TL;DR#

Current generative models for discrete data often rely on simplifying assumptions about distribution structure or resort to variational bounds for likelihood estimation, limiting their ability to capture complex patterns. This paper addresses these limitations.

The paper introduces Statistical Flow Matching (SFM), a novel generative framework. SFM uses information geometry and the Fisher information metric to leverage the intrinsic geometry of the statistical manifold of categorical distributions. This approach allows for precise likelihood calculations and efficient training and sampling algorithms.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel framework for generative modeling on statistical manifolds, specifically addressing the limitations of existing methods for discrete data. It offers a mathematically rigorous approach that leverages information geometry, leading to improved sampling quality and likelihood estimation. This opens new avenues for research in various domains where generating discrete data is essential. The findings have a significant impact on various applications, such as computer vision, natural language processing, and bioinformatics.

Visual Insights#

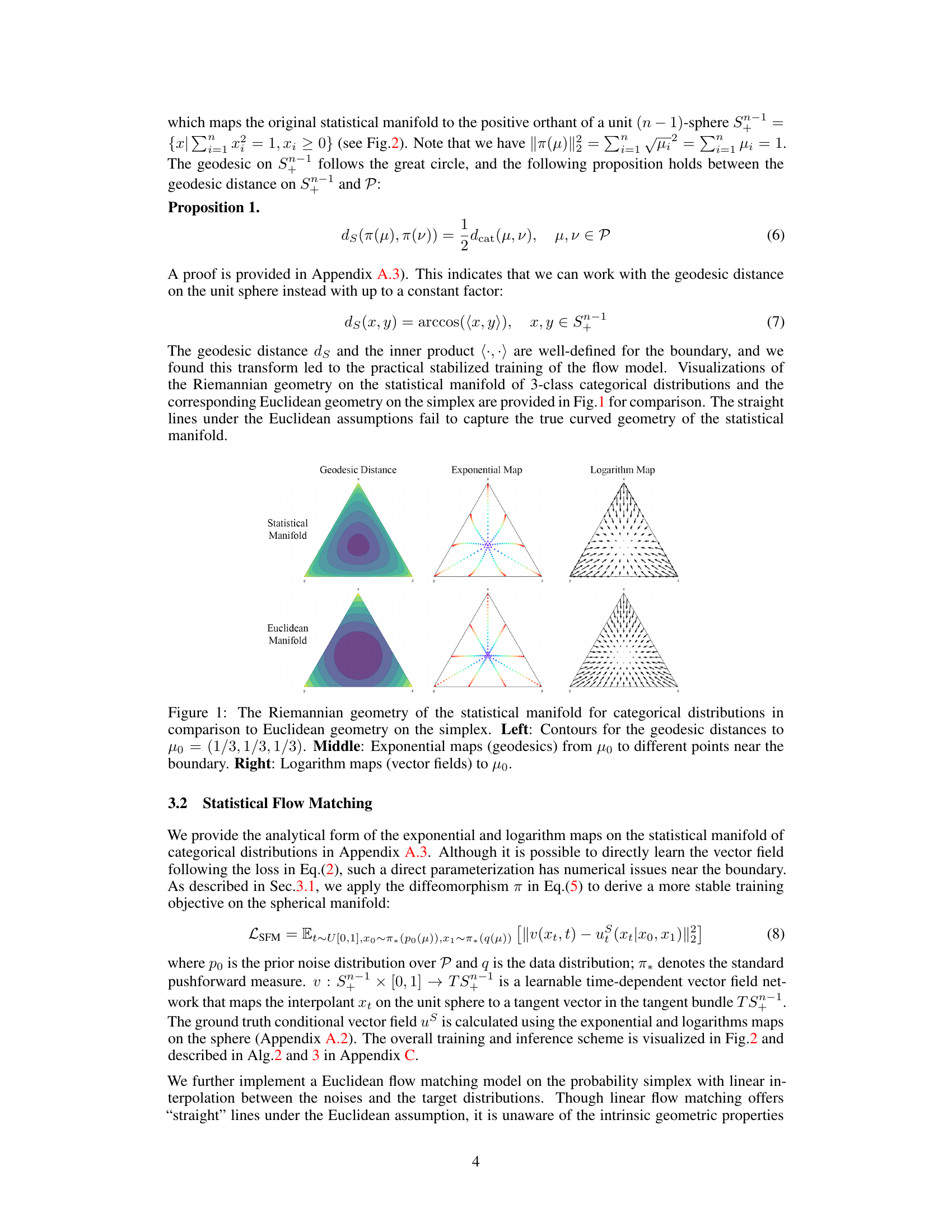

🔼 This figure compares the Riemannian geometry of the statistical manifold for categorical distributions with the Euclidean geometry on the simplex. The left panel shows contour plots of geodesic distances from a central point (1/3, 1/3, 1/3) on the simplex. The middle panel illustrates the exponential maps (geodesics) showing the shortest paths between the central point and other points on the simplex, highlighting the curved nature of the Riemannian geometry. The right panel displays the logarithm maps (vector fields) showing the directions of steepest descent from various points toward the central point, which again illustrates the effect of the Riemannian structure on the manifold.

read the caption

Figure 1: The Riemannian geometry of the statistical manifold for categorical distributions in comparison to Euclidean geometry on the simplex. Left: Contours for the geodesic distances to μ0 = (1/3, 1/3, 1/3). Middle: Exponential maps (geodesics) from μ0 to different points near the boundary. Right: Logarithm maps (vector fields) to μ0.

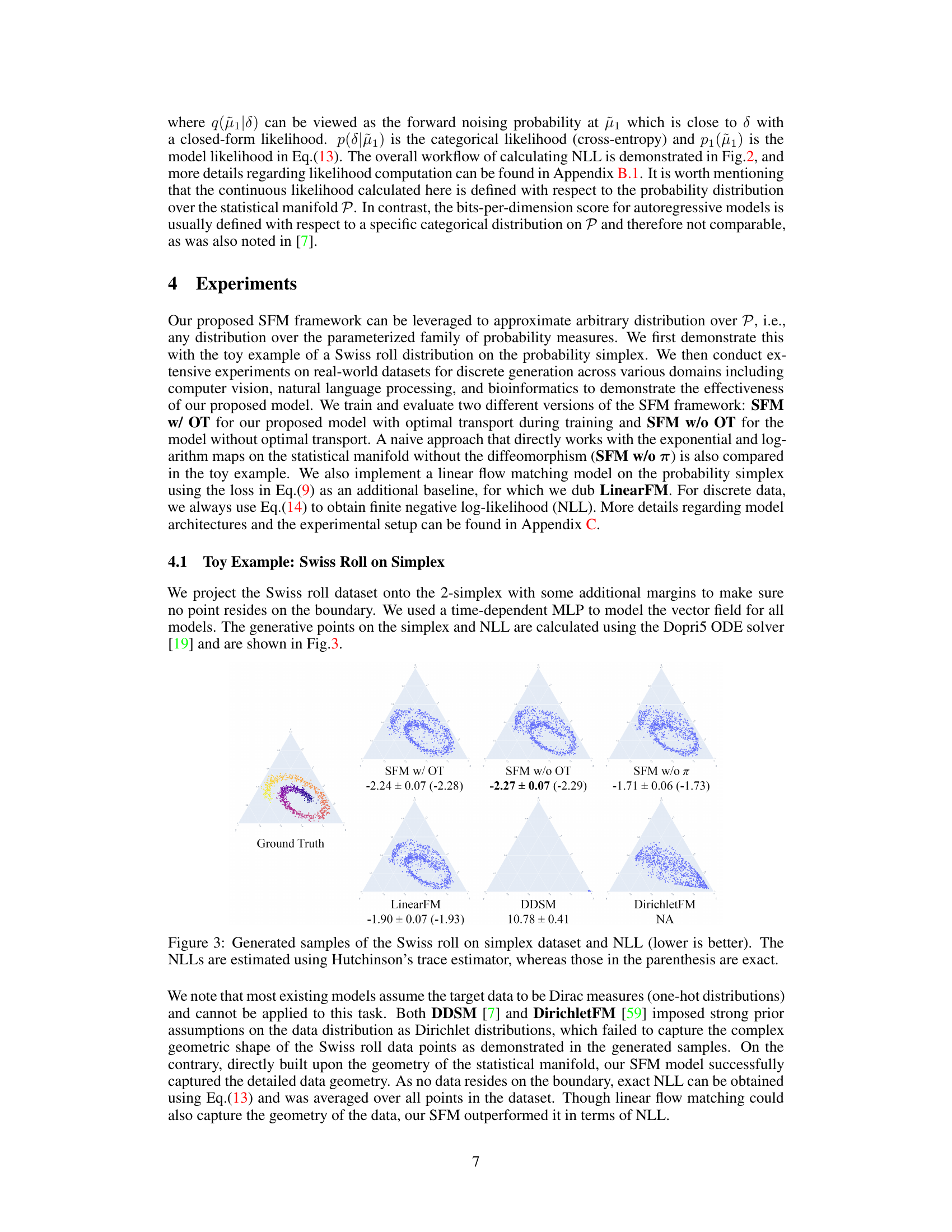

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different discrete models’ performance on the binarized MNIST dataset. The models are evaluated using two metrics: Negative Log-Likelihood (NLL) and Fréchet Inception Distance (FID). Lower values indicate better performance for both metrics. The table shows that the Statistical Flow Matching (SFM) models (with and without optimal transport) achieve the lowest NLL and FID values, suggesting superior performance compared to other models, including D3PM, DDSM and DirichletFM.

read the caption

Table 1: NLL and FID of different discrete models on binarized MNIST. * is from [7].

In-depth insights#

Manifold Geometry#

Manifold geometry offers a powerful framework for understanding and modeling complex data distributions. By viewing data points as residing on a curved surface (a manifold), rather than in a flat Euclidean space, we can capture the intrinsic geometric structure of the data. This approach is particularly beneficial when dealing with high-dimensional data or data exhibiting non-linear relationships, as it avoids the limitations of traditional linear methods. The choice of Riemannian metric on the manifold is crucial, influencing the notion of distance and the resulting geometric properties. The Fisher information metric, often used in information geometry, provides a natural and meaningful way to define distance between probability distributions. This metric leverages the inherent relationships in the data, leading to more accurate and insightful analyses. Geodesics, or shortest paths on the manifold, provide valuable insights into the underlying data structure. Algorithms that leverage these paths can provide more efficient and effective solutions compared to methods that are restricted to the linearity of Euclidean space. However, the choice of manifold, metric, and geodesic computation method presents its own challenges. For instance, calculating geodesics in high dimensions can be computationally expensive, requiring careful consideration of computational cost versus analytical advantages.

SFM Framework#

The Statistical Flow Matching (SFM) framework offers a novel approach to generative modeling by leveraging the intrinsic geometry of statistical manifolds. Unlike traditional methods that often rely on approximations or ad-hoc assumptions, SFM utilizes the Fisher information metric to equip the manifold with a Riemannian structure. This allows for the effective use of geodesics—the shortest paths between probability distributions—during both training and sampling. The framework’s strength lies in its ability to learn complex patterns by directly working with the underlying geometry, overcoming limitations of existing models that struggle with strong prior assumptions. The use of optimal transport enhances training efficiency, while the exact likelihood calculation avoids the approximations inherent in variational methods. SFM’s mathematical rigor and its ability to handle arbitrary probability measures make it a powerful tool for various generative tasks, particularly in the realm of discrete data generation, where it demonstrates superior performance compared to existing discrete diffusion or flow-based models.

Categorical SFM#

Categorical SFM, as presented in the research paper, proposes a novel approach to generative modeling on statistical manifolds. It addresses the challenge of discrete data generation by leveraging the intrinsic geometry of categorical distributions. Unlike previous methods which rely on variational bounds or ad hoc assumptions, the method directly learns the vector fields on the manifold, utilizing the Fisher information metric to define the Riemannian structure. This allows for exact likelihood calculation and interpretation of the learning process as following the steepest descent of the natural gradient. By mapping the categorical distribution space to a sphere via a diffeomorphism, the method overcomes numerical stability issues near the boundaries of the probability simplex. The resulting framework demonstrates promising results on various real-world tasks, surpassing existing discrete diffusion or flow-based models in terms of sampling quality and likelihood. A key advantage is its ability to learn more complex patterns on the statistical manifold, where existing methods often fail due to strong prior assumptions. The work highlights the significance of utilizing the intrinsic geometry of data for accurate and efficient generative modeling.

Exact Likelihood#

The heading ‘Exact Likelihood’ highlights a crucial advantage of the proposed Statistical Flow Matching (SFM) model. Unlike many existing discrete generative models that rely on variational bounds to approximate likelihood, SFM offers a method for precise likelihood calculation. This capability stems from SFM’s unique geometric perspective, leveraging the Riemannian structure of the statistical manifold and optimal transport. The exact likelihood calculation is not only theoretically significant but also practically advantageous, as it enables more reliable model evaluation and comparison. It eliminates the approximation errors inherent in variational methods, providing a more accurate measure of the model’s performance and potentially leading to better model training and sampling. The ability to compute exact likelihood is a notable contribution, setting SFM apart from existing approaches and highlighting its potential for superior performance in discrete generative tasks.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from this Statistical Flow Matching (SFM) work could explore extensions to non-discrete data, such as images or continuous signals. The current framework excels in discrete domains; adapting it to continuous spaces would significantly broaden its applicability. Investigating the impact of different Riemannian metrics beyond the Fisher information metric would further refine the model’s performance and theoretical understanding. The model’s current reliance on the independence assumption between classes could be relaxed by incorporating more sophisticated dependency structures to handle complex correlations within data. A thorough exploration of the computational efficiency of the algorithm at scale, including the feasibility of parallel processing and its performance with large datasets, is warranted. Finally, applying SFM to a wider range of real-world problems, potentially in areas like biological sequence design or drug discovery, would validate its practical utility and uncover potential limitations in diverse settings. Understanding the impact of various prior distributions and developing more effective methods for selecting priors would also strengthen the methodology.

More visual insights#

More on figures

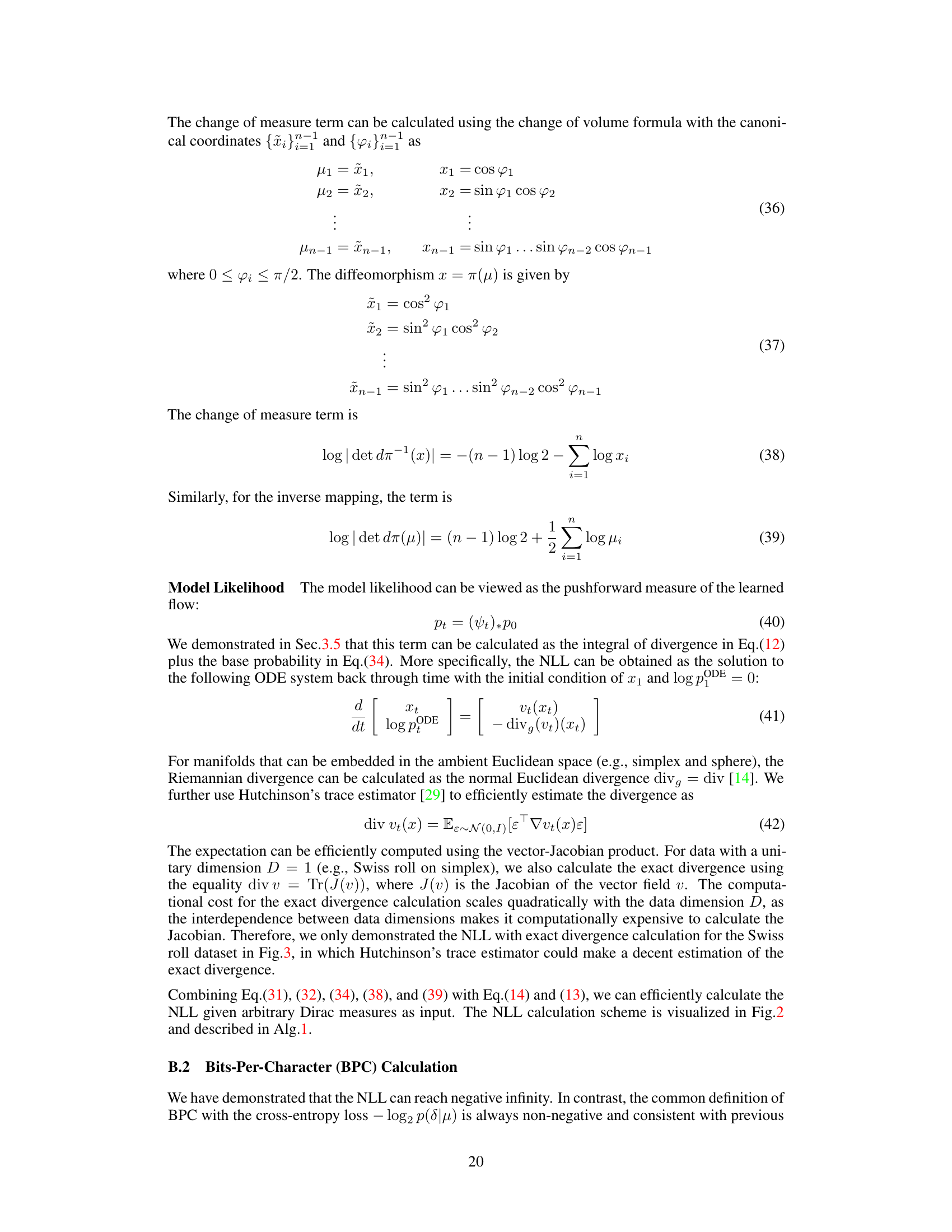

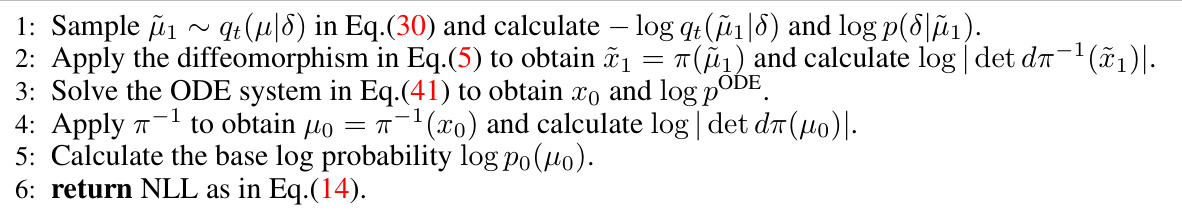

🔼 This figure illustrates the Statistical Flow Matching (SFM) framework. Panel (a) shows the training process, where probability measures are mapped from the statistical manifold P to the sphere Sn-1 using a diffeomorphism. A time-dependent vector field is learned on Sn-1, which is then used to generate a trajectory. This trajectory is mapped back to P to obtain the final probability measure. Panel (b) depicts the process of negative log-likelihood (NLL) calculation for one-hot examples. To avoid numerical instability issues at the boundary, the probability density is marginalized over a small neighborhood around a Dirac measure.

read the caption

Figure 2: Statistical flow matching (SFM) framework. (a) During training (Sec.3.2), probability measures on P are mapped to Sn-1 via diffeomorphism π to compute the time-dependent vector field (in red). During inference, the learned vector field generates the trajectory on Sn-1 and we map the outcome of ODE back to P (in blue). (b) In the NLL calculation for one-hot examples (Sec.3.5), the probability density is marginalized over a small neighborhood of some Dirac measure to avoid undefined behaviors at the boundary (in green).

🔼 This figure compares the Riemannian geometry of the statistical manifold for categorical distributions with the Euclidean geometry on the simplex. The left panel shows contours of geodesic distances from a central point (1/3, 1/3, 1/3). The middle panel illustrates exponential maps (geodesics) connecting this central point to various points, highlighting the curved nature of the Riemannian manifold. The right panel shows logarithm maps (vector fields) pointing towards the central point. The comparison reveals that Euclidean geometry fails to represent the true curved geometry of the statistical manifold.

read the caption

Figure 1: The Riemannian geometry of the statistical manifold for categorical distributions in comparison to Euclidean geometry on the simplex. Left: Contours for the geodesic distances to μ0 = (1/3, 1/3, 1/3). Middle: Exponential maps (geodesics) from μ0 to different points near the boundary. Right: Logarithm maps (vector fields) to μ0.

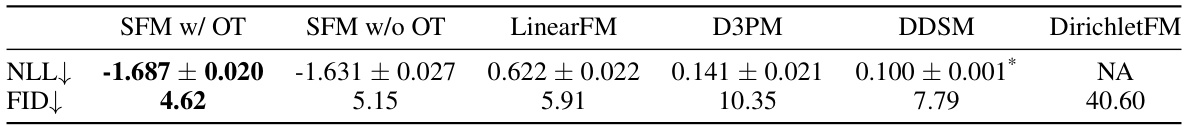

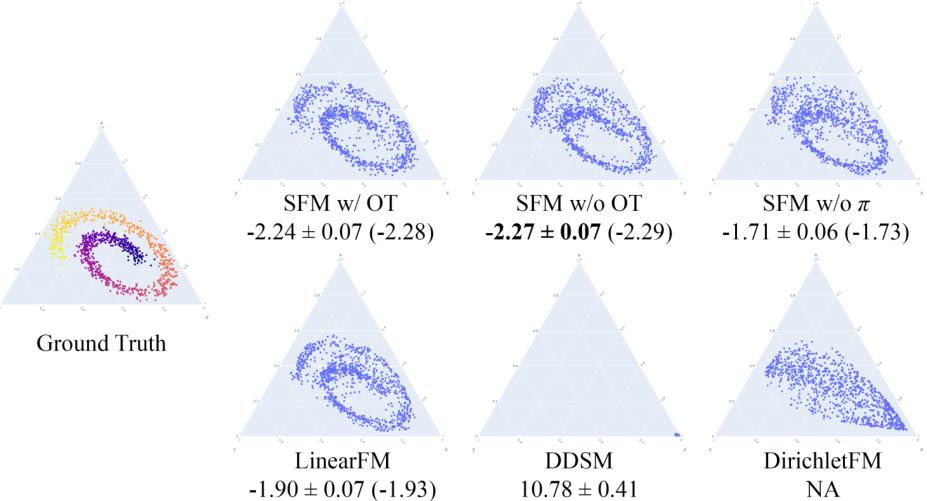

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between the GPT-J-6B NLL (negative log-likelihood) and sample entropy for various text generation models. Lower NLL and higher entropy generally indicate better model performance. The plot compares several models, including SFM (with and without optimal transport), MultiFlow (with different logit temperatures), D3PM, SEDD (with mask and uniform settings), and an autoregressive model. A random baseline is also included. The plot illustrates that SFM achieves a good balance between low NLL and high entropy, suggesting good model performance and sample diversity.

read the caption

Figure 4: GPT-J-6B NLL versus sample entropy. For MultiFlow, D3PM, and autoregressive, the curve represents different logit temperatures from 0.5 to 1. Baseline data are from [12].

🔼 This figure compares the Riemannian geometry of the statistical manifold for categorical distributions with the Euclidean geometry on the simplex. The left panel shows contour plots of geodesic distances to a central point (1/3, 1/3, 1/3). The middle panel visualizes geodesics (exponential maps) from this central point to various points near the boundary of the simplex, highlighting the curved nature of the Riemannian manifold. The right panel displays logarithm maps (vector fields) to the central point, illustrating how the vector field changes based on the manifold’s geometry.

read the caption

Figure 1: The Riemannian geometry of the statistical manifold for categorical distributions in comparison to Euclidean geometry on the simplex. Left: Contours for the geodesic distances to μ0 = (1/3, 1/3, 1/3). Middle: Exponential maps (geodesics) from μ0 to different points near the boundary. Right: Logarithm maps (vector fields) to μ0.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the bits-per-character (BPC) results on the Text8 dataset for different models. Lower BPC values indicate better performance. The results for SFM (with and without optimal transport), LinearFM, and several other baselines from previous work are shown, allowing for comparison of SFM’s performance against existing methods.

read the caption

Table 2: BPC on Text8. Results marked * are taken from the corresponding papers.

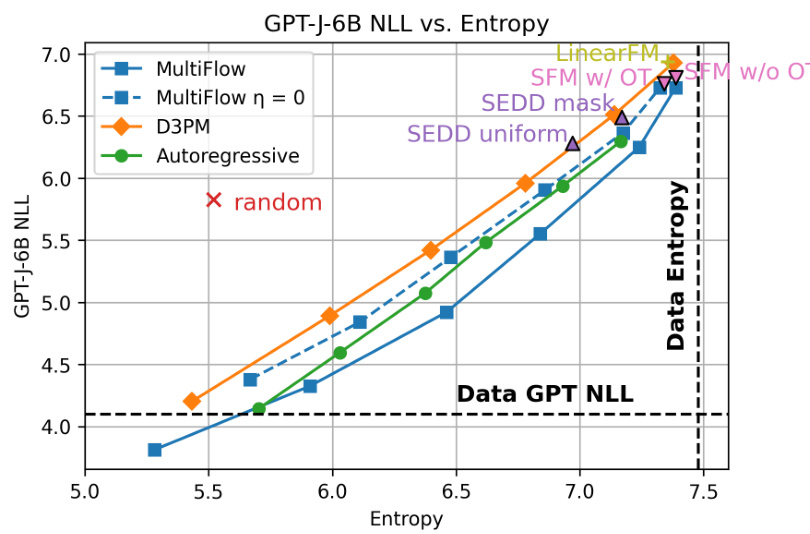

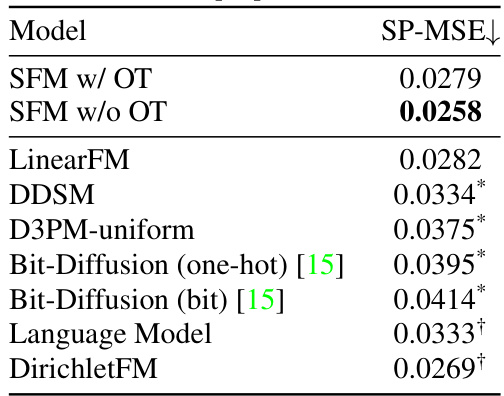

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating the quality of generated promoter DNA sequences using the Sei [13] model, which predicts promoter activity based on chromatin mark H3K4me3. The metric used is SP-MSE (mean squared error between predicted and actual promoter activity), lower values indicating better performance. The table compares the performance of several models, including the Statistical Flow Matching (SFM) model with and without optimal transport, highlighting the effectiveness of SFM in this complex bioinformatics generation task.

read the caption

Table 3: SP-MSE (as evaluated by Sei [13]) on the generated promoter DNA sequences. Results marked * are from [7] and results marked + are from [59].

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of various discrete generative models on the binarized MNIST dataset. The models are evaluated using two metrics: the negative log-likelihood (NLL), which measures how well the model assigns probabilities to the data, and the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), which assesses the quality and diversity of the generated samples. Lower NLL and FID scores indicate better performance. The table includes results for Statistical Flow Matching (SFM) with and without optimal transport, as well as other models from the literature (D3PM, LinearFM, DDSM, DirichletFM) for reference.

read the caption

Table 1: NLL and FID of different discrete models on binarized MNIST. * is from [7].

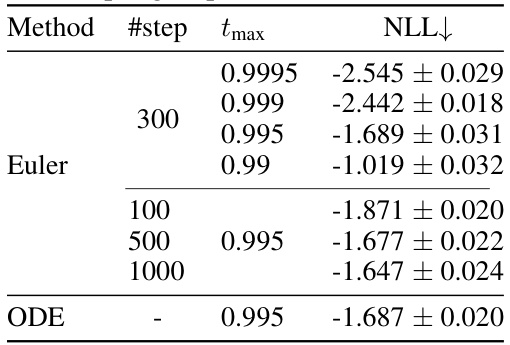

🔼 This table presents the negative log-likelihood (NLL) results obtained using different sampling methods (Euler and ODE), varying the number of steps in Euler method, and different values of the maximum timestep (tmax). It showcases the impact of these hyperparameters on the model’s performance, highlighting the trade-off between accuracy and computational cost.

read the caption

Table 4: NLL for different sampling methods, sampling steps, and tmax.

🔼 This table presents the results of negative log-likelihood (NLL) and Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores for different discrete generative models on the binarized MNIST dataset. Lower NLL and FID values indicate better model performance. The models compared include two versions of the proposed Statistical Flow Matching (SFM) method (with and without optimal transport), Linear Flow Matching (LinearFM), and previously published D3PM and DDSM models for reference. The asterisk (*) indicates that the DDSM results are from a different source.

read the caption

Table 1: NLL and FID of different discrete models on binarized MNIST. * is from [7].

Full paper#