↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Robots are often built from standardized parts, but controlling them requires training from scratch for each configuration. This is inefficient and limits robot adaptability. Existing solutions attempt to train universal controllers, which is computationally expensive and prone to overfitting. This paper tackles this problem with a new approach.

The proposed framework, MeMo, learns modular controllers that handle specific parts (like legs or arms). This modularity, combined with noise injection during training, allows for effective knowledge transfer between robots built with similar components. MeMo demonstrates improved training efficiency and generalization across diverse robotic morphologies and tasks, showcasing the benefits of a modular approach for learning reusable robot control policies.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the significant challenge of robot morphology transfer, enabling faster and more efficient robot control learning. It introduces a novel modularity objective and noise injection technique, improving training efficiency significantly compared to existing methods. This opens up new avenues for research in modular robotics and efficient reinforcement learning.

Visual Insights#

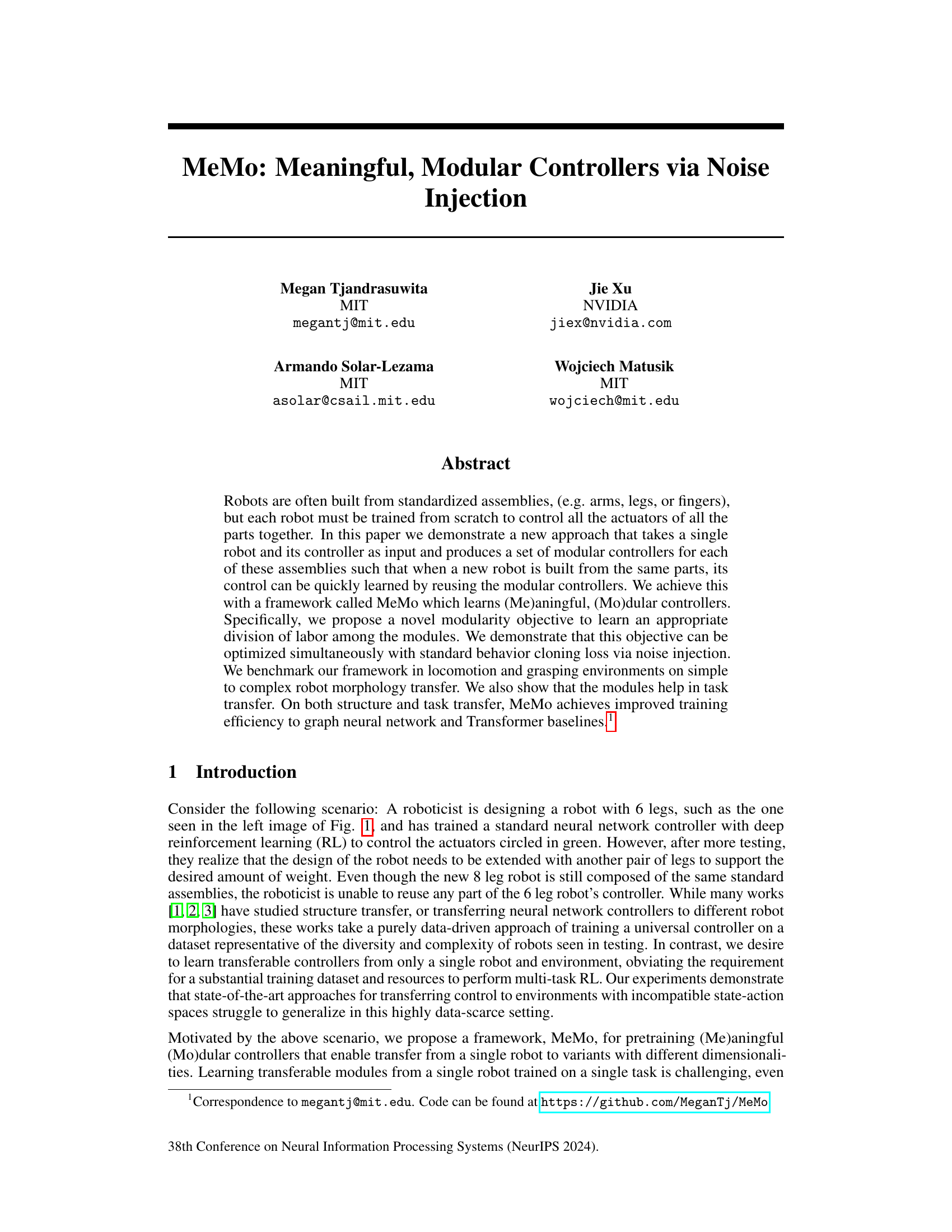

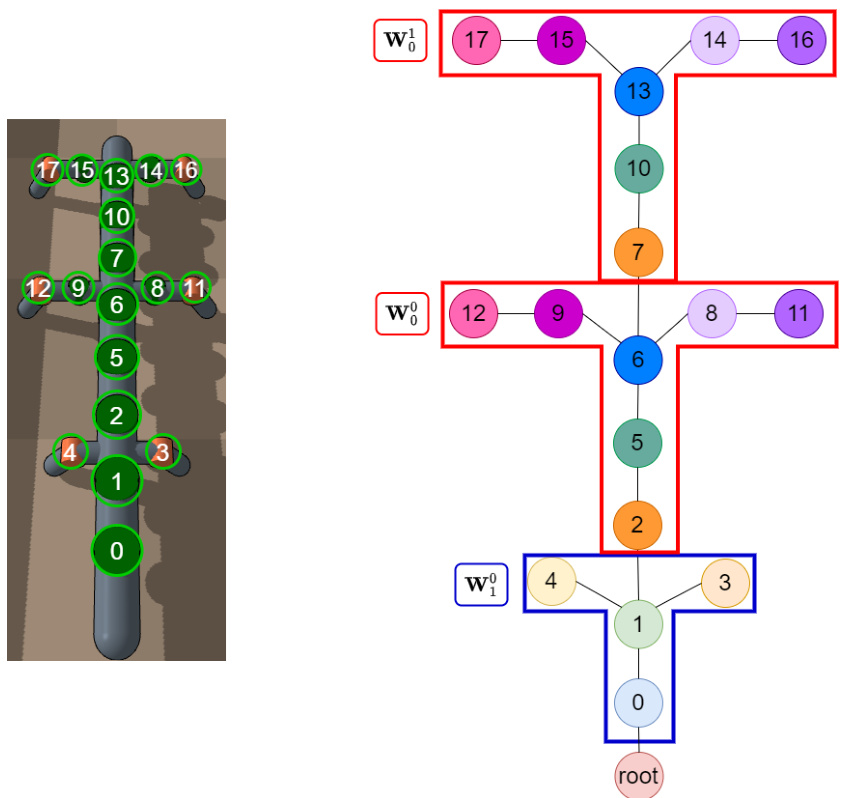

The figure shows the graph structure representation of a 6-legged robot’s physical structure (left) and its corresponding modular neural network controller (right). The physical structure displays individual joints of the robot, which are represented as nodes in the graph structure. Connections between these joints form the edges of the graph. The modular neural network controller shows the division of the network into different modules, each responsible for controlling specific parts of the robot (e.g., legs or body).

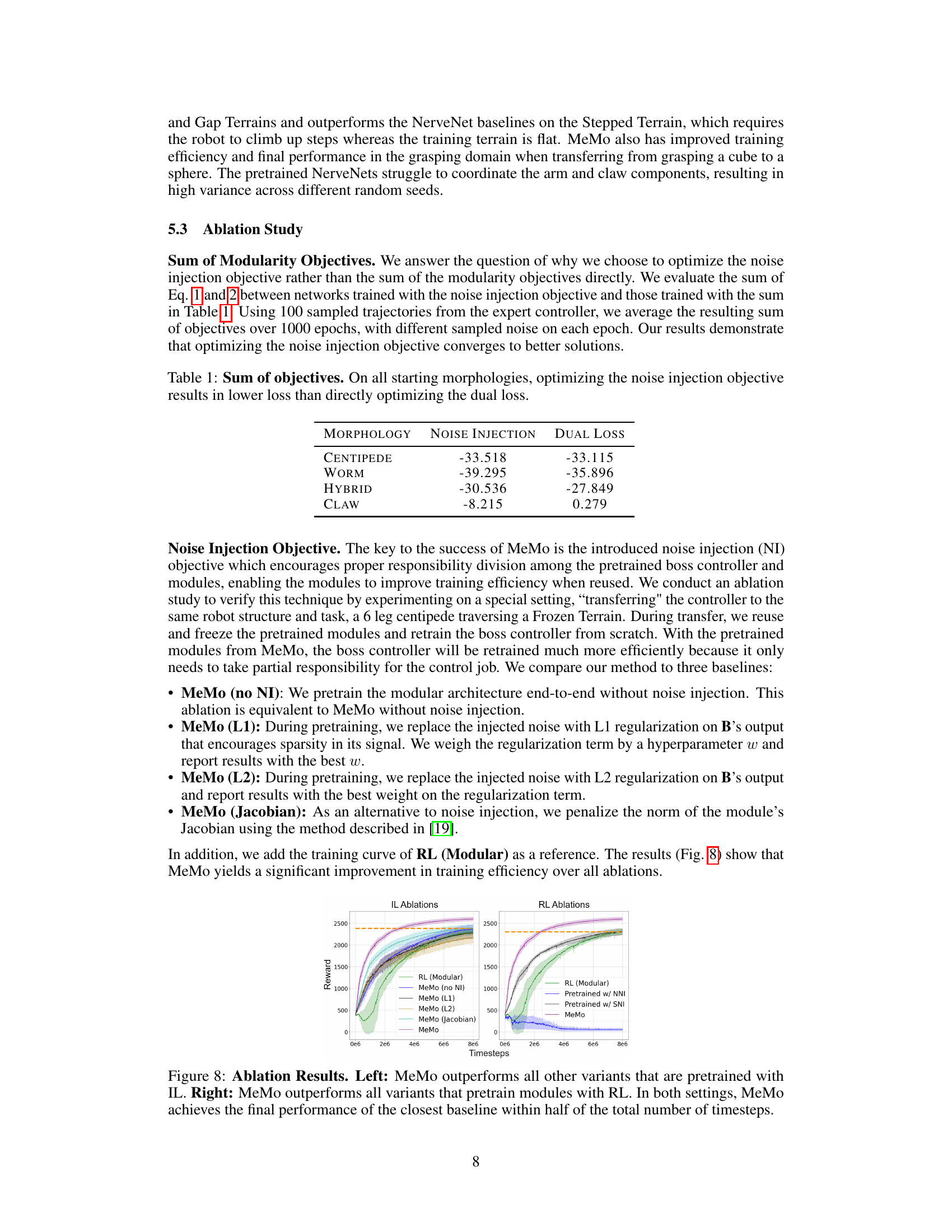

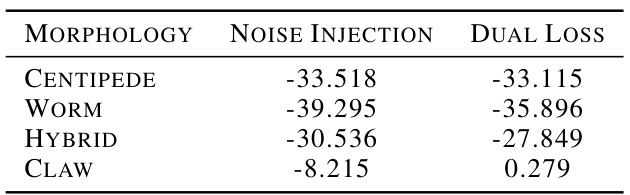

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing two methods for optimizing modularity objectives: noise injection and the direct optimization of the dual loss. The study was performed on four different robot morphologies (centipede, worm, hybrid, and claw). For each morphology, the table shows the average sum of the modularity objectives achieved after optimizing using either noise injection or the dual loss. The results consistently demonstrate that noise injection produces lower loss values, indicating that it is a more effective optimization strategy.

In-depth insights#

Modular Control#

Modular control, in the context of robotics, offers a powerful paradigm shift from monolithic control architectures. Instead of a single, complex controller governing all robot actuators, modular control decomposes the system into smaller, independent modules, each responsible for a specific subsystem or functionality (e.g., leg movement, arm manipulation). This approach promotes reusability and scalability, as modules can be readily combined and adapted for different robot morphologies or tasks, significantly reducing development time and effort. Modularity simplifies the design process, enabling easier understanding, debugging, and maintenance. However, challenges arise in coordinating the interactions between modules. Effective communication protocols and strategies for distributing control responsibilities are crucial for seamless integration and overall system performance. Noise injection techniques may play a vital role in achieving the desired balance between modular independence and overall system coordination. Future research should focus on developing more robust and efficient methods for managing inter-module communication, enabling improved adaptability and resilience to unexpected situations.

Noise Injection#

The concept of ’noise injection’ in the context of this research paper is a crucial technique for achieving meaningful modularity in robot controllers. By injecting noise into the system, specifically into the boss controller’s output signal, the authors force the worker modules to develop a more robust and less sensitive response. This encourages the modules to capture the intrinsic coordination mechanisms of their respective subassemblies, rather than relying heavily on the precise commands from the boss controller. The noise acts as a form of regularization, preventing overfitting and promoting better generalization when transferring the modules to new robot morphologies or tasks. The simultaneous optimization of a modularity objective and a standard behavior cloning loss through noise injection is a key innovation, demonstrating the efficacy of this approach. The ablation studies further highlight the importance of noise injection in achieving the desired level of modularity and transferability, showcasing its impact on training efficiency and ultimately the effectiveness of the proposed framework.

Transfer Learning#

The study’s exploration of transfer learning is a critical strength, demonstrating the framework’s ability to generalize beyond the specific robot initially trained. Structure transfer, where controllers trained on a simpler robot are adapted to more complex morphologies, showcases the modularity’s effectiveness. Similarly, task transfer experiments, applying pre-trained modules to different tasks, highlight the framework’s versatility and potential for broader applications. The results convincingly show improved training efficiency compared to baselines, underscoring the effectiveness of the modular design and noise injection technique. However, a more comprehensive evaluation across diverse morphologies and tasks would strengthen these findings. Future work could explore the framework’s limitations in transferring to drastically different morphologies or handling significant environmental changes. The scalability and robustness of the approach in real-world scenarios are key questions that warrant further investigation. Overall, the research provides a compelling case for the modular approach and pretraining through noise injection as valuable strategies for achieving efficient and robust robot control transfer.

Modularity Limits#

The concept of ‘Modularity Limits’ in a research paper would explore the boundaries and constraints of modular design. It would likely delve into situations where modularity, while offering advantages like easier maintenance and scalability, becomes a hindrance. Key aspects of such an analysis might include the complexity of inter-module communication, performance trade-offs, such as increased latency or reduced efficiency, and the difficulty of managing dependencies between modules. A crucial investigation would be the point where the benefits of modularity are outweighed by its costs; that is, identifying the optimal level of modularity. The analysis may compare different modularity approaches, evaluate the impact of varying module granularity on system performance, and address the challenges in achieving seamless integration between modules. Practical implications of modularity limits could encompass factors like development cost, debugging complexity, and the limitations of reuse in diverse applications. A thoughtful discussion of modularity limits offers valuable insights for engineers and researchers seeking to design effective and efficient systems.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section implicitly suggests several promising research avenues. Extending MeMo to real-world scenarios is paramount, acknowledging the inherent challenges of transferring simulated learning to complex, real-world robotics. This requires addressing the sim-to-real gap, including handling environmental variability, hardware inconsistencies, and discrepancies in simulated and real physics. Another crucial area is improving the task transfer capabilities of MeMo. While the current framework shows promise, enhancing its ability to handle tasks significantly different from the training task remains a priority. This might involve incorporating task semantics explicitly into the architecture. Scaling MeMo to more complex robots and multi-robot systems is also essential, moving beyond the relatively simple morphologies explored in the paper. Finally, addressing the potential memory footprint increase associated with imitation learning is important for practical applications. Exploring alternative pretraining methods or more efficient data representations could help mitigate this.

More visual insights#

More on figures

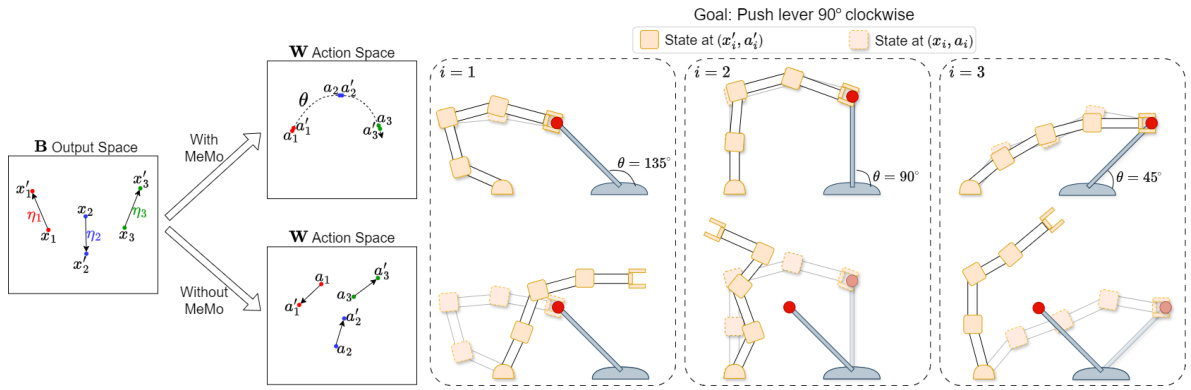

This figure illustrates the impact of the modularity objective in MeMo on a robot arm task. With MeMo, the worker module (W) learns a low-dimensional representation of the actions needed to control the lever, effectively mapping the boss module’s (B) signal to an appropriate lever position. Adding noise to B’s signal results in minimal impact on lever position because W maintains its narrow interface. In contrast, without MeMo, W doesn’t learn such a narrow interface, and noise in B’s signal causes significant deviations from the desired trajectory. This highlights how MeMo’s modularity objective forces the worker module to learn a more robust and efficient control strategy.

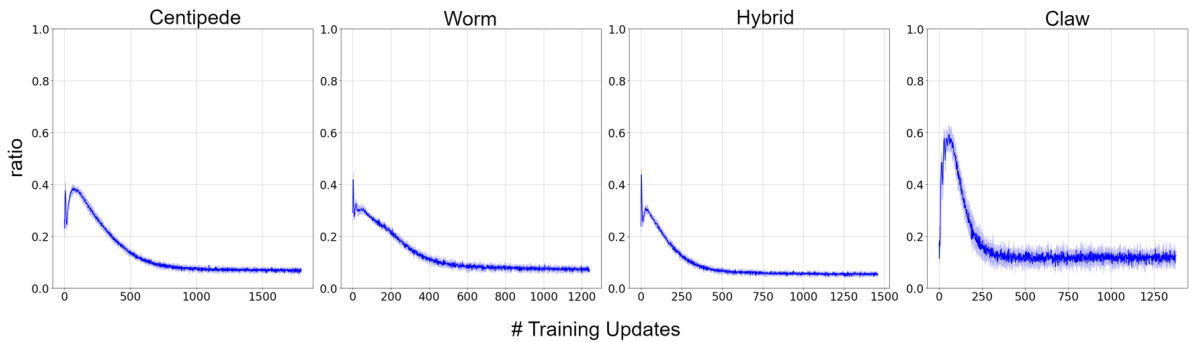

This figure shows the ratio of the magnitude of the mean product term to the sum of the behavior cloning loss and invariance to noise loss during training. The ratio is consistently less than 1 across different robot morphologies (centipede, worm, hybrid, claw), indicating that the modularity objectives dominate the overall loss. The shaded areas represent the standard deviation over 5 training runs.

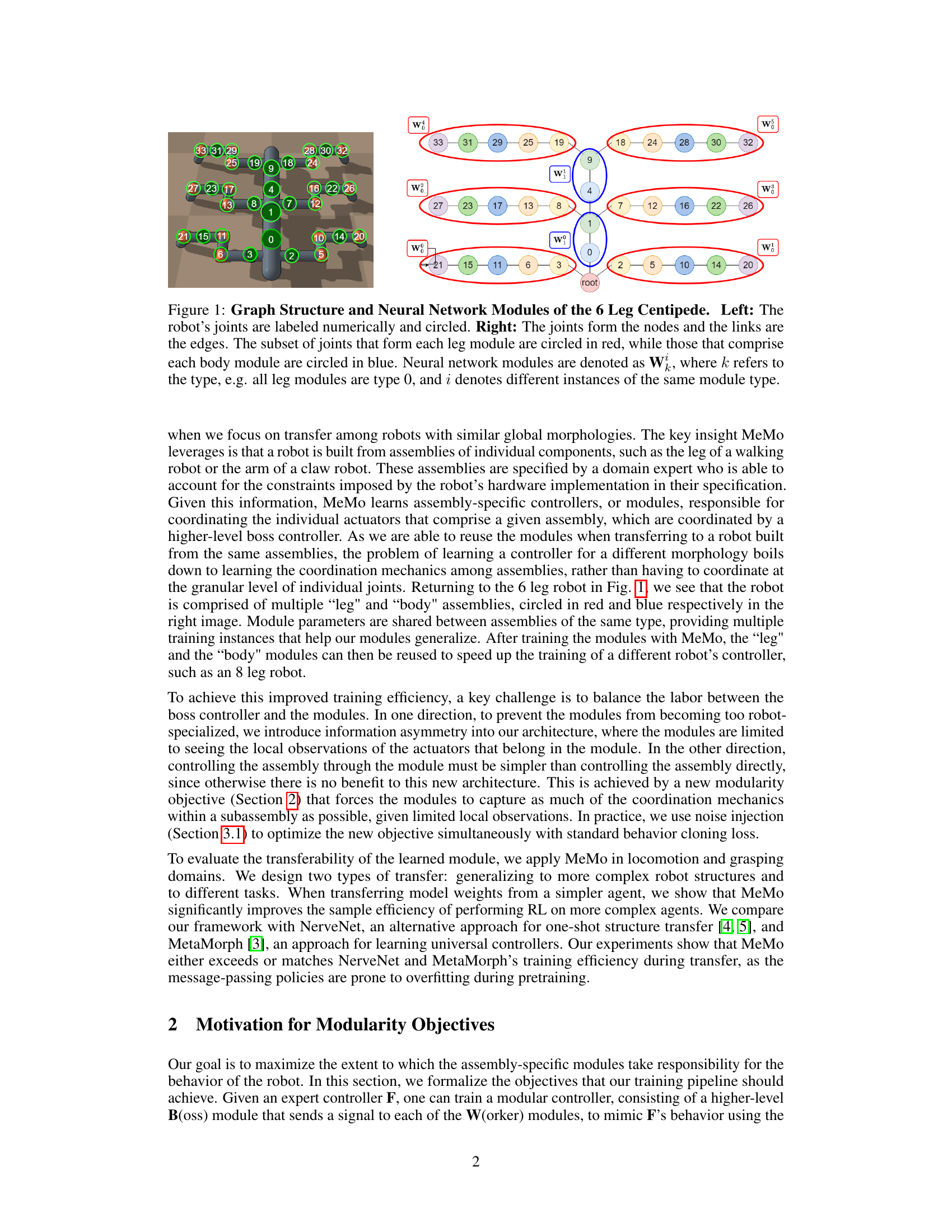

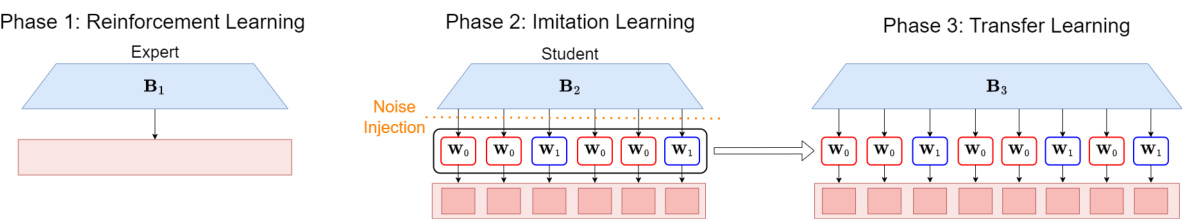

This figure illustrates the three-phase training pipeline used in the MeMo framework. Phase 1 involves training an expert controller using reinforcement learning (RL). Phase 2 uses imitation learning with noise injection to pretrain modular controllers. Phase 3 transfers the pretrained modules to a new context (different robot morphology or task) and retrains the boss controller.

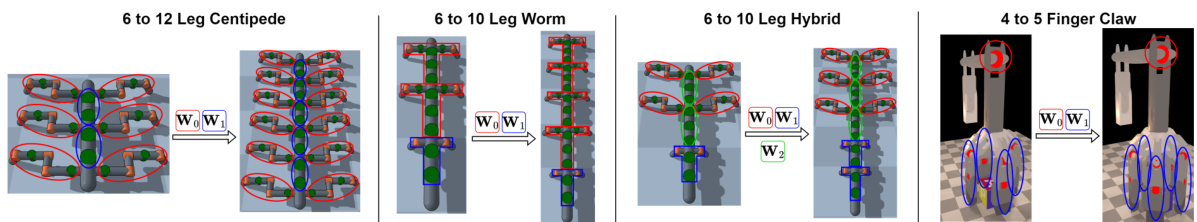

This figure shows four examples of structure transfer tasks used in the paper’s experiments. Each example demonstrates transferring learned modules from a simpler robot morphology to a more complex one. The figure highlights the modularity of the approach by showing how specific modules (legs, body, head, arm, fingers) can be reused and adapted for different robot designs.

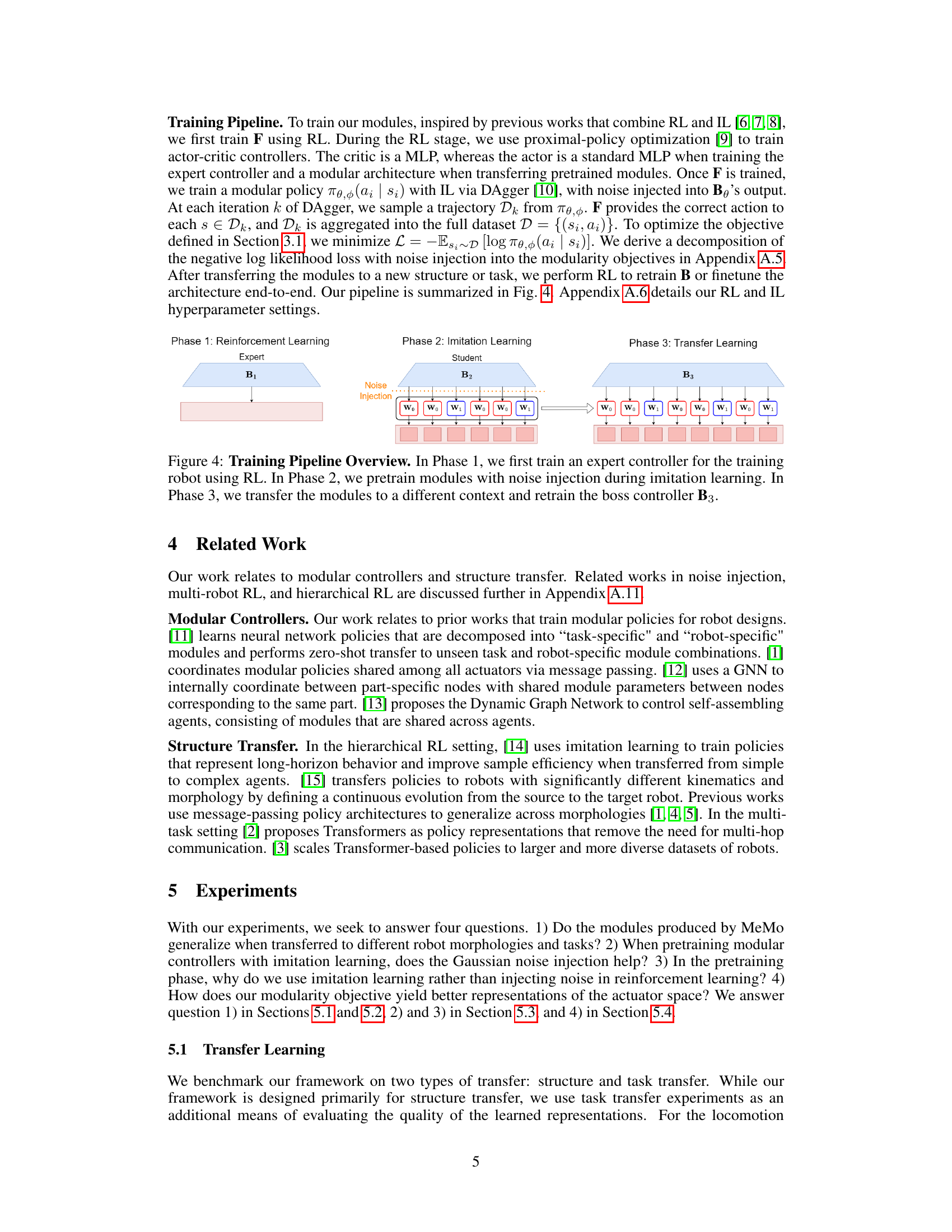

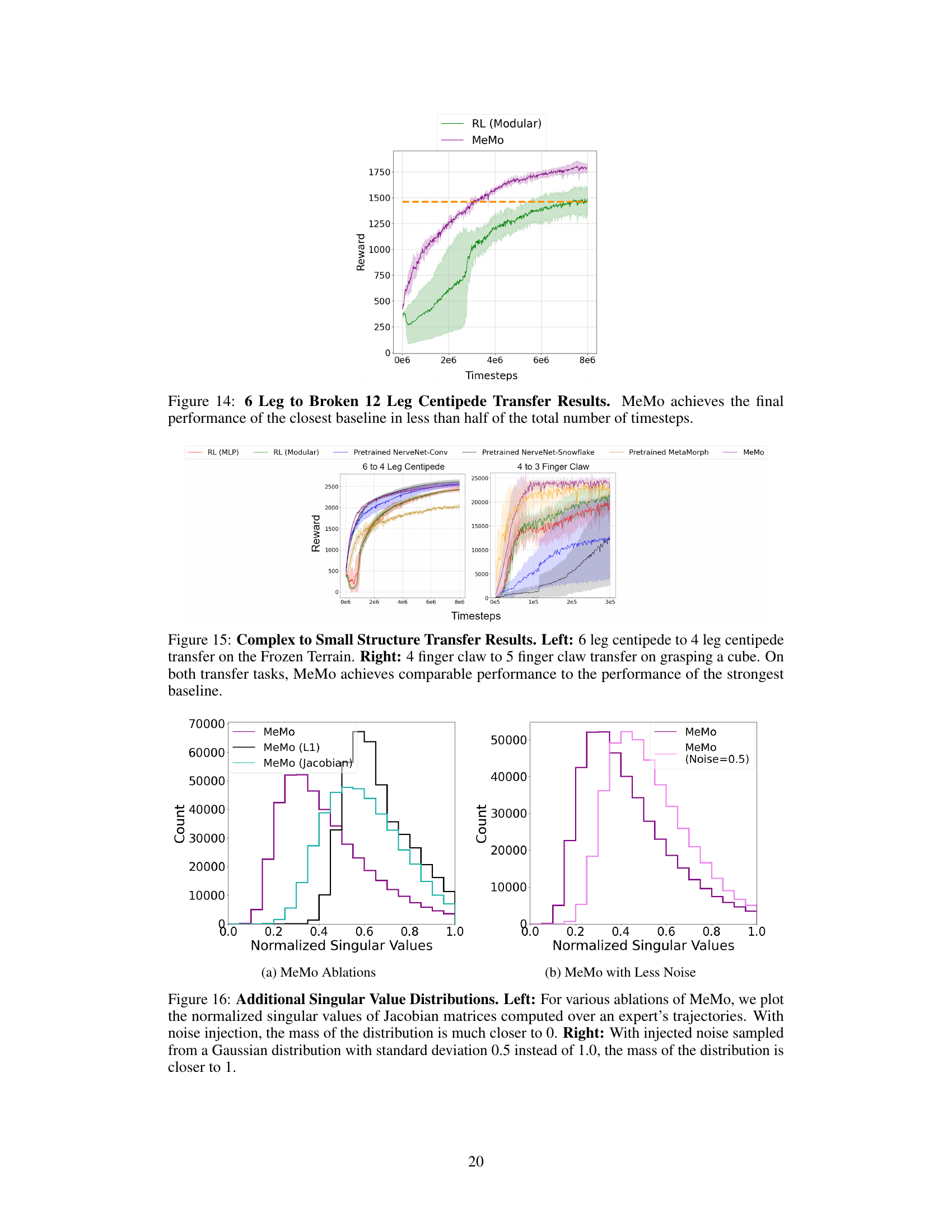

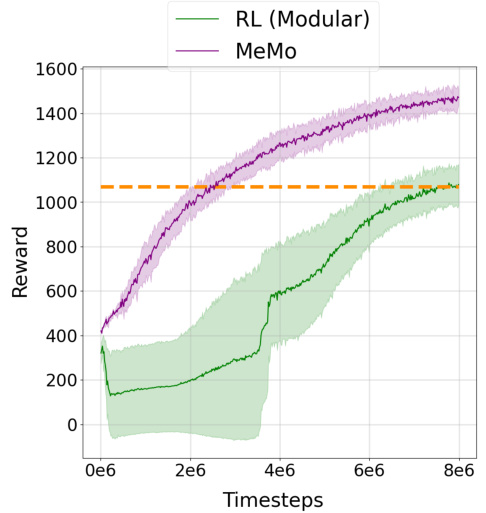

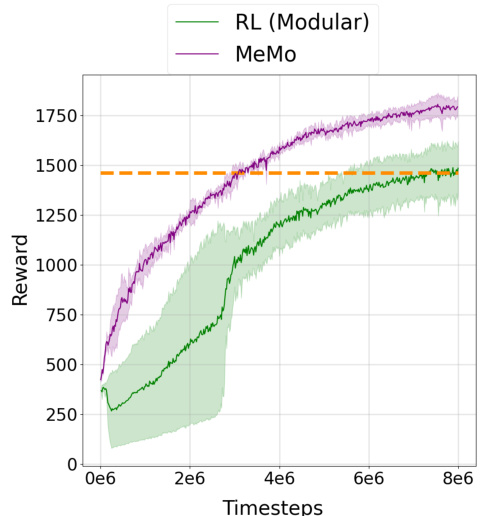

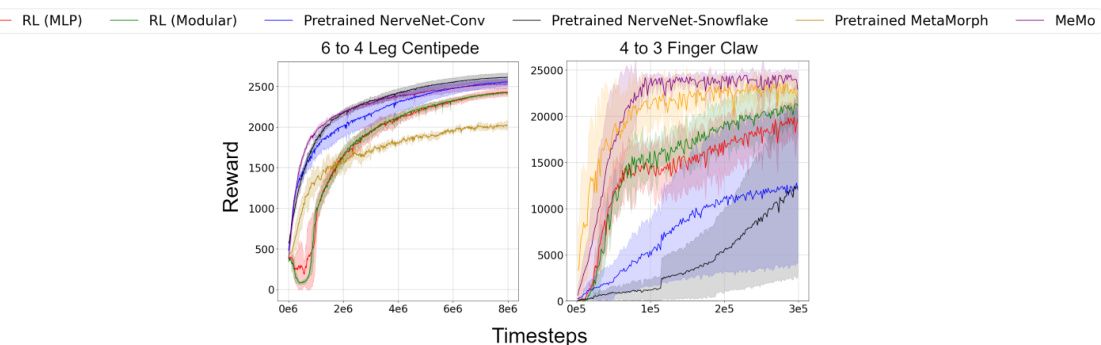

This figure presents the results of structure transfer experiments. Four different structure transfer tasks are shown, each comparing the performance of MeMo against several baselines. The tasks involve transferring learned modules from a simpler robot morphology to a more complex one. The dashed orange lines highlight that MeMo achieves comparable or better performance than the best baseline within half the number of timesteps.

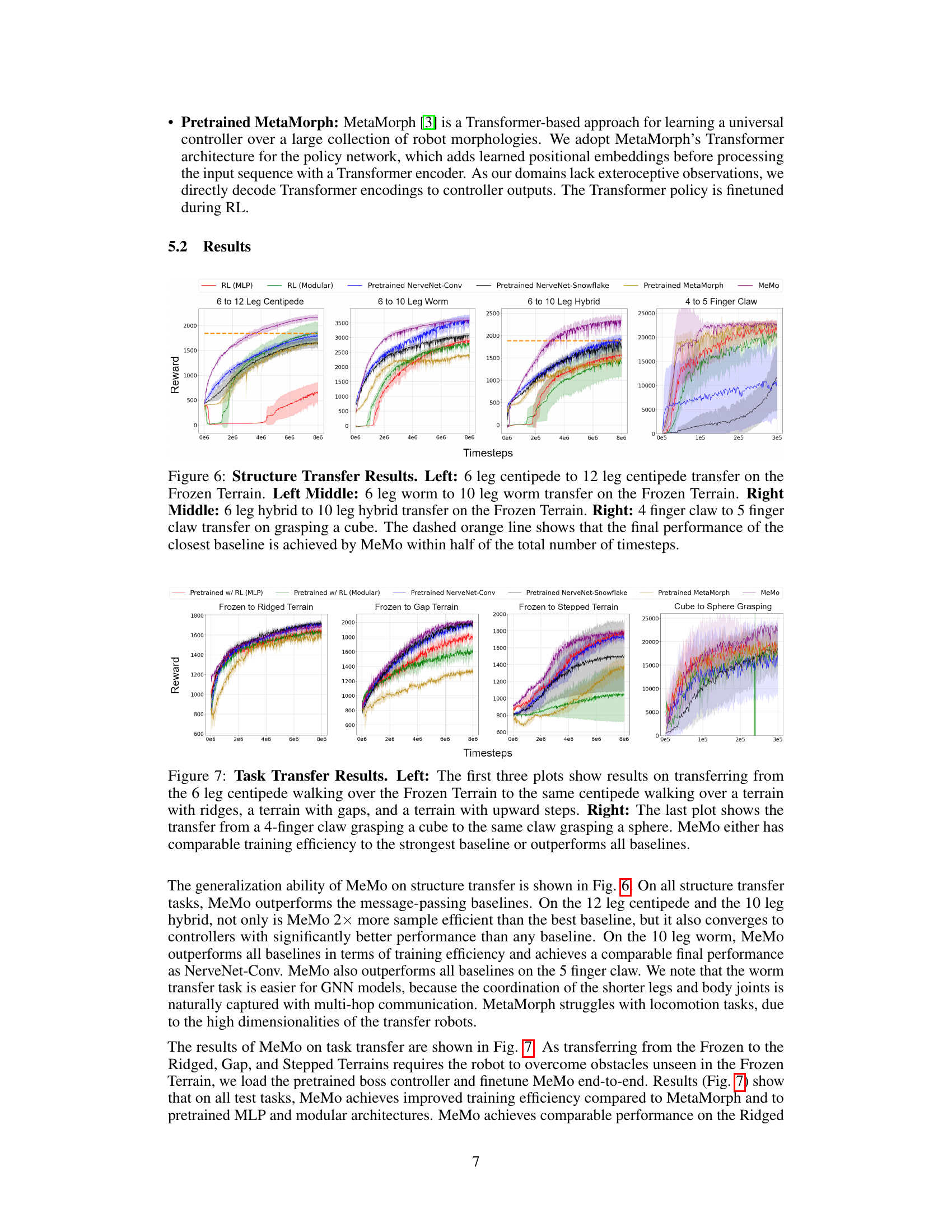

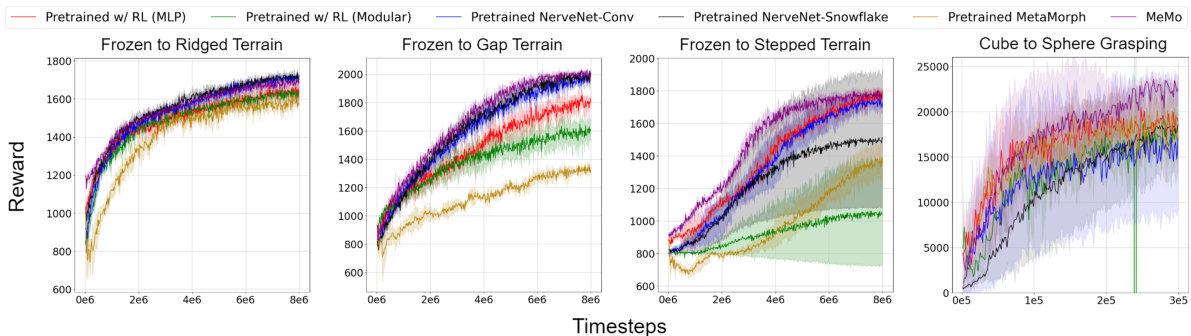

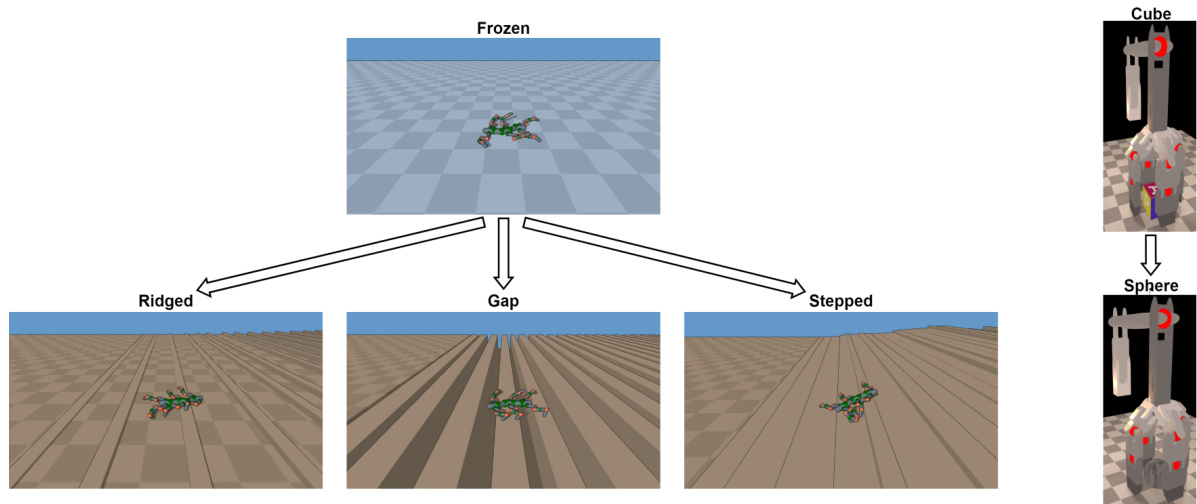

This figure presents the results of task transfer experiments. The left side shows three locomotion task transfer experiments, where a pretrained controller is tested on terrains with different levels of difficulty (ridges, gaps, steps) compared to its training terrain. The right side shows a grasping task transfer experiment, comparing the ability to transfer a controller trained on grasping a cube to grasping a sphere. The key takeaway is that MeMo demonstrates either comparable or superior performance in training efficiency compared to other methods.

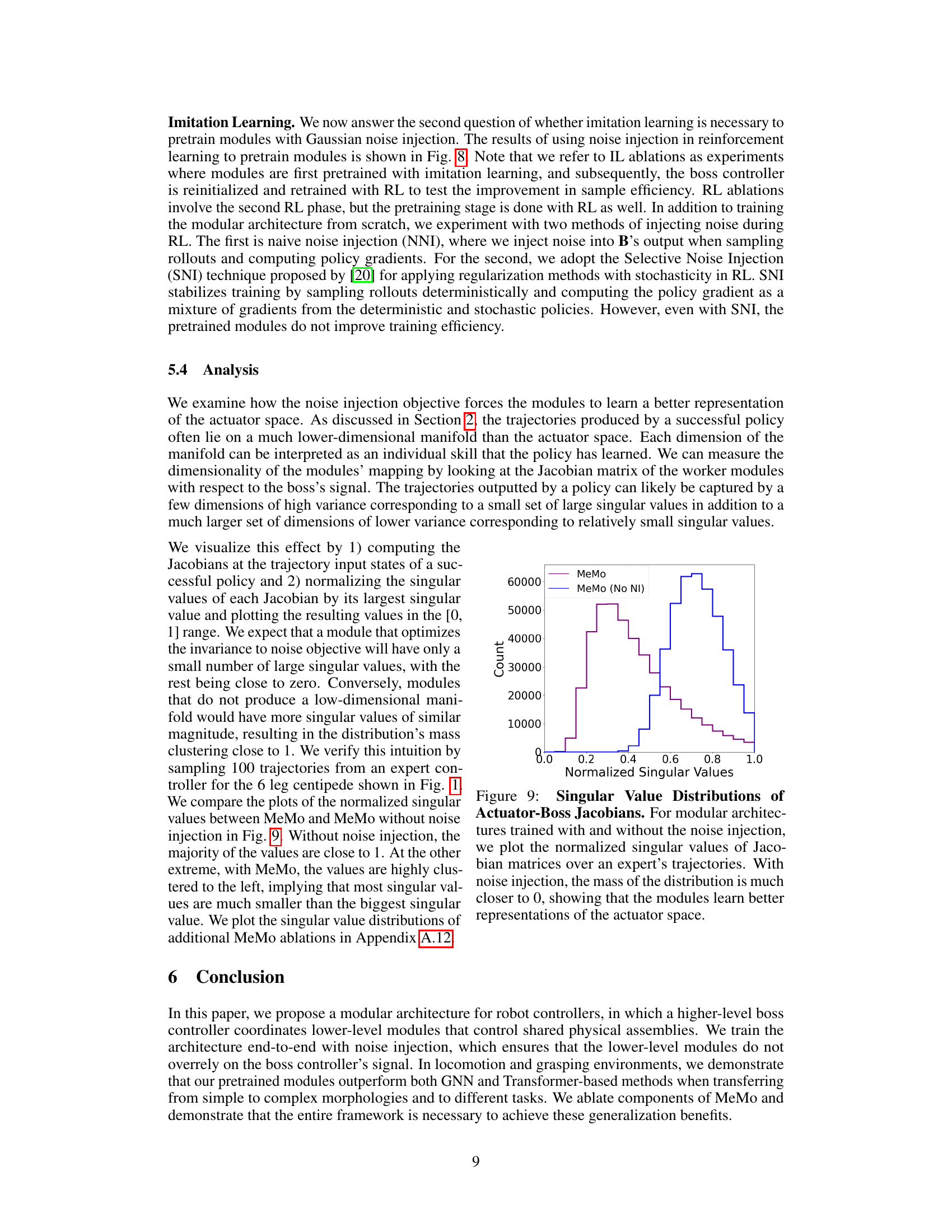

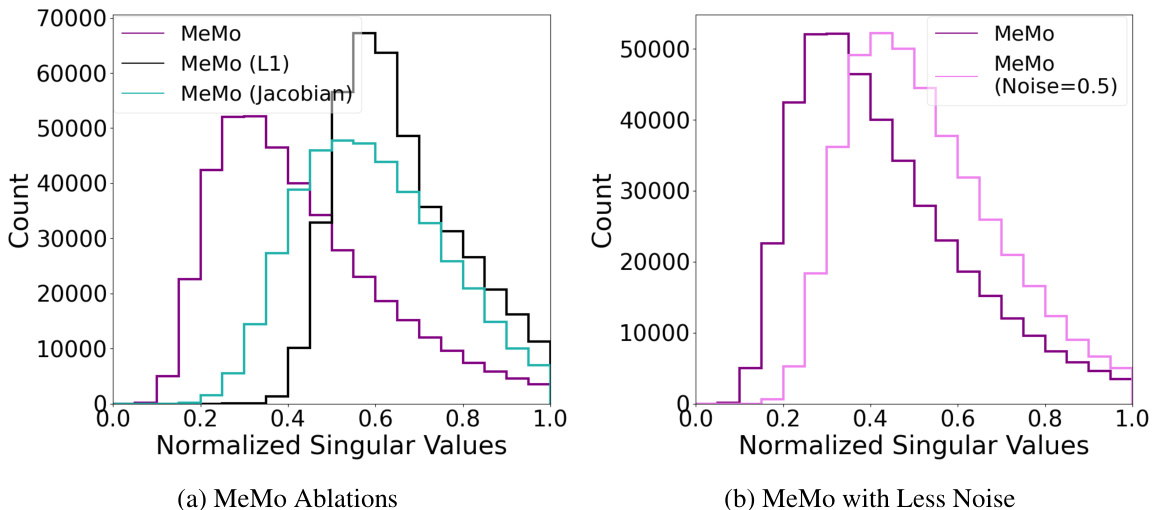

This figure presents the results of ablation studies performed to analyze the impact of different components of the MeMo framework. The left panel shows the results of ablations on the imitation learning (IL) stage, comparing the performance of MeMo against variants without noise injection, with L1 or L2 regularization, or using Jacobian penalty. The right panel shows results of ablations on the reinforcement learning (RL) stage, comparing MeMo’s performance against a standard modular RL approach and variants with naive or selective noise injection during RL pretraining. The results demonstrate MeMo’s superior performance in sample efficiency compared to all variants.

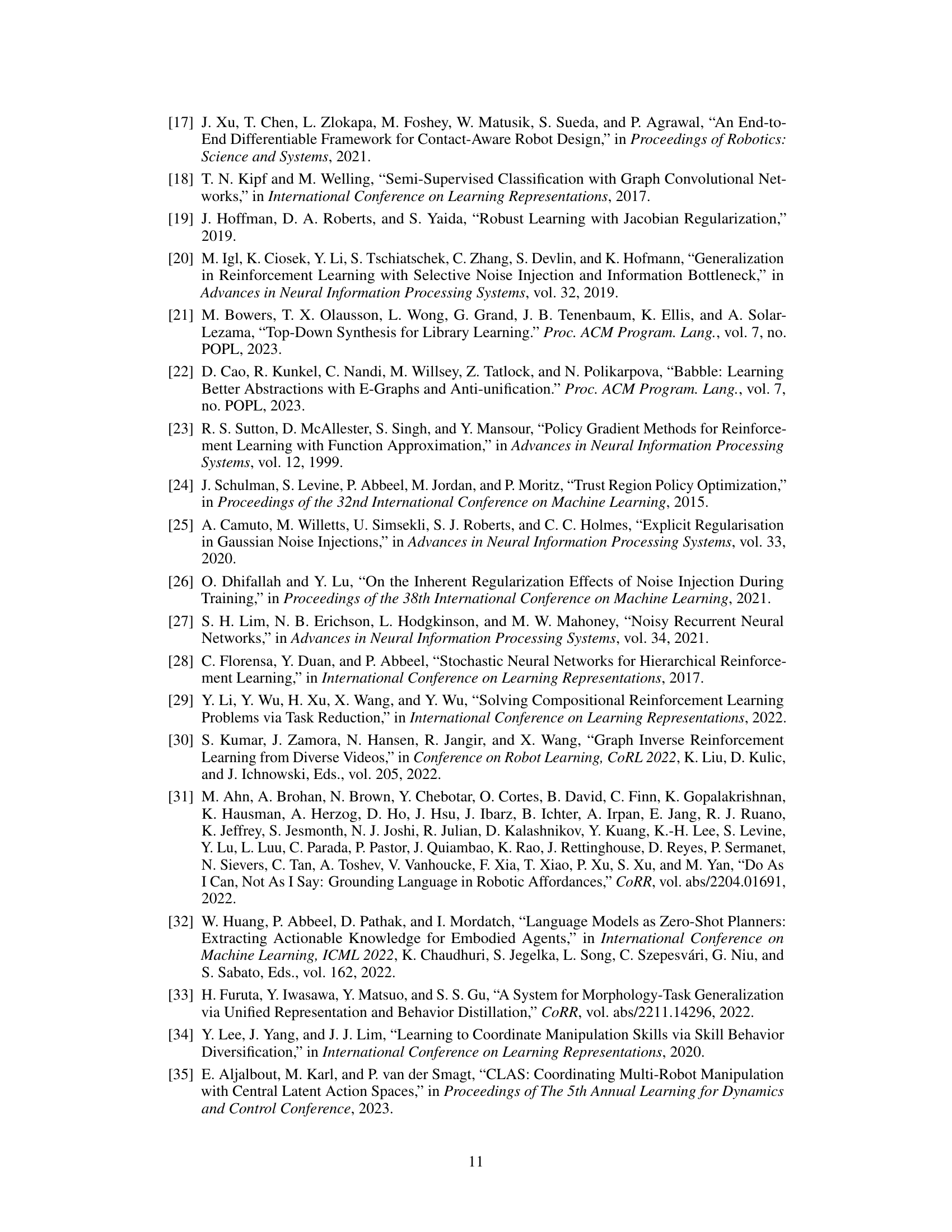

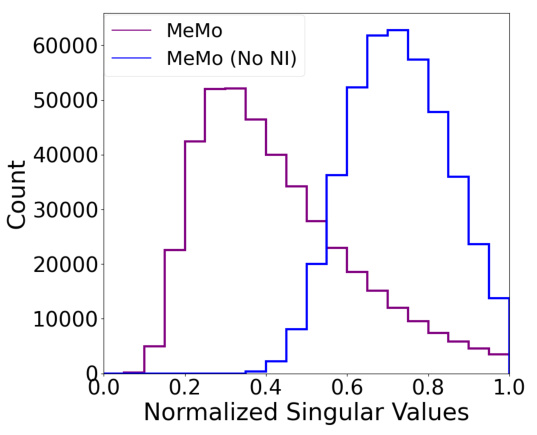

This figure compares the singular value distributions of the Jacobian matrices of the actuator-boss for models trained with and without noise injection. The singular values represent the sensitivity of the modules’ outputs to changes in the boss controller’s signal. The distribution’s mass being closer to 0 for models trained with noise injection indicates that those models have learned a more efficient and compact representation of the actuator space, making the modules more robust to noise and more easily transferable.

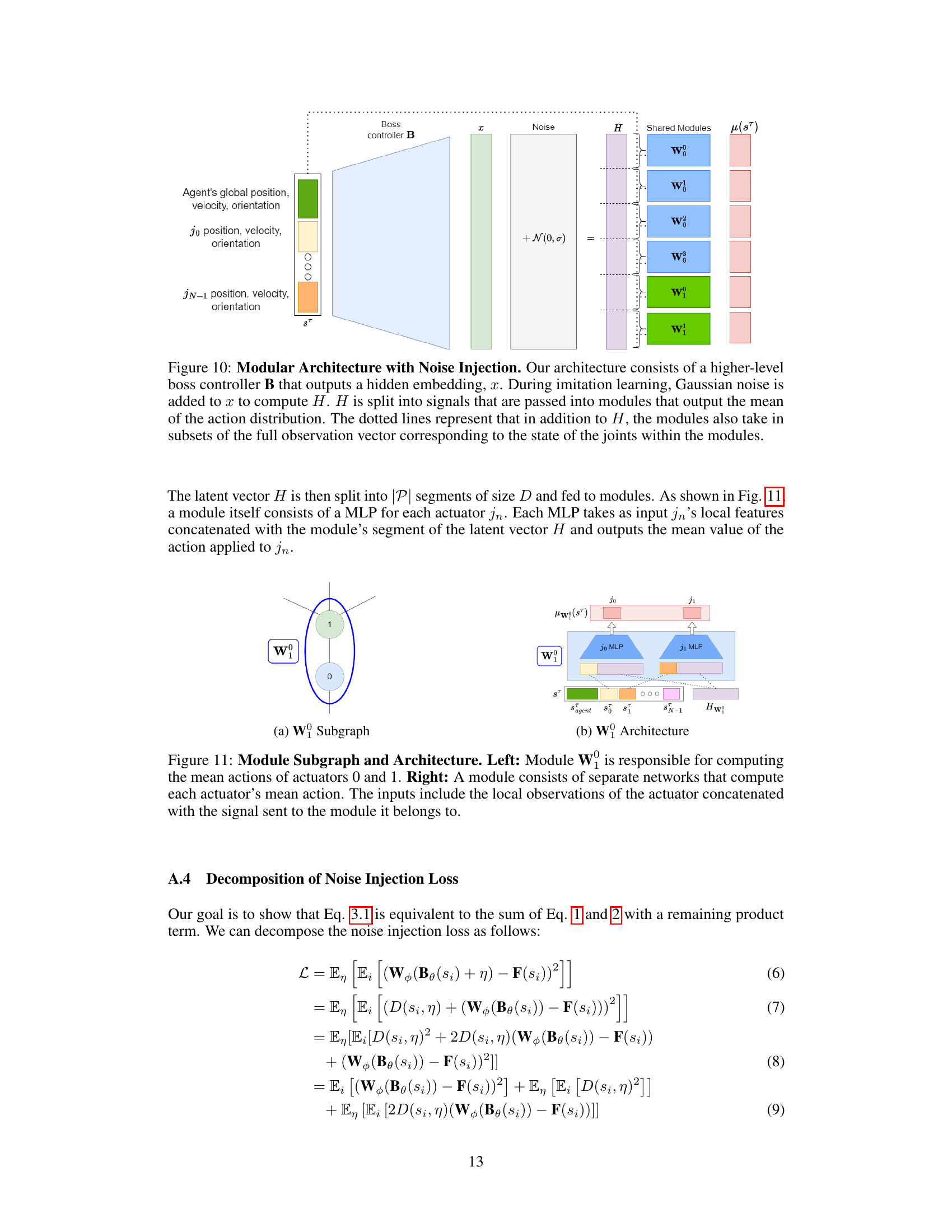

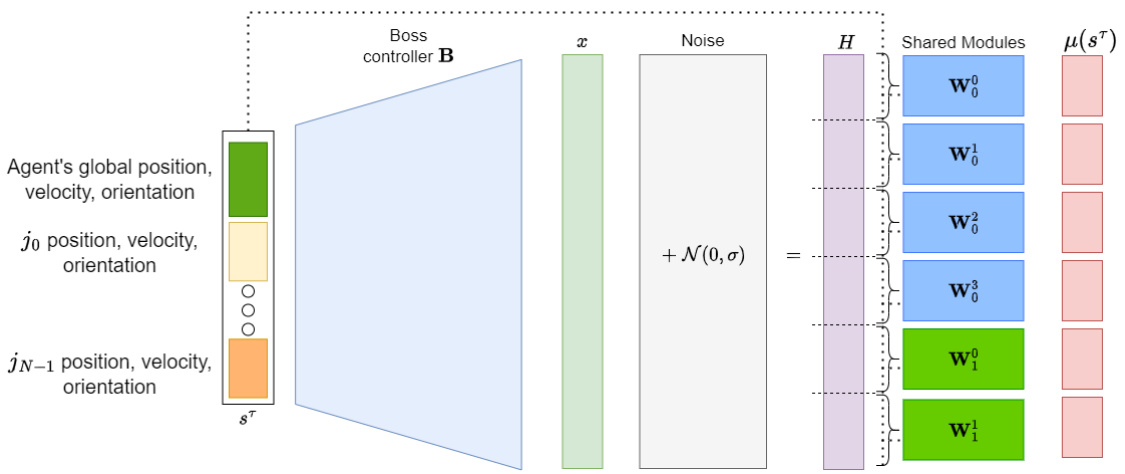

This figure illustrates the modular architecture of MeMo, showing how a higher-level ‘boss’ controller (B) processes the robot’s global and local observations. It then uses these observations, along with added noise, to generate signals for lower-level ‘worker’ modules (W). Each worker module is responsible for controlling a specific part of the robot, enabling modularity and transferability to other robot morphologies.

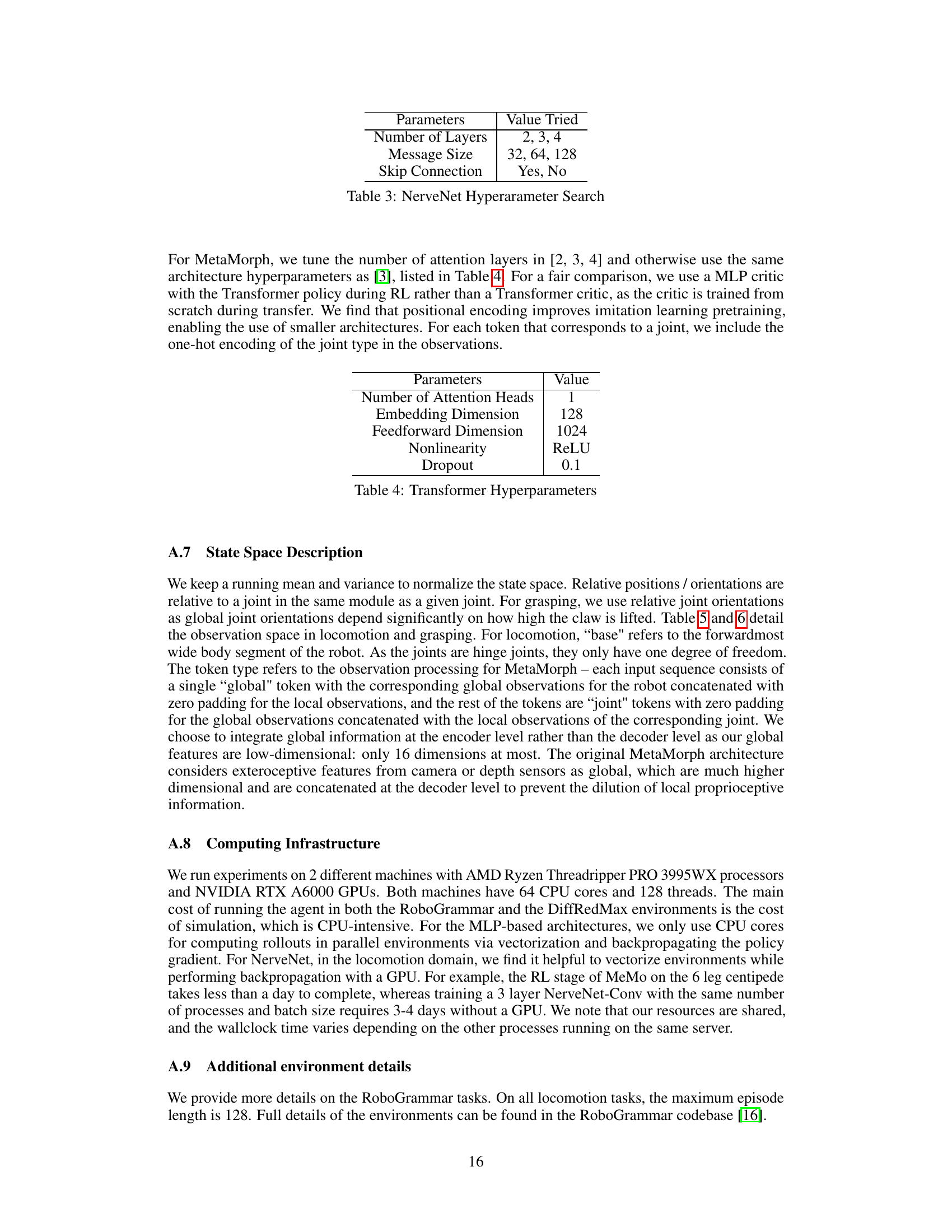

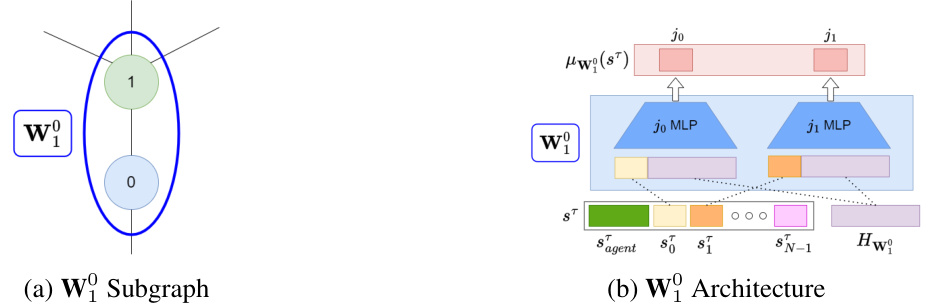

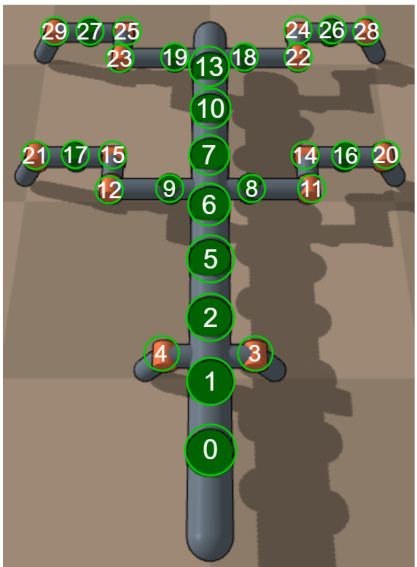

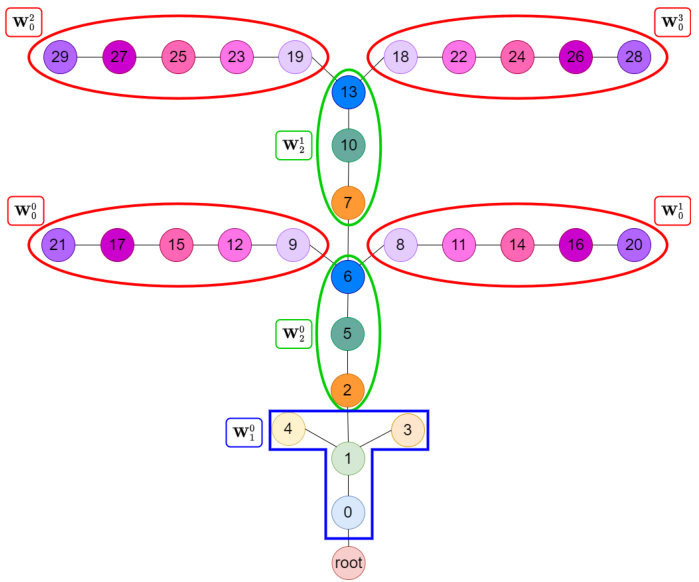

This figure shows the internal structure of a module in the MeMo architecture. The left panel illustrates a subgraph representing how actuators are grouped into modules. The right panel shows the detailed architecture of a single module (Wᵢ), which consists of separate Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs) for each actuator in the module. Each MLP takes as input both local observations specific to that actuator and a shared signal from the boss controller. This modular design is crucial for the transferability of the controller to different robot morphologies.

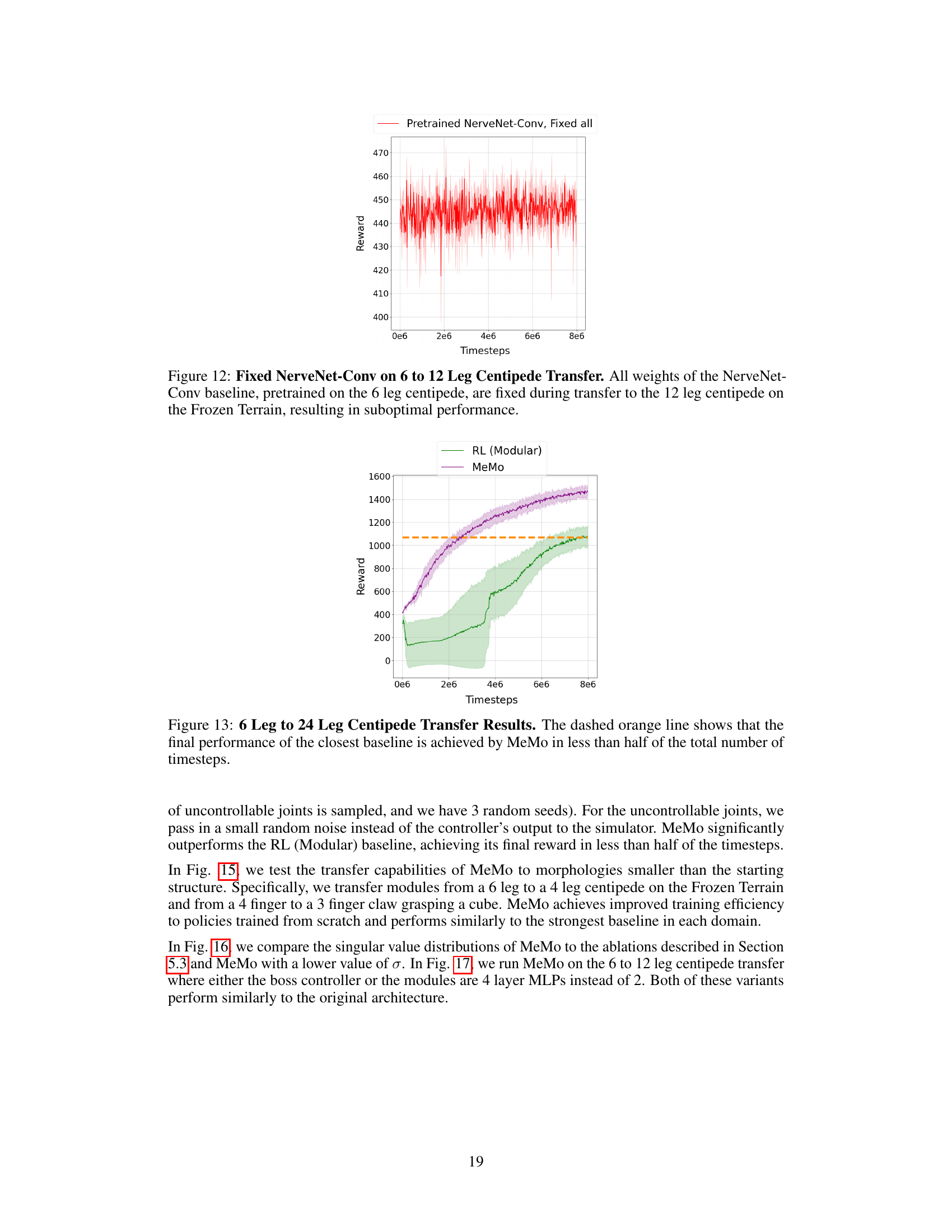

This figure shows the results of transferring a pretrained NerveNet-Conv model from a 6-legged centipede to a 12-legged centipede while keeping all weights fixed. The experiment is performed on the ‘Frozen Terrain’ task. The plot shows that the reward obtained remains consistently low, indicating that the model fails to adapt effectively to the new morphology and significantly underperforms compared to fine-tuning or retraining.

This figure presents the results of structure transfer experiments on four different robotic morphologies. The plots show the learning curves (reward vs. timesteps) for MeMo and several baseline methods on each transfer task. The dashed orange lines highlight MeMo’s improved sample efficiency, reaching the performance of the best baseline method in fewer training steps.

This figure presents the results of structure transfer experiments across four different robotic morphologies. It showcases the performance of MeMo (the proposed method) compared to several baselines (RL with MLP, RL with modular architecture, pretrained NerveNet-Conv, pretrained NerveNet-Snowflake, and pretrained MetaMorph). Each subplot shows the training curves for a specific transfer task. For example, the first subplot displays the results of transferring a controller trained on a 6-legged centipede to a 12-legged centipede. The dashed orange line highlights the improved training efficiency of MeMo, achieving comparable performance to the best baseline in considerably fewer training steps.

This figure shows four different structure transfer tasks used to evaluate the MeMo framework. Each task involves transferring learned modules from a simpler robot morphology to a more complex one. The tasks showcase MeMo’s ability to generalize across various robot designs by reusing previously learned modules. The simpler robots are 6-legged centipedes, 6-legged worms, 6-legged hybrids, and 4-fingered claws; the more complex robots are 12-legged centipedes, 10-legged worms, 10-legged hybrids, and 5-fingered claws, respectively.

This figure shows the distribution of normalized singular values of Jacobian matrices for different versions of the MeMo algorithm. The left plot compares MeMo with ablations (removing noise injection or using L1/L2 regularization instead). It demonstrates that noise injection is key to producing a distribution where most singular values are close to zero, indicating a lower-dimensional representation of the actuator space. The right plot shows that even with less noise (standard deviation 0.5 instead of 1.0), the distribution shifts towards having more singular values closer to 1, highlighting the importance of sufficient noise for this effect.

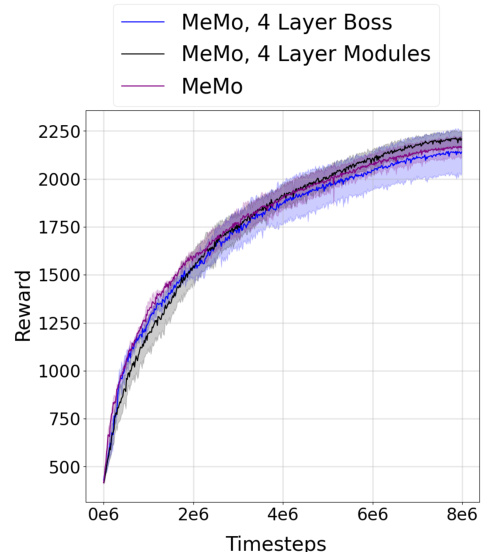

This figure shows the results of an ablation study on the MeMo architecture. The experiment involved transferring a controller trained on a 6-legged robot to a 12-legged robot. Three different architectures were compared: the original MeMo architecture, a variant with a 4-layer boss controller, and a variant with 4-layer modules. The results show that all three architectures achieve comparable performance, indicating the robustness of the MeMo approach to variations in network depth.

This figure demonstrates four different structure transfer tasks used in the paper’s experiments. Each task involves transferring pre-trained modules (representing robot components like legs or arms) from a simpler robot morphology to a more complex one. The figure visually shows the initial and final robot morphologies for each transfer task, illustrating how the pre-trained modules are reused and adapted to control the new, more complex robot.

This figure shows the 6-leg worm robot and its corresponding graph representation. The left panel displays a rendered image of the robot, with each joint numerically labeled and circled. The right panel presents a graph where nodes represent joints and edges represent connections between joints. Crucially, the joints grouped as ‘head’ modules are circled in red, while those forming the ‘body’ modules are circled in blue. This visualization illustrates the modular structure that the MeMo framework leverages for controller design.

This figure shows the graph structure representation of a six-legged robot. The left panel shows a physical rendering of the robot with its joints numerically labeled. The right panel provides an abstract graph representation of the robot where nodes represent joints and edges represent connections between joints. The figure highlights how the joints are grouped into modules; those forming legs are circled in red, while those forming the body are circled in blue. Each module will be associated with a neural network for control.

This figure shows the graph structure and the neural network modules for a 6-legged worm robot. The left panel shows a rendered image of the robot with its joints numerically labeled. The right panel provides a graphical representation of the robot’s structure as a graph, where each node is a joint and each edge indicates a connection between joints. The joints comprising the ‘head’ module are highlighted in red, while those forming the ‘body’ modules are highlighted in blue. This visualization aids in understanding how the robot’s morphology is represented in a modular way for control purposes within the MeMo framework.

This figure shows the modular architecture of the MeMo framework. It depicts a hierarchical structure where a higher-level ‘boss’ controller (B) processes the overall robot state and generates a hidden embedding (x). Gaussian noise is injected into this embedding before being split and fed into individual lower-level worker modules (W). Each module is responsible for controlling a specific assembly of the robot, shown as different colored circles. Importantly, each module also receives a subset of the full observation vector related specifically to the joints it controls (shown as dotted lines).

More on tables

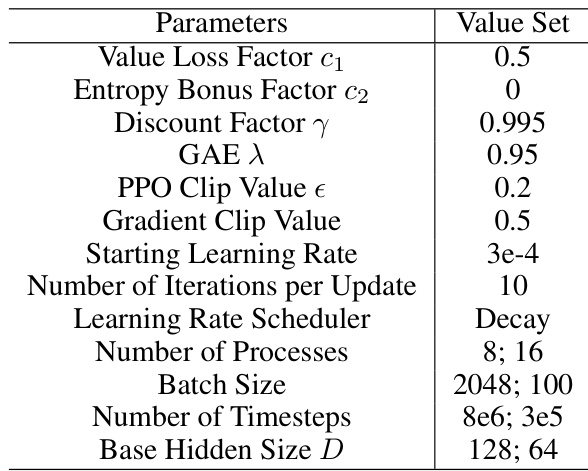

This table lists the hyperparameters used for reinforcement learning (RL) in the paper’s experiments. It shows the values used for various parameters such as the value loss factor, entropy bonus factor, discount factor, GAE lambda, PPO clip value, gradient clip value, starting learning rate, number of iterations per update, learning rate scheduler, number of processes, batch size, number of timesteps, and base hidden size. Different values are provided for locomotion and grasping tasks, reflecting the different requirements of these distinct robotic control problems.

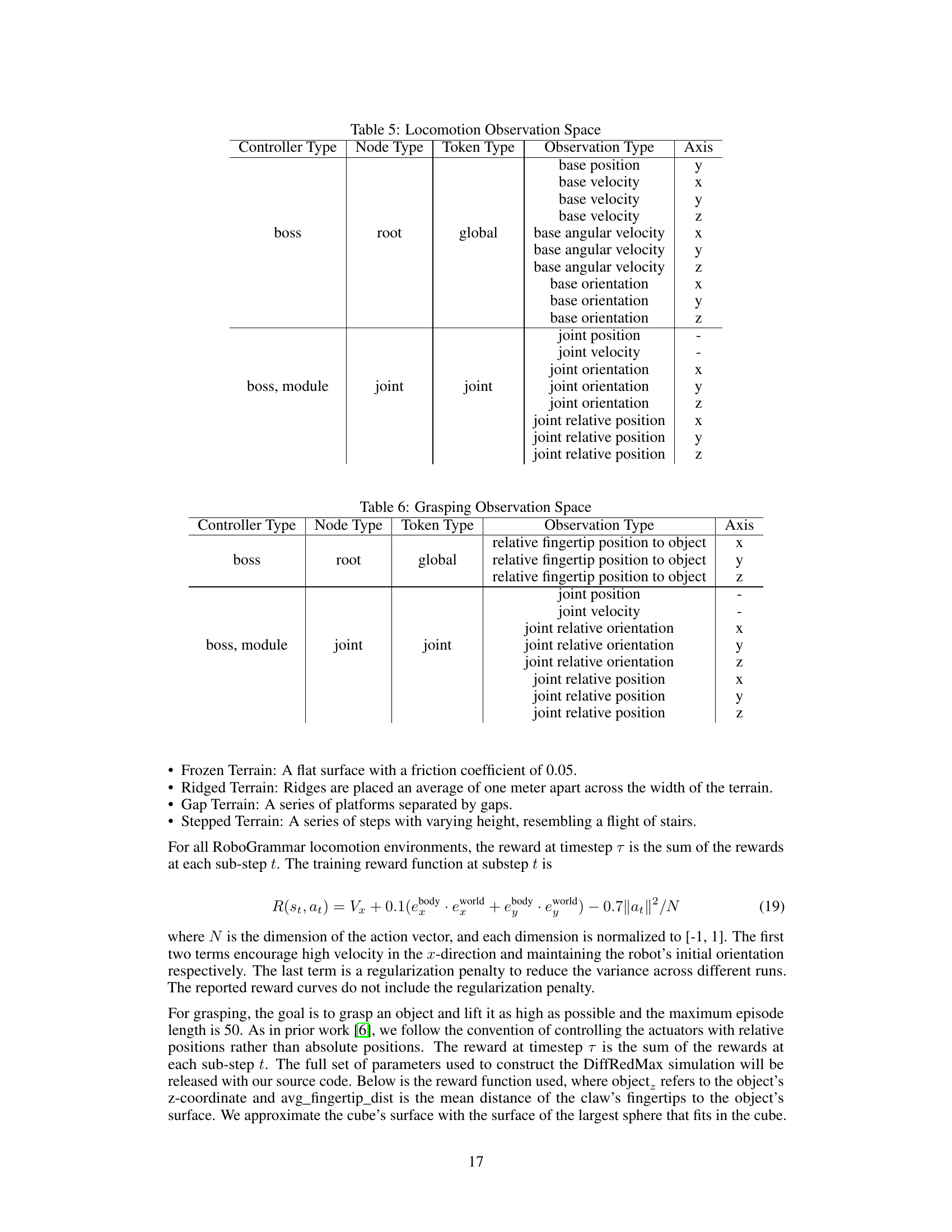

This table shows the hyperparameters used for the NerveNet model, including the number of layers, message size, and whether or not a skip connection was used. The values tried for each parameter during hyperparameter tuning are also listed.

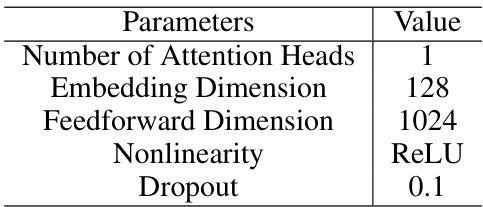

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the Transformer-based architecture in the MetaMorph baseline. It includes the number of attention heads, the embedding dimension, the feedforward dimension, the activation function used (ReLU), and the dropout rate.

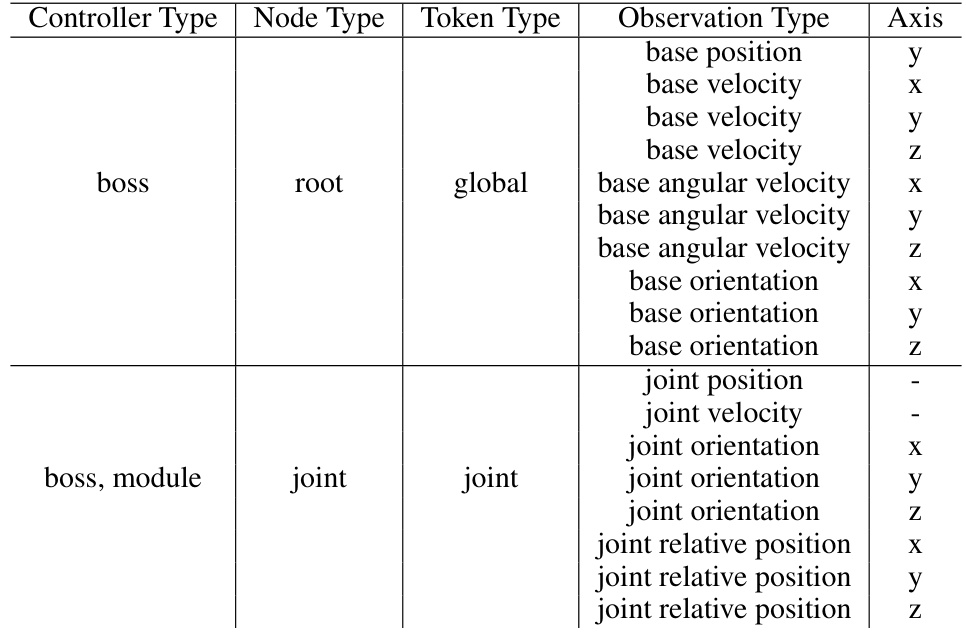

This table details the observation space used in the locomotion experiments. It breaks down the observations by controller type (boss, boss, module), node type (root, joint), token type (global, joint), observation type (position, velocity, orientation), and axis (x, y, z). The table shows which observations are available to different parts of the control system for the locomotion task.

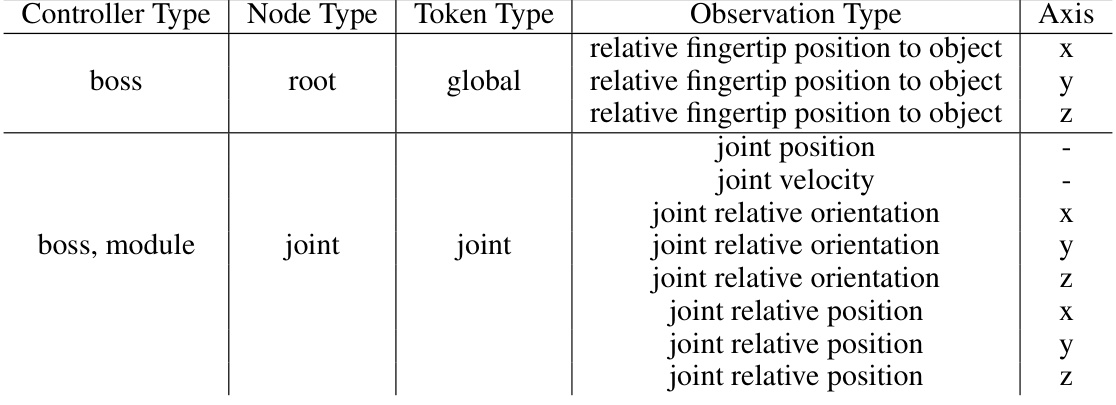

This table details the observation space used in the grasping experiments. It shows what type of controller (boss or boss, module) is used, the node type (root or joint), the token type (global or joint), the observation type (relative fingertip position to object, joint position, joint velocity, joint relative orientation, joint relative position), and the axis (x, y, z) along which the observation is made. This information is crucial for understanding the input data used by the model during the grasping tasks.

Full paper#