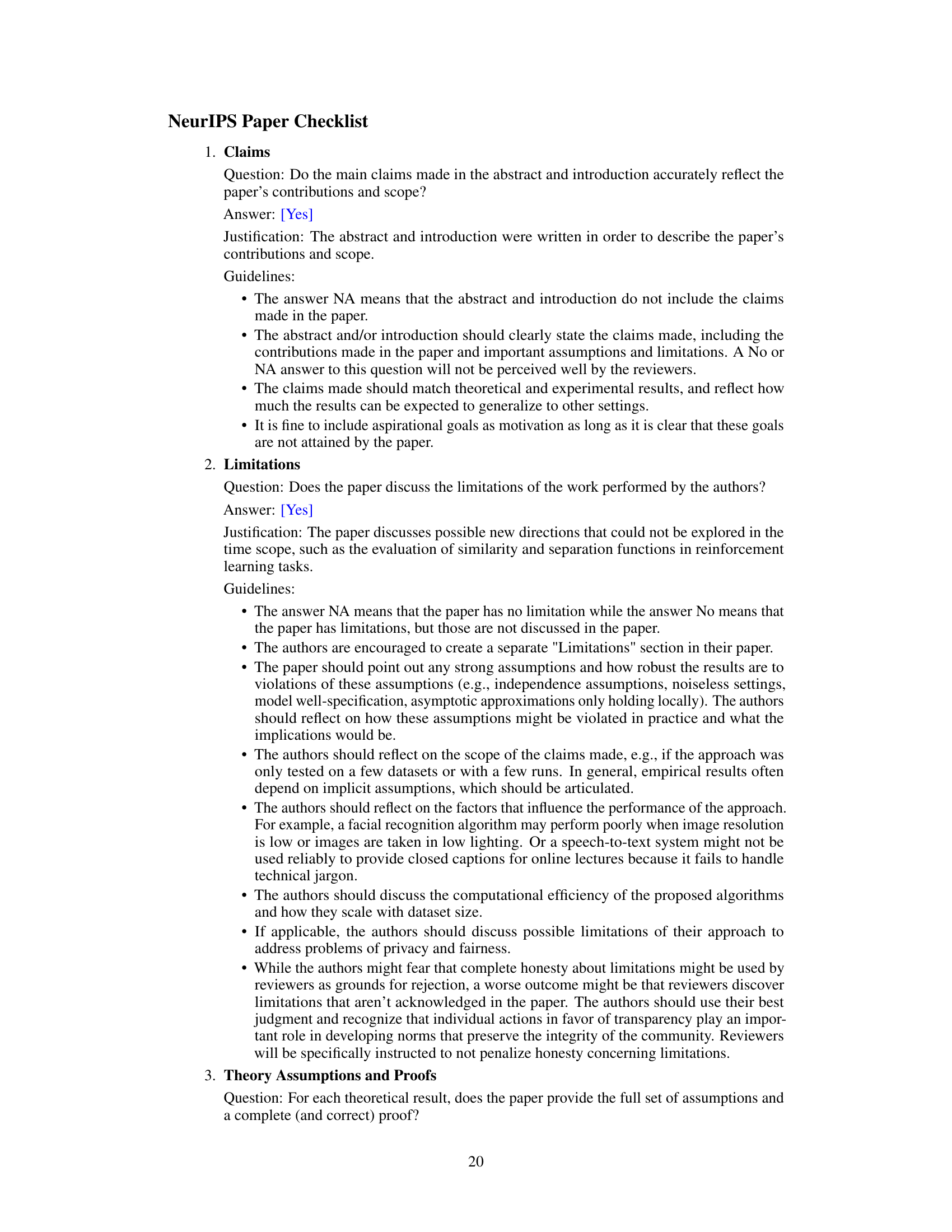

This figure illustrates the process of retrieving information from a Differentiable Neural Dictionary (DND) by relating it to the framework of a Universal Hopfield Network (UHN). It shows how the DND’s operation can be decomposed into three key steps, which are common to many associative memory models. First, the input query (‘q’) is compared to a set of stored keys (‘K’) using a similarity function, which calculates the distance between the query and each key. Then, the separation function selects a subset of the keys based on their similarity to the query (using k-nearest neighbors), effectively filtering out less relevant information. Finally, the selected information is projected into the output space (‘z’) using a projection matrix (‘V’), yielding the final retrieved result. This figure highlights the mathematical connection between DND and UHN, demonstrating that DND can be viewed as a specific instance of a broader class of associative memory models.

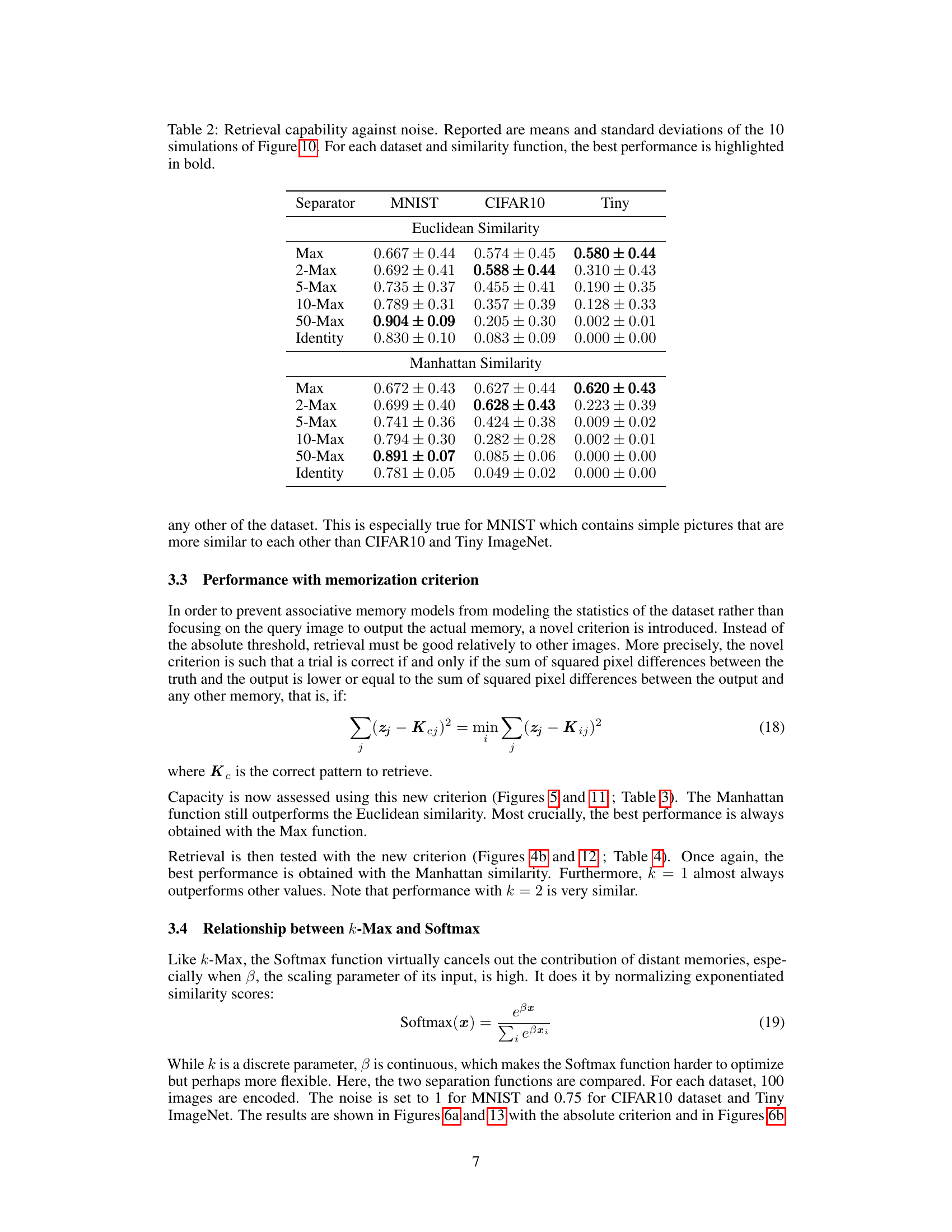

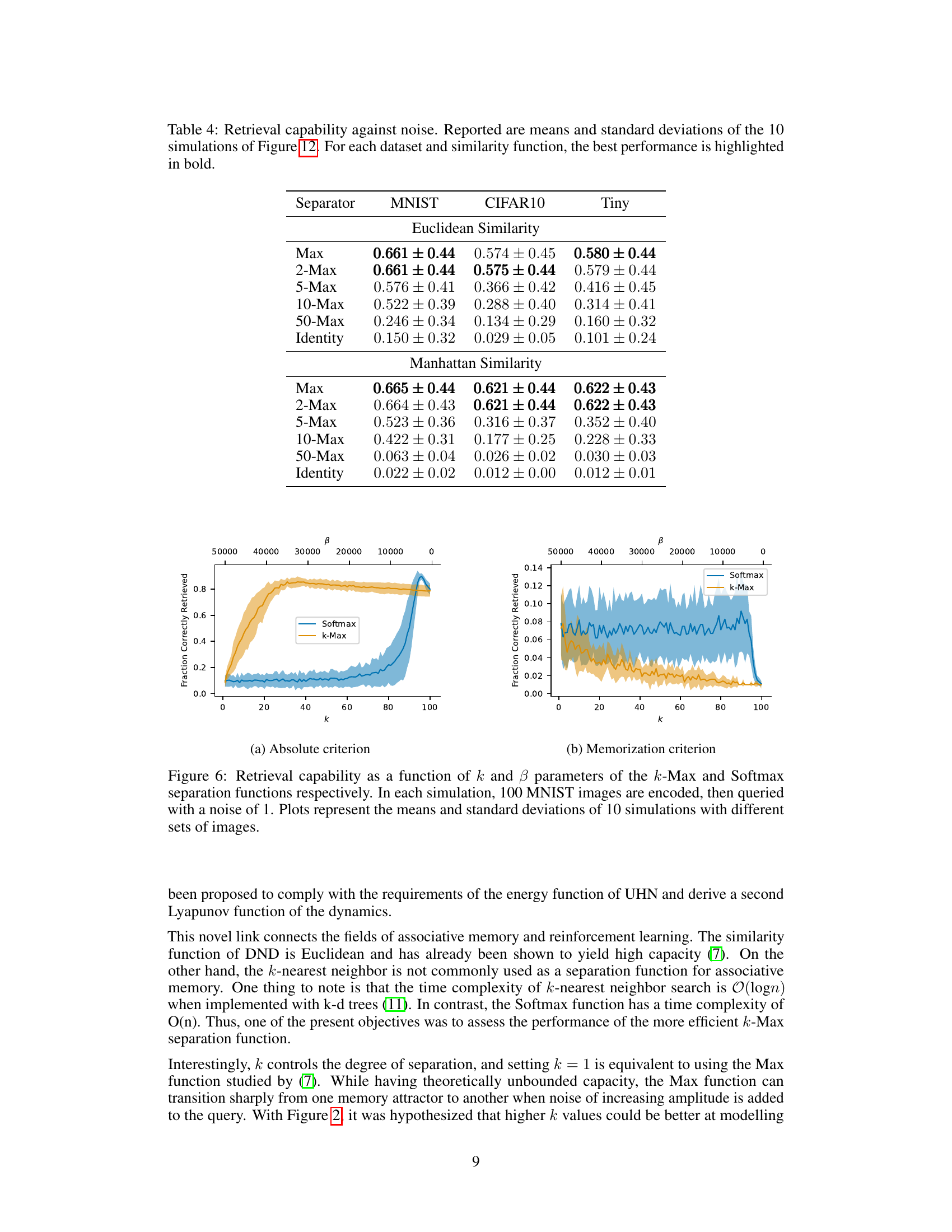

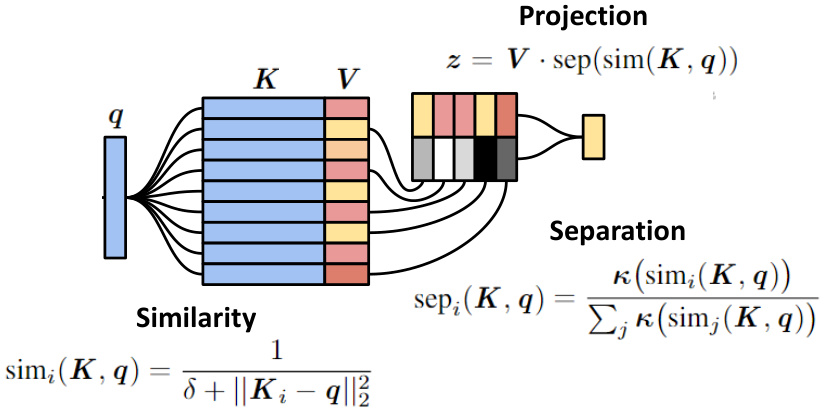

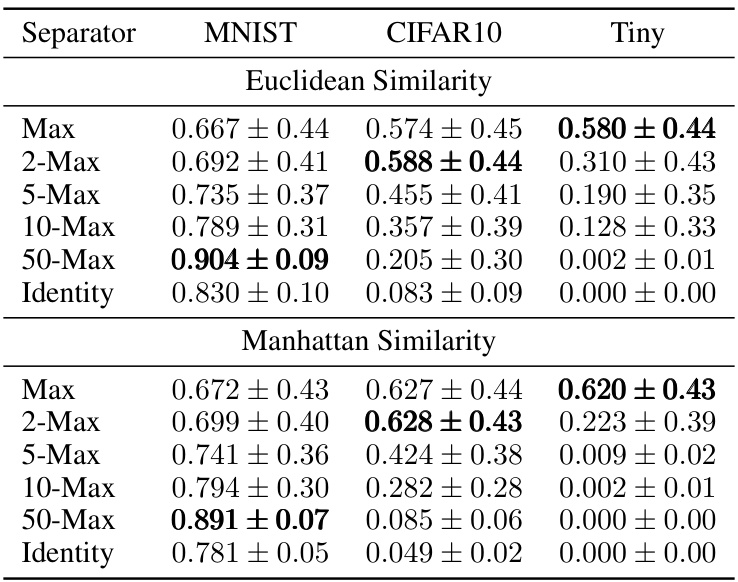

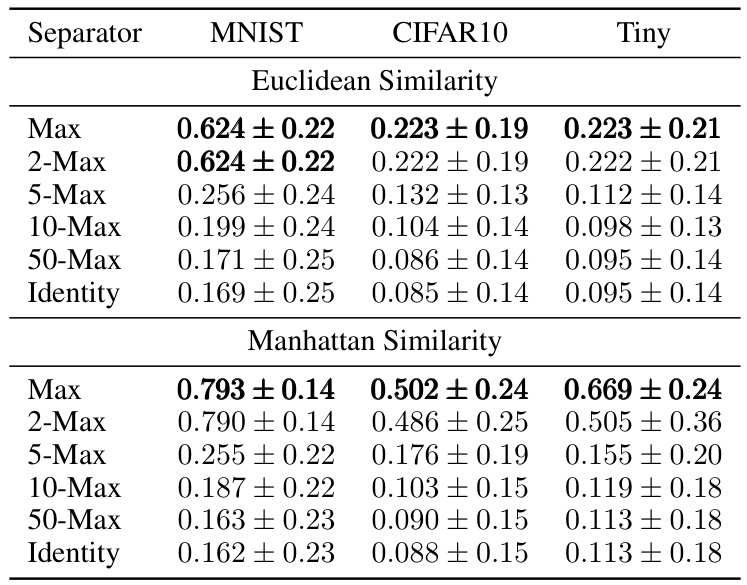

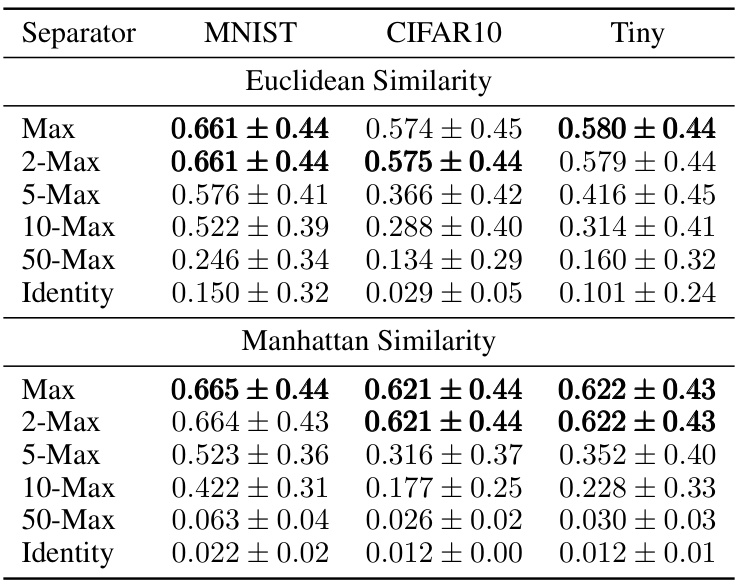

This table shows the capacity of associative memory models with different similarity (Euclidean and Manhattan) and separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, Identity) on three different datasets: MNIST, CIFAR10, and Tiny ImageNet. The capacity is measured by the percentage of correctly retrieved images when increasing the number of stored images. The best performing function for each dataset and similarity is highlighted in bold.

In-depth insights#

Hopfield & Control#

The intersection of Hopfield networks and control systems presents a fertile ground for research. Hopfield networks, with their inherent associative memory capabilities, offer a unique approach to designing controllers. By representing control strategies as patterns stored in the network’s memory, one can achieve rapid adaptation and learning. The connection to episodic control, where past experiences are stored and retrieved to guide future actions, is particularly compelling. This approach allows for a more nuanced and adaptive control mechanism that goes beyond the limitations of traditional controllers based on predefined rules. A key challenge in this area is exploring how to balance memorization and generalization in the network, to prevent overfitting to specific scenarios and ensure robust performance in unseen conditions. Investigating different kernel functions, such as the Manhattan distance as suggested in the paper, is essential for optimizing retrieval accuracy and generalization performance. The differentiable neural dictionary (DND), shown to be mathematically close to the Hopfield network, enables the use of gradient-based optimization techniques, making the approach more tractable. Furthermore, exploring how the dynamics of the Hopfield network translate to the control system’s behaviour is crucial. This integration of associative memory and control systems could lead to significant advancements in robotics, autonomous systems, and other fields where adaptive control is desired.

DND Energy#

The concept of ‘DND Energy’ in the context of a differentiable neural dictionary (DND) within a neural episodic control framework is intriguing. It suggests a potential for analyzing the DND’s retrieval process through the lens of energy-based models. By formulating an energy function for the DND, we can potentially gain insights into the stability and convergence properties of the memory retrieval dynamics. The existence of a Lyapunov function, as hinted at in the paper, would further support the use of energy-based analysis. This energy function could provide a quantitative measure of the DND’s performance in terms of both memorization and generalization, potentially providing a novel evaluation metric. The relationship between different kernel functions (Euclidean vs. Manhattan distance) and the resulting energy landscape needs further investigation. This could reveal fundamental aspects about how different similarity measures affect the retrieval process and its stability. Finally, exploring the connection between this energy-based perspective and the established theoretical framework of Universal Hopfield Networks (UHN) could pave the way for deeper understanding of DND and similar associative memory models. The development of a continuous approximation of the DND readout operation is a crucial step for developing a rigorous energy-based model. This mathematical framework is essential to precisely analyze the DND’s behaviour and potentially improve its performance through the design of optimized energy functions and parameters.

Memory Metrics#

In evaluating associative memory models, robust memory metrics are crucial for a comprehensive assessment. Traditional metrics often focus on absolute accuracy, measuring the difference between the model’s output and the target memory. While useful, this approach may overlook the model’s ability to disentangle memorization from generalization. A more nuanced metric would consider how the model’s output compares to other stored memories, assessing its capacity to recall specific information rather than simply reproducing dataset statistics. This is particularly relevant for tasks where memorizing unique episodes is critical, such as in episodic control. Therefore, a combined approach is advisable, using both absolute accuracy measures and metrics focused on the relative distinction between recalled memories and other stored items. By considering these distinct aspects of memory performance—absolute fidelity and relative uniqueness—we can gain a richer understanding of a model’s ability to not only accurately recall information but also to retrieve the precise memory relevant to the context.

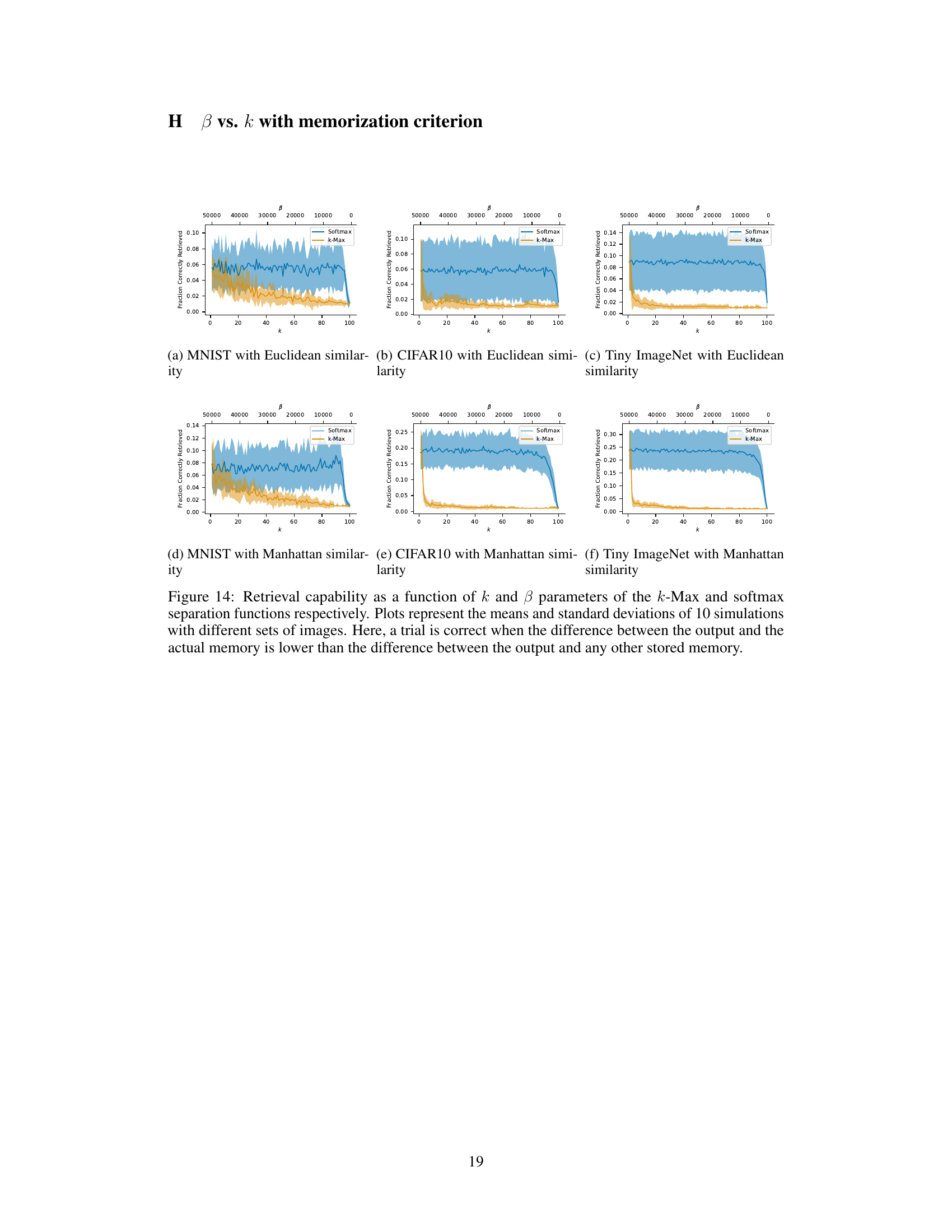

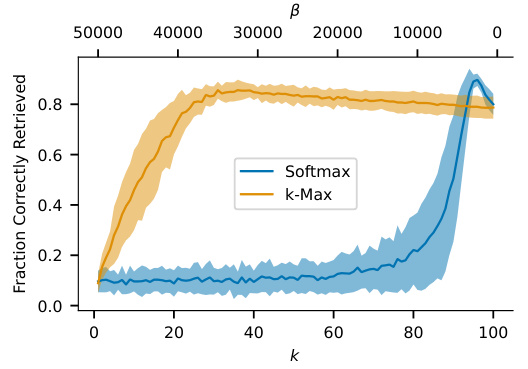

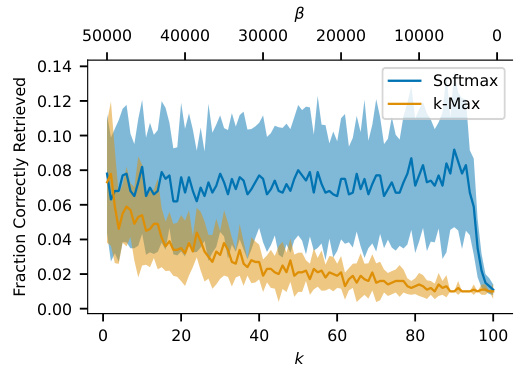

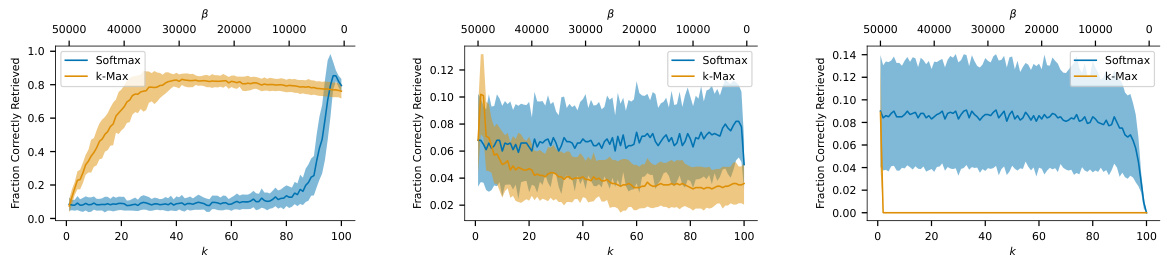

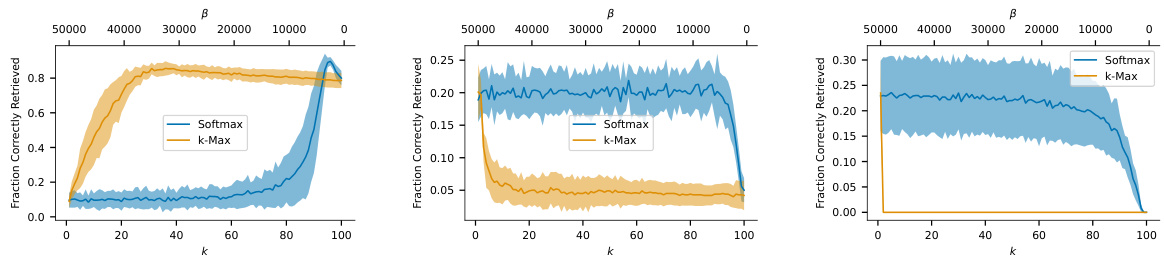

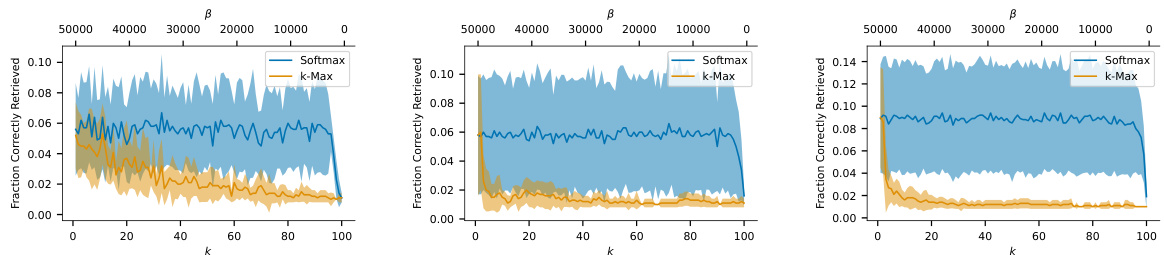

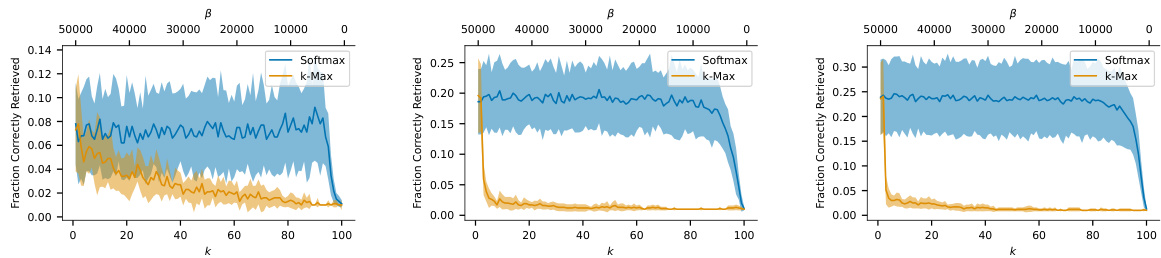

k-Max vs Softmax#

The comparative analysis of k-Max and Softmax separation functions reveals crucial insights into associative memory models. k-Max, a k-nearest neighbor approach, offers a discrete, computationally efficient method, favoring generalization by incorporating multiple similar memories. In contrast, Softmax, a continuous function, provides a potentially more flexible mechanism but comes at a higher computational cost. The choice between them hinges on the desired balance between speed and flexibility. Empirical results indicate that k-Max often excels in memorization tasks, particularly when using the Manhattan distance kernel, while Softmax may demonstrate superior performance with absolute accuracy criteria in datasets containing complex, high-dimensional data where nuanced discrimination between similar memories is essential. This highlights that optimal performance depends on the specific application and the nature of the data. Further research should explore the interplay between kernel functions, separation functions, and dataset characteristics to provide comprehensive guidelines for selecting the appropriate function for various associative memory applications.

Future Work#

The ‘Future Work’ section of this research paper presents exciting avenues for extending the current findings. A key area is exploring the application of Universal Hopfield Networks (UHN) to reinforcement learning tasks. This builds directly upon the paper’s core finding that the Differentiable Neural Dictionary (DND) is a specific instance of the UHN framework. Investigating the performance of various similarity (Euclidean, Manhattan, etc.) and separation (k-Max, Softmax) functions within reinforcement learning contexts, particularly their impact on sample efficiency, is crucial. The use of the Softmax function, shown to be superior in certain scenarios, warrants further investigation. This could lead to significant improvements in episodic control agents. Furthermore, connecting the theoretical findings to the biological mechanisms of the hippocampus, which also utilizes associative memory, is a promising direction for future research. This interdisciplinary approach could lead to both theoretical advancements in the understanding of associative memory and potentially more efficient and biologically inspired control algorithms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

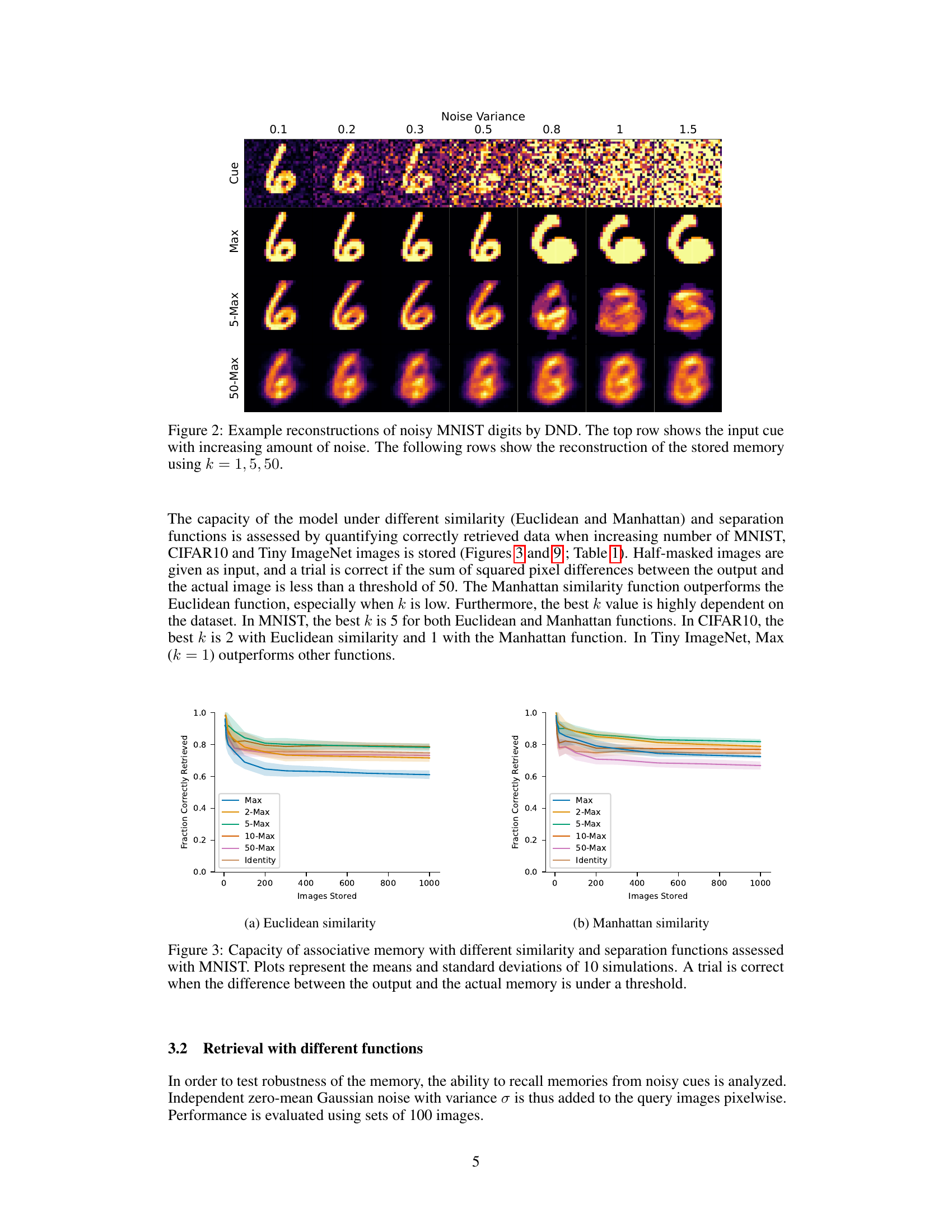

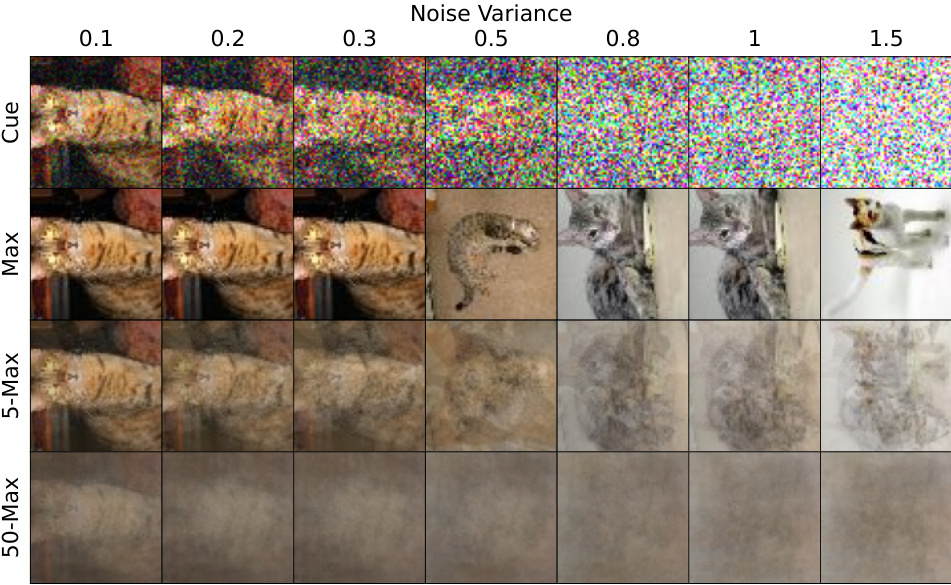

This figure shows example reconstructions of noisy MNIST digits using the Differentiable Neural Dictionary (DND). The top row displays the input cues, which are MNIST digits with increasing levels of added noise. The subsequent rows illustrate the DND’s reconstruction of the stored memories corresponding to these noisy inputs, using three different values of k (the number of nearest neighbors considered during retrieval): k=1 (Max), k=5, and k=50. The results demonstrate the impact of the k parameter on the quality of reconstruction and noise resilience.

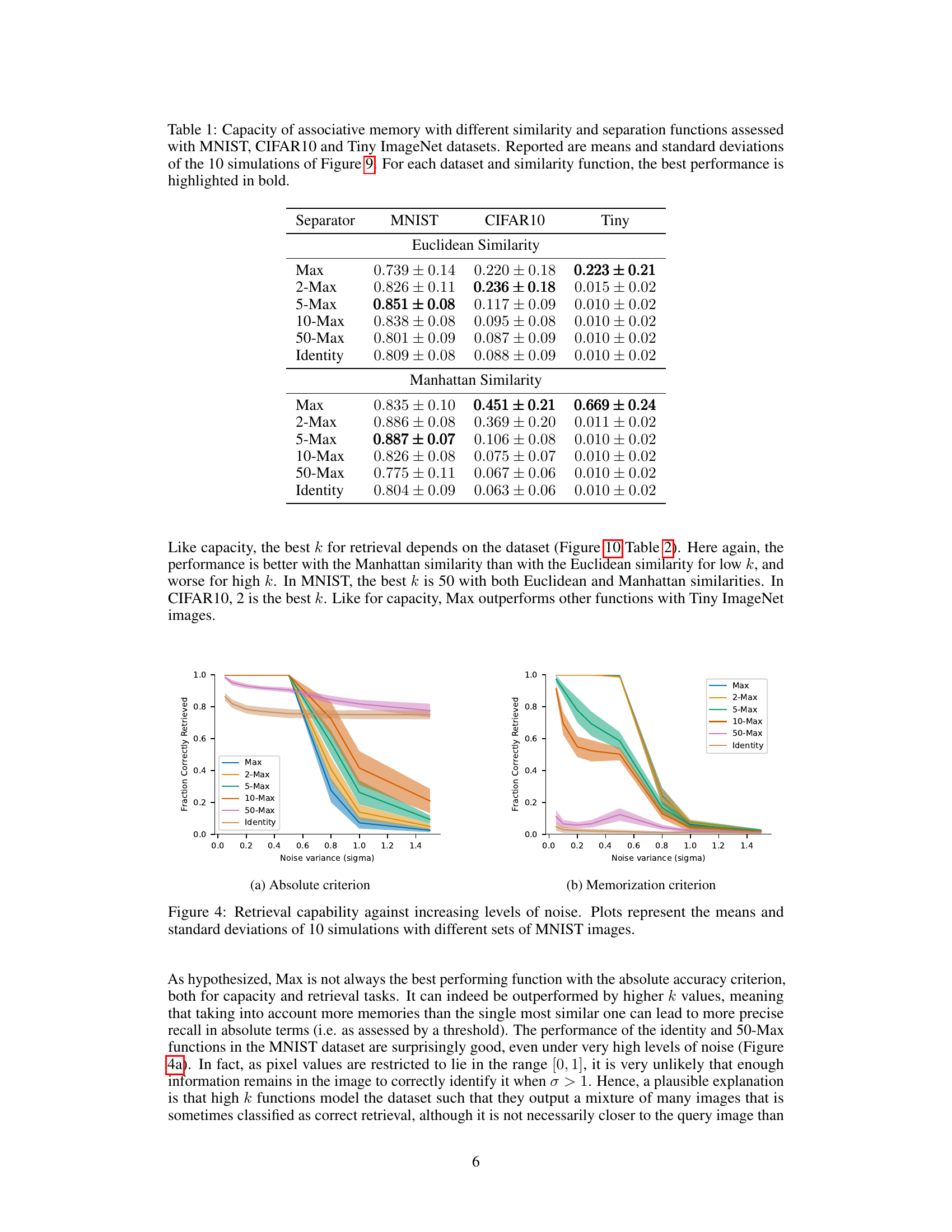

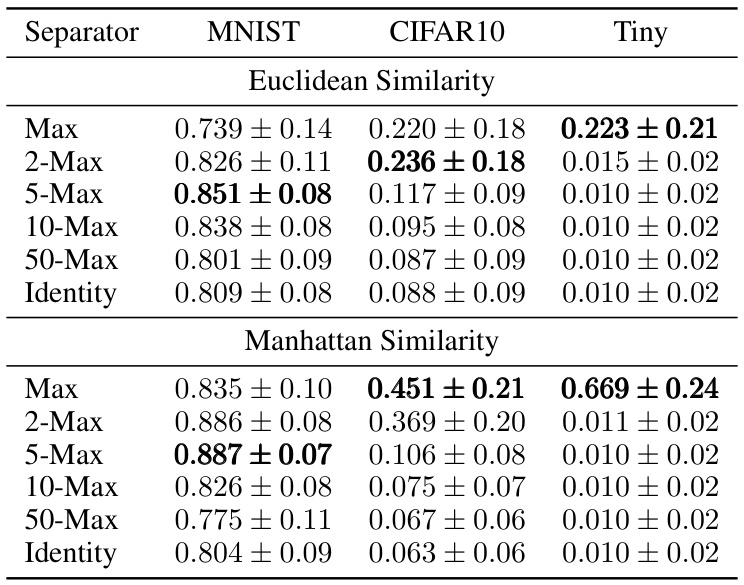

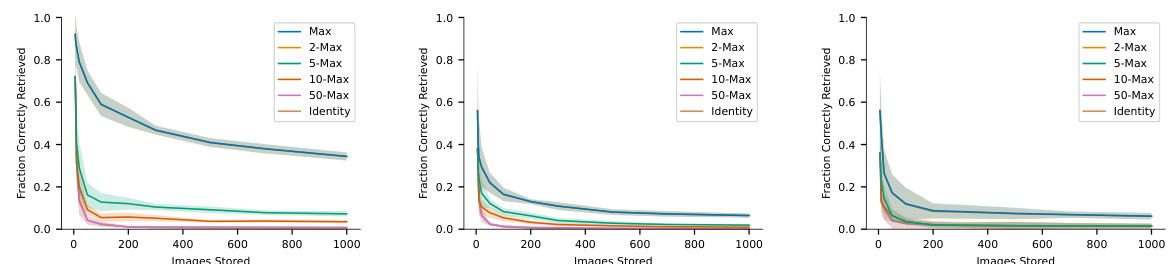

This figure shows the capacity of associative memory models using different similarity and separation functions on the MNIST dataset. The x-axis represents the number of images stored, and the y-axis represents the fraction of images correctly retrieved. Each line represents a different separation function (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, Identity), and the shaded areas represent the standard deviation across 10 simulations. The figure demonstrates how different separation functions impact the model’s ability to store and retrieve information. A trial is considered correct if the difference between the model’s output and the actual image is below a certain threshold.

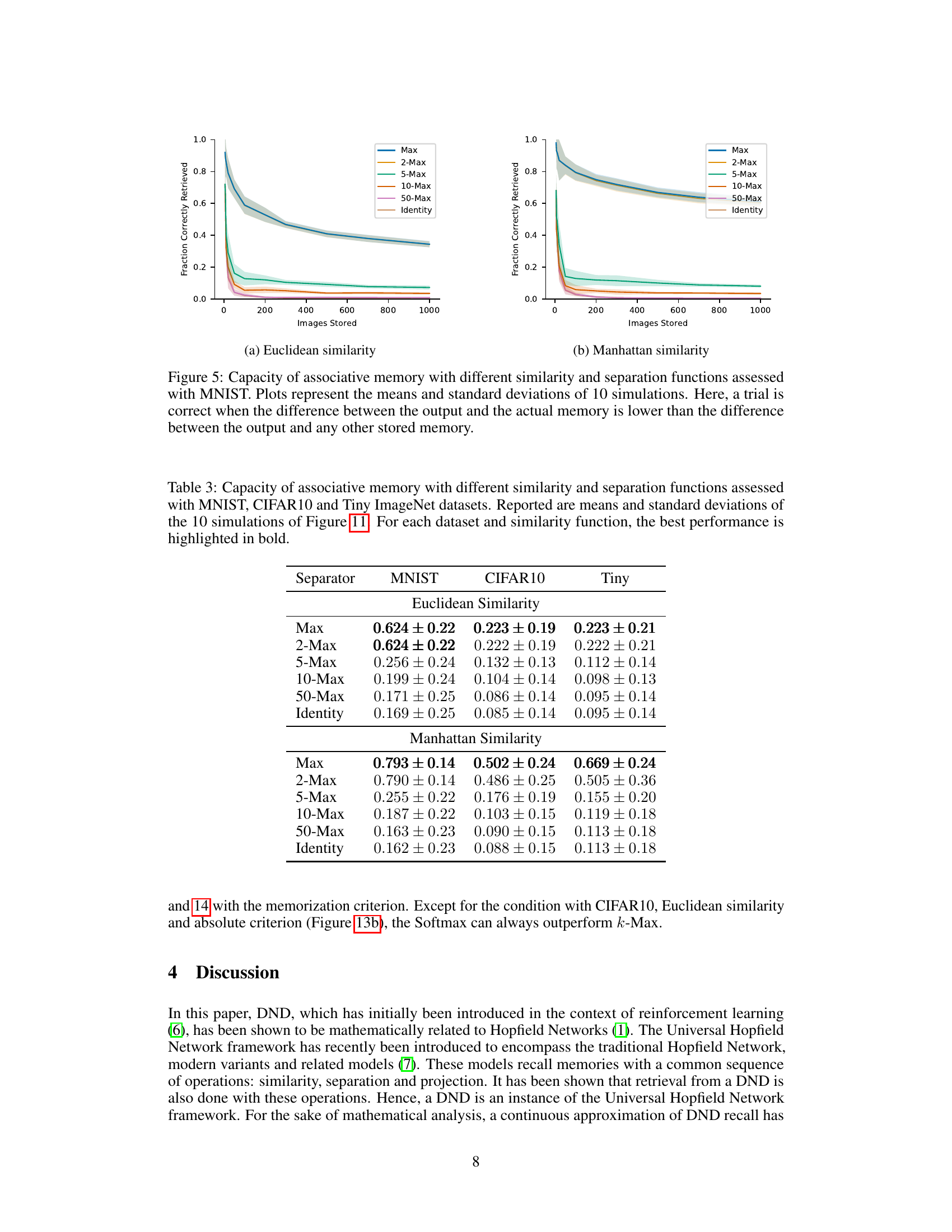

This figure shows the capacity of associative memory models using different similarity (Euclidean and Manhattan) and separation (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, Identity) functions. The x-axis represents the number of MNIST images stored, and the y-axis shows the fraction of images correctly retrieved. The plot displays the mean and standard deviation across 10 simulations for each condition. A trial is considered correct if the difference between the model’s output and the actual image is below a predefined threshold. The results demonstrate how the choice of similarity and separation function impacts the model’s ability to store and recall MNIST digits.

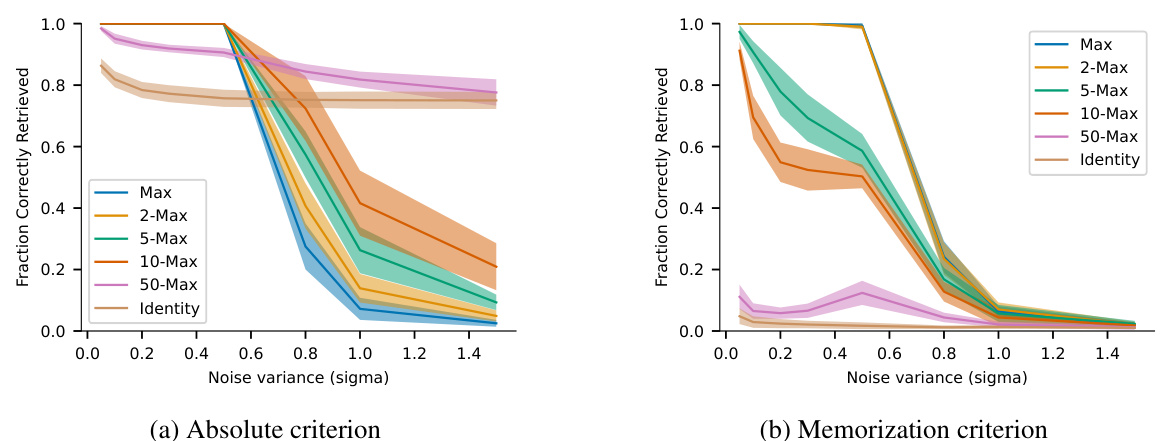

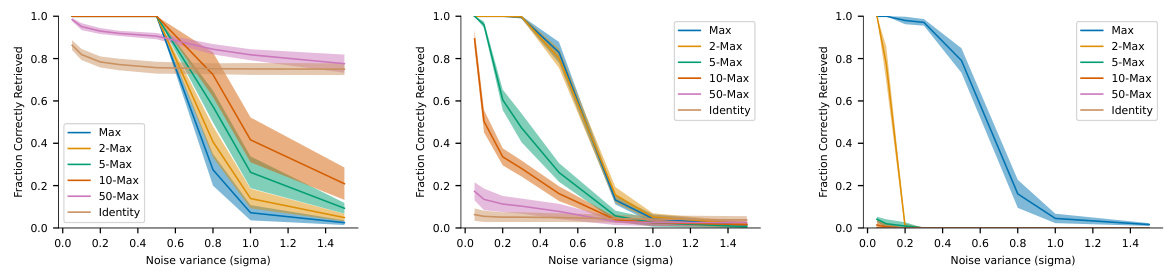

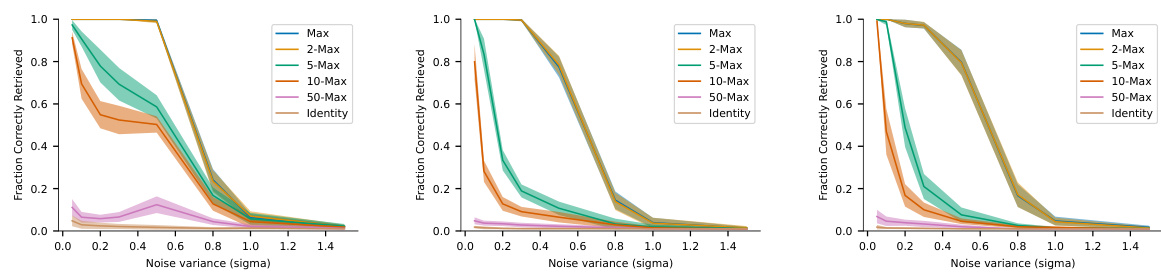

The figure shows the retrieval capability of the model against increasing levels of noise, using two different criteria: absolute accuracy and memorization. The x-axis represents the noise variance (sigma), and the y-axis represents the fraction of correctly retrieved images. Separate lines represent the performance of various separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, and Identity). The plots illustrate how different separation functions handle noisy inputs, revealing their robustness and resilience in recovering the original stored memories. The memorization criterion focuses on the model’s ability to recall stored images even when they are presented with noisy inputs, distinguishing it from simply modeling the statistical properties of the dataset.

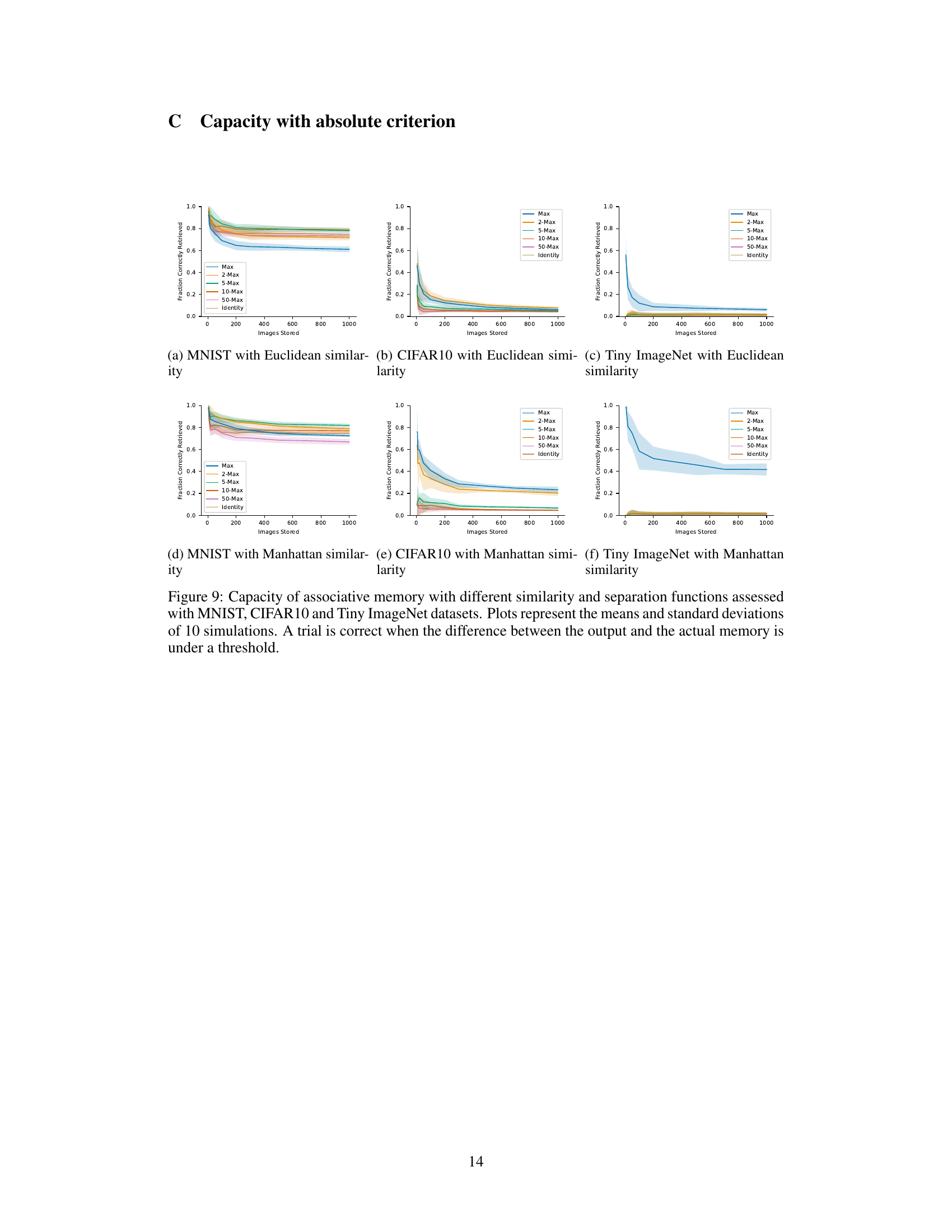

This figure shows the capacity of associative memory models using different similarity (Euclidean and Manhattan) and separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, and Identity). The x-axis represents the number of images stored, and the y-axis represents the fraction of correctly retrieved images. The plots include mean and standard deviation from 10 simulations. A trial is considered correct if the difference between the model’s output and the actual memory is below a specified threshold. The results demonstrate how different functions impact model capacity and the effects of varying the number of nearest neighbors considered during retrieval.

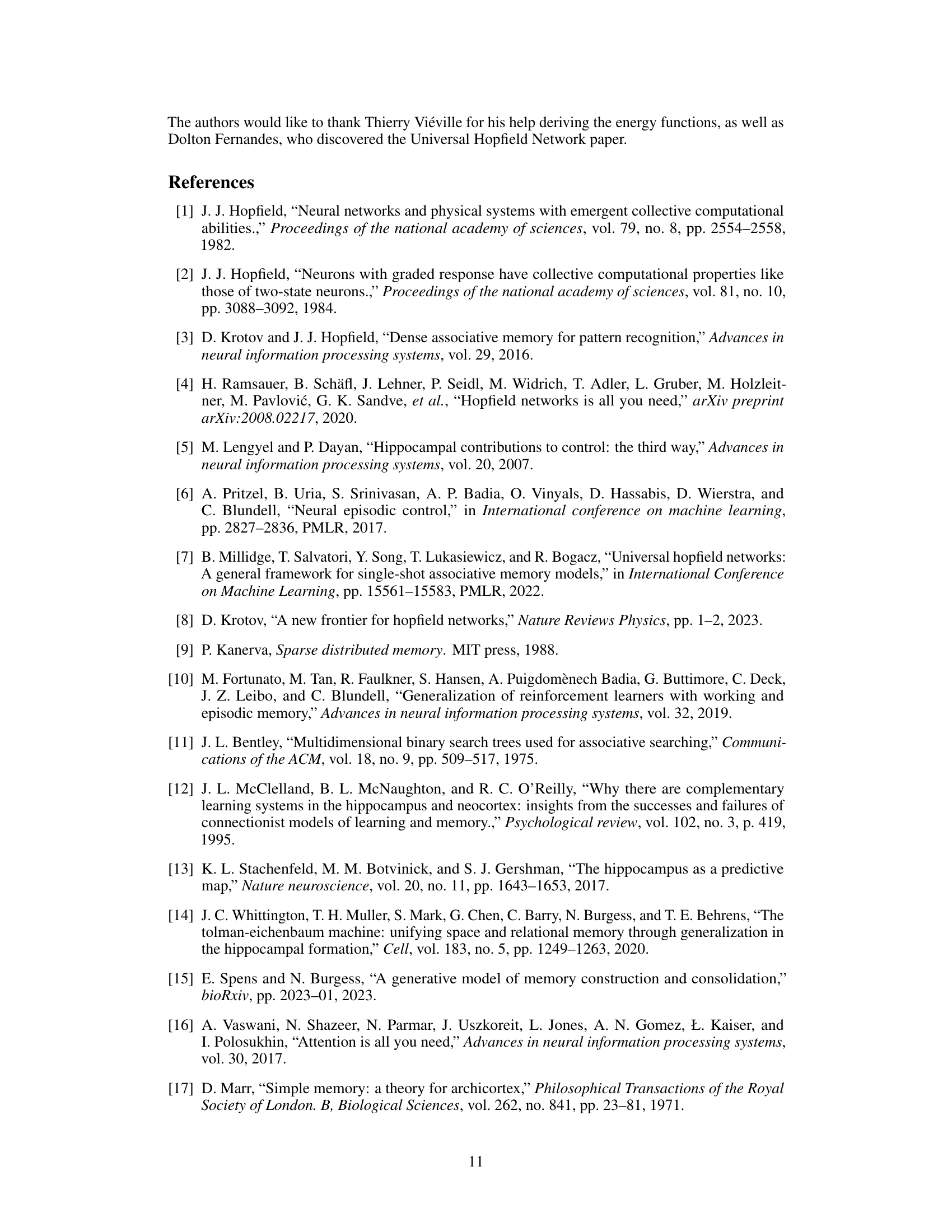

This figure compares the performance of k-Max and Softmax separation functions in terms of retrieval capability under noisy conditions. The x-axis represents the k parameter for k-Max, and the β parameter for Softmax, which both influence the sparsity of the model. The y-axis shows the fraction of correctly retrieved images. The plot reveals how different values of k and β impact the models’ ability to recall images, even when noise is added. Error bars show the standard deviation for each point.

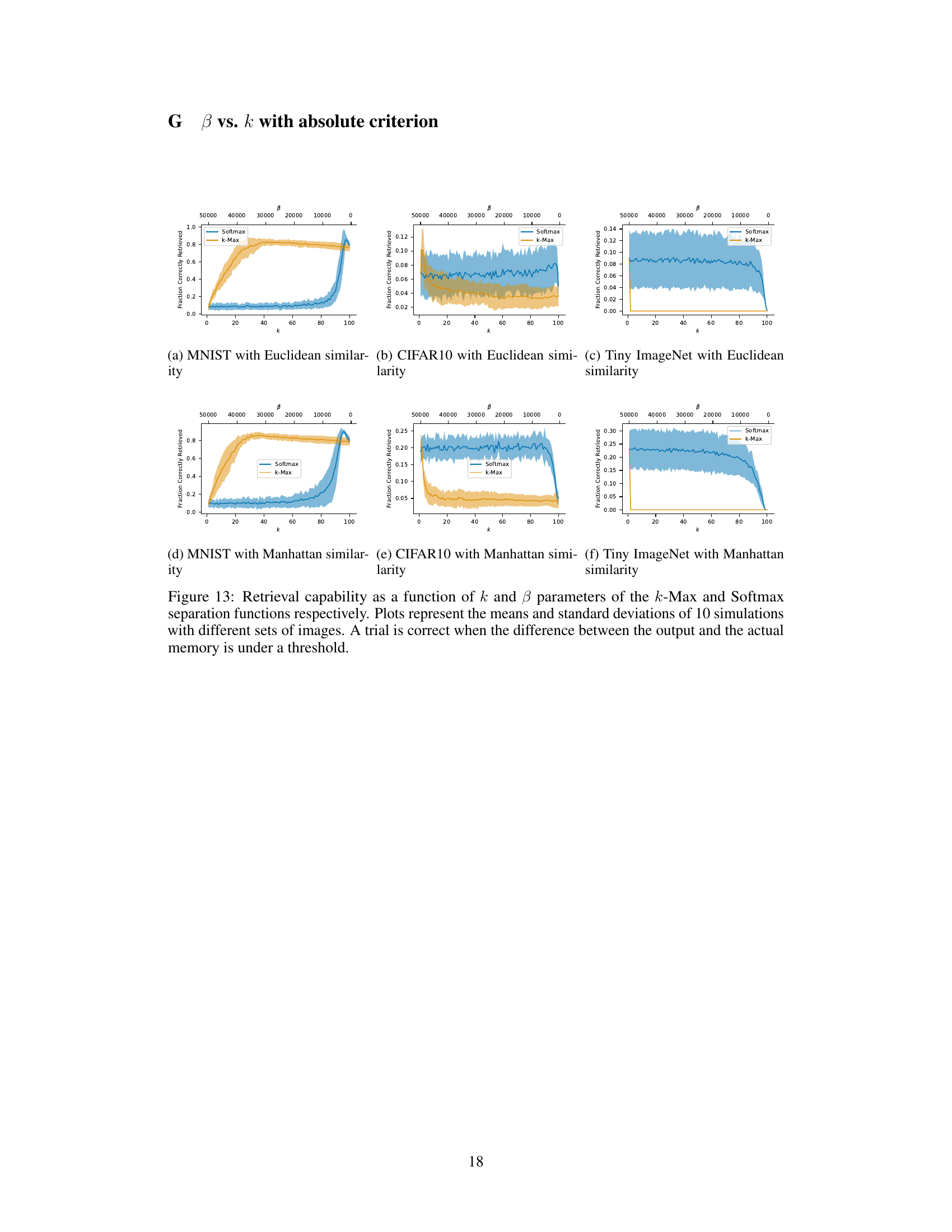

This figure compares the performance of k-Max and Softmax separation functions in terms of retrieval capability. The x-axis represents different values of k (number of nearest neighbors) for the k-Max function, while the y-axis shows the fraction of images correctly retrieved. The plot shows the mean and standard deviation across 10 simulations for each k value. The plot shows that the Softmax function generally outperforms the k-Max function across a wide range of k values when retrieving noisy MNIST images.

This figure shows example reconstructions of noisy MNIST digits using the Differentiable Neural Dictionary (DND). The top row displays the input cues with increasing levels of added noise. Subsequent rows illustrate the DND’s reconstruction of the stored memory for different values of k (k=1, 5, and 50), representing the number of nearest neighbors considered during retrieval. The figure demonstrates the DND’s ability to reconstruct images even with noisy input, although the quality of reconstruction varies with the level of noise and the value of k.

This figure shows example reconstructions of noisy MNIST digits using the Differentiable Neural Dictionary (DND). The top row displays the input cues with varying levels of added noise (noise variance increasing from left to right). The subsequent rows illustrate the DND’s reconstructions of the stored memories using different k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) values (k=1, k=5, k=50). It demonstrates how the DND performs with noisy inputs and different levels of considering nearby memories.

This figure displays the capacity of associative memory models using different similarity functions (Euclidean and Manhattan) and separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, Identity). The x-axis represents the number of images stored, and the y-axis shows the fraction of images correctly retrieved. Error bars represent standard deviations across 10 simulations. A trial is considered correct if the difference between the output and the actual stored memory is below a defined threshold. The results show how the capacity varies based on the combination of similarity and separation functions used, highlighting the differences between the models’ performance.

The figure shows the capacity of associative memory models with different similarity functions (Euclidean and Manhattan) and separation functions (Max, k-Max, Identity). The x-axis represents the number of images stored, and the y-axis shows the fraction of images correctly retrieved. Each line represents a different separation function, with error bars indicating the standard deviation across 10 simulations. The plot helps to compare how well different models are able to store and recall images based on varying similarity measures and separation strategies. A trial is considered successful if the difference between the model’s output and the original image is within a certain threshold.

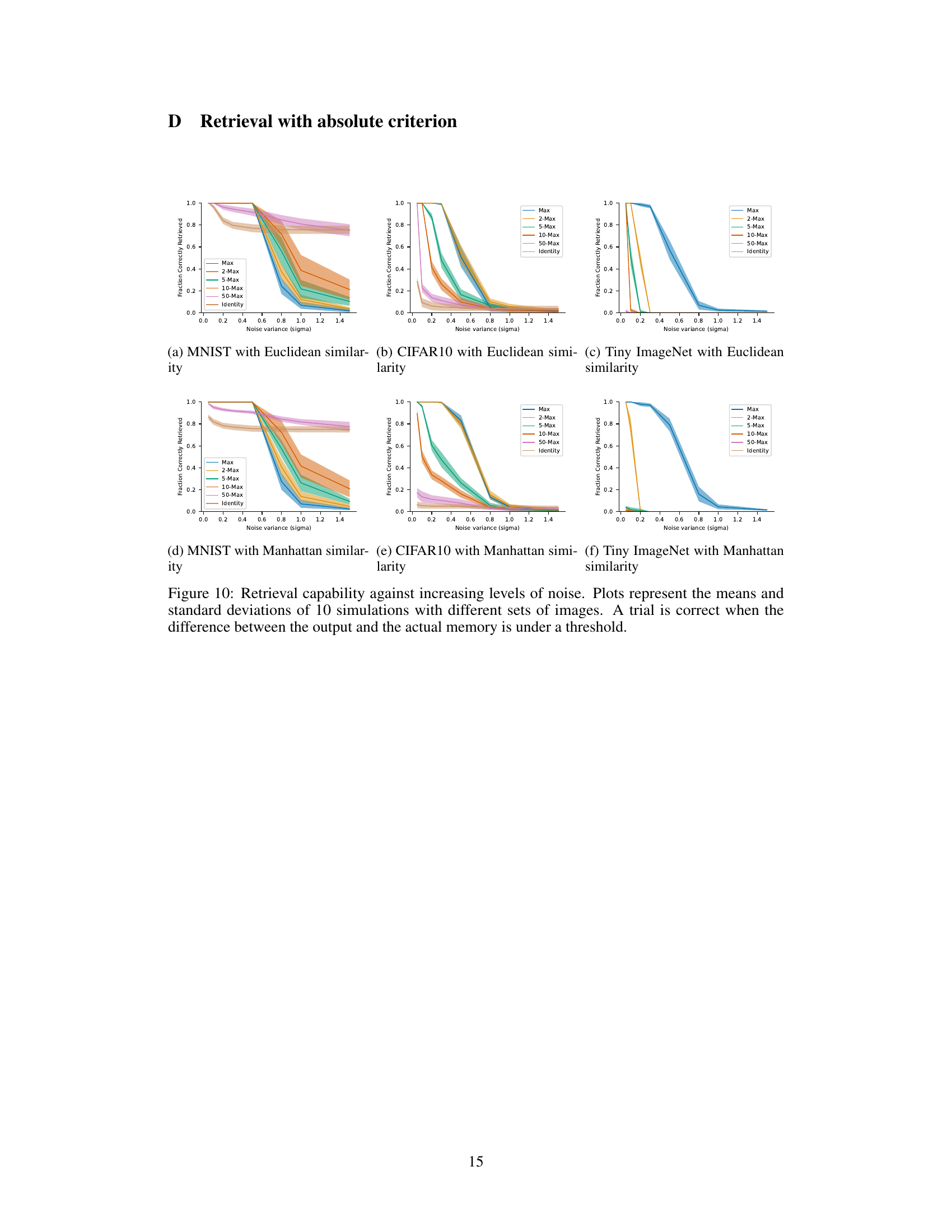

This figure shows the retrieval capability of the model against increasing levels of noise added to the input images. The plots show the mean and standard deviation of 10 simulations. A trial is considered correct when the difference between the output and the actual memory is less than a certain threshold. Different separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, Identity) and similarity functions (Euclidean and Manhattan) were compared.

The figure shows the retrieval capability of the model under different levels of noise, using the absolute accuracy criterion. The plots show the mean and standard deviation of 10 simulations, for different separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, Identity) and different datasets. A trial is considered correct if the difference between the model’s output and the actual memory is below a predefined threshold.

This figure shows the capacity of associative memory models using different similarity functions (Euclidean and Manhattan) and separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, and Identity) on the MNIST dataset. The x-axis represents the number of images stored, and the y-axis represents the fraction of images correctly retrieved. Error bars indicate standard deviations across 10 simulations. A trial is considered correct if the difference between the model’s output and the actual image is below a predefined threshold. The plot helps to compare the performance of different similarity and separation methods in terms of their capacity to store and accurately retrieve images.

This figure shows the capacity of the differentiable neural dictionary (DND) model as an associative memory on the MNIST dataset. The capacity is measured by the fraction of correctly retrieved images as the number of stored images increases. The figure compares the performance of DND using different similarity functions (Euclidean and Manhattan) and separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, and Identity). Error bars represent standard deviations across 10 simulations. A trial is considered correct if the squared difference between the output and the actual memory is below a threshold of 50.

This figure shows the retrieval capability of the model against increasing levels of noise. The plots show the means and standard deviations from 10 simulations using different sets of images. A trial is considered correct only when the difference between the model’s output and the actual memory is below a defined threshold. The figure is divided into six subplots (two rows and three columns), each corresponding to a specific combination of dataset and similarity function used (Euclidean or Manhattan), highlighting how retrieval performance changes with different noise levels across various settings.

This figure shows the capacity of associative memory models using different similarity (Euclidean and Manhattan) and separation functions. The x-axis represents the number of MNIST images stored, and the y-axis represents the fraction of images correctly retrieved. Error bars represent standard deviations across 10 simulations. A trial is considered correct if the difference between the output image and the actual memory image is below a defined threshold. The results demonstrate that the Manhattan similarity function consistently outperforms the Euclidean similarity function.

This figure shows the capacity of associative memory models using different similarity functions (Euclidean and Manhattan) and separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, and Identity). The x-axis represents the number of images stored, and the y-axis shows the fraction of correctly retrieved images (accuracy). Error bars represent standard deviations across 10 simulations. A trial is considered correct if the difference between the model’s output and the actual memory is below a certain threshold. The results demonstrate the impact of different similarity and separation functions on the model’s ability to store and retrieve memories accurately.

This figure shows the capacity of associative memory models using different similarity functions (Euclidean and Manhattan) and separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, Identity). The x-axis represents the number of images stored, and the y-axis represents the fraction of correctly retrieved images. The results show that the Manhattan similarity function generally outperforms the Euclidean similarity function, and that the optimal separation function depends on the dataset and the number of stored memories.

This figure compares the performance of k-Max and Softmax separation functions in terms of retrieval capability across different levels of noise. The x-axis represents the k parameter for k-Max and the β parameter for Softmax. The y-axis shows the fraction of correctly retrieved images. The plots show the mean and standard deviation across 10 simulations for each dataset. This helps assess how these functions perform in retrieving similar memories, under the criterion of absolute accuracy.

This figure shows the capacity of associative memory models using different similarity functions (Euclidean and Manhattan) and separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, and Identity). The x-axis represents the number of images stored, and the y-axis represents the fraction of correctly retrieved images. The plot shows that the Manhattan distance consistently outperforms the Euclidean distance, especially when the number of neighbors considered is low (k). The capacity varies with different values of k (number of nearest neighbors considered), suggesting that choosing the optimal k is dataset-dependent.

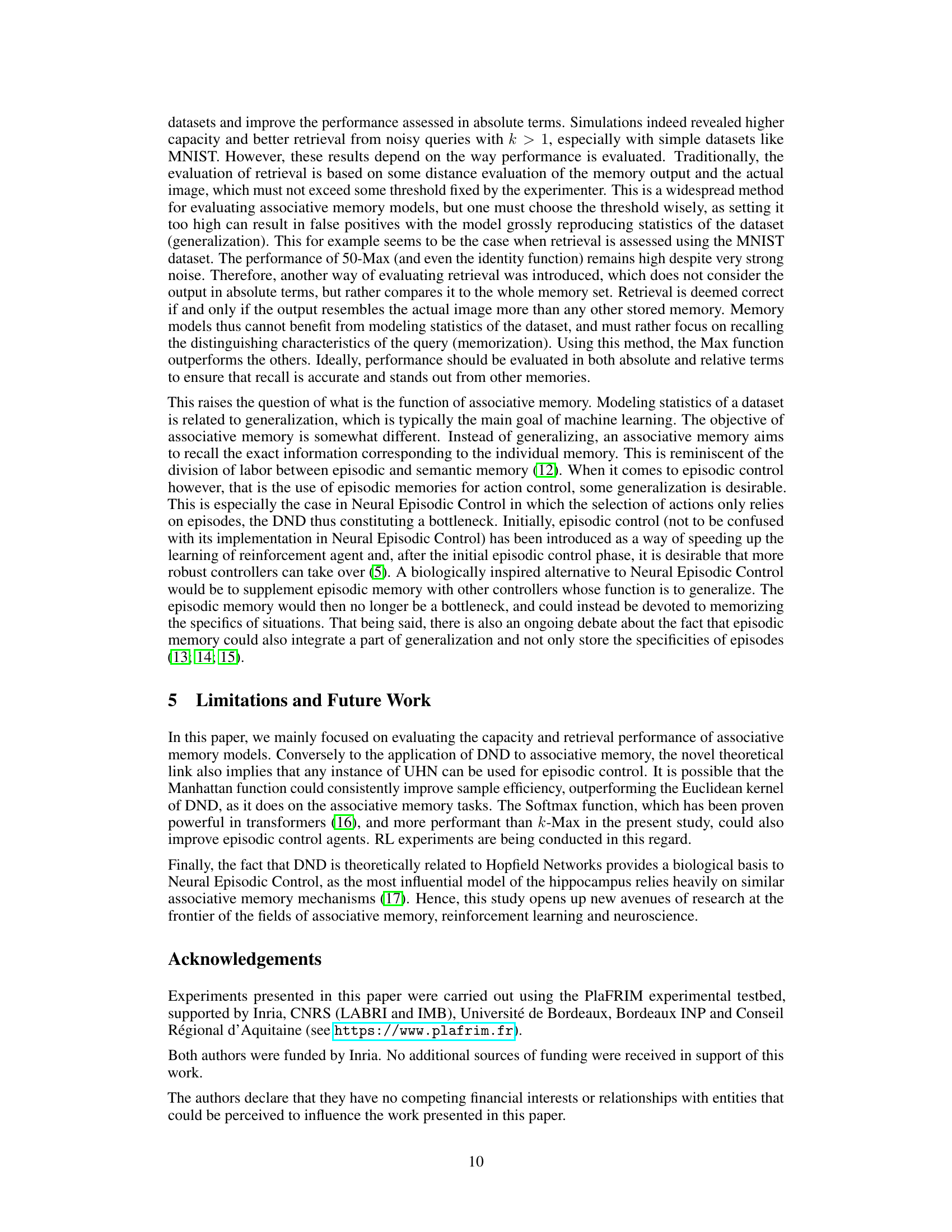

More on tables

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the retrieval capability of different associative memory models under various levels of noise. The models use either Euclidean or Manhattan similarity functions, along with different separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, and Identity). The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the retrieval accuracy across 10 simulations for each configuration. The best-performing model for each dataset and similarity function is highlighted in bold.

This table shows the capacity of associative memory models using different similarity functions (Euclidean and Manhattan) and separation functions (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, Identity). The capacity is measured for three datasets: MNIST, CIFAR10, and Tiny ImageNet. Results are averaged over 10 simulations and show the mean and standard deviation. The best performing model for each dataset and similarity type is highlighted in bold. This table helps to assess how different similarity and separation functions impact the model’s ability to store and recall information.

This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the retrieval capability of different associative memory models under noisy conditions. The experiment varied the type of similarity function (Euclidean and Manhattan), the separation function (Max, 2-Max, 5-Max, 10-Max, 50-Max, Identity), and the dataset (MNIST, CIFAR10, Tiny ImageNet). The results, averaged over 10 simulations, show the mean and standard deviation of the retrieval accuracy. The best performing models are highlighted in bold for each dataset and similarity function.

Full paper#