TL;DR#

Transformers struggle with length generalization, especially for arithmetic tasks. Existing methods like index hinting and advanced positional embeddings have shown limited success, often requiring deeper networks and more data. This necessitates improved methods that enable Transformers to effectively extrapolate their capabilities beyond the training data length.

The paper introduces ‘position coupling’, a novel technique that directly embeds task structure into positional encodings. By assigning the same positional IDs to ‘relevant’ tokens (e.g., digits of the same significance in addition), position coupling allows small, 1-layer Transformers to generalize to significantly longer sequences than those encountered during training. The authors demonstrate this improvement empirically and support it theoretically, proving that this approach enhances a Transformer’s ability to understand and generalize the inherent structure of arithmetic operations.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on Transformer models and sequence-to-sequence tasks. It directly addresses the significant challenge of length generalization, providing both empirical results and theoretical insights that can inform future model designs and research directions. Its focus on task structure offers a novel approach to improve model performance on longer sequences without needing excessive amounts of training data.

Visual Insights#

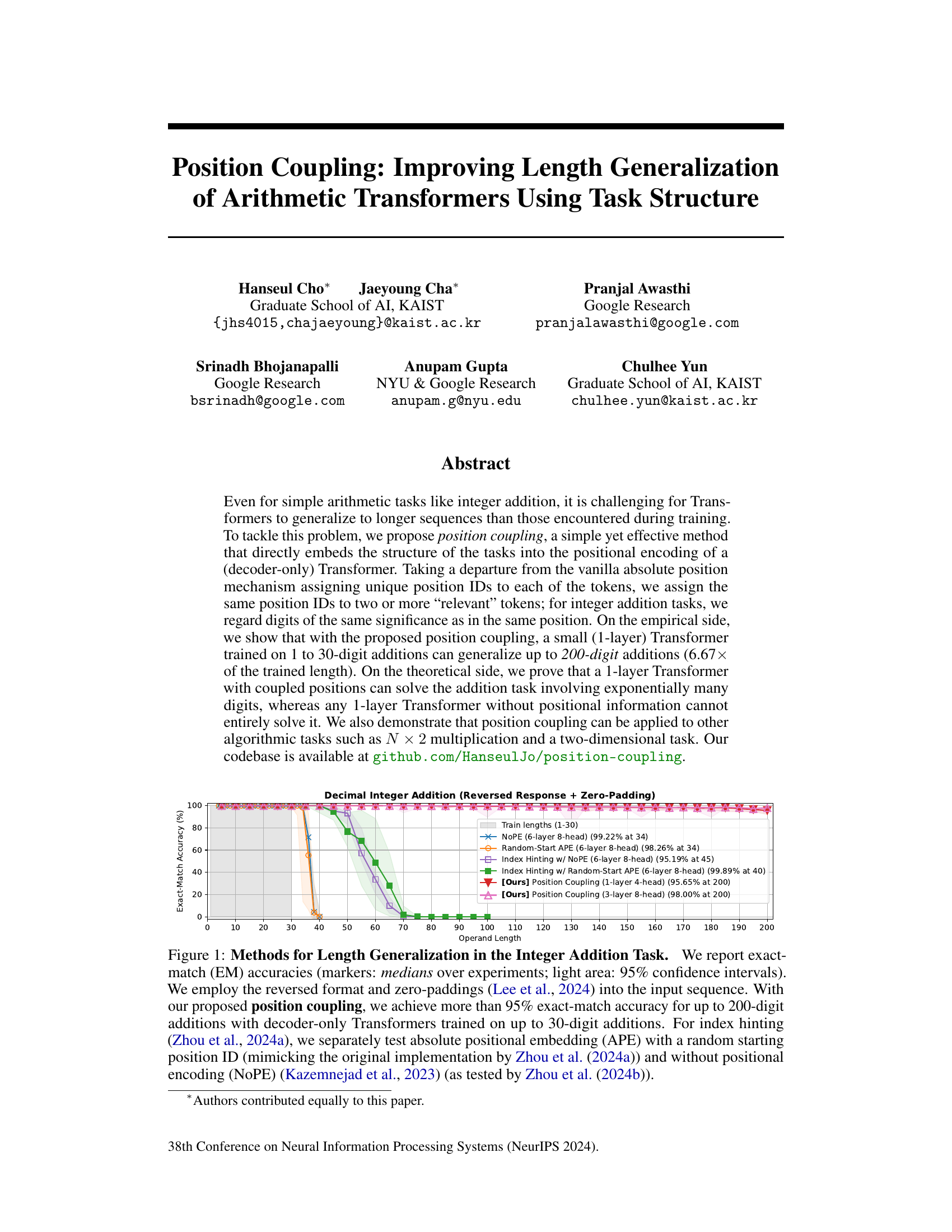

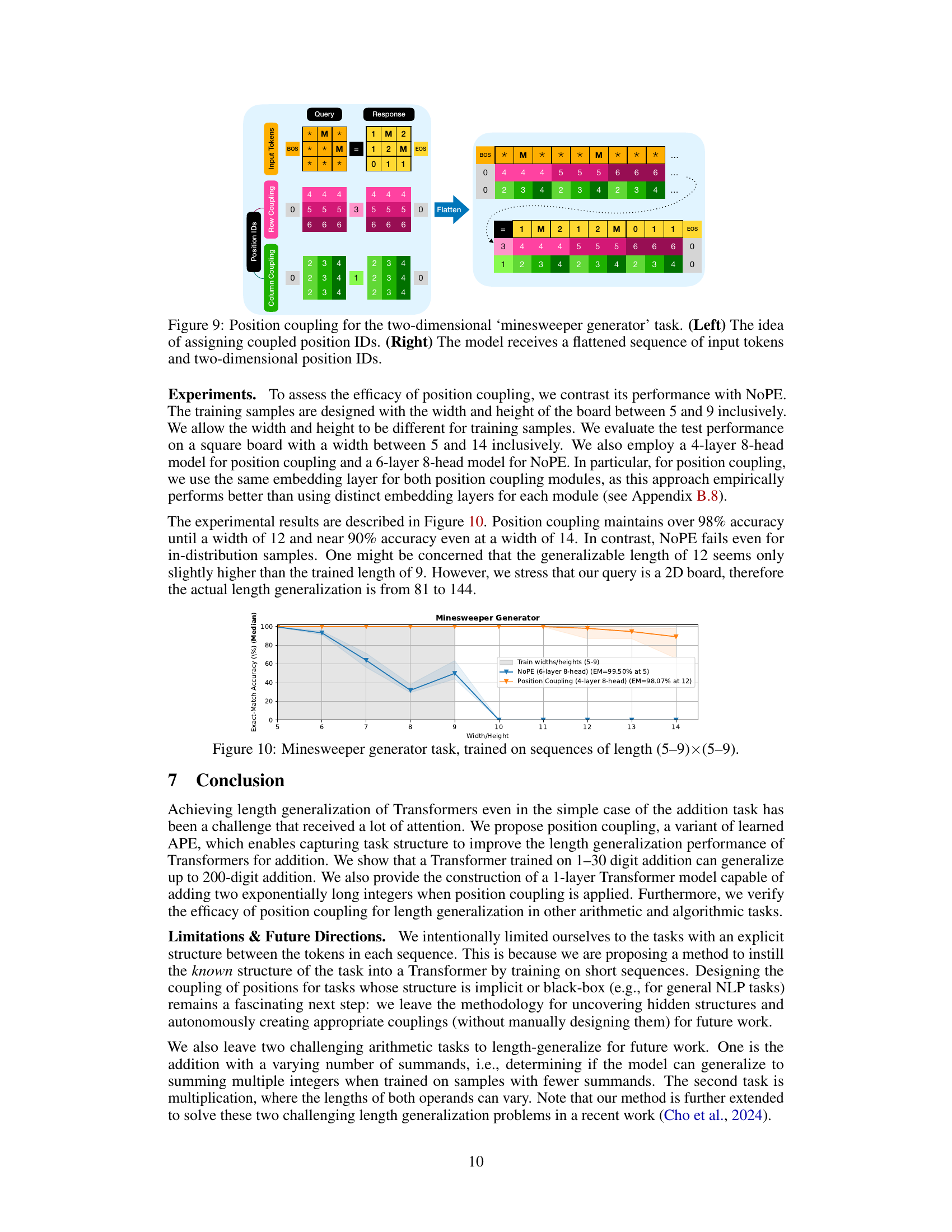

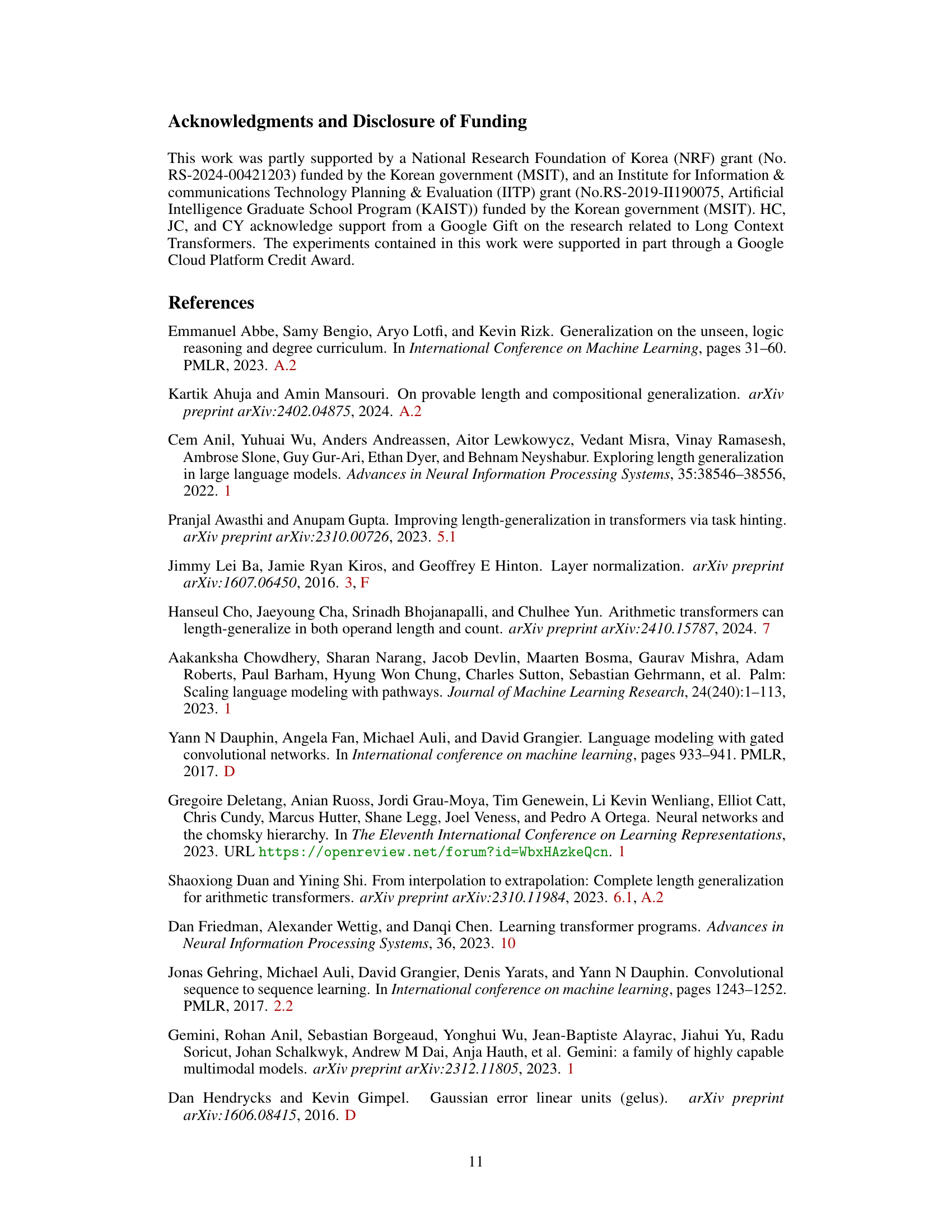

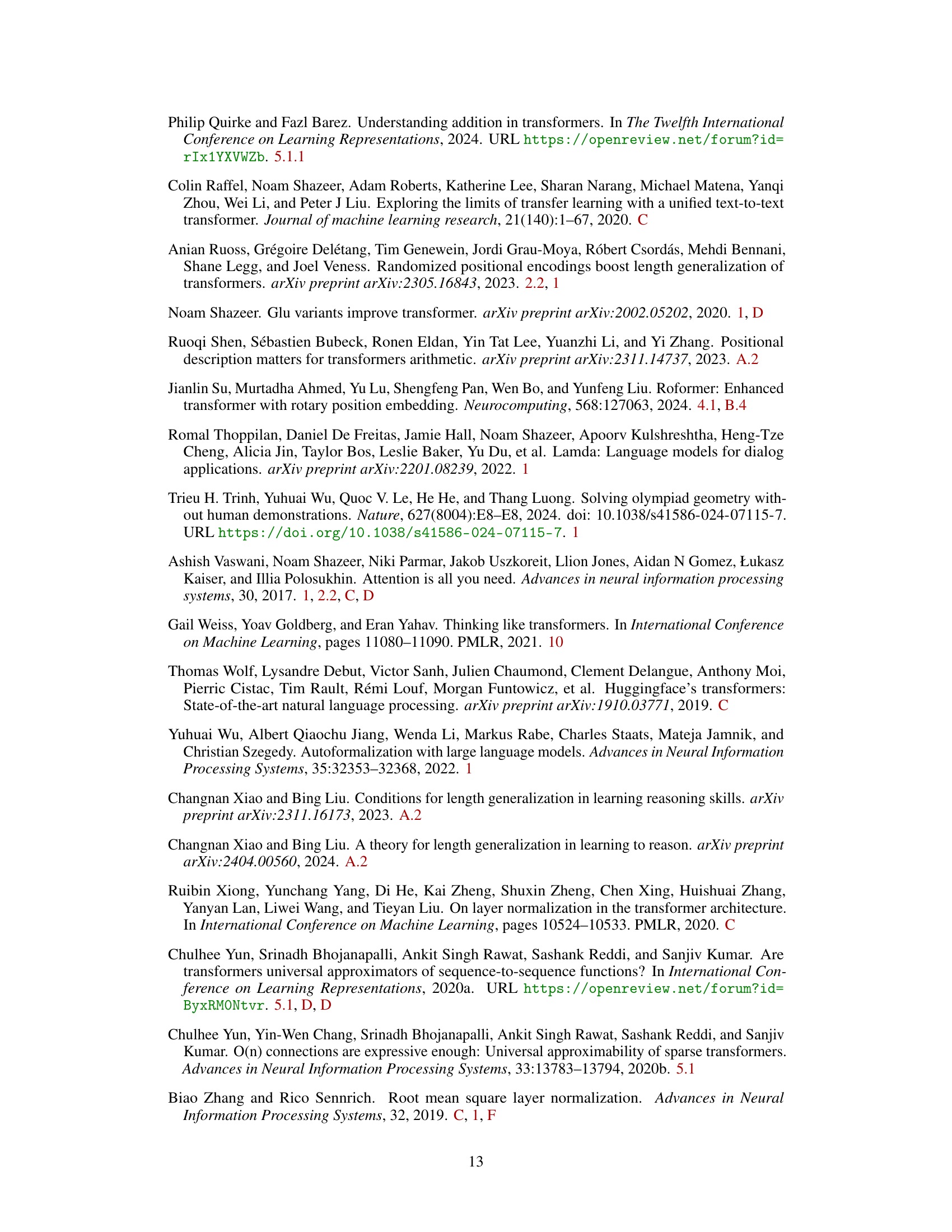

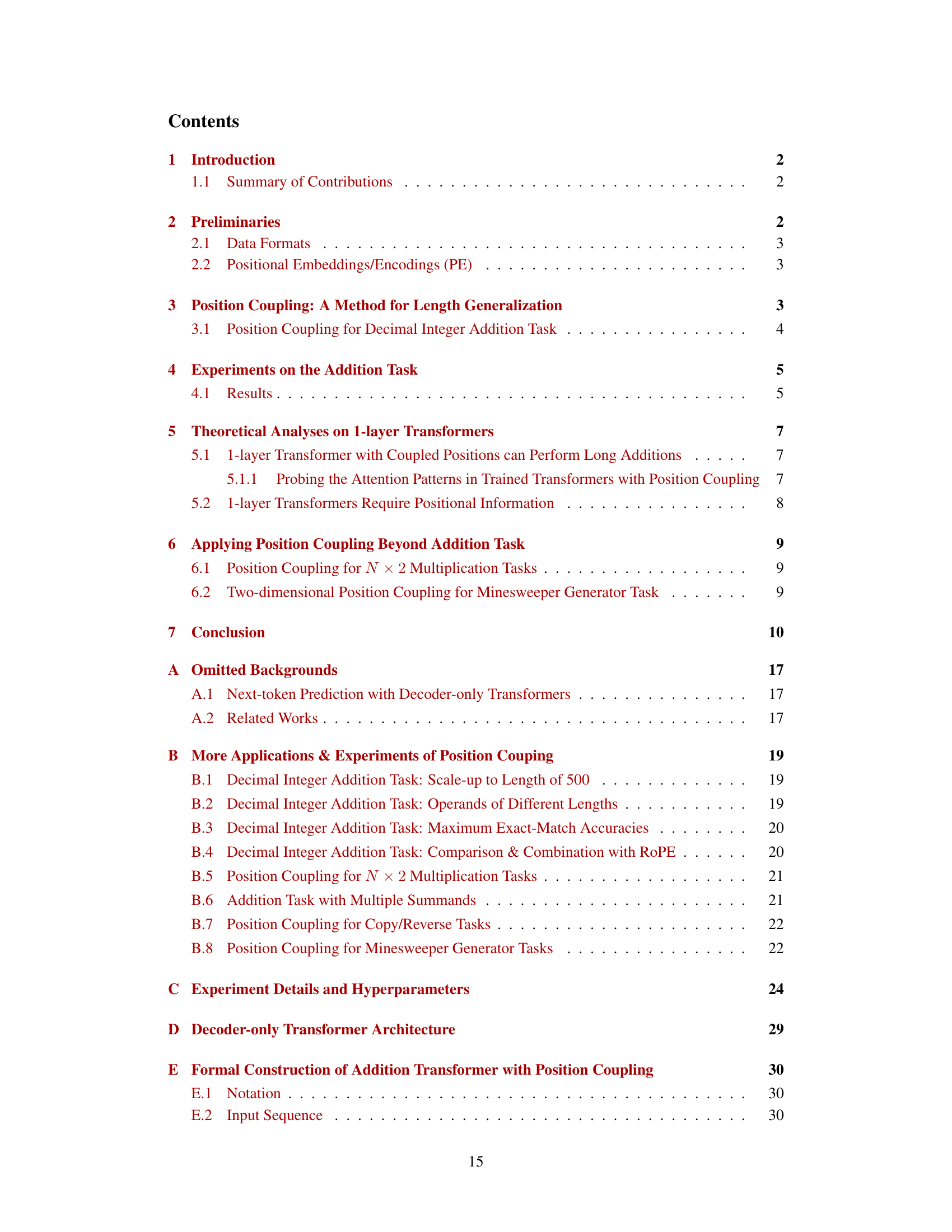

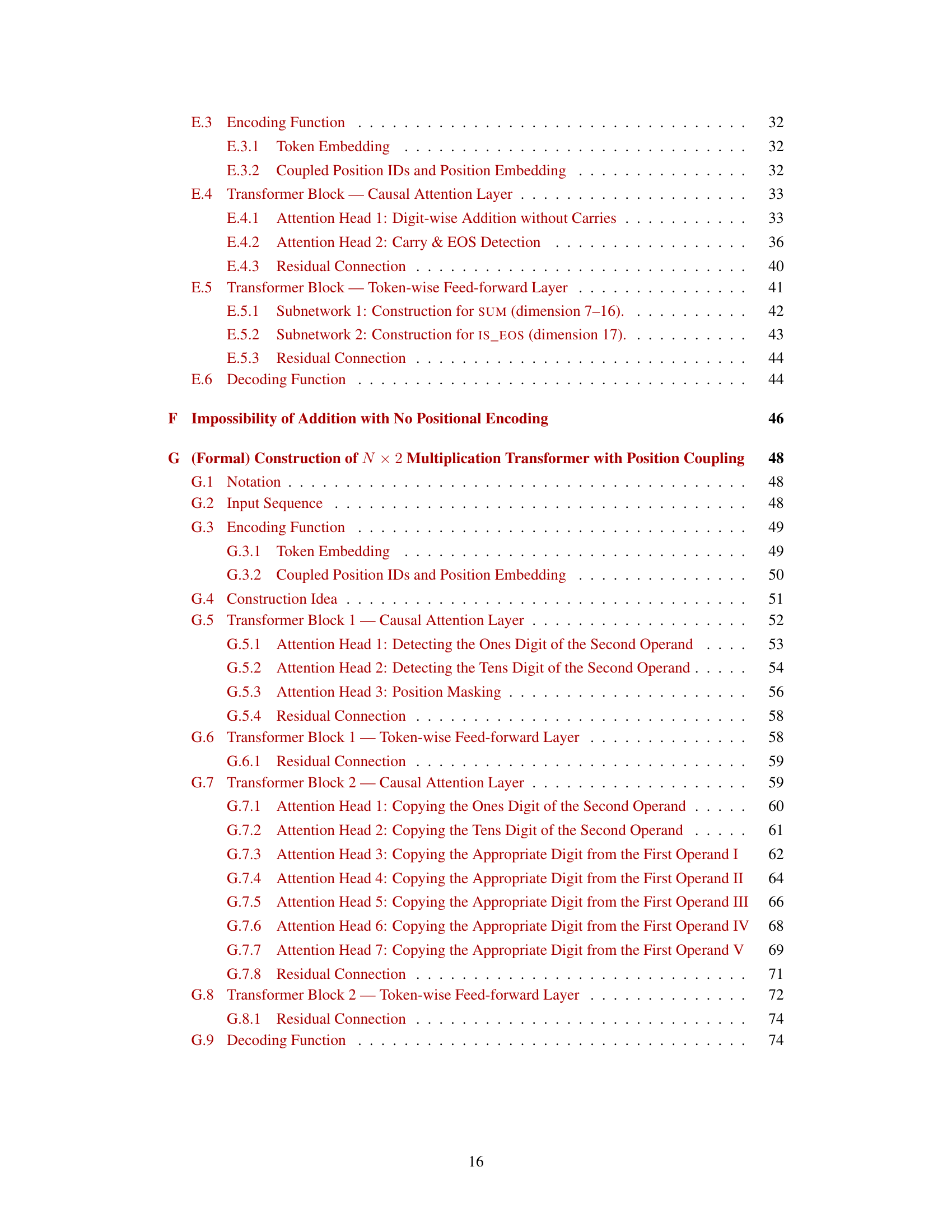

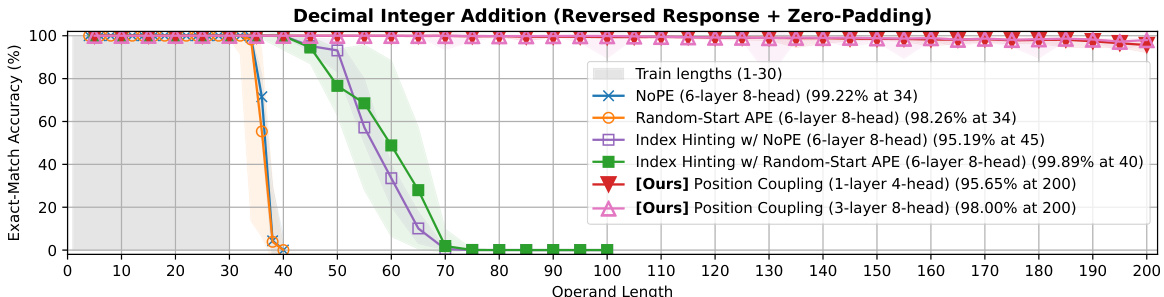

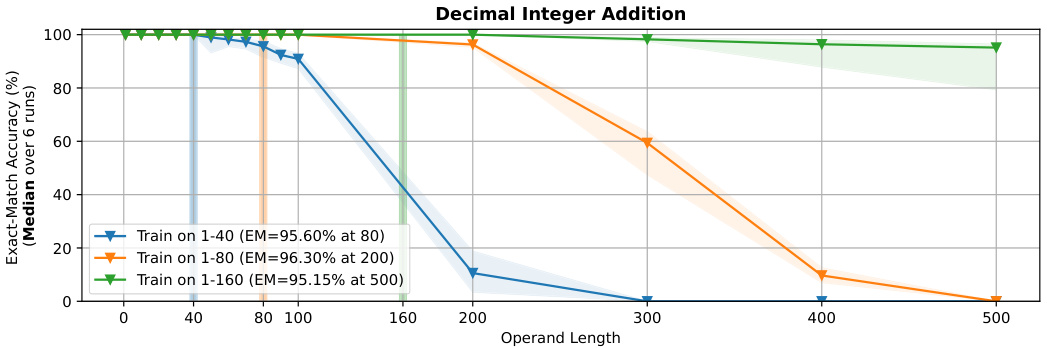

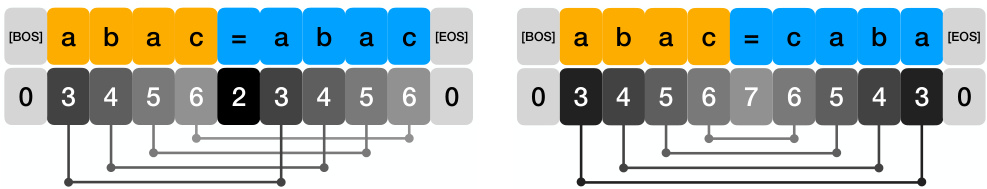

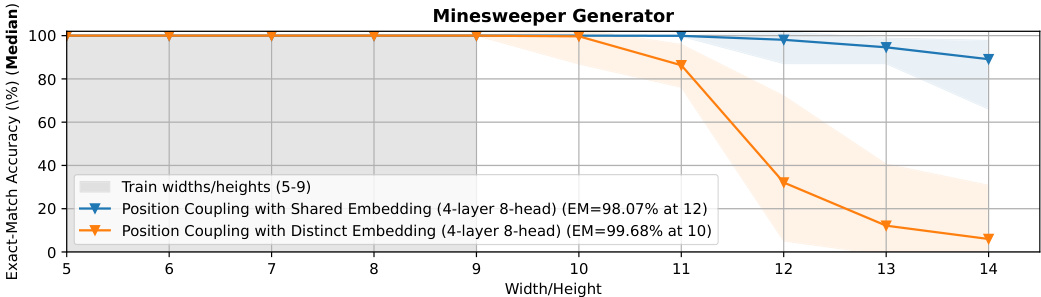

🔼 This figure compares different methods for achieving length generalization in the task of integer addition. The x-axis represents the length of the operands used for addition. The y-axis shows the exact match accuracy. The figure shows that the proposed position coupling method significantly outperforms other methods, achieving over 95% accuracy even when tested on operands with lengths that are up to 6.67x longer than the training data. The figure also provides a comparison with NoPE (no positional embedding), random start APE (Absolute Positional Embedding with a random starting position ID), and index hinting (a method that uses positional markers in the input sequence).

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

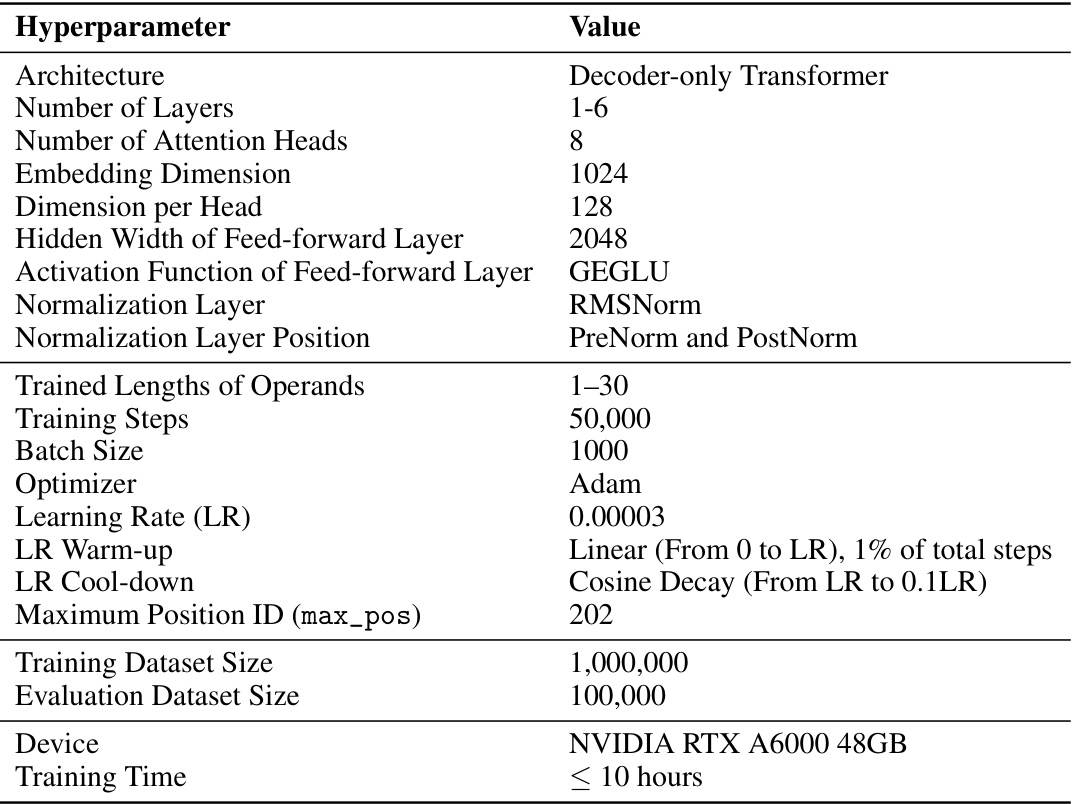

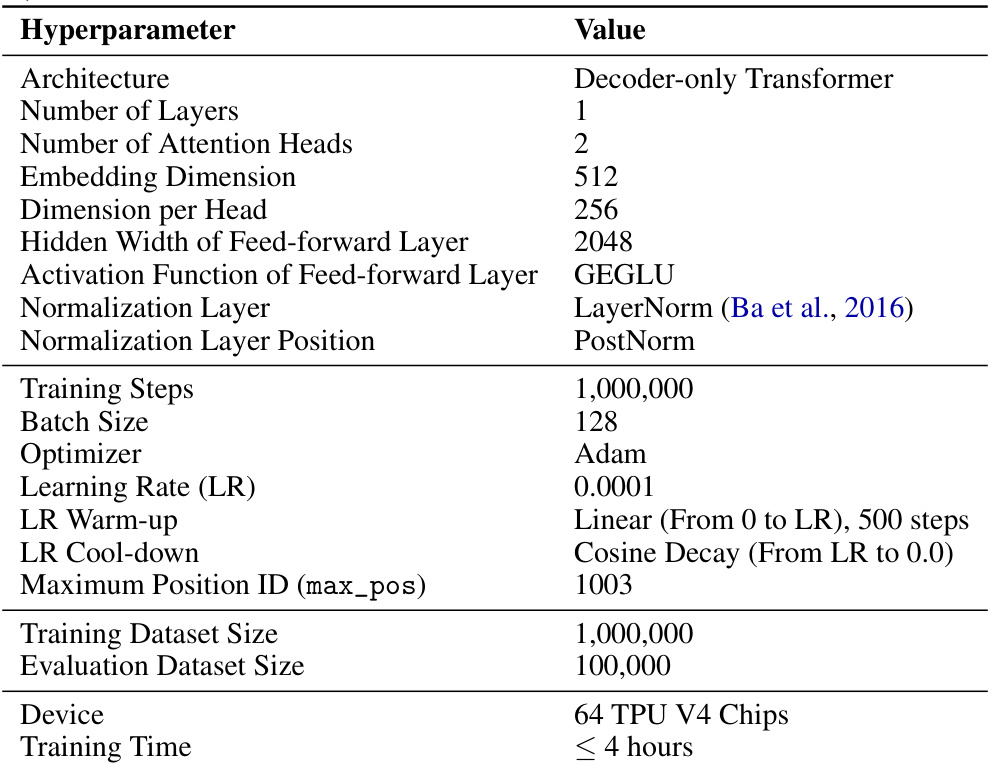

🔼 This table presents the hyperparameters used for the decimal integer addition task experiments. It shows the architecture (decoder-only Transformer), the number of layers, attention heads, embedding dimension, dimension per head, hidden width of the feed-forward layer, activation function, normalization layer, normalization layer position, training steps, batch size, optimizer (Adam), learning rate, learning rate warm-up and cool-down, maximum position ID, training dataset size, evaluation dataset size, device (NVIDIA RTX A6000 48GB), and training time.

read the caption

Table 1: Hyperparameter summary for decimal integer addition task: comparison between trained lengths (Figures 3 and 14).

In-depth insights#

Position Coupling#

The proposed method, Position Coupling, ingeniously addresses the challenge of length generalization in Transformers. Instead of using unique positional IDs, it cleverly assigns the same ID to semantically related tokens, thus embedding task structure directly into the positional encoding. This approach is particularly effective for arithmetic tasks, where digits of the same significance are coupled, enabling generalization to much longer sequences than those seen during training. This simple yet powerful technique allows even small, 1-layer Transformers to achieve significant accuracy on tasks like 200-digit addition after being trained on considerably shorter sequences. Furthermore, the theoretical underpinnings of Position Coupling are explored, demonstrating its ability to solve tasks with exponentially long inputs. This method’s success is attributed to its ability to inject inherent task structure into the Transformer, effectively guiding the model towards solving the tasks based on the underlying relationships between elements, rather than merely memorizing patterns from limited training data. Its applicability extends beyond arithmetic, showcasing versatility across other algorithmic tasks. Position coupling presents a promising direction for enhancing the out-of-distribution generalization capabilities of Transformers.

Length Generalization#

The concept of ‘Length Generalization’ in the context of transformer models centers on a model’s ability to successfully extrapolate its performance to input sequences longer than those encountered during training. This is a crucial aspect because it directly reflects the model’s true understanding of the underlying task structure, rather than mere memorization. The paper highlights the challenge of achieving length generalization, particularly in tasks like arithmetic where a simple algorithm is expected. Traditional approaches that rely on absolute positional embeddings often fail to generalize beyond the training length. The proposed method of ‘position coupling’ addresses this limitation by directly embedding the task structure into the positional encoding, allowing even small transformers trained on short sequences to generalize remarkably well to significantly longer sequences. This success suggests a path toward creating models that not only solve specific tasks but also genuinely grasp the inherent rules governing them.

Transformer Models#

Transformer models, initially designed for sequence-to-sequence tasks, have revolutionized natural language processing and beyond. Their core mechanism, the self-attention mechanism, allows for parallel processing of input sequences, capturing long-range dependencies that were previously difficult to model. This has led to significant improvements in various tasks such as machine translation, text summarization, and question answering. However, challenges remain, particularly concerning length generalization and computational efficiency. While scaling up model size often improves performance, it also increases computational costs and may not always lead to better generalization. Positional encodings, crucial for providing information about token order, are an active area of research, with methods such as absolute and relative positional encodings offering different trade-offs. Furthermore, the interpretability of these models remains a significant challenge, hindering a deep understanding of their internal workings. Nevertheless, transformer architectures continue to evolve, leading to innovations in areas like efficient attention mechanisms and improved training techniques that promise to address some of the existing limitations and unlock the potential of even more complex applications.

Empirical Results#

An Empirical Results section in a research paper would present quantitative findings that validate the study’s claims. It should go beyond simply reporting raw numbers; instead, a strong Empirical Results section will carefully analyze trends and patterns, compare results across different conditions or groups, and discuss any unexpected or noteworthy findings. Statistical significance testing (p-values, confidence intervals) is essential to establish the reliability of the observed effects. Visualizations like graphs and tables should be clear and well-labeled to facilitate understanding. The discussion should relate findings directly back to the hypotheses and the paper’s overall research question, highlighting both successes and limitations in meeting the study’s objectives. A crucial aspect is to avoid overinterpreting or selectively presenting data. Any limitations in the experimental design or data analysis should be openly acknowledged, ensuring transparency and maintaining the integrity of the research.

Future Directions#

The paper’s “Future Directions” section would ideally delve into the challenges of extending position coupling to tasks with implicit or black-box structures, unlike the clearly defined arithmetic problems explored. This would necessitate developing methods for automatically uncovering hidden task structures and creating appropriate positional couplings without manual design, a significant leap beyond the current methodology. Another crucial area would involve addressing the length generalization challenge in tasks with a varying number of summands or operands of variable lengths. These are common scenarios in real-world applications that current approaches struggle with. Finally, exploring theoretical explanations for the observed limitations of deeper models on simpler algorithmic tasks would add valuable insight into model architectural biases and the limits of generalization. This might involve further investigation into implicit biases that cause performance degradation in deeper networks. Addressing these key areas would strengthen the paper’s impact and suggest promising avenues for future research in length generalization.

More visual insights#

More on figures

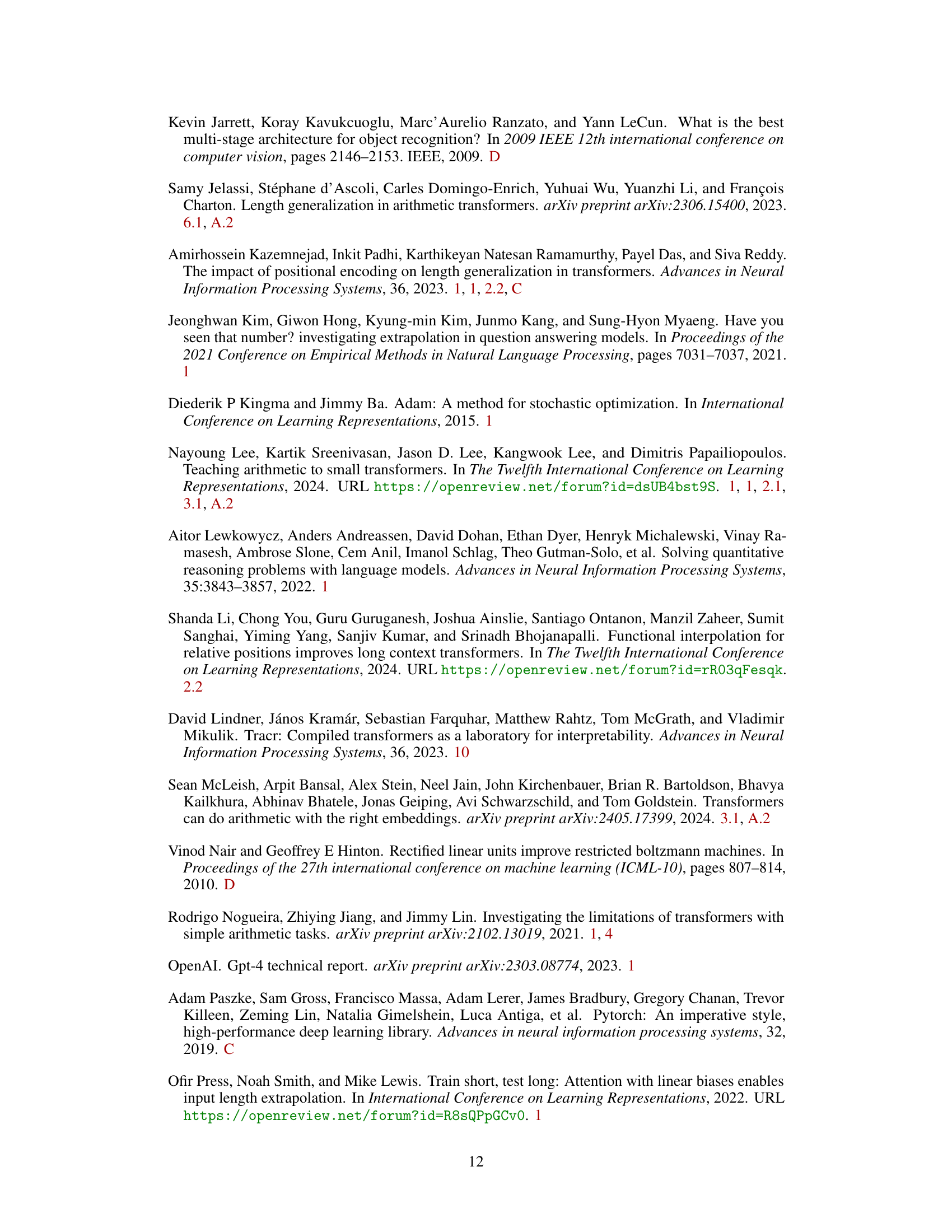

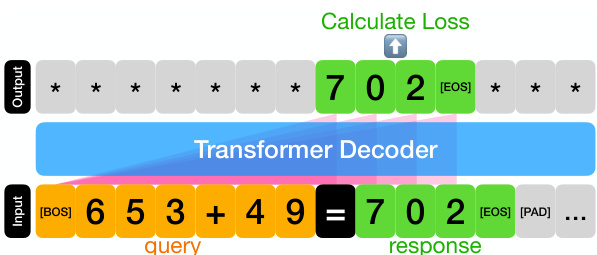

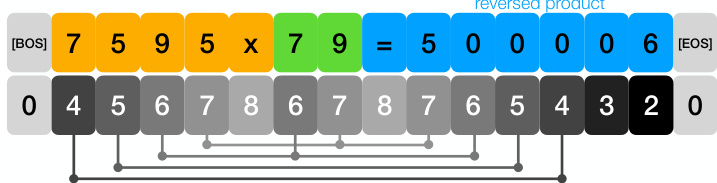

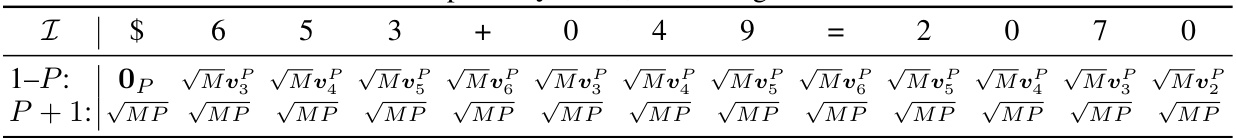

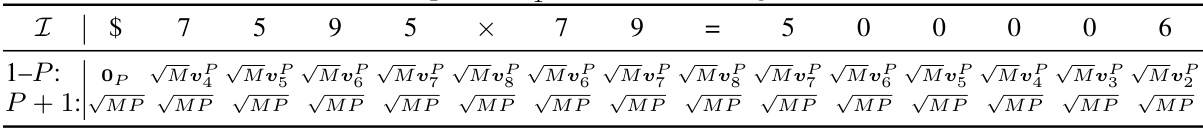

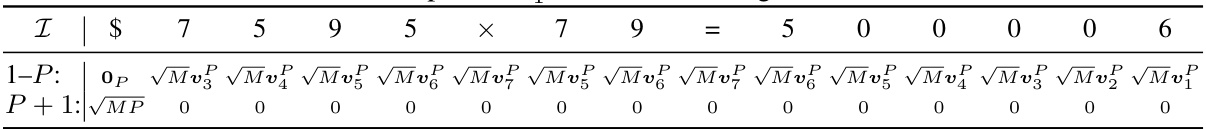

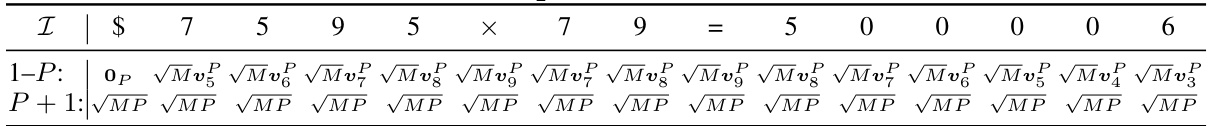

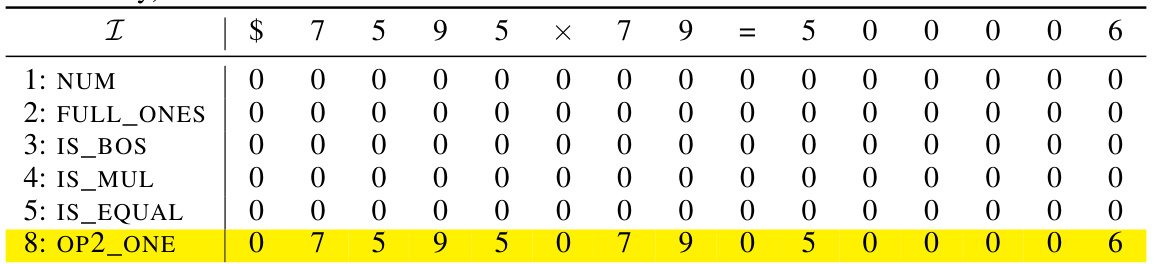

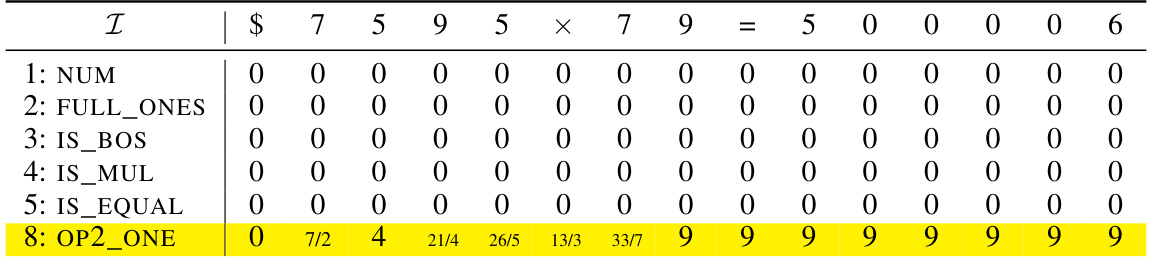

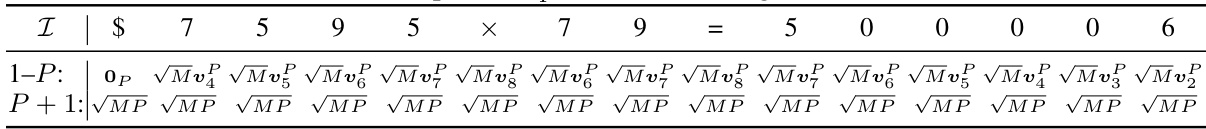

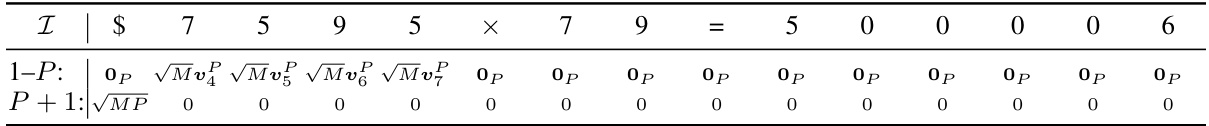

🔼 This figure illustrates the position coupling method for the decimal integer addition task. The input sequence is preprocessed using reversed response format, zero-padding and BOS/EOS tokens. The tokens are grouped into three categories: first operand and ‘+’, second operand, and ‘=’ and response (sum). The figure displays how position IDs are assigned to the same significance digits in each group. The same position ID is given to relevant digits to help the model to understand the structure of addition irrespective of the length of the input sequence.

read the caption

Figure 2: Position coupling for decimal integer addition task, displaying 653 + 49 = 702 with appropriate input formats. The starting position ID ‘6’ is an arbitrarily chosen number.

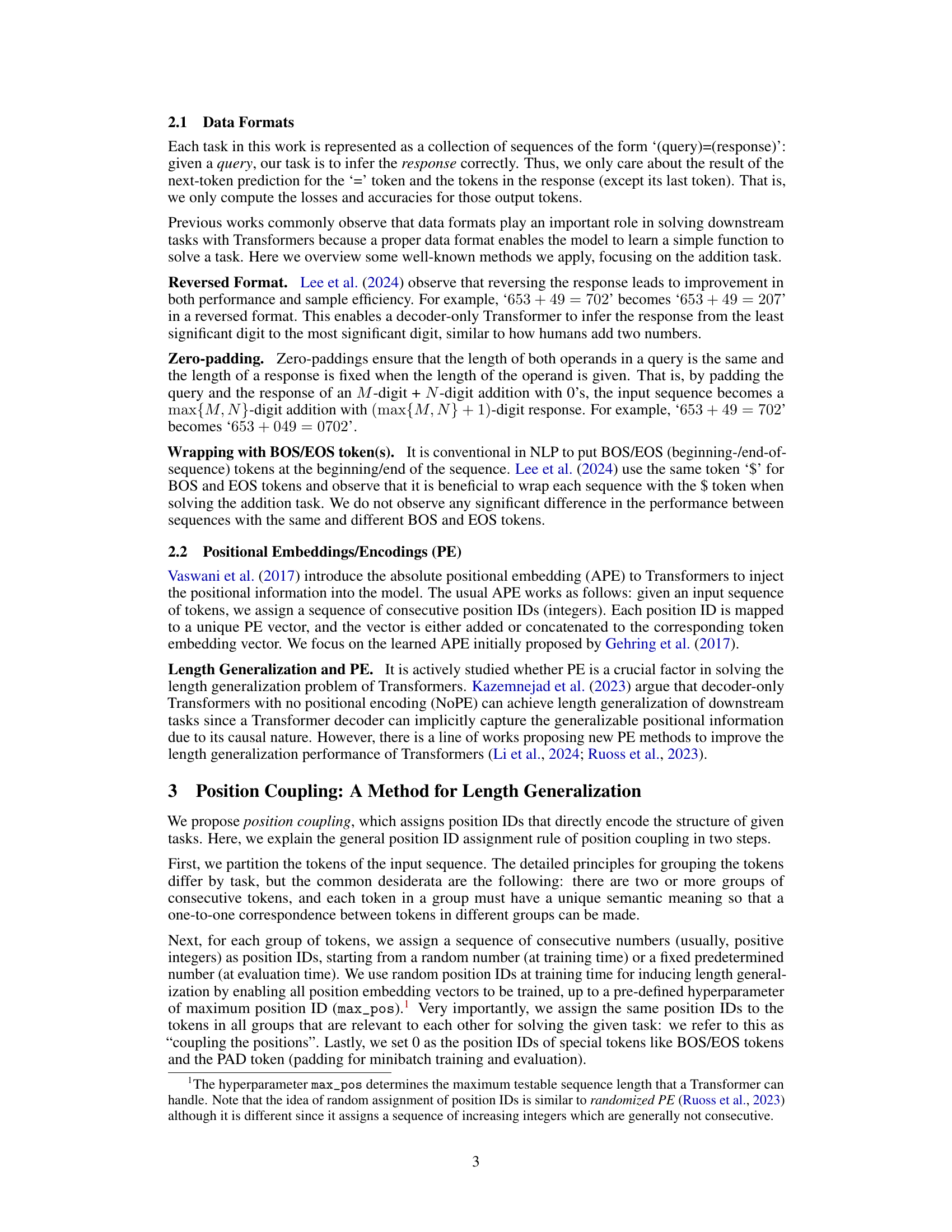

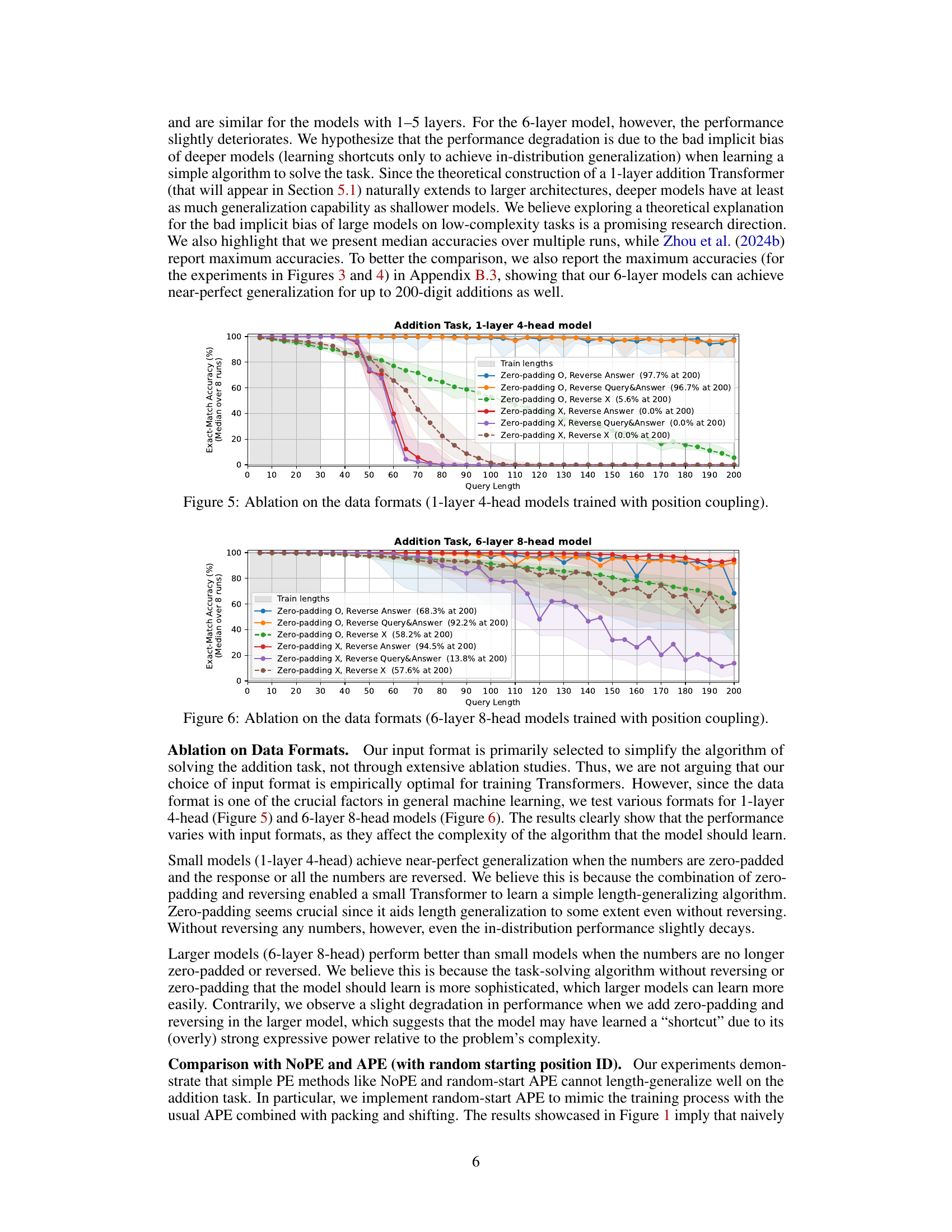

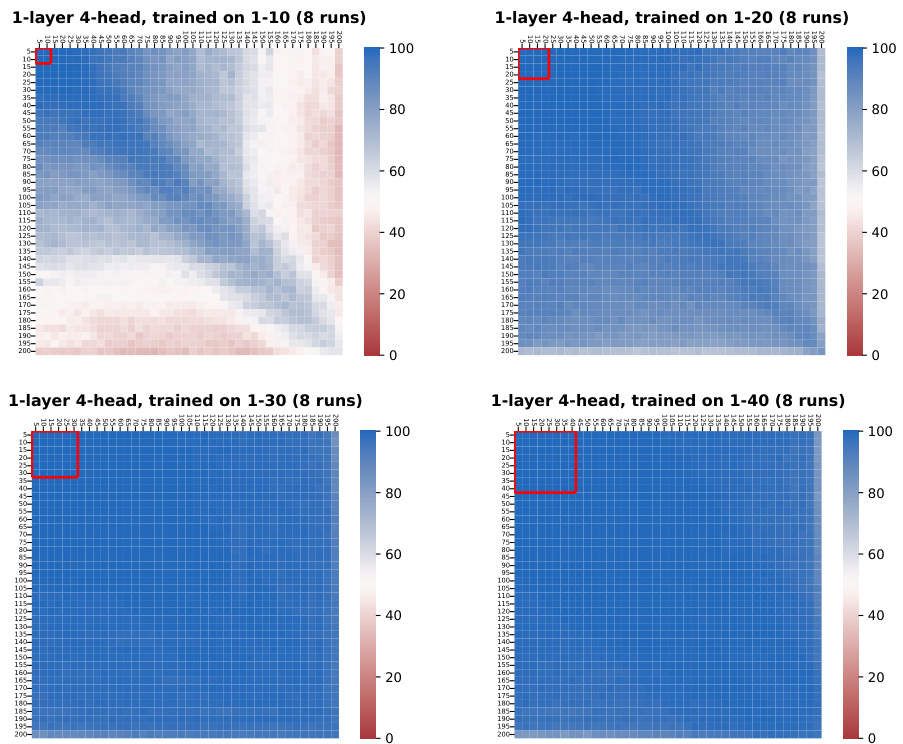

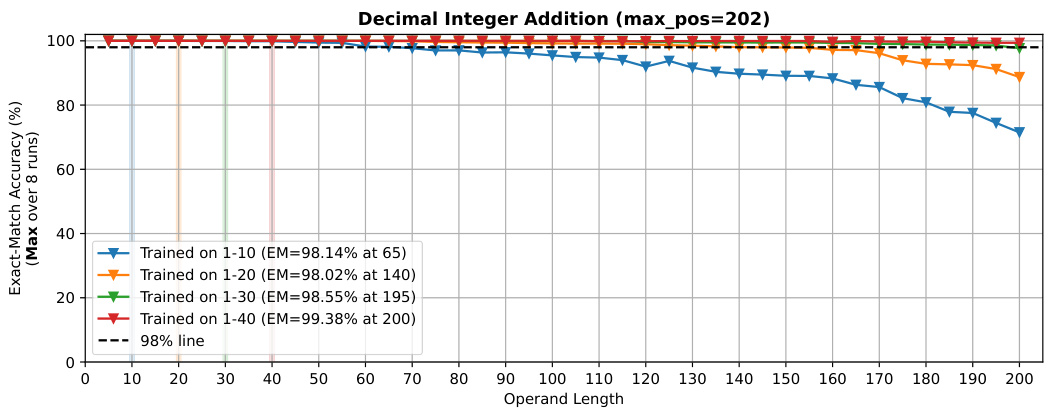

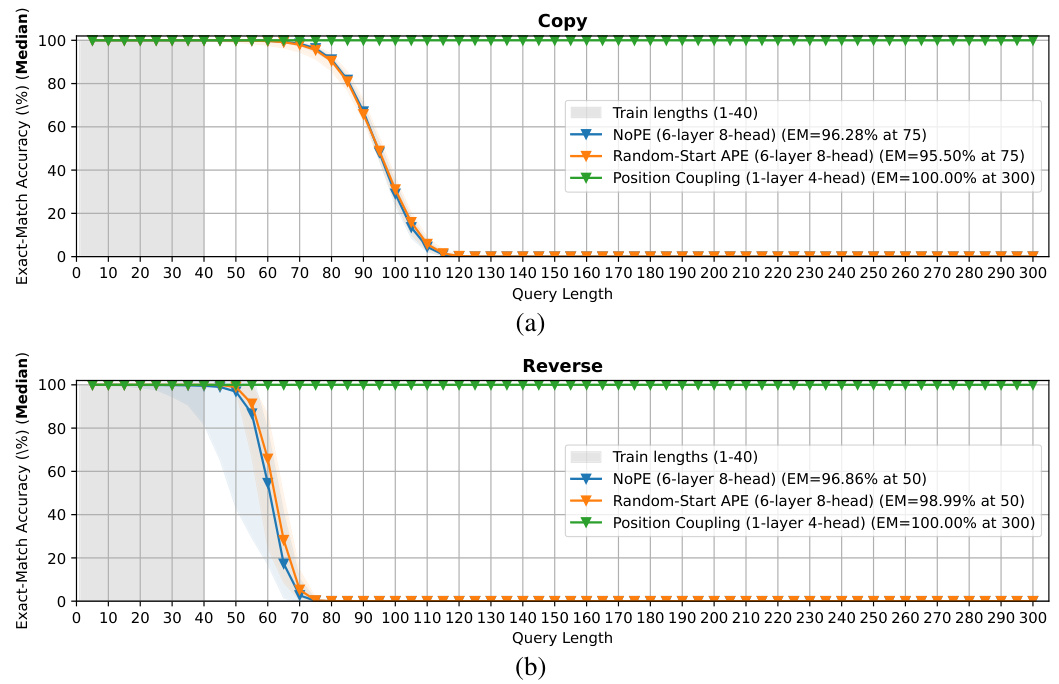

🔼 This figure shows the result of ablation studies on the trained operand lengths for 1-layer 4-head Transformer models. The models were trained on integer addition problems with a maximum operand length varying from 10 to 40 digits, and their performance was evaluated on addition problems with operand lengths up to 200 digits. The graph shows the exact match accuracy (median over 8 runs) as a function of operand length, with different lines representing models trained on different operand lengths. The shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals. The results indicate that longer training sequences lead to longer generalizable lengths in the addition task.

read the caption

Figure 3: Ablation on the trained operand lengths (1-layer 4-head models).

🔼 The figure compares several methods for improving length generalization in the integer addition task, including the proposed Position Coupling. The x-axis shows the operand length, and the y-axis shows the exact-match accuracy. The plot demonstrates that Position Coupling significantly outperforms existing methods (NOPE, Random-Start APE, Index Hinting) in terms of accuracy for longer sequences.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 The figure shows the result of the experiment on the integer addition task. It compares the performance of different methods for length generalization in the integer addition task. The methods compared are position coupling (the proposed method), index hinting with APE, index hinting with NoPE, and APE with a random starting position ID. The x-axis represents the operand length, and the y-axis represents the exact-match accuracy. The figure shows that position coupling achieves more than 95% accuracy for up to 200-digit additions when trained only on up to 30-digit additions.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 The figure shows the results of different methods for improving the length generalization of arithmetic Transformers. The x-axis represents the operand length, and the y-axis represents the exact-match accuracy. The plot compares the performance of position coupling (the proposed method) against several baseline methods, including different positional encoding schemes and index hinting, on the task of integer addition. Position coupling demonstrates significantly better length generalization than the baselines.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 The figure shows a comparison of different methods for achieving length generalization in the integer addition task. The x-axis represents the operand length, and the y-axis represents the exact-match accuracy. The plot compares the performance of the proposed method (position coupling) against existing techniques like index hinting with and without positional encoding (APE and NoPE). The results demonstrate that position coupling significantly outperforms the other methods, achieving over 95% accuracy for operand lengths up to 200 digits when trained only on lengths up to 30 digits.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 The figure shows the result of the N × 2 multiplication task. The x-axis represents the operand length (N), while the y-axis shows the exact-match accuracy (%). Different lines represent different models using position coupling with varying numbers of layers (1-4 layers) and two baselines (NoPE and Random-Start APE). The plot demonstrates the ability of the position coupling method to generalize to longer sequences than those seen during training, exceeding the performance of baseline approaches.

read the caption

Figure 8: N × 2 multiplication task, trained on sequences of length 1–40.

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of position coupling for the decimal integer addition task. It shows how position IDs are assigned to tokens in an input sequence representing an addition problem (653 + 49 = 702). The key is that tokens representing digits of the same place value (ones, tens, hundreds, etc.) in different numbers (operands and sum) are assigned the same position ID. This embedding of task structure helps the model generalize better to longer addition problems than it was trained on. The figure demonstrates this by representing the input as ‘$653+049=2070$’, where the response is reversed and zero-padded. A random starting position ID (6 in this example) is used to prevent overfitting to specific positional encodings.

read the caption

Figure 2: Position coupling for decimal integer addition task, displaying 653 + 49 = 702 with appropriate input formats. The starting position ID ‘6’ is an arbitrarily chosen number.

🔼 The figure compares several methods for length generalization in the integer addition task, including the proposed position coupling method. The x-axis shows operand length, and the y-axis represents the exact-match accuracy. The plot showcases how position coupling significantly outperforms other methods in handling longer sequences.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 The figure shows the results of experiments on the integer addition task. Different methods for achieving length generalization are compared, including the proposed position coupling method and existing methods such as index hinting. The graph plots the exact-match accuracy against the operand length. The results show that position coupling significantly improves length generalization capabilities.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 The figure compares the performance of different methods for achieving length generalization in the integer addition task. The methods include Position Coupling (the proposed method), Index Hinting with and without positional encoding (NoPE), and existing methods like NOPE and Random-Start APE. The graph displays the exact-match accuracy for different operand lengths, illustrating the superior performance and length generalization capabilities of Position Coupling.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 The figure shows the result of different methods for length generalization in integer addition. The x-axis represents the length of operands, and the y-axis represents the exact-match accuracy. The graph compares the performance of position coupling (the proposed method) with other methods like NOPE, random APE, and index hinting, demonstrating that position coupling significantly improves length generalization for integer addition task.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 The figure shows the ablation study on the trained operand lengths for 1-layer 4-head Transformer models trained with position coupling. The models were trained on different lengths of addition problems (1-10, 1-20, 1-30, and 1-40 digits), and their performance was evaluated on addition problems with operand lengths up to 200 digits. The graph shows the exact match accuracy (%) median over 8 runs, with 95% confidence intervals represented by the light shaded area. The results demonstrate that longer training sequences (more digits) lead to longer generalizable lengths, meaning the models trained on longer sequences can successfully generalize to longer sequences during testing. The 95% line indicates that the model is considered to successfully generalize to a certain length if its median EM accuracy exceeds 95%.

read the caption

Figure 3: Ablation on the trained operand lengths (1-layer 4-head models).

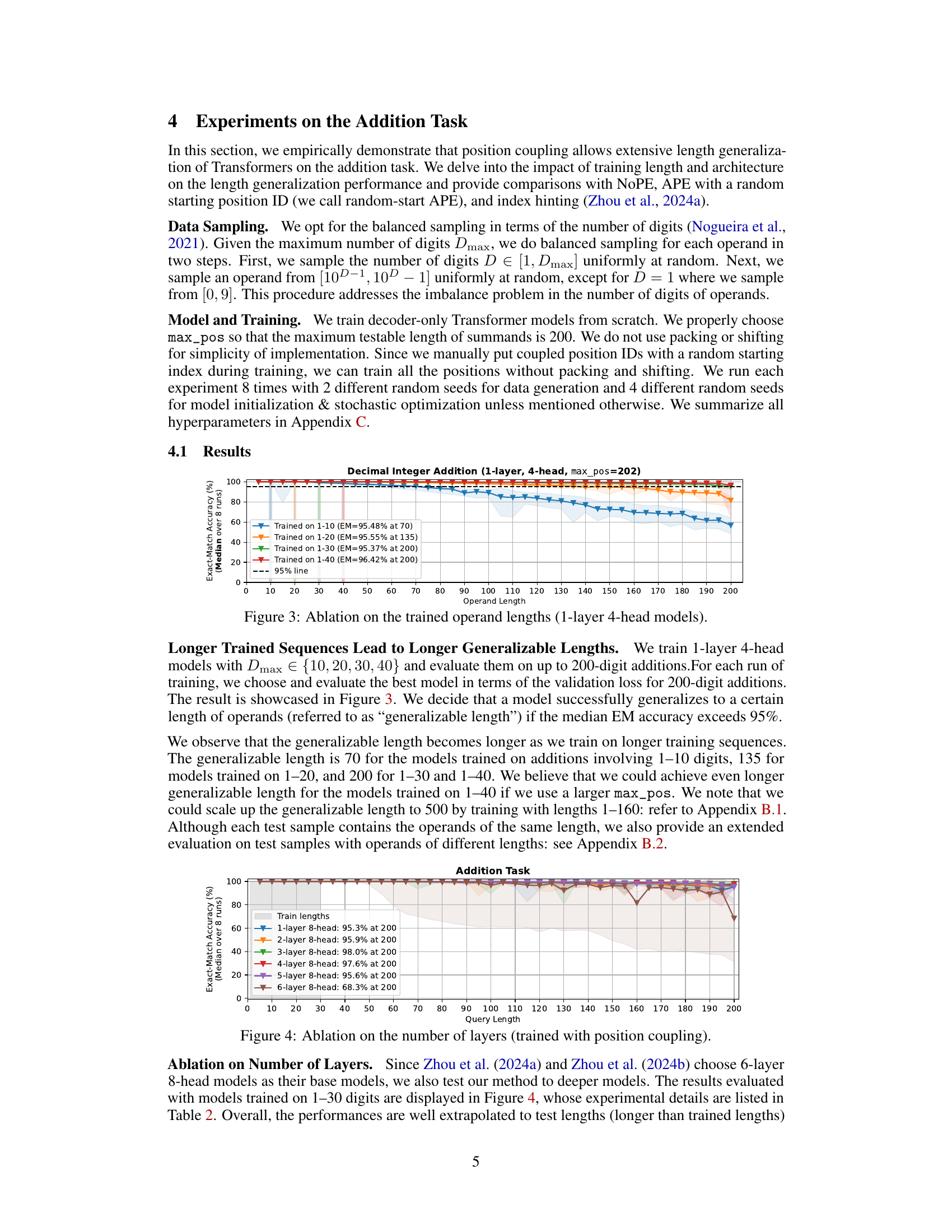

🔼 This figure shows the ablation study on the number of layers in the Transformer model when trained with position coupling. The x-axis represents the query length (number of digits in the addition problem), and the y-axis represents the exact-match accuracy (median over 8 runs). Different colored lines represent different numbers of layers in the model (1-layer to 6-layer). The shaded region indicates the training length. The figure demonstrates how the accuracy changes with varying numbers of layers and how the length generalization capability differs for different model depths.

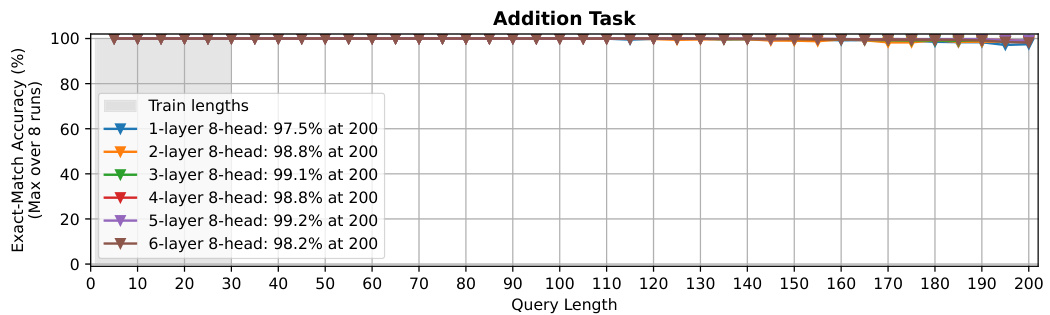

read the caption

Figure 4: Ablation on the number of layers (trained with position coupling).

🔼 The figure shows the comparison of different methods for length generalization in integer addition. It plots the exact-match accuracy against the operand length for various Transformer models and training methods, including position coupling (the proposed method), index hinting, and models without positional encoding. Position coupling demonstrates significantly better length generalization compared to others, achieving over 95% accuracy on 200-digit addition, trained only on data up to 30 digits.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of position coupling for the task of decimal integer addition. It shows how position IDs are assigned to the tokens in the input sequence (‘query=response’). Instead of assigning unique IDs to each token, position coupling groups ‘relevant’ tokens, such as digits of the same significance in the numbers being added, and assigns them the same position ID. This helps the transformer model learn the structure of the addition task and generalize to longer sequences.

read the caption

Figure 2: Position coupling for decimal integer addition task, displaying 653 + 49 = 702 with appropriate input formats. The starting position ID ‘6’ is an arbitrarily chosen number.

🔼 The figure compares several methods for improving length generalization in the integer addition task, including the proposed position coupling method. It shows the exact-match accuracy for various models trained on different lengths of input sequences (1-30 digits) and tested on much longer sequences (up to 200 digits). The results demonstrate the superior length generalization capability of the proposed position coupling approach compared to existing methods such as index hinting with and without absolute positional embeddings.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 This figure compares different methods for achieving length generalization in the integer addition task, focusing on the exact-match accuracy. It shows that the proposed ‘position coupling’ method significantly outperforms existing methods like index hinting and those without positional encoding, achieving high accuracy even with significantly longer sequences than those used for training.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different methods for achieving length generalization in the integer addition task. The x-axis represents the operand length, and the y-axis represents the exact-match accuracy. The figure shows that position coupling significantly outperforms other methods, such as NoPE (no positional encoding) and index hinting, achieving over 95% accuracy even with operand lengths up to 200 digits when trained on much shorter sequences (up to 30 digits). Error bars showing 95% confidence intervals are also included.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 The figure shows the results of an experiment on integer addition using different length generalization methods. The x-axis represents the operand length, and the y-axis represents the exact-match accuracy. The figure compares the performance of position coupling (the proposed method) against several baselines, including NoPE (no positional encoding), APE (absolute positional embedding) with and without a random start, and Index Hinting. Position coupling shows significantly better length generalization than the baselines, achieving over 95% accuracy even for additions with 200 digits (trained on 1-30 digits).

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of position coupling for the decimal integer addition task. It shows how position IDs are assigned to tokens in the input sequence (‘query’), which includes the two operands, the addition operator, the equals sign, and the reversed sum. Crucially, position coupling assigns the same position ID to digits of the same significance (e.g., ones digits, tens digits) in the different parts of the input. This helps the model to learn the inherent structure of the addition task and generalize to longer sequences than those seen during training. The choice of starting position ID (6 in this example) is arbitrary. Zero-padding and reversed format are used for data formatting.

read the caption

Figure 2: Position coupling for decimal integer addition task, displaying 653 + 49 = 702 with appropriate input formats. The starting position ID ‘6’ is an arbitrarily chosen number.

🔼 The figure compares the performance of different methods for length generalization in the integer addition task. It shows the exact-match accuracy for various models trained on different lengths of integer addition problems and tested on increasingly longer sequences. The key takeaway is that the proposed ‘position coupling’ method significantly outperforms other methods in generalizing to much longer sequences than seen during training.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 The figure shows a comparison of different methods for achieving length generalization in the integer addition task. The x-axis represents the operand length, and the y-axis represents the exact-match accuracy. The plot compares the performance of position coupling (the proposed method) against several baselines, including NoPE (no positional encoding), random-start APE (absolute positional embedding with a randomized starting point), and index hinting. The results demonstrate that position coupling significantly outperforms the baselines in terms of length generalization, achieving over 95% accuracy even for operand lengths of up to 200 digits (a 6.67x extrapolation of the training length).

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 The figure compares different methods for length generalization in the integer addition task. It shows the exact-match accuracy of various models (including the proposed ‘position coupling’ method) trained on shorter sequences (1-30 digits) and tested on increasingly longer sequences (up to 200 digits). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of position coupling in achieving high accuracy even on much longer sequences than those seen during training.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 This figure compares the performance of several methods for length generalization in the integer addition task. The methods compared are: Position Coupling (the proposed method), NOPE (no positional encoding), Random-Start APE (absolute positional embedding with a random starting position ID), and Index Hinting. The plot shows the exact-match accuracy for each method at different operand lengths, demonstrating the superior performance of Position Coupling in generalizing to longer sequences.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

🔼 The figure compares several methods for achieving length generalization in the integer addition task, plotting exact-match accuracy against operand length. It shows that the proposed ‘Position Coupling’ method significantly outperforms other methods like index hinting and those without positional encoding, achieving high accuracy even with significantly longer sequences than those seen during training.

read the caption

Figure 1: Methods for Length Generalization in the Integer Addition Task. We report exact-match (EM) accuracies (markers: medians over experiments; light area: 95% confidence intervals). We employ the reversed format and zero-paddings (Lee et al., 2024) into the input sequence. With our proposed position coupling, we achieve more than 95% exact-match accuracy for up to 200-digit additions with decoder-only Transformers trained on up to 30-digit additions. For index hinting (Zhou et al., 2024a), we separately test absolute positional embedding (APE) with a random starting position ID (mimicking the original implementation by Zhou et al. (2024a)) and without positional encoding (NoPE) (Kazemnejad et al., 2023) (as tested by Zhou et al. (2024b)).

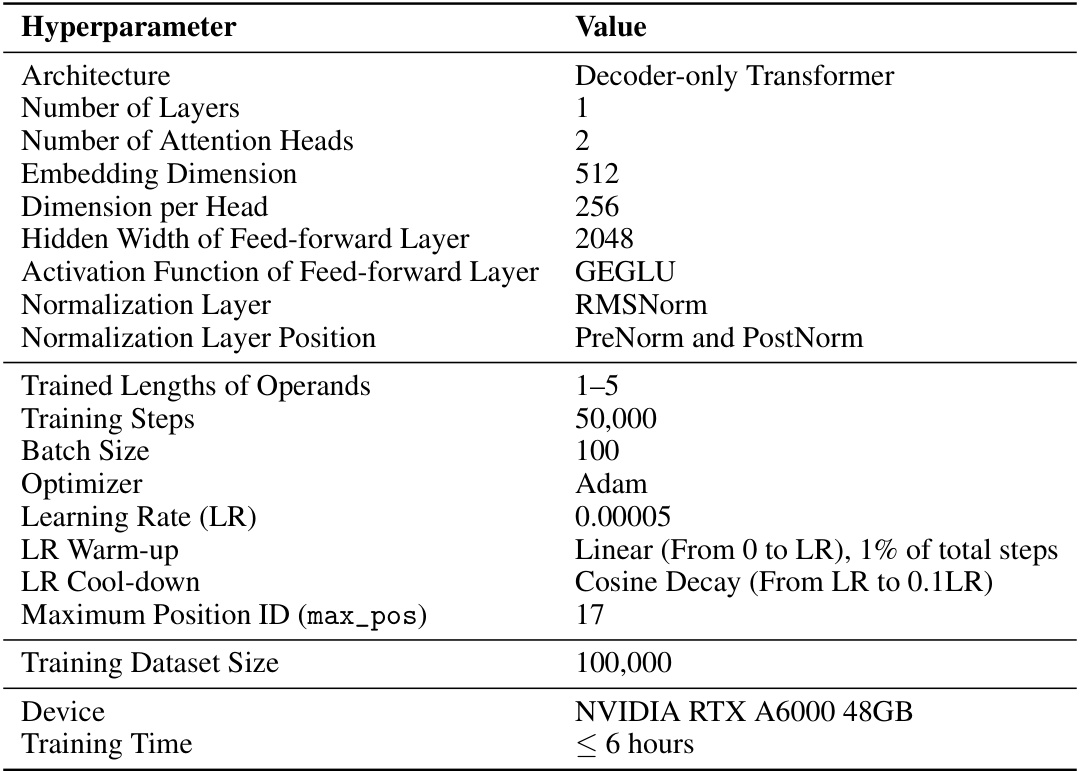

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the hyperparameters used for training the decoder-only transformer models on the decimal integer addition task. It shows the settings used for experiments comparing the impact of different training lengths (1-10, 1-20, 1-30, and 1-40 digits) on the model’s ability to generalize to longer sequences. The table details architecture choices (number of layers, heads, dimensions, etc.), activation functions, normalization methods, optimization parameters (optimizer, learning rate schedule), training and evaluation data size, device used for training, and the total training time.

read the caption

Table 1: Hyperparameter summary for decimal integer addition task: comparison between trained lengths (Figures 3 and 14).

🔼 This table details the hyperparameters used for training the decoder-only transformer model on the decimal integer addition task, specifically focusing on achieving generalization up to a sequence length of 500. It includes specifications for the model architecture (layers, heads, dimensions), activation functions, normalization, optimization parameters (optimizer, learning rate schedule), training settings (steps, batch size), dataset size, the device used for training, and the training time.

read the caption

Table 3: Hyperparameter summary for decimal integer addition task: generalization up to length 500 (Figure 12).

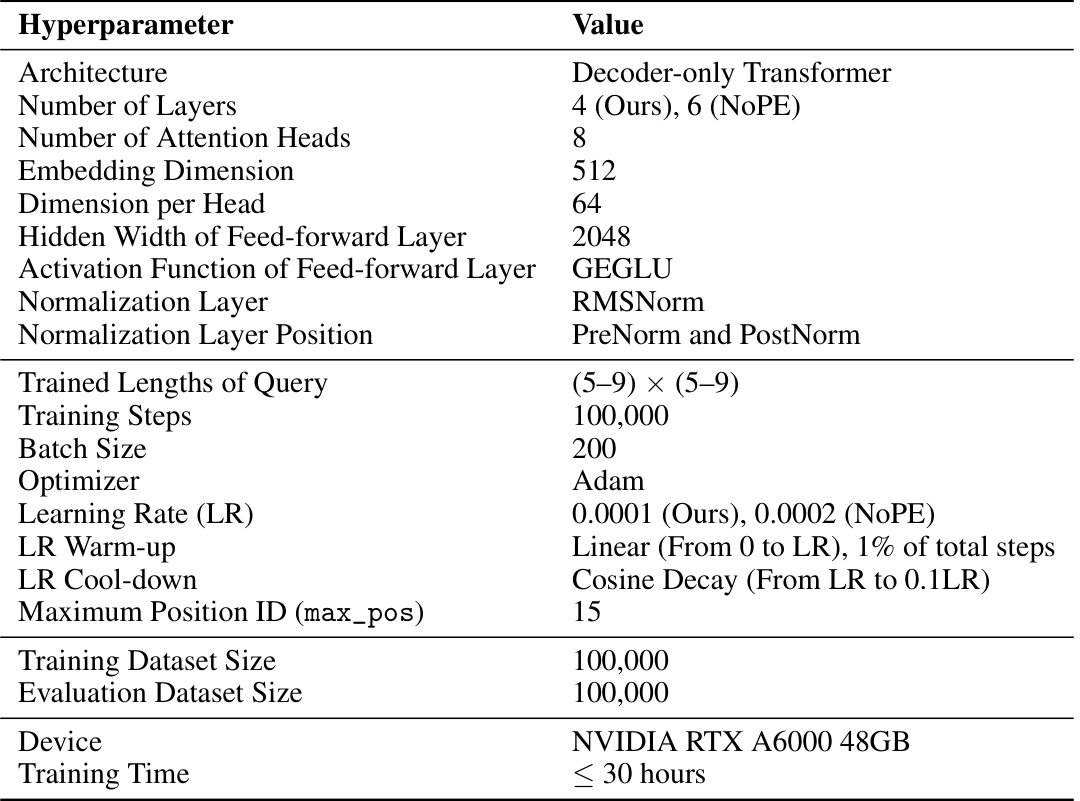

🔼 This table details the hyperparameters used for training decoder-only transformer models on the decimal integer addition task. It focuses specifically on the impact of varying the number of layers, comparing results illustrated in Figures 4 and 15 of the paper. The hyperparameters include architectural choices (number of layers and heads, embedding and hidden dimensions), training settings (optimizer, learning rate, warm-up and cool-down schedules, and training steps), and the maximum position ID.

read the caption

Table 4: Hyperparameter summary for decimal integer addition task: comparison between the number of layers (Figures 4 and 15).

🔼 This table details the hyperparameters used for training the N × 2 multiplication task. It includes specifications for the model architecture (decoder-only transformer), the number of layers and attention heads, embedding dimensions, hidden layer widths, activation functions, normalization methods, training steps, batch size, optimizer, learning rate, learning rate warm-up and cool-down schedules, maximum position ID, training dataset size, evaluation dataset size, device used, and training time. The table compares hyperparameters used for different model depths for both the proposed position coupling approach and baseline models (NoPE and Random-start APE).

read the caption

Table 5: Hyperparameter summary for N × 2 multiplication task (Figure 8).

🔼 This table presents the hyperparameters used for training the decoder-only transformer models on the decimal integer addition task. It compares the results obtained from different trained lengths of operands. It includes details about the model architecture, training settings, optimization parameters, and data used for training and evaluation. The table shows that the number of layers, attention heads, embedding dimension, feed-forward layer size, and other hyperparameters were kept constant across different training lengths. However, the training dataset size was adjusted to accommodate different operand lengths. The table is essential for understanding the experimental setup and reproducing the results.

read the caption

Table 1: Hyperparameter summary for decimal integer addition task: comparison between trained lengths (Figures 3 and 14).

🔼 This table details the hyperparameters used in the experiments comparing the performance of different numbers of layers in a decoder-only transformer model for the decimal integer addition task. The results of these experiments are shown in Figures 4 and 15 of the paper. The table lists hyperparameters such as architecture, number of layers, attention heads, embedding dimension, feed-forward layer dimensions, activation function, normalization techniques, training steps, batch size, optimizer, learning rate schedule, maximum position ID, dataset sizes, device, and training time. It provides a comprehensive overview of the experimental setup to ensure reproducibility.

read the caption

Table 2: Hyperparameter summary for decimal integer addition task: comparison between the number of layers (Figures 4 and 15).

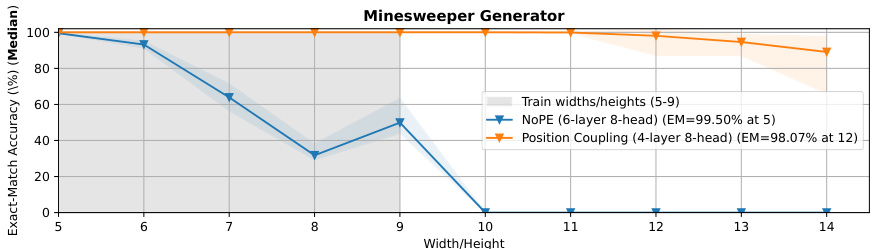

🔼 This table details the hyperparameters used for training the minesweeper generator model using the position coupling approach. It includes information on the model architecture (decoder-only Transformer), number of layers and attention heads, embedding dimensions, and optimizer, as well as training-related parameters such as training steps, batch size, and learning rate schedule. It also specifies the size of the training and evaluation datasets, the hardware used (NVIDIA RTX A6000 48GB), and the approximate training time.

read the caption

Table 8: Hyperparameter summary for minesweeper generator task (Figures 10 and 21).

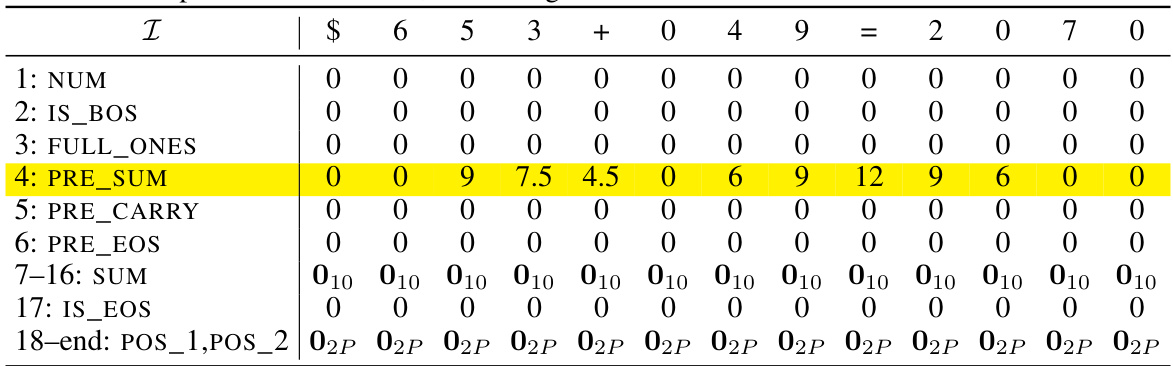

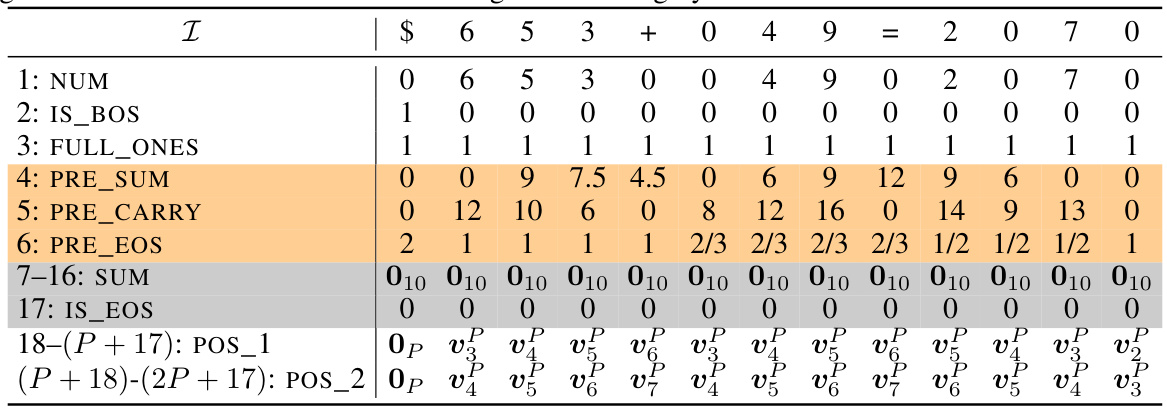

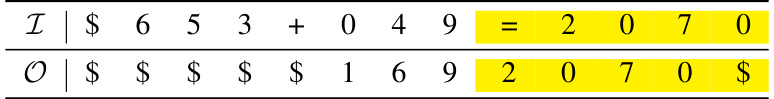

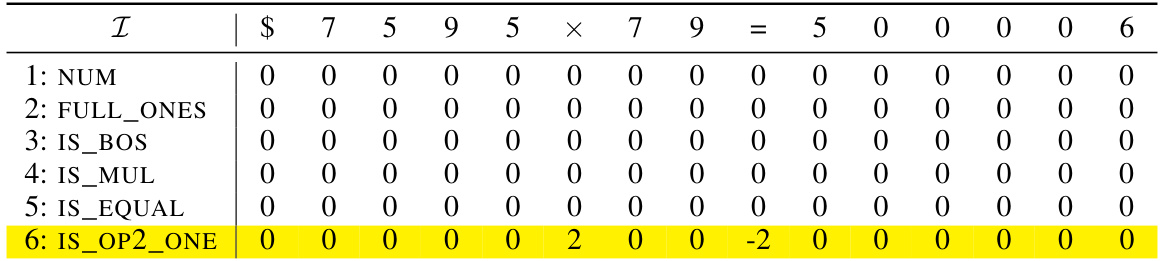

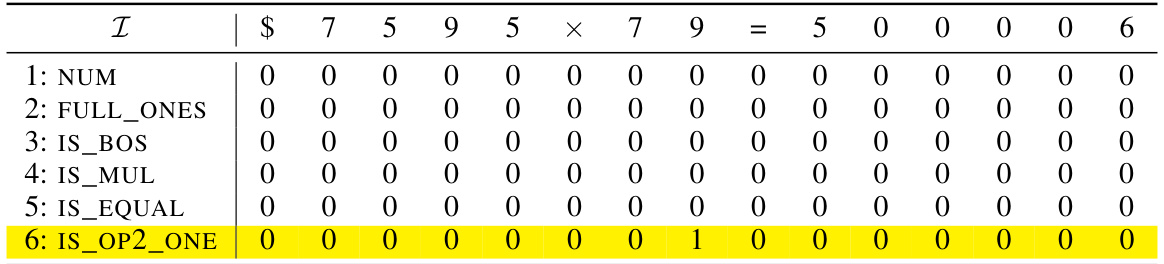

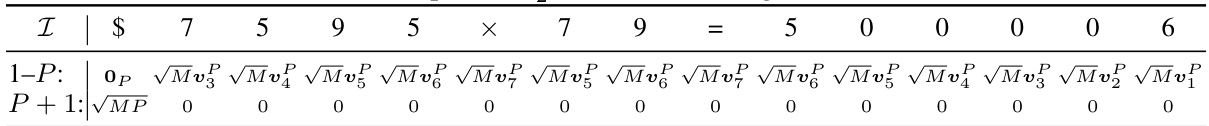

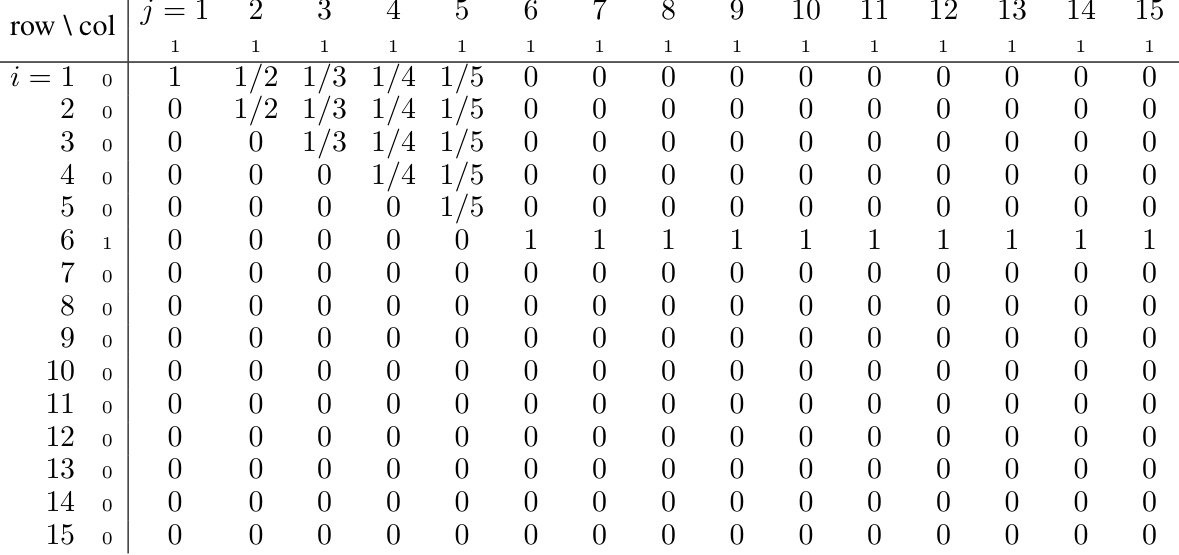

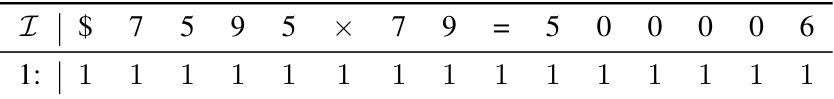

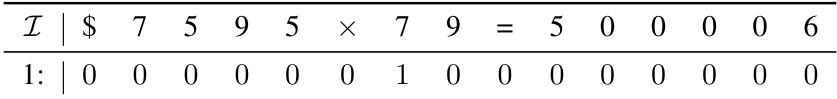

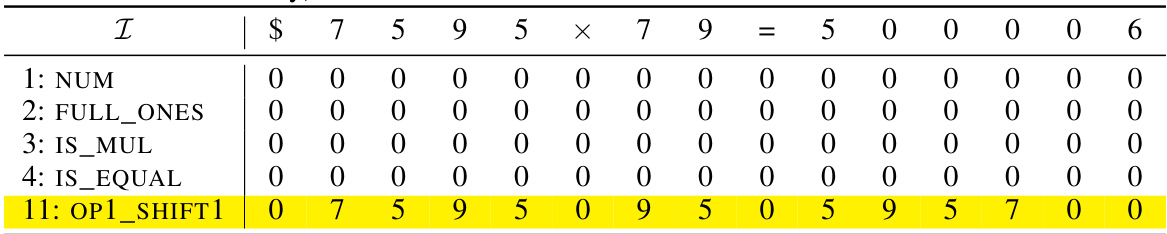

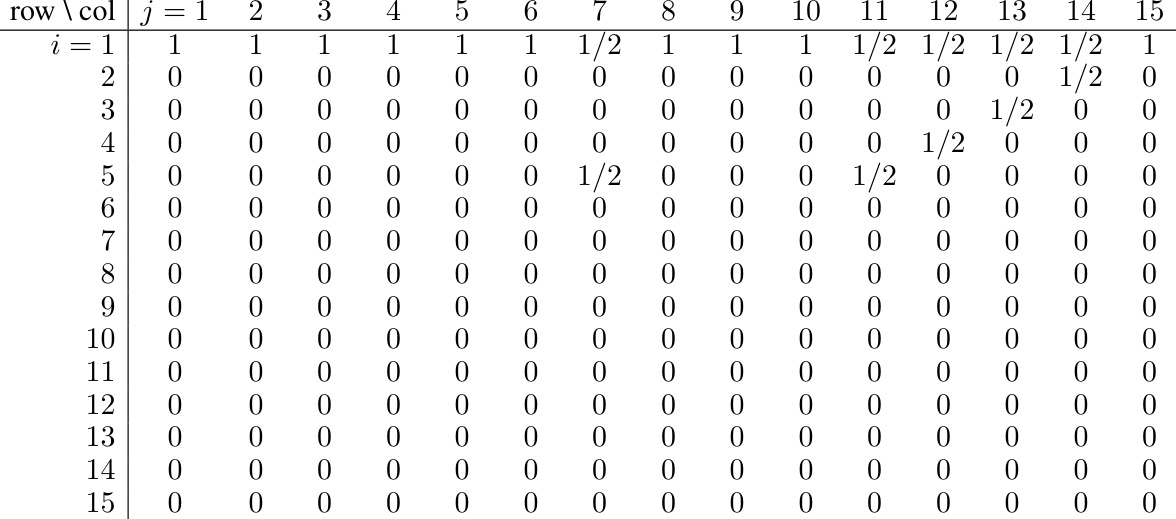

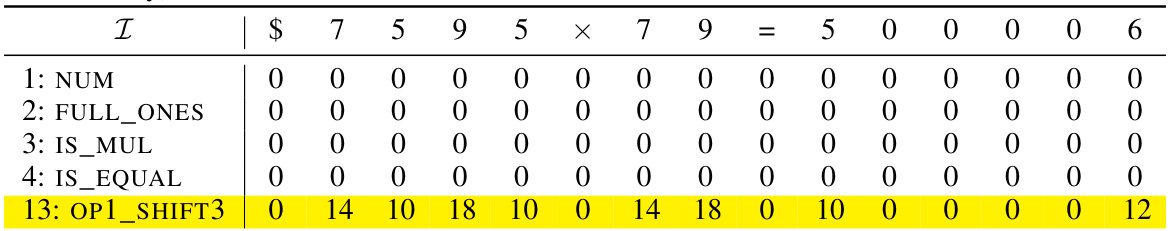

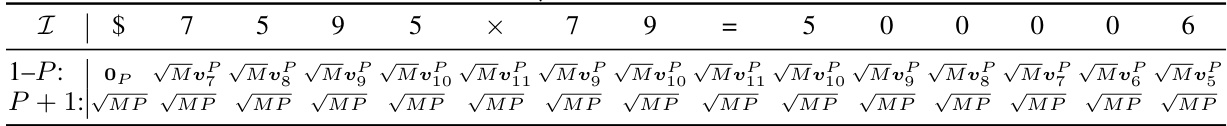

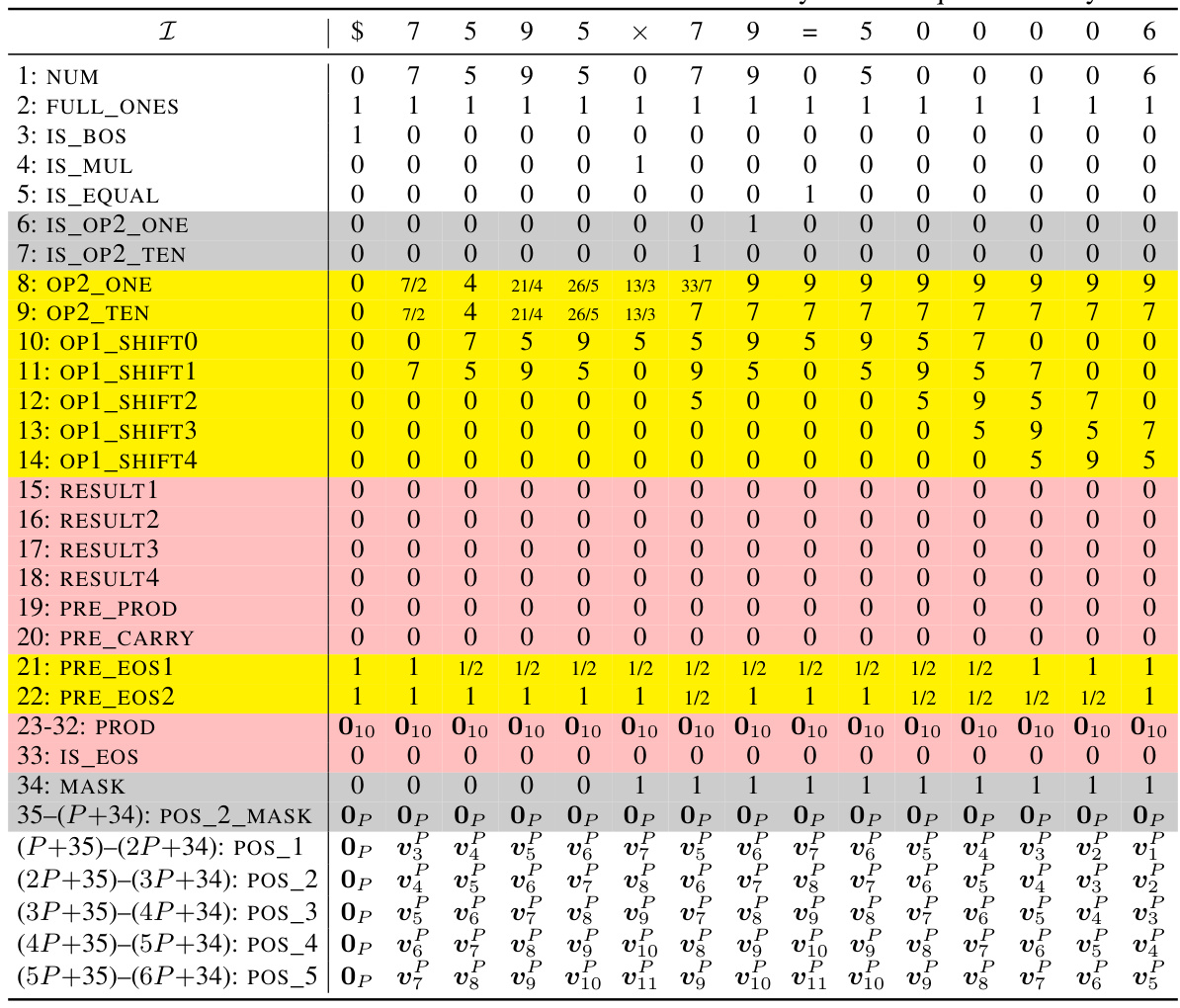

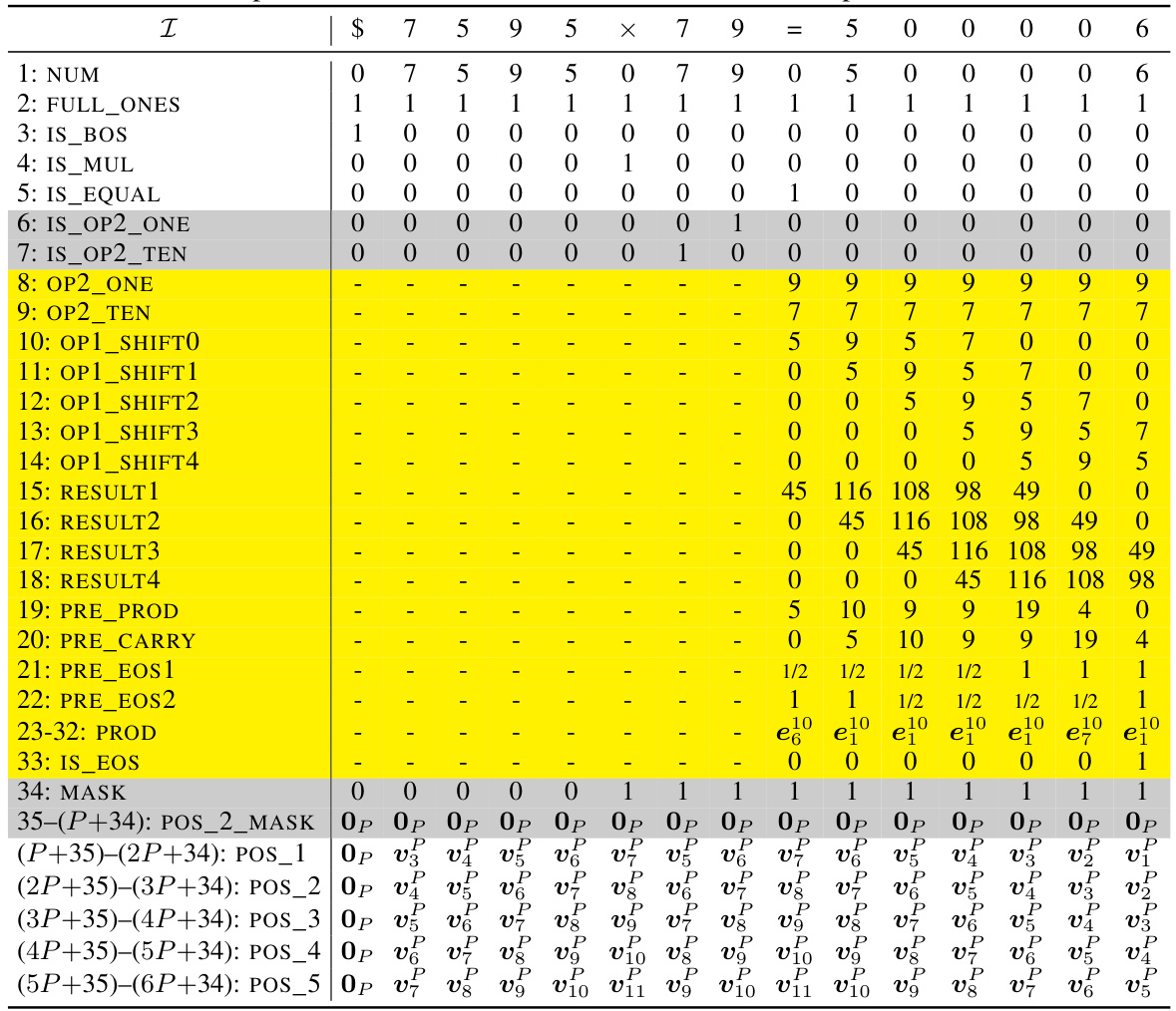

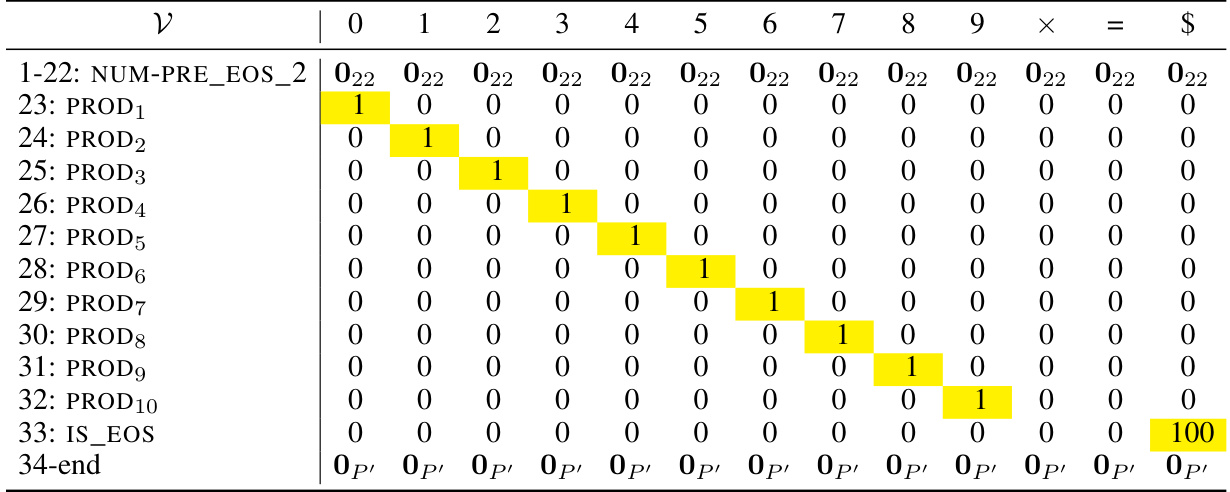

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix used in the formal construction of the addition Transformer with position coupling. It illustrates how the input sequence, including special tokens and digits, is represented as a matrix with various dimensions for different features (NUM, IS_BOS, etc.). Positional information will be added in the next steps (grayed out).

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix used in the formal construction of the addition Transformer with position coupling. It illustrates how token embeddings and position embeddings are combined. The table demonstrates the encoding for the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070$’ with a starting position ID of 2. Some rows (shown in gray) will be filled in later steps of the encoding process.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix used in the formal construction of the addition transformer with position coupling described in Appendix E. The matrix represents the input to the transformer, and the rows represent different dimensions or features of the input tokens. The columns represent the tokens in the sequence, and the entries in the table indicate the values assigned to each dimension for each token. The gray rows represent dimensions that are initialized to zero and will be filled in by subsequent layers of the transformer.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding of the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’ for the addition task. The encoding uses 17 dimensions: NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES, PRE_SUM, PRE_CARRY, PRE_EOS, SUM, IS_EOS and POS_1,POS_2 which represent the number itself, beginning of sequence flag, all ones vector, prepared sum without considering carries, prepared carry, prepared end of sequence flag, the sum, end of sequence flag, and position embedding respectively. The starting position ID is 2, and gray rows will be populated in later steps. The table illustrates how the input tokens are represented in different dimensions.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding of the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’ for the addition task using position coupling. The starting position ID is 2. Each row represents a specific dimension of the embedding vector, such as NUM (numerical value of the token), IS_BOS (beginning-of-sequence token), FULL_ONES (always 1), PRE_SUM (sum preparation), PRE_CARRY (carry prediction), PRE_EOS (end-of-sequence prediction). The SUM (7-16) and POS_1, POS_2 (positional information) are initially filled with zeros, and will be populated later in the process. The table shows how the input tokens are represented numerically in the different dimensions before the Transformer processes them.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix for the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’, used in the formal construction of the addition transformer. The matrix has 17 dimensions representing different features. The rows show different dimensions in the encoding such as number, start of sequence, full ones, pre-sum, pre-carry, pre-EOS, sum, IS_EOS and positional embeddings.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix for the input sequence “$653 + 049 = 2070”. The encoding matrix combines token embeddings and position embeddings. The table illustrates how the different dimensions represent various features (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES, PRE_SUM, PRE_CARRY, PRE_EOS, SUM, IS_EOS, POS_1, POS_2). The gray rows indicate dimensions that will be filled later in the process.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix X(0) for the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’, where the starting position ID is 2. The matrix has 17 dimensions and the number of columns corresponds to the length of the input sequence. The rows represent different features of the input tokens and their positions (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES, PRE_SUM, PRE_CARRY, PRE_EOS, SUM, IS_EOS, POS_1, POS_2) while the columns represent the sequence of tokens in the input.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding process for the input sequence “$653 + 049 = 2070” in the decimal integer addition task. Each column represents a token in the sequence, and each row represents a specific dimension of the embedding vector. The table illustrates how the token embedding and position embedding are combined. The ‘NUM’ row shows the numerical value of each token, ‘IS_BOS’ indicates whether the token is the beginning-of-sequence marker, and ‘FULL_ONES’ has a value of ‘1’ for all tokens. The remaining rows represent intermediate calculations and positional information that will be used in later steps of the process. The grayed-out rows represent components of the embedding that will be filled out in later stages.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix X(0) for the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’. The matrix is constructed by concatenating token embeddings and position embeddings. Each column represents a token, and each row represents a dimension (e.g., NUM, IS_BOS, PRE_SUM, etc.). The grayed-out rows are initially zero and will be filled in later steps of the model’s computation.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding process for the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070. The encoding is a matrix where each column represents a token, and each row is a dimension (feature). The table shows the values of several dimensions, including numerical value (NUM), beginning of sequence (IS_BOS), a vector of ones (FULL_ONES), and initial values for the sum (PRE_SUM), carry (PRE_CARRY), and end of sequence (PRE_EOS). The remaining dimensions, shown as gray, will be filled in later steps of the encoding process.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence \$653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors \(v_k\) are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix X(0) for the input sequence “$653+049=2070”. The matrix is of size d x N, where d is the embedding dimension and N is the sequence length. Each column represents the embedding vector for a token, and each row represents a specific named dimension (e.g., NUM, IS_BOS, PRE_SUM, etc.). The table illustrates how the token embedding and position embedding are combined to create the input encoding. The gray rows represent dimensions which will be filled later in the process.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix for the integer addition task. The input sequence is represented, along with its associated position IDs. The rows represent different dimensions, such as the numerical value of the token (NUM), the beginning-of-sequence indicator (IS_BOS), a constant vector of ones (FULL_ONES), pre-calculated values for sums and carries, and the end-of-sequence indicator (IS_EOS). Positional information (POS_1, POS_2) is also included, though the values are omitted in the table and will be added later.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix X(0) for the input sequence representing the addition problem 653 + 49 = 702. The encoding uses 17 dimensions: NUM (the digit), IS_BOS (beginning-of-sequence), FULL_ONES (all ones), PRE_SUM (pre-sum), PRE_CARRY (pre-carry), PRE_EOS (pre-end-of-sequence), SUM (sum), and IS_EOS (end-of-sequence). The table illustrates how the token embeddings and positional embeddings are combined. Note that the gray rows in the table are placeholders and will be filled in later during the processing.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding for the input sequence “$653 + 049 = 2070”. The encoding matrix X(0) has dimensions d × N, where d is the embedding dimension and N is the sequence length. Each column in X(0) represents an embedding vector for a token, and each row represents a particular named dimension. The initial encoding is constructed by concatenating the token embedding and the position embedding. The table shows the initial values for some of the dimensions, with the gray rows representing dimensions that will be filled in later.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding for the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’, where the starting position ID is 2. The table demonstrates how the token embedding and position embedding are combined. The grayed-out rows represent dimensions that will be filled in later steps of the process. It illustrates the structure of the input data before it’s processed by the Transformer.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix X(0) for the input sequence ‘$653+049=2070’, which is used in the formal construction of the addition transformer with position coupling. The matrix is d x N, where d is the embedding dimension and N is the length of the input sequence. Each column represents an embedding vector for a token, and each row represents a specific named dimension (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES, PRE_SUM, PRE_CARRY, PRE_EOS, SUM, IS_EOS, POS_1, POS_2). The initial encoding is a concatenation of the token embedding and position embedding. The grayed-out rows are dimensions that will be filled later in the process.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix for the integer addition task. The input sequence is $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is 2. The table shows how the different dimensions of the encoding matrix represent various aspects of the input sequence, such as the numerical values, positional information, and special tokens. The grayed-out rows represent dimensions that are filled in later during the computation process.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix for the input sequence “$653 + 049 = 2070”. The encoding matrix is constructed by concatenating token embeddings and position embeddings. Each column represents an embedding vector for a token, and each row represents a particular named dimension (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES, PRE_SUM, PRE_CARRY, PRE_EOS, SUM, IS_EOS, POS_1, POS_2). The gray rows indicate dimensions that will be filled in later stages of processing.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix X(0) in the addition task. It demonstrates how token embeddings and position embeddings are combined to form the input encoding for a given input sequence. The table illustrates the values in various dimensions (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES, PRE_SUM, PRE_CARRY, PRE_EOS, SUM, IS_EOS, POS_1, POS_2) for each token in the input sequence. The gray shaded rows represent dimensions that will be filled in the later stages of processing.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

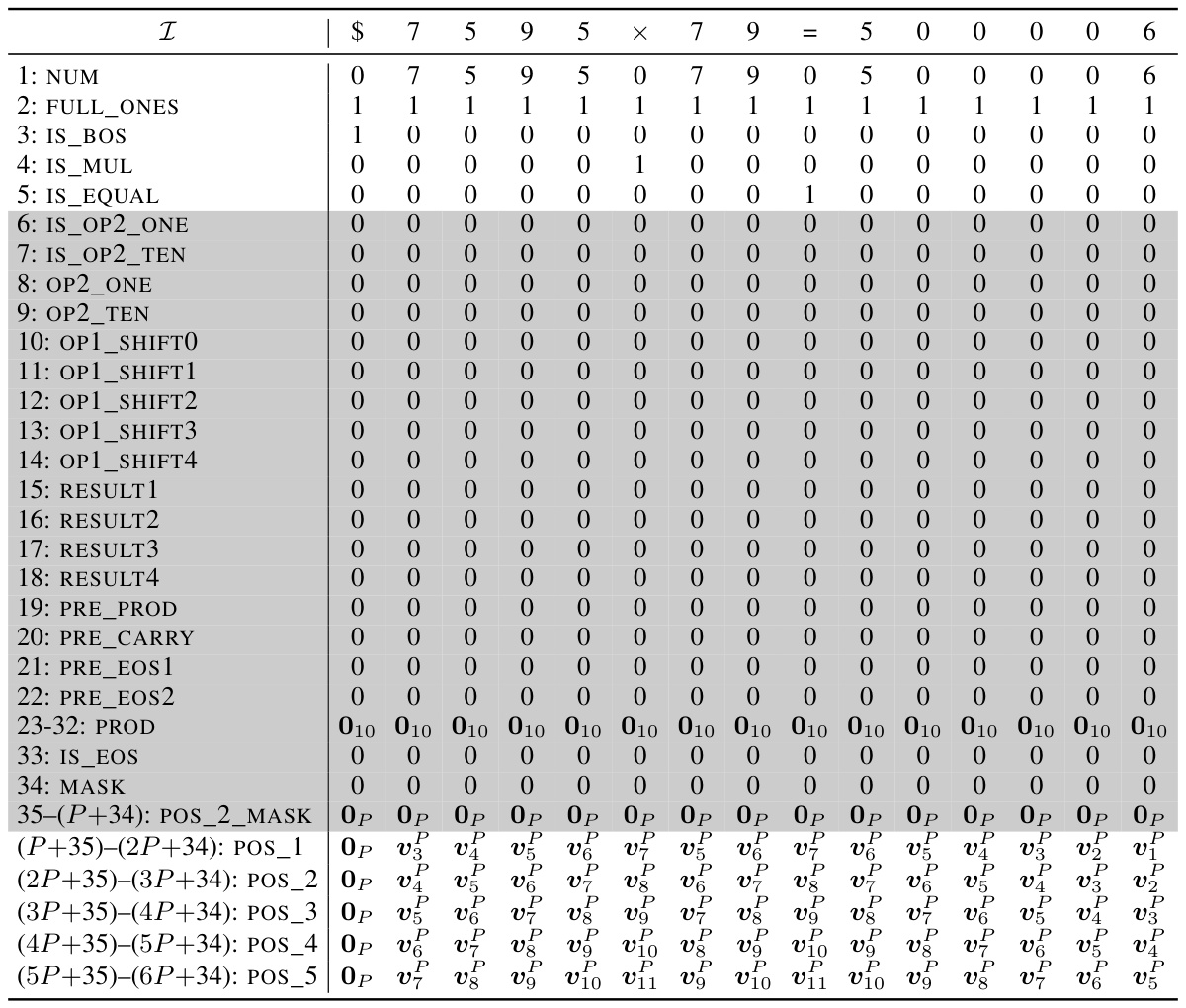

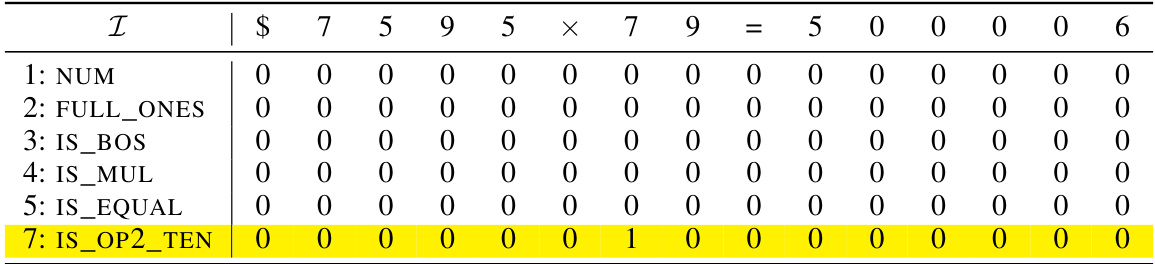

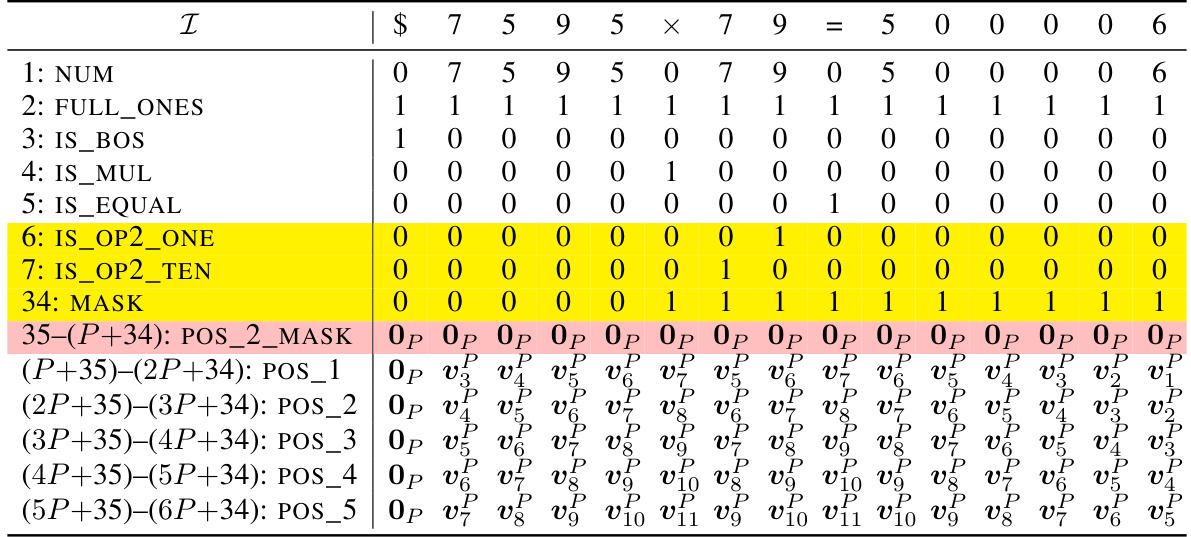

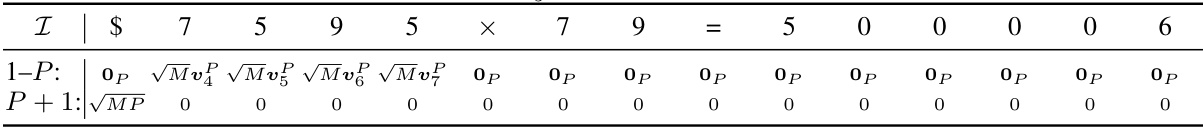

🔼 This table shows an example of the query matrix Q(2)X(1) for attention head 3 in the second transformer block for the N x 2 multiplication task. It’s derived from the embedding matrix X(1) (Table 49) using the weight matrix Q(2) (Equation 106) which is designed to extract the i-th least significant digit of the first operand when predicting the (i+1)-th least significant digit of the response (where i ranges from 0 to la+2, and 0 if i ≥ la). The matrix incorporates position embeddings and scaling by √M to facilitate selective attention.

read the caption

Table 60: Example of Q(2) X (1), continuing from Table 49.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix X(0) for the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’ used in the formal construction of the addition transformer with position coupling. The rows represent dimensions (features) of the embedding, including numerical values (NUM), markers for BOS (IS_BOS) and the end of sequence (IS_EOS), and values used for the addition (PRE_SUM, PRE_CARRY, PRE_EOS, SUM, and POS_1, POS_2). The columns represent the tokens in the input sequence, showing how they are initially encoded in different dimensions. Note the position IDs (POS_1, POS_2) which play a crucial role in the attention mechanism.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix X(0) for the input sequence “$653 + 049 = 2070”. The matrix is d x N where d is the embedding dimension and N is the sequence length. Each column represents a token’s embedding, and each row represents a specific dimension (e.g., NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES, PRE_SUM, etc.). The table shows the values for the first few dimensions; the grayed-out rows are for later calculations within the model.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix X(0) used in the formal construction of the addition Transformer with position coupling. The table illustrates how each token in the input sequence (’$653+049=2070’) is represented by a vector of 17 dimensions (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES, PRE_SUM, PRE_CARRY, PRE_EOS, SUM, IS_EOS, POS_1, POS_2). The gray rows represent the position embedding that will be filled in later during the construction.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding used in the formal construction of the addition Transformer with position coupling. It illustrates how token embeddings and position embeddings are combined to create the input encoding matrix X(0). The table includes columns for each token in the input sequence (’$’, ‘6’, ‘5’, ‘3’, ‘+’, ‘0’, ‘4’, ‘9’, ‘=’, ‘2’, ‘0’, ‘7’, ‘0’) and rows for different dimensions of the embedding (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES, PRE_SUM, PRE_CARRY, PRE_EOS, SUM, IS_EOS, POS_1, POS_2). The gray rows represent dimensions that will be filled later in the process.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

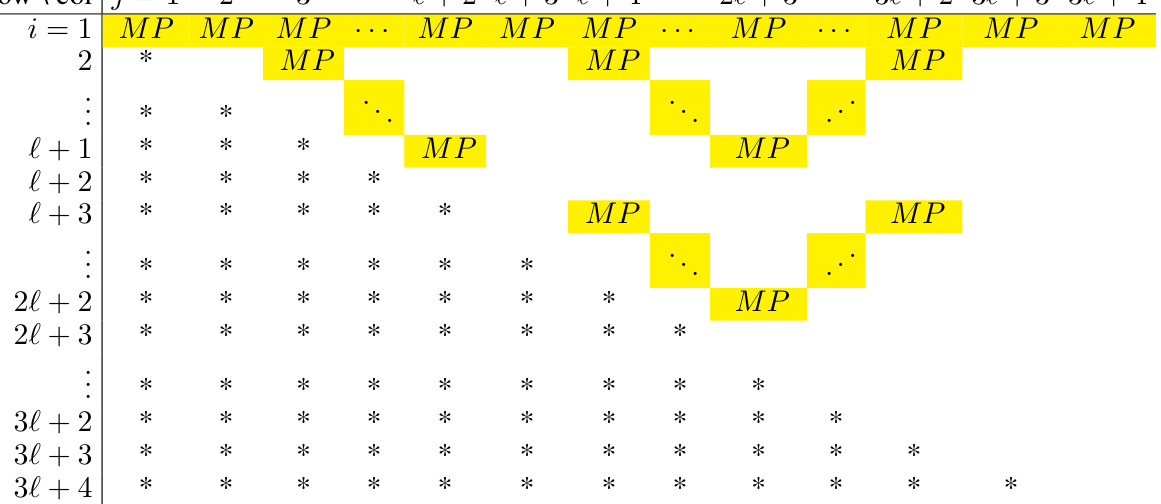

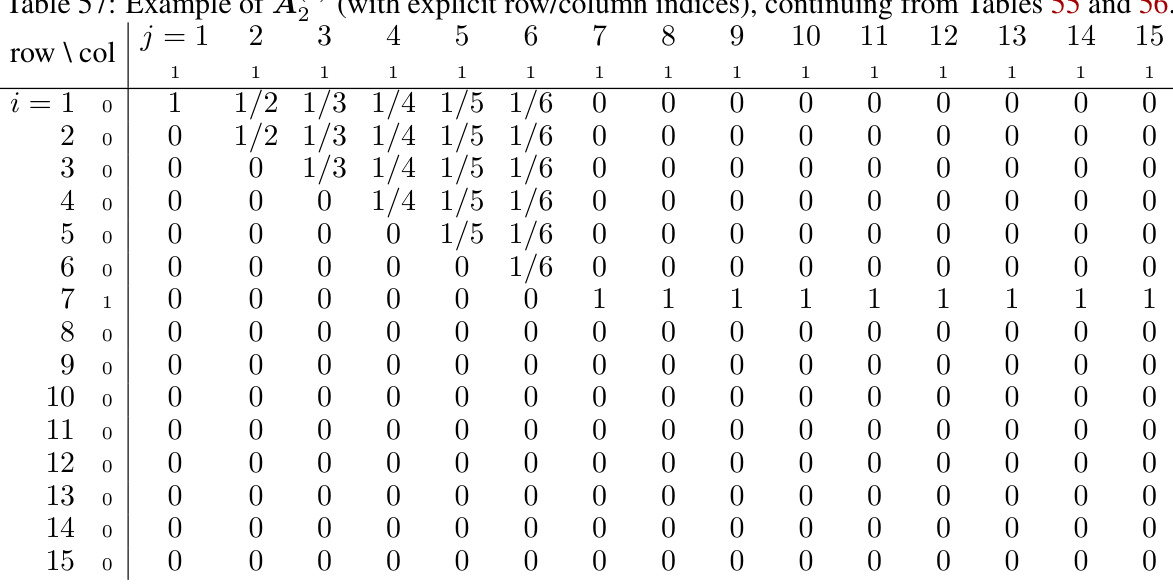

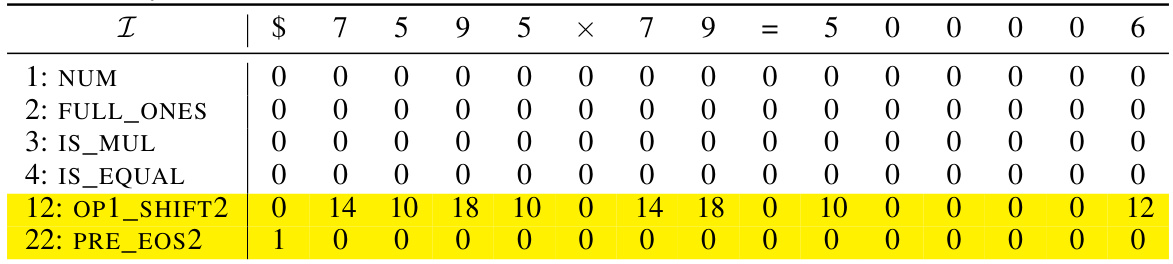

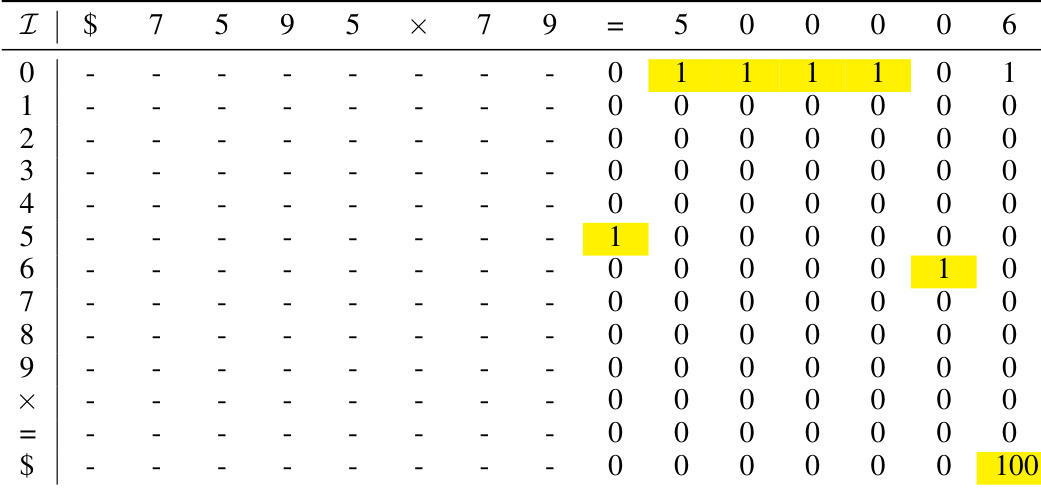

🔼 This table shows the attention score matrix C₁ for Head 1 of the 1-layer Transformer with position coupling. It demonstrates the attention weights between different tokens for decimal integer addition. The matrix is represented with explicit row and column indices, highlighting the positions of large attention weights (MP) that determine which tokens the network attends to during addition. Some entries are marked with an asterisk (*) to indicate elements that are ignored by the causal softmax operation, and dots (…) to indicate the hidden MP entries.

read the caption

Table 10: Exact attention score matrix C₁ (with explicit row/column indices) of Head 1.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix used in the formal construction of the addition transformer with position coupling. The input sequence is represented as a collection of tokens, each with a unique positional ID determined by the position coupling method. The table shows the token embeddings (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES), the coupled position IDs, and the initial values for dimensions related to the sum (SUM), carry (PRE_CARRY), and EOS (PRE_EOS) tokens. Gray rows represent dimensions that will be filled later in the process.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix used in the formal construction of the addition transformer with position coupling. It illustrates the different dimensions (features) of the encoding, including numerical values, positional information, and special tokens. The table uses the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070$’ as an example and a starting position ID of ‘2’. Some dimensions (‘gray rows’) are left unfilled initially, indicating they are updated in later steps of the encoding process.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vk are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix for the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’ in the addition task. It illustrates how the different dimensions represent various aspects of the input tokens (numbers, special tokens, position information). The ‘gray rows’ indicate dimensions that will be filled in later stages of processing within the transformer model.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows the attention score matrix C₁ for Head 1 in the addition task. The rows and columns represent the input tokens, and each cell’s value represents the attention weight between the corresponding tokens. Note that the matrix is upper triangular due to the causal attention mechanism. The ‘MP’ values indicate attention weights that are significantly larger than other entries, indicating a strong attention connection between the corresponding tokens. The ‘*’ symbols represent entries that are masked (ignored) by the causal mask, and ‘.’ represents entries with less significant values.

read the caption

Table 10: Exact attention score matrix C₁ (with explicit row/column indices) of Head 1.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix X(0) which is created by concatenating token embeddings and position embeddings. It consists of 17 dimensions for tokens and 2P dimensions for positions where P is a hyperparameter. The table shows how the first few rows (dimensions) of the encoding matrix are filled for the input sequence. The gray rows represent dimensions that will be filled later in the process.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix used in the formal construction of the addition transformer with position coupling. It demonstrates how the input sequence is encoded using token embeddings (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES) and position embeddings (POS_1, POS_2). The table includes dimensions for numbers (NUM), beginning of sequence (IS_BOS), and full ones (FULL_ONES), along with dimensions for pre-sum, pre-carry, pre-EOS, the sum itself, and IS_EOS. Gray rows represent dimensions which are filled in during later steps of the process.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding of the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’ for the addition task. The encoding includes token embeddings (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES) and position embeddings (POS_1, POS_2). The table highlights how each token is represented in the different dimensions of the encoding. The ‘gray’ rows represent dimensions that are filled in later stages of the Transformer processing. The starting position ID is set to 2.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding in the addition task. The input sequence is represented as a collection of sequences of the form ‘(query)=(response)’. Each row shows a particular named dimension of the encoding matrix, and each column represents an embedding vector for a token. The table also shows the starting position ID and how the position IDs are assigned to tokens. The gray rows are the part of embedding that will be filled in later steps.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix for the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’ used in the formal construction of the addition transformer with position coupling. The matrix has rows representing different dimensions (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES, PRE_SUM, PRE_CARRY, PRE_EOS, SUM, IS_EOS, POS_1, POS_2), and columns representing input tokens. The table demonstrates how the token embeddings and positional encodings are combined for each token, with some values left as ‘0’ to be filled in later steps.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding for the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’ with a starting position ID of 2. It illustrates how the token embeddings and position embeddings are combined to form the input encoding matrix X(0). The table is divided into sections representing various aspects of the input tokens and their positions, including numbers, special tokens, and position IDs. Some rows are initially filled with zeros and will be populated in later stages of the process.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix for the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’. The encoding matrix is composed of token embeddings and position embeddings. The table illustrates the values assigned to different dimensions (rows) for each token (column). The ‘gray’ rows represent dimensions that will be filled in by later layers of the Transformer.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding process for the input sequence representing the addition problem ‘653 + 49 = 2070’. The initial encoding is a matrix where each column corresponds to a token in the sequence, and each row represents a specific dimension or feature. The table illustrates the values in several key dimensions, such as the numerical value of the digits (NUM), the beginning-of-sequence indicator (IS_BOS), and a vector of ones (FULL_ONES). Other dimensions, shown as grayed-out, represent features such as preliminary sums (PRE_SUM), carries (PRE_CARRY), and the end-of-sequence indicator (PRE_EOS), which are computed in later steps of the process, making the table an intermediate step in the encoding process described in the paper.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

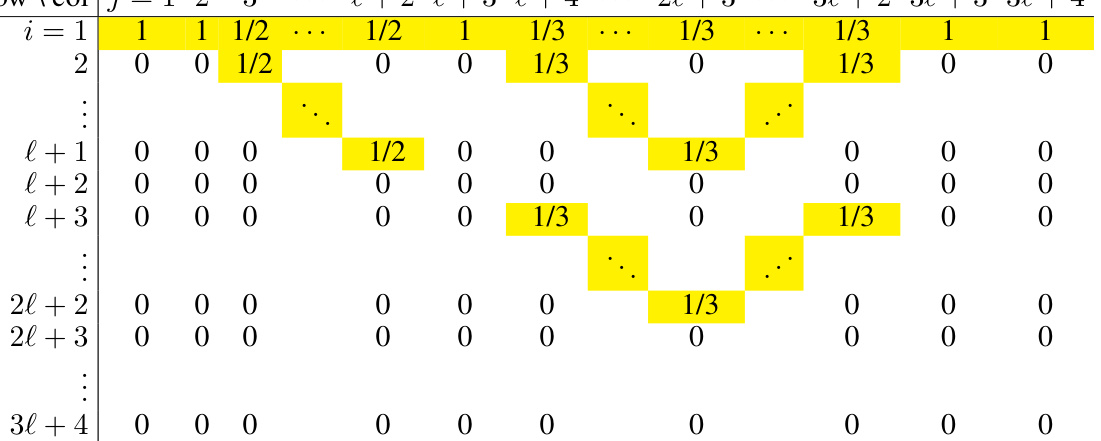

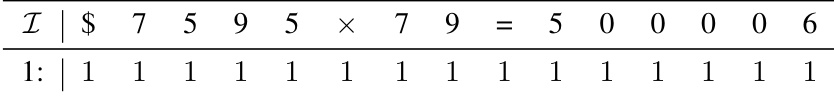

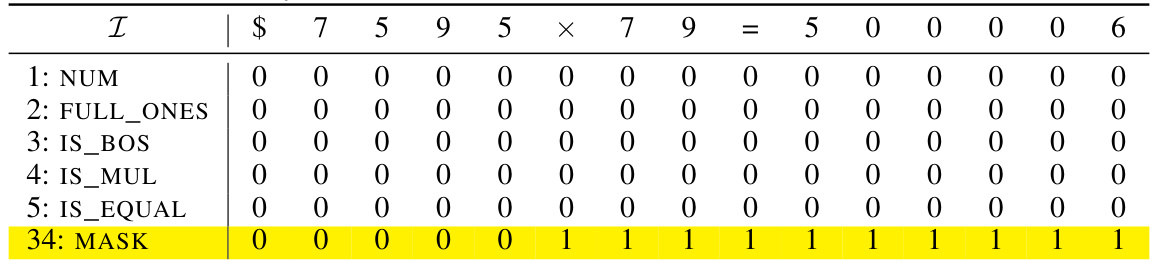

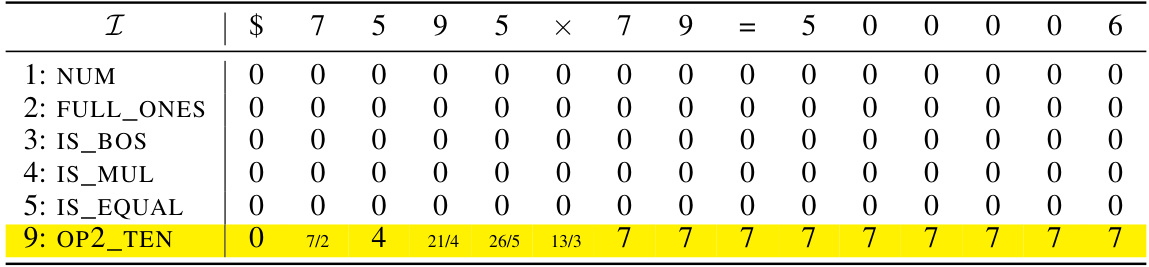

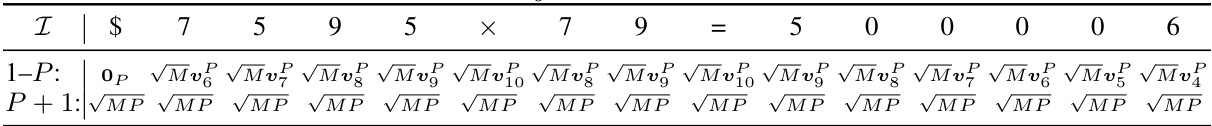

🔼 This table shows the attention matrix A(¹) obtained from the softmax operation on the attention score matrix C(¹) for Attention Head 1. The matrix A(¹) is a column-stochastic matrix with entries representing the attention weights between different query and key vectors. The values shown illustrate a simplified version for a sufficiently large M, where only the most significant attention weights are shown, represented as 1 or fractions. Zeros indicate negligible attention weights. The table illustrates the pattern of attention distribution crucial for detecting the ones digit of the second operand.

read the caption

Table 34: Example of A(¹) (with explicit row/column indices and sufficiently large M), continuing from Tables 32 and 33.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix X(0) used in the formal construction of the addition transformer with position coupling. It illustrates how token embeddings and position embeddings are combined. The table highlights various dimensions representing different aspects of the input tokens: NUM (number), IS_BOS (beginning of sequence), FULL_ONES (all ones), PRE_SUM (pre-sum), PRE_CARRY (pre-carry), PRE_EOS (pre-end of sequence), SUM (sum), IS_EOS (end of sequence). The grayed-out rows represent dimensions for position embeddings that are filled in later steps.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding for the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’. The encoding is a matrix where each column represents a token in the sequence, and each row represents a specific dimension or feature. The first few rows (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES) are directly filled based on the tokens’ properties. The rows that start with ‘PRE’ represent values to be calculated in the attention and feed-forward layers (the gray rows). The rows starting with ‘POS’ represent the position embedding. The rows with ‘SUM’ are the one-hot representation of the digits in the output sum.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix X(0) for the input sequence “$653 + 049 = 2070”, with a starting position ID of 2. Each column represents a token, and each row represents a specific dimension (NUM, IS_BOS, FULL_ONES, etc.). The initial encoding is a combination of token embeddings and position embeddings. The ‘gray’ rows denote dimensions which are initialized to zero and will be filled by subsequent layers in the transformer.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

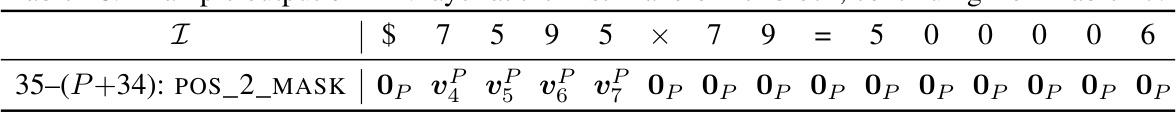

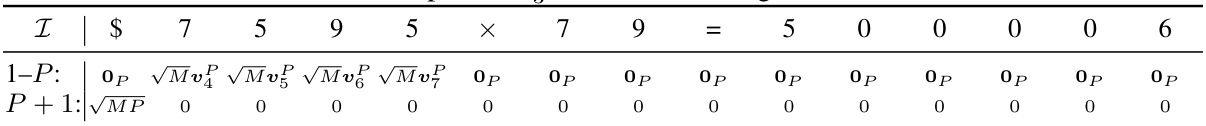

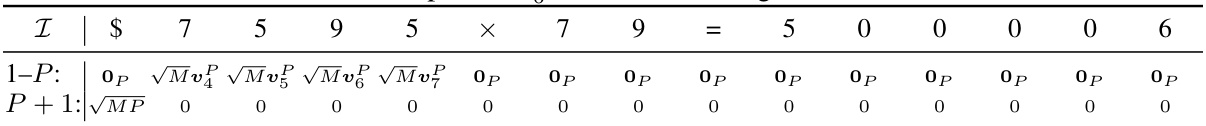

🔼 This table displays the attention matrix A(2) calculated from the query and key matrices Q(2) and K(2), as described in the paper. The values in the matrix represent the attention weights between different tokens in the input sequence. The table shows that the attention weights are non-zero only when the inner product between the query and key vectors equals to MP, where M is a sufficiently large real number. The table helps to understand how the attention mechanism works in this specific stage of the N x 2 multiplication task. The matrix A(2) is used to generate the input embedding for the subsequent layers.

read the caption

Table 57: Example of A(2) (with explicit row/column indices), continuing from Tables 55 and 56.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding matrix for the input sequence “$653 + 049 = 2070”. Each row represents a specific dimension in the embedding, such as NUM (the numerical value of the token), IS_BOS (indicates the beginning of sequence), FULL_ONES (always 1), PRE_SUM (preparation for sum), PRE_CARRY (preparation for carry), PRE_EOS (preparation for end of sequence), SUM (the digits in the sum), and IS_EOS (indicates the end of sequence). The table illustrates how the token and position embeddings are initially encoded before any transformation by the Transformer layers. The grey rows are left blank to be filled by the subsequent layers.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.

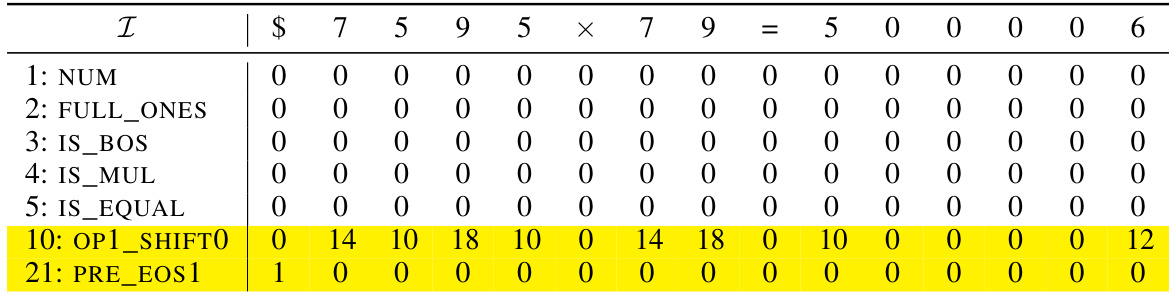

🔼 This table shows an example of the query matrix Q(1)X(0) in the first attention block for the N x 2 multiplication task. The matrix is constructed using the position embedding, and each row represents the query vector of a token in the sequence. Specifically, the first P rows are obtained by copying from the dimensions POS_2 and scaling by √M, while the last row is the copy of the dimension FULL_ONES scaled by √MP. The values in the table are illustrative examples, and the exact values would depend on the specific hyperparameters and random initialization.

read the caption

Table 37: Example of Q(1) X (0), continuing from Table 28.

🔼 This table shows an example of the initial encoding for the input sequence ‘$653 + 049 = 2070’, where the starting position ID is 2. The table demonstrates how the token embedding and position embedding are combined. The ‘NUM’, ‘IS_BOS’, and ‘FULL_ONES’ dimensions are explicitly shown, while the remaining dimensions (grayed out) will be filled in later stages of the model’s processing. This illustrates the input representation used in the theoretical analysis of the 1-layer transformer.

read the caption

Table 9: Example initial encoding. Here we consider the input sequence $653 + 049 = 2070 and the starting position ID is chosen as s = 2. The vectors vf are defined in Equation (11). The gray rows will be filled in later.