TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) heavily rely on imitation learning for training, primarily using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). However, MLE struggles with issues like compounding errors and limited generation diversity. This paper explores inverse reinforcement learning (IRL) as an alternative, extracting rewards and directly optimizing for sequences rather than individual tokens.

The study proposes a novel method, reformulating inverse soft-Q-learning as a temporal difference-regularized extension of MLE. This establishes a principled link between MLE and IRL, allowing a flexible trade-off between complexity and model performance. Experiments across various LLM models and benchmarks showcase the effectiveness of this IRL approach, demonstrating its ability to achieve better or comparable task performance while significantly improving the diversity of generations.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI and NLP because it introduces a novel approach to imitation learning for large language models, overcoming limitations of traditional methods. It offers a more robust and efficient way to fine-tune LLMs, leading to better performance and diversity in text generation. This opens up new avenues for research in reward function design and model alignment, improving the overall capabilities of LLMs. The integration of IRL into the existing LLM workflow is a significant development.

Visual Insights#

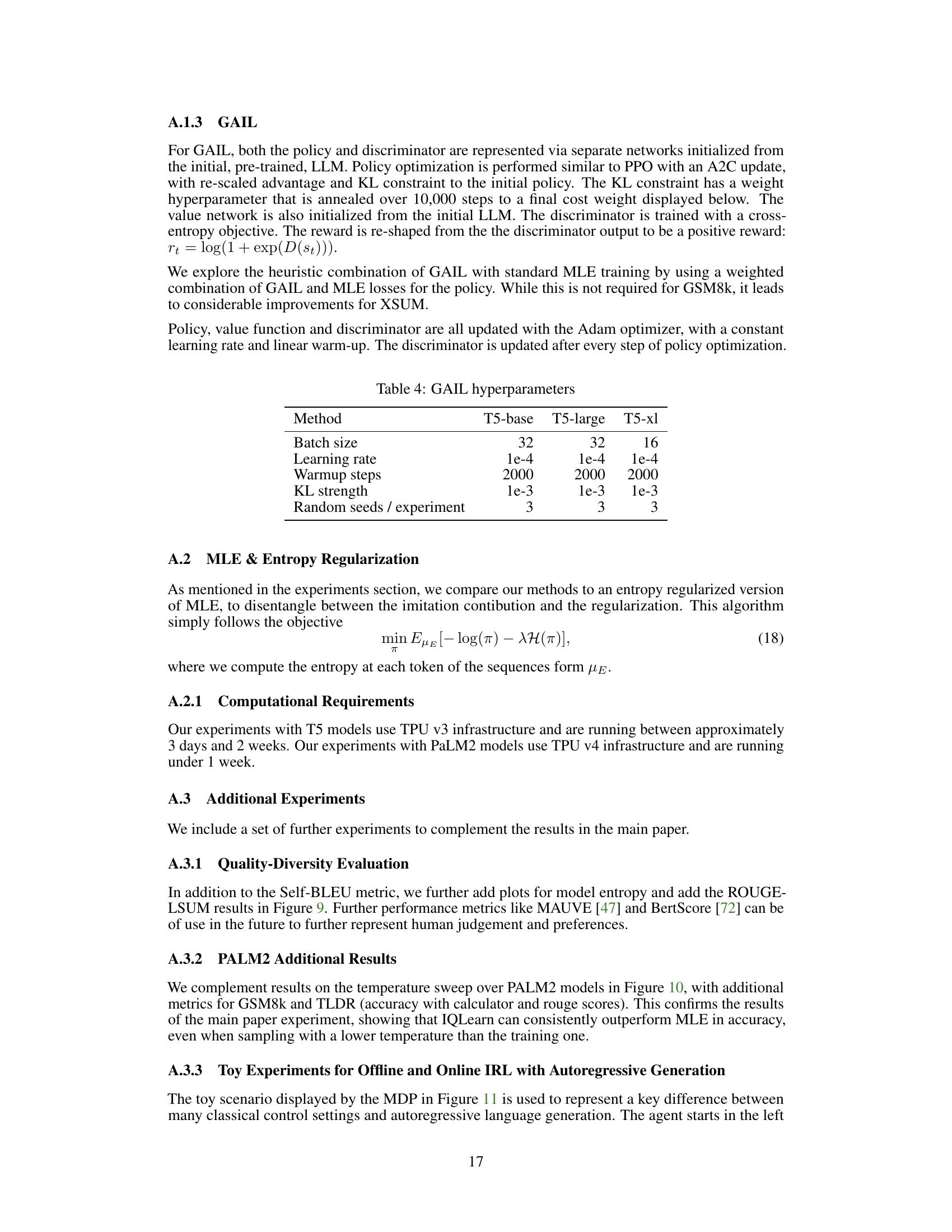

🔼 This figure illustrates the differences in data usage and optimization strategies between maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), offline inverse reinforcement learning (IRL), and online IRL for language model training. MLE focuses solely on matching the next token in a sequence, while IRL methods consider the impact of current predictions on future tokens. Offline IRL uses existing training data, whereas online IRL incorporates past model generations into the optimization process.

read the caption

Figure 1: Data usage and optimization flow in MLE, offline and online IRL. Independent of the method, current models use the history of past tokens to predict the next. However, MLE purely optimizes the current output for exact matching the corresponding datapoint while IRL-based methods take into account the impact on future tokens. Online optimization additionally conditions on past model generations rather than the original dataset. Grey and blue objects respectively represent training data and model generations. The impact of future datapoints is often indirect and mediated via learned functions (e.g. the discriminator in GAIL [25] and the Q-function in IQLearn [20]).

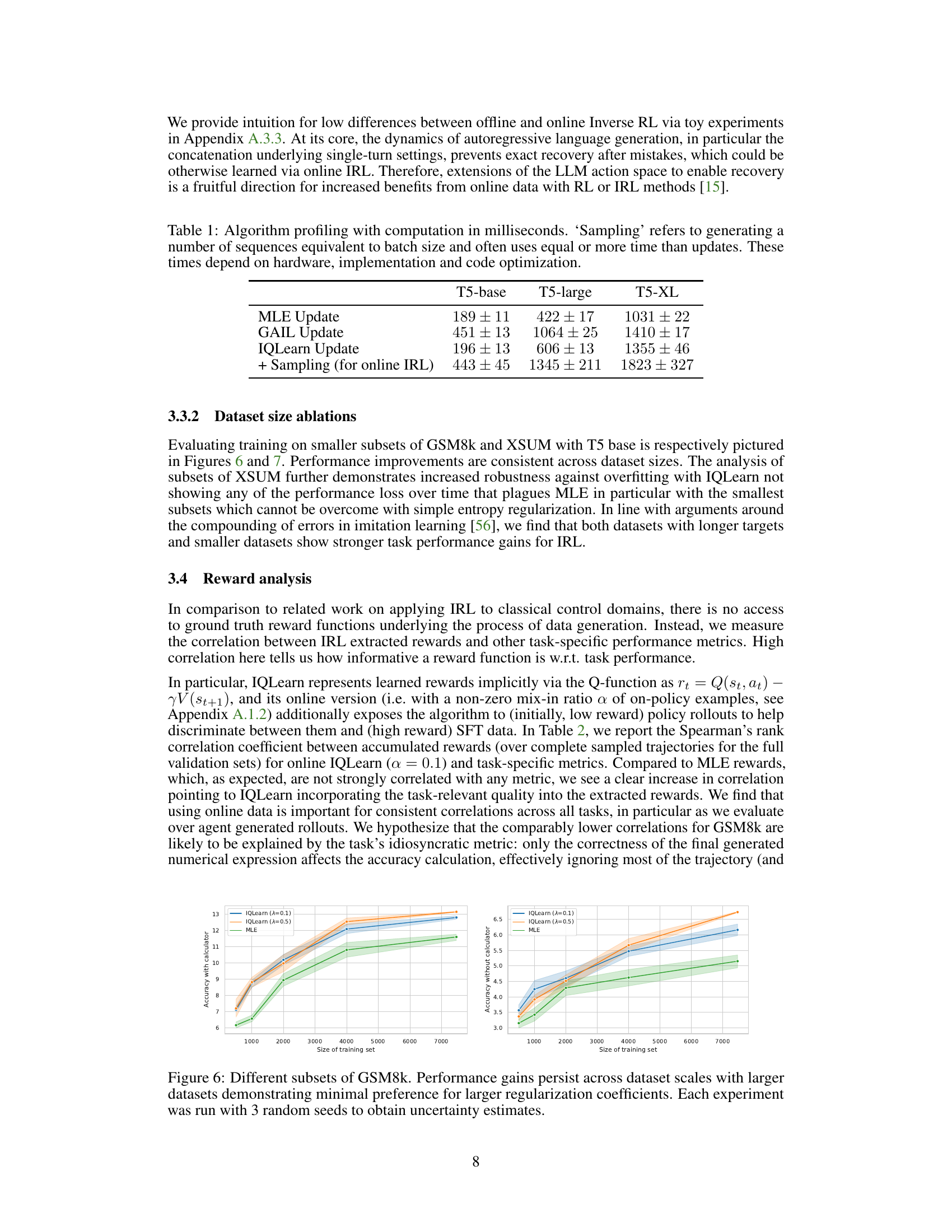

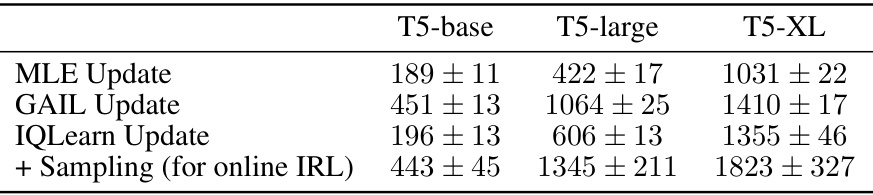

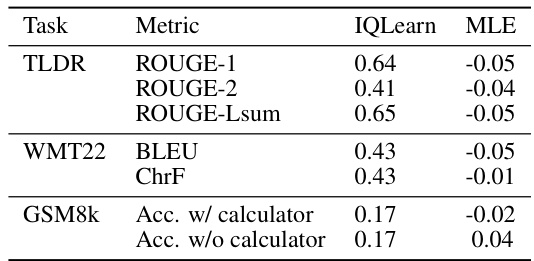

🔼 This table compares the computational cost of different algorithms for training language models, measured in milliseconds. It shows the time taken for model updates (MLE, GAIL, IQLearn) and the additional time required for sampling (which applies to online IRL). The results are shown for three different sizes of T5 models (base, large, and XL).

read the caption

Table 1: Algorithm profiling with computation in milliseconds. 'Sampling' refers to generating a number of sequences equivalent to batch size and often uses equal or more time than updates. These times depend on hardware, implementation and code optimization.

In-depth insights#

IRL for LLMs#

This research explores the application of Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) to Large Language Models (LLMs). IRL offers a powerful alternative to traditional maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) for LLM fine-tuning, addressing MLE’s limitations in handling sequential data and promoting diversity in generated outputs. By extracting reward functions from data, IRL directly optimizes entire sequences, rather than individual tokens, leading to improved task performance and greater diversity in generated text. The study provides a novel reformulation of inverse soft-Q-learning, bridging MLE and IRL, enabling a principled trade-off between complexity and performance. Offline IRL is highlighted as a particularly scalable and effective approach, offering clear advantages even without online data generation. Analysis of the extracted reward functions suggests potential improvements in reward design for subsequent reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) stages. The work demonstrates substantial gains in both performance and diversity, particularly for challenging tasks, presenting a compelling case for the broader adoption of IRL in future LLM development.

MLE-IRL Bridge#

The concept of an ‘MLE-IRL Bridge’ in the context of large language model (LLM) training is a fascinating one. It speaks to the core tension between the efficiency of maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) and the potential of inverse reinforcement learning (IRL) for aligning model behavior with human preferences. MLE, while computationally straightforward and scalable, often suffers from limitations such as mode collapse and a lack of inherent reward awareness. IRL, on the other hand, can explicitly incorporate reward signals, leading to potentially more robust and aligned models, but at the cost of significantly increased complexity and computational demand. A bridge between these two approaches would ideally leverage the scalability of MLE while harnessing the alignment capabilities of IRL. This could involve techniques that incorporate reward-related information into the MLE framework, perhaps by modifying the loss function to reflect reward preferences or by using IRL to pre-train or guide the reward function used in subsequent RLHF phases. Ultimately, a successful ‘MLE-IRL Bridge’ might represent a crucial step towards more efficient and effective training procedures for highly capable, yet safely aligned LLMs. Such a bridge would be particularly beneficial in balancing task performance with the generation diversity, an area where MLE often falls short.

Offline IRL Gains#

Offline Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) presents a compelling approach to enhance large language model (LLM) training. Offline IRL methods leverage existing datasets, eliminating the need for costly and time-consuming online data generation. This is a significant advantage over online IRL approaches, which often involve iterative model application and feedback loops. The core idea is to extract reward functions directly from the data and optimize model behavior to maximize rewards, instead of solely focusing on next-token prediction as in maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). This allows for improved alignment with human preferences and generates more diverse and robust outputs. While offline IRL might not always surpass MLE in terms of raw performance metrics, the trade-off is often worthwhile, as the increase in diversity and robustness can be crucial for real-world applications. The potential of offline IRL for LLM training is notable and warrants further investigation. A principled connection between MLE and IRL is established, allowing for a smooth transition between these two approaches and making offline IRL a practical alternative to traditional MLE-based training methods. The scalability of offline IRL is particularly attractive, making it more applicable to extremely large language models.

Reward Analysis#

The reward analysis section is crucial because it evaluates the quality of rewards learned by Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) methods. Unlike traditional RL where rewards are explicitly defined, IRL methods must infer them. The correlation between learned rewards and task performance metrics serves as a key indicator of the learned reward’s quality. High correlation implies that the learned rewards effectively capture the underlying task objective. The analysis also compares these correlations with those obtained from Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) as a baseline. A significant difference would highlight the advantage of the IRL method’s learned reward function over a simpler MLE approach. Analyzing the impact of online vs. offline data on reward quality provides valuable insights into the data efficiency and scalability of these methods. The reward analysis also examines the role of online data generation in improving reward quality, which is crucial for understanding the tradeoffs between computational cost and reward information richness. Finally, investigating the relationship between the reward and performance metrics across different model sizes and tasks would offer broader insights into the effectiveness and generalizability of the IRL approach.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the LLM action space to enable recovery from errors during generation is crucial, potentially improving performance gains from online IRL. A more in-depth investigation into diversity metrics beyond Self-BLEU is needed to fully understand the impact on downstream tasks like RLHF. Analyzing the interplay between IRL and the specific characteristics of different language models (LLMs) and datasets is critical; exploring how data properties, such as length or complexity, affect the performance gains of IRL versus MLE is a key area for future study. Furthermore, investigating the application of IRL to the pretraining phase of LLMs warrants exploration, potentially leveraging computational efficiency gains. Finally, a deeper understanding of the rewards learned via IRL and their connection to downstream task performance would enable the development of more effective and interpretable reward functions for RLHF, leading to improved alignment and robustness in LLM applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows the results of fine-tuning experiments on the GSM8k dataset using three different methods: Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), Inverse Q-Learning (IQLearn), and Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL). The x-axis represents accuracy (with and without a calculator), and the y-axis represents the diversity of model generations (measured by Self-BLEU). Different regularization strengths were applied to each method. The results indicate that MLE’s performance significantly decreases with higher entropy cost, while IQLearn and GAIL offer a better trade-off between performance and diversity. Larger models perform better but also exhibit higher self-similarity, highlighting the value of balancing performance and diversity.

read the caption

Figure 2: GSM8k results for fine-tuning with MLE, IQLearn, and GAIL across different regularization strengths. In particular MLE shows strong performance reduction with higher entropy cost. Larger models demonstrate higher performance but also stronger self similarity across generations, rendering effective trading of between task performance and diversity highly relevant. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean after repeating the experiment with 3 different seeds.

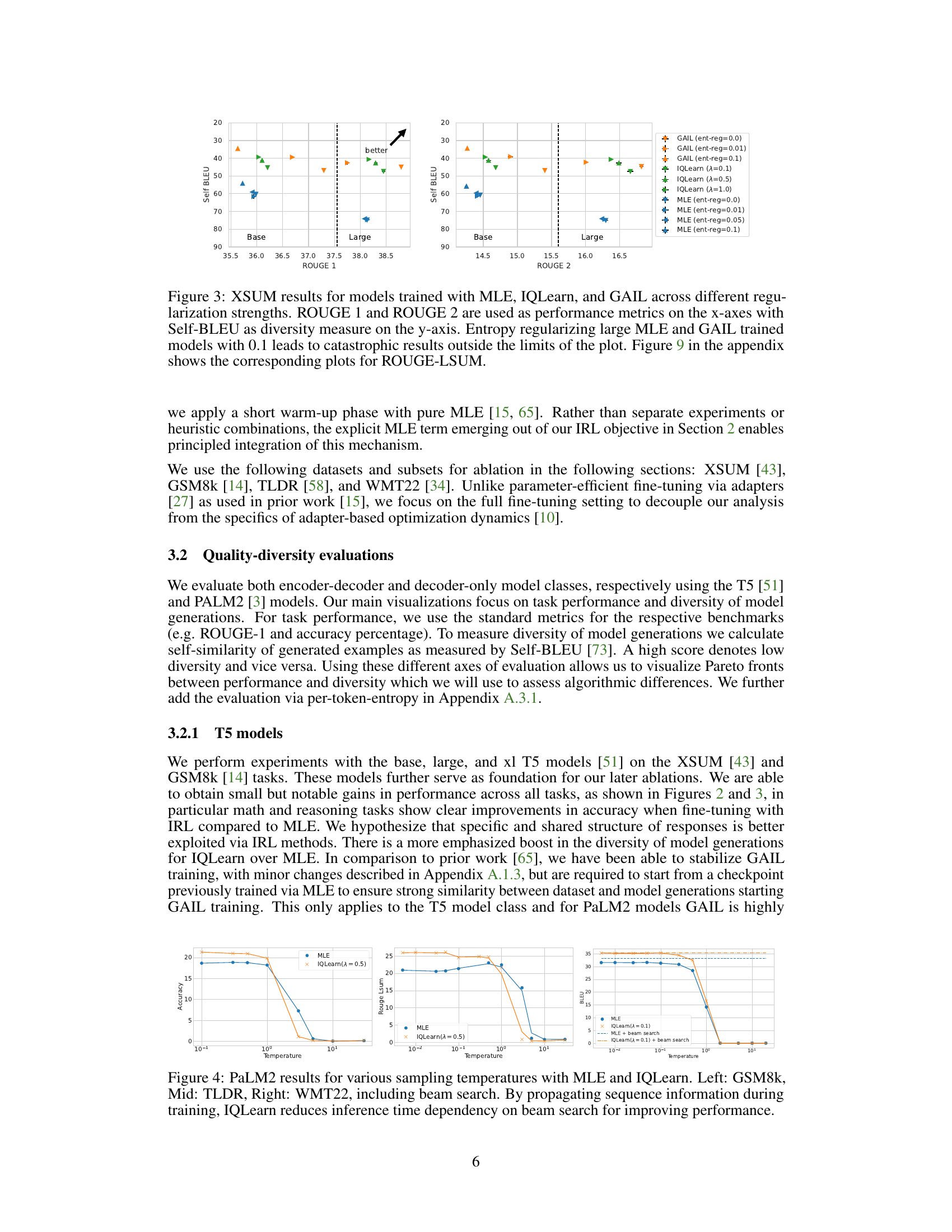

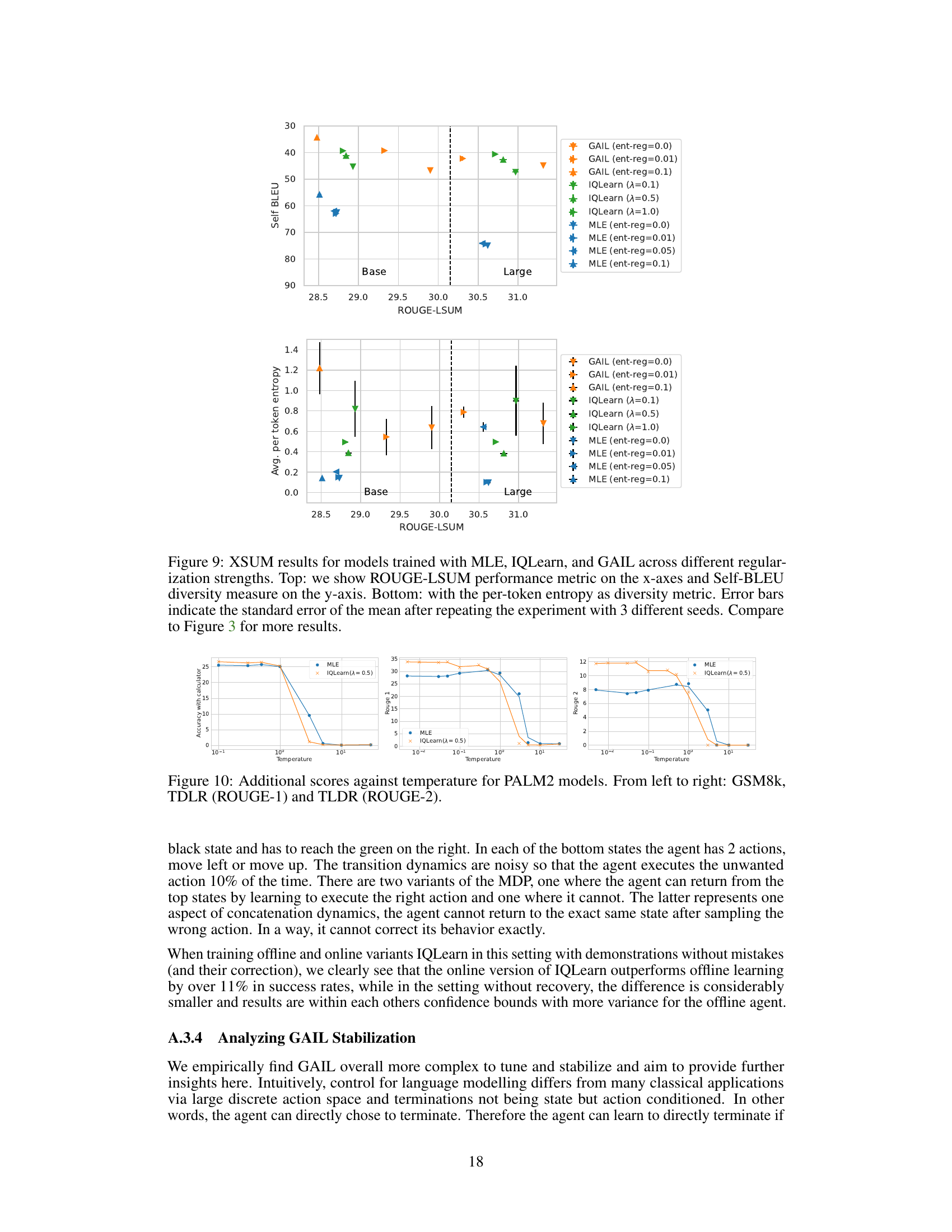

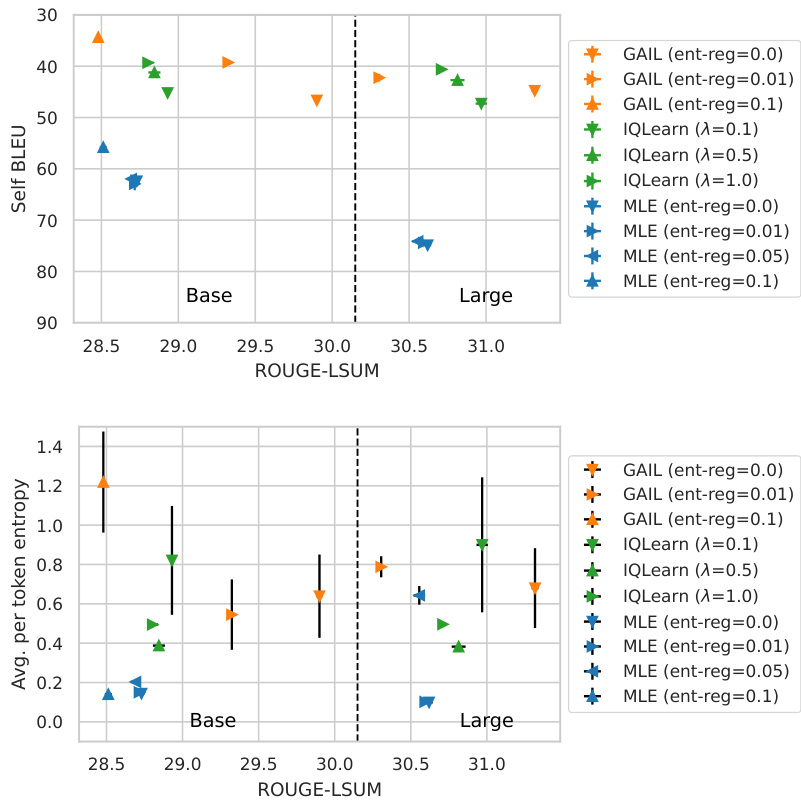

🔼 This figure displays the results of experiments on the XSUM dataset using different training methods: Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), Inverse Q-Learning (IQLearn), and Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL). The x-axis represents ROUGE-1 and ROUGE-2 scores (metrics for evaluating summarization quality), while the y-axis shows Self-BLEU scores (a measure of the diversity of generated summaries). Different regularization strengths were used for each method. The figure shows that IQLearn achieves a good balance between high ROUGE scores (good quality) and high Self-BLEU scores (diverse summaries). In contrast, MLE with high entropy regularization performs poorly. The appendix contains similar plots using ROUGE-LSUM.

read the caption

Figure 3: XSUM results for models trained with MLE, IQLearn, and GAIL across different regularization strengths. ROUGE 1 and ROUGE 2 are used as performance metrics on the x-axes with Self-BLEU as diversity measure on the y-axis. Entropy regularizing large MLE and GAIL trained models with 0.1 leads to catastrophic results outside the limits of the plot. Figure 9 in the appendix shows the corresponding plots for ROUGE-LSUM.

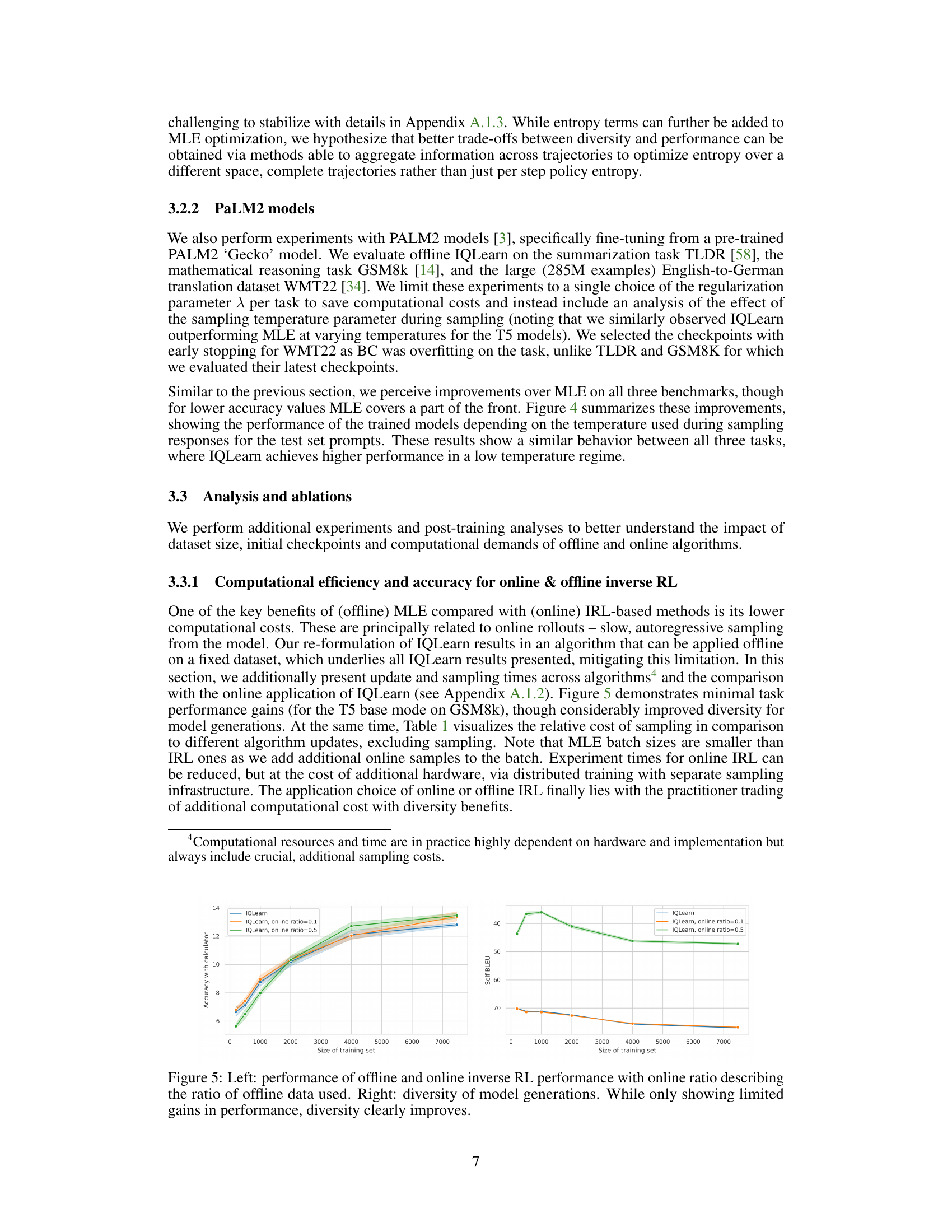

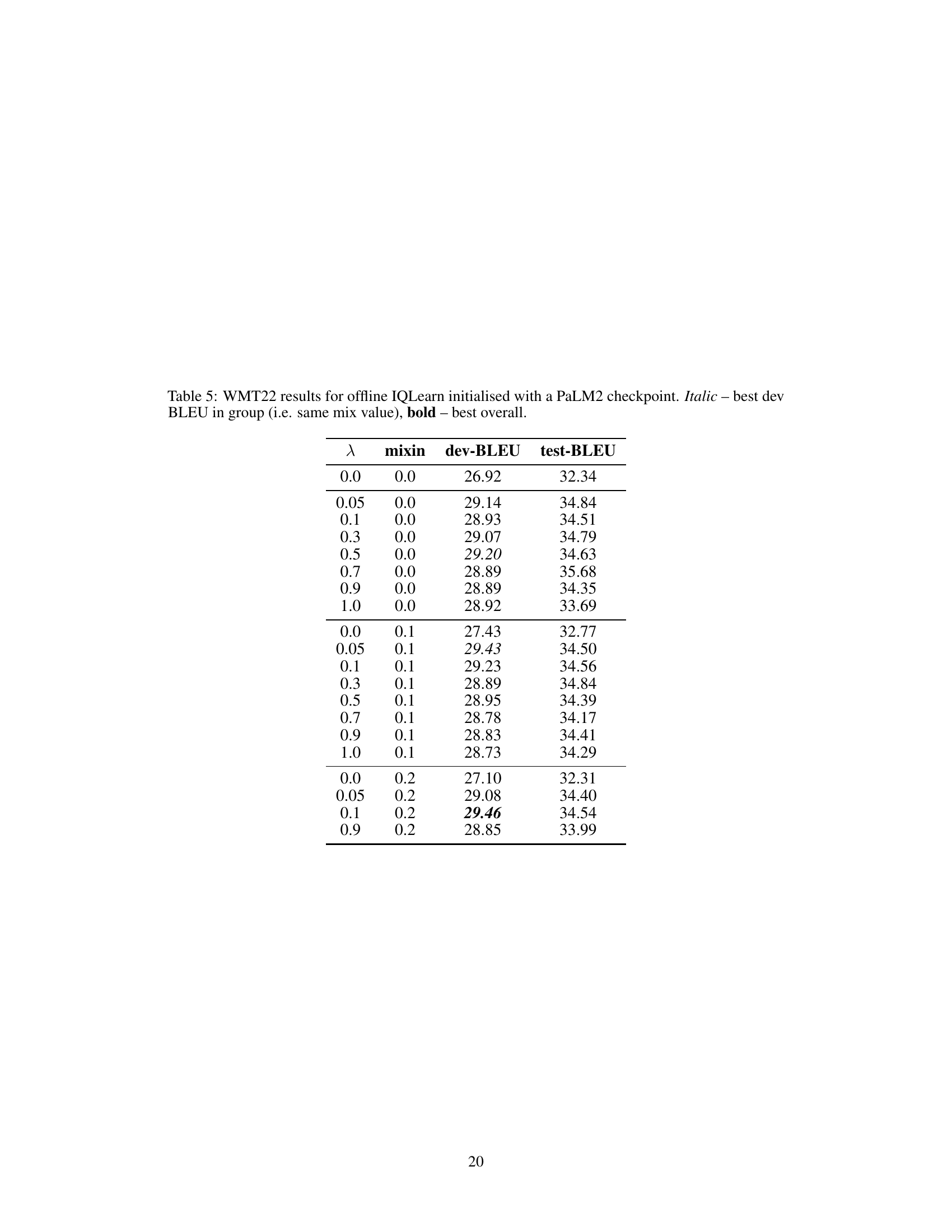

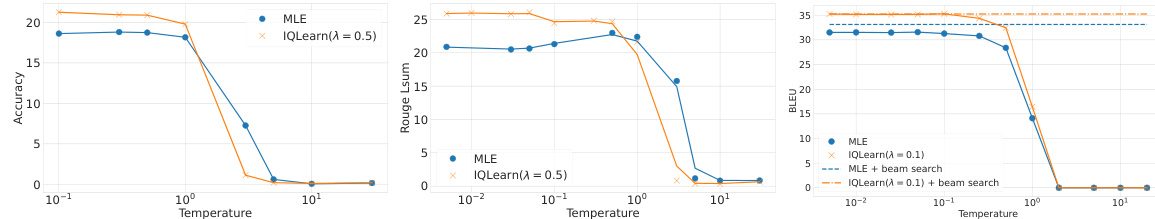

🔼 This figure displays the results of experiments using PaLM2 models on three different tasks (GSM8k, TLDR, and WMT22) with two different training methods (MLE and IQLearn) and with varying sampling temperatures. The left panel shows results for the GSM8k task, the middle for TLDR, and the right for WMT22. Each panel presents three lines representing MLE performance without beam search, IQLearn performance without beam search, and MLE performance with beam search, IQLearn performance with beam search. The x-axis represents the sampling temperature, and the y-axis represents the performance metric (accuracy, ROUGE-LSUM, or BLEU, respectively). The caption highlights that IQLearn’s performance is less dependent on beam search, indicating that IQLearn better propagates sequence information during training, leading to improved inference efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 4: PaLM2 results for various sampling temperatures with MLE and IQLearn. Left: GSM8k, Mid: TLDR, Right: WMT22, including beam search. By propagating sequence information during training, IQLearn reduces inference time dependency on beam search for improving performance.

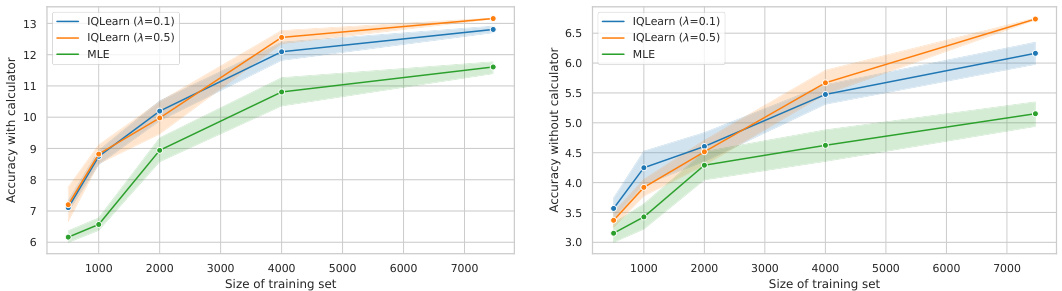

🔼 The figure shows the results of GSM8k experiments using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), Inverse Q-learning (IQLearn), and Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL) methods with varying regularization strength. It compares the accuracy (with and without a calculator) for different model sizes (Base, Large, X-Large). The results highlight a tradeoff between performance and diversity: higher regularization hurts MLE performance, while larger models perform better but exhibit less diversity.

read the caption

Figure 2: GSM8k results for fine-tuning with MLE, IQLearn, and GAIL across different regularization strengths. In particular MLE shows strong performance reduction with higher entropy cost. Larger models demonstrate higher performance but also stronger self similarity across generations, rendering effective trading of between task performance and diversity highly relevant. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean after repeating the experiment with 3 different seeds.

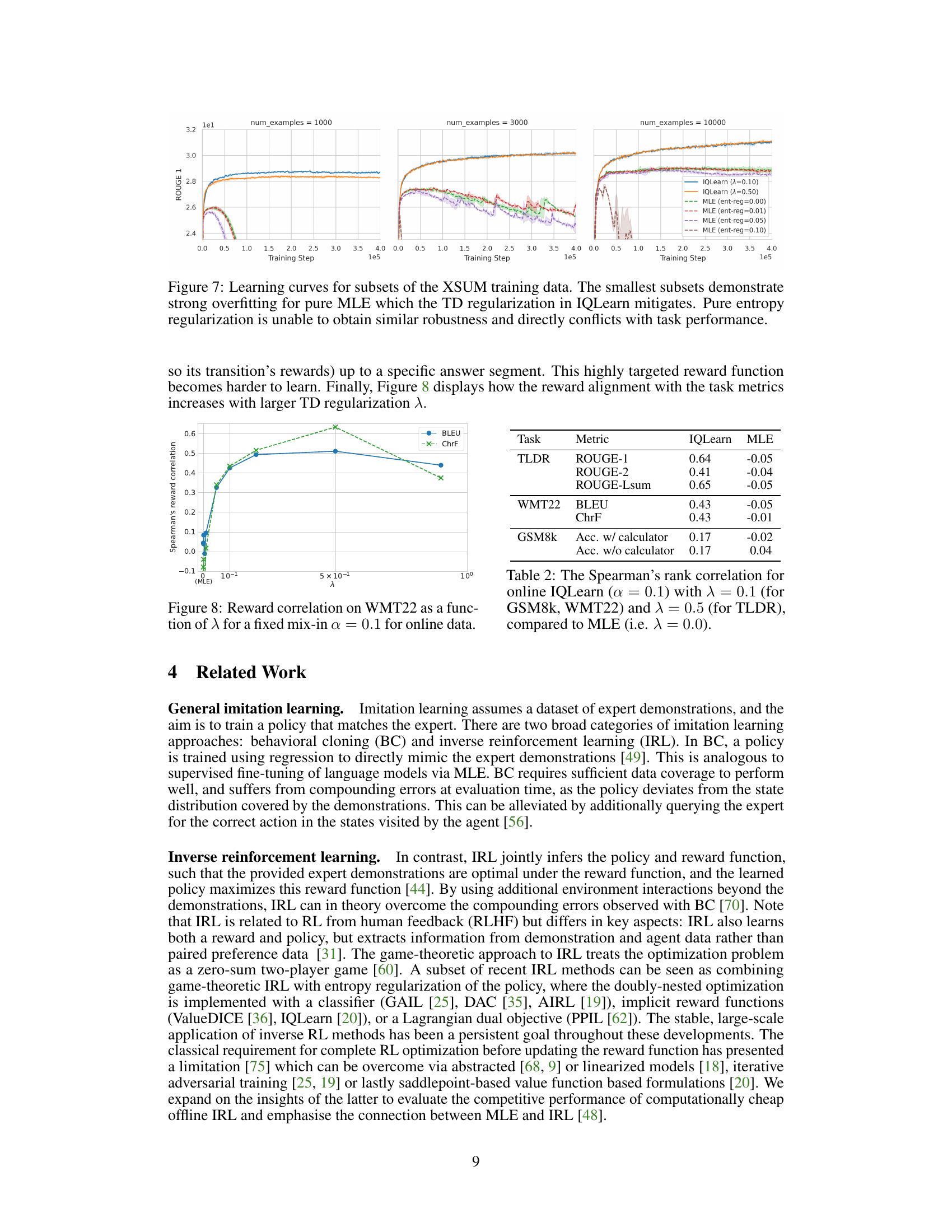

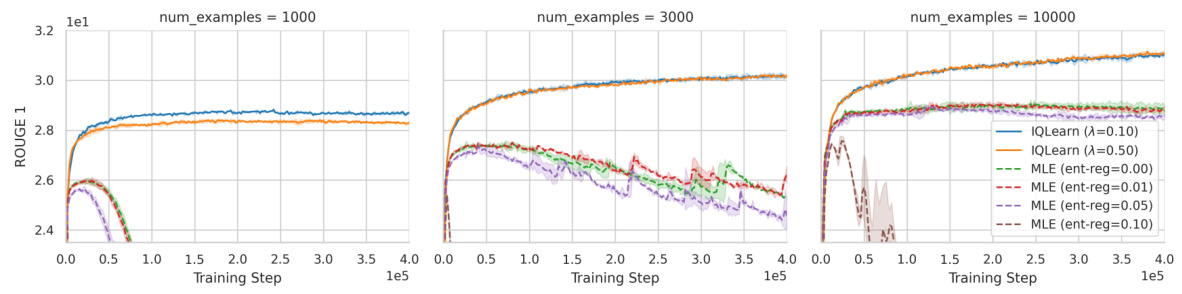

🔼 This figure shows the learning curves for different model training scenarios on the XSUM dataset, highlighting the impact of dataset size and regularization techniques. It demonstrates that using smaller datasets exacerbates the overfitting problem in Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)-based training. In contrast, Inverse Q-Learning (IQLearn) effectively mitigates this overfitting through its temporal difference regularization, improving model robustness. The figure also points out that simply applying entropy regularization to MLE is insufficient for addressing the overfitting issue.

read the caption

Figure 7: Learning curves for subsets of the XSUM training data. The smallest subsets demonstrate strong overfitting for pure MLE which the TD regularization in IQLearn mitigates. Pure entropy regularization is unable to obtain similar robustness and directly conflicts with task performance.

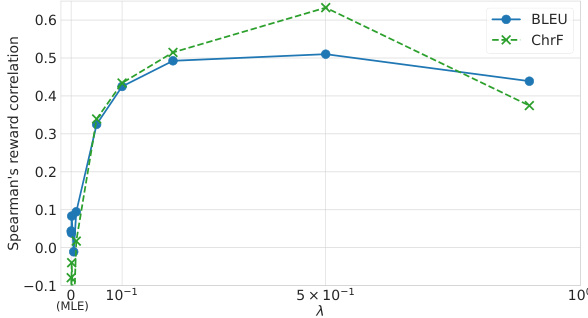

🔼 This figure shows the Spearman’s rank correlation between the accumulated rewards (over complete sampled trajectories for the full validation sets) for online IQLearn (α = 0.1) and task-specific metrics (BLEU and ChrF). It compares the correlations obtained with different values of the regularization parameter λ in IQLearn to the correlation obtained with MLE (λ = 0.0). The plot shows how the correlation between the learned rewards and task performance increases with λ, indicating that IQLearn effectively incorporates task-relevant information into the extracted rewards.

read the caption

Figure 8: Reward correlation on WMT22 as a function of λ for a fixed mix-in α = 0.1 for online data compared to MLE (i.e., λ = 0.0).

🔼 The figure shows the results of experiments on the GSM8k dataset using three different methods for fine-tuning large language models: Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), Inverse Soft Q-learning (IQLearn), and Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL). Different regularization strengths are tested for each method. The results highlight the trade-off between task performance and the diversity of model generations, particularly with larger models. The error bars show the standard error of the mean across multiple runs with different random seeds.

read the caption

Figure 2: GSM8k results for fine-tuning with MLE, IQLearn, and GAIL across different regularization strengths. In particular MLE shows strong performance reduction with higher entropy cost. Larger models demonstrate higher performance but also stronger self similarity across generations, rendering effective trading of between task performance and diversity highly relevant. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean after repeating the experiment with 3 different seeds.

🔼 This figure displays the performance of different models (MLE, IQLearn, and GAIL) on the XSUM dataset with various regularization strengths. ROUGE-1 and ROUGE-2 scores (measuring summarization quality) are plotted against Self-BLEU (measuring the diversity of generated summaries). The results show that IQLearn achieves a good balance between high ROUGE scores and high diversity. MLE and GAIL, especially with high entropy regularization, struggle to maintain good performance while also increasing diversity. The appendix contains similar plots using ROUGE-LSUM.

read the caption

Figure 3: XSUM results for models trained with MLE, IQLearn, and GAIL across different regularization strengths. ROUGE 1 and ROUGE 2 are used as performance metrics on the x-axes with Self-BLEU as diversity measure on the y-axis. Entropy regularizing large MLE and GAIL trained models with 0.1 leads to catastrophic results outside the limits of the plot. Figure 9 in the appendix shows the corresponding plots for ROUGE-LSUM.

🔼 This figure presents the results of the GSM8k experiment, comparing the performance of three different methods: Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), Inverse Q-Learning (IQLearn), and Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL). The x-axis represents the model size (Base, Large, X-Large), and the y-axis shows the accuracy. The results show that IRL-based methods (IQLearn and GAIL) exhibit better performance than MLE. Moreover, the impact of the regularization strength on the performance is also visible. The error bars illustrate the standard error of the mean, calculated from multiple experiment runs.

read the caption

Figure 2: GSM8k results for fine-tuning with MLE, IQLearn, and GAIL across different regularization strengths. In particular MLE shows strong performance reduction with higher entropy cost. Larger models demonstrate higher performance but also stronger self similarity across generations, rendering effective trading of between task performance and diversity highly relevant. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean after repeating the experiment with 3 different seeds.

🔼 This figure compares the data usage and optimization methods in Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE), offline Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL), and online IRL. It shows how MLE only focuses on the current token prediction by maximizing likelihood, while IRL methods consider the impact of current actions on future tokens. Online IRL differs by conditioning on past model generations instead of the original dataset.

read the caption

Figure 1: Data usage and optimization flow in MLE, offline and online IRL. Independent of the method, current models use the history of past tokens to predict the next. However, MLE purely optimizes the current output for exact matching the corresponding datapoint while IRL-based methods take into account the impact on future tokens. Online optimization additionally conditions on past model generations rather than the original dataset. Grey and blue objects respectively represent training data and model generations. The impact of future datapoints is often indirect and mediated via learned functions (e.g. the discriminator in GAIL [25] and the Q-function in IQLearn [20]).

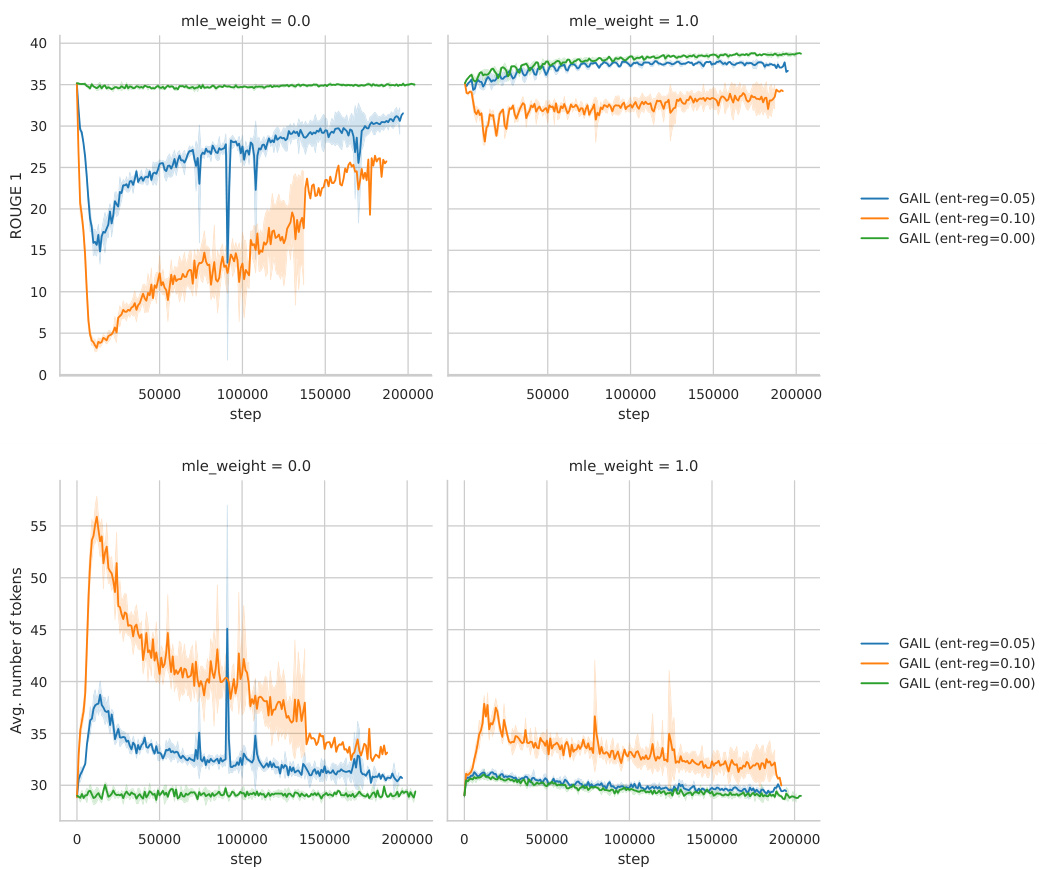

🔼 This figure shows the results of training a T5-Large model on the XSUM dataset using GAIL with different values of entropy regularization and MLE loss weight. The top graph shows ROUGE-1 scores, and the bottom shows the average number of tokens in the generated summaries. The results show that adding an MLE loss improves ROUGE-1 scores but increases the length of the generated summaries.

read the caption

Figure 12: Effect of adding a standard MLE loss (mle_weight=1) on the training data combined with GAIL on XSUM. We show the ROUGE 1 metric and the average length of the generated summaries when training a T5-Large model with GAIL.

More on tables

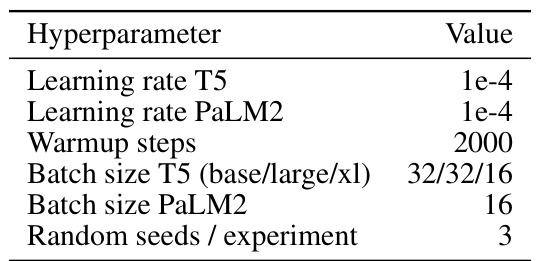

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameter settings used for both the IQLearn and MLE algorithms in the experiments described in the paper. It specifies the learning rate for both T5 and PaLM2 models, the number of warmup steps, the batch sizes used for different sizes of T5 models and the PaLM2 model, and the number of random seeds used per experiment.

read the caption

Table 3: IQLearn and MLE hyperparameters

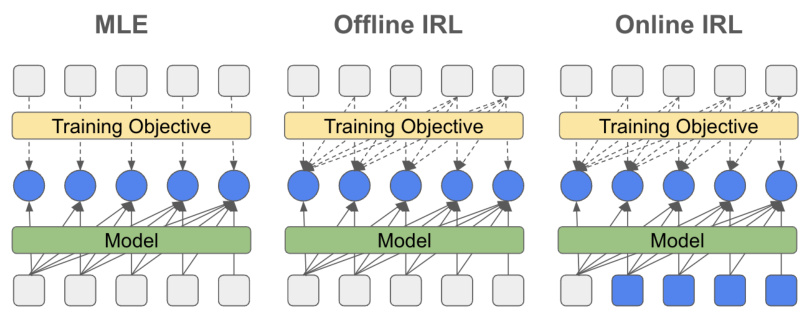

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used for the Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL) algorithm in the paper’s experiments. It specifies values for batch size, learning rate, warmup steps, KL strength (for the KL penalty in the policy optimization), and the number of random seeds used per experiment, for different sizes of the T5 language model (T5-base, T5-large, T5-xl). These settings were used to control the training process of the GAIL algorithm during the study.

read the caption

Table 4: GAIL hyperparameters

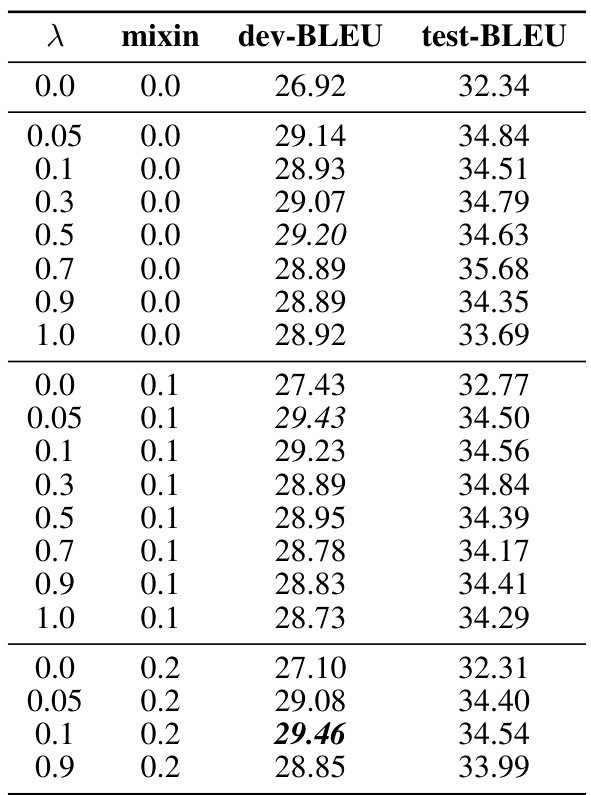

🔼 This table presents the results of offline IQLearn on the WMT22 dataset, comparing different regularization strengths (lambda) and the ratio of online data used (mixin). The table shows the dev-BLEU and test-BLEU scores for various combinations of these hyperparameters. Italicized entries represent the best dev-BLEU scores within each mixin group, while bolded entries indicate the overall best performance across all tested configurations.

read the caption

Table 5: WMT22 results for offline IQLearn initialised with a PaLM2 checkpoint. Italic – best dev BLEU in group (i.e. same mix value), bold – best overall.

Full paper#