↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Federated learning (FL) systems are vulnerable to malicious clients compromising model accuracy and introducing bias. Analyzing client behavior is crucial but challenging due to the distributed nature of FL and the privacy constraints. Existing methods often focus on predictive performance alone, overlooking the decision-making processes of clients.

This paper introduces Federated Behavioural Planes (FBPs), a novel method that visualizes client behavior from two perspectives: predictive performance and decision-making processes. FBPs facilitate the identification of client clusters with similar behaviors, enabling a new robust aggregation technique called Federated Behavioural Shields (FBSs). Experiments show that FBSs enhance security and surpass existing state-of-the-art defense mechanisms.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in federated learning because it introduces Federated Behavioural Planes (FBPs), a novel method for analyzing client behavior, and Federated Behavioural Shields (FBSs), a robust aggregation technique that enhances security and surpasses existing state-of-the-art defense mechanisms. It offers valuable insights into client dynamics and enables the development of more secure and efficient FL systems.

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the Federated Behavioral Planes (FBPs) framework. It shows how FBPs visualize client behavior in federated learning (FL) using two planes: the Error Behavioral Plane (EBP) representing predictive performance and the Counterfactuals Behavioral Plane (CBP) representing decision-making processes. Client trajectories and clusters are shown, highlighting how FBPs can reveal insights into client interactions and inform a new robust aggregation method.

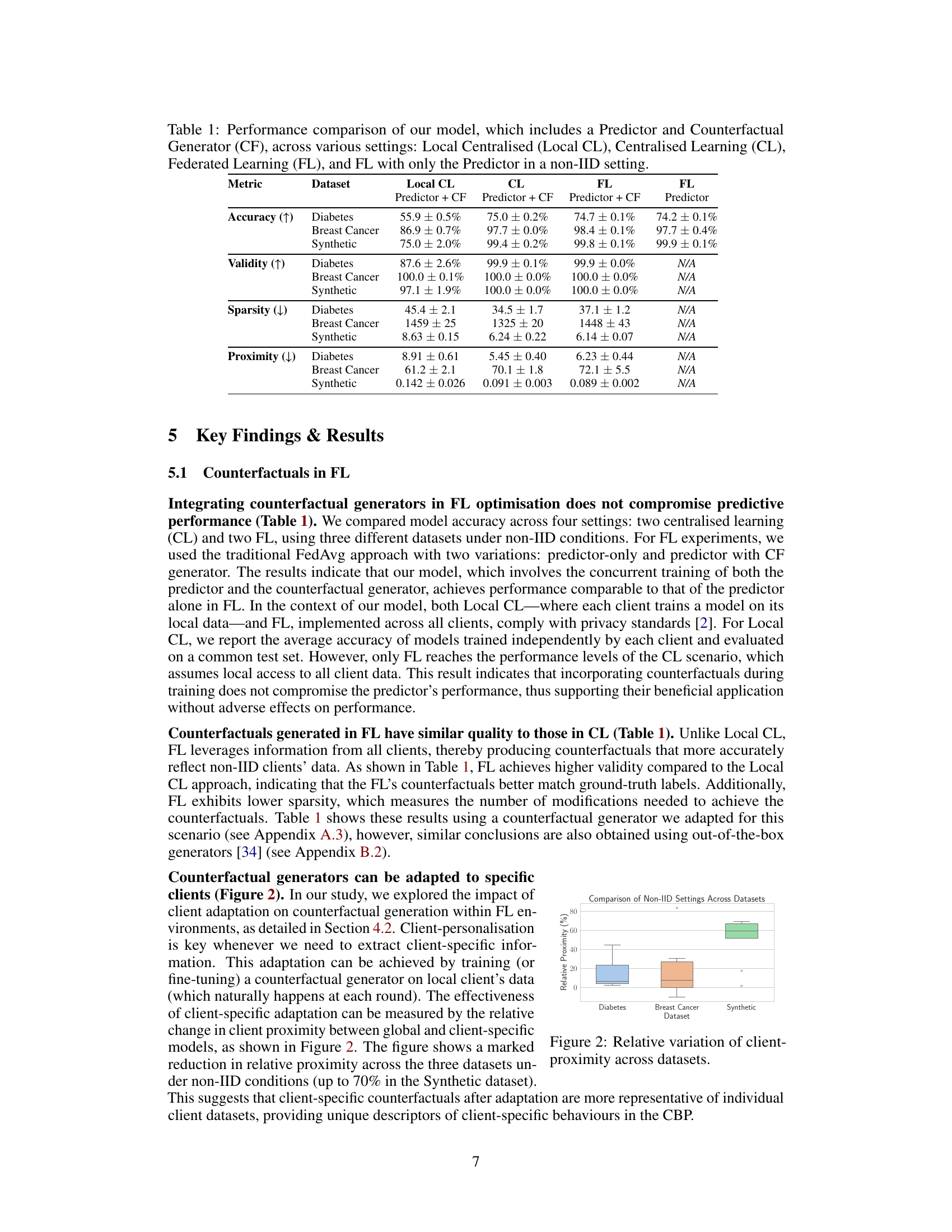

This table compares the performance of a model with and without a counterfactual generator in four different settings: local centralized learning (each client trains a model independently), centralized learning (all data is available to a single model), federated learning (clients collaboratively train a model without sharing their data), and federated learning with only the predictor (no counterfactual generator). The results show the accuracy, validity, sparsity, and proximity of the models in each setting across three datasets (Diabetes, Breast Cancer, Synthetic). It evaluates the impact of adding a counterfactual generator on the model’s performance in various settings.

In-depth insights#

Federated Learning#

Federated learning (FL) is a privacy-enhancing distributed machine learning approach. It allows multiple clients to collaboratively train a shared model without directly sharing their private data. This is a crucial advantage, addressing major privacy concerns inherent in traditional centralized machine learning. However, FL introduces unique challenges, such as data heterogeneity across clients, communication costs, and vulnerability to malicious clients that may inject faulty data or models to disrupt the training process. Understanding and mitigating these challenges is essential for the successful deployment of FL. Robust aggregation techniques and security mechanisms are vital to ensure the integrity and reliability of the collaboratively trained model. The potential of FL to enable powerful machine learning applications while preserving data privacy is immense, but significant research effort is still required to overcome these challenges and unlock its full potential. Future work may explore advanced techniques to enhance robustness, efficiency, and security.

Behavioral Planes#

The concept of “Behavioral Planes” in the context of Federated Learning (FL) offers a novel way to visualize and interpret client behavior during model training. Instead of relying solely on aggregate metrics, Behavioral Planes provide a multi-dimensional view, examining clients based on their predictive performance and decision-making processes. This dual-perspective approach allows researchers to identify patterns and anomalies. By analyzing clients’ trajectories and clustering similar behaviors, researchers can better understand the dynamics of FL systems and mitigate risks associated with malicious or noisy clients. The visualization of these planes, perhaps using dimensionality reduction techniques for clarity, would facilitate model debugging and trust. This approach is a significant step toward making FL more interpretable and robust.

Robust Aggregation#

Robust aggregation techniques in federated learning aim to mitigate the impact of malicious or faulty client updates on the global model’s accuracy. Byzantine-robust aggregation, a common approach, focuses on identifying and discarding outliers before aggregation. Methods like Krum, Trimmed Mean, and Median use statistical measures to achieve this. However, these methods often rely on assumptions about the distribution of client updates and may struggle in heterogeneous scenarios with non-IID (independent and identically distributed) data. Federated Averaging (FedAvg), although simple and widely used, is highly sensitive to such issues. Therefore, new methods are needed that are adaptive to diverse and potentially adversarial data distributions. Sophisticated approaches might incorporate advanced outlier detection mechanisms, data weighting strategies, or even secure multi-party computation protocols. Understanding the tradeoffs between robustness, communication overhead, and computational complexity is key to selecting the best method for a specific application.

Experimental Setup#

A robust experimental setup is crucial for validating the claims of any research paper. In this context, a well-designed experimental setup should meticulously detail the datasets used, specifying their characteristics (size, features, distribution) and addressing potential biases. Data preprocessing steps should be clearly explained, including how data was cleaned, handled, and prepared for model training. The choice of models, including the architecture, hyperparameters, and training procedures (e.g., optimization algorithms, batch size, learning rate), should be justified and documented in detail. Metrics used for evaluation should be clearly defined and their relevance to the research questions should be explained. The experimental design should include appropriate control groups or baselines, allowing for fair comparisons between different approaches. Reproducibility is paramount; therefore, detailed information should be provided to enable others to replicate the experiments. Finally, the computational resources used (hardware, software) should be specified, ensuring transparency and facilitating the assessment of the feasibility of the work.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Expanding the types of behavioural planes by incorporating additional descriptors of client behaviour (e.g., model complexity, training time) would enrich the analysis. Investigating different aggregation mechanisms beyond Federated Behavioural Shields, possibly using reinforcement learning or game-theoretic approaches, could further enhance robustness and security. Addressing the challenges posed by non-IID data and improving efficiency of counterfactual generation are crucial. Developing robust techniques for anomaly detection in diverse distributed systems remains a significant challenge. Finally, extending FBPs to other federated learning settings beyond deep learning (e.g., federated reinforcement learning, federated multi-task learning) and investigating the impact of privacy-enhancing technologies on their efficacy deserves further attention. These multifaceted directions offer significant potential to advance the understanding and application of federated learning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

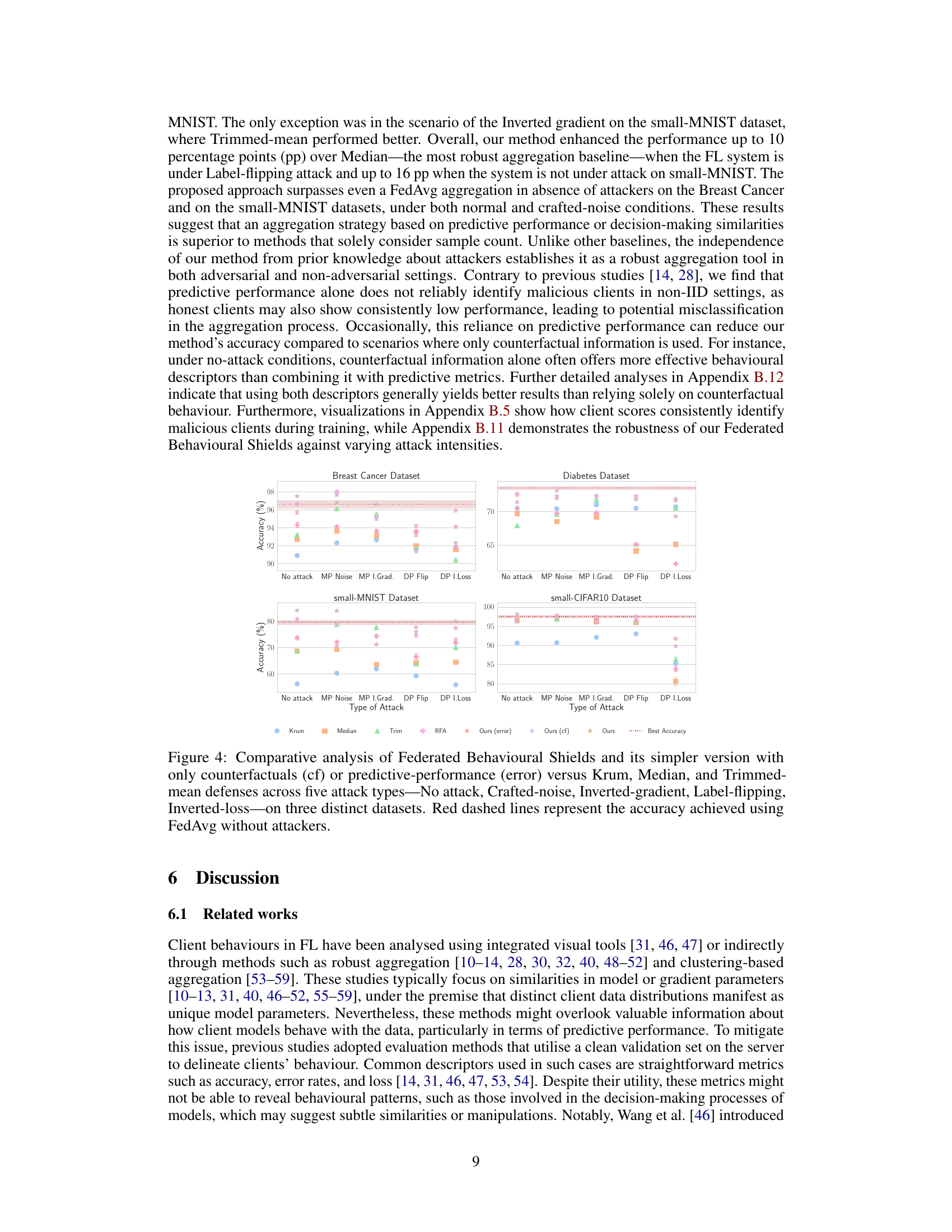

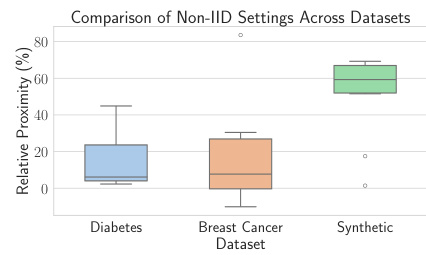

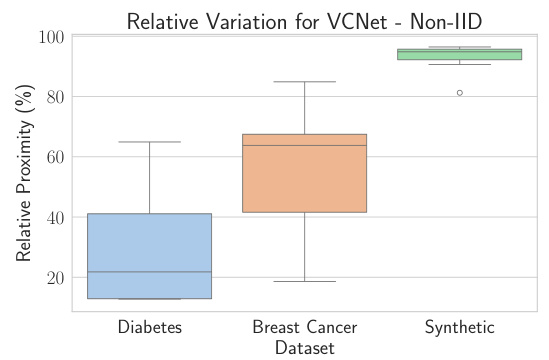

This box plot displays the relative proximity values for three different datasets (Diabetes, Breast Cancer, Synthetic) under non-IID settings. The relative proximity metric is calculated as (Pglobal - Plocal)/Pglobal, where Pglobal represents the proximity of the globally trained model and Plocal is the proximity of the client-specific model. The plot visually shows how much the client-specific models deviate from the global model, indicating the level of client-specific adaptation. The higher values of relative proximity indicate a higher level of client-specific adaptation.

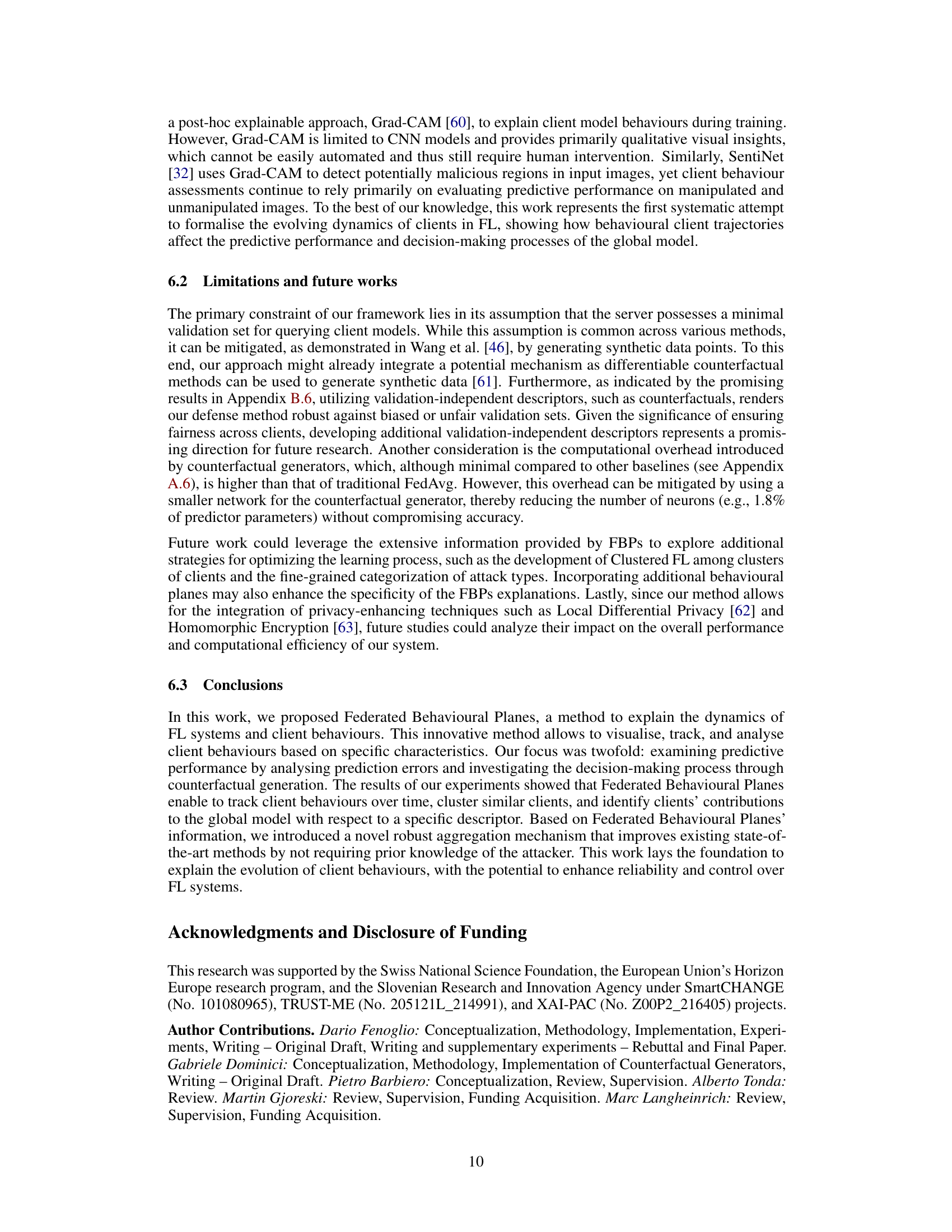

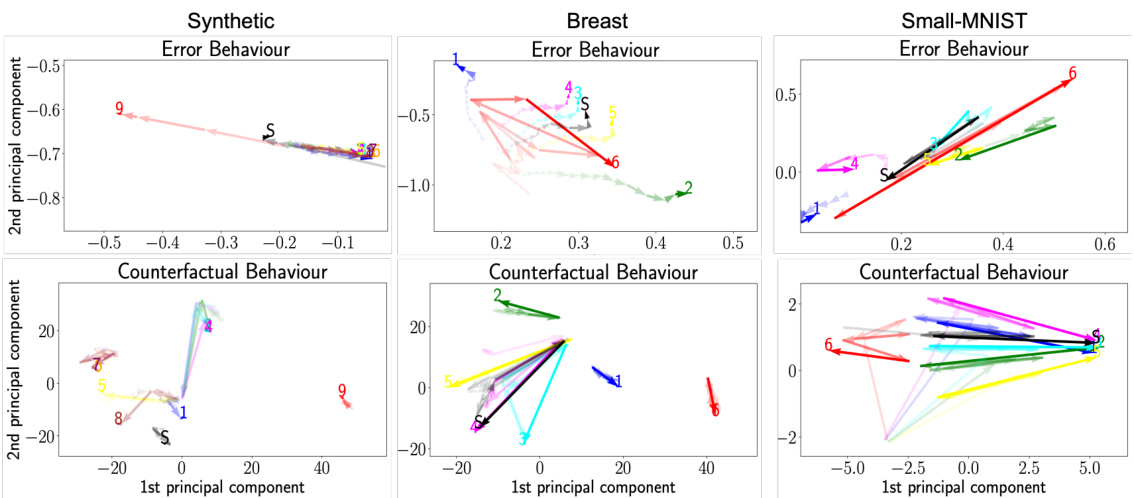

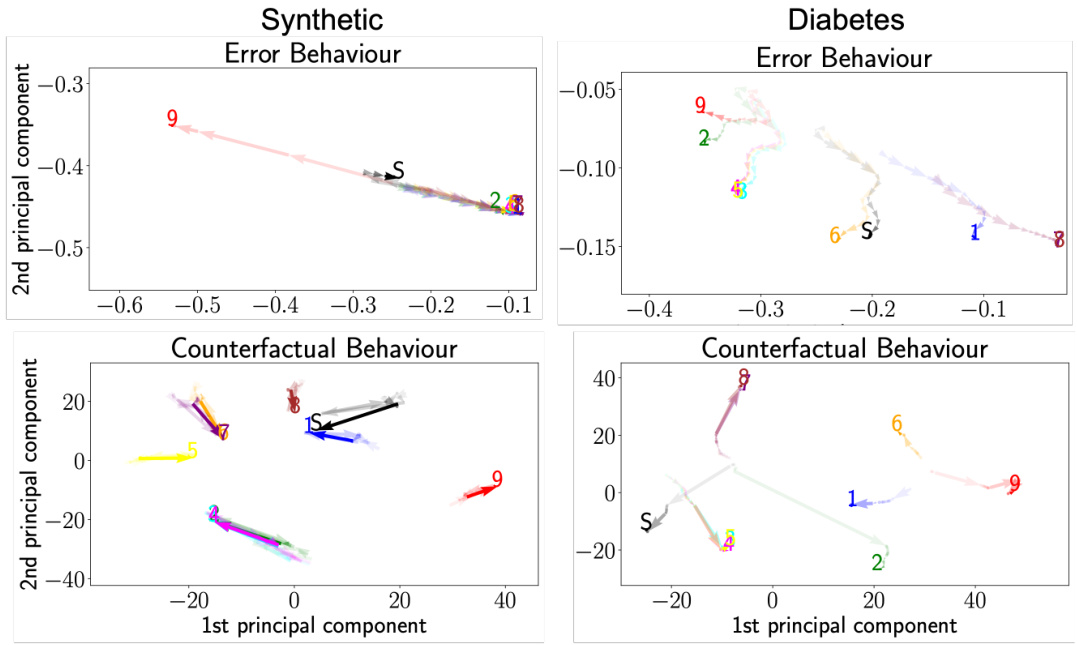

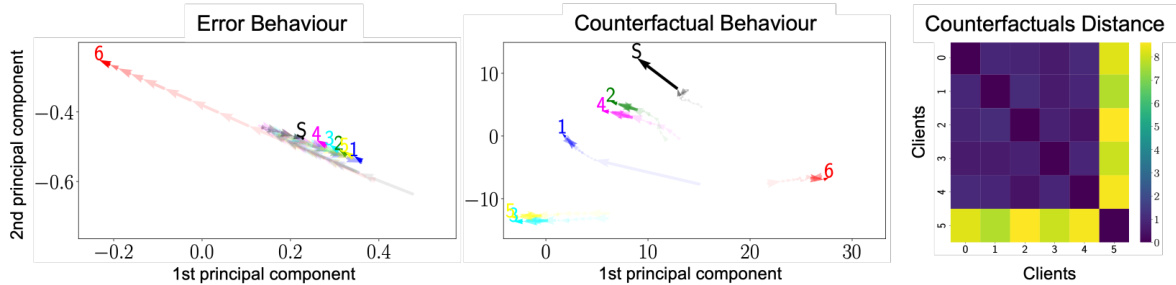

This figure visualizes client behavior in Federated Learning (FL) using Federated Behavioral Planes (FBPs). It shows trajectories of clients on two planes: the Error Behavioural Plane (EBP) representing predictive performance, and the Counterfactual Behavioural Plane (CBP) illustrating decision-making processes. Three datasets (Synthetic, Breast Cancer, small-MNIST) are shown, each with a different attack (Inverted-loss, Crafted-noise, Inverted-gradient). The plots reveal how malicious clients (red) deviate from the behavior of honest clients, which tend to cluster together, and how these behaviors impact the overall model (S).

This figure shows the trajectories of clients in Federated Behavioural Planes (FBPs) under different attack scenarios. It uses three datasets (Synthetic, Breast Cancer, small-MNIST) and three attack types (Inverted-loss, Crafted-noise, Inverted-gradient). Each point on the plot represents a client’s state at a given training round, and the trajectory shows how the client’s behavior changes over time. The plots reveal distinct patterns in clients’ predictive performance and decision-making processes under different attacks. Malicious clients (red) deviate from the clusters of honest clients, and FBPs enables the identification of these malicious clients.

This figure illustrates the Federated Behavioural Planes (FBPs) framework, which visualizes client behavior in Federated Learning (FL) using two planes: the Error Behavioural Plane (EBP) showing predictive performance and the Counterfactuals Behavioural Plane (CBP) showing decision-making processes. It demonstrates how FBPs track client trajectories, identify similarities in client behavior, and support the development of a novel robust aggregation mechanism, Federated Behavioural Shields.

This figure shows the trajectories of clients in the Federated Behavioural Planes (FBPs) framework for three different datasets under various attack scenarios. The trajectories visualize client behavior from two perspectives: predictive performance (Error Behavioural Plane) and decision-making processes (Counterfactual Behavioural Plane). The figure highlights how malicious clients (red) deviate from the behavior of honest clients, which tend to form clusters over time. The trajectories provide insights into the dynamics of federated learning systems.

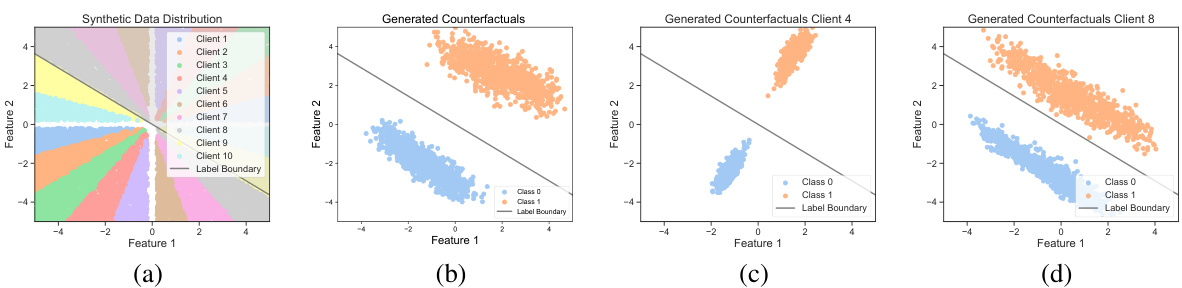

This figure visualizes the synthetic data distribution and generated counterfactuals for different clients. The synthetic dataset is designed with a linear decision boundary, allowing for a controlled study of data distribution impact on counterfactual generation. The figure shows that Client 4, whose data distribution is perpendicular to the decision boundary, achieves effective adaptation when the counterfactual generator is adapted to client-specific data; conversely, Client 8, whose data is close to the decision boundary, exhibits more challenges in the adaptation process. This highlights the influence of data distribution on the effectiveness of counterfactual adaptation in federated learning.

This figure compares the relative proximity (a measure of similarity) between global and client-specific models for three datasets (Diabetes, Breast Cancer, and Synthetic) under both IID (independently and identically distributed data) and non-IID (non-independently and identically distributed data) settings. The boxplots show that client-specific adaptation of the counterfactual generator reduces the proximity more in the non-IID setting, suggesting that personalization is more beneficial when data is not evenly distributed across clients.

This box plot displays the relative variation of client proximity across three datasets (Diabetes, Breast Cancer, and Synthetic) for VCNet. The relative proximity is calculated as (Pglobal - Plocal)/Pglobal, where Pglobal represents the proximity of the global counterfactual model and Plocal represents the proximity of the client-specific counterfactual model. The plot shows a significant reduction in relative proximity for all three datasets, indicating that client-specific adaptation significantly improves the personalization of counterfactuals. Non-IID settings are used.

This figure displays the Federated Behavioural Planes (FBPs) for three different datasets (Synthetic, Breast Cancer, and small-MNIST) under three different attacks (Inverted-loss, Crafted-noise, and Inverted-gradient). Each plane shows client trajectories over time. The trajectories of honest clients cluster together, while the trajectory of a malicious client (shown in red) deviates significantly from these clusters. The figure demonstrates how FBPs can visualize and explain the evolving behavior of clients in federated learning, highlighting the impact of malicious clients on the global model.

This figure visualizes client behavior in Federated Learning (FL) using Federated Behavioral Planes (FBPs). It shows trajectories of clients in two behavioral planes: the Error Behavioural Plane (EBP) representing predictive performance and the Counterfactual Behavioural Plane (CBP) illustrating decision-making processes. The figure demonstrates how clients behave under different attack types (Inverted-loss, Crafted-noise, and Inverted-gradient) on three different datasets (Synthetic, Breast Cancer, and small-MNIST). Honest clients tend to cluster together, while malicious clients deviate significantly from the cluster and the global model, allowing for easy identification.

This figure visualizes the effectiveness of Federated Behavioral Shields (FBSs) in identifying malicious clients across multiple attacks. The plot shows the mean and 95% confidence interval of client scores over 200 training rounds for honest clients, malicious clients, and a client with an unfair validation set (meaning its data distribution is not well-represented in the validation set used to compute the scores). The results demonstrate that FBSs effectively distinguish malicious clients from honest ones, even in the presence of clients with an unfair validation set, across different types of attacks.

This figure shows the trajectories of clients in Federated Behavioural Planes (FBPs) under different attack scenarios. The FBPs consist of two planes: Error Behavioural Plane (EBP) representing predictive performance, and Counterfactual Behavioural Plane (CBP) illustrating decision-making processes. The trajectories reveal how clients behave under three different attacks: Inverted-loss, Crafted-noise, and Inverted-gradient. Honest clients tend to cluster together while the malicious client (red) deviates significantly. The server’s global model (S) is also shown for comparison.

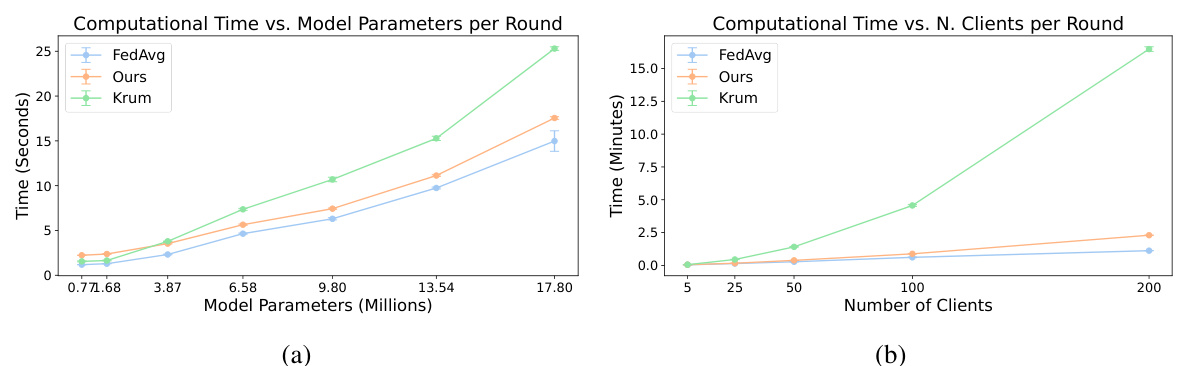

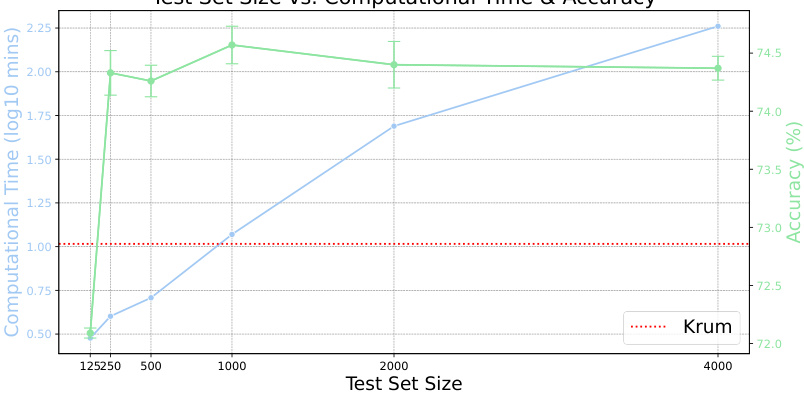

The figure shows the relationship between the size of the test set used for validation and both the computational time and accuracy achieved by the proposed method against an inverted gradient attack. As the size of the test set increases, the computational time increases exponentially. However, accuracy improvements are minimal after a certain point, indicating that increasing the test set size beyond a threshold does not provide significantly improved performance.

This figure visualizes the trajectories of clients in Federated Behavioural Planes (FBPs) under different attack scenarios. It shows how honest clients cluster together over time, while malicious clients deviate significantly from both the honest clients and the global model. The figure uses two planes to represent client behavior: one for predictive performance (Error Behavioural Plane) and one for decision-making processes (Counterfactual Behavioural Plane). The different attacks (Inverted-loss, Crafted-noise, and Inverted-gradient) are represented on different datasets.

This figure visualizes client behavior in Federated Learning (FL) using Federated Behavioral Planes (FBPs). It shows trajectories of clients across two planes: the Error Behavioural Plane (EBP) representing predictive performance and the Counterfactual Behavioural Plane (CBP) representing decision-making processes. The plots illustrate how clients behave under different attacks (Inverted-loss, Crafted-noise, and Inverted-gradient), highlighting how malicious clients (red) deviate from the behavior of honest clients, which tend to cluster together.

This figure visualizes client behavior in Federated Learning (FL) using Federated Behavioural Planes (FBPs). It shows trajectories of clients on two planes: Error Behavioural Plane (EBP) and Counterfactual Behavioural Plane (CBP). The EBP represents predictive performance, while the CBP represents decision-making processes. The trajectories illustrate how clients behave under different attacks (Inverted-loss, Crafted-noise, and Inverted-gradient). The figure highlights that honest clients tend to cluster together, while malicious clients deviate significantly. The global model’s trajectory is also shown for comparison.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of the counterfactual generator using different embedding sizes (128, 64, and 32). It shows the accuracy, validity, model parameters (Predictor+CF and CF alone), and GFLOPs (Predictor+CF and CF alone) for each embedding size. The ‘Increase’ column shows the percentage increase in model parameters and GFLOPs when using the counterfactual generator compared to using only the predictor.

This table presents a comparison of model performance metrics across four different settings: Local Centralised, Centralised Learning, Federated Learning with both predictor and counterfactual generator, and Federated Learning with only the predictor. The results show that including a counterfactual generator does not significantly impact the predictive performance of the model in federated learning scenarios. The table also shows that the performance of the model in Federated Learning settings is comparable to that of the Centralised Learning scenario, highlighting the effectiveness of federated learning in protecting privacy without sacrificing accuracy.

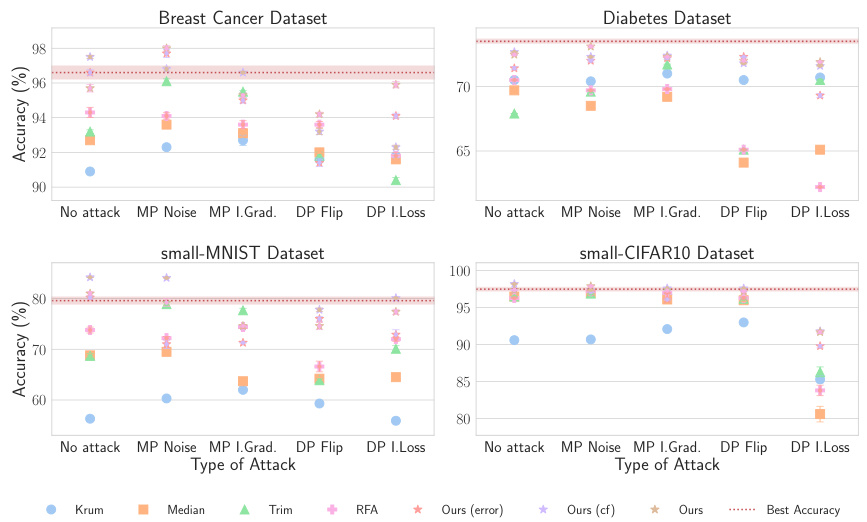

This table compares the performance of Federated Behavioral Shields (FBSs) under various attack scenarios (No attack, Crafted-noise, Inverted-gradient, Label-flipping, and Inverted-loss) for both IID and Non-IID data distributions on the Breast Cancer dataset. It allows for assessing the robustness of FBSs in different data settings and against different types of attacks.

This table presents a comparison of the accuracy achieved by different robust aggregation methods, including the proposed Federated Behavioural Shields (with and without moving average), against five different attack scenarios on two datasets (Breast Cancer and Diabetes). The results highlight the impact of using the moving average technique on improving the robustness of the proposed method against attacks.

This table compares the performance of a model with and without a counterfactual generator in four different settings: Local Centralised (each client trains a model on its local data), Centralised Learning (all data is centrally available), Federated Learning (clients collaboratively train a model without sharing their data), and Federated Learning with only the predictor. The results show the accuracy, validity, sparsity, and proximity of the counterfactuals generated across the settings and demonstrate that including the counterfactual generator does not significantly impact performance and could be beneficial in non-IID settings (Federated Learning).

This table presents a comparison of the model’s performance across four different settings: Local Centralised, Centralised Learning, Federated Learning, and Federated Learning with only the predictor. It shows the accuracy, validity, sparsity, and proximity metrics for each setting and two model variations (with and without the counterfactual generator), using three different datasets (Diabetes, Breast Cancer, and Synthetic) under Non-IID conditions. The results demonstrate the impact of incorporating counterfactual generators on the predictive performance of the models under various learning scenarios.

This table compares the performance of a model with and without a counterfactual generator in four different settings: Local Centralised, Centralised Learning, Federated Learning (with and without the generator). The results show the accuracy, validity, sparsity, and proximity of the counterfactuals generated in each setting. It aims to demonstrate that adding the counterfactual generator doesn’t harm predictive performance and produces counterfactuals of similar quality in federated learning as in centralized scenarios.

This table compares the performance of a model with and without a counterfactual generator across four different settings: local centralized learning, centralized learning, federated learning, and federated learning with only a predictor. The comparison is done using three different datasets in a non-IID setting, where data is not evenly distributed across clients. The metrics used for comparison are accuracy, validity, sparsity, and proximity, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance in different scenarios.

Full paper#